| Issue |

A&A

Volume 519, September 2010

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A86 | |

| Number of page(s) | 8 | |

| Section | Interstellar and circumstellar matter | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201014031 | |

| Published online | 16 September 2010 | |

Search for broad absorption lines in spectra of stars in the field of supernova remnant RX J0852.0-4622 (Vela Jr.)

A. F. Iyudin1,2 - Yu. V. Pakhomov3 - N. N. Chugai3 - J. Greiner1 - M. Axelsson4 - S. Larsson4 - T. A. Ryabchikova3

1 - Max-Planck-Institut für extraterrestrische Physik, Postfach 1312, 85741

Garching, Germany

2 -

Skobeltsyn Institute of Nuclear Physics, Moscow State University,

Vorob'evy Gory, 119992 Moscow, Russian Federation

3 - Institute of Astronomy, RAS, Pyatnitskaya 48, 119017, Moscow, Russian Federation

4 -

Stockholm University, AlbaNova University Center, Department of Astronomy,

106 91 Stockholm, Sweden

Received 9 January 2010 / Accepted 24 May 2010

Abstract

Aims. Supernova remnant (SNR) RX J0852.0-4622 is one of the

youngest and is most likely the closest among known Galactic SNRs. It

was detected in X-rays, the 44Ti ![]() -line,

and radio. We obtain and analyze medium-resolution spectra of 14 stars

in the direction towards the SNR RX J0852.0-4622 in an attempt to

detect broad absorption lines of unshocked ejecta against background

stars.

-line,

and radio. We obtain and analyze medium-resolution spectra of 14 stars

in the direction towards the SNR RX J0852.0-4622 in an attempt to

detect broad absorption lines of unshocked ejecta against background

stars.

Methods. Spectral synthesis is performed for all the stars in

the wavelength range of 3740-4020 Å to extract the broad

absorption lines of Ca II related to the SNR RX J0852.0-4622.

Results. We do not detect any broad absorption line and place a 3![]() upper limit on the relative depths of <0.04 for the broad

Ca II absorption produced by the SNR. We detect narrow low

and high velocity absorption components of Ca II. High velocity

upper limit on the relative depths of <0.04 for the broad

Ca II absorption produced by the SNR. We detect narrow low

and high velocity absorption components of Ca II. High velocity

![]() km s-1

components are attributed to radiative shocks in clouds engulfed by the

old Vela SNR. The upper limit to the absorption line strength combined

with the width and flux of the 44Ti

km s-1

components are attributed to radiative shocks in clouds engulfed by the

old Vela SNR. The upper limit to the absorption line strength combined

with the width and flux of the 44Ti ![]() -ray

line 1.16 MeV lead us to conclude that SNR RX J0852.0-4622

was probably produced by an energetic SN Ic explosion.

-ray

line 1.16 MeV lead us to conclude that SNR RX J0852.0-4622

was probably produced by an energetic SN Ic explosion.

Key words: line: formation - stars: fundamental parameters - stars: distances - ISM: supernova remnants - supernovae: general - supernova: individual: RX J0852.0-4622

1 Introduction

Young supernova remnants (SNRs) at the deceleration stage generally provide us with an opportunity to probe the supernova (SN) ejecta not yet polluted by the circumstellar matter (CSM). The ejecta composition and structure are usually studied by analyzing the X-ray spectra emanating from the reverse shock. In some young SNRs related to core-collapse SNe, e.g., Cas A, the optical emission of undecelerated ejecta clumps are observed when they penetrate the post-shock layer, in which case they are powered by slow radiative shocks. Unshocked ejecta material is cold and does not radiate, thus remaining invisible in emission.

However, in rare cases the unshocked ejecta of SNR can be observed in resonance absorption lines against a background light source seen through the SNR shell. Among Galactic SNR, this method has been applied successfully only to SN 1006, where the ejecta was observed in the ultraviolet absorption lines against the spectra of hot stars and QSOs (Winkler et al. 2005; Hamilton et al. 1997,2007). There is also one extragalactic SNR detected in absorption lines: the remnant of SN 1885 in M 31. It was first detected by ground-based imaging in Fe I 3860 Å band against the M 31 bulge (Fesen et al. 1989) and afterwards by HST imaging and spectroscopy (Fesen et al. 1999). The optical spectrum of this SNR contains strong Fe I, Ca II, and Ca I broad resonance absorption lines produced by the unshocked ejecta.

