| Issue |

A&A

Volume 517, July 2010

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A65 | |

| Number of page(s) | 14 | |

| Section | Cosmology (including clusters of galaxies) | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201014116 | |

| Published online | 06 August 2010 | |

Internal dynamics of Abell 2294: a massive, likely merging cluster

M. Girardi1,2 - W. Boschin3 - R. Barrena4,5

1 - Dipartimento di Fisica dell' Università degli

Studi di Trieste - Sezione di Astronomia, via Tiepolo 11, 34143

Trieste, Italy

2 - INAF - Osservatorio Astronomico di Trieste, via Tiepolo 11, 34143 Trieste, Italy

3 - Fundación Galileo Galilei - INAF, Rambla José Ana Fernández Perez 7, 38712

Breña Baja (La Palma), Canary Islands, Spain

4 - Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias, C/Vía Láctea s/n, 38205 La

Laguna (Tenerife), Canary Islands, Spain

5 - Departamento de Astrofísica, Universidad de La Laguna, Av. del

Astrofísico Franciso Sánchez s/n, 38205 La Laguna

(Tenerife), Canary Islands, Spain

Received 22 January 2010 / Accepted 18 April 2010

Abstract

Context. The mechanisms giving rise to diffuse radio

emission in galaxy clusters, and in particular their connection with

cluster mergers, are still debated.

Aims. We seek to explore the internal dynamics of the cluster Abell 2294, which has been shown to host a radio halo.

Methods. Our analysis is mainly based on redshift data for 88

galaxies acquired at the Telescopio Nazionale Galileo. We combine

galaxy velocities and positions to select 78 cluster galaxies and

analyze its internal dynamics. We also use both photometric data

acquired at the Isaac Newton Telescope and X-ray data from the Chandra

archive.

Results. We re-estimate the redshift of the large, brightest cluster galaxy (BCG) obtaining

![]() ,

which closely agrees with the mean cluster redshift. We estimate a quite large line-of-sight (LOS) velocity dispersion

,

which closely agrees with the mean cluster redshift. We estimate a quite large line-of-sight (LOS) velocity dispersion

![]() km s

km s![]() and X-ray temperature

and X-ray temperature

![]() keV.

Our optical and X-ray analyses detect substructure. Our results imply

that the cluster is composed of two massive subclusters separated by a

LOS rest frame velocity difference

keV.

Our optical and X-ray analyses detect substructure. Our results imply

that the cluster is composed of two massive subclusters separated by a

LOS rest frame velocity difference

![]() km s-1,

very closely projected in the plane of sky along the SE-NW direction.

This observational picture, interpreted in terms of the analytical

two-body model, suggests that Abell 2294 is a cluster merger elongated

mainly in the LOS direction and captured during the bound outgoing

phase, a few fractions of Gyr after the core crossing. We find that

Abell 2294 is a very massive cluster with a range of M=2-4

km s-1,

very closely projected in the plane of sky along the SE-NW direction.

This observational picture, interpreted in terms of the analytical

two-body model, suggests that Abell 2294 is a cluster merger elongated

mainly in the LOS direction and captured during the bound outgoing

phase, a few fractions of Gyr after the core crossing. We find that

Abell 2294 is a very massive cluster with a range of M=2-4

![]() ,

depending on the adopted model. In contrast to previous findings, we find no evidence of H

,

depending on the adopted model. In contrast to previous findings, we find no evidence of H![]() emission in the spectrum of the BCG galaxy.

emission in the spectrum of the BCG galaxy.

Conclusions. The emerging picture of Abell 2294 is that of a

massive, quite ``normal'' merging cluster, like many clusters hosting

diffuse radio sources. However, perhaps because of its particular

geometry, more data are needed for reach a definitive, more

quantitative conclusion.

Key words: galaxies: clusters: individual: Abell 2294 - galaxies: clusters: general - galaxies: kinematics and dynamics

1 Introduction

Merging processes constitute an essential ingredient of the evolution

of galaxy clusters (see Feretti et al. 2002b, for a review). An

interesting aspect of these phenomena is the possible connection

between cluster mergers and extended, diffuse radio sources: halos and

relics. The synchrotron radio emission of these sources demonstrates

the existence of large-scale cluster magnetic fields and of

widespread relativistic particles. Cluster mergers have been proposed

to provide the large amount of energy necessary for electron

reacceleration to relativistic energies and for magnetic field

amplification (Tribble 1993; Feretti 1999, 2002a; Sarazin 2002). Radio relics (``radio gischts'' as referred to by Kempner et al. 2004), which are polarized

and elongated radio sources located in the cluster peripheral regions,

seem to be directly associated with merger shocks (e.g., Ensslin et al. 1998; Roettiger et al. 1999; Ensslin &

Gopal-Krishna 2001; Hoeft et al. 2004). Radio halos,

unpolarized sources that permeate the cluster volume in a similar way

to the X-ray emitting gas (intracluster medium, hereafter ICM), are

more likely to be associated with the turbulence following a cluster

merger (Cassano & Brunetti 2005; Brunetti et al. 2009). However, the precise radio halos/relics formation

scenario remains unclear because diffuse radio sources are quite

uncommon and one has been able to study these phenomena only recently

on the basis of a sufficient statistics (few dozen clusters up to

![]() ,

e.g., Giovannini et al. 1999; see also Giovannini

& Feretti 2002; Feretti 2005; Giovannini et al. 2009) and attempt a classification (e.g., Kempner et al. 2004; Ferrari et al. 2008). It is expected that new telescopes will largely increase the statistics of diffuse sources

(e.g., LOFAR, Cassano et al. 2009).

,

e.g., Giovannini et al. 1999; see also Giovannini

& Feretti 2002; Feretti 2005; Giovannini et al. 2009) and attempt a classification (e.g., Kempner et al. 2004; Ferrari et al. 2008). It is expected that new telescopes will largely increase the statistics of diffuse sources

(e.g., LOFAR, Cassano et al. 2009).

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=18cm,clip]{14116fg01.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/09/aa14116-10/Timg29.png)

|

Figure 1: INT R-band image of the cluster A2294 (north at the top and east to the left) with, superimposed, the contour levels of the Chandra archival image ID 3246 (thick contours; photons in the energy range 0.5-2 keV) and the contour levels of a VLA radio image at 1.4 GHz (thin contours, see Giovannini et al. 2009). Labels and arrows highlight the positions of radio sources listed by Rizza et al. (2003). |

| Open with DEXTER | |

From the observational point of view, there is growing evidence of the connection between diffuse radio emission and cluster merging, since up to now diffuse radio sources have been detected only in merging systems. In several cases the cluster dynamical state has been derived from X-ray observations (see Buote 2002; Feretti 2008, 2006, and refs. therein). Optical data are a powerful way to investigate the presence and the dynamics of cluster mergers (e.g., Girardi & Biviano 2002), too. The spatial and kinematical analysis of member galaxies allow us to detect and measure the amount of substructure, and both identify and analyze possible pre-merging clumps or merger remnants. This optical information is really complementary to X-ray information since galaxies and the intra-cluster medium react on different timescales during a merger (see, e.g., numerical simulations by Roettiger et al. 1997).

In this context, we are conducting an intensive observational and data

analysis program to study the internal dynamics of clusters with

diffuse radio emission by using member galaxies (Girardi et al. 2007![]() ). Most clusters

exhibiting diffuse radio emission have a relatively high gravitational

mass (higher than

). Most clusters

exhibiting diffuse radio emission have a relatively high gravitational

mass (higher than

![]() within 2

h70-1 Mpc; see Giovannini

& Feretti 2002) and, indeed, most clusters we analyzed are

very massive clusters with few exceptions (Boschin et al. 2008).

within 2

h70-1 Mpc; see Giovannini

& Feretti 2002) and, indeed, most clusters we analyzed are

very massive clusters with few exceptions (Boschin et al. 2008).

During our observational program, we have conducted an intensive study

of the cluster Abell 2294 (hereafter A2294).

A2294 is a very rich, X-ray luminous, and hot Abell cluster: Abell

richness class =2 (Abell et al. 1989); ![]() (0.1-2.4 keV) =

(0.1-2.4 keV) =

![]() erg s-1;

erg s-1;

![]() -9 keV recovered from ROSAT and Chandra data

(Ebeling et al. 1998; Rizza et al. 1998;

Maughan et al. 2008). Optically, the cluster is classified as Bautz-Morgan class II (Abell et al. 1989) and is dominated by a central, large brightest

cluster galaxy (BCG, see Fig. 1).

