| Issue |

A&A

Volume 512, March-April 2010

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A85 | |

| Number of page(s) | 12 | |

| Section | Extragalactic astronomy | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/200913045 | |

| Published online | 09 April 2010 | |

Chemical evolution models for the dwarf spheroidal galaxies Leo 1 and Leo 2

G. A. Lanfranchi1 - F. Matteucci2,3

1 - Núcleo de Astrofísica Teórica, Universidade

Cruzeiro do Sul, R. Galvão Bueno 868, Liberdade, 01506-000, São Paulo, SP, Brazil

2 - Dipartimento di Astronomia-Universitá di Trieste, via G. B.

Tiepolo 11, 34131 Trieste, Italy

3 - INAF Osservatorio Astronomico di Trieste, via G.B. Tiepolo

11, 34131, Italy

Received 31 July 2009 / Accepted 17 December 2009

Abstract

Context. We investigate the chemical evolutionary history of

the dwarf spheroidal galaxies Leo 1 and Leo 2 by means of

predictions from a detailed chemical evolution model compared to

observations. The model adopts up to date nucleosynthesis and takes

into account the role played by supernovae of different types (Ia, II),

allowing us to follow in detail the evolution of several chemical

elements (H, D, He, C, N, O, Mg, Si, S, Ca, Fe, Ba, and Eu).

Aims. Each galaxy model is specified by the prescriptions of the

star formation rate and by the galactic wind efficiency chosen to

reproduce the main features of these galaxies, in particular the

stellar metallicity distributions and several abundance ratios. These

parameters are constrained by the star formation histories of the

galaxies as inferred by the observed color-magnitude diagrams,

indicating extended star formation episodes occurring at early epochs,

but also with hints of intermediate stellar populations.

Methods. The main observed features of the galaxies Leo 1

and Leo 2 can be very well explained by chemical evolution models

according to the following scenarios: the star formation occurred in

two long episodes at 14 Gyr and 9 Gyr ago that lasted 5 and

7 Gyr, respectively, with a low efficiency (

![]() )

in Leo 1, whereas the star formation history in Leo 2 is

characterized by one episode at 14 Gyr ago that lasted 7 Gyr,

also with a low efficiency (

)

in Leo 1, whereas the star formation history in Leo 2 is

characterized by one episode at 14 Gyr ago that lasted 7 Gyr,

also with a low efficiency (

![]() ). In both galaxies an intense wind (nine and eight times the star formation rate - wi

= 9 and 8 in Leo 1 and Leo 2, respectively) takes place which defines

the pattern of the abundance ratios and the shape of the stellar

metallicity distribution at intermediate to high metallicities.

). In both galaxies an intense wind (nine and eight times the star formation rate - wi

= 9 and 8 in Leo 1 and Leo 2, respectively) takes place which defines

the pattern of the abundance ratios and the shape of the stellar

metallicity distribution at intermediate to high metallicities.

Results. The observational constraints can only be reproduced with the assumption of gas removal by galactic winds.

Key words: Local Group - galaxies: evolution - galaxies: dwarf - galaxies: abundances

1 Introduction

Local dwarf spheroidal (dSph) galaxies have been the subject of a series of studies both from the observational and

theoretical point of view in the past few years (Shetrone et al. 2003; Tolstoy et al. 2003; Venn et al. 2004;

Lanfranchi ![]() Matteucci 2003, 2004; Bonifacio et al. 2004; Monaco et al. 2005; Geisler et al. 2005;

Fenner et al. 2006; Helmi et al. 2006; Marcolini et al. 2006; Koch et al. 2006; Sbordone et al. 2007;

Shetrone et al. 2009; Revaz et al. 2009). From all these works emerged a scenario in which these galaxies are

characterized by low metallicities, a sharp

decrease of [

Matteucci 2003, 2004; Bonifacio et al. 2004; Monaco et al. 2005; Geisler et al. 2005;

Fenner et al. 2006; Helmi et al. 2006; Marcolini et al. 2006; Koch et al. 2006; Sbordone et al. 2007;

Shetrone et al. 2009; Revaz et al. 2009). From all these works emerged a scenario in which these galaxies are

characterized by low metallicities, a sharp

decrease of [![]() /Fe] ratios at high metallicities, and by a stellar metallicity distribution (SMD) with a peak at

low [Fe/H], a low number of metal-poor stars, and a sharp decline at the high-metallicity tail. Besides that, the

results from color-magnitude diagrams (CMD) indicate that these galaxies exhibit complex star formation histories, that

differ from one system to another. Almost all of them show signs of an ancient population of stars, but several are also

marked by intermediate populations and even by very recent star formation (Hernandez et al. 2000; Bellazzini et al.

2002; Carrera et al. 2002; Dolphin et al. 2005,

and references therein). Carina for example probably suffered four

episodes of star formation, two of them at early epochs (between 14 and

10 Gyr ago) and two more recently (Rizzi et al. 2003). Another striking feature of the dSphs is that they are almost totally depleted of neutral gas in their central

regions.

/Fe] ratios at high metallicities, and by a stellar metallicity distribution (SMD) with a peak at

low [Fe/H], a low number of metal-poor stars, and a sharp decline at the high-metallicity tail. Besides that, the

results from color-magnitude diagrams (CMD) indicate that these galaxies exhibit complex star formation histories, that

differ from one system to another. Almost all of them show signs of an ancient population of stars, but several are also

marked by intermediate populations and even by very recent star formation (Hernandez et al. 2000; Bellazzini et al.

2002; Carrera et al. 2002; Dolphin et al. 2005,

and references therein). Carina for example probably suffered four

episodes of star formation, two of them at early epochs (between 14 and

10 Gyr ago) and two more recently (Rizzi et al. 2003). Another striking feature of the dSphs is that they are almost totally depleted of neutral gas in their central

regions.

What is the link between all these characteristics? How can all of them

be joined in a consistent scenario for the formation and evolution of

all the dSph galaxies? There is a general consensus that the removal of

the gas content of the galaxy is the main factor in modeling the

observed metallicity patterns and SMDs, and driving the evolution of

the dSph galaxies. The mechanism responsible for the gas loss is,

however, still a matter of debate. Is it an internal mechanism (such as

galactic winds) or external (ram pressure, tidal stripping)? Several

works have favored either one or the other suggestion (van den Bergh 1994; Burkert ![]() Ruiz-Lapuente 1997; Ferrara

Ruiz-Lapuente 1997; Ferrara ![]() Tolstoy 2000; Fragile et al. 2003; Robertson et al. 2005).

One way to approach this question is to search for isolated dSph

galaxies and to investigate their evolution. If isolated dSph galaxies

exhibit chemical properties similar to those near large galaxies, the

argument that the gas loss is caused by an internal mechanism like

galactic winds, would be strengthened (see also Shetrone et al. 2009).

One should keep in mind though, that even the more distant dSph

galaxies are not free of any interaction with the Galaxy in the past.

Tidal interactions of the Milky Way with other galaxies (Mayer

et al. 2001; Kroupa et al. 2005; Metz et al. 2009) and

resonant stripping have been suggested as possible scenarios for the

formation of local dSph galaxies. In this case, even galaxies with

large galactocentric distances could have had their evolution affected

by external factors which would have removed a large fraction of their

gas content.

Tolstoy 2000; Fragile et al. 2003; Robertson et al. 2005).

One way to approach this question is to search for isolated dSph

galaxies and to investigate their evolution. If isolated dSph galaxies

exhibit chemical properties similar to those near large galaxies, the

argument that the gas loss is caused by an internal mechanism like

galactic winds, would be strengthened (see also Shetrone et al. 2009).

One should keep in mind though, that even the more distant dSph

galaxies are not free of any interaction with the Galaxy in the past.

Tidal interactions of the Milky Way with other galaxies (Mayer

et al. 2001; Kroupa et al. 2005; Metz et al. 2009) and

resonant stripping have been suggested as possible scenarios for the

formation of local dSph galaxies. In this case, even galaxies with

large galactocentric distances could have had their evolution affected

by external factors which would have removed a large fraction of their

gas content.

