| Issue |

A&A

Volume 521, October 2010

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A63 | |

| Number of page(s) | 31 | |

| Section | Extragalactic astronomy | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201014295 | |

| Published online | 21 October 2010 | |

Massive star formation in Wolf-Rayet galaxies

V. Star-formation rates, masses and the importance of galaxy interactions

Á. R. López-Sánchez1,2

1 -

CSIRO Astronomy and Space Science / Australia Telescope National Facility, PO

Box 76, Epping, NSW 1710, Australia

2 - Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias, C/ Vía Láctea S/N, 38200 La

Laguna, Tenerife, Spain

Received 20 February 2010 / Accepted 3 May 2010

Abstract

Aims. We performed a comprehensive analysis of a

sample of 20 starburst galaxies that show a substantial population of

very young massive stars, most of them classified as Wolf-Rayet

galaxies.

Methods. In this paper, the last in the series, we

analyze the global properties of our galaxy sample using

multiwavelength data extracted from our own observations (H![]() fluxes, B and H-band

magnitudes) and from the literature, which include X-ray, FUV, FIR, and

radio (both H I spectral

line and 1.4 GHz radio-continuum) measurements.

fluxes, B and H-band

magnitudes) and from the literature, which include X-ray, FUV, FIR, and

radio (both H I spectral

line and 1.4 GHz radio-continuum) measurements.

Results. The agreement between our H![]() -based

star-formation rates (S FR) and those

provided by indicators at other wavelengths is remarkable, but we

consider that the new H

-based

star-formation rates (S FR) and those

provided by indicators at other wavelengths is remarkable, but we

consider that the new H![]() -based

calibration provided by Calzetti et al. (2007, ApJ, 666, 870)

should be preferred to older calibrations. The FUV-based S FR

provides a powerful tool for analyzing the star-formation activity on

both global and local scales independently to the H

-based

calibration provided by Calzetti et al. (2007, ApJ, 666, 870)

should be preferred to older calibrations. The FUV-based S FR

provides a powerful tool for analyzing the star-formation activity on

both global and local scales independently to the H![]() emission. We provide empirical relationships between the ionized gas

mass, neutral gas mass, dust mass, stellar mass, and dynamical mass

with the B-luminosity. Although all mass

estimations increase with increasing luminosity, we find important

deviations to the general trend in some objects, which seem to be the

consequence of their particular evolutionary histories. The analysis of

the mass-to-light ratios give similar results. We investigate the

mass-metallicity relations and conclude that both the nature and the

star-formation history are needed to understand the relationships

between both properties. The majority of the galaxies follow a

Schmidt-Kennicutt scaling law of star-formation that agrees with that

reported in individual star-forming regions within M 51 but

not with that found in normal spiral galaxies. Dwarf galaxies seem to

be forming stars more efficiently than the outskirts of spiral

galaxies. We find a relation between the reddening coefficient and the

warm dust mass indicating that the extinction is mainly internal to the

galaxies. The comparison with the closed-box model also indicates that

the environment has strongly affected their evolution.

emission. We provide empirical relationships between the ionized gas

mass, neutral gas mass, dust mass, stellar mass, and dynamical mass

with the B-luminosity. Although all mass

estimations increase with increasing luminosity, we find important

deviations to the general trend in some objects, which seem to be the

consequence of their particular evolutionary histories. The analysis of

the mass-to-light ratios give similar results. We investigate the

mass-metallicity relations and conclude that both the nature and the

star-formation history are needed to understand the relationships

between both properties. The majority of the galaxies follow a

Schmidt-Kennicutt scaling law of star-formation that agrees with that

reported in individual star-forming regions within M 51 but

not with that found in normal spiral galaxies. Dwarf galaxies seem to

be forming stars more efficiently than the outskirts of spiral

galaxies. We find a relation between the reddening coefficient and the

warm dust mass indicating that the extinction is mainly internal to the

galaxies. The comparison with the closed-box model also indicates that

the environment has strongly affected their evolution.

Conclusions. Considering all multiwavelength data,

we found that 17 up to 20 galaxies are clearly interacting or merging

with low-luminosity dwarf objects or H I clouds.

The remaining three galaxies (Mkn 5, SBS 1054+364,

and SBS 1415+437) show considerable divergences of some

properties when comparing with similar objects. Many of the

interacting/merging features are only detected when deep optical

spectroscopy and a detailed multiwavelength analysis, including

H I observations, are

obtained. We conclude that interactions do play a fundamental role in

the triggering mechanism of the strong star-formation activity observed

in dwarf starburst galaxies.

Key words: galaxies: starburst - galaxies: interactions - galaxies: dwarf - galaxies: abundances - stars: Wolf-Rayet - galaxies: kinematics and dynamics

1 Introduction

Since the discovery of the starburst galaxies (Sargent & Searle

1970),

many studies have tried to understand the processes that trigger the

strong star-formation activity in these objects. The hypothesis that

the gravitational interaction (not necessarily merging) of galaxies

enhances star-formation or leads to starburst activity was made soon

after the recognition of the starburst phenomenon. Larson &

Tinsley (1978)

did a study of normal and peculiar (Arp 1966) samples of

galaxies and

demonstrated that recent (![]() 108 yr)

star-formation is more likely to occur in interacting than in

noninteracting galaxies.

Since then, numerous studies of individual galaxies have revealed the

fossil remnants of interaction/merger activity, increasing the evidence

that interactions and mergers trigger star-formation phenomena in

spiral galaxies (Koribalski 1996;

Kennicutt 1998;

Nikolic et al. 2004).

Infrared observations confirmed the very intense starbursts in major

disk-disk mergers (e.g., Joseph & Wright 1985; Solomon

& Sage 1988;

Sanders & Mirabel 1996;

Genzel et al. 1998;

Arribas et al. 2004).

Actually, almost 100% of galaxies with far-infrared (FIR) luminosities

of about 1012

108 yr)

star-formation is more likely to occur in interacting than in

noninteracting galaxies.

Since then, numerous studies of individual galaxies have revealed the

fossil remnants of interaction/merger activity, increasing the evidence

that interactions and mergers trigger star-formation phenomena in

spiral galaxies (Koribalski 1996;

Kennicutt 1998;

Nikolic et al. 2004).

Infrared observations confirmed the very intense starbursts in major

disk-disk mergers (e.g., Joseph & Wright 1985; Solomon

& Sage 1988;

Sanders & Mirabel 1996;

Genzel et al. 1998;

Arribas et al. 2004).

Actually, almost 100% of galaxies with far-infrared (FIR) luminosities

of about 1012 ![]() are in interacting/merging systems (Sanders 1997).

Furthermore, analysis of large-galaxy surveys (e.g., CfA2: Barton

et al. 2000;

2dF: Lambas et al. 2003;

SDSS: Nikolic et al. 2004)

has provided new evidence of interaction-induced starburst activity.

are in interacting/merging systems (Sanders 1997).

Furthermore, analysis of large-galaxy surveys (e.g., CfA2: Barton

et al. 2000;

2dF: Lambas et al. 2003;

SDSS: Nikolic et al. 2004)

has provided new evidence of interaction-induced starburst activity.

According to hierarchical clustering models of galaxy formation, larger galactic structures build up and grow through the accretion of dwarf galaxies (White & Frenk 1991; Kauffman & White 1993; Springer et al. 2005). Observations of local and distant luminous blue galaxies (LBG) and Lyman break galaxies seem to confirm that galaxy interactions are more common at high redshifts (e.g., Guzman et al. 1997; Hopkins et al. 2002; Erb et al. 2003; Werk et al 2004; Colina et al. 2005; Overzier et al. 2009; Cardamone et al. 2009), but many details are still unclear (i.e., Basu-Zych et al. 2009). Indeed, detailed studies of local interacting/merging galaxies provide vital clues to galaxy formation and evolution, as they constrain the properties of the hierarchical formation models.

Recent observations also suggest that interactions and mergers

between dwarf galaxies also trigger the star-formation activity

and play a fundamental role in the evolution of dwarf galaxies (i.e.,

Méndez & Esteban 2000;

Östlin et al. 2001,

2004;

Bergvall & Östlin 2002;

Johnson et al. 2004;

Bravo-Alfaro et al. 2004,

2006;

Cumming et al. 2008;

García-Lorenzo et al. 2008;

López-Sánchez & Esteban 2008,

2009; James

et al. 2010).

