| Issue |

A&A

Volume 501, Number 1, July I 2009

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Page(s) | 89 - 102 | |

| Section | Extragalactic astronomy | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/200811284 | |

| Published online | 29 April 2009 | |

The X-ray view of giga-hertz peaked spectrum radio galaxies

O. Tengstrand1,2 - M. Guainazzi1 - A. Siemiginowska3 - N. Fonseca Bonilla1 - A. Labiano4 - D. M. Worrall5 - P. Grandi6 - E. Piconcelli7

1 - European Space Astronomy Centre of ESA, PO Box 78, Villanueva de la Cañada, 28691 Madrid, Spain

2 -

Institute of Technology, University of Linköping, 581 83 Linköping, Sweden

3 -

Harvard-Smithsonian Centre for Astrophysics, 60 Garden St., Cambridge, MA 02138, USA

4 -

Departamento de Astrofísica Molecular e Infrarroja, Instituto de Estructura de la Materia (CSIC), Madrid, Spain

5 -

H. H. Wills Physics Laboratory, University of Bristol, Tyndall Avenue, Bristol BS8 1TL, UK

6 -

Istituto di Astrofisica Spaziale e Fisica Cosmica-Bologna, INAF, via Gobetti 101, 40129 Bologna, Italy

7 -

Osservatorio Astronomico di Roma (INAF), via Frascati 33, 00040 Monteporzio Catone, Roma, Italy

Received 3 November 2008 / Accepted 11 March 2009

Abstract

Context. This paper presents the X-ray properties of a flux- and volume-limited complete sample of 16 giga-hertz peaked spectrum (GPS) galaxies.

Aims. This study addresses three basic questions in our understanding of the nature and evolution of GPS sources: a) What is the physical origin of the X-ray emission in GPS galaxies? b) Which physical system is associated with the X-ray obscuration? c) What is the ``endpoint'' of the evolution of compact radio sources?

Methods. We discuss in this paper the results of the X-ray spectral analysis, and compare the X-ray properties of the sample sources with radio observables.

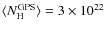

Results. We obtain a 100% (94%) detection fraction in the 0.5-2 keV (0.5-10 keV) energy band. GPS galaxy X-ray spectra are typically highly obscured (

![]() cm-2;

cm-2;

![]() dex). The X-ray column density is larger than the HI column density measured in the radio by a factor 10 to 100. GPS galaxies lie well on the extrapolation to high radio powers of the correlation between radio and X-ray luminosity known in low-luminosity FR I radio galaxies. On the other hand, GPS galaxies exhibit a comparable X-ray luminosity to FR II radio galaxies, notwithstanding their much larger radio luminosity.

dex). The X-ray column density is larger than the HI column density measured in the radio by a factor 10 to 100. GPS galaxies lie well on the extrapolation to high radio powers of the correlation between radio and X-ray luminosity known in low-luminosity FR I radio galaxies. On the other hand, GPS galaxies exhibit a comparable X-ray luminosity to FR II radio galaxies, notwithstanding their much larger radio luminosity.

Conclusions. The X-ray to radio luminosity ratio distribution in our sample is consistent with the bulk of the high-energy emission being produced by the accretion disk, as well as with dynamical models of GPS evolution where X-rays are produced by Compton upscattering of ambient photons. Further support to the former scenario comes from the location of GPS galaxies in the X-ray to O[ III] luminosity ratio versus ![]() plane. We propose that GPS galaxies are young radio sources, which would reach their full maturity as classical FR II radio galaxies. However, column densities

plane. We propose that GPS galaxies are young radio sources, which would reach their full maturity as classical FR II radio galaxies. However, column densities

![]() 1022 cm-2 could lead to a significant underestimate of dynamical age determinations based on the hotspot recession velocity measurements.

1022 cm-2 could lead to a significant underestimate of dynamical age determinations based on the hotspot recession velocity measurements.

Key words: galaxies: jets - galaxies: active - X-rays: galaxies

1 The nature of GPS radio galaxies

This paper presents an X-ray study of a complete radio-selected sample of Giga-Hertz Peaked Spectrum (GPS) galaxies. GPS sources are characterised by a simple convex radio spectrum peaking near 1 GHz (Stanghellini 2006; Lister 2003; O'Dea 1998). They represent about 10% of the 5-GHz selected sources. About half of known GPS sources are morphologically classified as galaxies, the remaining as quasars. They often exhibit symmetric, very compact (10-100 pc) structures, reminiscent of those present in extended radio galaxies on much larger scales.

Little is known about their high-energy emission. GPS galaxies are rather elusive in X-rays (O'Dea et al. 1996). X-ray spectroscopic studies prior to modern X-ray observatories were inconclusive on whether this low detection rate is due to intrinsic weakness or to obscuration of the active nucleus (Elvis et al. 1994a). Deep Chandra and XMM-Newton observations of GPS galaxies are scanty. One of the few exceptions is a deep XMM-Newton pointing of 3C 301.1 (O'Dea et al. 2006); it unveiled a hard X-ray emission component, which could be associated with hot gas shocked by the expansion of the radio source or to synchrotron self-Compton emission. Analysis of small samples of GPS galaxies observed with XMM-Newton were presented by Vink et al. (2005) and Guainazzi et al. (2006). Our paper represents an extension of their results.

Understanding the origin of high-energy emission in these objects may have important implications on the birth and evolution of the ``radio power'' in the Universe. GPS sources were originally suggested to represent radio galaxies in the early stage of their life (typical ages <104 years, Fanti et al. 1995; Murgia 2003). This possibility was recently supported by the detection of mas-hotspot proper motions (Poladitis & Conway 2003; Gugliucci et al. 2005). Alternatively, as originally suggested by Gopal-Krishna & Wiita (1991), GPS sources could remain compact during their whole radiative lifetime, because interaction with dense circumnuclear matter impedes their full growth.

Table 1: The GPS sample discussed in this paper.

In order to address the above issues, and provide the best possible estimate of the gas density in the GPS galaxy nuclear environment, we have undertaken an XMM-Newton observation program of a radio-selected complete sample of GPS galaxies. The three main issues which originally motivated our study, and will be discussed throughout the paper, are:

- What is the physical origin of the X-ray emission

in GPS galaxies?

- Which physical system is associated with the X-ray obscuration?

- What is the ``endpoint'' of the evolution of

compact radio sources?

2 The sample

The sources discussed in this paper

constitute a flux- and volume-limited sub-sample

extracted from the complete radio-selected sample of GPS galaxies of

Stanghellini et al. (1998). We'll refer to this

sub-sample as ``our GPS sample'' hereafter.

We selected all sources with redshift

z<1, and flux density at 5 GHz ![]() 1 Jy.

The whole sample

(16 sources) has been observed with XMM-Newton across different

observing cycles. The only exceptions are

PKS 0941-08 and PKS1345+125, for which archival Chandra and ASCA data are available, respectively.

Preliminary results, based on a small

sub-sample of 5 objects, were presented in Guainazzi et al.

(2006)

1 Jy.

The whole sample

(16 sources) has been observed with XMM-Newton across different

observing cycles. The only exceptions are

PKS 0941-08 and PKS1345+125, for which archival Chandra and ASCA data are available, respectively.

Preliminary results, based on a small

sub-sample of 5 objects, were presented in Guainazzi et al.

(2006)![]() .

Some of the sample sources were included in Vink et al. (2005).

The whole sample is listed in Table 1.

A more general discussion of the X-ray and multiwavelength properties of

our whole GPS sample is deferred to Sect. 5.

A summary of the X-ray and radio properties of the whole sample

is in Appendix B.

.

Some of the sample sources were included in Vink et al. (2005).

The whole sample is listed in Table 1.

A more general discussion of the X-ray and multiwavelength properties of

our whole GPS sample is deferred to Sect. 5.

A summary of the X-ray and radio properties of the whole sample

is in Appendix B.

3 Observations and data reduction

In this paper (as also originally done by Guainazzi et al. 2006; and Vink et al. 2005) we will consider only X-ray data taken with the XMM-Newton EPIC cameras (pn, Strüder et al. 2001; MOS, Turner et al. 2001), because the sources were too faint to yield a measurable signal in the high-resolution RGS cameras. Observational information for the sources for which new measurements are presented here is listed in Table 2.

Table 2:

Properties of the X-ray observations discussed in this paper.

Exposure times (![]() )

and Count Rates (CR) refer to the pn

in the 0.5-10 keV band (unless otherwise specified).

)

and Count Rates (CR) refer to the pn

in the 0.5-10 keV band (unless otherwise specified).

