| Issue |

A&A

Volume 559, November 2013

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A25 | |

| Number of page(s) | 7 | |

| Section | Stellar structure and evolution | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201321961 | |

| Published online | 30 October 2013 | |

Visibility of unstable oscillation modes in a rapidly rotating B star

Astronomical Institute “Anton Pannekoek”, University of

Amsterdam,

Science Park 904,

1098 XH

Amsterdam,

The Netherlands

e-mail:

G.J.Savonije@contact.uva.nl

Received:

25

May

2013

Accepted:

30

September

2013

Context. Space missions like CoRoT and Kepler have provided numerous new observations of stellar oscillations in a multitude of stars by high precision photometry. The identification of the photometrically observed oscillations is, however, difficult and requires detailed model calculations of pulsating stars.

Aims. This work compares the observed rich oscillation spectrum of the rapidly rotating B3 IV star HD 43317 with the first results obtained by a new method to calculate unstable oscillation modes in rapidly rotating stars in order to see whether some of the observed modes can be identified.

Methods. The new numerical method consists of two parts. We first search for modes resonant with a prescribed forcing symmetry by moving through relevant regions of complex frequency space and monitoring any increase of the stellar response to the applied forcing and zooming in onto the resonance. These resonant non-adiabatic 2D-solutions are then fed into a 2D relaxation code with the same equations but without forcing terms. The complex oscillation frequency used in the forcing is now no longer prescribed, but added as an extra unknown. The corresponding free oscillation mode is usually obtained after a few (<10) iterations with only minor adjustment of the complex oscillation frequency. To compare with the observed light variations we calculate the “visibility” of the found unstable oscillation modes, taking into account the cancellation of the various parts of the radiating oscillating stellar surface as seen by the observer.

Results. The frequencies of unstable axisymmetric g-modes, which have the highest visibility, appear to nearly coincide with the observed largest amplitude photometric variations of HD 43317, making an identification of the latter oscillations as m = 0 modes plausible. The identification of m = 1 g-modes is less straightforward, while many of the unstable even m = 2 g-modes may correspond to observed weaker photometric variations. Only one unstable r-mode has non-negligible visibility. The observationally inferred almost equidistant period spacings of ten, respectively seven, oscillation frequencies for HD 43317 cannot be reproduced.

Key words: stars: rotation / stars: oscillations

© ESO, 2013

1. Introduction

The Kepler (Borucki et al. 2009) and

CoRoT (Auvergne et al. 2009; Baglin et al. 2009) space missions have resulted in a wealth of detailed

new pulsation data for an extended sample of stars. Pápics

et al. (2012) presented a list of oscillation frequencies obtained by 5 months of

photometric monitoring of the B3 IV star HD 43317 by the CoRoT satellite combined with high

resolution and high S/N spectra obtained with the ground based HARPS instrument of ESO. They

conclude from the spectroscopic variability that for this star the rotation frequency

Ωs is about 50% of the critical break-up speed. Asteroseismic studies of

rapidly rotating stars are complicated by the fact that the Coriolis force makes the set of

oscillation equations unseparable into an r and θ part. A

possible approach (Unno et al. 1989) is to

approximate the full oscillation solution by a truncated series of spherical harmonics to

describe the r and θ dependence and solve a coupled set of differential

equations by a shooting method. One may assume a ϕ dependence of

eimϕ with given m, since the unperturbed

star is assumed spherically symmetric. However, many of the observed oscillation frequencies

with significant amplitudes in Pápics et al. (2012)

fall in the so-called “inertial-range” with  , for which the corresponding

oscillation modes cannot be adequately described by superposition of only a small number of

spherical harmonics, which makes this method rather cumbersome.

, for which the corresponding

oscillation modes cannot be adequately described by superposition of only a small number of

spherical harmonics, which makes this method rather cumbersome.

Several papers describing new developments with oscillation codes have appeared recently, see Ouazzani et al. (2012), Valsecchi et al. (2013) and Townsend & Teitler (2013). In this paper another approach is used whereby an iterative relaxation calculation (like the Henyey codes used for stellar evolution calculations) is performed on a fine (r, θ) grid using a 2D non-adiabatic code in which the Coriolis force (first order in Ωs) is fully taken into account but the centrifugal force (being second order in Ωs) is neglected. We use a two-step procedure where we first search in complex frequency space for strong stellar responses using a prescribed forcing as done earlier (Savonije 2005). After zooming in to these resonances we now use in the second step the thus obtained resonant response as input for the relaxation code (in which the forcing terms have been taken out) which iterates until the solution converges to the corresponding free oscillation mode. In this way it is relatively easy to find free oscillation modes with a relaxation code. A problem (even with 1D) relaxation codes has always been to find a suitable starting model from which the oscillation code is able to succesfully converge the iterative sequence, e.g. Unno et al. (1989). With the current code this is generally no longer a problem. The relaxation method where the oscillation equations are solved as difference equations on a 2D grid has the advantage that the higher order harmonics induced by the Coriolis force are included in the solution. Evidently it requires a grid with adequate resolution which implies use of considerable computer power.

Although the inferred stellar parameters (Pápics et al. 2012) imply a rapid rotation speed of Ωs/Ωc = 0.5 that would require inclusion of the centrifugal distortion (∝(Ωs/Ωc)2) of the star, a spherically symmetric star is used as input model for the pulsation calculations. Note in this respect that the non-spherical centrifugal distortion of the star induces baroclinic currents in the otherwise stably stratified radiative layers which can significantly perturb the angular momentum profile. This is a significant complication which makes it difficult to produce an unperturbed non-spherical equilibrium structure, but see the work by Espinosa Lara & Rieutord (2013) for recent developments.