Many of these studies have been done on blue compact dwarf galaxies

(BCDGs), which are low-luminosity, low-metallicity (![]() 10% solar)

galaxies showing compact and irregular morphologies and undergoing an

intense and short-lived episode of star-formation (i.e., Izotov

& Thuan 1999;

Cairós et al. 2001a,b;

Papaderos et al. 2006),

on top of an old underlying population with ages of several Gyrs

(Noeske et al. 2003,

2005;

Amorín et al. 2007,

2009). Recent

numerical simulations (Bekki 2008)

satisfactorily explain the physical properties of BCDGs as a

consequence of the merging of two dwarf galaxies with a higher fraction

of gas and extended gas disks.

10% solar)

galaxies showing compact and irregular morphologies and undergoing an

intense and short-lived episode of star-formation (i.e., Izotov

& Thuan 1999;

Cairós et al. 2001a,b;

Papaderos et al. 2006),

on top of an old underlying population with ages of several Gyrs

(Noeske et al. 2003,

2005;

Amorín et al. 2007,

2009). Recent

numerical simulations (Bekki 2008)

satisfactorily explain the physical properties of BCDGs as a

consequence of the merging of two dwarf galaxies with a higher fraction

of gas and extended gas disks.

Actually, much of our knowledge of interacting galaxies has

been provided by H I observations.

Neutral hydrogen gas is the best tracer of galaxy-galaxy interactions

because the

H I distribution is

usually several times larger than the optical extent, hence more easily

disrupted by external forces (tidal interactions, gas infall, ram

pressure stripping) than the stellar disk (Broeils & van

Woerden 1994;

Salpeter & Hoffman 1996).

The distribution and kinematics of atomic gas within galaxies is

usually more or less regular, but in many cases they revealed complex

entities between galaxies such as tails, ripples, bridges, arcs, or

independent H I clumps

that, in many cases, show little disturbance in their corresponding

optical images (e.g., Schneider et al. 1989; Yun

et al. 1994;

Hibbard & van Gorkom 1996;

Verdes-Montenegro et al. 2001, 2002, 2005; Putman

et al. 2003;

Koribalski et al. 2003,

2004, 2005;

Temporin et al. 2003,

2005;

Emonts et al. 2006;

Ekta et al. 2008;

Koribalski & López-Sánchez 2009;

English et al. 2010;

see also The H I Rogues Gallery,

Hibbard et al. 2001). Several interferometric H I surveys,

such as The H I Nearby

Galaxy Survey (THINGS, Walter et al. 2008); the Local

Volume H I Survey

(LVHIS, Koribalski 2008) or the Faint Irregular Galaxies

GMRT Survey (FIGGS, Begum et al. 2008), are

providing accurate H I and

dynamical masses in hundreds of nearby galaxies, many of them dwarf

objects, as they account for ![]() 85% of the known galaxies in the Local Volume

(Karachentsev et al. 2004).

85% of the known galaxies in the Local Volume

(Karachentsev et al. 2004).

To understand interaction processes in dwarf galaxies we first have to know how stars and gas interact in low-mass environments. Indeed, feedback from massive stars is the dominant process that affects the interstellar medium (ISM) of these galaxies. Violent star-formation phenomena may disrupt the galaxy's gas and even expel it to the intergalactic medium, as some theoretical models predict (Mac Low & Ferrara 1999). But alternative models (e.g., Silich & Tenorio-Tagle 1998) and the available observations (Bomans 2005) suggest that dwarf galaxies keep their processed material. Furthermore, the links between the observational characteristics (fluxes, colors, morphologies, or sizes) and the underlying physical properties of the galaxies (stellar, dust, gas, baryonic, and dark matter content, chemical abundances, star-formation rate, and star-formation history) are still not well known.

For example, there are still many caveats in the understanding

of the interplay between the star-formation rate (S FR)

and the properties of the ISM. A very important step was taken with the

Schmidth-Kennicutt power-law relation (Schmidt 1959, 1963; Kennicutt

1998)

that correlates the average S FR per unit

area and the mean surface density of the cold gas (atomic plus

molecular). But tracers of star-formation, including optical colors and

H![]() flux (e.g., Larson & Tinsley 1978; Kennicutt 1998;

Calzetti et al. 2007),

FIR flux (Kennicutt 1998;

Heckman 1999), radio-continuum flux (Condon 1992), and

far-ultraviolet (FUV) flux (Kennicutt 1998; Salim

et al. 2007),

often yield to very different values of the S FR.

Although the density of atomic gas is known in some cases, not many

direct measurements of the molecular gas are available, and are

especially rare in dwarf galaxies (i.e., Taylor et al. 1998; Barone

et al. 2000; Braine et al. 2000, 2001, 2004).

flux (e.g., Larson & Tinsley 1978; Kennicutt 1998;

Calzetti et al. 2007),

FIR flux (Kennicutt 1998;

Heckman 1999), radio-continuum flux (Condon 1992), and

far-ultraviolet (FUV) flux (Kennicutt 1998; Salim

et al. 2007),

often yield to very different values of the S FR.

Although the density of atomic gas is known in some cases, not many

direct measurements of the molecular gas are available, and are

especially rare in dwarf galaxies (i.e., Taylor et al. 1998; Barone

et al. 2000; Braine et al. 2000, 2001, 2004).

On the other hand, the physics underlying the relationship

between stellar mass (or luminosity) and metallicity is still far from

clear, despite the important observational (e.g., Tremonti

et al. 2004;

van Zee & Haynes 2006;

Kewley & Ellison 2008)

and theoretical (e.g., De Lucia et al. 2004; Tissera

et al. 2005;

De Rossi et al. 2006; Davé

& Oppenheimer 2007)

efforts that aimed to explain it. Indeed, one of the main problems is

to derive the real metallicity of the ionized gas, because empirical

calibrations based on direct estimates of the electron temperature (![]() )

of the ionized gas and theoretical methods based on photoionization

models provide very different oxygen abundances (e.g., Yin

et al. 2007;

Kewley & Ellison 2008;

Esteban et al. 2009;

López-Sánchez & Esteban 2010). Finally, the present

understanding of correlations between the H I content,

stellar populations, and star-formation in dwarf starburst galaxies is

still at a preliminary stage because of the lack of detailed optical/NIR

images and spectra and/or interferometric H I maps

of these systems.

)

of the ionized gas and theoretical methods based on photoionization

models provide very different oxygen abundances (e.g., Yin

et al. 2007;

Kewley & Ellison 2008;

Esteban et al. 2009;

López-Sánchez & Esteban 2010). Finally, the present

understanding of correlations between the H I content,

stellar populations, and star-formation in dwarf starburst galaxies is

still at a preliminary stage because of the lack of detailed optical/NIR

images and spectra and/or interferometric H I maps

of these systems.

In our series of papers, we have presented a detailed photometric and spectroscopic study of a sample of strong star-forming galaxies, many of them previously classified as dwarf galaxies. The majority of these objects are Wolf-Rayet (WR) galaxies, which are a very inhomogeneous class of star-forming objects that share an ongoing or very recent star-formation event that has produced stars massive enough to evolve to the WR stage (Schaerer et al. 1999). The WR features in the spectra of a galaxy constrains the properties of the star-formation processes. Because the first WR stars typically appear around 2-3 Myr after the starburst is initiated and disappear within some 5 Myr (Meynet & Maeder 2005), their detection informs about both the youth and strength of the burst, offering the opportunity to study an approximately coeval sample of very young starbursts (Schaerer & Vacca 1998).