![]() is the count rate threshold applied in the determination

of the Good Time Interval for scientific product extraction (details in

text).

is the count rate threshold applied in the determination

of the Good Time Interval for scientific product extraction (details in

text). ![]() is the radius of the scientific products extraction

region.

is the radius of the scientific products extraction

region.

![]() is the column density due to gas in the Milky Way

along the line-of-sight to the GPS galaxy (Kalberla et al. 2005)

in units of 1020 cm-2.

is the column density due to gas in the Milky Way

along the line-of-sight to the GPS galaxy (Kalberla et al. 2005)

in units of 1020 cm-2.

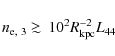

![\begin{figure}

\par\mbox{\includegraphics[height=58mm,angle=270]{1284f1.ps}\hspa...

...space{0.3cm}

\includegraphics[height=58mm,angle=270]{1284f3.ps} }

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/25/aa11284-08/Timg27.png) |

Figure 1:

Spectra of the three EPIC instruments

( upper panels), and

residuals in units of standard deviation

( lower panels) when the baseline model is applied.

In addition to the binning applied to the spectra to ensure

the applicability of the |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Table 3: Best-fit parameters and results for the sources where spectral analysis was possible.

XMM-Newton data were reduced with SASv7.1 (Gabriel et al. 2003)

according to standard procedures as in, e.g.,

Guainazzi et al. (2006). The most updated calibration files available at

the date of the analysis (February 2008) were used.

Source scientific products were accumulated from circular regions

surrounding the position of the optical nucleus of each source

(extracted from the NED catalogue)![]() . The size of the

source extraction regions are shown in Table 2.

Following Guainazzi (2008), background scientific products

were extracted from source free circular regions

close to the source and on the same CCD as the source

for the MOS cameras; and from source-free regions

centred at the same

row in detector coordinates as the source in nearby CCDs

for the pn. As many of

the sources were X-ray faint,

particular care has been applied in the choice of

flaring particle background rejection

thresholds optimising the signal-to-noise ratio of the final scientific

products. Using a single-event, E>10 keV full field-of-view light

curve as a monitoring tool of the instantaneous intensity of the

background, ten different logarithmically spaced thresholds

between 0.1 s-1 and about two times the highest

light curve count rates were tried.

For each threshold the radius of the source extraction region

was also varied to obtain the highest number of net counts for a given

signal-to-noise ratio.

Spectra were binned in such a way to avoid oversampling

of the intrinsic instrumental energy resolution by

a factor larger than 3, and to have at least 25 background-subtracted

counts in each spectral bin. These conditions ensure

the applicability of the

. The size of the

source extraction regions are shown in Table 2.

Following Guainazzi (2008), background scientific products

were extracted from source free circular regions

close to the source and on the same CCD as the source

for the MOS cameras; and from source-free regions

centred at the same

row in detector coordinates as the source in nearby CCDs

for the pn. As many of

the sources were X-ray faint,

particular care has been applied in the choice of

flaring particle background rejection

thresholds optimising the signal-to-noise ratio of the final scientific

products. Using a single-event, E>10 keV full field-of-view light

curve as a monitoring tool of the instantaneous intensity of the

background, ten different logarithmically spaced thresholds

between 0.1 s-1 and about two times the highest

light curve count rates were tried.

For each threshold the radius of the source extraction region

was also varied to obtain the highest number of net counts for a given

signal-to-noise ratio.

Spectra were binned in such a way to avoid oversampling

of the intrinsic instrumental energy resolution by

a factor larger than 3, and to have at least 25 background-subtracted

counts in each spectral bin. These conditions ensure

the applicability of the ![]() statistic as a goodness-of-fit test.

statistic as a goodness-of-fit test.

In this paper, errors on the spectral parameters

and on any derived quantities are at the 90% confidence

level for one interesting parameter; errors on the count rates and

derived quantities are at 1![]() level. Whenever statistical

moments or correlations on distributions including upper limits are

calculated, an extension of the regression method on censored data

originally described by Schmitt (1985) and Isobe et al.

(1986) has been used.

More details on this method were presented by Guainazzi et al. (2006).

level. Whenever statistical

moments or correlations on distributions including upper limits are

calculated, an extension of the regression method on censored data

originally described by Schmitt (1985) and Isobe et al.

(1986) has been used.

More details on this method were presented by Guainazzi et al. (2006).

4 Results

In this Section we present spectral-analysis for the 7 unpublished sources in our GPS sample.

No significant variability in either integrated X-ray flux or spectral

shape was detected in any source presented in this paper

on timescales

![]() 104 s.

We therefore focus on

the properties

of their time-averaged spectra.

104 s.

We therefore focus on

the properties

of their time-averaged spectra.

For 3 of these

sources the number of degrees of freedom in the binned spectra

was larger than 4: 4C+32.44, PKS1607+26, PKS 2127+04.

In these cases a standard spectral analysis was possible. The

spectra were fitted in the 0.2-10 keV energy range with

Xspec (version 11; Arnaud 1996).

A model consisting of three

components was used:

| (1) |

where the photo-electric absorption components use Wisconsin cross-sections (Morrison & McCammon 1983), and Kis the unabsorbed spectral normalisation at 1 keV. We'll refer to this model as our ``baseline'' model hereafter. The column density

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=16cm]{11284-fig2.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/25/aa11284-08/Timg44.png) |

Figure 2:

Confidence level loci in the ( |

| Open with DEXTER | |

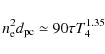

For 4 other sources (4C+00.02, PKS 0428+20, 4C+14.41, and PKS 2008-068)

the low signal-to-noise did not allow for spectral analysis. We have therefore

based our estimation of the spectral parameters of the baseline

model on the Hardness Ratio (HR), here defined as the ratio between the counts in the energy bands 1-10 keV and 0.2-1 keV. The measured HRs (or lower limit thereof) have been compared

with the predictions of grids of simulated baseline models.

Iso-HR contour plots in the ![]() ([0.5:3]) versus

([0.5:3]) versus ![]() ([1020, 1024 cm-2]) parameter space were built (see Fig. 2)

The confidence interval in column density was estimated as the minimum and maximum

value of the 1.6

([1020, 1024 cm-2]) parameter space were built (see Fig. 2)

The confidence interval in column density was estimated as the minimum and maximum

value of the 1.6![]() interval around the curve corresponding to the

nominal HR, when

interval around the curve corresponding to the

nominal HR, when ![]() was constrained in the range: [0.63, 2.62].

The photon-index range corresponds to the

was constrained in the range: [0.63, 2.62].

The photon-index range corresponds to the

![]() interval of the

interval of the ![]() distribution, calculated on the

whole sample of GPS galaxy for which the data quality

allowed us to perform a spectral analysis (cf. Fig. 6).

The resulting constraints on the column density are shown in Table 4.

distribution, calculated on the

whole sample of GPS galaxy for which the data quality

allowed us to perform a spectral analysis (cf. Fig. 6).

The resulting constraints on the column density are shown in Table 4.

Table 4:

Constraints on the intrinsic column density

derived from iso-HR contours in the ![]() versus

versus ![]() parameter space. No constraint can be derived for 4C+00.02.

parameter space. No constraint can be derived for 4C+00.02.

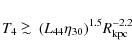

4.1 A Compton-thick AGN in PKS1607+26?

The fit of the EPIC spectra of PKS1607+26 yields an unusually flat spectral

index:

![]() .

A flat spectrum may be indicative of a blazar-type spectral component.

Alternatively, in radio-quiet AGN spectral indices

.

A flat spectrum may be indicative of a blazar-type spectral component.

Alternatively, in radio-quiet AGN spectral indices

![]() are generally interpreted

as evidence for a Compton-thick AGN, whose primary X-ray emission is

totally suppressed by optically thick matter with a column density

are generally interpreted

as evidence for a Compton-thick AGN, whose primary X-ray emission is

totally suppressed by optically thick matter with a column density

![]() cm-2(see Comastri 2004, for a review). In Compton-thick AGN, residual X-ray emission

red-wards the photoelectric cutoff could be due to Compton-reflection of the

otherwise invisible primary radiation off the obscuring matter

cm-2(see Comastri 2004, for a review). In Compton-thick AGN, residual X-ray emission

red-wards the photoelectric cutoff could be due to Compton-reflection of the

otherwise invisible primary radiation off the obscuring matter![]() .