In the current oscillation calculations the Coriolis force is fully taken into account as this force is required to simulate the direct first order effect of rotation on stellar pulsations. We study the oscillation modes and their linear stability in a B-star rotating with Ωs/Ωc = 0.5 in the frequency range where the strongest photometric amplitudes are observed in HD 43317 (up to 4.5 cycles per day in the observer’s frame).

1.1. Stellar input model

For a first test of this new code we consider a uniformly rotating main sequence star of 5.4 M⊙ with radius Rs = 3.8 R⊙, Teff = 1.70 × 104 K and Z = 0.014 as a model for the B3 IV star HD 43317, in line with data given in Pápics et al. (2012). The unperturbed (1D) stellar model used as input model for the oscillation calculations was obtained with the freely obtainable stellar evolution code MESA1 (Paxton et al. 2013) using standard OPAL opacities and no overshooting from the convective core. The 5.4 M⊙ model has a convective core that extends to r/Rs = 0.118 and a shallow convective surface shell between r/Rs = 0.994−0.996.

2. Basic oscillation equations

We use spherical coordinates (r,θ,ϕ) with the origin at the star’s centre,

whereby θ = 0 corresponds to its rotation axis. We give here the forced

version of the oscillation equations (with the forcing terms

or

or  )

used to calculate the input model for the relaxation code (where these terms are set equal

to zero).

)

used to calculate the input model for the relaxation code (where these terms are set equal

to zero).

Let us denote the velocity perturbation and displacement vector in the star by

v′ and ξ with

v′ = i σ ξ and denote

perturbed Eulerian quantities like pressure P′, density

ρ′, temperature T′, and the energy

flux vector F′ with a prime. The linearized hydrodynamic equations

governing the non-adiabatic oscillations of a star in the corotating frame are (Unno et al. 1989): ![\begin{eqnarray} \label{eqmot}\label{eq:1}&&\left[ \left(\frac{\partial}{\partial t} + \Omega_\mathrm{s} \frac{\partial } {\partial\varphi}\right) v'_i\right] \vec{e}_i+ 2 \vec{\Omega}_\mathrm{s} \times \vec{v'} +\frac{1}{\rho} \nabla P' - \frac{\rho'}{\rho^2} \nabla P = \mathcal{S}_F \\ \label{eqcont} && \left(\frac{\partial}{\partial t} + \Omega_\mathrm{s} \frac{\partial }{\partial\varphi}\right) \rho' + \nabla\cdot\left(\rho \vec{v'} \right) =0, \\ \label{eqe} && \left(\frac{\partial }{\partial t} + \Omega_\mathrm{s} \frac{\partial }{\partial \varphi}\right) \left[ s' + \vec{\xi}\cdot \nabla s \right]=-\frac{1}{\rho T} \nabla\cdot\vec{F'}, \\ \label{eqf}&& \frac{\vec{F'}}{F}=\left(\frac{\mathrm{d}T}{\mathrm{d}r}\right)^{-1} \left[ \left(\frac{3 T'}{T} -\frac{\rho'}{\rho} -\frac{\kappa'}{\kappa} \right) \nabla T + \nabla T' \right] \end{eqnarray}](/articles/aa/full_html/2013/11/aa21961-13/aa21961-13-eq36.png) where

we have added the forcing term

where

we have added the forcing term  ,

while ei are the unit vectors of our spherical

coordinate system, κ denotes the opacity of stellar material and

s its specific entropy. These perturbation equations represent,

respectively, conservation of momentum, conservation of mass and conservation of thermal

energy, while the last equation describes the perturbed radiative energy diffusion. For

simplicity we adopt the usual Cowling (1941)

approximation: i.e. we neglect perturbations to the gravitational potential caused by the

star’s oscillatory distortion. For the oscillation modes studied here this is an adequate

approximation.

,

while ei are the unit vectors of our spherical

coordinate system, κ denotes the opacity of stellar material and

s its specific entropy. These perturbation equations represent,

respectively, conservation of momentum, conservation of mass and conservation of thermal

energy, while the last equation describes the perturbed radiative energy diffusion. For

simplicity we adopt the usual Cowling (1941)

approximation: i.e. we neglect perturbations to the gravitational potential caused by the

star’s oscillatory distortion. For the oscillation modes studied here this is an adequate

approximation.

The unperturbed stellar model being spherically symmetric, we may choose a fixed value of

the azimuthal index m (plus the oscillation frequency σ

relative to the inertial frame) and separate the ϕ- and time part in the

oscillation equations given above. Thus we may write the solution for the displacement

vector etc. as  (5)From now on the

displacements and Eulerian perturbations are considered functions of r and

θ only and the above overline on ξ(r,θ)

and the factor ei(σt − mϕ) will be omitted in

the equations. Note that, in contrast to the usual practice, we consider m

to be always positive. Then σ > 0 corresponds to

wave motion in the positive ϕ direction and negative σ

corresponds to retrograde wave motion in the inertial frame.

(5)From now on the

displacements and Eulerian perturbations are considered functions of r and

θ only and the above overline on ξ(r,θ)

and the factor ei(σt − mϕ) will be omitted in

the equations. Note that, in contrast to the usual practice, we consider m

to be always positive. Then σ > 0 corresponds to

wave motion in the positive ϕ direction and negative σ

corresponds to retrograde wave motion in the inertial frame.

