| Issue |

A&A

Volume 513, April 2010

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A75 | |

| Number of page(s) | 9 | |

| Section | Interstellar and circumstellar matter | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/200913171 | |

| Published online | 30 April 2010 | |

Polarimetry of an intermediate-age open

cluster: NGC 5617![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

A. M. Orsatti1,2,3 - C. Feinstein1,2,3 - M. M. Vergne1,2,3 - R. E. Martínez1,2 - E. I. Vega1,3

1 - Facultad de Ciencias Astronómicas y Geofísicas, Observatorio

Astronómico, Paseo del Bosque, 1900 La Plata, Argentina

2 - Instituto de Astrofísica de La Plata, CONICET, Argentina

3 - Member of the Carrera del Investigador Científico, CONICET,

Argentina

Received 24 August 2009 / Accepted 5 January 2010

Abstract

Aims. We present polarimetric observations in the UBVRI bands

of 72 stars located in the direction of the medium age open

cluster NGC 5617. Our intention is to use polarimetry

as a tool in membership identification, by building on

previous investigations intended mainly to determine the cluster's

general characteristics rather than provide membership suitable for

studies such as stellar content and metallicity, as well as

study the characteristics of the dust lying between the Sun and

the cluster.

Methods. The obsevations were carried out using the

five-channel photopolarimeter of the Torino Astronomical Observatory

attached to the 2.15 m telescope at the Complejo Astronómico

El Leoncito (CASLEO; Argentina).

Results. We are able to add 32 stars to the

list of members of NGC 5617, and review the situation for

others listed in the literature. In particular, we find that

five blue straggler stars in the region of the cluster are located

behind the same dust as the member stars are and we confirm the

membership of two red giants. The proposed polarimetric memberships are

compared with those derived by photometric and kinematical methods,

with excellent results. Among the observed stars, we

identify 10 with intrinsic polarization in their light.

NGC 5617 can be polarimetrically characterized with ![]() and

and ![]() .

The spread in polarization values for the stars observed in the

direction of the cluster seems to be caused by the uneven distribution

of dust in front of the cluster's face. Finally, we find that

in the direction of the cluster, the interstellar medium is apparently

free of dust, from the Sun's position up to the Carina-Sagittarius arm,

where NGC 5617 seems to be located at its farthest border.

.

The spread in polarization values for the stars observed in the

direction of the cluster seems to be caused by the uneven distribution

of dust in front of the cluster's face. Finally, we find that

in the direction of the cluster, the interstellar medium is apparently

free of dust, from the Sun's position up to the Carina-Sagittarius arm,

where NGC 5617 seems to be located at its farthest border.

Key words: dust, extinction - open clusters and associations: individual: NGC 5617

1 Introduction

The polarimetric technique is a very useful tool for obtaining

significant information (e.g. magnetic field

direction,

![]() ,

,

![]() )

about the dust located in front of a luminous object. Open clusters are

very good candidates for carrying out polarimetric observations,

because previous photometric and spectroscopic studies of these

clusters have provided detailed information about the color and

luminosity of the main-sequence stars.

In addition to the cluster physical parameters obtained by

using those tools (e.g. age, distance, extinction,

membership), the polarimetric data allow us study the location, size,

and efficiency of the dust grains to polarize the starlight and the

different directions of the Galactic magnetic field along the line of

sight to the cluster. Since the open clusters are also spread within a

fixed area, we can analyze the evolution in the physical parameters of

the dust all over the region. In this framework, we conduct

systematic polarimetric observations in a large number of Galactic open

clusters.

)

about the dust located in front of a luminous object. Open clusters are

very good candidates for carrying out polarimetric observations,

because previous photometric and spectroscopic studies of these

clusters have provided detailed information about the color and

luminosity of the main-sequence stars.

In addition to the cluster physical parameters obtained by

using those tools (e.g. age, distance, extinction,

membership), the polarimetric data allow us study the location, size,

and efficiency of the dust grains to polarize the starlight and the

different directions of the Galactic magnetic field along the line of

sight to the cluster. Since the open clusters are also spread within a

fixed area, we can analyze the evolution in the physical parameters of

the dust all over the region. In this framework, we conduct

systematic polarimetric observations in a large number of Galactic open

clusters.

As part of this survey, we present a polarimetric

investigation of the open cluster NGC 5617

(C1426-605). It is located at (l =

![]() ,

b =

,

b = ![]() ),

covering a wide area of the sky of about 10

),

covering a wide area of the sky of about 10 ![]() 10 arcmin. In the past it was investigated using

photoelectric and photographic photometry (Lindoff 1968; Moffat &

Vogt 1975; Haug 1978). Kjeldsen

& Frandsen (1991)

and Carraro & Munari (2004)

presented CCD observations covering part of the area.

