| Issue |

A&A

Volume 502, Number 3, August II 2009

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Page(s) | 913 - 927 | |

| Section | Stellar structure and evolution | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/200911857 | |

| Published online | 15 June 2009 | |

The puzzling dredge-up pattern in NGC 1978

M. T. Lederer1 - T. Lebzelter1 - S. Cristallo2 - O. Straniero2 - K. H. Hinkle3 - B. Aringer1,4

1 - University of Vienna, Department of Astronomy,

Türkenschanzstraße 17, 1180 Vienna, Austria

2 -

INAF, Osservatorio Astronomico di Collurania, 64100 Teramo, Italy

3 -

National Optical Astronomy Observatories![]() , PO Box 26732, Tucson, AZ 85726, USA

, PO Box 26732, Tucson, AZ 85726, USA

4 -

INAF, Osservatorio Astronomico di Padova, Vicolo dell'Osservatorio 5, 35122 Padova, Italy

Received 16 February 2009 / Accepted 2 June 2009

Abstract

Context. Low-mass stars are element factories that efficiently release their products in the final stages of their evolution by means of stellar winds. Since they are large in number, they contribute significantly to the cosmic matter cycle. To assess this contribution quantitatively, it is crucial to obtain a detailed picture of the stellar interior, particularly with regard to nucleosynthesis and mixing mechanisms.

Aims. We seek to benchmark stellar evolutionary models of low-mass stars. In particular, we measure the surface abundance of 12C in thermally pulsing AGB stars with well-known mass and metallicity, which can be used to infer information about the onset and efficiency of the third dredge-up.

Methods. We recorded high-resolution near-infrared spectra of AGB stars in the LMC cluster NGC 1978. The sample comprised both oxygen-rich and carbon-rich stars, and is well-constrained in terms of the stellar mass, metallicity, and age. We derived the C/O and 12C/ 13C ratio from the target spectra by a comparison to synthetic spectra. Then, we compared the outcomes of stellar evolutionary models with our measurements.

Results. The M stars in NGC 1978 show values of C/O and 12C/ 13C that can best be explained with moderate extra-mixing on the RGB coupled to a moderate oxygen enhancement in the chemical composition. These oxygen-rich stars do not seem to have undergone third dredge-up episodes (yet). The C stars show carbon-to-oxygen and carbon isotopic ratios consistent with the occurrence of the third dredge-up. We did not find S stars in this cluster. None of the theoretical schemes that we considered was able to reproduce the observations appropriately. Instead, we discuss some non-standard scenarios to explain the puzzling abundance pattern in NGC 1978.

Key words: stars: abundances - stars: AGB and post-AGB - stars: evolution

1 Introduction

Modelling the final phases in the evolution of a low-mass star is a demanding task. The stellar interior is a site of rich nucleosynthesis, particularly when the star evolves on the asymptotic giant branch (AGB). The freshly synthesised elements are carried to the outer layers of the star by means of the third dredge-up (TDU, for a review see Busso et al. 1999). The onset and efficiency of this mixing mechanism depends on the mass and the metallicity of the star. Various stellar evolution models developed in the recent past (e.g. Straniero et al. 1997; Karakas & Lattanzio 2007; Straniero et al. 2006; Stancliffe et al. 2004; Herwig 2000) agree on the theoretical picture of the TDU, but details are still subject to discussions. It is thus important to test the models against observations and to derive constraints to improve our understanding of the involved phenomena and related problems. AGB stars are tracers of intermediate-age stellar populations, which can only be modelled accurately when the evolution of the constituents is known. Moreover, evolved low-mass stars undergo strong mass loss in the late stages of their evolution. They enrich the interstellar medium with the products of nuclear burning and thus, as they are large in number, play a significant role in the cosmic matter cycle.

The primary indicator of TDU is a carbon surface

enhancement. An originally oxygen-rich star can be transformed

into a carbon star by an efficient dredge-up of

12C to the surface. The criterion to distinguish

between an oxygen-rich and a carbon-rich chemistry is the number

ratio of carbon to oxygen atoms,

![]() .

During the

thermally pulsing (TP) AGB phase, while the

.

During the

thermally pulsing (TP) AGB phase, while the

![]() ratio is

constantly rising as a consequence of the TDU,

there are mechanisms that may counteract

the increase in the carbon isotopic ratio

12C/ 13C. The radiative gap between the

convective envelope and the hydrogen burning shell can be bridged

by a slow mixing mechanism

(cf. Nollett et al. 2003; Wasserburg et al. 1995). In this

way, 12C and isotopes of other elements are fed back

to nuclear processing. The physical origin of this

phenomenon is still not known, which is another argument to

establish observational data in order to benchmark theoretical

predictions.

ratio is

constantly rising as a consequence of the TDU,

there are mechanisms that may counteract

the increase in the carbon isotopic ratio

12C/ 13C. The radiative gap between the

convective envelope and the hydrogen burning shell can be bridged

by a slow mixing mechanism

(cf. Nollett et al. 2003; Wasserburg et al. 1995). In this

way, 12C and isotopes of other elements are fed back

to nuclear processing. The physical origin of this

phenomenon is still not known, which is another argument to

establish observational data in order to benchmark theoretical

predictions.

Measurements of the carbon abundance and the carbon isotopic ratio have been done for a few bright field AGB stars (Smith & Lambert 1990; Lambert et al. 1986; Harris et al. 1987). The direct comparison of the values inferred from field star observations to evolutionary models is complicated by the fact that luminosity and mass of those targets can be determined only inaccurately, while both quantities are crucial input parameters for the models. A strategy to circumvent this problem is to observe AGB stars in globular clusters (GC). They provide a rather homogeneous sample with respect to distance, age, mass, and metallicity. Admittedly, this simplistic picture is slowly disintegrating. There is evidence that globular clusters often harbour more than one population with abundance variations among the constituents (Piotto et al. 2007; Renzini 2008; Mackey & Broby Nielsen 2007). The parameters like mass and metallicity are, however, still much better constrained than for field stars. For our purpose, i.e. investigating the abundance variations due to the TDU, the old Milky Way globular clusters are not well suited. The AGB stars of the current generation have an envelope mass too low for TDU to occur, while more massive stars have evolved beyond the AGB phase. The intermediate-age globular clusters in the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC) serve our needs better. We started with an investigation of the AGB stars in NGC 1846 (Lebzelter et al. 2008, henceforth Paper I) and indeed demonstrated the abundance variation along the AGB due to the TDU.

In this paper, we pursue this idea and study the AGB stars in the

LMC globular cluster NGC 1978, deriving

![]() and

12C/ 13C ratios. We give an overview of

previous studies of this cluster and our observations in

Sect. 2. Details about the data analysis are

given in Sect. 3. In

Sect. 3.4 we describe the

evolutionary models we use for a comparison to our

observational results. The results follow in

Sect. 4. We discuss our findings in

Sect. 5, giving scenarios on how to interpret

the puzzling case of NGC 1978 before we conclude in

Sect. 6.

and

12C/ 13C ratios. We give an overview of

previous studies of this cluster and our observations in

Sect. 2. Details about the data analysis are

given in Sect. 3. In

Sect. 3.4 we describe the

evolutionary models we use for a comparison to our

observational results. The results follow in

Sect. 4. We discuss our findings in

Sect. 5, giving scenarios on how to interpret

the puzzling case of NGC 1978 before we conclude in

Sect. 6.

2 Observations

2.1 The target cluster: NGC 1978

The globular cluster NGC 1978 is a member of the intermediate-age (

Mucciarelli et al. (2007a) derived the cluster age, distance

modulus, and turn-off mass by fitting isochrones to the cluster

colour-magnitude diagram (CMD). The resulting values are

![]() ,

(m-M)0=18.50 and

,

(m-M)0=18.50 and

![]() ,

respectively, for the best

fit found when using isochrones from the Pisa Evolutionary

Library (PEL, Castellani et al. 2003). When adopting other

isochrones with different overshooting prescriptions, the

parameters vary so that one could also derive a somewhat lower

turn-off mass (

,

respectively, for the best

fit found when using isochrones from the Pisa Evolutionary

Library (PEL, Castellani et al. 2003). When adopting other

isochrones with different overshooting prescriptions, the

parameters vary so that one could also derive a somewhat lower

turn-off mass (

![]() ), a lower

distance modulus (

(m-M)0=18.38), and a cluster age from 1.7 to

), a lower

distance modulus (

(m-M)0=18.38), and a cluster age from 1.7 to

![]() .

