| Issue |

A&A

Volume 521, October 2010

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A20 | |

| Number of page(s) | 10 | |

| Section | Extragalactic astronomy | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/200913518 | |

| Published online | 15 October 2010 | |

VLT observations of NGC 1097's ``dog-leg'' tidal stream![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

Dwarf spheroidals and tidal streams

P. Galianni1 - F. Patat2 - J. L. Higdon3 - S. Mieske4 - P. Kroupa5

1 - Undergraduate student, Universita del Salento, via per Arnesano 1, 73100 Lecce, Italy

2 - ESO European Southern Observatory, Karl

Schwarzschild str. 2, 85748 Garching bei Muenchen, Germany

3 - Department of Physics, Georgia Southern University, Statesboro, GA 30458, USA

4 - ESO European Southern Observatory, Alonso de Cordova, 3107 Vitacura, Santiago, Chile

5 - Argelander Institut für Astronomie, Auf dem Hügel 71, 53121 Bonn, Germany

Received 21 October 2009 / Accepted 1 June 2010

Abstract

Aims. We investigate the structure and stellar population of

two large stellar condensations (knots A & B) along one of the

faint optical ``jet-like'' tidal streams associated with the spiral

NGC 1097, with the goal of establishing their physical association

with the galaxy and their origin.

Methods. We use the VLT/FORS2 to get deep V-band imaging

and low-resolution optical spectra of two knots along NGC 1097's

northeast ``dog-leg'' tidal stream. With this data, we explore their

morphology and stellar populations.

Results. Spectra were obtained for eleven sources in the field

surrounding the tidal stream. The great majority of them turned out to

be background or foreground sources, but the redshift of knot A (and

perhaps of knot B) is consistent with that of NGC 1097. Using

the V-band image of the ``dog-leg'' tidal feature we find that the two

knots match the photometric scaling relations of canonical dwarf

spheroidal galaxies (dSph) very well. Spectral analysis shows that knot

A is mainly composed of stars near G-type, with no signs of ongoing

star formation. Comparing its spectrum with a library of high

resolution spectra of galactic globular clusters (GCs), we find that

the stellar population of this dSph-like object is most similar to

intermediate to metal rich galactic GCs. We find moreover, that the

tidal stream shows an ``S'' shaped inflection as well as a pronounced

stellar overdensity at knot A's position. This suggests that

knot A is being tidally stripped, and populating the stellar

stream with its stars.

Conclusions. We have discovered that two knots along

NGC 1097's northeast tidal stream share most of their spectral and

photometric properties with ordinary dwarf spheroidal galaxies (dSph).

Moreover, we find strong indications that the ``dog-leg'' tidal stream

arises from the tidal disruption of knot A. Since it has been

demonstrated that tidally stripping dSph galaxies need to loose most of

their dark matter before starting to loose stars, we suggest that

knot A is at present a CDM-poor object.

Key words: galaxies: dwarf - galaxies: interactions - galaxies: individual: NGC 1097 - galaxies : jets - globular clusters: individual: 47 Tucanae

1 Introduction

|

Figure 1:

FORS2/UT2 400 s Bessel V-band image of NGC 1097's northeast optical jet and ``dog-leg''.

The targets observed spectoscopically with FORS2 are labeled as in Table 1. The figure covers

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

1.1 The nature of NGC 1097's optical ``jet-like'' tidal streams

NGC 1097's network of faint optical ``jets'' have puzzled astronomers

since their discovery in the mid-1970s (Wolstencroft & Zealey 1975;

Arp 1976; Lorre 1978). These early observations established their

blue optical colors and lack of optical emission lines. The fact that

all four appear to radiate from NGC 1097's Seyfert 1 nucleus (see

Fig. 1 in Lorre 1978 and Fig. 1) led quite naturally to

explanations involving AGN phenomena. However, the sensitive

upper flux limits at 1.4 GHz set by Wolstencroft et al. (1984) with the

Very Large Array (VLA) showed that the ``jets'' optical emission did

not arise through the synchrotron process. Their observations could

not exclude the possibility that the ``jets'' were dominated by

thermal Bremsstrahlung emission from a ![]() 106 K plasma (the

high temperature is required to explain the absence of H

106 K plasma (the

high temperature is required to explain the absence of H![]() emission set by Arp 1976). The same year, Carter et al. (1984, hereafter CAM) proposed a very different interpretation based

on optical and near-infrared surface photometry of the two northern

jets and the most prominent of several optical knots in the northeast

jet first noted by Arp (1976) and Lorre (1978). The colors of the diffuse

light in the northern jets (e.g.,

emission set by Arp 1976). The same year, Carter et al. (1984, hereafter CAM) proposed a very different interpretation based

on optical and near-infrared surface photometry of the two northern

jets and the most prominent of several optical knots in the northeast

jet first noted by Arp (1976) and Lorre (1978). The colors of the diffuse

light in the northern jets (e.g.,

![]() and

and

![]() )

are inconsistent with both thermal Bremsstrahlung and

synchrotron emission. Instead, CAM proposed that the ``jet-like''

features are in fact composed of stars, similar to ordinary disk

populations (

)

are inconsistent with both thermal Bremsstrahlung and

synchrotron emission. Instead, CAM proposed that the ``jet-like''

features are in fact composed of stars, similar to ordinary disk

populations (![]() G-type). These stars either: formed in

situ from the cooling plasma of an ancient radio jet, were drawn out

of NGC 1097's disk through a tidal interaction with its companion

NGC 1097A, or represented the remains of a dwarf irregular or small

spiral galaxy cannibalized by the much larger NGC 1097 (i.e., a minor

merger). CAM went so far as to propose that the prominent optical knot

near the northeast jet's abrupt right-angle bend (called the

``dog-leg'') might be what is left of the dwarf's tidally-stripped

nucleus, given that its color (

G-type). These stars either: formed in

situ from the cooling plasma of an ancient radio jet, were drawn out

of NGC 1097's disk through a tidal interaction with its companion

NGC 1097A, or represented the remains of a dwarf irregular or small

spiral galaxy cannibalized by the much larger NGC 1097 (i.e., a minor

merger). CAM went so far as to propose that the prominent optical knot

near the northeast jet's abrupt right-angle bend (called the

``dog-leg'') might be what is left of the dwarf's tidally-stripped

nucleus, given that its color (

![]() )

is similar to

that of late-type spiral nuclei. Wehrle et al. (1997) used VLA

observations at 327 MHz to conclusively rule out the ``jet-like''

features being a network of ancient radio jets, and they concluded

that NGC 1097's jets are nothing more than a set of unusual tidal

streams created through multiple encounters with the small elliptical

companion NGC 1097A. Since tidal streams, and especially blue

tidal streams, are typically rich in neutral atomic hydrogen gas (HI),

this opened the interesting possibility of using HI kinematics to

explore their origin and evolution.