In this last work deep CCD (BVI) photometry

of the core region was performed to derive more accurate estimates of

the cluster fundamental parameters by observing about

140 stars down to V = 17.5 mag.

The analysis of two adjacent fields covering the central part of the

cluster confirmed a previous mean value of the excess EB-V =

0.48 mag, found in the first of two

CCD investigations, and a distance determination that located

the open cluster at 2.0

10 arcmin. In the past it was investigated using

photoelectric and photographic photometry (Lindoff 1968; Moffat &

Vogt 1975; Haug 1978). Kjeldsen

& Frandsen (1991)

and Carraro & Munari (2004)

presented CCD observations covering part of the area.

In this last work deep CCD (BVI) photometry

of the core region was performed to derive more accurate estimates of

the cluster fundamental parameters by observing about

140 stars down to V = 17.5 mag.

The analysis of two adjacent fields covering the central part of the

cluster confirmed a previous mean value of the excess EB-V =

0.48 mag, found in the first of two

CCD investigations, and a distance determination that located

the open cluster at 2.0 ![]() 0.3 kpc from the Sun.

It is an intermediate-age open cluster (8.2

0.3 kpc from the Sun.

It is an intermediate-age open cluster (8.2 ![]() 107 years) containing red giants and

blue straggler stars (Ahumada & Lapasset 2007) in its

surroundings, whose memberships of the cluster remain

in doubt.

107 years) containing red giants and

blue straggler stars (Ahumada & Lapasset 2007) in its

surroundings, whose memberships of the cluster remain

in doubt.

2 Observations

Observations of the ![]() bands (KC: Kron-Cousins,

bands (KC: Kron-Cousins, ![]() =

0.36

=

0.36 ![]() m,

FWHM = 0.05

m,

FWHM = 0.05 ![]() m;

m; ![]() =

0.44

=

0.44 ![]() m,

FWHM = 0.06

m,

FWHM = 0.06 ![]() m;

m; ![]() =

0.53

=

0.53 ![]() m,

FWHM = 0.06

m,

FWHM = 0.06 ![]() m;

m; ![]() =

0.69

=

0.69 ![]() m,

FWHM = 0.18

m,

FWHM = 0.18 ![]() m;

m; ![]() =

0.83

=

0.83 ![]() m,

FWHM = 0.15

m,

FWHM = 0.15 ![]() m) were carried out using the five-channel

photopolarimeter of the Torino Astronomical Observatory attached to the

2.15 m telescope at the Complejo Astronómico El Leoncito

(CASLEO, Argentina). They were performed over eight nights

(June 27-30, 2006 and

June 15-18, 2007). The instrument allows simultaneous

polarization measurements to be performed in the five bands UBVRI,

and the combination of the dichroic beam splitters and the filters

cemented to the field lenses of the dichroic filters set closely

matches the standard UBVRI system. The

FOTOR polarimeter provides the possibility of using

5 different diaphragm apertures to measure the stars, of sizes

between 19.2 arcsec and 5.6 arcsec.

As usual, the same diaphragm was used to measure the star and

the closest portion of sky. During each observing run, a set

of standard stars to determine null polarization and the zero point of

the polarization position angle (taken from Clocchiatti &

Marraco 1988)

was observed to determine both the instrumental polarization and the

coordinate transformation into the equatorial system, respectively. The

net polarization of telescope and instrument, typically of about

0.01 percent, was subtracted from all the data. For additional

information about the instrument, data acquisition, and data reduction,

we refer to Scaltriti et al. (1989) and

Scaltriti (1994).

m) were carried out using the five-channel

photopolarimeter of the Torino Astronomical Observatory attached to the

2.15 m telescope at the Complejo Astronómico El Leoncito

(CASLEO, Argentina). They were performed over eight nights

(June 27-30, 2006 and

June 15-18, 2007). The instrument allows simultaneous

polarization measurements to be performed in the five bands UBVRI,

and the combination of the dichroic beam splitters and the filters

cemented to the field lenses of the dichroic filters set closely

matches the standard UBVRI system. The

FOTOR polarimeter provides the possibility of using

5 different diaphragm apertures to measure the stars, of sizes

between 19.2 arcsec and 5.6 arcsec.

As usual, the same diaphragm was used to measure the star and

the closest portion of sky. During each observing run, a set

of standard stars to determine null polarization and the zero point of

the polarization position angle (taken from Clocchiatti &

Marraco 1988)

was observed to determine both the instrumental polarization and the

coordinate transformation into the equatorial system, respectively. The

net polarization of telescope and instrument, typically of about

0.01 percent, was subtracted from all the data. For additional

information about the instrument, data acquisition, and data reduction,

we refer to Scaltriti et al. (1989) and

Scaltriti (1994).

