| Issue |

A&A

Volume 512, March-April 2010

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A29 | |

| Number of page(s) | 12 | |

| Section | Interstellar and circumstellar matter | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/200913107 | |

| Published online | 25 March 2010 | |

Disk and outflow signatures in Orion-KL:

the power of high-resolution thermal infrared spectroscopy![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

H. Beuther - H. Linz - A. Bik - M. Goto - Th. Henning

Max-Planck-Institute for Astronomy, Königstuhl 17, 69117 Heidelberg, Germany

Received 12 August 2009 / Accepted 4 January 2010

Abstract

Context. The Orion-KL region contains the closest

examples of high-mass accretion disk candidates. Studying their

properties is an essential step in studying high-mass star formation.

Aims. Resolving the molecular line emission at high

spatial and spectral resolution in the immediate environment of the

exciting sources to infer the physical properties of the associated

gas.

Methods. We used the CRIRES high-resolution

spectrograph mounted on the VLT to study the ro-vibrational 12CO,

13CO, the Pfund ![]() ,

and H2 emission between 4.59 and

4.72

,

and H2 emission between 4.59 and

4.72 ![]() m

wavelengths toward the BN object, the disk candidate source n,

and a proposed dust density enhancement IRC3.

m

wavelengths toward the BN object, the disk candidate source n,

and a proposed dust density enhancement IRC3.

Results. We detected CO absorption and emission

features toward all three targets. Toward the BN object, the

data partly confirm the results obtained more than 25 years

ago; however, we also identify several new features. While the

blue-shifted absorption is likely caused by outflowing gas, toward the

BN object we detect CO in emission extending in

diameter to ![]() 3300 AU

with a velocity structure close to the

3300 AU

with a velocity structure close to the ![]() .

Although at the observational spectral resolution limit, the 13CO

line width of that feature increases with energy levels, consistent

with a disk origin. If one also attributes the extended

CO emission to a disk origin, its extent is consistent with

other massive disk candidates in the literature. For source n,

we also find the blueshifted CO absorption likely from an outflow.

However, it also exhibits a narrower range of redshifted CO absorption

and adjacent weak CO emission, consistent with infalling

motions. We do not spatially resolve the emission for source n. For

both sources we conduct a Boltzmann analysis of the 13CO

absorption features and find temperatures between 100 and

160 K, and H2 column densities

of a few times 1023 cm-2.

The observational signatures from IRC3 are very different with only

weak absorption against a much weaker continuum source. However, the

CO emission is extended and shows wedge-like position velocity

signatures consistent with jet-entrainment of molecular gas,

potentially associated with the Orion-KL outflow system. We also

present and discuss the Pfund

.

Although at the observational spectral resolution limit, the 13CO

line width of that feature increases with energy levels, consistent

with a disk origin. If one also attributes the extended

CO emission to a disk origin, its extent is consistent with

other massive disk candidates in the literature. For source n,

we also find the blueshifted CO absorption likely from an outflow.

However, it also exhibits a narrower range of redshifted CO absorption

and adjacent weak CO emission, consistent with infalling

motions. We do not spatially resolve the emission for source n. For

both sources we conduct a Boltzmann analysis of the 13CO

absorption features and find temperatures between 100 and

160 K, and H2 column densities

of a few times 1023 cm-2.

The observational signatures from IRC3 are very different with only

weak absorption against a much weaker continuum source. However, the

CO emission is extended and shows wedge-like position velocity

signatures consistent with jet-entrainment of molecular gas,

potentially associated with the Orion-KL outflow system. We also

present and discuss the Pfund ![]() and H2 emission in the region.

and H2 emission in the region.

Conclusions. This analysis toward the closest

high-mass disk candidates outlines the power of high spectral and

spatial resolution mid-infrared spectroscopy for studying the gas

properties close to young massive stars. We will extend qualitatively

similar studies to larger samples of high-mass young stellar objects to

constrain the physical properties of the dense innermost gas structures

in more detail and in a statistical sense.

Key words: stars: formation - stars: early-type - accretion, accretion disks - techniques: spectroscopic - ISM: jets and outflows - stars: individual: Orion-BN, Orion source n

1 Introduction

Understanding the physical structure of massive accretion disks is one of the main unsolved problems in high-mass star formation. Although indirect, the main line of arguments for accretion disks stems from massive molecular outflow observations that identify collimated and energetic outflows from high-mass young stellar objects (YSOs, e.g., Beuther et al. 2002b; Henning et al. 2000; Zhang et al. 2005; Arce et al. 2007). Collimated jet-like outflow structures are usually attributed to massive accretion disks and magneto-centrifugal acceleration. Recent 2D and 3D magneto-hydrodynamical simulations of massive collapsing gas cores also result in the formation of massive accretion disks (Yorke & Sonnhalter 2002; Krumholz et al. 2009,2007). However, it is still unclear whether such massive disks are similar to their low-mass counterparts, hence dominated by the central YSO and in Keplerian rotation, or whether they are maybe self-gravitating non-Keplerian entities.

While studies at (sub)mm wavelengths are a powerful tool to mainly study the cold gas and dust components on spatial scales on the order of 1000 AU (e.g., Cesaroni et al. 2007), such observations are not that well suited to investigate the inner and warmer components of massive rotating structures. In contrast to that, mid-infrared spectral lines, e.g., ro-vibrationally excited CO emission lines, can trace these warm gas components. However, the spectral and/or spatial resolution was mostly lacking because absorption features were dominating, hence prohibiting the detection of the accretion disks in emission. Several recent studies have further demonstrated the power of high-spectral and high-spatial resolution CO mid-infrared spectroscopy for disks around low-mass YSOs and Herbig Ae stars (e.g., van der Plas et al. 2009; Pontoppidan et al. 2008; Goto et al. 2006).

To achieve the highest angular and spectral resolution

possible, we

observed some of the closest massive disk candidates in Orion at a

distance of 414 pc (Menten

et al. 2007) - Orion-BN (the

Becklin-Neugebauer Object), source n and IRC3 - in the

CO v=1-0 transitions around 4.65 ![]() m with the CRyogenic

high resolution InfraRed Echelle Spectrograph (CRIRES,

Käufl et al. 2004)

at the VLT. Both objects are well detected at

mid-infrared wavelengths exhibiting various kinds of disk-signatures.

m with the CRyogenic

high resolution InfraRed Echelle Spectrograph (CRIRES,

Käufl et al. 2004)

at the VLT. Both objects are well detected at

mid-infrared wavelengths exhibiting various kinds of disk-signatures.

The Becklin-Neugebauer Object: since its detection in the

1960s,

the BN object has been one of the archetypical high-mass YSOs

(Henning

et al. 1990; Becklin & Neugebauer 1967).

Scoville et al. (1983)

observed the

source in several frequency settings between 2 and 5 ![]() m and

detected molecular emission from several CO isotopologues (fundamental

and overtone emission), and they inferred that BN exhibits an

outflow/wind, as well as a highly confined region of molecular gas at

high densities and temperatures of

m and

detected molecular emission from several CO isotopologues (fundamental

and overtone emission), and they inferred that BN exhibits an

outflow/wind, as well as a highly confined region of molecular gas at

high densities and temperatures of ![]() 3500 K. The estimated

luminosity of the BN object is

3500 K. The estimated

luminosity of the BN object is ![]()

![]() corresponding

to a B0.5 main sequence star (Scoville

et al. 1983). More

recently, Jiang et al.

(2005) observed BN in polarized near-infrared

emission and identified signatures caused by an embedded accretion

disk. The BN object has a high velocity along the line of

sight of

corresponding

to a B0.5 main sequence star (Scoville

et al. 1983). More

recently, Jiang et al.

(2005) observed BN in polarized near-infrared

emission and identified signatures caused by an embedded accretion

disk. The BN object has a high velocity along the line of

sight of

![]() 21 km s-1

compared with the cloud velocity of around

5 km s-1 (Scoville et al. 1993).