.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[height=80mm,angle=-90]{1284f8.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/25/aa11284-08/Timg51.png) |

Figure 3: EPIC-pn spectrum of PKS1607+26 in the 2-10 keV energy band (observer's frame). The data points have been rebinned such that each displayed spectral channel has a signal-to-noise ratio larger than 1. The solid line represents the best-fit reflection-dominated model (details in text). |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[height=80mm,angle=-90]{1284f9.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/25/aa11284-08/Timg52.png) |

Figure 4:

Iso- |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[height=80mm,angle=-90]{1284f10.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/25/aa11284-08/Timg58.png) |

Figure 5:

Iso- |

| Open with DEXTER | |

5 Comparison with control samples of ``normal'' radio galaxies

In this section we present X-ray spectral properties of the flux density and redshift-selected complete sub-sample extracted from the Stanghellini et al. (1998) GPS sample described in Sect. 2. Readers are referred to the Guainazzi et al. (2006) and Vink et al. (2005) papers for the spectral analysis of the sources not discussed in this paper. We have repeated the analysis of the sources of the Vink et al. (2005) with the same reduction and data screening criteria as in the Guainazzi et al. (2006) and in this paper. The results of our re-analysis are consistent with theirs. 5 GHz luminosities are taken from Stanghellini et al. (1998) and O'Dea (1998).

Our goal is also to compare the properties of the complete radio-selected flux-limited GPS sample with a control sample of ``normal'' radio galaxies. The control sample has been built from results recently published in the literature. It is based on observations of z<1 radio galaxies taken by ASCA (Sambruna et al. 1999), BeppoSAX (Grandi et al. 2006), XMM-Newton and Chandra (FR I: Evans et al. 2006; Balmaverde et al. 2006; Donato et al. 2004, FR II: Evans et al. 2006; Belsole et al. 2006; Hardcastle et al. 2006). Only one measurement per source has been retained in the control sample, based on the latest published result. However, we have considered the latest Chandra measurement, even when a later XMM-Newton observation was available, under the assumption that the superior spatial resolution of the Chandra optics provides a more reliable measurement of the core emission. The control sample comprises 93 sources (32 FR I, 54 FR II, the remaining ones have no FR classification). We stress that the control sample is neither complete nor unbiased. Moreover, it is not well matched with our GPS sample in redshift. The probability that the redshift distribution of the GPS sample is the same as in the entire control sample is 2% only. This difference is mainly due to FR Is being generally at lower redshift than our GPS sample, whereas our GPS and the control FR II samples are well matched in redshift (cf. Fig. 8). Whenever pertinent, we will explicitly show in the following the redshift dependence of the observables, and discuss possible bias associated with comparing samples inhomogeneous in redshift coverage.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{1284f11.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/25/aa11284-08/Timg59.png) |

Figure 6: Distribution of the photon index for the GPS sub-sample (8 objects), where data quality warranted spectral analysis. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

5.1 X-ray detection fraction

We obtain a very large detection fraction; all the sources of our sample yield a detection in the soft X-ray band (0.5-2 keV), whereas 15 out of 16 are detected in the full band (0.5-10 keV). All of them but one (PKS1345+125) were unknown in X-rays prior to our Chandra (see also Siemiginowska et al. 2008) and XMM-Newton observations.

5.2 Spectral shape

In Fig. 6 we show the distribution of spectral indices for

the 8 GPS of our sample![]() ,

where the number of counts is good enough for the

spectral analysis to be possible. The distribution has

a mean value

,

where the number of counts is good enough for the

spectral analysis to be possible. The distribution has

a mean value

![]() ,

and a standard deviation

,

and a standard deviation

![]() .

The weighted mean is

.

The weighted mean is

![]() if the measurements are weighted according to the inverse

square of their statistical uncertainties.

if the measurements are weighted according to the inverse

square of their statistical uncertainties.

5.3 Obscuration

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm]{1284f12.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/25/aa11284-08/Timg63.png) |

Figure 7: Distribution of the core obscuring column densities for the GPS sample ( bottom panel), the FR I ( upper panel) and FR II ( middle panel) control samples. Shaded areas indicate upper limits; empty areas indicate lower limits. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

In Fig. 7 the distribution of column density for the GPS sources

of our sample is shown. The mean value of the distribution is

![]() cm-2 with a standard

deviation

cm-2 with a standard

deviation

![]() dex.

The same figure shows the comparison with the control sample.

The core emission of FR I radio galaxies is generally unobscured or

only mildly obscured. In the Donato et al. (2004) FR I sample, less than

one-third of the sample exhibit excess obscuration above the

Galactic contribution, with rest-frame column densities in the

range

1020-21 cm-2, thus significantly lower than

observed in our sample.

The average of the column density distribution in the FR I

control sample is

dex.

The same figure shows the comparison with the control sample.

The core emission of FR I radio galaxies is generally unobscured or

only mildly obscured. In the Donato et al. (2004) FR I sample, less than

one-third of the sample exhibit excess obscuration above the

Galactic contribution, with rest-frame column densities in the

range

1020-21 cm-2, thus significantly lower than

observed in our sample.

The average of the column density distribution in the FR I

control sample is

![]() cm-2.

cm-2.

FR II cores tend instead to include a heavily obscured component. However, a detailed quantitative

comparison between the GPS and the FR II control sample is difficult.

For 11 out of 54 FR II sources neither a measurement nor an upper limit on

the column density is available in the literature. These sources

are generally considered as unobscured (Hardcastle et al. 2006).

Lack of inclusion of these sources could potentially bias the control sample ![]() distribution towards higher values. Bearing this caveat in mind, GPS galaxies

seems to fill a gap in the

distribution towards higher values. Bearing this caveat in mind, GPS galaxies

seems to fill a gap in the ![]() distribution between highly obscured

(

distribution between highly obscured

(

![]() 1023 cm-2) and unobscured

(

1023 cm-2) and unobscured

(

![]() 1022 cm-2) FR II spectral components.

1022 cm-2) FR II spectral components.

A potential area of concern is the comparison of column density measurements in samples, which are not well matched in redshift. However, Fig. 8 shows that this bias is not responsible for the difference between the average of the column density distribution in the GPS and FR II samples. Moreover, low-redshift GPS galaxies exhibit column densities not systematically lower than high-redshift ones.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm]{1284f13.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/25/aa11284-08/Timg65.png) |

Figure 8: Core obscuring column density as a function of redshift for the GPS galaxies ( filled dots) and the FR II control sample ( empty squares). |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Hardcastle et al. (2006) remark that heavily absorbed nuclei are

rather common in narrow-line radio galaxies, whereas they are

comparatively rare in Low-Excitation Radio Galaxies

(LERG, Laing et al. 1994). There are

7 LERGs in our control sample; 5 of them have no column density

measurement; the remaining two have column density of

![]()

![]() cm-2 (3C 123, Hardcastle et al. 2006)

and

cm-2 (3C 123, Hardcastle et al. 2006)

and ![]() 1023 cm-2 (3C 427.1, Belsole et al. 2006).

Taking into account the low number statistics and the uncertainties

on the column density upper limits on formally ``unobscured'' LERGs,

the comparison between X-ray obscuration in LERGs and GPSs

is inconclusive.

1023 cm-2 (3C 427.1, Belsole et al. 2006).

Taking into account the low number statistics and the uncertainties

on the column density upper limits on formally ``unobscured'' LERGs,

the comparison between X-ray obscuration in LERGs and GPSs

is inconclusive.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm]{1284f14.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/25/aa11284-08/Timg68.png) |

Figure 9: Comparison between the column densities measured in X-rays ( this paper) and with atomic hydrogen observations (Pihlström et al. 2003). The lines represent loci of constant X-ray versus HI column density ratio for ratio values of 1, 10, and 100 (from right to left), respectively. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{1284f15.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/25/aa11284-08/Timg70.png) |

Figure 10:

X-ray column density versus the size of the radio structure. The solid line represent the best censored data linear fit with a function:

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

The X-ray column density is significantly larger than

the column density measured by HI observations

by a factor 10 to 100. The comparison is shown in Fig. 9.

The estimate of the HI column density depends

on the values assumed for the spin temperature, ![]() ,

and for the fraction of background source covered

by the absorber,

,

and for the fraction of background source covered

by the absorber, ![]() .

The data in Fig. 9

assume

.

The data in Fig. 9

assume

![]() K and

K and

![]() (Pihlström et al. 2003; Gupta et al. 2006; Vermeulen et al. 2003).

The X-ray versus HI column density relation can be fit

with a zero-offset linear function if

(Pihlström et al. 2003; Gupta et al. 2006; Vermeulen et al. 2003).

The X-ray versus HI column density relation can be fit

with a zero-offset linear function if ![]() is of

the order of a few thousands K (Ostorero et al. 2009).

Alternatively, a low covering fraction could be

responsible for the large X-ray to HI column density

ratio, although this explanation is less likely

given the large column densities measured in X-rays.

is of

the order of a few thousands K (Ostorero et al. 2009).