Table 1

lists the 72 stars observed polarimetrically in the direction

of the open cluster, the percentage polarization (

![]() ), the position angle of the

electric vector (

), the position angle of the

electric vector (

![]() )

in the equatorial coordinate system, and their respective mean errors

for each filter. We also indicate the number of 60 s

integrations for each filter. Star identifications are taken from Haug (1978).

)

in the equatorial coordinate system, and their respective mean errors

for each filter. We also indicate the number of 60 s

integrations for each filter. Star identifications are taken from Haug (1978).

Table 1: Polarimetric observations of stars in NGC 5617.

3 Results

The sky projection of the V-band polarization

vectors for the observed stars in NGC 5617 are shown in

Fig. 1.

The cluster spreads over a large region covering more than 10 ![]() 10 arcmin. The dotted line superimposed on the figure is the

Galactic parallel of b = -0

10 arcmin. The dotted line superimposed on the figure is the

Galactic parallel of b = -0

![]() 2

In this plot we observe that most of the stars have their polarimetric

vectors orientated in a direction close to the projection of the

Galactic Plane (hereafter GP) in that region, but a close

inspection of the angle distribution displays a complex structure.

2

In this plot we observe that most of the stars have their polarimetric

vectors orientated in a direction close to the projection of the

Galactic Plane (hereafter GP) in that region, but a close

inspection of the angle distribution displays a complex structure.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{13171fig1.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13171-09/Timg33.png)

|

Figure 1:

Projection on the sky of the polarization vectors (Johnson V filter)

of the stars observed in the region of NGC 5617. The

dot-dashed line is the Galactic parallel |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=-90,width=9cm,clip]{13171fig2.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13171-09/Timg34.png)

|

Figure 2:

Upper plot: V band polarization percentage of the

stellar flux |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Figure 2

(upper plot) shows the relation that exists between PV

and

![]() .

We can see a core of stars at PV

.

We can see a core of stars at PV ![]() 4%

and

4%

and ![]()

![]() 76

76![]() ,

and some scatter toward lower angles and polarizations. This could be

the result of a patchy dust distribution that produces variable

extinction, or the contamination by non-member stars with

polarizations originated in dust clouds other than those affecting the

light from NGC 5617. Unfortunately, papers based on

CCD data did not perform a membership analysis of individual

stars in the region so as to help disclose this point. What can clearly

be seen in this figure is that the orientation of the Galactic plane is

similar to the orientation of the low polarization stars (

,

and some scatter toward lower angles and polarizations. This could be

the result of a patchy dust distribution that produces variable

extinction, or the contamination by non-member stars with

polarizations originated in dust clouds other than those affecting the

light from NGC 5617. Unfortunately, papers based on

CCD data did not perform a membership analysis of individual

stars in the region so as to help disclose this point. What can clearly

be seen in this figure is that the orientation of the Galactic plane is

similar to the orientation of the low polarization stars (![]() 2%), but

this is not so for the stars in that core (

2%), but

this is not so for the stars in that core (![]() 4%). This behavior is more clearly displayed by

the histogram of the observed angles (lower plot). There is a peak

around 75

4%). This behavior is more clearly displayed by

the histogram of the observed angles (lower plot). There is a peak

around 75![]() ,

but also a large scatter toward lower angles and a moderate scatter to

the opposite side. The dashed line is a Gaussian fit to the data, which

provides a poor fit. The data for the peak region exhibit a narrow and

concentrated distribution, but a component that is broader than the

best-fit Gaussian of the data. This can be easily explained if each

component, the concentrated peak and the more widely spread data, have

different origins. The narrow component has the empirical regular shape

found in other clusters (e.g., in NGC 6193, NGC 6167,

NGC 6204, Hogg 22, Stock 16,

Trumpler 27; from Waldhausen et al. 1999; Martínez

et al. 2004;

Feinstein et al. 2000,

2003,

respectively) where the FWHM has values

between 8 and 16 degrees, which seem to be compatible

with the core width.

,

but also a large scatter toward lower angles and a moderate scatter to

the opposite side. The dashed line is a Gaussian fit to the data, which

provides a poor fit. The data for the peak region exhibit a narrow and

concentrated distribution, but a component that is broader than the

best-fit Gaussian of the data. This can be easily explained if each

component, the concentrated peak and the more widely spread data, have

different origins. The narrow component has the empirical regular shape

found in other clusters (e.g., in NGC 6193, NGC 6167,

NGC 6204, Hogg 22, Stock 16,

Trumpler 27; from Waldhausen et al. 1999; Martínez

et al. 2004;

Feinstein et al. 2000,

2003,

respectively) where the FWHM has values

between 8 and 16 degrees, which seem to be compatible

with the core width.