-9 keV recovered from ROSAT and Chandra data

(Ebeling et al. 1998; Rizza et al. 1998;

Maughan et al. 2008). Optically, the cluster is classified as Bautz-Morgan class II (Abell et al. 1989) and is dominated by a central, large brightest

cluster galaxy (BCG, see Fig. 1).

According to both ROSAT and Chandra data, A2294 is known to have no cool core (Rizza et al. 1998; Bauer et al. 2005). As for the presence of possible substructure, using ROSAT data, Rizza et al. (1998) found evidence of a ``centroid shift'' and detected a southern excess in the X-ray emission. Using Chandra data, Hashimoto et al. (2007) classified A2294 as a ``distorted'' cluster because of the large value of its asymmetry parameter. Indeed, A2294 is a very peculiar cluster since, in contrast to the absence of a cooling core, it is very compact in its X-ray appearance (see Fig. 3 of Bauer et al. 2005). Among a sample of 115 clusters analyzed using Chandra data, A2294 has the smallest ellipticity, and exhibits a small, but highly significant, centroid shift (Maughan et al. 2008).

In another respect, A2294 is also peculiar. Out of a sample of 13 clusters at

![]() showing evidence for H

showing evidence for H![]() emission in their BCG spectrum, it is the only one that does not appear

to have a cool core (see Fig. 5 of Bauer et al. 2005). The correlation

between BCG H

emission in their BCG spectrum, it is the only one that does not appear

to have a cool core (see Fig. 5 of Bauer et al. 2005). The correlation

between BCG H![]() emission and the presence of a cool core is also

found for nearby clusters where ``H

emission and the presence of a cool core is also

found for nearby clusters where ``H![]() luminous galaxies lie at

the center of large cool cores, although this special cluster

environment does not guarantee the emission-line nebulosity in its

BCG'' (Peres et al. 1998). More recent observations also

agree that H

luminous galaxies lie at

the center of large cool cores, although this special cluster

environment does not guarantee the emission-line nebulosity in its

BCG'' (Peres et al. 1998). More recent observations also

agree that H![]() emission is more typical of cool core clusters

than of non-cool core clusters (

emission is more typical of cool core clusters

than of non-cool core clusters (![]()

![]() compared to

compared to ![]()

![]() ,

Edwards et al. 2007).

,

Edwards et al. 2007).

As for the diffuse radio emission, Owen et al. (1999) first

reported the existence of a detectable diffuse radio source in this

cluster. Despite the presence of some disturbing point-like sources

in the central region of the cluster, Giovannini et al. (2009)

were able to detect a radio-halo 3

![]() in size. In particular, the position

of A2294 in the

in size. In particular, the position

of A2294 in the

![]() (radio power at 1.4 GHz) -

(radio power at 1.4 GHz) - ![]() plane is consistent with that of all other radio-halo clusters

(see Fig. 17 of Giovannini et al. 2009).

plane is consistent with that of all other radio-halo clusters

(see Fig. 17 of Giovannini et al. 2009).

To date, only a small amount of optical data have been available. The

cluster redshift reported in the literature (z=0.178) is based only

on the BCG H![]() emission line (Crawford et al. 1995). Instead, the true cluster redshift, as estimated in this paper, is rather

emission line (Crawford et al. 1995). Instead, the true cluster redshift, as estimated in this paper, is rather

![]() fully consistent with

that measured for the BCG on the basis of our data, which, indeed, do not

show any evidence of H

fully consistent with

that measured for the BCG on the basis of our data, which, indeed, do not

show any evidence of H![]() emission (see Sect. 2).

emission (see Sect. 2).

Our new spectroscopic and photometric data come from the Telescopio Nazionale Galileo (TNG) and the Isaac Newton Telescope (INT), respectively. Our present analysis is based on these optical data and X-ray Chandra archival data.

This paper is organized as follows. We present our new optical data and the cluster catalog in Sect. 2. We present our results about the cluster structure based on optical and X-ray data in Sects. 3 and 4, respectively. We briefly discuss our results and present our conclusions in Sect. 5.

Unless otherwise stated, we indicate errors at the 68% confidence level

(hereafter c.l.). Throughout this paper, we use H0=70 km s-1 Mpc-1 in a

flat cosmology with

![]() and

and

![]() .

In the

adopted cosmology, 1

.

In the

adopted cosmology, 1

![]() corresponds to

corresponds to ![]() 173

h70-1 kpc

173

h70-1 kpc ![]() at the

cluster redshift.

at the

cluster redshift.

2 New data and galaxy catalog

Multi-object spectroscopic observations of A2294 were carried out at

the TNG telescope in December 2007 and August 2008. We used

DOLORES/MOS with the LR-B Grism 1, yielding a dispersion of 187 Å/mm. We used the new

![]() pixels E2V CCD, with a pixel

size of 13.5

pixels E2V CCD, with a pixel

size of 13.5 ![]() m. In total, we observed 4 MOS masks (3 in 2007 and

1 in 2008) for a total of 124 slits. We acquired three exposures of

1800 s for each mask. Wavelength calibration was performed using

helium-argon lamps. Reduction of spectroscopic data was carried out

using the IRAF

m. In total, we observed 4 MOS masks (3 in 2007 and

1 in 2008) for a total of 124 slits. We acquired three exposures of

1800 s for each mask. Wavelength calibration was performed using

helium-argon lamps. Reduction of spectroscopic data was carried out

using the IRAF![]() package. Radial

velocities were determined using the cross-correlation technique

(Tonry & Davis 1979) implemented in the RVSAO package

(developed at the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory Telescope Data

Center). Each spectrum was correlated against six templates for a

variety of galaxy spectral types: E, S0, Sa, Sb, Sc, and Ir (Kennicutt

1992). The template producing the highest value of

package. Radial

velocities were determined using the cross-correlation technique

(Tonry & Davis 1979) implemented in the RVSAO package

(developed at the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory Telescope Data

Center). Each spectrum was correlated against six templates for a

variety of galaxy spectral types: E, S0, Sa, Sb, Sc, and Ir (Kennicutt

1992). The template producing the highest value of ![]() ,

i.e., the parameter given by RVSAO and related to the

signal-to-noise ratio of the correlation peak, was chosen. Moreover,

all spectra and their best correlation functions

were examined visually to verify the redshift determination. In six

cases (IDs. 5, 13, 15, 60, 81, and 82; see Table 1),

we assumed the EMSAO redshift to be a reliable estimate of the

redshift.

,

i.e., the parameter given by RVSAO and related to the

signal-to-noise ratio of the correlation peak, was chosen. Moreover,

all spectra and their best correlation functions

were examined visually to verify the redshift determination. In six

cases (IDs. 5, 13, 15, 60, 81, and 82; see Table 1),

we assumed the EMSAO redshift to be a reliable estimate of the

redshift.

Our spectroscopic catalog lists 88 galaxies in the field of A2294.

Table 1: Velocity catalog of 88 spectroscopically measured galaxies in the field of the cluster A2294.

The nominal errors as given by the cross-correlation are known to be smaller than the true errors (e.g., Malumuth et al. 1992; Bardelli et al. 1994; Ellingson & Yee 1994; Quintana et al. 2000). Duplicate observations for the same galaxy allowed us to estimate the true intrinsic errors in data of the same quality taken with the same instrument (e.g. Barrena et al. 2007a,b). Here we have a limited number of double determinations (i.e., five galaxies from four different masks), thus we decided to apply the correction that had already been applied in above studies. Hereafter we assume that true errors are larger than nominal cross-correlation errors by a factor of 1.4. For the five galaxies with two redshift estimates, we used the weighted mean of the two measurements and the corresponding errors. The median error in cz is 71 km s-1.

Our photometric observations were carried out with the Wide Field

Camera (WFC), mounted at the prime focus of the 2.5 m INT telescope. We

observed A2294 in May 18th 2007 with filters ![]() and

and ![]() in photometric conditions and a seeing of

in photometric conditions and a seeing of ![]() 1.5

1.5

![]() .

.