.

The various radial velocity measurements quoted in the literature

widely agree within the error bars, e.g.

Olszewski et al. (1991) and Schommer et al. (1992) derived

![]() whereas Ferraro et al. (2006) determined a mean heliocentric

velocity of NGC 1978 of

whereas Ferraro et al. (2006) determined a mean heliocentric

velocity of NGC 1978 of

![]() and

with a velocity dispersion

and

with a velocity dispersion

![]() .

.

NGC 1978 harbours a number of red giant stars (Lloyd Evans 1980) some of which are known to be carbon stars (Frogel et al. 1990). The easiest explanation for such an occurrence is that these C stars are AGB stars undergoing the third dredge-up or, alternatively, that they underwent mass accretion from an old AGB companion, which subsequently evolved into a white dwarf. More exotic explanations will be discussed in Sect. 5.2.

2.2 Spectroscopy

Table 1: NGC 1978 targets and log of observations (LE stands for Lloyd Evans 1980).

We recorded high-resolution near-infrared spectra of 12 AGB stars in the LMC globular cluster NGC 1978. Ten stars from our target list were already identified by Lloyd Evans (1980) as red giant stars (and are tagged LE in this work) but largely without information about the spectral type. Frogel et al. (1990) listed a number of AGB stars in NGC 1978, comprising also the stars from LE, and gave information about the spectral type, the cluster membership, and near-infrared photometry data. Based on this information, we selected ten targets that could be observed with the Phoenix spectrograph mounted at the Gemini South Telescope (Hinkle et al. 2003,1998) with reasonable exposure times. Additionally, we constructed a colour-magnitude diagram from Two Micron All Sky Survey (2MASS, Skrutskie et al. 2006) data and picked two more stars that, judging from their K magnitude and (J-K) colour index, are also located on the AGB of NGC 1978 (stars A and B). Details about the observation targets together with the observing log are given in Table 1. The distribution of all the targets within the cluster is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Our observing programme required observations at two

different wavelengths, one in the H band and one in the K band. For

this purpose, we utilised the Phoenix order sorting filters H6420

and K4220. However, poor weather conditions in the last of the 4 observing nights prohibited to record H-band spectra for the

targets LE2 and LE7. For the star LE9, we obtained spectra from

queue mode observations in the semester 2008A. The exact

wavelength settings are similar to the ones described in

Lebzelter et al. (2008), i.e. in the K band our spectra run

approximately from 23 580 to

![]() .

In the H band (

.

In the H band (

![]() ), the spectral region observed was shifted to

slightly higher wavelengths to cover a larger part of the CO 3-0

band head at

), the spectral region observed was shifted to

slightly higher wavelengths to cover a larger part of the CO 3-0

band head at

![]() .

The slit width was set to

.

The slit width was set to

![]() (the widest slit) which resulted

in a spectral resolution of

(the widest slit) which resulted

in a spectral resolution of

![]() .

.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm]{11857f01.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/30/aa11857-09/Timg39.png) |

Figure 1:

Distribution of observed targets in the cluster NGC 1978. The picture was acquired from the 2MASS catalogue using Aladin (Bonnarel et al. 2000). Numbers refer to the nomenclature of Lloyd Evans (1980). The additional targets A and B were chosen according to their position in the 2MASS colour-magnitude diagram. The stars A, 4, 5, 8, 9, and 10 possess an oxygen-rich atmosphere while B, 1, 2, 3, 6, and 7 are carbon stars. The cluster is elongated and its major axis stretches roughly from south-east to north-west. The displayed sky region is

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

The total integration time per target and wavelength setting

ranged between 20 (LE3) and 120 (LE9) minutes. For each target we observed

at two or three different positions along the slit. Each night, we also recorded a

spectrum of a hot star without intrinsic lines in the respective

wavelength regions in order to correct the spectra of our

programme stars for telluric lines. The resulting signal-to-noise

was from 50 to above 100 per resolution element (![]() 4 pixels).

See Table 1 for details.

4 pixels).

See Table 1 for details.

2.3 Data reduction

The data reduction procedure was carried out as described at length for example in Smith et al. (2002) and in the Phoenix data reduction IRAF tutorial

To correct the AGB star spectra for telluric lines, we acquired the

spectrum of an early type star without intrinsic lines. The

telluric absorption features were removed using the IRAF task

telluric in the K band. The H-band spectra are almost free of

telluric lines, they were, however, also processed in the same way

to remove the fringing. In the H band, we did the wavelength

calibration for a K-type radial velocity standard (HD 5457,

![]() ,

Wilson 1953)

recorded alongside with the programme stars. Using the Arcturus

atlas from Hinkle et al. (1995), we identified several

features (OH, Fe, Ti, Si lines) in the spectrum and derived a

dispersion solution. The relation was then applied to the

remaining spectra. This procedure allowed us to derive radial

velocities from the H-band spectra. For the K-band spectra we did

a direct calibration using the CO lines in the spectrum of an

M-type target. That solution was then also applied to the carbon-star spectra.

,

Wilson 1953)

recorded alongside with the programme stars. Using the Arcturus

atlas from Hinkle et al. (1995), we identified several

features (OH, Fe, Ti, Si lines) in the spectrum and derived a

dispersion solution. The relation was then applied to the

remaining spectra. This procedure allowed us to derive radial

velocities from the H-band spectra. For the K-band spectra we did

a direct calibration using the CO lines in the spectrum of an

M-type target. That solution was then also applied to the carbon-star spectra.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=18cm]{11857f02.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/30/aa11857-09/Timg42.png) |

Figure 2:

Overview about observations: H-band spectra are shown on the left side, K-band spectra on the right. The spectra are ordered by increasing infrared colour

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

3 Data analysis

3.1 Contents of the observed wavelength ranges

The wavelength ranges were chosen such that from the H band spectra we could derive the stellar parameters and the C/O ratio. Subsequently, we inferred the carbon isotopic ratio 12C/ 13C from the K band. In practice, the parameters are tuned iteratively. The region in the H band is widely used in the literature (e.g. McSaveney et al. 2007; Yong et al. 2008; Smith et al. 2002) to derive oxygen abundances from the contained OH lines. From the relative change of those features in comparison to the band head from the 12C 16O 3-0 vibration transition, it is possible to determine the C/O ratio in the stellar atmosphere. A weak CN line and a few metal lines (Fe, Ti, Si) aid in the pinning down of the parameters, especially the effective temperature.

The K-band spectra comprise a number of CO lines from first

overtone (

![]() )

transitions. Beside features from the

main isotopomer 12C 16O, we also find

some 13C 16O lines in this region. We

derived the carbon isotopic ratio by fitting these lines. Apart

from the CO lines, there is also a single HF line blended with a

13CO feature.

)

transitions. Beside features from the

main isotopomer 12C 16O, we also find

some 13C 16O lines in this region. We

derived the carbon isotopic ratio by fitting these lines. Apart

from the CO lines, there is also a single HF line blended with a

13CO feature.

In Fig. 2, we give an overview about our observations. For the oxygen-rich stars, the key features in the H band are marked. In the K band, we indicate the position of the 13CO lines. The selection of the wavelength ranges was driven by the oxygen-rich case. From Fig. 2 it is obvious that the regions are not well suited for the analysis of carbon-star spectra. Both H- and K-band spectra are crowded with features from the CN and C2 molecules, occurring in addition to the CO lines. The polyatomic molecules C2H2, HCN, and also C3contribute to the opacity by means of many weak lines that form a pseudo-continuum (see Sect. 3.3.2). The major part is due to C2H2 absorption that increases with decreasing effective temperature. In the H band, the CO band head is strongly affected by neighbouring features. Generally speaking, there is not a single unblended line in the carbon-rich case. The situation in the K band, however, is not that bad. The 12CO lines are still visible, although blended with CN features, but there are only a few C2lines. The pseudo-continuum is essentially all due to C2H2, contributions from other molecules are negligible.

