| Issue |

A&A

Volume 519, September 2010

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A115 | |

| Number of page(s) | 14 | |

| Section | Extragalactic astronomy | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201014559 | |

| Published online | 21 September 2010 | |

Mapping the ionised gas around the luminous QSO HE 1029-1401: evidence for minor merger events?![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

B. Husemann1 - S. F. Sánchez2,3,4 - L. Wisotzki1 - K. Jahnke5 - D. Kupko1 - D. Nugroho5 - M. Schramm1,6

1 - Astrophysikalisches Institut Potsdam, An der Sternwarte 16, 14482 Potsdam, Germany

2 -

Centro de Estudios de Física del Cosmos de Aragon (CEFCA), C/General Pizarro 1, 41001 Teruel, Spain

3 -

Fundación Agencia Aragonesa para la Investigación y el Desarrollo (ARAID), Spain

4 -

Centro Astronómico Hispano-Alemán, Calar Alto, (CSIC-MPG), C/Jesús Durbán Remón 2-2, 04004 Almeria, Spain

5 - Max-Planck-Institut für Astronomie, Königsstuhl 17, 69117 Heidelberg, Germany

6 -

Department of Astronomy, Kyoto University, Kyoto 606-8502, Japan

Received 30 March 2010 / Accepted 12 May 2010

Abstract

We present VIMOS integral field spectroscopy of the brightest

radio-quiet QSO on the southern sky HE 1029-1401 at a redshift of z=0.086.

Standard decomposition techniques for broad-band imaging are extended

to integral field data in order to deblend the QSO and host emission.

We perform a tentative analysis of the stellar continuum, finding a

young stellar population (<100 Myr) or a featureless continuum

embedded in an old stellar population (10 Gyr) typical for a

massive elliptical galaxy. The stellar velocity dispersion of

![]() km s-1 and the estimated black hole mass

km s-1 and the estimated black hole mass

![]() are consistent with the local

are consistent with the local

![]() -

-![]() relation within the errors. For the first time, we map the

two-dimensional ionised gas distribution and the gas velocity field

around HE 1029-1401. While the stellar host morphology is purely

elliptical, we find a highly structured distribution of ionised gas out

to 16 kpc from the QSO. The gas is highly ionised solely by the

QSO radiation and has a significantly lower metallicity than would be

expected for the stellar mass of the host, indicating an external

origin of the gas most likely due to minor mergers. We find a rotating

gas disc around the QSO and a dispersion-dominated non-rotating gas

component within the central 3 kpc. At larger distances the

velocity field is heavily disturbed, which could be interpreted as

another signature of past minor merger events. Alternatively, the

arc-like structure seen in the ionised gas might also be indicative of

a large-scale expanding bubble, centred on and possibly driven by the

active nucleus.

relation within the errors. For the first time, we map the

two-dimensional ionised gas distribution and the gas velocity field

around HE 1029-1401. While the stellar host morphology is purely

elliptical, we find a highly structured distribution of ionised gas out

to 16 kpc from the QSO. The gas is highly ionised solely by the

QSO radiation and has a significantly lower metallicity than would be

expected for the stellar mass of the host, indicating an external

origin of the gas most likely due to minor mergers. We find a rotating

gas disc around the QSO and a dispersion-dominated non-rotating gas

component within the central 3 kpc. At larger distances the

velocity field is heavily disturbed, which could be interpreted as

another signature of past minor merger events. Alternatively, the

arc-like structure seen in the ionised gas might also be indicative of

a large-scale expanding bubble, centred on and possibly driven by the

active nucleus.

Key words: galaxies: active - galaxies: ISM - quasars: emission lines - quasars: individual: HE 1029-1401

1 Introduction

Since the underlying host galaxies of several quasi-stellar objects (QSOs) were resolved by Kristian (1973), QSO host galaxies have been extensively studied to understand their properties and their relevance for the evolution of the overall galaxy population over cosmic time. Most of our knowledge of QSO host galaxies comes from numerous ground and space-based imaging studies (e.g. McLeod & Rieke 1994; Bahcall et al. 1997; Smith et al. 1986; Sánchez & González-Serrano 2003; Malkan 1984; Dunlop et al. 2003), which provide basic information on the host galaxies like the morphology or the luminosity. Narrow-band images centred on luminous emission lines have been used to infer the distribution and size of the ionised gas surrounding the QSO (e.g. Falcke et al. 1998; Schmitt et al. 2003; Stockton & MacKenty 1987; Bennert et al. 2002; Mulchaey et al. 1996). However, optical and/or near-infrared spectroscopy is required for a more detailed investigation of the properties of the stellar population and the ionised gas.

Boroson & Oke (1982) were the first to detect strong Balmer absorption lines in the off-nuclear spectrum of the QSO 3C 48 and highly ionised gas was already found long ago in off-nuclear spectra of many QSOs (e.g. Boroson et al. 1985; Stockton 1976; Wampler et al. 1975; Boroson & Oke 1984) indicating large amount of gas being photoionised by the QSO radiation. Unfortunately, spectroscopy of QSO hosts suffers invariably from the contamination of the spectrum by the emission of the active galactic nucleus (AGN) even when observed some arcseconds away from the nucleus. Various spectroscopic studies circumvented this problem by looking at obscured (type 2) AGN (e.g. González Delgado et al. 2001; Cid Fernandes et al. 2004; Bennert et al. 2006; Stoklasová et al. 2009; Kauffmann et al. 2003), which are thought to have the same properties as unobscured (type 1) AGN in the framework of the unification model of AGN (Urry & Padovani 1995; Antonucci 1993). They often find a young stellar population in the AGN host galaxies, in particular for the most luminous AGN, suggesting a connection between star formation and nuclear activity in agreement with photometric studies of type 1 QSOs at all redshifts (Jahnke et al. 2004a; Jahnke & Wisotzki 2003; Sánchez et al. 2004b; Jahnke et al. 2004b).

Letawe et al. (2007) and Jahnke et al. (2007), hereafter Let07 and Jah07 respectively, developed two different methods to decompose the AGN and host spectra in long-slit observations and applied them to a sample of luminous QSOs. However, long-slit spectroscopy covers only a small part of the host and depend on the chose position angle and slit width. Only integral field unit (IFU) observations allow to study the properties of the entire host galaxy in an unbiased way. Dedicated AGN-host decomposition techniques have already been developed and were successfully applied to IFU data of luminous QSOs at low and high redshift (Christensen et al. 2006; Husemann et al. 2008; Sánchez et al. 2004a).

In this paper, we report on optical IFU spectroscopy of the luminous radio-quiet QSO HE 1029-1401 with the VIMOS IFU at the Very Large Telescope (VLT). HE 1029-1401 was discovered by the Hamburg-ESO survey (HES; Wisotzki et al. 2000,1991) to be the brightest QSOs in the southern hemisphere with an apparent magnitude of V=13.7 at a redshift of only z=0.086.

Observations with the Hubble Space Telescope revealed a bright elliptical (E1) host galaxy (Bahcall et al. 1997) with an effective radius of

![]() (5.1 kpc). Jahnke et al. (2004a)

found from multi-colour imaging that the host colours are significantly

bluer than inactive galaxies at the same luminosity and inferred an

intermediate-age stellar population of 0.7 Gyr (luminosity

weighted) by modelling the Spectral Energy Distribution (SED) with

template Single Stellar Populations (SPPs).

(5.1 kpc). Jahnke et al. (2004a)

found from multi-colour imaging that the host colours are significantly

bluer than inactive galaxies at the same luminosity and inferred an

intermediate-age stellar population of 0.7 Gyr (luminosity

weighted) by modelling the Spectral Energy Distribution (SED) with

template Single Stellar Populations (SPPs).

Spatially resolved on-nuclear longslit spectroscopy for this object was presented by Let07 and Jah07. Both studies consistently found highly ionised gas in the host galaxy on kpc scales. Jah07 found that the stellar component is non-rotating, but the velocity curve of the ionised gas indicated the presence of a rotating gas disc on kpc scales around the nucleus. Let07 argued instead that the velocity curve does not fit with a pure rotational velocity field based on inclination arguments.