The dSph galaxies Leo 1 and Leo 2 are excellent

objects to perform the analysis of isolated systems. They are among the

most distant dSph satellites in the Milky Way system (![]() 270 Kpc and

270 Kpc and ![]() 204 Kpc,

respectively) and probably free from any present-day dynamical

influence from the Milky Way. To understand the processes which played

a major role on the evolution of these two galaxies would provide very

important clues in the study of dSph galaxies as a whole. Similar to

other nearby dSph galaxies, they are characterized by low metallicities

and exhibit the same

204 Kpc,

respectively) and probably free from any present-day dynamical

influence from the Milky Way. To understand the processes which played

a major role on the evolution of these two galaxies would provide very

important clues in the study of dSph galaxies as a whole. Similar to

other nearby dSph galaxies, they are characterized by low metallicities

and exhibit the same ![]() -element

deficiency at high metallicities. Besides that, the metallicity peak of

their main stellar populations in the SMDs is located at low [Fe/H] (

-element

deficiency at high metallicities. Besides that, the metallicity peak of

their main stellar populations in the SMDs is located at low [Fe/H] (![]() -1.4 dex

and -1.6 dex in Leo 1 and Leo 2, respectively) followed

by a steep decline at the high metallicity tail (Bosler et al. 2007; Koch et al. 2007a,b; Gullieuszik et al. 2009).

Color-magnitude studies indicate that they both formed stars in the

early epochs of their evolution, but in different fractions. Leo 2

formed the majority of its stars

-1.4 dex

and -1.6 dex in Leo 1 and Leo 2, respectively) followed

by a steep decline at the high metallicity tail (Bosler et al. 2007; Koch et al. 2007a,b; Gullieuszik et al. 2009).

Color-magnitude studies indicate that they both formed stars in the

early epochs of their evolution, but in different fractions. Leo 2

formed the majority of its stars ![]() 7-14 Gyr

ago, whereas the major episode of star formation in Leo 1 occurred

between 1-7 Gyr ago with a minor fraction of stars being formed

before

7-14 Gyr

ago, whereas the major episode of star formation in Leo 1 occurred

between 1-7 Gyr ago with a minor fraction of stars being formed

before ![]() 10 Gyr ago.

10 Gyr ago.

In this work we adopt detailed chemical evolution models with the aim

to provide a consistent scenario for the evolution of these two

galaxies. This scenario should allow us to model and reproduce the

above observational features. We follow the same approach as in our

previous papers regarding other local dSph galaxies (Lanfranchi ![]() Matteucci 2003, 2004; and Lanfranchi et al. 2006a, 2008).

The model for each galaxy is determined mainly by the star formation

rate (SFR) and galactic wind efficiency prescriptions, chosen to

reproduce the main observational constraints. In our model, when the

thermal energy of the interstellar medium (ISM) is equal or higher than

the binding energy of the galaxy, a galactic wind occurs, thus removing

a considerable fraction (depending on the wind efficiency) of the gas

content of the system. This wind is also responsible for a considerable

decrease in the star formation (SF) of the galaxy in the first Gyr

of its evolution. In Lanfranchi

Matteucci 2003, 2004; and Lanfranchi et al. 2006a, 2008).

The model for each galaxy is determined mainly by the star formation

rate (SFR) and galactic wind efficiency prescriptions, chosen to

reproduce the main observational constraints. In our model, when the

thermal energy of the interstellar medium (ISM) is equal or higher than

the binding energy of the galaxy, a galactic wind occurs, thus removing

a considerable fraction (depending on the wind efficiency) of the gas

content of the system. This wind is also responsible for a considerable

decrease in the star formation (SF) of the galaxy in the first Gyr

of its evolution. In Lanfranchi ![]() Matteucci (2003, 2004

- LM03, LM04) we adopted high values for the wind efficiency (from 5 to

10 times the SFR) to reproduce the abundance ratios and the observed

present day gas fraction of each galaxy, given that our models do not

assume any external removal of gas. Later works with the same models

(with no modifications in the main parameters) allowed us also to

reproduce the metallicity distribution of the same dSph galaxies

(Carina, Sagittarius, Draco, and Ursa Minor - Lanfranchi et al. 2006b; Lanfranchi

Matteucci (2003, 2004

- LM03, LM04) we adopted high values for the wind efficiency (from 5 to

10 times the SFR) to reproduce the abundance ratios and the observed

present day gas fraction of each galaxy, given that our models do not

assume any external removal of gas. Later works with the same models

(with no modifications in the main parameters) allowed us also to

reproduce the metallicity distribution of the same dSph galaxies

(Carina, Sagittarius, Draco, and Ursa Minor - Lanfranchi et al. 2006b; Lanfranchi ![]() Matteucci 2007 - LM07) and the abundance ratios of neutron capture elements (Lanfranchi et al. 2006a

- LMC06a). The galaxies so far analyzed are close to our Galaxy and

consequently subject to tidal and dynamical effects. Leo 1 and

Leo 2, on the other hand, are at a large galactocentric distance,

therefore any later removal of gas could be caused by an internal

mechanism like galactic winds.

Matteucci 2007 - LM07) and the abundance ratios of neutron capture elements (Lanfranchi et al. 2006a

- LMC06a). The galaxies so far analyzed are close to our Galaxy and

consequently subject to tidal and dynamical effects. Leo 1 and

Leo 2, on the other hand, are at a large galactocentric distance,

therefore any later removal of gas could be caused by an internal

mechanism like galactic winds.

Different approaches were adopted in the study of these

galaxies leading to scenarios with similarities but also discrepancies

compared to LM03 and LM04 (see Lanfranchi et al. 2007, for more details). In particular, Carigi et al. (2002), Ikuta ![]() Arimoto (2002) and Fenner et al. (2006)

also adopted chemical evolution models in their analysis of local dSph

galaxies. Neither one of them, however, compared their results with the

stellar metallicity distributions observed, which LM consider one of

the strongest constraint in the chemical evolution studies, specially

when one is analyzing the effects of the galactic winds on the

evolution of these galaxies. Besides that, Carigi et al. (2002)

and Ikuta

Arimoto (2002) and Fenner et al. (2006)

also adopted chemical evolution models in their analysis of local dSph

galaxies. Neither one of them, however, compared their results with the

stellar metallicity distributions observed, which LM consider one of

the strongest constraint in the chemical evolution studies, specially

when one is analyzing the effects of the galactic winds on the

evolution of these galaxies. Besides that, Carigi et al. (2002)

and Ikuta ![]() Arimoto (2002) compared their results to a much more limited sample of

stars and did not consider the removal of metals by galactic winds.

Fenner et al. (2006)

on the other hand adopted a more detailed chemical evolution model

compared to a more complete data sample. They argue that the evolution

of several abundance ratios could be reproduced by models with moderate

galactic winds (less efficient than LM04) which are not able to remove

the remaining gas content of the galaxy. They conclude then that an

external mechanism should be acting togheter with the winds. They did

not compare their results to the stellar metallicities distribuitions

of these galaxies however.

Arimoto (2002) compared their results to a much more limited sample of

stars and did not consider the removal of metals by galactic winds.

Fenner et al. (2006)

on the other hand adopted a more detailed chemical evolution model

compared to a more complete data sample. They argue that the evolution

of several abundance ratios could be reproduced by models with moderate

galactic winds (less efficient than LM04) which are not able to remove

the remaining gas content of the galaxy. They conclude then that an

external mechanism should be acting togheter with the winds. They did

not compare their results to the stellar metallicities distribuitions

of these galaxies however.

More recently, Revaz et al. (2009)

followed a completely different approach. By means of hydrodynamical

Nbody/Tree-SPH simluations they studied the evolution of isolated dSph

galaxies. The initial total mass is the main driver of the system in

their simulation, contrary to LM03 and LM04 in which the SF and wind

efficiencies play the major role. Since the final gas mass predicted in

their simulations is much higher than the values inferred by

observations, they claim the necessity of invoking external processes

to remove the gas content that remains at the end of the SF. They also

compared their predictions to the [Mg/Fe] ratio and the stellar

metallicity distribution observed in a few local dSph galaxies. Their

models, however, are not capable of reproducing the lowest values of

[Mg/Fe] as precisely as the higher ones. In fact, the majority of stars

show an almost linear trend of [Mg/Fe] as a function of [Fe/H] (the

green to blue areas in their Fig. 12). Besides that, their SMD

tend to have a peak at metallicities higher than the ones observed even

with the shift of a few tenths of dex. As they have not tried to fit

any galaxy in particular (contrary to LM04 goal), these discrepancies

are not taken into account. In the LM models, the lowest values

observed of [![]() /Fe]

are explained by the effects of intense winds on the star formation

rate. A more direct comparison between the LM scenarios with theirs is

difficult because the main parameters in each simulation are quite

different. LM04 adopt for instance the star formation histories (SFH)

inferred from color-magnitude diagrams for each galaxy as an input of

the models, whereas in Revaz et al. (2009)

the SFH is a consequence of the initial parameters of the simulation.

