| Issue |

A&A

Volume 513, April 2010

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A7 | |

| Number of page(s) | 14 | |

| Section | Astronomical instrumentation | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/200913467 | |

| Published online | 13 April 2010 | |

Probing high-redshift quasars with ALMA

I. Expected observables and potential number of sources

D. R. G. Schleicher1,2 - M. Spaans3 - R. S. Klessen4

1 - Leiden Observatory, Leiden University, PO Box 9513, 2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands

2 -

ESO, Karl-Schwarzschild-Strasse 2, 85748 Garching bei München, Germany

3 -

Kapteyn Astronomical Institute, University of Groningen, PO Box 800, 9700 AV, Groningen, The Netherlands

4

- Zentrum für Astronomie der Universität Heidelberg, Institut für

Theoretische Astrophysik, Albert-Ueberle-Str. 2, 69120 Heidelberg,

Germany

Received 14 October 2009 / Accepted 5 January 2010

Abstract

Aims. We explore how ALMA observations can probe

high-redshift galaxies in unprecedented detail. We discuss the main

observables that are excited by the large-scale starburst, and

formulate expectations for the chemistry and the fluxes in the center

of active galaxies, in which chemistry may be driven by the absorption

of X-rays. We estimate the expected number of sources at high redshift

in an ALMA deep field. As a specific example for the complex

interpretation of sub-mm line observations, we analyze the recently

detected z=6.42 quasar, for which a number of different line

fluxes is already available. We note that our diagnostics may also be

valuable for future observations in the local universe with space-borne

instruments like on SPICA or FIRI.

Methods. To estimate the observables from the starburst, we

check which emission from the starburst ring of the nearby

Seyfert 2 galaxy NGC 1068 falls into the ALMA bands if the

galaxy were placed at z=8. We estimate the sizes of the central

X-ray dominated region based on a semi-analytic model, and employ a

detailed 1D approach for the chemistry in X-ray irradiated molecular

clouds to evaluate the chemistry and the expected line emission under

these conditions. We make use of pre-existing chemistry calculations in

X-ray dominated regions to show the dependence of different line fluxes

on X-ray luminosity, cloud density and cloud column density. We use

theoretical models for the high-z black hole population and the local SMBH density to estimate the number of sources at higher redshift.

Results. We show that a number of different fine-structure lines

may be used to probe the starburst component of high-redshift quasars

in considerable detail, providing specific information on the structure

of these galaxies by several independent means. We show that the size

of the central X-ray dominated region is of the order of a few hundred

parsec, and we provide detailed predictions for the expected fluxes in

CO, [CII] and [OI]. While the latter fine-structure lines quickly

become optically thick and depend mostly on the strength of the X-ray

source, the rotational CO lines have a non-trivial dependence on

these parameters. We compare our models to XDRs observed in

NGC 1068 and APM 08279 and find that the observed emission

can indeed be explained with these models. Depending on the amount of

X-ray flux, the CO line intensities may rise continuously up to

the (17-16) transition. A measurement of such high-J lines allows one to distinguish observationally between XDRs and PDRs. For the recently observed z=6.42

quasar, we show that the collected fluxes cannot be interpreted in

terms of a single gas component. We find indications for the presence

of a dense warm component in active star forming regions and a

low-density component in more quiescent areas. Near z=6, an ALMA deep field may find roughly one source per arcmin2. At higher redshift, one likely has to rely on other surveys like JWST to find appropriate sources.

Key words: astrochemistry - galaxies: active - galaxies: high-redshift - galaxies: ISM - X-rays: ISM

1 Introduction

The recent detection of kpc-scale star-forming structures at z=6.42 through the detection of [CII] emission (Walter et al. 2009a) and emission in various rotational CO lines (Riechers et al. 2009a) confirms the importance of mm/sub-mm observations to infer gas distribution and dynamics in quasar host galaxies. Emission in CO and the continuum in high-redshift quasars have also been reported by Omont et al. (1996), Carilli et al. (2002), Walter et al. (2004), Klamer et al. (2005), Weiß et al. (2005), Maiolino et al. (2007), Walter et al. (2007), Weiß et al. (2007), Riechers et al. (2008b) and Riechers et al. (2008a).With the upcoming mm/sub-mm telescope ALMA![]() ,

it will be possible to probe such structures in even more detail, due

to its significantly improved sensitivity, angular and spectral

resolution. From a theoretical point of view, it is therefore

interesting to speculate what ALMA might observe in the center of such

host galaxies. Within the next ten years, we further expect the advent

of SPICA

,

it will be possible to probe such structures in even more detail, due

to its significantly improved sensitivity, angular and spectral

resolution. From a theoretical point of view, it is therefore

interesting to speculate what ALMA might observe in the center of such

host galaxies. Within the next ten years, we further expect the advent

of SPICA![]() and FIRI

and FIRI![]() ,

which will probe the universe in the mid- or far-IR regime,

respectively. These telescopes will be able to apply in the local

universe what we suggest as high-redshift diagnostics for ALMA.

,

which will probe the universe in the mid- or far-IR regime,

respectively. These telescopes will be able to apply in the local

universe what we suggest as high-redshift diagnostics for ALMA.

Before speculating what ALMA may see in the centers of

high-redshift galaxies, we turn our attention to the properties of

molecular clouds in the central molecular zone (CMZ) of the Milky Way.

Studies employing H3+ and CO lines indicate the presence of high-temperature (![]() K) and low-density (

K) and low-density (![]() cm-3) gas (Oka et al. 2005). NH3 observations by Nagayama et al. (2007)

confirm the presence of warm molecular clouds, with temperatures mostly

between 20-80 K. The presence of a 120 pc star-forming ring

was infered by CO observations, indicating typical densities of

10 3.5-4 cm-3 and kinetic temperatures of 20-35 K (Nagai et al. 2007).

These temperatures were derived under the conservative assumption of a

beam filling factor 1, while smaller filling factors would give rise to

higher temperatures.

cm-3) gas (Oka et al. 2005). NH3 observations by Nagayama et al. (2007)

confirm the presence of warm molecular clouds, with temperatures mostly

between 20-80 K. The presence of a 120 pc star-forming ring

was infered by CO observations, indicating typical densities of

10 3.5-4 cm-3 and kinetic temperatures of 20-35 K (Nagai et al. 2007).

These temperatures were derived under the conservative assumption of a

beam filling factor 1, while smaller filling factors would give rise to

higher temperatures.

In the centers of active galaxies, the supermassive black hole will emit radiation in a broad range of frequencies. Particularly interesting is the emission of X-rays, as those photons can penetrate molecular clouds even at high column densities. The resulting cloud temperatures range from a hundred K up to 1000 K (Meijerink et al. 2007; Meijerink & Spaans 2005; Maloney et al. 1996; Lepp & Dalgarno 1996). Such X-ray dominated regions have been reported for instance in NGC 1068 by Galliano et al. (2003). Due to the high ambient pressure, higher-density clouds may form due to the thermal instability (Wada & Norman 2007).

At high redshift, resolution of present-day telescopes is generally not sufficient to resolve the central regions of quasar host galaxies. Under exceptional circumstances, this is however possible. Indeed, highly excited high-J CO and HCN line emission was found in APM 08279+5255 by Weiß et al. (2007). As this galaxy is gravitationally lensed, it was possible to measure fluxes from the central X-ray dominated region that are usually beam-diluted. While the CO line fluxes usually rise up to the CO (5-4) transition and then decrease, they continue to rise in this system up to the CO (10-9) transition, providing clear evidence for the presence of warm gas in the central region. Similar results have also been obtained for the Cloverleaf quasar (Bradford et al. 2009).