The main focus of this paper is to present an in-depth analysis of the

ionised gas in the host galaxy of HE 1029-1401, but we also

perform a tentative analysis of the stellar continuum. Throughout the

paper we assume a cosmological model with H0=70 km s-1,

![]() ,

and

,

and

![]() .

This corresponds to a physical scale of 1.6 kpc/

.

This corresponds to a physical scale of 1.6 kpc/

![]() at z=0.086.

at z=0.086.

2 Morphology of the host galaxy of HE 1029-1401

![\begin{figure}

\par\resizebox{9cm}{!}{\includegraphics[clip]{14559f1.eps}}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa14559-10/Timg23.png)

|

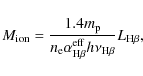

Figure 1: Nucleus-subtracted HST F606W broad-band image of the host galaxy of HE 1029-1401. Residuals of the diffraction spikes have been taken out by interpolation and the image is smoothed by a median filter (boxsize of 4 pixels) for display purposes. Three apparent nearby companion galaxies are labelled as C1, C2 and C3 of which only C3 is confirmed to be at a different redshift (Wisotzki 1994). The location of the two faint shells reported by Bahcall et al. (1997) are highlighted with arrows. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

A high resolution HST image of HE 1029-1401 in the F606W band was published by Bahcall et al. (1997).

We retrieved the archival HST image from the Hubble Legacy Archive![]() in order to re-analyse the image. An analytic point spread function

(PSF) for the observations was created with the TinyTim software

package (Krist 1995), because no sufficiently bright star was covered by the HST observation. We used GALFIT (Peng et al. 2002) to decompose the host and QSO contributions assuming a de Vaucouleurs light profile (de Vaucouleurs 1948) for the host plus a point source for the nucleus. The effective radius and ellipticity of our best-fitting model was

in order to re-analyse the image. An analytic point spread function

(PSF) for the observations was created with the TinyTim software

package (Krist 1995), because no sufficiently bright star was covered by the HST observation. We used GALFIT (Peng et al. 2002) to decompose the host and QSO contributions assuming a de Vaucouleurs light profile (de Vaucouleurs 1948) for the host plus a point source for the nucleus. The effective radius and ellipticity of our best-fitting model was

![]() (5.6 kpc) and e=0.1, respectively, which are consistent with the parameters derived by Bahcall et al. (1997).

(5.6 kpc) and e=0.1, respectively, which are consistent with the parameters derived by Bahcall et al. (1997).

The nucleus-subtracted image of HE 1029-1401 is shown in Fig. 1. A strong negative residual is still visible at the QSO position due to the saturated QSO core. We cleaned the image of residuals from the usual diffraction spikes by replacing each affected pixel with the median value of the unaffected pixels within a radius of 6 pixels. Wisotzki (1994) obtained redshifts for 13 galaxies in the field finding 4 physical companions which indicate that the HE 1029-1401 is part of a loose group of galaxies. None of these confirmed companions were covered with our IFU observations. Neither C1 nor C2 have redshift information available, but C3 was found to be at a different redshift than HE 1029-1401 (Wisotzki 1994).

Bahcall et al. (1997) also reported the detection of two faint shells located roughly 11

![]() and 19

and 19

![]() away from the nucleus. These shells are hardly visible in Fig. 1,

but we highlighted their position by arrows for guidance and labelled

them as S1 and S2, respectively. Note that the shell S2 is outside

the field-of-view of our IFU observations.

away from the nucleus. These shells are hardly visible in Fig. 1,

but we highlighted their position by arrows for guidance and labelled

them as S1 and S2, respectively. Note that the shell S2 is outside

the field-of-view of our IFU observations.

We also performed an isophotal analysis of the host using the ellipse task of IRAF![]() (Tody 1993)

after masking the 2 closest apparent companions. As the image is

strongly affected by decomposition residuals over the central 2

(Tody 1993)

after masking the 2 closest apparent companions. As the image is

strongly affected by decomposition residuals over the central 2

![]() ,

we only took into account isophotes within a range of 2

,

we only took into account isophotes within a range of 2

![]() -10

-10

![]() in the semi-major axis. We found that the ellipticity of the host is slightly decreasing outwards from 0.2-0.1 and that the a4/a Fourier coefficient is consistent with 0. Thus, the deviation from pure elliptical isophotes is marginal.

in the semi-major axis. We found that the ellipticity of the host is slightly decreasing outwards from 0.2-0.1 and that the a4/a Fourier coefficient is consistent with 0. Thus, the deviation from pure elliptical isophotes is marginal.

3 IFU observations and data reduction

We employed the IFU mode of the VIMOS instrument (LeFevre et al. 2003)

on the VLT to perform optical 3D spectroscopy of

HE 1029-1401. The observations were conducted on the 18th and 24th

of December 2003 at a seeing of ![]()

![]() ,

with the high-resolution blue and orange grisms covering the spectral regions around H

,

with the high-resolution blue and orange grisms covering the spectral regions around H![]() and H

and H![]() with a spectral resolution of

with a spectral resolution of ![]() .

We chose a spatial resolution of 0.66

.

We chose a spatial resolution of 0.66

![]() /fibre resulting in a field-of-view of

/fibre resulting in a field-of-view of

![]() that matches well with the angular size of the QSO host galaxy. The exposure times were split into

that matches well with the angular size of the QSO host galaxy. The exposure times were split into

![]() s for the blue and

s for the blue and

![]() s

for the orange grism. A dither pattern was used in order to correct for

dead fibres within the field-of-view. Additionally, a blank sky

exposure of 300 s was obtained in between the target exposure

series. Arc lamp and continuum lamp exposures were acquired for each

configuration directly after the target exposures for calibration

purposes. Standard star exposures were taken for each night according

to the instrumental setup.

s

for the orange grism. A dither pattern was used in order to correct for

dead fibres within the field-of-view. Additionally, a blank sky

exposure of 300 s was obtained in between the target exposure

series. Arc lamp and continuum lamp exposures were acquired for each

configuration directly after the target exposures for calibration

purposes. Standard star exposures were taken for each night according

to the instrumental setup.

The VIMOS instrument is a complex IFU with 1600 operating fibres in the high-resolution mode. These are split up into 4 bundles of 400 fibres densely projected onto each of the 4 spectrograph CCDs. Instrument flexure and cross-talk between adjacent fibres are important issues for VIMOS which need to be carefully taken into account in the data reduction. As this is not the case for the standard reduction pipeline provided by ESO, we used our own flexible reduction package R3D (Sánchez 2006) designed to reduce fibre-fed IFU raw data, complemented by custom Python scripts. The basic reduction steps performed with R3D include: Bias subtraction, visually checked fibre identification, fibre tracing, spectra extraction, wavelength calibration, fibre flatfielding and flux calibration.

Flexure of the instrument causes substantial shifts of the fibre traces in the cross-dispersion direction between the continuum lamp exposure and the science exposure. This is a severe problem for an accurate extraction of the science spectra. We measured the fibre trace positions in the individual science exposures and continuum lamp exposure by modelling the cross-dispersion profile at 5 different locations on the dispersion axis with multiple Gaussians. The cross-dispersion profiles were generated by co-adding 200 pixels in the dispersion direction, preferentially encompassing bright sky lines, to increase the S/N. The offset between the science and continuum lamp fibre traces were measured to be in the range of -2.5 to 2.5 pixels. 2nd order Chebychev polynomials were used to extrapolate the offsets to the whole dispersion axis range.

In order to reduce the effect of cross-talk we used an

iterative and fast algorithm that is part of the R3D package, based on

Gaussian profile fitting to each of the fibres in the cross-dispersion

direction. The centroids were fixed for each fibre to the position on

the continuum lamp taking into account the position offsets due to the

flexure. The width of the Gaussians was fixed. Details of the spectra

extraction algorithm can be found in the R3D user guide![]() .

The width of the fibre profiles is different for each of the four CCDs

as it depends on the optical calibration of the four independent VIMOS

spectrograph units. Thus, we estimated the fibre dispersion separately

for each unit by simultaneously fitting each fibre with a Gaussian

profile in the cross-dispersion direction at a single dispersion

position for each CCD.

.

The width of the fibre profiles is different for each of the four CCDs

as it depends on the optical calibration of the four independent VIMOS

spectrograph units. Thus, we estimated the fibre dispersion separately

for each unit by simultaneously fitting each fibre with a Gaussian

profile in the cross-dispersion direction at a single dispersion

position for each CCD.