The parameters representing the efficiency of the SF are also

different, which prevents a more complete comparison.

/Fe]

are explained by the effects of intense winds on the star formation

rate. A more direct comparison between the LM scenarios with theirs is

difficult because the main parameters in each simulation are quite

different. LM04 adopt for instance the star formation histories (SFH)

inferred from color-magnitude diagrams for each galaxy as an input of

the models, whereas in Revaz et al. (2009)

the SFH is a consequence of the initial parameters of the simulation.

The parameters representing the efficiency of the SF are also

different, which prevents a more complete comparison.

The paper is organized as follows: in Sect. 2 we present

the observational data concerning the Leo 1 and Leo 2 dSph

galaxies,

in Sect. 3 we describe the adopted chemical evolution models and

theoretical prescriptions, in Sect. 4 we describe the results of

our models, and finally in Sect. 5 we discuss the results and draw

some conclusions. We use the solar abundances measured by Grevesse ![]() Sauval (1998) when the chemical

abundances are normalized to the solar values

([X/H] = log(X/H) - log(X/H)

Sauval (1998) when the chemical

abundances are normalized to the solar values

([X/H] = log(X/H) - log(X/H)![]() ).

).

2 Data sample

The observed data collected in this work and used as main constraints for the comparison with the model predictions are based on particular abundance ratios and stellar metallicity distributions. Abundance ratios are powerful tools in the study of the chemical evolution of galaxies because they depend mainly on the nucleosynthesis prescriptions, stellar lifetimes and adopted initial mass function (IMF), and not on the other model parameters. The stellar metallicity distributions, on the other hand, are representative of the chemical enrichment of the galaxy and provide information about the history of the chemical evolution and how it proceeded (LM04). Hence, these two observables together provide strong constraints on chemical evolution models and limit the range of acceptable values for several other model parameters.

We compared the predictions of the model with [![]() /Fe],

[r, s/Fe], and the stellar metallicity distributions observed in both

galaxies. For Leo 1 we used the abundance data from Shetrone

et al. (2003) with the update from Venn et al. (2004). In this case the abundance ratios include [

/Fe],

[r, s/Fe], and the stellar metallicity distributions observed in both

galaxies. For Leo 1 we used the abundance data from Shetrone

et al. (2003) with the update from Venn et al. (2004). In this case the abundance ratios include [![]() /Fe],

[Ba/Fe], and [Eu/Fe], but only for two stars. Even though the sample is

limited, it is enough to complement the comparison with the metallicity

distribution. Many more stars were observed in Leo 2 (almost 30),

but only [Mg/Fe] and [Ca/Fe] were inferred (Shetrone et al. 2009).

For this galaxy the analysis of the abundance ratios is also

complemented by the metallicity distribution. The observed stellar

metallicity distributions for both galaxies were taken from Koch

et al. (2007a - Leo 1, 2007b - Leo 2), Bosler et al. (2007), and Gullieuszik et al. (2009). In the papers from Koch et al. (2007a,b) and Gullieuszik et al. (2009)

the abundance of iron ([Fe/H]) is inferred from the Ca triplet lines

(CaT). One should take care though when such a procedure is adopted in

extragalactic stars. The calibration of the Ca II lines and the

transformation into Fe abundance contains several uncertainties. For

example, calcium and iron are formed in totally different

nucleosynthesis processes and consequently do not trace each other

directly. One should therefore take into account the variations of

[Ca/Fe] in the course of the evolution of the galaxy in the

calibration. Normally this is done for Galactic globular cluster stars,

which do not share the same star formation histories and abundance

ratio patterns as the stars in dSph galaxies. In order to avoid the

fundamental dependence on [Ca/Fe] ratios built into CaII calibrations,

Bosler et al. (2007)

adopted also [Ca/H] as a metallicity indicator. In this work both the

metallicity distribution as a function of both [Fe/H] and [Ca/H] are

compared to the predictions of the models.

/Fe],

[Ba/Fe], and [Eu/Fe], but only for two stars. Even though the sample is

limited, it is enough to complement the comparison with the metallicity

distribution. Many more stars were observed in Leo 2 (almost 30),

but only [Mg/Fe] and [Ca/Fe] were inferred (Shetrone et al. 2009).

For this galaxy the analysis of the abundance ratios is also

complemented by the metallicity distribution. The observed stellar

metallicity distributions for both galaxies were taken from Koch

et al. (2007a - Leo 1, 2007b - Leo 2), Bosler et al. (2007), and Gullieuszik et al. (2009). In the papers from Koch et al. (2007a,b) and Gullieuszik et al. (2009)

the abundance of iron ([Fe/H]) is inferred from the Ca triplet lines

(CaT). One should take care though when such a procedure is adopted in

extragalactic stars. The calibration of the Ca II lines and the

transformation into Fe abundance contains several uncertainties. For

example, calcium and iron are formed in totally different

nucleosynthesis processes and consequently do not trace each other

directly. One should therefore take into account the variations of

[Ca/Fe] in the course of the evolution of the galaxy in the

calibration. Normally this is done for Galactic globular cluster stars,

which do not share the same star formation histories and abundance

ratio patterns as the stars in dSph galaxies. In order to avoid the

fundamental dependence on [Ca/Fe] ratios built into CaII calibrations,

Bosler et al. (2007)

adopted also [Ca/H] as a metallicity indicator. In this work both the

metallicity distribution as a function of both [Fe/H] and [Ca/H] are

compared to the predictions of the models.

3 Models

In order to study the chemical enrichment in Leo 1 and

Leo 2 dSph galaxies, we adopted the same models as in previous

works (LM04). These models adopt up-to-date nucleosynthesis yields for

intermediate-mass stars (IMS) and supernovae (SNe) of both types (type

Ia and type II) as well as the effects of SNe and stellar winds on the

energetics of the interstellar medium. They are able to reproduce very

well several observational constraints of six local dSph galaxies (in

particular, Carina, Draco, Sagittarius, Sextan, Sculptor, and Ursa

Minor), like [![]() /Fe],

[s-r/Fe], the stellar metallicity distributions, and the present day

gas mass and total mass. The scenario adopted for the formation and

evolution of these galaxies considers long episodes of star formation

with low rates and the occurrence of very intense galactic winds. As

shown in LM03 and LMC06a, the low SFR is required to account for the

low values of [

/Fe],

[s-r/Fe], the stellar metallicity distributions, and the present day

gas mass and total mass. The scenario adopted for the formation and

evolution of these galaxies considers long episodes of star formation

with low rates and the occurrence of very intense galactic winds. As

shown in LM03 and LMC06a, the low SFR is required to account for the

low values of [![]() /Fe]

ratios, whereas the observed stellar metallicity distribution cannot be

reproduced without invoking strong and efficient galactic winds (LM07).

/Fe]

ratios, whereas the observed stellar metallicity distribution cannot be

reproduced without invoking strong and efficient galactic winds (LM07).

The evolution of the abundances of several chemical elements

(H, He, C, O, Mg, Si, S, Ca, N, Fe, Ba, La, Eu, Y, and others) can be

followed in detail by the model, starting from the matter reprocessed

by the stars and restored into the ISM by stellar winds and type II and

Ia supernova explosions. The main characteristics of the models are: it

is a one zone model with instantaneous and complete mixing of gas

inside

this zone; no instantaneous recycling approximation (i.e. the stellar

lifetimes are taken into account) is adopted. The nucleosynthesis

prescriptions are the same as in Lanfranchi, Matteucci and Cescutti

(2008 - LMC08). In particular we adopted the yields of Nomoto

et al. (1997) for type Ia supernovae, Woosley ![]() Weaver (1995) (with the corrections suggested by François et al. #Fran&) for massive stars (

Weaver (1995) (with the corrections suggested by François et al. #Fran&) for massive stars (

![]() ), van den Hoek

), van den Hoek ![]() Groenewegen (1997) for intermediate mass stars

(IMS), and the ones described in Cescutti et al. (2006, 2007) and Busso et al. (2001) for

Groenewegen (1997) for intermediate mass stars

(IMS), and the ones described in Cescutti et al. (2006, 2007) and Busso et al. (2001) for ![]() and

and ![]() process elements.

process elements.