Motivated by these results, we study in more detail the possibility to

probe high-redshift quasar host galaxies with ALMA, and in particular

their central regions. In Sect. 2,

we review the main heating mechanisms that may be present in

high-redshift quasars, and discuss their influence on the chemistry. In

Sect. 3, we give a brief summary

on the main PDR observables, which are already used to probe galaxies

at high redshift. As a specific example, we calculate the expected

fluxes for the Seyfert 2 galaxy NGC 1068 if it were located

at z=8. Our expectations for the central X-ray dominated regions (XDRs) are formulated in Sect. 4 based on detailed chemical models including ![]() 50 species

and several thousand reactions. Evidence for X-ray dominated regions at

different redshifts is reviewed and discussed in Sect. 5. On this basis, we assess the prospects for finding new sources in an ALMA deep field in Sect. 6. We conclude in Sect. 7.

In summary, this paper provides a basic set of predictions concerning

observations of high-redshift quasars with ALMA. In a companion paper,

we plan to provide diagnostics based on the observed line fluxes that

will allow one to infer physical properties such as the star formation

rate or the X-ray luminosity based on the observed line emission.

50 species

and several thousand reactions. Evidence for X-ray dominated regions at

different redshifts is reviewed and discussed in Sect. 5. On this basis, we assess the prospects for finding new sources in an ALMA deep field in Sect. 6. We conclude in Sect. 7.

In summary, this paper provides a basic set of predictions concerning

observations of high-redshift quasars with ALMA. In a companion paper,

we plan to provide diagnostics based on the observed line fluxes that

will allow one to infer physical properties such as the star formation

rate or the X-ray luminosity based on the observed line emission.

2 Chemistry in high-redshift quasars

Emission from molecular clouds in active galaxies can be excited by

a variety of different mechanisms. Mechanical feedback may be important

locally, in particular in the presence of shocks or outflows (Papadopoulos et al. 2008; Loenen et al. 2008).

In addition, there is radiation in a broad range of frequencies, both

from the starburst and the supermassive black hole. UV emission

generally gives rise to compact HII regions at temperatures of ![]() 104 K in which molecules are completely dissociated and emission is mostly by Lyman

104 K in which molecules are completely dissociated and emission is mostly by Lyman ![]() and various fine-structure lines. Such photons are however absorbed by

relatively small column densities, and stellar HII regions never become

larger than a few pc, considerably smaller than the scales of interest

here.

and various fine-structure lines. Such photons are however absorbed by

relatively small column densities, and stellar HII regions never become

larger than a few pc, considerably smaller than the scales of interest

here.

Soft UV-photons have smaller cross sections and may penetrate larger

columns. In the presence of a starburst, they are therefore the

dominant driver of the molecular cloud chemistry (Hollenbach & Tielens 1999). While their heating efficiency is low

![]() ,

they are very efficient in dissociating molecules. In such

photon-dominated regions (PDRs), one generally expects somewhat

enhanced cloud temperatures, with most of the emission in

fine-structure lines, as CO is efficiently dissociated. A detailed

review of these processes is given by Meijerink & Spaans (2005).

,

they are very efficient in dissociating molecules. In such

photon-dominated regions (PDRs), one generally expects somewhat

enhanced cloud temperatures, with most of the emission in

fine-structure lines, as CO is efficiently dissociated. A detailed

review of these processes is given by Meijerink & Spaans (2005).

X-ray photons have even smaller cross sections than the soft-UV

photons, and can thus penetrate larger columns. Specifically, a

1 keV photon penetrates a typical column of

![]() cm-2, a 10 keV photon penetrates

cm-2, a 10 keV photon penetrates

![]() cm-2 and a 100 keV photon

cm-2 and a 100 keV photon

![]() cm-2.

For this reason, X-rays can keep molecular clouds at high temperatures

even at high column densities. They have high heating efficiencies of

the order of

cm-2.

For this reason, X-rays can keep molecular clouds at high temperatures

even at high column densities. They have high heating efficiencies of

the order of ![]() ,

and are inefficient in the dissociation of molecules. A fraction of

them may however be reprocessed by the gas and converted in soft-UV

photons, which may lead to some molecular dissociation. Detailed

reviews are given by Meijerink & Spaans (2005); Maloney et al. (1996); Lepp & Dalgarno (1996).

Therefore, X-ray absorption drives a completely different type of

chemistry, and may potentially result in temperatures up to

1000 K. The fraction of molecules, in particular CO, can be very

high.

,

and are inefficient in the dissociation of molecules. A fraction of

them may however be reprocessed by the gas and converted in soft-UV

photons, which may lead to some molecular dissociation. Detailed

reviews are given by Meijerink & Spaans (2005); Maloney et al. (1996); Lepp & Dalgarno (1996).

Therefore, X-ray absorption drives a completely different type of

chemistry, and may potentially result in temperatures up to

1000 K. The fraction of molecules, in particular CO, can be very

high.

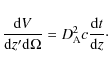

To estimate the potential extent of such a central X-ray dominated

region, we employ a toy model that takes into account the heat input

from the starburst and from the X-ray emission of the supermassive

black hole. We assume here an axisymmetric situation with a central

supermassive black hole and an extended molecular disk in the host

galaxy. The radiation from the SMBH will consist of a soft and a hard

component. The soft component is easily absorbed at the edge of the

molecular clouds and can be neglected for column densities of 1022 cm-2

and above. The X-ray photons, on the other hand, penetrate deeply into

the molecular disk and excite emission there. For the X-ray photons, we

adopt a power-law spectrum for frequencies larger than 1 keV and

use the cross sections given by Verner & Yakovlev (1995). For soft photons from the starburst, we adopt a typical frequency of 10 eV and a cross section of

![]() cm-2 (Meijerink & Spaans 2005). Typical heating efficiencies are

cm-2 (Meijerink & Spaans 2005). Typical heating efficiencies are ![]() in XDRs and

in XDRs and ![]() in PDRs. We assume that the radiation field from the starburst is

roughly constant within the central region. The X-ray radiation field,

on the other hand, will be geometrically diluted and partially shielded

by the gas. To calculate the attenuation of X-rays, we introduce an

effective density for the central region, which is given as

in PDRs. We assume that the radiation field from the starburst is

roughly constant within the central region. The X-ray radiation field,

on the other hand, will be geometrically diluted and partially shielded

by the gas. To calculate the attenuation of X-rays, we introduce an

effective density for the central region, which is given as

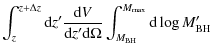

|

(1) |

where ![]() is the volume-filling factor of dense clouds, 105 cm-3 is a typical cloud density and 102 cm-3

a typical density of the atomic medium. We adopt now a specific

reference case for which we evaluate the heating rates and the expected

size of the XDR. The X-ray emission depends essentially on the product

of black hole mass

is the volume-filling factor of dense clouds, 105 cm-3 is a typical cloud density and 102 cm-3

a typical density of the atomic medium. We adopt now a specific

reference case for which we evaluate the heating rates and the expected

size of the XDR. The X-ray emission depends essentially on the product

of black hole mass

![]() ,

the Eddington ratio

,

the Eddington ratio

![]() ,

and the fraction

,

and the fraction ![]() of the total luminosity going into the hard spectrum. We assume a modest black hole mass

of the total luminosity going into the hard spectrum. We assume a modest black hole mass

![]() ,

an Eddington ratio

,

an Eddington ratio

![]() ,

which lies in the typical range of measured Eddington ratios for high-redshift AGN (Kollmeier et al. 2006; Shankar et al. 2009,2004), and a fraction of

,

which lies in the typical range of measured Eddington ratios for high-redshift AGN (Kollmeier et al. 2006; Shankar et al. 2009,2004), and a fraction of

![]() of the total luminosity emitted in X-rays. For the X-ray spectrum, we

adopt a frequency range between 1 and 100 keV with a spectral

slope of -1.

of the total luminosity emitted in X-rays. For the X-ray spectrum, we

adopt a frequency range between 1 and 100 keV with a spectral

slope of -1.

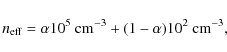

We further assume that the starburst produces a soft UV-radiation field of G0=10 (Habing units) and an effective density of

![]() cm-3.

Such an effective density corresponds to a volume-filling factor of

order 1 and is therefore an upper limit. In real AGN, the effective

density may be smaller in the central region, implying less attenuation

of the X-rays and therefore a larger X-ray dominated region. On the

other hand, the parameter G0 may vary as well and

depend on the strength of the ongoing starburst. For this scenario, the

expected heating rates per hydrogen atom are given in Fig. 1.

cm-3.