The WFC consists of a four-CCD mosaic covering a

![]() field of view, with only a 20% marginally

vignetted area. We took nine exposures of 720 s in

field of view, with only a 20% marginally

vignetted area. We took nine exposures of 720 s in ![]() and 360 s in

and 360 s in ![]() Harris filters (a total of 6480 s and 3240 s in each

band) developing a dithering pattern of nine positions. This observing

mode allowed us to build a ``supersky'' frame that was used to correct

our images for fringing patterns (Gullixson 1992). In

addition, the dithering helped us to clean cosmic rays and avoid the

effects of gaps between the CCDs in the final images. Another problem

associated with the wide field frames is the distortion of the

field. To match the photometry of several filters, a good astrometric

solution is needed to take into account these distortions. Using the

imcoords IRAF tasks and taking as a reference the USNO B1.0 catalog,

we were able to find an accurate astrometric solution (rms

Harris filters (a total of 6480 s and 3240 s in each

band) developing a dithering pattern of nine positions. This observing

mode allowed us to build a ``supersky'' frame that was used to correct

our images for fringing patterns (Gullixson 1992). In

addition, the dithering helped us to clean cosmic rays and avoid the

effects of gaps between the CCDs in the final images. Another problem

associated with the wide field frames is the distortion of the

field. To match the photometry of several filters, a good astrometric

solution is needed to take into account these distortions. Using the

imcoords IRAF tasks and taking as a reference the USNO B1.0 catalog,

we were able to find an accurate astrometric solution (rms ![]() 0.4

0.4

![]() )

across the full frame. The photometric calibration was performed by observing standard Landolt fields (Landolt 1992).

)

across the full frame. The photometric calibration was performed by observing standard Landolt fields (Landolt 1992).

We finally identified galaxies in our ![]() and

and ![]() images and measured their magnitudes with the SExtractor package

(Bertin & Arnouts 1996) and AUTOMAG procedure. In a few cases

(e.g., close companion galaxies, galaxies close to defects of the CCD)

the standard SExtractor photometric procedure failed. In these cases,

we computed magnitudes by hand. This method consisted of assuming a

galaxy profile of a typical elliptical galaxy and scaling it to the

maximum observed value. The integration of this profile provided an

estimate of the magnitude. This method is similar to PSF photometry,

but assumes a galaxy profile, which is more appropriate in this case.

images and measured their magnitudes with the SExtractor package

(Bertin & Arnouts 1996) and AUTOMAG procedure. In a few cases

(e.g., close companion galaxies, galaxies close to defects of the CCD)

the standard SExtractor photometric procedure failed. In these cases,

we computed magnitudes by hand. This method consisted of assuming a

galaxy profile of a typical elliptical galaxy and scaling it to the

maximum observed value. The integration of this profile provided an

estimate of the magnitude. This method is similar to PSF photometry,

but assumes a galaxy profile, which is more appropriate in this case.

We transformed all magnitudes into the Johnson-Cousins system

(Johnson & Morgan 1953; Cousins 1976). We used

![]() and

and ![]() as derived from the Harris filter

characterization

as derived from the Harris filter

characterization![]() and

assuming a

and

assuming a

![]() for E-type galaxies (Poggianti

1997). As a final step, we estimated and corrected the

Galactic extinction

for E-type galaxies (Poggianti

1997). As a final step, we estimated and corrected the

Galactic extinction

![]() ,

,

![]() using Burstein &

Heiles's (1982) reddening maps. These values are especially

high because A2294 is immersed in a diffuse dust cloud soaring high

above the plane of our Milky Way Galaxy, and known as the Polaris Dust

Nebula. We estimated that our photometric sample is complete down to

R=22.0 (23.0) and B=23.5 (24.5) for S/N=5 (3) within the

observed field.

using Burstein &

Heiles's (1982) reddening maps. These values are especially

high because A2294 is immersed in a diffuse dust cloud soaring high

above the plane of our Milky Way Galaxy, and known as the Polaris Dust

Nebula. We estimated that our photometric sample is complete down to

R=22.0 (23.0) and B=23.5 (24.5) for S/N=5 (3) within the

observed field.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=18cm,clip]{14116fg02.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/09/aa14116-10/Timg57.png)

|

Figure 2:

INT R-band image of the cluster A2294 (north at the top

and east to the left). Circles and squares indicate cluster members

and non-members, respectively (see Table 1). Solid

circle in the center highlights the position of the BCG galaxy.

Annuli and box annuli show member and non-member emission line

galaxies, respectively. Labels indicate the IDs of cluster

galaxies cited in the text. A diamond at the right border of the

image highlights a QSO at |

| Open with DEXTER | |

We assigned magnitudes to all galaxies of our spectroscopic catalog.

Table 1 lists the velocity catalog (see also

Fig. 2): identification number of each galaxy, ID

(Col. 1); right ascension and declination, ![]() and

and ![]() (J2000, Col. 2); B and R magnitudes (Cols. 3 and 4); heliocentric

radial velocities,

(J2000, Col. 2); B and R magnitudes (Cols. 3 and 4); heliocentric

radial velocities,

![]() (Col. 5) with errors,

(Col. 5) with errors,

![]() (Col. 6); and emission lines detected in the spectra (Col. 7).

(Col. 6); and emission lines detected in the spectra (Col. 7).

The brightest galaxy of A2294 (ID. 46 in Table 1,

hereafter BCG) is probably the dominant galaxy, 1.6 R-magnitudes

more luminous than other cluster members. The measured redshift is

![]() ,

different from that reported by Crawford et al. (1995), z=0.178, using INT data and measured on the H

,

different from that reported by Crawford et al. (1995), z=0.178, using INT data and measured on the H![]() emission line only. This discrepancy prompted us to acquire additional

data for this galaxy. In August 2009, we acquired two 900 s

exposure long-slit spectra of the BCG. We used the LR-R grism,

covering the wavelength range

emission line only. This discrepancy prompted us to acquire additional

data for this galaxy. In August 2009, we acquired two 900 s

exposure long-slit spectra of the BCG. We used the LR-R grism,

covering the wavelength range ![]() 4500-10 000 Å. The target was

positioned in two slightly different positions along the slit to

perform an optimal sky subtraction with a technique commonly used to

reduce spectroscopic data in the near-infrared. Our reduced spectrum

(see Fig. 3) does not show any evidence of the H

4500-10 000 Å. The target was

positioned in two slightly different positions along the slit to

perform an optimal sky subtraction with a technique commonly used to

reduce spectroscopic data in the near-infrared. Our reduced spectrum

(see Fig. 3) does not show any evidence of the H![]() emission. We note that the H

emission. We note that the H![]() emission reported by Crawford et al. (1995) is very strong

emission reported by Crawford et al. (1995) is very strong

![]() (see

for comparison the spectrum of A291 having

(see

for comparison the spectrum of A291 having

![]() in their Fig. 1) and thus its presence would be just striking in

our spectrum. Indeed, we strongly suspect that their detection is

caused by some problem in data reduction, e.g., a cosmic ray or sky

subtraction, as also suggested by the incorrect measure of the galaxy redshift.

in their Fig. 1) and thus its presence would be just striking in

our spectrum. Indeed, we strongly suspect that their detection is

caused by some problem in data reduction, e.g., a cosmic ray or sky

subtraction, as also suggested by the incorrect measure of the galaxy redshift.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{14116fg03.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/09/aa14116-10/Timg63.png)

|

Figure 3:

Top panel: 2D spectrum of the BCG galaxy taken with the grism

LR-R mounted on DOLORES in the wavelength range |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Other cluster members are far less luminous than the BCG: the brightest ones lie in the central cluster region (IDs. 28, 39 and 18) with the exception of ID. 17 (hereafter R6) which lies in the northern region and is very radio luminous (>1024 W Hz-1, No. 6 of Rizza et al. 2003). Out of radio galaxies listed by Rizza et al. (2003), we also acquired a redshift for their No. 2 (ID. 47, labelled as R2 in Fig. 1), confirming its membership to the cluster.