Table 1: List of the observed stars.

RX J0852.0-4622 (Vela Jr., G266.2-1.2) is a young galactic SNR detected by means of its emission in hard

X-rays (Aschenbach 1998), the 44Ti 1.16 MeV ![]() -ray

line (Iyudin et al. 1998), radio (Duncan & Green 2000), and TeV

-ray

line (Iyudin et al. 1998), radio (Duncan & Green 2000), and TeV

![]() -rays (Aharonian et al. 2005). Vela Jr. with a

diameter of

-rays (Aharonian et al. 2005). Vela Jr. with a

diameter of ![]()

![]() is superimposed on the eastern part of the well-known old

Vela SNR. The age and distance of Vela Jr. are estimated to

is superimposed on the eastern part of the well-known old

Vela SNR. The age and distance of Vela Jr. are estimated to ![]() yr

and

yr

and ![]() 200 pc, respectively (Aschenbach et al. 1999; Bamba et al. 2005).

The age, distance, and angular radius imply an average expansion velocity of

200 pc, respectively (Aschenbach et al. 1999; Bamba et al. 2005).

The age, distance, and angular radius imply an average expansion velocity of

![]() 5000 km s-1.

5000 km s-1.

Using XMM-Newton

images, Katsuda et al. (2008) measured the proper motion of the bright NW rim of RX J0852.0-4622.

The derived value turns out to be about 5 times lower than the predicted

average expansion rate of Vela Jr. On the basis of the measured proper motion,

Katsuda et al. (2008)

estimate the age of Vela Jr. to be 1700-4300 years and its

distance to be ![]() 750 pc. Although the conclusion could be hampered by a

possible interaction with the recently encountered dense interstellar medium,

the possibility of a large age cannot presently be fully ruled out.

750 pc. Although the conclusion could be hampered by a

possible interaction with the recently encountered dense interstellar medium,

the possibility of a large age cannot presently be fully ruled out.

Given the uncertainty in the age issue, we should carefully study the implications of a young age. In this respect, it is tempting to consider the unshocked ejecta of Vela Jr. using absorption spectroscopy against background stars. Our preliminary estimates showed that broad Ca II absorption lines might be observed. Here we report results of spectral observations and analysis of the spectra of distant stars across the Vela Jr. In Sect. 2, we describe the observations and data reduction. The results of the spectral synthesis and extraction of broad and interstellar Ca II absorption are presented in Sect. 3. We fail identify any broad absorption lines and the implications of this are discussed in Sect. 4.

2 Observations and data reduction

Spectra were obtained on the ESO 3.6-m telescope NTT

(program 080.D-0012(A) PI: A.F. Iyudin) using the echelle spectrograph EMMI in

BLMD mode of medium-dispersion spectroscopy with holographic grating #11

(3000 grooves/mm and maximum light reflectivity at

![]() Å).

The dispersion is 0.15 Å/pix, the resolving power is

Å).

The dispersion is 0.15 Å/pix, the resolving power is

![]() for a slit width of 1.02'' and a registered

wavelength band of

for a slit width of 1.02'' and a registered

wavelength band of ![]() 1500 Å. The signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) is between 90

and 350. For each star, two overlapped spectra in the range of 3740-4021 Å

were obtained with centers at 3820 Å and 3945 Å. This spectral

region encompasses resonance spectral lines of Fe I (3860 Å) and Ca II

(3933 Å, 3968 Å).

1500 Å. The signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) is between 90

and 350. For each star, two overlapped spectra in the range of 3740-4021 Å

were obtained with centers at 3820 Å and 3945 Å. This spectral

region encompasses resonance spectral lines of Fe I (3860 Å) and Ca II

(3933 Å, 3968 Å).

Among the observed stars, ten are of B-type and four of A-type (Table 1)

with magnitudes

![]() .

