| Issue |

A&A

Volume 520, September-October 2010

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A61 | |

| Number of page(s) | 5 | |

| Section | Interstellar and circumstellar matter | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201014841 | |

| Published online | 04 October 2010 | |

C I observations in the CQ Tauri proto-planetary disk: evidence of a very low gas-to-dust ratio ?![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

E. Chapillon1 - B. Parise1 - S. Guilloteau2,3 - A. Dutrey2,3 - V. Wakelam2,3

1 - MPIfR, Auf dem Hügel 69, 53121 Bonn, Germany

2 -

Université de Bordeaux, Observatoire Aquitain des Sciences de l'Univers, BP 89, 33271 Floirac Cedex, France

3 - CNRS, UMR 5804, Laboratoire d'Astrophysique de Bordeaux, BP 89, 33271 Floirac Cedex, France

Received 21 April 2010 / Accepted 18 June 2010

Abstract

Context. The gas and dust dissipation processes of

proto-planetary disks are hardly known. Transition disks between Class

II (proto-planetary disks) and Class III (debris disks) remain

difficult to detect.

Aims. We investigate the carbon chemistry of the peculiar

CQ Tau gas disk. It is likely to be a transition disk because it

exhibits weak CO emission with a relatively strong millimeter

continuum, indicating that the disk may currently be dissipating its

gas content.

Methods. We used APEX to observe the two C I transitions

![]() at 492 GHz and

at 492 GHz and

![]() at 809 GHz in the disk orbiting CQ Tau. We compare the

observations to several chemical model predictions. We focus our study

on the influence of the stellar UV radiation shape and gas-to-dust

ratio.

at 809 GHz in the disk orbiting CQ Tau. We compare the

observations to several chemical model predictions. We focus our study

on the influence of the stellar UV radiation shape and gas-to-dust

ratio.

Results. We did not detect the C I lines. However, our upper limits are deep enough to exclude high-C I models. The only available models compatible with our limits imply very low gas-to-dust ratios, of the order of only a few.

Conclusions. These observations strengthen the hypothesis that

CQ Tau is likely to be a transition disk and suggest that gas

disappears before dust.

Key words: circumstellar matter - protoplanetary disks - stars: individual: CQ Tau - radio lines: stars

1 Introduction

Gas and dust disks orbiting pre-main-sequence stars are believed to be the birthplace of planetary systems. Several disks surrounding young stars have been detected and studied in both continuum and molecular lines at mm/submm wavelengths (e.g., Piétu et al. 2007, and references therein). However, little is known about how their gas and dust content dissipate. Transition disks between Class II (proto-planetary disks) and Class III (debris disks) remain hard to detect. Accretion, viscous spreading, planet formation, and photo-evaporation (enhanced by grain growth and dust settling) should all play a role in the disappearance of the gas and dust disk, but their relative importances have not yet been estimated.

Disks with a strong mm continuum excess and weak CO lines are

interesting in this respect, as they may represent a stage in which gas

is being dissipated, while large dust grains responsible for the mm

continuum persist, perhaps settling within the mid-plane. The first

case discovered was BP Tau, which exhibits a warm (50 K), small

(radius ![]() 120 AU) disk with a very low CO to dust ratio (Dutrey et al. 2003), corresponding to an apparent depletion factor of 100 for CO. Chapillon et al. (2008, hereafter Paper I)

found that the Herbig Ae (HAe) stars CQ Tau and MWC 758 have disks with similar characteristics.

120 AU) disk with a very low CO to dust ratio (Dutrey et al. 2003), corresponding to an apparent depletion factor of 100 for CO. Chapillon et al. (2008, hereafter Paper I)

found that the Herbig Ae (HAe) stars CQ Tau and MWC 758 have disks with similar characteristics.

Chapillon et al. (2008) showed

that such a low CO to dust ratio can be explained by photo-dissociation

by UV photons coming from the star with a standard gas-to-dust mass

ratio. However, solutions with low gas-to-dust ratio also exist. These

solutions differ in terms of the amount of atomic and/or ionized carbon

produced by the CO photo-dissociation. Thus, detection of either

C I or C+ provides a useful diagnostic of the disk structure.

