| Issue |

A&A

Volume 513, April 2010

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A9 | |

| Number of page(s) | 13 | |

| Section | Interstellar and circumstellar matter | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/200912241 | |

| Published online | 14 April 2010 | |

A millimeter survey of ultra-compact

HII-regions and associated molecular clouds![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

E. Churchwell1 - A. Sievers2 - C. Thum3

1 - Department of Astronomy, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 475 N.

Charter street, Madison, WI 53706, USA

2 - Instituto de Radio Astronomía Milimétrica, Avenida Divina Pastora,

7 Núcleo Central, 18012 Granada, Spain

3 - Institut de Radio Astronomie Millimétrique, Domaine Universitaire

de Grenoble, 300 rue de la Piscine, 38406 Saint Martin d'Hères, France

Received 1 April 2009 / Accepted 18 November 2009

Abstract

We report observations, using the IRAM 30 m telescope,

of 30 ultracompact and hypercompact

HII regions in the lines of HCO+(3-2)

and/or HCO+(1-0) and H![]() and/or H

and/or H![]() .

Images are presented in both HCO+(3-2) and H

.

Images are presented in both HCO+(3-2) and H![]() toward a subset of regions (16 in HCO+(3-2),

14 in H

toward a subset of regions (16 in HCO+(3-2),

14 in H![]() )

with a resolution of 12''. In addition, H13CO+(3-2)

observations are reported toward 13 HII regions where

HCO+(3-2) displays complex profiles.

It is shown that the absorption dips in the HCO+ profiles

are due to HCO+ self-absorption, not absorption

of the HII free-free emission or warm dust emission

surrounding the HII region or two velocity components along

the line of sight. It was found that among the sources with

self-absorbed profiles, 8 are contracting and 5 are

expanding. Mass fluxes are found to be typically a few times 10-3

)

with a resolution of 12''. In addition, H13CO+(3-2)

observations are reported toward 13 HII regions where

HCO+(3-2) displays complex profiles.

It is shown that the absorption dips in the HCO+ profiles

are due to HCO+ self-absorption, not absorption

of the HII free-free emission or warm dust emission

surrounding the HII region or two velocity components along

the line of sight. It was found that among the sources with

self-absorbed profiles, 8 are contracting and 5 are

expanding. Mass fluxes are found to be typically a few times 10-3 ![]() yr-1,

implying

time scales for massive star formation <105 yrs.

HCO+ and H2 column

densities are estimated for a subset of the sources from which masses

of the dense central cloud cores were

estimated. Implications of the derived column densities, masses, flow

velocities, and mass fluxes are discussed.

yr-1,

implying

time scales for massive star formation <105 yrs.

HCO+ and H2 column

densities are estimated for a subset of the sources from which masses

of the dense central cloud cores were

estimated. Implications of the derived column densities, masses, flow

velocities, and mass fluxes are discussed.

Key words: surveys - stars: formation - HII regions

1 Introduction

Ultra-compact (UC) HII regions are sites of recent massive star formation. UC HII regions are of special interest because they occupy an important stage in the evolution of young massive stars that is still only understood in broad outline. Identifying the ionizing star(s) and their associated natal cluster of lower mass stars in UC HII regions has proven quite difficult; identifications have been reported for only a few UC HII regions. The immediate regions around the central star(s) of UC HII regions are expected to be very dynamic due to possible infall, outflows, stellar winds, accretion disk rotation, turbulence, and shocks. The dynamics and physical properties of the photo-dissociation regions (PDRs) that surround UC HII regions and the ambient natal molecular gas that surrounds the PDRs must also be included to place UC HII regions in context with their environments. Spectroscopy of the H+, PDR(H0), and molecular envelopes (H2) is essential to understand the interactions of UC HII regions with their environments. Churchwell (2002) has argued, based on the lack of evidence for outflows in high resolution radio continuum images, that by the time young massive stars have formed UC HII regions they have largely ceased the accretion process. This is indirect evidence that has so far not been confirmed by spectroscopic observations. To understand the early evolution of massive stars and how they impact their environments, we must determine at what evolutionary stage young massive stars quench accretion and by what mechanism. Is it because the stars use all the matter in their neighborhood or the central radiation pressure over-powers gravity, or some other reason?

We also need to better understand the extent, morphology, and physical properties of the dense molecular and ionized gas in the immediate neighborhood of UC HII regions. Several papers have been published that address one or more of these issues toward specific UC HII regions (some of which are Baudry et al. (1981); Bourke et al. (1997); Cesaroni et al. (1991, 1994, 1998); Choi et al. (1993); Fey et al. (1992); Garay et al. (2007); Sandell & Sievers (2004); Zhu et al. (2008) and references therein), but a sensitive survey is not available that specifically probes both the dense molecular and ionized gas toward a substantial sample of UC HII regions with the same spatial resolution using a single-dish millimeter-wave telescope (i.e. sensitive to all scale sizes within the mapped area).

Here, we present observations of HCO+(3-2)

and/or (1-0) and H![]() and/or H

and/or H![]() lines

toward 29 UC HII regions. The H

lines

toward 29 UC HII regions. The H![]() and/or HCO+(1-0) observations in the

3 mm band were made only toward the central positions of

7 UC HII regions. The HCO+(3-2)

and H

and/or HCO+(1-0) observations in the

3 mm band were made only toward the central positions of

7 UC HII regions. The HCO+(3-2)

and H![]() lines

in the 1 mm band were mapped toward 23 UC

HII regions (see Table 1). The

1 mm observations, we believe, represent a large enough sample

to begin to address systematics of the relationship between the ionized

gas and the surrounding molecular gas. Among these are:

is there systematic evidence for infall of molecular gas

toward UC HII regions? Is there evidence for

excessive line widths in the molecular or ionized gas and,

if so, what is the likely reason? Based on kinematic distance

determinations, is there evidence for a temperature gradient with

galactocentric radius? That is, are UC HII region

temperatures consistent with the observed metallicity gradients

(Churchwell & Walmsley 1975;

Shaver et al. 1983;

Maciel & Köppen 1994;

Mezger et al. 1979;

Afflerbach et al. 1996;

Afflerbach et al. 1997);

and, are there any systematics associated with the column densities of

HCO+ toward UC HII regions?

lines

in the 1 mm band were mapped toward 23 UC

HII regions (see Table 1). The

1 mm observations, we believe, represent a large enough sample

to begin to address systematics of the relationship between the ionized

gas and the surrounding molecular gas. Among these are:

is there systematic evidence for infall of molecular gas

toward UC HII regions? Is there evidence for

excessive line widths in the molecular or ionized gas and,

if so, what is the likely reason? Based on kinematic distance

determinations, is there evidence for a temperature gradient with

galactocentric radius? That is, are UC HII region

temperatures consistent with the observed metallicity gradients

(Churchwell & Walmsley 1975;

Shaver et al. 1983;

Maciel & Köppen 1994;

Mezger et al. 1979;

Afflerbach et al. 1996;

Afflerbach et al. 1997);

and, are there any systematics associated with the column densities of

HCO+ toward UC HII regions?

In the following we discuss the observations in Sect. 2, the data in Sect. 3, results in Sect. 4, and summary and conclusions in Sect. 5.

Table 1: Target sources and type of observation made.

2 Observations

Table 2: Spectral resolution and bandwidth available with the receiver/backend combinations used.

The bulk of the observations were made during the period of

28 March to 02 April 2006 using the IRAM

30 m telescope located at an altitude of 2850 m near

Granada (Spain). During most of this period the weather was good enough

for observations at 1.3 mm wavelength (

![]() ). We used the multibeam

1.3 mm receiver HERA (Schuster et al. 2004) whose two

orthogonal linearly polarized arrays were tuned to HCO+

at 267.557633 GHz and H

). We used the multibeam

1.3 mm receiver HERA (Schuster et al. 2004) whose two

orthogonal linearly polarized arrays were tuned to HCO+

at 267.557633 GHz and H![]() at 231.900942 GHz. Each array provides 3

at 231.900942 GHz. Each array provides 3 ![]() 3 pixels arranged as a center-filled square. The two arrays

are aligned to within

3 pixels arranged as a center-filled square. The two arrays

are aligned to within ![]() ,

thus permitting precise relative pointing between the two transitions.