Table 1 contains

the star number, star HD/CD name, right ascension, declination, V-magnitude,

spectral type, B-V color index, relative impact parameter p, and

signal-to-noise ratio (S/N), and 1

.

Table 1 contains

the star number, star HD/CD name, right ascension, declination, V-magnitude,

spectral type, B-V color index, relative impact parameter p, and

signal-to-noise ratio (S/N), and 1![]() ,

which represents the root mean square error

in the spectral fit (see Sect. 3). The impact parameter is defined as

,

which represents the root mean square error

in the spectral fit (see Sect. 3). The impact parameter is defined as

![]() ,

where

,

where ![]() is the angular distance of the star from the SNR

center and

is the angular distance of the star from the SNR

center and

![]() is the SNR angular radius. The SNR center presumably

coincides with the neutron star candidate AX J0851.9-4617

(Slane et al. 2001), which has coordinates (RA, Dec

is the SNR angular radius. The SNR center presumably

coincides with the neutron star candidate AX J0851.9-4617

(Slane et al. 2001), which has coordinates (RA, Dec

![]() ,

,

![]() ). The preliminary estimated distances of selected

stars are in the range between 240-2000 pc, so at least some of the stars

lie behind Vela Jr. Positions of all stars of the program across the Vela Jr.

X-ray image (Rosat All Sky Survey data with energies above 1.3 keV) and TeV

). The preliminary estimated distances of selected

stars are in the range between 240-2000 pc, so at least some of the stars

lie behind Vela Jr. Positions of all stars of the program across the Vela Jr.

X-ray image (Rosat All Sky Survey data with energies above 1.3 keV) and TeV

![]() -ray image (Aharonian et al. 2005) are shown in Fig. 1.

-ray image (Aharonian et al. 2005) are shown in Fig. 1.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=70mm,clip]{14031fg1.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa14031-10/Timg20.png)

|

Figure 1:

Positions of the stars across the SNR images taken in TeV

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=80mm,clip]{14031fg2.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa14031-10/Timg28.png)

|

Figure 2:

Observed spectrum of the star HD 75968, synthetic spectrum, and

the residual spectrum with 3 |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Table 2: Parameters of the stars and distances calculated by spectral method and from Hipparcos parallax.

3 Analysis of spectra

The obtained stellar spectra were analyzed by applying a synthetic flux

calculation employing the SynthVb and ATLAS9 codes

to derive the stellar parameters

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

and

,

and ![]() (Table 2).

To determine the rotation velocity, we use a standard method based on

Fourier transformation of profiles of weak spectral

lines (Carroll 1933). We adopted the limb darkening parameter

(Table 2).

To determine the rotation velocity, we use a standard method based on

Fourier transformation of profiles of weak spectral

lines (Carroll 1933). We adopted the limb darkening parameter

![]() .

.

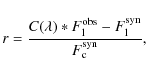

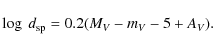

The parameters of stellar atmosphere models were found by fitting the

synthesized profiles to six Balmer lines (H7-H12). The fitting procedure

includes multiplication of the observed spectra by a fitting factor

![]() ,

which is defined as the linear approximation to the ratio of synthetic to observed

spectrum

,

which is defined as the linear approximation to the ratio of synthetic to observed

spectrum

![]() .

In this case, we do not introduce any

nonlinear distortion into the observed spectrum. The best fit is attained

by minimizing the relative residual flux between the observed and synthetic spectrum

.

In this case, we do not introduce any

nonlinear distortion into the observed spectrum. The best fit is attained

by minimizing the relative residual flux between the observed and synthetic spectrum

|

(1) |

where

3.1 Interstellar reddening and distance estimate

Interstellar reddening in the observed spectra is taken into account using extinction data reported by Mathis (1990). In the first step, we determine stellar parameters and calculate normal color indexes (B-V)0 (Castelli & Kurucz 2003). We then use the observed (B-V) to derive color excess E(B-V) and V-band absorption, AV=3.1E(B-V). At the second step, we improve our determination of the stellar atmosphere parameters and recalculate the reddening.

To determine distances, we employ a modified method of spectral parallaxes in which

the stellar luminosity is derived from stellar evolutionary tracks as follows.

