| Issue |

A&A

Volume 505, Number 2, October II 2009

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Page(s) | 463 - 482 | |

| Section | Cosmology (including clusters of galaxies) | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/200912314 | |

| Published online | 03 August 2009 | |

The zCOSMOS survey. The dependence of clustering on luminosity and stellar mass at z=0.2-1![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

B. Meneux1,2 - L. Guzzo3 - S. de la Torre3,4,5 - C. Porciani6,7 - G. Zamorani8 - U. Abbas9 - M. Bolzonella8 - B. Garilli5 - A. Iovino10 - L. Pozzetti8 - E. Zucca8 - S. J. Lilly7 - O. Le Fèvre4 - J.-P. Kneib4 - C. M. Carollo7 - T. Contini11 - V. Mainieri12 - A. Renzini13 - M. Scodeggio5 - S. Bardelli8 - A. Bongiorno1 - K. Caputi7 - G. Coppa8,14 - O. Cucciati4 - L. de Ravel4 - P. Franzetti5 - P. Kampczyk7 - C. Knobel7 - K. Kovac7 - F. Lamareille11 - J.-F. Le Borgne11 - V. Le Brun4 - C. Maier7 - R. Pellò11 - Y. Peng7 - E. Perez Montero11 - E. Ricciardelli13 - J. D. Silverman7 - M. Tanaka12 - L. Tasca4,5 - L. Tresse4 - D. Vergani8 - D. Bottini5 - A. Cappi8 - A. Cimatti14 - P. Cassata4 - M. Fumana5 - A. M. Koekemoer15 - A. Leauthaud16 - D. Maccagni5 - C. Marinoni17 - H. J. McCracken18 - P. Memeo5 - P. Oesch7 - R. Scaramella19

1 -

Max-Planck-Institut für Extraterrestrische Physik, Giessenbachstrasse, 85748 Garching-bei-München,

Germany

2 - Universitäts-Sternwarte, Scheinerstrasse 1, Munich 81679,

Germany

3 - INAF - Osservatorio Astronomico di Brera, Via

Bianchi 46, 23807 Merate (LC), Italy

4 - Laboratoire

d'Astrophysique de Marseille, UMR 6110 CNRS Université de

Provence, BP8, 13376 Marseille Cedex 12, France

5 - INAF -

Istituto di Astrofisica Spaziale e Fisica Cosmica, Via Bassini 15,

20133 Milano, Italy

6 - Argelander Institute for Astronomy, Auf

dem Hügel 71, 53121 Bonn, Germany

7 - Institute of Astronomy, ETH

Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

8 - INAF - Osservatorio Astronomico

di Bologna, Bologna, Italy

9 - INAF - Osservatorio Astronomico

di Torino, Strada Osservatorio 20, 10025 Pino Torinese (TO), Italy

10 - INAF - Osservatorio Astronomico di Brera, via Brera 28,

Milano, Italy

11 - Laboratoire d'Astrophysique de

Toulouse-Tarbes, Université de Toulouse, CNRS Toulouse, 31400,

France

12 - European Southern Observatory, Garching,

Germany

13 - Dipartimento di Astronomia, Università di

Padova, Padova, Italy

14 - Dipartimento di Astronomia,

Università degli Studi di Bologna, Bologna, Italy

15 - Space

Telescope Science Institute, 3700 San Martin Drive, Baltimore, MD

21218, USA

16 - Berkeley Lab & Berkeley Center for Cosmological

Physics, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA

17 -

Centre de Physique Theorique, UMR 6207 CNRS Université de

Provence, 13288 Marseille, France

18 - Institut d'Astrophysique

de Paris, Université Pierre & Marie Curie, Paris, France

19 -

INAF - Osservatorio Astronomico di Roma, via di Frascatti 33,

00040 Monte Porzio Catone, Italy

Received 9 April 2009 / Accepted 15 June 2009

Abstract

Aims. We study the dependence of galaxy clustering on luminosity and stellar mass at redshifts ![]() [0.2-1], using the first 10K redshifts from the zCOSMOS spectroscopic survey of the COSMOS field.

[0.2-1], using the first 10K redshifts from the zCOSMOS spectroscopic survey of the COSMOS field.

Methods. We measured the redshift-space correlation functions

![]() and

and ![]() and the projected function,

and the projected function,

![]() for subsamples covering different luminosity, mass, and redshift ranges. We explored and quantified in detail the observational selection biases from the flux-limited nature of the survey, using ensembles of realistic semi-analytic mock samples built from the Millennium simulation. We used the same mock data sets to carefully check our covariance and error estimate techniques, comparing the performances of methods based on the scatter in the mocks and on bootstrapping schemes. We finally compared our measurements to the cosmological model predictions from the mock surveys.

for subsamples covering different luminosity, mass, and redshift ranges. We explored and quantified in detail the observational selection biases from the flux-limited nature of the survey, using ensembles of realistic semi-analytic mock samples built from the Millennium simulation. We used the same mock data sets to carefully check our covariance and error estimate techniques, comparing the performances of methods based on the scatter in the mocks and on bootstrapping schemes. We finally compared our measurements to the cosmological model predictions from the mock surveys.

Results. At odds with other measurements at similar redshift and in the local Universe, we find a weak dependence of galaxy clustering on luminosity in all three redshift bins explored. A mild dependence on stellar mass is instead observed, in particular on small scales, which becomes particularly evident in the central redshift bin (0.5<z<0.8), where

![]() shows strong excess power on scales >1 h-1 Mpc. This is reflected in the shape of the full

shows strong excess power on scales >1 h-1 Mpc. This is reflected in the shape of the full

![]() that we interpret as produced by dominating structures almost perpendicular to the line of sight in the survey volume. Comparing to

that we interpret as produced by dominating structures almost perpendicular to the line of sight in the survey volume. Comparing to ![]() measurements, we do not see any significant evolution with redshift of the amplitude of clustering for bright and/or massive galaxies.

measurements, we do not see any significant evolution with redshift of the amplitude of clustering for bright and/or massive galaxies.

Conclusions. This is consistent with previous results and the standard picture in which the bias evolves more rapidly for the most massive haloes, which in turn host the highest-stellar-mass galaxies. At the same time, however, the clustering measured in the zCOSMOS 10K data at 0.5<z<1 for galaxies with

![]() is only marginally consistent with the predictions from the mock surveys. On scales larger than

is only marginally consistent with the predictions from the mock surveys. On scales larger than ![]() 2 h-1 Mpc, the observed clustering amplitude is compatible only with

2 h-1 Mpc, the observed clustering amplitude is compatible only with ![]() 1% of the mocks. Thus, if the power spectrum of matter is

1% of the mocks. Thus, if the power spectrum of matter is ![]() CDM with standard normalisation and the bias has no ``unnatural'' scale-dependence, this result indicates that COSMOS has picked up a particularly rare,

CDM with standard normalisation and the bias has no ``unnatural'' scale-dependence, this result indicates that COSMOS has picked up a particularly rare, ![]() 2-3

2-3![]() positive fluctuation in a volume of

positive fluctuation in a volume of ![]() 106 h-1 Mpc3. These findings underline the need for larger surveys of the

106 h-1 Mpc3. These findings underline the need for larger surveys of the ![]() Universe to appropriately characterise the level of structure at this epoch.

Universe to appropriately characterise the level of structure at this epoch.

Key words: cosmology: observations - large-scale structure of Universe - surveys - Galaxy: evolution

1 Introduction

In the canonical scenario of galaxy formation, galaxies are thought to form through the cooling of baryonic gas within extended dark matter haloes (White & Rees 1978). The mass of the hosting halo is expected to play a significant role in the definition of the visible properties of the galaxy, as the total mass in gas and stars, its luminosity, colour, star formation rate, and possibly, morphology.Since it is the baryons that form the visible fabric of the Universe, a major challenge in testing the galaxy formation paradigm is to build clear connections between these observed properties and those of the hosting dark-matter haloes. This is a difficult task, as any direct connection initially existing between the dark-matter mass and the baryonic component cooling within the halo is modified by all subsequent dynamical processes affecting the halo-galaxy system, such as merging or dynamical friction. This is confirmed by simulations, which also show however that galaxy luminosity and stellar mass do in fact retain memory of the ``original'' (not actual) halo mass, i.e. before it experiences a major merger or is accreted by a larger halo (Conroy et al. 2006; Wang et al. 2006,2007). This gives some hope that by measuring the dependence of the galaxy distribution on galaxy properties one is actually constraining the relationship between the dark and luminous components of galaxies.