Each pixel consists of a diffraction-limited beam of 12'' (FWHP),

and the pixels are separated by 24''. The observations were

made in wobbler-switching mode where the reference positions are offset

in azimuth by 30'' to 120''. The array was kept aligned with

the equatorial system with the help of a derotator optical assembly

that compensates the field rotation due to changes of the parallactic

and Nasmyth angles. Maps sampled at 1/2 FWHP

intervals of size 66''

,

thus permitting precise relative pointing between the two transitions.

Each pixel consists of a diffraction-limited beam of 12'' (FWHP),

and the pixels are separated by 24''. The observations were

made in wobbler-switching mode where the reference positions are offset

in azimuth by 30'' to 120''. The array was kept aligned with

the equatorial system with the help of a derotator optical assembly

that compensates the field rotation due to changes of the parallactic

and Nasmyth angles. Maps sampled at 1/2 FWHP

intervals of size 66'' ![]() 66'' size were obtained by stepping the telescope in

66'' size were obtained by stepping the telescope in ![]() and

and ![]() by 6, 12, and 18''. The 18 signals

generated by HERA were connected to three sets of backends. Their

spectral resolutions and bandwidths are listed

in Table 2.

by 6, 12, and 18''. The 18 signals

generated by HERA were connected to three sets of backends. Their

spectral resolutions and bandwidths are listed

in Table 2.

During a small fraction of our observing time when the weather

was not good enough for 1.3 mm observations, we used the

Observatory's 3 mm single pixel receivers A100

and B100 tuned to H![]() at 106.737363 GHz and HCO+(1-0) at

89.188526 GHz. respectively. The VESPA correlator set to

spectral resolution of 78 kHz (0.26 km s-1

near 100 GHz) and bandwidth

of 140 MHz (480 km s-1

near 100 GHz) was connected to both receivers.

at 106.737363 GHz and HCO+(1-0) at

89.188526 GHz. respectively. The VESPA correlator set to

spectral resolution of 78 kHz (0.26 km s-1

near 100 GHz) and bandwidth

of 140 MHz (480 km s-1

near 100 GHz) was connected to both receivers.

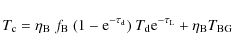

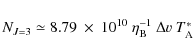

During a second session with the 30 m telescope on 03 August 2008 we observed the H13CO+(3-2) line toward a subset of our target list where the main isotope was found to be very optically thick. HC18O+(3-2) was observed in the few cases where even H13CO+(3-2) did not have a clean gaussian profile. We used the Observatory's single pixel receivers A 230 and B 230 tuned to the line frequencis of 260.25548 (H13CO+(3-2)) and 255.479389 (HC18O+(3-2)) GHz. As representative examples of a weak and a strong source, we show the spectra of the 3 HCO+ isotopes obtained toward G28.20-0.04N and G10.62-0.38 in Fig. 1. Note the presence of a weak SO2 emission line redward of HCO+ in G10.68-0.38. The spectrometers and their spectral characteristics are listed in Table 2.

The telescope beam is 12'' (full width at half power) at

1.3 mm. At the 3 mm transitions it is 26'' at

89 GHz and 24'' at 106 GHz. Pointing

observations were made every 2-3 h on nearby quasars; pointing

errors were found to be ![]() .

Line and continuum measurements are in units of antenna tempertaure,

.

Line and continuum measurements are in units of antenna tempertaure,

![]() ,

calibrated in the usual hot/cold load technique with an estimated

precision of 10%. We use

,

calibrated in the usual hot/cold load technique with an estimated

precision of 10%. We use

![]() to flux density conversion factors of 6.2, 8.6, and

10 Jy/K at 106, 232, and 268 GHz.

to flux density conversion factors of 6.2, 8.6, and

10 Jy/K at 106, 232, and 268 GHz.

Our target sources were taken from various continuum surveys of ultra-compact HII-regions (Wood & Churchwell 1989; Shepherd & Churchwell 1996; Kurtz et al. 1994). We selected those sources which we estimated to have a 1.3 mm continuum flux density in our 12'' beam of at least 100 mJy. We extrapolated the measured 2 cm flux density to 1.3 mm assuming optically thin emission. Any optically thick emission, unrecognized at cm wavelengths, or a significant extended emission, not imaged by the VLA, of a halo surrounding the UCHII region, would increase the expected 1.3 mm flux density.

The observed sources are listed in Table 1. The last

column indicates the type of observations made: either HERA maps of the

HCO+ and H![]() transitions or

pointed observations with the 3 mm single pixel receivers of

the transitions H

transitions or

pointed observations with the 3 mm single pixel receivers of

the transitions H![]() and HCO+(1-0). In the case of maps, the given

positions refer to map centers.

and HCO+(1-0). In the case of maps, the given

positions refer to map centers.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{12241Fig1.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa12241-09/Timg12.png)

|

Figure 1:

Spectra of the |

| Open with DEXTER | |

3 Data

3.1 Ionized gas

We detected recombination lines toward the peaks of 23 out of

30 (77%) of our target sources. Table 3 lists the line

parameters derived from Gaussian fits. The line widths are the full

widths at half power. The H![]() lines are corrected

for instrumental broadening of 3 km s-1.

The H

lines are corrected

for instrumental broadening of 3 km s-1.

The H![]() lines

which were observed with 0.4 km s-1

spectral resolution do not need any such correction. For the sources

where no line was detected we give a

lines

which were observed with 0.4 km s-1

spectral resolution do not need any such correction. For the sources

where no line was detected we give a ![]() upper limit for a

spectral resolution of 2.6 km s-1.

The

upper limit for a

spectral resolution of 2.6 km s-1.

The ![]() km s-1

bandwidth used covers the full velocity range of galactic emission.

km s-1

bandwidth used covers the full velocity range of galactic emission.

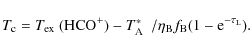

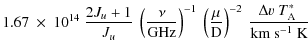

In most cases, the H![]() brightness

distribution is only slightly broadened with respect to the beam.

As an example, Fig. 2 shows the UC

HII-region G10.62-0.38. Maps of the other regions are collected in

Fig. 3.

Linear baselines have been removed from all spectra in the map,

subtracting any free-free emission of the source. Note that the

coverage of these maps is slightly incomplete to the east due to one

bad pixel.

brightness

distribution is only slightly broadened with respect to the beam.

As an example, Fig. 2 shows the UC

HII-region G10.62-0.38. Maps of the other regions are collected in

Fig. 3.

Linear baselines have been removed from all spectra in the map,

subtracting any free-free emission of the source. Note that the

coverage of these maps is slightly incomplete to the east due to one

bad pixel.

Table 3: Recombination line observations.

The H![]() line parameters were mostly derived from the HERA raster maps. The four

positions nearest to the nominal map center have offsets

line parameters were mostly derived from the HERA raster maps. The four

positions nearest to the nominal map center have offsets ![]() and were averaged for the Gaussian fits, corresponding to a beam

smoothed to 14''. The H

and were averaged for the Gaussian fits, corresponding to a beam

smoothed to 14''. The H![]() parameters refer to

a 24'' beam.

parameters refer to

a 24'' beam.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=-90,width=8.3cm,clip]{12241Fig2b.eps}\...

...{2mm}

\includegraphics[angle=-90,width=8.3cm,clip]{12241Fig2a.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa12241-09/Timg17.png)

|

Figure 2:

Maps of G10.62-0.38 obtained with HERA at an angular resolution

of 12'' (circles at lower left corners) in the transitions of H |

| Open with DEXTER | |

In general, the H![]() line is only mildly affected by confusion with molecular lines. The

nearest known molecular transitions, an unidentified line and the

132-122 transition

of CH3C15N,

are -17 and +23 MHz, respectively, away from the

recombination line frequency. It is therefore only the line

wings which may be affected in a few particularly line-rich sources.

