| Issue |

A&A

Volume 515, June 2010

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A93 | |

| Number of page(s) | 11 | |

| Section | Stellar atmospheres | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/200913897 | |

| Published online | 15 June 2010 | |

Behavior of Li abundances in solar-analog stars![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

II. Evidence of the connection with rotation and stellar activity

Y. Takeda1 - S. Honda2 - S. Kawanomoto1 - H. Ando1 - T. Sakurai1

1 - National Astronomical Observatory of Japan, 2-21-1 Osawa, Mitaka, Tokyo 181-8588, Japan

2 - Gunma Astronomical Observatory, 6860-86 Nakayama, Takayama-Mura, Agatsuma-gun, Gunma 377-0702, Japan

Received 18 December 2009 / Accepted 2 February 2010

Abstract

Context. We previously attempted to ascertain why the Li I 6708

line-strengths of Sun-like stars differ so significantly despite the

superficial similarities of stellar parameters. We carried out a

comprehensive analysis of 118 solar analogs and reported that a

close connection exists between the Li abundance (

![]() )

and the line-broadening width (

)

and the line-broadening width (

![]() ;

mainly contributed by rotational effect), which led us to conclude that

stellar rotation may be the primary control of the surface

Li content.

;

mainly contributed by rotational effect), which led us to conclude that

stellar rotation may be the primary control of the surface

Li content.

Aims. To examine our claim in more detail, we study whether the

degree of stellar activity exhibits a similar correlation with the

Li abundance, which is expected because of the widely believed

close connection between rotation and activity.

Methods. We measured the residual flux at the line center of the strong Ca II 8542 line,

r0(8542), known to be a useful index of stellar

activity, for all sample stars using newly acquired spectra in this

near-IR region. The projected rotational velocity (

![]() )

was estimated by subtracting the macroturbulence contribution from

)

was estimated by subtracting the macroturbulence contribution from

![]() that we had already established.

that we had already established.

Results. A remarkable (positive) correlation was found in the

![]() versus (vs.)

r0(8542) diagram as well as in both the

r0(8542) vs.

versus (vs.)

r0(8542) diagram as well as in both the

r0(8542) vs.

![]() and

and

![]() vs.

vs.

![]() diagrams,

as had been expected. With the confirmation of rotation-dependent

stellar activity, this clearly shows that the surface

Li abundances of these solar analogs progressively decrease as the

rotation rate decreases.

diagrams,

as had been expected. With the confirmation of rotation-dependent

stellar activity, this clearly shows that the surface

Li abundances of these solar analogs progressively decrease as the

rotation rate decreases.

Conclusions. Given this observational evidence, we conclude that

the depletion of surface Li in solar-type stars, probably caused

by effective envelope mixing, operates more efficiently as stellar

rotation decelerates. It may be promising to attribute the

low-Li tendency of planet-host G dwarfs to their different

nature in the stellar angular momentum.

Key words: stars: abundances - stars: activity - stars: atmospheres - stars: solar-type - stars: rotation

1 Introduction

Since Li nuclei are burned and destroyed on their arrival at the hot

stellar interior (

![]() K), we can gain valuable

information from the surface Li composition of a star about the past

history and the physical mechanism of stellar envelope mixing.

It has been known, however, that Li abundances (

K), we can gain valuable

information from the surface Li composition of a star about the past

history and the physical mechanism of stellar envelope mixing.

It has been known, however, that Li abundances (

![]() )

in

Sun-like stars exhibits puzzling behaviors:

)

in

Sun-like stars exhibits puzzling behaviors:

- a markedly large diversity (by more than

2 dex) of

2 dex) of

is seen despite the similarity of stellar parameters;

is seen despite the similarity of stellar parameters;

- planet-host stars tend to show appreciably lower

than non-planet-host stars (cf. Israelian et al. 2004, 2009).

than non-planet-host stars (cf. Israelian et al. 2004, 2009).

To elucidate this problem, Takeda et al. (2007,

hereinafter referred to as Paper I) conducted an extensive

high-precision study of stellar parameters as well as of

![]() for 118 solar analogs and found that

for 118 solar analogs and found that

![]() values,

exhibiting a large dispersion themselves, are closely correlated

with the line-width, which is characterized by the macroscopic velocity

dispersion (

values,

exhibiting a large dispersion themselves, are closely correlated

with the line-width, which is characterized by the macroscopic velocity

dispersion (

![]() )

including the rotational as well as the

macroturbulent broadening effect.

)

including the rotational as well as the

macroturbulent broadening effect.

We then speculated that ![]() (equatorial rotation velocity)

would be the most important factor affecting

(equatorial rotation velocity)

would be the most important factor affecting

![]() ,

since the star-to-star variation in

,

since the star-to-star variation in

![]() may be responsible for the spread in

may be responsible for the spread in

![]() ,

any

considerable fluctuation in the macroturbulent velocity

field among similar solar-type stars being difficult to imagine.

,

any

considerable fluctuation in the macroturbulent velocity

field among similar solar-type stars being difficult to imagine.

The motivation of the present paper, the second in a series,

is to check (or substantiate) the hypothesis that

stellar rotation is the decisive factor

which determines the surface Li content of solar-analogs.

One useful way to accomplish this would be to examine

the stellar activity, which is considered to be of dynamo origin

and thus deeply related to the intrinsic rotational rate. That is,

if we could confirm that

![]() is closely correlated with

the degree of activity, our speculation would be reasonably justified.

is closely correlated with

the degree of activity, our speculation would be reasonably justified.

As an indicator of stellar activity, we adopt r0(8542) (![]()

![]() ), which is the residual

flux (normalized by the continuum) at the line center of

Ca II 8542.09, the strongest line of the near-IR 8498/8542/8662

triplet of mulptiplet 2 for the 2D-2P

), which is the residual

flux (normalized by the continuum) at the line center of

Ca II 8542.09, the strongest line of the near-IR 8498/8542/8662

triplet of mulptiplet 2 for the 2D-2P![]() transition.