)

is similar to

that of late-type spiral nuclei. Wehrle et al. (1997) used VLA

observations at 327 MHz to conclusively rule out the ``jet-like''

features being a network of ancient radio jets, and they concluded

that NGC 1097's jets are nothing more than a set of unusual tidal

streams created through multiple encounters with the small elliptical

companion NGC 1097A. Since tidal streams, and especially blue

tidal streams, are typically rich in neutral atomic hydrogen gas (HI),

this opened the interesting possibility of using HI kinematics to

explore their origin and evolution.

Higdon & Wallin (2003, hereafter HW) revived the ``minor merger'' interpretation

for the tidal streams. Using the VLA in its most compact

configuration, they found that all four tidal streams are extremely

gas poor (

![]()

![]() pc-2, 3

pc-2, 3![]() ). Given their blue color, they are unlike any tidal stream in

the literature (cf. Hibbard et al. 2000; Higdon et al. 2006).

The total lack of HI had additional implications: the stars could not

have originated from the

HI rich disk of NGC 1097, nor could they have been formed in

situ from a cooling radio jet without unrealistic star formation

efficiencies. HW proposed a scenario in which the

tidal streams were formed by multiple passes of a gas rich dwarf

galaxy through the center of the much more massive NGC 1097. Their n-body

simulations of such a capture produced features that strikingly

resembled the four optical tidal streams, including the abrupt 90

). Given their blue color, they are unlike any tidal stream in

the literature (cf. Hibbard et al. 2000; Higdon et al. 2006).

The total lack of HI had additional implications: the stars could not

have originated from the

HI rich disk of NGC 1097, nor could they have been formed in

situ from a cooling radio jet without unrealistic star formation

efficiencies. HW proposed a scenario in which the

tidal streams were formed by multiple passes of a gas rich dwarf

galaxy through the center of the much more massive NGC 1097. Their n-body

simulations of such a capture produced features that strikingly

resembled the four optical tidal streams, including the abrupt 90![]() bend of the dog-leg region (see their Figs. 12-14). The

dwarf galaxy's ISM is swept out by ram pressure stripping during its

initial pass through NGC 1097's disk, resulting in the creation of

essentially gas free ``jet-like'' stellar streams. Within the HW picture,

NGC 1097's optical tidal streams represents the late stages

in the cannibalization of a small disk galaxy by a much larger spiral.

bend of the dog-leg region (see their Figs. 12-14). The

dwarf galaxy's ISM is swept out by ram pressure stripping during its

initial pass through NGC 1097's disk, resulting in the creation of

essentially gas free ``jet-like'' stellar streams. Within the HW picture,

NGC 1097's optical tidal streams represents the late stages

in the cannibalization of a small disk galaxy by a much larger spiral.

1.2 Structures in NGC 1097's northeast tidal stream

Arp (1976) and Lorre (1978) noted the presence of several optical

knots near the northeast tidal feature's dog-leg region (see

Figs. 1 and 3) that appeared too blue for

background ellipticals, though with no redshifts available the possibility that

they were background objects could not be ruled out. Wehrle et al. (1997) obtained 4000-7000 Å spectra of the two brightest knots

using 1-2 h exposures with the CTIO 4 m Blanco telescope, and

detected only weak continuum (after averaging over large wavelength

bins) and no measurable line emission (e.g.,

![]() Å and

Å and

![]() ,

,

![]() Å). Because of

detector instabilities, the quality of their spectra was not sufficient

to determine the nature of knots A & B. While it had yet to be

established that the knots were in fact part of the northeast tidal

stream, it was clear from their apparent lack of strong emission lines

that neither were star forming dwarf galaxies or distant AGN. The

existence of multiple knots are of particular interest, as they

might represent ongoing structure formation in the tidal streams.

Å). Because of

detector instabilities, the quality of their spectra was not sufficient

to determine the nature of knots A & B. While it had yet to be

established that the knots were in fact part of the northeast tidal

stream, it was clear from their apparent lack of strong emission lines

that neither were star forming dwarf galaxies or distant AGN. The

existence of multiple knots are of particular interest, as they

might represent ongoing structure formation in the tidal streams.

|

Figure 2: Up left: FORS2 spectrum of knot A. Up right: FORS2 spectrum of knot B. Bottom: comparison of knot A's spectrum (blue line) vs. knot B's (red line). |

| Open with DEXTER | |

In this paper we analyze VLT/FORS2 spectra of

five of the brightest optical knots in the northeast tidal stream. We

show that the most prominent condensation, knot A, has the same

redshift as the spiral NGC 1097, and argue that it is physically

associated with the tidal stream. A second condensation, knot B, is

also plausibly associated with the tidal feature![]() .

.

The VLT observations are described in Sect. 2. In

Sect. 3 we

present the photometric and spectroscopic measurements of knots A

& B, and discuss these findings and their implications in

Sect. 4. Finally, we summarize our results in Sect. 5.

Throughout this

paper we have adopted the standard WMAP cosmology (

![]() km s-1 Mpc-1; Spergel et al. 2003), which for NGC 1097's redshift (

km s-1 Mpc-1; Spergel et al. 2003), which for NGC 1097's redshift (

![]() ,

e.g., Koribalski et al. 2004; Mathewson & Ford 1996) results

in a luminosity distance

,

e.g., Koribalski et al. 2004; Mathewson & Ford 1996) results

in a luminosity distance ![]() of

of ![]() Mpc and a linear scale of

84 pc/

Mpc and a linear scale of

84 pc/

![]() .

