| Issue |

A&A

Volume 504, Number 1, September II 2009

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Page(s) | 259 - 276 | |

| Section | Planets and planetary systems | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/200911760 | |

| Published online | 15 July 2009 | |

A grid of polarization models for Rayleigh scattering planetary atmospheres![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

E. Buenzli - H. M. Schmid

Institute for Astronomy, ETH Zurich, 8093 Zurich, Switzerland

Received 30 January 2009 / Accepted 27 June 2009

Abstract

Context. Reflected light from giant planets is polarized by scattering, offering the possibility of investigating atmospheric properties with polarimetry. Polarimetric measurements are available for the atmospheres of solar system planets, and instruments are being developed to detect and study the polarimetric properties of extrasolar planets.

Aims. We investigate the intensity and polarization of reflected light from planets in a systematic way with a grid of model calculations. Comparison of the results with existing and future observations can be used to constrain parameters of planetary atmospheres.

Methods. We present Monte Carlo simulations for planets with Rayleigh scattering atmospheres. We discuss the disk-integrated polarization for phase angles typical of extrasolar planet observations and for the limb polarization effect observable for solar system objects near opposition. The main parameters investigated are single scattering albedo, optical depth of the scattering layer, and albedo of an underlying Lambert surface for a homogeneous Rayleigh scattering atmosphere. We also investigate atmospheres with isotropic scattering and forward scattering aerosol particles, as well as models with two scattering layers.

Results. The reflected intensity and polarization depend strongly on the phase angle, as well as on atmospheric properties, such as the presence of absorbers or aerosol particles, column density of Rayleigh scattering particles and cloud albedo. Most likely to be detected are planets that produce a strong polarization flux signal because of an optically thick Rayleigh scattering layer. Limb polarization depends on absorption in a different way than the polarization at large phase angles. It is especially sensitive to a vertical stratification of absorbers. From limb polarization measurements, one can set constraints on the polarization at large phase angles.

Conclusions. The model grid provides a tool for extracting quantitative results from polarimetric measurements of planetary atmospheres, in particular on the scattering properties and stratification of particles in the highest atmosphere layers. Spectropolarimetry of solar system planets offers complementary information to spectroscopy and polarization flux colors can be used for a first characterization of exoplanet atmospheres.

Key words: polarization - scattering - techniques: polarimetric - planetary systems - planets and satellites: general

1 Introduction

Light reflected from planetary atmospheres is generally polarized. The reflection is the result of different types of scattering particles with characteristic polarization properties. Polarimetric observations therefore provide information on the atmospheric structure and on the nature of scattering particles that complements other observations. Systematic model calculations are required to interpret the available polarimetry from solar system planets and prepare for future polarimetric measurements of extrasolar planets.

Scattering processes.

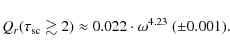

Rayleigh scattering occurs on particles much smaller than the

wavelength of the scattered light. This process produces 100%

polarization for a single right angle scattering.

Rayleigh scattering is much stronger for short wavelengths because

the cross section behaves like

![]() ,

and it

favors forward and backward scattering, which are both equally strong.

The blue sky in Earth's atmosphere is a well known example of

Rayleigh scattering by molecules.

,

and it

favors forward and backward scattering, which are both equally strong.

The blue sky in Earth's atmosphere is a well known example of

Rayleigh scattering by molecules.

Aerosol haze particles with a size roughly comparable to the

wavelength can produce strongly forward directed

scatterings. Depending on the structure of the particle, a high

(p>90%) or low (

![]() %)

fractional polarization results for a scattering angle of

%)

fractional polarization results for a scattering angle of ![]() .

For example, the maximum polarization

for scattering by optically thin zodiacal or cometary dust is not more

than

.

For example, the maximum polarization

for scattering by optically thin zodiacal or cometary dust is not more

than

![]() % (e.g. Leinert et al. 1981; Levasseur-Regourd et al. 1996), while a polarization close to 100% is inferred for single scattering of haze

particles in Saturn's moon Titan (Tomasko et al. 2008).

% (e.g. Leinert et al. 1981; Levasseur-Regourd et al. 1996), while a polarization close to 100% is inferred for single scattering of haze

particles in Saturn's moon Titan (Tomasko et al. 2008).

Liquid droplets in clouds produce a polarization because of

refraction and reflection, which can be particularly high (>50%) for scattering angles of about ![]() for spherical water droplets,

corresponding to the primary rainbow (see e.g. Bailey

2007). Clouds made of ice crystals reflect and refract light

in many different ways, and no distinct polarization features like rainbows are

expected, except locally, where ice crystals may have very similar structures.

for spherical water droplets,

corresponding to the primary rainbow (see e.g. Bailey

2007). Clouds made of ice crystals reflect and refract light

in many different ways, and no distinct polarization features like rainbows are

expected, except locally, where ice crystals may have very similar structures.

Multiple scatterings in planetary atmospheres randomize the polarization direction of the single scatterings and lower the observable polarization significantly. Therefore the net polarization of the reflected light depends not only on the scattering angle and the properties of the scattering particles, but also on the atmospheric structure. For this reason it is not suprising that a large diversity of polarization properties exists for the solar system planets.

Observations.

Venus shows a low (<5%) negative polarization, which is a polarization parallel to the scattering plane, for most phase angles . In the blue and UV, a rainbow feature with a positive polarization of several percent is present (e.g. Coffeen & Gehrels 1969; Dollfus & Coffeen 1970), indicating that the reflection occurs mainly from droplets in optically thick clouds (Hansen & Hovenier 1974).

For the giant planets, only observations near opposition are possible with earth-bound observations. Near opposition the disk-integrated polarization is low because single back-scattering is unpolarized and multiple scattering polarization cancels for a symmetric planet.

With disk-resolved observations of Jupiter, Lyot (1929) first detected that the Jovian poles show a strong limb polarization of order 5-10%. To understand this effect one has to consider a back-scattering situation at the limb of a sphere, where locally we have a configuration of grazing incidence and grazing emergence (for a plane parallel atmosphere) for the incoming and the back-scattered photons, respectively. Photons scattered upwards will mostly escape without a second scattering, and photons scattered down have a low probability of being reflected towards us after the second scattering, but a high probability of being absorbed or undergoing multiple scatterings. Thus photons that are reflected towards us by two scatterings travel predominantely parallel to the surface. Because the polarization angle induced in a single dipole-type scattering process, like Rayleigh scattering, is perpendicular to the propagation direction of the incoming photon, a polarization perpendicular to the limb is produced.

Measurements at large phase angles

![]() for Jupiter with

spacecrafts detected a polarization of

for Jupiter with

spacecrafts detected a polarization of

![]() % for the poles while the

polarization is much lower (<10%) for the equatorial region

(Smith & Tomasko 1984).

The high polarization at the poles can be explained by reflection from

a scattering aerosol haze layer, while the polarization at the equator is low

because of reflection from clouds. Towards short wavelengths (blue) the

polarization at the equator increases strongly, indicating that also

Rayleigh scattering contributes to the resulting polarization.

% for the poles while the

polarization is much lower (<10%) for the equatorial region

(Smith & Tomasko 1984).

The high polarization at the poles can be explained by reflection from

a scattering aerosol haze layer, while the polarization at the equator is low

because of reflection from clouds. Towards short wavelengths (blue) the

polarization at the equator increases strongly, indicating that also

Rayleigh scattering contributes to the resulting polarization.

For Saturn the polarization is qualitatively similar to Jupiter with an enhanced polarization at the poles at short wavelengths (blue). In the red the polarization level of the poles is lower than for Jupiter (Tomasko & Doose 1984).