The continuum lamp exposure was used to create a fibreflat that corrects for the differences in the fibre-to-fibre transmission. Sky subtraction and the correction for the differential atmospheric refraction were done with custom Python scripts. Taking advantage of the dithered exposures we were able to increase the spatial sampling by a factor of 2 and to correct for dead fibres within the field-of-view. The flux calibrated datacubes were rescaled in flux to match with the QSO V-band photometry and corrected for Galactic extinction applying the Cardelli et al. (1989) extinction curve with an extinction of AV = 0.221 (Schlegel et al. 1998) in the sightline to HE 1029-1401.

4 IFU decomposition of host and QSO emission

In order to study the emission from the stars and the gas in the host of HE 1029-1401 it is important to properly subtract the contribution of the bright QSO. Broad-band imaging studies of QSO hosts have successfully used a two-dimensional analytical modelling scheme to decompose the point-like nucleus and different spatial extended host components to study the properties of QSO host galaxies (e.g. Jahnke et al. 2009; McLure et al. 1999; Kim et al. 2008; Sánchez et al. 2004b; Kuhlbrodt et al. 2004). We have extended this method to model each monochromatic image of an IFU datacube in order to obtain the clean optical spectrum of the radio jet of 3C 120 (García-Lorenzo et al. 2005; Sánchez et al. 2006,2004a) and to deblend the components of a gravitationally lensed quasar (Wisotzki et al. 2003).

![\begin{figure}

\par\resizebox{9cm}{!}{\includegraphics[clip]{14559f2.eps}}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa14559-10/Timg30.png)

|

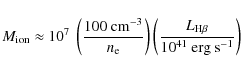

Figure 2: Result of the decomposition process for HE 1029-1401. The integrated spectrum and the decomposed QSO and host spectra are shown in the top panel. A zoomed version on the host spectrum is provided in the bottom panel. The red points indicate the host magnitudes in the V and R band measured by (Jahnke et al. 2004a). They are offset by 0.5 mag to put them on the same absolute scale as the IFU photometry. All spectra have been smoothed with a median filter of 7 pixels for display purposes. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Broad-band imaging studies usually estimate the PSF empirically from stacked images of stars within the field-of-view. The field-of-view of current IFU instruments is generally too small so that no star can generally be captured simultaneously with the target. In light of time variable seeing, the QSO itself therefore needs to be used to construct a PSF. Fortunately, the spectral shape of the QSO is, in the absence of atmospheric dispersion, exactly the same in each spatial pixel of the IFU, only scaled by a factor according to the PSF. In particular, the broad emission lines of type 1 QSOs are a unique feature of the point like nucleus, which can be used to empirically estimate a PSF for IFU data (Jahnke et al. 2004c).

Having obtained a PSF for the IFU data from the broad emission lines and the morphological parameters of the host inferred from the HST images, we proceeded to model each monochromatic IFU narrow-band image by a linear combination of the PSF and host model. In this way we reconstructed a pure QSO and host datacube containing the QSO and mean host spectrum. Afterwards, we subtracted the QSO datacube from the observed one to obtain a datacube uncontaminated by the QSO. The result of this decomposition process for HE 1029-1401 is presented in Fig. 2.

We found the IFU spectrum of the QSO and host component to be of higher

quality than the long-slit spectra presented by Let07. The stellar

absorption lines around MgI

![]() are

clearly visible in our host spectrum, and the noise in the spectrum is

greatly reduced compared to the long-slit spectrum, due to the much

larger galaxy area captured. IFU spectroscopy improves the quality of

the decomposition due to the large spatial coverage of almost the

entire host galaxy and the on-source PSF estimation based on QSO

features. The decomposition of the long-slit spectra particularly

suffered as the only available PSF star near HE 1029-1401 is

2 mag fainter than the QSO (Let07).

are

clearly visible in our host spectrum, and the noise in the spectrum is

greatly reduced compared to the long-slit spectrum, due to the much

larger galaxy area captured. IFU spectroscopy improves the quality of

the decomposition due to the large spatial coverage of almost the

entire host galaxy and the on-source PSF estimation based on QSO

features. The decomposition of the long-slit spectra particularly

suffered as the only available PSF star near HE 1029-1401 is

2 mag fainter than the QSO (Let07).

5 Analysis

5.1 The host spectrum and stellar velocity dispersion

![\begin{figure}

\par\resizebox{9cm}{!}{\includegraphics[clip]{14559f3.eps}}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa14559-10/Timg32.png)

|

Figure 3: Host spectrum of

HE 1029-1401 in the rest-frame wavelength between 5100 and

5400 Å. The best-fitting model spectrum is overplotted as the red

solid line. Note that the strong residual of the bright [O I] 5577 night sky emission line appearing at |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Comparing the V and R band apparent magnitudes reported by Jahnke et al. (2004a)

with the magnitudes inferred from our host spectrum, we found a

constant offset of 0.5 mag in both bands. This difference can be

easily explained by the brightness variability of the QSO as we matched

the overall IFU photometry to the archival magnitude of the QSO

with a difference in observation time of several years. Note that our

measured V-R colour in the observed frame of 0.36 mag is consistent with the V-R broad-band colour of

![]() mag measured by Jahnke et al. (2004a).

mag measured by Jahnke et al. (2004a).

While we found consistent colours with the previous broad-band study,

we noticed a steep increase in the blue part of the total host

spectrum. This feature is even more pronounced for the host spectra

within 1.5

![]() around

the nucleus. Whether this blue part of the spectrum originates from a

young stellar population around the nucleus, or from scattered QSO

light due to circumnuclear dust (e.g. Antonucci & Miller 1985; Zakamska et al. 2005),

or whether it is an artifact of a systematic PSF mismatch in the

decomposition process in that spectral region, we are currently unable

to say. However, we do resolve the strong absorption lines around

MgI

around

the nucleus. Whether this blue part of the spectrum originates from a

young stellar population around the nucleus, or from scattered QSO

light due to circumnuclear dust (e.g. Antonucci & Miller 1985; Zakamska et al. 2005),

or whether it is an artifact of a systematic PSF mismatch in the

decomposition process in that spectral region, we are currently unable

to say. However, we do resolve the strong absorption lines around

MgI

![]() even at the low level of signal as shown in Fig. 3, so the stellar component has a significant contribution to the continuum emission.

even at the low level of signal as shown in Fig. 3, so the stellar component has a significant contribution to the continuum emission.

We modelled the integrated host spectrum excluding the central 1.5

![]() with a linear combination of high spectral resolution SSP spectra employing the STARLIGHT spectral synthesis code (Cid Fernandes et al. 2005; Mateus et al. 2006). The SSP spectra with a spectral sampling of 0.3 Åwere generated with the Sed@ code

with a linear combination of high spectral resolution SSP spectra employing the STARLIGHT spectral synthesis code (Cid Fernandes et al. 2005; Mateus et al. 2006). The SSP spectra with a spectral sampling of 0.3 Åwere generated with the Sed@ code![]() as presented in González Delgado et al. (2005) with the following inputs: initial mass function from Salpeter (1955) in the mass range 0.1-120

as presented in González Delgado et al. (2005) with the following inputs: initial mass function from Salpeter (1955) in the mass range 0.1-120 ![]() ;

the high resolution library from Martins et al. (2005) based on atmosphere models from PHOENIX (Allard et al. 2001; Hauschildt & Baron 1999), ATLAS9 (Kurucz 1991) computed with SPECTRUM (Gray & Corbally 1994) and the ATLAS9 library computed with TLUSTY (Lanz & Hubeny 2003).

Our input grid contains 39 SSP spectra with ages of

1, 3, 5, 10, 25, 40, 100, 300, 600, 900, 2000, 5000

and 10 000 Myr and metallicities of 0.004, 0.02 and

0.04 Z.

;

the high resolution library from Martins et al. (2005) based on atmosphere models from PHOENIX (Allard et al. 2001; Hauschildt & Baron 1999), ATLAS9 (Kurucz 1991) computed with SPECTRUM (Gray & Corbally 1994) and the ATLAS9 library computed with TLUSTY (Lanz & Hubeny 2003).