Measurements of first

moments, such as the luminosity function (LF) or the stellar mass

function, provide a way to understand how these are related to the

total halo mass functions, which can be obtained from analytic

predictions (e.g. Press & Schechter 1974) or n-body

simulations (e.g. Warren et al. 2006). Similar investigations

can be made on the second moment, i.e. the two-point correlation

function (e.g. Springel et al. 2006). Studies of galaxy

clustering in large local surveys have shown how clustering at

![]() does depend significantly on several specific properties.

These include luminosity

(Hamilton 1988; Maurogordato & Lachieze-Rey 1991; Iovino et al. 1993; Benoist et al. 1996; Guzzo et al. 2000; Norberg et al. 2001; Norberg et al. 2002; Zehavi et al. 2005),

colour or spectral type

(Willmer et al. 1998; Norberg et al. 2002; Zehavi et al. 2002), morphology

(Davis & Geller 1976; Giovanelli et al. 1986; Guzzo et al. 1997), stellar

mass (Li et al. 2006), and environment

(Abbas & Sheth 2006).

does depend significantly on several specific properties.

These include luminosity

(Hamilton 1988; Maurogordato & Lachieze-Rey 1991; Iovino et al. 1993; Benoist et al. 1996; Guzzo et al. 2000; Norberg et al. 2001; Norberg et al. 2002; Zehavi et al. 2005),

colour or spectral type

(Willmer et al. 1998; Norberg et al. 2002; Zehavi et al. 2002), morphology

(Davis & Geller 1976; Giovanelli et al. 1986; Guzzo et al. 1997), stellar

mass (Li et al. 2006), and environment

(Abbas & Sheth 2006).

In recent years it has become possible to extend these

investigations to high redshift, obtaining first indicative

results on how these dependences evolve with time

(Meneux et al. 2006,2008; Pollo et al. 2006; Daddi et al. 2003; Coil et al. 2006; Phleps et al. 2006).

The VIMOS-VLT Deep Survey (VVDS) (Pollo et al. 2006) and the

DEEP2 survey (Coil et al. 2006) in particular, have provided new

insights into the way galaxies of different luminosity cluster at

![]() .

More specifically, Pollo et al. (2006) have shown that

at these epochs galaxies already show a luminosity segregation,

with more luminous galaxies being more clustered than faint

objects. At the same time, however, a significant steepening with

luminosity of the shape of their two-point correlation function

for separations <1-2 h-1 Mpc, is observed. This behaviour

is at variance with that at

.

More specifically, Pollo et al. (2006) have shown that

at these epochs galaxies already show a luminosity segregation,

with more luminous galaxies being more clustered than faint

objects. At the same time, however, a significant steepening with

luminosity of the shape of their two-point correlation function

for separations <1-2 h-1 Mpc, is observed. This behaviour

is at variance with that at ![]() .

A similar trend has been

observed at the same redshift by the DEEP2 survey

(Coil et al. 2006). In addition, Meneux et al. (2008) have shown a

positive trend of clustering with stellar mass also at

.

A similar trend has been

observed at the same redshift by the DEEP2 survey

(Coil et al. 2006). In addition, Meneux et al. (2008) have shown a

positive trend of clustering with stellar mass also at ![]() ,

with clear evidence of a stronger evolution of the bias factor for

the most massive galaxies (see also Brown et al. 2008; Wake et al. 2008).

,

with clear evidence of a stronger evolution of the bias factor for

the most massive galaxies (see also Brown et al. 2008; Wake et al. 2008).

Interpreting the evolution in shape and amplitude of

![]() with

respect to luminosity and redshift is particularly interesting in

the context of the halo model for galaxy formation. In this

framework, the observed shape of

with

respect to luminosity and redshift is particularly interesting in

the context of the halo model for galaxy formation. In this

framework, the observed shape of ![]() (or

(or

![]() )

is

interpreted as being composed of the sum of two components: a) the

1-halo term, which dominates on small scales (<1-2 h-1 Mpc

at the current epoch), where correlations are dominated by pairs

of galaxies living within the same dark-matter halo (i.e. in a

group or cluster); b) the 2-halo term on large scales, which is

characterised by pairs of galaxies occupying different dark-matter

haloes (see Cooray & Sheth (2002) for a review).

Zheng et al. (2007) have modelled the luminosity-dependent

)

is

interpreted as being composed of the sum of two components: a) the

1-halo term, which dominates on small scales (<1-2 h-1 Mpc

at the current epoch), where correlations are dominated by pairs

of galaxies living within the same dark-matter halo (i.e. in a

group or cluster); b) the 2-halo term on large scales, which is

characterised by pairs of galaxies occupying different dark-matter

haloes (see Cooray & Sheth (2002) for a review).

Zheng et al. (2007) have modelled the luminosity-dependent

![]() from both the DEEP2 (at

from both the DEEP2 (at ![]() )

and SDSS (at

)

and SDSS (at ![]() )

surveys, within such Halo Occupation Distribution (HOD)

framework. In this way they establish evolutionary connections

between galaxies and dark-matter haloes at these two epochs,

providing a self-consistent scenario in which the growth of the

stellar mass depends on the halo mass. Similar results have been

obtained more recently in a combined analysis of the VVDS-Deep and

SDSS data (Abbas et al. 2009).

)

surveys, within such Halo Occupation Distribution (HOD)

framework. In this way they establish evolutionary connections

between galaxies and dark-matter haloes at these two epochs,

providing a self-consistent scenario in which the growth of the

stellar mass depends on the halo mass. Similar results have been

obtained more recently in a combined analysis of the VVDS-Deep and

SDSS data (Abbas et al. 2009).

1 In this paper we use the first 10 000 redshifts from the zCOSMOS

redshift survey (the ``10K sample'') to further explore these

high-redshift trends of clustering with luminosity and mass based

on a new, independent sample. Although shallower than VVDS-Deep

and DEEP2 (

![]() vs. 24 and 23.5, respectively), zCOSMOS

covers a significantly larger area and samples a volume of

vs. 24 and 23.5, respectively), zCOSMOS

covers a significantly larger area and samples a volume of

![]()

![]() h-1 Mpc to redshift z=1.2. This should

hopefully help reducing the effect of cosmic variance (still

strong for samples this size, Garilli et al. 2008; Stringer et al. 2009),

while providing a better sampling of the high-end tail of the

luminosity and mass functions. However, one main result of this

analysis will be the explicit demonstration of the strength of the

cosmic variance within volumes of this size. The clustering

properties of the zCOSMOS sample in the volume contained within

the redshift range 0.4-1 seem to lie at the extreme high end of

the distribution of fluctuations on these scales, as already

suggested by the angular clustering of the COSMOS data

(McCracken et al. 2007). As we shall see, these results and those

presented in the zCOSMOS series of clustering papers

de la Torre et al. 2009; Porciani et al., in

prep.; Abbas et al., in prep. indicate how cautious

one should be in drawing far-reaching conclusions from the

modelling of current clustering results from deep galaxy surveys.

h-1 Mpc to redshift z=1.2. This should

hopefully help reducing the effect of cosmic variance (still

strong for samples this size, Garilli et al. 2008; Stringer et al. 2009),

while providing a better sampling of the high-end tail of the

luminosity and mass functions. However, one main result of this

analysis will be the explicit demonstration of the strength of the

cosmic variance within volumes of this size. The clustering

properties of the zCOSMOS sample in the volume contained within

the redshift range 0.4-1 seem to lie at the extreme high end of

the distribution of fluctuations on these scales, as already

suggested by the angular clustering of the COSMOS data

(McCracken et al. 2007). As we shall see, these results and those

presented in the zCOSMOS series of clustering papers

de la Torre et al. 2009; Porciani et al., in

prep.; Abbas et al., in prep. indicate how cautious

one should be in drawing far-reaching conclusions from the

modelling of current clustering results from deep galaxy surveys.