After defining a certain value for the azimuthal index m the star is

forced with a spherical harmonic component (l,m) whereby the order

l is chosen as the smallest integer for the adopted equatorial symmetry

(either odd or even). The oscillation frequency in the corotating frame is

and negative/positive

for retrograde/prograde modes in the frame corotating with the star. Obviously

and negative/positive

for retrograde/prograde modes in the frame corotating with the star. Obviously

corresponds to σ/m = Ωs,

i.e. the observer would see a mode with pattern speed equal to the angular rotation rate of

the star. Assuming a uniformly rotating star with angular velocity Ωs, the

radial, θ and ϕ components of the equation of motion can

be expressed as

corresponds to σ/m = Ωs,

i.e. the observer would see a mode with pattern speed equal to the angular rotation rate of

the star. Assuming a uniformly rotating star with angular velocity Ωs, the

radial, θ and ϕ components of the equation of motion can

be expressed as  The

spheroidal forcing terms on the right hand side of Eqs. (6)−(8) are applied in case

of a predominantly spheroidal (g- or p-) mode and are defined (using an arbitrary scaling

constant C) as

The

spheroidal forcing terms on the right hand side of Eqs. (6)−(8) are applied in case

of a predominantly spheroidal (g- or p-) mode and are defined (using an arbitrary scaling

constant C) as  When

a predominately toroidal (r-)mode is studied the horizontal forcing terms

When

a predominately toroidal (r-)mode is studied the horizontal forcing terms

and

and  in Eqs. (7) and (8) are (adequately) replaced by

in Eqs. (7) and (8) are (adequately) replaced by

and

and  with

with  where

for even (with l − m even) modes

l′ = l + 1 and for odd modes (with

l − m odd)

l′ = l − 1.

where

for even (with l − m even) modes

l′ = l + 1 and for odd modes (with

l − m odd)

l′ = l − 1.

These forcing terms are applied to search for resonant modes by varying the complex forcing frequency in the direction of maximum response. The found resonant modes are then used as input to obtain the corresponding free oscillation modes.

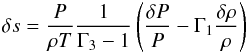

The equation of continuity (2) can be

expressed as  (9)After

applying the thermodynamic relation

(9)After

applying the thermodynamic relation  (where

δs denotes a Langrangian entropy perturbation) in terms of

Chandrasekhar’s adiabatic exponents Γ1 and Γ3, the energy Eq. (3) can be rewritten

(where

δs denotes a Langrangian entropy perturbation) in terms of

Chandrasekhar’s adiabatic exponents Γ1 and Γ3, the energy Eq. (3) can be rewritten ![\begin{eqnarray} \frac{1}{\Gamma_1} \frac{P'}{P} - \frac{\rho^{\prime}}{\rho} - \mathcal{A} \, \xi_{r} = {\rm{i}} \,\Lambda \left[ \nabla \cdot \left( \frac{\vec{F'}}{F}\right) + {{{\rm d} \ln F}\over {{\rm d} r}} \left( \frac{F'_r}{F}\right) \right] \label{EQ5} \end{eqnarray}](/articles/aa/full_html/2013/11/aa21961-13/aa21961-13-eq71.png) (10)where

F is the unperturbed (radial) energy flux. The Schwarzschild discriminant

(10)where

F is the unperturbed (radial) energy flux. The Schwarzschild discriminant

and characteristic diffusion length Λ are defined by:

and characteristic diffusion length Λ are defined by:  The

radial and horizontal components of the perturbed energy flux follow from Eq. (4) as

The

radial and horizontal components of the perturbed energy flux follow from Eq. (4) as  After

substituting

After

substituting  and

and

in the

divergence term of Eq. (10) and using the

equation of state (14) (where the

χ’s stand for the usual logarithmic partial derivatives of the pressure

and

in the

divergence term of Eq. (10) and using the

equation of state (14) (where the

χ’s stand for the usual logarithmic partial derivatives of the pressure

and  is of importance in the layers outside the convective core with a composition gradient):

is of importance in the layers outside the convective core with a composition gradient):

(14)to

eliminate ρ′ from Eqs. (6)−(11) we are left with six

equations in the six unknowns

(ξr/Rs),

(ξθ/Rs),

(ξϕ/Rs),

(P′/P),

(T′/T) and

(14)to

eliminate ρ′ from Eqs. (6)−(11) we are left with six

equations in the six unknowns

(ξr/Rs),

(ξθ/Rs),

(ξϕ/Rs),

(P′/P),

(T′/T) and

.

.

In convective regions, i.e. in the convective core and convective shell at the surface of

our 5.4 M⊙ B-star, we add (turbulent) viscous terms

(15)to

the equations of motion (6)−(8) where the subindex i stands

for r, θ or ϕ and the kinematic viscosity

ζ is calculated with simple mixing length theory. The mixing length

λ = 1.5 HP and convective

velocities are taken from the stellar evolution code MESA that was used to calculate the

unperturbed equilibrium model. The kinematic viscosity ζ is corrected

(reduced) for timescale mismatch between convective- and oscillatory motions according to

the prescription of Goldreich & Keeley (1977)

and attains a maximum value of about 1013 cm2/s near the stellar

centre. The turbulent viscous terms in the convective regions tend to damp the induced very

short wavelength oscillations (Savonije & Papaloizou

1997).

(15)to

the equations of motion (6)−(8) where the subindex i stands

for r, θ or ϕ and the kinematic viscosity

ζ is calculated with simple mixing length theory. The mixing length

λ = 1.5 HP and convective

velocities are taken from the stellar evolution code MESA that was used to calculate the

unperturbed equilibrium model. The kinematic viscosity ζ is corrected

(reduced) for timescale mismatch between convective- and oscillatory motions according to

the prescription of Goldreich & Keeley (1977)

and attains a maximum value of about 1013 cm2/s near the stellar

centre. The turbulent viscous terms in the convective regions tend to damp the induced very

short wavelength oscillations (Savonije & Papaloizou

1997).

2.1. Boundary conditions

We apply the usual boundary conditions e.g. Unno et al.