Alternatively, a low covering fraction could be

responsible for the large X-ray to HI column density

ratio, although this explanation is less likely

given the large column densities measured in X-rays.

![\begin{figure}

\par\mbox{\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{1284f16.ps} \includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{1284f17.ps} }\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/25/aa11284-08/Timg75.png) |

Figure 11: Left panel: 2-10 keV versus 5 GHz logarithmic ratio versus redshift for the GPS ( filled dots) and the FR II sample ( empty squares). The obliquely shaded box indicates the locus of the FR I Chandra sample; the horizontally shaded box the locus of the blazar sample of Fossati et al. (1998); the dot-dashed line the locus corresponding to a typical Spectral Energy Distribution of a radio-loud quasar after Elvis et al. (1994b). Right panel: 2-10 keV versus 5 GHz core luminosity for the GPS galaxies ( filled circles), and a control sample of radio galaxies (FR I: empty circles, FR II: empty squares). The lines represent the best-fit regression line for censored data for X-ray weak GPS ( continuous), FR I ( dashed) and FR II ( dashed-dotted). |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Holt et al. (2003) proposed an ``onion-skin'' model for

the nuclear environment gas in B1345+125, to explain the

reddening properties of the different components

of the optical lines. The jet would

pierce its way through a dense

cocoon of gas and dust, with decreasing density at larger

distances from the radio core. If this scenario would

apply to the whole class of GPS samples, and

X-ray and radio emission originate in the same

physical system, one

might expect an anti-correlation between the measured

column density and the size of the radio structure, with

a large scatter due to the unknown line-of-sight angles

distribution. This correlation

is shown in Fig. 10.

A censored fit on this data with a function:

![]() yields:

yields:

![]() ,

and

,

and

![]() ,

where

,

where

![]() is the size

of the radio structure in

units of kpc. This result is formally robust,

but admittedly mainly driven

by the two extreme data points. A confirmation of this

correlation by increasing the number of small (r < 100 pc)

and large (r > 1 kpc) objects

for which spectroscopic X-ray data are

available is a task we are actively pursuing.

Interestingly enough, an anti-correlation

between the linear dimension of the sub-galactic radio galaxy and

the radio HI column density was discovered by

Pihilstöm et al. (2003).

As already pointed out by Gupta et al. (2006), this

anti-correlation could be driven by small sources probing

gas closer to the AGN and hence at a higher spin

temperatures.

In this context, it is also interesting to observe that

GPS quasars exhibit no absorption (with upper limits

is the size

of the radio structure in

units of kpc. This result is formally robust,

but admittedly mainly driven

by the two extreme data points. A confirmation of this

correlation by increasing the number of small (r < 100 pc)

and large (r > 1 kpc) objects

for which spectroscopic X-ray data are

available is a task we are actively pursuing.

Interestingly enough, an anti-correlation

between the linear dimension of the sub-galactic radio galaxy and

the radio HI column density was discovered by

Pihilstöm et al. (2003).

As already pointed out by Gupta et al. (2006), this

anti-correlation could be driven by small sources probing

gas closer to the AGN and hence at a higher spin

temperatures.

In this context, it is also interesting to observe that

GPS quasars exhibit no absorption (with upper limits

![]() 1021 cm-2; Siemiginowska et al. 2008), as well

as diffuse emission associated with jets, binary structures or

embedding clusters.

The detection rate as well as the column density of HI

absorption increases with core prominence (Gupta & Saikia 2006).

The core prominence is a statistical indicator of the

orientation of the jet axis to the line of sight.

On the average HI absorbers are more common

and exhibit larger column densities in galaxies than

in quasars. This can be explained if the HI

absorbing gas is distributed in a circumnuclear disk

much smaller than the size of the radio emitting

region, and only a small fraction of it is obscured in

objects at large inclinations.

1021 cm-2; Siemiginowska et al. 2008), as well

as diffuse emission associated with jets, binary structures or

embedding clusters.

The detection rate as well as the column density of HI

absorption increases with core prominence (Gupta & Saikia 2006).

The core prominence is a statistical indicator of the

orientation of the jet axis to the line of sight.

On the average HI absorbers are more common

and exhibit larger column densities in galaxies than

in quasars. This can be explained if the HI

absorbing gas is distributed in a circumnuclear disk

much smaller than the size of the radio emitting

region, and only a small fraction of it is obscured in

objects at large inclinations.

5.4 Radio-to-X-ray correlations

In the left panel of

Fig. 11 we compare the logarithmic ratio between the

2-10 keV and the core 5 GHz luminosity

(

![]() ,

where

,

where

![]() is the luminosity density at

5 GHz) for the

GPS and the control sample.

Values for the GPS sample

range between -0.5 and 1.5. No clear dependence on

redshift is observed.

GPS galaxies are X-ray under-luminous by about an

order of magnitude with respect to

their radio power once compared to FR II radio galaxies,

blazars (Fossati et al. 1998)

and radio-loud quasars (Elvis et al. 1994b).

On the other hand, the X-ray-to-radio luminosity ratios

in GPS galaxies well match

values observed in FR I galaxies:

is the luminosity density at

5 GHz) for the

GPS and the control sample.

Values for the GPS sample

range between -0.5 and 1.5. No clear dependence on

redshift is observed.

GPS galaxies are X-ray under-luminous by about an

order of magnitude with respect to

their radio power once compared to FR II radio galaxies,

blazars (Fossati et al. 1998)

and radio-loud quasars (Elvis et al. 1994b).

On the other hand, the X-ray-to-radio luminosity ratios

in GPS galaxies well match

values observed in FR I galaxies:

![]() .

It is important to

stress again that there is almost no overlap in redshift

between the GPS and the FR I samples, though.

.

It is important to

stress again that there is almost no overlap in redshift

between the GPS and the FR I samples, though.

The interpretation of X-ray-to-radio luminosity

correlation depends on the origin of the bulk of the

VLA radio emission in compact galaxies. VLBI

observations of GPS galaxies unveiled a fraction

of Compact Symmetric Objects (CSO) between ![]() 30%

and 100% (Stanghellini et al. 1997, 1999; Liu et al. 2007; Xiang et al. 2005).

Three objects in our sample exhibit a CSO

morphology: PKS 0050+019, PKS 1345+125, and PKS 2008-068

(Stanghellini et al. 1997, 1999), although in all

these cases the morphology is rather complex, with

multiple component on scales

30%

and 100% (Stanghellini et al. 1997, 1999; Liu et al. 2007; Xiang et al. 2005).

Three objects in our sample exhibit a CSO

morphology: PKS 0050+019, PKS 1345+125, and PKS 2008-068

(Stanghellini et al. 1997, 1999), although in all

these cases the morphology is rather complex, with

multiple component on scales

![]() 20 pc.

High-resolution, multi-frequency observations of

our sample would be required to

ultimately estimate which fraction of the VLA flux

can be safely attributed to a core.

20 pc.

High-resolution, multi-frequency observations of

our sample would be required to

ultimately estimate which fraction of the VLA flux

can be safely attributed to a core.

From Fig. 11 a possible bimodality of the

X-ray-to-radio luminosity ratio in the GPS sample is apparent.

The fit of the

cumulative distribution function of this quantity with a single

Gaussian yields a Kolmogornov/Smirnov value of 0.33,

corresponding to null hypothesis probability of about

4%. A fit with a double Gaussian yields instead a value of

0.18, with a null hypothesis probability of 65%.

We consider this as a tentative piece of evidence for

bimodality only.

We will refer in the following to ``X-ray bright'' and

to ``X-ray weak'' GPS galaxies as those, whose

![]() ratio is larger/smaller than 0.5,

respectively.

No significant difference in the spectral shape

between the the ``X-ray bright'' and ``X-ray weak'' sources was

observed. In particular, the obscuring column density

distributions are indistinguishable.

ratio is larger/smaller than 0.5,

respectively.

No significant difference in the spectral shape

between the the ``X-ray bright'' and ``X-ray weak'' sources was

observed. In particular, the obscuring column density

distributions are indistinguishable.

In the right panel of

Fig. 11 the 2-10 keV luminosity

is plotted against the 5 GHz luminosity. In FR I galaxies

a strong correlation between core X-ray, radio and

optical flux is known (Hardcastle & Worrall 2000; Chiaberge et al. 1999).

In our control sample, the slope of this correlation

is consistent with unity:

![]() .

Interestingly enough, this slope is consistent

with the slope observed in ``X-ray weak'' GPS galaxies

.