These cases are noted in Table 3. The kinematic

distances, given in Col. 6 of this table, are based on the H

line is only mildly affected by confusion with molecular lines. The

nearest known molecular transitions, an unidentified line and the

132-122 transition

of CH3C15N,

are -17 and +23 MHz, respectively, away from the

recombination line frequency. It is therefore only the line

wings which may be affected in a few particularly line-rich sources.

These cases are noted in Table 3. The kinematic

distances, given in Col. 6 of this table, are based on the H![]() LSR velocities assuming an orbital velocity of

220 km s-1. We adopt the IAU

standard distance from the Galactic center of 8.5 kpc,

even if this distance is somewhat larger than that currently

inferred from proper motions (Ghez et al. 2008).

LSR velocities assuming an orbital velocity of

220 km s-1. We adopt the IAU

standard distance from the Galactic center of 8.5 kpc,

even if this distance is somewhat larger than that currently

inferred from proper motions (Ghez et al. 2008).

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=11.6cm,clip]{12241Fig3.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa12241-09/Timg18.png)

|

Figure 3:

H |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=11.6cm,clip]{12241Fig4.eps}

\vspace*{2mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa12241-09/Timg19.png)

|

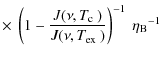

Figure 4: HCO+(3-2) maps obtained with HERA at an angular resolution of 12''. All maps in one row have been plotted using the same contour levels and color scale shown on the right. Contours are in K km s-1, start at and are in steps of 30 (row 1), 15 (row 2), 10 (row 3), 8 (row 4), and 4 (row 5). |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Table 4: HCO+ observations. Isotopes are abbreviated as 12 (HCO+), 13 (H13CO+), and 18 (HC18O+).

3.2 Molecular gas

The molecular clouds toward our target UC HII regions were

detected toward 24 of 28 sources (86%) observed via

their HCO+ emission. We failed to detect HCO+

within 30'' of 5 UC HII regions in our

sample (see Table 4).

In most cases, the HCO+(3-2) emission

is clearly resolved, its extent is in all cases larger than

that of H![]() .

As an example, Fig. 2 shows the UC

HII region G10.62-0.38. Maps of the other regions are

collected in Fig. 4.

.

As an example, Fig. 2 shows the UC

HII region G10.62-0.38. Maps of the other regions are

collected in Fig. 4.

Table 4

lists the main properties of the HCO+ line:

the antenna temperature and radial velocity of the line peak,

the velocity of the self-absorption feature if there is any, and the

line width at 10% of the line peak. This quantity, while

little affected by self-absorption and still well

measurable, gives an indication of the presence of line broadening

mechanisms, like supersonic turbulence or high optical depth. In the

presence of self-absorption, the peak velocity is the measured H13CO+(3-2)

velocity. The measurement errors are typically ![]() K in

K in ![]() and

and ![]() km s-1

for the weaker sources. We also give in Table 4 an estimate of the

size of the HCO+(3-2) core wherever reliable

data were obtained. Elliptical gaussians were fitted to the

velocity-integrated line intensity. The statistical errors of the major

and minor axis are 1'' or less, and less

than 5

km s-1

for the weaker sources. We also give in Table 4 an estimate of the

size of the HCO+(3-2) core wherever reliable

data were obtained. Elliptical gaussians were fitted to the

velocity-integrated line intensity. The statistical errors of the major

and minor axis are 1'' or less, and less

than 5![]() for the position angle.

for the position angle.

As in the case of the recombination lines, the HCO+(3-2) line parameters are derived from the four spectra of the raster maps closest to the nominal map center, and are thus derived for an effective beam of 14''. The HCO+(1-0) parameters refer to a 24'' beam (FWHP).

4 Results

A key goal in the quest to identify protostars that are actually in the

process of accreting mass is to find unequivocal evidence for mass

infall toward the center of molecular clouds. The period of active

accretion is believed to be short, typically

![]() yr

for massive protostars. Consequently, we expect detection of a massive

protostar in the act of rapid accretion to be rare. Several surveys

have been undertaken to search for infall of molecular gas associated

with massive star formation. Among these are Fuller et al. (2005), Purcell

et al. (2006),

Klassen & Wilson (2007),

and Wu et al. (2007).

All of these used HCO+ and H13CO+(3-2)

observations along with a few other molecular probes. The search for

infall, for the most part relied on line profile properties specified

in the Myers et al. (1996)

``two-layer'' model and the sample was mostly toward molecular cores in

cold dark clouds with no bright continuum source such as UC

HII regions. Also, none of the surveys toward massive star

formation regions included simultaneous observations of a radio

recombination line (RRL) at the same spatial resolution,

so the velocities and spatial extent of the molecular gas

could not be compared with those of the associated HII region.

yr

for massive protostars. Consequently, we expect detection of a massive

protostar in the act of rapid accretion to be rare. Several surveys

have been undertaken to search for infall of molecular gas associated

with massive star formation. Among these are Fuller et al. (2005), Purcell

et al. (2006),

Klassen & Wilson (2007),

and Wu et al. (2007).

All of these used HCO+ and H13CO+(3-2)

observations along with a few other molecular probes. The search for

infall, for the most part relied on line profile properties specified

in the Myers et al. (1996)

``two-layer'' model and the sample was mostly toward molecular cores in

cold dark clouds with no bright continuum source such as UC

HII regions. Also, none of the surveys toward massive star

formation regions included simultaneous observations of a radio

recombination line (RRL) at the same spatial resolution,

so the velocities and spatial extent of the molecular gas

could not be compared with those of the associated HII region.

4.1 HCO+ and H30 relative velocities

relative velocities

In this section, we examine the motions of HCO+

relative to H![]() .

The rest frequencies of the lines involved in this comparison are known

to a precision of at least 10 kHz, sufficient for deriving

velocities to a precision of

.

The rest frequencies of the lines involved in this comparison are known

to a precision of at least 10 kHz, sufficient for deriving

velocities to a precision of ![]() km s-1

as needed here. We assume that the velocity of H

km s-1

as needed here. We assume that the velocity of H![]() represents the systemic velocity of the UC HII region. The HCO+

emission distributions are well

correlated with positions of the HII regions

(see Figs. 2-4). The HCO+

emission is generally more extended than that of the H

represents the systemic velocity of the UC HII region. The HCO+

emission distributions are well

correlated with positions of the HII regions

(see Figs. 2-4). The HCO+

emission is generally more extended than that of the H![]() distribution.

Also, HCO+ and H

distribution.

Also, HCO+ and H![]() velocities are

similar, within a few km s-1

(Fig. 5).

This suggests that the HII regions and HCO+

gas are dynamically connected and that the HII regions are

probably embedded in the HCO+ clouds; we assume

that this is the case for all the sources in our sample where we have

both HCO+ and H

velocities are

similar, within a few km s-1

(Fig. 5).

This suggests that the HII regions and HCO+

gas are dynamically connected and that the HII regions are

probably embedded in the HCO+ clouds; we assume

that this is the case for all the sources in our sample where we have

both HCO+ and H![]() images.

images.

Here, we will examine the relative velocities of HCO+

and H![]() emission

to try to determine if the HII regions and molecular clouds

are separating from each other, or are at rest with respect to

each other. Interpretation of the kinematics from the HCO+

and HII velocities is complicated because it depends on how

optically thick the HCO+ line is

(i.e. we are mostly seeing only the nearside of the HCO+ cloud)

and whether the HCO+ profile has an

absorption dip.

emission

to try to determine if the HII regions and molecular clouds

are separating from each other, or are at rest with respect to

each other. Interpretation of the kinematics from the HCO+

and HII velocities is complicated because it depends on how

optically thick the HCO+ line is

(i.e. we are mostly seeing only the nearside of the HCO+ cloud)

and whether the HCO+ profile has an

absorption dip.

Let us now consider the possible scenarios and the

implications for expected HCO+ line

profiles. If the HCO+ line is optically

thin, then we see motions from the entire line of sight.