An upper limit to the C I

![]() transition in the Herbig Be star HD 100546 has been recently reported by Panic et al. (2010).

transition in the Herbig Be star HD 100546 has been recently reported by Panic et al. (2010).

Here we report on a search for C I in CQ Tau. We present our observations in Sect. 2. Our results are discussed and compared with chemical modeling in Sect. 3. We summarize our study in the last section.

2 Observations and results

We selected CQ Tau as our main target, because it appears to be the warmest source: the mm continuum and 12CO

observations of Paper I indicate a gas temperature >50 K,

a disk outer radius near 250 AU, and an apparent CO depletion of

100. CQ Tau (see Table 1) is one of the oldest HAe stars (![]() 6-10 Myr),

although a revision of its distance implies that CQ Tau is younger

than initially understood (see Paper I). It is surrounded by a

resolved disk (Mannings & Sargent 1997; Doucet et al. 2006). This star exhibits an UX-Ori-like variability (Natta et al. 1997),

in contradiction with the observed low disk inclination (Paper I).

Its dust emissivity exponent is about 0.7 (Paper I and Testi et al. 2003), indicating significant grain growth.

6-10 Myr),

although a revision of its distance implies that CQ Tau is younger

than initially understood (see Paper I). It is surrounded by a

resolved disk (Mannings & Sargent 1997; Doucet et al. 2006). This star exhibits an UX-Ori-like variability (Natta et al. 1997),

in contradiction with the observed low disk inclination (Paper I).

Its dust emissivity exponent is about 0.7 (Paper I and Testi et al. 2003), indicating significant grain growth.

Table 1: Properties of CQ Tau, also named HD 36910.

We observed simultaneously the C I

![]() and

and

![]() lines in CQ Tau with FLASH (Heyminck et al. 2006) on APEX during August 2009 in excellent weather conditions (pwv

lines in CQ Tau with FLASH (Heyminck et al. 2006) on APEX during August 2009 in excellent weather conditions (pwv ![]() mm). We used wobbler mode (60''). The total integration time on source is 67 min.

Pointing and focus were frequently checked on Mars (the planet was very close to the source, see Table 2).

Receiver tuning was checked on the Orion Bar (Fig. 1).

Our observation of C I

mm). We used wobbler mode (60''). The total integration time on source is 67 min.

Pointing and focus were frequently checked on Mars (the planet was very close to the source, see Table 2).

Receiver tuning was checked on the Orion Bar (Fig. 1).

Our observation of C I

![]() towards the Orion Bar peaks at

towards the Orion Bar peaks at

![]() K. Taking the beam efficiency measured toward the Moon

K. Taking the beam efficiency measured toward the Moon ![]() 0.8 (the emission being extended), this leads to a peak temperature of

0.8 (the emission being extended), this leads to a peak temperature of

![]() K.

This is in quite good agreement with previous observations of C I at 492 GHz toward the Orion Bar by Tauber et al. (1995) with the CSO 10.4 m dish (15'' beam, our pointing is in-between that of their ``d'' and ``e'' spectra, i.e.,

K.

This is in quite good agreement with previous observations of C I at 492 GHz toward the Orion Bar by Tauber et al. (1995) with the CSO 10.4 m dish (15'' beam, our pointing is in-between that of their ``d'' and ``e'' spectra, i.e.,

![]() K, see their Figs. 1 and 2).

K, see their Figs. 1 and 2).