Interestingly enough, this slope is consistent

with the slope observed in ``X-ray weak'' GPS galaxies

![]() ,

with a

,

with a ![]() 0.5 dex

offset at face-value. The ``X-ray bright'' sample

exhibits a significantly flatter slope, although

with large uncertainties (

0.5 dex

offset at face-value. The ``X-ray bright'' sample

exhibits a significantly flatter slope, although

with large uncertainties (

![]() ).

Again, it is hard to estimate any bias associated with

the coarse spatial resolution of the GPS radio measurements.

).

Again, it is hard to estimate any bias associated with

the coarse spatial resolution of the GPS radio measurements.

6 Discussion

In this section we will review the main X-ray observational properties of our whole GPS sample, trying to address the three issues which originally motivated our study:

- What is the physical origin of the X-ray emission

in GPS galaxies?

- Which physical system is associated with the X-ray obscuration?

- What is the ``endpoint'' of the evolution of

compact radio sources?

6.1 X-ray spectral support for an accretion-disk origin

The distribution of spectral indices in the GPS sample

by itself does

not provide any stringent constraints

on the origin of X-ray emission

in GPS galaxies. The

mean value,

![]() (

(

![]() ), is consistent

with spectral components associated with the jet

in radio galaxies

(

), is consistent

with spectral components associated with the jet

in radio galaxies

(

![]() ), as well as with

accretion (

), as well as with

accretion (

![]() ,

Evans et al. 2006), although is nominally closer to the latter.

A possible clue may come from the fact that

the column density measured in X-rays is invariably

larger by 1-2 orders of magnitudes than that measured

in radio. This finding could be naturally explained

by X-rays being produced in a smaller region than the radio.

On the average, the radio morphology of compact radio sources

strikingly resembles that of large-scale radio doubles,

although on a scale which is entirely confined within

the optical narrow-line emission regions.

Radio emission traces therefore

the radio hotspot and lobes. X-rays could be instead

generated by the base of the jet, or

by the accretion disk.

,

Evans et al. 2006), although is nominally closer to the latter.

A possible clue may come from the fact that

the column density measured in X-rays is invariably

larger by 1-2 orders of magnitudes than that measured

in radio. This finding could be naturally explained

by X-rays being produced in a smaller region than the radio.

On the average, the radio morphology of compact radio sources

strikingly resembles that of large-scale radio doubles,

although on a scale which is entirely confined within

the optical narrow-line emission regions.

Radio emission traces therefore

the radio hotspot and lobes. X-rays could be instead

generated by the base of the jet, or

by the accretion disk.

Support for the X-rays arising from a relatively compact region

comes from the comparison

with radio-quiet AGN. Once a similar baseline

model is employed, Seyfert Galaxies have:

![]() (Bianchi et al., submitted)

(Bianchi et al., submitted)![]() .

GPS galaxy X-ray spectra

lack the complexity that Seyferts typically exhibit. There

is no strong evidence for a soft excess (with the

only exception of OQ+208, Guainazzi et al. 2004), warm absorber,

warm scattering or Fe K

.

GPS galaxy X-ray spectra

lack the complexity that Seyferts typically exhibit. There

is no strong evidence for a soft excess (with the

only exception of OQ+208, Guainazzi et al. 2004), warm absorber,

warm scattering or Fe K![]() fluorescent emission

(with, again, the notable exceptions of OQ+208 and,

possibly PKS1607+26) in our sample. However, most of the GPS galaxy

spectra collected so far with either XMM-Newton or

Chandra do not possess the statistical quality that

would be needed for these additional spectral features to

be unambiguously detected.

fluorescent emission

(with, again, the notable exceptions of OQ+208 and,

possibly PKS1607+26) in our sample. However, most of the GPS galaxy

spectra collected so far with either XMM-Newton or

Chandra do not possess the statistical quality that

would be needed for these additional spectral features to

be unambiguously detected.

The scatter in the X-ray to radio luminosity ratio, and its lack of dependency with source size and age (cf. also Fig. 13) may indicate a link between accretion disk and jet activity primarily driven by disk instabilities. 10-20% of GPS objects exhibit very extended radio (Stanghellini et al. 1990; Baum et al. 1990; Schoenmakers et al. 1999; Marecki et al. 2003) or X-ray (Siemiginowska et al. 2002, 2003) emission. These components have been interpreted as remnants of past enhanced activity. A similar behaviour on much shorter time scales is observed in Galactic Black Hole Candidates and micro-quasars, such as GRS 1915+105 (Fender et al. 2004; Belloni et al. 2000). Jet blobs are supposed to be fed by the evacuation of the innermost accretion disk regions. This mechanism yields alternating X-rays- (disk-dominated) and radio-bright (jet blob-dominated) phases. Models based on disk radiation pressure instabilities reproduce well the timescales of these transitions (Czerny et al., in preparation), although they don't make specific predictions on the evolution of the spectral energy distribution yet.

6.2 Dilution by X-rays from radio-emitting regions?

Most likely, the baseline model is indeed too simple. X-ray absorption could be ``diluted'' by X-rays coming from the high surface-brightness radio components, thus complicating the interpretation of the results derived by our simple baseline model. This scenario would also explain the (still tentative) anti-correlation between the X-ray column density and the size of the radio source (Fig. 10). In larger sources, a larger fraction of the X-ray emission associated with the radio hot-spots or lobes may be visible beyond the rim of the obscuring matter. Should this indeed be the case, we should, however, observe deviations from a simple power-law spectral shape. We indeed observe a soft excess in the radio-loud Compton-thick GPS galaxy OQ+208. This is the closest object in our sample, and the only one where high-resolution spatially-resolved spectroscopy with Chandra could provide direct observational clues on the physical location of the X-ray emitting plasma.

6.3 The X-ray obscuring environment

Lacking other direct pieces of evidence from X-rays alone, one may use multiwavelength diagnostics to obtain further clues on the origin of the X-ray emission in GPS galaxies. A well established diagnostic tool for X-ray obscuration in radio-quiet AGN involves the comparison between the column density measured in X-rays the absorption-corrected ratio of X-ray to O [III] fluxes (Maiolino et al. 1998). In the context of Seyfert galaxies, this diagram is used to calibrate the latter quantity as an estimator for obscuration. We use here the same plot with a different purpose, namely to test whether the ionising continuum powering the Narrow Line Regions in GPS galaxies has the same properties as in Seyfert galaxies once normalised to the X-ray primary emission. If this is the case, one may conclude that the ``normalising primary continua'' share the same properties in the two populations. The results of this comparison are shown in Fig. 12. 5 objects in our GPS sample have spectroscopic O [III] measurements (O'Dea 1998; Labiano et al. 2005, 2008, and references therein). The ``control sample'' is a collection of Seyfert 2-galaxies measurements in Guainazzi et al. (2005). The agreement is good. Although more GPS data would be required to ensure a homogeneous coverage of this plane, this piece of evidence further points towards an accretion origin for the X-ray emission in GPS galaxies.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm]{1284f18.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/25/aa11284-08/Timg91.png) |

Figure 12: X-ray column density versus the ratio between the absorption-corrected 2-10 keV and the O [III] fluxes. The filled squares are the 5 GPS galaxies in our sample for which O [III] measurements are available; the empty circles represent a sample of Seyfert 2 galaxies after Guainazzi et al. (2005). |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Interestingly, the fraction of Compton-thick AGN in the

GPS sample (

![]() ,

if PKS1607+26 is

considered) is comparable to fractions observed

in radio-quiet AGN (Heckman et al. 2005).

Conversely, only one Compton-thick

AGN has been detected in large-scale radio

galaxies (Erlund et al. 2008), although FR II exhibit typically

spectral components with very large obscuration

(Evans et al. 2006; Belsole et al. 2006).

,

if PKS1607+26 is

considered) is comparable to fractions observed

in radio-quiet AGN (Heckman et al. 2005).

Conversely, only one Compton-thick

AGN has been detected in large-scale radio

galaxies (Erlund et al. 2008), although FR II exhibit typically

spectral components with very large obscuration

(Evans et al. 2006; Belsole et al. 2006).

6.4 X-ray emission entirely associated with radio-emitting regions?

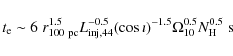

We now investigate the implications of the difference between X-ray

and radio H I column densities, possibly due

to the ionisation state of a single gas system

covering simultaneously the radio and the X-ray

emission.

Attributing this difference solely to ionisation effects would

mean ionisation fractions of 90% to 99% (see the discussion

in Vink et al. 2005). Photoionisation simulations with CLOUDY

(Ferland et al. 1998) show that this corresponds to

an ionisation parameter

![]() 20 for a gaseous nebula photoionised by a typical AGN continuum. An anti-correlation between the HI column density

and the linear projected size of the radio source

is now well established (Pihlström et al. 2003; Gupta & Saikia 2006; Vermeulen et al. 2003).