This is known to reflect the chromospheric activity of a star;

i.e., as the activity is enhanced, the core flux increases

because of the greater amount of filled-in emission from the chromosphere

(see, e.g., Linsky et al. 1979). This quantity is known to be well correlated with the more traditional Ca II H+K emission index (

transition.

This is known to reflect the chromospheric activity of a star;

i.e., as the activity is enhanced, the core flux increases

because of the greater amount of filled-in emission from the chromosphere

(see, e.g., Linsky et al. 1979). This quantity is known to be well correlated with the more traditional Ca II H+K emission index (

![]() )

and thus serves as a useful tool

for diagnosing the activity level of late-type stars (e.g.,

Foing et al. 1989; Chmielewski 2000; Busà et al. 2007).

)

and thus serves as a useful tool

for diagnosing the activity level of late-type stars (e.g.,

Foing et al. 1989; Chmielewski 2000; Busà et al. 2007).

In this study we aim to determine r0(8542) (a measure of

stellar activity![]() )

for each of the 118 stars studied in Paper I (a bona-fide sample of

solar analogs), based on our new spectroscopic data obtained at

Okayama Astrophysical Observatory, and examine whether or not

they show any correlation with

)

for each of the 118 stars studied in Paper I (a bona-fide sample of

solar analogs), based on our new spectroscopic data obtained at

Okayama Astrophysical Observatory, and examine whether or not

they show any correlation with

![]() ,

to test our conclusion in Paper I.

,

to test our conclusion in Paper I.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

In Sect. 2, we describe the observational material and the measurement

of r0(8542). Before discussing the results of stellar activity,

the projected rotational velocity (

![]() )

for each star is

derived in Sect. 3 by appropriately subtracting the contribution of

macroturbulence from the macrobroadening parameter (

)

for each star is

derived in Sect. 3 by appropriately subtracting the contribution of

macroturbulence from the macrobroadening parameter (

![]() )

discussed in Paper I. The discussion about the resulting

relationship between r0(8542),

)

discussed in Paper I. The discussion about the resulting

relationship between r0(8542),

![]() ,

and

,

and

![]() is presented in Sect. 4, where we show that the arguments

in Paper I have been confirmed, and our conclusions are summarized

in Sect. 5. Two additional appendices are included.

Appendix A describes the results of our reanalysis of stellar

parameters (including Li abundance) for HIP 41484, since another star

(actually HIP 41184) was erroneously observed and analyzed as if it

were HIP 41484 in Paper I. Appendix B is devoted to

discussing the sensitivity difference between two representative

activity indicators, Ca II triplet in near-IR (multiplet 2)

and Ca II H+K lines in violet region (multiplet 1), based on

some test results of non-LTE line profiles simulated with trial models.

is presented in Sect. 4, where we show that the arguments

in Paper I have been confirmed, and our conclusions are summarized

in Sect. 5. Two additional appendices are included.

Appendix A describes the results of our reanalysis of stellar

parameters (including Li abundance) for HIP 41484, since another star

(actually HIP 41184) was erroneously observed and analyzed as if it

were HIP 41484 in Paper I. Appendix B is devoted to

discussing the sensitivity difference between two representative

activity indicators, Ca II triplet in near-IR (multiplet 2)

and Ca II H+K lines in violet region (multiplet 1), based on

some test results of non-LTE line profiles simulated with trial models.

2 Residual line-center flux of Ca II 8542

To acquire data for studying stellar activities from Ca II

near-IR triplet, the observations of 118 solar-analog stars (the same sample

as in Paper I) were carried out in five different months (2007 February and

April; 2008 May, August, and December) by using the HIgh-Dispersion Echelle

Spectrograph (HIDES; Izumiura 1999) at the coudé focus of the 188 cm reflector of Okayama Astrophysical Observatory (OAO).

This HIDES, equipped with a 4K ![]() 2K CCD detector

at the camera focus, enabled us to obtain an echellogram covering

the wavelength range

2K CCD detector

at the camera focus, enabled us to obtain an echellogram covering

the wavelength range![]() of

7600-8800 Å with a resolving power of

of

7600-8800 Å with a resolving power of

![]() (for the normal slit width of 200

(for the normal slit width of 200 ![]() m) in the mode of red

cross-disperser. The observational dates for each of

the 118 stars are given in Table 1.

m) in the mode of red

cross-disperser. The observational dates for each of

the 118 stars are given in Table 1.

The data reduction (bias subtraction, flat-fielding,

aperture-determination, scattered-light subtraction,

spectrum extraction, wavelength calibration, continuum normalization)

was performed using the ``echelle'' package of IRAF![]() . Several spectral frames taken on a night were coadded to improve the signal-to-noise ratio, values as high as

. Several spectral frames taken on a night were coadded to improve the signal-to-noise ratio, values as high as

![]() being finally accomplished in most cases.

being finally accomplished in most cases.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm]{13897fg1.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13897-09/Timg26.png)

|

Figure 1: Example of our HIDES spectrum (for the case of HIP 7918) around the region of Ca II 8498/8542/8662 triplet lines, where spectra of two adjacent orders (66 and 67) are involved. Note that the strongest line (at 8542.09 Å) among the three, whose central depth was used for estimating the stellar activity, is located near to the edge of each spectrum. a) Unnormalized raw spectrum; b) Normalized spectrum with respect to the continuum level. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

An example spectrum of the Ca II triplet region is shown in

Fig. 1 (for HIP 7918). Unfortunately, the strongest

Ca II line

at 8542. 09 Å, which we use for diagnosing the stellar

activity, is situated close to the edge of the spectral order. Although

this did not cause any essential disadvantage for the present purposes,

we realized that, because of the difficulty in empirically determining

the precise continuum level, a careful readjustment of the continuum

normalization was necessary, which we carried out using Kurucz

et al.'s (1984) solar spectrum atlas as a reference standard. That is, the wing

region (

![]() Å, where

Å, where

![]() is

the distance from the line center of 8542.09 Å) of each star's

spectrum was adjusted so as to match the corresponding wing of the

reference solar spectrum. This procedure worked satisfactorily well

for all the program stars, as they are analogous to the Sun.