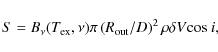

The spectra towards CQ Tau are presented in Fig. 2. We did not detect any C I emission. The 1![]() sensitivity on the integrated area is given by the following formula

sensitivity on the integrated area is given by the following formula

![]() ,

where

,

where

![]() is the spectral resolution and

is the spectral resolution and ![]() the line width. We take

the line width. We take

![]() km s-1according to the PdBI CO observations (Paper I). The rms noise in Fig. 2 are (1

km s-1according to the PdBI CO observations (Paper I). The rms noise in Fig. 2 are (1![]() )

rms 0.020 and 0.046 K

(

)

rms 0.020 and 0.046 K

(![]() )

for a spectral resolution of 1.04 and 0.95 km s-1 at 492 and 809 GHz, respectively. Taking the conversion

factors between Jansky and Kelvin to be equal to 48 and 70 Jy K-1, we thus obtain

)

for a spectral resolution of 1.04 and 0.95 km s-1 at 492 and 809 GHz, respectively. Taking the conversion

factors between Jansky and Kelvin to be equal to 48 and 70 Jy K-1, we thus obtain ![]() upper limits of

6.6 Jy km s-1 and 25 Jy km s-1 for the

upper limits of

6.6 Jy km s-1 and 25 Jy km s-1 for the

![]() and

and

![]() lines (see Table 4).

lines (see Table 4).

| Figure 1:

C I

|

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| Figure 2:

(a) C I

|

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

Table 2: Sources coordinates (J2000).

3 Discussion

3.1 Chemical modeling

Table 3: Elemental abundances with respect to total hydrogen.

![\begin{figure}\par

\includegraphics[width=4.7cm,angle=270]{14841fg3.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/12/aa14841-10/Timg37.png)

|

Figure 3: Radial distribution of the surface density of C+, C I, and CO for three models that are in agreement with the CO observations. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}\par

\includegraphics[angle=270,width=18cm]{14841fg4.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/12/aa14841-10/Timg38.png)

|

Figure 4: Vertical distribution of the abundance of C+ (blue), C I (green), and CO (red) and gas temperature (pink dashed lines) for the three models that are in agreement with the CO observations. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

We use the PDR code from the Meudon group (Le Petit et al. 2006; Le Bourlot et al. 1993) with the modification of the extinction curve calculation according to the grain size distribution described in Paper I. The chemical network and elemental abundances (given in Table 3) are similar to that of Goicoechea et al. (2006). No freeze-out onto grains is considered, as the gas temperature determined by CO observation is >50 K. We solve the radiative transfer perpendicular to the disk plane for each radii, with an incident UV flux scaling as 1/r2. Radiative transfer, chemistry, and thermal balance are consistently calculated. For more details and a description of the use of the code we refer to Paper I.

From Paper I, the models of ours that reproduce most

closely the CO depletion and gas temperature in CQ Tau are: 1) a

disk illuminated by a strong UV field from the star (Draine field with

a scaling factor

![]() at R=100 AU) with a normal gas-to-dust ratio (g/d = 100, model A), or 2) a disk illuminated by a weaker UV field (

at R=100 AU) with a normal gas-to-dust ratio (g/d = 100, model A), or 2) a disk illuminated by a weaker UV field (

![]() )

with a modified g/d

ratio of 10 (model B). In both cases, we considered large grains

with a maximum size of 1 cm as suggested by the previous dust and

CO observations. The computed surface densities and abundances of CO,

C I, and C II are shown in Figs. 3 and 4, left and middle panels.

A cut perpendicular to the disk mid-plane in our models A and B shows three parts (Fig. 4). At 100 AU radius, C+ is the most abundance form of carbon in the upper layer, then there is a transition layer where C I is quasi-dominant and finally CO is the main carbon-component in the mid-plane. At larger radii (200 AU), C+

remains however the dominant carbon-component even in the disk

mid-plane, because the total opacity perpendicular to the disk

mid-plane is low.

)

with a modified g/d

ratio of 10 (model B). In both cases, we considered large grains

with a maximum size of 1 cm as suggested by the previous dust and

CO observations. The computed surface densities and abundances of CO,

C I, and C II are shown in Figs. 3 and 4, left and middle panels.

A cut perpendicular to the disk mid-plane in our models A and B shows three parts (Fig. 4). At 100 AU radius, C+ is the most abundance form of carbon in the upper layer, then there is a transition layer where C I is quasi-dominant and finally CO is the main carbon-component in the mid-plane. At larger radii (200 AU), C+

remains however the dominant carbon-component even in the disk

mid-plane, because the total opacity perpendicular to the disk

mid-plane is low.