3.2 Synthetic spectra

We compare our observations with synthetic spectra based on model atmospheres that were calculated with the COMARCS code (details will be given in a forthcoming paper by Aringer et al. 2009). COMARCS is a modified version of the MARCS code (originating from Jørgensen et al. 1992; Gustafsson et al. 1975; recently extensively described by Gustafsson et al. 2008). In the model calculations, we deduced the temperature and, accordingly, pressure stratification assuming a spherical configuration in hydrostatic and local thermodynamic equilibrium (LTE). For stars showing only a small variability, LTE is a reasonable approximation. Possible deviations from LTE have a smaller influence on the abundance determination than large deviations from the hydrostatic equilibrium (see for example Johnson 1994 for a discussion of non-LTE effects in cool star atmospheres). In the evaluation of the chemical equilibrium, which is a consequence of LTE, we take all relevant opacity sources into account in both model calculation and spectral synthesis. In the oxygen-rich case H2O, TiO, CO, and CN are major opacity contributors, while HCN, C2H2, C2 (and others) are important in the carbon-rich case. The opacity coefficients utilised by COMARCS are calculated with the COMA code (Aringer et al. 2009; Aringer 2000). The atomic line data were taken from VALD (Kupka et al. 2000), an overview of the molecular line lists used with all the sources documented can be found in Lederer & Aringer (2009). Model atmospheres and synthetic spectra that were calculated following the method outlined above have been shown to describe the spectra of cool giant stars appropriately (e.g. Loidl et al. 2001; Aringer et al. 2002). We applied the same procedure successfully in Paper I for our analysis of the AGB stars in the LMC cluster NGC 1846.

From the parameters that determine an atmospheric model, we held

the mass and the metallicity constant. The respective values are

![]() and

and

![]() ,

and

were taken from the literature (see Sect. 1). In the model

calculations, the microturbulent velocity was set to

,

and

were taken from the literature (see Sect. 1). In the model

calculations, the microturbulent velocity was set to

![]() ,

which is in the range that is

found for atmospheres of low-mass giants

(e.g. Gautschy-Loidl et al. 2004; Aringer et al. 2002; Smith et al. 2002).

By varying the remaining parameters effective temperature

,

which is in the range that is

found for atmospheres of low-mass giants

(e.g. Gautschy-Loidl et al. 2004; Aringer et al. 2002; Smith et al. 2002).

By varying the remaining parameters effective temperature

![]() ,

logarithm of the surface gravity

,

logarithm of the surface gravity

![]() ,

and carbon-to-oxygen ratio (C/O),

we constructed a grid of model atmospheres and spectra. This was

done such that we cover the

,

and carbon-to-oxygen ratio (C/O),

we constructed a grid of model atmospheres and spectra. This was

done such that we cover the

![]() and

and ![]() range resulting from

colour-temperature relations and bolometric corrections

applied to our sample stars. The step

size in effective temperature was set to

range resulting from

colour-temperature relations and bolometric corrections

applied to our sample stars. The step

size in effective temperature was set to

![]() ,

whilst

the surface gravity was altered in steps of 0.25 on a

logarithmic scale, i.e. for

,

whilst

the surface gravity was altered in steps of 0.25 on a

logarithmic scale, i.e. for ![]() ,

ranging from 0.0 to +0.5. For some carbon stars in our sample we got

,

ranging from 0.0 to +0.5. For some carbon stars in our sample we got

![]() from the colour transformations and the adopted mass. The spectral

features used in the analysis show only a minor dependence on this

parameter thus we fixed

from the colour transformations and the adopted mass. The spectral

features used in the analysis show only a minor dependence on this

parameter thus we fixed

![]() in the analysis of the carbon

stars. In this way we also avoid convergence problems for the

atmospheric models.

in the analysis of the carbon

stars. In this way we also avoid convergence problems for the

atmospheric models.

The element composition is scaled solar

(Grevesse & Noels 1993), but we assumed an

oxygen over-abundance of

![]() motivated by the

results of our work on NGC 1846 (Paper I) and by the paper of

Hill et al. (2000). We altered the C/O ratio in steps

of 0.05 in the oxygen-rich case and 0.10 in the carbon-rich case.

This was done by changing the carbon abundance while leaving the

other abundances untouched.

motivated by the

results of our work on NGC 1846 (Paper I) and by the paper of

Hill et al. (2000). We altered the C/O ratio in steps

of 0.05 in the oxygen-rich case and 0.10 in the carbon-rich case.

This was done by changing the carbon abundance while leaving the

other abundances untouched.

The synthetic spectra cover a wavelength range of

![]() (

(

![]() )

in

the H band and of

)

in

the H band and of

![]() (

(

![]() )

in the K band. The spectra were

first calculated with a resolution of

)

in the K band. The spectra were

first calculated with a resolution of

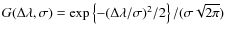

![]() and then convolved with a

Gaussian

and then convolved with a

Gaussian![]() to match the resolution of our observed spectra

(R=50 000). By applying another convolution with a Gaussian

profile we took the macroturbulent velocity into account. To

determine the carbon isotopic ratio

12C/ 13C (which is about 89.9 in the

Sun according to Anders & Grevesse 1989), we altered this

parameter as well. The carbon isotopic ratio has virtually no

effect on the model structure and was consequently only considered

in the spectral synthesis calculations.

to match the resolution of our observed spectra

(R=50 000). By applying another convolution with a Gaussian

profile we took the macroturbulent velocity into account. To

determine the carbon isotopic ratio

12C/ 13C (which is about 89.9 in the

Sun according to Anders & Grevesse 1989), we altered this

parameter as well. The carbon isotopic ratio has virtually no

effect on the model structure and was consequently only considered

in the spectral synthesis calculations.

3.3 Determination of abundance ratios

We derive the effective temperature

For each target we fit the parameters in a two-step

process. The idea is to fit the spectral ranges at once rather

than tuning individual abundances (except for carbon) to fit

single spectral features. From the H band, we could in this way

constrain the stellar parameters (

![]() and

and ![]() )

and the C/O ratio. Variations in

)

and the C/O ratio. Variations in ![]() had the smallest effect

on the synthetic spectra. A small uncertainty in the stellar mass

or radius estimate has thus only a minor influence on the derived

abundance ratios. Using the parameters as obtained from the H band, we then calculated

K-band spectra with a varying

12C/ 13C ratio to determine this

parameter as well. The carbon isotopic ratio does not influence

the appearance of the H band spectrum significantly, as was

verified by test calculations.

had the smallest effect

on the synthetic spectra. A small uncertainty in the stellar mass

or radius estimate has thus only a minor influence on the derived

abundance ratios. Using the parameters as obtained from the H band, we then calculated

K-band spectra with a varying

12C/ 13C ratio to determine this

parameter as well. The carbon isotopic ratio does not influence

the appearance of the H band spectrum significantly, as was

verified by test calculations.

To match the shape of the spectral features we also had to assume

a macroturbulent velocity which reduces the effective resolution

of the spectra. This artificial broadening includes the

instrumental profile, but it is also used to imitate at least partly

the dynamical effects in the stellar atmosphere, which become

increasingly important for carbon stars. This is also why the

adopted values were generally lower for the

oxygen-rich targets: they were fitted by applying a macroturbulent

velocity of

![]() .

The carbon

stars displayed a stronger broadening of the features (cf.

Fig. 2). We needed values of

.

The carbon

stars displayed a stronger broadening of the features (cf.

Fig. 2). We needed values of

![]() and even

and even

![]() (LE6) to fit the spectra

(compare also de Laverny et al. 2006 who find comparable

values in their study). We consistently applied the same value for

the H and the K band.

