| Issue |

A&A

Volume 521, October 2010

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A66 | |

| Number of page(s) | 10 | |

| Section | Interstellar and circumstellar matter | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201015039 | |

| Published online | 21 October 2010 | |

Dust grain growth in  -Ophiuchi protoplanetary disks

-Ophiuchi protoplanetary disks

L. Ricci1 - L. Testi1 - A. Natta2 - K. J. Brooks3

1 - European Southern Observatory,

Karl-Schwarzschild-Strasse 2, 85748 Garching, Germany

2 -

INAF-Osservatorio Astrofisico di Arcetri, Largo Fermi 5, 50125 Firenze, Italy

3 - Australia Telescope National Facility, PO Box 76, Epping, NSW 1710, Australia

Received 25 May 2010 / Accepted 5 August 2010

Abstract

We present new ATCA observations at 3.3 mm of 27 young stellar objects in the ![]() -Oph

young cluster. 25 of these sources have been detected. We analyze the

sub-millimeter and millimeter SED for a subsample of 17 isolated

class II protoplanetary disks and derive constraints on the grain

growth and total dust mass in the disk outer regions. All the disks in

our sample show a mm slope of the SED which is significantly shallower

than the one observed for the ISM at these long wavelengths. This

indicates that 1) class II disks in Ophiuchus host grains

grown to mm/cm-sizes in their outer regions; 2) formation of

mm/cm-sized pebbles is a fast process and 3) a mechanism

halting or slowing down the inward radial drift of solid particles is

required to explain the data. These findings are consistent with

previous results in other star forming regions. We compare the dust

properties of this sample with those of a uniformly selected sample in

Taurus-Auriga and find no statistical evidence of any difference in

terms of grain growth between the two regions. Finally, in our sample

the mm slope of the SED is not found to correlate with indicators of

grain growth to micron sizes in the surface layers of the inner disk.

-Oph

young cluster. 25 of these sources have been detected. We analyze the

sub-millimeter and millimeter SED for a subsample of 17 isolated

class II protoplanetary disks and derive constraints on the grain

growth and total dust mass in the disk outer regions. All the disks in

our sample show a mm slope of the SED which is significantly shallower

than the one observed for the ISM at these long wavelengths. This

indicates that 1) class II disks in Ophiuchus host grains

grown to mm/cm-sizes in their outer regions; 2) formation of

mm/cm-sized pebbles is a fast process and 3) a mechanism

halting or slowing down the inward radial drift of solid particles is

required to explain the data. These findings are consistent with

previous results in other star forming regions. We compare the dust

properties of this sample with those of a uniformly selected sample in

Taurus-Auriga and find no statistical evidence of any difference in

terms of grain growth between the two regions. Finally, in our sample

the mm slope of the SED is not found to correlate with indicators of

grain growth to micron sizes in the surface layers of the inner disk.

Key words: protoplanetary disks - planets and satellites: formation - stars: pre-main sequence

1 Introduction

Circumstellar disks around pre-main sequence (PMS) stars are the common birth places of planetary systems. In order to build up large bodies such as giant planets a huge growth of solid particles by more than 12 orders of magnitude in size has to occur starting from submicron-sized microscopic dust grains as those typically found in the interstellar medium (ISM; Mathis et al. 1977). The first stages of this process of grain growth are characterized by the dynamical interaction between gas and dust, leading to collisions between the solid particles and finally coagulation (see Beckwith et al. 2000; Dominik et al. 2007; Natta et al. 2007).

Evidence for the presence of micron-sized dust grains in protoplanetary disks has been provided by the inspection of ISO and Spitzer spectra for the silicate feature at about 10 ![]() m (e.g. Bouwman et al. 2001; Van Boeckel et al. 2003; Kessler-Silacci et al. 2006).

However infrared observations can only probe the uppermost surface

layers of the disk, while to investigate the properties of dust in the

disk midplane, where planet formation is expected to take place,

observations at longer wavelengths are needed. If the long-wave

emission is optically thin the spectral index of the SED at these

wavelengths can be related to the spectral index of the dust opacity

m (e.g. Bouwman et al. 2001; Van Boeckel et al. 2003; Kessler-Silacci et al. 2006).

However infrared observations can only probe the uppermost surface

layers of the disk, while to investigate the properties of dust in the

disk midplane, where planet formation is expected to take place,

observations at longer wavelengths are needed. If the long-wave

emission is optically thin the spectral index of the SED at these

wavelengths can be related to the spectral index of the dust opacity ![]() (

(

![]() ), and

), and ![]() -values lower than

-values lower than ![]() 1 are naturally interpreted in terms of grain growth (Draine 2006). Beckwith & Sargent (1991)

were the first to show that T Tauri stars (TTS) have SEDs at

submillimeter wavelengths which are typically shallower than what found

for the ISM, suggesting that dust grains as large as at least 1 mm

are present in the disk midplane. However these single-dish

observations did not have a good enough angular resolution to spatially

resolve the disks, and the same data could in principle be explained

also by optically thick emission from compact disks with unprocessed,

ISM-like grains.

1 are naturally interpreted in terms of grain growth (Draine 2006). Beckwith & Sargent (1991)

were the first to show that T Tauri stars (TTS) have SEDs at

submillimeter wavelengths which are typically shallower than what found

for the ISM, suggesting that dust grains as large as at least 1 mm

are present in the disk midplane. However these single-dish

observations did not have a good enough angular resolution to spatially

resolve the disks, and the same data could in principle be explained

also by optically thick emission from compact disks with unprocessed,

ISM-like grains.

Wilner et al. (2000) and Testi et al. (2003)

resolved the disks around TW Hya and CQ Tau PMS stars at 7 mm with

the Very Large Array (VLA), confirming that the long-wave emission from

these disks reveals the presence of cm-sized pebbles in the disk

midplane. More recently Rodmann et al. (2006) and Lommen et al. (2007) found evidence of grain growth to ![]() mm/cm-sized

pebbles for about ten T Tauri stars in the Taurus-Auriga,

Chamaeleon and Lupus star forming regions (SFRs). Lommen

et al. (2010) have

combined new and literature data for disks from five different SFRs

(Taurus-Auriga, Lupus, Chamaeleon, Corona Australis and Serpens) and

reported a tentative correlation between the mm slope of the SED and

the strength of the 10-

mm/cm-sized

pebbles for about ten T Tauri stars in the Taurus-Auriga,

Chamaeleon and Lupus star forming regions (SFRs). Lommen

et al. (2010) have

combined new and literature data for disks from five different SFRs

(Taurus-Auriga, Lupus, Chamaeleon, Corona Australis and Serpens) and

reported a tentative correlation between the mm slope of the SED and

the strength of the 10-![]() m silicate feature, possibly suggesting that inner and outer disk evolve simultaneously in terms of dust grain growth.

m silicate feature, possibly suggesting that inner and outer disk evolve simultaneously in terms of dust grain growth.

So far, most of the observations carried out at long wavelengths have targeted the brightest sources. Ricci et al. (2010, hereafter R10) have started to probe fainter disks with new sensitive data at 3 mm obtained with the Plateau de Bure Interferometer in Taurus and analyzed a sample of 21 isolated class II young stellar objects (YSOs) in this SFR. For all the disks in this sample they found neither evidence for time evolution of dust grain growth nor significant relations between dust properties and stellar ones were found.