.

2 VLT observations and data reduction

The observations were made at ESO-Paranal by

G. Rupprecht and H. Arp (observing program 66.B-0481) on several runs: 7 October 2000 (ID 101443),

17 November 2000 (ID 103791), and 4 December 2000 (ID 103790).

The data were kindly provided by Arp and Rupprecht.

Optical spectra were obtained with the FORS2 imaging-spectrograph

(1998), situated at the Cassegrain focus of the 8.2 m VLT Kueyen

(UT2). The detector was a 2048 ![]() 2048 TK2048EB4-1 thinned, backside illuminated CCD.

The standard resolution collimator was used, providing an angular

scale of 0.2

2048 TK2048EB4-1 thinned, backside illuminated CCD.

The standard resolution collimator was used, providing an angular

scale of 0.2

![]() /pix and a field of view of 6

/pix and a field of view of 6

![]() 8

8 ![]() 6

6

![]() 8.

Grism GRIS_150I+27 was used, which provides a linear dispersion of 230 Å/mm

and

8.

Grism GRIS_150I+27 was used, which provides a linear dispersion of 230 Å/mm

and

![]() (if coupled with a 1

(if coupled with a 1

![]() slit).

Spectra covering the full 3300-1000 Å wavelength range

were obtained in two stages: red spectra (6000-10 000 Å) using the

OG590+32 filter as an order blocker, and blue spectra

(3300-6600 Å)

with no filter.

slit).

Spectra covering the full 3300-1000 Å wavelength range

were obtained in two stages: red spectra (6000-10 000 Å) using the

OG590+32 filter as an order blocker, and blue spectra

(3300-6600 Å)

with no filter.

The observations were carried out in multi-object (MXU) mode, with

twelve slits of varying widths (1

![]() to 2.5

to 2.5

![]() )

placed on the

sky. One large slit was situated across the northeast tidal stream, one slit

each was placed on knots A & B, six on field objects, and three on

empty fields to measure sky emission. The integration time for the spectra was 30 min.

Data reduction was routine,

and standard procedures in IRAF

)

placed on the

sky. One large slit was situated across the northeast tidal stream, one slit

each was placed on knots A & B, six on field objects, and three on

empty fields to measure sky emission. The integration time for the spectra was 30 min.

Data reduction was routine,

and standard procedures in IRAF![]() were used to extract (apall),

calibrate (identify, calibrate), and join (scombine)

the red and blue spectrum for each slit.

See Table 1 for the coordinates,

photometry and a short description of the observed objects.

were used to extract (apall),

calibrate (identify, calibrate), and join (scombine)

the red and blue spectrum for each slit.

See Table 1 for the coordinates,

photometry and a short description of the observed objects.

The spectrum of the northeast tidal stream was too faint to be

successfully extracted with apall. Despite using the largest

available slit and the lowest dispersion grism available, the tidal stream proved too faint

for useful spectroscopy in 30 min of integration. We

obtained, however, well exposed spectra for nine other objects, including

knot A, and a less exposed but still useful spectrum of knot B (see Fig. 2).

FORS2 was also used to obtain a 400 s Bessel V-band exposure

centered on the northeast dog-leg tidal stream (see Fig. 1). The

night's seeing (FWHM of unsaturated stars measured on the image)

was ![]()

![]() .

.

3 Results

3.1 Spectroscopy of the condensations in the ``dog-leg'' tidal stream

The five optical condensations in the northeast tidal stream that were observed

spectroscopically with FORS2 are indicated in Fig. 1 and listed in

Table 1. Of these, one is a foreground star (Object 9) and two are background galaxies

(Objects 6 and 7), with

![]() .

We will not discuss these sources further.

.

We will not discuss these sources further.

A high quality spectrum was extracted for knot A, and is shown in

Fig. 2. The spectrum is notable for a total lack of emission lines

ordinarily found in star forming systems like [O III]

![]() 4959, 5007 Å, H

4959, 5007 Å, H![]() or H

or H![]() ,

in agreement with Arp (1976) and

Wehrle et al. (1997). However, these new observations set more

stringent limits on H

,

in agreement with Arp (1976) and

Wehrle et al. (1997). However, these new observations set more

stringent limits on H![]() emission, with

emission, with

![]() Å . Several narrow hydrogen Balmer absorption lines (H

Å . Several narrow hydrogen Balmer absorption lines (H![]() ,

H

,

H![]() ,

and H

,

and H![]() )

are clearly detected, with equivalent widths

(measured with IRAF's splot tool) of 2.9, 3.8 and 2.3 Å

respectively (see Table 2).

There is also evidence for a weak G-band (

)

are clearly detected, with equivalent widths

(measured with IRAF's splot tool) of 2.9, 3.8 and 2.3 Å

respectively (see Table 2).

There is also evidence for a weak G-band (![]() 4303 Å)

absorption. The most prominent feature in Fig. 2 is a strong break in the

continuum level at

4303 Å)

absorption. The most prominent feature in Fig. 2 is a strong break in the

continuum level at ![]() 4400 Å.

4400 Å.

We derive synthetic optical colors for knot A using the spectrum in Fig. 2

by numerically integrating over the Johnson-Cousins UBVRI passbands, and find

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

,

![]() and

and

![]() .

Note that these colors are somewhat redder than the colors of the local diffuse jet

emission as measured by CAM (

.

Note that these colors are somewhat redder than the colors of the local diffuse jet

emission as measured by CAM (

![]() ). The 1.8

). The 1.8![]() deviation

between our and CAM's measures is not surprising considering the inherent difficulty

in measuring the colors of such a low brightness feature, and the fact that CAM

performed those measures more than 20 yr ago, using normal photographic plates.

deviation

between our and CAM's measures is not surprising considering the inherent difficulty

in measuring the colors of such a low brightness feature, and the fact that CAM

performed those measures more than 20 yr ago, using normal photographic plates.

From the measured wavelengths of absorption lines in knot A's spectrum

(see Table 2) we derive a redshift of

![]() .

This is within

.