Uranus and Neptune display a strong limb polarization along the entire limb (Schmid et al. 2006a; Joos & Schmid 2007). Albedo spectra (e.g. Baines & Bergstralh 1986) and the polarization indicate that Rayleigh scattering is predominant in these atmospheres.

An interesting case is Saturn's moon Titan, which has a thick

scattering layer of photochemical haze that produces a very

high disk-integrated polarization of ![]() % in the B and

R band (Tomasko & Smith 1982). More recently the Huygens

probe measured the scattering and polarization properties of the aerosol

particles in great detail during its descent through Titan's

atmosphere (Tomasko et al. 2008).

% in the B and

R band (Tomasko & Smith 1982). More recently the Huygens

probe measured the scattering and polarization properties of the aerosol

particles in great detail during its descent through Titan's

atmosphere (Tomasko et al. 2008).

The observations show that Rayleigh scattering is

an important polarigeneric process in atmospheres of solar system

objects, in particular for Uranus and Neptune, and for the equatorial regions of

Jupiter and Saturn. Besides Rayleigh scattering one has to consider the reflection from

haze particles (aerosols). Scattering by small aerosol particles

![]() may be approximated by Rayleigh scattering. For

large particles,

may be approximated by Rayleigh scattering. For

large particles,

![]() ,

the strong forward scattering effect

and the reduced polarization for right angle scattering cause

significant differences when compared to Rayleigh scattering.

,

the strong forward scattering effect

and the reduced polarization for right angle scattering cause

significant differences when compared to Rayleigh scattering.

Clouds dominate in the atmosphere of Venus, and at longer wavelengths (red) also in Saturn and Jupiter. The reflection from clouds produces only a low positive or even negative polarization signal in Venus, Saturn or Jupiter, typically at a level p <5%. In a first approximation one may therefore treat clouds like a diffusely scattering layer producing no polarization.

Polarimetric measurements of stellar systems with known extrasolar planets were attempted, but up to now no convincing detection of the polarized reflected light from an extrasolar planet has been made (Lucas et al. 2009; Wiktorowicz 2009). The deduced upper limits on the polarization flux from the close-in planet indicate that these objects are not covered with a well reflecting Rayleigh scattering layer.

Model calculations.

The classical theory for the analytic solution of the multiple scattering problem is treated in the seminal work of Chandrasekhar (1950), from which the polarization of conservative (non-absorbing) Rayleigh scattering planets can be derived. Van de Hulst (1980) gives a comprehensive overview on theoretical work up to that time including many numerical model results.

Schmid et al. (2006a) put together available model results useful for parameter studies of the polarization from Rayleigh scattering atmospheres. This includes the following model results:

- phase curves for the disk-integrated intensity and polarization for finite, conservative (no absorption) Rayleigh scattering atmospheres for different optical thicknesses and ground albedos from Kattawar & Adams (1971);

- the limb polarization at opposition for semi-infinite Rayleigh scattering atmospheres with different single scattering albedos derived from formulas and tabulated functions given in Abhyankar & Fymat (1970, 1971) and Chandrasekhar (1950);

- the limb polarization at opposition for finite, conservative (no absorption) Rayleigh scattering atmospheres for different optical thicknesses and ground albedos from tabulations given in Coulson et al. (1960).

Another line of investigation now concentrates on the expected polarization of extrasolar planets. The Rayleigh and Mie scattering polarization of close-in planets was investigated by Seager et al. (2000). These calculations consider planets which are unresolved from their central star and the polarization signal is strongly diluted by the unpolarized stellar light.

Stam et al. (2004) modeled the polarization of a Jupiter-like extrasolar planet with methane absorption bands for three special cases and presented polarization spectra and wavelength integrated phase curves. Also monochromatic phase curves for a non-absorbing clear and a hazy atmosphere are available (Stam et al. 2006). Other studies determined the expected polarization from clouds of terrestrial planets (e.g. Bailey 2007) or the polarization of extrasolar analogs to Earth (Stam 2008).

Despite all these models systematic model calculations are sparse in the literature. For finite Rayleigh scattering atmospheres, polarization phase curves have been calculated only for few selected cases. No results are available for the limb polarization of atmospheres with finite thickness and absorption.

It is the goal of this paper to present a grid of model results for Rayleigh scattering models with absorption and to explore the model parameter space in a systematic way. The results should allow a comparison with observations and provide a tool for their interpretation. Additionally effects of selected deviations from simple Rayleigh scattering models will be discussed.

In the next section the paper describes our scattering model and the

Monte Carlo simulations. Section 3 presents the results from a

comprehensive Rayleigh scattering model grid covering the three atmosphere

parameters: single scattering albedo ![]() ,

optical thickness of the Rayleigh

scattering layer

,

optical thickness of the Rayleigh

scattering layer

![]() ,

and albedo of the underlying reflecting

surface

,

and albedo of the underlying reflecting

surface ![]() .

In Sect. 4 we explore the effects of a mixure of isotropic and Rayleigh scattering, of particles with a forward scattering phase function, and of two polarizing layers. In Sect. 5 we discuss spectral dependences. Section 6 highlights some special cases and diagnostic diagrams which may be of particular interest for the interpretation of

observational data. A discussion and conclusions are given in the final

section. Appendix A describes the tables with the numerical results of our calculations of intensity and polarization phase curves for a grid of 333 model parameter combinations. These are available in electronic form at the CDS.

.

In Sect. 4 we explore the effects of a mixure of isotropic and Rayleigh scattering, of particles with a forward scattering phase function, and of two polarizing layers. In Sect. 5 we discuss spectral dependences. Section 6 highlights some special cases and diagnostic diagrams which may be of particular interest for the interpretation of

observational data. A discussion and conclusions are given in the final

section. Appendix A describes the tables with the numerical results of our calculations of intensity and polarization phase curves for a grid of 333 model parameter combinations. These are available in electronic form at the CDS.

2 Model description

Our planet model consists of a spherical body of radius R, illuminated

by a parallel beam. This geometry is appropriate for not rapidely rotating

planets with a large separation, ![]() ,

from the parent star.

Each surface element is approximated by a plane parallel atmosphere. This

simplification is reasonable for planets

without an extended, tenuous atmosphere.

,

from the parent star.

Each surface element is approximated by a plane parallel atmosphere. This

simplification is reasonable for planets

without an extended, tenuous atmosphere.

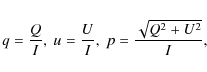

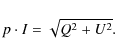

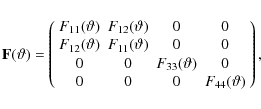

2.1 Intensity and polarization parameters

The intensity and polarization of the reflected light is described by the

Stokes vector

![]() .

The linear polarized

intensity or polarization flux is defined by the parameters

Q=I0-I90 and

U=I45-I135, where the indices

stand for the polarization direction with respect to a specified direction

in the selected coordinate system. In this paper only processes producing

linear polarization are studied and therefore the Stokes parameter V

for the circular polarization is omitted.

We express the fractional polarization by the symbols

.

The linear polarized

intensity or polarization flux is defined by the parameters

Q=I0-I90 and

U=I45-I135, where the indices

stand for the polarization direction with respect to a specified direction

in the selected coordinate system. In this paper only processes producing

linear polarization are studied and therefore the Stokes parameter V

for the circular polarization is omitted.

We express the fractional polarization by the symbols

|

(1) |

and the polarized intensity

|

(2) |

For the study of the limb polarization in resolved solar system planets at opposition we introduce the radial Stokes parameter Qr, which is positive for an orientation of the polarization parallel to the radius vector

The radial polarization curves qr(r) and Qr(r) can only be observed if the planetary disk is well resolved. The measured radial profile depends strongly on the achieved spatial resolution. Because of the limited spatial resolution of most observations it is very hard to exactly measure the polarization near the limb. It is much less difficult to evaluate a disk-integrated polarization or polarization flux and to estimate and correct the degradation of the observed value with respect to the intrinsic value with a simulation of the observational resolution or point spread function. This approach is described in detail in Schmid et al. (2006a) for seeing limited polarimetry of Uranus and Neptune.