In this paper we perform the same analysis presented in R10, but on a sample of disks in another SFR, i.e. ![]() -Ophiuchi. In Sect. 2 we present new 3 mm data for 27

-Ophiuchi. In Sect. 2 we present new 3 mm data for 27 ![]() -Oph YSOs obtained with the Australia Telescope Compact Array (ATCA

-Oph YSOs obtained with the Australia Telescope Compact Array (ATCA![]() )

and its new Compact Array Broadband Backend (CABB). In Sect. 3 we

describe the properties of the sub-sample used for the analysis. The

method adopted for deriving the dust properties, namely grain growth

and dust mass, is the same used in R10 and it is described in

Sect. 4. The results of the analysis are described in

Sect. 5, whereas Sect. 6 summarizes the main findings of our

work.

)

and its new Compact Array Broadband Backend (CABB). In Sect. 3 we

describe the properties of the sub-sample used for the analysis. The

method adopted for deriving the dust properties, namely grain growth

and dust mass, is the same used in R10 and it is described in

Sect. 4. The results of the analysis are described in

Sect. 5, whereas Sect. 6 summarizes the main findings of our

work.

Table 1: Summary of the 3.3 mm ATCA observations.

2 New ATCA observations

We observed 27 YSOs in the ![]() -Oph

star forming region at 3.2944 mm with ATCA and the new CABB

digital filter bank. Targets were chosen by being class II (most

of them) or ``flat spectrum'' YSOs, with a detected flux at 1.3 mm

higher than 20 mJy in order to have good chances for

detection at

-Oph

star forming region at 3.2944 mm with ATCA and the new CABB

digital filter bank. Targets were chosen by being class II (most

of them) or ``flat spectrum'' YSOs, with a detected flux at 1.3 mm

higher than 20 mJy in order to have good chances for

detection at ![]() 3.3 mm with a few hours at most of integration time on-source.

3.3 mm with a few hours at most of integration time on-source.

The observations were carried out between the end of April and the

beginning of July 2009, with the ATCA array in the H168 and H75

configurations respectively. The obtained FWHM of the synthesized beam of ![]() 3-7''

did not allow us to spatially resolve any of our sources, and so a

2D-Gaussian model was used to estimate the flux density in the

continuum at 3.3 mm. To obtain the best sensitivity in the

continuum we set the correlator to cover the full 2-GHz CABB effective

bandwidth on all the five antennas available at

3-7''

did not allow us to spatially resolve any of our sources, and so a

2D-Gaussian model was used to estimate the flux density in the

continuum at 3.3 mm. To obtain the best sensitivity in the

continuum we set the correlator to cover the full 2-GHz CABB effective

bandwidth on all the five antennas available at ![]() 3 mm.

Each source has been observed one or more times, with a total

integration time on-source ranging between about 40 min and

3 h.

3 mm.

Each source has been observed one or more times, with a total

integration time on-source ranging between about 40 min and

3 h.

The complex gain calibration was done on the calibrators 1622-297 and

1730-130, and science targets were typically observed for 10 min

and then spaced out with 2 min on the gain calibrator.

The absolute calibration was done with Uranus except for a few times in

which 1921-293 was used and then its flux was always cross-calibrated

with Uranus the day after. In general, the baselines that resolved out

Uranus were not used for flux calibration![]() . In this work, we assume a 1

. In this work, we assume a 1![]() -uncertainty on the calibrated flux of about 25

-uncertainty on the calibrated flux of about 25![]() .

.

The results of the observations are reported in Table 1.

In particular we have detected 25 out of 27 targeted YSOs. The

detected sources have fluxes ranging from about 1.5 and

48.8 mJy at 3.3 mm.

For the two undetected sources, IRS 33 and GY 284, we obtained an upper

limit for the flux at 3.3 mm of 1.2 mJy. These sources have

been previously detected by Motte et al. (1998) using the IRAM 30 m single-dish telescope at 1.3 mm. Although their reported fluxes are relatively large (

![]() mJy and

mJy and

![]() mJy

for IRS 33 and GY 284 respectively) the emission for both the

sources appears to be spatially resolved by a beam with a FWHM

of about 11 arcsec. This indicates that a significant fraction of

the collected flux at 1.3 mm comes from an extended envelope

surrounding the circumstellar disk. In order to get a reliable estimate

for the flux at

mJy

for IRS 33 and GY 284 respectively) the emission for both the

sources appears to be spatially resolved by a beam with a FWHM

of about 11 arcsec. This indicates that a significant fraction of

the collected flux at 1.3 mm comes from an extended envelope

surrounding the circumstellar disk. In order to get a reliable estimate

for the flux at ![]() 1 mm from the circumstellar disk only, interferometric observations at

1 mm from the circumstellar disk only, interferometric observations at ![]() 1 mm

are needed to filter out the contaminating emission from the envelope.

Since these are not available in the literature we do not include

IRS 33 and GY 284 in our sample discussed in the next

section.

1 mm

are needed to filter out the contaminating emission from the envelope.

Since these are not available in the literature we do not include

IRS 33 and GY 284 in our sample discussed in the next

section.

3 Sample

In this section we describe some properties of the sample considered for our analysis![]() . In Sect. 3.1 we outline the selection criteria adopted to select our sample, Sect. 3.2 describes the sample completeness level, and finally in Sect. 3.3 we derive the stellar parameters.

. In Sect. 3.1 we outline the selection criteria adopted to select our sample, Sect. 3.2 describes the sample completeness level, and finally in Sect. 3.3 we derive the stellar parameters.

3.1 Selection criteria

We used the same selection criteria adopted in R10:

- 1.

- class II YSOs as catalogued in Andrews & Williams (2007a) from the infrared SED to avoid contamination of (sub-)mm fluxes by a residual envelope;

- 2.

- central stars need to be well characterized through optical-NIR spectroscopic/photometric data to obtain self-consistent disk SED models;

- 3.

- YSOs with at least one detection in the

mm spectral range

mm spectral range![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png) other than being observed through the new ATCA observations described

in Sect. 2, to have a good sampling of the (sub-)mm SED;

other than being observed through the new ATCA observations described

in Sect. 2, to have a good sampling of the (sub-)mm SED; - 4.

- no evidence of stellar companions with projected physical

separation between 5 and 500 AU to avoid tidal interactions that

may alter the outer disk structure; adopting for all the YSOs in our

sample the current estimate of

130 pc for the distance to the

130 pc for the distance to the  -Oph star forming region (Wilking et al. 2008; Lombardi et al. 2008), the range in projected phyical separation translates into a range in angular separation of

-Oph star forming region (Wilking et al. 2008; Lombardi et al. 2008), the range in projected phyical separation translates into a range in angular separation of  0.05-4''.

0.05-4''.

3.2 Completeness

The two histograms in Fig. 1 show the distribution of the ``isolated'', i.e. satisfying the selection criterion (4) in Sect. 3.1, class II YSOs from the Andrews & Williams (2007a) catalogue. The histogram on the left side shows that our sample comprises all the isolated class II YSOs with

![]() mJy, while for the fainter objects the completeness level reduces to 22% (8/36).

mJy, while for the fainter objects the completeness level reduces to 22% (8/36).

Table 2: Stellar properties of the considered sample.

In terms of the stellar properties, our sample includes 53% (16/30) of the isolated PMS stars with stellar types equal to or earlier than M1, correspondent to a stellar mass larger than3.3 Stellar properties

To constrain the stellar properties we used the same method as

described in R10. We estimated the stellar effective temperatures by

converting the adopted spectral types (from Andrews & Williams 2007a, and references therein![]() ) with the dwarf temperature scale of Schmidt-Kaler (1982) for spectral types earlier than M0 and the intermediate temperature scale of Luhman (1999) for spectral types equal to or later than M0.

) with the dwarf temperature scale of Schmidt-Kaler (1982) for spectral types earlier than M0 and the intermediate temperature scale of Luhman (1999) for spectral types equal to or later than M0.