(1989) at the stellar centre. At the stellar surface we apply Stefan-Boltzmann’s

law  and put

and put  . At the

stellar equator we apply the adopted (anti)symmetry of (odd) even modes, at the rotation

axis we use the expansion corresponding with the adopted spherical harmonics (or their

derivative) used in the forcing.

. At the

stellar equator we apply the adopted (anti)symmetry of (odd) even modes, at the rotation

axis we use the expansion corresponding with the adopted spherical harmonics (or their

derivative) used in the forcing.

2.2. Numerical method

Equations (6)−(11) are expressed as finite difference

equations on a (r,θ) grid with 1512 radial grid points and 130 grid

points in the interval  . The solution in the

southern hemisphere follows from the adopted parity of the studied oscillation mode. In

the radial direction the MESA code’s staggered mesh is adopted: two cell boundaries where

we define ξ and

. The solution in the

southern hemisphere follows from the adopted parity of the studied oscillation mode. In

the radial direction the MESA code’s staggered mesh is adopted: two cell boundaries where

we define ξ and  , while

P′ and T′ are defined at the

cell centre in between. In the numerical procedure three grid levels (both for cell

centres and boundaries) are used to allow treatment of second order derivatives in the

viscosity terms and the energy diffusion equation. In the θ direction we

use an equidistant mesh, again with three levels per cell to allow the treatment of second

order derivatives.

, while

P′ and T′ are defined at the

cell centre in between. In the numerical procedure three grid levels (both for cell

centres and boundaries) are used to allow treatment of second order derivatives in the

viscosity terms and the energy diffusion equation. In the θ direction we

use an equidistant mesh, again with three levels per cell to allow the treatment of second

order derivatives.

The equations of motion and (radial) flux equation are evaluated at the cell boundaries, while the equations of continuity and energy are evaluated at cell centres. Starting (at radial level 2) and applying the 6 or 7 (relaxation version of code) difference equations by moving from the rotation axis towards the equator and using the boundary conditions at the centre all variables at radial level 1, (i.e. r = 0) can be eliminated. By matrix inversions one can set up relations between the unknown perturbation variables at radial level 2 and 3 until the stellar equator is reached. By finally applying the known parity of the oscillation to eliminate the unknown perturbations at the gridpoint beyond the equator it is possible to express each perturbation variable at radial level 2 in terms of (all) the variables at radial level 3. One can now repeat the same procedure from rotation axis to stellar equator at one higher radial level and so on until the surface is reached. After applying the surface boundary conditions for the last stride from rotation axis to equator we obtain the solution at the equator for r = Rs. By backsubstitution in the stored recurrence relations one can work back in reverse order to find the perturbations throughout the 2D stellar oscillation model.

For a measure of the oscillatory response to the forcing the pressure perturbation is

integrated over the upper hemisphere of the star:  with

Rcc the convective core boundary; l and

m correspond to the applied forcing. By stepping through frequency

space and each time recalculating | ℛ | until a maximum response is passed we search for

resonances. We then zoom in onto the resonance and use the resonant solution as input for

the relaxation code. For this we use the same oscillation equations but without forcing

terms and consider the complex oscillation frequency

with

Rcc the convective core boundary; l and

m correspond to the applied forcing. By stepping through frequency

space and each time recalculating | ℛ | until a maximum response is passed we search for

resonances. We then zoom in onto the resonance and use the resonant solution as input for

the relaxation code. For this we use the same oscillation equations but without forcing

terms and consider the complex oscillation frequency

as an extra

unknown, thereby introducing non-linear

as an extra

unknown, thereby introducing non-linear  terms. In most

cases it requires about ten iterations to converge to the free oscillation mode. The sign

of the imaginary part of

terms. In most

cases it requires about ten iterations to converge to the free oscillation mode. The sign

of the imaginary part of  determines

whether the found mode is stable

determines

whether the found mode is stable  or not

or not

. The code was written in Fortran

90 and parallelized to work on multicore machines. On a 16 core node of SARA’s national

compute cluster LISA (Amsterdam) the code takes about 3 (4) minutes to calculate one

iteration for the forced (free) version of the code.

. The code was written in Fortran

90 and parallelized to work on multicore machines. On a 16 core node of SARA’s national

compute cluster LISA (Amsterdam) the code takes about 3 (4) minutes to calculate one

iteration for the forced (free) version of the code.

2.3. Visibility ( )

of a mode

)

of a mode

Since the observations with CoRoT and Kepler deliver detailed

photometric information of pulsating stars it is desirable to have a measure of the

brightness of the unstable oscillation modes found with our new code. The actual amplitude

of the calculated modes can not be determined without greatly increasing the scope and

computer requirements of the study by introducing nonlinear effects and coupling between

oscillation modes. Because this is beyond the scope of the current study we have to use a

simpler way to compare with the observations. There is another important factor that

determines the photometric variability: the contribution by the various radiating

oscillating surface regions partially cancel, depending on the type of mode and this

visibility effect can be easily estimated and used to discriminate between different modes

and compare observations with the calculated modes. Recently Reese et al. (2013) have also defined and calculated a (more refined)

visibility of modes. They have taken the stellar flattening into account, but their mode

calculations are adiabatic. We use the diffusion Eq. (4) for radiative energy transport (or mixing length theory for

convective energy transport) for a fully non-adiabatic treatment up to the stellar

“surface” and apply (Sect. 2.1) Stefan-Boltzmann’s

law  at the

outer boundary, neglecting details of the stellar atmosphere.

at the

outer boundary, neglecting details of the stellar atmosphere.