Our main aim is to study the formation of massive stars in

starburst galaxies and the role that interaction with or between dwarf

galaxies and/or low surface brightness objects plays in its triggering

mechanism. In Paper I (López-Sánchez & Esteban 2008) we

introduced the motivation of this work, compiled the list of the

analyzed WR galaxies (Table 1 of Paper I),

and presented the results of optical/NIR

broad-band and H![]() photometry. In Paper II (López-Sánchez & Esteban 2009) we presented

the results of our analysis of intermediate-resolution long-slit

spectroscopy of 16 objects in our sample of WR galaxies - the

results for the other 4 objects were published separately. In

Paper II, we also specified the oxygen abundances of the

ionized gas (computed following the direct

photometry. In Paper II (López-Sánchez & Esteban 2009) we presented

the results of our analysis of intermediate-resolution long-slit

spectroscopy of 16 objects in our sample of WR galaxies - the

results for the other 4 objects were published separately. In

Paper II, we also specified the oxygen abundances of the

ionized gas (computed following the direct ![]() method in the majority of the cases) and analyzed the kinematics of the

ionized gas. In Paper III (López-Sánchez & Esteban 2010a), we

studied the O and WR stellar populations within these

galaxies, and compared them with theoretical evolutionary synthesis

models. In Paper IV (López-Sánchez & Esteban 2010b), we

analyzed the optical/NIR properties of the

galaxies overall, concluding that such detailed analyses are

fundamental in understanding the star-formation histories of the

galaxies. For this paper, the last in the series, we performed a

comprehensive multiwavelength analysis that considers all the optical

and NIR data but also includes radio, FIR, FUV,

and X-ray data available in the literature.

method in the majority of the cases) and analyzed the kinematics of the

ionized gas. In Paper III (López-Sánchez & Esteban 2010a), we

studied the O and WR stellar populations within these

galaxies, and compared them with theoretical evolutionary synthesis

models. In Paper IV (López-Sánchez & Esteban 2010b), we

analyzed the optical/NIR properties of the

galaxies overall, concluding that such detailed analyses are

fundamental in understanding the star-formation histories of the

galaxies. For this paper, the last in the series, we performed a

comprehensive multiwavelength analysis that considers all the optical

and NIR data but also includes radio, FIR, FUV,

and X-ray data available in the literature.

The selection criteria of the galaxy sample were the

following. We used the most recent catalog of WR galaxies

(Schaerer et al. 1999),

which contains a very inhomogeneous group of starbursting objects, to

make a list of dwarf objects that could be observed from the Northern

Hemisphere. As a result, we considered neither spirals galaxies nor

giant H II regions within them,

and considered only dwarf objects, such as apparently isolated BCDGs

and dwarf irregular galaxies that had peculiar morphologies in

previous, shallower imaging. We also chose two galaxies belonging to

the Schaerer et al. (1999)

catalog that were classified as suspected

WR galaxies (Mkn 1087 and Tol 9), to confirm the presence of

massive stars within them (see Papers II and III).

The galaxy IRAS 08339+6517 was also included because previous

multiwavelength results suggested that the WR stars could

still be present in its youngest star-forming bursts (see López-Sánchez

et al. 2006).

With this, we got a list of ![]() 40 systems

to observe and analyze using the telescopes available at Roque de los

Muchachos (La Palma, Spain) and Calar Alto (Almería, Spain)

observatories. We added the southern galaxy NGC 5253, for

which we obtained deep echelle spectrophotometry using 8.2 m

VLT, because of the very intriguing properties it possesses (see

López-Sánchez et al. 2007,

2010). The final sample of 20 galaxies was created by considering those

galaxies for which we obtained optical/NIR

broad-band and H

40 systems

to observe and analyze using the telescopes available at Roque de los

Muchachos (La Palma, Spain) and Calar Alto (Almería, Spain)

observatories. We added the southern galaxy NGC 5253, for

which we obtained deep echelle spectrophotometry using 8.2 m

VLT, because of the very intriguing properties it possesses (see

López-Sánchez et al. 2007,

2010). The final sample of 20 galaxies was created by considering those

galaxies for which we obtained optical/NIR

broad-band and H![]() images, plus the deep optical spectroscopy during our observation runs.

We already have all these data for other

images, plus the deep optical spectroscopy during our observation runs.

We already have all these data for other ![]() 15 galaxies, the analysis of these

systems will be presented in the future elsewhere, but its preliminary

results seem to agree with the main results reported in this paper. Our

galaxy sample is therefore not complete, but we consider that it

represents dwarf galaxies experiencing a very strong star-formation

burst quite well. Indeed, this was the main bias introduced when

choosing the galaxy sample, such as we focused only in galaxies on

which WR stars are detected. It would be very interesting to

extend this analysis to similar star-forming galaxies that do not show

WR features, such as the sample of BCDGs analyzed by

Gil de Paz et al. (2003).

15 galaxies, the analysis of these

systems will be presented in the future elsewhere, but its preliminary

results seem to agree with the main results reported in this paper. Our

galaxy sample is therefore not complete, but we consider that it

represents dwarf galaxies experiencing a very strong star-formation

burst quite well. Indeed, this was the main bias introduced when

choosing the galaxy sample, such as we focused only in galaxies on

which WR stars are detected. It would be very interesting to

extend this analysis to similar star-forming galaxies that do not show

WR features, such as the sample of BCDGs analyzed by

Gil de Paz et al. (2003).

The structure of this paper is the following. In Sect. 2 we describe the details of the radio, FIR, FUV, and X-ray data extracted from the literature and provide some very useful relations. Section 3 analyzes the star-formation activity in our sample galaxies when considering all multiwavelength calibrators to the S FR. We check that our sample galaxies follow the radio/FIR correlation in Sect. 4. Next, Sect. 5 compiles, analyses and compares all mass estimations derived in this work. Several mass-metallicity relations are investigated in Sect. 6. We study whether our galaxies satisfy the Schmidt-Kennicutt relation in Sect. 7. Section 8 analyzes and compares several mass-to-light ratios. The dust properties within our starburst galaxies are investigated in Sect. 9. We compare the predictions of the closed-box model with our observational data in Sect. 10. Finally, Sect 11 compiles a quantitative analysis of the interaction features considering all available multiwavelength data. The conclusions reached in our analysis are compiled in Sect. 12. The Appendix describes the main results found in each of the analyzed WR galaxies.

Table 1: Radio data compiled from the literature for our WR galaxy sample.

2 Multiwavelength data completeness

We made an exhaustive literature search to complete the optical/NIR observations of our WR galaxy sample with data from other wavelengths (radio, far-infrared, far-ultraviolet, and X-ray). Here we describe all these data and the useful properties we have derived from them.

2.1 Radio data

2.1.1 H I data at 21 cm

Observations in the hyperfine transition of the neutral hydrogen,

H I, with a rest frequency of

1420.405 MHz, have been key in understanding the distribution

and kinematics of the atomic gas within galaxies, including the Milky

Way. Neutral gas observations are very important because they are used

to determine both the neutral gas mass (H I gas)

and the dynamical mass (

![]() )

of the systems. Single-dish H I surveys

(e.g. Mathewson et al. 1992, the H I

Parkes Sky Survey, HIPASS, Barnes et al. 2001; Koribalski

et al. 2004;

Meyer et al. 2004;

and the Arecibo Legacy Fast ALFA survey, ALFALFA,

Giovanelli et al. 2005),

give spectra with detected H I emission

of thousands of galaxies. However, the best tool for analyzing the

neutral gas content in galaxies is via radio

interferometer observations (e.g., THINGS; LVHIS; FIGGS; The

H I Rogues Gallery). Knowing the

amount of available neutral gas, the timescale of the starbursts (i.e.,

the time when the H I cloud will be

exhausted if the star-formation activity continues at the current S FR)

can be calculated.

)

of the systems. Single-dish H I surveys

(e.g. Mathewson et al. 1992, the H I

Parkes Sky Survey, HIPASS, Barnes et al. 2001; Koribalski

et al. 2004;

Meyer et al. 2004;

and the Arecibo Legacy Fast ALFA survey, ALFALFA,

Giovanelli et al. 2005),

give spectra with detected H I emission

of thousands of galaxies. However, the best tool for analyzing the

neutral gas content in galaxies is via radio

interferometer observations (e.g., THINGS; LVHIS; FIGGS; The

H I Rogues Gallery). Knowing the

amount of available neutral gas, the timescale of the starbursts (i.e.,

the time when the H I cloud will be

exhausted if the star-formation activity continues at the current S FR)

can be calculated.

Table 1

compiles all H I 21 cm

data found for our galaxy sample. The majority of the H I data

is provided by single-dish H I

observations, but interferometric H I maps

are available for a few cases (HGC 31 and

IRAS 08339+6517). Table 1 lists the

H I flux density,

![]() (in

units of Jy km s-1), and

the H I equivalent width,

(in

units of Jy km s-1), and

the H I equivalent width,

![]() (in

km s-1). For 3 galaxies

(POX 4, Tol 9 and NGC 5253) we are using the

data provided by our new interferometric maps obtained using the Australia

Telescope Compact Array. For these objects, we compiled the

integrated H I flux and

width; their detailed analysis will soon be presented elsewhere

(López-Sánchez et al. 2010a,b).

SBS 0926+606 was recently observed by Huchtmeier

et al. (2007),

who gave a combined H I flux

for both A and B galaxies, but only interferometric studies can

disentangle the amount of neutral gas in each galaxy.