3 Analysis of the spectroscopic sample

3.1 Member selection

To select cluster members among the 88 galaxies with redshifts, we

follow a two-step procedure. We first perform the 1D adaptive-kernel method (hereafter DEDICA, Pisani 1993, 1996; see also Fadda et al. 1996; Girardi et al. 1996). We search for significant peaks in the velocity distribution at >99% c.l. This procedure detects A2294 as a peak at

![]() populated by 80 galaxies considered as candidate cluster members (in the range

populated by 80 galaxies considered as candidate cluster members (in the range

![]() km s-1, see Fig. 4). Out of eight non-members, three and five are foreground and background galaxies, respectively.

km s-1, see Fig. 4). Out of eight non-members, three and five are foreground and background galaxies, respectively.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=7.5cm,clip]{14116fg04.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/09/aa14116-10/Timg66.png)

|

Figure 4: Redshift galaxy distribution. The solid line histogram refers to the 80 galaxies assigned to the A2294 complex according to the DEDICA reconstruction method. The number-galaxy density in the redshift space, as provided by the adaptive kernel reconstruction method is superimposed on the histogram. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

All the galaxies assigned to the cluster peak are analyzed in the

second step, which uses the combination of position and velocity

information, i.e., the ``shifting gapper'' method by Fadda et al. (1996).

This procedure rejects galaxies that are too far in velocity from the

main body of galaxies within a fixed bin that shifts along the distance

from the cluster center. The procedure is iterated until the number of

cluster members converges to a stable

value. Following Fadda et al. (1996), we use a gap of 1000 km s![]() - in the cluster rest-frame - and a bin of 0.6

h70-1 Mpc, or large

enough to include 15 galaxies. As for the center of A2294, we adopt the

position of the BCG [RA =

- in the cluster rest-frame - and a bin of 0.6

h70-1 Mpc, or large

enough to include 15 galaxies. As for the center of A2294, we adopt the

position of the BCG [RA =

![]() ,

Dec =

,

Dec =

![]() (J2000.0)], which is almost

coincident with the X-ray centroid obtained in this paper using Chandra

data (see Sect. 4). The ``shifting gapper'' procedure rejects

another two obvious interlopers very far from the main body (>2000 km s-1) but that survived the first step of our member selection procedure. We obtain a sample of 78 fiducial members (see

Fig. 5).

(J2000.0)], which is almost

coincident with the X-ray centroid obtained in this paper using Chandra

data (see Sect. 4). The ``shifting gapper'' procedure rejects

another two obvious interlopers very far from the main body (>2000 km s-1) but that survived the first step of our member selection procedure. We obtain a sample of 78 fiducial members (see

Fig. 5).

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=7.5cm,clip]{14116fg05.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/09/aa14116-10/Timg69.png)

|

Figure 5: The 78 galaxies assigned to the cluster. Upper panel: velocity distribution. The arrows indicate the velocities of the five brightest galaxies, in particular we indicate the brightest cluster galaxy ``BCG'', the bright radio galaxy ``R6''. Lower panel: stripe density plot where the arrows indicate the positions of the significant gaps. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

The five member galaxies exhibiting emission lines (ELGs) are

preferentially found in the external cluster regions (see

Fig. 2). The only ELG close to the cluster center

(ID. 24) lies in the high tail of the velocity distribution, far more

than cz=2500 km s![]() from the mean cluster velocity, as expected

e.g., in the case of a very radial orbit. These findings are in

general agreement with large statistical analyses of ELGs in

clusters (see Biviano et al. 1997, and refs. therein).

from the mean cluster velocity, as expected

e.g., in the case of a very radial orbit. These findings are in

general agreement with large statistical analyses of ELGs in

clusters (see Biviano et al. 1997, and refs. therein).

3.2 Global cluster properties

By applying the biweight estimator to the 78 cluster members (Beers et al. 1990, ROSTAT software), we compute a mean cluster redshift

of

![]() ,

i.e.

,

i.e.

![]() ) km s-1. We estimate the LOS

velocity dispersion,

) km s-1. We estimate the LOS

velocity dispersion,

![]() ,

by using the biweight estimator

and applying the cosmological correction and the standard correction

for velocity errors (Danese et al. 1980). We obtain

,

by using the biweight estimator

and applying the cosmological correction and the standard correction

for velocity errors (Danese et al. 1980). We obtain

![]() km s-1, where errors are estimated

through a bootstrap technique.

km s-1, where errors are estimated

through a bootstrap technique.

To evaluate the robustness of the

![]() estimate, we analyze

the velocity dispersion profile (Fig. 6). The integral

profile rises out to

estimate, we analyze

the velocity dispersion profile (Fig. 6). The integral

profile rises out to ![]() h70-1 Mpc

h70-1 Mpc![]() and then flattens suggesting

that a robust value of

and then flattens suggesting

that a robust value of

![]() is asymptotically reached in

the external cluster regions, as found for most nearby clusters (e.g.,

Fadda et al. 1996; Girardi et al. 1996).

is asymptotically reached in

the external cluster regions, as found for most nearby clusters (e.g.,

Fadda et al. 1996; Girardi et al. 1996).

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{14116fg06.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/09/aa14116-10/Timg75.png)

|

Figure 6:

Top panel: rest-frame velocity vs. projected distance from the

cluster center. Squares indicate the five brightest galaxies.

Middle and bottom panels: differential (big circles) and integral

(small points) profiles of mean velocity and LOS velocity

dispersion, respectively. For the differential profiles, we plot the

values for five annuli from the center of the cluster, each of 0.25

h70-1 Mpc |

| Open with DEXTER | |

In the framework of usual assumptions (cluster sphericity, dynamical

equilibrium, coincidence of the galaxy and mass distributions), one

can compute virial global quantities. Following the prescriptions of

Girardi & Mezzetti (2001), we assume for the radius of the

quasi-virialized region is

![]() h70-1 Mpc

h70-1 Mpc![]() from their Eq. (1) with the scaling of H(z)(see also Eq. 8 of Carlberg et al. 1997 for R200).

We compute the virial mass (Limber & Mathews 1960; see also,

e.g., Girardi et al. 1998)

from their Eq. (1) with the scaling of H(z)(see also Eq. 8 of Carlberg et al. 1997 for R200).

We compute the virial mass (Limber & Mathews 1960; see also,

e.g., Girardi et al. 1998)

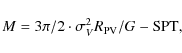

|

(1) |

where SPT is the surface pressure term correction (The & White 1986) and

The estimate of

![]() is robust when computed within a

large cluster region (see Fig. 6). The value of

is robust when computed within a

large cluster region (see Fig. 6). The value of

![]() depends on the size of the sampled region and possibly on the quality of the spatial sampling (e.g., whether the cluster is

uniformly sampled or not). Since in A2294 we sampled only a

fraction of

depends on the size of the sampled region and possibly on the quality of the spatial sampling (e.g., whether the cluster is

uniformly sampled or not). Since in A2294 we sampled only a

fraction of

![]() ,

we have to use an alternative

estimate of

,

we have to use an alternative

estimate of

![]() on the basis of the knowledge of the

galaxy distribution. Following Girardi et al. (1998; see also

Girardi & Mezzetti 2001), we assume a King-like distribution

with parameters typical of nearby/medium-redshift clusters: a core

radius

on the basis of the knowledge of the

galaxy distribution. Following Girardi et al. (1998; see also

Girardi & Mezzetti 2001), we assume a King-like distribution

with parameters typical of nearby/medium-redshift clusters: a core

radius

![]() and a

slope-parameter

and a

slope-parameter

![]() ,

i.e. the volume galaxy density

at large radii goes as

,

i.e. the volume galaxy density

at large radii goes as

![]() .

We obtain

.

We obtain

![]() (<

(<

![]() h70-1 Mpc, where a

h70-1 Mpc, where a ![]() error is

expected (Girardi et al. 1998, see also the approximation

given by their Eq. (13) when

error is

expected (Girardi et al. 1998, see also the approximation

given by their Eq. (13) when

![]() ). The value of SPT

depends strongly on the radial component of the velocity dispersion at the

radius of the sampled region and could be obtained by analyzing the

(differential) velocity dispersion profile, although this procedure

would require several hundreds of galaxies. We decide to assume a

). The value of SPT

depends strongly on the radial component of the velocity dispersion at the

radius of the sampled region and could be obtained by analyzing the

(differential) velocity dispersion profile, although this procedure

would require several hundreds of galaxies. We decide to assume a ![]() SPT correction as obtained in the literature by combining data on many

clusters sampled out to about

SPT correction as obtained in the literature by combining data on many

clusters sampled out to about

![]() (Carlberg et al. 1997; Girardi et al. 1998). We compute M(<

(Carlberg et al. 1997; Girardi et al. 1998). We compute M(<

![]()

![]() .

