| Issue |

A&A

Volume 515, June 2010

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A80 | |

| Number of page(s) | 12 | |

| Section | The Sun | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/200913024 | |

| Published online | 11 June 2010 | |

The spatial damping of magnetohydrodynamic waves in a flowing partially ionised prominence plasma

M. Carbonell1 - P. Forteza2 - R. Oliver2 - J. L. Ballester2

1 - Departament de Matemàtiques i Informàtica, Universitat de les Illes Balears, 07122 Palma de Mallorca, Spain

2 - Departament de Física, Universitat de les Illes Balears, 07122 Palma de Mallorca, Spain

Received 30 July 2009 / Accepted 1 February 2010

Abstract

Context. Solar prominences are partially ionised plasmas

displaying flows and oscillations. These oscillations exhibit time and

spatial damping and have commonly been explained in terms of

magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) waves.

Aims. We study the spatial damping of linear non-adiabatic MHD

waves in a flowing partially ionised plasma with prominence-like

physical properties.

Methods. We consider single fluid equations for a partially

ionised hydrogen plasma by including in the energy equation optically

thin radiation, thermal conduction by electrons and neutrals, and

heating. By keeping ![]() real and fixed, we solved the dispersion relations obtained for the complex wavenumber, k,

and analysed the behaviour of the damping length, wavelength and the

ratio of the damping length to the wavelength, versus period, for

Alfvén, fast, slow, and thermal waves.

real and fixed, we solved the dispersion relations obtained for the complex wavenumber, k,

and analysed the behaviour of the damping length, wavelength and the

ratio of the damping length to the wavelength, versus period, for

Alfvén, fast, slow, and thermal waves.

Results. In the presence of a background flow, the results

indicate that new strongly damped fast and Alfvén waves appear that

depend on the joint action of flow and resistivity. The damping lengths

of adiabatic fast and slow waves are strongly affected by partial

ionisation, which also modifies the ratio between damping lengths and

wavelengths. The behaviour of adiabatic fast waves also resembles that

of Alfvén waves. For non-adiabatic slow waves, the unfolding in both

wavelength and damping length induced by the flow allows efficient

damping to be found for periods compatible with those observed in

prominence oscillations. This effect is enhanced when low ionised

plasmas are considered.

Conclusions. Since flows are ubiquitous in prominences, in the

case of non-adiabatic slow waves and within the range of periods of

interest for prominence oscillations, the joint effect of both flow and

partial ionisation leads to a ratio of damping length to wavelength

denoting a very efficient spatial damping. For fast and Alfvén waves,

the most efficient damping occurs at very short periods not compatible

with those observed in prominence oscillations.

Key words: Sun: oscillations - magnetic fields - Sun: filaments, prominences

1 Introduction

A solar prominence is a cool (

![]() K) and dense (

K) and dense (

![]() kg/m3) mass of gas located in the much

denser and hotter solar corona. Although it is poorly understood

how this structure persists for a long time within the solar corona,

it is thought that its support and thermal isolation are of magnetic

origin. Thanks to ground and space-based observations, small-amplitude oscillations in prominences

and filaments have been detected and details about their

properties can be found in Oliver and Ballester (2002), Banerjee et al. (2007), Oliver (2009), and Mackay et al. (2010). The

oscillations are mainly detected by the periodic Doppler shifts of

spectral lines, with periods from a few minutes to hours, and the

observations have shown that they are local in origin, that they can

be coherent over large regions of prominences/filaments, that

simultaneously flowing and oscillating features are present, and

that oscillations display time and spatial damping (Terradas et al.

2002). These small-amplitude oscillations have been commonly

interpreted in terms of linear magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) waves and

the damping of oscillations has been studied by considering

different dissipative mechanisms. For instance, in the case of

fully ionised plasmas, the time damping of prominence oscillations

has been studied by considering non-adiabatic MHD waves, including

the effects of optically thin radiation, thermal conduction, and

heating, in unbounded and bounded prominence plasmas (Carbonell et al. 2004; Terradas et al. 2005). By assuming that the threads of

which the solar filaments consist can be modeled as cylindrical flux

tubes, the time damping of homogeneous and inhomogeneous cylindrical

flux tubes, with prominence physical conditions, has been modeled

using thermal mechanisms and resonant absorption, respectively

(Soler et al. 2008; Arregui et al. 2008; Soler et al. 2009b).

kg/m3) mass of gas located in the much

denser and hotter solar corona. Although it is poorly understood

how this structure persists for a long time within the solar corona,

it is thought that its support and thermal isolation are of magnetic

origin. Thanks to ground and space-based observations, small-amplitude oscillations in prominences

and filaments have been detected and details about their

properties can be found in Oliver and Ballester (2002), Banerjee et al. (2007), Oliver (2009), and Mackay et al. (2010). The

oscillations are mainly detected by the periodic Doppler shifts of

spectral lines, with periods from a few minutes to hours, and the

observations have shown that they are local in origin, that they can

be coherent over large regions of prominences/filaments, that

simultaneously flowing and oscillating features are present, and

that oscillations display time and spatial damping (Terradas et al.

2002). These small-amplitude oscillations have been commonly

interpreted in terms of linear magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) waves and

the damping of oscillations has been studied by considering

different dissipative mechanisms. For instance, in the case of

fully ionised plasmas, the time damping of prominence oscillations

has been studied by considering non-adiabatic MHD waves, including

the effects of optically thin radiation, thermal conduction, and

heating, in unbounded and bounded prominence plasmas (Carbonell et al. 2004; Terradas et al. 2005). By assuming that the threads of

which the solar filaments consist can be modeled as cylindrical flux

tubes, the time damping of homogeneous and inhomogeneous cylindrical

flux tubes, with prominence physical conditions, has been modeled

using thermal mechanisms and resonant absorption, respectively

(Soler et al. 2008; Arregui et al. 2008; Soler et al. 2009b).

A typical feature in prominence oscillations are flows observed in H![]() ,

UV, and EUV lines (Labrosse et al. 2010). In H

,

UV, and EUV lines (Labrosse et al. 2010). In H![]() quiescent filaments, the observed velocities range from 5 to 20 km s-1 (Zirker et al. 1998; Lin et al. 2003, 2007) and, because of

the physical conditions in filament plasma, they seem to be

field-aligned. In the case of active region prominences, flow

speeds can be higher. Observations made with

Hinode/SOT by Okamoto et al. (2007) detected

synchronous vertical oscillatory motions in the threads of an active

region prominence, and flows along the

same threads. However, in limb prominences different kinds of flows

are observed and, for instance, observations made by Berger et al.

(2008) with Hinode/SOT uncovered a complex dynamics with vertical

downflows and upflows. Taking all this into account, Carbonell et al.

(2009) explored the time damping of non-adiabatic slow and thermal waves in an unbounded prominence medium with a background flow,

while Soler et al. (2008, 2009a)

investigated the time damping of the oscillations of an individual

prominence thread and of a threaded prominence when both mass flows and

non-adiabatic processes are considered.

quiescent filaments, the observed velocities range from 5 to 20 km s-1 (Zirker et al. 1998; Lin et al. 2003, 2007) and, because of

the physical conditions in filament plasma, they seem to be

field-aligned. In the case of active region prominences, flow

speeds can be higher. Observations made with

Hinode/SOT by Okamoto et al. (2007) detected

synchronous vertical oscillatory motions in the threads of an active

region prominence, and flows along the

same threads. However, in limb prominences different kinds of flows

are observed and, for instance, observations made by Berger et al.