Our input grid contains 39 SSP spectra with ages of

1, 3, 5, 10, 25, 40, 100, 300, 600, 900, 2000, 5000

and 10 000 Myr and metallicities of 0.004, 0.02 and

0.04 Z.

Monte Carlo simulations were used to determine the errors of the best-fit parameters, the flux-weighted stellar age

![]() and metallicity

and metallicity

![]() at a normalisation wavelength of

at a normalisation wavelength of

![]() Å, the extinction (AV) and the stellar velocity dispersion (

Å, the extinction (AV) and the stellar velocity dispersion (![]() ).

We generated 200 mock spectra of the host on the basis of the

observed host spectrum combined with its wavelength dependent noise

budget. These 200 artificial host spectra were analysed with STARLIGHT

exactly as the observed host spectrum itself. Finally, a linear

combination of only 5-7 SSP spectra was sufficient for modelling

all spectra. The other SSP base spectra of the grid were discarded from

the modelling in the first iteration by STARLIGHT as their total

contribution to the flux density at the normalisation wavelength were

less then 2%. The resulting parameters were

).

We generated 200 mock spectra of the host on the basis of the

observed host spectrum combined with its wavelength dependent noise

budget. These 200 artificial host spectra were analysed with STARLIGHT

exactly as the observed host spectrum itself. Finally, a linear

combination of only 5-7 SSP spectra was sufficient for modelling

all spectra. The other SSP base spectra of the grid were discarded from

the modelling in the first iteration by STARLIGHT as their total

contribution to the flux density at the normalisation wavelength were

less then 2%. The resulting parameters were

![]() Gyr,

Gyr,

![]() ,

,

![]() and

and

![]() km s-1 (corrected for the instrumental resolution of

km s-1 (corrected for the instrumental resolution of ![]() 42 km s-1).

We repeated the same analysis excluding the blue part of the host

spectrum (3800-4700 Å rest-frame wavelength) and arrived at

consistent results within the errors. To our knowledge this is the

first time that

42 km s-1).

We repeated the same analysis excluding the blue part of the host

spectrum (3800-4700 Å rest-frame wavelength) and arrived at

consistent results within the errors. To our knowledge this is the

first time that ![]() was estimated for the host galaxy of such a luminous QSO. Jahnke et al. (2004a) derived a younger stellar population with 0.7-2 Gyr based on SSP modeling of the VRIJHK

multi-colour spectral energy distribution. A direct comparison with our

result needs to be taken with caution due to the completely different

analysis method used to infer the characteristic age of the stellar

population. However, we note that the distribution of stellar

populations that contribute to the composite spectrum is clearly

bimodal and consists of a young stellar population with ages

<100 Myr (

was estimated for the host galaxy of such a luminous QSO. Jahnke et al. (2004a) derived a younger stellar population with 0.7-2 Gyr based on SSP modeling of the VRIJHK

multi-colour spectral energy distribution. A direct comparison with our

result needs to be taken with caution due to the completely different

analysis method used to infer the characteristic age of the stellar

population. However, we note that the distribution of stellar

populations that contribute to the composite spectrum is clearly

bimodal and consists of a young stellar population with ages

<100 Myr (![]() of the total flux at

of the total flux at ![]() )

in addition to an old stellar population with 10 Gyr age (

)

in addition to an old stellar population with 10 Gyr age (![]() of the total flux at

of the total flux at ![]() ).

This indicates the presence of a young stellar component if the main

contribution to the blue continuum of the spectrum is of stellar origin

and not due to a featureless continuum that can hardly be distinguished

from such a young stellar component (e.g Storchi-Bergmann et al. 2000).

).

This indicates the presence of a young stellar component if the main

contribution to the blue continuum of the spectrum is of stellar origin

and not due to a featureless continuum that can hardly be distinguished

from such a young stellar component (e.g Storchi-Bergmann et al. 2000).

5.2 The QSO spectrum

![\begin{figure}

\par\resizebox{9cm}{!}{\includegraphics[clip]{14559f4.eps}}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa14559-10/Timg44.png)

|

Figure 4:

Multi-component fit to the H |

| Open with DEXTER | |

The top panel of Fig. 2

shows the QSO spectrum of HE 1029-1401 in the full wavelength

range covered by our observations. We now focus on the analysis of the H![]() -[O III]

region using a multi-component fitting scheme to deblend the various

emission lines in this spectral region. Our model consists of several

Gaussian components and a simple linear relation to approximate the

local continuum. The best-fit model to the spectrum and its individual

components are shown in Fig. 4.

-[O III]

region using a multi-component fitting scheme to deblend the various

emission lines in this spectral region. Our model consists of several

Gaussian components and a simple linear relation to approximate the

local continuum. The best-fit model to the spectrum and its individual

components are shown in Fig. 4.

The H![]() line exhibits an asymmetric line profile with enhanced emission on its

red wing, which can be well described by a redshifted Gaussian

component. From the model we measured a line width of the broad H

line exhibits an asymmetric line profile with enhanced emission on its

red wing, which can be well described by a redshifted Gaussian

component. From the model we measured a line width of the broad H![]() line of

line of

![]() km s-1 (FWHM) and

km s-1 (FWHM) and

![]() km s-1 (

km s-1 (![]() ). Furthermore, the [O III] line profile is asymmetric to the blue side requiring a second Gaussian component. The two [O III] components are separated by

). Furthermore, the [O III] line profile is asymmetric to the blue side requiring a second Gaussian component. The two [O III] components are separated by

![]() km s-1 in rest-frame and have FWHM values of

km s-1 in rest-frame and have FWHM values of

![]() km s-1 and

km s-1 and

![]() km s-1,

respectively. Additionally, a third extremely broad and blueshifted

component is required to reach an acceptable fit. We are not sure

whether this component is physical, representing a true extension of

the asymmetric [O III] line profile, or whether it should be rather attributed to the complex and asymmetric line profile of the H

km s-1,

respectively. Additionally, a third extremely broad and blueshifted

component is required to reach an acceptable fit. We are not sure

whether this component is physical, representing a true extension of

the asymmetric [O III] line profile, or whether it should be rather attributed to the complex and asymmetric line profile of the H![]() line. The continuum flux density at 5100 Å (rest-frame) is

line. The continuum flux density at 5100 Å (rest-frame) is

![]() corresponding to a luminosity of

corresponding to a luminosity of

![]() .

.

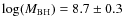

With these measurements we estimated a black-hole mass from the single

epoch QSO spectrum using the virial method. This calculation is based

on the empirical relation between the broad-line region radius and the

continuum luminosity at 5100 Å calibrated by Bentz et al. (2006), and the prescription by Collin et al. (2006) to infer the velocity of the broad line clouds from the H![]() line dispersion adopting a scale factor of 3.85. This yields a black hole mass of

line dispersion adopting a scale factor of 3.85. This yields a black hole mass of

![]() for HE 1029-1401. The measurement errors for the black hole mass

are much smaller in this case than the systematic errors of the method,

thus we adopted a canonical error of 0.3 dex. Assuming the

for HE 1029-1401. The measurement errors for the black hole mass

are much smaller in this case than the systematic errors of the method,

thus we adopted a canonical error of 0.3 dex. Assuming the

![]() -

-![]() relation of Tremaine et al. (2002) our measured stellar velocity dispersion

relation of Tremaine et al. (2002) our measured stellar velocity dispersion ![]() predicts a black hole mass of

predicts a black hole mass of

![]() ,

which is perfectly consistent with our virial black hole mass estimate.

,

which is perfectly consistent with our virial black hole mass estimate.

![\begin{figure}

\par\resizebox{9cm}{!}{\includegraphics[clip]{14559f5.eps}}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa14559-10/Timg55.png)

|

Figure 5:

Nucleus-subtracted continuum-free [O III]

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[height=16cm,clip]{14559f6.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa14559-10/Timg56.png)

|

Figure 6: [O III] channel maps created from monochromatic datacube slices corresponding to rest-frame radial velocities of -269.4, -180.1, -90.8, -31.2, +38.3, +87.9, +177.2, +266.5 km s-1, respectively. The main distinct emission line regions are labelled alphabetically from A to G and the red boxes indicate regions that were co-added to obtain their characteristic spectrum (Fig. 7). The position of the QSO is marked in each map by the green cross. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Adopting a bolometric correction of L

![]() (Kaspi et al. 2000), we estimated a bolometric luminosity of

(Kaspi et al. 2000), we estimated a bolometric luminosity of

![]() and an Eddington ratio of

and an Eddington ratio of

![]() for the QSO.

for the QSO.