These reduced normalized spectra of the core region are displayed in Fig. 2 for all 118 stars (plus Moon), and the superposition of all the core-region spectra is depicted in Fig. 3. The resulting values of the residual flux at the line center of Ca II 8542,

is

the distance from the line center of 8542.09 Å) of each star's

spectrum was adjusted so as to match the corresponding wing of the

reference solar spectrum. This procedure worked satisfactorily well

for all the program stars, as they are analogous to the Sun.

These reduced normalized spectra of the core region are displayed in Fig. 2 for all 118 stars (plus Moon), and the superposition of all the core-region spectra is depicted in Fig. 3. The resulting values of the residual flux at the line center of Ca II 8542,

![]() ,

are

summarized in Table 1.

,

are

summarized in Table 1.

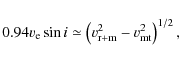

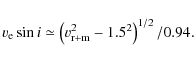

3 Rotational velocity from line width

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=16cm,clip]{13897fg2.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13897-09/Timg30.png)

|

Figure 2: Display of the Ca II 8542 line spectra for all the 118 program stars (along with the Moon/Sun). The wavelength scale of all stellar spectra is adjusted to the laboratory frame by correcting the radial velocity shifts. The HIP numbers are indicated in the figure. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

|

(1) |

where

|

(2) |

Thus obtained

While any high accuracy (e.g., compared to the case of detailed Fourier

analysis of line profiles) cannot be expected in these

![]() values, given the rough assumptions involved, we consider that they are

surely of the correct order-of-magnitude and practically useful.

Figure 4 shows the comparison of our

values, given the rough assumptions involved, we consider that they are

surely of the correct order-of-magnitude and practically useful.

Figure 4 shows the comparison of our

![]() results

with the data of Nordström et al. (2004) and Valenti & Fisher (2005), from which we can recognize an almost reasonable consistency, even though some slight systematic trend of deviation is seen.

results

with the data of Nordström et al. (2004) and Valenti & Fisher (2005), from which we can recognize an almost reasonable consistency, even though some slight systematic trend of deviation is seen.

4 Results and discussion

4.1 Rotation-lithium-activity connection

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm,clip]{13897fg3.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13897-09/Timg39.png)

|

Figure 3:

Overplot of the core-region (within |

| Open with DEXTER | |

The results of comparisons between

r0(8542),

![]() ,

and

,

and

![]() are depicted in Figs. 5a, d, and g, respectively.

are depicted in Figs. 5a, d, and g, respectively.

In Fig. 5a, we can see that

r0(8542) is closely correlated with

![]() (i.e., chromospheric activity is enhanced with increasing rotational velocity), which matches the reasonable belief that

activity is related to rotation-induced stellar dynamo. Figures 5d and g clearly show evidence of the result

we attempt here to prove: the surface Li content (

(i.e., chromospheric activity is enhanced with increasing rotational velocity), which matches the reasonable belief that

activity is related to rotation-induced stellar dynamo. Figures 5d and g clearly show evidence of the result

we attempt here to prove: the surface Li content (

![]() )

tends

to decline with a decrease in stellar activity (r0)

as well as in rotational rate (

)

tends

to decline with a decrease in stellar activity (r0)

as well as in rotational rate (

![]() )

)![]() . Since the comparatively higher rotator (

. Since the comparatively higher rotator (

![]() km s-1) with rather enhanced activity (

km s-1) with rather enhanced activity (

![]() )

have Li abundances close to the solar-system value of

)

have Li abundances close to the solar-system value of

![]() ,

from which

,

from which

![]() progressively decreases with decreasing

progressively decreases with decreasing

![]() as well as

r0(8542), we can confidently state that Li becomes increasingly depleted as the rotation is reduced

in these solar-analog stars.

as well as

r0(8542), we can confidently state that Li becomes increasingly depleted as the rotation is reduced

in these solar-analog stars.

We should here recall that the rotational velocity

(or angular momentum) is closely related to other parameters,

such as the effective temperature (

![]() )

or the stellar age (age),

because the deceleration of the rotation rate must be more effective

for lower

)

or the stellar age (age),

because the deceleration of the rotation rate must be more effective

for lower

![]() stars with thicker convection zones,

and older stars should have decelerated more than younger ones.

As implied by Figs. 5b, e, h (

stars with thicker convection zones,

and older stars should have decelerated more than younger ones.

As implied by Figs. 5b, e, h (

![]() -dependence) and

Figs. 5c,f, and i (age-dependence), such tendencies are

recognized in the sense that rotational velocities tend to be

decelerated more (or alternatively, activities as well as Li abundances

tend to be lower) for older, cooler stars. However, since these trends

are not so tight as those seen in the mutual correlations between

r0(8542),

-dependence) and

Figs. 5c,f, and i (age-dependence), such tendencies are

recognized in the sense that rotational velocities tend to be

decelerated more (or alternatively, activities as well as Li abundances

tend to be lower) for older, cooler stars. However, since these trends

are not so tight as those seen in the mutual correlations between

r0(8542),

![]() ,

and

,

and

![]() (Figs. 5a,

d, and g), we may regard stellar rotation as the most important factor

in controlling the surface Li abundance as well as the

chromospheric activity among the various influential parameters.

(Figs. 5a,

d, and g), we may regard stellar rotation as the most important factor

in controlling the surface Li abundance as well as the

chromospheric activity among the various influential parameters.

4.2 Angular momentum and envelope mixing

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm,clip]{13897fg4.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13897-09/Timg44.png)

|

Figure 4:

Comparison of the

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=17cm,clip]{13897fg5.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13897-09/Timg46.png)

|

Figure 5:

Diagrams showing the correlation between the key physical parameters of

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

In contrast, Israelian et al. (2009) could not find any

meaningful Li vs. activity correlation or any tendency

toward markedly small

![]() for planet-harboring stars,

while they confirmed the low-Li tendency of planet-host stars

in a more convincing manner.