Stellar luminosities were computed from the 2MASS J-band flux (Cutri et al. 2003) after

calculating the extinction of each object by dereddening the J-H and

![]() colors to the locus observed for Classical T Tauri stars (Meyer et al. 1997), and adopting the Cardelli et al. (1989) extinction law with

RV = 4.2, which is appropriate for

colors to the locus observed for Classical T Tauri stars (Meyer et al. 1997), and adopting the Cardelli et al. (1989) extinction law with

RV = 4.2, which is appropriate for ![]() -Oph

-Oph![]() .

.

Luminosities and effective temperatures were converted into stellar masses and ages by using the Palla & Stahler (1999) models of PMS stars, as done in R10 (see Fig. 2). According to these models the ranges spanned by our sample go from about 0.2 ![]() (WSB 60) to 1.9

(WSB 60) to 1.9 ![]() (SR 21) in mass and from about 0.7 Myr (GSS 26, EL 24, YLW 16c) to 6.6 Myr (SR 21) in age.

(SR 21) in mass and from about 0.7 Myr (GSS 26, EL 24, YLW 16c) to 6.6 Myr (SR 21) in age.

The stellar parameters are reported in Table 2.

![\begin{figure}

\par\begin{tabular}{cc}

\includegraphics[scale=0.45]{00017fg1a.eps} &

\includegraphics[scale=0.45]{00017fg1b.eps}\\

\end{tabular}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/13/aa15039-10/Timg42.png)

|

Figure 1: Histograms higlighting some properties of our selected sample. In both the histograms our sample is represented by black columns, while the total columns (black+white) include all the class II YSOs from the Andrews & Williams (2007a) catalogue with no evidence of stellar companions in the 0.05-4.0'' interval in angular separation, from which our sample has been selected (see Sect. 3.1). Left) distribution of the fluxes at 1.3 mm, including upper limits; Right) distribution of stellar spectral type (see Sect. 3.3). |

| Open with DEXTER | |

|

Figure 2:

H-R diagram for the sources of our sample. The dashed and solid lines

represent the isochrones and evolutionary tracks respectively from the

Palla & Stahler (1999)

PMS evolutionary models. In this diagram the evolutionary tracks start

from an age of 0.1 Myr. The uncertainties, not shown in the plot,

are typically |

| Open with DEXTER | |

4 Analysis

In order to constrain the dust properties in the disk outer regions we fitted the sub-mm/mm SED with two-layer (i.e. disk surface and midplane) models of flared disks heated by the radiation of the central star (Chiang & Goldreich 1997; Dullemond et al. 2001). In Sects. 4.1 and 4.2 we describe the parameters which are needed to define a two-layer disk model. In Sect. 4.3 we then discuss which are the physical quantities of these models that can be constrained by our analysis.

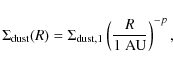

4.1 Disk structure

In order to characterize a model of the disk estimates for some stellar physical quantities (bolometric luminosity ![]() ,

effective temperature

,

effective temperature

![]() and mass

and mass ![]() ),

plus some information on the disk structure and on the the dust opacity

are needed. As for the stellar parameters we used the values listed in

Table 2.

Regarding the disk structure the only relevant parameters for our analysis are the disk outer radius

),

plus some information on the disk structure and on the the dust opacity

are needed. As for the stellar parameters we used the values listed in

Table 2.

Regarding the disk structure the only relevant parameters for our analysis are the disk outer radius

![]() and the parameters

and the parameters

![]() and p which define a power-law surface density for the dust component:

and p which define a power-law surface density for the dust component:

|

(1) |

radially truncated at

An important thing to keep in mind here is that with these values for

the outer radius of the disk the dust emission at the long wavelengths

considered in this paper turns out to be dominated by the optically

thin outer disk regions. This has two important consequences for our

discussion. The first one is that constraints on dust properties such

as dust grain sizes and dust mass can be derived from the continuum

emission at sub-mm/mm wavelengths. If a disk is much more compact than

the ones which have been commonly mapped so far, i.e. if

![]() AU,

then its emission would be dominated by the denser inner regions which

are optically thick even at these long wavelengths, and no information

on the dust properties could be inferred by the observed continuum. The

second consequence is that the disk inclination is not a relevant

parameter for our analysis, except only for the case of a nearly

edge-on disk that however would make the central PMS star invisible in

the optical.

AU,

then its emission would be dominated by the denser inner regions which

are optically thick even at these long wavelengths, and no information

on the dust properties could be inferred by the observed continuum. The

second consequence is that the disk inclination is not a relevant

parameter for our analysis, except only for the case of a nearly

edge-on disk that however would make the central PMS star invisible in

the optical.

Table 3: Disk properties.

4.2 Dust opacity

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[scale=0.75]{00017fg3.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/13/aa15039-10/Timg95.png)

|

Figure 3:

Sub-mm/mm SED fits for the 17 sources in our sample with the two-layer

flared disk models (solid lines). The errorbars in the plots take into

account an uncertainty of 10% on the absolute flux scale at wavelengths

shorter than 3 mm, and of 25% at 3 mm. The fitting

values of the spectral index |

| Open with DEXTER | |

To calculate the dust opacity we adopted the same dust grain model

taken in R10, i.e. porous composite spherical grains made of

astronomical silicates (optical constants from Weingartner &

Draine 2001), carbonaceous materials (Zubko et al. 1996) and water ices (Warren 1984) with fractional abundances from a simplification of the model used in Pollack et al. (1994) and a volume fraction for vacuum of ![]()

![]() .

In the disk surface and midplane we consider a dust grain population with a grain size number density

throughout all the disk

.

In the disk surface and midplane we consider a dust grain population with a grain size number density

throughout all the disk

|

(2) |

between

4.3 Method

After having set the disk outer radius

![]() and the power-law index p

of the surface density profile, the two-layer models can be used to fit

the sub-mm/mm SED of circumstellar disks to constrain dust properties

in the disk midplane

and the power-law index p

of the surface density profile, the two-layer models can be used to fit

the sub-mm/mm SED of circumstellar disks to constrain dust properties

in the disk midplane![]() , in particular the spectral index of the dust opacity

, in particular the spectral index of the dust opacity ![]() between two mm-wavelengths (1 and 3 mm in the case of this paper) and the product

between two mm-wavelengths (1 and 3 mm in the case of this paper) and the product

![]() between the mass in dust and the dust opacity at 1 mm. Except for very low values of

between the mass in dust and the dust opacity at 1 mm. Except for very low values of ![]() ,

which cannot be explained by large values of the power-law index q of the grain size number-density (see discussion in Sect. 5.1), every

,

which cannot be explained by large values of the power-law index q of the grain size number-density (see discussion in Sect. 5.1), every ![]() -value can be reproduced by different (q,

-value can be reproduced by different (q,

![]() )

couples. Furthermore, at a fixed q, the precise value of the maximum grain size

)

couples. Furthermore, at a fixed q, the precise value of the maximum grain size

![]() correspondent to a certain derived

correspondent to a certain derived ![]() depends strongly on the model that one adopts for the dust. The only

robust conclusion which is valid for all the reasonable models of dust

analyzed so far is that

depends strongly on the model that one adopts for the dust. The only

robust conclusion which is valid for all the reasonable models of dust

analyzed so far is that ![]() -values lower than the value found for the ISM (

-values lower than the value found for the ISM (

![]() )

can be obtained only with dust populations in which grains as large as at least

)

can be obtained only with dust populations in which grains as large as at least ![]() 1 mm are present (see e.g. Natta et al. 2007). For these reasons in the rest of the paper we will rarely refer to the maximum grain size

1 mm are present (see e.g. Natta et al. 2007). For these reasons in the rest of the paper we will rarely refer to the maximum grain size

![]() ,

whereas we will more frequently use

,

whereas we will more frequently use ![]() as our proxy for grain growth.

as our proxy for grain growth.