(2008) with Hinode/SOT uncovered a complex dynamics with vertical

downflows and upflows. Taking all this into account, Carbonell et al.

(2009) explored the time damping of non-adiabatic slow and thermal waves in an unbounded prominence medium with a background flow,

while Soler et al. (2008, 2009a)

investigated the time damping of the oscillations of an individual

prominence thread and of a threaded prominence when both mass flows and

non-adiabatic processes are considered.

Although there is a large amount of observational evidence about the time damping of MHD waves propagating in coronal structures such as coronal loops or prominences, current observational information about the spatial damping of MHD waves in coronal structures remains scarce. Time damping is usually produced when an impulsive perturbation excites a medium and waves begin to propagate, then, the wave amplitude decreases as time goes by. Alternatively, if the medium is excited by a continuous driver with a fixed frequency, the spatial damping is detected by the decrease in the amplitude as the wave propagates. Since, probably, most of the phenomena exciting waves in solar structures are impulsive in origin rather than produced by continuous drivers, time damping of waves is more often observed.

Using thermal conduction,

compressive viscosity, gravitational stratification, and field line

divergence, De Moortel et al. (2002) and De Moortel & Hood (2003,

2004) studied the spatial damping of driven and non-driven slow MHD

waves in coronal conditions and applied the results obtained to the

case of standing and propagating slow waves in coronal loops

observed with SOHO and TRACE. In the case of prominences, Terradas

et al. (2002) analysed small amplitude oscillations in a polar

crown prominence detecting both a plane propagating wave and a

standing wave. The plane wave propagates in opposite directions

with wavelengths of 67 500 and 50 000 km and phase speeds of

15 km s-1 and 12 km s-1, while in the case of the

standing wave, the estimated wavelength is 44 000 km and the

phase speed 12 km s-1. These authors also reported that for

the propagating wave, which was interpreted as a slow MHD wave, the

amplitude of the oscillations spatially decreases significantly over

a distance of

![]() km from the location where wave

motion was being generated. This distance can be considered as a

typical spatial damping length,

km from the location where wave

motion was being generated. This distance can be considered as a

typical spatial damping length, ![]() ,

of the oscillations.

,

of the oscillations.

From the theoretical point of view and assuming a fully ionised plasma, Ballai (2003) qualitatively studied the spatial damping of linear compressional waves in solar prominences by considering different dissipative mechanisms, such as isotropic and anisotropic viscosity, isotropic magnetic diffusivity, isotropic radiative damping (Newton's law), and anisotropic thermal conduction. The conclusions were that thermal radiation can damp compressional waves and that waves can also be damped by anisotropic thermal conduction provided that they have short enough wavelengths. Using linear non-adiabatic MHD waves including optically thin radiation, thermal conduction, and heating, Carbonell et al. (2006) quantitatively studied the spatial damping of slow, fast, and thermal waves in a fully ionised unbounded prominence medium. In the frequency space, they determined the regions where radiation or thermal conduction are the dominant damping mechanisms, the critical frequencies at which the dominance changes from one mechanism to another, and that different heating mechanisms do not strongly affect the damping. The most important conclusions were that the thermal wave propagates but is strongly damped, and that slow waves are efficiently damped by thermal effects, which does not happen for fast waves. Singh et al. (2006) performed a similar study but considering only Newtonian radiation and, later, Singh et al. (2007) considered again the same problem including Newtonian radiation and turbulent viscosity.

The typical composition of solar prominences is ![]() hydrogen and

hydrogen and

![]() helium. They constitute partially ionised plasmas since

hydrogen lines are observed (Labrosse et al. 2010). The exact

ionisation degree of prominences is unknown and the ratio of

electron density to neutral hydrogen density seems to be in the

interval 0.1-10 (Patsourakos & Vial 2002). From a

theoretical point of view, partial ionisation was considered by

Mercier and Heyvaerts (1977) when they studied the difusion of

neutral atoms by gravity. Gilbert et al. (2002) studied the

diffusion of neutral atoms in a partially ionized prominence plasma,

concluding that the loss timescale is much longer for hydrogen than

for helium. Gilbert et al. (2007) investigated the temporal and

spatial variations in the relative abundance of helium with respect

to hydrogen in a sample of filaments. They found that a majority of

filaments show a deficit of helium in the top part, while in the

bottom part there is an excess. This seems to be due to the shorter

loss timescale of neutral helium compared to that of neutral

hydrogen. The consideration of prominences as partially

ionised plasma is extremely important for the physics of

prominences, and the effects on MHD waves in prominences need to be

taken into account. From the theoretical point of view, and in the

framework of laboratory plasma physics, there is an extensive amount

of literature about wave propagation in a partially ionized

multifluid plasma (Watanabe 1961a,b; Tanenbaum 1961; Tanenbaum &

Mintzer 1962; Woods 1962; Kulsrud & Pearce 1969; Watts &

Hanna 2004). In astrophysical plasmas, the typical frequency of MHD

waves is much lower than the collisional frequencies between

species. In this case, the single fluid approach is usually adopted

and has been applied to wave damping in the solar atmosphere (De Pontieu et al. 2001; Khodachenko et al. 2004; Leake et al. 2005).

In the case of solar prominences, Forteza et al. (2007) derived the

full set of MHD equations for a partially ionized, single-fluid

plasma and applied them to study the time damping of linear,

adiabatic waves in an unbounded prominence medium. This study was

later extended to the non-adiabatic case by including thermal

conduction by neutrals and electrons, radiative losses, and heating

(Forteza et al. 2008). Because of the effect of neutrals, in

particular that of ion-neutral collisions, a generalized Ohm's law

has to be considered, which causes some additional terms to appear

in the resistive magnetic induction equation relative to the fully

ionized case. Among these additional terms, the dominant one in the

linear regime is the so-called ambipolar magnetic diffusion, which

enhances magnetic diffusion across magnetic field lines.

Furthermore, one of the interesting effects produced by the

consideration of partial ionisation and ion-neutral collisions is

that Alfvén waves can be damped, which cannot be obtained by means

of thermal mechanisms, and Singh & Krishnan (2010) studied the time

damping of Alfvén-like waves in a partially ionised plasma

representing a particular model of the solar atmosphere. For

bounded media, Soler et al. (2009c) applied this formalism to the

study of the time damping of fast, Alfvén, and slow waves in a

partially ionised filament thread modeled as a cylinder, and Soler

et al. (2009d) used a cylindrical filament thread, having an

inhomogeneous transition layer between prominence and coronal

material, to study the influence of partial ionisation on the time

damping of fast kink waves caused by resonant absorption in the

inhomogeneous layer.

helium. They constitute partially ionised plasmas since

hydrogen lines are observed (Labrosse et al. 2010). The exact

ionisation degree of prominences is unknown and the ratio of

electron density to neutral hydrogen density seems to be in the

interval 0.1-10 (Patsourakos & Vial 2002). From a

theoretical point of view, partial ionisation was considered by

Mercier and Heyvaerts (1977) when they studied the difusion of

neutral atoms by gravity. Gilbert et al. (2002) studied the

diffusion of neutral atoms in a partially ionized prominence plasma,

concluding that the loss timescale is much longer for hydrogen than

for helium. Gilbert et al. (2007) investigated the temporal and

spatial variations in the relative abundance of helium with respect

to hydrogen in a sample of filaments. They found that a majority of

filaments show a deficit of helium in the top part, while in the

bottom part there is an excess. This seems to be due to the shorter

loss timescale of neutral helium compared to that of neutral

hydrogen. The consideration of prominences as partially

ionised plasma is extremely important for the physics of

prominences, and the effects on MHD waves in prominences need to be

taken into account. From the theoretical point of view, and in the

framework of laboratory plasma physics, there is an extensive amount

of literature about wave propagation in a partially ionized

multifluid plasma (Watanabe 1961a,b; Tanenbaum 1961; Tanenbaum &

Mintzer 1962; Woods 1962; Kulsrud & Pearce 1969; Watts &

Hanna 2004). In astrophysical plasmas, the typical frequency of MHD

waves is much lower than the collisional frequencies between

species. In this case, the single fluid approach is usually adopted

and has been applied to wave damping in the solar atmosphere (De Pontieu et al. 2001; Khodachenko et al. 2004; Leake et al. 2005).