.

3.3 Velocity distribution

We analyze the velocity distribution to search for possible deviations from Gaussianity that might provide important signatures of complex dynamics. For the following tests, the null hypothesis is that the velocity distribution is a single Gaussian.

We estimate three shape estimators, i.e., the kurtosis, the skewness, and the scaled tail index (see, e.g., Bird & Beers 1993). We find no evidence that the velocity distribution departs from Gaussianity.

We then investigate the presence of gaps in the velocity distribution.

We follow the weighted gap analysis presented by Beers et al. (1991, 1992; ROSTAT software). We look for

normalized gaps larger than 2.25 since in random draws of a Gaussian

distribution they arise at most in about ![]() of the cases,

independent of the sample size (Wainer & Schacht 1978). We

detect two significant gaps (at the

of the cases,

independent of the sample size (Wainer & Schacht 1978). We

detect two significant gaps (at the ![]() and

and ![]() c.l.s), which

divide the cluster into three groups of 28, 14, and 36 galaxies from

low to high velocities (hereafter GV1, GV2, and GV3, see

Fig. 5). The BCG is assigned to the GV2 peak. Among

other luminous galaxies, three galaxies (R6, ID. 28, and ID. 39)

are assigned to the GV1 peak and one galaxy (ID. 18) is assigned to

the GV3 peak.

c.l.s), which

divide the cluster into three groups of 28, 14, and 36 galaxies from

low to high velocities (hereafter GV1, GV2, and GV3, see

Fig. 5). The BCG is assigned to the GV2 peak. Among

other luminous galaxies, three galaxies (R6, ID. 28, and ID. 39)

are assigned to the GV1 peak and one galaxy (ID. 18) is assigned to

the GV3 peak.

Following Ashman et al. (1994), we also apply the Kaye's mixture model (KMM) algorithm. This test does not find a three-groups partition, which provides a significantly more accurate description of the velocity distribution than a single Gaussian.

3.4 3D-analysis

The existence of correlations between positions and velocities of cluster galaxies is a characteristic of true substructures. Here we use three different approaches to analyze the structure of A2294 combining position and velocity information.

To search for a possible physical meaning of the three subclusters

determined by the two weighted gaps, we compare two by two the spatial

galaxy distributions of GV1, GV2, and GV3. We find that the GV1 and

GV3 groups differ in the distributions of the

clustercentric distances of member galaxies at the ![]() c.l.

(according to the the 1D Kolmogorov-Smirnov test; hereafter

1DKS-test, see e.g., Press et al. 1992). The GV1 galaxies

are, on average, closer to the cluster center than the GV3 galaxies

(see Fig. 7).

c.l.

(according to the the 1D Kolmogorov-Smirnov test; hereafter

1DKS-test, see e.g., Press et al. 1992). The GV1 galaxies

are, on average, closer to the cluster center than the GV3 galaxies

(see Fig. 7).

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{14116fg07.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/09/aa14116-10/Timg92.png)

|

Figure 7: Spatial distribution on the sky of the cluster galaxies showing the three groups recovered by the weighted gap analysis. Solid circles, crosses, and open circles indicate the galaxies of GV1, GV2, and GV3, respectively. The BCG is taken as the cluster center. Large squares indicate the five brightest cluster members. Among them, the BCG and R6 are indicated by the two largest squares. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

We analyze the presence of a velocity gradient performing a multiple

linear regression fit to the observed velocities with respect to the

galaxy positions in the plane of the sky (e.g., Boschin et al. 2004, and refs. therein). We find a position angle on the celestial sphere of

![]() degrees (measured

counter-clock wise from north), i.e. higher-velocity galaxies lie

in the SSW region of the cluster. To assess the significance of this

velocity gradient, we perform 1000 Monte Carlo simulations by randomly

shuffling the galaxy velocities and for each simulation we determine

the coefficient of multiple determination (RC2, see e.g., NAG

Fortran Workstation Handbook 1986). We define the

significance of the velocity gradient as the fraction of times in

which the RC2 of the simulated data is smaller than the observed

RC2. We find that the velocity gradient is marginally significant

at the

degrees (measured

counter-clock wise from north), i.e. higher-velocity galaxies lie

in the SSW region of the cluster. To assess the significance of this

velocity gradient, we perform 1000 Monte Carlo simulations by randomly

shuffling the galaxy velocities and for each simulation we determine

the coefficient of multiple determination (RC2, see e.g., NAG

Fortran Workstation Handbook 1986). We define the

significance of the velocity gradient as the fraction of times in

which the RC2 of the simulated data is smaller than the observed

RC2. We find that the velocity gradient is marginally significant

at the ![]() c.l.

c.l.

We also combine galaxy velocity and position information to compute

the ![]() -statistics devised by Dressler & Schectman

(1988; see also e.g., Boschin et al. 2006, for a recent

application). We find no significant indication of substructure.

-statistics devised by Dressler & Schectman

(1988; see also e.g., Boschin et al. 2006, for a recent

application). We find no significant indication of substructure.

3.5 Kinematics of more luminous galaxies

The presence of velocity segregation of galaxies with respect to their colors, luminosities, and morphologies is often taken as evidence of advanced dynamical evolution of the parent cluster (e.g. Biviano et al. 1992; Fusco-Femiano & Menci 1998). Here we check for possible luminosity segregation of galaxies in the velocity space.

We find no significant correlation between the absolute velocity |v| and R-magnitude. We also divide the sample into a low and a high-luminosity subsamples by using the median R-magnitude =18.145. The two subsamples do not differ in their velocity distribution as we verify with the standard means-test and F-test (e.g., Press et al. 1992) applied to the means and variances of velocities and with the 1DKS-test applied to the whole velocity distributions. This agrees with the very small range of action of velocity segregation in galaxy clusters, i.e. typically only the three most luminous galaxies (Biviano et al. 1992; see also Goto 2005).

Examining the velocity distributions of the two subsamples in more

detail, we find that the distribution of luminous galaxies is found to

be non-Gaussian according to the scale tail index (at the ![]() c.l.) and that, according to the 1D-DEDICA technique, it is more

accurately described by a bimodal distribution (see

Fig. 8). The two peaks of this distribution, of 20

and 19 galaxies at

c.l.) and that, according to the 1D-DEDICA technique, it is more

accurately described by a bimodal distribution (see

Fig. 8). The two peaks of this distribution, of 20

and 19 galaxies at ![]() 49 700 and 51 950 km s

49 700 and 51 950 km s![]() respectively, are

separated by

respectively, are

separated by ![]() 2000 km s

2000 km s![]() in the rest cluster frame and appear

to overlap, i.e. 15 galaxies have a non-null probability of

belonging to both the peaks. The BCG is assigned to the low-velocity

peak, but has a high probability of belonging to the other peak. Among

other luminous galaxies, R6, IDs. 28 and 39 are assigned to the

low-velocity peak and ID. 18 to the high-velocity peak.

in the rest cluster frame and appear

to overlap, i.e. 15 galaxies have a non-null probability of

belonging to both the peaks. The BCG is assigned to the low-velocity

peak, but has a high probability of belonging to the other peak. Among

other luminous galaxies, R6, IDs. 28 and 39 are assigned to the

low-velocity peak and ID. 18 to the high-velocity peak.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{14116fg08.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/09/aa14116-10/Timg97.png)

|

Figure 8: Velocity galaxy distribution of more and less luminous cluster members (solid and dashed lines, respectively). The arrows indicate the velocities of the five brightest galaxies, in particular ``BCG'' indicates the bright, central galaxy and ``R6'' indicates the bright radio-galaxy. The number-galaxy densities, as provided by the adaptive kernel reconstruction method are superimposed on the histograms. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

According to the DEDICA assignment, we estimate

![]() and

and ![]() 640 km s

640 km s![]() for the low and high-velocity groups,

respectively. However, since there is a wide velocity-range where

galaxies have a non-zero probability of belonging to both the clumps,

DEDICA membership assignment leads to an artificial truncation of the

tails of the distributions. This truncation may lead to an

underestimate of velocity dispersion for the subclusters. Thus, we

prefer to rely on the estimates obtained through the KMM approach even

if the tightest bimodal fit does not represent a significant

improvement on that of the single Gaussian according to the likelihood

ratio test. The low- and high-velocity groups given by the best KMM

bimodal fit have mean velocities

for the low and high-velocity groups,

respectively. However, since there is a wide velocity-range where

galaxies have a non-zero probability of belonging to both the clumps,

DEDICA membership assignment leads to an artificial truncation of the

tails of the distributions. This truncation may lead to an

underestimate of velocity dispersion for the subclusters. Thus, we

prefer to rely on the estimates obtained through the KMM approach even

if the tightest bimodal fit does not represent a significant

improvement on that of the single Gaussian according to the likelihood

ratio test. The low- and high-velocity groups given by the best KMM

bimodal fit have mean velocities

![]() and

52 230 km s-1, in good agreement with the peak velocities reported above

and

and

52 230 km s-1, in good agreement with the peak velocities reported above

and

![]() and

and ![]() 670 km s-1.