First the (complex) perturbed radial flux is normalized for the particular mode by

dividing it by the maximum modulus attained at some θ-value. Suppose the

observer’s inclination angle is i and its azimuthal position angle is

given by ϕobs = 0. At a point (θ,ϕ) on the

stellar surface the time-dependent real value of the Lagrangian perturbation of the radial

surface flux can be expressed as  with

σr = Re(σ) is the real

part of the oscillation frequency and

with

σr = Re(σ) is the real

part of the oscillation frequency and  Integrating

(numerically) over the area of the stellar hemisphere visible for the observer and

dividing by the effective area of the stellar disc we obtain

Integrating

(numerically) over the area of the stellar hemisphere visible for the observer and

dividing by the effective area of the stellar disc we obtain

![\begin{eqnarray*} \mathcal{I}= \frac{1}{\pi} \int \int \left[c_{1} \cos{\left(\sigma_r t\right)}+ c_{2} \sin{\left(\sigma_r t \right)} \right] \: \cos{\gamma} \: \: \sin{\theta}\, {\rm d} \theta \, {\rm d} \varphi \end{eqnarray*}](/articles/aa/full_html/2013/11/aa21961-13/aa21961-13-eq116.png) with

cosγ = [cosi cosθ + sini sinθ cosϕ]

the projection factor. We rewrite this integral as

with

cosγ = [cosi cosθ + sini sinθ cosϕ]

the projection factor. We rewrite this integral as  where

α is a phase factor. The visibility of the mode is defined as the

oscillation amplitude (by normalization a number between 0 and 1)

where

α is a phase factor. The visibility of the mode is defined as the

oscillation amplitude (by normalization a number between 0 and 1)

(16)In this paper we adopt an

inclination i = 25 degrees for the observer, as estimated for the star HD

43317 by Pápics et al. (2012). The largest

visibility (0.54) occurs for the odd m = 0 g-mode with 19 radial nodes

and frequeny 1.09 cpd. The radial nodes are counted for a fixed value of

θ.

(16)In this paper we adopt an

inclination i = 25 degrees for the observer, as estimated for the star HD

43317 by Pápics et al. (2012). The largest

visibility (0.54) occurs for the odd m = 0 g-mode with 19 radial nodes

and frequeny 1.09 cpd. The radial nodes are counted for a fixed value of

θ.

3. Results

Stability calculations were performed for oscillation modes with m-values

of 0, 1 and 2 focussed on the frequency range <4.5 cpd in the

inertial frame where the brightest lines occur. Table 1 shows the frequency ranges where unstable modes are found in both the stellar

and inertial frame. From now on all frequencies  in the

corotating frame are listed in units of the critical rotation frequency

in the

corotating frame are listed in units of the critical rotation frequency

.

Frequencies listed as cycles per day (cpd) are always in the inertial frame. All plots

correspond to free oscillation modes, unless stated otherwise (Fig. 3).

.

Frequencies listed as cycles per day (cpd) are always in the inertial frame. All plots

correspond to free oscillation modes, unless stated otherwise (Fig. 3).

3.1. Used coding (l, τ, m) for the oscillation modes

As indicated above we apply forcing terms defined by spherical harmonic indices (l,m) in the oscillation equations and search for resonances with modes compatible with the thus imposed behaviour near the rotation axis and symmetry about the stellar equator. For a given m-value and adopted parity at the equator we choose for the applied forcing the lowest compatible l-value, for example for m = 1 we choose either l = 1 (even modes) or l = 2 (odd modes). The oscillation of an odd m = 1 mode includes components l = 2,4,6 etc. In the following modes will be described by three numbers given in parentheses, like (202) or (211) where the first number denotes the l-value and the third the m-value of the initially applied forcing. The middle number (τ) is either 0 (“spheroidal” forcing) or 1 (“toroidal” forcing). The (211) mode is thus an odd r-mode with m = 1. We use the same coding for the free oscillation modes as they have the same symmetries as the corresponding forced solution from which they were derived. The perturbations, like P′/P or the components of the displacement vector ξ, are complex quantities as they describe the amplitude and phase of the oscillation.

Frequency ranges where unstable modes are found: respectively in stellar frame (in units of Ωc) and after ; in inertial frame (in cycles per day).

Our simple coding (l, τ, m) for the

calculated modes indicates the basic symmetries, but this gives no information about the

actual harmonic content of the mode. The Coriolis force generates components with higher

l-values, see Fig. 1 and modifies

the gravity modes which become “gravito-inertial modes” and contain in principle an

infinite number of spherical harmonic components l for a given

m. In practice their number is evidently limited by the grid

resolution. For  the consecutive unstable

g-modes with given m-value are often of different harmonic content in the

sense that the l-value of the dominant (mass average over star)

Fourier-Legendre coefficient

(Cl)max fluctuates (and the

number of radial nodes jumps about) between consecutive modes. However, for about

the consecutive unstable

g-modes with given m-value are often of different harmonic content in the

sense that the l-value of the dominant (mass average over star)

Fourier-Legendre coefficient

(Cl)max fluctuates (and the

number of radial nodes jumps about) between consecutive modes. However, for about

the high radial order

components are heavily damped and consecutive unstable modes are usually in monotonic

radial order with a fixed dominant l-value and produce the striking

sequences of (100) and (200) g-modes in Fig. 5.

the high radial order

components are heavily damped and consecutive unstable modes are usually in monotonic

radial order with a fixed dominant l-value and produce the striking

sequences of (100) and (200) g-modes in Fig. 5.