5.3 Ionised gas distribution and channel maps

In Fig. 5 we present an [O III]

![]() (hereafter [O III]) narrow-band image (

(hereafter [O III]) narrow-band image (![]() bandwidth) extracted from the datacube after subtracting the QSO

contribution. Continuum emission from the host galaxy was previously

subtracted to obtain a pure emission-line image. This is the first

two-dimensional map of the ionised gas distribution around

HE 1029-1401.

bandwidth) extracted from the datacube after subtracting the QSO

contribution. Continuum emission from the host galaxy was previously

subtracted to obtain a pure emission-line image. This is the first

two-dimensional map of the ionised gas distribution around

HE 1029-1401.

The image reveals ionised gas on scales of several kpcs. We find a highly structured distribution of the ionised gas. The brightest structure is a symmetric circumnuclear bicone suggestive of an ionisation cone by the QSO. Furthermore, we detect ionised gas in several knots and arms and in a faint giant arc-like feature north-west to the galaxy centre at a projected distance of 16 kpc. Most of the distinct emission-line regions are well located inside the visible light distribution of the early-type host galaxy when compared with the HST image in Fig. 1. The prominent bicone-like structure is roughly aligned with the major axis of the host galaxy, although the orientation of the latter is not well constrained due to the low ellipticity of the host.

The integrated extended [O III] line flux is

![]() corresponding to an [O III] luminosity of

corresponding to an [O III] luminosity of

![]() .

This is one of the most luminous extended emission-line regions (EELRs)

around a radio-quiet QSO compared to other radio-quiet ones, e.g. in

the sample of Stockton & MacKenty (1987).

.

This is one of the most luminous extended emission-line regions (EELRs)

around a radio-quiet QSO compared to other radio-quiet ones, e.g. in

the sample of Stockton & MacKenty (1987).

In Fig. 6 we present [O III]

channel maps corresponding to monochromatic images at specific radial

velocities with respect to the rest-frame of the objects. In this way

we can identify low-surface brightness emission-line regions that are

relatively faint in the integrated line image or that spatially overlap

but are separated in velocity space. The main emission line regions are

labelled alphabetically from A to G and their characteristic spectra

were obtained by co-adding several spatial pixels within the boundary

indicated by the red boxes. These regions are a symmetric bicone-like

structure around the nucleus (regions C and G), two arm-like

structures (regions D and E), two emission-line knots

(regions B and F) and part of the giant arc-like feature ![]() 16 kpc north-west of the nucleus (region A). We excluded the central

16 kpc north-west of the nucleus (region A). We excluded the central ![]() 1

1

![]() region around the QSO from these spectra because of significant residuals of the QSO subtraction.

region around the QSO from these spectra because of significant residuals of the QSO subtraction.

5.4 Spectral analysis of specific regions

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[height=22cm,clip]{14559f7.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa14559-10/Timg63.png)

|

Figure 7:

Co-added spectra of the regions A-G (as defined in Fig. 6) are shown from top to bottom split up into two wavelength ranges bracketing H |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Co-added spectra of the regions A-G as defined in the previous subsection are shown in Fig. 7. These were split up into two narrow wavelength ranges bracketing the H![]() and H

and H![]() emission lines. No signatures of the broad emission lines of the QSO

are visible in any of the extracted spectra after the spectral

decomposition. The H

emission lines. No signatures of the broad emission lines of the QSO

are visible in any of the extracted spectra after the spectral

decomposition. The H![]() ,

[O III]

,

[O III]

![]() ,

H

,

H![]() and [N II]

and [N II]

![]() emission lines are clearly detected in most of the selected regions. The [S II]

emission lines are clearly detected in most of the selected regions. The [S II]

![]() emission lines are only visible in the spectra of region C and G.

emission lines are only visible in the spectra of region C and G.

We modelled each spectrum with Gaussian profiles for the emission lines

and scaled the best-fitting stellar population spectrum (cf. Sect. 5.1)

to the continuum. We found that stellar absorption lines have no

significant effect on the Balmer emission line. The flux ratio of the

[O III] and [N II] doublets were fixed

to their theoretical values and all emission lines were kinematically

coupled to have the same redshift and line dispersion. We utilised

Monte Carlo simulations to estimate realistic errors for all free fit

parameters. 100 mock spectra were generated for each spectrum according

to the noise of the spectrum as estimated from the adjacent continuum.

These mock spectra were consistently analysed and the standard

deviation of the resulting distribution for each fitted parameter was

taken as its 1![]() error. A 3

error. A 3![]() upper limit is given for the flux of the H

upper limit is given for the flux of the H![]() line in region A as it falls below the detection limit. The measured emission line fluxes are given in Table 1.

line in region A as it falls below the detection limit. The measured emission line fluxes are given in Table 1.

Table 1:

Emission line fluxes for the H![]() ,

[O III]

,

[O III]

![]() ,

H

,

H![]() ,

[N II]

,

[N II]

![]() and the [S II]

and the [S II]

![]() lines as measured from Gaussian fits to the spectra of the region A to G.

lines as measured from Gaussian fits to the spectra of the region A to G.

We noticed that all emission lines in the spectrum of region G display an asymmetric line profile. A two component Gaussian model for each line provided an excellent fit to the data. The appearance of a second system of kinematically distinct emission-line in region G will be further analysed later in Sect. 6.4.

6 Results

6.1 Source of ionisation and gas metallicity

To infer the dominant ionisation source for the gas we employ the commonly used emission-line ratio diagnostic diagram [O III]

![]() /H

/H![]() vs. [N II]

vs. [N II]

![]() /H

/H![]() (Baldwin et al. 1981; Veilleux & Osterbrock 1987).

The diagram distinguishes gas being ionised by the hard UV radiation

field of an AGN from gas ionised by radiation from hot stars in star

forming H II regions. A theoretically motivated and conservative boundary between both mechanisms was derived by Kewley et al. (2001). The diagnostic diagram is shown in Fig. 8 for the emission-line ratios inferred from the spectra of region A-G.

(Baldwin et al. 1981; Veilleux & Osterbrock 1987).

The diagram distinguishes gas being ionised by the hard UV radiation

field of an AGN from gas ionised by radiation from hot stars in star

forming H II regions. A theoretically motivated and conservative boundary between both mechanisms was derived by Kewley et al. (2001). The diagnostic diagram is shown in Fig. 8 for the emission-line ratios inferred from the spectra of region A-G.

We found that photoionisation by star forming regions can be excluded

for all regions as the inferred line ratios are above the Kewley

et al. demarcation curve. Of course, this does not imply there is

no current star formation in the host, only that AGN ionisation of the

ISM dominates strongly over any other ionisation mechanisms. We can

also exclude shock ionisation based on the kinematics and the

emission-line ratios. The line ratios for the broad shocked gas

components in powerful radio galaxies are observed to have a much lower

ionisation state with [O III]/H![]()

![]() 2-4 (e.g. Villar-Martín et al. 1999) than observed here. Furthermore, shock-ionisation models (Dopita & Sutherland 1995; Allen et al. 2008) indicate that an [O III]/H

2-4 (e.g. Villar-Martín et al. 1999) than observed here. Furthermore, shock-ionisation models (Dopita & Sutherland 1995; Allen et al. 2008) indicate that an [O III]/H![]() line ratio around 10 would require shock velocities >500 km s-1 for which we find no evidence in our observations (cf. Sect. 6.3). Thus, photoionisation by the central QSO is the dominant ionisation mechanism for the gas in HE 1029-1401 at least within a radius of 16 kpc around the nucleus.

line ratio around 10 would require shock velocities >500 km s-1 for which we find no evidence in our observations (cf. Sect. 6.3). Thus, photoionisation by the central QSO is the dominant ionisation mechanism for the gas in HE 1029-1401 at least within a radius of 16 kpc around the nucleus.

