| Issue |

A&A

Volume 535, November 2011

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | L7 | |

| Number of page(s) | 5 | |

| Section | Letters | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201117081 | |

| Published online | 21 November 2011 | |

Letter to the Editor

WASP-43b: the closest-orbiting hot Jupiter

1

Astrophysics Group, Keele University, Staffordshire, ST5 5BG, UK

e-mail: ch@astro.keele.ac.uk

2

SUPA, School of Physics and Astronomy, University of St. Andrews, North Haugh, Fife, KY16 9SS, UK

3 Institut d’Astrophysique et de Géophysique, Université de Liège, Allée du 6 Août, 17, Bât. B5C, Liège 1, Belgium

4

Observatoire astronomique de l’Université de Genève, 51 Ch. des Maillettes, 1290 Sauverny, Switzerland

5

Astrophysics Research Centre, School of Mathematics & Physics, Queen’s University, University Road, Belfast, BT7 1NN, UK

6

Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Leicester, Leicester, LE1 7RH, UK

Received: 14 April 2011

Accepted: 1 November 2011

We report the discovery of WASP-43b, a hot Jupiter transiting a K7V star every 0.81 d. At 0.6-M⊙ the host star has the lowest mass of any star currently known to host a hot Jupiter. It also shows a 15.6-d rotation period. The planet has a mass of 1.8 MJup, a radius of 0.9 RJup, and with a semi-major axis of only 0.014 AU has the smallest orbital distance of any known hot Jupiter. The discovery of such a planet around a K7V star shows that planets with apparently short remaining lifetimes owing to tidal decay of the orbit are also found around stars with deep convection zones.

Key words: stars: individual: WASP-43 / planetary systems

© ESO, 2011

1. Introduction

As planet discoveries increase we begin to see patterns in their distribution, and to find the rarer systems that mark the edges of the envelope. The ground-based transit searches such as WASP (Pollacco et al. 2006) and HAT (Bakos et al. 2002) are particularly suitable for finding the systems that delineate the cut-off of hot Jupiters as orbital radius decreases. This distribution is expected to tell us about several processes, including disk migration and possible “stopping mechanisms” (e.g. Matsumura et al. 2007), third-body processes, such as scattering and the Kozai mechanism, that can move planets onto eccentric orbits that then circularize at short periods (e.g. Guillochon et al. 2011), and the effect of tidal interactions with the host star (e.g. Matsumura et al. 2010).

The WASP-South camera array has been monitoring stars of magnitude 9–13 since 2006, and, in conjunction with radial-velocities from the Euler/CORALIE spectrograph, is now responsible for the majority of transiting hot Jupiters currently known in the Southern hemisphere (see Hellier et al. 2011). Here we report the discovery of WASP-43b, a hot Jupiter orbiting a late-type star with a very small semi-major axis.

|

Fig. 1 (Top) The WASP-South lightcurve folded on the 0.81-d transit period. (Second panel) The binned WASP data with (offset) the TRAPPIST (I+z) and Euler (Gunn r) transit lightcurves, with the fitted MCMC model. (Third) The CORALIE radial velocities with the fitted model. (Lowest) The bisector spans; the absence of any correlation with radial velocity is a check against transit mimics. |

CORALIE radial velocities of WASP-43.

System parameters for WASP-43.

|

Fig. 2 A periodogram of the 2009 WASP-South photometry, showing a 15.6-d modulation. The horizontal lines show the 0.01 and 0.001 false-alarm probability levels. |

2. Observations

The WASP project uses 8-camera arrays that cover 450 square degrees of sky with a typical cadence of 8 min. The WASP surveys are described in Pollacco et al. (2006) while a discussion of our planet-hunting methods can be found in Collier-Cameron et al. (2007) and Pollacco et al. (2007).

WASP-43 is a V = 12.4, K7V star in the constellation Sextans. It was flagged as a planet candidate based on WASP-South data obtained during 2009 January–May, and has been further observed by both WASP-South and SuperWASP-North over 2010 January–May, leading to a total of 13 768 data points. A putative 0.81-d transit period led to radial-velocity followup with the CORALIE spectrograph on the Euler 1.2-m telescope at La Silla. Fourteen radial-velocity measurements over 2010 January–July (Table 1) showed that the transiting body is a 1.8-MJup planet. We also checked the bisectors (e.g. Queloz et al. 2001) to guard against transit mimics (Fig. 1). On 2010 December 07 we obtained a transit lightcurve with the TRAPPIST 0.6-m telescope (Gillon et al. 2011) in a passband of I+z, while on 2010 December 29 we obtained a further transit lightcurve with EulerCAM in a Gunn r passband.

