| Issue |

A&A

Volume 521, October 2010

Herschel/HIFI: first science highlights

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | L17 | |

| Number of page(s) | 4 | |

| Section | Letters | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201015088 | |

| Published online | 01 October 2010 | |

Herschel/HIFI: first science highlights

LETTER TO THE EDITOR

C+ detection of warm dark gas in diffuse clouds![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

W. D. Langer - T. Velusamy - J. L. Pineda - P. F. Goldsmith - D. Li. - H. W. Yorke

Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, 4800 Oak Grove Drive, Pasadena, CA 91109-8099, USA

Received 31 May 2010 / Accepted 9 July 2010

Abstract

We present the first results of the Herschel open time key program, Galactic Observations of Terahertz C+ (GOT C+) survey of the [CII] 2P3/2-2P1/2 fine-structure line at 1.9 THz (158 ![]() m) using the HIFI instrument on Herschel.

We detected 146 interstellar clouds along sixteen lines-of-sight

towards the inner Galaxy. We also acquired HI and CO isotopologue data

along each line-of-sight for analysis of the physical conditions in

these clouds. Here we analyze 29 diffuse clouds (

m) using the HIFI instrument on Herschel.

We detected 146 interstellar clouds along sixteen lines-of-sight

towards the inner Galaxy. We also acquired HI and CO isotopologue data

along each line-of-sight for analysis of the physical conditions in

these clouds. Here we analyze 29 diffuse clouds (

![]() mag)

in this sample characterized by having [CII] and HI emission, but no

detectable CO. We find that [CII] emission is generally stronger than

expected for diffuse atomic clouds, and in a number of sources is much

stronger than anticipated based on their HI column density. We show

that excess [CII] emission in these clouds is best explained by the

presence of a significant diffuse warm H2, dark gas, component. This first [CII] 158

mag)

in this sample characterized by having [CII] and HI emission, but no

detectable CO. We find that [CII] emission is generally stronger than

expected for diffuse atomic clouds, and in a number of sources is much

stronger than anticipated based on their HI column density. We show

that excess [CII] emission in these clouds is best explained by the

presence of a significant diffuse warm H2, dark gas, component. This first [CII] 158 ![]() m

detection of warm dark gas demonstrates the value of this tracer for

mapping this gas throughout the Milky Way and in galaxies.

m

detection of warm dark gas demonstrates the value of this tracer for

mapping this gas throughout the Milky Way and in galaxies.

Key words: ISM: atoms - ISM: molecules - ISM: structure

1 Introduction

Interstellar gas plays a crucial role in the life cycle of Galaxies

providing the material for star formation and as a repository of gas

ejected by stars as part of their evolution. The diffuse atomic gas has

been mapped in HI 21 cm surveys, and dense molecular H2 clouds have been mapped indirectly with molecular tracers, primarily 12CO (cf. Dame et al. 2001) and in more limited surveys in its isotopologues. Missing, however, is a widespread spectral tracer of H2 not located in regions with conditions appropriate to form CO, the so-called ``dark gas'' (Grenier et al. 2005). One of the best candidates for this tracer is C+, which is widely distributed in the Galaxy as shown by COBE FIRAS all sky (Bennett et al. 1994) and BICE inner Galaxy (Nakagawa et al. 1998) observations of its 158 ![]() m 2P3/2-2P1/2

fine structure line. In addition, [CII] is a density- and

temperature-sensitive probe of diffuse clouds and photon dominated

regions (PDRs). While COBE revealed that this line is the brightest

far-IR line in the Galaxy, low spectral (

m 2P3/2-2P1/2

fine structure line. In addition, [CII] is a density- and

temperature-sensitive probe of diffuse clouds and photon dominated

regions (PDRs). While COBE revealed that this line is the brightest

far-IR line in the Galaxy, low spectral (

![]() km s-1) and spatial (7

km s-1) and spatial (7![]() )

resolution could not reveal individual cloud components. BICE data, while slightly better in this respect (175 km s-1 and 15

)

resolution could not reveal individual cloud components. BICE data, while slightly better in this respect (175 km s-1 and 15![]() ),

is not adequate to resolve clouds along the line-of-sight (LOS).

Heterodyne receivers are critical to provide the necessary velocity

resolution to identify and study individual clouds along the LOS;

however, prior to operation of the HIFI instrument (de Graauw et al. 2010) on the Herschel (Pilbratt & et al. 2010) only a handful of high spectral resolution [CII] spectra were available from bright HII regions

(c.f. Boreiko & Betz 1991).