We understand that the most likely explanation of this

behavior is that the sample is contaminated by non-member stars of

lower polarization and angle that are similar stars to those of

the GP. Although it is a statistically marginal result,

the lower angle stars appear to be more numerous when the

projected distance from the cluster's center increases. Carraro

& Munari (2004)

support this idea by showing that if they consider only stars inside a

radius smaller than or equal to 2

![]() 2,

a clean main sequence is obtained, since most of the

non-member stars are eliminated from their sample.

2,

a clean main sequence is obtained, since most of the

non-member stars are eliminated from their sample.

4 Analysis and discussion

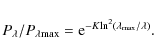

4.1 Fitting with Serkowski's law

To analyze the data, the polarimetric observations in the five filters

were fitted for each star using Serkowski's law of

interstellar polarization (Serkowski 1973) given by

|

(1) |

If polarization is produced by aligned interstellar dust particles, then we assume that, the observed data (in terms of wavelength within the bands UBVRI) can be reproduced accurately by Eq. (1) and that each star has a separate

To perform the fitting, we adopted ![]() ,

where

,

where

![]() is in

is in ![]() m

(Whittet et al. 1992).

For each star, we also computed the

m

(Whittet et al. 1992).

For each star, we also computed the ![]() parameter

(the unit weight error of the fit) in order to

quantify the departure of our data from the ``theoretical curve'' of

the Serkowski's law. In our scheme, when a star

exhibits

parameter

(the unit weight error of the fit) in order to

quantify the departure of our data from the ``theoretical curve'' of

the Serkowski's law. In our scheme, when a star

exhibits ![]() this is indicative of a non-interstellar origin (that is,

an intrinsic polarization) in part of the measured

polarization. The dominant source of intrinsic polarization is dust

non-spherically distributed and, for classical

Be stars, electron scattering. The

this is indicative of a non-interstellar origin (that is,

an intrinsic polarization) in part of the measured

polarization. The dominant source of intrinsic polarization is dust

non-spherically distributed and, for classical

Be stars, electron scattering. The

![]() values can also be

used to test the origin of the polarization: objects with a

values can also be

used to test the origin of the polarization: objects with a

![]() much shorter than the average value for the interstellar medium

(0.55

much shorter than the average value for the interstellar medium

(0.55 ![]() ,

Serkowski et al. 1975)

are also likely to contain an intrinsic component of polarization

(Orsatti et al. 1998).

The individual

,

Serkowski et al. 1975)

are also likely to contain an intrinsic component of polarization

(Orsatti et al. 1998).

The individual

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

and

,

and ![]() values, together

with the star identification from Haug (1978),

are listed in Table 2.

We excluded five stars with

values, together

with the star identification from Haug (1978),

are listed in Table 2.

We excluded five stars with ![]() higher than 15

higher than 15![]() :

#58, 69, 137, 149, and 255. The mathematical expression used

to obtain the individual

:

#58, 69, 137, 149, and 255. The mathematical expression used

to obtain the individual ![]() values

is found in this table as a footnote.

values

is found in this table as a footnote.

Table 2: Polarization results of stars in direction to NGC 5617.

According to Table 2,

only 10 of the 67 stars exhibit signatures of

intrinsic polarization: #154, 260, 270,

and 274 (a group with very high

![]() ); #146, 330,

and 333 (with lower values): and also two blue stragglers

(#195, #261) and the red giant #227.

Star 226 has

); #146, 330,

and 333 (with lower values): and also two blue stragglers

(#195, #261) and the red giant #227.

Star 226 has ![]() = 1.91

but this value was estimated using data for only 3 filters,

so the detection of intrinsic polarization in the star is

dubious. The use of the second criterion to detect intrinsic stellar

polarization did not provide new candidates. Figure 3 shows, for some of

these stars, both the polarization and position angle dependence on

wavelength. For comparison purposes, the best fit

Serkowski's law for an interstellar origin of the polarization

has been plotted as a continuous line. In the individual

plots, the

= 1.91

but this value was estimated using data for only 3 filters,

so the detection of intrinsic polarization in the star is

dubious. The use of the second criterion to detect intrinsic stellar

polarization did not provide new candidates. Figure 3 shows, for some of

these stars, both the polarization and position angle dependence on

wavelength. For comparison purposes, the best fit

Serkowski's law for an interstellar origin of the polarization

has been plotted as a continuous line. In the individual

plots, the ![]() values

do not appear to fit this law and in some cases

(e.g., #227, #261) there is evidence of a combination

of two different polarization mechanisms. Most of the stars in the

figure also show important rotations of the polarization position angle

with

values

do not appear to fit this law and in some cases

(e.g., #227, #261) there is evidence of a combination

of two different polarization mechanisms. Most of the stars in the

figure also show important rotations of the polarization position angle

with ![]() .