We note, however, that their discussion is based on

the data of stars with comparatively low-

for planet-harboring stars,

while they confirmed the low-Li tendency of planet-host stars

in a more convincing manner.

We note, however, that their discussion is based on

the data of stars with comparatively low-

![]() (

(![]() 3 km s-1) as well as low-activity

(

3 km s-1) as well as low-activity

(

![]() which corresponds to

which corresponds to

![]() according to Fig. 7)

since their sample of planet-host stars are distributed

across a limited parameter range (cf. their Figs. 2a, b).

It is difficult to discuss any existence of

parameter correlations in this low-rotation/activity region

because of the progressive increase in the relative importance

of errors. The relations that we have found between

according to Fig. 7)

since their sample of planet-host stars are distributed

across a limited parameter range (cf. their Figs. 2a, b).

It is difficult to discuss any existence of

parameter correlations in this low-rotation/activity region

because of the progressive increase in the relative importance

of errors. The relations that we have found between

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

and

,

and ![]() (8542)

(being manifest when viewed over a rather wide range of

these parameters; cf. Fig. 5a, d, g) would become appreciably

unclear when we confine ourselves to this restricted region.

Therefore, we can neither exclude nor accept their result

based on their data alone (especially since they used imhomogeneous

literature data of

(8542)

(being manifest when viewed over a rather wide range of

these parameters; cf. Fig. 5a, d, g) would become appreciably

unclear when we confine ourselves to this restricted region.

Therefore, we can neither exclude nor accept their result

based on their data alone (especially since they used imhomogeneous

literature data of

![]() and

and

![]() collected

from several references). To settle this issue, far more precise

evaluation of the stellar rotation rate as well as the stellar activity

would be needed (e.g., direct determination of the rotation period

by detecting the modulation of activity indicator based on

long-term observations).

collected

from several references). To settle this issue, far more precise

evaluation of the stellar rotation rate as well as the stellar activity

would be needed (e.g., direct determination of the rotation period

by detecting the modulation of activity indicator based on

long-term observations).

After recognizing that a lithium deficiency is more likely

to take place in slower-rotation stars or planet-host stars,

the next task is to find a reasonable explanation.

Several possibilities for a rotation-mixing connection

have been proposed, such as a turbulent diffusion mixing caused

by magnetic rotational braking and an envelope mixing triggered

by tidal forces from planets (see Gonzalez (2008) or

Israelian et al. (2009) and the quoted references therein).

Based on detailed theoretical simulations, Bouvier (2008) showed

that slow rotators develop a high degree of differential rotation

between the radiative core and the convective envelope,

eventually promoting lithium depletion by enhanced mixing,

while fast rotators experience little similar core-envelope

decoupling. The Li-deficient tendency in planet-host stars may

thus be caused by their slow rotation resulting from a long lasting

star-disk interaction during the pre-main sequence phase.

This line of theoretical approach should be pursued further.

In any case, we should bear in mind that the observed evidence

of

![]() relation does not necessarily

imply a direct physical connection, but may be the result

of a long complex evolution involving different phases (such as

the pre-main sequence).

relation does not necessarily

imply a direct physical connection, but may be the result

of a long complex evolution involving different phases (such as

the pre-main sequence).

4.3 Sensitivity of Ca II 8542 as an activity index

We point out problems that remain to be clarified.

We are confident about the global rotation-activity-lithium relation

in the regions of 3 km s

![]() km s-1,

km s-1,

![]() ,

and

,

and

![]() ,

as shown

in Figs. 5a, d, and g. However, little can be said about

the comparatively low-rotation/activity/Li regions of

,

as shown

in Figs. 5a, d, and g. However, little can be said about

the comparatively low-rotation/activity/Li regions of

![]() km s-1,

km s-1,

![]() ,

and

,

and

![]() ,

where

r0(8542) tends to converge for

the value of

,

where

r0(8542) tends to converge for

the value of ![]() 0.2, and

0.2, and

![]() as well as

as well as

![]() are indefinite because they are close to the detection limit.

This situation is apparent in the histograms of

r0(8542),

are indefinite because they are close to the detection limit.

This situation is apparent in the histograms of

r0(8542),

![]() ,

and

,

and

![]() shown in Figs. 6a-c.

How could this large dispersion in

shown in Figs. 6a-c.

How could this large dispersion in

![]() (of more than

(of more than ![]() 1 dex)

be explained at

1 dex)

be explained at

![]() ,

despite

r0(8542)being stabilized at

,

despite

r0(8542)being stabilized at ![]() 0.2 (cf. Fig. 2d)?

0.2 (cf. Fig. 2d)?

In our opinion, this implies that the core flux of

Ca II 8542 line is no longer a useful indicator;

i.e., this line is too insensitive to any change in activity

at this low-activity level. We confirmed by means of our

non-LTE line-formation calculation (cf. Appendix B) that

the core-flux of Ca II 8542 is not so sensitive to a mild

chromospheric temperature rise (unless the temperature becomes

sufficiently high to reach a certain threshold level; cf. Fig. B.1c),

which makes itself rather unsuitable to studying the stellar activity

at a lower level. This must be the reason for the convergence

of

r0(8542) at ![]() 0.2.

0.2.

In contrast, our non-LTE calculation suggested that the core

emission of Ca II K line at 3934 ![]() is sensitive

to the chromospheric temperature enhancement of any degree (cf. Fig. B.1b),

from which we may conclude that Ca II H+K violet lines are

more useful and practical (than Ca II near-IR triplet lines) at least

for investigating the mild stellar activity of comparatively slow rotators.

We can see from Fig. 7 that, while a reasonable

correlation exists between

r0(8542) and

is sensitive

to the chromospheric temperature enhancement of any degree (cf. Fig. B.1b),

from which we may conclude that Ca II H+K violet lines are

more useful and practical (than Ca II near-IR triplet lines) at least

for investigating the mild stellar activity of comparatively slow rotators.