In order to infer the metallicity of the gas we compared the

emission-line ratios with the dusty radiation pressure-dominated

photoionisation models by Groves et al. (2004). These models are represented by red tracks in Fig. 8 corresponding to gas-phase metallicities of

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

,

![]() and

and

![]() assuming an electron density of

assuming an electron density of

![]() for the emitting clouds and a power-law index

for the emitting clouds and a power-law index

![]() for the ionising QSO continuum. The line ratios do not strongly depend

on the electron density, so we chose the model grid with the lowest

density close to the estimated value as discussed in the next section.

Note that the true metallicities of the photoionisation models are a

factor of 2 higher than the gas-phase metallicities, since half of

the overall metal content is depleted into dust in the models. The

comparison with the photoionisation models revealed that the

emission-line ratios follow quite closely the model with a solar

metallicity. Only the gas in region B appears to have a systematically

different ionisation state and/or metallicity.

for the ionising QSO continuum. The line ratios do not strongly depend

on the electron density, so we chose the model grid with the lowest

density close to the estimated value as discussed in the next section.

Note that the true metallicities of the photoionisation models are a

factor of 2 higher than the gas-phase metallicities, since half of

the overall metal content is depleted into dust in the models. The

comparison with the photoionisation models revealed that the

emission-line ratios follow quite closely the model with a solar

metallicity. Only the gas in region B appears to have a systematically

different ionisation state and/or metallicity.

![\begin{figure}

\par\resizebox{9cm}{!}{\includegraphics[clip]{14559f8.eps}}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa14559-10/Timg115.png)

|

Figure 8:

Diagnostic diagram for the emission-line ratios of the regions A-G

in HE 1029-1401. The narrow emission-line ratios are indicated by

black circles and the broad component in region G is indicated by

the black opened circle. The commonly used demarcation curve between

AGN and H II regions by Kewley et al. (2001) is indicated as the black solid line. Dusty radiation pressure-dominated photoionisation models (Groves et al. 2004) are indicated by the red tracks for four gas-phase metallicities with

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=5.5cm,height=4.5cm,clip]{14559f9a.eps}...

...degraphics[width=6.5cm,height=4.5cm,clip]{14559f9b.eps}\vspace{3mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa14559-10/Timg116.png)

|

Figure 9:

Left panel: [O III] velocity map of HE 1029-1401 with respect to its estimated systemic velocity (25 670 km s-1). The two black lines correspond to position angles of |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=5.5cm,height=4.5cm,clip]{14559f10a.eps}\includegraphics[width=6.5cm,height=4.5cm,clip]{14559f10b.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa14559-10/Timg117.png)

|

Figure 10: Same as Fig. 9, but for the [O III] velocity dispersion, corrected for the spectral resolution of the instrument. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

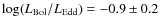

6.2 Total ionised gas mass

To estimate the total ionised gas mass in HE 1029-1401 we followed the prescription and assumptions of Osterbrock & Ferland (2006). By measuring the luminosity of the H![]() recombination line one can estimate the ionised gas mass

recombination line one can estimate the ionised gas mass

![]() using the following formula:

using the following formula:

where

|

(2) |

In our case we were able to measure the electron density sensitive [S II]

Since the narrow H![]() line is the weakest in all of the spectra, we used the [O III] emission line as a surrogate for the H

line is the weakest in all of the spectra, we used the [O III] emission line as a surrogate for the H![]() emission assuming a line ratio of

emission assuming a line ratio of

![]() (cf. Fig. 8). With the integrated

(cf. Fig. 8). With the integrated

![]() line luminosity measured from the [O III] narrow-band image (cf. Sect. 5.3) and our adopted electron density, we estimated an ionised gas mass of

line luminosity measured from the [O III] narrow-band image (cf. Sect. 5.3) and our adopted electron density, we estimated an ionised gas mass of

![]() .

Note that we did not take reddening due to dust in the host galaxy into account, which would increase

.

Note that we did not take reddening due to dust in the host galaxy into account, which would increase

![]() and hence the ionised gas mass. Our inferred ionised gas mass should be

taken as a rough estimate due to the various assumptions needed and can

only be used at an order-of-magnitude level.

and hence the ionised gas mass. Our inferred ionised gas mass should be

taken as a rough estimate due to the various assumptions needed and can

only be used at an order-of-magnitude level.

6.3 Global gas kinematics

In order to obtain full 2D velocity and velocity dispersion maps of the ionised gas we fitted the [O III]

doublet lines as they are the brightest emission lines in all of the

individual 6400 spectra of the nucleus-subtracted datacube. The

measured emission-line centroids were converted into radial velocities

with respect to the systemic redshift for each spatial pixel to

construct a 2D velocity map (Fig. 9 left panel). A different visualisation of the velocity field are ``long-slit'' velocity curves (Fig. 9 right panel) extracted from our velocity map for the position angles (PAs) ![]() and

and ![]() .

We chose these two PAs such that one shows the velocity curve of the

bi-cone structure and the other to cross the arm-like feature.

Similarly, we present a 2D [O III] velocity dispersion map (Fig. 10 left panel), corrected for the spectral resolution of the instrument, and the corresponding ``long-slit'' curves (Fig. 10

right panel). The gaps in the velocity and dispersion curves around the

circumnuclear region are due to the strong residuals of the

decomposition process which prevent a reliable measurement of the

extended emission lines.

.

We chose these two PAs such that one shows the velocity curve of the

bi-cone structure and the other to cross the arm-like feature.

Similarly, we present a 2D [O III] velocity dispersion map (Fig. 10 left panel), corrected for the spectral resolution of the instrument, and the corresponding ``long-slit'' curves (Fig. 10

right panel). The gaps in the velocity and dispersion curves around the

circumnuclear region are due to the strong residuals of the

decomposition process which prevent a reliable measurement of the

extended emission lines.

The 2D kinematic information from our IFU data draws a much clearer

picture than previous long-slit studies of this object. While the [O III] velocity curve at a PA of 25![]() appears like a symmetric rotation curve up to 5

appears like a symmetric rotation curve up to 5

![]() from the galaxy centre, it is highly disturbed at larger distances. At a PA of

from the galaxy centre, it is highly disturbed at larger distances. At a PA of ![]() the velocity curve crosses the arm-like structure detected in the [O III] flux distribution which clearly breaks the symmetry seen at a PA of

the velocity curve crosses the arm-like structure detected in the [O III] flux distribution which clearly breaks the symmetry seen at a PA of ![]() .

We measured a maximum amplitude of

.

We measured a maximum amplitude of ![]() 170 km s-1 for the radial velocities at a distance of 4.8 kpc (

170 km s-1 for the radial velocities at a distance of 4.8 kpc (

![]() )

from the nucleus, which is consistent with the measurements by Let07

and Jah07 based on long-slit spectroscopy only. However, the long-slit

velocity curve presented by Let07 covers only

)

from the nucleus, which is consistent with the measurements by Let07

and Jah07 based on long-slit spectroscopy only. However, the long-slit

velocity curve presented by Let07 covers only ![]()

![]() which is less than half of the region we studied with our IFU data.

Therefore, they miss the turnover of the velocity curve at 4

which is less than half of the region we studied with our IFU data.

Therefore, they miss the turnover of the velocity curve at 4

![]() -6

-6

![]() from

the nucleus. Another major kinematic component is the prominent

distortion in the rotational velocity field on the West side of the

nucleus, which was missed by the long-slit data of Let07 and Jah07.

from

the nucleus. Another major kinematic component is the prominent

distortion in the rotational velocity field on the West side of the

nucleus, which was missed by the long-slit data of Let07 and Jah07.

The measured velocity dispersion (![]() )

of the gas after correcting for the instrumental resolution is

)

of the gas after correcting for the instrumental resolution is ![]() 30 km s-1 on the red- and

30 km s-1 on the red- and ![]() 40 km s-1 on the blue-shifted side of the velocity curve. On both sides the

40 km s-1 on the blue-shifted side of the velocity curve. On both sides the ![]() ratio

is significantly greater than 1, which indicates rotational support of

the gas in a disc. This is consistent with the conclusion of Jah07. The

velocity dispersion increases significantly up to

ratio

is significantly greater than 1, which indicates rotational support of

the gas in a disc. This is consistent with the conclusion of Jah07. The

velocity dispersion increases significantly up to ![]() 80 km s-1

between the region of the gas disc and the major kinematic distortion

on the West side. This is most probably related to the superposition of

the two kinematic components as we find asymmetric and double-peaked

emission-lines in this particular region. In the circumnuclear region

the velocity dispersion rises steeply towards the centre. We will study

the kinematics of this region in greater detail in the next section.