This is consistent with the

measured high proper motions of that object (e.g.,

Plambeck et al. 1995).

Whether the BN object is expelled from the

Trapezium system or during a disintegration of a bound system once

containing source I, source n and the

BN object itself is still a

matter of debate (e.g., Gómez et al. 2005; Zapata

et al. 2009; Tan 2004).

21 km s-1

compared with the cloud velocity of around

5 km s-1 (Scoville et al. 1993).

This is consistent with the

measured high proper motions of that object (e.g.,

Plambeck et al. 1995).

Whether the BN object is expelled from the

Trapezium system or during a disintegration of a bound system once

containing source I, source n and the

BN object itself is still a

matter of debate (e.g., Gómez et al. 2005; Zapata

et al. 2009; Tan 2004).

Source n: based on a bipolar radio morphology and H2O

maser association, Menten &

Reid (1995) suggested that this source may be

one of the driving sources of the powerful molecular outflows within

Orion-KL. Extended mid-infrared emission was observed perpendicular to

the outflow axis (Greenhill

et al. 2004; Shuping et al. 2004),

and

Luhman (2000) detected CO

overtone emission. Both features are

interpreted as likely being due to an accretion disk. Source n is

believed to be in an evolutionary younger stage than the

BN object,

and the luminosity is estimated to be lower as well, on the order of

2000 ![]() (Greenhill et al. 2004).

(Greenhill et al. 2004).

IRC3: the source n observations serendipitously covered the

extended infrared source IRC3 (e.g., Dougados

et al. 1993) which we

present here as well. At 3.6 ![]() m wavelengths, IRC3 is elongated in

the northeast-southwest direction (Dougados

et al. 1993) and shows

highly polarized near- to mid-infrared emission (Minchin et al. 1991).

The observations are consistent with IRC3 being a dust density

enhancement reprocessing light from another source, potentially IRC2

(Downes

et al. 1981; Dougados et al. 1993;

Minchin

et al. 1991).

m wavelengths, IRC3 is elongated in

the northeast-southwest direction (Dougados

et al. 1993) and shows

highly polarized near- to mid-infrared emission (Minchin et al. 1991).

The observations are consistent with IRC3 being a dust density

enhancement reprocessing light from another source, potentially IRC2

(Downes

et al. 1981; Dougados et al. 1993;

Minchin

et al. 1991).

Figure 1 gives an overview of the region marking the sources discussed in the paper as well as the slit orientations (see also Sect. 2). The nominal absolute positions for the three sources are listed in Table 1.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{13107f1.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/04/aa13107-09/Timg19.png)

|

Figure 1:

Overview image of the region. The grey-scale |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Table 1: Source positions (from Dougados et al. 1993).

2 Observations

We obtained high-resolution spectra between 4.6 and 4.7 ![]() m with

CRIRES (Käufl et al. 2004)

mounted on UT1 at the VLT on Paranal, Chile.

Two grating settings were selected (12/-1/n,

m with

CRIRES (Käufl et al. 2004)

mounted on UT1 at the VLT on Paranal, Chile.

Two grating settings were selected (12/-1/n,

![]() and 12/-1/i,

and 12/-1/i, ![]() )

to observe the spectral interval covering the 12CO v=1-0[P(1)-P(5)/R(0)-R(8)] lines

without gaps.

)

to observe the spectral interval covering the 12CO v=1-0[P(1)-P(5)/R(0)-R(8)] lines

without gaps.

One slit covered the BN object with a position angle

of 126 degrees

east of north, whereas the second slit included source n and IRC3 with

a position angle of 110 degrees east of north. For the strong source

BN, only 40 secs (DIT = 2 secs,

NDIT = 10) were required. For the second

object with the weaker sources we had a total on-slit integration time

of 20 min (DIT = 10 secs,

NDIT = 2). For the BN observation a slit

width of ![]() was used while for the observation of source n a slit

with of

was used while for the observation of source n a slit

with of ![]() was selected which correspond to spectral resolving

powers

was selected which correspond to spectral resolving

powers ![]() of 100 000 and 50 000, respectively.

The non-AO mode was applied since no natural guide star is available

in the close environment. The infrared seeing measured from the

spectra was 0.35

of 100 000 and 50 000, respectively.

The non-AO mode was applied since no natural guide star is available

in the close environment. The infrared seeing measured from the

spectra was 0.35

![]() during the BN observation and 0.45

during the BN observation and 0.45

![]() for the source n observation. The nod-throw of all the observations

was set to 10

for the source n observation. The nod-throw of all the observations

was set to 10

![]() .

To correct for the telluric absorption lines,

attached to every science observation a telluric standard star

(HR 1666 with spectral type A3III) was observed.

.

To correct for the telluric absorption lines,

attached to every science observation a telluric standard star

(HR 1666 with spectral type A3III) was observed.

As extended emission in the CO lines was present in the observations, we corrected the frames for distortion in order to get a wavelength solution valid for the whole chip. Firstly, the chips are slightly rotated with respect to the slit (ranging from 0.05 degree for chip 3 to 0.45 degree in the case of chip 4). We measured the position of the brightest object as function of wavelength and calculate from the displacement in position the rotation angle. Secondly, after the rotation angle has been corrected, the curvature of the slit is corrected by measuring the position (central wavelength) of a sky-line as function of the spatial coordinate. This could be described with a 2nd degree polynomial. Using the IDL routines polywarp and poly_2d, the distortion was corrected.

After the distortion correction, the raw files are processed

by the

ESO CRIRES pipeline (version 1.10.1) in combination with the

Gasgano

software. The data are dark subtracted, flat field corrected as well

as corrected for non-linearity. The wavelength calibration is done

using the telluric emission lines in combination with a HITRAN model

spectrum (Rothman et al.

2005). A cross-correlation of the spectra with

the HITRAN spectra showed that the wavelength accuracy of the spectra

is ![]() 0.5 km s-1.

0.5 km s-1.

Two absorption lines are present in the standard star: the

Pfund ![]() and the Humphreys

and the Humphreys ![]() line. Due to the strong

telluric absorption, these lines are not trivial to remove. Therefore,

we first reduced the spectrum without correcting for the intrinsic

absorption lines of the standard star. In the final reduced spectrum

these lines become eminent as emission lines free from contamination

by the atmosphere. The Pfund

line. Due to the strong

telluric absorption, these lines are not trivial to remove. Therefore,

we first reduced the spectrum without correcting for the intrinsic

absorption lines of the standard star. In the final reduced spectrum

these lines become eminent as emission lines free from contamination

by the atmosphere. The Pfund ![]() line is also seen in our

science object. However, the Humphreys

line is also seen in our

science object. However, the Humphreys ![]() line is not present

in the science spectrum of BN before division by the standard star.

Therefore, it can be used to correct for the absorption lines of the

standard star. We used a high resolution Kurucz model spectrum from

an A0V star (http://kurucz.har vard.edu/stars.html) and scaled and

shifted the model spectrum such that the Humphreys

line is not present

in the science spectrum of BN before division by the standard star.

Therefore, it can be used to correct for the absorption lines of the

standard star. We used a high resolution Kurucz model spectrum from

an A0V star (http://kurucz.har vard.edu/stars.html) and scaled and

shifted the model spectrum such that the Humphreys ![]() profile

would fit that of the observed Humphreys

profile

would fit that of the observed Humphreys ![]() profile in the

standard star. Assuming that the Pfund

profile in the

standard star. Assuming that the Pfund ![]() line scales in the

same way as the Humphreys

line scales in the

same way as the Humphreys ![]() line does, we divided with the

model spectrum to remove the line contamination.

line does, we divided with the

model spectrum to remove the line contamination.

The spectra were corrected for the earth velocity to the local

standard of rest using rvcorrect in IRAF. The velocity

corrections

applied for the two observing dates were -3.8 km s-1

for the

BN data (observed on 21st October 2007) and

+43.2 km s-1 for

the source n/IRC3 observations (taken on 21st February 2008). The

velocity relative to the local standard of rest ![]() of

Orion varies between 2.5 and 9 km s-1

(e.g.,

Comito et al. 2005),

and we adopt the approximate value of

+5 km s-1.

of

Orion varies between 2.5 and 9 km s-1

(e.g.,

Comito et al. 2005),

and we adopt the approximate value of

+5 km s-1.