The type Ia SN progenitors are assumed to be white dwarfs in binary systems

according to the formalism originally developed by Greggio & Renzini (1983) and Matteucci ![]() Greggio (1986). The prescriptions for the SF (which follow a Schmidt law - Schmidt 1963), initial mass function (IMF - Salpeter 1955),

infall, and galactic winds are the same as in LM03 and LM04. The main

parameters adopted for the model of each galaxy can be seen in

Table 1, where

Greggio (1986). The prescriptions for the SF (which follow a Schmidt law - Schmidt 1963), initial mass function (IMF - Salpeter 1955),

infall, and galactic winds are the same as in LM03 and LM04. The main

parameters adopted for the model of each galaxy can be seen in

Table 1, where ![]() is the star-formation efficiency, wi the wind efficiency, n, t, and d

are the number, time of occurrence, and duration of the SF episodes,

respectively. Besides that also the predicted total luminous mass and

the present day gas mass (Cols. 7 and 8, respectively) are shown.

is the star-formation efficiency, wi the wind efficiency, n, t, and d

are the number, time of occurrence, and duration of the SF episodes,

respectively. Besides that also the predicted total luminous mass and

the present day gas mass (Cols. 7 and 8, respectively) are shown.

In our scenario, the dSph galaxies form through

a continuous infall of pristine gas until a luminous mass of

![]()

![]() is accumulated. One crucial

feature in the evolution of these galaxies is the occurrence

of galactic winds, which develop when the thermal

energy of the gas equals its binding energy (Matteucci

is accumulated. One crucial

feature in the evolution of these galaxies is the occurrence

of galactic winds, which develop when the thermal

energy of the gas equals its binding energy (Matteucci ![]() Tornambé 1987). This quantity is strongly influenced by

assumptions concerning the presence and distribution

of dark matter (Matteucci 1992). A diffuse (

Tornambé 1987). This quantity is strongly influenced by

assumptions concerning the presence and distribution

of dark matter (Matteucci 1992). A diffuse (

![]() ,

where

,

where ![]() is the effective radius of the galaxy and

is the effective radius of the galaxy and ![]() is

the radius of the dark matter core) but massive

(

is

the radius of the dark matter core) but massive

(

![]() )

dark halo has been assumed for each galaxy.

The effects of changing the dark matter and its distribution in dwarf galaxies were explored in Bradamante et al. (1998).

A larger dark matter halo and/or a more concentrated dark matter

distribution will make the occurrence of the wind more difficult and

therefore more metal rich stars will be predicted in the stellar

metallicity distributions. Besides that, the sharp decrease observed in

the abundance ratios would take place at higher metallicities than

observed since this decrease is associated to the onset of the wind.

With a larger/more concentrated dark matter halo the wind would take

longer to develop, since more thermal energy would be required.

)

dark halo has been assumed for each galaxy.

The effects of changing the dark matter and its distribution in dwarf galaxies were explored in Bradamante et al. (1998).

A larger dark matter halo and/or a more concentrated dark matter

distribution will make the occurrence of the wind more difficult and

therefore more metal rich stars will be predicted in the stellar

metallicity distributions. Besides that, the sharp decrease observed in

the abundance ratios would take place at higher metallicities than

observed since this decrease is associated to the onset of the wind.

With a larger/more concentrated dark matter halo the wind would take

longer to develop, since more thermal energy would be required.

Table 1: Models with galactic winds for the dSph galaxies Leo 1 and Leo 2.

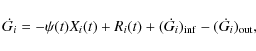

3.1 Theoretical prescriptions

The basic equation that describes the evolution in time

of the fractional mass of the element i in the gas

within a galaxy, Gi, is the same as described

in Tinsley (1980) and Matteucci (1996,b):

|

(1) |

where

The SFR ![]() has a simple form and is given by

has a simple form and is given by

| (2) |

where

In order to get the best agreement with the abundance ratios and the metallicity distribution, wi and ![]() are varied in

each galaxy following the procedure of LM03.

The star formation is not halted even after the onset of the

galactic wind, but proceeds at a lower rate, since a large

fraction of the gas (

are varied in

each galaxy following the procedure of LM03.

The star formation is not halted even after the onset of the

galactic wind, but proceeds at a lower rate, since a large

fraction of the gas (![]()

![]() of the total lumionius mass) is carried out of the galaxy.

The details of the star formation are given by the star

formation history of each individual galaxy as inferred by

observed color-magnitude diagrams (CMD) in Dolphin et al. (2005, see Table 1 for more details).

of the total lumionius mass) is carried out of the galaxy.

The details of the star formation are given by the star

formation history of each individual galaxy as inferred by

observed color-magnitude diagrams (CMD) in Dolphin et al. (2005, see Table 1 for more details).

The rate of gas infall is defined as

| (3) |

with A a suitable constant and

The rate of gas loss via galactic winds for each element

i is assumed to be proportional to the star formation

rate at the time t

| (4) |

where wi is a free parameter describing the efficiency of the galactic wind, which is the same for all heavy elements.

4 Results

The predictions of the chemical evolution models for Leo 1 and

Leo 2 were compared with the available observational data of these

two galaxies. In particular, the evolution of several [![]() /Fe]

ratios (Ca, Si, O and Mg), [s-process/Fe], [r-process/Fe], and the

stellar metallicity distribution were used as main constraints. We

considered two stellar metallicity distributions, one as a function of

[Fe/H] and another as a function of [Ca/H]. In fact, the observed

[Fe/H] were derived from the Ca triplet lines and may not trace the

effective iron abundance (Lanfranchi et al. 2006 -LMC06b; Bosler

et al. 2004, 2007),

as predicted in the models. The abundance of Ca on the other hand was

inferred through the atmospheric abundance analysis of neutral calcium

and was corrected for non-LTE effects

/Fe]

ratios (Ca, Si, O and Mg), [s-process/Fe], [r-process/Fe], and the

stellar metallicity distribution were used as main constraints. We

considered two stellar metallicity distributions, one as a function of

[Fe/H] and another as a function of [Ca/H]. In fact, the observed

[Fe/H] were derived from the Ca triplet lines and may not trace the

effective iron abundance (Lanfranchi et al. 2006 -LMC06b; Bosler

et al. 2004, 2007),

as predicted in the models. The abundance of Ca on the other hand was

inferred through the atmospheric abundance analysis of neutral calcium

and was corrected for non-LTE effects

The SF timescale in the galaxy and the nucleosynthesis of

several chemical elements can be analyzed through particular abundance

ratios due to the difference in the formation and injection of these

elements into the ISM. The [![]() /Fe] ratio for instance can be used as a ``chemical clock'' since

/Fe] ratio for instance can be used as a ``chemical clock'' since ![]() -elements

are produced mainly in SNe II explosions in short timescales,

whereas explosions of SNe Ia are the main site for the production of

Fe-peak elements on a much longer timescale. Consequently, a long SF

timescale and an older age are characterized by low [

-elements

are produced mainly in SNe II explosions in short timescales,

whereas explosions of SNe Ia are the main site for the production of

Fe-peak elements on a much longer timescale. Consequently, a long SF

timescale and an older age are characterized by low [![]() /Fe] values whereas a high [

/Fe] values whereas a high [![]() /Fe]

ratio is the result of a short SF timescale and a younger age.

Abundance ratios between neutron process elements are also used to

impose constraints in the SF timescale and in the formation of the

elements when r-process elements are compared to s-process, since the

main site of the production of these two types of elements are quite

different: the main source of r-process elements are SNe II

explosions, whereas low and intermediate mass stars (LIMS) are believed

to be the main site for the production of s-process elements (Woosley

et al. 1994; Gallino et al. 1998; Freiburghaus et al. 1999; Busso et al. 2001; Wanajo et al. 2003).