Therefore we mainly discuss the intensity weighted

polarization

![]() ,

which is the equivalent to

the disk-integrated radial polarization

,

which is the equivalent to

the disk-integrated radial polarization

![]() normalized to the geometric albedo.

The geometric albedo

normalized to the geometric albedo.

The geometric albedo

![]() is the disk-integrated reflected intensity

of a given model at opposition normalized to the reflection of a white Lambertian disk. It corresponds to

is the disk-integrated reflected intensity

of a given model at opposition normalized to the reflection of a white Lambertian disk. It corresponds to

![]() in our calculations.

in our calculations.

The radial polarization curves are qualitatively similar for most models. The

shape of the intensity curve varies significantly from limb darkening to limb brightening for different

model parameteres and cannot

solely be described by the geometric albedo. Additionally we choose the Minnaert law exponent k as fit parameter for the shape of the center-to-limb intensity curve.

The Minnaert law for opposition is

![]() ,

where

,

where

![]() .

This yields the following one-parameter fit curve

I(r) = Ir=0 (1-r2)k-1/2.

.

This yields the following one-parameter fit curve

I(r) = Ir=0 (1-r2)k-1/2.

2.2 Atmosphere parameters

The plane parallel atmosphere is assumed to consist of a homogeneous scattering layer that is either semi-infinite or finite with a reflecting (cloud or ground) Lambertian surface layer with a surface albedo. The basic model atmospheres are described by three parameters:

- the single scattering albedo

;

;

- the (vertical) optical thickness for scattering,

,

of the scattering layer;

,

of the scattering layer;

- the albedo

of the surface below the scattering layer.

of the surface below the scattering layer.

|

(3) |

The value

The optical depth for scattering

![]() follows from the column density Z of the scattering layer:

follows from the column density Z of the scattering layer:

![]() ,

where

,

where ![]() is the scattering cross section per particle.

The semi-infinite case corresponds to

is the scattering cross section per particle.

The semi-infinite case corresponds to

![]() .

We treat absorption like an addition of absorption optical depth to a

layer with a given scattering optical depth

.

We treat absorption like an addition of absorption optical depth to a

layer with a given scattering optical depth

![]() ,

which is equivalent to reducing the single scattering albedo. This approach is suited for discussing the reflected

intensity and polarization inside and outside of absorption features

like CH4 or H2O-bands, where

,

which is equivalent to reducing the single scattering albedo. This approach is suited for discussing the reflected

intensity and polarization inside and outside of absorption features

like CH4 or H2O-bands, where ![]() differs dramatically while

differs dramatically while ![]() is essentially equal.

Then the total optical thickness

is essentially equal.

Then the total optical thickness ![]() of the layer including absorption

of the layer including absorption ![]() is given by

is given by

|

(4) |

The basic model grid (Sect. 3) considers only Rayleigh scattering (

2.3 Geometric parameters

The geometric parameters describe the location of the considered

surface point P and the escape direction of the photons (Fig. 1).

A global coordinate system describes the orientation of the planet with respect to the star. Its polar axis is the surface normal at the sub-stellar point S', and the location of each point P is described by polar angle ![]() and azimuthal angle

and azimuthal angle ![]() (not drawn).

(not drawn). ![]() is also the photon's angle of incidence at point P. The escape direction, i.e. the location of the observer, is given by a polar angle

is also the photon's angle of incidence at point P. The escape direction, i.e. the location of the observer, is given by a polar angle ![]() and azimuthal angle

and azimuthal angle ![]() (not drawn).

(not drawn). ![]() is equivalent to the phase angle defined by the three (central) points: star or sun S, planet 0, and observer E (Earth).

is equivalent to the phase angle defined by the three (central) points: star or sun S, planet 0, and observer E (Earth).

For the description of the scattering processes, a local coordinate system is set up at point P for the plane parallel atmosphere with surface normal z perpendicular to the planet surface in P, polar angle ![]() and azimuthal angle

and azimuthal angle ![]() .

.

|

Figure 1: Model geometry. The dashed line represents the trajectory of a reflected photon. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

In general, each point P can have individual atmospheric properties. Then

the model outputs, the Stokes vector components I, Q and U, depend each on seven parameters:

This description allows calculation of the reflected intensity and polarization of each surface point on the illuminated hemisphere viewed from any direction. Obviously this large parameter space needs to be simplified for a first parameter analysis. If we adopt the same atmospheric structure everywhere on the planet,

For extrasolar planets it will not be

possible to resolve the disk in the near future. For disk-integrated results we can eliminate the dependence

of the reflected intensity and polarization on the surface point parameters ![]() and

and ![]() .

Because of the rotational symmetry of the geometric model, the

intensity and the polarization then only depend on the polar

viewing angle or phase angle

.

Because of the rotational symmetry of the geometric model, the

intensity and the polarization then only depend on the polar

viewing angle or phase angle ![]() .

Moreover the orientation of the

polarization signal is either parallel or perpendicular to the scattering

plane (the plane S-0-E), which we call the Qpolarization direction. Q is defined positive for a polarization

perpendicular to the plane S-0-E and negative for a polarization parallel to this

plane. The U-polarization is zero in this coordinate system for

symmetry reasons.

.

Moreover the orientation of the

polarization signal is either parallel or perpendicular to the scattering

plane (the plane S-0-E), which we call the Qpolarization direction. Q is defined positive for a polarization

perpendicular to the plane S-0-E and negative for a polarization parallel to this

plane. The U-polarization is zero in this coordinate system for

symmetry reasons.

For the full disk the integrated intensity and polarization signals from a planet

depend on the following parameters:

For solar system planets at opposition we obtain a rotationally symmetric scattering geometry (viewing direction is identical to the axis of symmetry of the geometric model). We then have a scattering model which depends only on

For exact opposition the dependences of the scattering model results

can be described by the following parameters:

These are the center to limb intensity curve and the center to limb radial polarization curves which both depend only on the atmospheric parameters.

2.4 Monte Carlo simulations

For our simulations we used the Monte Carlo code described in Schmid

(1992), which was slightly adapted for the case of light reflection

from a planet. Basically the code calculates the random

walk histories of many photons in the planet model atmosphere until the photons have

escaped or are destroyed by an absorption process. After a sufficiently large

number have escaped, the scattering intensity and polarization of the

reflected light can be established for different lines of sight.

In our calculations we assume that despite multiple scatterings the escaping

photons emerge at the same point where they penetrated into the planet.

In each scattering process the photon undergoes a

direction and polarization change calculated from the appropriate phase matrix.

The linear polarization of the photons in the simulations is defined by the

orientation ![]() of the electric vector for the photon's

electromagnetic wave. In a given coordinate system we can then

evaluate the contribution to the Stokes intensity for each photon in

of the electric vector for the photon's

electromagnetic wave. In a given coordinate system we can then

evaluate the contribution to the Stokes intensity for each photon in

![]() and

and

![]() direction.

direction.

The escaping photons have to be collected in discret

direction bins (in our models phase angles

![]() with a finite bin width

with a finite bin width

![]() )

to evaluate

)

to evaluate ![]() and

and ![]() .

These are then a mean photon intensity and polarization for that bin.

.

These are then a mean photon intensity and polarization for that bin.

![]() should be small to resolve any structure in

should be small to resolve any structure in ![]() and

and ![]() ,

but also sufficiently large to collect enough photons for results with small statistical

errors. The aim of our simulations is to reach at least the expected

precision of observational data. The rotational

symmetry imposed on our models helps to increase the bin size for the phase curve

interval

,

but also sufficiently large to collect enough photons for results with small statistical

errors. The aim of our simulations is to reach at least the expected

precision of observational data. The rotational

symmetry imposed on our models helps to increase the bin size for the phase curve

interval ![]() ,

which behaves like

,

which behaves like

![]() .