3 Results

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=-90,width=17cm,clip]{13107f2.eps} %

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/04/aa13107-09/Timg26.png)

|

Figure 2:

CRIRES observations of the R and P CO line series around 4.65 |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Toward all three sources we detected the whole suite of

12CO v=1-0 lines

present in the spectral window, the

13CO v=1-0 lines

from R(6) to R(13) that were not blended by

the 12CO v=1-0 lines,

as well as the Pfund ![]() line.

Figure 2

presents the complete spectrum toward the

BN object, and Table 2 gives an overview

of the covered

lines, their wavelengths

line.

Figure 2

presents the complete spectrum toward the

BN object, and Table 2 gives an overview

of the covered

lines, their wavelengths ![]() and the lower-level energy state of

the transitions (

and the lower-level energy state of

the transitions (

![]() ). In total, this setup covers

a

broad range of energy levels extending up to 504 K.

). In total, this setup covers

a

broad range of energy levels extending up to 504 K.

Table 2: Observed lines.

3.1 The BN object

3.1.1 CO absorption and emission

Figure 3

presents a zoom compilation of 12CO data

from the R(1) to R(8) line covering lower energy levels

between 5.5

and 199 K. If one ignores the telluric line feature at

![]() 3 km s-1

two broad absorption features can be identified

at approximately -14 and +8 km s-1.

Since all 12CO

lines are saturated, their peak absorption velocities are unreliable,

and we refer to the 13CO data (Fig. 4). The peak

velocity of the blue-shifted component is

3 km s-1

two broad absorption features can be identified

at approximately -14 and +8 km s-1.

Since all 12CO

lines are saturated, their peak absorption velocities are unreliable,

and we refer to the 13CO data (Fig. 4). The peak

velocity of the blue-shifted component is ![]() km s-1extending

from

km s-1extending

from ![]() -28 to

-28 to ![]() -8 km s-1.

The second

absorption feature has its peak at

-8 km s-1.

The second

absorption feature has its peak at ![]() 8 km s-1,

close to

the

8 km s-1,

close to

the ![]() of the cloud, and extends from

of the cloud, and extends from ![]() -8 to

-8 to ![]() 18 km s-1.

Furthermore, red-shifted from the absorption we

clearly identify a CO emission peaking in 12CO

and 13CO at

18 km s-1.

Furthermore, red-shifted from the absorption we

clearly identify a CO emission peaking in 12CO

and 13CO at

![]() 20 km s-1

and extending from

20 km s-1

and extending from ![]() 15

to

15

to

![]() 30 km s-1.

The overall extent of the 12CO absorption

and emission is from

30 km s-1.

The overall extent of the 12CO absorption

and emission is from ![]() -30

to

-30

to ![]() +30 km s-1.

It should

be noted that while the

+30 km s-1.

It should

be noted that while the ![]() of the different cloud

components for the Orion-KL region vary between

approximately 3 and

9 km s-1, Scoville et al. (1983)

inferred that the corresponding

velocity of the BN object is significantly higher around

21 km s-1 (consistent with the

different BN ejection scenarios,

e.g., Gómez

et al. 2005; Tan 2004). While the absorption

features stem

from the warmer protostellar envelopes and the surrounding cloud with

usual temperatures on the order of 100 K (see also Boltzmann

analysis

below), the ro-vibrational lines in emission can be caused by

different processes. For example, fluorescence via UV photons or

resonance scattering from strong infrared fields can excite these

lines without significantly heating the gas (e.g.,

Ryde

& Schöier 2001; Blake & Boogert 2004).

Alternatively, the ro-vibrational lines

could be caused by hotter gas components (see discussion in

Sect. 4).

We note that the critical densities of these lines are

on the order of 1013 cm-3

which practically implies that extended

gas components can be hardly responsible for the emission.

of the different cloud

components for the Orion-KL region vary between

approximately 3 and

9 km s-1, Scoville et al. (1983)

inferred that the corresponding

velocity of the BN object is significantly higher around

21 km s-1 (consistent with the

different BN ejection scenarios,

e.g., Gómez

et al. 2005; Tan 2004). While the absorption

features stem

from the warmer protostellar envelopes and the surrounding cloud with

usual temperatures on the order of 100 K (see also Boltzmann

analysis

below), the ro-vibrational lines in emission can be caused by

different processes. For example, fluorescence via UV photons or

resonance scattering from strong infrared fields can excite these

lines without significantly heating the gas (e.g.,

Ryde

& Schöier 2001; Blake & Boogert 2004).

Alternatively, the ro-vibrational lines

could be caused by hotter gas components (see discussion in

Sect. 4).

We note that the critical densities of these lines are

on the order of 1013 cm-3

which practically implies that extended

gas components can be hardly responsible for the emission.

Although the blue-shifted part of the spectrum with respect to

the

![]() of the molecular cloud is slightly broader than the

red-shifted part, nevertheless we clearly identify red-shifted

absorption as well. To first order, the blue-shifted gas seen in

absorption can be identified with outflowing gas from the region,

whereas the red-shifted features belong to gas infalling in the

direction of the central source. The outflowing gas with a maximum

velocity relative to the

of the molecular cloud is slightly broader than the

red-shifted part, nevertheless we clearly identify red-shifted

absorption as well. To first order, the blue-shifted gas seen in

absorption can be identified with outflowing gas from the region,

whereas the red-shifted features belong to gas infalling in the

direction of the central source. The outflowing gas with a maximum

velocity relative to the ![]() of

of ![]() 35 km s-1

is

consistent with outflow wings often observed at mm wavelengths from

young massive star-forming regions (e.g., Beuther

et al. 2002b). It

should be noted that the even broader outflow wings observed at mm

wavelength toward Orion-KL exceeding

35 km s-1

is

consistent with outflow wings often observed at mm wavelengths from

young massive star-forming regions (e.g., Beuther

et al. 2002b). It

should be noted that the even broader outflow wings observed at mm

wavelength toward Orion-KL exceeding ![]() 50 km s-1

(e.g.,

Chernin & Wright 1996)

are likely not related to the BN object but

rather to one or more sources about

50 km s-1

(e.g.,

Chernin & Wright 1996)

are likely not related to the BN object but

rather to one or more sources about ![]() south-east of BN (source I,

source n and/or SMA1, e.g.,

Beuther

& Nissen 2008; Greenhill et al. 2004;

Jiang

et al. 2005; Bally 2008).

south-east of BN (source I,

source n and/or SMA1, e.g.,

Beuther

& Nissen 2008; Greenhill et al. 2004;

Jiang

et al. 2005; Bally 2008).

How do these general features compare with the data published

by

Scoville et al. (1983)

which were observed during several observing runs

between December 1977 and February 1981, hence about 30 years

prior to

our observations. The general CO line structure with two

strong

absorption features plus one red-shifted emission peak are largely

the same. Also the overall extent of the emission is quite similar.

Compared to our measured values of ![]() -15,

-15, ![]() +9 and

+9 and ![]() 20 km s-1

for the three components, Scoville

et al. (1983)

report for the corresponding features velocities of -18, +9

and

+20 km s-1. While two

velocities agree well, the most

blue-shifted absorption peak appears to have shifted a little bit

between the two observations. However, given that their spectral

resolution was more than a factor 2 lower than that of the new

CRIRES

data (7 versus 3 km s-1), we

refrain from further

interpretation of this. Furthermore, Scoville

et al. (1983) identify two

more absorption features, one at -3 km s-1

and one at

+30 km s-1. Regarding the

-3 km s-1 component we are

not able to infer any changes because that features lies very close to

the telluric emission which obscures any reliable signature there.