3.2 The UV problem

As indicated in Paper I (Sect. 5.2), the actual UV spectra of HAe stars are not well known. Observations of MWC 758 indicate a UV spectrum shortwards of 1500The CO abundance appears very sensitive to the UV profile. In absence of a UV excess and in the case that g/d = 100 the chemistry is dramatically affected. The disk is mainly molecular and the C/CO transition occurs at low opacities (i.e. closer to the disk atmosphere). This model leads however to too high CO surface densities (see Fig. 5, left panel). With g/d = 10 (Model C, see Figs. 3 and 4), the CO surface densities are of the same order of magnitude as in model B and therefore also compatible with CO observations frome Paper I, but now the gas is warmer and there is more C I than C+ (C I being the main carbon form in the mid-plane).

Bergin et al. (2003) demonstrated that the UV excess of T Tauri stars is dominated by strong emission lines, in particular Lyman ![]() .

We therefore explored the influence of the shape of the UV spectrum by studying the impact of the Lyman

.

We therefore explored the influence of the shape of the UV spectrum by studying the impact of the Lyman ![]() line at 1215

line at 1215 ![]() .

We performed a couple of runs with a modified stellar spectrum, i.e., a

photospheric spectrum with an additional line, and the two gas-to-dust

ratios (10 and 100). The effects on the surface densities of CO, C I,

and C+ were found to be negligible.

.

We performed a couple of runs with a modified stellar spectrum, i.e., a

photospheric spectrum with an additional line, and the two gas-to-dust

ratios (10 and 100). The effects on the surface densities of CO, C I,

and C+ were found to be negligible.

3.3 Elemental depletion

Another possible way of explaining the lack of CO and C I in this object is that, even with a normal g/d,

the C, and O elemental abundances may be lower than thoses adopted here

(e.g., by depletion onto grain surfaces). We ran a model with a stellar

UV field including a UV excess (![]() ), a standard value of g/d (100) and an elemental depletion factor of 10 of heavy elements (see Fig. 5, right panel). The amount of C I is in reasonable agreement with our observation but the CO is largely overestimated. The larger amount of CO relative to the g/d = 10 and standard abundances case is due to the mutual shielding by H2. An unlikely elemental depletion of

), a standard value of g/d (100) and an elemental depletion factor of 10 of heavy elements (see Fig. 5, right panel). The amount of C I is in reasonable agreement with our observation but the CO is largely overestimated. The larger amount of CO relative to the g/d = 10 and standard abundances case is due to the mutual shielding by H2. An unlikely elemental depletion of ![]() 100 is required to match the observations of both CO and C I.

100 is required to match the observations of both CO and C I.

![\begin{figure}\par

\includegraphics[origin=rb,width=4.5cm,angle=270]{14841fg5.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/12/aa14841-10/Timg44.png)

|

Figure 5: Radial distribution of the surface density of C+, C I, and CO for two models that are not in agreement with the CO observations. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Table 4: Observed and predicted line flux.

3.4 Spectrum predictions

Characteristic flux densities can be recovered by noting that an approximate integrated line flux is given by

|

where

We used the radiative transfer code DISKFIT optimized for disks (Piétu et al. 2007; Pavlyuchenkov et al. 2007) to make more accurate predictions about the C I line profiles and integrated intensities from our models. The model surface densities were extrapolated using simple power-laws

![]() .

The disk parameters (size, temperature, Keplerian velocity,

inclination, and turbulent width) were taken from Paper I. Our

values of

.