Using stellar parameters (

![]() and

and ![]() )

and evolutionary

tracks (Schaller et al. 1992), we estimate the stellar mass and thus derive

the bolometric luminosity. The absolute magnitude MV is then determined

using the bolometric correction taken from (Bessell et al. 1998). The

luminosity and distance are thus determined from the standard formulae

)

and evolutionary

tracks (Schaller et al. 1992), we estimate the stellar mass and thus derive

the bolometric luminosity. The absolute magnitude MV is then determined

using the bolometric correction taken from (Bessell et al. 1998). The

luminosity and distance are thus determined from the standard formulae

| (2) |

| (3) |

|

(4) |

The normal color index (B-V)0, interstellar absorption AV, stellar masses M, and distances are listed in Table 2. In the last column, we also indicate the available distances according to HIPPARCOS parallaxes (van Leeuwen 2007). The distances determined by both methods agree within errors (Fig. 3), which supports the reliability of distances obtained by the method of spectral parallax.

3.2 Interstellar lines

The relative residual spectra for all the stars are shown in

Fig. 4. The 3![]() levels are also indicated for each star. Large

values of 3

levels are also indicated for each star. Large

values of 3![]() are seen for late B and A type stars with low rotation speeds

due to problems in fitting narrow stellar spectral lines using the accepted solar

abundance of chemical elements. The spectra do not uncover broad absorption

resonance lines of Ca II 3933 Å, 3968 Å, or Fe I 3860 Å.

In particular, the relative depth of the broad Ca II absorption (if any) produced

by Vela Jr. is smaller than 0.04 at the level of

are seen for late B and A type stars with low rotation speeds

due to problems in fitting narrow stellar spectral lines using the accepted solar

abundance of chemical elements. The spectra do not uncover broad absorption

resonance lines of Ca II 3933 Å, 3968 Å, or Fe I 3860 Å.

In particular, the relative depth of the broad Ca II absorption (if any) produced

by Vela Jr. is smaller than 0.04 at the level of ![]() .

We note, that the weak

absorption at 3819 Å and 4009 Å in the hottest stars of our sample are

related to helium lines, which are generally affected by non-LTE excitation and

cannot be modeled reliably in the LTE approximation.

.

We note, that the weak

absorption at 3819 Å and 4009 Å in the hottest stars of our sample are

related to helium lines, which are generally affected by non-LTE excitation and

cannot be modeled reliably in the LTE approximation.

With the exception of two stars (HD 75873 and CD-454645), all the spectra contain

narrow unresolved interstellar Ca II lines; their heliocentric radial velocities

are given in Table 3. The interstellar absorption lines can be divided

into two major groups: low velocity

![]() km s-1, and high velocity

km s-1, and high velocity

![]() km s-1. Most stars have one component with a positive radial

velocity of

km s-1. Most stars have one component with a positive radial

velocity of ![]() 22-48 km s-1. The heliocentric velocity can be translated into a

LSR velocity in this direction using the relation

22-48 km s-1. The heliocentric velocity can be translated into a

LSR velocity in this direction using the relation

![]() km s-1.

This suggests that the dominant population of interstellar clouds in this

direction at the distances not exceeding 2 kpc, are characterized by the positive LSR velocities

km s-1.

This suggests that the dominant population of interstellar clouds in this

direction at the distances not exceeding 2 kpc, are characterized by the positive LSR velocities

![]() 9-35 km s-1. Two stars have negative low velocity components, of -13 km s-1 and -46 km s-1.

9-35 km s-1. Two stars have negative low velocity components, of -13 km s-1 and -46 km s-1.

Three stars have high velocity

components: HD 75309 (+153 km s-1, -92 km s-1), HD 76060 (-92 km s-1), and

CD-454676 (-150 km s-1).

These velocities are typical of high-velocity interstellar Ca II

absorption found earlier in the direction of Vela SNR (Cha & Sembach 2000).