This is within

![]() of NGC 1097's redshift

derived using HI and optical emission lines, and shows that knot A is

indeed physically associated with the barred spiral galaxy.

of NGC 1097's redshift

derived using HI and optical emission lines, and shows that knot A is

indeed physically associated with the barred spiral galaxy.

As shown in Fig. 2 (upper-right panel) the two features in the spectrum of knot B,

being possibly significant above the noise are the break in the continuum level

at 4400 Å and the H![]() line at 4882 Å. As is shown in Fig. 2

(bottom panel) the overall continuum shape and the position of these two

features match fairly well those of knot A, indicating that their redshifts could be similar.

Under the assumption that knot B is at the same redshift distance of knot A,

we find moreover that knot B

agree very well with the same photometric scaling relations of knot A. This makes it unlikely

that knot B is a galaxy with a different absolute magnitude than knot A, placed at a different

distance from NGC 1097. We will therefore assume throughout the rest of the article that knot B is

physically associated with NGC 1097.

line at 4882 Å. As is shown in Fig. 2

(bottom panel) the overall continuum shape and the position of these two

features match fairly well those of knot A, indicating that their redshifts could be similar.

Under the assumption that knot B is at the same redshift distance of knot A,

we find moreover that knot B

agree very well with the same photometric scaling relations of knot A. This makes it unlikely

that knot B is a galaxy with a different absolute magnitude than knot A, placed at a different

distance from NGC 1097. We will therefore assume throughout the rest of the article that knot B is

physically associated with NGC 1097.

3.2 Surface photometry and morphology of knots A & B

Both knots A & B in the NE tidal stream are easily seen in the FORS2 V-band

image shown in Fig. 1. We are able to extract new details

concerning their morphologies: Knot A shows considerable spherical

symmetry, with a bright and compact core and a halo that extends for

the full width of the stream (![]()

![]() ), while knot B is more

diffuse and lacks a central core (see Fig. 3).

), while knot B is more

diffuse and lacks a central core (see Fig. 3).

|

Figure 3:

Closeups (

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

Table 1: Magnitudes of the observed objects: The labels fs, bg, c indicate respectively: ``foreground star'', ``backgroung galaxy'', ``condensation''. The typical rms errors for the magnitudes are 0.1 mag.

Table 2:

Absorption redshift of knot A:

![]() is the measured wavelength,

is the measured wavelength,

![]() is the rest-frame wavelength, z is the measured redshift and

is the rest-frame wavelength, z is the measured redshift and ![]() is

the redshift difference with NGC 1097 (z= 0.0042 NED).

is

the redshift difference with NGC 1097 (z= 0.0042 NED).

![\begin{displaymath}\mu (R) = \mu_{\rm e} \exp \left\{-b_{n}\left[\left(R \over R_{\rm e}\right)^{1/n}-1\right]\right\},

\end{displaymath}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/13/aa13518-09/img51.png)

|

(1) |

where R is the projected radial distance from the center of the galaxy. This representation is widely used and has the advantage of precisely describing a variety of SBPs, including pure exponential and de Vaucouleurs R1/4 laws, i.e., those of both dwarf and luminous elliptical galaxies (Faber & Lin 1983; de Vaucouleurs 1948, 1959). The free parameters of this model are

|

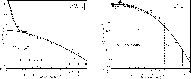

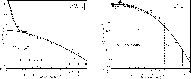

Figure 4:

Left: Knot A's surface brightness profile obtained with IRAF's

ellipse task. The continuos line represent the Sérsic n=0.6model fit. The dotted line delimits the seeing affected zone, while the

dash-dotted line is placed at

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

Accurate half-light radii have been computed for both objects. For knot B, we estimate

the half-light radius from the Sérsic model fit to be (see above)

![]() pc, where we have included contributions from the pixel

scale and saturation effects in the uncertainty.

Since knot A's core cannot be fit by a Sérsic profile, we estimate

an empirical half-light radius using the ellipse output to calculate the radius

at which the total flux drops by half. In this way we obtain

pc, where we have included contributions from the pixel

scale and saturation effects in the uncertainty.

Since knot A's core cannot be fit by a Sérsic profile, we estimate

an empirical half-light radius using the ellipse output to calculate the radius

at which the total flux drops by half. In this way we obtain

![]() pc.

pc.

Integrated apparent V-band magnitudes were determined to be

![]() mag and

mag and

![]() mag for knots A & B respectively, which correspond to absolute

magnitudes of

mag for knots A & B respectively, which correspond to absolute

magnitudes of

![]() and

and

![]() at the adopted distance

of NGC 1097. Assuming

at the adopted distance

of NGC 1097. Assuming

![]() (Bell & de Jong 2001), these translate into

V-band luminosities of

(Bell & de Jong 2001), these translate into

V-band luminosities of

![]()

![]() for knot A

and

for knot A

and

![]()

![]() for knot B. We also estimate mV, MV,

and LV for knot A's core using a circular aperture of radius

for knot B. We also estimate mV, MV,

and LV for knot A's core using a circular aperture of radius

![]() ,

and find

,

and find

![]() mag,

mag,

![]() and

and

![]()

![]() .

.

Dwarf galaxies subject to ongoing tidal perturbations may show surface brightness ``breaks'' or other irregularities in their outer isophotes (Peñarrubia et al. 2009). We are however unable to detect such irregularities in our surface brightness profiles (see Fig. 4).