.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{13171fig3.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13171-09/Timg51.png)

|

Figure 3: The plot displays both the polarization and position angle dependence on wavelength, for some of the stars with indications of intrinsic polarization. The numbers in the polarization dependence plots are the star ID, and immediately below is the position angle dependence for each star. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

4.2 The Qv versus Uv plot and membership review

The identification of members in a cluster is important, not only to distance and age determinations but also other studies such as those of stellar content and metallicity. In NGC 5617, as in many other clusters, probable cluster members were identified as those stars simultaneously having reconcilable positions in both color-color and color-magnitude diagrams.

Several errors in membership assignment are possible using this kind of photometric approach, for example when dealing with photographic photometry, in particular the U-measures; and when studying intermediate-age clusters, where the evolved stars could not be located close to the ZAMS. In our cluster, the CCD plates of Kjeldsen & Frandsen (1991) and Carraro & Munari (2004) cover only the central region of the cluster, and for stars in the vicinities of the core only photographic measurements are possible. In addition, as found by these last authors, stars brighter than 12.5 mag are evolving away from the main sequence. Evolved members and background stars become mixed close to the ZAMS in the color-magnitude diagrams, and in this case the photometric identification of cluster members becomes difficult.

The polarimetric technique can help us to solve membership

problems. Different plots used in combination with photometric

information can be useful for separating between members and

non-members. One of those plots presents the Stokes parameters Qv versus Uv

for the V-bandpass, where ![]() and

and ![]() are the components in the equatorial system of the polarization

vector Pv,

is shown in Fig. 4.

The plot illustrates the variations occurring in interstellar

environments. Since the light from cluster members must have traversed

a common sheet of dust, of particular polarimetric characteristics, the

member data points should occupy similar regions of the figure.

Non-member stars (frontside and background stars) should be located in

the Qv versus Uv

figure somewhat apart from the region occupied by member stars, since

their light must have traveled through different dust clouds from those

affecting the light of member stars, of different polarimetric

characteristics.

are the components in the equatorial system of the polarization

vector Pv,

is shown in Fig. 4.

The plot illustrates the variations occurring in interstellar

environments. Since the light from cluster members must have traversed

a common sheet of dust, of particular polarimetric characteristics, the

member data points should occupy similar regions of the figure.

Non-member stars (frontside and background stars) should be located in

the Qv versus Uv

figure somewhat apart from the region occupied by member stars, since

their light must have traveled through different dust clouds from those

affecting the light of member stars, of different polarimetric

characteristics.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{13171fig4.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13171-09/Timg54.png)

|

Figure 4: Q- and U-Stokes parameters for the V bandpass. Filled and open circles are for members and non-members, respectively. Starred points represent blue straggler stars, and squares red giants. Small symbols are used for stars with intrinsic polarization according to Table 2. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

The basic principle behind the use of polarimetry as a criterion for distinguishing members from non-members in a cluster is similar to that used in photometry to decide membership. The procedure is based on the assumption that member stars are located behind common dust clouds that polarize their light, while this is not valid for most non-member stars.

Objects closer to the Sun, or located along the line of sight to the cluster, will have lower EB-V and their light will be less polarized. If there are clouds between these stars and ourselves, and dust is orientated in a different direction, the final angle will not be the same as for the cluster's stars. In the Q versus U plot, these stars therefore are located in different regions.

For stars located behind the cluster, the individual polarizations could be higher than those associated with the cluster if the dust has the same orientation, or it could be depolarized if the orientation is not the same. However, in both cases the location in the diagram Q-U will not be the same as that for the cluster's stars. And in the last case, the EB-V of those stars will be higher and detectable in the efficiency diagram (Pv versus EB-V).

For example, the polarimetry became a very useful membership identification tool for stars belonging to the clusters NGC 6204 and Hogg 22, the last one located behind the first cluster.

Stars of each object occupy different regions of the Q versus U diagram (see Fig. 6 of Martínez et al. 2003), and since Hogg 22 is depolarized and has a higher EB-V's, both clusters are separated in the polarization efficiency diagram (Fig. 5 of that work).

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{13171fig5.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13171-09/Timg55.png)

|

Figure 5: Polarization efficiency diagram. The line of maximum efficiency is drawn adopting Rv = 3.1. Symbols are the same as in Fig. 4. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

In using polarimetry to decide memberships, we are able to use information in the literature derived using alternative methods (e.g., photometric, spectroscopic, proper motions) and we can determine in the Q - U and Pv versus EB-V plots the regions where cluster and non-member stars are located. Because of previous considerations, we accept at first that any star in the non-member region is a very probable non-member and in the same way, any star located in the cluster region is also a very probable member of the cluster. We note that we do not apply this criterion to stars with detected intrinsic polarization for which we can only assign a dubious membership. Because this tool has been used in previous work, our opinion is that polarimetry can be as useful as photometry to identifications or, in most of the cases, a very useful complement.