Interestingly, the spectrum of the star HD 75309 from our program was also

studied by Cha & Sembach (2000). Benefitting from the spectrum's high resolution,

these authors were able to find eight components including

two high velocity components, +136 km s-1 and -107 km s-1, and a strong low velocity

component +20 km s-1. The corresponding interstellar absorption lines in

Table 3 are shifted redward by ![]() +16 km s-1, which reflects

the systematic difference in radial velocity between the two sets of data.

This may be partially related to the low resolution of our spectra. We studied

other sources of errors but were unable to explain this disparity.

+16 km s-1, which reflects

the systematic difference in radial velocity between the two sets of data.

This may be partially related to the low resolution of our spectra. We studied

other sources of errors but were unable to explain this disparity.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=70mm,clip]{14031fg3.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa14031-10/Timg47.png)

|

Figure 3: Distance derived by the method of spectral parallax versus distance according Hipparcos parallax. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=16.5cm,clip]{14031fg4.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa14031-10/Timg48.png)

|

Figure 4:

The relative residual spectra with dashed lines showing the 3 |

| Open with DEXTER | |

At least one star, CD-454676, exhibits conspicuous CN absorption of electronic

transitions R(0), R(1), and P(1) with the wavelengths of 3873.994 Å,

3874.602 Å, and 3875.759 Å, respectively. The heliocentric radial velocity of

these lines is +23 km s-1 (

![]() km s-1), which is consistent with the radial

velocity of Ca II interstellar lines in the same star (Table 3).

The equivalent width of R(0) and R(1) lines (W(0)=0.01 Å and

W(1)=0.02 Å) can be used to estimate the excitation temperature of the

rotational level J=1 and the column density of CN residing on rotational

levels J=0 and J=1 in the weak line limit. Using available oscillator

strengths of these transitions (Gredel et al. 2002), we obtain T=6.8 K

and column densities

km s-1), which is consistent with the radial

velocity of Ca II interstellar lines in the same star (Table 3).

The equivalent width of R(0) and R(1) lines (W(0)=0.01 Å and

W(1)=0.02 Å) can be used to estimate the excitation temperature of the

rotational level J=1 and the column density of CN residing on rotational

levels J=0 and J=1 in the weak line limit. Using available oscillator

strengths of these transitions (Gredel et al. 2002), we obtain T=6.8 K

and column densities

![]() cm-2 and

cm-2 and

![]() cm-2. Assuming a Boltzmann population of the

J=2 rotational level

cm-2. Assuming a Boltzmann population of the

J=2 rotational level

![]() ,

we obtain the total CN

column density

,

we obtain the total CN

column density

![]() cm-2. These values are comparable to

those of CN absorbers towards the Vela OB association (Gredel et al. 2002).

cm-2. These values are comparable to

those of CN absorbers towards the Vela OB association (Gredel et al. 2002).

Two stars, HD 75873 and CD-454645, do not exhibit interstellar Ca II lines. In

HD 75873 for which

![]() pc and AV=1.2, the expected contribution of the

interstellar line to the equivalent width should be about 20%. The explanation

of the apparent absence of absorption is the low rotation velocity

pc and AV=1.2, the expected contribution of the

interstellar line to the equivalent width should be about 20%. The explanation

of the apparent absence of absorption is the low rotation velocity

![]() = 15 km s-1 and the high strength of stellar Ca II absorption. Both factors

prevent us from distinguishing interstellar lines in this case. The second star,

CD-454645, at a distance of 330 pc is not expected to have strong

interstellar Ca II lines. Given its very strong stellar Ca II absorption, the

extraction of weak interstellar absorption in this case is precluded.

= 15 km s-1 and the high strength of stellar Ca II absorption. Both factors

prevent us from distinguishing interstellar lines in this case. The second star,

CD-454645, at a distance of 330 pc is not expected to have strong

interstellar Ca II lines. Given its very strong stellar Ca II absorption, the

extraction of weak interstellar absorption in this case is precluded.

Table 3: Velocities of components of Ca II interstellar absorption.