In this case, if ![]() =

=

![]() ,

the bulk motions of the HII region and molecular

cloud are at rest relative to each other. If

,

the bulk motions of the HII region and molecular

cloud are at rest relative to each other. If

![]() ,

then the molecular cloud and the HII region are in motion

relative to each other, the sense of which depends on the sign of

,

then the molecular cloud and the HII region are in motion

relative to each other, the sense of which depends on the sign of

![]() and v(RRL). However,

and v(RRL). However, ![]() alone

cannot tell us if the molecular cloud is contracting

or expanding.

alone

cannot tell us if the molecular cloud is contracting

or expanding.

As we show in Sect. 4.2 below, the UC HII regions at 1 mm are very optically thin and are too faint to produce detectable absorption in the HCO+ line. This is also supported by the fact that absorption dips in the HCO+ profiles are detected more than a full half-power beam width away from the UC HII positions. Self-absorption, of course, requires that the HCO+ line be optically thick and that its excitation temperature decrease outward.

In the HCO+ optically thick scenario,

we see mostly the front face of the HCO+ cloud.

So a velocity difference between the H![]() and HCO+ lines could imply a relative

velocity between the HII region and the HCO+ cloud,

or contraction or expansion of the outer HCO+ gas

relative to the HII region. That is, we cannot

distinguish between relative bulk motions and contraction or expansion

of HCO+ about the HII region from

comparison of central line velocities. This can be resolved, however,

from line profile analysis using techniques outlined by Myers

et al. (1996)

and generalized by De Vries & Myers (2005).

and HCO+ lines could imply a relative

velocity between the HII region and the HCO+ cloud,

or contraction or expansion of the outer HCO+ gas

relative to the HII region. That is, we cannot

distinguish between relative bulk motions and contraction or expansion

of HCO+ about the HII region from

comparison of central line velocities. This can be resolved, however,

from line profile analysis using techniques outlined by Myers

et al. (1996)

and generalized by De Vries & Myers (2005).

Figure 5

shows the observed velocity difference between the central velocity of

the HCO+ cloud and that of the ionized

region for all sources where both velocities were reliably

observed. Whenever the HCO+ (3-2

or 1-0) line profile was distorted by an absorption

dip within the HCO+ emission profile,

the HCO+ central velocity was

obtained from H13CO+ profiles.

Of the 22 sources toward which both H13CO+(3-2)

and H![]() or both HCO+(1-0) and H

or both HCO+(1-0) and H![]() were detected, the HII region and HCO+ gas

are moving apart at speeds ranging from

were detected, the HII region and HCO+ gas

are moving apart at speeds ranging from ![]() km s-1

up to 9 km s-1; two sources

have relative speeds <0.5 km s-1.

Thus,

km s-1

up to 9 km s-1; two sources

have relative speeds <0.5 km s-1.

Thus, ![]() %

of the sample has significant relative motion between the

HII region and observed HCO+ gas.

%

of the sample has significant relative motion between the

HII region and observed HCO+ gas.

The observed distribution of the velocity differences ![]() may be compared to that expected in a scenario where the ionized gas is

streaming away from the edge of a molecular cloud. Such a scenario was

discussed for the Orion Nebula (Zuckeman 1973) where the

ionized gas happens to stream toward the observer at

may be compared to that expected in a scenario where the ionized gas is

streaming away from the edge of a molecular cloud. Such a scenario was

discussed for the Orion Nebula (Zuckeman 1973) where the

ionized gas happens to stream toward the observer at

![]() km s-1.

Inasmuch as (i) the streaming directions in our

sample sources are random; (ii)

km s-1.

Inasmuch as (i) the streaming directions in our

sample sources are random; (ii) ![]() is the same for all sources; and (iii)

is the same for all sources; and (iii)

![]() is a good representation of

the velocity of the molecular material,

we expect a distribution of velocity differences, projected on

the line-of-sight,

is a good representation of

the velocity of the molecular material,

we expect a distribution of velocity differences, projected on

the line-of-sight, ![]() that

is flat between

that

is flat between ![]()

![]() .

Given the uncertainties due to the small size of our sample, this

scenario may well be what we see in Fig. 5. Nevertheless,

a small bias toward positive velocity differences is evident

from the figure. A departure from this simple scenario, which

predicts as many sources with

.

Given the uncertainties due to the small size of our sample, this

scenario may well be what we see in Fig. 5. Nevertheless,

a small bias toward positive velocity differences is evident

from the figure. A departure from this simple scenario, which

predicts as many sources with

![]() km s-1

as with

km s-1

as with ![]() km s-1,

is further supported by the observed imbalance of

14 vs. 8 sources in these two velocity brackets.

km s-1,

is further supported by the observed imbalance of

14 vs. 8 sources in these two velocity brackets.

Both of these trends may suggest an alternative scenario where

the UCHII regions are deeply embedded in their molecular

clouds. This geometry tends to reduce ![]() since any streaming motions are

less asymmetric. If the HCO+ line

is (partially) optically thick, a small positive bias of

since any streaming motions are

less asymmetric. If the HCO+ line

is (partially) optically thick, a small positive bias of ![]() would result, as observed, if the molecular clouds

are mainly contracting. However, as noted above,

to determine if the HCO+ cloud

is contracting or expanding around the embedded HII region,

requires further analysis of the HCO+ profiles.

would result, as observed, if the molecular clouds

are mainly contracting. However, as noted above,

to determine if the HCO+ cloud

is contracting or expanding around the embedded HII region,

requires further analysis of the HCO+ profiles.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=-90,width=8.5cm,clip]{12241Fig5.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa12241-09/Timg54.png)

|

Figure 5:

Histogram of the observed velocity differences between the ionized and

molecular gas, as obtained from our H |

| Open with DEXTER | |

4.2 Absorption dips in the HCO+ emission profiles

Of the 24 sources where HCO+ was detected, 14 have absorption dips within the emission profile, one of which, NGC 7538 IRS2, appears to have multiple absorption dips within the emission profile. Nine sources have no obvious absorption dip. Among those with observed HCO+ single absorption dips, the ``blue peak'' (i.e. lower velocity) of the double peaked HCO+ profile is brighter than the ``red peak'' toward 8 sources, and the red peak is brighter than the blue peak toward 5 sources (see Table 4). We refer to these profile types as B and R, respectively, in Table 4 and the rest of this paper.

Let us digress for a moment to summarize line profiles in an idealized collapsing molecular cloud. Myers et al. (1996) showed analytically that in the case of an optically thick, centrally condensed, collapsing cloud where the front and back halves have constant excitation temperature and dispersion velocities, the line profile will have two peaks separated by a self-absorption dip. For collapse, the blue peak will be brighter than the red peak (in our nomenclature a B-type profile). Since this analysis is symmetric, an absorption dip that falls in the blue half of the profile (an R-type profile in our nomenclature), would imply expansion. De Vries & Myers (2005) generalized the analytic model results using a Monte Carlo radiative transfer code that incorporated both a constant excitation temperature ``two-layer'' model and one in which excitation temperature increases inward as a function of optical depth. De Vries & Myers (2005) numerically calculated line profiles for collapsing clouds that fit a wide range of observed HCO+ profiles toward low-mass starless cores.

What is the origin of the absorption dips in the HCO+ lines? There are four possibilities: 1) absorption by HCO+ of the radio free-free continuum from the embedded HII region; 2) absorption by HCO+ of warm thermal dust continuum surrounding the HII region (heated by emission from the HII region); 3) self-absorption of HCO+ due to a negative temperature gradient with distance from the HII region; and, 4) two velocity components along the line of sight. Two velocity components along the line of sight can be ruled out by the single peaked H13CO+(3-2) profiles whose peak emission coincides with the velocity of the absorption dip in the H12CO+ profiles.

Let us now address whether the HCO+

absorption dips might be due to absorption of the HII region

free-free continuum. In principle, one could test this by

observing if the absorption dip is seen only toward the UC

HII region but disappears away from the HII region.

In this case, one could conclude that the absorption dip in

the HCO+ line is due to absorption of

the HII continuum emission. However, for

a 12'' HPBW at 267 GHz an

HII region of temperature 104 K

would have a brightness temperature of only ![]() (K)

(K) ![]() 3

3 ![]() 10-9 EM (pc cm-6),

where EM is the emission measure. The typical emission measure

of UC HII regions are 107 to a few

times 108 pc cm-6

(Churchwell 1991).