3. The star WASP-43

The 15 CORALIE spectra of WASP-43 were co-added to produce a spectrum with a typical S/N of 70:1, which we analysed using the methods described in Gillon et al. (2009). We used the Hα line to determine the effective temperature (Teff), and the Na i D and Mg i b lines as diagnostics of the surface gravity (log g∗). The parameters obtained are listed in Table 2. The elemental abundances were determined from equivalent-width measurements of several clean and unblended lines. A value for microturbulence (ξt) was determined from Fe i lines using the criteria of a null-dependence of line abundances with equivalent width (see Magain 1984). The quoted error estimates include that given by the uncertainties in Teff, log g∗ and ξt, as well as the scatter due to measurement and atomic data uncertainties.

The temperature and log g∗ values, and also the BVRIJHK magnitudes collected by SIMBAD, are consistent with a K7 main-sequence star. To check the above Teff estimate we have also used published broad-band photometry to estimate the total observed bolometric flux. The Infrared Flux Method (Blackwell & Shallis 1977) was then used with 2MASS magnitudes to give Teff − IRFM = 4430 ± 120 K, consistent with the estimate from the Hα line.

The star might have slightly above-Solar metal abundances (Table 2). There is no detection of lithium in the spectra, with an equivalent-width upper limit of 18 mÅ, corresponding to an abundance upper limit of log A(Li) < 0.2 ± 0.3. For mid-K stars lithium is expected to be depleted in only a few 100s Myr. The presence of strong Ca H+K emission indicates that WASP-43 is an active star.

The projected stellar rotation velocity (v sinI) was determined by fitting the profiles of several unblended Fe i lines. Macroturbulence was assumed to be zero, since for mid-K stars it is expected to be lower than that of thermal broadening (Gray 2008). An instrumental FWHM of 0.11 ± 0.01 Å was estimated from the telluric lines around 6300 Å. The best-fitting value of v sinI was 4.0 ± 0.4 km s-1. For a K7V star, V = 12.4 would indicate a distance of ~ 80 pc. The proper motion of 0.06′′ yr-1 (Zacharias et al. 2010) then indicates a transverse velocity of 23 km s-1, which is typical of a local thin-disk star.

3.1. Rotational modulation

We searched the WASP photometry of WASP-43 for rotational modulations by using a sine-wave fitting algorithm as described by Maxted et al. (2011). We estimated the significance of periodicities by subtracting the fitted transit lightcurve and then repeatedly and randomly permuting the nights of observation.

The 2009 WASP-South data show a modulation at a period of 15.6 ± 0.4 d with a significance of >99.9% (Fig. 2), plus its first harmonic at 7.8 d. The amplitude is 0.006 ± 0.001 mag. The 2010 data (not shown) show the same modulation less clearly, but still with a significance of >99%. Most likely 15.6 d is the rotational period of WASP-43. If Prot were instead at the 7.8-d period then the dominant power would be at twice Prot, which is unfeasible for any spot pattern.

Formally we cannot exclude the possibility that the 15.6-d modulation is the beat period between the 1-d sampling and the true period, which would then be either 0.94 or 1.07 d, but such fast rotation would be expected to result in Hα in emission, whereas the CORALIE spectra show it to be in absorption, and, further, this rotation period would be incompatible with the measured v sinI of 4.0 ± 0.4 km s-1 unless the star were nearly pole-on.

Taking the rotation period as 15.6 d, and with the radius from Table 2, gives an equatorial velocity of v = 2.0 ± 0.1 km s-1. This is significantly lower than the measured v sinI, which suggests that there is additional broadening in the lines. For example the two are reconciled by increasing macroturbulence to 3 km s-1. The 15.6-d rotation rate implies a gyrochronological age of  Myr, using the Barnes (2007) relation. However, this would assume that the star has not been spun up by tidal interactions with the planet; an alternative possibility is that the star could be significantly older, but has been spun up by tidal interactions that will eventually destroy the planet (see, e.g., Brown et al. 2011).

Myr, using the Barnes (2007) relation. However, this would assume that the star has not been spun up by tidal interactions with the planet; an alternative possibility is that the star could be significantly older, but has been spun up by tidal interactions that will eventually destroy the planet (see, e.g., Brown et al. 2011).