A significant part of this paper is dedicated to discussing these cosmic-variance effects in detail, together with the impact of incompleteness on the derived results. This is particularly important when constructing mass-limited subsamples from a magnitude-limited survey, which introduces a mass incompleteness that depends on redshift and stellar mass. The intrinsic scatter in the galaxy mass-luminosity relation determines a progressive loss of faint galaxies with high mass-to-light ratio. We study the effect of this incompleteness on the measured clustering in detail using both the data themselves and mock samples built from the Millennium simulation. At the same time, we explore in quite some detail our ability to characterise measurement errors and the covariance matrix of our data, comparing estimates from the mock samples to those from bootstrap resamplings of the data.

The paper is organised as follows. In Sects. 2 and 3 we describe the zCOSMOS survey and the simulated mock samples used in the analysis, while in Sect. 4 we describe the selection of luminosity- and mass-limited subsamples, discussing extensively the incompleteness related to this operation. In Sect. 5 we describe our clustering estimators, while in Sect. 6 we discuss the observational biases and selection effects in detail, as well as how we account for them and what is their effect on the measured quantities; in Sect. 7 we explore the error budget and how to estimate the covariance properties of our measurements; in Sects. 8 and 9 we present our measurements of clustering as a function of luminosity and mass, respectively; in Sect. 10 we compare these results with those from other surveys and with simple model predictions; finally, in Sect. 11 we place these findings in a broader context and discuss future developments.

Throughout the paper we adopt a cosmology with

![]() ,

,

![]() .

When needed, we also adopt a value

.

When needed, we also adopt a value

![]() for the normalisation of the matter power spectrum;

this is chosen for consistency with the Millennium simulation,

also used for comparison to model predictions. The Hubble constant

is parameterised via h=H0/100 to ease comparison with previous

works. Stellar masses are quoted in unit of h=1. All length

values are quoted in co-moving coordinates.

for the normalisation of the matter power spectrum;

this is chosen for consistency with the Millennium simulation,

also used for comparison to model predictions. The Hubble constant

is parameterised via h=H0/100 to ease comparison with previous

works. Stellar masses are quoted in unit of h=1. All length

values are quoted in co-moving coordinates.

![\begin{figure}\par\includegraphics[width=12cm]{12314f01.ps} \end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/38/aa12314-09/Timg39.png) |

Figure 1:

Distribution on the sky of the |

| Open with DEXTER | |

2 The zCOSMOS survey data

The zCOSMOS survey (Lilly et al. 2007) is being performed with the VIMOS multi-object spectrograph at the ESO Very Large Telescope (Le Fèvre et al. 2003). Six hundred hours of observation have been allocated to this programme. These are being invested to measure spectra for galaxies in the COSMOS field (Scoville et al. 2007a), targeting: a)

Observations were performed using the

medium-resolution RED grism, corresponding to ![]() and

covering the spectral range 5550-9650 Å. The average error on

the redshift measurements was estimated from the repeated

observations of 632 galaxies and found to be

and

covering the spectral range 5550-9650 Å. The average error on

the redshift measurements was estimated from the repeated

observations of 632 galaxies and found to be ![]() 100 km s-1(Lilly et al. 2009). This corresponds roughly to a radial

distance error of 1 h-1 Mpc. The reduction of the data to the

redshift assignment was carried out independently at two

institutes before a reconciliation process to solve discrepancies.

The quality of each measured redshift was then quantified via a

quality flag that provides us with a confidence level

(see Lilly et al. 2009,2007, for definition). For the

present work, we only use redshifts with flags 1.5-4.5 and

9.3-9.5, corresponding to confidence levels greater than 98%.

100 km s-1(Lilly et al. 2009). This corresponds roughly to a radial

distance error of 1 h-1 Mpc. The reduction of the data to the

redshift assignment was carried out independently at two

institutes before a reconciliation process to solve discrepancies.

The quality of each measured redshift was then quantified via a

quality flag that provides us with a confidence level

(see Lilly et al. 2009,2007, for definition). For the

present work, we only use redshifts with flags 1.5-4.5 and

9.3-9.5, corresponding to confidence levels greater than 98%.

The zCOSMOS survey benefits the large multi-wavelength coverage of the COSMOS field (Capak et al. 2007), which with the latest additions now comprises 30 photometric bands (Ilbert et al. 2009) extending well into the infrared. These include, in particular, accurate K-band and Spitzer-IRAC photometry over the whole area, which have allowed us to derive relevant physical properties as rest-frame luminosity and stellar mass with unprecedented accuracy (Pozzetti et al. 2009; Bolzonella et al. 2009; Zucca et al. 2009).

![\begin{figure}\par\includegraphics[width=12cm]{12314f02.ps} \end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/38/aa12314-09/Timg43.png) |

Figure 2: Selection boundaries of the different subsamples of the zCOSMOS 10K survey used in this paper. Left: luminosity-redshift selection, which accounts for the average luminosity evolution of galaxies; Right: mass-redshift selection. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

3 Mock survey catalogues

In this paper we make intense use of mock surveys constructed from the Millennium simulation (Springel et al. 2005). This was done a) to understand the effect of our selection criteria on the measured quantities (Sect. 6.3) and b) to estimate the measurement errors and covariance of the data (Sect. 7).

We used two sets of light cones, constructed as explained in

Kitzbichler & White (2007) and Blaizot et al. (2005) by combining

dark-matter halo trees from the Millennium run to the Munich

semi-analytic model of galaxy formation

(De Lucia & Blaizot 2007). The two sets contain 24

![]() deg2 mocks built by Kitzbichler & White (2007) and

40

deg2 mocks built by Kitzbichler & White (2007) and

40 ![]() deg2 mocks built by De Lucia & Blaizot (2007),

which we name KW24 and DLB40, respectively. The main difference

between the two sets, in addition to the different survey area, is

that the DLB40 set contains all galaxies irrespective of any

criteria down to the simulation limit that corresponds roughly to

deg2 mocks built by De Lucia & Blaizot (2007),

which we name KW24 and DLB40, respectively. The main difference

between the two sets, in addition to the different survey area, is

that the DLB40 set contains all galaxies irrespective of any

criteria down to the simulation limit that corresponds roughly to

![]() ,

up to redshift z=1.7, whereas the KW24 set only

contains galaxies brighter than

,

up to redshift z=1.7, whereas the KW24 set only

contains galaxies brighter than ![]() .

This implies that the

DLB40 set allowed us to select in stellar mass down to very low

masses and to test selection effects. The observing strategy of

the zCOSMOS 10K sample was only applied to the KW24 set, allowing

us to do careful error analysis of our measurements.

.

This implies that the

DLB40 set allowed us to select in stellar mass down to very low

masses and to test selection effects. The observing strategy of

the zCOSMOS 10K sample was only applied to the KW24 set, allowing

us to do careful error analysis of our measurements.

The Millennium run contains N=21603 particles of mass

![]() h-1

h-1 ![]() in a cubic box of size

500 h-1 Mpc. The simulation was built with a

in a cubic box of size

500 h-1 Mpc. The simulation was built with a ![]() CDM

cosmological model with

CDM

cosmological model with

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

,

![]() and H0=73 km s-1 Mpc-1.

and H0=73 km s-1 Mpc-1.

4 Luminosity- and mass-selected subsamples

4.1 Luminosity selection

Absolute magnitudes were derived for the 10K galaxies using the code ALF (Zucca et al. 2009; Ilbert et al. 2005), which is based on fitting a spectral energy distribution (SED) to the observed multi-band photometry. There are various sources of uncertainties to take into account (errors on apparent magnitudes, number of available photometric bands, method used, etc.). A direct comparison with absolute magnitudes derived with the independent code ZEBRA (Feldmann et al. 2006) shows consistent estimates with a small dispersion of-2 For our analysis, the goal is to define luminosity-limited samples that are as close as possible to truly volume-limited samples, i.e. with a constant number density. This might be done within a few independent redshift ranges. The size of the redshift slices in which to split the sample has to be chosen as a compromise between two aspects: a) large enough to have sufficient statistics and provide a good measurement of clustering and b) not too large to avoid significant evolution within each redshift bin.