(LE6) to fit the spectra

(compare also de Laverny et al. 2006 who find comparable

values in their study). We consistently applied the same value for

the H and the K band.

We tried to objectify the search for the best fit by applying a

least-square fitting method. Although we were in this way able to

narrow down the possible solutions to a few candidate spectra

quickly, the final decision about our best fit was done by visual

inspection. The reason is that spectral features with a false

strength or position (both due to imperfect line data)

in the synthetic spectrum, or spectral

regions with a high noise level dominate ![]() and confuse an

automatic minimisation algorithm. As the last step in the fitting

procedure is done by eye, we assign a formal error to the derived

parameters. In the case that the best fit parameters lie

in-between our grid values, we quote the arithmetic mean of the

candidate models as our fit result. The error bars were estimated

from the range of parameters of the model spectra that still gave

an acceptable fit.

and confuse an

automatic minimisation algorithm. As the last step in the fitting

procedure is done by eye, we assign a formal error to the derived

parameters. In the case that the best fit parameters lie

in-between our grid values, we quote the arithmetic mean of the

candidate models as our fit result. The error bars were estimated

from the range of parameters of the model spectra that still gave

an acceptable fit.

The formal errors for the

derived C/O and 12C/ 13C ratios

given in Table 3 compare well with

the uncertainties found by some basic error estimates, as will be shown

in the following. Therefore the quintessence of the discussion in

Sect. 5 is on a sound footing.

We consider typical uncertainties in the stellar

parameters and investigate the influence on the derived abundance

ratios. The correlations between the stellar parameters and possible systematic errors from the model syntheses have not been taken into account in the error analysis.

For the oxygen-rich case, we start from a baseline model with

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

and

,

and

![]() .

Changes of

.

Changes of

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

and

,

and

![]() correspond to changes

in

correspond to changes

in

![]() of 0.02, 0.03, and 0.01, respectively

of 0.02, 0.03, and 0.01, respectively![]() .

Summed in quadrature this results in a typical total uncertainty of 0.04 for the C/O ratio of our M-type targets. The same exercise

for the carbon isotopic ratio results in

.

Summed in quadrature this results in a typical total uncertainty of 0.04 for the C/O ratio of our M-type targets. The same exercise

for the carbon isotopic ratio results in

![]() of 2, 2, and 3 (parameter dependence as above), and

thus a total uncertainty of 4. Concerning the carbon-rich case, we start from a carbon-rich model with parameters

of 2, 2, and 3 (parameter dependence as above), and

thus a total uncertainty of 4. Concerning the carbon-rich case, we start from a carbon-rich model with parameters

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

,

![]() and vary the parameters as described above. This leads to a total

and vary the parameters as described above. This leads to a total

![]() .

For the carbon isotopic ratio we find

.

For the carbon isotopic ratio we find

![]() .

.

A considerable part of our discussion will be concerned with the

12C/ 13C ratios of our targets.

Since the derived isotopic ratios depend on the

parameters of the 13CO lines (taken from the

list of Goorvitch & Chackerian 1994, see also Appendix A), we want to assess

possible systematic errors in the line strengths. In the case that

the predicted line strengths in the list are too large, one would

have to increase 12C/ 13C

(equivalent to a decrease of the 13C abundance) in

order to fit a 13CO feature compared with the case

where the predicted strengths are correct. The actual

12C/ 13C ratio would then be lower than the derived value.

For some oxygen-rich stars in our sample we get carbon isotopic ratios that

are close to the value of the CN cycle equilibrium (4-5). A

necessary further reduction is thus not very likely. If the

theoretical line strengths are too low, the above argument is

reversed. One would assume a lower

12C/ 13C ratio to fit the 13CO

features, which means that one would underestimate the actual isotopic

ratio. Since we, of course, use the same line list for the analysis of

both M and C stars, this would shift up the

12C/ 13C for all targets in

Figs. 7, 8, and 9.

Similar to a ![]() uncertainty,

the values for the carbon stars

would be stronger affected. Hence, underestimated

13CO line strengths would relax the necessity of

efficient additional mixing processes on the RGB as discussed

in Sect. 5.

uncertainty,

the values for the carbon stars

would be stronger affected. Hence, underestimated

13CO line strengths would relax the necessity of

efficient additional mixing processes on the RGB as discussed

in Sect. 5.

In the next section, we discuss M and C stars separately. The features contained in the spectra depend on the chemistry regime and some issues cannot be discussed in a general way.

3.3.1 M-type stars

In the search for a good fit we took advantage of the way features

react to parameter changes. An increasing temperature weakens all

features in the H band. The OH/Fe blend at approximately

![]() is a good temperature indicator. The two

neighbouring OH lines and the CO band head react less on

temperature changes.

The remaining lines show only a weak

dependence on

is a good temperature indicator. The two

neighbouring OH lines and the CO band head react less on

temperature changes.

The remaining lines show only a weak

dependence on

![]() .

The K band is largely insensitive

to temperature changes, only the 13CO lines show a

weak dependence on temperature which adds to the uncertainty in

determining the isotopic ratio. The only feature strongly reacting

when altering

.

The K band is largely insensitive

to temperature changes, only the 13CO lines show a

weak dependence on temperature which adds to the uncertainty in

determining the isotopic ratio. The only feature strongly reacting

when altering

![]() in the model calculations

is the blend including the HF line, its strength decreases when

the temperature is increased.

in the model calculations

is the blend including the HF line, its strength decreases when

the temperature is increased.

An increase in C/O enhances the strength of the CO band head and causes stronger CN lines, while the OH lines get slightly weaker, especially the feature blended with an Fe line. Lowering C/O decreases the strength of the CO features in the K band.

The CO band head is also sensitive to changes in ![]() ,

while

the other features practically are not.

Changes in the surface gravity also

affect the measured carbon isotopic ratios (see Sect. 3.3).

Two of the 13CO lines in the spectra of the oxygen-rich

stars are unblended ( 13CO 2-0 R18 and

13CO 2-0 R19). Blended 13CO features

were used to check the isotopic ratio derived from the clean

lines.

,

while

the other features practically are not.

Changes in the surface gravity also

affect the measured carbon isotopic ratios (see Sect. 3.3).

Two of the 13CO lines in the spectra of the oxygen-rich

stars are unblended ( 13CO 2-0 R18 and

13CO 2-0 R19). Blended 13CO features

were used to check the isotopic ratio derived from the clean

lines.

The continuum is well defined in the oxygen-rich case. We utilised the least-square method in the process of finding the best fit.

3.3.2 C-type stars

Several things make the fitting of carbon stars more difficult compared with the case of M-type stars. Foremost, the quality of the line data for the molecules appearing in the carbon-rich case hampers the qualitative analysis profoundly. For CN, C3, and C2H2 we used the SCAN database (Jørgensen 1997). The line positions in the computed CN list are not accurate enough for modelling high-resolution spectra. With the help of measured line positions for CN that were compiled by Davis et al. (2005), we were able to correct the wavelengths of the strongest lines. While the results were satisfying in the oxygen-rich case, in the carbon-star spectra many additional weak lines show up that could not be corrected. The case of C2 (we used the line data from Querci et al. 1974), producing a wealth of spectral features, is even more problematic: no observed reference line list is available for this molecule, so both line positions and strengths are subject to large uncertainties. We corrected the line list manually by removing strong features that did not appear in any of our observations. Several features were shifted to other wavelengths where it was evident from the observations that the lines are at the wrong position. Unlike for M stars, the H-band spectra of carbon stars are also affected by the carbon isotopic ratio. Lines from 13C 12C or 13C 14N are important in some blends, however, the quality of the line data for these features could not be assessed for the above described reasons.

The molecules C2H2 and C3 are incorporated into our

calculations via low-resolution opacity sampling data. The

absorption thus becomes manifest as a pseudo-continuum in the

spectra. A possible occurrence of strong lines or regions with

particularly low absorption cannot be reproduced with this

approach. The pseudo-continuum level reacts sensitively to

temperature changes. In general, an increase in

![]() reduces the feature strength. The relative changes of different

line strength can be used to constrain the temperature range.