4. System parameters

The CORALIE radial-velocity measurements were combined with the WASP, Euler and TRAPPIST photometry in a simultaneous Markov-chain Monte-Carlo (MCMC) analysis to find the parameters of the WASP-43 system (Table 2). For details of our methods see Collier Cameron et al. (2007). For limb darkening we used the 4-parameter non-linear law of Claret (2000) with parameters at the values noted in Table 2.

The data are compatible with zero eccentricity (with a 3σ limit of 0.04) and thus a circular orbit was imposed on the solution in Table 2. The fitted parameters were thus Tc, P, ΔF, T14, b, K1, where Tc is the epoch of mid-transit, P is the orbital period, ΔF is the fractional flux-deficit that would be observed during transit in the absence of limb-darkening, T14 is the total transit duration (from first to fourth contact), b is the impact parameter of the planet’s path across the stellar disc, and K1 is the stellar reflex velocity semi-amplitude.

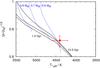

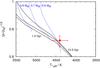

Pursuing a method used in past WASP papers, we use the Teff from the spectroscopy and the stellar density from fitting the transit plus a metallicity of Z = 0.017 to fit to the evolutionary tracks from Girardi et al. (2000) in order to obtain stellar radius and mass (as illustrated in Fig. 3). We should caution, however, that stellar mass–radius calibrations are not well constrained in this mass range, showing differences up to 0.1 M⊙ (e.g. Southworth 2009). To illustrate this we have also used an independent analysis following the methods in Southworth (2011), which produces a mass higher by 0.1 M⊙, or about 2σ (both solutions are quoted in Table 2). The first solution produces a stellar mass and radius in line with those of some calibration stars, whereas the second produces a mass and radius in line with those of Kepler-16 A, which is well determined by dynamics (see Fig. 3 of Winn et al. 2011b). This topic should be revisited when better data are available for WASP-43, particularly for Teff and metallicity.

|

Fig. 3 Evolutionary tracks on a modified H–R diagram ( |

|

Fig. 4 Mass versus semi-major axis for confirmed planets, where both are known, as compiled by Schneider et al. (2011). Some planets are labelled with abbreviated names. |

5. Discussion

WASP-43b has an exceptionally short orbital period of 0.81 d, second only to that of WASP-19b (0.79 d, Hebb et al. 2010) among confirmed planets. The host star, at K7V, has the lowest mass of any star orbited by a hot Jupiter1, and this results in the planet having the smallest semi-major axis of any hot Jupiter. Among all known planets only the super-Earths GJ 1214b (Charbonneau et al. 2009) and 55 Cnc e (Winn et al. 2011a) have values as small (see Fig. 4).

Hot Jupiters with such short periods are much rarer than those in an apparent “pile up” near 3−4 d. For example in Hellier et al. (2011) we estimated that they were two orders of magnitude less common, and found only because ground-based transit surveys such as WASP are most sensitive to the shortest-period planets. For comparison the Kepler list of 1235 planet candidates from 156,000 stars shows no systems with parameters similar to those of WASP-43b and WASP-19b (Borucki et al. 2011; Howard et al. 2011).

Ford & Rasio (2006) noted that the decline in the population of hot Jupiters at short orbital periods occurs near 2 Roche radii (2 aR), which is the radius at which planets scattered into eccentric orbits from much further out would tend to circularize. The idea that many of the hot Jupiters in the 3–4-d pileup have undergone scattering or Kozai migration (e.g. Fabrycky & Tremaine 2007; Nagasawa et al. 2008) is supported by the finding that many have orbits which are misalinged with the stellar spin axes (e.g. Triaud et al. 2010; Winn et al. 2010), which cannot be explained by simple disk migration.

WASP-43b is currently at 2.1 aR (using the definition of Ford & Rasio 2006), and thus fits the scenario of circularization near this radius after third-body interactions (e.g. Matsumura et al. 2010; Guillochon et al. 2011; Naoz et al. 2011). Thus, relative to aR, WASP-43b is not unusually close, and the small semi-major axis results from the unusually low mass of the host star. The rarity of objects like WASP-43b then indicates that hot Jupiters are rare around low-mass stars, or that their small orbital separations mean that their lifetimes owing to tidal decay are short.