We can see from Fig. 7 that, while a reasonable

correlation exists between

r0(8542) and

![]() index

(measure of the core emission strength of Ca II H+K lines),

index

(measure of the core emission strength of Ca II H+K lines),

![]() still exhibits an appreciable dispersion around

still exhibits an appreciable dispersion around

![]() -5, whereas

r0(8542) stabilizes at

-5, whereas

r0(8542) stabilizes at ![]() 0.2.

This means that we still may have a chance to study the

rotation-activity-lithium connection of comparatively slow

rotators (

0.2.

This means that we still may have a chance to study the

rotation-activity-lithium connection of comparatively slow

rotators (

![]() km s-1, where Ca II IR

triplet is no more effective) by studying the Ca II H+K lines.

Additional investigation along these lines would be

worthwhile as we proceed to the next step.

km s-1, where Ca II IR

triplet is no more effective) by studying the Ca II H+K lines.

Additional investigation along these lines would be

worthwhile as we proceed to the next step.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=7.5cm,clip]{13897fg6.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13897-09/Timg59.png)

|

Figure 6:

Histograms showing the distributions of a)

r0(8542); b)

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=7.5cm,clip]{13897fg7.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13897-09/Timg60.png)

|

Figure 7:

Correlation of the

r0(8452) values determined in this study with the

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

5 Conclusion

In our previous study of Paper I, we carried out a comprehensive spectroscopic analysis of 118 solar analogs to clarify why the strengths of Li I 6708 line in these Sun-like stars are considerably diversified despite that they have stellar parameters quite similar to each other, and interestingly found a close relationship between the Li abundance and its line-width. We then proposed that stellar rotation may be the most important parameter in determining the surface Li content.

In this paper, we have tried to test this hypothesis

by examining whether any correlation exists between

the stellar activity and the Li abundance, as expected

because of the widely believed rotation-activity connection.

As an indicator of stellar activity, we used the residual line-center

flux of the strong Ca II 8542 line (r0), which was measured

from the high-dispersion near-IR spectra obtained with the 188 cm

reflector and the HIDES spectrograph at Okayama Astrophysical Observatory.

The projected rotational velocity (

![]() )

was

reasonably accurately estimated by subtracting the contribution of the

macroturbulence effect from the line-broadening width (

)

was

reasonably accurately estimated by subtracting the contribution of the

macroturbulence effect from the line-broadening width (

![]() )

as we already established in Paper I.

)

as we already established in Paper I.

Clear correlations have been confirmed in the diagrams

![]() vs.

r0(8542),

r0(8542) vs.

vs.

r0(8542),

r0(8542) vs.

![]() ,

and

,

and

![]() vs.

vs.

![]() ,

which support the arguments that (1) the stellar activity

surely depends upon the rotational rate,

and that (2) the atmospheric Li abundance of solar-analog stars

declines progressively as the rotational velocity decreases.

,

which support the arguments that (1) the stellar activity

surely depends upon the rotational rate,

and that (2) the atmospheric Li abundance of solar-analog stars

declines progressively as the rotational velocity decreases.

We thus concluded that a Li-depletion mechanism in these Sun-like stars, most probably caused by effective envelope mixing, operates more efficiently as the stellar rotation slows down. In this context, it may be interesting/enlightening to interpret the observational finding of a low-Li tendency of planet-host G dwarfs within the framework of the rotational properties (i.e., difference in the angular momentum), as stated in the theoretical prediction by Bouvier (2008). Additional detailed investigations along those lines would be worthwhile.

However, the cause of this interconnection, which is found

for comparatively high-rotation/activity/Li stars, remains unclear

for the group of stars with low-rotation/activity/Li, where

r0(8542)

tends to converge and stabilize at ![]() 0.2 and can no longer be

a useful activity indicator. Since we found from our non-LTE calculation

that Ca II H+K violet lines at 3968/3934

0.2 and can no longer be

a useful activity indicator. Since we found from our non-LTE calculation

that Ca II H+K violet lines at 3968/3934 ![]() are more sensitive

and useful (than Ca II IR triplet lines) for investigating the

mild stellar activity of comparatively slow rotators, it would be

beneficial to revisit this problem by studying these Ca II H+K lines

in greater detail.

are more sensitive

and useful (than Ca II IR triplet lines) for investigating the

mild stellar activity of comparatively slow rotators, it would be

beneficial to revisit this problem by studying these Ca II H+K lines

in greater detail.

We thank the staff of the Okayama Astrophysical Observatory for their kind and elaborate support in the observations.Constructive comments from an anonymous referee concerning the interpretation of low-Li tendency in planet-host stars are also acknowledged.

Appendix A: Reanalysis of HIP 41484

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=7.8cm,clip]{13897fgA1.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13897-09/Timg61.png)

|

Figure A.1:

Spectrum fitting analysis applied to selected wavelength regions of

HIP 41484. The observed and theoretical spectra are shown by open

(line-connected) circles and solid lines, respectively. a) 6591-6599 |

| Open with DEXTER | |

In the course of this study, we noticed that the near-IR spectrum

of HIP 41484 obtained for this study and the red-region

spectrum used in Paper I were apparently inconsistent with each other.

After careful inspection of the observational information

(e.g., telescope pointing ![]() ), we then realized that the red spectrum

obtained for this star in 2005 November 26 was not that

of HIP 41484 but that of HIP 41184

(which was also one of our solar-analog targets); i.e.,

we had mistakenly observed the incorrect star because of the similarity

in their HIP number

), we then realized that the red spectrum

obtained for this star in 2005 November 26 was not that

of HIP 41484 but that of HIP 41184

(which was also one of our solar-analog targets); i.e.,

we had mistakenly observed the incorrect star because of the similarity

in their HIP number![]() .

.