Thus, the main beam brightness temperatures contributed by free-free

emission are a few tenths of a degree to perhaps

a degree, depending on the flux density of the source.

This is substantially less than that needed to produce the

observed absorption dips in the HCO+(3-2) lines.

This conclusion is strengthened by the fact that the

HII continuum distribution traced by the H

10-9 EM (pc cm-6),

where EM is the emission measure. The typical emission measure

of UC HII regions are 107 to a few

times 108 pc cm-6

(Churchwell 1991).

Thus, the main beam brightness temperatures contributed by free-free

emission are a few tenths of a degree to perhaps

a degree, depending on the flux density of the source.

This is substantially less than that needed to produce the

observed absorption dips in the HCO+(3-2) lines.

This conclusion is strengthened by the fact that the

HII continuum distribution traced by the H![]() line

is a point source or only slightly extended in essentially all of our

sample, but absorption dips are detected a full HPBW

or more from the HII peak in all the sources in

our sample.

line

is a point source or only slightly extended in essentially all of our

sample, but absorption dips are detected a full HPBW

or more from the HII peak in all the sources in

our sample.

What about emission from warm dust surrounding the

HII region? Let us take a specific example, say

G10.62-0.38. The HCO+ profile shows

that at the minimum of the absorption dip,

![]() is

about 6.5 K and the maximum

is

about 6.5 K and the maximum

![]() value

outside the absorption dip is

value

outside the absorption dip is ![]() K. If the

HCO+ gas is moderately optically thick,

one would expect its excitation temperature to be approximately equal

to the kinetic temperature of the gas, implying

K. If the

HCO+ gas is moderately optically thick,

one would expect its excitation temperature to be approximately equal

to the kinetic temperature of the gas, implying

![]()

![]() 22 K. We will also assume that the maximum optical depth in

the HCO+ line

22 K. We will also assume that the maximum optical depth in

the HCO+ line

![]() (all sources in Table 7 have HCO+(3-2) optical

depths ranging from 260 to 6 with an average value

of 77). We will assume that the warm dust shell around the

HII region is large enough that it fills the telescope main

beam (i.e.

(all sources in Table 7 have HCO+(3-2) optical

depths ranging from 260 to 6 with an average value

of 77). We will assume that the warm dust shell around the

HII region is large enough that it fills the telescope main

beam (i.e.

![]() ). From the radiative transfer

equation, we solve for the continuum brightness temperature required to

produce the observed antenna temperature

). From the radiative transfer

equation, we solve for the continuum brightness temperature required to

produce the observed antenna temperature

![]() at the absorption dip and find

at the absorption dip and find

|

(1) |

Exploring the range of reasonable values of

where

Let us assume that the dust is moderately optically thick, say

![]() and

the beam filling factor of warm dust is unity. Then solving

Eq. (2)

for

and

the beam filling factor of warm dust is unity. Then solving

Eq. (2)

for ![]() ,

we find that

,

we find that ![]() K

for the minimum

K

for the minimum ![]() K.

The main result of this exercise is that for a reasonable range

of

K.

The main result of this exercise is that for a reasonable range

of

![]() (HCO+)

and

(HCO+)

and

![]() ,

the dust temperatures would have to be unreasonably high to

produce the observed absorption dips. Although it is possible for dust

to achieve temperatures >1000 K within

HII regions near a hot star, it is quite unlikely

that dust could have such high temperatures a beamwidth or more from

the central HII region. We therefore conclude that the

absorption dips are most likely produced by HCO+

self-absorption due to high HCO+ optical

depths and a negative temperature gradient with distance from the

central heat source

(i.e. the HII region). The absorption dips are

spatially strongest toward the HII regions because this is

where the highest

,

the dust temperatures would have to be unreasonably high to

produce the observed absorption dips. Although it is possible for dust

to achieve temperatures >1000 K within

HII regions near a hot star, it is quite unlikely

that dust could have such high temperatures a beamwidth or more from

the central HII region. We therefore conclude that the

absorption dips are most likely produced by HCO+

self-absorption due to high HCO+ optical

depths and a negative temperature gradient with distance from the

central heat source

(i.e. the HII region). The absorption dips are

spatially strongest toward the HII regions because this is

where the highest ![]() (HCO+) values

are observed.

(HCO+) values

are observed.

Two sources in our sample, SgrB2MC and G31.41+0.31, have absorption dips that go below the continuum level. This cannot be due to the source extending into our reference position, since our reference beam shows no evidence for residual emission toward either source. In the case of G31.41, our map of HCO+ shows that the cloud is small relative to the beam throw. We therefore must find another explanation for the subcontinuum absorption dips. Since molecular clouds are effectively bathed in an isotropic radiation field of 2.7 K, the absorption dips cannot go below 2.7 K. Also, scattering and absorption of line photons cannot remove more photons from the line than are produced in the line and therefore cannot account for absorption below the continuum. As we showed above, free-free emission from the HII regions can contribute a few tenths of a degree or so to the continuum and therefore could contribute an equivalent amount of absorption below the contnuuum. Also, as we showed above, thermal dust emission essentially contributes no measurable emission in the HCO+ line because of large line optical depths; however, outside the line frequencies dust could be the main contributor to the continuum emission. In the case where the dust has a negligible temperature gradient (such that it is not apparent in beam-switching mode), scattering and absorption of continuum photons (i.e. free-free and thermal dust) in the line could produce absorption dips below the continuum down to the minimum of 2.7 K if the line optical depths are large enough. Further support for scattering of both line photons and continuum photons at line center is the fact that the widths of the HCO+ lines are substantially broader than other molecular lines along the same line of sight that are presumably optically thin, including the H13CO+(3-2) line (compare the 12C and 13C isotopic line widths in Table 4). For treatments of radiative transfer in very optically thick lines see Auer (1968) and Auer & Mihalas (1972).

Table 5: Flow velocities, column densities, and mass fluxes

4.3 Infall or outflow mass fluxes

In Fig. 1,

we show the spectra of the three HCO+(3-2) isotopes

toward two UCHII regions as examples of both a strong and a

weak source where HCO+ is strongly

self-absorbed. The close

correspondence between the velocities of the absorption dips in the HCO+(3-2)

and the H13CO+(3-2) profiles

with the emission peak of the HC18O+(3-2) line

supports the conclusion that the double peaked profiles are due to

self-absorption and not to two velocity components along the line of

sight. Toward G28.20N, G81.67, and possibly G33.13, the H13CO+(3-2) profiles

appear to be weakly self-absorbed but weak enough that the profiles do

not appear to be strongly distorted. We use the H13CO+(3-2) profiles

to obtain the dispersion velocity of HCO+ and

use the H12CO+(3-2) profiles

to measure the parameters required to estimate the sign and magnitude

of the HCO+ mass flow around each

HII region using Eq. (9) in Myers et al. (1996). Results of our

analysis of self-absorbed HCO+ profiles

are reported in Table 5

where the measured H13CO+(3-2) line

full-width at half-maximum intensity,

![]() ,

is given in Col. 2. The line dispersion velocity in

Eq. (9) of Myers et al. (1996) is given in

Col. 3;

,

is given in Col. 2. The line dispersion velocity in

Eq. (9) of Myers et al. (1996) is given in

Col. 3; ![]() is

related to

is

related to

![]() by

by

![]() (i.e.

(i.e. ![]() is the half-width at 1/e intensity). The temperature of the

blue peak above the minimum of the absorption dip T(BD)

is given in Col. 4 of Table 5, the

temperature at the minimum of the absorption dip T(D)

is given in Col. 5, the temperature of the red peak T(RD)

is given in Col. 6, the velocity of the red peak

is the half-width at 1/e intensity). The temperature of the

blue peak above the minimum of the absorption dip T(BD)

is given in Col. 4 of Table 5, the

temperature at the minimum of the absorption dip T(D)

is given in Col. 5, the temperature of the red peak T(RD)

is given in Col. 6, the velocity of the red peak ![]() is given in Col. 7, the velocity of the blue peak

is given in Col. 7, the velocity of the blue peak ![]() is given in Col. 8, the derived flow velocities

is given in Col. 8, the derived flow velocities

![]() in Col. 9, the

half-power radius of the HCO+ emission

distribution in Col. 10, the H2 column

denisity determined from the H13CO+(3-2) emission

toward the HII region in Col. 11, and the mass fluxes

are

given in Col. 12.

in Col. 9, the

half-power radius of the HCO+ emission

distribution in Col. 10, the H2 column

denisity determined from the H13CO+(3-2) emission

toward the HII region in Col. 11, and the mass fluxes

are

given in Col. 12.