In order to derive an estimate for

![]() and thus constrain the dust mass

and thus constrain the dust mass

![]() ,

one has to adopt a certain model for the dust grain which provide a family of functions

,

one has to adopt a certain model for the dust grain which provide a family of functions

![]() labeled with the q-parameter. The

labeled with the q-parameter. The

![]() functions considered in this paper have been obtained using the dust model presented in Sect. 4.2 and they are the same shown in Fig. 3 in R10.

functions considered in this paper have been obtained using the dust model presented in Sect. 4.2 and they are the same shown in Fig. 3 in R10.

Figure 3 reports the best fit flared disk model overplotted to the sub-mm/mm data for each disk in our sample![]() .

Since as explained in Sect. 4.1 for each disk we have adopted,

instead of a single value, an interval of possible values for

.

Since as explained in Sect. 4.1 for each disk we have adopted,

instead of a single value, an interval of possible values for

![]() and p,

the uncertainty on these parameters translates into an uncertainty on

the quantities derived by fitting the sub-mm/mm SED, i.e.

and p,

the uncertainty on these parameters translates into an uncertainty on

the quantities derived by fitting the sub-mm/mm SED, i.e. ![]() and

and

![]() .

Adding this contribution to the uncertainties in the observational

data, the total absolute uncertainties are approximately 0.4 for

.

Adding this contribution to the uncertainties in the observational

data, the total absolute uncertainties are approximately 0.4 for ![]() and a factor of

and a factor of ![]() 3-4 for

3-4 for

![]() .

.

5 Results

The results of the SED-fitting procedure are listed in Table 3. Here we discuss them in terms of dust grain growth (Sect. 5.1) and mass in dust (Sect. 5.2) for our sample of protoplanetary disks.

5.1 Grain growth

Information on the level of dust grain growth in the outer regions

of protoplanetary disks comes from the analysis of the spectral index

of the dust opacity at (sub-)millimeter wavelengths ![]() ,

which reflects the spectral index of the disk SED at these long wavelengths

,

which reflects the spectral index of the disk SED at these long wavelengths ![]() .

In particular for a completely optically thin disk in the Rayleigh-Jeans regime

.

In particular for a completely optically thin disk in the Rayleigh-Jeans regime

![]() ,

whereas if emission from the optically thick disk inner regions (i.e.

,

whereas if emission from the optically thick disk inner regions (i.e.

![]() AU)

and deviations of the emitted spectrum from the Rayleigh-Jeans regime

are taken into account, as done for our analysis,

AU)

and deviations of the emitted spectrum from the Rayleigh-Jeans regime

are taken into account, as done for our analysis,

![]() .

In the limit case of a completely optically thick disk even at these long wavelengths the SED spectral index

.

In the limit case of a completely optically thick disk even at these long wavelengths the SED spectral index ![]() becomes independent on

becomes independent on ![]() and so no information on grain growth would be obtainable. In Cols. (5) and (6) of Table 3 the constrained values of

and so no information on grain growth would be obtainable. In Cols. (5) and (6) of Table 3 the constrained values of ![]() and

and ![]() between 1 and 3 mm are reported

between 1 and 3 mm are reported![]() .

.

Figure 4 shows the SED spectral index

![]() plotted against the observed flux at 3.3 mm for all the sources in our sample. The spanned range in

plotted against the observed flux at 3.3 mm for all the sources in our sample. The spanned range in

![]() is 1.8-2.9, and there is no clear evidence of any correlation between

the two plotted quantities. The fact that all the disks in our sample

show a (sub-)mm spectral index which is shallower than the one found

for the ISM, i.e.

is 1.8-2.9, and there is no clear evidence of any correlation between

the two plotted quantities. The fact that all the disks in our sample

show a (sub-)mm spectral index which is shallower than the one found

for the ISM, i.e.

![]() ,

brings evidence of grain growth from an initial ISM-like dust population for all the disks in our sample

,

brings evidence of grain growth from an initial ISM-like dust population for all the disks in our sample![]() .

.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[scale=0.5]{00017fg4.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/13/aa15039-10/Timg109.png)

|

Figure 4:

Spectral index |

| Open with DEXTER | |

In Fig. 5 we report the histogram of the derived distribution of ![]() -values. All the disks show

-values. All the disks show

![]() ,

indicative of dust grain growth to at least mm-sizes. Note that for 9 out of the 17 disks

,

indicative of dust grain growth to at least mm-sizes. Note that for 9 out of the 17 disks

![]() (considering a

(considering a ![]() -uncertainty on

-uncertainty on ![]() of about 0.4) and for them the data are not consistent with the MRN-value of 3.5 for the power-law index q of the dust grain size distribution in the ISM (Mathis et al. 1977): for these disks q-values as low as 2.5-3 are needed (see discussion in R10).

of about 0.4) and for them the data are not consistent with the MRN-value of 3.5 for the power-law index q of the dust grain size distribution in the ISM (Mathis et al. 1977): for these disks q-values as low as 2.5-3 are needed (see discussion in R10).

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[scale=0.45]{00017fg5.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/13/aa15039-10/Timg113.png)

|

Figure 5:

Distribution of the dust opacity spectral index |

| Open with DEXTER | |

The mean value is

![]() ,

which is consistent within 1

,

which is consistent within 1![]() with the one obtained for the Taurus sample discussed in R10 (

with the one obtained for the Taurus sample discussed in R10 (

![]() ).

In order to make a statistical comparison of the dust grain growth

between the Taurus sample and the one presented in this paper in the

).

In order to make a statistical comparison of the dust grain growth

between the Taurus sample and the one presented in this paper in the ![]() -Oph star forming region we performed a two-sample KS test. The probability that the two samples have

-Oph star forming region we performed a two-sample KS test. The probability that the two samples have ![]() -values drawn from the same distribution is

-values drawn from the same distribution is ![]()

![]() .

The hypothesis that the samples in Taurus and Ophiuchus have the same

.

The hypothesis that the samples in Taurus and Ophiuchus have the same ![]() -distribution cannot thus be rejected at the

-distribution cannot thus be rejected at the ![]() of confidence level.

of confidence level.

In Fig. 6 we plot the (sub-)mm spectral index of the dust opacity ![]() against the stellar age for YSOs in different evolutionary stages: the

38 class II disks in Ophiuchus and Taurus presented here and in

R10 respectively, and a sample of 15 less evolved class 0 YSOs

against the stellar age for YSOs in different evolutionary stages: the

38 class II disks in Ophiuchus and Taurus presented here and in

R10 respectively, and a sample of 15 less evolved class 0 YSOs![]() in Taurus, Perseus, and isolated from the PROSAC survey (Joergensen et al. 2007) and from Kwon et al. (2009). Contrary to the class II disks, for all the class 0 objects the values of

in Taurus, Perseus, and isolated from the PROSAC survey (Joergensen et al. 2007) and from Kwon et al. (2009). Contrary to the class II disks, for all the class 0 objects the values of ![]() have been obtained using the approximated

have been obtained using the approximated

![]() relation (see caption of Fig. 6). As described before, this relation gives only a lower-limit for

relation (see caption of Fig. 6). As described before, this relation gives only a lower-limit for ![]() ,

and this probably explains why for many of these sources the derived

,

and this probably explains why for many of these sources the derived ![]() is negative. A more sophisticated analysis is needed to get more robust estimates of

is negative. A more sophisticated analysis is needed to get more robust estimates of ![]() by taking into account self-consistently deviations from the above

relation as due to departures from the Rayleigh-Jeans regime of the

emission (expecially for these cold sources) and to marginally

optically thick emission typically associated to the compact structure

forming the disk. However, the low values of

by taking into account self-consistently deviations from the above

relation as due to departures from the Rayleigh-Jeans regime of the

emission (expecially for these cold sources) and to marginally

optically thick emission typically associated to the compact structure

forming the disk. However, the low values of ![]() obtained for nearly all these sources appear to show evidence for dust grain growth to

obtained for nearly all these sources appear to show evidence for dust grain growth to ![]() mm-sizes (see Fig. 3 in R10) already in the earliest stages of star formation. Ormel et al. (2009)

have recently investigated the effects of dust coagulation and

fragmentation onto the dust size distribution in molecular cloud cores.