However, Fig. 3

shows that we do not detect any

additional absorption feature blue-shifted from the

26.6 km s-1emission.

Therefore, the +30 km s-1

absorption dip reported by

Scoville et al. (1983)

was either a transient feature or not significant

with respect to the signal-to-noise ratio.

20 km s-1

for the three components, Scoville

et al. (1983)

report for the corresponding features velocities of -18, +9

and

+20 km s-1. While two

velocities agree well, the most

blue-shifted absorption peak appears to have shifted a little bit

between the two observations. However, given that their spectral

resolution was more than a factor 2 lower than that of the new

CRIRES

data (7 versus 3 km s-1), we

refrain from further

interpretation of this. Furthermore, Scoville

et al. (1983) identify two

more absorption features, one at -3 km s-1

and one at

+30 km s-1. Regarding the

-3 km s-1 component we are

not able to infer any changes because that features lies very close to

the telluric emission which obscures any reliable signature there.

However, Fig. 3

shows that we do not detect any

additional absorption feature blue-shifted from the

26.6 km s-1emission.

Therefore, the +30 km s-1

absorption dip reported by

Scoville et al. (1983)

was either a transient feature or not significant

with respect to the signal-to-noise ratio.

Since the 12CO data are so strongly

saturated, for the following

analysis we use the corresponding 13CO data

covering the R(6) to

R(13) transitions (Fig. 2).

Since the absorption depth

I/I0 is

related to the optical depth ![]() via

via

![]() we can directly estimate the optical depth

of the 13CO absorption lines shown in

Fig. 4

if the

lines are spectrally resolved. Since the full width at zero intensity

(FWZI) is on the order of 20 km s-1

(see above), this criterion is

fulfilled with our spectral resolution

we can directly estimate the optical depth

of the 13CO absorption lines shown in

Fig. 4

if the

lines are spectrally resolved. Since the full width at zero intensity

(FWZI) is on the order of 20 km s-1

(see above), this criterion is

fulfilled with our spectral resolution ![]() which

corresponds to a velocity resolution of 3 km s-1.

Except

of the lowest 13CO R(6) line component at

+9 km s-1 all

other observed 13CO absorption features have

optical depths below

1. This allows us to estimate rotational temperatures via Boltzmann

plots from the equivalent line width following the approach outlined

in Scoville et al. (1983)

also adopting their finite optical depth

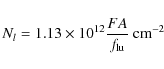

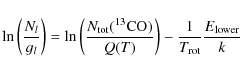

corrections. Using their Eq. (A8), the column density Nl

of

the lower-level energy state is

which

corresponds to a velocity resolution of 3 km s-1.

Except

of the lowest 13CO R(6) line component at

+9 km s-1 all

other observed 13CO absorption features have

optical depths below

1. This allows us to estimate rotational temperatures via Boltzmann

plots from the equivalent line width following the approach outlined

in Scoville et al. (1983)

also adopting their finite optical depth

corrections. Using their Eq. (A8), the column density Nl

of

the lower-level energy state is

with F, A and

with gl the statistical weight of the lower-level transition and Q(T) the partition function at the given temperature.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=-90,width=8cm,clip]{13107f3.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/04/aa13107-09/Timg38.png)

|

Figure 3:

The 12CO R(8) to R(1) lines from top

to bottom toward the BN object. Telluric and |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=-90,width=16cm,clip]{13107f4.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/04/aa13107-09/Timg39.png)

|

Figure 4: 13CO optical depths toward the BN object. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Table 3: 13CO values for Boltzmann plots.

Figure 5

presents the corresponding Boltzmann plot

where the lower-state column density Nl

divided by the statistical

weight gJ

is plotted against the lower-state energy

![]() divided by k. A linear fit to the data

gives the

rotational temperature

divided by k. A linear fit to the data

gives the

rotational temperature

![]() and the column density of

13CO divided by the partition function Q(T).

For the

-15 km s-1 13CO

component the fitted

and the column density of

13CO divided by the partition function Q(T).

For the

-15 km s-1 13CO

component the fitted ![]() is

is

![]()

![]() K.

Scoville et al. (1983)

calculated the rotation

temperature for the more blue-shifted absorption component from the

12CO v=2-0

transitions, and they find

K.

Scoville et al. (1983)

calculated the rotation

temperature for the more blue-shifted absorption component from the

12CO v=2-0

transitions, and they find ![]() 150 K

there,

which is approximately consistent with our new determination. The

other fitted parameter is

150 K

there,

which is approximately consistent with our new determination. The

other fitted parameter is ![]() cm-2.

For 2-atomic molecules like 13CO

the partition function can be approximated by

cm-2.

For 2-atomic molecules like 13CO

the partition function can be approximated by ![]() (where B is the rotation constant), and we

get a

13CO column density of

(where B is the rotation constant), and we

get a

13CO column density of ![]()

![]() cm-2.

Using

furthermore the 12CO to 13CO

isotopologic ratio of 69 (e.g.,

Sheffer et al. 2007),

we derive a total CO column density of the

-15 km s-1 component toward

Orion-BN of

cm-2.

Using

furthermore the 12CO to 13CO

isotopologic ratio of 69 (e.g.,

Sheffer et al. 2007),

we derive a total CO column density of the

-15 km s-1 component toward

Orion-BN of ![]()

![]() cm-2.

These column density estimates are in excellent

agreement with the results derived by Scoville

et al. (1983) from the

12CO v=2-0 lines.

cm-2.

These column density estimates are in excellent

agreement with the results derived by Scoville

et al. (1983) from the

12CO v=2-0 lines.

How do these values compare to other observations? The

BN object was

detected at 1.3 mm wavelength by Blake

et al. (1996) at a 0.15 Jy

level with a spatial resolution of ![]() .

Following

Plambeck et al. (1995),

about 50 mJy of that flux can be attributed to

circumstellar dust emission. Assuming optically thin dust emission,

an average dust temperature of 100 K, a dust opacity

index

.

Following

Plambeck et al. (1995),

about 50 mJy of that flux can be attributed to

circumstellar dust emission. Assuming optically thin dust emission,

an average dust temperature of 100 K, a dust opacity

index ![]() of 2 and a standard gas-to-dust ratio of 100, we can

calculate the total

H2 column density

(Beuther

et al. 2002a; Draine et al. 2007; Ossenkopf

& Henning 1994; Hildebrand 1983; Beuther

et al. 2005a; Henning et al. 1995).

The derived H2 column density and mass within

their

of 2 and a standard gas-to-dust ratio of 100, we can

calculate the total

H2 column density

(Beuther

et al. 2002a; Draine et al. 2007; Ossenkopf

& Henning 1994; Hildebrand 1983; Beuther

et al. 2005a; Henning et al. 1995).

The derived H2 column density and mass within

their ![]() synthesized beam are then

synthesized beam are then ![]() cm-2and

0.1

cm-2and

0.1 ![]() ,

respectively. For comparison, using a standard

CO-to-H2 ratio of

,

respectively. For comparison, using a standard

CO-to-H2 ratio of ![]() ,

the H2 column density

estimated here from the CO IR spectroscopy data is

,

the H2 column density

estimated here from the CO IR spectroscopy data is ![]()

![]() cm-2.

While the mm continuum data trace all velocity

components along the line of sight, the near-infrared data trace

selected velocity components. Judging from Figs. 3 and 4, where we see

more than 1 velocity component, the

total column density traced by the CO data is more than a

factor 2

higher. Furthermore, the CO absorption only traces the gas in the

foreground of the near-infrared source reducing the traced gas by

another factor 2. While both approaches are affected by

systematics

- e.g., the mm derived column densities can be wrong by a

factor 5

depending on the assumptions on the dust properties and temperatures

- other reasons are more important for some of the differences. In

particular, the mm continuum emission is sensitive to the cold and

warm dust emission whereas the near-infrared absorption of the

13CO transitions useable for our

analysis traces mainly the

warmer gas. Therefore, these data indicate that a large fraction of

the gas is at relatively low temperatures.

cm-2.