Such an effective density corresponds to a volume-filling factor of

order 1 and is therefore an upper limit. In real AGN, the effective

density may be smaller in the central region, implying less attenuation

of the X-rays and therefore a larger X-ray dominated region. On the

other hand, the parameter G0 may vary as well and

depend on the strength of the ongoing starburst. For this scenario, the

expected heating rates per hydrogen atom are given in Fig. 1.

To explore the parameter dependence in more detail, we now consider the

effective density and the strength of the starburst radiation field as

free parameters and check how they influence the size of the XDR,

keeping black hole mass, Eddington ratio and the luminosity fraction in

the hard component as specified above. We consider two cases, one with

the hard component between 1 and 5 keV (case A), and one with the

hard component between 1 and 100 keV (case B). The results for the

XDR size are given in Fig. 2.

In case A shielding effects can be clearly recognized and the size of

the XDR depends more on the effective density than on the strength of

the starburst. As typical molecular cloud densities in these

environments are ![]() 105 cm-3 and the filling factor is of order

105 cm-3 and the filling factor is of order ![]() ,

we can expect an average density of 103 cm-3. At its largest baseline, ALMA can even resolve spatial scales of

,

we can expect an average density of 103 cm-3. At its largest baseline, ALMA can even resolve spatial scales of ![]() 30 pc at z=5, and should thus resolve the corresponding XDRs.

30 pc at z=5, and should thus resolve the corresponding XDRs.

Simulations by Wada et al. (2009) for the clumpy medium at scales of ![]() pc indicate a volume-filling factor

pc indicate a volume-filling factor

![]() .

Models by Galliano et al. (2003)

for NGC 1068, on scales of a few hundred parsec, indicate a

volume-filling factor of 0.01, which still leads to a surface-filling

factor of order 1. For the central 200 pc of our galaxy,

values of

.

Models by Galliano et al. (2003)

for NGC 1068, on scales of a few hundred parsec, indicate a

volume-filling factor of 0.01, which still leads to a surface-filling

factor of order 1. For the central 200 pc of our galaxy,

values of

![]() have been suggested (Oka et al. 2005; McCall et al. 1999).

For a large volume-filling factor, we expect a somewhat smaller XDR due

to the attenuation of X-rays. At the same time, however, this region

will consist of a large number of clouds that are highly excited. For

smaller clumping factors, the number densitiy of clouds will be

reduced, but the size of the XDR increased.

have been suggested (Oka et al. 2005; McCall et al. 1999).

For a large volume-filling factor, we expect a somewhat smaller XDR due

to the attenuation of X-rays. At the same time, however, this region

will consist of a large number of clouds that are highly excited. For

smaller clumping factors, the number densitiy of clouds will be

reduced, but the size of the XDR increased.

Of course, the approach used here is only approximate, as the attenuation may depend on the direction and be stronger in some directions and weaker in others. However, these order-of-magnitude estimates should still be applicable for a broad range of conditions and also hold in cases of spherical rather than flattened structures. An implicit assumption of the model is that we average over sufficiently large scales where the effective density provides a good approximation with respect to X-ray attenuation. For more clumpy structures, the XDR would be more inhomogeneous and reach out further along the low-density regions. In case the large-scale clumpiness is considerable, so that molecular clouds do no longer fill the projected surface area in the beam, our model predictions need to be corrected with the corresponding area-filling factor.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=7.5cm,clip]{13467fg1.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13467-09/Timg36.png)

|

Figure 1: The heating rates per

hydrogen atom due to X-ray absorption (XDR contribution), absorption of

soft UV-photons (PDR contribution) and total heating rate as a function

of radius. The calculation assumes a

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=7.5cm,clip]{13467fg2.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13467-09/Timg37.png)

|

Figure 2:

The expected size of the X-ray dominated region in pc, for a black hole with

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

3 Observables in the PDR

In photon-dominated regions, soft UV-photons from the starburst provide some heat input for molecular clouds, in particular at low column densities, and are efficient in dissociating molecules like H2 or CO. The main coolants in this regime are therefore fine-structure lines of [CII] and [OI]. Depending on the strength of the radiation field, some flux may also be emitted in molecules like CO or HCN, in particular in the low-lying rotational transitions, and there are further fine-structure lines that may contribute as well. As mentioned in the introduction, there are plenty of observations that studied emission from starburst galaxies with present-day sub-mm telescopes (e.g. Maiolino et al. 2007; Klamer et al. 2005; Walter et al. 2009a; Riechers et al. 2008b,a; Walter et al. 2004; Weiß et al. 2005; Greve et al. 2009; Riechers et al. 2009a; Carilli et al. 2002; Omont et al. 1996; Walter et al. 2007).

Table 1: The main observables for ALMA in PDRs at high redshift.

With the upcoming sensitivity of ALMA, we expect that such PDRs can be

probed in more detail as well. Therefore, bright lines like the

[CII] 158 ![]() m

line can be detected at higher significance, allowing higher spectral

resolution and probing the velocity structure of the gas in more

detail. Also, weaker lines may be detected as well, probing gas at

different densities and providing additional information on the

chemical conditions.

m

line can be detected at higher significance, allowing higher spectral

resolution and probing the velocity structure of the gas in more

detail. Also, weaker lines may be detected as well, probing gas at

different densities and providing additional information on the

chemical conditions.

Table 2:

Frequency range, angular resolution

![]() at the largest baseline, line sensitivity

at the largest baseline, line sensitivity ![]() for a linewidth of 300 km s-1 and continuum sensitivity

for a linewidth of 300 km s-1 and continuum sensitivity ![]() for

for ![]() detection in one hour of integration time and primary beam size

detection in one hour of integration time and primary beam size

![]() .

.

To obtain a rough estimate on the expected PDR fluxes in different

lines, we have evaluated the PDR fluxes that we would expect for a

system like the Seyfert 2 galaxy NGC 1068, if it were placed

at high redshift. We adopt z=8. This system consists of a central X-ray dominated region (Galliano et al. 2003) and a circumnuclear starburst ring of ![]() 3 kpc in size, with a stellar mass of

3 kpc in size, with a stellar mass of ![]()

![]() and an age of 5 Myr (Spinoglio et al. 2005). On scales of a few hundred parsecs, one finds a star formation rate of a few times

and an age of 5 Myr (Spinoglio et al. 2005). On scales of a few hundred parsecs, one finds a star formation rate of a few times

![]() yr-1 kpc-2 (Davies et al. 2007). This is close to the star formation rate in Eddington-limited starbursts as suggested by Thompson et al. (2005). To understand which of the fluxes emitted in this region would be detectable with ALMA if this system were located at z=8, we went through the spectroscopic sample of Spinoglio et al. (2005)

and checked which lines would be redshifted into the ALMA frequency

bands, and what would be the expected amount of flux. The fluxes given

by Spinoglio et al. (2005) have been measured with a frequency resolution of 1500 km s-1.

Correspondingly high velocities can indeed be reached in the presence

of fast jets or outflows. However, typical line profiles show that most

of the flux is in a range of

yr-1 kpc-2 (Davies et al. 2007). This is close to the star formation rate in Eddington-limited starbursts as suggested by Thompson et al. (2005). To understand which of the fluxes emitted in this region would be detectable with ALMA if this system were located at z=8, we went through the spectroscopic sample of Spinoglio et al. (2005)

and checked which lines would be redshifted into the ALMA frequency

bands, and what would be the expected amount of flux. The fluxes given

by Spinoglio et al. (2005) have been measured with a frequency resolution of 1500 km s-1.