The lower the temperature gets, the higher the contribution of

C2H2 and C3 becomes, whereas C2H2 dominates the

absorption. An increase in the C/O ratio has the same effect.

The implications for abundance determination of the ill-defined

continuum in carbon stars is discussed in detail in Paper I.

We want to stress here the consequences for the

reduces the feature strength. The relative changes of different

line strength can be used to constrain the temperature range.

The lower the temperature gets, the higher the contribution of

C2H2 and C3 becomes, whereas C2H2 dominates the

absorption. An increase in the C/O ratio has the same effect.

The implications for abundance determination of the ill-defined

continuum in carbon stars is discussed in detail in Paper I.

We want to stress here the consequences for the ![]() method.

The absorption in the pseudo-continuum varies with temperature requiring scaling of

the observed spectrum before a comparison. Due to this scaling the

value of

method.

The absorption in the pseudo-continuum varies with temperature requiring scaling of

the observed spectrum before a comparison. Due to this scaling the

value of ![]() changes in the same manner, so that model

spectra with lower effective temperatures (causing a lower flux

level due to an increased pseudo-continuum) always result in a

lower

changes in the same manner, so that model

spectra with lower effective temperatures (causing a lower flux

level due to an increased pseudo-continuum) always result in a

lower ![]() ,

pretending to fit the observations better. This is

of course an artificial effect, and thus we cannot rely on the

least-square method as objective criterion.

,

pretending to fit the observations better. This is

of course an artificial effect, and thus we cannot rely on the

least-square method as objective criterion.

A change in ![]() has only small effects on the carbon-star

spectra. A higher surface gravity produces a higher

pseudo-continuum in the K band.

In general

has only small effects on the carbon-star

spectra. A higher surface gravity produces a higher

pseudo-continuum in the K band.

In general ![]() only marginally affects the spectral lines.

However, in the determination of 12C/ 13C

the uncertainty in

only marginally affects the spectral lines.

However, in the determination of 12C/ 13C

the uncertainty in ![]() has to be taken into account.

In the K band, all

13CO lines are blended with other features. The

carbon isotopic ratio is already so high that the strengths of the

13CO lines have become rather insensitive to changes

in this parameter. As a consequence, even the small uncertainties

in

has to be taken into account.

In the K band, all

13CO lines are blended with other features. The

carbon isotopic ratio is already so high that the strengths of the

13CO lines have become rather insensitive to changes

in this parameter. As a consequence, even the small uncertainties

in ![]() correspond to large changes in the isotopic ratio,

which adds to the errors.

correspond to large changes in the isotopic ratio,

which adds to the errors.

Variations of the C/O ratio have the strongest impact on the H-band spectra when C/O is slightly above 1. The strength of the CO band head rapidly drops when C/O is increased to 1.3, approximately. Then a saturation sets in and the strength of the CO band head varies slowly with C/O. This behaviour and strong CN features sitting in the band head hamper an accurate C/O determination. The lines of C2 and CN increase in strength when C/O rises, both in the H and the K band. The CO lines in the K band decrease in strength for higher values of C/O. The changes are, however, small and do not allow for a determination of the C/O ratio from the K-band spectra alone.

Figure 3 is, as an example, a fit for the

star B, which is a carbon star. The star has an effective

temperature of about

![]() (see also

Table 3 for the other fit parameters). The

pseudo-continuum contribution is relatively weak, although there

are almost no line-free regions in both spectral bands. A number

of features is successfully reproduced by our models, the

deviations in other regions are most probably due to uncertain

line data.

(see also

Table 3 for the other fit parameters). The

pseudo-continuum contribution is relatively weak, although there

are almost no line-free regions in both spectral bands. A number

of features is successfully reproduced by our models, the

deviations in other regions are most probably due to uncertain

line data.

To measure the 12C/ 13C ratio in the carbon-star

spectra, we utilised the 13CO lines at 23 579.9,

23 590.2, and

![]() (the leftmost lines indicated in the

right panel of Fig. 2). In the vicinity of the other

13CO lines, there are obviously absorption features missing

in our synthetic spectra (see Fig. 3). We cannot rule

out that our analysis of a limited number of line blends could introduce

a systematic error in the inferred carbon isotopic ratios. Therefore, we

emphasise that it would be worthwhile to reassess the isotopic ratios in other

wavelength regions, particulary in the light of the discussion in

Sect. 5.

(the leftmost lines indicated in the

right panel of Fig. 2). In the vicinity of the other

13CO lines, there are obviously absorption features missing

in our synthetic spectra (see Fig. 3). We cannot rule

out that our analysis of a limited number of line blends could introduce

a systematic error in the inferred carbon isotopic ratios. Therefore, we

emphasise that it would be worthwhile to reassess the isotopic ratios in other

wavelength regions, particulary in the light of the discussion in

Sect. 5.

We also identified four low-excitation 12CO 2-0 lines

in the K band (see also Fig. 2).

According to Hinkle et al. (1982), low-excitation lines form

in the outer atmospheric layers, opposite to high-excitation lines

that show characteristics similar to second overtone transitions

(

![]() ). In all the carbon-star spectra, these lines could

not be fitted with our synthetic spectra. The calculations

underestimate the line strength, suggesting that the extended

atmospheres of luminous carbon stars are not well reproduced by

our hydrostatic models.

). In all the carbon-star spectra, these lines could

not be fitted with our synthetic spectra. The calculations

underestimate the line strength, suggesting that the extended

atmospheres of luminous carbon stars are not well reproduced by

our hydrostatic models.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=18cm]{11857f03.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/30/aa11857-09/Timg89.png) |

Figure 3: Observation and fit of the carbon star B in NGC 1978. The fit parameters are given in Table 3. The relatively high effective temperature and low C/O ratio compared with the other carbon stars in our sample allowed a reasonable fit. Deviations can to a high fraction be ascribed to uncertain line data. The strong low-excitation CO lines in the K band are not reproduced by the models. See text for details. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

3.4 Stellar evolutionary models

The stellar evolutionary models presented in this paper have been computed with the FRANEC code (Chieffi et al. 1998). The release we are currently using is optimised to properly compute low-mass models during their AGB phase. Up-to-date input physics, such as low-temperature carbon-enhanced opacities, have been adopted (Lederer & Aringer 2009; Cristallo et al. 2007). Physical phenomena, such as hydrodynamical instabilities at radiative-convective interfaces and the mass-loss rate, have been properly taken into account (Cristallo et al. 2009; Straniero et al. 2006). The inclusion of an additional mixing mechanism taking place below the convective envelope (usually referred to as extra-mixing) during the RGB and the AGB phase was described in Paper I.

4 Results

4.1 Cluster membership

We derived the heliocentric radial velocity by cross-correlating

the H-band spectra with a template spectrum (using the IRAF task fxcor). Data for the star LE9 were taken in the semester 2008A,

and no radial velocity standard (K-type star) was recorded, so no

information could be deduced for this target. While the quality of

our LE8 data is too low to derive abundance ratios, it is still

adequate to measure the radial velocity (only with a

slightly larger error than for the other targets). The sample

shows a relatively homogeneous radial velocity distribution, the spread is

quite narrow, so we conclude that all our targets are actually

cluster members. The results are summarised in

Table 2. The value

![]() (with a velocity

dispersion of

(with a velocity

dispersion of

![]() )

we find is well

in line with earlier determinations (see Sect. 1). As a comparison,

Carrera et al. (2008) measured radial velocities in four fields with

different distances to the LMC centre. The mean values found

in the individual fields range from +278 to

)

we find is well

in line with earlier determinations (see Sect. 1). As a comparison,

Carrera et al. (2008) measured radial velocities in four fields with

different distances to the LMC centre. The mean values found

in the individual fields range from +278 to

![]() .

The velocity dispersion in the metallicity bin with

.