They found that grain sizes close to

mm-sizes (see Fig. 3 in R10) already in the earliest stages of star formation. Ormel et al. (2009)

have recently investigated the effects of dust coagulation and

fragmentation onto the dust size distribution in molecular cloud cores.

They found that grain sizes close to ![]() 1 mm

can be formed if cloud lifetimes are not restricted to free-fall times

but rather support mechanisms like e.g. ambipolar diffusion are present

and if freeze-out of ice has commenced. According to their simulations

ice-coated grains can grow to sizes of

1 mm

can be formed if cloud lifetimes are not restricted to free-fall times

but rather support mechanisms like e.g. ambipolar diffusion are present

and if freeze-out of ice has commenced. According to their simulations

ice-coated grains can grow to sizes of ![]() 0.3-8 mm in one ambipolar diffusion timescale at densities of

n = 105-107 cm-3, which are typical of the inner regions of molecular cores. Dust grain growth to

0.3-8 mm in one ambipolar diffusion timescale at densities of

n = 105-107 cm-3, which are typical of the inner regions of molecular cores. Dust grain growth to ![]() mm-sizes can thus be a process accompanying the very first phases of star formation.

mm-sizes can thus be a process accompanying the very first phases of star formation.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[scale=0.5]{00017fg6.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/13/aa15039-10/Timg118.png)

|

Figure 6:

Dust opacity spectral index |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Figure 6 shows also that

there is no relation between the dust opacity spectral index and the

stellar age for the class II disks: grains as large as ![]() 1 mm

appears to be present in the outer regions of disks throughout all the

class II evolutionary stage. This is in contrast with the short

timescales of inward radial drift expected for

1 mm

appears to be present in the outer regions of disks throughout all the

class II evolutionary stage. This is in contrast with the short

timescales of inward radial drift expected for ![]() mm/cm-sized

grains in the outer disk as a consequence of the dust interaction with

the gas component. In order to explain the retention of large dust

grains in these outer regions some mechanisms which may halt the drift

of solid particles, e.g. local pressure maxima due to turbulent

vortices or spiral density waves, have been invoked. Birnstiel

et al. (2010b) have

compared the observed fluxes at millimeter wavelengths for the disks

samples described in R10 and in this paper with predictions of dust

evolution models accounting for coagulation and fragmentation. They

showed that, if radial drift of solid particles is completely

suppressed, a grain size distribution at the steady-state (due to a

balance between coagulation and fragmentation) can explain the mm-wave

emission of the brightest disks. The observed flux of the fainter disks

are instead typically overpredicted even by more than one order of

magnitude. These discrepancies may be explained by considering in the

disk models a dust reduction due to radial drift at a reduced rate

mm/cm-sized

grains in the outer disk as a consequence of the dust interaction with

the gas component. In order to explain the retention of large dust

grains in these outer regions some mechanisms which may halt the drift

of solid particles, e.g. local pressure maxima due to turbulent

vortices or spiral density waves, have been invoked. Birnstiel

et al. (2010b) have

compared the observed fluxes at millimeter wavelengths for the disks

samples described in R10 and in this paper with predictions of dust

evolution models accounting for coagulation and fragmentation. They

showed that, if radial drift of solid particles is completely

suppressed, a grain size distribution at the steady-state (due to a

balance between coagulation and fragmentation) can explain the mm-wave

emission of the brightest disks. The observed flux of the fainter disks

are instead typically overpredicted even by more than one order of

magnitude. These discrepancies may be explained by considering in the

disk models a dust reduction due to radial drift at a reduced rate![]() or during an earlier evolutionary time or due to efficient conversion

of dust into larger, unseen bodies (see Birnstiel et al. 2010b for more details). Observations of these faint disks can thus help us to determine

which mechanisms play a major role for the dynamics and evolution of large grains in the outer regions of disks.

or during an earlier evolutionary time or due to efficient conversion

of dust into larger, unseen bodies (see Birnstiel et al. 2010b for more details). Observations of these faint disks can thus help us to determine

which mechanisms play a major role for the dynamics and evolution of large grains in the outer regions of disks.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[scale=0.45]{00017fg7.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/13/aa15039-10/Timg119.png)

|

Figure 7:

SED spectral index between 1 and 3 mm versus indicators of grain growth from the 10- |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Figure 7 shows the spectral

index between 1 and 3 mm in Taurus (left) and Ophiuchus (right)

plotted against two indicators of dust processing from the silicate

feature observed at about 10 ![]() m (see e.g. Kessler-Silacci et al. 2006). Data for the 10

m (see e.g. Kessler-Silacci et al. 2006). Data for the 10 ![]() m

silicate feature for the two samples in Taurus and Ophiuchus come from

the literature and refer to different indicators (see caption of

Fig. 7) since we could not find the same indicator for both the regions. However Lommen et al. (2010)

showed that these two indicators correlate well and so they can be both

used to probe the growth of grains from interstellar, submicron sizes

to sizes of several microns in the disk surface layers. In particular

low values of the ratio between the 10

m

silicate feature for the two samples in Taurus and Ophiuchus come from

the literature and refer to different indicators (see caption of

Fig. 7) since we could not find the same indicator for both the regions. However Lommen et al. (2010)

showed that these two indicators correlate well and so they can be both

used to probe the growth of grains from interstellar, submicron sizes

to sizes of several microns in the disk surface layers. In particular

low values of the ratio between the 10 ![]() m line flux and the continuum,

m line flux and the continuum,

![]() ,

and large values of the ratio between the fluxes at 11.3 and 9.8

,

and large values of the ratio between the fluxes at 11.3 and 9.8 ![]() m,

F11.3/F9.8, are interpreted in terms of grain growth to micron sizes (Bouwman et al. 2001; Kessler-Silacci et al. 2006). Very recently Lommen et al. (2010)

have found a tentative correlation between these quantities for a

sample of about 30 TTS and Herbig-Ae/Be systems spread over five

different star forming regions, including Taurus-Auriga. Since the mm

slope of the SED probes grains in the disk outer regions whereas the 10-

m,

F11.3/F9.8, are interpreted in terms of grain growth to micron sizes (Bouwman et al. 2001; Kessler-Silacci et al. 2006). Very recently Lommen et al. (2010)

have found a tentative correlation between these quantities for a

sample of about 30 TTS and Herbig-Ae/Be systems spread over five

different star forming regions, including Taurus-Auriga. Since the mm

slope of the SED probes grains in the disk outer regions whereas the 10-![]() m

silicate feature is sensitive to grains in the inner regions, the

tentative correlation may indicate a parallel evolution of the inner

and outer disk in terms of dust grain growth. However, in this work we

do not find any correlation neither for the sample in Taurus nor for

the one in Ophiuchus. Note that in the case of Ophiuchus the sample

with literature data for the 10-

m

silicate feature is sensitive to grains in the inner regions, the

tentative correlation may indicate a parallel evolution of the inner

and outer disk in terms of dust grain growth. However, in this work we

do not find any correlation neither for the sample in Taurus nor for

the one in Ophiuchus. Note that in the case of Ophiuchus the sample

with literature data for the 10-![]() m

silicate feature is limited to eight disks only. In Taurus our sample

comprises nine of the eleven disks considered by Lommen et al.,

and for two of them (AA Tau and GM Aur) our derived values of

m

silicate feature is limited to eight disks only. In Taurus our sample

comprises nine of the eleven disks considered by Lommen et al.,

and for two of them (AA Tau and GM Aur) our derived values of

![]() are not consistent with and lower than the values used by Lommen et al.

are not consistent with and lower than the values used by Lommen et al.![]() .