Correspondingly high velocities can indeed be reached in the presence

of fast jets or outflows. However, typical line profiles show that most

of the flux is in a range of ![]() 150 km s-1, which we adopt here as a fiducial value. The so obtained observable line transitions are summarized in Table 1, while the expected sensitivity and angular resolution at the largest baselines is given in Table 2. For all the transitions, a

150 km s-1, which we adopt here as a fiducial value. The so obtained observable line transitions are summarized in Table 1, while the expected sensitivity and angular resolution at the largest baselines is given in Table 2. For all the transitions, a ![]() detection seems possible for an integration time of a few hours. The

table does not include CO transitions, as the PDR would only

excite the low-lying transitions which would not fall in ALMA's

frequency range for z>8. We note that the expected ratio between [NII] and [CII] is comparable to the observational upper limit derived by Walter et al. (2009b).

detection seems possible for an integration time of a few hours. The

table does not include CO transitions, as the PDR would only

excite the low-lying transitions which would not fall in ALMA's

frequency range for z>8. We note that the expected ratio between [NII] and [CII] is comparable to the observational upper limit derived by Walter et al. (2009b).

4 Expectations for the XDR

As ALMA may for the first time detect and resolve emission for the central X-ray dominated regions, we want to assess here in more detail the expected chemical conditions in the central region and the corresponding fluxes in different lines. We start by discussing the implications of X-rays for the conditions in molecular clouds. We then show how ALMA observations can distinguish between X-ray chemistry and an intense burst of star formation on the same spatial scales. Afterwards, we provide a set of systematic model predictions, first assuming an XDR of constant size, but also considering the potential increase of the XDR in case of a higher X-ray luminosity.4.1 Implications of X-rays for molecular clouds

We follow the chemistry in a one-dimensional molecular cloud complex irradiated by X-rays with the XDR code of Meijerink & Spaans (2005). The model includes more than 50 chemical species and several thousand reactions. For CO, the detailed level populations are solved consistently with the 1D radiation transport equation (Poelman & Spaans 2005,2006). As the low-metallicity case was explored in detail by Spaans & Meijerink (2008), we focus here in particular on situations with about solar metallicity.

The first model we discuss corresponds to the XDR in the Seyfert 2 galaxy NGC 1068 (see Sect. 5.1). We plot chemical abundances and CO emission for cloud column densities between 1020-1024 cm-2 in Fig. 3. Larger column densities correspond to extreme ULIRGs like Arp 220 that is even optically thick around 350 GHz (P. Papadopoulos, private communication). The fiducial gas density of 105 cm-3 has little impact on our results, unless it drops to below 104.5 cm-3. Above this limit, the XDR properties are determined by the ratio of X-ray flux to gas density. For lower densities, emission in the high-J CO lines would not be excited due to the critical densities. However, high-density gas appears to exist in the center of NGC 1068 (Galliano et al. 2003).

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{13467fg3.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13467-09/Timg45.png)

|

Figure 3: A model for the X-ray chemistry in NGC 1068. The adopted flux impinging on the cloud is 170 erg s-1 cm-2. The adopted density is 105 cm-3. Top: the abundances of different species as a function of column density. Middle: the low-J CO lines as a function of column density. Bottom: the high-J CO lines as a function of column density. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{13467fg4.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13467-09/Timg46.png)

|

Figure 4: The X-ray chemistry in a system with X-ray flux of 1 erg s-1 cm-2 impinging on the cloud. The adopted density is 105 cm-3. Top: the abundances of different species as a function of column density. Middle: the low-J CO lines as a function of column density. Bottom: the high-J CO lines as a function of column density. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{13467fg5.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13467-09/Timg47.png)

|

Figure 5: The X-ray chemistry in a system with X-ray flux of 10 erg s-1 cm-2 impinging on the cloud. The adopted density is 105 cm-3. Top: the abundances of different species as a function of column density. Middle: the low-J CO lines as a function of column density. Bottom: the high-J CO lines as a function of column density. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

The strong X-ray flux of ![]() 170 erg s-1 cm-2 in NGC 1068 suffices to make the gas essentially atomic and leads to high temperatures of

170 erg s-1 cm-2 in NGC 1068 suffices to make the gas essentially atomic and leads to high temperatures of ![]() 3000 K, as well as relatively low CO abundances of the order 10-7

due to photodissociation by soft UV-photons produced after the

absorption of X-rays. However, the CO abundance is still higher

than in typical PDRs, and the CO intensity is high, due to the

strong thermal excitation in the hot gas. For a column of

3000 K, as well as relatively low CO abundances of the order 10-7

due to photodissociation by soft UV-photons produced after the

absorption of X-rays. However, the CO abundance is still higher

than in typical PDRs, and the CO intensity is high, due to the

strong thermal excitation in the hot gas. For a column of

![]() ,

our results appear of the same magnitude as in the model of Galliano et al. (2003).

For larger columns, the temperature gradually decreases, the gas

becomes molecular and CO gets more abundant, and we find

intensities of the order 10-2 erg s-1 cm-2 sr-1 in the high-J CO lines.

,

our results appear of the same magnitude as in the model of Galliano et al. (2003).

For larger columns, the temperature gradually decreases, the gas

becomes molecular and CO gets more abundant, and we find

intensities of the order 10-2 erg s-1 cm-2 sr-1 in the high-J CO lines.

To explore the dependence of the chemistry on the X-ray flux, we consider two additional cases. An extreme case with ![]() 1 erg s-1 cm-2 is shown in Fig. 4. In this model, we find lower temperatures of

1 erg s-1 cm-2 is shown in Fig. 4. In this model, we find lower temperatures of ![]() 70 K, a large fraction of molecular gas and CO abundances of the order of 10-4.

While the lower temperature tends to decrease the CO line

intensities, they are still enhanced due to the larger

CO abundance. Above a column of

70 K, a large fraction of molecular gas and CO abundances of the order of 10-4.

While the lower temperature tends to decrease the CO line

intensities, they are still enhanced due to the larger

CO abundance. Above a column of

![]() ,

the intensities increase rather slowly as the lines become optically thick.

,

the intensities increase rather slowly as the lines become optically thick.

As an intermediate scenario, we consider a source with an X-ray flux of ![]() 10 erg s-1 cm-2 (see Fig. 5). In this model, the temperature is increased to

10 erg s-1 cm-2 (see Fig. 5). In this model, the temperature is increased to ![]() 100 K. The CO abundance is initially of the order

100 K. The CO abundance is initially of the order

![]() and increases to

and increases to ![]() 10-4 for larger columns. For columns less than

10-4 for larger columns. For columns less than

![]() ,

the intensities are thus reduced by about an order of magnitude

compared to the previous case, while they are increased by an order of

magnitude for larger columns.

,

the intensities are thus reduced by about an order of magnitude

compared to the previous case, while they are increased by an order of

magnitude for larger columns.

4.2 Separating the XDR from a nuclear starburst

In the center of an active galaxy, not only the X-ray emission is

enhanced, but one may expect the presence of a strong nuclear

starburst. For instance, Arp 220 harbors such a starburst on

scales of ![]() 300 pc. We therefore compare the expected CO line SED of a strong starburst with G0=105 with the CO line SEDs in X-ray dominated regions, based on the models provided by Meijerink et al. (2007).

We normalize them such that the CO (10-9) transition has the same

intensity in all models. In this case, the SEDs can hardly be

distinguished at the low-J transitions that are typically observed at low redshift (see Fig. 6). At higher-J

transitions, the PDR SED drops considerably and flattens on a low level

due to the small amount of hot gas in the outer layer of the molecular

cloud. We expect that a value of G0=105

is a robust upper limit for the soft-UV flux that can be obtained in a

galaxy. In fact, larger values have never been indicated in previous

observations, and indeed such a value would require extreme conditions

as in the Orion Bar throughout all of the galaxy. In XDRs, a much

larger fraction of the gas is at high temperatures, and thus the SED is

not expected to drop as rapidly.

300 pc. We therefore compare the expected CO line SED of a strong starburst with G0=105 with the CO line SEDs in X-ray dominated regions, based on the models provided by Meijerink et al. (2007).