This means that we have to divide the photon count per bin

by the factor

.

This means that we have to divide the photon count per bin

by the factor

![]() .

The intensity is obtained by normalizing with the reflectivity of a white Lambertian disk.

For a given simulation the relative statistical

errors (photon shot noise) are particularly good for

.

The intensity is obtained by normalizing with the reflectivity of a white Lambertian disk.

For a given simulation the relative statistical

errors (photon shot noise) are particularly good for

![]() ,

much less favorable for

,

much less favorable for

![]() and very bad for

and very bad for

![]() where only a few photons

will be collected, because the irradiated hemisphere of the planet

is almost invisible for this phase angle. For the center-to-limb curves we bin uniformly in

where only a few photons

will be collected, because the irradiated hemisphere of the planet

is almost invisible for this phase angle. For the center-to-limb curves we bin uniformly in

![]() with a bin size of

with a bin size of

![]() ,

which requires an additional normalization by

,

which requires an additional normalization by

![]() .

.

The number of photons per model was chosen such that the

number of reflected photons in phase angle bins relevant for observations (

![]() )

are about

)

are about

![]() when integrated over the whole disk. This corresponds to an error in polarization

when integrated over the whole disk. This corresponds to an error in polarization

![]() %. For the radial curves the total number of photons was increased such that the same precision was reached in most radial bins. No photons emerge at the exact phase angle

%. For the radial curves the total number of photons was increased such that the same precision was reached in most radial bins. No photons emerge at the exact phase angle

![]() .

Therefore for the limb polarization calculations we count all photons that are in the bin

.

Therefore for the limb polarization calculations we count all photons that are in the bin

![]() ,

even though the calculation for the radial polarization includes the assumption that

,

even though the calculation for the radial polarization includes the assumption that

![]() .

The error induced by this measure is smaller than the statistical error.

.

The error induced by this measure is smaller than the statistical error.

A general guideline for the Monte Carlo technique for random walk problems is given in Cashwell & Everett (1959) and many Monte Carlo simulations for the investigation of light scattering are described in the astronomical literature (see e.g. Witt 1991; Code & Whitney 1995; Wolf et al. 1999). In Schmid (1992) a detailed description on many aspects of the employed Monte Carlo code are given; e.g. the general scheme of the code, the required transformations between the involved coordinate systems (star-planet, planet-plane parallel atmosphere, atmosphere-photon), the determination of the free path length, the treatment of isotropic scattering and Rayleigh scattering according to the Rayleigh phase matrix, an assessment of statistical errors, and a comparison with analytical calculations.

3 Model results for a homogeneous Rayleigh scattering atmosphere

This section discusses the model grid results for simple homogeneous Rayleigh scattering atmospheres described by parameters ![]() ,

,

![]() and

and ![]() (cf. Sect. 2.2) We discuss phase curves (Sect. 3.1) and radial profiles (Sect. 3.2) for selected cases and explore the full parameter space for disk-integrated results at

(cf. Sect. 2.2) We discuss phase curves (Sect. 3.1) and radial profiles (Sect. 3.2) for selected cases and explore the full parameter space for disk-integrated results at

![]() and

and

![]() (Sect. 3.3).

(Sect. 3.3).

Many of the general dependences of these model results on atmospheric parameters were already discussed in previous studies mentioned in the introduction (Sect. 1). Compared to these our calculations are much more comprehensive and the extensive model grid results are provided in electronic form (see Appendix A). An overview of the dependence of observable quantities, such as intensity, fractional polarization and polarized intensity, on atmosphere parameters is presented in diagrams which may be useful for the interpretation of observational data.

The results presented in this section are in very good agreement with the previous calculations in Kattawar & Adams (1971), Stam et al. (2006) and Schmid et al. (2006a).

3.1 Phase curves

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=17cm,clip]{11760f02.eps} \end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/34/aa11760-09/Timg102.png) |

Figure 2:

Left: phase dependence of the intensity I, fractional

polarization q and polarized intensity Q for Rayleigh

scattering atmospheres. Right: radial dependence of the intensity I, radial

polarization qr and radial polarized intensity Qr at

opposition. Line styles denote: semi-infinite case

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

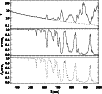

For the investigation of extrasolar planets, the phase dependence of the disk-integrated polarization is of interest. We discuss the phase curve for selected model cases (Fig. 2, left): a semi-infinite and a finite scattering layer with different absorption properties of the scattering and surface layers.

The semi-infinite, conservatively scattering layer is a good reference case for an illuminated sphere and is often used for scattering atmospheres. All irradiated light is reflected after one or several scatterings and the spherical albedo is equal to 1. An intensity phase curve for isotropic scattering is given in van de Hulst (1980), and Bhatia & Abhyankar (1982) published a polarization curve for Rayleigh scattering in graphical form, but no tabulated values could be found in the literature.

In our Monte Carlo simulation we treat

the semi-infinite atmosphere as

![]() and

and

![]() ,

which yields essentially the same

results as an infinite layer but avoids infinite scattering of some

photons. Our results of this case are tabulated in Table 1.

,

which yields essentially the same

results as an infinite layer but avoids infinite scattering of some

photons. Our results of this case are tabulated in Table 1.

Table 1:

Reflectivity ![]() ,

polarization fraction

,

polarization fraction ![]() and polarized intensity

and polarized intensity ![]() phase curves for a very deep

(

phase curves for a very deep

(![]() )

conservative

)

conservative

![]() Rayleigh scattering atmosphere above a perfectly

reflecting Lambert surface (surface albedo

Rayleigh scattering atmosphere above a perfectly

reflecting Lambert surface (surface albedo

![]() ).

).

Intensity:

The intensity phase curves

Of course, the reflected intensity decreases with absorption

(with lower single scattering albedo ![]() )

in the atmosphere and with

the albedo

)

in the atmosphere and with

the albedo ![]() of the underlying surface layer. The effect of

absorption in the scattering atmosphere is important for thick layers,

while the albedo of the underlying surface is important if the optical

depths of the scattering region above is small. A quantitative

description of these dependences is given in Dlugach & Yanovitskij (1974) and Sromovsky (2005b).

of the underlying surface layer. The effect of

absorption in the scattering atmosphere is important for thick layers,

while the albedo of the underlying surface is important if the optical

depths of the scattering region above is small. A quantitative

description of these dependences is given in Dlugach & Yanovitskij (1974) and Sromovsky (2005b).

Polarization fraction.

The disk-integrated polarization fraction

The polarization for the semi-infinite, conservative Rayleigh scattering layer

reaches a maximum of q=32.6% for

![]() .

For reduced scattering albedo, e.g. due to absorption in a molecular band,

.

For reduced scattering albedo, e.g. due to absorption in a molecular band, ![]() increases (see e.g. van de Hulst 1980). This happens because absorption strongly

reduces the fraction of multiply scattered photons in the reflected light which have randomized

polarization directions. If the absorption is

very strong then the reflected light consists essentially only

of photons that made one single Rayleigh scattering. The polarization phase curve

then approaches the Rayleigh scattering

polarization phase function

increases (see e.g. van de Hulst 1980). This happens because absorption strongly

reduces the fraction of multiply scattered photons in the reflected light which have randomized

polarization directions. If the absorption is

very strong then the reflected light consists essentially only

of photons that made one single Rayleigh scattering. The polarization phase curve

then approaches the Rayleigh scattering

polarization phase function

![]() with a polarization close to 100 % at

with a polarization close to 100 % at

![]() .