Tol 1457-262 and Arp 252 were observed in H I by

Casasola et al. (2004)

using a single-dish antenna, but they were not detected.

Arp 252 was not detected in H I in

HIPASS either (Koribalski 2006, priv. comm.).

The total H I mass is

computed by applying

(in

km s-1). For 3 galaxies

(POX 4, Tol 9 and NGC 5253) we are using the

data provided by our new interferometric maps obtained using the Australia

Telescope Compact Array. For these objects, we compiled the

integrated H I flux and

width; their detailed analysis will soon be presented elsewhere

(López-Sánchez et al. 2010a,b).

SBS 0926+606 was recently observed by Huchtmeier

et al. (2007),

who gave a combined H I flux

for both A and B galaxies, but only interferometric studies can

disentangle the amount of neutral gas in each galaxy.

Tol 1457-262 and Arp 252 were observed in H I by

Casasola et al. (2004)

using a single-dish antenna, but they were not detected.

Arp 252 was not detected in H I in

HIPASS either (Koribalski 2006, priv. comm.).

The total H I mass is

computed by applying

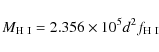

|

(1) |

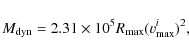

(Roberts 1975; Roberts & Haynes 1994) where the distance to the galaxy, d, is expressed in Mpc, and the result for the neutral gas mass is given in solar units. The dynamical mass of the system,

|

(2) |

which is the result in solar masses when

2.1.2 Radio-continuum data

For an individual star-forming galaxy, the S FR

is directly proportional to its radio luminosity (i.e., Condon 1992). Hence,

the radio continuum flux is widely used as a dust-free indicator of the

star-formation rate. Nearly all of the radio-continuum luminosity from

galaxies without a significant active galactic nucleus (AGN) can be

traced to recently formed massive (![]()

![]() )

stars (Condon et al. 1992).

The 10% of the continuum emission at 1.4 GHz comes from

free-free emission from extremely massive main-sequence stars (thermal

emission) and almost 90% is synchrotron radiation from relativistic

electrons accelerated in the remnants of core-collapse supernovae

(nonthermal emission). Because the stars that contribute significantly

to the radio emission have lifetimes

)

stars (Condon et al. 1992).

The 10% of the continuum emission at 1.4 GHz comes from

free-free emission from extremely massive main-sequence stars (thermal

emission) and almost 90% is synchrotron radiation from relativistic

electrons accelerated in the remnants of core-collapse supernovae

(nonthermal emission). Because the stars that contribute significantly

to the radio emission have lifetimes

![]() yr

and the relativistic electrons have lifetimes

yr

and the relativistic electrons have lifetimes

![]() yr,

the current radio luminosity is nearly proportional to the rate of

massive star-formation during the past

yr,

the current radio luminosity is nearly proportional to the rate of

massive star-formation during the past

![]() yr

(Condon et al. 2002):

yr

(Condon et al. 2002):

where

Table 1

compiles also all the 1.4 GHz radio-continuum flux data available for

our WR galaxy sample in the literature. The 1.4 GHz

luminosity, ![]() ,

can be computed using the expression given by Yun et al. (2001):

,

can be computed using the expression given by Yun et al. (2001):

where the result is given in units of W Hz-1, the distance d is expressed in Mpc and

Radio-continuum observations at several cm wavelengths are used to

quantify the thermal and nonthermal contributions, and thereby

distinguish older and supernova-rich regions from younger and mostly

thermal areas (i.e., Deeg et al. 1993; Beck et al.

2000; Cannon et al. 2004,

2005). These observations also permit detecting of extremely young,

dense, heavily embedded star clusters (Kobulnicky & Johnson 1999;

Johnson & Kobulnicky 2003).

Although radio data at frequencies different from 1.4 GHz are

not usually available for this kind of galaxy, we applied the equation

provided by Dopita et al. (2002),

to obtain an estimation of the thermal emission at 1.4 GHz,

Table 2: FIR and FUV data for the WR galaxy sample analyzed in this work.

2.2 FIR data

Many of the problems found to derive the S FR

from optical data can be avoided by measuring the far-infrared (FIR)

and submillimeter spectral energy distributions (SEDs). These are

determined by the re-radiation as thermal continuum by the dust grains

of stellar photospheric radiation absorbed in the visible and UV

regions of the spectrum. Assuming that the dust completely surrounds

the star-forming regions, it acts as a bolometer reprocessing the

luminosity produced by the stars. Therefore, the S FR

can be also computed

using theoretical stellar flux distributions and evolutionary models.

Kennicutt (1998)

provides the following correlation between the S FR

(in units of ![]() yr-1)

and the far-infrared flux:

yr-1)

and the far-infrared flux:

where

with f60 and f100 the flux densities (in Jy) for 60

Assuming that all the UV and blue radiation from massive stars

is absorbed by grains and is re-emitted as thermal radiation in the

40-120 ![]() m

band, Condon (1992)

derives the following relation between S FR

and

m

band, Condon (1992)

derives the following relation between S FR

and ![]() (in units of W Hz-1):

(in units of W Hz-1):

i.e.,

| (9) |

with

Roussel et al. (2001) provide

an alternative S FR calibration using the

15 ![]() m

luminosity:

m

luminosity:

where

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=0,width=18cm,clip]{14295fg01.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/13/aa14295-10/Timg74.png)

|

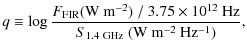

Figure 1: Example of GALEX images, showing the FUV emission in HCG 31, Haro 15 and SBS 0926+606. Regions within each object have been labeled following the notation given in Paper I. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

The warm dust mass can be estimated using the 60 and 100 ![]() m fluxes and

applying the relation given by Huchtmeier et al. (1995),

m fluxes and

applying the relation given by Huchtmeier et al. (1995),

where the distance is expressed in Mpc, the flux densities are in Jy, and the result is given in

We used the far-infrared (FIR) data provided by the Infrared

Astronomical Satellite (IRAS) to obtain the monochromatic

fluxes at 12, 25, 60, and 100 ![]() m. These data were used to independently estimate

the S FR and to derive the warm dust mass

within each galaxy. We also checked if the galaxies follow the

FIR-radio relationship. Table 2 compiles all

the FIR data found for our sample of WR galaxies, and three of

them have no useful measurements at these frequencies.

m. These data were used to independently estimate

the S FR and to derive the warm dust mass

within each galaxy. We also checked if the galaxies follow the

FIR-radio relationship. Table 2 compiles all

the FIR data found for our sample of WR galaxies, and three of

them have no useful measurements at these frequencies.

2.3 FUV data

In the past few years, the GALaxy Evolution eXplorer

(GALEX) satellite has been providing astonishing ultraviolet (UV)

images of galaxies and revealing recent star-formation activity in

their external regions (i.e., Gil de Paz 2005, 2007; Thilker

et al. 2005;

Koribalski & López-Sánchez 2009). The

GALEX point spread function in the central 0.5![]() has a full width at half-maximum of

has a full width at half-maximum of ![]() 5 arcsec, matching the spatial

resolution of our optical/NIR images quite nicely.

We searched for GALEX observations of the galaxies that compose our

sample in the far-UV-band (FUV,

1350-1750 Å), all of them have useful FUV data

except four objects (Mkn 1087, Mkn 1199,

SBS 0948+532 and III Zw 107).

5 arcsec, matching the spatial

resolution of our optical/NIR images quite nicely.

We searched for GALEX observations of the galaxies that compose our

sample in the far-UV-band (FUV,

1350-1750 Å), all of them have useful FUV data

except four objects (Mkn 1087, Mkn 1199,

SBS 0948+532 and III Zw 107).

In general, the FUV emission of our sample galaxies matches

their optical emission fairly closely. In many cases, FUV emission is

much more extended than the H![]() emission. Figure 1

shows the examples of the GALEX FUV images of HCG 31,

Haro 15, and SBS 0926+606. As we can see when

comparing with our optical images (see Paper I), the

star-forming regions are clearly observed in FUV. Brief comments about

three galaxies follow.

emission. Figure 1

shows the examples of the GALEX FUV images of HCG 31,

Haro 15, and SBS 0926+606. As we can see when

comparing with our optical images (see Paper I), the

star-forming regions are clearly observed in FUV. Brief comments about

three galaxies follow.