The disk parameters (size, temperature, Keplerian velocity,

inclination, and turbulent width) were taken from Paper I. Our

values of

![]() and p and the line flux predictions using Tk = 50 and 100 K are given in Table 4, with the observed upper limits. The value of the gas temperature Tk = 100 K is obtained from the best-fit model of the J=2-1 CO line, and 50 K is a lower limit, although this temperature provides a closer fit to the CO J=3-2 spectrum obtained at JCMT by Dent et al. (2005). Non-LTE effects are expected to be negligible, because the C I transitions have low critical densities of the order of <

104 cm-3 (Schroder et al. 1991; Monteiro & Flower 1987), while in our model, the C I layer is located in a high density region (

and p and the line flux predictions using Tk = 50 and 100 K are given in Table 4, with the observed upper limits. The value of the gas temperature Tk = 100 K is obtained from the best-fit model of the J=2-1 CO line, and 50 K is a lower limit, although this temperature provides a closer fit to the CO J=3-2 spectrum obtained at JCMT by Dent et al. (2005). Non-LTE effects are expected to be negligible, because the C I transitions have low critical densities of the order of <

104 cm-3 (Schroder et al. 1991; Monteiro & Flower 1987), while in our model, the C I layer is located in a high density region (![]() -106 cm-3).

-106 cm-3).

Considering the uncertainty in the temperature, the non-detection of both C I lines excludes the high C I models (A and C). It is just marginally consistent with the low g/d, non-photospheric UV spectrum model (B), provided the kinetic temperature does not exceed 50 K. In this case, the C I lines are mostly optically thin, and only the line wings originating in the inner regions because of the Keplerian rotation are optically thick.

3.5 Comparison with other models

Although no specific modeling of the CQ Tau disk and star system has been already published, it is worth comparing our results with predictions from other chemical studies.The chemistry of HAe disks was also studied by Jonkheid et al. (2007), with different assumptions than in our study.

The UV transfer is performed with a 2D code (van Zadelhoff et al. 2003), whereas in our case this is a 1D method. The self-shielding of H2

and CO are calculated assuming a constant molecular abundance whereas

we compute it explicitly. Moreover, they mimic the dust growth (and/or

settling) decreasing the mass of the small grains (i.e., interstellar

grains) and consider PAHs. The radiation field is a NEXTGEN spectrum

(which is a pure photospheric spectrum). Low CO amounts can be

reproduced by their model B4. They predict that C I is the main form of

carbon (their Fig. 6), in agreement with our model C (photospheric

spectrum and low gas-to-dust ratio). Jonkheid et al. model B4

yields integrated line intensities of about 1-1.3 K km s-1 for a beam size of 6.7'', an inclination of 45![]() and a turbulent width of 0.2 km s-1. This corresponds to 8-11 and 24-29 Jy km s-1 for the 492 and 809 GHz lines, respectively (Table 4). Taking the 1.3 mm flux from CQ Tau and using an absorption coefficient of 2 cm2 g-1 (per gram of dust) with a dust temperature of 50 K, the estimated dust mass is

and a turbulent width of 0.2 km s-1. This corresponds to 8-11 and 24-29 Jy km s-1 for the 492 and 809 GHz lines, respectively (Table 4). Taking the 1.3 mm flux from CQ Tau and using an absorption coefficient of 2 cm2 g-1 (per gram of dust) with a dust temperature of 50 K, the estimated dust mass is

![]() .

This is likely a lower limit, as the adopted absorption coefficient is large. The gas mass in the most appropriate model from Jonkheid et al. (2007) is

.

This is likely a lower limit, as the adopted absorption coefficient is large. The gas mass in the most appropriate model from Jonkheid et al. (2007) is

![]() ,

which would imply a gas-to-dust ratio of only

,

which would imply a gas-to-dust ratio of only ![]() 2. Our best model (B) with g/d = 10 predicts somewhat too strong lines. From Table 4, since the C I lines are close to the optically thin regime, a reduction in g/d

by a factor of 2-3 may bring model and observations in agreement. Thus,

whichever chemical model of HAe disk we consider, the CO observations

and the measured upper limits on both C I lines can only be reproduced by a very low gas-to-dust ratio.

2. Our best model (B) with g/d = 10 predicts somewhat too strong lines. From Table 4, since the C I lines are close to the optically thin regime, a reduction in g/d

by a factor of 2-3 may bring model and observations in agreement. Thus,

whichever chemical model of HAe disk we consider, the CO observations

and the measured upper limits on both C I lines can only be reproduced by a very low gas-to-dust ratio.