),

is not adequate to resolve clouds along the line-of-sight (LOS).

Heterodyne receivers are critical to provide the necessary velocity

resolution to identify and study individual clouds along the LOS;

however, prior to operation of the HIFI instrument (de Graauw et al. 2010) on the Herschel (Pilbratt & et al. 2010) only a handful of high spectral resolution [CII] spectra were available from bright HII regions

(c.f. Boreiko & Betz 1991).

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=16cm,angle=0]{15088fg1.eps}

\vspace*{-2mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/13/aa15088-10/Timg16.png)

|

Figure 1:

[CII] spectra obtained with Herschel/HIFI for the GOT C+ program at

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

Here we report the first results of a large-scale survey of [CII]

1.9 THz line emission in the Galaxy being conducted under the Herschel open time key program, Galactic Observations of Terahertz C+ (GOT C+). The full GOT C+ program will observe about 900 LOS in the Galaxy, divided into four subprograms (Langer et al. 2010): 1) a Galactic disk uniform volume sampling in longitude (covering all 360![]() ), at b = 0,

), at b = 0, ![]() 0.5

0.5![]() ,

,

![]() 1

1![]() ,

and

,

and ![]() 2

2

![]() ;

2) strip maps in the inner Galaxy; 3) a sampling of Heiles

high-latitude clouds studied in absorption; and, 4) the Galactic

warp in the outer Galaxy. To date we have obtained high spectral

resolution spectra of [CII] towards 16 LOS towards the inner Galaxy

near longitude 340

;

2) strip maps in the inner Galaxy; 3) a sampling of Heiles

high-latitude clouds studied in absorption; and, 4) the Galactic

warp in the outer Galaxy. To date we have obtained high spectral

resolution spectra of [CII] towards 16 LOS towards the inner Galaxy

near longitude 340

![]() (5 LOS) and 20

(5 LOS) and 20

![]() (11

LOS) taken during the performance verification phase and priority

science program. In this small sample (< 2% of the complete

GOT C+ survey) we detected 146 clouds in [CII] emission. These

data cover four broad categories of clouds as defined by their HI,

[CII], and CO signatures: a) diffuse atomic clouds with high

HI to [CII] intensity ratio and no detectable CO; b) diffuse molecular

clouds with relatively low HI to [CII] intensity ratio (due to

relatively strong [CII]) and no 12CO emission (

(11

LOS) taken during the performance verification phase and priority

science program. In this small sample (< 2% of the complete

GOT C+ survey) we detected 146 clouds in [CII] emission. These

data cover four broad categories of clouds as defined by their HI,

[CII], and CO signatures: a) diffuse atomic clouds with high

HI to [CII] intensity ratio and no detectable CO; b) diffuse molecular

clouds with relatively low HI to [CII] intensity ratio (due to

relatively strong [CII]) and no 12CO emission (

![]() mag); c) transition molecular clouds and PDRs detected in HI, [CII], and 12CO, but not 13CO; and, d) dense molecular clouds detected with HI, [CII], 12CO, 13CO, and sometimes C18O.

mag); c) transition molecular clouds and PDRs detected in HI, [CII], and 12CO, but not 13CO; and, d) dense molecular clouds detected with HI, [CII], 12CO, 13CO, and sometimes C18O.

In this

![]() we analyze 29 diffuse clouds (

we analyze 29 diffuse clouds (

![]() mag)

characterized by the presence of [CII] and HI emission, but having no

CO emission. We find that [CII] emission is generally stronger than

expected for diffuse atomic clouds (

mag)

characterized by the presence of [CII] and HI emission, but having no

CO emission. We find that [CII] emission is generally stronger than

expected for diffuse atomic clouds (

![]() K,

K,

![]() cm-3),

and in about one-third of the sources [CII] emission is much stronger

than anticipated. This [CII] emission indicates the presence of warm

``dark gas'' (H2 without CO) associated with HI. Velusamy et al. (2010) discuss the transition C

+-12CO clouds and their ``dark gas'' envelopes, and Pineda et al. (2010) discuss the dense molecular cloud PDRs.

cm-3),

and in about one-third of the sources [CII] emission is much stronger

than anticipated. This [CII] emission indicates the presence of warm

``dark gas'' (H2 without CO) associated with HI. Velusamy et al. (2010) discuss the transition C

+-12CO clouds and their ``dark gas'' envelopes, and Pineda et al. (2010) discuss the dense molecular cloud PDRs.