In the figures showing components ξθ and ξϕ of the displacement vector we plot the modulus of these complex quantities.

|

Fig. 1 Modulus of the horizontal components ξθ (left panels) and ξϕ(right panels) of the displacement vector versus θ/π at some radial meshpoints in the intermediate region outside the convective core (upper panels) and near the stellar surface, including the convective shell, (lower two panels) for a (200) g-mode with frequency 1.713 cpd in the inertial frame. The arrow indicates the critical (co)latitude θc. |

3.2. Gravito-inertial modes

For frequencies in the inertial range  gravity waves are

substantially modified by rotation and sometimes called gravito-inertial waves. These

waves can only propagate between the critical (co)latitudes θc

and π − θc, i.e. in the “equatorial belt” of

the rotating star. The critical (co)latitude θc is defined by

gravity waves are

substantially modified by rotation and sometimes called gravito-inertial waves. These

waves can only propagate between the critical (co)latitudes θc

and π − θc, i.e. in the “equatorial belt” of

the rotating star. The critical (co)latitude θc is defined by

. In the sections below we

will simply speak of g-modes when we mean these rotationally modified gravity modes.

. In the sections below we

will simply speak of g-modes when we mean these rotationally modified gravity modes.

Gravito-inertial waves were studied by Savonije et al. (1995) and Papaloizou & Savonije (1997) in tidal forcing calculations of a massive ZAMS star. Dintrans et al. (1999) studied gravito-inertial waves for a stably stratified spherical shell in the Boussinesq approximation. In the latter study these waves were shown to have attractors with focussing on the critical surfaces. However, a small diffusion as found in a normal star cancels their focussing power. Several new studies of rotational (inertial) waves in fully convective or barotropic stars/planets have appeared, see Papaloizou & Ivanov (2010), Ivanov & Papaloizou (2010) and Rieutord & Valdettaro (2010).

Neiner et al. (2012) claim that gravito-inertial modes are excited by stochastic effects in the hot Be-star HD 51452 as the κ-mechanism is not effective in such a hot star. They suggest that the gravito-inertial modes found by Pápics et al. (2012) in HD 43317 are also of stochastic nature. However, our current results show that in HD 43317 these g-modes can be driven by the κ-mechanism.

|

Fig. 2 Modulus of the horizontal components

(ξθ and

ξϕ) of the displacement vector

versus θ/π at some radial

meshpoints in the intermediate region outside the convective core (upper

panels) and near the stellar surface (lower two panels)

for a (100) g-mode with frequency |

3.3. r-modes

The Coriolis force also enables the occurrence of r-modes, first studied as purely toroidal modes in stars by Papaloizou & Pringle (1978). Using the “traditional approximation” it was discovered by Savonije (2005) that a class of r-modes (“quasi g-modes”) show sufficient density and temperature variations to be destabilized by the κ-mechanism. Townsend (2005) came almost simultaneously with a similar analysis to the same conclusion, while Lee (2006) investigated the stability of these “buoyant” r-modes in more detail with the method of spherical harmonic expansions. We do find a sequence of unstable buoyant r-modes in our calculations, in perfect radial order.

3.4. Short wavelengths in the stellar interior

As noted by Papaloizou & Savonije (1997)

very short wavelength response is excited in the convective core by tidal forcing with

frequencies  (“inertial

range”). These inertial waves can leak out of the core and excite short wavelength gravity

waves. It is interesting that also in the free oscillation solutions the Coriolis force

induces short wavelength oscillations near the boundary of the convective core and in the

intermediate regions outside the convective core. We find that these waves can propagate

quite far out into the star, see Fig. 1. One may

wonder whether the forced solution that is used as input model is the cause of the short

wavelengths in the free oscillation solution. To check this we applied a high viscosity

ζ = 1.0 × 1020 cm2/s throughout the star during

the first iteration in which the complex frequency

(“inertial

range”). These inertial waves can leak out of the core and excite short wavelength gravity

waves. It is interesting that also in the free oscillation solutions the Coriolis force

induces short wavelength oscillations near the boundary of the convective core and in the

intermediate regions outside the convective core. We find that these waves can propagate

quite far out into the star, see Fig. 1. One may

wonder whether the forced solution that is used as input model is the cause of the short

wavelengths in the free oscillation solution. To check this we applied a high viscosity

ζ = 1.0 × 1020 cm2/s throughout the star during

the first iteration in which the complex frequency  is kept fixed. The

high viscosity makes the first iterated solution smooth like the disturbances in Fig.

2. But the converged free solution appears

independent of this smoothing, again with a significant short wavelength component in the

stellar interior.

is kept fixed. The

high viscosity makes the first iterated solution smooth like the disturbances in Fig.

2. But the converged free solution appears

independent of this smoothing, again with a significant short wavelength component in the

stellar interior.

The short wavelength oscillations are limited to the g-mode propagation cavity, i.e. the equatorial belt between the two critical latitudes. Further out for r/Rs > 0.5 they become weaker and finally disappear near r/Rs ≃ 0.7. This is far below the driving region for the κ-mechanism which is located near r/Rs ≃ 0.96 where T ≃ 2 × 105 K.

For frequencies just outside the inertial range, where the Coriolis force is still significant, it generates higher order spherical harmonic components but the short wavelengths are completely absent in the star, see Fig. 2.

|

Fig. 3 Modulus of the horizontal components

(ξθ and

ξϕ) of the displacement vector

versus θ/π at some radial

meshpoints in the stellar surface region, including the convective shell, for the

(100) g-mode with |

3.5. Jump in ξh at critical latitude in surface layers (with forcing)

For all studied oscillation modes with  the solutions

with forcing show in the surface region an almost discontinuous jump in the horizontal

components of the displacement vector at the critical latitude. For “buoyant” r-modes this

jump occurs at the outer boundary of the convective surface shell, while for g-modes the

jump is often generated at the shell’s inner boundary. Figure 3 shows the horizontal components of the displacements vector in the

surface region of a (100) g-mode for both the forced and free solution. Apparently the

discontinuous behaviour at the critical latitudes is generated by the applied forcing, it

is absent in the free solutions. Terquem et al.