We normalize them such that the CO (10-9) transition has the same

intensity in all models. In this case, the SEDs can hardly be

distinguished at the low-J transitions that are typically observed at low redshift (see Fig. 6). At higher-J

transitions, the PDR SED drops considerably and flattens on a low level

due to the small amount of hot gas in the outer layer of the molecular

cloud. We expect that a value of G0=105

is a robust upper limit for the soft-UV flux that can be obtained in a

galaxy. In fact, larger values have never been indicated in previous

observations, and indeed such a value would require extreme conditions

as in the Orion Bar throughout all of the galaxy. In XDRs, a much

larger fraction of the gas is at high temperatures, and thus the SED is

not expected to drop as rapidly.

If the total amount of energy injected by X-rays and by soft-UV photons is comparable (within a factor of 10), then the presence of X-rays can be clearly inferred using the CO (16-15) transition, if the local X-ray flux is at least 2.8 erg s-1 cm-2. However, as discussed in Sect. 2, we expect X-ray flux to dominate over the soft-UV in the center of the galaxy. Observations at even higher-J transitions may be useful to determine the local amount of X-ray flux from the CO line SED. A potential uncertainty is the presence of cold dust, which may to some degree absorb the CO line emission and thus change the appearance of the SED. Due to the characteristic scaling of dust absorption with wavelength, we expect that such a behavior could be recognized and potentially corrected. For this purpose, it is of course desirable to measure as many high-J CO lines as possible.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{13467fg6.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13467-09/Timg51.png)

|

Figure 6: A comparison of the CO line SED in case of an intense starburst with G0=105 with the corresponding SED for molecular clouds under X-ray irradiation, for different X-ray fluxes in erg s-1 cm-2. The spectra are normalized such that they have the same intensity in the 10th transition. If the impinging X-ray flux is at least 2.8 erg s-1 cm-2, observations of the 15th CO rotational transition can clearly discriminate between PDR and XDR chemistry. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

4.3 Model predictions for XDRs of constant size

Although we have shown in Sect. 2

that the central XDRs can likely be resolved with ALMA, it is currently

not clear how the expected XDR size varies with X-ray luminosity. If

the strength of the soft-UV field is independent of this, one should on

average expect a larger XDR for higher X-ray luminosities. However, it

is also conceivable that the X-ray luminosity is indicative of the

system as a whole, and that a higher X-ray luminosity may be

accompanied by a stronger soft-UV field. In such a case, one might

expect a smaller increase in the XDR size or even a constant size. For

this reason, we will consider two extreme cases, assuming that more

realistic scenarios should lie in between the two. In this subsection,

we will assume that the size of the XDR is always constant, of ![]() 200 pc.

Of course, the numbers given here can be easily rescaled for other XDR

sizes, or for area-filling factors smaller than 1. In the following

subsection, we will then discuss the implications of varying the X-ray

luminosity for constant G0.

200 pc.

Of course, the numbers given here can be easily rescaled for other XDR

sizes, or for area-filling factors smaller than 1. In the following

subsection, we will then discuss the implications of varying the X-ray

luminosity for constant G0.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{13467fg7.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13467-09/Timg52.png)

|

Figure 7: The expected flux in mJy for high-J CO lines, for a central XDR of 200 pc, and molecular clouds of 105 cm-3, as a function of X-ray luminosity and cloud column density. We focus on lines that fall in ALMA band 6, which offers a good compromise between angular resolution and sensitivity. For a source at z=5 (solid line), this corresponds to the (10-9) CO transition, for a source at z=8, it corresponds to the (14-13) CO transition. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

For a first estimate, let us consider at source at z=5 with an XDR of at least 100 pc, corresponding to an angular scale of 0.016'', and a typical intensity in the high-J CO lines of 10-3 erg s-1 cm-2 sr-1. As can be seen from the calculations above, such an intensity can be reached in a broad range of systems for column densities of at least 1023 cm-2, and in fact also for column densities of at least 1022 cm-2 in the presence of sufficient X-ray flux. With a fiducial velocity dispersion of 300 km s-1, this corresponds to a flux of 0.03 mJy, which is detectable in a bit more than a day in ALMA band 6.

In a similar way, it is possible to calculate the expected fluxes also

in various fine-structure lines. Based on the detailed parameter study

provided by Meijerink et al. (2007)![]() ,

which shows the expected fluxes in various lines as a function of X-ray

luminosity density and column density, we therefore provide detailed

predictions for the fluxes from the central X-ray dominated region,

assuming a characteristic size of 200 pc, consistent with the

results obtained in Sect. 2.

,

which shows the expected fluxes in various lines as a function of X-ray

luminosity density and column density, we therefore provide detailed

predictions for the fluxes from the central X-ray dominated region,

assuming a characteristic size of 200 pc, consistent with the

results obtained in Sect. 2.

For the high-J CO lines, we focus on those which

are redshifted into ALMA band 6, which offers a good compromise between

angular resolution (0.014'' at the largest baseline) and sensitivity (![]() 0.04 mJy for an integration time of one day,

0.04 mJy for an integration time of one day, ![]() detection and a line width of 300 km s-1). At a redshift z=5, this corresponds to the (10-9) CO transition, at z=8

to the (14-13) CO transition. We assume that the projected surface

area is homogeneously filled with molecular clouds with central

densities of 105 cm-3. Figure 7 shows how the expected flux varies as a function of the cloud column density and the X-ray luminosity

detection and a line width of 300 km s-1). At a redshift z=5, this corresponds to the (10-9) CO transition, at z=8

to the (14-13) CO transition. We assume that the projected surface

area is homogeneously filled with molecular clouds with central

densities of 105 cm-3. Figure 7 shows how the expected flux varies as a function of the cloud column density and the X-ray luminosity![]() . Similar results would be obtained for cloud densities of 104.5 cm-3, while it is more difficult to excite CO emission at lower densities.

. Similar results would be obtained for cloud densities of 104.5 cm-3, while it is more difficult to excite CO emission at lower densities.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{13467fg8.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13467-09/Timg53.png)

|

Figure 8:

The expected flux in mJy for the [CII] 158 |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{13467fg9.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13467-09/Timg54.png)

|

Figure 9:

The expected flux in mJy for the [CII] 158 |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{13467fg10.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13467-09/Timg55.png)

|

Figure 10:

The expected flux in mJy for the [OI] 63 |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{13467fg11.eps}\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13467-09/Timg56.png)

|

Figure 11:

The expected flux in mJy for the [OI] 63 |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{13467fg12.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13467-09/Timg57.png)

|

Figure 12:

The expected flux in mJy for the [OI] 146 |

| Open with DEXTER | |

The figure illustrates that higher fluxes can be obtained for larger column densities, while intermediate X-ray fluxes are ideal for stimulating emission in the CO lines considered here. This is because at very high fluxes, a significant amount of X-rays would be converted into soft UV-photons and dissociate the molecules.

In Figs. 8 and 9, we show the corresponding results for the [CII] 158 ![]() m line, both for a density of 105 cm-3 and a density of 104 cm-3. For densities of 105 cm-3,

low column densities are sufficient to yield a detectable amount of

flux, and the flux monotonically increases with the X-ray luminosity.

As in the PDR case, this line is therefore valuable to explore the

centers of high-redshift quasars, and provides complementary

information to the CO lines. For densities of 104 cm-3, we find a stronger dependence on column density, and indeed columns of at least 1023 cm-2 are needed to yield a detectable amount of flux.

m line, both for a density of 105 cm-3 and a density of 104 cm-3. For densities of 105 cm-3,

low column densities are sufficient to yield a detectable amount of

flux, and the flux monotonically increases with the X-ray luminosity.

As in the PDR case, this line is therefore valuable to explore the

centers of high-redshift quasars, and provides complementary

information to the CO lines. For densities of 104 cm-3, we find a stronger dependence on column density, and indeed columns of at least 1023 cm-2 are needed to yield a detectable amount of flux.