The propagated uncertainties for

![]() are based on an

are based on an ![]() % error

for

% error

for ![]() ,

,

![]() K

for

K

for ![]() ,

,

![]() ,

and

,

and ![]() ,

and

,

and ![]() km s-1

for

km s-1

for ![]() and

and ![]() .

The propagated uncertainties for

.

The propagated uncertainties for

![]() are based on the uncertainties for

are based on the uncertainties for

![]() ,

,

![]() %

for R, and 50% for N(H2).

The large uncertainties for N(H2)

are due to uncertainties in the conversion of NJ=3(H13CO+)

to

%

for R, and 50% for N(H2).

The large uncertainties for N(H2)

are due to uncertainties in the conversion of NJ=3(H13CO+)

to

![]() (H13CO+)

to N(H2); the

uncertainty of N(H2)

could be as much as an order of magnitude which would translate to a

similar uncertainty in

(H13CO+)

to N(H2); the

uncertainty of N(H2)

could be as much as an order of magnitude which would translate to a

similar uncertainty in

![]() .

However, the very large optical depths in the HCO+ lines

(ranging from 260 to 6 with an average

of 77) require values of N(H2) >

1023 cm-2, which

is consistent with the values given in Tables 5 and 7 based on

the observed H13CO+(3-2) lines.

Thus it seems unlikely that we have over-estimated N(H2)

and

.

However, the very large optical depths in the HCO+ lines

(ranging from 260 to 6 with an average

of 77) require values of N(H2) >

1023 cm-2, which

is consistent with the values given in Tables 5 and 7 based on

the observed H13CO+(3-2) lines.

Thus it seems unlikely that we have over-estimated N(H2)

and

![]() .

.

Negative values of flow velocities

![]() imply outflow and positive values infall. Five sources apparently have

a mass outflow and eight infall. It is clear that the flow

velocities in these regions are generally larger than those found in

the lower-mass star formation regions studied by Myers et al. (1996) and others.

This is not surprising because massive star formation regions

are more dynamical due to much larger masses (gravity), radiation

fields, and wind luminosities. Presumably those having outflow profiles

are more evolved and have had time to reverse

infall to an outflow in five of the 13 sources that we are

able to analyze. Assuming spherical contraction or expansion, we use

the derived flow velocities (Col. 9, Table 5) to estimate

the mass flux in each region assuming spherical flow and constant flow

velocity with radius

imply outflow and positive values infall. Five sources apparently have

a mass outflow and eight infall. It is clear that the flow

velocities in these regions are generally larger than those found in

the lower-mass star formation regions studied by Myers et al. (1996) and others.

This is not surprising because massive star formation regions

are more dynamical due to much larger masses (gravity), radiation

fields, and wind luminosities. Presumably those having outflow profiles

are more evolved and have had time to reverse

infall to an outflow in five of the 13 sources that we are

able to analyze. Assuming spherical contraction or expansion, we use

the derived flow velocities (Col. 9, Table 5) to estimate

the mass flux in each region assuming spherical flow and constant flow

velocity with radius

| (3) |

where

Of the 8 sources that have self-absorbed HCO+ profiles, 5 have expansion motions. Exploration of the mechanism by which infall motions are reversed is beyond the scope of this paper. Presumably, these sources are more evolved and have had time to reverse core contraction via radiation pressure or stellar winds or both. It is not known what determines the final mass of massive stars, although much speculation has been given to this question. Detection of expanding young massive cores obviously has important implications for the termination of protostellar accretion and further study of this phase is needed.

Table 6: Column densities from single peaked HCO+ profiles.

Table 7: Column densities N and masses M from H13CO+ lines.

It is of interest to compare the flow direction of the

molecular gas with that of the ionized gas as discussed in

Sect. 4.1.

Comparing ![]() with

with ![]() (HCO+ - H

(HCO+ - H![]() )

for each of the 22 sources where both lines are measured does

not show any significant trend. Both signs of

)

for each of the 22 sources where both lines are measured does

not show any significant trend. Both signs of ![]() (HCO+ - H

(HCO+ - H![]() )

are equally likely for the molecular cores where we see infall or

outflow motions. It seems that the large relative velocities

of the ionized gas (

)

are equally likely for the molecular cores where we see infall or

outflow motions. It seems that the large relative velocities

of the ionized gas (![]() km s-1),

directed in random directions away from the molecular cores dominates

the small infall or outflow motions (mostly

km s-1),

directed in random directions away from the molecular cores dominates

the small infall or outflow motions (mostly ![]() 1 km s-1)

of the neutral material, thus masking any possible correlation.

1 km s-1)

of the neutral material, thus masking any possible correlation.

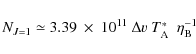

4.4 HCO+ column densities

The column density toward optically thin sources in the upper

rotational state of a linear molecule is given by

| NJu | = |

|

|

|

(4) |

where

|

(5) |

using J(

|

(6) |

for J(

Applying the appropriate relations to H13CO+(3-2) data

toward the peak of the HCO+ distribution,

we have estimated the total H2 column

densities in Table 5

(Col. 11) and Table 7

(Col. 8) for those sources with double peaked HCO+ profiles.

For an optically thick line, a lower limit for the

excitation temperature is ![]()

![]() 2.7 K +

2.7 K + ![]() /

/

![]() ;

this assumes that the line optical depth

;

this assumes that the line optical depth

![]() is substantially larger than

unity (

is substantially larger than

unity (

![]() ). As

). As

![]() increases, the line optical

depth decreases, so there is a

lower limit on

increases, the line optical

depth decreases, so there is a

lower limit on ![]() set by the maximum line optical depth (i.e. at the minimum of

the absorption dip). As

set by the maximum line optical depth (i.e. at the minimum of

the absorption dip). As

![]() increases above this lower

limit, the total HCO+ column

density will decrease due to dominance of the

increases above this lower

limit, the total HCO+ column

density will decrease due to dominance of the

![]() term in the partition function. Using the expression for

term in the partition function. Using the expression for

![]() above, the HCO+(3-2) lines all

have

above, the HCO+(3-2) lines all

have

![]() well in excess of 3

as expected if the relationship between

well in excess of 3

as expected if the relationship between

![]() and

and ![]() above holds. As noted above, the sources in Table 7 have

optical depths in the HCO+(3-2) line

ranging from 6 to 260. The column densities of HCO+

and H2 may be somewhat over-estimated, but as we

have already noted there does not seem to be a significant additional

contribution to

above holds. As noted above, the sources in Table 7 have

optical depths in the HCO+(3-2) line

ranging from 6 to 260. The column densities of HCO+

and H2 may be somewhat over-estimated, but as we

have already noted there does not seem to be a significant additional

contribution to ![]() from free-free emission although emission from extended cool dust may

make some contribution. It is unlikely that the molecular

column densities are over-estimated by as much as an order of magnitude

by an under-estimate of

from free-free emission although emission from extended cool dust may

make some contribution. It is unlikely that the molecular

column densities are over-estimated by as much as an order of magnitude

by an under-estimate of

![]() .

.

Among the sources where HCO+ was

detected, 13 are self-absorbed in the HCO+(3-2) line

and very optically thick, so we had to use the H13CO+(3-2) line

to estimate column densities as described above. Six sources, however,

are not self-absorbed and have approximately Gaussian H12CO+(3-2) profiles.

They may still suffer some optical depth effects, but we can

approximate lower limits for column densities using Eq. (5).