This however does not necessarly imply that the knots are not being tidally stripped, since as shown by Peñarrubia et al. (2009) such ``bumps'' in the isophotes are essentially transient features that quickly drift in the outer region of the SBPs, where the S/N may be too low to give any useful information. Their eventual detection is therefore related to the time of the observation, and strongly depends on the orbital parameters of the tidally-disrupting object. Moreover, it is likely that the spatial resolution of our SBPs is simply insufficient to reveal these ``bumps'': our objects have in fact a very small angular extension if compared to Local Group (LG) dwarfs. It is however difficult to estimate the expected amplitude of these irregularities without knowing the orbit of the objects and their internal kinematics.

|

Figure 5: Left: Knot A's cross correlation amplitude as a function of metallicity for galactic GCs from Schiavon (2005). The rough linear relation of positive slope, indicates that our spectrum is better fit by metal-rich than metal-poor GCs (see the text and next figure for details). Center, right: the same as left for two Galactic GCs from the same library, whose metallicity has been estimated with HR spectroscopy. As expected, the metal poor GC NGC 2298 correlates better with metal poor GCs while the metal rich GC NGC 6528 correlates best with metal rich GCs. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

|

Figure 6:

Left: Comparison between knot A's spectrum (continuous line) and the best

correlating GC from Schiavon (2005) (dashed line, cross correlation amplitude 9), which is the intermediate

metallicity GC NGC 6388. Right: the same as left with the worst correlating GC from

Schiavon et al. (2005) (cross correlation amplitude 4.5), which is NGC 1904. The two plots show that knot A's

spectrum correlates best with intermediate to high metallicity GCs like NGC 6388

(

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

|

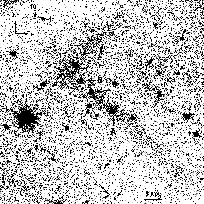

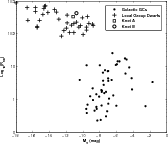

Figure 7: Absolute magnitudes vs half light radii for local group dwarfs from (Mateo 1998), Galactic globular clusters (Webbink 1985) and the two knots. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Table 3: Summary of measured and estimated (E) parameters for knots A & B.

3.3 Stellar population

The resolution of knot A's spectrum (

![]() Å at

5000 Å) is too low to accurately estimate metal abundances from

spectral line indices. An estimate of its metallicity would be nonetheless

useful to help constrain its nature.

Å at

5000 Å) is too low to accurately estimate metal abundances from

spectral line indices. An estimate of its metallicity would be nonetheless

useful to help constrain its nature.

In order to extract more information regarding knot A's stellar population, we cross-correlated its spectrum with that of 40 galactic GCs from the library in Schiavon et al. (2005), which covers a wide range of metallicities from -2 dex to solar abundance. We degraded the spectral resolution of the 40 galactic GCs to match that of knot A's spectrum, and used the IRAF task fxcor for cross-correlation.

With this method we find a linear relation between the cross correlation amplitudes of knot A (plus two test GCs) and the [Fe/H] ratios of the library's GCs (see Fig. 5). This is reasonable considering that for evolved stellar populations, the [Fe/H] ratio should play an important role in determining spectral differences. This implies that the [Fe/H] ratio of knot A can be estimated - at least qualitatively - using this cross correlation technique.

The results of the left panel of Fig. 5 imply an [Fe/H] ratio >-1.0 dex for knot A. The analogous plots in the middle and right panel for a metal-poor and a metal-rich GC confirm the validity of this approach, since the slope of the cross-correlation amplitude vs. [Fe/H] is, as expected, negative for the metal-poor and positive for the metal-rich GCs.

Figure 6 confirms the results of Fig. 5 by comparing knot A's spectrum with the two GCs with highest and lowest cross-correlation amplitudes. The match is very good for the GC NGC 6388, which is of intermediate metallicity ([Fe/H] = -0.7 dex), and shows a clear discrepancy for NGC 1904, which has a lower metallicity ([Fe/H] = -1.5 dex). Since NGC 6388 has an integrated spectral type of G2, while NGC 1904 has type F4/5 (Harris et al. 1996), we can state that the light emitted by knot A's is most likely dominated by G-type stars, in agreement with CAM.

While it is true that this method does not precisely determine the [Fe/H] ratio, the results shown in Figs. 5 and 6 indicate (at least qualitatively) that knot A's metal abundances are higher than LG dwarf spheroidals of similar luminosity (e.g., [Fe/H] = -1.5 dex; Mateo 1998). It has been shown however, that dSph galaxies belonging to different clusters of galaxies may show sensible differences in their metallicity-luminosity relation, if compared with LG dwarves (Lianou et al. 2010).

4 Discussion

4.1 Are the knots dwarf spheroidal galaxies?

We have shown that knot A's optical spectrum and total luminosity

matches well that of intermediate to metal rich and massive GCs like 47 Tucanae and

Mayall I. However, the size of knot A (

![]() pc) is abundantly

beyond those of ordinary GCs, the vast majority of which possess

pc) is abundantly

beyond those of ordinary GCs, the vast majority of which possess

![]() pc (cf. Mackey & van den Bergh 2005). In terms of

size both knots A & B are similar to LG dSph satellite galaxies of comparable

luminosity (Mateo 1998). It has been established that dSph galaxies and GCs occupy different

positions in a plot of half-light radius versus

pc (cf. Mackey & van den Bergh 2005). In terms of

size both knots A & B are similar to LG dSph satellite galaxies of comparable

luminosity (Mateo 1998). It has been established that dSph galaxies and GCs occupy different

positions in a plot of half-light radius versus ![]() .

Large GCs

in fact obey a well defined relation, in the sense that larger GCs are

also fainter (

.

Large GCs

in fact obey a well defined relation, in the sense that larger GCs are

also fainter (

![]() ;

Mackey & van den Bergh 2005; though Van den Bergh 2008 discusses shortcomings

of this diagnostic). Knots A & B are well above this line trend (they

are much larger for their optical luminosity than GCs) (see Fig. 7).

Instead, the knots agree very well with the

;

Mackey & van den Bergh 2005; though Van den Bergh 2008 discusses shortcomings

of this diagnostic). Knots A & B are well above this line trend (they

are much larger for their optical luminosity than GCs) (see Fig. 7).

Instead, the knots agree very well with the

![]() relation for LG

and Hydra/Centaurus dwarves (Misgeld et al. 2008, 2009).

They found that typical dSph galaxies follow the relation (cf. Misgeld et al. 2009):

relation for LG

and Hydra/Centaurus dwarves (Misgeld et al. 2008, 2009).