2 Observations

The 16 LOS observations of [CII] at 1.9 THz were made with Herschel/HIFI band 7b using Load Chop (HPOINT) with SkyRef offset by 2

![]() off the plane, for better cancelation of instrumental spectral

baselines. The data were reduced with HIPE version 3 and a

fringe-fitting tool to remove standing waves, and the h- and

v-polarizations combined where available. All [CII] data are corrected

for the antenna's main beam efficiency of 0.63. We used the wide band

spectrometer (WBS) with 0.22 km s-1 at 1.9 THz. The 16 LOS are: 1) b=0 at longitudes: 337.82

off the plane, for better cancelation of instrumental spectral

baselines. The data were reduced with HIPE version 3 and a

fringe-fitting tool to remove standing waves, and the h- and

v-polarizations combined where available. All [CII] data are corrected

for the antenna's main beam efficiency of 0.63. We used the wide band

spectrometer (WBS) with 0.22 km s-1 at 1.9 THz. The 16 LOS are: 1) b=0 at longitudes: 337.82

![]() ,

343.04

,

343.04

![]() ,

343.91

,

343.91

![]() ,

344.78

,

344.78

![]() ,

345.65

,

345.65

![]() ,

18.26

,

18.26

![]() ,

22.60

,

22.60

![]() ,

23.47

,

23.47

![]() ,

24.34

,

24.34

![]() ;

and, 2)

;

and, 2)

![]() at 24.34

at 24.34

![]() ,

,

![]() at 18.26

at 18.26

![]() ,

23.47

,

23.47

![]() ,

,

![]() at 22.60

at 22.60

![]() ,

24.34

,

24.34

![]() ,

and

,

and

![]() at 18.26

at 18.26

![]() ,

23.47

,

23.47

![]() .

Further details are in Velusamy et al. (2010). We also observed the

.

Further details are in Velusamy et al. (2010). We also observed the

![]() transitions of 12CO, 13CO, and C18O toward each LOS with the ATNF Mopra 22-m Telescope (details in Pineda et al. 2010), with an angular resolution of 33

transitions of 12CO, 13CO, and C18O toward each LOS with the ATNF Mopra 22-m Telescope (details in Pineda et al. 2010), with an angular resolution of 33

![]() .

We obtained HI data from public sources (McClure-Griffiths et al. 2005; Stil et al. 2006).

.

We obtained HI data from public sources (McClure-Griffiths et al. 2005; Stil et al. 2006).

A typical example of our data is shown in Fig. 1 for

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

where we plot the [CII] antenna temperature (corrected for main beam

efficiency) along with those of HI, and the CO isotopes (other examples

are shown in Pineda et al. 2010 and Velusamy et al. 2010).

This LOS passes through the edge of the bar in the inner Galaxy. The

[CII] features are clearly blends of many cloud components. It can be

seen in Fig. 1 that a wide variety of clouds are detected in [CII], for example: between

,

where we plot the [CII] antenna temperature (corrected for main beam

efficiency) along with those of HI, and the CO isotopes (other examples

are shown in Pineda et al. 2010 and Velusamy et al. 2010).

This LOS passes through the edge of the bar in the inner Galaxy. The

[CII] features are clearly blends of many cloud components. It can be

seen in Fig. 1 that a wide variety of clouds are detected in [CII], for example: between

![]() and 10 km s-1 there is strong [CII] emission along with CO and 13CO, whereas between -100 and -140 km s-1 four narrow [CII] features appear which have weak 12CO associated with them, while between -50 and -90 km s-1 there are five features with only [CII] and HI, and no detectable 12CO.

and 10 km s-1 there is strong [CII] emission along with CO and 13CO, whereas between -100 and -140 km s-1 four narrow [CII] features appear which have weak 12CO associated with them, while between -50 and -90 km s-1 there are five features with only [CII] and HI, and no detectable 12CO.