Tidal theory tells us that planets as close as WASP-43b will be spiralling inwards on a timescale set largely by the efficiency of tidal dissipation within the star (e.g. Rasio et al. 1996; Matsumura et al. 2010). The stellar dissipation is denoted by the quality factor,  . Thus the tidal inspiral time for WASP-43b from its current location (e.g. Eq. (5) of Levrard et al. 2009) is 8 Myr for

. Thus the tidal inspiral time for WASP-43b from its current location (e.g. Eq. (5) of Levrard et al. 2009) is 8 Myr for  = 106, 80 Myr for

= 106, 80 Myr for  = 107, and 800 Myr for

= 107, and 800 Myr for  = 108. A value of

= 108. A value of  = 106 has often been applied to planets (e.g. Levrard et al. 2009) based on calibrations from binary stars. However, such a value would give implausibly low lifetimes for planets such as WASP-19b (Hebb et al. 2010), WASP-18b (Hellier et al. 2009), and now WASP-43b.

= 106 has often been applied to planets (e.g. Levrard et al. 2009) based on calibrations from binary stars. However, such a value would give implausibly low lifetimes for planets such as WASP-19b (Hebb et al. 2010), WASP-18b (Hellier et al. 2009), and now WASP-43b.

Further, theorists have argued (e.g. Barker & Ogilvie 2009; Penev & Sasselov 2011) that values of  from binary stars are inappropriate, since stellar-mass companions spin up the stars to near the tidal forcing frequency, whereas planetary-mass companions do not. The dissipation of tidal waves is strongly affected by resonance between the tidal forcing and internal stellar waves (e.g. Sasselov 2003; Ogilvie & Lin 2007; Barker & Ogilvie 2009; Penev & Sasselov 2011), and so values of

from binary stars are inappropriate, since stellar-mass companions spin up the stars to near the tidal forcing frequency, whereas planetary-mass companions do not. The dissipation of tidal waves is strongly affected by resonance between the tidal forcing and internal stellar waves (e.g. Sasselov 2003; Ogilvie & Lin 2007; Barker & Ogilvie 2009; Penev & Sasselov 2011), and so values of  of 108–109 might be more appropriate in the case of planets. Values of

of 108–109 might be more appropriate in the case of planets. Values of  > 5 × 107 would result in WASP-43b having a lifetime comparable to or greater than the current gyrochronological age of its star.

> 5 × 107 would result in WASP-43b having a lifetime comparable to or greater than the current gyrochronological age of its star.

The main novelty contributed by WASP-43b is that, at K7, the host star is of much later spectral type than the other stars hosting planets with apparently short tidal lifetimes. For example WASP-18, which has the strongest tidal interaction of any planet–star system, is an F6 star, while WASP-19, WASP-12 and OGLE-TR-56 are G stars. The tidal dissipation will depend on the depth of the convection layer and its interface with a radiative zone, and thus values for  would be expected to depend on spectral type (e.g. Barker & Ogilvie 2009). With a later spectral type, and having a known rotation period, WASP-43 will be an important test case for theoretical

would be expected to depend on spectral type (e.g. Barker & Ogilvie 2009). With a later spectral type, and having a known rotation period, WASP-43 will be an important test case for theoretical  values.

values.

Acknowledgments

WASP-South is hosted by the South African Astronomical Observatory while SuperWASP-North is hosted by the Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias, and we are grateful for their ongoing support and assistance. Funding for WASP comes from consortium universities and from the UK’s Science and Technology Facilities Council. TRAPPIST is funded by the Belgian Fund for Scientific Research (Fond National de la Recherche Scientifique, FNRS) under the grant FRFC 2.5.594.09.F, with the participation of the Swiss National Science Fundation (SNF). M. Gillon and E. Jehin are FNRS Research Associates.

References

- Bakos, G. À., Làzàr, J., Papp, I., Sàri, P., & Green, E. M. 2002, PASP, 114, 974 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, S. A. 2007, ApJ, 669, 1167 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Barker, A. J., & Ogilvie, G. I. 2009, MNRAS, 395, 2268 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell, D. E., & Shallis, M. J. 1977, MNRAS, 180, 177 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Borucki, W. J., Koch, D. G., Basri, G., et al. 2011, ApJ, 736, 19 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, D. J. A., Collier Cameron, A., Hall, C., Hebb, L., & Smalley, B. 2011, MNRAS, 415, 605 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Charbonneau, D., Berta, Z. K., Irwin, J., et al. 2009, Nature, 462, 891 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claret, A. 2000, A&A, 363, 1081 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Collier Cameron, A., Bouchy, F., Hébrard, G., et al. 2007a, MNRAS, 375, 951 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Collier Cameron, A., Wilson, D. M., West, R. G., et al. 2007b, MNRAS, 380, 1230 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Fabrycky, D., & Tremaine, S. 2007, ApJ, 669, 1298 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ford, E. B., & Rasio, F. A. 2006, ApJ, 638, L45 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Gillon, M., Smalley, B., Hebb, L., et al. 2009, A&A, 496, 259 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Gillon, M., Jehin, E., Magain, P., et al. 2011, in Detection and dynamics of transiting exoplanets, ed. F. Bouchy, R. Díaz, & C. Moutou, EPJ Web Conf., 11, 01004 [Google Scholar]