They found that typical dSph galaxies follow the relation (cf. Misgeld et al. 2009):

| (2) |

Substituting

In terms of stellar population (old GC-like stellar population with no signs of ongoing SF and a

peculiar lack of HI), stellar mass (

![]() for knot A and

for knot A and

![]() for knot B), central surface brightness and Sérsic

index (see above), Mv vs R50 (see Fig. 7) our knots closely resemble ordinary dSph

galaxies, as defined in Grebel et al. (2003) and Mateo (1998).

for knot B), central surface brightness and Sérsic

index (see above), Mv vs R50 (see Fig. 7) our knots closely resemble ordinary dSph

galaxies, as defined in Grebel et al. (2003) and Mateo (1998).

|

Figure 8:

Left: in this ehnanced version of Fig. 1 (3

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

4.2 Structure and composition of the stellar stream

The stellar stream itself was too faint for quantitative spectroscopy.

From our sky-substracted V-band exposure however (see Fig. 1), we could

measure the mean surface brightness of the stream (measured over ten different apertures a

long the ``dog-leg''). The value that we obtained is

![]() mag/arcsec2.

After measuring the mean SB of the stream using the standard IRAF tools, authors PG and SM

independently measured the size of the stream, by subdividing it in small rectangular apertures.

The value found is

mag/arcsec2.

After measuring the mean SB of the stream using the standard IRAF tools, authors PG and SM

independently measured the size of the stream, by subdividing it in small rectangular apertures.

The value found is

![]() arcsec2. From the measurement of the stream's mean surface

brightness and its area, we have calculated its integrated V magnitude to be

arcsec2. From the measurement of the stream's mean surface

brightness and its area, we have calculated its integrated V magnitude to be

![]() mag. At the distance of NGC 1097 this corresponds to an absolute

magnitude of

mag. At the distance of NGC 1097 this corresponds to an absolute

magnitude of

![]() mag.

mag.

Useful hints about the composition of the tidal stream can be found in earlier studies

(CAM, HW, Wehrle et al. 1997). Using multiband photometry of the tidal stream (obtained in a region

slightly south-western than knot A) CAM suggested that the SED of the ``dog-leg''

feature is compatible with G-type stars.

They also found that the colors of the stream and knot A are similar within

the photometric uncertainties (

![]() ,

,

![]() ).

This last point agrees with the conclusions of Wehrle et al. (1997).

In their paper they measured the B/V count ratio longitudinally and transversally

along the tidal stream (see their Fig. 8), and concluded:

``The color (along the tidal stream) is constant within the errors, including both prominent

condensations''.

Both studies came to the conclusion that the stellar stream is composed of stars near G-type,

and that the stream and the knots have the same color. With our FORS2 spectra, we independently

showed that also knot A is predominantly composed of stars near G-type. This suggests that the

knots and the tidal stream are both composed of the same stellar material.

).

This last point agrees with the conclusions of Wehrle et al. (1997).

In their paper they measured the B/V count ratio longitudinally and transversally

along the tidal stream (see their Fig. 8), and concluded:

``The color (along the tidal stream) is constant within the errors, including both prominent

condensations''.

Both studies came to the conclusion that the stellar stream is composed of stars near G-type,

and that the stream and the knots have the same color. With our FORS2 spectra, we independently

showed that also knot A is predominantly composed of stars near G-type. This suggests that the

knots and the tidal stream are both composed of the same stellar material.

A morphological analysis of the tidal stream indicates that knot A is currently being tidally stripped, populating the ``dog-leg'' tidal stream with stars. As shown in Fig. 8 (left), the tidal stream shows a slight but significant ``S'' shaped inflection coincident with the position of knot A. In Fig. 8 (right), we show moreover the elliptical overdensity of stars at knot A's position. These morphological features are typical for tidally disrupting systems (Forbes et al. 2003; Martínez-Delgado et al. 2008, 2010).

If knot A is the only progenitor of the stellar stream, before the encounter with NGC 1097, knot A

should have been a dwarf galaxy of at least

![]() mag. This means that knot A has lost

at least the 95% of its stars during the encounter with NGC 1097. This is in agreement with the n-body

simulations performed by HW.

mag. This means that knot A has lost

at least the 95% of its stars during the encounter with NGC 1097. This is in agreement with the n-body

simulations performed by HW.

4.3 How did the knots form?

The alignment of knots A & B with the ``dog-leg'' tidal stream suggests that these two objects are probably correlated in phase-space. Such a perfect alignment along the same stream would be in fact very unlikely for independently infalling CDM-Subhalos.

A possible explaination to the phase-space correlation problem of Milky Way satellites (Kroupa et al. 2005; Metz et al. 2009a), has been proposed in terms of a ``group infall'' of sub-halos (Li & Helmi 2008; D'Onghia & Lake 2008; D'Onghia et al. 2009). Alternately, dwarf galaxies may form along dark matter filaments (Ricotti et al. 2008). It is, however, still unclear if these mechanisms can efficiently explain the observed distribution of satellite galaxies around the Milky Way and Andromeda (for recent criticism see: Metz et al. 2009b,a).

The alignment of knots A & B with the stream is instead reminescent of the situation in the Milky Way, where the disk-of-satellites is approximately aligned with the Magellanic Stream (Metz et al. 2009b). This may suggest that the satellite galaxies of NGC 1097 may also be interpreted as being old tidal dwarf galaxies (Zwicky 1956; Lynden-Bell 1983; Okazaki & Taniguchi 2000).

However, a definitive interpretation awaits further study, in particular, we need to examine both knots' internal kinematics, and whether NGC 1097 has additional dSph satellite galaxies. The deep implications for fundamental physics of objects such as knots A & B being tidal dwarf galaxies are discussed in Kroupa et al. (2010).

5 Conclusions

We have shown that the two optical ``knots'' along NGC 1097's tidal stream share most of their observable properties with ordinary dwarf spheroidal galaxies (dSphs). From the measured redshifts we show that knot A (and very likely knot B) are associated with the tidal stream. The spectral light distribution of these dSphs is most consistent with that of intermediate to metal-rich Galactic GCs (see Figs. 6, 7).

These new observations set more stringent limits for H![]() emission of

the tidal stream, with EW

emission of

the tidal stream, with EW

![]() Å.

Å.

Our new observations, togheter with the results from former studies (Carter et al. 1984; Wehrle et al. 1997; Higdon & Wallin 2003), indicate that knot A is composed of the same stellar material as the tidal stream. Moreover, a morphological analysis of the tidal stream reveals clear signs of ongoing tidal stripping (see Fig. 8). Based on this evidence we conclude that very likely the stellar stream is populated by stars drawn out from knot A.