Note also that the absence of such a correlation would not be too

surprising since the physical mechanisms which are responsible for the

observed values of the grain growth indicators are different: the

presence of mm/cm-sized pebbles in the midplane of the outer disk is

mainly due to coagulation processes and mechanisms which trap these

pebbles in the outer disk, whereas the presence of

.

Note also that the absence of such a correlation would not be too

surprising since the physical mechanisms which are responsible for the

observed values of the grain growth indicators are different: the

presence of mm/cm-sized pebbles in the midplane of the outer disk is

mainly due to coagulation processes and mechanisms which trap these

pebbles in the outer disk, whereas the presence of ![]() m-sized

grains in the surface layers of the inner disk is probably regulated by

fragmentation of larger solid particles and a balance between settling

and turbulence mixing which keeps these relatively small grains in the

uppermost layers of the disk. Further observations with more sensitive

telescopes in the future are needed to provide necessary the necessary

statistics to better investigate the possible relation between dust

grains in the outer and inner disk regions and to possibly constrain

the processes of radial mixing and vertical settling.

m-sized

grains in the surface layers of the inner disk is probably regulated by

fragmentation of larger solid particles and a balance between settling

and turbulence mixing which keeps these relatively small grains in the

uppermost layers of the disk. Further observations with more sensitive

telescopes in the future are needed to provide necessary the necessary

statistics to better investigate the possible relation between dust

grains in the outer and inner disk regions and to possibly constrain

the processes of radial mixing and vertical settling.

5.2 Disk mass

Table 3 lists the derived

dust masses for our sample of disks detected at 3 mm. As already

discussed in R10, the inferred dust mass depends, at a given chemical

composition and porosity for the dust grain, on the assumed value of

the power-law index q of the grain size distribution. This

dependence, which is due to the different millimeter dust opacities

obtained for different values of q (see R10), is particularly strong for relatively low values of ![]() .

For example, in the case of WSB 60, with

.

For example, in the case of WSB 60, with

![]() ,

,

![]() is larger than

is larger than

![]() by a factor of about 10.

by a factor of about 10.

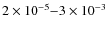

Even if the estimate for

![]() depends on the value of q, the range spanned by our sample for q=2.5 and q=3 turns out to be very similar

depends on the value of q, the range spanned by our sample for q=2.5 and q=3 turns out to be very similar![]() ,

namely

,

namely ![]()

![]() ,

corresponding to roughly 6-1000

,

corresponding to roughly 6-1000

![]() .

By defining a planetesimal as a rocky body with a radius of 10 km

and a density similar to the one adopted for our dust grain model (i.e.

.

By defining a planetesimal as a rocky body with a radius of 10 km

and a density similar to the one adopted for our dust grain model (i.e.

![]() g/cm3),

the maximum number of planetesimals which can be potentially formed out

of this reservoir of small grains (see discussion below) is

g/cm3),

the maximum number of planetesimals which can be potentially formed out

of this reservoir of small grains (see discussion below) is ![]() 1010-1012.

1010-1012.

These numbers have to be taken with great caution mainly because of the large uncertainty for the inferred dust mass of a factor as large as 10 (see e.g. the discussion in Natta et al. 2004).

Here it is important to remember that observations at (sub-)mm

wavelengths are completely insensitive to pebbles/stones much larger

than ![]() 1-10 cm, since the dust opacity decreases as the

1-10 cm, since the dust opacity decreases as the

![]() of the dust population increases at sizes larger than the wavelengths

of the observations. For this reason the dust masses presented here

have to be interpreted as lower limits for the real total mass in

solids, since in principle large pebbles/stones or even larger rocky

bodies like planetesimals may be already present in the disk.

of the dust population increases at sizes larger than the wavelengths

of the observations. For this reason the dust masses presented here

have to be interpreted as lower limits for the real total mass in

solids, since in principle large pebbles/stones or even larger rocky

bodies like planetesimals may be already present in the disk.

Finally we have investigated relations between dust properties in disks (i.e. ![]() ,

,

![]() )

and the stellar ones (listed in Table 2)

but we did not find any significant correlation, similarly to the case

of Taurus (R10). No significant correlation was found neither between

grain growth and dust mass.

)

and the stellar ones (listed in Table 2)

but we did not find any significant correlation, similarly to the case

of Taurus (R10). No significant correlation was found neither between

grain growth and dust mass.

6 Summary

We have presented new observations at ![]() 3 mm obtained with the ATCA array and the new CABB digital filter bank for 27 protoplanetary disks in the

3 mm obtained with the ATCA array and the new CABB digital filter bank for 27 protoplanetary disks in the ![]() -Oph

star forming region. Among these we selected the 17 isolated

class II YSOs with well characterized stellar properties (see

selection criteria in Sect. 3.1). Our sample comprises all the

-Oph

star forming region. Among these we selected the 17 isolated

class II YSOs with well characterized stellar properties (see

selection criteria in Sect. 3.1). Our sample comprises all the ![]() -Oph isolated class II YSOs with an observed flux at 1.3 mm larger than

-Oph isolated class II YSOs with an observed flux at 1.3 mm larger than ![]() 75 mJy, and

75 mJy, and ![]()

![]() of the isolated PMS stars with mass larger than

of the isolated PMS stars with mass larger than ![]() 0.5

0.5 ![]() .

We have analyzed the (sub-)millimeter SED of our disk sample and here is the summary of our main findings:

.

We have analyzed the (sub-)millimeter SED of our disk sample and here is the summary of our main findings:

- 1.

- The spectral index

of the millimeter dust opacity turns out to be lower than the typical

value found for the ISM for all the 17 disks detected at 3 mm. The

mean value is

of the millimeter dust opacity turns out to be lower than the typical

value found for the ISM for all the 17 disks detected at 3 mm. The

mean value is

.

For the ten disks which have been observed and spatially resolved

through past high-angular resolution continuum imaging at sub-mm

wavelengths this represents evidence for the presence of dust grains as

large as at least

.

For the ten disks which have been observed and spatially resolved

through past high-angular resolution continuum imaging at sub-mm

wavelengths this represents evidence for the presence of dust grains as

large as at least  1 mm

in the disk outer regions. For the seven disks which have not been

mapped yet the observations could in principle be consistent also with

very compact (

1 mm

in the disk outer regions. For the seven disks which have not been

mapped yet the observations could in principle be consistent also with

very compact (

AU) disks, significantly different from those mapped so far.

AU) disks, significantly different from those mapped so far.

- 2.

- From a comparison between the results found for our sample in

-Oph

and an homogeneously selected sample of 21 isolated class II disks

in Taurus-Auriga (R10), there is no statistical evidence of any

difference between the distribution of

-Oph

and an homogeneously selected sample of 21 isolated class II disks

in Taurus-Auriga (R10), there is no statistical evidence of any

difference between the distribution of  -values

found in the two star forming regions. This may suggest that

environmental effects do not play an important role in the first phases

of planet formation.