While the mm continuum data trace all velocity

components along the line of sight, the near-infrared data trace

selected velocity components. Judging from Figs. 3 and 4, where we see

more than 1 velocity component, the

total column density traced by the CO data is more than a

factor 2

higher. Furthermore, the CO absorption only traces the gas in the

foreground of the near-infrared source reducing the traced gas by

another factor 2. While both approaches are affected by

systematics

- e.g., the mm derived column densities can be wrong by a

factor 5

depending on the assumptions on the dust properties and temperatures

- other reasons are more important for some of the differences. In

particular, the mm continuum emission is sensitive to the cold and

warm dust emission whereas the near-infrared absorption of the

13CO transitions useable for our

analysis traces mainly the

warmer gas. Therefore, these data indicate that a large fraction of

the gas is at relatively low temperatures.

3.1.2 Potential signatures from the BN disk?

While most of the observed emission is spatially unresolved, we find

weak extended 12CO emission toward the

BN object. Figure 6

presents a position-velocity diagram along the slit

direction (PA of 126

![]() east of north, see Sect. 2)

which corresponds to the proposed disk orientation (Jiang et al. 2005).

We find CO emission around the rest velocity of the BN object

of

east of north, see Sect. 2)

which corresponds to the proposed disk orientation (Jiang et al. 2005).

We find CO emission around the rest velocity of the BN object

of ![]() 21 km s-1

extending approximately

21 km s-1

extending approximately ![]()

![]() in both

directions. Since we do not identify any strong velocity dispersion,

this extended emission is unlikely to be due to an outflow, but it may

potentially come from the proposed disk (Jiang

et al. 2005). The

measured extent of

in both

directions. Since we do not identify any strong velocity dispersion,

this extended emission is unlikely to be due to an outflow, but it may

potentially come from the proposed disk (Jiang

et al. 2005). The

measured extent of ![]()

![]() would then correspond at the given

distance of Orion of 414 pc to an approximate disk diameter of

would then correspond at the given

distance of Orion of 414 pc to an approximate disk diameter of

![]() 3300 AU

or a disk radius of 1650 AU. While such disk size would be

comparably large with respect to typical low-mass disks (e.g., several

reviews in Reipurth

et al. 2007), it is consistent with measured

sizes of rotating structures in other high-mass star-forming regions

(e.g., Beuther

& Walsh 2008; Beltrán et al. 2006;

Cesaroni

et al. 2005; Schreyer et al. 2002).

3300 AU

or a disk radius of 1650 AU. While such disk size would be

comparably large with respect to typical low-mass disks (e.g., several

reviews in Reipurth

et al. 2007), it is consistent with measured

sizes of rotating structures in other high-mass star-forming regions

(e.g., Beuther

& Walsh 2008; Beltrán et al. 2006;

Cesaroni

et al. 2005; Schreyer et al. 2002).

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=-90,width=9cm]{13107f5.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/04/aa13107-09/Timg58.png)

|

Figure 5: Boltzmann plot for the 13CO v=1-0 lines toward the BN object. The x-axis shows the lower-level energies of the transitions and the y-axis presents the natural logarithm of the corresponding column densities divided by their statistical weights. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=6cm,clip]{13107f6.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/04/aa13107-09/Timg59.png)

|

Figure 6:

Position velocity diagram of the 12CO (R0) line

toward the BN object along the slit direction (PA of 126

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

While we do not identify extended emission is the rarer 13CO

isotopologue, the CO and 13CO emission feature

around

20 km s-1 exhibits an

additional interesting feature in the

13CO data (Fig. 4): while the

emission feature is at

the edge of the bandpass for the 13CO R(6)

line, it remains

undetected for the R(7) line and only comes up for the lines greater

R(9). This emission feature is also visible in all 12CO lines

(R(1) to R(8)) shown in Fig. 3, but it does

not

exhibit any significant shape change there. Likely, the 12CO emission

is optically thick and traces only an outer envelope that

does not show big variations with excitation temperature. In contrast

to that, the measured Gaussian line width of that component for the

more optically thin 13CO R(9), R(10), R(11),

R(12) and R(13)

lines are 4.3, 5.3, 6.5, 6.4 and 6.6 km s-1,

respectively.

Although errors on the line width are difficult to quantify because

the emission is at the flank of the strong absorption feature, and

furthermore our spectral resolution is only 3 km s-1,

the data

are indicative of a line width increase with excitation temperature

of the line that appears to saturate for the highest detectable

transitions R(11) to R(13). While for a centrifugally supported disk

with a central mass of ![]() 10

10 ![]() the circular velocity at

3300 AU is relatively low on the order of

the circular velocity at

3300 AU is relatively low on the order of ![]() 1.6 km s-1,

the

measured line width increase is consistent with a rotating disk

structure because the inner region with higher rotation velocities

should have higher temperatures caused by the exciting central star.

One has to keep in mind that for purely thermal excitation, rotation

would not cause such an effect because the upper levels - all in the

3000 K regime - do not exhibit big relative excitation

differences.

Hence, they do not trace significantly different regions of a disk

then. In contrast to that, for lines that are excited by UV

fluorescence such an effect is possible because the excitation

mechanism via an electronic excited state tends to preserve the level

population of the v=0 rotational states (e.g.,

Brittain et al. 2009).

Therefore, in this case the R(9) to R(13)

lines are sensitive to gas temperatures in a relatively broader range

between 150 and 500 K (Table 2). An exact

reproduction of

the line width increase would require a detailed disk model, including

its density and temperature structure. Since we cannot constrain

these parameters well from our data, this is beyond the scope of this

paper. Although the line width increase is below our nominal spectral

resolution element, qualitatively the observations are consistent with

a rotating disk structure.

1.6 km s-1,

the

measured line width increase is consistent with a rotating disk

structure because the inner region with higher rotation velocities

should have higher temperatures caused by the exciting central star.

One has to keep in mind that for purely thermal excitation, rotation

would not cause such an effect because the upper levels - all in the

3000 K regime - do not exhibit big relative excitation

differences.

Hence, they do not trace significantly different regions of a disk

then. In contrast to that, for lines that are excited by UV

fluorescence such an effect is possible because the excitation

mechanism via an electronic excited state tends to preserve the level

population of the v=0 rotational states (e.g.,

Brittain et al. 2009).

Therefore, in this case the R(9) to R(13)

lines are sensitive to gas temperatures in a relatively broader range

between 150 and 500 K (Table 2). An exact

reproduction of

the line width increase would require a detailed disk model, including

its density and temperature structure. Since we cannot constrain

these parameters well from our data, this is beyond the scope of this

paper. Although the line width increase is below our nominal spectral

resolution element, qualitatively the observations are consistent with

a rotating disk structure.

3.1.3 The

Pfund  line toward the BN object and H2 emission nearby

BN

line toward the BN object and H2 emission nearby

BN

Figure 7

presents a zoom into the Pfund ![]() line.

The line shape consists of two components, one central Gaussian

component and broad line wings. It is possible to fit the whole

profile relatively well with a two-component Gaussian fit where the

central component has a FWHM

line.

The line shape consists of two components, one central Gaussian

component and broad line wings. It is possible to fit the whole

profile relatively well with a two-component Gaussian fit where the

central component has a FWHM ![]() km s-1

and the

broad component has a FWHM of

km s-1

and the

broad component has a FWHM of ![]() km s-1.

The

full width down to zero intensity is approximately

340 km s-1(between -170 and

170 km s-1). Close to the peak

of the profile

at around 25 km s-1, the

spectrum exhibits a small dip which is

likely an artifact from the telluric corrections (see Sect. 2). Considering this,

the peak of the central Gaussian fit at

km s-1.

The

full width down to zero intensity is approximately

340 km s-1(between -170 and

170 km s-1). Close to the peak

of the profile

at around 25 km s-1, the

spectrum exhibits a small dip which is

likely an artifact from the telluric corrections (see Sect. 2). Considering this,

the peak of the central Gaussian fit at

![]() 16.5 km s-1

is still consistent with the velocity derived

for the BN object by Scoville

et al. (1983) of

16.5 km s-1

is still consistent with the velocity derived

for the BN object by Scoville

et al. (1983) of ![]() 21 km s-1.