4 Discussion

4.1 Narrow interstellar lines

Most low velocity interstellar Ca II absorbers with

![]() km s-1

are most likely produced by local background clouds. This is also true for CN

absorbers, which in terms of velocity coincide with the Ca II absorbers. The large scatter in

velocities of between

km s-1

are most likely produced by local background clouds. This is also true for CN

absorbers, which in terms of velocity coincide with the Ca II absorbers. The large scatter in

velocities of between

![]() km s-1 exceeding the usual dispersion in cloud

velocities of

km s-1 exceeding the usual dispersion in cloud

velocities of ![]() 10 km s-1 suggests that at least some of these absorbers are

related to clouds accelerated by either shock waves driven by wind bubbles of hot

stars or old SNR. This conjecture is in accord with results of observations

of interstellar ultraviolet O I and Si II absorption lines

(Wallerstein et al. 1995) towards the Vela SNR. Some of these lines arise

from excited fine-structure levels in the Vela SNR direction and indicate the

high pressure of clouds,

10 km s-1 suggests that at least some of these absorbers are

related to clouds accelerated by either shock waves driven by wind bubbles of hot

stars or old SNR. This conjecture is in accord with results of observations

of interstellar ultraviolet O I and Si II absorption lines

(Wallerstein et al. 1995) towards the Vela SNR. Some of these lines arise

from excited fine-structure levels in the Vela SNR direction and indicate the

high pressure of clouds,

![]() dyn cm-2(Wallerstein et al. 1995), which is two orders of magnitude higher than the average

pressure in the interstellar medium (ISM).

dyn cm-2(Wallerstein et al. 1995), which is two orders of magnitude higher than the average

pressure in the interstellar medium (ISM).

The high velocity clouds with

![]() km s-1 are probably related

to the interstellar clouds shocked by the expanding Vela SNR. Similar high

velocity gas was observed in Ca II lines and ultraviolet lines corresponding to different

ions, including C I, O I, Mg I, and Mg II (Jenkins & Wallerstein 1995), and

attributed to radiative shocks driven by the Vela SNR into interstellar clouds of

density

km s-1 are probably related

to the interstellar clouds shocked by the expanding Vela SNR. Similar high

velocity gas was observed in Ca II lines and ultraviolet lines corresponding to different

ions, including C I, O I, Mg I, and Mg II (Jenkins & Wallerstein 1995), and

attributed to radiative shocks driven by the Vela SNR into interstellar clouds of

density ![]() 10 cm-3. Interestingly, the closest star with a

high velocity interstellar component, HD 76060, lies at the distance

10 cm-3. Interestingly, the closest star with a

high velocity interstellar component, HD 76060, lies at the distance

![]() pc. This immediately provides an upper limit to the distance of the

Vela SNR of

pc. This immediately provides an upper limit to the distance of the

Vela SNR of ![]()

![]() pc, which is consistent with the Vela pulsar distance

of 294 pc (Caraveo et al. 2001).

pc, which is consistent with the Vela pulsar distance

of 294 pc (Caraveo et al. 2001).

4.2 Broad absorption related to Vela Jr.

The absence of Fe I and Ca II broad absorption lines in stellar spectra towards Vela Jr. requires explanation. As we will see below, singly ionized metals should be more abundantly present in the Vela Jr. ejecta, and therefore absorption by neutral iron, with its relatively low ionization fraction and low value of the oscillator strength, should be significantly weaker than Ca II absorption. We therefore concentrate on the absence of broad Ca II lines. At least four possibilities are conceivable: Vela Jr. is farther than the most distant star in our sample; the SNR is much older; and the Ca II ionization fraction is small, i.e., Ca resides predominantly in the Ca I or in the Ca III ionization state. Discussion of these possibilities requires modeling the broad Ca II absorptions expected at the given age for the remnants of the different SN types.

4.2.1 Broad Ca II absorption for different supernova types

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=85mm,clip]{14031fg5.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa14031-10/Timg63.png)

|

Figure 5: The relative residual spectra for the stars. The distance increases upward. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

The unshocked ejecta expands freely, i.e., the expansion law at a

given age t is v=r/t. To describe this we will use cylindrical

coordinates (z, p, ![]() )

with z-axis coincident with the line

of sight directed towards the center of SNR.