In the case of solar prominences, Forteza et al. (2007) derived the

full set of MHD equations for a partially ionized, single-fluid

plasma and applied them to study the time damping of linear,

adiabatic waves in an unbounded prominence medium. This study was

later extended to the non-adiabatic case by including thermal

conduction by neutrals and electrons, radiative losses, and heating

(Forteza et al. 2008). Because of the effect of neutrals, in

particular that of ion-neutral collisions, a generalized Ohm's law

has to be considered, which causes some additional terms to appear

in the resistive magnetic induction equation relative to the fully

ionized case. Among these additional terms, the dominant one in the

linear regime is the so-called ambipolar magnetic diffusion, which

enhances magnetic diffusion across magnetic field lines.

Furthermore, one of the interesting effects produced by the

consideration of partial ionisation and ion-neutral collisions is

that Alfvén waves can be damped, which cannot be obtained by means

of thermal mechanisms, and Singh & Krishnan (2010) studied the time

damping of Alfvén-like waves in a partially ionised plasma

representing a particular model of the solar atmosphere. For

bounded media, Soler et al. (2009c) applied this formalism to the

study of the time damping of fast, Alfvén, and slow waves in a

partially ionised filament thread modeled as a cylinder, and Soler

et al. (2009d) used a cylindrical filament thread, having an

inhomogeneous transition layer between prominence and coronal

material, to study the influence of partial ionisation on the time

damping of fast kink waves caused by resonant absorption in the

inhomogeneous layer.

To our knowledge, no study of the spatial damping of MHD waves in a partially ionised plasma has been performed. Therefore, since solar prominences are partially ionised plasmas in which material flows and oscillations are present and these oscillations are commonly interpreted in terms of MHD waves, our main aim here is to explore the theoretical and observational effects associated with the spatial damping of non-adiabatic MHD waves in an unbounded and partially ionised plasma, with prominence-like physical conditions, when a background flow is present. The layout of the paper is as follows. In Sect. 2, the equilibrium model and some theoretical considerations are presented; in Sect. 3, the spatial damping of Alfvén waves is studied; in Sect. 4, we consider the spatial damping of magnetoacoustic waves; finally, in Sect. 5, we present our conclusions.

2 Model and methods

2.1 Equilibrium properties

As a background model, we use a homogeneous unbounded medium threaded

by a uniform magnetic field along the x-direction, and with a

field-aligned background flow. The equilibrium magnitudes of the

medium are given by

where B0 and v0 are constants, and the effect of gravity has been ignored. Since we consider a medium with physical properties akin to those of a solar prominence, the density is

2.2 Basic and linearised equations

The derivation of the single-fluid MHD equations for a partially

ionised hydrogen plasma can be found in Forteza et al. (2007). These equations were later modified to include non-adiabatic processes in

the energy equation (Forteza et al. 2008), and the physical meaning

of all the terms and quantities used in the following can be found

in those papers. When a background flow is considered, the single

fluid basic equations for the study of non-adiabatic MHD waves in a

partially ionised plasma originate from Forteza et al. (2007, 2008) and Carbonell et al. (2009). The most important difference with

respect to the non-adiabatic case without a background flow is that

instead of the operator

![]() ,

we have

,

we have

![]() in the MHD

equations (Goedbloed & Poedts 2004).

Before proceeding, some remarks are in order. We consider a partially

ionised hydrogen plasma characterized by a plasma density,

in the MHD

equations (Goedbloed & Poedts 2004).

Before proceeding, some remarks are in order. We consider a partially

ionised hydrogen plasma characterized by a plasma density,

![]() ,

temperature, T0, and number densities of neutrals,

,

temperature, T0, and number densities of neutrals, ![]() ,

ions,

,

ions, ![]() ,

and electrons

,

and electrons ![]() ,

with

,

with

![]() .

Thus, the gas pressure is

.

Thus, the gas pressure is

![]() ,

where

,

where ![]() is Boltzmann's constant. The relative densities of neutrals,

is Boltzmann's constant. The relative densities of neutrals,

![]() ,

and ions,

,

and ions,

![]() ,

are given by

,

are given by

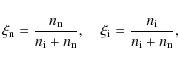

|

(1) |

where we have neglected the contribution of electrons. We can now define a ionization fraction,

|

(2) |

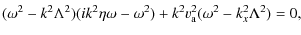

and the quantity

|

(3) |

where

- (1)

- A fully ionised ideal plasma (FIIP), where

,

,

;

;

- (2)

- A fully ionised resistive plasma (FIRP), where

,

,

and

and  ;

;

- (3)

- A partially ionised plasma (PIP), where

,

,

and

and

.

.

To obtain the dispersion relation for linear MHD waves, we next

consider small perturbations from equilibrium of the form

and linearise the single fluid basic equations. Since the medium is unbounded, we perform a Fourier analysis in terms of plane waves and assume that perturbations behave as

| (4) |

and with no loss of generality, we choose the z-axis so that the wavevector

After the Fourier analysis, we obtain the linearised scalar equations

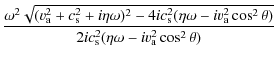

2.3 Dispersion relation for Alfvén waves

Equations (8) and (12) are decoupled

from the remainder and from them we can obtain a dispersion relation

for Alfvén waves in a partially ionised plasma with a background

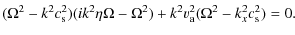

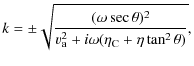

flow, which is,

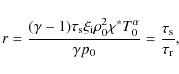

where

where

which was introduced by Forteza et al. (2008). In the case of a fully ionised ideal plasma without a background flow, Eq. (16) reduces to the well known expression for Alfvén waves.

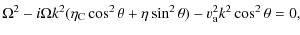

2.4 Dispersion relation for magnetoacoustic waves

From the remaining linearised equations, assumimg that the

determinant of the algebraic system is zero, we obtain our general

dispersion relation for thermal and magnetoacoustic waves in

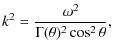

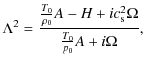

presence of a background flow, which is given by

where

where A and H, including the effects of optically thin radiative losses, thermal conduction by electrons and neutrals, and a constant heating per unit volume, are defined in Forteza et al. (2008). When Eq. (19) is expanded, it becomes a seventh degree polynomial in the wavenumber k. By setting the appropriate values to the corresponding quantities, the dispersion relation (19) is consistent with the case of an adiabatic and partially ionised plasma without flow (Forteza et al. 2007), the case of a non-adiabatic and partially ionised plasma without flow (Forteza et al. 2008) and the case of a non-adiabatic, fully ionised plasma with a background flow (Carbonell et al. 2009).