670 km s-1.

3.6 Analysis of the photometric sample

By applying the 2D adaptive-kernel method to the positions of A2294

galaxy members, we identify only one significant peak. However, our

spectroscopic data do not cover the entire cluster field and are affected

by magnitude incompleteness. To overcome these problems, from our

photometric catalog we select likely members on the basis of the

color-magnitude relation (hereafter CMR), which indicates the

early-type galaxy locus. To determine the CMR, we fix the slope

according to López-Cruz et al. (2004, see their Fig. 3) and

apply the two-sigma-clipping fitting procedure to the cluster

members obtaining B-

![]() (see Fig. 9).

From our photometric catalog, we consider as likely cluster members

those objects with a SExtractor stellar index

(see Fig. 9).

From our photometric catalog, we consider as likely cluster members

those objects with a SExtractor stellar index ![]() 0.9 lying within

0.25 mag of the CMR. To avoid contamination by field galaxies, we do

not show results for galaxies fainter than 21 mag (in R-band).

Figure 10 shows the contour map for the likely cluster

members with

0.9 lying within

0.25 mag of the CMR. To avoid contamination by field galaxies, we do

not show results for galaxies fainter than 21 mag (in R-band).

Figure 10 shows the contour map for the likely cluster

members with ![]() :

we find again that A2294 is well described

by only one peak centered on the BCG galaxy.

:

we find again that A2294 is well described

by only one peak centered on the BCG galaxy.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{14116fg09.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/09/aa14116-10/Timg103.png)

|

Figure 9:

B-R vs. R diagram for galaxies with available spectroscopy is shown

by circles and crosses (cluster and field members, respectively).

The solid line gives the best-fit color-magnitude relation as

determined for member galaxies; the dashed lines are drawn at |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{14116fg10.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/09/aa14116-10/Timg104.png)

|

Figure 10:

Spatial distribution on the sky and relative isodensity contour map

of likely cluster members extracted from our photometric catalog

with |

| Open with DEXTER | |

4 X-ray analysis

The X-ray analysis of A2294 is performed on the archival data of the

Chandra ACIS-I observation 800 246 (exposure ID #3246). The pointing

has an exposure time of 10 ks. Data reduction is performed using the

package CIAO![]() (Chandra Interactive Analysis of

Observations, ver. 3.3 with CALDB ver. 3.2.1) on chips I0, I1,

I2, and I3 (field of view

(Chandra Interactive Analysis of

Observations, ver. 3.3 with CALDB ver. 3.2.1) on chips I0, I1,

I2, and I3 (field of view ![]()

![]() ). First, we

remove events from the level 2 event list with a status not equal to

zero and with grades one, five, and seven. Then, we select all events

with energy between 0.3 and 10 keV. In addition, we clean bad offsets

and examine the data, filtering out bad columns and removing times

when the count rate exceeds three standard deviations from the mean

count rate per 3.3 s interval. We then clean the four chips for

flickering pixels, i.e., times where a pixel has events in two

sequential 3.3 s intervals. The resulting exposure time for the

reduced data is 9.9 ks.

). First, we

remove events from the level 2 event list with a status not equal to

zero and with grades one, five, and seven. Then, we select all events

with energy between 0.3 and 10 keV. In addition, we clean bad offsets

and examine the data, filtering out bad columns and removing times

when the count rate exceeds three standard deviations from the mean

count rate per 3.3 s interval. We then clean the four chips for

flickering pixels, i.e., times where a pixel has events in two

sequential 3.3 s intervals. The resulting exposure time for the

reduced data is 9.9 ks.

A quick look at the reduced image is sufficient to reveal the regular

morphology of the extended X-ray emission of this cluster (see

Fig. 11). The low values of the

![]() power ratios

found by Bauer et al. (2005) quantitatively support this

feeling. The absence of multiple clumps in the ICM is confirmed by

performing a wavelet multiscale analysis on the chip I3: the task

CIAO/Wavdetect identifies A2294 as a single extended X-ray source.

power ratios

found by Bauer et al. (2005) quantitatively support this

feeling. The absence of multiple clumps in the ICM is confirmed by

performing a wavelet multiscale analysis on the chip I3: the task

CIAO/Wavdetect identifies A2294 as a single extended X-ray source.

To more accurately characterize the X-ray morphology of the cluster, by using

the CIAO package Sherpa we fit a simple Beta model to the 2D X-ray

photon distribution on the chip I3. The model is defined

to be (Cavaliere & Fusco-Femiano 1976)

![\begin{displaymath}S(R)=S_0[1+(R/R_{\rm c})^2]^{\alpha}+b,

\end{displaymath}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/09/aa14116-10/img107.png)

|

(2) |

where

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{14116fg11.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/09/aa14116-10/Timg117.png)

|

Figure 11:

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

The above model provides an adequate description fit to the data (the reduced CSTAT statistic is 1.04; Cash 1979). However, we check for possible departures of the X-ray surface brightness, and thus of the gas density distribution, from the Beta model fit by investigating the Beta model residuals. The residuals show a deficit of X-ray emitting gas in a region extending along the NE-SW direction, with a negative peak in the very central cluster region (see Fig. 12). Around the cluster center, elongated in the direction SE-NW, there are also regions that have an excess of positive residuals.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{14116fg12.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/09/aa14116-10/Timg118.png)

|

Figure 12: The smoothed X-ray emission in the right-upper quadrant of Fig. 11 with, superimposed, the contour levels of the positive (black) and negative (white) smoothed Beta model residuals (North at the top and East to the left). |

| Open with DEXTER | |

As for the spectral properties of the cluster X-ray photons, we

compute a global estimate of the ICM temperature. The temperature is

computed from the X-ray spectrum of the cluster within a circular

aperture of ![]() 173

173

![]() radius (0.5

h70-1 Mpc

radius (0.5

h70-1 Mpc![]() at the cluster redshift)

around the centroid of the X-ray emission. Fixing the absorbing

galactic hydrogen column density at

at the cluster redshift)

around the centroid of the X-ray emission. Fixing the absorbing

galactic hydrogen column density at

![]() cm-2,

computed from the HI maps by Dickey & Lockman (1990), we fit

a Raymond-Smith (1977) spectrum using the CIAO package Sherpa

with a

cm-2,

computed from the HI maps by Dickey & Lockman (1990), we fit

a Raymond-Smith (1977) spectrum using the CIAO package Sherpa

with a ![]() statistics and assuming a metal abundance of 0.3 in

solar units. We find a best-fit temperature of

statistics and assuming a metal abundance of 0.3 in

solar units. We find a best-fit temperature of

![]() keV.

keV.

A detailed temperature and metallicity map would be highly desirable

to more accurately describe the properties of the ICM, but due to the

relatively low exposure times, the photon statistics are insufficient

for this aim. However, in a low signal-to-noise situation, possible

temperature gradients in the ICM might be detected using the

``hardness'' (or ``softness'') map of the cluster. We

create two images in the energy bands 0.5-2 keV (soft band) and

2-7 keV (hard band), subtracting a constant background level in

each energy band. Computing counts in the soft (S) and in the hard (H) band, we define the quantity ``softness ratio'' as

SR=(S-H)/(S+H). Both images are exposure-corrected with their

corresponding exposure maps. Because of the low number of photons

available, we have to choose a large pixel size to obtain a high

quality count statistic per pixel, so the resolution of the soft and

hard images is low (182 kpc pix-1). A 3D graph of the SR values

in the pixels within a radius of 0.5

h70-1 Mpc![]() from the cluster center is

reported in Fig. 13. Typical errors are

from the cluster center is

reported in Fig. 13. Typical errors are ![]() ,

while

the median value of SR is 0.25. According to the PIMMS tool, this

value corresponds to a temperature of

,

while

the median value of SR is 0.25. According to the PIMMS tool, this

value corresponds to a temperature of ![]() 9.7 keV, in good

agreement with the global temperature reported above. The SR 3D

graph does not show any evidence of significant temperature gradients.