Although a factor of a few may be within the modeling uncertainties, it appears difficult to reconcile the current constraints on CO and C I with gas to dust ratios higher than 10.

The influence of X-rays is not taken into account neither in our PDR code, nor in Jonkheid et al. (2007). Although their

![]() are lower, on average, HAe stars are as strong X-ray emitters as T Tauri stars (Skinner et al. 2004).

No specific model exists for HAe disks, but studies appropriate to

T Tauri stars indicate that X-rays are expected to increase the

C I intensity (Ercolano et al. 2009; Meijerink et al. 2008; Gorti & Hollenbach 2008). We thus do not expect the (unknown) X-ray luminosity of CQ Tau to affect our conclusions.

are lower, on average, HAe stars are as strong X-ray emitters as T Tauri stars (Skinner et al. 2004).

No specific model exists for HAe disks, but studies appropriate to

T Tauri stars indicate that X-rays are expected to increase the

C I intensity (Ercolano et al. 2009; Meijerink et al. 2008; Gorti & Hollenbach 2008). We thus do not expect the (unknown) X-ray luminosity of CQ Tau to affect our conclusions.

Another possibility is that models over-predict C I because of the inaccurate treatment of the physical processes. While this cannot be excluded, we note however that the two existing HAe disk chemical models make very different approximations (one about the radiative transfer, the other about the self-shielding), and yet converge towards similar predictions.

4 Summary

Our observations of the C I

![]() and

and

![]() transitions

in the CQ Tau disk leads to significant upper limits, which allow

us to reject chemical models producing a large amount of C I. The absence of C I

emission together with the low CO emission can be explained by

currently available chemical models of HAe disks, only if the

gas-to-dust ratio is notably low (of order 2-5) in the CQ Tau

disk. This suggests that the CQ Tau disk is in a transition stage

between the proto-planetary and debris disk phases.

This work also allows us to conclude:

transitions

in the CQ Tau disk leads to significant upper limits, which allow

us to reject chemical models producing a large amount of C I. The absence of C I

emission together with the low CO emission can be explained by

currently available chemical models of HAe disks, only if the

gas-to-dust ratio is notably low (of order 2-5) in the CQ Tau

disk. This suggests that the CQ Tau disk is in a transition stage

between the proto-planetary and debris disk phases.

This work also allows us to conclude:

- 1.

- PDR models that reproduce the CO data are qualitatively compatible with our upper limits, but still overestimate the total amount of C I unless the gas-to-dust ratio is of the order of a few.

- 2.

- The C I surface density is sensitive to the shape of the UV spectrum, with neutral carbon being the dominant species in the absence of UV excess.

- 3.

- Introducing the Lyman

line in the stellar UV spectrum does not change the C I surface density.

line in the stellar UV spectrum does not change the C I surface density.

- 4.

- All models matching the low CO and C I intensities predict that Carbon should be mainly in the ionized form C+. That could be tested by Sofia or Herschel observations. With a complete census of CO, C I, and C+, the overall surface density of gas-phase carbon will be constrained, allowing a more reliable estimate of the g/d ratio.

E.C. and B.P. are supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) under the Emmy Noether project PA 1692/1-1. S.G., A.D. and V.W. are financially supported by the French program ``Physique Chimie du Milieu Interstellaire'' (PCMI) from CNRS/INSU.