80 km s-1

between the region of the gas disc and the major kinematic distortion

on the West side. This is most probably related to the superposition of

the two kinematic components as we find asymmetric and double-peaked

emission-lines in this particular region. In the circumnuclear region

the velocity dispersion rises steeply towards the centre. We will study

the kinematics of this region in greater detail in the next section.

![\begin{figure}

\par\resizebox{9cm}{!}{\includegraphics[clip]{14559f11a.eps}}\par\resizebox{9cm}{!}{\includegraphics[clip]{14559f11b.eps}}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa14559-10/Timg138.png)

|

Figure 11:

Detailed modelling of the emission lines in the spectrum of region G. The emission lines around H |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=18cm,clip]{14559f12.eps} %

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa14559-10/Timg139.png)

|

Figure 12: Distribution and kinematics of two kinematically distinct emission line components. The flux distribution ( left), radial velocity ( middle) and velocity dispersion ( right) are shown for the narrow emission line in the top panels and in the bottom panels for the broad component. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

6.4 Gaseous kinematics in the inner 3 kpc

As previously mentioned in Sect. 5.4, a two component model for the emission lines was required to model the spectrum of region G. We present the model for that spectrum and the individual emission-line components in Fig. 11. All the strong emission lines are clearly asymmetric and a second broader Gaussian component is needed to match this asymmetry. Furthermore, we found that all emission lines share the same kinematics and were therefore kinematically coupled in the model. We inferred a velocity dispersion of 45 km s-1 for the narrow and 110 km s-1 for the broad component.

From the spatially resolved kinematics assuming only a single Gaussian

for the emission line, we note that the velocity dispersion is rising

close to the centre. This suggests that the broad component is also

spatially resolved. Thus, we modelled each spectrum of the datacube

with a two-component Gaussian model for the [O III] doublet emission line. We employed the statistical F-test on the ![]() values for the two models to decide weather the two component model is

a statistically significant better representation of the spectrum than

a single component model. The resulting maps of the flux distribution,

radial velocity and velocity dispersion for the narrow and broad

components are shown in Fig. 12.

values for the two models to decide weather the two component model is

a statistically significant better representation of the spectrum than

a single component model. The resulting maps of the flux distribution,

radial velocity and velocity dispersion for the narrow and broad

components are shown in Fig. 12.

These maps reveal that the narrow component originates from

rotationally supported gas without a major increase in the velocity

dispersion as close as 1 kpc to the QSO. The broad component, on

the other hand, is almost non-rotating with a velocity gradient of only

![]() 40 km s-1 compared to

40 km s-1 compared to ![]() 120 km s-1

of the rotating gas in the same region. The spatially resolved velocity

dispersion of the gas in the broad component were measured to be in the

range of

120 km s-1

of the rotating gas in the same region. The spatially resolved velocity

dispersion of the gas in the broad component were measured to be in the

range of

![]() km s-1 in agreement with the velocity dispersion inferred from the integrated spectrum of region G. Because

km s-1 in agreement with the velocity dispersion inferred from the integrated spectrum of region G. Because ![]() is greater than 1 for the broad component, this gas seems to be

dispersion dominated and mainly supported by random motion. We also

detected the broad component on the blueshifted side of the rotating

gas coincident with region C, which is hardly noticeable in the

integrated spectrum of that region as the flux in the broad component

is much lower than the flux in region G. This dispersion dominated gas

component in the circumnuclear region was not detectable in the

previous studies by Let07 and Jah07 due to the lower spectral

resolution.

is greater than 1 for the broad component, this gas seems to be

dispersion dominated and mainly supported by random motion. We also

detected the broad component on the blueshifted side of the rotating

gas coincident with region C, which is hardly noticeable in the

integrated spectrum of that region as the flux in the broad component

is much lower than the flux in region G. This dispersion dominated gas

component in the circumnuclear region was not detectable in the

previous studies by Let07 and Jah07 due to the lower spectral

resolution.

6.5 Surface brightness profiles and apparent neighbouring galaxies

We measured the radial surface brightness profiles of the stellar continuum emission as seen by HST and of the [O III] line emission from the VIMOS data using circular annuli. To account for the biconical structure of the [O III] light distribution we also computed surface brightness profiles within a ![]() wide

cone along the major and minor axis. Due to the low spatial resolution

of the VIMOS date we took the subpixel coverage of the annuli and cones

into account. Since the ratio of [O III] to H

wide

cone along the major and minor axis. Due to the low spatial resolution

of the VIMOS date we took the subpixel coverage of the annuli and cones

into account. Since the ratio of [O III] to H![]() is constant of

is constant of ![]() 10 for the entire galaxy, it is reasonable to assume that the [O III] light distribution is a tracer of the ionised gas distribution. The profiles are compared in Fig. 13 after the HST surface brightness was scaled to match the total [O III] surface brightness in the radial distance range from 7.5

10 for the entire galaxy, it is reasonable to assume that the [O III] light distribution is a tracer of the ionised gas distribution. The profiles are compared in Fig. 13 after the HST surface brightness was scaled to match the total [O III] surface brightness in the radial distance range from 7.5

![]() to 9

to 9

![]() .

.

Surprisingly, the surface brightness profile of the total ionised gas apparently follows that of the stars on a global scale despite the morphological difference. However, the profiles are significantly different for the light distribution in the cones along the major and minor axis. The drop in the [O III] surface brightness along the minor axis is steep with a power-law index of -1.8. This is roughly consistent with the geometrical decrease in the ionising photon density that scales as r-2. On the other hand, the profile along the major axis is much shallower also with respect to the stars indicating that the radial ionised gas distribution is determined by the gas density rather than the amount of available ionising photons in this direction. The distinct [O III] emission line knots and arcs as identified in the [O III] narrow-band image and channel maps (cf. Fig. 5 and Fig. 6) produce excesses in the total [O III] surface brightness profile and along the major axis at around 5 kpc, 10 kpc and 16 kpc radial distance as expected. We do not detect any corresponding features in the continuum surface brightness profile. The stellar surface brightness profile itself is rather smooth except for the bright apparent companion C1 located 4 arcsec away from the host centre, but we do not find any significant excess in the [O III] surface brightness at that location neither in the major nor the minor axis cone.

![\begin{figure}

\par\resizebox{9cm}{!}{\includegraphics[clip]{14559f13.eps}}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa14559-10/Timg143.png)

|

Figure 13:

Radial surface brightness profiles of the stellar continuum (solid

line) compared with the total ionised gas distribution (dashed line),

the ionised gas within a |

| Open with DEXTER | |

We consider two explanations for the lack of ionised gas at the location of the bright apparent neighbouring galaxy C1 north to the nucleus: 1.) The galaxy is not a physical companion so its gas cannot be ionised by the QSO. 2.) The galaxy is a physical companion with an intrinsically low amount of gas to be ionised.

The relation of the second faint galaxy to the host galaxy of HE 1029-1401 remains unclear. We detected weak [O III] emission at its position which corresponds to one end of the large arc-like structure seen at a distance of 10

![]() .

It is possible that gas is stripped off from the faint companion while

it is orbiting around the host galaxy forming a tail of gas that is

partially illuminated by the QSO radiation. Since redshift information

is not available for this galaxy, a simple projection effect is also a

reasonable explanation.

.

It is possible that gas is stripped off from the faint companion while

it is orbiting around the host galaxy forming a tail of gas that is

partially illuminated by the QSO radiation. Since redshift information

is not available for this galaxy, a simple projection effect is also a

reasonable explanation.

7 Discussion

7.1 The unexpected anisotropic AGN radiation field

The biconical distribution of the ionised gas in the circumnuclear region of HE 1029-1401 appears to be very similar to the ionisation cones detected in several nearby Seyfert galaxies (e.g. Storchi-Bergmann & Bonatto 1991; Pogge 1988b,a; Storchi-Bergmann et al. 1992). These collimated AGN radiation cones are supporting the unified model for AGN in which the nucleus is thought to be surrounded by a dusty torus providing a partial obscuration of the AGN. This model explains the distinction between type 1 and type 2 AGN solely by the orientation of the obscuring torus with respect to the observers line-of-sight. In this picture, the opening angle of the ionisation cones is simply determined by the covering factor of the torus.