We know, however, that the luminosity of galaxies evolves through the redshift range covered by the zCOSMOS survey (0.2<z<1.1), with a clear change in the characteristic parameters of the LF (Ilbert et al. 2005). This evolution does depend on the morphological/spectral type of the galaxy considered. To be able to select a nearly volume-limited sample within a given redshift interval, we need to take the corresponding evolution into account. This can only be done realistically in a statistical way by looking at the population-averaged evolution of the global LF.

We therefore considered the observed LF measured from the same

data (Zucca et al. 2009) and modelled its change with redshift

as a pure luminosity evolution (i.e. keeping a constant slope

![]() and normalisation factor

and normalisation factor ![]() ), which is a fair

description of the observed behaviour. We find that the

characteristic absolute magnitude M*(z) evolves with redshift

as

), which is a fair

description of the observed behaviour. We find that the

characteristic absolute magnitude M*(z) evolves with redshift

as

| M*(z) = M*0 + A z, | (1) |

where

We therefore defined our luminosity-limited samples by an

effective absolute magnitude cut at z=0,

![]() ,

including all galaxies with

,

including all galaxies with

![]() .

The resulting selection loci for different values of

.

The resulting selection loci for different values of

![]() are plotted over the data in the

luminosity-redshift plane in the left panel of

Fig. 2. As is evident in the figure, the

faintest allowed threshold

are plotted over the data in the

luminosity-redshift plane in the left panel of

Fig. 2. As is evident in the figure, the

faintest allowed threshold

![]() depends on the

redshift range considered, i.e. z= [0.2-0.5],

z= [0.5-0.8], and z= [0.8-1.0]. The details of the

resulting samples are described in Table 1.

depends on the

redshift range considered, i.e. z= [0.2-0.5],

z= [0.5-0.8], and z= [0.8-1.0]. The details of the

resulting samples are described in Table 1.

Table 1: Properties of the luminosity-selected samples.

Table 2: Properties of the mass-selected samples.

| |

Figure 3: The observed relationship between stellar mass and luminosity for galaxies in the 10K sample, within the three redshift ranges studied in this paper. The left panel shows an aspect of the galaxy bimodality, with red galaxies more massive and brighter than blue ones. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}\par\includegraphics[width=12cm]{12314f04.ps} \end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/38/aa12314-09/Timg60.png) |

Figure 4:

Estimate of how the completeness in stellar mass changes

as a function of redshift, due to the survey flux limit

(

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

4.2 Mass selection

Stellar mass has become a quantity routinely measured in recent

years, thanks to surveys with multi-wavelength photometry,

extending to the near-infrared (e.g. Rettura et al. 2006),

although some uncertainties related to the detailed modelling of

stellar evolution remain (Pozzetti et al. 2007). This has made

studies of clustering as a function of stellar mass possible for

large statistical samples. We used stellar masses estimated by

fitting the SED, as sampled by the large multi-band photometry,

with a library of stellar population models based on

Bruzual & Charlot (2003). We used the code Hyperzmass, a modified

version of the photometric redshift code Hyperz

(Bolzonella et al. 2000). The typical error on stellar masses is

![]() 0.2 dex. The method and accuracy of these measurements are

fully described in Bolzonella et al. (2009) and

Pozzetti et al. (2009).

0.2 dex. The method and accuracy of these measurements are

fully described in Bolzonella et al. (2009) and

Pozzetti et al. (2009).

We have thus constructed a set of mass-selected samples, containing galaxies more massive than a given threshold. We chose the same redshift ranges as used for the luminosity-selected samples. The properties of the selected subsamples are summarised in Table 2 and represented in Fig. 2.

4.3 Mass completeness

The flux-limited nature of surveys like zCOSMOS (

![]() )

mean that the lowest-mass samples are affected to varying degrees

by incompleteness related to the scatter in the mass-luminosity

relation (Fig. 3). This introduces a

bias against objects that would be massive enough to enter the

mass-selected samples, but too faint to fulfil the

apparent-magnitude limit of the survey. These missed high

mass-to-light ratio galaxies will be those dominated by

low-luminosity stars, i.e. the red and faint objects. Clearly, if

this is not accounted for in some way, it would inevitably affect

the estimated clustering properties, with respect to a truly

complete, mass-selected sample (Meneux et al. 2008). It is

therefore necessary to understand the effective completeness level

in detail in the stellar mass of the samples that we defined for

our analysis.

)

mean that the lowest-mass samples are affected to varying degrees

by incompleteness related to the scatter in the mass-luminosity

relation (Fig. 3). This introduces a

bias against objects that would be massive enough to enter the

mass-selected samples, but too faint to fulfil the

apparent-magnitude limit of the survey. These missed high

mass-to-light ratio galaxies will be those dominated by

low-luminosity stars, i.e. the red and faint objects. Clearly, if

this is not accounted for in some way, it would inevitably affect

the estimated clustering properties, with respect to a truly

complete, mass-selected sample (Meneux et al. 2008). It is

therefore necessary to understand the effective completeness level

in detail in the stellar mass of the samples that we defined for

our analysis.

Meneux et al. (2008) have used two different methods to explore and

quantify the completeness limit in stellar mass as a function of

redshift. The first is based on the observed scatter in the

mass-luminosity relation, obtained from the data themselves and

extrapolated to fainter fluxes. The second instead makes use of

mock survey samples, under the hypothesis that they provide a

realistic description of the mass-luminosity relation and its

scatter: the DLB40 set of mock survey catalogues that are complete

in stellar mass are ``observed'' under the same conditions as the

real data, i.e. selected at ![]() .

The completeness is then

simply defined, for a given redshift range and mass threshold, as

the ratio of the number of galaxies brighter than the zCOSMOS flux

limit over those at any flux. Interestingly, even if this method

is model-dependent (in particular, on the prescription of galaxy

formation used in the semi-analytic models), this approach leads

to similar completeness limits to the first one. The results of

this second exercise are shown as a function of redshift and mass

threshold and for a flux limit

.

The completeness is then

simply defined, for a given redshift range and mass threshold, as

the ratio of the number of galaxies brighter than the zCOSMOS flux

limit over those at any flux. Interestingly, even if this method

is model-dependent (in particular, on the prescription of galaxy

formation used in the semi-analytic models), this approach leads

to similar completeness limits to the first one. The results of

this second exercise are shown as a function of redshift and mass

threshold and for a flux limit ![]() ,

in

Fig. 4. Completeness is estimated in

narrow redshift ranges (

,

in

Fig. 4. Completeness is estimated in

narrow redshift ranges (

![]() )

for different mass

thresholds

)

for different mass

thresholds

![]() increasing from 108 to

1011.7

increasing from 108 to

1011.7

![]() with a step of

100.01

with a step of

100.01

![]() .

A large fraction of low-mass objects

are clearly missed at high redshift.

.

A large fraction of low-mass objects

are clearly missed at high redshift.

We also add in Fig. 4 the

completeness limit estimated from the observed scatter in the M/L

relation of the data, and defined at each redshift as the lower

boundary,

![]() ,

including above it 95% of the mass

distribution (Pozzetti et al. 2009). It is very encouraging to

notice the very good agreement between this independent estimation

from the data and that based on the DLB40 set of mock catalogues.

This adds confidence in the use of the simulated samples.

Table 3 summarises the completeness estimates

derived from these mock catalogues for each of the 10 zCOSMOS

galaxy samples defined in Table 2. The sample M2.1

shows the strongest incompleteness: 65.1% of the galaxies more

massive than 109

,

including above it 95% of the mass

distribution (Pozzetti et al. 2009). It is very encouraging to

notice the very good agreement between this independent estimation

from the data and that based on the DLB40 set of mock catalogues.