- The eastern tail of SBS 0926+606 B is

quite bright in the FUV image, suggesting an extended distribution of

massive OB stars that we do not detect in our deep H

image (see Fig. 15 and Sect. 3.10.1 in

Paper I);

image (see Fig. 15 and Sect. 3.10.1 in

Paper I);

- the star-forming galaxy #15 in Tol 1457-262 is clearly detected in the FUV emission, but the faint galaxy #16 is not seen (Fig. 31 and Sect. 3.18.1 in Paper I); and

- in Arp 252, FUV emission is detected not only at the center of the galaxies (ESO 566-8 and ESO 566-7) but also throughout the tails and in tidal dwarf candidates c, e, and d (see Fig. 34 and Sect. 3.19.1 in Paper I).

where

The seven column in Table 2 indicates the region within each system for which we derived the FUV flux. The FIR emission provided by IRAS does not allow distinguishing between these regions, but FUV data provided by GALEX does. In Arp 252, region A is galaxy ESO 566-8 and region B is galaxy ESO 566-7 (see Sect. 3.19 in Paper I).

Table 3: X-ray data available for our WR galaxy sample.

2.4 X-ray data

Finally, we also looked for the X-ray data available for our

WR galaxy sample. Only four objects

(HCG 31 AC, IRAS 08339+6517, Tol 9

and NGC 5253) have been observed at these high frequencies;

their X-ray luminosities are compiled in Table 3. In the case of

Tol 9, the upper limit to the X-ray luminosity was derived

from the upper limit to the X-ray flux reported by Fabbiano

et al. (1982),

![]() erg cm-2 s-1,

and assuming a distance of 86.6 Mpc (see

Table 1, Paper I). We then multiplied the derived

X-ray luminosity by 0.72 to correct for the X-ray range.

Beside these data, we also use (see Sect. 3.3) the

WR galaxy sample that Stevens & Strickland (1998a,b)

observed in X-ray.

erg cm-2 s-1,

and assuming a distance of 86.6 Mpc (see

Table 1, Paper I). We then multiplied the derived

X-ray luminosity by 0.72 to correct for the X-ray range.

Beside these data, we also use (see Sect. 3.3) the

WR galaxy sample that Stevens & Strickland (1998a,b)

observed in X-ray.

3 Analysis of the star-formation rates

The S FR, defined as the stellar mass

formed per unit time, is the standard parameter used to quantify the

star-formation activity in galaxies. Determination of the S FR

is fundamental to a proper understanding of the formation and evolution

of the galaxies. As said in the introduction, different techniques

involving different data sets from UV to radio

often yield different S FR results. Part of

the problem is related to the unknown amount of extinction within each

particular galaxy (Calzetti 2001),

such as the amount of dust obscuration depending on the galaxy mass,

galaxy type, the chemical evolutionary state, gas content, or even if

the galaxy is interacting or merging with another independent object.

As explained in the previous section, FIR and radio data provide an

extinction-free estimation of the S FR,

while FUV emission nicely traces the very young stellar component.

Here, we analyzed all the available multiwavelength data for our sample

of WR galaxies, including our reddening-corrected H![]() estimations (see Paper I), to determine the S FR

within these objects in a comprehensive way.

estimations (see Paper I), to determine the S FR

within these objects in a comprehensive way.

Table 4:

FUV, U, B, H![]() ,

H, FIR, 15

,

H, FIR, 15 ![]() m, 60

m, 60 ![]() m,

and 1.4 GHz luminosities for all galaxies analyzed in this

work.

m,

and 1.4 GHz luminosities for all galaxies analyzed in this

work.

Table 5:

S FR values (in units of ![]() yr-1)

derived for each galaxy using different luminosities and calibrations.

yr-1)

derived for each galaxy using different luminosities and calibrations.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=16.5cm,clip]{14295fg02.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/13/aa14295-10/Timg94.png)

|

Figure 2:

Comparison between the H |

| Open with DEXTER | |

We used the values listed in Table 4 to estimate the S FR

that each object experiences, following the different multiwavelength

techniques explained in the previous section. Table 5 compiles all S FR

values derived for each galaxy. The values of the H![]() -based S FR

listed in this table were extracted from Paper I and consider

the Kennicutt (1998)

calibration. Recently, Calzetti et al. (2007)

re-calibrated the relationship between the H

-based S FR

listed in this table were extracted from Paper I and consider

the Kennicutt (1998)

calibration. Recently, Calzetti et al. (2007)

re-calibrated the relationship between the H![]() -luminosity and the S FR;

the H

-luminosity and the S FR;

the H![]() -based

values of the S FR provided by Calzetti

et al. (2007)

are 0.67 times the values derived using the Kennicutt (1998)

calibration.

-based

values of the S FR provided by Calzetti

et al. (2007)

are 0.67 times the values derived using the Kennicutt (1998)

calibration.

From Table 5,

it is evident that the agreement between values obtained with different

methods is usually good, although sometimes we find clear discrepancies

(i.e. POX 4, NGC 5253). For systems that involve two

or more galaxies (HCG 31, SBS 0926+606,

Tol 1457-262, and Arp 252), we list both the global

and individual S FRs, because the FIR and

the radio data do not have enough spatial resolution to distinguish the

emission coming from different members, but FUV and H![]() data do. We also considered HCG 31 F1 and F2 as a

single entity (HCG 31 F) because the available

H I data include both TDG

candidates.

data do. We also considered HCG 31 F1 and F2 as a

single entity (HCG 31 F) because the available

H I data include both TDG

candidates.

Figure 2

compares our H![]() -based

S FR (corrected for both extinction and [N II]

contribution as explained in Appendix C of Paper I)

with the S FR estimations derived from FIR,

15

-based

S FR (corrected for both extinction and [N II]

contribution as explained in Appendix C of Paper I)

with the S FR estimations derived from FIR,

15 ![]() m,

60

m,

60 ![]() m,

and 1.4 GHz luminosities. The diagram involving

m,

and 1.4 GHz luminosities. The diagram involving

![]() seems

to show a higher scatter at higher S FR,

but this calibration is more uncertain. As a particular case,

Arp 252 always shows a disagreement between the S FR

derived from H

seems

to show a higher scatter at higher S FR,

but this calibration is more uncertain. As a particular case,

Arp 252 always shows a disagreement between the S FR

derived from H![]() and other parameters, noticeable with the 1.4 GHz luminosity.

The main object within Arp 252 is the bright galaxy

ESO 566-8. This behavior, together with the

FIR-radio-continuum relation not being satisfied in this system (see

below), strongly suggest that ESO 566-8 has some activity

different to its starbursting nature (an AGN or a radio-galaxy),

something we already commented on when we analyzed this system (see

Sect. 3.19.2 of Paper I). The rest of the objects

agree fairly well when comparing values obtained from different

calibrations. As previous authors have

pointed out (i.e. Dopita et al. 2002; James

et al. 2005),

the correction of the H

and other parameters, noticeable with the 1.4 GHz luminosity.

The main object within Arp 252 is the bright galaxy

ESO 566-8. This behavior, together with the

FIR-radio-continuum relation not being satisfied in this system (see

below), strongly suggest that ESO 566-8 has some activity

different to its starbursting nature (an AGN or a radio-galaxy),

something we already commented on when we analyzed this system (see

Sect. 3.19.2 of Paper I). The rest of the objects

agree fairly well when comparing values obtained from different

calibrations. As previous authors have

pointed out (i.e. Dopita et al. 2002; James

et al. 2005),

the correction of the H![]() fluxes for both extinction and [N II]

emission is vital to a reliable estimation of the SFR using H

fluxes for both extinction and [N II]

emission is vital to a reliable estimation of the SFR using H![]() -images.

-images.

Although the agreement between the H![]() -based S FR

and the S FRs derived using FIR and radio

luminosities is good, we observe that the values provided using the H

-based S FR

and the S FRs derived using FIR and radio

luminosities is good, we observe that the values provided using the H![]() luminosity are slightly higher than those estimated using the other

calibrations. The difference seems to be higher at lower H

luminosity are slightly higher than those estimated using the other

calibrations. The difference seems to be higher at lower H![]() -luminosities.

A linear fit to the data (Fig. 2)

confirms this trend. The zero-points of the fits (0.59, 0.52, 0.58,

0.68 for the H

-luminosities.