21 km s-1.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=-90,width=9cm,clip]{13107f7.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/04/aa13107-09/Timg62.png)

|

Figure 7:

Hydrogen recombination Pfund |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Figure 7

also presents as thick dots the best fit

obtained by Scoville

et al. (1983) for the Br![]() line (their

Fig. 7 re-scaled to our normalized spectrum). Their model

consists of a

supersonic, optically thin decelerating outflow with a velocity law of

line (their

Fig. 7 re-scaled to our normalized spectrum). Their model

consists of a

supersonic, optically thin decelerating outflow with a velocity law of

![]() .

It is remarkable how well the shape of their

Br

.

It is remarkable how well the shape of their

Br![]() line obtained

line obtained ![]() 30 years

ago corresponds to the shape

of the newly observed Pfund

30 years

ago corresponds to the shape

of the newly observed Pfund ![]() line. Hence, these

Pfund

line. Hence, these

Pfund ![]() data

are also consistent with their outflow model.

data

are also consistent with their outflow model.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{13107f8.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/04/aa13107-09/Timg63.png)

|

Figure 8:

Position velocity digram of the H2 emission

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

Furthermore, approximately ![]() south-east of the BN object we detect

H2 emission from the H2 0-0 S9

transition with

south-east of the BN object we detect

H2 emission from the H2 0-0 S9

transition with

![]() K.

This H2 emission feature is spatially

associated with the corresponding H2 knot in

near-infrared H2images (e.g., Nissen et al. 2007) as

well as with the mid-infrared

source IRc15 reported by Shuping

et al. (2004). Figure 8 shows

a position velocity diagram of this feature. While we do not resolve

any spatial structure of the H2 knot, it shows a

very broad

velocity extent going to blue-shifted velocities of

K.

This H2 emission feature is spatially

associated with the corresponding H2 knot in

near-infrared H2images (e.g., Nissen et al. 2007) as

well as with the mid-infrared

source IRc15 reported by Shuping

et al. (2004). Figure 8 shows

a position velocity diagram of this feature. While we do not resolve

any spatial structure of the H2 knot, it shows a

very broad

velocity extent going to blue-shifted velocities of ![]() -80 km s-1,

in excess of the CO absorption features measured

toward the BN object. Since we are mainly interested in the

BN object,

source n and IRC3, we refrain from further analysis of this

offset

H2 emission.

-80 km s-1,

in excess of the CO absorption features measured

toward the BN object. Since we are mainly interested in the

BN object,

source n and IRC3, we refrain from further analysis of this

offset

H2 emission.

3.2 Source n

3.2.1 CO absorption and emission

Due to the different observing dates, for source n (and IRC3

in the

following section) the telluric lines are almost entirely shifted out

of the CO spectrum. Figures 9

and 10

present the corresponding 12CO R-series lines

and the detected 13CO lines with their

associated optical depths.

In comparison to the previous BN data, for source n we only

identify

one broad absorption feature in the 12CO data

which is dominated

by blue-shifted outflowing gas. It is interesting to note that the

most blue-shifted absorption does not have a Gaussian shape but rather

a more extended wing-like structure. In the framework of accelerated

winds with distance from the driving star or disk, such a spectral

behavior would be expected. These accelerated winds increase in

velocity with distance from the star. Simultaneously, with increasing

distance from the driving source the density of the surrounding gas

and dust envelope also decreases, lowering the corresponding

absorption depth at those velocities. Hence, in this picture,

higher-velocity gas should show shallower absorption features in the

spectra (e.g., Lamers &

Cassinelli 1999). Furthermore, we also identify a

red-shifted emission component at ![]() +15 km s-1.

However,

compared to the BN object, where the emission feature can be

identified in all transitions, for source n it is more prominent in

the higher excited lines. The total width of the CO absorption and

emission is

+15 km s-1.

However,

compared to the BN object, where the emission feature can be

identified in all transitions, for source n it is more prominent in

the higher excited lines. The total width of the CO absorption and

emission is ![]() 90 km s-1

ranging from approximately

90 km s-1

ranging from approximately

![]() -65 to

-65 to ![]() +25 km s-1

(broader than for BN). The

blue-shifted end is less well determined because of telluric line

contamination. Nevertheless the blue-shifted outflow part of the

spectrum extends

+25 km s-1

(broader than for BN). The

blue-shifted end is less well determined because of telluric line

contamination. Nevertheless the blue-shifted outflow part of the

spectrum extends ![]() 70 km s-1

from the assumed

70 km s-1

from the assumed

![]() of +5 km s-1. This value

exceeds that measured

toward BN by about 20 km s-1.

Although at the edge of the

telluric line contamination, we tentatively identify an additional

discrete absorption feature at

of +5 km s-1. This value

exceeds that measured

toward BN by about 20 km s-1.

Although at the edge of the

telluric line contamination, we tentatively identify an additional

discrete absorption feature at ![]() -35 km s-1.

-35 km s-1.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=-90,width=8cm,clip]{13107f9.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/04/aa13107-09/Timg65.png)

|

Figure 9:

The 12CO R(8) to R(1) lines from top

to bottom toward source n. Telluric and |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Since the 12CO line is again always saturated

(Fig. 9),

for the additional analysis we use the

corresponding 13CO data (Fig. 10). Because

of

line-blending and telluric emission, we only measure five 13CO

lines for source n. The broad, saturated 12CO

absorption feature

is clearly resolved into two components with approximate velocities at

![]() -7 km s-1

and

-7 km s-1

and ![]() +5 km s-1.

While the

+5 km s-1.

While the

![]() +5 km s-1

shows the deeper absorption features for the

lower energy R-lines, it is interesting to note that the single

absorption peak observed for the 13CO

R(13) line is associated

with the

+5 km s-1

shows the deeper absorption features for the

lower energy R-lines, it is interesting to note that the single

absorption peak observed for the 13CO

R(13) line is associated

with the ![]() -7 km s-1

component, indicating hotter gas at

more blue-shifted velocities. Following the approach outlined for BN

in Sect. 3.1.1,

the derived optical depth of 13CO is

-7 km s-1

component, indicating hotter gas at

more blue-shifted velocities. Following the approach outlined for BN

in Sect. 3.1.1,

the derived optical depth of 13CO is

![]() 0.6 at its

highest.

0.6 at its

highest.

Since the telluric lines are far away in velocity space (see

Fig. 9),

for source n we can conduct the

Boltzmann analysis for both absorption components separately. The

measured equivalent widths A for both

components are listed in Table 3![]() . Again

calculating the 13CO v=1

column densities (Table 3)

and producing Boltzmann plots (Fig. 11), we find

that

for both velocity components fits to all 5 data points are less good

than in the case of the BN object. This is likely due to the

fact that

fitting 2 Gaussians to the broad R(13) line, which does not show two

well separated absorption features anymore, may overestimate the

contribution of the

. Again

calculating the 13CO v=1

column densities (Table 3)

and producing Boltzmann plots (Fig. 11), we find

that

for both velocity components fits to all 5 data points are less good

than in the case of the BN object. This is likely due to the

fact that

fitting 2 Gaussians to the broad R(13) line, which does not show two

well separated absorption features anymore, may overestimate the

contribution of the ![]() -7 km s-1

component and hence

underestimate the contribution from the

-7 km s-1

component and hence

underestimate the contribution from the ![]() +5 km s-1component.

Therefore, we also fit only the 4 lower-energy transitions

between R(7) and R(12) resulting in better fits

(Fig. 11).

As expected from the different behavior of

the two absorption components with increasing energy levels, the

derived rotation temperatures using the 4 lower energy lines

of the

+5 km s-1component.

Therefore, we also fit only the 4 lower-energy transitions

between R(7) and R(12) resulting in better fits

(Fig. 11).