/Fe]

ratio is the result of a short SF timescale and a younger age.

Abundance ratios between neutron process elements are also used to

impose constraints in the SF timescale and in the formation of the

elements when r-process elements are compared to s-process, since the

main site of the production of these two types of elements are quite

different: the main source of r-process elements are SNe II

explosions, whereas low and intermediate mass stars (LIMS) are believed

to be the main site for the production of s-process elements (Woosley

et al. 1994; Gallino et al. 1998; Freiburghaus et al. 1999; Busso et al. 2001; Wanajo et al. 2003).

Besides abundance ratios, SMDs can be used as powerful tools to investigate the chemical evolution of the galaxy. The general shape of the distribution along with its details can reveal how the stars formed and evolved in a galaxy and also impose constraints on the physical process acting on it. An absence of a metal-poor tail can be the consequence of a pre-enriched gas from which the stars formed, or the result of a slow infall of gas. Besides that, the position of the peak of the distribution is related to the SFR (if it is low or high) and to the duration of the SF episode (or episodes) as well as to the assumed IMF, and the metal-rich tail can impose constraints on the occurrence of galactic winds and in their efficiency in removing the gas of the system.

By comparing the predictions of our model with key abundance ratios and the SMD observed in Leo1 and Leo 2 we hope to improve the understanding of the chemical evolution of these systems. In particular, we suggest a scenario for the formation and evolution of these galaxies by describing some of its main parameters such as the star formation history, the SFR, the IMF, the occurrence of galactic winds and how efficiently they removed the gas out of the galaxy, the epoch the SF was halted, and others.

In this work, however, the strongest observational constrains on the model's parameters come from the stellar metallicity distribution due to the particularities of the adopted data sample, specially the ones concerning the abundance ratios (low number of stars in Leo 1 and large dispersion in Leo 2). The abundance ratios are used as a first filter, which allows us to pre-define the IMF, the SFH and a range (a broad one in this case) of acceptable values for the star formation and galactic wind efficiencies. A best model is then defined with specific values for these two parameters (within the range of values) and for the infall timescale based on the special features of the stellar metallicity distributions of each galaxy.

4.1 Leo 1

Leo 1 is one of the most distant dSph galaxies in the Local Group believed to be associated to the Milky Way. A few studies concerning the chemical evolution of Leo 1 have been published in the last few years, most of them focused in the star formation history, chemical abundances and the stellar metallicity distribution (Gallart et al. 1999; Held et al. 2000; Tolstoy et al. 2003; Shetrone et al. 2003; Dolphin et al. 2005; Bosler et al. 2007; Koch et al. 2007b). The main stellar population of Leo 1 seems to be very old (Held et al. 2001; Tolstoy et al. 2003), as in many other dSph, but there are also hints of a younger population which would have been formed between 1 to 7 Gyr ago (Gallart et al. 1999; Dolphin et al. 2005). The differences in the star formation histories (SFH) and their consequences in the evolution of the galaxy can be addressed by detailed chemical evolution studies, which take into account other processes like the inflow and outflow of gas (LMC06b).

The SMD and abundance ratios can also provide some clues to the formation and evolution of Leo1. Unfortunately, there are only a few stars with spectroscopic abundance measurementsfor this galaxy (Shetrone et al. 2003), which by themselves do not allow one to draw any firm conclusion about the evolution of the galaxy. However, when these abundances are analyzed together with the SMD a definite scenario emerges. As mentioned previously, since the number of stars with determined abundance ratios is small, the stellar metallicity distribution turns out to be the strongest constraint on the models. The SMD of Leo 1 was recently studied in detail by Gullieuszik et al. (2009), Koch et al. (2007b), and Bosler et al. (2007). In all cases, the CaT method was used to derive the [Fe/H], and the mean metallicity found was between [Fe/H] = -1.31 dex (Koch et al. 2007b) and -1.40 dex (Gullieuszik et al. 2009), with an intermediate value of [Fe/H] = -1.34 dex found by Bosler et al. (2007). Bosler et al. (2007) also derived [Ca/H] and found a mean value of -1.34 dex. The SMD is well described by Bosler et al. (2007) and Koch et al. (2007b) by a Gaussian function with a full range in metallicity of approximately 1.0 dex.

All these features together lead to a scenario in which the dSph galaxy Leo 1 is characterized by a fast enrichment from an initial generation of stars followed by a loss of metals by efficient galactic winds, as suggested by the results of simple closed-box models (Koch et al. 2007b; Gullieuszik et al. 2009). Besides that, Gullieuszik et al. (2009) suggested also that the first generation of stars in the galaxy was formed by pre-enriched gas to account for the apparent lack of metal-poor stars in the stellar metallicity distribution, whereas Koch et al. (2007b) claim that the galaxy should not have been affected by Galactic tides, as it represents an isolated system.

By means of a detailed chemical evolution model with inflow and outflow of gas compared to the observed data, we investigated the proposed scenarios for the evolution of Leo 1.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{13045f01}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/04/aa13045-09/Timg31.png)

|

Figure 1: [X/Fe] vs. [Fe/H] observed in the dSph galaxy Leo 1 compared to the predictions of the best model (solid line). The dashed lines represent the upper and lower limits of the predictions. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

4.1.1 Abundance ratios

First we compare the predictions for the Leo 1 model to the observed abundance ratios of several species like [![]() /Fe] and [Ba, Eu/Fe] (Fig. 1).

Even though the number of points is low we are able to gain some

insight into the SF and galactic wind efficiencies by defining the

upper and lower limits of a range of values for these two parameters.

This range of values allows the model to account for the majority of

points (models Leo1a and Leo1c - Table 1).

A low SF efficiency (

/Fe] and [Ba, Eu/Fe] (Fig. 1).

Even though the number of points is low we are able to gain some

insight into the SF and galactic wind efficiencies by defining the

upper and lower limits of a range of values for these two parameters.

This range of values allows the model to account for the majority of

points (models Leo1a and Leo1c - Table 1).

A low SF efficiency (

![]() -1.7 Gyr-1) gives rise to values of [

-1.7 Gyr-1) gives rise to values of [![]() /Fe] above solar and very low [s,r/Fe] at low metallicities ([Fe/H] < -3.0 dex). As the metallicity increases, [

/Fe] above solar and very low [s,r/Fe] at low metallicities ([Fe/H] < -3.0 dex). As the metallicity increases, [![]() /Fe] decreases slowly, whereas [Ba, Eu/Fe] increases fast at [Fe/H]

/Fe] decreases slowly, whereas [Ba, Eu/Fe] increases fast at [Fe/H] ![]() -3.0 dex and then reaches some kind of a plateau around solar values. The decrease in [

-3.0 dex and then reaches some kind of a plateau around solar values. The decrease in [![]() /Fe]

is a consequence of the slow injection of Fe into the ISM by SNe Ia,

which starts to explode from several Myr to several Gyr after the

first explosions of SNe II (responsible for the main component of

alpha and r-produced elements). In [Ba, Eu/Fe], the increase is a

result of the production by r-process of these elements in SNe II

explosions originating from stars with masses inferior to M = 30

/Fe]

is a consequence of the slow injection of Fe into the ISM by SNe Ia,

which starts to explode from several Myr to several Gyr after the

first explosions of SNe II (responsible for the main component of

alpha and r-produced elements). In [Ba, Eu/Fe], the increase is a

result of the production by r-process of these elements in SNe II

explosions originating from stars with masses inferior to M = 30 ![]() .

.

From intermediate to high metallicities ([Fe/H] > -1.5 dex) one can notice a steep decline in [![]() /Fe]

and [Eu/Fe] and a smoother one for [Ba/Fe] (the oscilations seen around

[Fe/H] = -1.5 dex in the bottom panels are caused by

small numerical fluctuations in the code). This sudden change in the

abundance patterns is a consequence of the occurrence of a strong

galactic wind (wi = 6-10) when the thermal

energy of the galaxy equates or exceeds its binding energy. The main

factor that affects the thermal energy of the gas is the energy

injected into the medium by SNe explosions, which gives rise to a wind

short after the first generation of SNe Ia (depending on the SF

efficiency). With the onset of the galactic wind the gas content of the

ISM starts to be removed from the galaxy and therefore the SFR starts

to decrease. The number of new stars formed after the onset of the wind

is much lower, as is the amount of alpha elements and Eu (r-processed

element) injected into the ISM. The main source of these elements

(SNe II explosions) originates from massive stars which evolve and

die fast (tens to hundred Myr), enriching the medium soon after they

are formed. Iron on the other hand, is produced mainly in SNe Ia during

a much longer time. Because of that the ISM continues to be enriched in

Fe even after the onset of the wind by the stars which were born before

the wind started and died only afterwards.