The results for the [OI] 63 ![]() m line are given in Figs. 10 and 11, again for densities of 105 cm-3 and 104 cm-3, respectively. This line quickly becomes optically thick. Therefore, in particular for cloud densities of 105 cm-3,

it is insensitive to the column density, but provides a good measure

for the X-ray flux. It is very bright. Even for cloud densities of 104 cm-3,

it depends more on X-ray luminosity than column density, and is still

detectable in the case of high column densities and strong X-ray

fluxes. It is thus well-suited to study gas dynamics in the central XDR

by resolving the line profile.

m line are given in Figs. 10 and 11, again for densities of 105 cm-3 and 104 cm-3, respectively. This line quickly becomes optically thick. Therefore, in particular for cloud densities of 105 cm-3,

it is insensitive to the column density, but provides a good measure

for the X-ray flux. It is very bright. Even for cloud densities of 104 cm-3,

it depends more on X-ray luminosity than column density, and is still

detectable in the case of high column densities and strong X-ray

fluxes. It is thus well-suited to study gas dynamics in the central XDR

by resolving the line profile.

We also provide results for the [OI] 146 ![]() m line in Fig. 12, for a cloud density of 105 cm-3.

For lower densities, this line is hard to excite. It can also be very

bright and shows a strong dependence on the X-ray flux. The ratio

between the [OI] 63

m line in Fig. 12, for a cloud density of 105 cm-3.

For lower densities, this line is hard to excite. It can also be very

bright and shows a strong dependence on the X-ray flux. The ratio

between the [OI] 63 ![]() m line and the 145

m line and the 145 ![]() m line is generally about 0.1.

m line is generally about 0.1.

Emission from neutral carbon seems more difficult to detect. The intensity of the [CI] 369 ![]() m line is typically at least an order of magnitude smaller than the intensity in the [CII] 158

m line is typically at least an order of magnitude smaller than the intensity in the [CII] 158 ![]() m line, and only significant in the case of strong X-ray fluxes and high column densities. As discussed in Sect. 5.3, the relatively low ratio between these lines in the recently detected z=6.42 quasar puts a significant constraint on theoretical models. Other carbon lines like [CI] 609

m line, and only significant in the case of strong X-ray fluxes and high column densities. As discussed in Sect. 5.3, the relatively low ratio between these lines in the recently detected z=6.42 quasar puts a significant constraint on theoretical models. Other carbon lines like [CI] 609 ![]() m or [CI] 230

m or [CI] 230 ![]() m are even weaker and should never be visible. Additional lines like [SiII] 35

m are even weaker and should never be visible. Additional lines like [SiII] 35 ![]() m or [FeII] 26

m or [FeII] 26 ![]() m can be bright as well (Meijerink et al. 2007), but typically have too short wavelengths for ALMA, except at redshifts z>9.

m can be bright as well (Meijerink et al. 2007), but typically have too short wavelengths for ALMA, except at redshifts z>9.

The reader may notice that for the model predictions given in this subsection, we restricted ourselves to a range of X-ray luminosities of about two orders of magnitude, corresponding to the range of X-ray fluxes available in the data by Meijerink et al. (2007). This range of data has been chosen such that it covers the observationally interesting cases. For lower fluxes, or in our case lower X-ray luminosities, we would not expect significant emission driven by X-rays, as can be seen in the corresponding figures. Similarly, it is straightforward to extrapolate the behavior towards higher X-ray fluxes: as shown in Fig. 7, the CO intensities decrease considerably at higher luminosities. This is because part of the X-rays are reprocessed to soft-UV photons that dissociate all the CO. At even higher intensities, the gas temperature would increase up to 104 K and become fully ionized. Molecules would no longer survive under such circumstances. The emission of [CII] may increase a bit further, until a large fraction of carbon is doubly-ionized at temperatures near 104 K. Similar considerations hold for the oxygen line. However, it is not clear whether such scenarios are actually physical, or if the molecular cloud would rather be photo-evaporated at that point. As already mentioned above, the size of the XDR may be more extended in the case of such high luminosities. Then, moderate X-ray fluxes will be present on larger scales.

In summary, we can therefore conclude that the main observables for the central XDR are the high-J CO lines as well as the fine-structure lines of [CII] and [OI]. The [OI] 63 and 146 ![]() m

lines show a strong dependence on X-ray luminosity and may provide a

good handle on this quantity. In combination with an observation of the

[CII] or high-J CO lines, the X-ray luminosity can be estimated as well. As shown by Meijerink et al. (2007),

such line ratios also provide valuable information on gas density and

temperature. We also note that it is possible to discriminate such XDRs

from regions with strong mechanical heating (Papadopoulos et al. 2008).

This can be done for instance on the basis of the observed X-ray

luminosity, or by looking at the dust SED. While in XDRs, both dust and

gas will be at high temperatures in dense clouds, there should be a

clear discrepancy between gas and dust temperature if heating is due to

local shocks. We therefore expect that the physical conditions in the

central XDRs can be probed in detail with ALMA.

m

lines show a strong dependence on X-ray luminosity and may provide a

good handle on this quantity. In combination with an observation of the

[CII] or high-J CO lines, the X-ray luminosity can be estimated as well. As shown by Meijerink et al. (2007),

such line ratios also provide valuable information on gas density and

temperature. We also note that it is possible to discriminate such XDRs

from regions with strong mechanical heating (Papadopoulos et al. 2008).

This can be done for instance on the basis of the observed X-ray

luminosity, or by looking at the dust SED. While in XDRs, both dust and

gas will be at high temperatures in dense clouds, there should be a

clear discrepancy between gas and dust temperature if heating is due to

local shocks. We therefore expect that the physical conditions in the

central XDRs can be probed in detail with ALMA.

4.4 Model predictions for variable XDR-sizes

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{13467fg13.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13467-09/Timg58.png)

|

Figure 13:

The expected flux in mJy for the CO (14-13) transition (solid line), [CII] 158 |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{13467fg14.eps}\vspace*{-2mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13467-09/Timg59.png)

|

Figure 14:

The expected flux in mJy for the CO (14-13) transition (solid line), [CII] 158 |

| Open with DEXTER | |

As mentioned above, the size of the XDR may increase considerably for increasing X-ray luminosity. We first explore the dependence on the average density and the X-ray luminosity, assuming a typical cloud column density of 1023 cm-2, and a soft-UV field G0=100. The X-ray spectrum is assumed to range from 1 to 100 keV. As shown in Sect. 2, the size of the XDR then varies as a power-law with density. The same is true for the expected fluxes of CO, [CII] and [OI], as shown in Fig. 13. We estimate those by adopting a typical value in mJy on scales corresponding to the size of the XDR. These should indeed consitute the main contribution. For [CII] and [OI], the total flux may be a bit larger, as the expected amount of emission increases with the X-ray flux (see previous subsection). CO, on the other hand, might be efficiently dissociated in the very inner core. However, we do not expect this to affect our predictions significantly.

We also explore the role of the molecular cloud column density for the expected fluxes. For this purpose, we adopt an average density of 104 cm-3 and a soft-UV field G0=100. In Fig. 14, we show the expected fluxes as a function of X-ray luminosity and column density. As a generic feature, we find that the expected fluxes vary for columns smaller than 1023 cm-2, but level-off for higher values. The fluxes in high-column density systems should thus essentially depend on the X-ray luminosity only.

5 Evidence for XDRs and the interpretation of sub-mm line observations

Although the presence of a central X-ray dominated region seems unavoidable from a theoretical point of view, we want to review current evidence for the presence of central XDRs in active galaxies. Such evidence is present in local galaxies like NGC 1068 that can be studied in great detail, as well as in high-redshift quasars like APM 08279 in which the corresponding fluxes are magnified by a gravitational lens. Similar indications are present also in the Cloverleaf quasar, where CO fluxes up to the (9-8) transition have been measured, and no turnover in the line SED has been found yet (Bradford et al. 2009). These sources will allow a first test for the expectations we have formulated in the previous section once the ALMA telescope becomes available. We also discuss the z=6.42 quasar SDSS J114816.64+525150.3, as it provides a good and interesting example concerning the complex interpretation of sub-mm line observations. We will further discuss how its properties can be understood better if additional data are provided, with particular focus on the role of ALMA.