The presence of ongoing tidal stripping is incompatible with knot A being surrounded at present by a massive CDM halo (Peñarrubia et al. 2008, 2009).

AcknowledgementsWe wish to thank Halton C. Arp (MPA Garching) and Gero Rupprecht (ESO Garching), E.M. Burbidge and V. Jukkarinen (CASS San Diego) for their useful comments. We wish to extend a special word of thanks to Martino Romaniello (ESO Garching), Dieter Horns and Andrea Santangelo (IAAT Tuebingen) for their help during the preliminary stages of this paper.

References

- Arp, H. 1976, ApJ, 207L,147A [Google Scholar]

- Appenzeller, I., Fricke, K., Frütig, W., et al. 1998, The Messenger, 94, 1 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Bekki, K., Couch, W. J., Drinkwater, M. J., & Shioya, Y. 2003a, MNRAS, 344, 399 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bekki, K., Forbes, D. A., Beasley, M. A., & Couch, W. J. 2003b, MNRAS, 344, 1334 [Google Scholar]

- Bell, E. F., & de Jong, R. S. 2001, ApJ, 550, 212 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bruzual, G., & Charlot, S. 2003, MNRAS, 344, 1000B [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Carter, D., Allen, D. A., & Malin, D. F. 1984, MNRAS, 211, 707 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Capaccioli, M. 1987 in Structure and Dynamics of Elliptical Galaxies, ed. P. T. de Zeeuw (Dordrecht: Reidel), IAU Symp., 127, 47 [Google Scholar]

- Dekel, A., & Silk, J. 1986 ApJ, 303, 39 [Google Scholar]

- D'Onghia, E., & Lake, G. 2008, ApJ, 686, L61 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- D'Onghia, E., Besla, G., Cox, T. J., & Hernquist, L. 2009, Nature, 460, 605 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Duc, P. A., & Mirabel, I. F. 1994, A&A, 289, 83 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- de Vancouleurs, G. 1948, Ann. d'Astrophysique, 11, 247 [Google Scholar]

- de Vaucouleurs, G. 1959, Handb. Phys., 53, 275 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Drinkwater, M. J., Jones, J. B., Gregg, M. D., & Phillipps, S. 2000, PASA, 17, 227 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Faber, S. M., & Lin, D. N. C. 1983, ApJ, 266L, 17F [Google Scholar]

- Fellhauer, M., & Kroupa, P. 2002, MNRAS, 330, 642 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Fellhauer, M., & Kroupa, P. 2005, MNRAS, 359, 223 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes, D., Beasley, M. A., Bekki, K., Brodie, J. P., & Strader, J. 2003, Science, 301, 1217F [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Genzel, R. et al. 2006, Nature, 442, 17 [Google Scholar]

- Graham, A. W. 2001, AJ, 121, 820 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Graham, A. W., & Guzman, R. 2003, ApJ, 125, 2936 [Google Scholar]

- Gratton, R. G., et al. 2003, A&A, 408, 592 [Google Scholar]

- Grebel, E. K., Gallagher, J. S., III, & Harbeck, D. 2003, AJ, 125, 1926 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Harris, W. E. 1996, AJ, 112, 1487 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegan, M., Jordán, A., Côté, P., et al. 2005, ApJ, 627, 203 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbard, J. E., Guhathakurta, P., van Gorkom, J. H., & Schweizer, F. 1994, AJ, 107, 67 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Higdon, J. L., & Wallin, J. F. 2003, ApJ, 585, 281 (HW) [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Higdon, S. J., Higdon, J. L., & Marshall, J. 2006, ApJ, 640, 768 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hilker, M., Infante, L., & Richtler, T. 1999, A&AS, 138, 55 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Hilker, M., Infante, L., Vieira, G., Kissler-Patig, M., & Richtler, T. 1999, A&AS, 134, 75 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Hilker, M., Kissler-Patig, M., Richtler, T., Infante, L., & Quintana, H. 1999, A&AS, 134, 59 [Google Scholar]

- Kissler-Patig, M., Jordan, A., & Bastian, N. 2006, A&A, 448, 1031 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Koribalski, B., Staveley-Smith, L., Kilborn, V. A., et al. 2004, AJ, 128, 16 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kormendy, J., Fisher, D. B., Cornell, M. E., & Bender, R. 2009, ApJS, 182, 216 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kroupa, P. 1997, New Astron., 2, 139, 164 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kroupa, P., Theis, C., & Boily C. M. 2005, A&A, 2, 431, 517K [Google Scholar]

- Kroupa, P., et al. 2010, A&A, in press [Google Scholar]

- Lasker, B. M., Sturch, C. R., McLean, B. J., et al. 1990, AJ, 99, 2019 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lorre, J., J. 1978, ApJ, 222, 99 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y., & Helmi, A. 2008 MNRAS, 385, 1365 [Google Scholar]

- Lianou, S., Grebel, E. K., & Koch, A. 2010 A&A, in press [Google Scholar]

- Lynden-Bell, D., & Lynden-Bell, R. M. 1995, MNRAS, 275, 429 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Mackey, A. D., & van den Bergh, S. 2005, MNRAS, 360, 631 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Maraston, C., Bastian, N., Saglia, R. P., et al. 2004, A&A, 416, 467 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Delgado, D., Jay Gabany, R., Crawford, K., et al. 2010, ApJL, submitted [arXiv:1003.4860] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Delgado, D., Peñarrubia, J., Gabany, R. J., et al. 2008, ApJ, 689, 184M [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mateo, M. 1998, ARA&A, 435, 506 [Google Scholar]

- Mathewson, D., & Ford, V. 1996, ApJS, 107, 97 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Metz, M., & Kroupa, P. 2007 MNRAS, 376, 387 [Google Scholar]

- Metz, M., Kroupa, P., & Jerjen, H. 2009a, MNRAS, 394, 2223 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Metz, M., Kroupa, P., Theis, C., Hensler, G., & Jerjen, H. 2009b, ApJ, 697, 269 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Meylan, G., Mayor, M., Duquennoy, A., & Dubath, P. 1995, A&A, 303, 761 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Meylan, G., Sarajedini, A., Jablonka, P., et al. 2001, ApJ, 122, 830 [Google Scholar]