Since an erroneous spectrum was eventually used in Paper I, all the

spectrum-related quantities derived therein were also wrong. We thus

carried out an entire reanalysis of HIP 41484 based on the new spectrum

used for this study, where a long wavelength range of 6300-10 000 ![]() was fortunately available (thanks to the 3 mosaicked CCDs; cf. footnote 2)

in addition to the main region of 7600-8800

was fortunately available (thanks to the 3 mosaicked CCDs; cf. footnote 2)

in addition to the main region of 7600-8800 ![]() including the Ca II triplet. The atmospheric parameters (

including the Ca II triplet. The atmospheric parameters (

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

and [Fe/H]) were derived from the Fe I and Fe II lines

6300-7600

,

and [Fe/H]) were derived from the Fe I and Fe II lines

6300-7600 ![]() region. Since the 6080-6089

region. Since the 6080-6089 ![]() region

used in Paper I to evaluate the line-broadening width by the

spectrum-fitting method was not available in the present case,

we instead used the 6591-6599

region

used in Paper I to evaluate the line-broadening width by the

spectrum-fitting method was not available in the present case,

we instead used the 6591-6599 ![]() region for this purpose (Fig. A.1a). The Li abundance was determined from the Li I doublet at 6708

region for this purpose (Fig. A.1a). The Li abundance was determined from the Li I doublet at 6708 ![]() (Fig. A.1b).

Otherwise, all the relevant stellar parameters were established in the

same way as in Paper I. The results of this reanalysis are

summarized in Table A.1.

(Fig. A.1b).

Otherwise, all the relevant stellar parameters were established in the

same way as in Paper I. The results of this reanalysis are

summarized in Table A.1.

Table A.1: Redetermined stellar parameters and physical quantities of HIP 41484.

Appendix B: Ca II H+K doublet and near-IR triplet as stellar-activity indicators

It is well known that the cores of strong Ca II lines,

such as the resonance H+K doublet lines (at 3968 and 3934 ![]() )

or the near-IR triplet lines (at 8498/8542/8662

)

or the near-IR triplet lines (at 8498/8542/8662 ![]() ),

reflect the temperature structure of the upper atmosphere

and may be used as useful indicators of chromospheric activity.

However, does any difference exist between these two activity indicators

in their practical applications; do they have any specific strong or

weak points depending on situations?

To answer this, we tried to compute the profiles of

Ca II 3934 and Ca II 8542 lines for several test model

atmospheres with different chromospheric effects,

and examine how the core fluxes of these two lines respond to

the temperature profile of upper atmospheres.

),

reflect the temperature structure of the upper atmosphere

and may be used as useful indicators of chromospheric activity.

However, does any difference exist between these two activity indicators

in their practical applications; do they have any specific strong or

weak points depending on situations?

To answer this, we tried to compute the profiles of

Ca II 3934 and Ca II 8542 lines for several test model

atmospheres with different chromospheric effects,

and examine how the core fluxes of these two lines respond to

the temperature profile of upper atmospheres.

We must take into account non-LTE effects, because

the dilution of the line source function in the upper optically-thin

layer determines the intensity/flux level at the core.

Non-LTE statistical-equilibrium calculations directed specifically

toward studying the formation of these strong Ca II lines

in the chromosphere have been few in number![]() .

Except for the pioneering work on a simple 3-level Ca II model

ion (e.g., Linsky & Avrett 1970 for the H+K lines; Linsky et al. 1979

for the 8542 line), the only relevant non-LTE study quotable here

may be, to our knowledge, that of Andretta et al. (2005),

who computed (based on a model atom comprising 18 Ca I and

5 Ca II levels) the 8498/8542/8662 line profiles for various

solar models including a semi-empirical one with the chromosphere.

.

Except for the pioneering work on a simple 3-level Ca II model

ion (e.g., Linsky & Avrett 1970 for the H+K lines; Linsky et al. 1979

for the 8542 line), the only relevant non-LTE study quotable here

may be, to our knowledge, that of Andretta et al. (2005),

who computed (based on a model atom comprising 18 Ca I and

5 Ca II levels) the 8498/8542/8662 line profiles for various

solar models including a semi-empirical one with the chromosphere.

We dealt with this problem here using a more detailed atomic

model of calcium (111/50 terms and 2376/313 radiative transitions

for Ca I/Ca II), comprising up to

Ca I 4![]() 16

16![]() 3D (48830 cm-1 from the ground level) and Ca II 3p6 16d 2D (93895 cm-1 from the ground level), which was constructed from the atomic-line database compiled by Kurucz & Bell (1995). The electron collision cross-sections relevant to the lowest 7 terms of Ca II were taken from Burgess et al. (1995). The data from TOPbase (Cunto & Mendoza 1992) were adopted for the photoionization cross-sections for the lowest 7 and 10 terms of Ca I and Ca II, respectively. As for other computational details (e.g., electron-collision rates as well as

photoionization rates for the remaining terms not mentioned above,

collisional ionization rates, treatment of collisions

with neutral-hydrogen atoms), we followed the recipe

described in Sect. 3.1.3 of Takeda (1991).

3D (48830 cm-1 from the ground level) and Ca II 3p6 16d 2D (93895 cm-1 from the ground level), which was constructed from the atomic-line database compiled by Kurucz & Bell (1995). The electron collision cross-sections relevant to the lowest 7 terms of Ca II were taken from Burgess et al. (1995). The data from TOPbase (Cunto & Mendoza 1992) were adopted for the photoionization cross-sections for the lowest 7 and 10 terms of Ca I and Ca II, respectively. As for other computational details (e.g., electron-collision rates as well as

photoionization rates for the remaining terms not mentioned above,

collisional ionization rates, treatment of collisions

with neutral-hydrogen atoms), we followed the recipe

described in Sect. 3.1.3 of Takeda (1991).

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=6.5cm,clip]{13897fgB1.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13897-09/Timg88.png)

|

Figure B.1: Test simulations for the core profiles of Ca II 3934 (K) line and Ca II 8542 line, based on the non-LTE calculations carried out on three model atmospheres (Models C, M, and E) with different temperature structures at the upper atmosphere. a) Temperature profiles of Models C, M, and E. b) Simulated (flux) profiles of the Ca II 3934 line; c) simulated (flux) profiles of the Ca II 8542 line. In panels b) and c), Kurucz et al.'s (1984) solar flux spectra are also indicated by open circles. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

We tested three solar atmospheric models (

![]() K,

K,

![]() ,

[Fe/H] = 0.0) that have different temperature profiles

only at the upper layer of

,

[Fe/H] = 0.0) that have different temperature profiles

only at the upper layer of

![]() .