Smaller sources (<0.5 kpc)

tend to have larger H I column density than

larger sources (>0.5 kpc).

If not driven by uncertainties in the

spin temperature of the H I absorbing gas, this

anticorrelation can be explained by GPS galaxies hosting young

radio sources, which evolve in a disk distribution of

gas with a power-law radial density dependence. The same

explanation could lay behind the (tentative)

anti-correlation between X-ray column density

and radio size in GPS galaxies (Fig. 10).

One can assume a scenario where the radio and

X-ray source are seen through the same line-of-sight

and are both embedded in a screen of ionised gas, responsible

for X-ray photoelectric absorption as well as for radio

free-free absorption. From the definition of

ionisation parameter, it follows for the X-ray

regime:

20 for a gaseous nebula photoionised by a typical AGN continuum. An anti-correlation between the HI column density

and the linear projected size of the radio source

is now well established (Pihlström et al. 2003; Gupta & Saikia 2006; Vermeulen et al. 2003).

Smaller sources (<0.5 kpc)

tend to have larger H I column density than

larger sources (>0.5 kpc).

If not driven by uncertainties in the

spin temperature of the H I absorbing gas, this

anticorrelation can be explained by GPS galaxies hosting young

radio sources, which evolve in a disk distribution of

gas with a power-law radial density dependence. The same

explanation could lay behind the (tentative)

anti-correlation between X-ray column density

and radio size in GPS galaxies (Fig. 10).

One can assume a scenario where the radio and

X-ray source are seen through the same line-of-sight

and are both embedded in a screen of ionised gas, responsible

for X-ray photoelectric absorption as well as for radio

free-free absorption. From the definition of

ionisation parameter, it follows for the X-ray

regime:

where

where

where

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm]{1284f19.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/25/aa11284-08/Timg101.png) |

Figure 13: X-ray to radio luminosity ratio versus the linear size for the sources of our GPS sample. The lines indicate the predictions of the Stawarz et al. (2008) model for jet kinetic powers ranging from 1044 erg s-1 to 1047 erg s-1. Dashed lines: power-law injection function (Fig. 2 in their paper); dotted lines: broken power-law injection function (Fig. 3 in their paper). |

| Open with DEXTER | |

If the compact jet ``drills'' its way through

such a medium, would it be significantly decelerated

or even ``frustrated'', i.e. permanently confined? This

issue was discussed by Guainazzi et al. (2004) for

the case of the Compton-thick absorber in OQ+208.

They concluded that for large inclination angles or

large thickness of the Compton-thick layer, the jet

could have been significantly decelerated by the interaction

with the ambient medium. Although permanent confinement

is unlikely in OQ+208, underestimating the evolution time scale

by one-two orders of magnitude is possible. Let's revise

their argument for the whole sample of GPS galaxy.

The expansion time for a jet propagating under

pressure equilibrium through an homogeneous medium can

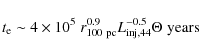

be expressed as (Carvalho 1985,1998; Scheuer 1974):

where

where we have compacted all the geometrical factors in the variable

6.5 Evolution of GPS sources

If the jet can indeed survive its eventful youth, and grow to reach a full level of kpc-scale maturity and beyond, what would it look like? The radio-to-X-ray luminosity plane does not ultimately elucidate the possible connection between GPS and ``mature'' radio galaxies. GPS galaxies are intriguingly well aligned along the extrapolation at high radio power of the correlation between radio core and X-ray luminosity valid for FR I radio galaxies (Evans et al. 2006). This correlation was proposed as a piece of evidence supporting a jet origin of unabsorbed X-ray spectral components in FR I radio galaxies. On the other hand, GPS galaxies have a comparable X-ray luminosity to FR IIs (cf. Fig. 11). In FR IIs, the obscured X-ray spectral component is probably associated with accretion onto the supermassive black hole obscured by a ``torus'', in analogy to the accepted paradigm applicable to radio-quiet AGN (Piconcelli et al. 2008). If the X-ray emission in GPS galaxies is due to accretion, the evolution of the radio and X-ray wavebands could be totally decoupled. Radio power would decline with the linear size (see, e.g., Fanti et al. 1995) while the sources expand through the ISM; at the same time the accretion disk would maintain a stable flow. At the end of their infancy, GPS galaxies would reach their glamorous maturity as FR II radio galaxies.

Evolutionary scenarios require that the radio luminosity

of GPS sources decreases with evolution, not

to exceed the number of observed FR II galaxies

(Readhead et al. 1996). Recently, Stawarz et al. (2008)

have proposed an evolutionary model for GPS sources,

which explicitly predicts the dependency of the

broadband Spectral Energy Distribution

on the source linear size. In their model

high-energy emission is produced by

upscattering of various photon fields

by the lobes' electrons. They predict a decrease of

the X-ray to radio luminosity ratio by 1-2 orders of

magnitude when the GPS source size increases

from 30 pc to 1 kpc. In Fig. 13

we compare this prediction with our observations. There is

no evidence for a strong anti-correlation between the

two quantities; the slope of the best linear fit is

![]() (1-

(1-![]() statistical error). Still,

the observational data are consistent with the Stawarz et al.

model predictions, if the GPS galaxies in our sample cover a wide

range in jet kinetic power.

statistical error). Still,

the observational data are consistent with the Stawarz et al.

model predictions, if the GPS galaxies in our sample cover a wide

range in jet kinetic power.

It is still impossible with the available data to

decide between an evolutionary scenario in which the

source evolves into a conventional FR II or FR I radio galaxy. To achieve this

goal, photometric X-ray observations of sizable samples of

low-luminosity (

![]() erg s-1)

GPS galaxies would be crucial. Fortunately, it is now

in principle possible to perform this experiment, thanks to

the point-like source sensitivity and scheduling flexibility of Chandra.

erg s-1)

GPS galaxies would be crucial. Fortunately, it is now

in principle possible to perform this experiment, thanks to

the point-like source sensitivity and scheduling flexibility of Chandra.

7 Summary and conclusions

The main scope of this paper is

reporting our current knowledge on

X-ray emission in GPS galaxies. For the first time a

complete radio-selected sample of GPS galaxies

has been almost entirely

observed with a modern X-ray observatory (mostly

with XMM-Newton). The sample

comprises all the z < 1 sources of the

Stanghellini et al. (1998) sample having a

5 GHz flux density

![]() 1 Jy. The main

results of our study can be summarised as follows:

1 Jy. The main

results of our study can be summarised as follows:

- We obtain a very large detection fraction;

all the sources of our sample yield a detection in

the soft X-ray band (0.5-2 keV), whereas 15 out of 16

are detected in the full band (0.5-10 keV).

- In almost all cases, a simple power law

modified by photoelectric absorption represents

an adequate description of the 0.5-10 keV spectrum.

In a few objects

the number of net counts is

not good enough to allow a full spectral analysis. In this case

basic spectral parameters were derived from hardness ratios

assuming the baseline model above.

- The mean of the spectral indices distribution

is

(

(

). Although the uncertainty

on this parameter is still too large

to pinpoint the physical mechanism

responsible for the observed X-ray emission, at face

value the

). Although the uncertainty

on this parameter is still too large

to pinpoint the physical mechanism

responsible for the observed X-ray emission, at face

value the  distribution is closer to

those AGN classes, whose

X-ray emission is believed to be dominated by accretion:

Seyfert Galaxies and the obscured spectral component in

FR II radio galaxies.

distribution is closer to

those AGN classes, whose

X-ray emission is believed to be dominated by accretion:

Seyfert Galaxies and the obscured spectral component in

FR II radio galaxies.

- We report the possible discovery of a Compton-thick

AGN in PKS1607+26.

Radio-loud Compton-thick AGN are still an

elusive population (Comastri 2004). Together

with OQ+208 - the other Compton-thick AGN in the sample -

PKS1607+26 is the only GPS galaxy where

an X-ray emission line has been detected,

possibly associated with Fe K

fluorescence.

fluorescence.

- X-ray spectra of GPS galaxies are significantly obscured.

The mean value of the column density distribution

(without PKS1607+26, due to pending uncertainties on

the identification of this source) is

cm-2 with a standard

deviation

cm-2 with a standard

deviation

dex.

Such a value is much larger than column densities measured in

a control sample of FR I radio galaxies, but still

less than column densities covering accretion-related

X-ray spectral components in FR II radio galaxies

(Evans et al. 2006; Balmaverde et al. 2006; Belsole et al. 2006).

dex.