9.7 keV, in good

agreement with the global temperature reported above. The SR 3D

graph does not show any evidence of significant temperature gradients.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{14116fg13.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/09/aa14116-10/Timg123.png)

|

Figure 13: Softness ratio 3D map of A2294 around the centroid of the X-ray distribution. The plane at the median SR value (0.25) is drawn. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

5 Discussion and conclusions

Our estimate of the cluster redshift is

![]() 0.0005 and the BCG is well at rest within the cluster (cf. our

z=0.1690 with z=0.178 by Crawford et al. 1995).

0.0005 and the BCG is well at rest within the cluster (cf. our

z=0.1690 with z=0.178 by Crawford et al. 1995).

For the first time, the internal dynamics of A2294 have been analyzed.

The high values of the velocity dispersion

![]() km s

km s![]() and X-ray temperature

and X-ray temperature

![]() keV are comparable to the highest values found in

typical clusters (see Mushotzky & Scharf 1997; Girardi &

Mezzetti 2001; Leccardi & Molendi 2008). Our

estimates of

keV are comparable to the highest values found in

typical clusters (see Mushotzky & Scharf 1997; Girardi &

Mezzetti 2001; Leccardi & Molendi 2008). Our

estimates of

![]() and

and ![]() are fully consistent

when assuming the equipartition of energy density between ICM and

galaxies. We obtain

are fully consistent

when assuming the equipartition of energy density between ICM and

galaxies. We obtain

![]() to be

compared with

to be

compared with

![]() ,

where

,

where

![]() with

with ![]() the mean

molecular weight and

the mean

molecular weight and ![]() the proton mass (see also

Fig. 6). Taking this result at face value one might think

that A2294 is not far from dynamical equilibrium and the virial mass

estimate M(<

the proton mass (see also

Fig. 6). Taking this result at face value one might think

that A2294 is not far from dynamical equilibrium and the virial mass

estimate M(<

![]()

![]() 4

4

![]() computed in

Sect. 3.2 to be quite reliable.

computed in

Sect. 3.2 to be quite reliable.

5.1 Internal structure

However, our analysis indicates that this cluster is not so relaxed as one may interpret at first glance. Evidence of this comes from both optical and X-ray analyses.

First of all, both the integral and differential velocity dispersion

profiles rise in the central region out to ![]() 0.2

h70-1 Mpc

0.2

h70-1 Mpc![]() (Fig. 6, middle and bottom panels). As for the velocity dispersion, this behavior might be a signature of a relaxed cluster

exhibiting circular velocities and galaxy merger phenomena in the central

cluster region (e.g., Merritt 1988; Menci & Fusco Femiano 1996; Girardi et al. 1998).

Alternatively, it might be the signature of subclumps of different mean

velocities (see, e.g., Abell 3391-3395 in Girardi et al. 1996; Abell 115 in Barrena et al. 2007b). The latter hypothesis is supported by the behavior of the mean velocity

profile and by the plot of velocity versus projected clustercentric

distance, where the central region is more populated by low velocity

galaxies than high velocity galaxies. This suggests the presence of

substructure in the cluster core.

(Fig. 6, middle and bottom panels). As for the velocity dispersion, this behavior might be a signature of a relaxed cluster

exhibiting circular velocities and galaxy merger phenomena in the central

cluster region (e.g., Merritt 1988; Menci & Fusco Femiano 1996; Girardi et al. 1998).

Alternatively, it might be the signature of subclumps of different mean

velocities (see, e.g., Abell 3391-3395 in Girardi et al. 1996; Abell 115 in Barrena et al. 2007b). The latter hypothesis is supported by the behavior of the mean velocity

profile and by the plot of velocity versus projected clustercentric

distance, where the central region is more populated by low velocity

galaxies than high velocity galaxies. This suggests the presence of

substructure in the cluster core.

Second, the two gaps found in the velocity distribution indicate that there are three subclumps with the BCG in the middle velocity subclump. Although the presence of the three groups (GV1, GV2, GV3) is not very strongly significant on the basis of only velocity data, the existence of a spatial segregation between GV1 and GV3 groups is a indicator of true substructures. We also find a (marginally significant) velocity gradient toward the SSW direction.

Third, the high-luminosity galaxy subsample shows two peaks (largely

overlapping) in the velocity distribution, with the BCG being

somewhere in-between. This result is very interesting, implying that

galaxies of different luminosity may trace the dynamics of cluster

mergers in a different way. A noticeable example was reported by

Biviano et al. (1996): they found that the two central

dominant galaxies of the Coma cluster are surrounded by luminous

galaxies, accompanied by the two main X-ray peaks, while the

distribution of faint galaxies does not appear to be centered on one

of the two dominant galaxies, but is rather coincident with a

secondary peak detected in the X-ray image. Biviano et al. speculate that

the merging of Coma is in an advanced phase, where faint galaxies

trace the forming structure of the cluster, while the most luminous

galaxies still trace the remnant of the core-halo structure of a

pre-merging clump, which may be sufficiently dense to survive for a

long time after the merging (as suggested by numerical simulations,

e.g. González-Casado et al. 1994). In A2294, luminous

galaxies may trace the remnants of two merging subclusters

characterized by an impact velocity ![]() 2000 km s-1. Assuming the

dynamical equilibrium for each of the two individual subclusters, from

the values of

2000 km s-1. Assuming the

dynamical equilibrium for each of the two individual subclusters, from

the values of

![]() of the two subclusters we obtain a

virial mass of 1.8

of the two subclusters we obtain a

virial mass of 1.8

![]() and 0.5

and 0.5

![]() for the low and high velocity

subclusters. The total mass

for the low and high velocity

subclusters. The total mass

![]()

![]() is lower than the

global virial value computed in Sect. 3.2, but is still a high value.

is lower than the

global virial value computed in Sect. 3.2, but is still a high value.

As for the X-ray data, we find no evidence of obvious substructure. Our multiscale wavelet analysis of the Chandra image does not identify any subclumps in the X-ray photon distribution. We also confirm the absence of a significant, macroscopic cluster ellipticity (see also Hashimoto et al. 2007; Maughan et al. 2008).

As for the Beta model we fit, the value of the core radius

![]() h70-1 kpc

h70-1 kpc ![]() and the value of the slope parameter

and the value of the slope parameter

![]() agree well with those computed by

Hart in his PhD thesis (2008;

agree well with those computed by

Hart in his PhD thesis (2008;

![]() h70-1 kpc;

h70-1 kpc;

![]() ). The value of the core radius

agrees with that expected from the relation between surface brightness

concentration index and core radius shown by Hashimoto et al. (2007, see their Fig. 8 and the value of concentration in

their Table 2). The values of

). The value of the core radius

agrees with that expected from the relation between surface brightness

concentration index and core radius shown by Hashimoto et al. (2007, see their Fig. 8 and the value of concentration in

their Table 2). The values of ![]() and

and

![]() lie on the low end of the parabolic relation found between these two

parameters (Neumann & Arnaud 1999). On the other hand, the

value of

lie on the low end of the parabolic relation found between these two

parameters (Neumann & Arnaud 1999). On the other hand, the

value of

![]() might be somewhat small

compared to the typical values for very rich/hot clusters (e.g., Jones

& Forman 1999; Vikhlinin et al. 1999). However, we

note that most of our signal comes from the region with a radius of

might be somewhat small

compared to the typical values for very rich/hot clusters (e.g., Jones

& Forman 1999; Vikhlinin et al. 1999). However, we

note that most of our signal comes from the region with a radius of

![]() 0.5

h70-1 Mpc

0.5

h70-1 Mpc![]() (

(![]()

![]() )

and that there are

indications of a continuous steepening of the X-ray brightness

profiles with increasing radius (e.g., Vikhlinin et al. 1999;