A linear fit to the data (Fig. 2)

confirms this trend. The zero-points of the fits (0.59, 0.52, 0.58,

0.68 for the H![]() -FIR,

H

-FIR,

H![]() -1.4 GHz,

H

-1.4 GHz,

H![]() -60

-60 ![]() m, and H

m, and H![]() -15

-15 ![]() m relations,

respectively) indicate that, for S FR = 1

m relations,

respectively) indicate that, for S FR = 1 ![]() yr-1,

the value of the S FR provided by H

yr-1,

the value of the S FR provided by H![]() -luminosity

is

-luminosity

is ![]() 0.6 times

the S FR values estimated using the other

relations. Bell (2003)

concludes that both radio and FIR luminosities underestimate the S FR

for low-luminosity galaxies because the nonthermal emission seems to be

suppressed by a factor of 2-3 in dwarf objects. However, the difference

is not significant if we use the Calzetti et al. (2007)

calibration instead of the Kennicutt (1998)

calibration to derive the H

0.6 times

the S FR values estimated using the other

relations. Bell (2003)

concludes that both radio and FIR luminosities underestimate the S FR

for low-luminosity galaxies because the nonthermal emission seems to be

suppressed by a factor of 2-3 in dwarf objects. However, the difference

is not significant if we use the Calzetti et al. (2007)

calibration instead of the Kennicutt (1998)

calibration to derive the H![]() -based

S FR.

-based

S FR.

The comparison of the FUV-based with the H![]() -based S FR

(Fig. 3)

also shows good agreement: except for some few objects (remarkably

SBS 0926+606 B

-based S FR

(Fig. 3)

also shows good agreement: except for some few objects (remarkably

SBS 0926+606 B![]() ),

both relations provide similar values. We also observe that the

FUV-based S FRs seem to be slightly lower

than the H

),

both relations provide similar values. We also observe that the

FUV-based S FRs seem to be slightly lower

than the H![]() -based

S FRs. A linear fit to the data (shown in

Fig. 3

with a continuous green line and with a correlation coefficient of r=0.927)

indicates that the FUV-based S FR is, on

average,

-based

S FRs. A linear fit to the data (shown in

Fig. 3

with a continuous green line and with a correlation coefficient of r=0.927)

indicates that the FUV-based S FR is, on

average, ![]() 0.71

times the H

0.71

times the H![]() -based

S FR. This value is similar to the factors

found before when comparing the H

-based

S FR. This value is similar to the factors

found before when comparing the H![]() -based S FR

with the FIR- and radio-based S FRs.

Interestingly, all these numbers are coincident with the ratio between

the Kennicutt (1998)

and the Calzetti et al. (2007)

calibrations to the S FR using the H

-based S FR

with the FIR- and radio-based S FRs.

Interestingly, all these numbers are coincident with the ratio between

the Kennicutt (1998)

and the Calzetti et al. (2007)

calibrations to the S FR using the H![]() flux,

flux, ![]() (H

(H![]() )/

)/

![]() (H

(H![]() )=0.67. We therefore conclude

that the new H

)=0.67. We therefore conclude

that the new H![]() -based

calibration provided by Calzetti et al. (2007) should

be preferred over the widely-used Kennicutt (1998)

calibration when computing the S FR from H

-based

calibration provided by Calzetti et al. (2007) should

be preferred over the widely-used Kennicutt (1998)

calibration when computing the S FR from H![]() luminosities. The S FR estimated for each

object by

considering all available multiwavelength data and listed in last

column of Table 5,

was computed considering the Calzetti et al. (2007) value.

Finally, we must say that there is increasing evidence that the H

luminosities. The S FR estimated for each

object by

considering all available multiwavelength data and listed in last

column of Table 5,

was computed considering the Calzetti et al. (2007) value.

Finally, we must say that there is increasing evidence that the H![]() luminosity underestimates the S FR relative

to the FUV luminosity in dwarf galaxies with S FR

luminosity underestimates the S FR relative

to the FUV luminosity in dwarf galaxies with S FR ![]() 0.01

0.01 ![]() yr-1

(i.e., Lee et al. 2009;

Pflamm-Altenburg et al. 2009), so the

FUV-based S FR should be preferred over the

H

yr-1

(i.e., Lee et al. 2009;

Pflamm-Altenburg et al. 2009), so the

FUV-based S FR should be preferred over the

H![]() -based S FR

in those systems.

-based S FR

in those systems.

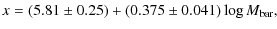

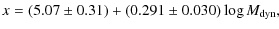

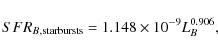

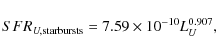

3.1 LB-SFR and LU-SFR relations for starburst galaxies

Just for comparison, we also estimated the S FR from the B-luminosity using the calibration provided by Gallagher et al. (1984). SFRB represents the star-formation activity that occurred in the past few hundred Myr, while the rest of the calibrations trace the massive stars and the nebular emission of the gas that only last for some few tens of Myr. For our galaxy sample, SFRB is always lower than the S FR derived from the other calibrations, as we should expect because of the starbursting nature of the analyzed galaxies. The value of the S FRB in Mkn 1087 using the Gallagher et al. (1984) equation is only half of what is estimated from other calibrators, noting its luminous blue compact galaxy (LCBG) nature (López-Sánchez et al. 2004b).

We used our data to establish a new relation between the S FR

and the B-luminosity, which should ony be applied

in starburst galaxies and just as a first estimation of the actual S FR.

The left panel of Fig. 4

shows the relation between LB

(in solar units) and the assumed S FR for

all our galaxies. Despite some clear discrepancies between some

galaxies that show very different S FR for

a similar B-luminosity (for example, just compare

members G and F of HCG 31), we see a good agreement, having galaxies

with higher B-luminosities higher star-formation

activity. The discrepancies are a consequence of the different

star-formation histories of the galaxies (relative contribution and age

of the underlying stellar population, metallicity, age of the most

recent star-formation event). A linear fit to our data provides the

relation

where LB is expressed in units of

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{14295fg03.eps}\protect

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/13/aa14295-10/Timg98.png)

|

Figure 3:

Comparison between the H |

| Open with DEXTER | |

We also computed a relation between the S FR

and the U-luminosity for our sample galaxies. The

right panel of Fig. 4

shows such a relation. A linear fit to the data yields

with LU expressed in units of

3.2 Comparison of SFR and metallicity

The left panel of Fig. 5

compares the assumed S FR with the oxygen

abundance computed for each galaxy. We estimated the average S FR

values in the low (12+log(O/H) < 7.8),

intermediate

(7.8 < 12+log(O/H) < 8.3),

and high (12+log(O/H) > 8.3) metallicity

regimes. As we see, the dispersion in the intermediate-metallicity

range is quite high, but that is just the consequence of the

star-formation

history of each particular galaxy (see Paper IV), because both

very dwarf objects (i.e., Mkn 5, SBS 1054+365) and

large and bright star-forming galaxies (i.e., Tol 1456-262,

III Zw 107) lie in this metallicity regime, and they

share a relatively similar chemical history. Besides the large

dispersion in the intermediate-metallicity regime, it is clear that

galaxies with higher metallicity have higher global S FRs.

That is a consequence of the building of the galaxies, because more

massive objects are more metal-rich than less massive galaxies (see

below), so that when the starburst is initiated, galaxies with higher

mass (and with higher metallicities) will create stars at a higher rate

than those found in smaller objects. The comparison of the S FR

per B-luminosity, S FR/LB

with the metallicity (Fig. 5,

right) also

shows a tremendous dispersion for 12+log(O/H) between 8.0 and 8.2.

However, we observe that S FR/LB

decreases with increasing oxygen abundance indicating that galaxies

with lower metallicity (therefore, less massive objects) have stronger

burst of star-formation than those found in higher metallicity (more

massive) objects.

SBS 0948+532 has the highest S FR/LB

in our sample, indicating the strength of the starburst, as we saw when

we analyzed its photometric properties (see Sect. 3.11 in

Paper I). On the other hand, SBS 1319+579 has low S FR/LB

than BCDGs with similar characteristics, indicating the peculiarity of

this galaxy. We see below that other properties of

SBS 1319+579 show additional discrepancies with the average

behavior in BCDGs, suggesting that the star-formation activity has been

somewhat suppressed in this object. For example, the gas depletion

timescale is extremely long for a starburst galaxy, (

![]() Gyr, see

Table 6).

Gyr, see

Table 6).

![\begin{figure}

\par\begin{tabular}{cc}

\includegraphics[angle=270,width=8cm,clip...