3 Results and analysis

We identified our clouds from Gaussian decompositions (see Fig. 1) of [CII] and 13CO (where available) and use these to characterize their velocities,

![]() ,

and linewidth

,

and linewidth ![]() v (see Velusamy et al. 2010, for details). With this approach we detected [CII] in 146 components at the 3-

v (see Velusamy et al. 2010, for details). With this approach we detected [CII] in 146 components at the 3-![]() level or better. We did not fit the HI spectral profiles, but

obtained the HI intensities in each cloud for comparison with other lines, by integrating within the velocity width (

level or better. We did not fit the HI spectral profiles, but

obtained the HI intensities in each cloud for comparison with other lines, by integrating within the velocity width (![]() v) centered at their

v) centered at their

![]() defined by the [CII] (and 13CO) lines. For each feature we derive the line parameters,

defined by the [CII] (and 13CO) lines. For each feature we derive the line parameters,

![]() (K),

(K), ![]() (km s-1),

(km s-1),

![]() (units of K km s-1), as well as those for HI and CO (where detected).

Here we focus on 29 out of 35 [CII] components that do not have any known molecular gas as traced by 12CO (the other six have marginal [CII] intensities, or other issues). The linewidths (FWHM) for these 29 diffuse C+ clouds, have a mean value of 3.4 km s-1, and range from 1.4 to 5.5 km s-1.

In Fig. 2

we plot the integrated intensity I(CII) versus I(HI) for all 29 diffuse cloud features. It can be seen that [CII] is not strongly correlated with I(HI). This result is not what one would expect if all the C+

is only in HI clouds. Furthermore, there is a large degree of scatter,

and, several sources have large [CII] emission at small N(HI), which we suggest is best explained by ``dark gas'' - H2 without CO.

(units of K km s-1), as well as those for HI and CO (where detected).

Here we focus on 29 out of 35 [CII] components that do not have any known molecular gas as traced by 12CO (the other six have marginal [CII] intensities, or other issues). The linewidths (FWHM) for these 29 diffuse C+ clouds, have a mean value of 3.4 km s-1, and range from 1.4 to 5.5 km s-1.

In Fig. 2

we plot the integrated intensity I(CII) versus I(HI) for all 29 diffuse cloud features. It can be seen that [CII] is not strongly correlated with I(HI). This result is not what one would expect if all the C+

is only in HI clouds. Furthermore, there is a large degree of scatter,

and, several sources have large [CII] emission at small N(HI), which we suggest is best explained by ``dark gas'' - H2 without CO.

The identification of ``dark gas'' in our [CII] data can be understood

by using simple models of the radiative transfer to relate the HI and

[CII] intensities, and then consider the effects of adding an

additional H2 layer containing C+. We calculate the column density of ionized carbon assuming the gas is only atomic, from the relation, N(C+) = X(C+) N(HI), where X(C+) is the fractional abundance of C+ in the gas with respect to HI. Observations in the local Interstellar Medium (ISM) lead to X(C+) in the range 1.4 to

![]() (Sofia et al. 1997), and here we adopt a value of X(C

(Sofia et al. 1997), and here we adopt a value of X(C

![]() .

The column density of HI can be estimated in the optically thin limit,

where the brightness temperature is less than the kinetic temperature,

as

.

The column density of HI can be estimated in the optically thin limit,

where the brightness temperature is less than the kinetic temperature,

as

![]() .

We can also directly calculate the N(C+) column density from I(CII) if we know the temperature and density of the gas. If the gas arises only from the HI cloud the N(C+) solutions should be consistent within a reasonable range of density and temperature. We derived the column density for N(C+)

in the optically thin limit (the effects of opacity are discussed

below) with no background radiation field (the CMB is negligible),

.

We can also directly calculate the N(C+) column density from I(CII) if we know the temperature and density of the gas. If the gas arises only from the HI cloud the N(C+) solutions should be consistent within a reasonable range of density and temperature. We derived the column density for N(C+)

in the optically thin limit (the effects of opacity are discussed

below) with no background radiation field (the CMB is negligible),

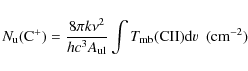

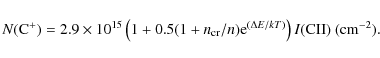

|

(1) |

where

|

(2) |

The critical density (for HI or H2) is defined as,

In Fig. 2

we plot the predicted I(CII) versus I(HI) as a function of temperature and density, assuming that N(C+) is given by, N(C+) = X(C+)N(HI). The solid lines show results for typical diffuse atomic cloud conditions, T = 100 to 300 K and n = 100 to 300 cm-3. The lowest curve is for

(T,n) = (100 K, 100 cm-3), a likely lower bound for these diffuse atomic hydrogen clouds; all of our observed I(CII) fall above this line. The result for somewhat denser diffuse clouds,