.

For finite scattering atmospheres the polarization fraction qalso depends on the albedo of the surface layer. In the models discussed in this section the polarization is only produced in the Rayleigh scattering layer, while reflection from the surface layer is unpolarized. Therefore the resulting polarization is low for a high surface albedo and high for a low surface albedo (see e.g. Kattawar & Adams 1971; Stam 2008). This reflects the relative contribution of the polarized light from the scattering layer with respect to the unpolarized light reflected from the surface underneath.

The peak of the polarization curve is shifted towards large phase

angles (

![]() )

for models with thin scattering layers and

high surface albedos, as previously described by Kattawar & Adams

(1971). At large

phase angles (

)

for models with thin scattering layers and

high surface albedos, as previously described by Kattawar & Adams

(1971). At large

phase angles (

![]() ), when only a planet crescent is visible, the fraction of

scattered photons hitting the planet initially under grazing

incidence is relatively high. For a thin scattering layer grazing

incidence helps to enhance the probability for a polarizing Rayleigh scattering.

For this reason the polarized

light from the Rayleigh scattering atmosphere is less diluted by

unpolarized light reflected from the surface at large phase angles and

the fractional polarization is higher.

), when only a planet crescent is visible, the fraction of

scattered photons hitting the planet initially under grazing

incidence is relatively high. For a thin scattering layer grazing

incidence helps to enhance the probability for a polarizing Rayleigh scattering.

For this reason the polarized

light from the Rayleigh scattering atmosphere is less diluted by

unpolarized light reflected from the surface at large phase angles and

the fractional polarization is higher.

Polarized intensity.

The polarized intensityThe polarized intensity decreases with increasing absorption, because the drop in intensity is stronger than the increase in fractional polarization. The polarization flux is a rough measure for the number of reflected photons undergoing one single Rayleigh scattering. Second and higher order scatterings also add to the polarized intensity, but only at a much lower level. Adding absorption can only reduce the number of such scatterings and therefore diminishes the polarized intensity.

A very important property of the polarization flux Q is that it

does not depend on the albedo of the surface layer ![]() (assumed to produce no

polarization) below the scattering region.

(assumed to produce no

polarization) below the scattering region.

3.2 Radial dependence for resolved planetary disks at opposition

For the interpretation of the limb polarization of solar system objects close to opposition, we discuss the radial or center-to-limb dependence of the intensity I(r), the radial polarization qr(r) and the radial polarized intensity Qr(r) (Fig. 2, right) for the same model parameters as for the phase curves in Sect. 3.1.

Intensity:

The radial intensity curve I(r) shows a pronounced limb darkening in the semi-infinite conservative case. For a strongly absorbing atmosphere, e.g. within an absorption band, the I(r)-curve becomes essentially flat. Thus for an absorbing (and homogeneous) semi-infinite atmosphere limb brightening cannot be produced. For comparison the center-to-limb intensity curve I(r) for isotropic scattering and for a Lambert sphere (

For finite scattering atmospheres with an optically thin layer the

center-to-limb intensity curve can show a limb brightening

effect. Limb brightening occurs for a highly reflective scattering

layer (high ![]() )

located above a dark surface (low

)

located above a dark surface (low ![]() ), e.g. a thin aerosol layer or a methane-poor layer above the methane-rich absorbing layer (e.g. Price 1978). Limb brightening is observed in solar system planets in deep absorption band (e.g. Karkoschka 2001; Sromovsky & Fry 2007). Limb brightening is investigated in more detail in Sect. 3.2.1.

), e.g. a thin aerosol layer or a methane-poor layer above the methane-rich absorbing layer (e.g. Price 1978). Limb brightening is observed in solar system planets in deep absorption band (e.g. Karkoschka 2001; Sromovsky & Fry 2007). Limb brightening is investigated in more detail in Sect. 3.2.1.

Radial polarization fraction:

The radial polarization fraction qr(r) is always zero in the disk center because of the symmetry of the scattering situation. For all cases the polarization increases steadily towards the limb and reaches a maximum value close to the limb between r=0.95 and 1.0. The polarization qr(r) is always positive, which means a radial polarization direction or limb polarization perpendicular to the limb.

It is important to note that the limb polarization decreases with

decreasing single scattering albedo ![]() (more absorption) in

contrast to the situation at large phase angles.

This indicates that the photons producing the limb

polarization are more strongly reduced by

absorption than the reflected ``unpolarized'' photons.

(more absorption) in

contrast to the situation at large phase angles.

This indicates that the photons producing the limb

polarization are more strongly reduced by

absorption than the reflected ``unpolarized'' photons.

The explanation is that singly scattered (i.e. backscattered) photons

do not contribute to the limb

polarization, while reflected photons scattered twice or a few times are responsible

for the largest part of the limb polarization. Absorption implies

that a larger fraction of escaping photons are singly-scattered and therefore

unpolarized at opposition. Note however that for the semi-infinite atmosphere,

the maximum radial polarization is not reached in the conservative

case. A slightly lower scattering albedo (

![]() )

mostly reduces the amount of highest order scatterings

and thus the polarization fraction is somewhat enhanced when

compared to the conservative case

(see Schmid et al. 2006a,

and Fig. 7 in Sect. 3.3).

)

mostly reduces the amount of highest order scatterings

and thus the polarization fraction is somewhat enhanced when

compared to the conservative case

(see Schmid et al. 2006a,

and Fig. 7 in Sect. 3.3).

The fractional limb polarization qr(r) for finite scattering layers depends

strongly on the albedo of the underlying surface ![]() :

qr(r) is high for low

:

qr(r) is high for low ![]() and low for high

and low for high ![]() like for large phase angles.

A low surface albedo decreases the photons with multiple scatterings in the plane perpendicular to the limb, which are polarized parallel to the limb, thus enhancing the polarization in perpendicular direction. Therefore the limb polarization of a bright layer over a dark one can be even higher than for a semi-infinite atmosphere. This is discussed in more detail in Sect. 3.3.

like for large phase angles.

A low surface albedo decreases the photons with multiple scatterings in the plane perpendicular to the limb, which are polarized parallel to the limb, thus enhancing the polarization in perpendicular direction. Therefore the limb polarization of a bright layer over a dark one can be even higher than for a semi-infinite atmosphere. This is discussed in more detail in Sect. 3.3.

Radial polarized intensity:

The radial polarized intensity

For finite atmospheres, the limb polarization flux Qr(r)

depends only slightly on the surface albedo. Decreasing ![]() from 1 to 0 can increase Qr(r) at most

from 1 to 0 can increase Qr(r) at most

![]() for some models, while for most models Qr(r) is virtually constant. This is similar to the case for large phase angles.

for some models, while for most models Qr(r) is virtually constant. This is similar to the case for large phase angles.

3.2.1 Limb darkening and limb brightening vs. limb polarization

For a surface with a low albedo ![]() below a thin scattering layer the limb can be brighter than the disk

center, an effect that is generally called limb brightening. In principle this effect should be

called ``a central disk darkening'', because the low surface albedo

below a thin scattering layer the limb can be brighter than the disk

center, an effect that is generally called limb brightening. In principle this effect should be

called ``a central disk darkening'', because the low surface albedo ![]() does not brighten the limb.

It only absorbs more light in the center of the disk, where a higher fraction of

photons reach the absorbing surface because of their perpendicular

incidence when compared to the situation of grazing incidence at the limb.

Despite this fact we will retain the term ``limb brightening'' and consider the

limb brightness on a relative scale compared to the brightness of the

disk center.

does not brighten the limb.

It only absorbs more light in the center of the disk, where a higher fraction of

photons reach the absorbing surface because of their perpendicular

incidence when compared to the situation of grazing incidence at the limb.