...ngle=270,width=8cm,clip]{14295fg04b.eps}\\

\end{tabular}\protect %

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/13/aa14295-10/Timg101.png)

|

Figure 4: Assumed S FR vs. B-luminosity (left panel) and U-luminosity (right panel) for the analyzed galaxies. Luminosities are plotted in solar units. The best fit (in logarithm scale) to our data is plotted with a continuous red line. The previous calibration given by Gallagher et al. (1984) between the S FR and the B-luminosity is shown by a discontinuous green line. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\begin{tabular}{cc}

\includegraphics[angle=270,width=8cm,clip...

...gle=270,width=8cm,clip]{14295fg05b.eps}\\

\end{tabular}

\protect

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/13/aa14295-10/Timg102.png)

|

Figure 5: S FR vs. 12+log(O/H) (left) and S FR/LB vs. 12+log(O/H) (right) for our sample of WR galaxies. The red-dotted line indicates a fit to our data. Green diamonds in the left panel plot the average value obtained in the low, intermediate, and high-metallicity regimes. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

3.3 An LX-SFR relation for starburst galaxies

Although several relations between the X-ray luminosity and the S FR

have been proposed (i.e., Ranalli et al. 2003; Lou

& Bian 2005)

they do not seem to be appropriate for young starbursting systems. For

example, as we explained in the analysis of the LCBG

IRAS 08339+6517 (López-Sánchez et al. 2006), the

relation provided by Ranalli et al. (2003) gives a

higher S FR value (61.8 ![]() yr-1)

than the estimations obtained using other frequencies (6-8

yr-1)

than the estimations obtained using other frequencies (6-8 ![]() yr-1).

Stevens & Strickland (1998a)

show that the X-ray luminosities in WR galaxies are

substantially higher than those found in non-WR galaxies with

similar B-luminosity. That is a consequence of the

higher rate of superbubbles and supernova explosions in

WR galaxies.

yr-1).

Stevens & Strickland (1998a)

show that the X-ray luminosities in WR galaxies are

substantially higher than those found in non-WR galaxies with

similar B-luminosity. That is a consequence of the

higher rate of superbubbles and supernova explosions in

WR galaxies.

We used the sample of WR galaxies analyzed by Stevens

& Strickland (1998a,b)

to get a tentative calibration between S FR

and ![]() for this kind of object. These authors obtained X-ray data in the

0.2-2.0 keV range using the satellite ROSAT. We checked which

of these galaxies also possess FIR data from the IRAS satellite, and

established a relation between

for this kind of object. These authors obtained X-ray data in the

0.2-2.0 keV range using the satellite ROSAT. We checked which

of these galaxies also possess FIR data from the IRAS satellite, and

established a relation between

![]() and

and ![]() ,

as shown in Fig. 6.

Only 18 galaxies have available data for both luminosities.

NGC 5253 was included in the Stevens & Strickland (1998a,b)

analysis, but they indicate that the X-ray emission in this object is

very peculiar. The X-ray emission measured in NGC 5408 may be

unrelated to the galaxy. Neglecting the contribution of these two

galaxies, the linear fit to the data thus gives

,

as shown in Fig. 6.

Only 18 galaxies have available data for both luminosities.

NGC 5253 was included in the Stevens & Strickland (1998a,b)

analysis, but they indicate that the X-ray emission in this object is

very peculiar. The X-ray emission measured in NGC 5408 may be

unrelated to the galaxy. Neglecting the contribution of these two

galaxies, the linear fit to the data thus gives

| (16) |

where the correlation coefficient r=0.929. Considering the calibration given by Kennicutt (1998) between

As seen in Fig. 6, our new S FR-

Table 6: Additional FIR and radio properties.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{14295fg06.eps}\protect

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/13/aa14295-10/Timg109.png)

|

Figure 6:

X-ray luminosity in the 0.2-2.0 keV range vs. FIR luminosity

for the sample of WR galaxies analyzed by Stevens &

Strickland (1998a,b).

The red continuous line is the best fit to the data, excluding the

values for NGC 5253 and NGC 5408. The green

discontinuous line is the relation obtained using the S FR- |

| Open with DEXTER | |

4 FIR/radio correlation

We used the luminosity data shown in Table 4 to check that our

WR galaxies follow the FIR/radio correlation. As shown by

Condon et al. (1992),

the FIR/radio correlation is much tighter for starbursts than for

active galaxies. Figure 7

(left) plots the 1.4 GHz luminosity vs. the 60 ![]() m luminosity

for our sample galaxies and the relation between both quantities found

by Yun et al. (2001),

m luminosity

for our sample galaxies and the relation between both quantities found

by Yun et al. (2001),

while Fig. 7 (right) shows

Bell (2003) pointed out that the radio-FIR correlation is linear not because both radio and FIR emission track S FR, but rather because they fail to track S FR in independent, but coincidentally quite similar, ways. Further analysis (i.e., Hunt et al. 2005) also found that this relation does not hold for some low-metallicity or young starbursts galaxies. However, as seen in Fig. 7, all analyzed objects except Mkn 5 (which has a very uncertain value for FIR) and Arp 252 (ESO 566-8 hosts some kind of nuclear activity) follow both relations. This indicates that the galaxies are starbursting systems and are not active galaxies (Seyfert or AGNs). We already reached this conclusion when we analyzed the diagnostic diagrams involving several emission-line ratios (see Paper III). Figure 7 includes a linear fit (in logarithmic scale) to our data (neglecting Mkn 5, for which the FIR values have high uncertainties). The relation given by Condon et al. (1991) seems to be slightly displaced with respect our observational data, although we also see some small discrepancies in the Yun et al. (2001) relation for the faintest objects.

The non-AGN nature of our sample of WR galaxies is

also supported by the analysis of the q parameter

an the FIR spectral index. The q parameter is

defined as the logarithmic ratio of FIR to radio flux density,

and it is very robust for most galaxy populations:

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=18cm,clip]{14295fg07.eps}\protect

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/13/aa14295-10/Timg114.png)

|

Figure 7:

1.4 GHz radio-continuum luminosity vs. the 60 |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=270,width=9cm,clip]{14295fg08.eps}\protect

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/13/aa14295-10/Timg115.png)

|

Figure 8:

Comparison of the B-luminosity (in solar units) and

the logarithmic nonthermal to thermal ratio, |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Table 7:

Keplerian mass (

![]() ), dynamical mass (

), dynamical mass (

![]() ), neutral gas mass (

), neutral gas mass (

![]() ), ionized gas mass (

), ionized gas mass (

![]() ), warm dust mass (

), warm dust mass (

![]() ), mass of the ionizing star

cluster (

), mass of the ionizing star

cluster (![]() ),

total stellar mass (

),

total stellar mass (

![]() ), and baryonic mass (

), and baryonic mass (

![]() )

of the galaxies analyzed in this work.

)

of the galaxies analyzed in this work.

Table 6

also compiles the nonthermal to thermal ratio R of

the galaxies with available 1.4 GHz radio-continuum data. The

thermal flux at 1.4 GHz was computed by applying Eq. (5). The majority

of the galaxies show the typical value for star-forming galaxies,

![]() Dopita

et al. (2002).

The low value in R found in POX 4 and

NGC 5253 may be because the H

Dopita

et al. (2002).

The low value in R found in POX 4 and

NGC 5253 may be because the H![]() flux has been overestimated, although the situation of

NGC 5253 is far from clear (López-Sánchez et al. 2010a). The

value obtained for SBS 1054+365 is unreliable, we consider

that it or the 1.4 GHz flux was underestimated (very probably)

or that the H

flux has been overestimated, although the situation of

NGC 5253 is far from clear (López-Sánchez et al. 2010a). The

value obtained for SBS 1054+365 is unreliable, we consider

that it or the 1.4 GHz flux was underestimated (very probably)

or that the H![]() flux was overestimated. However, the high value found in

Arp 252 (the emission comes mainly from ESO 566-8),

flux was overestimated. However, the high value found in

Arp 252 (the emission comes mainly from ESO 566-8),

![]() ,

is real and indicates that the thermal flux at 1.4 GHz is less

than 0.5%. As reported by several authors (i.e., Klein et al.

1984, 1991; Bell 2003),

dwarf galaxies seem to have a lower nonthermal-to-thermal emission

ratio than normal spiral galaxies. The values obtained for the R

parameter in our galaxy sample tend to be lower at lower B-luminosities,

as shown in Fig. 8.