The absorption produced by the scattering of the background stellar

radiation in Ca II 3933, 3968 Å lines at the radial velocity

vz is determined by a Sobolev optical depth

in the resonant plane z=vzt along the line of sight of

impact parameter p (assuming that the ejecta is spherically symmetric)

)

with z-axis coincident with the line

of sight directed towards the center of SNR.

The absorption produced by the scattering of the background stellar

radiation in Ca II 3933, 3968 Å lines at the radial velocity

vz is determined by a Sobolev optical depth

in the resonant plane z=vzt along the line of sight of

impact parameter p (assuming that the ejecta is spherically symmetric)

| (5) |

where the multipliers in the right-hand side in order are oscillator strength, wavelength, Ca II number density at the given radius r=(z2+p2)1/2, and the SNR age t.

For a given concentration of Ca determined by the density and Ca abundance,

the line strength depends on

the ionization fraction of Ca II. At the early phase of the ejecta expansion, at the time of ![]() yr after SN explosion,

the calcium ionization in ejecta of any type SN

is controlled primarily by the ionization loss of fast electrons

(Compton electrons and positrons) produced by

the radioactive decay chain 56Ni - 56Co - 56Fe and radiative

recombination. At the stage of

yr after SN explosion,

the calcium ionization in ejecta of any type SN

is controlled primarily by the ionization loss of fast electrons

(Compton electrons and positrons) produced by

the radioactive decay chain 56Ni - 56Co - 56Fe and radiative

recombination. At the stage of ![]() yr, spectra of SNe of

different types are dominated by the emission lines of singly ionized

metals, which indicates that singly ionized metals dominate.

This is supported by numerical models of ionization and thermal

balance of ejecta powered by the radioactive decay of 56Co

for SN Ia (Axelrod 1980) and SN IIP (Kozma & Fransson 1998).

At the later stages

yr, spectra of SNe of

different types are dominated by the emission lines of singly ionized

metals, which indicates that singly ionized metals dominate.

This is supported by numerical models of ionization and thermal

balance of ejecta powered by the radioactive decay of 56Co

for SN Ia (Axelrod 1980) and SN IIP (Kozma & Fransson 1998).

At the later stages ![]() yr, the ionization is dominated by positrons from

44Ti decay. Our estimate indicates that even a maximal expected mass

yr, the ionization is dominated by positrons from

44Ti decay. Our estimate indicates that even a maximal expected mass

![]() of 44Ti is insufficient to maintain the high ionization

of Ca. At later stages, therefore, recombination

dominates and Ca may become mostly neutral.

of 44Ti is insufficient to maintain the high ionization

of Ca. At later stages, therefore, recombination

dominates and Ca may become mostly neutral.

However, at the SNR age of ![]() yr the characteristic recombination time of Ca

is larger than the expansion time. At this stage, the ionization

by the starlight may become essential.

For example, Fesen et al. (1999) demonstrate that calcium in the ejecta

of SN 1885 in M 31

can be efficiently ionized by the bulge starlight within the ionization

time of

about 10 yr. In the case of Vela Jr. we use the model of the starlight spectrum

in the Galactic plane at the radius of 7.5 kpc given

by Porter et al. (2006),

and the photoionization cross-sections of Verner et al. (1996). The found

photoionization time is

yr the characteristic recombination time of Ca

is larger than the expansion time. At this stage, the ionization

by the starlight may become essential.

For example, Fesen et al. (1999) demonstrate that calcium in the ejecta

of SN 1885 in M 31

can be efficiently ionized by the bulge starlight within the ionization

time of

about 10 yr. In the case of Vela Jr. we use the model of the starlight spectrum

in the Galactic plane at the radius of 7.5 kpc given

by Porter et al. (2006),

and the photoionization cross-sections of Verner et al. (1996). The found

photoionization time is ![]() 180 yr for Ca I and

180 yr for Ca I and ![]()

![]() yr for

Ca II. At the age of

yr for

Ca II. At the age of ![]() 700 yr, we thus expect that Ca in Vela Jr.

should be singly ionized.