(T,n) = (100 K, 300 cm-3), is shown by the middle solid line in

Fig. 2;

about 25![]() of our sources fall along this line. We also plot results for a very warm HI cloud at

(T,n) = (300 K, 300 cm-3)

(upper solid line) to give an idea of what physical conditions might be

needed to explain a larger percentage of our [CII] clouds. About half

the observed [CII] clouds fall below this line. However, this solution

requires a rather hot diffuse atomic cloud, with a pressure,

of our sources fall along this line. We also plot results for a very warm HI cloud at

(T,n) = (300 K, 300 cm-3)

(upper solid line) to give an idea of what physical conditions might be

needed to explain a larger percentage of our [CII] clouds. About half

the observed [CII] clouds fall below this line. However, this solution

requires a rather hot diffuse atomic cloud, with a pressure,

![]() that is much greater than the generally accepted value. At best it

explains about half the [CII] sources as arising from atomic gas, but

it is probably an unrealistically high combination of (n,T);

and, the remaining sources require [CII] from additional cloud

components. In summary, [CII] emission from diffuse HI gas alone does

not explain that observed in much of our sample.

that is much greater than the generally accepted value. At best it

explains about half the [CII] sources as arising from atomic gas, but

it is probably an unrealistically high combination of (n,T);

and, the remaining sources require [CII] from additional cloud

components. In summary, [CII] emission from diffuse HI gas alone does

not explain that observed in much of our sample.

The analysis above assumes optically thin HI and [CII]

emission. We estimate the opacity correction for the [CII] lines by

starting with the optically thin derived N(C+) and using the RADEX code (van der Tak et al. 2007) to calculate ![]() (CII) for a range of diffuse cloud densities and temperatures. For I(CII

(CII) for a range of diffuse cloud densities and temperatures. For I(CII![]() K km s-1,

K km s-1,

![]() under most density and temperature conditions for a typical linewidth of 3 to 4 km s-1, and the escape probability for [CII] photons is

under most density and temperature conditions for a typical linewidth of 3 to 4 km s-1, and the escape probability for [CII] photons is ![]() 80%. Thus, any corrections to the column density are

80%. Thus, any corrections to the column density are ![]() 20%. The HI opacity is

20%. The HI opacity is ![]() (HI

(HI

![]() N(HI)

N(HI)

![]() ), or, using the optically thin estimate for N(HI) above,

), or, using the optically thin estimate for N(HI) above, ![]() (HI) =I(HI)

(HI) =I(HI)

![]() ), where Tx

is the excitation temperature. We do not know excitation temperature

for HI, but it is reasonable to set it to 100-150 K, which yields

), where Tx

is the excitation temperature. We do not know excitation temperature

for HI, but it is reasonable to set it to 100-150 K, which yields ![]() (HI

(HI![]() ,

for I(HI

,

for I(HI![]() K km s-1, and a maximum of 0.8 for the sources near I(HI) = 500 K km s-1. In summary, these corrections are small, and maintain approximately the same N(C+)/N(HI)

ratio as the optically thin case, which does not resolve the issue of

excess [CII] emission within the context of purely atomic diffuse

clouds.

K km s-1, and a maximum of 0.8 for the sources near I(HI) = 500 K km s-1. In summary, these corrections are small, and maintain approximately the same N(C+)/N(HI)

ratio as the optically thin case, which does not resolve the issue of

excess [CII] emission within the context of purely atomic diffuse

clouds.

Unless we adopt a very high density, n > 103 cm-3 and/or high temperatures (T > 300 K), some other gas contribution is necessary to explain the [CII] emission. The clouds with I(CII![]() K km s-1 and I(HII

K km s-1 and I(HII![]() K km s-1

cannot even be explained by invoking such high HI densities and

temperatures. Furthermore, we would be faced with explaining how such

dense clouds, not associated with HII regions, could have such high

temperatures. We suggest that [CII] in these stronger C+

emitting clouds, is tracing a significant component of warm molecular

hydrogen gas, or warm ``dark gas''. Early cloud-chemical models

predicted such an H2 gas layer with C+ and little or no CO (see Langer 1977,

and references therein), although the term ``dark gas'' was not invoked

until much later. Since then, ever more accurate and sophisticated

cloud models have been developed, but the basic structure of the HI to H2 and C+ to CO-CI profile remains the same (e.g. Lee et al. 1996; Wolfire et al. 2010; van Dishoeck & Black 1988; Tielens & Hollenbach 1985).