The difference between dwarf and larger galaxies is often interpreted

as the higher efficiency of cosmic-ray confinement in more massive

galaxies (e.g., Klein et al. 1984; Price & Duric 1992;

Niklas et al. 1997;

Bell 2003).

,

is real and indicates that the thermal flux at 1.4 GHz is less

than 0.5%. As reported by several authors (i.e., Klein et al.

1984, 1991; Bell 2003),

dwarf galaxies seem to have a lower nonthermal-to-thermal emission

ratio than normal spiral galaxies. The values obtained for the R

parameter in our galaxy sample tend to be lower at lower B-luminosities,

as shown in Fig. 8.

The difference between dwarf and larger galaxies is often interpreted

as the higher efficiency of cosmic-ray confinement in more massive

galaxies (e.g., Klein et al. 1984; Price & Duric 1992;

Niklas et al. 1997;

Bell 2003).

5 Analysis of the masses

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=16.5cm,clip]{14295fg09.eps}\protect

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/13/aa14295-10/Timg118.png)

|

Figure 9:

Ionized gas mass (

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=270,width=17.5cm,clip]{14295fg10.eps}\protect

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/13/aa14295-10/Timg119.png)

|

Figure 10:

Dynamical mass (

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

For this work, we estimated the ionized gas mass

![]() ,

using the H

,

using the H![]() images presented in Paper I; neutral gas mass

images presented in Paper I; neutral gas mass

![]() ,

using H I data at 21 cm compiled

from the literature; mass of the ionizing star cluster

,

using H I data at 21 cm compiled

from the literature; mass of the ionizing star cluster ![]() ,

using H

,

using H![]() and W(H

and W(H![]() ),

see Paper I; warm dust mass

),

see Paper I; warm dust mass

![]() ,

using the FIR fluxes; Keplerian mass

,

using the FIR fluxes; Keplerian mass

![]() ,

via the kinematics of the ionized gas; and dynamical mass

,

via the kinematics of the ionized gas; and dynamical mass

![]() ,

using the H I kinematics.

All these data are compiled in Table 7. The value of

,

using the H I kinematics.

All these data are compiled in Table 7. The value of

![]() compiled

in this table is for the entire system: all galaxies in the

HCG 31 group, members A and B in SBS 0926+606, all

galaxies in Tol 1457-262, and ESO 566-8 and

ESO 566-7 in Arp 252. We neglect the contribution of

the FIR emission in dwarf objects associated to larger galaxies

(companion objects surrounding Mkn 1087, Mkn 1199,

IRAS 08339+6519, and POX 4). The estimation of

compiled

in this table is for the entire system: all galaxies in the

HCG 31 group, members A and B in SBS 0926+606, all

galaxies in Tol 1457-262, and ESO 566-8 and

ESO 566-7 in Arp 252. We neglect the contribution of

the FIR emission in dwarf objects associated to larger galaxies

(companion objects surrounding Mkn 1087, Mkn 1199,

IRAS 08339+6519, and POX 4). The estimation of

![]() and

and

![]() for each

galaxy was explained in Paper II. We just remember

that, as the extension of the neutral gas is usually larger than the

stellar component, our estimations of

for each

galaxy was explained in Paper II. We just remember

that, as the extension of the neutral gas is usually larger than the

stellar component, our estimations of

![]() are very

probably underestimated. Furthermore, nonrotational movements

would yield an overestimation of the total mass. Only interferometric

H I analysis can

definitely provide a more precise determination of the dynamical mass

for each system. However, we may use our

are very

probably underestimated. Furthermore, nonrotational movements

would yield an overestimation of the total mass. Only interferometric

H I analysis can

definitely provide a more precise determination of the dynamical mass

for each system. However, we may use our

![]() values as a

rough estimation of the total mass of the galaxies. Their

comparison with

values as a

rough estimation of the total mass of the galaxies. Their

comparison with ![]() ,

,

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

and their associated mass-to-light ratios will give clues to the galaxy

type, dynamics and the fate of the neutral gas.

,

and their associated mass-to-light ratios will give clues to the galaxy

type, dynamics and the fate of the neutral gas.

We first compared all mass determinations with the optical

luminosity of the galaxies. Figure 9 shows the

relations between ![]() ,

,

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

and

,

and ![]() with the absolute B-magnitude. As we should expect,

besides some scatter, all mass determinations clearly increase with

increasing optical luminosity. We performed a linear fit to the data,

and the results are

with the absolute B-magnitude. As we should expect,

besides some scatter, all mass determinations clearly increase with

increasing optical luminosity. We performed a linear fit to the data,

and the results are

with correlation coefficients of 0.899, 0.922, 0.912, and 0.928, respectively. Some deviations to the fits are found in Mkn 1199 (that possesses a relatively low

Figure 10

plots the dynamical mass (which represents the total mass of the

galaxy) versus the absolute magnitude in several broad-band filters (B,

V, R, and J).

We find a clear correlation between these quantities, and a linear fit

to the data yields

with correlation coefficients r of 0.922, 0.931, 0.940, and 0.907, respectively. Slopes in all fits are quite similar. The most important deviations to these fits are found in clearly interacting systems (Mkn 1199 and HCG 31 AC) but also in Mkn 5 and SBS 1054+365.

We compared the Keplerian mass (derived from the kinematics of

the ionized gas) with the dynamical mass (estimated from the kinematics

of the neutral gas). Figure 11 plots both sets

of values. As expected, ![]() is lower than

is lower than ![]() for almost all cases (

for almost all cases (

![]() =

=

![]() is shown in Fig. 11).

Although the dispersion is high - and we remember that

is shown in Fig. 11).

Although the dispersion is high - and we remember that

![]() and/or

and/or

![]() may be

overestimate because of interaction features - we performed a

tentative fit to the data, which yields

may be

overestimate because of interaction features - we performed a

tentative fit to the data, which yields

with a correlation coefficient r=0.827. This relation is included in Fig. 11. As explained in Sect. 3.13 of Paper II,

Using Eqs. (25)-(28) and 29, we computed a

tentative value for the dynamical mass in the galaxies because of lack

of H I data. We included

the results in Table 7,

and plotted these points in Fig. 11. As we can see,

they match the positions of the galaxies for which

![]() was derived

from H I data,

but we will not consider these points in the subsequent analysis.

was derived

from H I data,

but we will not consider these points in the subsequent analysis.

We prefer to use our NIR data to derive

a proper value for the stellar mass of all the galaxies. Following the

description provided by Kirby et al. (2008), we may

assume an H-band mass-to-light ratio of

![]() to

compute the stellar mass,

to

compute the stellar mass,

![]() ,

from the H-luminosity (compiled for all objects in

Table 4).

This assumption is supported by both observations (Bell 2003; Kirby

et al. 2008)

and theory (de Jong 1996),

and it considers a 12 Gyr old solar metallicity stellar

population with a constant S FR and

Salpeter initial mass function. The H-band

mass-to-light ratio may therefore be somewhat overestimated for our

young galaxies. Combining the H-band derived

stellar mass and the H I mass

(we neglect the ionized gas, molecular gas, and dust contributions),

the total baryonic mass,

,

from the H-luminosity (compiled for all objects in

Table 4).

This assumption is supported by both observations (Bell 2003; Kirby

et al. 2008)

and theory (de Jong 1996),

and it considers a 12 Gyr old solar metallicity stellar

population with a constant S FR and

Salpeter initial mass function. The H-band

mass-to-light ratio may therefore be somewhat overestimated for our

young galaxies. Combining the H-band derived

stellar mass and the H I mass

(we neglect the ionized gas, molecular gas, and dust contributions),

the total baryonic mass, ![]() ,

can be computed via

,

can be computed via

| (30) |

where the factor 1.32 corrects the H I mass for the presence of helium. The derived values for both

As we should expect, the comparison between the dynamical and

the baryonic masses (Fig. 12)

indicates that ![]() is always higher than

is always higher than ![]() ,

except for IRAS 08339+6517, which has expelled a considerable

fraction of its neutral gas to the intergalactic medium and shows

disturbed H I kinematics

(Cannon et al. 2004)

with a long tidal stream that makes it impossible to get a good

estimation of

,

except for IRAS 08339+6517, which has expelled a considerable

fraction of its neutral gas to the intergalactic medium and shows

disturbed H I kinematics

(Cannon et al. 2004)

with a long tidal stream that makes it impossible to get a good

estimation of ![]() (López-Sánchez et al. 2006).

Besides the uncertainties in

(López-Sánchez et al. 2006).