3 Spatial damping of Alfvén waves in a partially ionised plasma

Since we are interested in the spatial damping of MHD waves, we

consider the frequency, ![]() ,

to be real and seek for complex

solutions of the wavenumber k expressed as

,

to be real and seek for complex

solutions of the wavenumber k expressed as

![]() .

The wavelength of the waves is given by

.

The wavelength of the waves is given by

![]() ,

the damping length by

,

the damping length by

![]() ,

the damping length per wavelength is

,

the damping length per wavelength is

![]() ,

and, in general, we consider a

propagation angle

,

and, in general, we consider a

propagation angle

![]()

3.1 Spatial damping of Alfvén waves without background flow

In this case, our governing dispersion relation is given by

Eq. (17) and the wavenumbers are

|

(21) |

representing two Alfvén waves propagating in opposite directions. The real part (

while the imaginary part (

Figure 1 (left panels) shows a plot of the damping length, wavelength, and the ratio of the damping length to wavelength versus the period for Alfvén waves. The plots have been made for four different ionisation fractions and the shaded region corresponds to the interval of observed periods in prominence oscillations. When a period within the shaded region is considered, we observe that the damping length decreases substantially when the amount of neutrals in the plasma increases. Then, when ion-neutral collisions are present the spatial damping of Alfvén waves is enhanced for periods longer than 1 s. We can also observe that for a FIRP the behaviour of the damping length, wavelength and their ratio versus period is linear, except for periods below 10-6 s. However, when a PIP is considered, a deviation from the linear behaviour appears for periods below 1 s. This is because of the joint effect of the terms including frequency and resistivities in the real

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=3.8cm,clip]{13024fg1.eps}\includegraphics[width=3.8cm,clip]{13024fg2.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13024-09/Timg99.png)

|

Figure 1:

Left panels: damping length, wavelength, and ratio of the damping length to the wavelength versus the period

for Alfvén waves in a FIRP (solid) and in PIP with

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

3.2 Spatial damping of Alfvén waves with background flow

Our dispersion relation is given by Eq. (16), which

once expanded becomes a cubic polynomial in the wavenumber k, such as

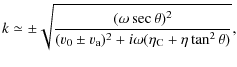

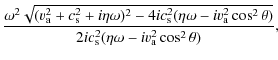

With respect to the case without flow, the increase in the degree of the dispersion relation is produced by the joint presence of flow and resistivities. In this case, we obtain three propagating Alfvén waves; therefore, Fig. 1 (right panels) shows the numerical solution of the dispersion relation given by Eq. (24) for the three Alfvén waves in a partially ionised plasma with a background flow. For all the interval of periods considered, a strongly damped third Alfvén wave appears, while in contrast, as in Sect. 3.1, the other two Alfvén waves are very efficiently damped for periods below 1 s. However, within the interval of periods typically observed in prominence oscillations, these waves are only efficiently attenuated when almost neutral plasmas are considered. Furthermore, approximations for the different wavenumbers corresponding to two of the expected Alfvén waves can be calculated to be

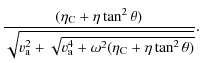

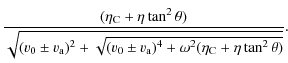

whose real part (

| |

![$\displaystyle \frac{ \sqrt{(v_{\rm0} \pm v_{\rm a})^{2}+\sqrt{(v_{\rm0} \pm v_{...

... \pm v_{\rm a})^{4} + \omega^{2} (\eta_{\rm C} +\eta \tan ^{2} \theta)\right]}}$](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13024-09/img106.png)

|

||

| (26) |

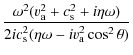

while its imaginary part (

| |

![$\displaystyle \frac{-\omega^{2} \sec \theta}{\sqrt{2 \left[(v_{\rm0} \pm v_{\rm a})^{4} + \omega^{2}

(\eta_{\rm C} +\eta \tan ^{2} \theta)\right]}}$](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13024-09/img108.png)

|

||

|

(27) |

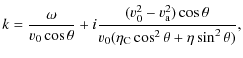

From the above expressions, if we consider a FIIP we recover the dispersion relation for Alfvén waves with a background flow (Carbonell et al. 2009), and if we remove the flow, the well-known dispersion relation for Alfvén waves is recovered. Since the flow speed is much lower than the Alfvén speed, the effect of the flow on the real and imaginary parts of the wavenumber is very small and, the wavelengths and damping lengths are then similar to those in Sect. 3.1. The third remaining wavenumber of Eq. (24) can be approximated by

corresponding to the third Alfvén wave. All the above analytical approximations display excellent agreement with the numerical results, and the presence of the third Alfvén wave, given by Eq. (28), fully depends on the join presence of a flow and resistivities since, otherwise, the dispersion relation given by Eq. (24) would be quadratic. For an external observer to the flowing plasma, this additional wave could be detectable, although its strong spatial damping would make its detection very difficult. For an observer linked to the flow inertial rest frame, only the two usual Alfvén waves, modified by resistivities, would be detected.

4 Spatial damping of magnetoacoustic waves in a partially ionised plasma

Our general dispersion relation for non-adiabatic magnetoacoustic waves in a background flow is given by Eq. (19). Because of the complexity of this dispersion relation and to help us to understand our results, we divided our study into a sequence of four different cases with dispersion relations of increasing complexity. In the first two cases, the behaviour of adiabatic magnetoacoustic waves in a non-flowing (Sect. 4.1) and flowing plasma (Sect. 4.2) is considered; in the last two cases, the behaviour of non-adiabatic waves in a non-flowing (Sect. 4.3) and flowing plasma (Sect. 4.4) is studied.

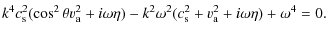

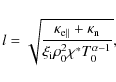

4.1 Adiabatic magnetoacoustic waves without background flow

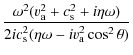

Setting A = H = 0 in Eq. (20),

![]() in

Eq. (5), and substituting into Eq. (19), we

obtain the dispersion relation for adiabatic magnetoacoustic waves

in a PIP without a background flow, which is

in

Eq. (5), and substituting into Eq. (19), we

obtain the dispersion relation for adiabatic magnetoacoustic waves

in a PIP without a background flow, which is

as previously found by Forteza et al. (2007)

4.1.1 Fully ionised resistive plasma

Imposing FIRP conditions from Sect. 2.2, the dispersion relation given by Eq. (30) simplifies to

which once expanded gives a fourth degree polynomial in the wavenumber k

Furthermore, when only longitudinal propagation is allowed (

producing two undamped slow waves with a dispersion relation given by

and since for longitudinal propagation, fast waves become Alfvén waves, we obtain two Alfvén waves, damped by resistivity, whose dispersion relation is

For these Alfvén waves, the real

| |

= |

|

|

|

(34) |

and

| |

= |

|

|

|

(35) |

where

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=4cm,clip]{13024fg3.eps}\includegraphics[width=4cm,clip]{13024fg4.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13024-09/Timg130.png)

|

Figure 2:

Damping length, wavelength, and ratio of the damping length to the wavelength versus period for the adiabatic fast ( left panels) and slow ( right panels) waves in a FIIP (solid), a FIRP