Despite this fact we will retain the term ``limb brightening'' and consider the

limb brightness on a relative scale compared to the brightness of the

disk center.

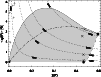

The limb darkening and limb brightening effect can be parametrized to a first order using the Minnaert law I(r) = Ir=0 (1-r2)k-1/2. The Minnaert parameter k determines the shape of the curve, k=1 corresponds to Lambert's law, k=0.5 to a flat intensity distribution I(r) = I0 and k < 0.5to limb brightening. The k parameter was determined by fitting Minnaert's law to all modeled intensity profiles, fixing the intensity at the center and excluding the outermost point where the formula diverges for k<0.5. With the exception of some cases mentioned below, most profiles can be fitted adequatly.

In Fig. 3 different examples of limb darkening and

limb brightening are shown along with the best fit of the Minnaert

law. Intensities are normalized to the central disk intensity.

There are two types of limb brightening curves. For very thin

atmospheres the maximal brightness is measured at the very edge of the

planet, while for a moderate optical depth the intensity raises slightly up to

a certain radius (e.g. 0.9 Rp) and then drops very close to the

limb. This second case cannot be fitted with the one-parameter

Minnaert law and is approximated here by a relatively flat curve

![]() .

.

|

Figure 3:

Radial intensity curves for different model parameters normalized to the central disk intensity, showing examples of limb darkening and limb brightening. The solid line is the calculated model and the dotted line the best fit with the Minnaert law. (a), (b) and (c) are for conservatively ( |

| Open with DEXTER | |

The limiting case of a conservative semi-infinite atmosphere yields a Minnaert parameter of

![]() .

For

.

For ![]() going towards 0, k tends to a flat intenstiy distribution k=0.5. For finite atmospheres there

is a strong dependence on the surface albedo

going towards 0, k tends to a flat intenstiy distribution k=0.5. For finite atmospheres there

is a strong dependence on the surface albedo ![]() .

For a strongly absorbing atmosphere over a bright surface (

.

For a strongly absorbing atmosphere over a bright surface (![]() low,

low,

![]() high) absorption is more likely towards the limb (k > 1), for a bright atmosphere

over a dark surface the opposite is true (k < 0.5). In the latter case the central disk intensity

is very low.

high) absorption is more likely towards the limb (k > 1), for a bright atmosphere

over a dark surface the opposite is true (k < 0.5). In the latter case the central disk intensity

is very low.

Similar to limb brightening, the limb polarization is also enhanced for a bright scattering layer over a dark surface. However, there are fundamental differences between these two effects. Limb polarization arises only for a polarizing process like Rayleigh scattering, while limb brightening occurs also for non-polarizing scattering processes like isotropic scattering. Additionally limb brightening is the stronger the thinner the upper bright layer, while limb polarization requires a sufficiently thick scattering layer above the dark surface. Finally, limb polarization can also occur for cases of limb darkening, e.g. the semi-infinite, conservative atmosphere. Therefore, the two effects provide complementary diagnostics of the vertical structure of the atmosphere.

3.3 Parameter study for quadrature phase

and opposition

and opposition

This section explores the full parameter space for

simple Rayleigh scattering atmospheres. We explore the parameter space by varying one of the three parameters ![]() ,

,

![]() and

and ![]() (cf. Sect. 2.2) while fixing the other two. We study the resulting intensity

(cf. Sect. 2.2) while fixing the other two. We study the resulting intensity

![]() ,

polarization fraction

,

polarization fraction

![]() ,

and polarized intensity

,

and polarized intensity

![]() (Figs. 4 to 6).

(Figs. 4 to 6).

The shapes of the model phase curves for the intensity ![]() ,

fractional polarization

,

fractional polarization ![]() ,

and polarized intensity

,

and polarized intensity ![]() look very similar for different

model parameters (see Fig. 2).

Therefore it is reasonable for a model parameter study to select

the results for the phase angle

look very similar for different

model parameters (see Fig. 2).

Therefore it is reasonable for a model parameter study to select

the results for the phase angle

![]() ,

considering them as representative (qualitatively) for all phase angles.

A phase angle

,

considering them as representative (qualitatively) for all phase angles.

A phase angle

![]() is ideal for extrasolar planets because all

planets will pass through this configuration twice during an orbit,

regardless of inclination.

is ideal for extrasolar planets because all

planets will pass through this configuration twice during an orbit,

regardless of inclination.

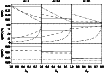

The same type of parameter study is presented for the limb

polarization of planets at opposition (

![]() ). For this we determine

disk-integrated (averaged) quantities for the intensity

and radial polarization from the model results (Figs. 7 to 9). The integrated intensity

). For this we determine

disk-integrated (averaged) quantities for the intensity

and radial polarization from the model results (Figs. 7 to 9). The integrated intensity

![]() is

equivalent to the geometric albedo,

is

equivalent to the geometric albedo,

![]() is the

intensity weighted average of the fractional polarization,

and

is the

intensity weighted average of the fractional polarization,

and

![]() the

integrated polarized intensity on the same scale as the integrated

intensity. These quantities are determined as described in

Sect. 2.1.

the

integrated polarized intensity on the same scale as the integrated

intensity. These quantities are determined as described in

Sect. 2.1.

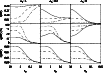

Figures 4 and 7 show the dependence

on the single scattering albedo ![]() .

For a given scattering

optical depth

.

For a given scattering

optical depth

![]() a reduction in

a reduction in ![]() is equivalent to an

enhancement of the absorption

is equivalent to an

enhancement of the absorption ![]() in the scattering layer.

Strong differences in

in the scattering layer.

Strong differences in

![]() occur in planetary atmospheres for

molecular absorptions (e.g. due to CH4 or H2O) inside and

outside the band while

occur in planetary atmospheres for

molecular absorptions (e.g. due to CH4 or H2O) inside and

outside the band while ![]() is essentially equal.

is essentially equal.

In Figs. 5 and 8 the Rayleigh

scattering optical depths from

![]() to 0.01 are plotted.

This illustrates quite well the possible

spectral dependence from short to long wavelengths (left to right)

for a Rayleigh scattering atmosphere. Since the Rayleigh

scattering cross sections is proportional to

to 0.01 are plotted.

This illustrates quite well the possible

spectral dependence from short to long wavelengths (left to right)

for a Rayleigh scattering atmosphere. Since the Rayleigh

scattering cross sections is proportional to

![]() ,

it is

possible that a planet has

,

it is

possible that a planet has

![]() at 400 nm and

at 400 nm and

![]() at 800 nm.

at 800 nm.

The effect of the albedo ![]() of the surface below the Rayleigh

scattering layer is shown in Figs. 6 and

9.

of the surface below the Rayleigh

scattering layer is shown in Figs. 6 and

9.

General results from Figs. 4 to 9 are:

- lowering the Rayleigh scattering albedo

always results in a lower intensity I, and lower

polarized intensity Q or Qr;

always results in a lower intensity I, and lower

polarized intensity Q or Qr;

- lowering the Rayleigh scattering albedo

results in a

higher polarization q at large phase angles. Contrary to this the

fractional limb polarization qr is reduced for lower

results in a

higher polarization q at large phase angles. Contrary to this the

fractional limb polarization qr is reduced for lower  ;

;

- lowering the Rayleigh scattering optical depth

produces a strong reduction in

the polarized intensity Q or Qr in the optically thin case

produces a strong reduction in

the polarized intensity Q or Qr in the optically thin case

and causes

essentially no change in Q or Qr in the optical thick case

and causes

essentially no change in Q or Qr in the optical thick case

;

;

- lowering the surface albedo

lowers the intensity I and

enhances the fractional polarization q or qr;

lowers the intensity I and

enhances the fractional polarization q or qr;

- changing the surface albedo

does not change the

polarized flux Q and hardly Qr.

does not change the

polarized flux Q and hardly Qr.