K km s-1

cannot even be explained by invoking such high HI densities and

temperatures. Furthermore, we would be faced with explaining how such

dense clouds, not associated with HII regions, could have such high

temperatures. We suggest that [CII] in these stronger C+

emitting clouds, is tracing a significant component of warm molecular

hydrogen gas, or warm ``dark gas''. Early cloud-chemical models

predicted such an H2 gas layer with C+ and little or no CO (see Langer 1977,

and references therein), although the term ``dark gas'' was not invoked

until much later. Since then, ever more accurate and sophisticated

cloud models have been developed, but the basic structure of the HI to H2 and C+ to CO-CI profile remains the same (e.g. Lee et al. 1996; Wolfire et al. 2010; van Dishoeck & Black 1988; Tielens & Hollenbach 1985).

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,angle=0]{15088fg2.eps}

\vspace*{-2mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/13/aa15088-10/Timg62.png)

|

Figure 2:

Observed [CII] intensities (filled circles) versus I(HI) (lower axis); the corresponding N(HI) is given on the upper axis for optically thin lines. Model calculations of I(CII) versus I(HI) as a function of (

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

To estimate the amount of ``dark gas'' needed to explain the relatively

strong [CII] in diffuse clouds, we extended the excitation model

of N(CII) versus I(CII) (Eq. (2)) to a two-layer cloud, containing HI and H2.

In the optically thin regime, which as shown above is a reasonable

assumption for the diffuse sources, the total [CII] intensity is the

sum of that in each layer, I(CII)

![]() (CII)

(CII)

![]() (CII)

(CII)

![]() .

We can solve for I(CI)

.

We can solve for I(CI)![]() as follows: use

as follows: use

![]() to solve for N(HI) from I(HI), then N(C+) = X(C+) N(HI); and, finally I(CII)

to solve for N(HI) from I(HI), then N(C+) = X(C+) N(HI); and, finally I(CII)

![]() can be determined from Eq. (2) assuming a temperature and density, (

can be determined from Eq. (2) assuming a temperature and density, (

![]() ,

n(HI)) in the HI layer. Since,

I(CII)

,

n(HI)) in the HI layer. Since,

I(CII)

![]() (CII)

(CII)

![]() (CII)

(CII)

![]() ,

we can now solve for N(C+)

,

we can now solve for N(C+)

![]() ,

using Eq. (2), as a function of temperature and density (

,

using Eq. (2), as a function of temperature and density (

![]() ,n(H2)). For illustrative purposes in

Fig. 2,

we have chosen to consider N(H2) a variable, and define the relative column densities of molecular and atomic gas through a parameter,

,n(H2)). For illustrative purposes in

Fig. 2,

we have chosen to consider N(H2) a variable, and define the relative column densities of molecular and atomic gas through a parameter,

![]() (H2)/N(HI).

(H2)/N(HI).

In Fig. 2

we plot I(CII) versus I(HI) for different values of ![]() (dashed lines) ranging from 0 to 6 (

(dashed lines) ranging from 0 to 6 (

![]() corresponds to a pure HI cloud), for a fixed temperature and density (T,n(HI)) = (100 K, 300 cm-3), and assume constant pressure and temperature, so n(H2) = n(HI). We assume that I(HI) yields the column density N(C+) in the HI region, and N(H2) is proportional to N(HI). A modest layer of H2 (N(H2) = 1 to

corresponds to a pure HI cloud), for a fixed temperature and density (T,n(HI)) = (100 K, 300 cm-3), and assume constant pressure and temperature, so n(H2) = n(HI). We assume that I(HI) yields the column density N(C+) in the HI region, and N(H2) is proportional to N(HI). A modest layer of H2 (N(H2) = 1 to

![]() (HI)) fits the distribution of many of the stronger [CII] clouds. However, a much thicker layer of H2 (

(HI)) fits the distribution of many of the stronger [CII] clouds. However, a much thicker layer of H2 (

![]() to 6) is required to explain the strongest [CII] emitting clouds in this sample.

to 6) is required to explain the strongest [CII] emitting clouds in this sample.

To characterize and compare the clouds and their dark gas content, we calculated the visual extinction ![]() and ratio N(H2)/N(HI) for each source, assuming a fixed

(T, n) = (100 K, 300 cm-3); these are plotted in Fig. 3 for each source.