Model C has

a chromospheric temperature structure similar to that of the semi-empirical

solar model of Maltby et al. (1986). Model E is equivalent to

Kurucz's (1979) ATLAS6 solar model (without any temperature rise), and Model M corresponds to the mean of these two (cf. Fig. B.1a). The pressure/density structures of these models were obtained by integrating the equation of hydrostatic equilibrium.

We refer to Sect. 2.1 of Takeda (1995b)

for more details about how Models C and E were constructed.

We applied a depth-dependent microturbulence by adopting the turbulent

velocity fields given in Table 11 of Maltby et al. (1986).

.

Model C has

a chromospheric temperature structure similar to that of the semi-empirical

solar model of Maltby et al. (1986). Model E is equivalent to

Kurucz's (1979) ATLAS6 solar model (without any temperature rise), and Model M corresponds to the mean of these two (cf. Fig. B.1a). The pressure/density structures of these models were obtained by integrating the equation of hydrostatic equilibrium.

We refer to Sect. 2.1 of Takeda (1995b)

for more details about how Models C and E were constructed.

We applied a depth-dependent microturbulence by adopting the turbulent

velocity fields given in Table 11 of Maltby et al. (1986).

The resulting profiles of Ca II 3934 and 8542 lines are

depicted in Figs. B.1b, c, respectively, where the corresponding

solar flux spectra of Kurucz et al. (1984)

are also shown for comparison. It can be seen that the computed

profiles for Model C, which is likely to be the most realistic

among the three, do not reproduce the true solar spectra well (i.e.,

the core flux level is too high), indicating that our modeling is still

imperfect. However, our intention here is not to accomplish excellent

fitting between theory and observation, but to ascertain/determine

whether and how the sensitivity to the upper temperature differs

between these two lines. From this standpoint, we can recognize an

important result in these figures: The strength of the core emission in

the

Ca II 3934 line progressively increases in accordance with

the temperature rise in the upper layer as

Model E

![]() Model M

Model M

![]() Model C (Fig. B.1b).

In contrast, the residual core flux of Ca I 8542 line barely

differs for Models E and M, while that for Model C is

appreciably higher (Fig. B.1c), which means that this indicator

is not very useful for studying the moderate temperature enhancement

(mild chromospheric activity) because of its rather inefficient

response until the temperature rise goes over a certain threshold level.

Consequently, we may conclude that those who intend to study the

nature of comparatively mild stellar activity in slower rotators

should use the Ca II H+K lines at 3934/3968

Model C (Fig. B.1b).

In contrast, the residual core flux of Ca I 8542 line barely

differs for Models E and M, while that for Model C is

appreciably higher (Fig. B.1c), which means that this indicator

is not very useful for studying the moderate temperature enhancement

(mild chromospheric activity) because of its rather inefficient

response until the temperature rise goes over a certain threshold level.

Consequently, we may conclude that those who intend to study the

nature of comparatively mild stellar activity in slower rotators

should use the Ca II H+K lines at 3934/3968 ![]() ,

rather than the Ca II triplet lines at 8498/8542/8662

,

rather than the Ca II triplet lines at 8498/8542/8662 ![]() .

.

References

- Andretta, V., Busà, I., Gomez, M. T., et al. 2005, A&A, 430, 669 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Bouvier, J. 2008, A&A, 489, L53 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess, A., Chidichimo, M. C., & Tully, J. A. 1995, A&A, 300, 627 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Busà, I., Aznar Cuadrado, R., Terranegra, L., Andretta, V., & Gomez, M. T. 2007, A&A, 466, 1089 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Chmielewski, Y. 2000, A&A, 353, 666 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Cunto, W., & Mendoza, C. 1992, Rev. Mex. Astron. Astrofis., 23, 107 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Drake, J. J. 1991, MNRAS, 251, 369 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Foing, B. H., Crivellari, L., Vladilo, G., Rebolo, R., & Beckman, J. E. 1989, A&AS, 80, 189 [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, G. 2008, MNRAS, 386, 928 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Israelian, G., Santos, N. C., Mayor, M., et al. 2004, A&A, 414, 601 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Israelian, G., Delgado Mena, E., Santos, N. C., et al. 2009, Nature, 462, 189 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izumiura, H. 1999, in Proc. 4th East Asian Meeting on Astronomy, Observational Astrophysics in Asia and its Future ed. P. S. Chen (Kunming: Yunnan Observatory), 77 [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen, U. G., Carlsson, M., & Johnson, H. R. 1992, A&A, 254, 258 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Kurucz, R. L. 1979, ApJS, 40, 1 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kurucz, R. L., & Bell, B. 1995, Kurucz CD-ROM, No. 23 (Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics) [also available at http://kurucz.harvard.edu/LINELISTS.html] [Google Scholar]

- Kurucz, R. L., Furenlid, I., Brault, J., et al. 1984, Solar Flux Atlas from 296 to 1300 nm (Sunspot, New Mexico: National Solar Observatory) [digital version available at http://kurucz.harvard.edu/sun.html] [Google Scholar]

- Linsky, J. L., & Avrett, E. H. 1970, PASP, 82, 169 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Linsky, J. L., Hunten, D. M., Sowell, R., Glackin, D. L., & Kelch, W. L. 1979, ApJS, 41, 481 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mallik, S. V. 1997, A&AS, 124, 359 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Maltby, P., Avrett, E. H., Carlsson, M., et al. 1986, ApJ, 306, 284 [Google Scholar]

- Mashonkina, L., Korn, A. J., & Przybilla, N. 2007, A&A, 461, 261 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Nordström, B., Mayor, M., Andersen, J., et al. 2004, A&A, 418, 989 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Strassmeier, K., Washuettl, A., Granzer, Th., Scheck, M., & Weber, M. 2000, A&AS, 142, 275 [Google Scholar]