- Mieske, S., et al. 2006, ApJ, 131, 2242 [Google Scholar]

- Mirabel, I. F., Dottori, H., & Lutz, D. 1992, A&A, 256, L19 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Misgeld, I., Hilker, M., & Mieske, S. 2008, A&A, 486, 697 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Misgeld, I., Hilker, M., & Mieske, S. 2009, A&A, 496, 683 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Monet, D. G., Levine, S. E., Canzian, B., et al. 2003, AJ, 125, 984 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Meylan, G., & Mayor, M. 1986, A&A, 166, 122 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Okazaki, T., & Taniguchi, Y. 2000 ApJ, 543, 149 [Google Scholar]

- Patat, F. 2003, From twilight to highlight: the physics of Supernovae, ed. W. Hillebrandt, & B. Leibundgut (Springer), 321 [Google Scholar]

- Peñarrubia, J., McConnachie, A. W., & Navarro, J. F. 2008, ApJ, 673, 226 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Peñarrubia, J., Navarro, J. F., McConnachie, A. W., & Martin, N. F. 2009, ApJ, 698, 222 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, S., Drinkwater, M. J., Gregg, M. D., & Jones, J. B. 2001, ApJ, 560, 201 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Prieto, M., Maciejewski, W., & Reunanen, J. 2005, AJ, 130, 1472 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ricotti, M., Gnedin, N. Y., & Shull, J. M. 2008, ApJ, 685, 21 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Scarpa, R. 2006, unpublished [arXiv:astro-ph/0504051] [Google Scholar]

- Schweizer, F. 1982, ApJ, 252, 455 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Schiavon, R. P., Rose, J. A., Courteau, S., & MacArthur, L. A. 2005, ApJS, 160, 163 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sèrsic, J. L. 1968, Atlas de galaxias australes (Cordoba, Argentina: Observatorio Astronomico) [Google Scholar]

- Spergel, N. D., Verde, L., Peiris, H. V., et al. 2003, ApJS, 148, 175 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Storchi-Bergmann, T., Nemmen, R. S., Spinelli, P. F., et al. 2005, ApJ, 624, 13S [Google Scholar]

- Webbink, R. F. 1985, Dynamics of Star Clusters, ed. J. Goedman, & P. Hut, IAU Symp., 113, 541 [Google Scholar]

- Wehrle, A. E., Keel, W. C., & Jones, D. L. 1997, AJ, 114, 115 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Wolstencroft, R. D., Tully, R. B., & Perley, R. A. 1984, MNRAS, 207, 889 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Knierman, K. A., Gallagher, S. C., Charlton, J. C., et al. 2003, AJ, 126, 1227 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Vazdekis, A. 1999, ApJ, 513, 224 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Zwicky, F. 1956, Ergenisse Exakten Naturwissenschaften, 29, 344 [Google Scholar]

Footnotes

- ... stream

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- Based on observations made with ESO telescopes at Paranal Observatory in the observing program 66.B-0481 (G. Rupprecht/ H. Arp).

- ... feature

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- knots A & B referred to in this paper correspond to the two optical knots discussed in Wehrle et al. (1997). Our knot A is also the ``bright condensation'' in jet R1 discussed by CAM (see their Sect. 3 and Table 2).

- ... IRAF

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- IRAF is distributed by the National Optical Astronomy Observatories, which are operated by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy, under contract with the National Science Foundation.

All Tables

Table 1: Magnitudes of the observed objects: The labels fs, bg, c indicate respectively: ``foreground star'', ``backgroung galaxy'', ``condensation''. The typical rms errors for the magnitudes are 0.1 mag.

Table 2:

Absorption redshift of knot A:

![]() is the measured wavelength,

is the measured wavelength,

![]() is the rest-frame wavelength, z is the measured redshift and

is the rest-frame wavelength, z is the measured redshift and ![]() is

the redshift difference with NGC 1097 (z= 0.0042 NED).

is

the redshift difference with NGC 1097 (z= 0.0042 NED).

Table 3: Summary of measured and estimated (E) parameters for knots A & B.

All Figures

|

Figure 1:

FORS2/UT2 400 s Bessel V-band image of NGC 1097's northeast optical jet and ``dog-leg''.

The targets observed spectoscopically with FORS2 are labeled as in Table 1. The figure covers

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

|

Figure 2: Up left: FORS2 spectrum of knot A. Up right: FORS2 spectrum of knot B. Bottom: comparison of knot A's spectrum (blue line) vs. knot B's (red line). |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

|

Figure 3:

Closeups (

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

|

Figure 4:

Left: Knot A's surface brightness profile obtained with IRAF's

ellipse task. The continuos line represent the Sérsic n=0.6model fit. The dotted line delimits the seeing affected zone, while the

dash-dotted line is placed at

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

|

Figure 5: Left: Knot A's cross correlation amplitude as a function of metallicity for galactic GCs from Schiavon (2005). The rough linear relation of positive slope, indicates that our spectrum is better fit by metal-rich than metal-poor GCs (see the text and next figure for details). Center, right: the same as left for two Galactic GCs from the same library, whose metallicity has been estimated with HR spectroscopy. As expected, the metal poor GC NGC 2298 correlates better with metal poor GCs while the metal rich GC NGC 6528 correlates best with metal rich GCs. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

|

Figure 6:

Left: Comparison between knot A's spectrum (continuous line) and the best

correlating GC from Schiavon (2005) (dashed line, cross correlation amplitude 9), which is the intermediate

metallicity GC NGC 6388. Right: the same as left with the worst correlating GC from

Schiavon et al. (2005) (cross correlation amplitude 4.5), which is NGC 1904. The two plots show that knot A's

spectrum correlates best with intermediate to high metallicity GCs like NGC 6388

(

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

|

Figure 7: Absolute magnitudes vs half light radii for local group dwarfs from (Mateo 1998), Galactic globular clusters (Webbink 1985) and the two knots. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

|

Figure 8:

Left: in this ehnanced version of Fig. 1 (3

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

Copyright ESO 2010

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.