We follow the procedure described above using N(HI

and ratio N(H2)/N(HI) for each source, assuming a fixed

(T, n) = (100 K, 300 cm-3); these are plotted in Fig. 3 for each source.

We follow the procedure described above using N(HI

![]() (HI) to derive N(C+)

(HI) to derive N(C+)![]() ,

then calculate the corresponding I(CII)

,

then calculate the corresponding I(CII)

![]() ;

subtract from I(CII)

;

subtract from I(CII)

![]() ;

finally, derive N(C+)

;

finally, derive N(C+)

![]() using Eq. (2), and N(H2) = N(C+)

using Eq. (2), and N(H2) = N(C+)

![]() /(2X(C+)). then

/(2X(C+)). then

![]() (HI) +2N(H

(HI) +2N(H

![]() .

The extinction ranges from 0.15 to 1.3 mag. and about 75% of the sources have N(H

.

The extinction ranges from 0.15 to 1.3 mag. and about 75% of the sources have N(H

![]() (HI), and about 30% have N(H

(HI), and about 30% have N(H![]() (HI). If the density and/or temperature in the H2 layer is lower than assumed here, N(H2) will be higher; and for higher (n,T)

it will be lower. Here we assumed typical diffuse cloud conditions.

However, [CII] preferentially identifies warm gas, so some sources may

be hotter and denser, perhaps in proximity to UV sources or sampling

shocked gas, and have smaller N(H2) than we

calculate. Although it may the the case in a few individual clouds,

statistically our sample of diffuse clouds observed in [CII] emission

provides evidence for warm molecular ``dark gas'' in diffuse regions.

(HI). If the density and/or temperature in the H2 layer is lower than assumed here, N(H2) will be higher; and for higher (n,T)

it will be lower. Here we assumed typical diffuse cloud conditions.

However, [CII] preferentially identifies warm gas, so some sources may

be hotter and denser, perhaps in proximity to UV sources or sampling

shocked gas, and have smaller N(H2) than we

calculate. Although it may the the case in a few individual clouds,

statistically our sample of diffuse clouds observed in [CII] emission

provides evidence for warm molecular ``dark gas'' in diffuse regions.

4 Discussion

The suggestion of the presence of ``dark gas'' in the interstellar medium is not new, Bloemen et al. (1986) used COS-B, Strong & Mattox (1996) EGRET, and Abdo et al. (2010) FERMI-LAT ![]() -ray data to show that the Galaxy has more gas mass than indicated by HI and CO surveys alone. Joncas et al. (1992) compared HI and 100

-ray data to show that the Galaxy has more gas mass than indicated by HI and CO surveys alone. Joncas et al. (1992) compared HI and 100 ![]() m

dust emission in infrared cirrus and from the excess infrared emission

suggested there might be molecular hydrogen or cold atomic gas (T < 30 K) - see also Reach et al. (1994), who include CO. Grenier et al. (2005), who applied the term ``dark gas'' to this component, extended this approach to include

m

dust emission in infrared cirrus and from the excess infrared emission

suggested there might be molecular hydrogen or cold atomic gas (T < 30 K) - see also Reach et al. (1994), who include CO. Grenier et al. (2005), who applied the term ``dark gas'' to this component, extended this approach to include ![]() -ray observations and concluded that there were ``dark gas'' layers (H2

without CO) surrounding all the nearby CO clouds. In addition, models

of diffuse clouds and cloud envelopes (PDRs) predict significant

amounts of H2 gas with no CO, but containing C+ and some neutral carbon, Co.

-ray observations and concluded that there were ``dark gas'' layers (H2

without CO) surrounding all the nearby CO clouds. In addition, models

of diffuse clouds and cloud envelopes (PDRs) predict significant

amounts of H2 gas with no CO, but containing C+ and some neutral carbon, Co.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,angle=0]{15088fg3.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/13/aa15088-10/Timg81.png)

|

Figure 3:

Distribution of |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Here we detected the warm ``dark gas'' with [CII], and showed it is a tracer of this important ISM component. Velusamy et al. (2010) use the GOT C+ data base to analyze [CII] associated with 12CO clouds and find evidence for warm H2 layers sandwiched between the HI and CO regions. Thus, warm H2 gas is an important component in interstellar clouds, in agreement with cloud-chemical models. We estimate the [CII] emission from all diffuse components (this paper and transition clouds Velusamy et al. 2010) and find their sum to be about equal to that of the dense PDRs (Pineda et al. 2010) along these 16 LOS.