(1998), in their study of the l = m = 2 tides

in a non-rotating solar type star, explained the found horizontal displacement

ξh’s tendency for discontinuous behaviour near a convective

boundary as the consequence of the fluid becoming locally barotropic when the

Brunt-Väisälä frequency | N2| = 0. In the current

calculations with rotation the discontinuity (always focussed at the critical latitude) is

also generated at a convective boundary (of the surface shell) and propagates towards the

stellar surface. In the free solutions the jump in ξh in the

surface layers is absent, but for g-modes ξh does often show

in the layers beyond the convective shell small amplitude short wavelength disturbances

near the critical latitude θc and a spike or dip at

θc.

the solutions

with forcing show in the surface region an almost discontinuous jump in the horizontal

components of the displacement vector at the critical latitude. For “buoyant” r-modes this

jump occurs at the outer boundary of the convective surface shell, while for g-modes the

jump is often generated at the shell’s inner boundary. Figure 3 shows the horizontal components of the displacements vector in the

surface region of a (100) g-mode for both the forced and free solution. Apparently the

discontinuous behaviour at the critical latitudes is generated by the applied forcing, it

is absent in the free solutions. Terquem et al.

(1998), in their study of the l = m = 2 tides

in a non-rotating solar type star, explained the found horizontal displacement

ξh’s tendency for discontinuous behaviour near a convective

boundary as the consequence of the fluid becoming locally barotropic when the

Brunt-Väisälä frequency | N2| = 0. In the current

calculations with rotation the discontinuity (always focussed at the critical latitude) is

also generated at a convective boundary (of the surface shell) and propagates towards the

stellar surface. In the free solutions the jump in ξh in the

surface layers is absent, but for g-modes ξh does often show

in the layers beyond the convective shell small amplitude short wavelength disturbances

near the critical latitude θc and a spike or dip at

θc.

|

Fig. 4 Visibility integrals |

3.6. Visibility of unstable modes

As noted above, the best one can do with linear stability calculations is to compare the mode’s “visibility” with observed photometric amplitudes. A first study of non-linear mode coupling in rotating B-stars has been made by Lee (2012) applying selection rules for three mode coupling derived in a study by Schenk et al. (2002). Non-linear interaction between an unstable mode and two stable daughter modes will lower the unstable mode’s amplitude and can cause the excitation of the two (linearly) stable modes (processes that are ignored in our calculations). Further work is required to understand and apply non-linear interactions between modes in a rotating star.

In the current work we can do no better than compare the observed light variations with the visibility of the found unstable modes and see whether on this basis one can identify (some of) the observed photometric variations. In Fig. 5 we have plotted the photometric amplitudes (black lines) versus frequency in the inertial frame, as determined by Pápics et al. (2012) and superposed various symbols representing the here calculated visibility of unstable modes. As expected, the unstable modes with the lowest m-values (m = 0 and m = 1) have the highest visibility. For the adopted observer’s inclination angle of 25 degrees the parity at the equator of a m = 0 or 1 mode makes hardly any difference in its visibility. But in Fig. 5 it can be seen that m = 2 even g-modes do have larger visibility than the odd g-modes. Modes with m ≥ 3 have negligible visibility and are ignored. Figure 4 shows that the unstable odd axisymmetric (100) g-modes suffer almost no cancellation effect over the θ-range resulting in a high visibility.

The unstable even (200) axisymmetric g-modes have three θ-nodes in the θ-range 0–π/2 and the consequent cancellation effects (Fig. 4) result in lower visibility. They cover a few observed moderately bright lines. The remaining (100) g-modes with smaller visibility also suffer cancellation as a consequence of two or three nodes in θ. The m = 1 g-modes with visibilities in the range 0.1−0.2 miss a clear link with observed counterparts, while the even m = 2 g-modes could correspond with observed weaker “lines” in Fig. 5. We find only one unstable (211) r-mode at 0.47 cpd with moderate visibility (0.19) and a sequence of five unstable (312) r-modes near 2 cpd with negligible visibility. The (312) r-modes suffer both from strong cancellation in the ϕ integration and from cancellation in θ due to the odd parity at the equator, see Fig. 4.

|

Fig. 5 Visibility of all overstable modes vs. frequency in inertial frame (cpd) projected on Pápics list of observed photometric amplitudes A (vertical black lines) vs. frequency. Adopted inclination is 25 degrees. The photometric amplitudes are here normalized to a maximum of 0.5. Triangles correspond to odd-, circles to even g-modes and squares to (odd) r-modes. A cross inside a symbol means the g-mode is retrograde in the inertial frame. Colour definition: red m = 0, green m = 1 and blue m = 2. |

It is consolidating that the found unstable modes with the highest visibility lie close to the frequencies at which the largest photometric amplitudes are observed and correspond even to the observed single moderately strong line located further out at 4.33 cpd.

3.7. Constant period spacings

Pápics et al. (2012) have searched for (nearly) constant period spacings in the light curve of HD 43317 and found a nearly equidistant series of ten peaks with an average period spacing of ΔP = 0.07337 day and another series of seven components with average spacing ΔP = 0.07385 day for which they claim the semi-constant spacing is not due to chance. Similar spacings were found for a slow rotator HD 50230 (Degroote et al. 2010). We determined the period spacings of modes of a given value of m and do not find nearly constant period spacings of this kind. Most of the period spacings are smaller than at least a factor 4−5 and mostly quite irregular. The current calculations have thus no explanation for the inferred occurrence of (almost) constant period spacings.