- Takeda, Y. 1991, A&A, 242, 455 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda, Y. 1995a, PASJ, 47, 337 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda, Y. 1995b, PASJ, 47, 463 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda, Y., & Tajitsu, A. 2009, PASJ, 61, 471 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda, Y., Kawanomoto, S., Honda, S., Ando, H., & Sakurai, T. 2007, A&A, 468, 663 (Paper I) [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Valenti, J. A., & Fisher, D. A. 2005, ApJS, 159, 141 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [MathSciNet] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, T., & Steenbock, W. 1985, A&A, 149, 21 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Wright, J. T., Marcy, G. W., Butler, R. P., et al. 2004, ApJS, 152, 261 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Table 1: Activity index, rotation, Li abundance, age, and the atmospheric parameters.

Footnotes

- ... stars

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- Based on observations carried out at Okayama Astrophysical Observatory (Okayama, Japan).

- ... activity

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- Of course, this

r0(8542) index depends not only on the chromospheric activity but also

on atmospheric parameters such as

(effective temperature),

(effective temperature),

(surface gravity), and [Fe/H] (metallicity) (e.g., Mallik 1997; Chmielewski 2000). However, in the present sample of solar analogs similar to each other, the mutual differences of these stellar parameters

are of secondary importance and can be neglected to a first approximation.

(surface gravity), and [Fe/H] (metallicity) (e.g., Mallik 1997; Chmielewski 2000). However, in the present sample of solar analogs similar to each other, the mutual differences of these stellar parameters

are of secondary importance and can be neglected to a first approximation.

- ... range

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- Since the beginning of 2008, three mosaicked

CCD chips had become newly available in HIDES, resulting in a three-times

wider wavelength coverage than before. Accordingly, for the data of

2008 May, August, and December, spectra in two adjacent wavelength ranges

(6300-7600 Åand 8800-10 000 Å) were also recorded in

addition to the target region of 7600-8800

.

.

- ... IRAF

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- IRAF is distributed by the National Optical Astronomy Observatories, which is operated by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy, Inc., under cooperative agreement with the National Science Foundation.

- ...

)

)![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- We should remark that the residual intensity at the core gets more or less

raised as

becomes higher due to the blurring effect

(caused by correspondingly wider rotational broadening function being convolved). However, we can see from Fig. 5a

(see the dotted line therein) that this effect is quantitatively

insignificant compared to the main trend (symbols) which must thus be

real.

becomes higher due to the blurring effect

(caused by correspondingly wider rotational broadening function being convolved). However, we can see from Fig. 5a

(see the dotted line therein) that this effect is quantitatively

insignificant compared to the main trend (symbols) which must thus be

real.

- ... number

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- As a result, HIP 41184 was unintentionally observed twice. In Figs. 6 and 8 in Paper I, the two spectra labeled as ``41184'' and ``41484'' actually correspond to the same star (HIP 41184).

- ... number

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- More precisely, several other non-LTE studies of calcium lines in late-type stars (e.g., Watanabe & Steenbock 1985; Drake 1991; Jørgensen et al. 1992; Mashonkina et al. 2007), focusing mainly on non-LTE abundance corrections, do not explicitly address the chromospheric effect (core emission) on the formation of these activity-sensitive Ca II lines under question.

All Tables

Table A.1: Redetermined stellar parameters and physical quantities of HIP 41484.

Table 1: Activity index, rotation, Li abundance, age, and the atmospheric parameters.

All Figures

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm]{13897fg1.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13897-09/Timg26.png)

|

Figure 1: Example of our HIDES spectrum (for the case of HIP 7918) around the region of Ca II 8498/8542/8662 triplet lines, where spectra of two adjacent orders (66 and 67) are involved. Note that the strongest line (at 8542.09 Å) among the three, whose central depth was used for estimating the stellar activity, is located near to the edge of each spectrum. a) Unnormalized raw spectrum; b) Normalized spectrum with respect to the continuum level. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=16cm,clip]{13897fg2.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13897-09/Timg30.png)

|

Figure 2: Display of the Ca II 8542 line spectra for all the 118 program stars (along with the Moon/Sun). The wavelength scale of all stellar spectra is adjusted to the laboratory frame by correcting the radial velocity shifts. The HIP numbers are indicated in the figure. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm,clip]{13897fg3.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13897-09/Timg39.png)

|

Figure 3:

Overplot of the core-region (within |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm,clip]{13897fg4.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13897-09/Timg44.png)

|

Figure 4:

Comparison of the

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=17cm,clip]{13897fg5.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13897-09/Timg46.png)

|

Figure 5:

Diagrams showing the correlation between the key physical parameters of

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=7.5cm,clip]{13897fg6.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13897-09/Timg59.png)

|

Figure 6:

Histograms showing the distributions of a)

r0(8542); b)

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=7.5cm,clip]{13897fg7.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13897-09/Timg60.png)

|

Figure 7:

Correlation of the

r0(8452) values determined in this study with the

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=7.8cm,clip]{13897fgA1.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13897-09/Timg61.png)

|

Figure A.1:

Spectrum fitting analysis applied to selected wavelength regions of

HIP 41484. The observed and theoretical spectra are shown by open

(line-connected) circles and solid lines, respectively. a) 6591-6599 |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=6.5cm,clip]{13897fgB1.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13897-09/Timg88.png)

|

Figure B.1: Test simulations for the core profiles of Ca II 3934 (K) line and Ca II 8542 line, based on the non-LTE calculations carried out on three model atmospheres (Models C, M, and E) with different temperature structures at the upper atmosphere. a) Temperature profiles of Models C, M, and E. b) Simulated (flux) profiles of the Ca II 3934 line; c) simulated (flux) profiles of the Ca II 8542 line. In panels b) and c), Kurucz et al.'s (1984) solar flux spectra are also indicated by open circles. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

Copyright ESO 2010

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.