/Fe]

and [Eu/Fe] and a smoother one for [Ba/Fe] (the oscilations seen around

[Fe/H] = -1.5 dex in the bottom panels are caused by

small numerical fluctuations in the code). This sudden change in the

abundance patterns is a consequence of the occurrence of a strong

galactic wind (wi = 6-10) when the thermal

energy of the galaxy equates or exceeds its binding energy. The main

factor that affects the thermal energy of the gas is the energy

injected into the medium by SNe explosions, which gives rise to a wind

short after the first generation of SNe Ia (depending on the SF

efficiency). With the onset of the galactic wind the gas content of the

ISM starts to be removed from the galaxy and therefore the SFR starts

to decrease. The number of new stars formed after the onset of the wind

is much lower, as is the amount of alpha elements and Eu (r-processed

element) injected into the ISM. The main source of these elements

(SNe II explosions) originates from massive stars which evolve and

die fast (tens to hundred Myr), enriching the medium soon after they

are formed. Iron on the other hand, is produced mainly in SNe Ia during

a much longer time. Because of that the ISM continues to be enriched in

Fe even after the onset of the wind by the stars which were born before

the wind started and died only afterwards.

This sudden interruption in the production of Eu and alpha elements combined with the injection of Fe in the ISM by SN Ia leads to the sharp decrease in the predictions of the model, similar to what is observed in the data. Barium, unlike Eu and the alpha elements, has two main different productions - from the s and from the r process. As mentioned before, SNe II explosions are believed to be the site for the production of r-processed elements, but the s-process is claimed to take place in low and intermediate mass stars (LIMS) (Busso et al. 2001; Woosley et al. 1994). Consequently, the s-process component of Ba continues to be injected into the ISM for a few Gyr (the timescale of LIMS), which causes a smoother decline in [Ba/Fe].

It is evident from all this that the efficiency with which the

galactic wind removes the gas of the galaxy is crucial in determining

the pattern of the abundance ratios, especially at high metallicities

where the galactic wind plays a major role. If the gas removal is not

efficient enough (wi ![]() 1, for instance), the decrease in the predictions does not reach the lowest values observed, in particular for [

1, for instance), the decrease in the predictions does not reach the lowest values observed, in particular for [![]() /Fe]. These can only be reproduced by a wind with a rate several times higher than the

/Fe]. These can only be reproduced by a wind with a rate several times higher than the ![]() - wi = 6-10 in the case of Leo 1. Besides that, the low SF efficiency (

- wi = 6-10 in the case of Leo 1. Besides that, the low SF efficiency (

![]() Gyr-1) explains the patterns observed. If

Gyr-1) explains the patterns observed. If ![]() is higher than that, the predictions of all abundance ratios at low

metallicities will be also higher, the wind will develop at higher

[Fe/H], shifting the decrease towards the right in the plots, and the

agreement between predictions and data will be lost. The stellar

metallicity distribution is also strongly affected by these parameters

as we will discuss below.

is higher than that, the predictions of all abundance ratios at low

metallicities will be also higher, the wind will develop at higher

[Fe/H], shifting the decrease towards the right in the plots, and the

agreement between predictions and data will be lost. The stellar

metallicity distribution is also strongly affected by these parameters

as we will discuss below.

4.1.2 The stellar metallicity distribution

The general shape, the low and high-metallicity tails, and the position of the peak of the stellar metallicity distribution are strongly affected by the choice of parameters of the chemical evolution model. By comparing the predictions of the model with the observed data we are able to verify and in particular narrow the range of values for the main parameters (specially the wind and SF efficiencies) already selected from the comparison with the abundance ratios. The SMD, in this sense, allows one to define a best model with specific values for the star formation and galactic wind efficiencies within the range of values determined by the comparison with the abundance ratios and to test the previous choice of the IMF and the infall timescale. The upper and lower values previously determined could be interpreted as limits of the model's predictions.

The predictions of the best model for Leo 1 (Leo1b -

straight line) compared to the observed SMDs (long dashed line) are

show in Figs. 2 and 3

(as a function of [Fe/H] and [Ca/H], respectively) together wiht the

upper and lower models. In both cases the general shape of the

distribution, the position of the peak and the low metallicity tail can

be well reproduced by the predictions of the best model (Leo1b). It

adopts in particular values near the lower limit for the efficiency of

the star formation (![]() Gyr-1), whereas for the galactic wind efficiency the best value is near the higher limit (wi = 9).

Gyr-1), whereas for the galactic wind efficiency the best value is near the higher limit (wi = 9).

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{13045f02}\vspace*{2mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/04/aa13045-09/Timg37.png)

|

Figure 2: The stellar metallicity distribution as a function of [Fe/H] observed in the dSph galaxy Leo 1 (long dashed line) compared to the predictions of the best model (solid line). The short dashed lines represent the upper and lower limits of the predictions. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{13045f03}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/04/aa13045-09/Timg38.png)

|

Figure 3: The stellar metallicity distribution as a function of [Ca/H] observed in the dSph galaxy Leo 1 (long dashed line) compared to the predictions of the best model (solid line). The short dashed lines represent the upper and lower limits of the predictions. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

At low metallicities, the low number of stars observed is very well reproduced by the best model in both cases (the fit for [Ca/H] is excellent) without the need to adopt a pre-enriched gas to form the galaxy, as suggested by Gullieuszik et al. (2009). The very low SF efficiency and the infall timescale are the main factors leading to this scenario. The gradual formation of the galaxy ensures that few metal poor stars form since there is little gas at the very beginning and SNeII rapidly pollute the infalling gas.

The position of the peaks in both distributions (as a function

of [Fe/H] and of [Ca/H]) at metallicities much lower than the one of

the SMD from the solar neighborhood ([Fe/H] ![]() -1.4 dex and

-1.4 dex and

![]() dex,

respectively) is a consequence of the low SFR coupled with the

occurrence of a galactic wind. Of great importance in this case is the

efficiency of the galactic wind, i.e. the rate at which the gas is

removed from the galaxy. With a large efficiency (wi = 9), the wind removes a large fraction (

dex,

respectively) is a consequence of the low SFR coupled with the

occurrence of a galactic wind. Of great importance in this case is the

efficiency of the galactic wind, i.e. the rate at which the gas is

removed from the galaxy. With a large efficiency (wi = 9), the wind removes a large fraction (![]()

![]() )

of the gas content of the galaxy as soon as it starts. As a

consequence, the number of stars which are formed with metallicities

higher than the gas metallicity at the time of the beginning of the

wind is reduced dramatically.

)

of the gas content of the galaxy as soon as it starts. As a

consequence, the number of stars which are formed with metallicities

higher than the gas metallicity at the time of the beginning of the

wind is reduced dramatically.

The high wind efficiency also defines the shape of the metal-rich tail

of the distribution. As can be seen in the data, the more metal-rich

stars do not reach metallicities as high as [Fe/H] ![]() -0.5 dex,

and the decline in the SMD is very sharp after the peak. This is

normally explained as due to the termination of the SF. In the models

the SF is not halted, but substantially decreased after the wind starts

to sweep away the ISM gas from the galaxy. In the model predictions,

however, a difference can be noticed between the two distributions

(Figs. 2 and 3).

The SMD as a function of [Ca/H] exhibits a very sharp decrease at high

metallicities, whereas the one as a function of [Fe/H] is more

symmetric. This difference can be explained by taking into account the

different sites of the production of Fe and Ca. Both elements are

produced partially in SNe II and partially in SNe Ia, but the

fraction of each element that is produced in each type of supernovae is

very different. Ca is mainly produced by SNe II on a short

timescale, whereas the main fraction of Fe is produced on a much longer

timescale, by SNe Ia. Even after the SF has become very low (the wind

is carrying gas away), a considerable fraction of Fe is injected into

the ISM contrary to Ca, whose enrichment is almost stopped after the

wind. Therefore the differences between the two observed SMDs could be

attributed to this fact, but partly also to the procedure adopted to

estimate the abundances of the two elements (Fe and Ca) and to the

different data sets used to construct the two SMDs.