5 Conclusions

We have detected, for the first time, warm ``dark gas'' using the C+ 2P 3/2-2P1/2 fine structure emission line at 1.9 THz (158This work was performed by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, under contract with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. We thank the staffs of the ESA and NASA Herschel Science Centers for their help. The Mopra Telescope is managed by the Australia Telescope, and funded by the Commonwealth of Australia for operation as a National Facility by the CSIRO. We thank the referee and editor for comments.

References

- Abdo, A. A., Ackermann, M., Ajello, M., & et al.. 2010, ApJ, 710, 133 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Barinovs, G., van Hemert, M. C., Krems, R., & Dalgarno, A. 2005, ApJ, 620, 537 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, C. L., Fixsen, D. J., Hinshaw, G., et al. 1994, ApJ, 434, 587 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bloemen, J. B. G. M., Strong, A. W., Mayer-Hasselwander, H. A., et al. 1986, A&A, 154, 25 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Boreiko, R. T., & Betz, A. L. 1991, ApJ, 380, L27 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Dame, T. M., Hartmann, D., & Thaddeus, P. 2001, ApJ, 547, 792 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- de Graauw, Th., Helmich, F. P., Phillips, T. G., et al. 2010, A&A, 518, L6 [Google Scholar]

- Flower, D. R. 1988, Journal of Physics B Atomic Molecular Physics, 21, L451 [Google Scholar]

- Flower, D. R. 1990, Molecular collisions in the interstellar medium (Cambridge: University Press) [Google Scholar]

- Grenier, I. A., Casandjian, J.-M., & Terrier, R. 2005, Science, 307, 1292 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joncas, G., Boulanger, F., & Dewdney, P. E. 1992, ApJ, 397, 165 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Langer, W. D. 1977, ApJ, 212, L39 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Langer, W. D., Velusamy, T., Pineda, J. L., et al. 2010, ESLAB2010, on line [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H., Herbst, E., Pineau des Forets, G., Roueff, E., & Le Bourlot, J. 1996, A&A, 311, 690 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- McClure-Griffiths, N., Dickey, J., Gaensler, B., et al. 2005, ApJS, 158, 178 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa, T., Yui, Y. Y., Doi, Y., et al. 1998, ApJS, 115, 259 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pilbratt, G. L., Riedinger, J. R., Passvogel, T., et al. 2010, A&A, 518, L1 [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Pineda, J. L., Velusamy, T., Langer, W. D., et al. 2010, A&A, 521, L19 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Reach, W. T., Koo, B., & Heiles, C. 1994, ApJ, 429, 672 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sofia, U. J., Cardelli, J. A., Guerin, K. P., & Meyer, D. M. 1997, ApJ, 482, L105 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Stil, J. M., Taylor, A. R., Dickey, J. M., et al. 2006, AJ, 132, 1158 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Strong, A. W., & Mattox, J. R. 1996, A&A, 308, L21 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Tielens, A. G. G. M., & Hollenbach, D. 1985, ApJ, 291, 722 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- van der Tak, F. F. S., Black, J. H., Schöier, F. L., Jansen, D. J., & van Dishoeck, E. F. 2007, A&A, 468, 627 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- van Dishoeck, E. F., & Black, J. H. 1988, ApJ, 334, 771 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Velusamy, T., Langer, W. D., Pineda, J. L., et al. 2010, A&A, 521, L18 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfire, M. G., Hollenbach, D., & McKee, C. F. 2010, ApJ, 716, 1191 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Footnotes

- ... clouds

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- Herschel is an ESA space observatory with science instruments provided by European-led Principal Investigator consortia and with important participation from NASA.

All Figures

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=16cm,angle=0]{15088fg1.eps}

\vspace*{-2mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/13/aa15088-10/Timg16.png)

|

Figure 1:

[CII] spectra obtained with Herschel/HIFI for the GOT C+ program at

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,angle=0]{15088fg2.eps}

\vspace*{-2mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/13/aa15088-10/Timg62.png)

|

Figure 2:

Observed [CII] intensities (filled circles) versus I(HI) (lower axis); the corresponding N(HI) is given on the upper axis for optically thin lines. Model calculations of I(CII) versus I(HI) as a function of (

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,angle=0]{15088fg3.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/13/aa15088-10/Timg81.png)

|

Figure 3:

Distribution of |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

Copyright ESO 2010

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.