This adds confidence in the use of the simulated samples.

Table 3 summarises the completeness estimates

derived from these mock catalogues for each of the 10 zCOSMOS

galaxy samples defined in Table 2. The sample M2.1

shows the strongest incompleteness: 65.1% of the galaxies more

massive than 109

![]() are fainter than I=22.5at z= [0.5-0.8] and then, not included in our sample.

In Sect. 6.3 we discuss the effects of

this incompleteness on the galaxy clustering

measurement.

are fainter than I=22.5at z= [0.5-0.8] and then, not included in our sample.

In Sect. 6.3 we discuss the effects of

this incompleteness on the galaxy clustering

measurement.

Table 3: The completeness in stellar mass of mass-selected mock subsamples reproducing the properties and selection criteria of our 10K data samples.

5 Estimating the two-point correlation function

The two-point correlation function is the

simplest estimator for quantifying galaxy clustering, because it

is related to the second moment of the galaxy distribution, i.e.

its variance. In practice, it describes the excess probability

![]() of observing a pair of galaxies at a given separation

r, with respect to that of a random distribution

(Peebles 1980). Here we estimate the redshift-space

correlation function

of observing a pair of galaxies at a given separation

r, with respect to that of a random distribution

(Peebles 1980). Here we estimate the redshift-space

correlation function

![]() ,

which allows one to incorporates the

effect of peculiar motions on the pure Hubble recession velocity.

In this case, galaxy separations are split into the tangential and

radial components,

,

which allows one to incorporates the

effect of peculiar motions on the pure Hubble recession velocity.

In this case, galaxy separations are split into the tangential and

radial components, ![]() and

and ![]() (Fisher et al. 1994; Davis & Peebles 1983).

(Fisher et al. 1994; Davis & Peebles 1983).

The real-space correlation function ![]() can be recovered by

projecting

can be recovered by

projecting

![]() along the line of sight, as

along the line of sight, as

For a power-law correlation function,

![]() ,

this integral can be solved

analytically and fitted to the observed

,

this integral can be solved

analytically and fitted to the observed

![]() to find the

best-fitting values of the correlation length

r0 and slope

to find the

best-fitting values of the correlation length

r0 and slope ![]() (e.g. Davis & Peebles 1983). In computing

(e.g. Davis & Peebles 1983). In computing

![]() ,

a finite upper integration limit has to be chosen in

practice. Its value has to be high enough as to include most of

the clustering signal dispersed along the line of sight by

peculiar motion. However, it must not be too high to avoid adding

only noise, which is dominant above a certain

,

a finite upper integration limit has to be chosen in

practice. Its value has to be high enough as to include most of

the clustering signal dispersed along the line of sight by

peculiar motion. However, it must not be too high to avoid adding

only noise, which is dominant above a certain ![]() .

Previous

works (Pollo et al. 2005) have shown that, for similar data, the

best results are obtained with an integration limit

.

Previous

works (Pollo et al. 2005) have shown that, for similar data, the

best results are obtained with an integration limit

![]() between 20 and 40 h-1 Mpc. Our tests show

that the scatter in the recovered

between 20 and 40 h-1 Mpc. Our tests show

that the scatter in the recovered

![]() is obtained using the

lowest value in this range. This can introduce a 5-10%

underestimate in the recovered large-scale amplitude, which can be

accounted for when fitting a model to

is obtained using the

lowest value in this range. This can introduce a 5-10%

underestimate in the recovered large-scale amplitude, which can be

accounted for when fitting a model to

![]() .

In the following, we

in general use

.

In the following, we

in general use

![]() h-1 Mpc and show examples

of how the amplitude is biased by this choice for the real data.

h-1 Mpc and show examples

of how the amplitude is biased by this choice for the real data.

To estimate

![]() from each galaxy sample, we used

the standard estimator of Landy & Szalay (1993):

from each galaxy sample, we used

the standard estimator of Landy & Szalay (1993):

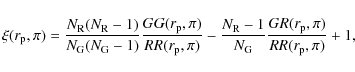

where

6 Observational biases and selection effects

6.1 Correction of VIMOS angular footprint and varying sampling

To properly estimate the correlation function from the 10K zCOSMOS data, we need to correct for its spatial sampling rate, which is on average

![\begin{figure}\par\includegraphics[width=12cm]{12314f05.ps} \end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/38/aa12314-09/Timg77.png) |

Figure 5:

Overall radial distribution of the zCOSMOS 10K sample,

compared to three different smoothed distributions. These are

obtained by filtering the observed data with a Gaussian kernel of

increasing |

| Open with DEXTER | |

We tested three different algorithms to correct for the angular selection function of the survey and obtained comparable results. Other weighting schemes use in particular the angular correlation functions of the 10K sample and the photometric catalogue to correct for the nonuniform spatial sampling rate. These methods are discussed in the parallel clustering analyses by de la Torre et al. (2009) and Porciani et al. (in preparation). In the latter paper in particular, comparative tests of the three algorithms are presented.

Since the subsamples analysed in this work are essentially volume-limited (above the luminosity/mass completeness limits), we did not need to apply any further minimum-variance weighting scheme (as e.g. the J3 weighting, Fisher et al. 1994). This is normally necessary for purely flux-limited surveys in which the selection function varies significantly as a function of redshift, such that different parts of the volume are sampled by galaxies with different luminosities and number densities (e.g. Li et al. 2006).

6.2 Construction of reference random samples

A significant source of uncertainty that we encountered in estimating two-point functions from our 10K subsamples is related to the construction of the random sample and in particular to its redshift distribution. We soon realised that the strongly clustered nature of the COSMOS field along the line of sight, with several dominating structures at different redshifts, required some particular care so as not to generate systematic biases in the random sample. These superclusters are already evident as vertical stripes in Fig. 2 and even more clearly so in the redshift histogram of Fig. 5. We point out the big ``walls'' at z=0.35, 0.75, and 0.9, which are also clearly identified by the density field reconstruction of Kovac et al. (2009).

![\begin{figure}\par\includegraphics[width=12cm]{12314f06.ps} \end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/38/aa12314-09/Timg78.png) |

Figure 6:

The radial distribution of the luminosity-selected sample

L2.1 compared to a smoothed curved (with a kernel of

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}\par\includegraphics[width=12cm]{12314f07.ps} \end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/38/aa12314-09/Timg79.png) |

Figure 7:

The effect of stellar mass incompleteness

on the measured

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}\par\includegraphics[width=12cm]{12314f08.ps} \end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/38/aa12314-09/Timg80.png) |

Figure 8:

Ratio of the diagonal errors on

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

A standard way to generate a random redshift coordinate accounting

for the radial selection function of the data uses a

Gaussian-filtered version of the data themselves. This is normally

obtained using smoothing kernels with a dispersion ![]() (in

co-moving coordinates) in the range 150-250 h-1 Mpc. The

results of applying this technique to the current 10K data are

shown in Fig. 5. One notes how for smoothing

scales of 150 and 250 h-1 Mpc, the curves still retain memory

of the two largest galaxy fluctuations. These are only erased

when a very strong smoothing filter (450 h-1 Mpc) is adopted.

However, in this case the smoothed curve is unable to correctly

follow the global shape of the distribution, overestimating the

number density in the lowest and highest redshift ranges. The

situation for our specific analysis, however, is somewhat simpler

than this general case. Our luminosity-limited or mass-limited

samples are in principle ``volume-limited'', i.e. samples that -

if properly selected - should have a constant density within the

specific redshift bin. One such case is shown in the zoom of

Fig. 6, where the redshift

distribution in the range

z=[0.5,0.8] is plotted.

(in

co-moving coordinates) in the range 150-250 h-1 Mpc. The

results of applying this technique to the current 10K data are

shown in Fig. 5. One notes how for smoothing

scales of 150 and 250 h-1 Mpc, the curves still retain memory

of the two largest galaxy fluctuations. These are only erased

when a very strong smoothing filter (450 h-1 Mpc) is adopted.