(dashed) and a PIP with

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

4.1.2 Partially ionised plasma

The dispersion relation is given by Eq. (30), and considering

only longitudinal propagation we obtain

which could suggest that the consideration of longitudinal propagation in either a FIRP or a PIP leads to the same dispersion relation. However, there is an important difference: while for FIRP both resistivities have the same numerical value, for PIP the numerical value of the Cowling's resistivity is much greater than that of the Spitzer's resistivity. Furthermore, for longitudinal propagation the slow waves are not influenced by Cowling's resistivity. Once expanded, Eq. (36) gives the following fourth degree polynomial in the wavenumber k

After solving this biquadratic dispersion relation, we obtain

|

(38) | |

|

(39) |

with

| A | = | ||

| B | = | ||

| C | = |

and the wavenumbers are,

|

(40) | |

|

(41) |

Figure 2 displays the behaviour of damping length, wavelength, and the ratio of damping length to wavelength versus period for fast and slow waves in a PIP, respectively. The damping length of both slow and fast waves is severely influenced by ion-neutral collisions, exhibiting a strong dependence on period for periods longer than 1 s, while for shorter periods the dependence becomes weaker. This figure also shows that with respect to a FIIP the wavelength of the fast waves is affected slightly by the partial ionisation, deviating from the linear behaviour for periods below 1 s, while the wavelength of slow waves is not affected at all. Within the interval of observed periods in prominence oscillations, when ionisation decreases the ratio of the damping length to the wavelength also decreases for both waves and the spatial damping becomes more efficient. The maximum efficiency of the spatial damping for fast waves is attained for periods below 1 s, while for slow waves the maximum of efficiency is attained at a period that depends on the ionisation fraction. The location of this maximum moves towards long periods when the ionisation of the plasma decreases, but when almost neutral plasmas are considered it is still located at a period slightly longer than 1 s, which is beyond the region of interest. Finally, comparing Figs. 1 and 2 it becomes obvious that the behaviour of Alfvén and fast waves is quite similar.

4.2 Adiabatic magnetoacoustic waves with background flow

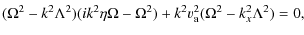

Setting A = H = 0 in Eq. (20) and substituting this into Eq. (19), we obtain the dispersion relation for adiabatic magnetoacoustic waves in a PIP with a background flow, which is

4.2.1 Fully ionised resistive plasma

Considering FIRP conditions from Sect. 2.2, the dispersion relation given by Eq. (42) becomes,

The dispersion relation is a fifth degree polynomial of the wavenumber k, and we therefore expect two slow waves and two fast waves that, for the flow speed considered, propagate in opposite directions, plus an additional wave. When only longitudinal propagation is considered, the above dispersion relation becomes

and slow waves are decoupled from fast waves propagating undamped, while fast waves are damped by resistivity. The wavenumbers corresponding to the undamped slow waves are given by

| (45) |

For the fast waves, which become Alfvén waves because of longitudinal propagation, the corresponding dispersion relation, given by the second factor in Eq. (44), is equivalent to Eq. (24) when

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=4cm,clip]{13024fg5.eps}\includegraphics[width=4cm,clip]{13024fg6.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13024-09/Timg148.png)

|

Figure 3:

Damping length, wavelength, and ratio of the damping length to the wavelength versus period for the adiabatic fast ( left panels) and slow ( right panels) waves in a FIIP (solid) and in a PIP with

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

4.2.2 Partially ionised plasma

Our dispersion relation is given by Eq. (42), which is a fifth degree polynomial in k, and when longitudinal propagation is considered we recover the results of Sect. 4.2.1 with slight differences due to the different numerical value of Cowling's resistivity adopted. As shown in Fig. 3, at periods longer than 0.1 s, the damping lengths of both slow and fast waves increase linearly with period. However, for periods below 0.1 s the damping length slowly decreases in the case of fast waves and becomes constant for slow waves. Furthermore, the wavelength of fast waves for periods below 0.1 s increases relatively to the FIRP case, while the wavelengths corresponding to slow waves are only slightly modified. For the ratio of the damping length to the wavelength, the unfolding in wavelength caused by the flow and the change in the damping length due to the partial ionisation produces fast waves that are far more efficiently attenuated than in a FIRP, for any period, but especially at periods below 0.1 s. In contrast the peak of maximum efficiency for slow waves is displaced towards long periods when ionisation decreases, and for almost neutral plasmas would approach the region of periods usually observed in prominence oscillations. The behaviour of the remaining third fast wave is again very similar to that found for the third Alfvén wave discussed in Sect. 3.2.

In the absence of flow, the dispersion relation given by Eq. (43) becomes a fourth degree polynomial in k and the third fast wave disappears. As happens for Alfvén waves with a background flow, this third fast wave is produced by the joint action of flow and resistivity, since when a FIIP with a background flow is considered, the dispersion relation also becomes a fourth degree polynomial in k and the third fast wave is absent.

4.3 Non-adiabatic magnetoacoustic waves in a prominence plasma without background flow

Setting

![]() in Eq. (5) and substituting this

into Eq. (19), we obtain the dispersion relation for

non-adiabatic magnetoacoustic waves in a PIP without a background

flow, which is

in Eq. (5) and substituting this

into Eq. (19), we obtain the dispersion relation for

non-adiabatic magnetoacoustic waves in a PIP without a background

flow, which is

4.3.1 Fully ionised resistive plasma

After imposing the conditions corresponding to a FIRP, the following dispersion relation, a sixth degree polynomial in the

wavenumber k, is obtained

which describes coupled fast, slow, and thermal waves. When only longitudinal propagation is allowed, the above dispersion relation becomes

As in Sect. 3.1, we then obtain two decoupled Alfvén waves, damped by resistivity, whose dispersion relation is given by

|

(49) |

and another dispersion relation

which is a fourth degree polynomial in k describing coupled propagating thermal and slow waves, damped only by thermal effects. The dispersion relation given by Eq. (47) was solved numerically, and Figs. 4 and 5 present the damping length, wavelength, and ratio of the damping length to the wavelength versus period for the fast, slow, and thermal waves. Starting with Fig. 4, we only considered an interval of periods between 10-2 and 107 s, since for periods shorter than 10-2 s, much shorter than those of interest, the curves become very entangled. When an FIIP is considered, the spatial damping of the fast wave is governed by radiative losses and thermal conduction (Carbonell et al. 2006) in the interval of periods from 10-2 to 107 s. However, in a FIRP we observe a slight change in the damping length of fast waves around a period of 1 s. This change tells us that the dominance of thermal conduction appears slightly earlier in time than for the ideal case. For the ratio of the damping length to the wavelength, we observe that the efficiency of the damping for fast waves is higher than for a FIIP, for periods below 1 s. For slow waves, no differences appear between the behaviours of FIIP and FIRP. The behaviour of thermal waves (Fig. 5) is exactly the same in FIIP and FIRP.

4.3.2 Partially ionised plasma

In this case, our dispersion relation is given by Eq. (46)

and when only longitudinal propagation is allowed the expression is

similar to that of Sect. 4.3.1, although the numerical value of the

Cowling's resistivity is different and the results for fast waves

would differ. When oblique propagation is considered,

Eq. (46) is solved numerically and a strong distortion of

the damping length and wavelength curves corresponding to fast waves

(Fig. 4, left panels) appears. The changes affect the

radiative plateau, between periods 103 and 10-2 s, and

partial ionisation decreases the damping length of fast waves in

this region. For slow waves (Fig. 4, right panels), a

similar behaviour is found in the same regions, although the

distortion is not so important since a very short radiative plateau,

between 102 and 103 s, remains, together with a region,

between 1 and 102 s, where thermal conduction is dominant.