References

- Bergin, E., Calvet, N., D'Alessio, P., & Herczeg, G. J. 2003, ApJ, 591, L159 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Blondel, P. F. C., & Djie, H. R. E. T. A. 2006, A&A, 456, 1045 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Chapillon, E., Guilloteau, S., Dutrey, A., & Piétu, V. 2008, A&A, 488, 565, (Paper I) [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Dent, W. R. F., Greaves, J. S., & Coulson, I. M. 2005, MNRAS, 359, 663 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Doucet, C., Pantin, E., Lagage, P. O., & Dullemond, C. P. 2006, A&A, 460, 117 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Dutrey, A., Guilloteau, S., & Simon, M. 2003, A&A, 402, 1003 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Ercolano, B., Drake, J. J., & Clarke, C. J. 2009, A&A, 496, 725, (E09) [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Goicoechea, J. R., Pety, J., Gerin, M., et al. 2006, A&A, 456, 565 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Gorti, U., & Hollenbach, D. 2008, ApJ, 683, 287, (GH08) [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Grady, C. A., Woodgate, B. E., Bowers, C. W., et al. 2005, ApJ, 630, 958 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Guilloteau, S., & Dutrey, A. 1998, A&A, 339, 467 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Heyminck, S., Kasemann, C., Güsten, R., de Lange, G., & Graf, U. U. 2006, A&A, 454, L21 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Jonkheid, B., Dullemond, C. P., Hogerheijde, M. R., & van Dishoeck, E. F. 2007, A&A, 463, 203 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Le Bourlot, J., Pineau Des Forets, G., Roueff, E., & Flower, D. R. 1993, A&A, 267, 233 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Le Petit, F., Nehmé, C., Le Bourlot, J., & Roueff, E. 2006, ApJS, 164, 506 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Mannings, V., & Sargent, A. I. 1997, ApJ, 490, 792 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Meijerink, R., Glassgold, A. E., & Najita, J. R. 2008, ApJ, 676, 518 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro, T. S., & Flower, D. R. 1987, MNRAS, 228, 101 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Natta, A., Grinin, V. P., Mannings, V., & Ungerechts, H. 1997, ApJ, 491, 885 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Panic, O., van Dishoeck, E. F., Hogerheijde, M. R., et al. 2010, A&A, 519, A110 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlyuchenkov, Y., Semenov, D., Henning, T., et al. 2007, ApJ, 669, 1262 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Piétu, V., Dutrey, A., & Guilloteau, S. 2007, A&A, 467, 163 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Schroder, K., Staemmler, V., Smith, M. D., Flower, D. R., & Jaquet, R. 1991, J. Phys. B At. Mol. Phys., 24, 2487 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner, S. L., Güdel, M., Audard, M., & Smith, K. 2004, ApJ, 614, 221 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Tauber, J. A., Lis, D. C., Keene, J., Schilke, P., & Buettgenbach, T. H. 1995, A&A, 297, 567 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Testi, L., Natta, A., Shepherd, D. S., & Wilner, D. J. 2003, A&A, 403, 323 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- van Zadelhoff, G.-J., Aikawa, Y., Hogerheijde, M. R., & van Dishoeck, E. F. 2003, A&A, 397, 789 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

Footnotes

- ... ?

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- Based on observations carried out with the Atacama Pathfinder Experiment. APEX is a collaboration between the Max-Planck-Institut für Radioastronomie, the European Southern Observatory, and the Onsala Space Observatory.

- ... database

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- http://kurucz.harvard.edu/

All Tables

Table 1: Properties of CQ Tau, also named HD 36910.

Table 2: Sources coordinates (J2000).

Table 3: Elemental abundances with respect to total hydrogen.

Table 4: Observed and predicted line flux.

All Figures

| |

Figure 1:

C I

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

| |

Figure 2:

(a) C I

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}\par

\includegraphics[width=4.7cm,angle=270]{14841fg3.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/12/aa14841-10/Timg37.png)

|

Figure 3: Radial distribution of the surface density of C+, C I, and CO for three models that are in agreement with the CO observations. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}\par

\includegraphics[angle=270,width=18cm]{14841fg4.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/12/aa14841-10/Timg38.png)

|

Figure 4: Vertical distribution of the abundance of C+ (blue), C I (green), and CO (red) and gas temperature (pink dashed lines) for the three models that are in agreement with the CO observations. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}\par

\includegraphics[origin=rb,width=4.5cm,angle=270]{14841fg5.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/12/aa14841-10/Timg44.png)

|

Figure 5: Radial distribution of the surface density of C+, C I, and CO for two models that are not in agreement with the CO observations. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

Copyright ESO 2010

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.