4. Conclusions

We have performed calculations of a rapidly rotating B-star in which the Coriolis force is dominant or at least substantial with a new method to find unstable oscillation modes. We have searched for unstable modes with azimuthal index m = 0,1 and 2 and defined the visibility of modes by estimating the cancellation effect of the different (perturbed) radiating parts at the stellar surface as seen by the observer. By comparing the observed photometric variability (frequencies and brightness) of HD 43317 with the thus determined visibility of modes in Fig. 5 it is reinforcing that one can discern a global similarity between the two. The most striking is that observationally inferred frequencies corresponding with the largest photometric amplitudes in Fig. 5 are close to those of the calculated modes with the highest visibility: the odd axisymmetric g-modes. Even the bright line at 4.33 cpd appears to almost coincide with an odd axisymmetric mode. It seems plausible to identify the observed strongest photometric variations in HD 43317 as unstable axisymmetric g-modes. The connection between the unstable odd m = 1 g-modes with frequency below 0.8 cpd and between 2 and 3 cpd, all with moderately high visibility, and the observed photometric variability is less clear. In most cases no substantial photometric variation is seen for these frequencies. But, as noted above, the neglected non-linear interactions and differential rotation may play a role.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Bill Paxton for his cooperation in obtaining a smooth composition profile in the MESA results and the referee for critical remarks which have improved the paper.

References

- Auvergne, M., Bodin, P., & Boisnard, L., et al. 2009, A&A, 506, 411 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Baglin, A., Auvergne, M., Barge, P., Deleuil, M., & Michel, E. E. A. 2009, IAU Symp., 253, 71 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Borucki, W., Koch, D., Batalha, N., et al. 2009, IAU Symp., 253, 289 [Google Scholar]

- Cowling, T. 1941, MNRAS, 267, 367 [Google Scholar]

- Degroote, P., Aerts, C., Baglin, A., et al. 2010, Nature, 464, 259 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dintrans, B., Rieutord, M., & Valdettaro, L. 1999, J. Fluid Mech., 398, 271 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa, L. F., & Rieutord, M. 2013, A&A, 552, A35 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Goldreich, P., & Keeley, D. 1977, ApJ, 211, 934 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov, P., & Papaloizou, J. 2010, MNRAS, 407, 1609 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, U. 2006, MNRAS, 365, 677 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, U. 2012, MNRAS, 420, 2387 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Neiner, C., Floquet, M., Samadi, R., et al. 2012, A&A, 546, A47 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Ouazzani, R.-M., Dupret, M.-A., & Reese, D. R. 2012, A&A, 547, A75 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Papaloizou, J., & Ivanov, P. 2010, MNRAS, 407, 1631 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Papaloizou, J., & Pringle, J. 1978, MNRAS, 182, 423 [Google Scholar]

- Papaloizou, J., & Savonije, G. 1997, MNRAS, 291, 651 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pápics, P., Briquet, M., Baglin, A., et al. 2012, A&A, 542, A55 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Paxton, B., Cantiello, M., Arras, P., et al. 2013, ApJS, 208, 4 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Reese, D. R., Prat, V., Barban, C., van ’t Veer-Menneret, C., & MacGregor, K. B. 2013, A&A, 550, A77 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Rieutord, M., & Valdettaro, L. 2010, J. Fluid Mech., 643, 363 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Savonije, G. J. 2005, A&A, 443, 557 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Savonije, G., & Papaloizou, J. 1997, MNRAS, 291, 633 [Google Scholar]

- Savonije, G., Papaloizou, J., & Alberts, F. 1995, MNRAS, 277, 471 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Schenk, A., Arras, P., Flanagan, E., Teukolsky, S., & Wasserman, I. 2002, Phys. Rev. D, 65, 24001 [Google Scholar]

- Terquem, C., Papaloizou, J., Nelson, R., & Lin, D. 1998, ApJ, 502, 788 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend, R. 2005, MNRAS, 364, 573 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend, R., & Teitler, S. 2013, MNRAS, in press [arXiv:1308.2965] [Google Scholar]

- Unno, W., Osaki, Y., Ando, H., Saio, H., & Shibahashi, H. 1989, Non-radial Oscillations of Stars (University of Tokyo Press) [Google Scholar]

- Valsecchi, F., Farr, W., Willems, B., Rasio, F., & Kalogera, V. 2013, ApJ, 773, 39 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

All Tables

Frequency ranges where unstable modes are found: respectively in stellar frame (in units of Ωc) and after ; in inertial frame (in cycles per day).

All Figures

|

Fig. 1 Modulus of the horizontal components ξθ (left panels) and ξϕ(right panels) of the displacement vector versus θ/π at some radial meshpoints in the intermediate region outside the convective core (upper panels) and near the stellar surface, including the convective shell, (lower two panels) for a (200) g-mode with frequency 1.713 cpd in the inertial frame. The arrow indicates the critical (co)latitude θc. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 2 Modulus of the horizontal components

(ξθ and

ξϕ) of the displacement vector

versus θ/π at some radial

meshpoints in the intermediate region outside the convective core (upper

panels) and near the stellar surface (lower two panels)

for a (100) g-mode with frequency |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 3 Modulus of the horizontal components

(ξθ and

ξϕ) of the displacement vector

versus θ/π at some radial

meshpoints in the stellar surface region, including the convective shell, for the

(100) g-mode with |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 4 Visibility integrals |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 5 Visibility of all overstable modes vs. frequency in inertial frame (cpd) projected on Pápics list of observed photometric amplitudes A (vertical black lines) vs. frequency. Adopted inclination is 25 degrees. The photometric amplitudes are here normalized to a maximum of 0.5. Triangles correspond to odd-, circles to even g-modes and squares to (odd) r-modes. A cross inside a symbol means the g-mode is retrograde in the inertial frame. Colour definition: red m = 0, green m = 1 and blue m = 2. |

| In the text | |

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.