Neumann 2005). This steepening is the most likely cause of

offsets between different cluster samples (see Vikhlinin et al. 1999 where

)

and that there are

indications of a continuous steepening of the X-ray brightness

profiles with increasing radius (e.g., Vikhlinin et al. 1999;

Neumann 2005). This steepening is the most likely cause of

offsets between different cluster samples (see Vikhlinin et al. 1999 where

![]() vs. Jones & Forman 1999 where

vs. Jones & Forman 1999 where

![]() )

and

of apparent discrepancies between fit parameters obtained for the same

clusters (e.g. Buote et al. 2005). Indeed, the most

appropriate way to compare different clusters it seems is to consider the

measure of the local slope of the surface brightness at a certain,

rescaled radius (see Croston et al. 2008 for variation of

this parameter with radius). As for A2294, Maughan et

al. (2008) computed the slope

)

and

of apparent discrepancies between fit parameters obtained for the same

clusters (e.g. Buote et al. 2005). Indeed, the most

appropriate way to compare different clusters it seems is to consider the

measure of the local slope of the surface brightness at a certain,

rescaled radius (see Croston et al. 2008 for variation of

this parameter with radius). As for A2294, Maughan et

al. (2008) computed the slope

![]() at a radius of

R500=1.3

h70-1 Mpc,

using the data in the radial range 0.7R500-1.3R500,

i.e. well outside the region we analyze. This value is in agreement

with that expected for very hot clusters at z<0.5 (see their

Fig. 11). Finally, we note that, in the case of a cluster merger,

numerical simulations predict a clear expansion of the gas core and

a steepening of the slope (Roettiger et al. 1996, see their

Fig. 3). This agrees with the results of Jones & Forman (1999) to explain the large core radii found for a few observed clusters, but we refer to Neumann & Arnaud (1999) for no

link between

at a radius of

R500=1.3

h70-1 Mpc,

using the data in the radial range 0.7R500-1.3R500,

i.e. well outside the region we analyze. This value is in agreement

with that expected for very hot clusters at z<0.5 (see their

Fig. 11). Finally, we note that, in the case of a cluster merger,

numerical simulations predict a clear expansion of the gas core and

a steepening of the slope (Roettiger et al. 1996, see their

Fig. 3). This agrees with the results of Jones & Forman (1999) to explain the large core radii found for a few observed clusters, but we refer to Neumann & Arnaud (1999) for no

link between

![]() value and cluster dynamical

status. To summarize, our small values of

value and cluster dynamical

status. To summarize, our small values of ![]() and

and

![]() are not indicative of substructure. Direct

evidence of cluster substructure comes from the 2D image of the Beta

model residuals, which shows positive residuals in the X-ray

emission along the SE-NW direction (see Fig. 12).

are not indicative of substructure. Direct

evidence of cluster substructure comes from the 2D image of the Beta

model residuals, which shows positive residuals in the X-ray

emission along the SE-NW direction (see Fig. 12).

To interpret the residual image, we simulate two systems, both having

an X-ray surface brightness profile following a Beta model with the

same

![]() ,

but different

,

but different ![]() and S0, with

the centers separated by a distance of the order of the two adopted

core radii. The surface brightness profile of the composed system has

a single peak, as in the case of A2294 (see Fig. 14,

upper panel). The fit with a single Beta model provides a value for

and S0, with

the centers separated by a distance of the order of the two adopted

core radii. The surface brightness profile of the composed system has

a single peak, as in the case of A2294 (see Fig. 14,

upper panel). The fit with a single Beta model provides a value for

![]() and

and ![]()

![]() larger than the two adopted core

radii, respectively. Instead,

larger than the two adopted core

radii, respectively. Instead,

![]() is

is ![]()

![]() larger than the adopted value. The appearance of the 2D image of the

residuals (Fig. 14, lower panel) is roughly similar to

that obtained for A2294, with a two-clump surplus of X-ray photons

(with the left clump being the most evident) in the line defined by

the centers of the subsystems and a deficit in the perpendicular

direction (cf. Fig. 14 with Fig. 12). Thus

the residual image of A2294 data might be explained by two very close

(or very closely projected) systems along the SE-NW direction. In

particular, we find that an asymmetry between the two components might

explain the more prominent excess of the SE structure in the residual

image. Some pieces of observational evidence found in the literature,

i.e. the presence of a centroid shift (Rizza et al. 1998;

Maughan et al. 2008, but see Hashimoto et al. 2007) or

a certain degree of asymmetry of the X-ray profile around the centroid

of the photon distribution (Hashimoto et al. 2007) are

likely to be connected with the substructure we detect. Our above

bimodal model is obviously a very simplified scenario in the case of a

close interaction between two galaxy systems - as we discuss below

- and we do not attempt to go further in interpreting the observed

data, e.g., exploring in more detail the quantitative parameters.

larger than the adopted value. The appearance of the 2D image of the

residuals (Fig. 14, lower panel) is roughly similar to

that obtained for A2294, with a two-clump surplus of X-ray photons

(with the left clump being the most evident) in the line defined by

the centers of the subsystems and a deficit in the perpendicular

direction (cf. Fig. 14 with Fig. 12). Thus

the residual image of A2294 data might be explained by two very close

(or very closely projected) systems along the SE-NW direction. In

particular, we find that an asymmetry between the two components might

explain the more prominent excess of the SE structure in the residual

image. Some pieces of observational evidence found in the literature,

i.e. the presence of a centroid shift (Rizza et al. 1998;

Maughan et al. 2008, but see Hashimoto et al. 2007) or

a certain degree of asymmetry of the X-ray profile around the centroid

of the photon distribution (Hashimoto et al. 2007) are

likely to be connected with the substructure we detect. Our above

bimodal model is obviously a very simplified scenario in the case of a

close interaction between two galaxy systems - as we discuss below

- and we do not attempt to go further in interpreting the observed

data, e.g., exploring in more detail the quantitative parameters.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{14116fg14.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/09/aa14116-10/Timg145.png)

|

Figure 14: Upper panel: integrated X-ray profile of the simulated system composed of two subsystems, both following a Beta model profile but with different model parameters (see text). Lower panel: surface brightness distribution of the simulated system with, superimposed, the contour levels of the Beta model residuals. White (dark/gray) contours represent negative (positive) residuals. As a reference, the size of the fitted core radius is drawn. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

5.2 Investigating the likely merger cluster

The absence of a macroscopic elongation of the galaxy and ICM distributions and the poor significance of the velocity gradient suggests that the evidence of substructure we detect is a trace of minor/old accretion phenomena or that the direction of the cluster merger is aligned along the LOS. The LOS direction might explain the difficulty of the analysis of the cluster internal dynamics. Another example of a cluster merger along the LOS is the galaxy cluster CL 0024+17, an apparently relaxed system, which is actually a collision between two clusters, the interaction occurring along our LOS, as demonstrated by Czoske et al. (2002) using about 300 galaxies with redshifts in the cluster field.

The cluster merger scenario is generally consistent with the absence

of the cool core. Although simulations yield ambivalent results about

the role of mergers in destroying cool cores (Poole et al. 2006; Burns et al. 2008), observations seem to favor cool core destruction by means of cluster mergers (Allen et al. 2001; Sanderson et al. 2006). In particular, the

LOS merging direction might explain the high compactness of A2294 with

respect to other non-cool core clusters (Bauer et al. 2005,

see their Fig. 3). We note that our new data for the BCG exclude the

presence of H![]() emission, which had been previously reported by

Crawford et al. (1995), thus reclassifying A2294 as a quite

``normal'' non-cool core.

emission, which had been previously reported by

Crawford et al. (1995), thus reclassifying A2294 as a quite

``normal'' non-cool core.

In the framework of a cluster merger where the two subclusters are

well traced by the luminous galaxies (for the non-collisional part,

i.e., dark matter and galaxies) and the residual image (for the

collisional part, i.e., the gas), we may also obtain some information

about the evolutionary stage of the merger. Assuming that

![]() for each of the two subclusters, from the values of

for each of the two subclusters, from the values of

![]() we obtain the X-ray temperatures

we obtain the X-ray temperatures

![]() and

2.8 keV. The observed X-ray temperature is thus

and

2.8 keV. The observed X-ray temperature is thus ![]() 1.4 times

that of the main subcluster. While the observed X-ray temperature of