Why is such an anisotropic radiation field on kpc scales

unexpected for a luminous type 1 QSO like HE 1029-1401?

Firstly, ionisation cones are best seen if they are oriented

perpendicular to our line-of-sight, which means that the torus is

oriented almost edge-on and the AGN is obscured. This is the reason why

most of the known ionisation cones were detected in Seyfert 2

galaxies. Secondly, the ``receding torus'' model (Lawrence 1991)

predicts the opening angle of the AGN ionisation cones to increase with

the AGN luminosity, which is observationally supported by the

decreasing fraction of obscured AGN with increasing luminosity in X-ray

selected AGN samples (e.g. Hasinger 2008; Ueda et al. 2003; Hasinger 2004). The X-ray 2-10 keV luminosity of HE 1029-1401 is

![]() (Reeves & Turner 2000, converted to a concordance cosmology) corresponding to a type 2 fraction of

(Reeves & Turner 2000, converted to a concordance cosmology) corresponding to a type 2 fraction of ![]() 30% (Hasinger 2008). From this fraction one would expect a large opening angle of

30% (Hasinger 2008). From this fraction one would expect a large opening angle of ![]() 115

115![]() ,

much more than what our observations suggest.

,

much more than what our observations suggest.

Mulchaey et al. (1996) simulated the apparent emission-line images of the ionisation cones assuming that the ambient gas distribution is a spheroid or disc. They found that for a spheroidal gas distribution the emission-line image may have a V-shape morphology but the apparent opening angle is always equal or greater than the opening angle of the ionisation cones. Due to the rotational motion of the gas, our observations indicate that the gas is more likely to be distributed in a disc rather than in a sphere. In that case, the apparent opening angle from the emission-line images is always smaller than the opening angle of the ionisation cones depending on the angle between the disc and cone axis. If the ionisation cones is oriented such that it intercepts the disc almost at its edge, the apparent opening angle would be much smaller and consistent with our observations. Thus, the morphology of the emission-line gas around HE 1029-1401 can be consistent with the expectation of the unifed model of AGN if the ambient gas is distributed in a disc combined with a certain configuration of the AGN ionisation cones with respect to the disc.

7.2 The origin of the gas

We inferred from our IFU data that the elliptical host of HE 1029-1401 contains ionised gas with a mass of the order of

![]() .

The ionised gas mass is rather small compared to the stellar mass of the system that has been measured to be

.

The ionised gas mass is rather small compared to the stellar mass of the system that has been measured to be

![]() based on broad-band SED modelling (Schramm, private communication).

Unfortunately, the neutral gas fraction of HE 1029-1401 is

unknown. Thus, it is unclear if HE 1029-1401 contains more gas

than comparable inactive early-type galaxies, or whether the luminous

QSO is just able to ionise a significant fraction of the neutral gas

content.

based on broad-band SED modelling (Schramm, private communication).

Unfortunately, the neutral gas fraction of HE 1029-1401 is

unknown. Thus, it is unclear if HE 1029-1401 contains more gas

than comparable inactive early-type galaxies, or whether the luminous

QSO is just able to ionise a significant fraction of the neutral gas

content.

But where did the gas come from? Our emission-line diagnostic

analysis showed that the metallicity of the gas is close to solar. We

now compare this with the mass-metallicity relation of star-forming

galaxies as presented by Tremonti et al. (2004). As the mass-metallicity relation depends critically on the assumed metallicity estimator (Kewley et al. 2006), the Tremonti et al. (2004) relation best matches with our metallicity estimation as it is also based on the CLOUDY photoionisation code (Ferland 1996). What we find is that the expected value for the oxygen abundance for a galaxy with a stellar mass of

![]() is

is

![]() .

This is more than 0.3 dex larger than the solar oxygen abundance

measured for HE 1029-1409. Although the scatter in the

mass-metallicity relation is non-negligible, the metallicity of the gas

in HE 1029-1409 would correspond to a >3

.

This is more than 0.3 dex larger than the solar oxygen abundance

measured for HE 1029-1409. Although the scatter in the

mass-metallicity relation is non-negligible, the metallicity of the gas

in HE 1029-1409 would correspond to a >3![]() deviation from the Tremonti et al. (2004) mass-metallicity relation at a stellar mass of

deviation from the Tremonti et al. (2004) mass-metallicity relation at a stellar mass of

![]() .

.

Peeples et al. (2009) and Alonso et al. (2010)

recently showed that the high-mass low-metallicity outliners of the

mass-metallicity relation are morphologically disturbed galaxies with

bluer colours (or younger stellar populations) suggesting an inflow of

low-metallicity gas driven by galaxy interactions and accompanied by

enhanced star formation. This is consistent with the observations of

HE 1029-1401, but the signatures for galaxy interactions are weak

with only the faint shells detected by Bahcall et al. (1997).

The high stellar mass and smooth surface brightness profile of the host

suggest that the last major merger that formed the elliptical galaxy

happened at a much earlier epoch. Assuming that the gas originates

entirely from a single progenitor galaxy, the solar gas phase

metallicity would correspond to a stellar mass of roughly

![]() almost 10 times smaller than the host mass of HE 1029-1401

itself. This is consistent with the picture that ionised gas originates

from one or a few minor companions that merged with HE 1029-1401.

Therefore, we favour to interpret the low metallicity of the ionised

gas in HE 1029-1401 as a clear indication for an external origin of the gas via the infall of one or a few minor companions.

almost 10 times smaller than the host mass of HE 1029-1401

itself. This is consistent with the picture that ionised gas originates

from one or a few minor companions that merged with HE 1029-1401.

Therefore, we favour to interpret the low metallicity of the ionised

gas in HE 1029-1401 as a clear indication for an external origin of the gas via the infall of one or a few minor companions.

Similar results have been obtained for the EELRs around the radio-loud QSOs 4C 37.43 (Fu & Stockton 2007) and 3C 79 (Fu & Stockton 2008).

The authors found in both of these cases a solar to sub-solar

metallicity of the ionised gas on kpc scales around their massive

elliptical host galaxies containing black holes with a mass of the

order of

![]() .

They also came to the conclusion that the metal-poor gas needs to have an external origin.

.

They also came to the conclusion that the metal-poor gas needs to have an external origin.

7.3 The kinematics of the ionised gas - Indications for mergers or AGN outflow?

The [O III] emission-line profile in the nuclear spectrum is asymmetric, which we resolved into two distinct Gaussian components with a FWHM of

![]() km s-1 and

km s-1 and

![]() km s-1, respectively, where the broader component is blueshifted by

km s-1, respectively, where the broader component is blueshifted by ![]() km s-1. Such asymmetric [O III] lines have been previously reported in many other QSOs (e.g. Véron-Cetty et al. 2001; Heckman et al. 1981) and were interpreted as an indication for high ionisation outflows from the nucleus (Zamanov & Marziani 2002). We can not spatially resolve the extended ionised gas closer than

km s-1. Such asymmetric [O III] lines have been previously reported in many other QSOs (e.g. Véron-Cetty et al. 2001; Heckman et al. 1981) and were interpreted as an indication for high ionisation outflows from the nucleus (Zamanov & Marziani 2002). We can not spatially resolve the extended ionised gas closer than ![]() 1 kpc

from the nucleus, but outside this unresolved region we did not find

any signatures for a similarly broad and blueshifted ionised gas

component indicating that this possibly outflowing component is

restricted to scales below

1 kpc

from the nucleus, but outside this unresolved region we did not find

any signatures for a similarly broad and blueshifted ionised gas

component indicating that this possibly outflowing component is

restricted to scales below ![]() 1 kpc.

1 kpc.

Instead, we find that the majority of the extended ionised gas appears to be bound in a rotationally supported gas disc. The lack of rotational motion in the corresponding stellar component as inferred by Jah07 further supports an external origin of the gas from a kinematically point of view. The non-rotating dispersion-dominated ionised gas within the central 3 kpc could either represent an intrinsic reservoir of gas originating from the stars in the host or gas that is directly heated by the AGN.