Another difference is the influence of

![]() on the

fractional polarization: q drops with

on the

fractional polarization: q drops with

![]() for bright non-polarizing

surfaces and increases for dark surfaces. It is more complicated at opposition: the limb polarization is highest if the dark ground eliminates photons that would otherwise scatter twice perpendicular to the limb, but the atmosphere is still thick

enough to produce many photons that escape having scattered twice parallel to the limb.

The maximum possible limb polarization

for bright non-polarizing

surfaces and increases for dark surfaces. It is more complicated at opposition: the limb polarization is highest if the dark ground eliminates photons that would otherwise scatter twice perpendicular to the limb, but the atmosphere is still thick

enough to produce many photons that escape having scattered twice parallel to the limb.

The maximum possible limb polarization

![]() % is reached for

% is reached for

![]() ,

,

![]() and

and ![]() .

.

|

Figure 4:

Intensity, polarization and polarized intensity at quadrature as function of single scattering albedo |

| Open with DEXTER | |

|

Figure 5:

Intensity, polarization and polarized intensity at quadrature as function of optical depth

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

|

Figure 6:

Intensity, polarization and polarized intensity at quadrature as function of surface albedo |

| Open with DEXTER | |

|

Figure 7:

Geometric albedo, disk-integrated radial polarization and polarized intensity at opposition as function of single scattering albedo |

| Open with DEXTER | |

|

Figure 8:

Geometric albedo, disk-integrated radial polarization and polarized intensity at opposition as function of optical depth

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

|

Figure 9:

Geometric albedo, disk-integrated radial polarization and polarized intensity at opposition as function of surface albedo |

| Open with DEXTER | |

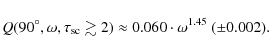

From the variation of

![]() shown in Fig. 5 it can

be seen that the polarized intensity

shown in Fig. 5 it can

be seen that the polarized intensity

![]() saturates above

saturates above

![]() .

Therefore

.

Therefore

![]() cannot probe deep atmospheric layers.

For the intensity and fractional polarization, an absorbing ground under a conservatively

scattering layer can be noticed even at

cannot probe deep atmospheric layers.

For the intensity and fractional polarization, an absorbing ground under a conservatively

scattering layer can be noticed even at

![]() .

.

The polarized intensity ![]() consists mostly of photons undergoing just one single Rayleigh scattering. Therefore, Q is not

changed by processes which happen deep in the atmosphere or by diffuse scattering on the surface. Q is only reduced if the number of single Rayleigh scatterings are reduced, e.g. because there is only a thin Rayleigh scattering layer or photons are efficiently absorbed high in the

atmosphere.

consists mostly of photons undergoing just one single Rayleigh scattering. Therefore, Q is not

changed by processes which happen deep in the atmosphere or by diffuse scattering on the surface. Q is only reduced if the number of single Rayleigh scatterings are reduced, e.g. because there is only a thin Rayleigh scattering layer or photons are efficiently absorbed high in the

atmosphere.

We can approximate the polarized intensity Q

by the following parametrization:

where ![]() and

and

![]() are fit parameters. Table 2 shows the best fit parameter

are fit parameters. Table 2 shows the best fit parameter

![]() ,

while

,

while

![]() and

and ![]() are listed in Table 1.

are listed in Table 1.

Table 2:

Best fit parameter

![]() for the parametrization of the polarized intensity Q (Eq. (5)).

for the parametrization of the polarized intensity Q (Eq. (5)).

For optically thick Rayleigh scattering atmospheres the polarized intensity

Q depends only on the single scattering albedo ![]() ,

and the parametrization reduces to:

,

and the parametrization reduces to:

At quadrature this is

|

(7) |

For the limb polarization flux

|

(8) |

4 Models beyond a Rayleigh scattering layer with a Lambert surface

The three parameter model grid discussed in Sect. 3.3 provides an overview on basic dependences of simple Rayleigh scattering models. In this section we describe a few results for particle scattering properties different from pure Rayleigh scattering, or models with more than one polarizing scattering layer.

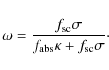

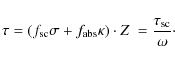

4.1 Atmospheres with Rayleigh and isotropic scattering

Pure Rayleigh scattering is a simplification for planetary atmospheres. Already for Rayleigh scattering by molecular hydrogen one needs to account for a weak depolarization effect, because the diatomic molecule is non-spherical. Another depolarization effect for scattered radiation occurs in dense gas because collisions with other particles take place frequently during the scattering process. In addition aerosols and dust particles can also be efficient scatterers in planetary atmospheres and the net scattering phase matrix differs from Rayleigh scattering and should be evaluated, e.g. by using the more general Mie theory.

A simple way for taking such effects into account in a first approximation is to use a linear combination of

the Rayleigh scattering and isotropic scattering phase matrices

| (9) |

where

Isotropic scattering is non-polarizing. If the scattering in the atmosphere is composed of both isotropic and Rayleigh scattering, then the fractional polarization and the polarized intensity are reduced by isotropic scattering, while the intensity is comparable (cf. Fig. 2).

Figure 10 shows the fractional

polarization

![]() at quadrature as a function of

at quadrature as a function of

![]() for a few representative cases. In the single scattering limit the

decrease is linear, the strongest deviation from a linear law is found for the semi-infinite

atmosphere because of the large amount of multiple scatterings. A similar behavior is found for other phase

angles, as well as for the radial limb polarization at opposition.

for a few representative cases. In the single scattering limit the

decrease is linear, the strongest deviation from a linear law is found for the semi-infinite

atmosphere because of the large amount of multiple scatterings. A similar behavior is found for other phase

angles, as well as for the radial limb polarization at opposition.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{11760f10.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/34/aa11760-09/Timg164.png) |

Figure 10:

Polarization of atmospheres with Rayleigh and isotropic scattering at 90 |

| Open with DEXTER | |

4.2 Forward-scattering phase functions

The high polarization of Jupiter's poles and the disk-integrated polarization of Titan (e.g. Tomasko & Smith 1982; Smith & Tomasko 1984) has been explained by the presence of a thick layer of polarizing haze particles. The derived single scattering properties indicate strong forward scattering and Rayleigh-like linear polarization with maximal polarization close to 100% at about 90![]() scattering angle. Particles that satisfy this behavior are thought to be aggregates that are non-spherical and with a projected area smaller than optical wavelengths (e.g. West 1991). We investigate the polarization properties of a planet with such a haze layer. The particle scattering properties are implemented as described in Braak et al. (2002) using a simple parametrized scattering matrix of the form

scattering angle. Particles that satisfy this behavior are thought to be aggregates that are non-spherical and with a projected area smaller than optical wavelengths (e.g. West 1991). We investigate the polarization properties of a planet with such a haze layer. The particle scattering properties are implemented as described in Braak et al. (2002) using a simple parametrized scattering matrix of the form

|

(10) |

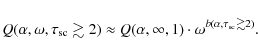

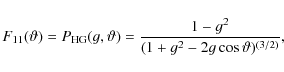

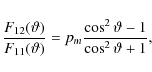

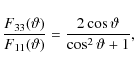

where

|

Figure 11:

Probability density function

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

Figure 11 shows the probability density function

![]() for

for

![]() in comparison with Rayleigh scattering. The probability density function for the scattering angle

in comparison with Rayleigh scattering. The probability density function for the scattering angle ![]() is the phase function

is the phase function

![]() weighted by

weighted by

![]() and normalized such that the integral over

and normalized such that the integral over

![]() equals 1. From this function the probability of the scattering angle within a certain interval is calculated by integrating

equals 1. From this function the probability of the scattering angle within a certain interval is calculated by integrating

![]() over this interval. One can see that for the haze models small scatttering angles (foward scattering) are greatly enhanced in comparison to Rayleigh scattering, while the probability for backscattering is much lower.

over this interval. One can see that for the haze models small scatttering angles (foward scattering) are greatly enhanced in comparison to Rayleigh scattering, while the probability for backscattering is much lower.