Such a value is much larger than column densities measured in

a control sample of FR I radio galaxies, but still

less than column densities covering accretion-related

X-ray spectral components in FR II radio galaxies

(Evans et al. 2006; Balmaverde et al. 2006; Belsole et al. 2006).

- The X-ray column density measured in almost all GPS

galaxies is larger than the HI column density

measured in the radio by a factor 10 to 100.

This could be the signature of

physically different absorption

systems (Vink et al. 2005; Guainazzi et al. 2006)

or of a single system characterised by

a spin temperature

103 K (Ostorero et al. 2009).

We report a possible anti-correlation

between the projected linear size of the radio source

and the X-ray column density, analogous to the anti-correlation

between radio size and HI column density reported by

Pihlström et al. (2003) and Gupta et al. (2006).

103 K (Ostorero et al. 2009).

We report a possible anti-correlation

between the projected linear size of the radio source

and the X-ray column density, analogous to the anti-correlation

between radio size and HI column density reported by

Pihlström et al. (2003) and Gupta et al. (2006).

- GPS galaxies occupy a specific locus in the

radio versus X-ray luminosity plane. They lie well on the

extrapolation to high radio powers of

the correlation between these two quantities discovered in

low-luminosity FR I radio galaxies. On the

other hand, GPS galaxies exhibit a comparable X-ray

luminosity to FR II radio galaxies, notwithstanding their

much larger radio luminosity.

- GPS galaxies occupy the same locus as Seyfert

galaxies in the O[III] to X-ray luminosity ratio versus

X-ray column density diagnostic plane.

The evolutionary scenarios described above postulate

that GPS sources are young objects, as also indicated by

the direct measurement of their dynamical age.

Eventually GPS galaxies would

reach their full maturity as classical FR II radio galaxies.

However, column densities

![]() 1022 cm-2fully surrounding the expanding radio source could significantly

brake, if not entirely inhibit, this glazing future, leading

to a significant underestimate of dynamical ages based on

hotspots recession velocity measurements.

Extending the number of X-ray measurements of

low-luminosity (

1022 cm-2fully surrounding the expanding radio source could significantly

brake, if not entirely inhibit, this glazing future, leading

to a significant underestimate of dynamical ages based on

hotspots recession velocity measurements.

Extending the number of X-ray measurements of

low-luminosity (

![]() erg s-1) GPS galaxies is the next step we

intend to pursue, in order to pinpoint the endpoint of their

evolution.

erg s-1) GPS galaxies is the next step we

intend to pursue, in order to pinpoint the endpoint of their

evolution.

Appendix A: a serendipitous blazar in the field of 4C+00.02

A bright off-axis sources is visible in the EPIC field of view of the

XMM-Newton 4C+00.02 observation. This source will be referred in

the following as

XMMU J002200.8+000655. It is outside the field of view of the

XMM-Newton Optical Monitor.

The best-fit parameters when the baseline model is

applied to its spectrum are summarised in Table A.1.

The EW of a unresolved Fe K![]() neutral fluorescent line is

constrained to be lower than 400 eV.

neutral fluorescent line is

constrained to be lower than 400 eV.

Table A.1: Fitting results for XMMU J002200.8+000655.

This source was already known as 1RXS J002200.9+000659 (Voges et al. 1999). We have searched with Aladin for available measurements at other wavelengths. We have found data in GALEX GR4, SDSS (Adelman-McCarthy et al. 2008), 2MASS, and FIRST (White et al. 1997). In Fig. A.1 we compare the Spectral Energy Distribution (SED), with the average SED for radio-quiet and radio-loud quasars normalised at 1 keV (Elvis et al. 1994b) and with the ``blazar track'' corresponding to objects with the same radio luminosity as XMMU J002200.8+000655 (Fossati et al. 1998). As can be seen in Fig. A.1 the blazar SED track qualitatively agrees with the XMMU J002200.8+000655 SED. This source appears in NED as a BL Lac candidate, and in Véron-Cetty & Veron (2006) as a confirmed BL Lac object. Its optical spectrum was previously studied by Collinge et al. (2005), but heavy contamination by the host galaxy prevented its properties from being properly studied.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,angle=90]{1284f20.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/25/aa11284-08/Timg118.png) |

Figure A.1: The Spectral Energy Distribution (SED) for XMMU J002200.8+000655. The photometric points are compared with standard SED for Blazars (boxes, Fossati et al. 1998) and radio-quiet and radio-loud quasars (dotted line and solid line, respectively; Elvis et al. 1994a), normalised at the value of XMMU J002200.8+000655 at 1 keV. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Appendix B: Summary of the radio and X-ray properties of the whole GPS sample

In Table B.1 we report a summary of the X-ray properties of the whole GPS sample discussed in this paper, together with the 5 GHz luminosity after O'Dea (1998) and Stanghellini et al. (1998).

Table B.1: X-ray properties and radio luminosity of the whole GPS sample discussed in this paper (Sects. 5 and 6).

Acknowledgements

Based on observations obtained with XMM-Newton, an ESA science mission with instruments and contributions directly funded by ESA Member States and NASA This research has made use of data obtained through the High Energy Astrophysics Science Archive Research Centre Online Service, provided by the NASA/Goddard Space Flight Centre and of the NASA/IPAC Extragalactic Database (NED) which is operated by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, under contract with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. O.T. thanks the whole ESA administration, and in particular Nienke de Boer, Marcus Kirsch and Fernando Maura, for their support during a six-month traineeship at ESAC, where most of the data analysis included in this paper was performed. This research is funded in part by NASA grant NNX07AQ55G. O.T. gratefully acknowledge an ESA Internal Fellowship Trainee grant. A.S. is partly supported by NASA contract NAS8-39073. The authors thank C. Stanghellini for a critical revision of an early version of this manuscript. Last, but not least, the authors gratefully acknowledge a careful and accurate referee report by Dr. D. J. Saikia, which greatly improved the overall presentation of the paper, while allowing us to better clarify some aspects of the radio measurements discussed in this paper.

References

- Adelman-McCarthy, J. K., Agüeros, M. A, Allam, S. S., et al. 2008, ApJS, 175, 297 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Arnaud, K. A. 1996, Astronomical Data Analysis Software and Systems V, ed. G. Jacoby, J., & Barnes, ASP Conf. Ser., 101, 17 (In the text)

- Balmaverde, B., Capetti, A., & Grandi, P. 2006, A&A, 451, 35 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences]

- Baum, S. A., O'Dea, C. P., de Bruyn, A. G., & Murphy, D. W. 1990, A&A, 232, 19 [NASA ADS]

- Belloni, T., Migliari, S., & Fender, R. P. 2000, 358, L29

- Belsole, E., Worrall, D. M., & Hardcastle, M. J. 2006, MNRAS, 366, 339 [NASA ADS]

- Biretta, J. A., Schneider, D. P., & Gunn, J. E. 1985, AJ, 90, 2508 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, J. C. 1985, A&A, 150, 129 [NASA ADS]

- Carvalho, J. C. 1998, A&A, 329, 845 [NASA ADS]

- Cash, W. 1976, A&A, 52, 307 [NASA ADS] (In the text)

- Chiaberge, M., Capetti, A., & Celotti, A. 1999, A&A, 349, 77 [NASA ADS]

- Collinge, M.-J., Strauss, M.-A., Hall, P.-B., et al. 2005, AJ, 129, 2542 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Comastri, A. 2004, ASSL, 308, 245 [NASA ADS] (In the text)

- Donato, D., Sambruna, R. M., & Gliozzi, M. 2004, ApJ, 617, 915 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Elvis, M., Fiore, F., Wilkes, B., McDowell, J., & Bechtold, J. 1994a, ApJ, 422, 60 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Elvis, M., Wilkes, B. J., McDowell, J. C., et al. 1994b, ApJS, 95, 1 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Erlund, M. C., Fabian, A. C., Blundell, K. M., & Crawford, C. S. 2008, MNRAS, 385, L125 [NASA ADS] (In the text)

- Evans, D. A., Worrall, D. M., Hardcastle, M. J., Kraft, R. P., & Birkinshaw, M. 2006, ApJ, 642, 96 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Fanti, C., Fanti, R., Dallacasa, D., et al. 1995, A&A, 302, 317 [NASA ADS]

- Fender, R. P., Belloni, T. M., & Gallo, E. 2004, MNRAS, 355, 1105 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Ferland, G. J., Korista, K. T., Verner, D. A., et al. 1998, PASP, 110, 761 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Fossati, G., Maraschi, L., Celotti, A., Comastri, A., & Ghisellini, G. 1998, MNRAS, 299, 433 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Gabriel, C., Denby, M., Fyfe, D. J., Hoar, J., & Ibarra, A. 2003, in Astronomical Data Analysis Software and Systems XIII, ed. F. Ochsenbein, M. Allen, & D. Egret (San Francisco: ASP), ASP Conf. Ser., 314, 759 (In the text)