- Girardi, L., Bressan, A., Bertelli, G., & Chiosi, C. 2000, A&AS, 141, 371 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Gray, D. F. 2008, The observation and analysis of stellar photospheres, 3rd edition (CUP), 507 [Google Scholar]

- Guillochon, J., Ramirez-Ruiz, E., & Lin, D. N. C. 2011, ApJ, 732, 74 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hebb, L., Collier-Cameron, A., Triaud, A. H. M. J., et al. 2010, ApJ, 708, 224 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hellier, C., Anderson, D. R., Collier Cameron, A., et al. 2009, Nature, 460, 1098 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hellier, C., Anderson, D. R., Collier Cameron, A., et al. 2011a, in Detection and dynamics of transiting exoplanets, ed. F. Bouchy, R. Díaz, & C. Moutou, EPJ Web Conf., 11, 01004 [Google Scholar]

- Hellier, C., Anderson, D. R., Collier-Cameron, A., et al. 2011b, ApJ, 730, L31 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Howard, A. W., Marcy, G. W., Bryson, S. T., et al. 2011, ApJ, submitted [arXiv:1103.2541] [Google Scholar]

- Levrard, B., Winisdoerffer, C., & Chabrier, G. 2009, ApJ, 692, L9 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lissauer, J. J., Ragozzine, D., Fabrycky, D. C., et al. 2011, ApJS, 197, 8 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Magain, P. 1984, A&A, 134, 189 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumura, S., Pudritz, R. E., & Thommes, E. W. 2007, ApJ, 660, 1609 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumura, S., Peale, S. J., & Rasio, F. A. 2010, ApJ, 725, 1995 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Maxted, P. F. L., Anderson, D. R., Collier Cameron, A., et al. 2011, PASP, 123, 547 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Nagasawa, M., Ida, S., & Bessho, T. 2008, ApJ, 678, 498 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Naoz, S., Farr, W. M., Lithwick, Y., Rasio, F. A., & Teyssandier, J. 2011, Nature, 473, 187 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Penev, K., & Sasselov, D. 2011, ApJ, 731, 67 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pollacco, D. L., Skillen, I., Collier Cameron, A., et al. 2006, PASP, 118, 1407 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pollacco, D., Skillen, I., Collier Cameron, A., et al. 2008, MNRAS, 385, 1576 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Queloz, D., Henry, G. W., Sivan, J. P., et al. 2001, A&A, 379, 279 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Rasio, F. A., Tout, C. A., Lubow, S. H., & Livio, M. 1996, ApJ, 470, 1187 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sasselov, D. D. 2003, ApJ, 596, 1327 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, J., Dedieu, C., Le Sidaner, P., Savalle, R., & Zolotukhin, I. 2011, A&A, 532, A79 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Southworth, J. 2009, MNRAS, 394, 272 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Southworth, J. 2011, MNRAS, 417, 2166 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Triaud, A. H. M. J. 2010, A&A, 524, A25 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Winn, J. N., Fabrycky, D., Albrecht, S., & Johnson, J. A. 2010, ApJ, 718, L145 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Winn, J. N., Matthews, J. M., Dawson, R. I., et al. 2011a, ApJ, 737, L18 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Winn, J. N., Albrecht, S., Johnson, J. A., et al. 2011b, ApJ, 741, L1 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Zacharias, N., Finch, C., Girard, T., et al. 2010, AJ, 139, 2184 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

All Tables

All Figures

|

Fig. 1 (Top) The WASP-South lightcurve folded on the 0.81-d transit period. (Second panel) The binned WASP data with (offset) the TRAPPIST (I+z) and Euler (Gunn r) transit lightcurves, with the fitted MCMC model. (Third) The CORALIE radial velocities with the fitted model. (Lowest) The bisector spans; the absence of any correlation with radial velocity is a check against transit mimics. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 2 A periodogram of the 2009 WASP-South photometry, showing a 15.6-d modulation. The horizontal lines show the 0.01 and 0.001 false-alarm probability levels. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 3 Evolutionary tracks on a modified H–R diagram ( |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 4 Mass versus semi-major axis for confirmed planets, where both are known, as compiled by Schneider et al. (2011). Some planets are labelled with abbreviated names. |

| In the text | |

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.