Members identified by applying this method are shown in both Figs. 4 and 5 using filled (for member) and open (for non-member) symbols. Circles are used for stars, squares for supergiants, and starred points for blue stragglers. Small symbols of any kind denote stars with intrinsic polarization. We could add an important number of new members to the previous list, and we have also been able to review the situation for other stars listed in the photometric investigations. The last column of Table 2 lists our conclusions.

In particular, five of the observed blue straggler stars are

behind the dust located in front of the member stars, but #195

may be a possible member because of its position in the Qv versus

Uv plot.

As mentioned in the previous section, intrinsic polarization

was detected for the star that could explain the position in

Fig. 4.

We also confirmed that the red giants #116 and 227

are members of the open cluster, as asserted in the literature.

To compare our proposed polarimetric memberships with those

coming from other methods, we used the works of Mermilliod

et al. (2008)

and Frinchaboy & Majewski (2008).

In the first investigation, radial velocities of giant stars

in the region of a cluster are compared with the cluster mean velocity

to assign membership. We have four red giants in common with that

study (#55, 116, 227, 347) and our membership results are in

agreement. In the second investigation, the star proper motion

(from Hipparcos and Tycho-2 catalogues), radial velocity, and

spatial distribution are combined to detect cluster members. Among a

group of seven stars in common (#55, 116, 180, 202, 227, 342,

347), there are membership discrepancies for only star #202 (

![]() = 4.83

= 4.83![]() ,

,

![]() = 76

= 76

![]() ),

for which they find a probability of 51.2

),

for which they find a probability of 51.2![]() on the basis of its radial velocity but a 0

on the basis of its radial velocity but a 0![]() probability

using the proper motions. According to both Figs. 4 and 5, the star

appears to be located behind the same sheet of dust as the remaining

members, and for that we consider the star as a member, as the

photometric plots suggest. Column 6 in Table 2 lists the

memberships determined in these two works.

probability

using the proper motions. According to both Figs. 4 and 5, the star

appears to be located behind the same sheet of dust as the remaining

members, and for that we consider the star as a member, as the

photometric plots suggest. Column 6 in Table 2 lists the

memberships determined in these two works.

In Fig. 4,

stars #187, 270, and 333 are located far away from the member group.

The first star is considered to be part of the cluster by some

photometric studies but no membership information is provided by

Mermilliod et al. (2008),

Frinchaboy & Majewski (2008),

or Dias et al. (2006).

The

![]() is not indicative of abnormal polarization as to justify its position

in the plot; and it can be seen in Fig. 5 that it has

a low polarization relative to the remaining members. We

propose that #187 is a frontside star, observed projected onto

the central core of NGC 5617. The other two

stars (#270 and 333) both display intrinsic

polarization as mentioned in the following section.

is not indicative of abnormal polarization as to justify its position

in the plot; and it can be seen in Fig. 5 that it has

a low polarization relative to the remaining members. We

propose that #187 is a frontside star, observed projected onto

the central core of NGC 5617. The other two

stars (#270 and 333) both display intrinsic

polarization as mentioned in the following section.

To derive mean values of polarization and polarization angle,

we used 16 stars with similar Stokes parameters and free of

intrinsic polarization: #79, 80, 93, 94, 100, 106, 116, 169,

180, 185, 186, 214, 225, 276, 294, and 302. We obtained ![]() = 4.40

= 4.40![]() and

and ![]() = 73

= 73

![]() 1

1 ![]() 0.9

(both of them being the mean values for all 16). The

mean

0.9

(both of them being the mean values for all 16). The

mean

![]() amounts to 0.53

amounts to 0.53 ![]() 0.03

0.03 ![]() m, the value

associated with the ISM.

m, the value

associated with the ISM.

4.3 Polarization efficiency

It is known that for the interstellar medium the polarization

efficiency (ratio of the maximum amount of polarization to visual

extinction) rarely exceeds the empirical upper limit,

| (2) |

obtained for interstellar dust particles (Hiltner 1956). The polarization efficiency indicates how much polarization is obtained for a certain amount of extinction and depends mainly on both the alignment efficiency and the magnetic field strength, and also on the amount of depolarization due to radiation traversing more than one cloud with different field directions.

Figure 5

shows the plot of ![]() vs. EB-V.

The individual excesses EB-V

were obtained either from the literature or by dereddening the colors

and using the relationship between either spectral type and color

indexes (Schmidt-Kaler 1982).