However, in this case the smoothed curve is unable to correctly

follow the global shape of the distribution, overestimating the

number density in the lowest and highest redshift ranges. The

situation for our specific analysis, however, is somewhat simpler

than this general case. Our luminosity-limited or mass-limited

samples are in principle ``volume-limited'', i.e. samples that -

if properly selected - should have a constant density within the

specific redshift bin. One such case is shown in the zoom of

Fig. 6, where the redshift

distribution in the range

z=[0.5,0.8] is plotted.

An alternative way to generate the radial distribution of the random sample is to integrate the galaxy LF in steps along the redshift direction, computing at each step a value for the density of galaxies expected at that redshifts. Ideally, the LF can be measured from the sample itself and would include any detected evolution of its parameters. This is what we did here, using the evolving LF parameters presented in the companion dedicated paper (Zucca et al. 2009). The dashed red line in Fig. 6 shows the result one obtains if smoothing with a kernel of 450 h-1 Mpc, compared to the one obtained from the integration of the LF. The latter is fully consistent with what is expected from a truly volume-limited sample with the given selection criteria, with the number of objects increasing as the square of the radial co-moving distance.

6.3 Effect of mass incompleteness on

As discussed in

Sect. 4.3 when we constructed our

mass-limited samples, a fraction of the galaxies more massive than

the formal mass threshold are in fact lost because of the limiting

The ratio of these two estimates (``true'' over

``observed'') averaged over the 40 mock catalogues is

shown in Fig. 7. For a mass

selection that is 100% complete within the given redshift bin, we

would measure

![]() at all separations. We can see

that the only mass range for which this is strictly happening at

any redshift is the one with

at all separations. We can see

that the only mass range for which this is strictly happening at

any redshift is the one with

![]() .

For lower

mass samples, we see a clear reduction of the clustering

amplitude. However, we can also see that, for most samples, the

shape of

.

For lower

mass samples, we see a clear reduction of the clustering

amplitude. However, we can also see that, for most samples, the

shape of

![]() is distorted mainly only below <1 h-1 Mpc.

Above this scale, the mass incompleteness introduces an amplitude

reduction up to

is distorted mainly only below <1 h-1 Mpc.

Above this scale, the mass incompleteness introduces an amplitude

reduction up to ![]() 20% in the worst cases. This will have to

be considered when comparing our measurements with models

(although keeping in mind that these estimates come from simulated

data, not from real observations). For general comparisons,

however, the amount of amplitude reduction of

20% in the worst cases. This will have to

be considered when comparing our measurements with models

(although keeping in mind that these estimates come from simulated

data, not from real observations). For general comparisons,

however, the amount of amplitude reduction of

![]() is typically

negligible on scales larger than

is typically

negligible on scales larger than ![]() 1 h-1 Mpc, given the

statistical errors of the data measurements.

1 h-1 Mpc, given the

statistical errors of the data measurements.

7 Systematic and statistical errors on correlation estimates

The derivation of realistic errors on the galaxy correlation

function has been the subject of debate since its early

measurements (see e.g. Bernstein 1994). In particular, it

is well known that the measured values of the two-point

correlation function are not independent on different scales. This

means that, the bins of

![]() have a degree of correlation among

them, which needs to be taken into account when fitting a model to

the observed values. This can be done if we are able to

reconstruct the

have a degree of correlation among

them, which needs to be taken into account when fitting a model to

the observed values. This can be done if we are able to

reconstruct the ![]() covariance (or correlation) matrix of

the N bins (Fisher et al. 1994).

covariance (or correlation) matrix of

the N bins (Fisher et al. 1994).

In a recent paper,

Norberg et al. (2009) compare in detail three different methods for

estimating the covariance matrix of a given set of measurements.

These use a) the ensemble variance from a set of mock catalogues,

reproducing as accurately as possible the clustering properties

and selection function of the real data; b) a set of bootstrap resamplings of the volume containing the data; and c) a

so-called jack-knife subset of volumes of the survey. In

this latest case, the survey volume is divided into ![]() subvolumes and the statistics under study recomputed each time

excluding one of the subparts. In the ``block-wise'' incarnation

of the bootstrap technique (Porciani & Giavalisco 2002, method

``b''), instead, N subvolumes are selected each

time with repetition, i.e. excluding some of them, but

counting two or more times some others as to always get a global

sample with the same total volume. We note, however, that there

are historically two possible ways of resampling internally the

data set. The classical ``old'' bootstrap (Ling et al. 1986)

entailed boot-strapping the sample ``galaxy-by-galaxy''. This

means each time randomly picking a sample of

subvolumes and the statistics under study recomputed each time

excluding one of the subparts. In the ``block-wise'' incarnation

of the bootstrap technique (Porciani & Giavalisco 2002, method

``b''), instead, N subvolumes are selected each

time with repetition, i.e. excluding some of them, but

counting two or more times some others as to always get a global

sample with the same total volume. We note, however, that there

are historically two possible ways of resampling internally the

data set. The classical ``old'' bootstrap (Ling et al. 1986)

entailed boot-strapping the sample ``galaxy-by-galaxy''. This

means each time randomly picking a sample of ![]() galaxies among

our data set of

galaxies among

our data set of ![]() galaxies, allowing repetitions. In this way,

within one bootstrap realisation a galaxy can be selected more

than once, while some others are never selected. This technique

has been shown to generally lead to some underestimation of the

diagonal errors (Fisher et al. 1994). Here we also directly test

this aspect.

galaxies, allowing repetitions. In this way,

within one bootstrap realisation a galaxy can be selected more

than once, while some others are never selected. This technique

has been shown to generally lead to some underestimation of the

diagonal errors (Fisher et al. 1994). Here we also directly test

this aspect.

The advantage of using mock samples is that, under the assumption that these are a realistic realisation of the real data, they allow us to obtain a true ensemble average and standard deviation from samples with the same size as the data sample, including both Poissonian noise and cosmic variance. Unfortunately, the covariance properties derived from mock samples are not necessarily a good description of those of the real data, thus making the use of the derived covariance matrix (e.g. in model fitting) doubtful. Conversely, depending on the sample size, jack-knife or volume-bootstrap covariance matrices can exacerbate the peculiarities of some subregions, again not adequately representing the true covariance properties of the data.

| |

Figure 9: -2 Mean of the 24 correlation matrix derived resampling the galaxies of eack KW24 mocks ( left), or resampling 8 equal subvolumes ( center). These are compared to the correlation matrix derived directly from the KW24 mocks ( right). The redshift range considered here is z= [0.5-0.8]. The averaging over the 24 realisations of the 2 left matrices suppress the negative off-diagonal terms, which are sometimes present for a given mock catalogues. Correlation coefficients are then colour-coded from 0 to 1. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

For the present investigation, we put

considerable effort in understanding how to best estimate a

sensible covariance matrix for our

![]() measurements. The

available mock samples were crucial for allowing us to perform

direct comparisons of the performances of the different

techniques. After some initial attempts, we excluded the jack-knife method because of the limited size of the survey

volume. We then directly compared the covariance matrices derived

through the bootstrap technique and from the KW24 mock catalogues.

For the bootstrap method, we decided to directly test how galaxy-

and volume-bootstrap were performing. We concentrated on the

redshift range z= [0.5-0.8] by selecting simulated galaxies

brighter than

measurements. The

available mock samples were crucial for allowing us to perform

direct comparisons of the performances of the different

techniques. After some initial attempts, we excluded the jack-knife method because of the limited size of the survey

volume. We then directly compared the covariance matrices derived

through the bootstrap technique and from the KW24 mock catalogues.

For the bootstrap method, we decided to directly test how galaxy-

and volume-bootstrap were performing. We concentrated on the

redshift range z= [0.5-0.8] by selecting simulated galaxies

brighter than

![]() .

After computing the

correlation function

.