Compared to a FIRP, the ratio

![]() for fast waves

decreases substantially for periods below 103 s, although for

the periods of interest in prominences, this ratio remains very

large. For slow waves, partial ionisation causes the ratio

for fast waves

decreases substantially for periods below 103 s, although for

the periods of interest in prominences, this ratio remains very

large. For slow waves, partial ionisation causes the ratio

![]() to reach a maximum efficiency of

to reach a maximum efficiency of ![]() 1 for

periods similar to those involved in prominence oscillations, and

this maximum is displaced towards longer periods when ionisation is

decreased. The changes in the wavelengths of slow and fast waves

are similar to those shown in the adiabatic case (Sect. 4.1.2).

In the case of thermal waves (Fig. 5), partial ionisation

increases both the damping length and wavelength of these waves,

although the behaviour of the ratio

1 for

periods similar to those involved in prominence oscillations, and

this maximum is displaced towards longer periods when ionisation is

decreased. The changes in the wavelengths of slow and fast waves

are similar to those shown in the adiabatic case (Sect. 4.1.2).

In the case of thermal waves (Fig. 5), partial ionisation

increases both the damping length and wavelength of these waves,

although the behaviour of the ratio

![]() is

similar to previous cases. Since a thermal wave is always strongly

damped, which makes its detection very difficult, in the following

we avoid additional comments on it.

is

similar to previous cases. Since a thermal wave is always strongly

damped, which makes its detection very difficult, in the following

we avoid additional comments on it.

To understand the effects of radiation and thermal conduction by neutrals and electrons, in Fig. 6 we represent, for fast and slow waves, the same quantities but with optically thin radiation and heating removed, i.e., only thermal conduction is at work, and we can observe that the most efficient damping for both waves occurs for partially ionised plasmas, which suggests that the inclusion of the isotropic thermal conduction due to neutrals plays a very important role for all the periods considered. However, we must take into account that when the ionisation fraction decreases, radiation also decreases and that, because of neutrals, thermal conduction is favoured, which makes it difficult to establish meaningful comparisons between plasmas with different degrees of ionisation.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=4cm,clip]{13024fg7.eps}\includegraphics[width=4cm,clip]{13024fg8.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13024-09/Timg156.png)

|

Figure 4:

Damping length, wavelength, and ratio of the damping length to the wavelength versus period for the non-adiabatic fast ( left panels), slow ( right panels) waves in a FIIP (solid), a FIRP

(dashed), and a PIP with

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{13024fg9.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13024-09/Timg157.png)

|

Figure 5: Damping length,

wavelength, and ratio of the damping length to the wavelength versus

period for the non-adiabatic thermal wave in a FIIP (solid), a FIRP

(dashed), and a PIP with

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=4.3cm,clip]{13024fg10.eps}\includegraphics[width=4.3cm,clip]{13024fg11.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13024-09/Timg158.png)

|

Figure 6:

Damping length, wavelength, and ratio of the damping length to the wavelength versus period for the non-adiabatic fast ( left panels), slow ( right panels) waves, without radiation, in a FIIP (dashed), a FIRP (dotted), and a PIP with

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

In Fig. 7, we plot the behaviour of fast and slow waves, when thermal conduction has been removed, i.e., only radiation and heating remain. When thermal conduction by electrons and neutrals is removed, the behaviour of fast waves in a FIIP and in FIRP is similar and, within the interval of periods of interest, the behaviour of the different quantities corresponding to the different types of plasma is the same. However, when periods below 100 s are considered, FIIP and FIRP are strongly affected by the lack of thermal conduction. For slow waves, a similar behaviour appears and the most important conclusion after comparing Figs. 6 and 7, within the interval of periods of interest, is that very efficient damping is caused by optically thin radiation.

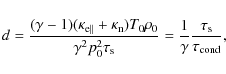

On the other hand, when non-adiabatic magnetoacoustic waves are

considered, the importance of radiation and thermal conduction can

also be quantified in terms of two dimensionless parameters (De Moortel & Hood 2004), namely, the thermal ratio, which modified

for the case of partial ionisation becomes

|

(51) |

which is

|

(52) |

which is the ratio of the sound travel time to the radiation timescale

where

4.4 Non-adiabatic magnetoacoustic waves in a prominence plasma with background flow

4.4.1 Fully ionised ideal plasma

Setting in Eq. (19) conditions corresponding to FIIP, we obtain

which is a sixth degree polynomial in the wavenumber k. When only longitudinal propagation is allowed, we obtain two undamped Alfvén waves given by

|

(55) |

whose solutions for the wavenumbers are

| (56) |

as in Carbonell et al. (2009), while the dispersion relation

| (57) |

describes coupled slow and thermal waves modified by the flow and damped by thermal effects. In the case of oblique propagation, Eq. (54) is solved numerically and the behaviour of fast and slow waves is shown in Fig. 8. When a flow is present the unfolding of wavelengths and damping lengths appears. Since the considered flow speed is much lower than Alfvén speed, the separation of the curves corresponding to the fast wave is very small, while, since flow speed and sound speed are comparable, the curves corresponding to slow waves separate substantially. This effect strongly affects the behaviour of the damping length versus wavelength for slow waves, since one of them has a very efficient spatial damping for periods observed in prominence oscillations. In the case considered in this section, the damping of fast and slow waves is strictly due to thermal effects.

4.4.2 Fully ionised resistive plasma

In this case, considering FIRP conditions, the dispersion relation becomes

which is a seventh degree polynomial in the wavenumber k. Considering only longitudinal propagation, again we find coupled slow and thermal waves modified by the flow and damped by thermal effects, and three Alfvén waves given by the dispersion relation (24), with

4.4.3 Partially ionised plasma

The dispersion relation is now given by Eq. (19) and

Fig. 9 displays the behaviour of the damping length,

wavelength, and ratio of damping length to wavelength for fast and

slow waves. The most interesting results are those related to the

ratio

![]() .

For fast waves, this ratio decreases

with the period becoming small for periods below 10-2 s, while

for one of the slow waves, the ratio becomes very small for periods typically observed in prominence oscillations.

When ionisation

is decreased, slight changes in the above described behaviour occur,

the most important being the displacement towards longer periods of

the peak for the most efficient damping corresponding to slow waves.

As pointed out before, a third fast wave is, again, produced by the

joint action of flow and resistivity. In the absence of flow or

resistivity, the dispersion relation would become a sixth order

polynomial of the wavenumber and this wave would be absent.

.

For fast waves, this ratio decreases

with the period becoming small for periods below 10-2 s, while

for one of the slow waves, the ratio becomes very small for periods typically observed in prominence oscillations.

When ionisation

is decreased, slight changes in the above described behaviour occur,

the most important being the displacement towards longer periods of

the peak for the most efficient damping corresponding to slow waves.

As pointed out before, a third fast wave is, again, produced by the

joint action of flow and resistivity. In the absence of flow or

resistivity, the dispersion relation would become a sixth order

polynomial of the wavenumber and this wave would be absent.