For stars with only photographic UBV

measures, the calculated excesses may well be in error.

vs. EB-V.

The individual excesses EB-V

were obtained either from the literature or by dereddening the colors

and using the relationship between either spectral type and color

indexes (Schmidt-Kaler 1982).

For stars with only photographic UBV

measures, the calculated excesses may well be in error.

It can be seen that, apart from five stars (from top to

bottom: #333, 294, 261, 136, and 269), the remainder are

located to the right of the interstellar maximum line, indicating that

their polarizations are mostly due to the ISM. Star #333 has

intrinsic polarization in Table 2 and, based on its

position in the plot, we understand it to be a background star.

Star #294, the second from top, has no evident indications of

abnormal polarization in its light and we could not find any suitable

explanation of the position in this figure. Most probably, the excess

(calculated from photographic photometry) is affected by error.

Stars # 261 (a blue struggler) and #136 are

affected by intrinsic polarization as shown in Table 2; with respect to

star #269, the calculated excess may well also be affected

by error. As in Fig. 4, the two

stars #187 and 333 are shown here as non-members. But

regarding #270, we accept that this star is a member, beacuse

even when its polarization includes an intrinsic part,

its position in Fig. 5

matches those of the member stars, and its

![]() and

and ![]() values (4.31

and 73

values (4.31

and 73

![]() 4,

respectively) are coincident with the mean values for members.

To calculate the polarization efficiency, we selected a group

of 15 stars with Pv

in the range from 4.20

4,

respectively) are coincident with the mean values for members.

To calculate the polarization efficiency, we selected a group

of 15 stars with Pv

in the range from 4.20![]() to 4.95

to 4.95![]() ,

and obtained a polarization efficiency of about 2.44, which is

lower than the standard value for the interstellar dust

(of about 5). This value indicates a very high

efficiency of the dust that polarizes the light from the cluster stars.

,

and obtained a polarization efficiency of about 2.44, which is

lower than the standard value for the interstellar dust

(of about 5). This value indicates a very high

efficiency of the dust that polarizes the light from the cluster stars.

Neckel & Klare (1980)

computed the interstellar extinction values and distances of more than

11 000 O to F stars in the

Milky Way. Their figure #174 (314![]() , 0

, 0![]() )

shows the variation in Av

with increasing distance in the area of NGC 5617, starting

at 1 kpc and showing that the absorption takes values

of between 1.2 and 2.4 mag at the position of the

cluster, in good agreement with the Av

calculated from (2) for a

)

shows the variation in Av

with increasing distance in the area of NGC 5617, starting

at 1 kpc and showing that the absorption takes values

of between 1.2 and 2.4 mag at the position of the

cluster, in good agreement with the Av

calculated from (2) for a

![]() of 4.4

of 4.4![]() .

The nearest of our stars to the Sun is #187 (non-member) with

a Pv = 1.83

.

The nearest of our stars to the Sun is #187 (non-member) with

a Pv = 1.83![]() and a distance of about 1.2 kpc from us, which it implies that

is not in the Local but in the Carina-Sagittarius arm,

in addition to the remaining non-members and the cluster

itself. As can be seen in Fig. 5, there is a scatter

in polarization values for the members of NGC 5617, which

could be caused by either intracluster dust or the uneven distribution

of dust in front of the cluster's face, as seen in any plate of the

object. Since NGC 5617 is an intermediate-age open cluster

(8.2

and a distance of about 1.2 kpc from us, which it implies that

is not in the Local but in the Carina-Sagittarius arm,

in addition to the remaining non-members and the cluster

itself. As can be seen in Fig. 5, there is a scatter

in polarization values for the members of NGC 5617, which

could be caused by either intracluster dust or the uneven distribution

of dust in front of the cluster's face, as seen in any plate of the

object. Since NGC 5617 is an intermediate-age open cluster

(8.2 ![]() 107 yr),

we favor the second explanation of the scatter.

107 yr),

we favor the second explanation of the scatter.

5 Summary

We have measured the linear multicolor polarization of 72 stars in the region of the open cluster NGC 5617. By analyzing all of these data, we have found that between the Sun's position and the Carina-Sagittarius arm, there is a large region of transparency and that NGC 5617 is located deep inside the arm, or even at its farthest border. In addition, we have found the polarimetric efficiency of the dust in front of the cluster to be very high relative to the mean value attributed to the ISM.

Polarimetry has proven to be an excellent tool in the task of membership identification. It has been employed in previous investigations where the main goal was the determination of general characteristics of the cluster rather than the precise assessment of membership. The identification studies of members and non-members now typically covers a wider area of the cluster and reaches fainter magnitudes. A comparison of the polarimetric and kinematical memberships of stars in common with other investigations, has confirmed that the polarimetric observations could help resolve these issues.