As expected from the different behavior of

the two absorption components with increasing energy levels, the

derived rotation temperatures using the 4 lower energy lines

of the

![]() -7 km s-1

and

-7 km s-1

and ![]() +5 km s-1

are

+5 km s-1

are ![]()

![]() K

and

K

and ![]()

![]() K,

respectively. As a comparison,

rotational temperatures measured at submm wavelength from CH3OH

emission lines toward source n are around 200 K (Beuther et al. 2005b).

Considering that these measurements are conducted with different

molecules and very different observational techniques, the overall

range of similar temperatures derived at mid-infrared and submm

wavelengths is reassuring for the complementarity of such

multi-wavelengths observations.

K,

respectively. As a comparison,

rotational temperatures measured at submm wavelength from CH3OH

emission lines toward source n are around 200 K (Beuther et al. 2005b).

Considering that these measurements are conducted with different

molecules and very different observational techniques, the overall

range of similar temperatures derived at mid-infrared and submm

wavelengths is reassuring for the complementarity of such

multi-wavelengths observations.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=-90,width=16.5cm,clip]{13107f10.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/04/aa13107-09/Timg68.png)

|

Figure 10:

13CO optical depths toward

source n. The absorption feature at |

| Open with DEXTER | |

3.2.2 The

Pfund  line

line

The Pfund ![]() line is also detected toward source n

(Fig. 12),

and we can fit a Gaussian to the

recombination line with FWHM of

line is also detected toward source n

(Fig. 12),

and we can fit a Gaussian to the

recombination line with FWHM of ![]() km s-1,

a width down to 0 intensity of

km s-1,

a width down to 0 intensity of ![]() 70 km s-1

(from

70 km s-1

(from ![]() -35 to

-35 to ![]() +35 km s-1)

and a central velocity of

+35 km s-1)

and a central velocity of

![]() 0 km s-1.

The line is covered by 2 CRIRES chips, and

while the general Pfund

0 km s-1.

The line is covered by 2 CRIRES chips, and

while the general Pfund ![]() line shape is the

same for both

chips, the central dip at

line shape is the

same for both

chips, the central dip at ![]() 0 km s-1

cannot independently

be reproduced. Therefore, the dip is likely only an artifact due to

insufficient signal to noise.

0 km s-1

cannot independently

be reproduced. Therefore, the dip is likely only an artifact due to

insufficient signal to noise.

The thermal line width of a 104 K

hydrogen gas is

![]() 21.4 km s-1.

Convolving that with the 6 km s-1spectral

resolution, the observable thermal line width should be

21.4 km s-1.

Convolving that with the 6 km s-1spectral

resolution, the observable thermal line width should be

![]() 22.2 km s-1.

Therefore, the measured line width does not

exceed much the thermal line width of an H II region.

Hence, the

Pfund

22.2 km s-1.

Therefore, the measured line width does not

exceed much the thermal line width of an H II region.

Hence, the

Pfund ![]() emission from source n does not exhibit strong

signatures from a wind but is rather consistent with a thermal H II region.

We also cannot exclude that the Pfund

emission from source n does not exhibit strong

signatures from a wind but is rather consistent with a thermal H II region.

We also cannot exclude that the Pfund ![]() emission

toward source n is contaminated by more broadly distributed Orion

nebula emission.

emission

toward source n is contaminated by more broadly distributed Orion

nebula emission.

![\begin{figure}

\par\mbox{\includegraphics[angle=-90,width=8cm,clip]{1310711a.eps}\hskip5mm

\includegraphics[angle=-90,width=8cm,clip]{1310711b.eps} }\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/04/aa13107-09/Timg81.png)

|

Figure 11:

Boltzmann plots for the 13CO v=1-0

lines toward source n for the |

| Open with DEXTER | |

3.3 IRC3

As outlined in the Introduction, in contrast to the BN object and source n, the source IRC3 is unlikely to be a YSO, and it is not prominent in any typical hot core tracer (e.g., Blake et al. 1996; Beuther et al. 2005b). The source rather resembles a more extended dust density enhancement that reprocesses light from other sources, potentially IRC2. Figure 13 presents a part of the 2D slit spectrum clearly showing the extended nature of the CO emission toward IRC3 in contrast to the point-like continuum structure from source n. The continuum emission from IRC3 is very weak compared to that from source n.

Figure 14

shows the CO lines extracted as an average

spectrum of length ![]() toward IRC3. While we again see a broad

absorption feature against the weaker background extending from

toward IRC3. While we again see a broad

absorption feature against the weaker background extending from ![]() -5 km s-1

out to the telluric contamination at about

-40 km s-1, IRC3 shows a broad

and strong emission feature

peaking at

-5 km s-1

out to the telluric contamination at about

-40 km s-1, IRC3 shows a broad

and strong emission feature

peaking at ![]() 2 km s-1.

Since this emission is extended

over several arcseconds, Fig. 15 presents the

position

velocity diagrams of selected 12CO and all 13CO

lines. In

contrast to the BN object where the extended CO emission is

just

around the rest velocity of the star (Fig. 6), here we see a

clear trend of increasing velocity with increasing distance from the

continuum peak (the so-called Hubble law of outflows). Furthermore, in

particular the 12CO position velocity diagrams

show a twofold

structure with one velocity increase to values

>10 km s-1 at

offsets of

2 km s-1.

Since this emission is extended

over several arcseconds, Fig. 15 presents the

position

velocity diagrams of selected 12CO and all 13CO

lines. In

contrast to the BN object where the extended CO emission is

just

around the rest velocity of the star (Fig. 6), here we see a

clear trend of increasing velocity with increasing distance from the

continuum peak (the so-called Hubble law of outflows). Furthermore, in

particular the 12CO position velocity diagrams

show a twofold

structure with one velocity increase to values

>10 km s-1 at

offsets of ![]()

![]() and another increase to similar velocities at

and another increase to similar velocities at

![]()

![]() offset

from the main continuum peak. To guide the eye,

these wedge-like structures are sketched in the top-right panel of

Fig. 15).

Such multiple wedge position velocity

structures are what jet-bow-shock entrainment models for molecular

outflows predict (e.g., Arce

et al. 2007). Furthermore, similar to

source n, the CO absorption shows also for IRC3 the extended

wing-like

features toward the most blue-shifted absorption. Similar to the

pv-diagrams, where we see acceleration of the gas with distance from

the source, these wing-like absorption can also be interpreted in the

framework of accelerated winds (see also Sect. 3.2.1 or

Lamers & Cassinelli 1999).

offset

from the main continuum peak. To guide the eye,

these wedge-like structures are sketched in the top-right panel of

Fig. 15).

Such multiple wedge position velocity

structures are what jet-bow-shock entrainment models for molecular

outflows predict (e.g., Arce

et al. 2007). Furthermore, similar to

source n, the CO absorption shows also for IRC3 the extended

wing-like

features toward the most blue-shifted absorption. Similar to the

pv-diagrams, where we see acceleration of the gas with distance from

the source, these wing-like absorption can also be interpreted in the

framework of accelerated winds (see also Sect. 3.2.1 or

Lamers & Cassinelli 1999).

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=-90,width=9cm,clip]{13107f12.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/04/aa13107-09/Timg84.png)

|

Figure 12:

Hydrogen recombination Pfund |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| Figure 13:

Original data from the slit covering source n and IRC3. Source n is the

bright continuum source at offset |

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

4 Discussion and conclusion

High spectral resolution mid-infrared observations allow us to infer

several important characteristics of some of the major sources within

the Orion-KL region. The fundamental CO lines are largely dominated by

absorption from the individual YSO envelopes and their surrounding gas

cloud. These absorption features are blue- and red-shifted with

respect to the ![]() of the molecular cloud indicating that

outflowing and inflowing gas are simultaneously present toward our

target sources. However, we also identify interesting emission

features. Together they confirm the youth of the sources where infall

and likely accretion are still ongoing.

of the molecular cloud indicating that

outflowing and inflowing gas are simultaneously present toward our

target sources. However, we also identify interesting emission

features. Together they confirm the youth of the sources where infall

and likely accretion are still ongoing.