The velocity dispersion in the metallicity bin with

![]() is

is

![]() .

.

The errors for the carbon stars are systematically larger than for the oxygen-rich stars. This can easily be understood by looking at Fig. 2. The features in the C-rich case are usually broader and consequently the peak in the cross-correlation function (and thus the FWHM) is broader, too.

Table 2: Radial velocities of NGC 1978 targets

Table 3: Data and fit results for oxygen-rich (first group) and carbon-rich (second group) targets in NGC 1978.

4.2 Stellar parameters and abundance ratios

We summarise our fit results in Table 3. In the

first column, we list the star identifier (compare

Fig. 1), followed by the K magnitude and the

colour index (J-K) taken from the 2MASS database. In the next

two columns, we quote the effective temperature and luminosity

(rounded to

![]() )

resulting from the respective

colour calibrations and bolometric corrections (see

Sect. 3.3). The parameters resulting from our

fitting procedure (

)

resulting from the respective

colour calibrations and bolometric corrections (see

Sect. 3.3). The parameters resulting from our

fitting procedure (

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

C/O, 12C/ 13C) are listed in the

subsequent columns.

We note that none of our target stars is

a large amplitude variable, thus the influence of variability on

the stellar parameters can be safely ignored. A detailed

discussion of the small amplitude variability (

,

C/O, 12C/ 13C) are listed in the

subsequent columns.

We note that none of our target stars is

a large amplitude variable, thus the influence of variability on

the stellar parameters can be safely ignored. A detailed

discussion of the small amplitude variability (

![]() in R) will be given elsewhere (Wood & Lebzelter, in

preparation).

in R) will be given elsewhere (Wood & Lebzelter, in

preparation).

The derived effective temperatures are systematically higher than

the

![]() values inferred from the infrared colour

transformations (compare the resulting

values inferred from the infrared colour

transformations (compare the resulting

![]() to

to

![]() deduced from the fit in Table 3).

Better agreement between the two temperature

scales is found when we adopt a scaled solar oxygen abundance

rather than an over-abundance of

deduced from the fit in Table 3).

Better agreement between the two temperature

scales is found when we adopt a scaled solar oxygen abundance

rather than an over-abundance of

![]() ,

which was

our standard choice in the analysis (we refer to

Sects. 1 and 3.2 for details).

However, this is not too surprising since the colour-temperature

relations from Houdashelt et al. (2000) were derived from synthetic

spectra based on scaled solar abundances.

We want to mention that the results from

Smith et al. (2002, their Fig. 8) imply

,

which was

our standard choice in the analysis (we refer to

Sects. 1 and 3.2 for details).

However, this is not too surprising since the colour-temperature

relations from Houdashelt et al. (2000) were derived from synthetic

spectra based on scaled solar abundances.

We want to mention that the results from

Smith et al. (2002, their Fig. 8) imply

![]() for the LMC, contrary to our assumption.

Also, Mucciarelli et al. (2008) found that the other alpha element

abundances are roughly scaled solar

(

for the LMC, contrary to our assumption.

Also, Mucciarelli et al. (2008) found that the other alpha element

abundances are roughly scaled solar

(

![]() )

in NGC 1978.

However, in another recent work Goudfrooij et al. (2009)

derived

)

in NGC 1978.

However, in another recent work Goudfrooij et al. (2009)

derived

![]() for the LMC cluster NGC 1846.

Apart from the

influence on the temperature scale, a higher oxygen abundance

would shift the derived C/O ratios only to slightly higher

values (Fig. 4). The derived carbon isotopic

ratios are marginally affected by an oxygen over-abundance.

for the LMC cluster NGC 1846.

Apart from the

influence on the temperature scale, a higher oxygen abundance

would shift the derived C/O ratios only to slightly higher

values (Fig. 4). The derived carbon isotopic

ratios are marginally affected by an oxygen over-abundance.

We found that for the five oxygen-rich stars within our sample the

C/O ratio is varying little, the values range from 0.13 to 0.18 with a typical uncertainty of ![]() 0.05. The isotopic

ratios vary in the range between 9 and 16 with an uncertainty

ranging up to

0.05. The isotopic

ratios vary in the range between 9 and 16 with an uncertainty

ranging up to ![]() 4. Considering the error bars, all M stars

occupy more or less the same region in Fig. 5, where

we display the measured C/O and 12C/ 13C of

our sample stars.

No target is offset from the spot marking the abundance ratios

expected after the evolution on the first giant branch

(

4. Considering the error bars, all M stars

occupy more or less the same region in Fig. 5, where

we display the measured C/O and 12C/ 13C of

our sample stars.

No target is offset from the spot marking the abundance ratios

expected after the evolution on the first giant branch

(

![]() ,

12C/ 13C

,

12C/ 13C![]() 10). In other words, we

do not find conclusive signs of third dredge-up among the

oxygen-rich stars in the cluster. This is also consistent with the

results from Lloyd Evans (1983) who did not find S-type

stars in NGC 1978. The total number of our targets is small, so general statements

based on our results are rather weak due to the poor statistics.

However, the fact that we find oxygen-rich stars, in which the TDU

does not seem to be active, does not exclude that this phenomenon is

at work in other stars of the cluster.

10). In other words, we

do not find conclusive signs of third dredge-up among the

oxygen-rich stars in the cluster. This is also consistent with the

results from Lloyd Evans (1983) who did not find S-type

stars in NGC 1978. The total number of our targets is small, so general statements

based on our results are rather weak due to the poor statistics.

However, the fact that we find oxygen-rich stars, in which the TDU

does not seem to be active, does not exclude that this phenomenon is

at work in other stars of the cluster.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=18cm]{11857f04.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/30/aa11857-09/Timg125.png) |

Figure 4:

Fit of the H band spectrum of the target LE5 adopting different oxygen abundances. A value of

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm]{11857f05.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/30/aa11857-09/Timg127.png) |

Figure 5:

Measured abundances ratios C/O and 12C/ 13C for the targets in NGC 1978. Oxygen-rich targets appear to the left of the dotted line at

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

In fact, we also identify a sub-sample of

carbon-rich stars belonging to NGC 1978. Satisfactory fits could only

be achieved for the two hottest carbon stars (B and LE6) in our

sample. We also derived C/O and

12C/ 13C.

The error bars are larger than for the M stars, the reasons

for that are outlined in the previous sections.

For the two cool objects LE1 and LE3, we could

only derive lower limits for C/O and

12C/ 13C. For an

increasing carbon content, the features saturate, thus we cannot give a

reliable upper limit for C/O.

The C/O ratios that we found are in line with the

results obtained by other groups. Matsuura et al. (2005) adopted

![]() to explain molecular features in low-resolution spectra of LMC carbon stars.

Investigations of planetary nebulae in the LMC exhibit a range

of C/O ratios from

slightly above 1 up to even 5 (e.g. Stanghellini et al. 2005).

We are not aware of measurements of the carbon isotopic ratio

directly from carbon-rich AGB stars in the LMC

other than the ones presented here and in Paper I.

Reyniers et al. (2007) analysed the post-AGB object

MACHO 47.2496.8 (

to explain molecular features in low-resolution spectra of LMC carbon stars.

Investigations of planetary nebulae in the LMC exhibit a range

of C/O ratios from

slightly above 1 up to even 5 (e.g. Stanghellini et al. 2005).

We are not aware of measurements of the carbon isotopic ratio

directly from carbon-rich AGB stars in the LMC

other than the ones presented here and in Paper I.

Reyniers et al. (2007) analysed the post-AGB object

MACHO 47.2496.8 (

![]() )

in the LMC and derived

)

in the LMC and derived

![]() and

and

![]() .

A peculiar combination of

C/O and 12C/ 13C values even more extreme than those of

our carbon-rich targets was presented by de Laverny et al. (2006).

They found

.

A peculiar combination of

C/O and 12C/ 13C values even more extreme than those of

our carbon-rich targets was presented by de Laverny et al. (2006).