After computing the

correlation function

![]() for all 24 mock samples, we

constructed for each of them a) 100 galaxy-galaxy-bootstrap

samples and b) 100 volume-volume-bootstrap samples. In the latter

case, we considered 8 equal subvolumes, defined as redshift slices

within the redshift range considered. The number of subvolumes was

chosen as the best compromise between having enough of them and

not having volumes that were too small. With this choice, their

volume is

for all 24 mock samples, we

constructed for each of them a) 100 galaxy-galaxy-bootstrap

samples and b) 100 volume-volume-bootstrap samples. In the latter

case, we considered 8 equal subvolumes, defined as redshift slices

within the redshift range considered. The number of subvolumes was

chosen as the best compromise between having enough of them and

not having volumes that were too small. With this choice, their

volume is ![]()

![]() for the samples

with

for the samples

with

![]() and

and

![]() and

and

![]()

![]() for

for

![]() .

The

two bootstrap techniques led to a total of 4800 samples and

corresponding estimates of

.

The

two bootstrap techniques led to a total of 4800 samples and

corresponding estimates of

![]() .

We then calculated the

covariance (and correlation) matrices for each of these two cases,

along with the one derived from the correlation function of the 24

mocks themselves.

.

We then calculated the

covariance (and correlation) matrices for each of these two cases,

along with the one derived from the correlation function of the 24

mocks themselves.

In Fig. 8 we compare the standard

deviations derived from the two bootstrap techniques, to those

derived from the 24 mocks. In each case, these values correspond

by definition to the square root of the diagonal elements of the

covariance matrix. In the plot we show the mean (over the 24

mocks) of the ratio of

![]() from the bootstrap to the

``true'' one from the ensemble of mock surveys. This shows

clearly how the rms values obtained with the

single-galaxy-bootstrap grossly underestimate the true variance,

up to one order of magnitude on large scales. Bootstrapping by

volumes produces a better result, providing a realistic

estimate of

from the bootstrap to the

``true'' one from the ensemble of mock surveys. This shows

clearly how the rms values obtained with the

single-galaxy-bootstrap grossly underestimate the true variance,

up to one order of magnitude on large scales. Bootstrapping by

volumes produces a better result, providing a realistic

estimate of

![]() between 0.1 and 1 h-1 Mpc, and a

20-25% underestimate on larger scales.

between 0.1 and 1 h-1 Mpc, and a

20-25% underestimate on larger scales.

Each element of the the correlation matrix rij is obtained

from the corresponding element of the covariance matrix

![]() as

as

![]() .

By definition, the off-diagonal terms of the

correlation matrix will then range between -1 and 1, indicating

the degree of correlation between different scales of the function

.

By definition, the off-diagonal terms of the

correlation matrix will then range between -1 and 1, indicating

the degree of correlation between different scales of the function

![]() .

Considering the redshift range z= [0.5-0.8], we

show in Fig. 9 the mean of the 24

correlation matrices derived by resampling the galaxies

(left panel) or by resampling 8 equal subvolumes (centre), 100

times each. These are compared to the correlation matrix directly

derived from the 24 mocks (right panel). The first case shows a

mainly diagonal correlation matrix where off-diagonal terms are

mostly noise. In the second case they instead decrease smoothly

from 1 to 0 as a function of bin separation. The matrix derived

from the 24 mocks shows high correlation on all scales.

.

Considering the redshift range z= [0.5-0.8], we

show in Fig. 9 the mean of the 24

correlation matrices derived by resampling the galaxies

(left panel) or by resampling 8 equal subvolumes (centre), 100

times each. These are compared to the correlation matrix directly

derived from the 24 mocks (right panel). The first case shows a

mainly diagonal correlation matrix where off-diagonal terms are

mostly noise. In the second case they instead decrease smoothly

from 1 to 0 as a function of bin separation. The matrix derived

from the 24 mocks shows high correlation on all scales.

Table 4: The five main eigenvalules of the correlation matrix derived with the bootstrap resampling of galaxies (first column) and subvolumes (Col. 2), and from the ensemble variance of the 24 mocks (Col. 3).

In order to directly compare the properties of the correlation

matrices derived with the 3 methods, we compute the principal

components and the amplitudes of the corresponding eigenvalues

![]() (i= 1-12) for each of the 24+24+1 matrices. The

sum of the eigenvalues of a correlation matrix is always equal to

its dimension, i.e. 12 in our case. We report in

Table 4 the values of the five main eigenvalues

obtained with the 24 mocks (first column) compared to the averages

over the 24 mocks of those obtained with the two resampling

methods. The numbers show that the correlation matrix derived from

the 24 mocks essentially contains four principal components and is

mostly dominated by one of them. This indicates a strong

correlation in the data. The bootstrap matrices, instead, show

more than five non-negligible components, with the fifth one the

same order of magnitude as the second in the mock matrix. This

implies a lower correlation. We note, however, that volume

resampling tends to produce a matrix whose structure is closer to

that of the mocks, with 1-2 dominant components. This is another

indication of how volume-bootstrapping, although not perfectly

reproducing the intrinsic covariance properties of the sample,

better estimates the variance and correlation in the data than

does a galaxy-galaxy-bootstrap.

(i= 1-12) for each of the 24+24+1 matrices. The

sum of the eigenvalues of a correlation matrix is always equal to

its dimension, i.e. 12 in our case. We report in

Table 4 the values of the five main eigenvalues

obtained with the 24 mocks (first column) compared to the averages

over the 24 mocks of those obtained with the two resampling

methods. The numbers show that the correlation matrix derived from

the 24 mocks essentially contains four principal components and is

mostly dominated by one of them. This indicates a strong

correlation in the data. The bootstrap matrices, instead, show

more than five non-negligible components, with the fifth one the

same order of magnitude as the second in the mock matrix. This

implies a lower correlation. We note, however, that volume

resampling tends to produce a matrix whose structure is closer to

that of the mocks, with 1-2 dominant components. This is another

indication of how volume-bootstrapping, although not perfectly

reproducing the intrinsic covariance properties of the sample,

better estimates the variance and correlation in the data than

does a galaxy-galaxy-bootstrap.

![\begin{figure}\par\includegraphics[width=12cm]{12314f10.ps} \end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/38/aa12314-09/Timg102.png) |

Figure 10:

Projected correlation function

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

These experiments are extended and further discussed in our

parallel accompanying papers, in particular Porciani et al. (in

preparation). The bottom-line result of our extensive

investigations is that a volume-bootstrap provides a good enough

reconstruction of the intrinsic covariance matrix of the data set,

if enough resamplings are used. This is obtained at the expense of

a slightly less accurate account of cosmic variance on large scale

than what can be obtained from the scatter among mock samples,

where wavelengths longer than the survey size can be sampled.

However, we have shown (Fig. 8) that this

effect on scales ![]() 10 h-1 Mpc is limited to

10 h-1 Mpc is limited to ![]() 20%.

20%.

8 Dependence of galaxy clustering on luminosity

8.1 Luminosity dependence at fixed redshift

Figure 10 shows the projected correlation

function

![]() estimated for our nine luminosity-selected

subsamples at different redshifts. Error bars correspond to the

estimated for our nine luminosity-selected

subsamples at different redshifts. Error bars correspond to the

![]() dispersion provided by 200 volume-bootstrap resamplings,

as extensively discussed in Sect. 7.

dispersion provided by 200 volume-bootstrap resamplings,

as extensively discussed in Sect. 7.

No clear dependence on luminosity is observed within any of the

three redshift ranges. Also, in the shape of

![]() ,

there is some

hint of the usual ``shoulder'', i.e. a change in slope around

1 h-1 Mpc, but no clear separation between the

expected 1-halo term on small scales and the 2-halo

component above this scale (see the Introduction for definitions).

In particular, in the intermediate-redshift bin, all subsamples

show a rather flat large-scale slope, with no evidence of the

usual breakdown above

,

there is some

hint of the usual ``shoulder'', i.e. a change in slope around

1 h-1 Mpc, but no clear separation between the

expected 1-halo term on small scales and the 2-halo

component above this scale (see the Introduction for definitions).

In particular, in the intermediate-redshift bin, all subsamples

show a rather flat large-scale slope, with no evidence of the

usual breakdown above ![]() 2 h-1 Mpc.