-0.5 dex,

and the decline in the SMD is very sharp after the peak. This is

normally explained as due to the termination of the SF. In the models

the SF is not halted, but substantially decreased after the wind starts

to sweep away the ISM gas from the galaxy. In the model predictions,

however, a difference can be noticed between the two distributions

(Figs. 2 and 3).

The SMD as a function of [Ca/H] exhibits a very sharp decrease at high

metallicities, whereas the one as a function of [Fe/H] is more

symmetric. This difference can be explained by taking into account the

different sites of the production of Fe and Ca. Both elements are

produced partially in SNe II and partially in SNe Ia, but the

fraction of each element that is produced in each type of supernovae is

very different. Ca is mainly produced by SNe II on a short

timescale, whereas the main fraction of Fe is produced on a much longer

timescale, by SNe Ia. Even after the SF has become very low (the wind

is carrying gas away), a considerable fraction of Fe is injected into

the ISM contrary to Ca, whose enrichment is almost stopped after the

wind. Therefore the differences between the two observed SMDs could be

attributed to this fact, but partly also to the procedure adopted to

estimate the abundances of the two elements (Fe and Ca) and to the

different data sets used to construct the two SMDs.

Since the abundance of [Fe/H] is normally derived from Ca triplet lines and this procedure can lead to some discrepancies, especially when applied to extragalactic stars, Bosler et al. (2007) estimated also the abundance of [Ca/H]. These authors proposed a new procedure to estimate the metallicity of stars in local galaxies using Ca as an indicator to avoid the dependence of [Fe/H] on [Ca/Fe] built into the CaII calibrations. The [Ca/H] values were determined from an atmospheric abundance analysis of neutral calcium and were corrected for non LTE effects. As the obtained [Ca/H] does not strongly depend on the [Ca/Fe], the stellar ages, and the SFH of the galaxy, Bosler et al. (2007) adopted this abundance as a tracer of the metallicity. Apart from these differences the observed data are not the same in the two plots. In the Ca plot we used only the data from Bosler et al. (2007) (the only work that estimated this abundance), whereas in the Fe plot we put together all the data from Bosler et al. (2007), Koch et al. (2007b) and Gullieuszik et al. (2009). In that sense, even though there could be errors in the determination of [Fe/H], the set of data for this element is more substantial and perhaps not homogeneous. Considering all this and looking for a more complete picture we compared our predictions with both SMD.

Models a and c of Leo 1 predict SMDs with peaks at lower and higher [Fe/H], respectively, compared to the observations, due mainly to the limiting values chosen for the SF efficiency. The SMDs exhibit also low and high-metallicity tails shifted to higher and lower metallicities with respect to the observed ones. Other than that, the different values adopted for the star formation and galactic wind efficiencies can help to explain small differences between the predictions of the best model and the observed data. In Fig. 2 the predicted SMD seems to be broader than the observed one, and this can be related to the adopted SF and wind efficiencies. By comparing the predictions of the best model with the model Leo1a (lower limits - curve on the left) one can notice that the latter shows a sharper distribution. On the other hand, model Leo1c (with higher values for the main parameters) exhibits a broader distribution compared to the best model. A more complete set of stars with measured abundance ratios could help to adjust these values and provide a better fit to the SMD.

4.2 Leo 2

Understanding the chemical enrichment history of the dwarf spheroidal galaxy Leo 2 (and of Leo 1) contributes to increase the knowledge of the processes which affect the evolution of this class of objects, since this is the second most distant known dwarf that is assumed to be orbiting our Galaxy (Bellazzini et al. 2005). If isolated dSphs exhibit similar chemical properties as the most nearby ones, it could imply that these properties in dSph are results mainly of their stellar and chemical evolution.

Leo 2 is a metal-poor system dominated by intermediate age populations (Dolphin et al. 2005; Bellazzini et al. 2005; Mighell ![]() Rich 1996).

The SF occurred mainly at early epochs (until approximately 9 Gyr

ago), but there are also hints of more recent SF (Dolphin et al. 2005).

Its stellar metallicity distribution is characterized by an apparent

lack of metal-poor stars, similar to other dSphs, with an average

metallicity around [Ca/H]

Rich 1996).

The SF occurred mainly at early epochs (until approximately 9 Gyr

ago), but there are also hints of more recent SF (Dolphin et al. 2005).

Its stellar metallicity distribution is characterized by an apparent

lack of metal-poor stars, similar to other dSphs, with an average

metallicity around [Ca/H] ![]() -1.65 dex (Bosler et al. 2007) and [Fe/H]

-1.65 dex (Bosler et al. 2007) and [Fe/H] ![]() -1.74 dex (Koch et al. 2007a).

The spread in metallicity also differs when different elements are

adopted as metallicity tracers: for [Ca/H] the metallicity ranges from

-2.61

-1.74 dex (Koch et al. 2007a).

The spread in metallicity also differs when different elements are

adopted as metallicity tracers: for [Ca/H] the metallicity ranges from

-2.61 ![]() [Ca/H]

[Ca/H] ![]() -0.59 dex (Bosler et al. 2007), whereas it ranges from -2.4

to -1.08 dex when [Fe/H] is considered (Koch et al. 2007a).

In both cases, however, the general shape exhibits an asymmetric

distribution, with a rapid and sharp falloff at the metal-rich tail,

which is normally attributed to the sudden suppression of the SF and

the loss of gas.

-0.59 dex (Bosler et al. 2007), whereas it ranges from -2.4

to -1.08 dex when [Fe/H] is considered (Koch et al. 2007a).

In both cases, however, the general shape exhibits an asymmetric

distribution, with a rapid and sharp falloff at the metal-rich tail,

which is normally attributed to the sudden suppression of the SF and

the loss of gas.

More recently, Shetrone et al. (2009) used previously published spectra to derive abundance ratios of Mg and Ca for almost 30 stars in Leo 2. Their results show a trend of a gradual decline of [Mg/Fe] and [Ca/Fe] with increasing metallicity in more metal-rich stars, similar to what is observed in nearby dSphs. Consequently, these authors suggested that this trend supports the hypothesis that the slow chemical enrichment of dSph does not depend on any interaction with the Milky Way galaxy, since this galaxy is located at a large galactocentric distance. A further analysis taking into account the flows of gas with a detailed chemical evolution model can help to shed light on this subject.

4.2.1 Abundance ratios

The predictions for [Mg/Fe] and [Ca/Fe] ratios from the Leo 2 models are compared to the observed data in Figs. 4 and 5,

respectively. Contrary to the several chemical species estimated in

only a low number of stars in Leo 1, in Leo 2 the abundances

were inferred for a considerable number of stars (almost 30), but only

for a few elements. Mg and Ca are enough, though, to represent the

pattern on [![]() /Fe],

even though some differences exist in their production. Mg is almost

totally produced in SNe II (similar to O), whereas a fraction of

Ca is also produced in SNe Ia (similar to Si). In fact, this difference

is helpful to impose constraints in the chemical history of the galaxy

and in the parameters of the models.