Results for the 6 sources with no self-absorption dip and

approximate Gaussian profiles are given in Table 6 where the

measured peak H12CO+(3-2) line

temperature is given in Col. 2, the line full-width at half

maximum, FWHM, is in Col. 3, the HCO+ column

density in J=3 is in Col. 4, the total HCO+ column

density for ![]()

![]() 2.7 + 1.92

2.7 + 1.92

![]() (K) is in Col. 5, and

the H2 column density assuming [H2]/[HCO+] =

(K) is in Col. 5, and

the H2 column density assuming [H2]/[HCO+] =

![]() (see e.g. Fuente et al. 2003) is in

Col. 6. For these sources, both N(HCO+)

and N(H2) are about an order

of magnitude lower than those with self-absorbed profiles,

as expected for more optically thin lines. However, we caution

that the values reported in

Table 6

are lower limits because the HCO+ lines

may not satisfy the optical thin assumption even though they do not

show evidence of self-absorption.

(see e.g. Fuente et al. 2003) is in

Col. 6. For these sources, both N(HCO+)

and N(H2) are about an order

of magnitude lower than those with self-absorbed profiles,

as expected for more optically thin lines. However, we caution

that the values reported in

Table 6

are lower limits because the HCO+ lines

may not satisfy the optical thin assumption even though they do not

show evidence of self-absorption.

In Table 7,

we report the parameters used to derive total HCO+

and H2 column densities and core masses

from the observed H13CO+(3-2) line.

The same source size R is assumed

as for the main isotope (Table 5). We adopt the

kinematic distances given in Table 3 based on the H![]() line

radial velocities, because the H

line

radial velocities, because the H![]() line is likely to be

more representative of the systematic velocity of the core than HCO+

which is probably affected by infall/outflow.

line is likely to be

more representative of the systematic velocity of the core than HCO+

which is probably affected by infall/outflow.

In Table 7,

Cols. 2 and 3 are the H13CO+(3-2) line

FWHM and peak line antenna temperature above the continuum;

Col. 4 is the H13CO+ column

density in the J=3 level; the lower limit

on the excitation temperature (

![]()

![]() 2.7 K + 1.92

2.7 K + 1.92

![]() )

is given in Col. 5; the upper limit on the total column

density of

H13CO+ is given in

Col. 6 and the total molecular hydrogen column density

assuming [H2]/[HCO+] =

)

is given in Col. 5; the upper limit on the total column

density of

H13CO+ is given in

Col. 6 and the total molecular hydrogen column density

assuming [H2]/[HCO+] =

![]() is given in Col. 7. In Col. 8, an upper

limit on the core mass is given using M =

is given in Col. 7. In Col. 8, an upper

limit on the core mass is given using M =

![]()

![]()

![]() N(H2)/2R

where we assume for the mean molecular weight

N(H2)/2R

where we assume for the mean molecular weight ![]() and

and ![]() =

1 amu. The spherical approximation seems reasonable from the

observed HCO+ emission distributions

(Figs. 2b

and 4).

The errors for N(H2) have

been discussed in Sect. 4.3

and dominate the estimated errors for the mass M.

We assign the lower limits of

=

1 amu. The spherical approximation seems reasonable from the

observed HCO+ emission distributions

(Figs. 2b

and 4).

The errors for N(H2) have

been discussed in Sect. 4.3

and dominate the estimated errors for the mass M.

We assign the lower limits of ![]() %, but note that the errors

could be higher due to uncertainties in the conversions from N(H13CO+)

to N(H2).

As pointed out in Sect. 4.3, it is

more likely that both N(H2)

and M are under-estimated rather than

over-estimated.

%, but note that the errors

could be higher due to uncertainties in the conversions from N(H13CO+)

to N(H2).

As pointed out in Sect. 4.3, it is

more likely that both N(H2)

and M are under-estimated rather than

over-estimated.

With all the assumptions that have gone into the

determinations of total column densities and the masses determined from

the column densities, one should view the values as order of magnitude

estimates. It is likely that the masses are, in fact,

only lower limits on the total mass of the

natal H2 cloud since the HCO+ emission

probably only traces the dense central cores of more extended clouds.

The total mass of the natal clouds are of interest, because it is

important to determine the minimum cloud mass required to form a

massive O star with its associated cluster of lower mass

stars. Typically it has been found that ![]()

![]() seem to be required to produce one intermediate mass O-star with its

accompanying cluster of lower mass stars (Churchwell 1997). The values

found here support thresholds of this magnitude when we take into

account that the HCO+ data probably

only sample the central cores of substantially larger molecular clouds.

G81.68+0.54 may be an exception to this.

seem to be required to produce one intermediate mass O-star with its

accompanying cluster of lower mass stars (Churchwell 1997). The values

found here support thresholds of this magnitude when we take into

account that the HCO+ data probably

only sample the central cores of substantially larger molecular clouds.

G81.68+0.54 may be an exception to this.

4.5 H30 line widths

line widths

The H![]() line widths range from 21.5 to over 57 km s-1

in our sample of sources. In terms of the equivalent Doppler

temperature (i.e. the kinetic temperature that hydrogen gas

would have to have to produce the observed full-width-at-half maximum

(FWHM) linewidth, this range corresponds to 5000 K to

>35 000 K, respectively. The upper extreme of

this range is well outside the values typically found in

HII regions; temperatures as low as 5000 K are found

in the inner Galaxy where metallicities are substantially greater than

at the solar circle. 35 000 K is much hotter than the

kinetic temperatures that typical Galactic plane metallicities will

permit except in shocks and very near hot stars. A further

important point is that the H

line widths range from 21.5 to over 57 km s-1

in our sample of sources. In terms of the equivalent Doppler

temperature (i.e. the kinetic temperature that hydrogen gas

would have to have to produce the observed full-width-at-half maximum

(FWHM) linewidth, this range corresponds to 5000 K to

>35 000 K, respectively. The upper extreme of

this range is well outside the values typically found in

HII regions; temperatures as low as 5000 K are found

in the inner Galaxy where metallicities are substantially greater than

at the solar circle. 35 000 K is much hotter than the

kinetic temperatures that typical Galactic plane metallicities will

permit except in shocks and very near hot stars. A further

important point is that the H![]() line is unlikely to

suffer significant pressure broadening (see Gordon & Sorochenko

2002), even in

dense UC HII regions. Sewilo et al. (2008) has

successfully separated thermal, turbulent, pressure, and large-scale

motions in the hypercompact (HC) HII region G28.20-0.04N and

showed that this ultra-dense HII region cannot have

significant pressure broadening of the H

line is unlikely to

suffer significant pressure broadening (see Gordon & Sorochenko

2002), even in

dense UC HII regions. Sewilo et al. (2008) has

successfully separated thermal, turbulent, pressure, and large-scale

motions in the hypercompact (HC) HII region G28.20-0.04N and

showed that this ultra-dense HII region cannot have

significant pressure broadening of the H![]() line and accommodate

the other broadening components that were independently measured. We

therefore will assume that H

line and accommodate

the other broadening components that were independently measured. We

therefore will assume that H![]() lines with FWHM in

excess of

lines with FWHM in

excess of ![]() km s-1

is not due to pressure broadening, but require large scale motions such

as expansion or contraction, bipolar outflows, rotation (of an

accretion disk, torus or shell), and/or shocks. Turbulence, although a

contributor, was found by Sewilo et al. (2008) to be small

relative to large scale motions in G28.20-0.04N. It is no

surprise to find bulk motions in UC and HC HII regions, which

are expected to be very dynamic especially during the period of rapid

accretion that occurs as massive star are built. It is

therefore not difficult to understand, in principle, the large

linewidths found in our sample (see Sewilo et al. 2008, for a break

down of the various line broadening components

in G28.20-0.04N).

km s-1

is not due to pressure broadening, but require large scale motions such

as expansion or contraction, bipolar outflows, rotation (of an

accretion disk, torus or shell), and/or shocks. Turbulence, although a

contributor, was found by Sewilo et al. (2008) to be small

relative to large scale motions in G28.20-0.04N. It is no

surprise to find bulk motions in UC and HC HII regions, which

are expected to be very dynamic especially during the period of rapid

accretion that occurs as massive star are built. It is

therefore not difficult to understand, in principle, the large

linewidths found in our sample (see Sewilo et al. 2008, for a break

down of the various line broadening components

in G28.20-0.04N).