2 h-1 Mpc.

| |

Figure 11:

Iso-correlation contours of

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}\par\includegraphics[width=12cm]{12314f12.ps} \end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/38/aa12314-09/Timg104.png) |

Figure 12:

Sensitivity of the projected function

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

To try to understand the origin of the observed flat shape, it is

interesting to look directly at the contour plots of the

bi-dimensional redshift-space correlation function

![]() .

These are shown in Fig. 11 for the three

luminosity-selected subsamples L1.4, L2.2 and L3.1 (see

Table 1 for definitions), which include galaxies

brighter than

.

These are shown in Fig. 11 for the three

luminosity-selected subsamples L1.4, L2.2 and L3.1 (see

Table 1 for definitions), which include galaxies

brighter than

![]() .

The three contour

plots show some interesting features. First, one clearly notices

the much stronger distortion along the line of sight

.

The three contour

plots show some interesting features. First, one clearly notices

the much stronger distortion along the line of sight ![]() ,

in the

central panel. At the same time,

a much more extended signal is

also observed along the perpendicular direction

,

in the

central panel. At the same time,

a much more extended signal is

also observed along the perpendicular direction ![]() in the same

redshift range. It is tempting to interpret both these effects as

produced in some way by the two dominating structures that we

showed in Fig. 6. The excess

signal along the line of sight is very plausibly due to the

distortions by ``Fingers of God'', due to an anomalous number of

virialised systems (groups and clusters) within these structures.

At the same time, the extension along

in the same

redshift range. It is tempting to interpret both these effects as

produced in some way by the two dominating structures that we

showed in Fig. 6. The excess

signal along the line of sight is very plausibly due to the

distortions by ``Fingers of God'', due to an anomalous number of

virialised systems (groups and clusters) within these structures.

At the same time, the extension along ![]() indicates that there

is also an excess of pairs perpendicular to the line of sight,

with respect to an isotropic distribution. In fact, we know

(Scoville et al. 2007b; Guzzo et al. 2007) that the large-scale structure

at

indicates that there

is also an excess of pairs perpendicular to the line of sight,

with respect to an isotropic distribution. In fact, we know

(Scoville et al. 2007b; Guzzo et al. 2007) that the large-scale structure

at

![]() extends over a large part of the COSMOS area.

This evidently biases the observed number of pairs along

extends over a large part of the COSMOS area.

This evidently biases the observed number of pairs along ![]() ,

for simple geometrical reasons. We cannot exclude that part of the

large-scale compression observed in

,

for simple geometrical reasons. We cannot exclude that part of the

large-scale compression observed in

![]() is also

generated by an excess of galaxy infall onto this structure, thus

producing what is known as the Kaiser effect

(Kaiser 1987). This effect is proportional to the growth

of structure (see e.g. Guzzo et al. 2008, for a recent direct

estimate at similar redshift) and can be extracted when the

underlying clustering can be assumed to be isotropic. In this case

it is in practice impossible to disentangle this dynamical

distortion from the geometrical anisotropy generated by having one

dominating structure elongated perpendicular to the line of sight.

is also

generated by an excess of galaxy infall onto this structure, thus

producing what is known as the Kaiser effect

(Kaiser 1987). This effect is proportional to the growth

of structure (see e.g. Guzzo et al. 2008, for a recent direct

estimate at similar redshift) and can be extracted when the

underlying clustering can be assumed to be isotropic. In this case

it is in practice impossible to disentangle this dynamical

distortion from the geometrical anisotropy generated by having one

dominating structure elongated perpendicular to the line of sight.

The flatter shape in

![]() in Fig. 10 is also consistent

with the overdense samples of Abbas & Sheth (2007), who notice not only a higher amplitude

for the most overdense (10% and 30%) samples of mock and SDSS galaxies,

but also a flattening in the correlation function compared to the full sample.

This is another line of evidence favouring the hypothesis that the zCOSMOS field is

centred on an overdensity.

in Fig. 10 is also consistent

with the overdense samples of Abbas & Sheth (2007), who notice not only a higher amplitude

for the most overdense (10% and 30%) samples of mock and SDSS galaxies,

but also a flattening in the correlation function compared to the full sample.

This is another line of evidence favouring the hypothesis that the zCOSMOS field is

centred on an overdensity.

The plots of Fig. 11 also explicitly show

the reasons for our choice of

![]() h-1 Mpc as

the upper integration limit in computating

h-1 Mpc as

the upper integration limit in computating

![]() ,

a value that

provides a reasonable compromise between including most of the

signal and excluding the noisiest regions in the upper part the

diagrams. In the central redshift bin, however, some real

clustering power may still be present above this scale, for small

,

a value that

provides a reasonable compromise between including most of the

signal and excluding the noisiest regions in the upper part the

diagrams. In the central redshift bin, however, some real

clustering power may still be present above this scale, for small

![]() 's. In Fig. 12 we show directly how

's. In Fig. 12 we show directly how

![]() changes, when

changes, when

![]() is extended from 20 to

30 h-1 Mpc. We see that, somewhat counter

intuitively, below 1 h-1 Mpc, no extra amplitude is

gained, while - as indicated by the mock experiments (see

Sect. 5) - the scatter is increased.

Conversely, one can see the slight scale-dependent bias on the

amplitude at larger separations, which gets up to

is extended from 20 to

30 h-1 Mpc. We see that, somewhat counter

intuitively, below 1 h-1 Mpc, no extra amplitude is

gained, while - as indicated by the mock experiments (see

Sect. 5) - the scatter is increased.

Conversely, one can see the slight scale-dependent bias on the

amplitude at larger separations, which gets up to ![]() 10% at

15 h-1 Mpc when increasing

10% at

15 h-1 Mpc when increasing

![]() .

.

8.2 Redshift evolution at fixed (evolving) luminosity

In Sect. 4.1 we discussed how our luminosity selection was devised such as to account for the average evolution in the luminosity of galaxies, assuming this to be the dominant effect in modifying the mean density of objects at any given luminosity. Under this assumption, it is then interesting to test how

9 Dependence of galaxy clustering on stellar mass

The relation of clustering properties to galaxy stellar masses is in principle more informative and straightforward for interpreting because stellar mass is a more fundamental physical parameter than luminosity.

9.1 Mass dependence at fixed redshift

Also in the case of stellar mass dependence, it is interesting to look at the shape of the full correlation function

![\begin{figure}\par\includegraphics[width=12cm]{12314f13.ps} \end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/38/aa12314-09/Timg107.png) |

Figure 13:

Evolution of the projected function

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| |

Figure 14:

Example of full redshift-space correlation function

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}\par\includegraphics[width=12cm]{12314f15.ps} \end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/38/aa12314-09/Timg109.png) |

Figure 15:

The projected correlation function

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}\par\includegraphics[width=12cm]{12314f16.ps} \end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/38/aa12314-09/Timg110.png) |

Figure 16:

Evolution of the projected function

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

Figure 15 shows the projected correlation function

![]() of the 10 mass-selected samples. The plotted points are

not corrected for the residual stellar mass incompleteness (see

Sect. 6.3). Errors are estimated as in the

luminosity case using 200 bootstrap resamplings of 8 equal

subvolumes of each data set. The figure shows a weak mass

dependence of clustering in the low- and high-redshift bins, in

particular at small separations. At the same time, a strong

dependence at all separations is evident in the

intermediate-redshift slice. There, the slope of

of the 10 mass-selected samples. The plotted points are

not corrected for the residual stellar mass incompleteness (see

Sect. 6.3). Errors are estimated as in the

luminosity case using 200 bootstrap resamplings of 8 equal

subvolumes of each data set. The figure shows a weak mass

dependence of clustering in the low- and high-redshift bins, in

particular at small separations. At the same time, a strong

dependence at all separations is evident in the

intermediate-redshift slice. There, the slope of

![]() remains

extremely flat out to the largest explored scales, even more

strongly than in the luminosity-selected cases. Finally, in the

low- and high-redshift bins there is evidence of a

steeper ``1-halo term'' contribution at

remains

extremely flat out to the largest explored scales, even more

strongly than in the luminosity-selected cases. Finally, in the

low- and high-redshift bins there is evidence of a

steeper ``1-halo term'' contribution at