- Gopal-Krishna, Wiita P. J. 1991, ApJ, 373, 325 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Grandi, P., Malaguti, G., & Fiocchi, M. 2006, ApJ, 642, 113 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Guainazzi, M. 2008, Status of EPIC Calibrations, XMM-Newton SOC:ESAC, available at: http://xmm2.esac.esa.int/docs/documents/CAL-TN-0018.pdf

- Guainazzi, M., Siemiginowska, A., Rodriguez-Pascual, P., & Stanghellini, C. 2004, A&A, 421, 461 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences]

- Guainazzi, M., Matt, G., & Perola, G. C. 2005, A&A, 444, 119 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences]

- Guainazzi, M., Siemiginowska, A., Stanghellini, C., et al. 2006, A&A, 446, 87 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences]

- Gugliucci, N. E., Taylor, G. B., Peck, A. B., & Giroletti M. 2005, ApJ, 622, 136 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N., & Saikia, D. J. 2006, MNRAS, 370, 738 [NASA ADS] (In the text)

- Gupta, N., Salter, C. J., Saikia, D. J., Ghosh , T., & Jeyakumar, S. 2006, MNRAS, 373, 972 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Hardcastle, M. J., & Worrall, D. A. 2000, MNRAS, 314, 969 [CrossRef]

- Hardcastle, M. J., Evans, D. A., & Croston, J. H. 2006, MNRAS, 370, 1893 [NASA ADS]

- Heckman, T. M., Ptak, A., Hornschemeier, A., & Kauffmann, G. 2005, ApJ, 634, 161 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Holt, J., Tadhunter, C. N., & Morganti, R. 2003, MNRAS, 342, 227 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Kalberla, P. M. W., Burton, W. M., Hartmann, D., et al. 2005, A&A, 440, 775 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] (In the text)

- Isobe, T., Feigelson, E. D., & Nelson, P. I. 1986, ApJ, 306, 490 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Labiano, A., O'Dea, C., Gelderman, R., et al. 2005, A&A, 436, 493 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences]

- Labiano, A., O'Dea, C., Barthel, P. D., de Vries, W. H., & Baum, S. A. 2008, A&A, 477, 491 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences]

- Laing, R. A., Jenkins, C. R., Wall, J. V., & Unger, S. W. 1994, in The First Stromlo Symposium: The Physics of Active Galactic Nuclei, ed. G. V. Bicknell, M. A. Dopita, & P. A. Quinn, ASP Conf. Ser., 54, 201 (In the text)

- Lister, M. 2003, ASPC, 300, 71 [NASA ADS]

- Liu, X., Fuo, W.-F., Shi, W.-Z., & Song, H.-G. 2007, A&A, 470, 97 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences]

- Magdziarz, P., & Zdziarski, A. A. 1995, MNRAS 273, 837

- Marecki, A., Barthel, P. D., Polatidis, A., & Owsianik, I. 2003, PASA, 20, 16 [NASA ADS]

- Maiolino, R., Salvati, M., Bassani, L., et al. 1998, A&A, 338, 781 [NASA ADS] (In the text)

- Mazzarella, J. M., Bothun, G. D., & Boroson, T. A. 1991, AJ, 101, 2034 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, R., & McCammon, D. 1983, ApJ, 270, 199 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Murgia, M. 2003, PASA, 20, 19 [NASA ADS]

- O'Dea, C. 1998, PASP, 110, 493 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- O'Dea, C., Baum, S. A., & Stanghellini, C. 1991, ApJ, 380, 66 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- O'Dea, C., Stanghellini, C., Baum, S., & Charlot, S. 1996, ApJ, 470, 806 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- O'Dea, C., de Vries, W. H., Worrall, D. M., Baum, S., & Koekmoer, A. 2000, AJ, 119, 478 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- O'Dea, C., Mu, B., Worrall, D. M., et al. 2006, ApJ, 653, 1115 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Osterbrock, D. E. 1977, ApJ, 215, 733 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Ostorero, L., Moderski, R., Stawarz, , et al. 2009, AN, 330, 275 [NASA ADS] (In the text)

- Phillips, R. B., & Shaffer, D. B. 1983, ApJ, 271, 32 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Piconcelli, E., Bianchi, S., Miniutti, G., et al. 2008, A&A, 480, 671 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] (In the text)

- Pihlström, Y. M., Conway, J. E., & Vermeulen, R. C. 2003, A&A, 404, 871 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] (In the text)

- Polatidis, A. G., & Conway, J. E. 2003, PASA, 20, 69 [NASA ADS]

- Readhead, A. C. S., Taylor, G. B., Pearson, T. J., & Wilkinson, P. N. 1996, ApJ, 460, 634 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Risaliti, G. 2002, A&A, 386, 379 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences]

- Sambruna, R., Eracleous, M., & Mushotzky, R. 1999, ApJ, 526, 60 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Schoenmakers, A. P., de Bryun, A. G., Röttgering, H. J. A., & van der Laan, H. 1999, A&A, 341, 44 [NASA ADS]

- Scheuer, P. A. G. 1974, MNRAS, 166, 513 [NASA ADS]

- Schmitt, J. H. M. M. 1985, A&A, 293, 178 [NASA ADS]

- Siemiginowska, A., Bechtold, J., Aldcroft, T. L., et al. 2002, ApJ, 570, 543 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Siemiginowska, A., Stanghellini, C., Brunetti, G., et al. 2003, ApJ, 595, 643 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Siemiginowska, A., Cheung, C. C., LaMassa, S., et al. 2005, ApJ, 632

- Siemiginowska, A., LaMassa, S., Aldcroft, T. L., Bechtold, J., & Elvis, M. 2008, 684, 811 (In the text)

- Spergel, D. N., Bean, R., Doré, O., et al. 2007, ApJS, 170, 377 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Stanghellini, C. 2006, in Proceedings of the 8th VLBI Network Symposium, ed. A. Marecki et al., 18

- Stanghellini, C., Baum, S. A., O'Dea, C. P., & Morris, G. B. 1990, A&A, 233, 379 [NASA ADS]

- Stanghellini, C., O'Dea, C. P., Baum, S. A., et al. 1997, A&A, 325, 953 [NASA ADS]

- Stanghellini, C., O'Dea, C. P., Dallacasa, D., et al. 1998, A&AS, 131, 303 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences]

- Stanghellini, C., O'Dea, C. P., & Murphy, D. W. 1999, A&ASS, 134, 309 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Stawarz, ., Ostorero, L., Begelman, M. C., et al. 2008, ApJ, 680, 911 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Strüder, L., Briel, U., Dannerl, K., et al. 2001, A&A, 365, L18 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] (In the text)

- Turner, M. J. L., Abbey, A., Arnaud, M., et al. 2001, A&A, 365, L27 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] (In the text)

- Vermeulen, R. C., Pihlström, Y. M., Tschager, W., et al. 2003, A&A, 404, 861 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences]

- Véron-Cetty,

M.-P., & Veron, P. 2006, A catalogue of quasars and active

nuclei: 12

edition

edition

- Vink, J., Snellen, I., Mack, K.-H., & Schillizzi, R. 2005, MNRAS, 367, 928 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Voges, W., Aschenbach, B., Boller, T., et al. 1999, A&AS, 349, 389 [NASA ADS] (In the text)

- White, R.-L., Becker, R.-H., Helfand, D.-J., & Gregg, M.-D. 1997, ApJ, 475, 479 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Xiang, L., Dallacasa, R., Cassaro, P., Jiang, D., & Reynolds, C. 2005, 434, 123

Footnotes

- ...

(2006)

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- Guainazzi et al. (2006) present also data of COINSJ0029+3456; this source was later discovered to host a blazar, and won't be considered in the sample discussed in this paper.

- ... catalogue)

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- http://nedwww.ipac.caltech.edu/

- ...(Kalberla et al. 2005)

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- http://heasarc.gsfc.nasa.gov/cgi-bin/Tools/w3nh/ w3nh.pl

- ... matter

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- On an ``historical'' note, the GPS galaxy OQ+208 was the first radio-loud Compton-thick AGN ever discovered (Guainazzi et al. 2004).

- ... sample

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- 4C+32.44, 4C+62.22, B03710+439, COINSJ2355+4950,

PKS0500+019, PKS1345+125, PKS2127+04, OQ+208. - ... submitted)