They found

![]() and

and

![]() for

BMB-B 30 (with

for

BMB-B 30 (with

![]() )

in the SMC.

)

in the SMC.

Qualitative estimates based on the K-band spectra of the targets

LE2 and LE7 suggest that those have an

effective temperature between the groups LE1-LE3 and B-LE6

(see Fig. 2). Except for the target

B, the difference between the derived effective temperature and

the

![]() value obtained from the colour transformation is not quite as

high as in the oxygen-rich case (about

value obtained from the colour transformation is not quite as

high as in the oxygen-rich case (about

![]() ). We

repeated the analysis for the star B with a scaled solar oxygen

abundance (as for LE5, Fig. 4) and also found

a lower

). We

repeated the analysis for the star B with a scaled solar oxygen

abundance (as for LE5, Fig. 4) and also found

a lower

![]() ,

whereas the C/O ratio remained basically

unchanged. Almost all spectral features in the carbon-rich case react

sensitively to temperature changes, therefore

,

whereas the C/O ratio remained basically

unchanged. Almost all spectral features in the carbon-rich case react

sensitively to temperature changes, therefore

![]() can

be better defined than the C/O ratio. A remarkable result is that

- opposite to our findings for NGC 1846 (Paper I) - we do not

find a saturation level for the carbon isotopic ratio. This

indicates that extra-mixing is not at work in NGC 1978.

can

be better defined than the C/O ratio. A remarkable result is that

- opposite to our findings for NGC 1846 (Paper I) - we do not

find a saturation level for the carbon isotopic ratio. This

indicates that extra-mixing is not at work in NGC 1978.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm]{11857f06.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/30/aa11857-09/Timg135.png) |

Figure 6:

Colour-magnitude diagram based on 2MASS data for NGC 1978 (complete within a radius of

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\mbox{\includegraphics[width=8.5cm]{11857f07.eps}\includegraphics[width=8.5cm]{11857f08.eps} }\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/30/aa11857-09/Timg136.png) |

Figure 7: Comparison between observational data and theoretical models. 12C/ 13C isotopic ratios vs. C/O ratios are reported. In the left panel we report the range of O-rich stars only, while in the right panel the whole sample has been considered. The star symbols with error bars indicate our observations. The red dotted, the blue dashed, and the green long-dashed curves in the left panel are partly covered by other tracks in the plot. The symbols in the left panel mark the end point of the tracks after the RGB phase. In the right panel, the symbols indicate the values attained during the interpulse phases, which are on the order of 103 times longer than the TDU episodes. See text for details. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

In Fig. 6 we show a CMD of NGC 1978 (see

Sect. 5 for a discussion of the photometric errors).

We do not plot the bolometric magnitudes on the

ordinate because of the inconsistent bolometric corrections

applied to the targets.

The CMD contains all targets that lie within a radius of

![]() with respect to the cluster centre (cf. Fig. 1).

Data points with superimposed symbols refer to stars contained in our sample.

The oxygen-rich stars (empty squares) seem to form a

sequence with a C/O ratio increasing with luminosity which might

hint at a mild dredge-up. However, this could be misleading, as we have

to take the error bars quoted in Table 3 into

account. Moreover, the isotopic ratios do not appear in an ordered

sequence. The carbon stars (red triangles) are brighter in K and have

significantly redder colours. For the stars LE1 and LE3, having

the highest (J-K) values, the indicated numbers refer to lower

limits for the abundance ratios. The two carbon stars

with the lowest K magnitude are

LE2 and LE7 which were excluded from our analysis. Both have

luminosities comparable to the brightest oxygen-rich

stars. A possible explanation is that these stars are in a

post-flash dip phase (Iben & Renzini 1983), displacing them

about 1 magnitude down from the average luminosity in this

evolutionary stage in the CMD (see also the discussion in

Paper I).

with respect to the cluster centre (cf. Fig. 1).

Data points with superimposed symbols refer to stars contained in our sample.

The oxygen-rich stars (empty squares) seem to form a

sequence with a C/O ratio increasing with luminosity which might

hint at a mild dredge-up. However, this could be misleading, as we have

to take the error bars quoted in Table 3 into

account. Moreover, the isotopic ratios do not appear in an ordered

sequence. The carbon stars (red triangles) are brighter in K and have

significantly redder colours. For the stars LE1 and LE3, having

the highest (J-K) values, the indicated numbers refer to lower

limits for the abundance ratios. The two carbon stars

with the lowest K magnitude are

LE2 and LE7 which were excluded from our analysis. Both have

luminosities comparable to the brightest oxygen-rich

stars. A possible explanation is that these stars are in a

post-flash dip phase (Iben & Renzini 1983), displacing them

about 1 magnitude down from the average luminosity in this

evolutionary stage in the CMD (see also the discussion in

Paper I).

5 Discussion

We seek to explain the following observed features of NGC 1978:

- 1.

- the cluster harbours carbon stars;

- 2.

- the M stars do not show conclusive signs of third dredge-up;

- 3.

- there is no saturation of the carbon isotopic ratio.

The first point in the list is a clear indication of ongoing TDU in the cluster. The second point may at first seem to contrast this statement, while low number statistics could resolve this apparent contradiction: the lifetime of a thermally pulsing AGB star is short, so in a sample of a few stars we do not necessarily have to find a star with an enhanced carbon abundance. This possibly explains the large gap between the M and the C stars in terms of C/O (see Fig. 5). An alternative scenario where the TDU is so efficient that the star becomes carbon-rich after a single dredge-up episode occurs only at much lower metallicity (e.g. Herwig et al. 2000).

Let us put aside the C/O error bars for a moment and speculate

about the group of M stars. The 2MASS data come with uncertainties

in K of lower than 0.05, except for LE10 where the error is 0.076![]() In any case, the luminosity sequence

that the stars form is conserved. The star LE9 is the faintest at K, with mK=12.3,

in the sample and also the star with the lowest C/O ratio.

Cioni et al. (2000) identify the RGB tip in the LMC at

In any case, the luminosity sequence

that the stars form is conserved. The star LE9 is the faintest at K, with mK=12.3,

in the sample and also the star with the lowest C/O ratio.

Cioni et al. (2000) identify the RGB tip in the LMC at

![]() .

According to this value, LE9 could as

well be an RGB star or located at the early-AGB. The targets LE5

and LE10 are possibly at the very beginning of the thermally

pulsing asymptotic giant branch (TP-AGB) star phase. The case of

LE4 and, in particular, A is more difficult. Comparing these stars

with those of similar luminosity in the sample of NGC 1846, we

note that the latter are classified as S stars and present C/O ratios of 0.4 or even higher. The C/O ratio we find for the star

A (0.23) is slightly higher than the average of the other stars,

perhaps compatible with just one (the first) TDU episode.

The bolometric magnitude of A also roughly corresponds to the

limit we found for the onset of the TDU in NGC 1846 (

.

According to this value, LE9 could as

well be an RGB star or located at the early-AGB. The targets LE5

and LE10 are possibly at the very beginning of the thermally

pulsing asymptotic giant branch (TP-AGB) star phase. The case of

LE4 and, in particular, A is more difficult. Comparing these stars

with those of similar luminosity in the sample of NGC 1846, we

note that the latter are classified as S stars and present C/O ratios of 0.4 or even higher. The C/O ratio we find for the star

A (0.23) is slightly higher than the average of the other stars,

perhaps compatible with just one (the first) TDU episode.

The bolometric magnitude of A also roughly corresponds to the

limit we found for the onset of the TDU in NGC 1846 (

![]() ).

).

5.1 Stellar evolutionary models

In this section we present theoretical tracks computed with the FRANEC code, and we compare them with observations. In the left panel of Fig. 7, we report the evolution of the 12C/ 13C versus C/O curves from the pre-main sequence up to the early-AGB phase in the region where the M stars of NGC 1978 lie. In practice, the end point of each curve (marked by a symbol in the left panel of Fig. 7) represents the value attained at the tip of the RGB phase, which is conserved up to the onset of the first thermal pulse. In the right panel, instead, we extend the axes to also include the C-rich stars. We plot the whole AGB evolutionary tracks and mark the values attained after each TDU episode.