To distinguish between different excitation mechanisms of molecular clouds, it is very important to have observational diagnostics for the various excitation mechanisms. First efforts for modelling the chemistry in XDRs were performed by Maloney et al. (1996) and Lepp & Dalgarno (1996), while PDR chemistry was originally studied by Hollenbach & Tielens (1999). Recent efforts to discriminate such models have been performed by Pérez-Beaupuits et al. (2009,2007), and new diagnostic diagrams to discriminate AGN- and starburst-dominated galaxies have been provided by Spoon et al. (2007) and Hao et al. (2009).

5.1 NGC 1068

As shown by Galliano et al. (2003), NGC 1068 contains a central XDR. Their analysis is based on the observed intensitiy of the H2 2.12 ![]() m line (Galliano & Alloin 2002) and the rotational CO lines (Schinnerer et al. 2000), and showed that the observed emission can be consistently explained with the XDR-model of Maloney et al. (1996) under the following assumptions:

m line (Galliano & Alloin 2002) and the rotational CO lines (Schinnerer et al. 2000), and showed that the observed emission can be consistently explained with the XDR-model of Maloney et al. (1996) under the following assumptions:

- the central engine is a power-law X-ray source with spectral slope

and luminosity of 1044 erg s-1 in the 1-100 keV range, consistent with the X-ray luminosity determined from VLBI water maser observations (Greenhill et al. 1996);

and luminosity of 1044 erg s-1 in the 1-100 keV range, consistent with the X-ray luminosity determined from VLBI water maser observations (Greenhill et al. 1996);

- the emission originates from molecular clouds with a density of 105 cm-3, a column of 1022 cm-2 at a distance of 70 pc and solar metallicity.

5.2 APM 08279

In the z=3.9 galaxy APM 08279, the usual geometric effects concerning emission from the central regions are compensated by a gravitational lens. It therefore provides an ideal test case to study the emission we might see when future telescopes like ALMA can observe the central regions with higher sensitivity and higher spatial resolution. As expected for molecular clouds excited by X-rays, they find that the CO line intensity increases up to the (10-9) transition. Significant flux is also detected in the HCN(5-4) line.Based on brightness temperature arguments, the results from high-resolution mapping and lens models from the literature, Weiß et al. (2007) show that the molecular lines arise from a compact (100-300 pc), highly gravitationally magnified ( m=60-110) region surrounding the central AGN. It is interesting to note that this amount of magnification is comparable to the increase in sensitivity due to ALMA. They can distinguish two components of the gas: a cool component with a density of 105 cm-3 and a temperature of 65 K, on scales larger than 100 pc, and a warm component of gas with 104 cm-3 and temperatures of 220 K on scales smaller than 100 pc. So far, their results do not provide indications for inhomogeneities.

We have compared the turnover for the rotational CO lines found by Weiß et al. (2007) with the grid of PDR and XDR model predictions that were made publicly available by Meijerink et al. (2007). In the PDR case, we find that cloud densities of 105 cm-3 and a radiation field of

![]() with a cloud column of

with a cloud column of ![]()

![]() cm-2 are required. For the XDR case, the turn-over can be explained with a cloud density of 104.25 cm-3, an X-ray flux of 2.8 erg s-1 cm-2 and a cloud column density of

cm-2 are required. For the XDR case, the turn-over can be explained with a cloud density of 104.25 cm-3, an X-ray flux of 2.8 erg s-1 cm-2 and a cloud column density of ![]()

![]() cm-2. In both cases, we need to require that additional cold gas is present that emits in particular in the low-lying J levels to explain the observed ratio between high-J and low-J rotational CO lines.

cm-2. In both cases, we need to require that additional cold gas is present that emits in particular in the low-lying J levels to explain the observed ratio between high-J and low-J rotational CO lines.

The X-ray spectrum of APM 08279 has been observed with Chandra (Chartas et al. 2002), indicating a luminosity of

![]() erg s-1. Adopting a lens magnification of

erg s-1. Adopting a lens magnification of ![]() ,

one expects a flux of

,

one expects a flux of ![]() 354 erg s-1 cm-2 at a distance of 100 pc for an optically thin source. However, for a density of 104.25 cm-3, we expect significant attenuation effects that may considerably decrease the flux in the cloud. As shown by Wada et al. (2009),

shielding may locally vary by two orders of magnitude due to column

density fluctuations in the torus and give rise to a peak optical depth

of

354 erg s-1 cm-2 at a distance of 100 pc for an optically thin source. However, for a density of 104.25 cm-3, we expect significant attenuation effects that may considerably decrease the flux in the cloud. As shown by Wada et al. (2009),

shielding may locally vary by two orders of magnitude due to column

density fluctuations in the torus and give rise to a peak optical depth

of ![]() for frequencies of 3 keV. A more conservative magnification factor of M=4,

as derived by Riechers et al. (2009b), reduces the physical X-ray

luminosity and leads to X-ray fluxes closer to the estimates from our

XDR model.

for frequencies of 3 keV. A more conservative magnification factor of M=4,

as derived by Riechers et al. (2009b), reduces the physical X-ray

luminosity and leads to X-ray fluxes closer to the estimates from our

XDR model.

With ALMA, it will be possible to probe the distribution of these gas components and their kinematics in even more detail. Due to the higher sensitivity, the error bars in the flux measurement will decrease further and one may probe whether the turnover occurs at the (10-9) transition, as indicated now, or indeed even at higher-J levels. In this case, one could clearly discriminate between PDR and XDR models.

| Figure 15: A sketch for a situation with an inhomogeneous XDR, motivated by the observations of Galliano et al. (2003) in NGC 1068. While X-rays are shielded by a central absorber along the line of sight, they may stimulate emission in molecular clouds in the perpendicular direction with the typical characteristics of XDRs. |

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

5.3 SDSS J114816.64+525150.3

The recent detection of a kiloparsec-scale hyper-starburst in the source SDSS J114816.64+525150.3 at z=6.42 by Walter et al. (2009a) has stimulated great observational interest that led to a broad collection of data on this source. Recently, Riechers et al. (2009a) provided a table with fluxes in the CO (3-2), (6-5) and (7-6) transitions, fluxes in the CI line and the [CII] line, as well as upper limits on five additional lines. Although the publication of such upper limits is very valuable and can provide important constraints on theoretical models, for simplicity we focus here on those lines that were actually detected. As we shall see, the interpretation of those is already complex, and a more thorough analysis would be beyond the scope of this work. The models and data empoyed here are based on the publicly available grids provided by Meijerink et al. (2007). Due to the large scales of this source, we assume that most of the flux is driven by PDR chemistry, especially because the relevant scales for XDRs are currently unresolved.

To understand the complexity of these data, it is illustrative to check

whether a model with one given density and a fixed parameter G0

is able to explain them. For CO, the ratio between the (6-5) and the

(3-2) transition is about 3.35, while the ratio between (7-6)

and (3-2) is about 3.15. Although it appears that the

turnover in the SED may have been reached, this is not fully clear from

the data, as the uncertainty in the fluxes is ![]()

![]() .

The increased intensity in the (6-5) transition requires a significant

amount of soft-UV flux, while the almost flat behavior indicates that

the gas should be at intermediate densities of about

.

The increased intensity in the (6-5) transition requires a significant

amount of soft-UV flux, while the almost flat behavior indicates that

the gas should be at intermediate densities of about ![]() 104 cm-3.

At higher densities, the seventh rotational level would be more easily

excited, which would give rise to a significant discrepancy between the

(6-5) and the (7-6) transition, even for low values of G0.

For lower densities, on the other hand, it becomes difficult to excite

these rotational levels. A reasonable fit to the CO SED can thus

be obtained with n=104 cm-3 and

G0=101.75.

104 cm-3.

At higher densities, the seventh rotational level would be more easily

excited, which would give rise to a significant discrepancy between the

(6-5) and the (7-6) transition, even for low values of G0.

For lower densities, on the other hand, it becomes difficult to excite

these rotational levels. A reasonable fit to the CO SED can thus

be obtained with n=104 cm-3 and

G0=101.75.