![]() describes the fractional polarization of the scattered radiation as a function of the scattering angle. For scattering on haze particles it can be similar to Rayleigh scattering scaled by a factor pm, the maximal single scattering polarization at

describes the fractional polarization of the scattered radiation as a function of the scattering angle. For scattering on haze particles it can be similar to Rayleigh scattering scaled by a factor pm, the maximal single scattering polarization at ![]() scattering angle. For a first qualitative analysis we set pm=1 which is an upper limit that may slightly overestimate the resulting polarization. The other matrix elements are identical to Rayleigh scattering.

scattering angle. For a first qualitative analysis we set pm=1 which is an upper limit that may slightly overestimate the resulting polarization. The other matrix elements are identical to Rayleigh scattering.

Figures 12 and 13 show the phase and radial dependences for the haze models similar to the Rayleigh scattering case in Sects. 3.1 and 3.2.

Intensity:

The phase curves of the haze models differ from the Rayleigh scattering models mainly at small phase angles. The geometric albedo is lower for the haze models because backscattering is strongly suppressed compared to Rayleigh scattering. This is already discussed by Dlugach & Yanovitskij (1974), who calculated albedos for semi-infinite hazy atmospheres. Our calculations result in slightly higher albedos because of the inclusion of polarization. At phase angles around 90 ![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=18.8cm,clip]{11760f12.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/34/aa11760-09/Timg175.png) |

Figure 12:

Phase dependence of the intensity I, fractional

polarization q and polarized intensity Q for a haze layer. Left: semi-infinite case

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=18.8cm,clip]{11760f13.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/34/aa11760-09/Timg176.png) |

Figure 13:

Radial dependence of the intensity I, radial

polarization qr and radial polarized intensity Qr at

opposition for a haze layer. Left: semi-infinite case

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

Polarization fraction:

The angle of maximal polarization is generally larger for the haze models than for Rayleigh scattering. In the semi-infinite conservative case it is

Polarized intensity:

The polarized intensity

4.3 Models with two polarizing layers

Up to now we have treated the region below the scattering layer

simply as a Lambert surface with an albedo ![]() ,

which

produces no polarization. In this section we explore model results for

two polarizing layers with different absorption properties, where the lower layer can be a

semi-infinite Rayleigh scattering atmosphere as described in

Sect. 3.1.

,

which

produces no polarization. In this section we explore model results for

two polarizing layers with different absorption properties, where the lower layer can be a

semi-infinite Rayleigh scattering atmosphere as described in

Sect. 3.1.

We focus on the question at what depth of the upper scattering layer

![]() the polarization properties of the underlying layer are washed

out by multiple scattering and are no longer recognizable in the reflected

radiation.

the polarization properties of the underlying layer are washed

out by multiple scattering and are no longer recognizable in the reflected

radiation.

Figure 14 compares the fractional polarization

![]() for three cases as a function of scattering optical depth of the upper layer,

for three cases as a function of scattering optical depth of the upper layer,

![]() :

a non-absorbing Rayleigh scattering layer above a semi-infinite, low albedo Rayleigh scattering atmosphere, the same scattering layer above a low albedo Lambertian surface, and an isotropic, non-polarizing scattering layer above the semi-infinite, low albedo Rayleigh scattering atmosphere.

:

a non-absorbing Rayleigh scattering layer above a semi-infinite, low albedo Rayleigh scattering atmosphere, the same scattering layer above a low albedo Lambertian surface, and an isotropic, non-polarizing scattering layer above the semi-infinite, low albedo Rayleigh scattering atmosphere.

The reflected polarization shows no dependence on the

polarization properties of the underlying surface for

deep scattering layers with

![]() .

There are too many multiple scatterings to preserve this type of information from

deeper layers in the escaping photons. An imprint from the

polarization of the lower layer becomes visible

for thin scattering layers with

.

There are too many multiple scatterings to preserve this type of information from

deeper layers in the escaping photons. An imprint from the

polarization of the lower layer becomes visible

for thin scattering layers with

![]() .

Particularly

well visible is the polarization dependence on

.

Particularly

well visible is the polarization dependence on

![]() for the

case where a polarizing layer is located below an isotropically

scattering layer. The polarizing lower layer only becomes apparent for

for the

case where a polarizing layer is located below an isotropically

scattering layer. The polarizing lower layer only becomes apparent for

![]() .

.

The same is true for the polarized intensity, because the reflected intensity only shows a very weak dependence on the phase function of the scattering layer. The effects are also very similar for the limb polarization at opposition.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{11760f14.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/34/aa11760-09/Timg186.png) |

Figure 14:

Fractional polarization q as function of

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

5 Wavelength dependence

The wavelength dependence of the reflected intensity and polarization of a model

planet can be calculated using wavelength dependent parameters

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

and

,

and

![]() or

or

![]() for single or double layer models respectively. These parameters must be derived from a model with

a given column density of scattering particles and mixing ratios for

Rayleigh-scattering and absorbing particles.

for single or double layer models respectively. These parameters must be derived from a model with

a given column density of scattering particles and mixing ratios for

Rayleigh-scattering and absorbing particles.

As an example we selected parameters which approximate very roughly an Uranus-like atmosphere

(e.g. Trafton 1976) considering only Rayleigh scattering by H2 and He and absorption

by CH4. In our first example we look at a homogeneous scattering layer with methane absorption

above a reflecting cloud layer with a wavelength independent surface albedo

![]() .

This is a strong simplification for Uranus because the methane mixing ratio is of order 100 lower in the stratosphere than in the troposphere (Sromovsky & Fry 2007). Nevertheless it is a useful example for discussing basic effects of the wavelength dependence.

.

This is a strong simplification for Uranus because the methane mixing ratio is of order 100 lower in the stratosphere than in the troposphere (Sromovsky & Fry 2007). Nevertheless it is a useful example for discussing basic effects of the wavelength dependence.

In a second example we make a first approximation for a methane mixing ratio that is varying with height, by having an upper layer of finite thickness without methane and a lower semi-infinite layer that includes methane.

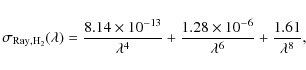

The Rayleigh scattering cross section of molecular hydrogen is given by Dalgarno & Williams (1962)

as

|

(15) |

where

The total Rayleigh scattering optical depth is

|

(16) |

where Zi is the column density and ni the index of refraction of the ith constituent

|

Figure 15:

Wavelength dependences of the model parameters total optical depth

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

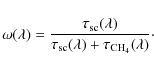

Because of the strong wavelength dependence of the Rayleigh scattering cross section,

![]() changes significantly from the UV to the near-IR (Fig. 15, top panel). Keeping

changes significantly from the UV to the near-IR (Fig. 15, top panel). Keeping ![]() and

and ![]() fixed (no absorber)

yields the intensity and polarization results given in Figs. 5 and 8 as function of

fixed (no absorber)

yields the intensity and polarization results given in Figs. 5 and 8 as function of

![]() ,

which are in this case equivalent to results as function of

,

which are in this case equivalent to results as function of ![]() .

.

The wavelength dependent single scattering albedo

![]() follows from the CH4

absorption optical depth

follows from the CH4

absorption optical depth

![]() and the Rayleigh scattering optical depth according to

and the Rayleigh scattering optical depth according to

|

(17) |

The absorption cross sections

The intensity

![]() ,

fractional polarization

,

fractional polarization

![]() ,

and polarized intensity

,

and polarized intensity