/Fe],

even though some differences exist in their production. Mg is almost

totally produced in SNe II (similar to O), whereas a fraction of

Ca is also produced in SNe Ia (similar to Si). In fact, this difference

is helpful to impose constraints in the chemical history of the galaxy

and in the parameters of the models.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{13045f04}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/04/aa13045-09/Timg41.png)

|

Figure 4: [Mg/Fe] vs. [Fe/H] observed in the dSph galaxy Leo 2 compared to the predictions of the best model (solid line). The dashed lines represent the upper and lower limits of the predictions. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{13045f05}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/04/aa13045-09/Timg42.png)

|

Figure 5: [Ca/Fe] vs. [Fe/H] observed in the dSph galaxy Leo 2 compared to the predictions of the best model (solid line). The dashed lines represent the upper and lower limits of the predictions. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{13045f06}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/04/aa13045-09/Timg43.png)

|

Figure 6: The stellar metallicity distribution as a function of [Fe/H] observed in the dSph galaxy Leo 2 (long dashed line) compared to the predictions of the best model (solid line). The short dashed lines represent thhe upper and lower limits of the predictions. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{13045f07}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/04/aa13045-09/Timg46.png)

|

Figure 7: The stellar metallicity distribution as a function of [Ca/H] observed in the dSph galaxy Leo 2 (dashed line) compared to the predictions of the best model (long solid line). The short dashed lines represent the upper and lower limits of the predictions. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

4.2.2 The stellar metallicity distribution

The comparisons between the SMDs and the predictions of the models are shown in Figs. 6 and 7

(as a function of [Fe/H] and [Ca/H], respectively). Similar to

Leo 1, the SMD helps to define a best model with specific values

for the efficiencies of the SF and galactic winds (![]() Gyr-1 and wi = 8 - Leo2b). For Leo 2, however, models a and c

predict SMDs very different from the observed one. This difference

could originate in the large dispersion observed in the abundance

ratios (the constraint for the upper and lower models).

In both cases the general agreement between the best model (Leo2b -

solid thick line) and the observations is very good, with minor

differences between the comparisons for each element (as in the case of

Leo 1). At the poor-metal tail of the distributions, the number of

stars predicted by the best model fits the observations very well when

Fe is used as a metallicity tracer, whereas there seems to be a small

underproduction of stars when [Ca/H] is adopted. This difference is

negligible though and could be a consequence of the metallicity

calibration adopted in the different works. Similar to the case of

Leo 1, the low number of metal-poor stars in the models and

observations can be attributed to the very low SFR and the timescale of

the infall, without the need to invoke an infall of pre-enriched gas.

Gyr-1 and wi = 8 - Leo2b). For Leo 2, however, models a and c

predict SMDs very different from the observed one. This difference

could originate in the large dispersion observed in the abundance

ratios (the constraint for the upper and lower models).

In both cases the general agreement between the best model (Leo2b -

solid thick line) and the observations is very good, with minor

differences between the comparisons for each element (as in the case of

Leo 1). At the poor-metal tail of the distributions, the number of

stars predicted by the best model fits the observations very well when

Fe is used as a metallicity tracer, whereas there seems to be a small

underproduction of stars when [Ca/H] is adopted. This difference is

negligible though and could be a consequence of the metallicity

calibration adopted in the different works. Similar to the case of

Leo 1, the low number of metal-poor stars in the models and

observations can be attributed to the very low SFR and the timescale of

the infall, without the need to invoke an infall of pre-enriched gas.

In both cases ([Fe/H] and [Ca/H]) the observed and predicted

metallicity peaks of the main stellar population lie between [Fe/H] (or

[Ca/H]) ![]() -1.7-1.5 dex. As mentioned in the case of Leo 1, the

metallicity of the peak of the distribution is determined by the low SF

efficiency (

-1.7-1.5 dex. As mentioned in the case of Leo 1, the

metallicity of the peak of the distribution is determined by the low SF

efficiency (![]() Gyr-1) and the high galactic wind efficiency (wi = 8).

Gyr-1) and the high galactic wind efficiency (wi = 8).

The effects of the wind on the SF can also be noticed in the metal-rich

tail of the distribution. In the observed SMDs as a function of [Fe/H]

and [Ca/H] a steep decline can be seen after the peak, due to the

decrease in the number of stars formed. This decrease is normally

attributed to the loss of the gas content that fuels the SF. In our

scenario the gas is lost through intense galactic winds, triggered by

SNe explosions. The predictions of the models fit the observations

nicely with a small overprediction on the number of stars by the best

model (Leo2b - solid line). This discrepancy is mainly related to the

efficiency of the galactic wind adopted in the best model. A higher

value would decrease the SFR even more, decreasing also the number of

stars with high [Fe/H].

Apart from that, one can see distinct differences in the metal-rich

tails of each distribution: for the [Ca/H] distribution the decline is

sharp and fits the observations very well (with the exception of one

star with [Ca/H] ![]() -0.5 dex); the metal-rich tail of the [Fe/H] distribution seems to

predict a small overabundance of stars. The slightly high number of

stars with a high [Fe/H] content can be explained by taking into

account the main site of the production of this element and the long

timescale for its injection in the ISM, the reason for which can be

found in the different nucleosynthesis sites of Fe and Ca, as already

discussed for Leo I.

In the observed data, as also explained before, the differences could

be partly the result of the methods adopted in different works to

derive the abundances of Ca and Fe and to the fact that in the [Ca/H]

distribution only the data of Bosler et al. (2007)

are used, at variance with the SMD as a function of [Fe/H], which is

constructed with all data together. Therefore it is not recommended to

compare the two observed distributions, since it could confuse the

interpretation. We decided to compared them both with observations to

have a more complete picture of the chemical evolution of Leo 2,

but kept in mind that the two should not be regard as the same.

-0.5 dex); the metal-rich tail of the [Fe/H] distribution seems to

predict a small overabundance of stars. The slightly high number of

stars with a high [Fe/H] content can be explained by taking into

account the main site of the production of this element and the long

timescale for its injection in the ISM, the reason for which can be

found in the different nucleosynthesis sites of Fe and Ca, as already

discussed for Leo I.

In the observed data, as also explained before, the differences could

be partly the result of the methods adopted in different works to

derive the abundances of Ca and Fe and to the fact that in the [Ca/H]

distribution only the data of Bosler et al. (2007)

are used, at variance with the SMD as a function of [Fe/H], which is

constructed with all data together. Therefore it is not recommended to

compare the two observed distributions, since it could confuse the

interpretation. We decided to compared them both with observations to

have a more complete picture of the chemical evolution of Leo 2,

but kept in mind that the two should not be regard as the same.

5 Discussion and conclusions

We investigated the chemical evolutionary history of the dSph

galaxies Leo 1 and Leo 2 by means of predictions from

detailed chemical evolution models compared to observations. The

stellar metallicity distributions of these galaxies and several

abundance ratios were used as constraints to define the values for the

main parameters of the models, like SF and galactic wind efficiencies.

The SFHs were taken from results of color-magnitude diagrams, which

indicate extended SF episodes which occur at early epochs, but also

with the presence of intermediate stellar populations. Leo 1 is

characterized by an intense episode occurring from 14 to 9 Gyr ago

and a subsequent less intense SF, which lasts until approximately

3 Gyr ago, whereas Leo 2 formed stars also at early epochs

but stopped ![]() 6-7 Gyr ago.

6-7 Gyr ago.

Table 2: Models without galactic winds for the dSph galaxies Leo 1 and Leo 2.

In our scenario, these galaxies formed from an initial collapse of pristine gas until a mass of ![]()

![]() was reached. A SF with a very low efficiency (

was reached. A SF with a very low efficiency (![]() Gyr-1 and

Gyr-1 and ![]() = 0.3 Gyr-1

for Leo 1 and Leo 2 best models, respectively) takes place,

and the galaxies start evolving slowly. The slow SF and the infall

timescale give rise to a low number of metal-poor stars in agreement

with the observations. Stars are forming slowly in time, but the

overall metallicity increases relatively fast with the most massive

stars exploding and injecting metal into the ISM on a very short

timescale (few Myr for a

= 0.3 Gyr-1

for Leo 1 and Leo 2 best models, respectively) takes place,

and the galaxies start evolving slowly. The slow SF and the infall

timescale give rise to a low number of metal-poor stars in agreement

with the observations. Stars are forming slowly in time, but the

overall metallicity increases relatively fast with the most massive

stars exploding and injecting metal into the ISM on a very short

timescale (few Myr for a

![]() ). After

). After

![]() (10

(10

![]() )

the first generation of stars, the ISM is enriched enough that the

newborn stars contain already a considerable amount of metals. The SF

proceeds for several Myr to a few Gyr when the majority of stars

are formed. During this early epoch the [

)

the first generation of stars, the ISM is enriched enough that the

newborn stars contain already a considerable amount of metals. The SF

proceeds for several Myr to a few Gyr when the majority of stars

are formed. During this early epoch the [![]() /Fe]

ratios are characterized by values above solar, which decrease smoothly

as a function of metallicity due to the slow enrichment of Fe by the

first SNe Ia. As SNe continue to explode, energy is being released, and