-values

found in the two star forming regions. This may suggest that

environmental effects do not play an important role in the first phases

of planet formation. - 3.

- There is no evidence for any evolution of the dust spectral

index: dust grains appear to be present in the outer regions of

protoplanetary disks throughout all the class II evolutionary

stage of YSOs, confirming what previously found in Taurus. In order to

explain the retention of large dust grains in the outer disk some

mechanisms which may halt the inward drift of solid particles, e.g.

local pressure maxima due to turbulent vortices or spiral density

waves, have to be invoked. Since evidence for grain growth to

millimeter sizes appears to be present in some class 0 YSOs the

formation of the

mm-sized

grains seen in class II disks may already occur in the densest

inner regions of molecular cloud cores (Ormel et al. 2009).

mm-sized

grains seen in class II disks may already occur in the densest

inner regions of molecular cloud cores (Ormel et al. 2009).

- 4.

- The mm slope of the SED does not correlate with indicators of

dust processing from the silicate feature observed at about 10

m,

which are sensitive to grain growth to micron sizes in the surface

layers of the inner disk; further observations at (sub-)mm wavelengths

are needed to extend the investigation to a larger sample.

m,

which are sensitive to grain growth to micron sizes in the surface

layers of the inner disk; further observations at (sub-)mm wavelengths

are needed to extend the investigation to a larger sample. - 5.

- The spanned range in dust mass contained in grains with sizes

1 cm as derived with the dust model described in Sect. 4.2 is about

1 cm as derived with the dust model described in Sect. 4.2 is about

or roughly 6-1000

or roughly 6-1000

.

This reservoir of small grains is capable of forming about

1010-1012 10 km-sized planetesimals with a mean density of

.

This reservoir of small grains is capable of forming about

1010-1012 10 km-sized planetesimals with a mean density of  1 g/cm3.

1 g/cm3.

We are grateful to an anonymous referee for suggestions that helped to improve the clarity of the paper. We wish to thank the support astronomers in Narrabri, in particular James Urquhart and Maxim Voronkov, for their help during the ATCA observations. L.R. aknowledges the PhD fellowship of the International Max-Planck-Research School. L.T. and A.N. were partly supported by the grant ASI-COFIS I/016/07/0.

References

- Andrews, S. M., & Williams, J. P. 2007a, ApJ, 671, 1800 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, S. M., & Williams, J. P. 2007b, ApJ, 659, 705 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, S. M., Wilner, D. J., Hughes, A. M., Qi, C., & Dullemond, C. P. 2009, ApJ, 700, 1502 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Beckwith, S. V. W., & Sargent, A. I. 1991, ApJ, 381, 250 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Beckwith, S. V. W., Henning, Th., & Nakagawa, Y. 2000, in Protostar & Planets IV, ed. V. Mannings, A. P. Boss, & S. S. Russell (Tucson: Univ. of Arizona Press), 533 [Google Scholar]

- Birnstiel, T., Dullemond, C. P., & Brauer, F. 2009, A&A, 503, 5 [Google Scholar]

- Birnstiel, T., Dullemond, C. P., & Brauer, F. 2010a, A&A, 513, 79 [Google Scholar]

- Birnstiel, T., Ricci, L., Trotta, F., et al. 2010b, A&A, 516, L14 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Bouwman, J., Meeus, G., de Koter, A., et al. 2001, A&A, 375, 950 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, J. M., Blake, G. A., Qi, C., et al. 2009, ApJ, 704, 496 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cardelli, J. A., Clayton, G. C., & Mathis, J. S. 1989, ApJ, 345, 245 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang, E. I., & Goldreich, P. 1997, ApJ, 490, 368 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cutri, R. M., et al. 2003, 2MASS All Sky Catalog of point sources [Google Scholar]

- Dent, W. R. F., Matthews, H. E., & Ward-Thompson, D. 1998, MNRAS, 301, 1049 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Draine, B. T. 2006, ApJ, 636, 1114 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Dominik, C., Blum, J., Cuzzi, J. N., & Wurm, G. 2007, in Protostars & Planets V, ed. B. Reipurth, D. Jewitt, & K. Keil (Tucson: University of Arizona Press), 783 [Google Scholar]

- Dullemond, C. P., Dominik, C., & Natta, A. 2001, ApJ, 560, 957 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Furlan, E., Hartmann, L., Calvet, N., et al. 2006, ApJS, 165, 568 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [MathSciNet] [Google Scholar]

- Gullbring, E., Hartmann, L., Briceño, C., & Calvet, N. 1998, ApJ, 492, 323 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Joergensen, J. K., Bourke, T. L., Myers, P. C., et al. 2007, ApJ, 659, 479 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler-Silacci, J., Augereau, J. C., Dullemond, C. P., et al. 2006, ApJ, 639, 275 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, W., Looney, L. W., Mundy, L. G., Chiang, H.-F., & Kemball, A. J. 2009, ApJ, 696, 841 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lombardi, M., Lada, C. J., & Alves, J. 2008, A&A, 480, 785 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Lommen, D., Wright, C. M., Maddison, S. T., et al. 2007, A&A, 462, 211 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Lommen, D., van Dishoeck, E. F., Wright, C. M., et al. 2010, A&A, 515, 77 [Google Scholar]

- Luhman, K. L. 1999, ApJ, 525, 466 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lynden-Bell, D., & Pringle, J. E. 1974, MNRAS, 168, 603 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mathis, J. S., Rumpl, W., & Nordsieck, K. H. 1977, ApJ, 217, 425 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe, C., Ghez, A. M., Prato, L., et al. 2006, ApJ, 636, 932 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- McClure, M. K., Furlan, E., Manoj, P., et al. 2010, ApJS, 188, 75 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, M. R., Calvet, N., & Hillenbrand, L. A. 1997, AJ, 114, 288 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Motte, F., Andre, P., & Neri, R. 1998, A&A, 336, 150 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Natta, A., Testi, L., Neri, R., Shepherd, D. S., & Wilner, D. J. 2004, A&A, 416, 179 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Natta, A., Testi, L., & Randich, S. 2006, A&A, 452, 245 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Natta, A., Testi, L., Calvet, N., et al. 2007, in Protostars & Planets V, ed. B. Reipurth, D. Jewitt, & K. Keil (Tucson: University of Arizona Press), 783 [Google Scholar]

- Ormel, C. W., Paszun, D., Dominik, C., & Tielens, A. G. G. M. 2009, A&A, 502, 845 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Palla, F., & Stahler, S. W. 1999, ApJ, 525, 772 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pollack, J. B., Hollenbach, D., Beckwith, S., et al. 1994, ApJ, 421, 615 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ratzka, T., Köhler, R., & Leinert, Ch. 2005, A&A, 437, 611 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Reipurth, B., & Zinnecker, H. 1993, A&A, 278, 81 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Ricci, L., Testi, L., Natta, A., et al. 2010, A&A, 512, 15 (R10) [Google Scholar]

- Rodmann, J., Henning, T., Chandler, C. J., Mundy, L. G., & Wilner, D. J. 2006, A&A, 446, 211 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt-Kaler, T. 1982, in Landolt-BornsteinGroup VI, ed. K.-H. Hellwege (Berlin: Springer), 2, 454 [Google Scholar]

- Simon, M., Ghez, A. M., Leinert, Ch., et al. 1995, ApJ, 443, 625 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Testi, L., Natta, A., Shepherd, D. S., & Wilner, D. J. 2003, A&A, 403, 323 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Van Boekel, R., Waters, L. B. F. M., Dominik, C., et al. 2003, A&A, 400, 21 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Warren, S. G. 1984, ApOpt, 23, 1206 [Google Scholar]

- Weingartner, J. C., & Draine, B. T. 2001, ApJ, 548, 296 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Wilking, B. A., Gagné, M., & Allen, L. E. 2008, in Handbook of Star Forming Regions: Volume II, The Southern Sky, ed. Reipurth (San Francisco, CA: ASP), 351 [Google Scholar]

- Wilner, D. J., Ho, P. T. P., Kastner, J. H., & Rodríguez, L. F. 2000, ApJ, 534, L101 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zubko, V. G., Mennella, V., Colangeli, L., & Bussoletti, E. 1996, MNRAS, 282, 1321 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Footnotes

- ... (ATCA

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- The Australia Telescope Compact Array is part of the Australia Telescope which is funded by the Commonwealth of Australia for operation as a National Facility managed by CSIRO.