![\begin{figure}

\vspace*{5.3cm}

\includegraphics[angle=-90,width=8.8cm,clip]{13107f14.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/04/aa13107-09/Timg87.png)

|

Figure 14:

The 12CO R(8) to R(1) lines (except of the R(4)

line from top to bottom toward IRC3. Since the

emission is extended, this spectrum is an average over |

| Open with DEXTER | |

BN object:

for the BN object, our data confirm, at double the spectral resolution, several of the assessments conducted already by Scoville et al. (1983). However, also discrepancies arise. For example, an absorption feature reported previously around +30 km s-1 is not found in the new data, indicating either transient components or poor signal-to-noise in the older data. From a Boltzmann analysis, the rotational temperature is around 112 K, and we derive CO column densities of several times 1018 cm-2, well in agreement with the older results based on 12CO v=2-0 by Scoville et al. (1983). Using standard CO-to-H2 conversion factors, these column densities are about an order of magnitude below H2column density estimates based on mm continuum emission. As discussed in Sect. 3.1.1, while systematics may account for some of this discrepancy, the main difference is that the mm continuum emission is sensitive to cold and warm dust, whereas the near-infrared absorption lines trace only the warm gas components.![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=18cm,clip]{13107f15.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/04/aa13107-09/Timg88.png)

|

Figure 15:

Position velocity cuts along the slit axis for IRC3 with a PA of

110 degrees east of north. The top row shows diagrams for

selected 12CO lines, and the bottom

row presents the 13CO data. For 13CO

the scaling is adapted to highlight the weaker extended emission in

contrast to the continuum at offset

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

Source n:

while bright sources like the BN object were already feasible to be observed a while ago (e.g., Scoville et al. 1983) weaker sources like source n or IRC3 were only possible to observe with reasonable high-spectral-resolution spectroscopy since the advent of recent instruments like CRIRES on the VLT. The general picture for source n is relatively similar. A single broad absorption feature extending approximately to -65 km s-1 traces mainly the molecular outflow whereas red-shifted emission likely stems from an inner infalling and accreting envelope/disk. This picture is consistent with disk/outflow proposals for this source deduced from cm and mid-infrared wavelength imaging projects (e.g., Menten & Reid 1995; Greenhill et al. 2004; Shuping et al. 2004). The clearly resolved double-peaked 13CO structure allows to conduct the Boltzmann analysis for both components. We find that the colder component has higher H2 column densities (IRC3:

the observational signatures from the dust density enhancement IRC3 are very different compared to the two previously discussed sources. The continuum from IRC3 is much weaker, nevertheless we detect CO absorption betweenLimitations and future:

one shortcoming of the data is that for our primary targets, the BN object and source n, we could not spatially resolve the inner region of the emission as done in the lower-mass case presented in Goto et al. (2006). The reasons may be different for the two sources. Source n is probably still too young and too deeply embedded so that the envelope overwhelms any emission from the embedded disk itself. The BN object has the advantage that its velocity of rest is offset from that of the cloud by more than 10 km -1, and hence absorption could be less of a problem for such kind of source. However, BN is likely significantly more evolved, and the continuum-to-line ratio is so high that we cannot reasonably filter out the continuum emission. Hence, we cannot well study the inner region of the proposed disk. Nevertheless, observing higher J-transitions as well as the CO overtone emission with todays higher sensitivity compared to the Scoville et al. (1983) observations will likely constrain the proposed disk structure in more detail.How to proceed now if one wants to do similar-type fundamental CO line studies of disks in high-mass star formation? On the one hand, it is important to not select too young sources because their envelopes will likely almost always ``destroy'' the emission signatures. There may exist exceptions where one views straight through the outflow cavity face-on toward the disk. On the other hand, for more evolved regions, the continuum emission can be very strong or maybe the remaining disk size can be reduced again making the spatial resolution a problem. Therefore, in addition to very careful target selections, adding AO to achieve the best spatial resolution will be a crucial element for such kind of studies in the coming years. Furthermore, in particular for the mostly saturated 12CO lines, it will be important to extend the spectral coverage to also observe higher excited CO lines, that will likely not saturate anymore, as well as CO overtone emission. This will allow us to better assess the hotter gas components and hence to conduct a more detailed analysis of the 12CO data themselves. On longer time-scales, the ELT with its proposed mid-infrared instrument METIS promises orders of magnitude progress in this field based on its superior sensitivity and spatial resolution. With this instrument, we will be truly capable to resolve the gas signatures of accretion disks around (high-mass) YSOs.

AcknowledgementsWe like to thank a lot the anonymous referee as well as the Editor Malcolm Walmsley for thorough reviews which helped improving the paper. H.B. acknowledges financial support by the Emmy-Noether-Program of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, grant BE2578).

References

- Arce, H. G., Shepherd, D., Gueth, F., et al. 2007, in Protostars and Planets V, ed. B. Reipurth, D. Jewitt, & K. Keil, 245 [Google Scholar]

- Bally, J. 2008, in Massive Star Formation: Observations Confront Theory, ed. H. Beuther, H. Linz, & T. Henning, ASP Conf. Ser., 387, 158 [Google Scholar]

- Becklin, E. E., & Neugebauer, G. 1967, ApJ, 147, 799 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Beltrán, M. T., Cesaroni, R., Codella, C., et al. 2006, Nature, 443, 427 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beuther, H., & Nissen, H. D. 2008, ApJ, 679, L121 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Beuther, H., & Walsh, A. J. 2008, ApJ, 673, L55 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Beuther, H., Schilke, P., Menten, K. M., et al. 2002a, ApJ, 566, 945 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Beuther, H., Schilke, P., Sridharan, T. K., et al. 2002b, A&A, 383, 892 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Beuther, H., Zhang, Q., Greenhill, L. J., et al. 2004, ApJ, 616, L31 [Google Scholar]

- Beuther, H., Schilke, P., Menten, K. M., et al. 2005a, ApJ, 633, 535 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Beuther, H., Zhang, Q., Greenhill, L. J., et al. 2005b, ApJ, 632, 355 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Blake, G. A., & Boogert, A. C. A. 2004, ApJ, 606, L73 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Blake, G. A., Mundy, L. G., Carlstrom, J. E., et al. 1996, ApJ, 472, L49 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Brittain, S. D., Najita, J. R., & Carr, J. S. 2009, ApJ, 702, 85 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cesaroni, R., Neri, R., Olmi, L., et al. 2005, A&A, 434, 1039 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Cesaroni, R., Galli, D., Lodato, G., Walmsley, C. M., & Zhang, Q. 2007, in Protostars and Planets V, ed. B. Reipurth, D. Jewitt, & K. Keil, 197 [Google Scholar]

- Chernin, L. M., & Wright, M. C. H. 1996, ApJ, 467, 676 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Comito, C., Schilke, P., Phillips, T. G., et al. 2005, ApJS, 156, 127 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Dougados, C., Lena, P., Ridgway, S. T., Christou, J. C., & Probst, R. G. 1993, ApJ, 406, 112 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Downes, D., Genzel, R., Becklin, E. E., & Wynn-Williams, C. G. 1981, ApJ, 244, 869 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Draine, B. T., Dale, D. A., Bendo, G., et al. 2007, ApJ, 663, 866 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, L., Rodríguez, L. F., Loinard, L., et al. 2005, ApJ, 635, 1166 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Goto, M., Usuda, T., Dullemond, C. P., et al. 2006, ApJ, 652, 758 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhill, L. J., Gezari, D. Y., Danchi, W. C., et al. 2004, ApJ, 605, L57 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Henning, T., Pfau, W., & Altenhoff, W. J. 1990, A&A, 227, 542 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Henning, T., Michel, B., & Stognienko, R. 1995, Planet. Space Sci., 43, 1333 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]