This research has made use of the WEBDA database, operated at the Institute for Astronomy of the University of Vienna. We wish to acknowledge the technical support and hospitality at CASLEO during the observing runs. We also acknowledge the use of the Torino Photopolarimeter built at Osservatorio Astronomico di Torino (Italy) and operated under agreement between Complejo Astronómico El Leoncito and Osservatorio Astronomico di Torino. We thanks the anonymous referee for the help to improve the paper. Special thanks go to Dr. Hugo G. Marraco for his useful comments and also to Mrs. M. C. Fanjul de Correbo for the technical assistance.

References

- Ahumada, J., & Lapasset, E. 2007, A&AS, 463, 789 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Carraro, G., & Munari, U. 2004, MNRAS, 347, 625 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Clocchiatti, A., & Marraco, H. G. 1988, A&A, 197, L1 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Dias, W. S., Assafin, M., Florio, V., Alessi, B. S., & Libero, V. 2006, A&A, 446, 949 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein, C., Baume, G., Vázquez, R., Niemela, V., & Cerruti, M. A. 2000, AJ, 120, 1906 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein, C., Baume, G., Vergne, M. M., & Vázquez, R. 2003, A&A, 409, 933 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Frinchaboy, P. M., & Majewski, S. R. 2008, AJ, 136, 118 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Haug, U. 1978, A&AS, 34, 417 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Hiltner, W. A. 1956, ApJS, 2, 389 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kjeldsen, H., & Frandsen, S. 1991, A&AS, 87, 119 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Lindoff, U. 1968, Ark. Astr., 4, 471 [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, R., Vergne, M. M., & Feinstein, C. 2004, A&A, 419, 965 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Mermilliod, J. C., Mayor, M., & Udry, S. 2008, A&A, 485, 303 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Moffat, A. F. J., & Vogt, N. 1975, A&AS, 20, 155 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Neckel, Th., & Klare, G. 1980, A&A, 42, 251 [Google Scholar]

- Orsatti, A. M., Vega, E. I., & Marraco, H. G. 1998, AJ, 116, 266 [Google Scholar]

- Scaltriti, F. 1994, Technical Publication No. TP-001, Osservatorio Astronomico di Torino [Google Scholar]

- Scaltriti, F., Piirola, V., Cellino, A., et al. 1989, Mem. S. A. It, 60, 1 [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt-Kaler, Th. 1982, in Landolt/Bornstein, Neue Series VI/2b [Google Scholar]

- Serkoswki, K. 1973, in Interstellar Dust and Related Topics, ed. J. M. Greenberg, & H. C. van der Hulst (Dordrecht-Holland: Reidel), IAU Symp., 52, 145 [Google Scholar]

- Serkowski, K., Mathewson, D. L., & Ford, V. L. 1975, ApJ, 196, 261 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Waldhausen, S., Martínez, R. E., & Feinstein, C. 1999, AJ, 117, 2882 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Whittet, D. C. B., Martin, P. G., Hough, J. H., et al. 1992, ApJ, 386, 562 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Footnotes

- ... 5617

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- Based on observations obtained at Complejo Astronómico El Leoncito, operated under agreement between the Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas de la República Argentina and the Universities of La Plata, Córdoba, and San Juan.

All Tables

Table 1: Polarimetric observations of stars in NGC 5617.

Table 2: Polarization results of stars in direction to NGC 5617.

All Figures

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{13171fig1.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13171-09/Timg33.png)

|

Figure 1:

Projection on the sky of the polarization vectors (Johnson V filter)

of the stars observed in the region of NGC 5617. The

dot-dashed line is the Galactic parallel |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=-90,width=9cm,clip]{13171fig2.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13171-09/Timg34.png)

|

Figure 2:

Upper plot: V band polarization percentage of the

stellar flux |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{13171fig3.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13171-09/Timg51.png)

|

Figure 3: The plot displays both the polarization and position angle dependence on wavelength, for some of the stars with indications of intrinsic polarization. The numbers in the polarization dependence plots are the star ID, and immediately below is the position angle dependence for each star. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{13171fig4.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13171-09/Timg54.png)

|

Figure 4: Q- and U-Stokes parameters for the V bandpass. Filled and open circles are for members and non-members, respectively. Starred points represent blue straggler stars, and squares red giants. Small symbols are used for stars with intrinsic polarization according to Table 2. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{13171fig5.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13171-09/Timg55.png)

|

Figure 5: Polarization efficiency diagram. The line of maximum efficiency is drawn adopting Rv = 3.1. Symbols are the same as in Fig. 4. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

Copyright ESO 2010

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.