A problem arises, though, if the observed fluxes in [CII] and CI should

result from the same gas component. In this case, our model predicts a

flux ratio of [CII] to CI of ![]() 600,

and the intensity of [CII] and CI would be much higher than the

CO intensities. We note, however, that the fine-structure lines

are already optically thick at these densities, while the CO lines

are optically thin. Thus, additional clouds may be present that enhance

the CO intensities, while the optically thick emission in [CII]

and CI is unaffected. Nevertheless, as observations show a

corresponding line ratio of 17.7, these lines should originate from a

different gas component. Our models require the presence of additional

gas clouds with density of

600,

and the intensity of [CII] and CI would be much higher than the

CO intensities. We note, however, that the fine-structure lines

are already optically thick at these densities, while the CO lines

are optically thin. Thus, additional clouds may be present that enhance

the CO intensities, while the optically thick emission in [CII]

and CI is unaffected. Nevertheless, as observations show a

corresponding line ratio of 17.7, these lines should originate from a

different gas component. Our models require the presence of additional

gas clouds with density of ![]() 103 cm-3,

103 cm-3,

![]() and large columns

and large columns

![]() cm-2,

at which enough of the soft-UV flux is shielded to yield a low ratio

between [CII] and CI. This line ratio is indeed strikingly low, as PDR

models generally predict larger numbers for this ratio, and also in

this case the match is not perfect, but only within the

cm-2,

at which enough of the soft-UV flux is shielded to yield a low ratio

between [CII] and CI. This line ratio is indeed strikingly low, as PDR

models generally predict larger numbers for this ratio, and also in

this case the match is not perfect, but only within the ![]() error of the CI measurement. Although this may be an issue due to

uncertain abundance ratios, a more precise determination of the flux in

this line is highly desirable.

error of the CI measurement. Although this may be an issue due to

uncertain abundance ratios, a more precise determination of the flux in

this line is highly desirable.

So far, we have postulated two gas components to explain the CO line SED and the fluxes from [CII] and CI. It is however important to cross-check whether these components may affect the line ratios that the other component should reproduce. For the CO line SED, indeed the intensity in a low-density cloud is smaller by one order of magnitude. The high-density component, however, gives rise to an intensity in [CII] that is smaller than the corresponding intensity from the other component by just a factor of 5. To avoid that this perturbes the [CII] to CI flux ratio, we need to require that the low-density gas is more abundant than the gas at high densities. In this case, it seems however likely that the low-density gas would perturb the CO line SED significantly.

The most probable explanation in terms of a two-component

picture is thus that indeed the low-density component is more abundant

and explains the observed fine-structure lines. The impinging soft-UV

flux must be moderate in order to reconcile the low ratio between these

lines. To still explain the observed CO line SED, we need to

require that the high-density component is at higher temperatures, due

to an increased value of

![]() .

As one generally expects that high-density gas is exposed to a weaker

radiation field due to shielding effects, this component should be

spatially separated in regions of strong active star formation.

Alternative scenarios are however feasible as well. For instance, the

observed [CII]/CI ratio may also be produced in the presence of a weak

X-ray background rather than a soft-UV field, or if a the cosmic-ray

background is enhanced by a factor of 10-100 compared to the Milky Way

(see also Meijerink et al. 2006).

.

As one generally expects that high-density gas is exposed to a weaker

radiation field due to shielding effects, this component should be

spatially separated in regions of strong active star formation.

Alternative scenarios are however feasible as well. For instance, the

observed [CII]/CI ratio may also be produced in the presence of a weak

X-ray background rather than a soft-UV field, or if a the cosmic-ray

background is enhanced by a factor of 10-100 compared to the Milky Way

(see also Meijerink et al. 2006).

Of course, this model is still an oversimplification, as one may indeed

expect a variety of different densities in both star-forming and more

quiescent parts of the galaxy. In addition, there are theoretical

uncertainties concerning the metallicity and the abundance ratios that

may affect our results. Nevertheless, this model reproduces the main

features in the observed fluxes and illustrates the difficulties in

simultaneously modeling observations in different lines. This challenge

will become more severe, as the high sensitivity of ALMA will allow us

to study even more lines. On the other hand, it is certainly desirable

if some of the simplest models can be discarded on such grounds. We

note that such models are also predictive. For the scenario described

here, we would for instance expect that also the flux in the

[OI] 63 ![]() m line and the [OI] 145

m line and the [OI] 145 ![]() m

line originates predominantly from the low-density gas component. In

this case, the ratio of these fluxes to the flux in [CII] would be

0.06-0.1 and

m

line originates predominantly from the low-density gas component. In

this case, the ratio of these fluxes to the flux in [CII] would be

0.06-0.1 and

![]() ,

respectively. If the oxygen abundance is enhanced by a factor of 4 compared to the galactic abundance, the flux in the 63

,

respectively. If the oxygen abundance is enhanced by a factor of 4 compared to the galactic abundance, the flux in the 63 ![]() m line would be larger by a factor of 2.

m line would be larger by a factor of 2.

With future ALMA measurements, we expect that the CO line SED can be probed in more detail and with higher accuracy at higher-J levels, to check whether the turnover has already been reached. Apart from the observed gas component that indicates a turnover near the J=6 transition, a higher density component may be present that can more easily excite flux at higher-J levels. The increased sensitivity and angular resolution of ALMA may help to detect spatial variations in the different fluxes, which may help to discriminate regions of intense star formation from more quiescent zones. In the center of the galaxy, ALMA can check for the presence of an X-ray dominated region. Significant progress may however be possible in the mean time, for instance by measuring additional high-J CO lines or by a more accurate determination of the [CII] to CI flux ratio.

6 The expected number of sources

As shown in Sect. 3, large-scale PDR fluxes, for instance in the [CII] 158 ![]() m line or the [OI] 146

m line or the [OI] 146 ![]() m

line, are sufficiently large for detection in a few hours. Fluxes from

the XDR originate from a smaller region, but may also give rise to a

significant flux component. With an integration time of a few hours,

active galaxies with a comparable brightness as NGC 1068 should be

detectable in an ALMA field of view. One might therefore wonder whether

a search for active galaxies, based on the before-mentioned

fine-structure lines, is feasible. Beyond that, it is of strong

interest to know whether there are reasonable chances to find active

galaxies with other surveys such as JWST. In such cases, ALMA could

perform relevant follow-up studies that probe the central X-ray

dominated regions and the gas dynamics within them. If a sufficient

number of sources is obtained, ALMA can probe the feeding of black

holes between redshift 6 and 10 and thus constrain models

concerning the growth of supermassive black holes based on the

diagnostics provided here. We therefore conclude this paper with an

estimate on the high-redshift black hole population.

m

line, are sufficiently large for detection in a few hours. Fluxes from

the XDR originate from a smaller region, but may also give rise to a

significant flux component. With an integration time of a few hours,

active galaxies with a comparable brightness as NGC 1068 should be

detectable in an ALMA field of view. One might therefore wonder whether

a search for active galaxies, based on the before-mentioned

fine-structure lines, is feasible. Beyond that, it is of strong

interest to know whether there are reasonable chances to find active

galaxies with other surveys such as JWST. In such cases, ALMA could

perform relevant follow-up studies that probe the central X-ray

dominated regions and the gas dynamics within them. If a sufficient

number of sources is obtained, ALMA can probe the feeding of black

holes between redshift 6 and 10 and thus constrain models

concerning the growth of supermassive black holes based on the

diagnostics provided here. We therefore conclude this paper with an

estimate on the high-redshift black hole population.

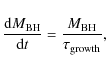

To assess this possibility in more detail, we start with some general considerations regarding the black hole population at z>6. Then we discuss estimates on the number of sources and the possibility to detect them with an ALMA deep field.

6.1 Black hole growth at high redshift

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{13467fg16.eps} %\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13467-09/Timg75.png)

|

Figure 16:

The average accretion history of a black hole with

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

As shown recently by Shankar et al. (2009), a supermassive black hole with

![]() today had, on average,

today had, on average,

![]() at z=5.

Therefore, one needs to explain how supermassive black holes have

accreted this mass at early times. Indeed, some of them need to accrete

even faster, as

at z=5.

Therefore, one needs to explain how supermassive black holes have

accreted this mass at early times. Indeed, some of them need to accrete

even faster, as