- ... calibration

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- For the data reduction we used the MIRIAD package.

- ... analysis

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- Note that the final sample used in the analysis does not comprise all the targets of the new ATCA observations described in Sect. 2.

- ... range

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- Note that in R10 a slightly narrower spectral range of

mm

was chosen. We adopted a broader spectral range to include in our

sample the sources YLW 16c and WSB 52, for which no observations at

mm

was chosen. We adopted a broader spectral range to include in our

sample the sources YLW 16c and WSB 52, for which no observations at

mm

have been carried out so far. The different uncertainties for the

spectral slopes of these sources, due to a shorter spectral leverage,

are properly taken into account in the analysis.

mm

have been carried out so far. The different uncertainties for the

spectral slopes of these sources, due to a shorter spectral leverage,

are properly taken into account in the analysis.

- ... models

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- Note that this completeness level is very close to the one obtained in R10 in the Taurus-Auriga star forming region, i.e.

of the isolated class II YSOs with stellar masses larger than

of the isolated class II YSOs with stellar masses larger than

.

.

- ... therein

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- For only two cases in our sample, i.e. EL 20 and IRS 41, the spectral types are not available in Andrews & Williams (2007a). For these PMS stars we adopted the stellar types from Natta et al. (2006) which are based on near infrared broad band photometry.

- ...

-Oph

-Oph![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- For IRS 41, for which the 2MASS J-band flux is not available, we adopted the luminosities as derived by Natta et al. (2006), after correcting them by a multiplicative factor (130 pc/150 pc)2 to account for the different adopted distance of 150 pc in the Natta et al. paper.

- ...

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- We also consider the same value of q for both the surface and the midplane. However, contrary to the dust in the midplane where q is a relevant parameter, in the disk surface the adopted q-value is practically non influential since

is only slightly larger than

is only slightly larger than

.

.

- ... midplane

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- Note that this is true only in the case in which the dust emission at long wavelengths comes mostly from the optically thin disk outer regions, as described at the end of Sect. 4.1.

- ... sample

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- Note that for a few disks (SR 4, EL 20, RNO 90) the flux at

1 mm

falls below the model line. Although this could be due to problems in

the observations, another possible reason is that the 3 mm-flux

for these sources is contaminated by free-free emission. If this was

the case, the derived

1 mm

falls below the model line. Although this could be due to problems in

the observations, another possible reason is that the 3 mm-flux

for these sources is contaminated by free-free emission. If this was

the case, the derived  -values

for these disks would be only lower-limits. Observations at longer

wavelengths, where free-free dominates the emission, are needed to

constrain its possible contribution at 3 mm.

-values

for these disks would be only lower-limits. Observations at longer

wavelengths, where free-free dominates the emission, are needed to

constrain its possible contribution at 3 mm.

- ... reported

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- Note that the difference

turns

out to be in the range 1.6-1.9. This (small) discrepancy from the value

of 2 is primarly due to the low temperature of the outer disk

midplane and the consequent deviation from the Rayleigh-Jeans regime of

the mm-wave emission.

turns

out to be in the range 1.6-1.9. This (small) discrepancy from the value

of 2 is primarly due to the low temperature of the outer disk

midplane and the consequent deviation from the Rayleigh-Jeans regime of

the mm-wave emission.

- ... sample

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- This sentence is strictly valid for the ten disks in our

sample which have been mapped so far; for the seven disks which have

not been mapped yet this sentence is valid only if the underlying

assumption that their spatial extension is not so small that most of

the mm emission is optically thick (

AU) holds true.

AU) holds true.

- ... YSOs

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- Note that for these objects there are no robust age-estimates.

- ... rate

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- The radial drift, other than decreasing the amount of dust in the disk and thus decreasing the flux at millimeter wavelengths, is more efficient for mm/cm-sized pebbles than for smaller grains in the outer disk. For this reason, if one wants to explain the low values of the mm-spectral indeces only a reduced rate of radial drift (from that expected theoretically) can be invoked.

- ... et al.

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- This discrepancy is probably due to a different choice of the literature data used for the derivation of

.

In the case of R10 all the data obtained at sub-mm and mm wavelengths have been used.

.

In the case of R10 all the data obtained at sub-mm and mm wavelengths have been used.

- ... similar

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- Note however that for the four disks with the lowest value of

(

( 0)

0)

cannot be obtained. The reason for this is that these very low

cannot be obtained. The reason for this is that these very low  -values cannot be explained with q=3 (see discussion in Sect. 5.1). For the same reason only two disks have an estimate for the dust mass with q=3.5.

-values cannot be explained with q=3 (see discussion in Sect. 5.1). For the same reason only two disks have an estimate for the dust mass with q=3.5.

All Tables

Table 1: Summary of the 3.3 mm ATCA observations.

Table 2: Stellar properties of the considered sample.

Table 3: Disk properties.

All Figures

![\begin{figure}

\par\begin{tabular}{cc}

\includegraphics[scale=0.45]{00017fg1a.eps} &

\includegraphics[scale=0.45]{00017fg1b.eps}\\

\end{tabular}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/13/aa15039-10/Timg42.png)

|

Figure 1: Histograms higlighting some properties of our selected sample. In both the histograms our sample is represented by black columns, while the total columns (black+white) include all the class II YSOs from the Andrews & Williams (2007a) catalogue with no evidence of stellar companions in the 0.05-4.0'' interval in angular separation, from which our sample has been selected (see Sect. 3.1). Left) distribution of the fluxes at 1.3 mm, including upper limits; Right) distribution of stellar spectral type (see Sect. 3.3). |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

|

Figure 2:

H-R diagram for the sources of our sample. The dashed and solid lines

represent the isochrones and evolutionary tracks respectively from the

Palla & Stahler (1999)

PMS evolutionary models. In this diagram the evolutionary tracks start

from an age of 0.1 Myr. The uncertainties, not shown in the plot,

are typically |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[scale=0.75]{00017fg3.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/13/aa15039-10/Timg95.png)

|

Figure 3:

Sub-mm/mm SED fits for the 17 sources in our sample with the two-layer

flared disk models (solid lines). The errorbars in the plots take into

account an uncertainty of 10% on the absolute flux scale at wavelengths

shorter than 3 mm, and of 25% at 3 mm. The fitting

values of the spectral index |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[scale=0.5]{00017fg4.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/13/aa15039-10/Timg109.png)

|

Figure 4:

Spectral index |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[scale=0.45]{00017fg5.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/13/aa15039-10/Timg113.png)

|

Figure 5:

Distribution of the dust opacity spectral index |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[scale=0.5]{00017fg6.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/13/aa15039-10/Timg118.png)

|

Figure 6:

Dust opacity spectral index |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[scale=0.45]{00017fg7.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/13/aa15039-10/Timg119.png)

|

Figure 7:

SED spectral index between 1 and 3 mm versus indicators of grain growth from the 10- |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

Copyright ESO 2010

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.