We firstly concentrate on the O-rich stars of our sample. We carry

on our analysis under the assumption that these stars have not

experienced TDU, because they still are at the beginning of the

TP-AGB phase or because they arrived on the AGB with a too small

envelope mass. In this case, their initial surface composition

has been modified by the occurrence of the First Dredge-up

(FDU) only and, eventually, by an additional slow mixing operating

below the convective envelope during the RGB phase (the so called

extra-mixing, see e.g. Denissenkov & Pinsonneault 2008; Nollett et al. 2003; Charbonnel & Zahn 2007). Our reference model (ST, dash-dotted magenta curve) has an initial mass

![]() with Z=0.006, corresponding to

with Z=0.006, corresponding to

![]() .

We assume an

initial solar-scaled composition, which implies

.

We assume an

initial solar-scaled composition, which implies

![]() and

and

![]() .

After the FDU, the surface

values attain

.

After the FDU, the surface

values attain

![]() and

and

![]() .

This is due to the fact that the

convective envelope penetrates into regions where partial

hydrogen-burning occurred before. No extra-mixing has been included

in the ST case.

The values so obtained clearly disagree with the M stars observations,

which show an average

.

This is due to the fact that the

convective envelope penetrates into regions where partial

hydrogen-burning occurred before. No extra-mixing has been included

in the ST case.

The values so obtained clearly disagree with the M stars observations,

which show an average

![]() and an average

and an average

![]() .

Thus, we explored the

possibility of an occurrence of extra-mixing on the RGB.

.

Thus, we explored the

possibility of an occurrence of extra-mixing on the RGB.

This hypothesis is supported by the bulk of observations of RGB stars in the

galactic field, as well as in open and globular

clusters (see e.g. Gratton et al. 2000).

These observations show that this additional mixing occurs in low-mass stars (

![]() )

during the first ascent along the Red Giant Branch.

Moreover, Eggleton et al. (2008) identified a mixing mechanism driven

by a molecular weight inversion (

)

during the first ascent along the Red Giant Branch.

Moreover, Eggleton et al. (2008) identified a mixing mechanism driven

by a molecular weight inversion (![]() -mixing) in three-dimensional

stellar models that must operate in all low-mass stars while they are on the RGB.

The operation of this RGB

extra-mixing is also required to explain the relatively low

12C/ 13C ratios in the M stars of NGC 1846 (Paper I).

-mixing) in three-dimensional

stellar models that must operate in all low-mass stars while they are on the RGB.

The operation of this RGB

extra-mixing is also required to explain the relatively low

12C/ 13C ratios in the M stars of NGC 1846 (Paper I).

As in Paper I, we include this additional mixing right

after the RGB luminosity bump. The extension of the zone in which

this additional mixing takes place is fixed by prescribing the

maximum temperature the material is exposed to

(

![]() ). The circulation rate is tuned by setting the

mixing velocity to a value that is a small fraction (cf. Paper I)

of the typical convective velocities in the envelope of an RGB star. As discussed in

Paper I, the carbon isotopic ratio largely depends on

). The circulation rate is tuned by setting the

mixing velocity to a value that is a small fraction (cf. Paper I)

of the typical convective velocities in the envelope of an RGB star. As discussed in

Paper I, the carbon isotopic ratio largely depends on

![]() .

In Fig. 7

we report two models, characterised by

.

In Fig. 7

we report two models, characterised by

![]() K (red dotted curve) and

K (red dotted curve) and

![]() K (blue short-dashed curve). In the

first case, the final 12C/ 13C ratio decreases, reaching a

value in good agreement with those observed in the M stars of NGC 1978. Notwithstanding, the C/O ratio remains unaltered and higher

than the observed one. An increase of

K (blue short-dashed curve). In the

first case, the final 12C/ 13C ratio decreases, reaching a

value in good agreement with those observed in the M stars of NGC 1978. Notwithstanding, the C/O ratio remains unaltered and higher

than the observed one. An increase of

![]() up to

up to

![]() K leads to a lower C/O ratio of about 0.21, which is in

better agreement with the observations. However, the corresponding

12C/ 13C ratio is 5, which is definitely

lower than the average value (11). Note that only LE5 shows such a

low value (

K leads to a lower C/O ratio of about 0.21, which is in

better agreement with the observations. However, the corresponding

12C/ 13C ratio is 5, which is definitely

lower than the average value (11). Note that only LE5 shows such a

low value (

![]() ).

).

Then, we explored the possible effect of an oxygen

enhancement (see the discussion in Sect. 2.1). The

black solid line in Fig. 7 represents a model similar to

the ST case, but with

![]() .

As for the ST case, the effects

of the FDU are clearly recognisable. An additional model, as

obtained by including an RGB extra-mixing

(

.

As for the ST case, the effects

of the FDU are clearly recognisable. An additional model, as

obtained by including an RGB extra-mixing

(

![]() K) is also reported (green line).

The final surface composition of this model (

K) is also reported (green line).

The final surface composition of this model (

![]() and

and

![]() )

is close to the average values of the

observed sample (

)

is close to the average values of the

observed sample (

![]() and

and

![]() ). Thus, a first

conclusion is that moderate RGB extra-mixing

(

). Thus, a first

conclusion is that moderate RGB extra-mixing

(

![]() K) coupled to

moderate oxygen enhancement appears to nicely reproduce the

observed average composition of the M stars in NGC 1978. The same

conclusion has been reached in the case of NGC 1846 (Paper I).

K) coupled to

moderate oxygen enhancement appears to nicely reproduce the

observed average composition of the M stars in NGC 1978. The same

conclusion has been reached in the case of NGC 1846 (Paper I).

What are the implications of this scenario when applied to the whole observational sample (O-rich and C-rich stars)? We carry on our analysis assuming that the carbon stars are intrinsic, i.e. that their surface composition, in particular the high C/O and carbon isotopic ratios, is the result of nucleosynthesis and mixing processes occurring during the thermally pulsing AGB evolution.

In the right panel of Fig. 7 we report

the same models as shown in the left panel.

None of the theoretical tracks can simultaneously reproduce the abundance

ratios of the M and C stars. The high values of the C-star

carbon isotopic ratio can only be reproduced by the oxygen-enhanced

model with no RGB extra-mixing. All the other models predict too low

12C/ 13C ratios. The situation appears even more peculiar when compared

with the case of NGC 1846, for which we found C stars with higher values

of C/O, but with

![]() between 60 and 70, so that an AGB

extra-mixing (in addition to the RGB extra-mixing) was invoked to

reproduce the observations. The vast difference between the two

clusters is illustrated in Fig. 8. In the left panel,

data for NGC 1978 are compared with three models computed under

different assumptions for the RGB and the AGB extra-mixing,

namely no extra-mixing (black-solid line), moderate RGB

extra-mixing only (green-long-dashed line), and moderate AGB

extra-mixing only (blue-dashed line). All the three models have

between 60 and 70, so that an AGB

extra-mixing (in addition to the RGB extra-mixing) was invoked to

reproduce the observations. The vast difference between the two

clusters is illustrated in Fig. 8. In the left panel,

data for NGC 1978 are compared with three models computed under

different assumptions for the RGB and the AGB extra-mixing,

namely no extra-mixing (black-solid line), moderate RGB

extra-mixing only (green-long-dashed line), and moderate AGB

extra-mixing only (blue-dashed line). All the three models have

![]() and

and

![]() .

In the right panel, data for NGC 1846

are compared with similar models. In this case, the mass is

.

In the right panel, data for NGC 1846

are compared with similar models. In this case, the mass is

![]() and

the red-dashed line refers to a model with both RGB

and AGB extra-mixing (see Paper I for more details on models

with AGB extra-mixing). In summary, the high carbon isotopic

ratio observed for the C stars of NGC 1978

(

and

the red-dashed line refers to a model with both RGB

and AGB extra-mixing (see Paper I for more details on models