Electron temperatures of the HII regions could not be measured because the millimeter free-free continuum could not be reliably separated from the dust emission.

5 Summary and conclusions

We have presented observations of 30 ultracompact and hypercompact

HII regions in the lines of HCO+(3-2)

and/or HCO+(1-0) and H![]() and/or H

and/or H![]() .

Images are presented in HCO+(3-2) and H

.

Images are presented in HCO+(3-2) and H![]() emission

regions and sizes are reported with a resolution of 12''.

In addition, H13CO+(3-2)

observations are reported toward 13 HII regions where

HCO+ profiles showed signs of

self-absorption. All data have been obtained with the IRAM

30 m telescope, mostly at 1 mm.

emission

regions and sizes are reported with a resolution of 12''.

In addition, H13CO+(3-2)

observations are reported toward 13 HII regions where

HCO+ profiles showed signs of

self-absorption. All data have been obtained with the IRAM

30 m telescope, mostly at 1 mm.

It was shown that the HII regions and HCO+

are generally in motion relative to each other at speeds ranging

from 0.5 to <9 km s-1.

Since the H![]() and HCO+ regions coincide almost

precisely, the relative velocities may represent a combination of

relative bulk motions between

the HII region and the molecular cloud plus

contraction/expansion of the HCO+ envelope.

and HCO+ regions coincide almost

precisely, the relative velocities may represent a combination of

relative bulk motions between

the HII region and the molecular cloud plus

contraction/expansion of the HCO+ envelope.

We examined four possibilities for the origin of the

absorption dips in the HCO+ profiles:

HII free-free continuum, warm dust continuum surrounding the

HII region, two velocity components along the line of sight,

and HCO+ self-absorption.

It was shown that UC HII regions at 267 GHz

are too optically thin to produce bright enough continuum emission to

produce the observed absorption dips. For dust to produce a detectable

absorption dip it would have to have temperatures

![]() K,

which we rejected because the absorption dips are seen more than one

full beam width away from the HII regions where it is highly

unlikely that dust could have such high temperatures. The hypothesis of

two velocity components along the line of sight was rejected based on H13CO+(3-2) profiles

which are not double peaked. Also, the H13CO+ line

peaks at the velocities of the absorption dips in the H12CO+ lines.

We therefore conclude that the absorption dips

are due to HCO+ self-absorption.

K,

which we rejected because the absorption dips are seen more than one

full beam width away from the HII regions where it is highly

unlikely that dust could have such high temperatures. The hypothesis of

two velocity components along the line of sight was rejected based on H13CO+(3-2) profiles

which are not double peaked. Also, the H13CO+ line

peaks at the velocities of the absorption dips in the H12CO+ lines.

We therefore conclude that the absorption dips

are due to HCO+ self-absorption.

Lower limits on HCO+ column densities

were determined for sources that have gaussian profiles

(i.e. not double peaked) from the intensities of the HCO+ lines.

Column densities for sources with self-absorbed profiles were

determined using the observed H13CO+ lines;

to estimate H2 column

densities it was assumed that [HCO+]/[H13CO+] = 40

(see e.g. Langer & Penzias 1990) and [H2]/[HCO+] =

![]() .

Masses for the dense cloud cores traced by HCO+ were estimated from the

observed diameter of the HCO+ emission

and the H2 column densities. Due to the

uncertain assumptions involved, the column densities and masses should

be considered order of magnitude estimates. Evenso, they are useful

because they support independently

determined threshold masses required to form massive stars along with

their associated lower mass stars.

.

Masses for the dense cloud cores traced by HCO+ were estimated from the

observed diameter of the HCO+ emission

and the H2 column densities. Due to the

uncertain assumptions involved, the column densities and masses should

be considered order of magnitude estimates. Evenso, they are useful

because they support independently

determined threshold masses required to form massive stars along with

their associated lower mass stars.

Using the two-layer analytic model of Myers et al. (1996) applied to the

13 sources that have double peaked HCO+ profiles,

we derived mass flow velocities and mass flux rates. It was

found that 8 sources have infall velocities and 5

have outflow velocities; this is similar to

the fractions of expanding and contracting cores found in the Orion

molecular cloud by Velusamy et al. (2008). The flow

velocities are typically a few tenths of km s-1,

although two sources (G10.62 and W51D) have flow

velocities ![]() km s-1.

Expanding young massive protostellar cores have important implications

for the termination of protostellar accretion and the final mass of a

massive protostar. An obvious mechanism to reverse infall is

the action of stellar radiation and winds; however, this needs to be

explored more thoroughly to be put on a more solid theoretical and

observational foundation.

km s-1.

Expanding young massive protostellar cores have important implications

for the termination of protostellar accretion and the final mass of a

massive protostar. An obvious mechanism to reverse infall is

the action of stellar radiation and winds; however, this needs to be

explored more thoroughly to be put on a more solid theoretical and

observational foundation.

Mass flux rates were found to be quite large, typically a few

times 10-3 ![]() yr-1.

Both the flow velocities and the mass fluxes found here are consistent

with those found by Barnes et al. (2010) in the massive

protostellar cluster By 72 in Carina. At these rates,

a 40

yr-1.

Both the flow velocities and the mass fluxes found here are consistent

with those found by Barnes et al. (2010) in the massive

protostellar cluster By 72 in Carina. At these rates,

a 40 ![]() star could be formed in <105 yr.

Such short time scales are consistent with massive star formation model

predictions and inferences from independent observations. Such short

time scales

imply that detection of protostars in the rapid accretion phase should

be rare. Presumably, the reason we have been successful in

detecting 8 such sources out of a sample of 30 is

because the sample has been carefully selected for especially young

massive star formation regions.

star could be formed in <105 yr.

Such short time scales are consistent with massive star formation model

predictions and inferences from independent observations. Such short

time scales

imply that detection of protostars in the rapid accretion phase should

be rare. Presumably, the reason we have been successful in

detecting 8 such sources out of a sample of 30 is

because the sample has been carefully selected for especially young

massive star formation regions.

The observed radio recombination lines could not be used to derive electron temperatures of the HII regions because we were unable to reliably detect the free-free continuum emission near 267 GHz.

AcknowledgementsWe thank the IRAM Director, Pierre Cox, for granting additional telescope time which permitted us to conclude this project in a timely manner. IRAM is supported by INSU/CNRS (France), MPG (Germany) and IGN (Spain). IRAM telescope staff efficiently supported the observations. We also thank an anonymous referee for a very careful reading of the mauscript and for several suggestions that have improved this paper. E.C. acknowledges partial support from NSF grant AST-0808119 and NASA contract No. 1282620.

References

- Afflerbach, A., Churchwell, E., Acord, J. M., et al. 1996, ApJS, 106, 423 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Afflerbach, A., Churchwell, E., & Werner, M. W. 1997, ApJ, 478, 190 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Auer, L. H. 1968, ApJ, 153, 923 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Auer, L. H., & Mihalas, D. 1972, ApJS, 24, 193 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, P. J., Yonekura, Y., Ryder, S. D., et al. 2010, ApJ, to be published [Google Scholar]

- Baudry, A., Perault, M., del La Noe, J., Despois, D., & Cernicharo, J. 1981, A&A, 104, 101 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Bourke, T. L., Garay, G., Lehtinen, K. K., et al. 1997, ApJ, 476, 781 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cesaroni, R., Walmsley, C. M., Koempe, C., & Churchwell, E. 1991, A&A, 252, 278 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Cesaroni, R., Olmi, L., Walmsley, C. M., Churchwell, E., & Hofner, P. 1994, ApJ, 435, 137 [Google Scholar]

- Cesaroni, R., Hofner, P., Walmsley, C. M., & Churchwell, E. 1998, A&A, 331, 709 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Choi, M., Evans, N. J., & Jaffe, D. T. 1993, ApJ, 417, 624 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Churchwell, E. 1991, NATO ASI Ser. C, 342, 221 [Google Scholar]

- Churchwell, E. 1997, ApJ, 479, L59 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]