5 Conclusions

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=4.1cm,clip]{13024fg12.eps}\includegraphics[width=4cm,clip]{13024fg13.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13024-09/Timg176.png)

|

Figure 7:

Damping length, wavelength, and ratio of the damping length to the wavelength versus period for the non-adiabatic fast ( left panels), slow ( right panels) waves in a PIP (

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=4cm,clip]{13024fg14.eps}\includegraphics[width=4cm,clip]{13024fg15.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13024-09/Timg177.png)

|

Figure 8: Damping length, wavelength, and ratio of the damping length to the wavelength versus period for the non-adiabatic fast (left panels), slow (right panels) waves in a FIIP (solid), and in a FIRP (dashed). The flow speed is 10 km s-1. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=4.05cm,clip]{13024fg16.eps}\includegraphics[width=4cm,clip]{13024fg17.eps} \end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13024-09/Timg178.png)

|

Figure 9:

Damping length, wavelength, and ratio of the damping length to the wavelength versus period for the non-adiabatic fast (left panels), slow (right panels) waves in a PIP with

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

Quiescent solar prominences and filaments are partially ionised plasmas and some of their main characteristics are material flows and oscillations. While the time damping of these oscillations has been thoroughly studied, their spatial damping has not been in detail. Interpreting the observed oscillations in terms of MHD waves, we have analysed the spatial damping of Alfvén and non-adiabatic magnetoacoustic waves in a flowing partially ionised prominence plasma. Several different cases, with dispersion relations of increasing complexity, have been considered, and we summarize our main conclusions below.

As is well known, Alfvén waves are difficult to damp because they are insensitive to non-adiabatic effects. However, when Alfvén waves in a partially ionised plasma are considered, they can be spatially damped and analytical expressions describing their spatial damping can be obtained. When the ionisation decreases, the damping length of these waves also decreases and the efficiency of their spatial damping in the range of periods of interest is improved, although the most efficient damping is attained for periods below 1 s. A new feature is that when a flow is present a new third Alfvén wave, strongly attenuated, appears. This wave depends on the joint action of flow and resistivities, since in the absence of a flow, or for a FIIP, the dispersion relation becomes quadratic producing the two well-known Alfvén waves. Furthermore, this third wave could only be detected by an observer not moving with the flow.

When adiabatic magnetoacoustic waves are considered and the effect of partial ionisation is taken into account, some new features appear. When a FIRP is considered and only longitudinal propagation is allowed, slow waves are decoupled from fast waves, propagating undamped, while fast waves propagate with a modified Alfvén speed and are damped by resistivity. When a PIP plasma is studied and only longitudinal propagation is allowed, the same occurs but then the numerical value of Cowling's resistivity is greater than before, enhancing the damping. The behaviour of slow waves is then only influenced by partial ionisation when oblique propagation is allowed. Furthermore, when a PIP is considered the behaviour of fast waves is very similar to that of Alfvén waves and the damping becomes very efficient for periods below 1 s, while for slow waves the peak denoting the most efficient damping moves towards higher periods as the plasma ionisation decreases. When a flow is considered in the adiabatic case, the main difference is the unfolding of the damping-length, wavelength and damping-length to wavelength curves, and the apparition of a third fast wave, strongly damped, caused by the join presence of flow and resistivities.

For non-adiabatic magnetoacoustic waves, when partial ionisation

is

present the behaviour of fast, slow, and thermal waves is strongly

modified. Comparing with non-adiabatic fast waves in a FIIP, which

are damped by electronic thermal conduction and radiation, the

damping length of a fast wave in a PIP is strongly diminished by

neutrals thermal conduction for periods between 0.01 and 100 s,

and, at the same time, the radiative plateau present in FIIP and

FIRP disappears. The behaviour of slow waves is not so strongly

modified as for fast waves, although thermal conduction by neutrals

also diminishes the damping length for periods below 10 s, and a

short radiative plateau remains for periods between 10 and

1000 s. Finally, thermal waves are only slightly modified,

although the

effect of partial ionisation is to increase the damping length of

these waves, the converse of what happens for the other waves. When

a background flow is included, a new third fast wave appears, which

is again, due to the joint action of flow and resistivities. As we

already know, wavelengths and damping lengths are modified by the

flow, and since, for slow waves, sound speed and observed flow

speeds are comparable, the change in wavelength and

damping length are important leading to an improvement in the

efficiency of the damping. The maximum of efficiency is also

displaced towards long periods when the ionisation decreases, and

for ionisation fractions from 0.8 to 0.95, it is clearly

located

within the range of periods typically observed in prominence

oscillations with a value of

![]() smaller than 1. This means that for a typical period of 103 s, the

damping length would be between 102 and 103 km, the

wavelength around 103 km and, as a consequence, in a distance

smaller than a wavelength the slow wave would be strongly

attenuated. On the other hand, during our calculations, we have

found that the different heating mechanisms usually considered

(Carbonell et al. 2004) do not affect the results.

smaller than 1. This means that for a typical period of 103 s, the

damping length would be between 102 and 103 km, the

wavelength around 103 km and, as a consequence, in a distance

smaller than a wavelength the slow wave would be strongly

attenuated. On the other hand, during our calculations, we have

found that the different heating mechanisms usually considered

(Carbonell et al. 2004) do not affect the results.

In conclusion, the joint effect of non-adiabaticity, flows, and partial ionisation allows slow waves to damp in an efficient way within the interval of periods typically observed in prominences. Thermal waves are attenuated very efficiently within the interval of interest but their observational detection is probably very difficult, and fast waves are very unefficiently attenuated within the considered interval. Furthermore, since Alfvén and fast waves display similar behaviours, the observational differentiation between them should be based on the detection of their associated perturbations. We also note that the new fast and Alfvén waves are only detectable in a reference system external to the flow, although their short damping length should make their detection very difficult. As we have seen, even in the most simple case of an unbounded medium threaded by a uniform magnetic field, the inclusion of non-adiabatic effects, partial ionisation, and flows complicates the study of the spatial damping of prominence oscillations because of the apparition of new waves and the difficulty in distinguishing between the different effects. From observations, this implies that because of the entanglement of the different effects, it is extremely difficult to properly interpret the observed oscillations in terms of MHD waves.

The present study represents a first step in investigating the behaviour of the spatial damping of MHD waves in partially ionised prominence plasmas. Forthcoming studies must focus on investigating the behaviour of this type of damping in threads, which seem to be the basic constituents of quiescent prominences.

AcknowledgementsThe authors acknowledge the financial support provided by MICINN and FEDER funds under grant AYA2006-07637. P. Forteza acknowledges a FPU fellowship from MECyT. Also, the Conselleria d'Economia, Hisenda i Innovació of the Government of the Balearic Islands is gratefully acknowledged for the funding provided under grant PCTIB2005GC3-03.

References

- Arregui, A., Terradas, J., Oliver, R., et al. 2008, ApJ, 682, L141 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, D., Erdélyi, R., Oliver, R., et al. 2007, Sol. Phys., 246, 3 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Berger, T. E., Shine, R. A., Slater, G. L., et al. 2008, ApJ, 676, L89 [Google Scholar]

- Braginskii, S. I. 1965, Rev. Plasma Phys., 1, 205 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Carbonell, M., Oliver, R., & Ballester, J. L. 2004, A&A, 415, 739 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Carbonell, M., Terradas, J., Oliver, R., et al. 2006, A&A, 460, 573 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Carbonell, M., Oliver, R., & Ballester, J. L. 2009, New A., 14, 277 [Google Scholar]

- De Moortel, I., Hood, A. W., Ireland, J., et al. 2002, Sol. Phys., 209, 89 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- De Moortel, I., & Hood, A. W. 2003, A&A, 408, 755 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- De Moortel, I., & Hood, A. W. 2004, A&A, 415, 705 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- De Pontieu, B., Martens, P. C. H., & Hudson, H. S. 2001, ApJ, 558, 859 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Forteza, P., Oliver, R., Ballester, J. L., et al. 2007, A&A, 461, 731 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Forteza, P., Oliver, R., & Ballester, J. L. 2008, A&A, 492, 223 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, H. R., Hansteen, V. H., & Holzer, T. E. 2002, A&A, 577, 464 [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, H., Kilper, G., & Alexander, D. 2007, ApJ, 671, 978 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Goedbloed, H., & Poedts, S. 2004, Principles of Magnetohydrodynamics (Cambridge University Press) [Google Scholar]

- Kulsrud, R., & Pearce, W. P. 1969, ApJ, 156, 445 [Google Scholar]

- Khodachenko, M. L., Arber, T. D., Rucker, H. O., et al. 2004, A&A, 422, 1073 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Labrosse, N., Heinzel, P., Vial, J. V., et al. 2010, Space Sci. Rev., 151, 243 [Google Scholar]

- Leake, J. E., Arber, T. D., & Khodachenko, M. L. 2005, A&A, 442, 1091 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y., Engvold, O., & Wiik, J. E. 2003, Sol. Phys., 216, 109 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y., Engvold, O., Rouppe van der Voort, L. H. M., et al. 2007, Sol. Phys., 246, 65 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mackay, D., Karpen, J., Ballester, J. L., Schmieder, B., & Aulanier, G. 2010, Space Sci. Rev. [Google Scholar]

- Mercier, C., & Heyvaerts, J. 1977, A&A, 61, 685 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto, T.J, Tsuneta, S., Berger, TE, et al. 2007, Sciences, 318, 1577 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, R. 2009, Space Sci. Rev., in press [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, R., & Ballester, J. L. 2002, Sol. Phys., 206, 45 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Patsourakos, S., & Vial, J.-C. 2002, Sol. Phys., 208, 253 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Singh, K. A. P. 2006, JApA, 27, 321 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Singh, K. A. P., Dwivedi, B. N., & Hasan, S. S. 2007, A&A, 473, 931 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Singh, K. A. P., & Krishan, V. 2010, New A., 15, 119 [Google Scholar]

- Soler, R., Oliver, R., & Ballester, J. L. 2008, ApJ, 684, 725 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Soler, R., Oliver, R., & Ballester, J. L. 2009a, ApJ, 693, 1601 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Soler, R., Oliver, R., & Ballester, J. L. 2009b, ApJ, 695, L166 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Soler, R., Oliver, R., & Ballester, J. L. 2009c, ApJ, 699, 1553 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Soler, R., Oliver, R., & Ballester, J. L. 2009d, ApJ, 707, 662 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Tanenbaum, B. S. 1961, Phys. Fluids, 4, 1262 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Tanenbaum, B. S., & Mintzer, D. 1962, Phys. Fluids, 5, 1226 [Google Scholar]

- Terradas, J., Molowny-Horas, R., Wiehr, E., et al. 2002, A&A, 393, 637 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Terradas, J., Carbonell, M., Oliver, R., et al. 2005, A&A, 434, 741 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, T. 1961a, Can. J. Phys., 39, 1044 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, T. 1961b, Can. J. Phys., 39, 1197 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Watts, C., & Hanna, J. 2004, Phys. Plasmas, 11, 1358 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Woods, L. C. 1962, J. Fluid Mechanics, 13, 570 [Google Scholar]

- Zirker, J. B., Engvold, O., & Martin, S. F. 1998, Nature, 434, 741 [Google Scholar]

All Figures

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=3.8cm,clip]{13024fg1.eps}\includegraphics[width=3.8cm,clip]{13024fg2.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13024-09/Timg99.png)

|

Figure 1:

Left panels: damping length, wavelength, and ratio of the damping length to the wavelength versus the period

for Alfvén waves in a FIRP (solid) and in PIP with

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=4cm,clip]{13024fg3.eps}\includegraphics[width=4cm,clip]{13024fg4.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13024-09/Timg130.png)

|

Figure 2:

Damping length, wavelength, and ratio of the damping length to the wavelength versus period for the adiabatic fast ( left panels) and slow ( right panels) waves in a FIIP (solid), a FIRP

(dashed) and a PIP with

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=4cm,clip]{13024fg5.eps}\includegraphics[width=4cm,clip]{13024fg6.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13024-09/Timg148.png)

|

Figure 3:

Damping length, wavelength, and ratio of the damping length to the wavelength versus period for the adiabatic fast ( left panels) and slow ( right panels) waves in a FIIP (solid) and in a PIP with

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=4cm,clip]{13024fg7.eps}\includegraphics[width=4cm,clip]{13024fg8.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13024-09/Timg156.png)

|

Figure 4:

Damping length, wavelength, and ratio of the damping length to the wavelength versus period for the non-adiabatic fast ( left panels), slow ( right panels) waves in a FIIP (solid), a FIRP

(dashed), and a PIP with

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{13024fg9.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13024-09/Timg157.png)

|

Figure 5: Damping length,

wavelength, and ratio of the damping length to the wavelength versus

period for the non-adiabatic thermal wave in a FIIP (solid), a FIRP

(dashed), and a PIP with

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=4.3cm,clip]{13024fg10.eps}\includegraphics[width=4.3cm,clip]{13024fg11.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13024-09/Timg158.png)

|

Figure 6:

Damping length, wavelength, and ratio of the damping length to the wavelength versus period for the non-adiabatic fast ( left panels), slow ( right panels) waves, without radiation, in a FIIP (dashed), a FIRP (dotted), and a PIP with

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=4.1cm,clip]{13024fg12.eps}\includegraphics[width=4cm,clip]{13024fg13.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13024-09/Timg176.png)

|

Figure 7:

Damping length, wavelength, and ratio of the damping length to the wavelength versus period for the non-adiabatic fast ( left panels), slow ( right panels) waves in a PIP (

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=4cm,clip]{13024fg14.eps}\includegraphics[width=4cm,clip]{13024fg15.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13024-09/Timg177.png)

|

Figure 8: Damping length, wavelength, and ratio of the damping length to the wavelength versus period for the non-adiabatic fast (left panels), slow (right panels) waves in a FIIP (solid), and in a FIRP (dashed). The flow speed is 10 km s-1. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=4.05cm,clip]{13024fg16.eps}\includegraphics[width=4cm,clip]{13024fg17.eps} \end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13024-09/Timg178.png)

|

Figure 9:

Damping length, wavelength, and ratio of the damping length to the wavelength versus period for the non-adiabatic fast (left panels), slow (right panels) waves in a PIP with

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

Copyright ESO 2010

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.

![$\displaystyle k_{\rm r} = \omega \sec \theta \frac{

\sqrt{v_{\rm a}^{2}+\sqrt{v...

...left[v_{\rm a}^{4} + \omega^{2} (\eta_{\rm C} +\eta \tan

^{2} \theta)\right]}},$](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13024-09/img88.png)

![$\displaystyle \frac{-\omega^{2} \sec \theta}{\sqrt{2 \left[v_{\rm a}^{4} + \omega^{2} (\eta_{\rm C} +\eta \tan

^{2} \theta)\right]}}$](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13024-09/img91.png)