700 yr, we thus expect that Ca in Vela Jr.

should be singly ionized.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=90mm]{14031fg6.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa14031-10/Timg72.png)

|

Figure 6: Absorption profile of Ca II doublet expected in the stellar spectrum of different progenitors of Vela Jr. Shown are cases of impact parameter equal to 0, 0.5, and 0.8. The strongest absorption always corresponds to zero impact parameter. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

The ionization of Ca II by X-rays from the reverse shock, and by accelerated

protons may also play a role. The X-rays ionize metals from K and

L shells,

and photoelectrons then ionize Ca II. For the observed X-ray

flux

![]() erg cm-2 s-1 in the 0.5-10 keV band,

the characteristic photoionization time for Ca II at the SNR age of 700 yr

is found to be

erg cm-2 s-1 in the 0.5-10 keV band,

the characteristic photoionization time for Ca II at the SNR age of 700 yr

is found to be ![]() 108 yr

for SN Ia, and this process is thus negligible.

Ionization by relativistic protons accelerated in the shock wave can be

estimated by assuming an average efficiency of cosmic ray acceleration

per SN of 10% and the shock wave energy

of

108 yr

for SN Ia, and this process is thus negligible.

Ionization by relativistic protons accelerated in the shock wave can be

estimated by assuming an average efficiency of cosmic ray acceleration

per SN of 10% and the shock wave energy

of ![]() 1051 erg. We find then that the ionization time for Ca II

at the age of 700 yr is

1051 erg. We find then that the ionization time for Ca II

at the age of 700 yr is ![]()

![]() yr, which is larger than the SNR age.

We thus conclude that cosmic rays for the adopted acceleration efficiency

essentially cannot ionize Ca II, so all the calcium in the unshocked

ejecta of Vela Jr. is expected to remain in Ca II.

yr, which is larger than the SNR age.

We thus conclude that cosmic rays for the adopted acceleration efficiency

essentially cannot ionize Ca II, so all the calcium in the unshocked

ejecta of Vela Jr. is expected to remain in Ca II.

Table 4: Adopted parameters of supernovae.

The predicted profiles of the Ca II doublet at the age of 700 yr

for different varieties of SNe are shown in Fig. 6 assuming

that all the calcium is in the Ca II state. We assume that in SN IIP and SN Ibc

the Ca abundance is solar, while for SN Ia we assume that the Ca/Fe ratio

by mass is solar, while the total mass of iron in the ejecta is

![]() .

Ejecta parameters for different SNe are given in Table 4.

Apart from SN Ia, SN IIP, and SN Ibc, we also consider energetic SN Ic, so-called

hypernovae, which is designated hereafter as SN Ic(h).

The boundary velocity of the unshocked ejecta is taken to be 5000 km s-1 in accordance with the distance of 200 pc and the age of 700 yr.

The density distributions

.

Ejecta parameters for different SNe are given in Table 4.

Apart from SN Ia, SN IIP, and SN Ibc, we also consider energetic SN Ic, so-called

hypernovae, which is designated hereafter as SN Ic(h).

The boundary velocity of the unshocked ejecta is taken to be 5000 km s-1 in accordance with the distance of 200 pc and the age of 700 yr.

The density distributions ![]() in the unshocked ejecta are assumed to be

exponential for compact pre-SNe and to form a plateau with the outer power law

in the unshocked ejecta are assumed to be

exponential for compact pre-SNe and to form a plateau with the outer power law

![]() for SN IIP. The plotted profiles are computed for

three values of impact parameter in units of the angular radius: 0, 0.5, and

0.8. The absorption is predicted to be deep for all the impact parameters

in the case of SN Ia, rather deep for SN IIP, very weak for SN Ibc, and

negligible (relative depth <0.006) in the case of SN Ic(h).

If the age and distance of Vela Jr. are close to the values adopted above,

the progenitor would be unlikely of type SN Ia or SN IIP; instead an association of the SNR with

a SN Ibc or SN Ic(h) is quite plausible.

for SN IIP. The plotted profiles are computed for

three values of impact parameter in units of the angular radius: 0, 0.5, and

0.8. The absorption is predicted to be deep for all the impact parameters

in the case of SN Ia, rather deep for SN IIP, very weak for SN Ibc, and

negligible (relative depth <0.006) in the case of SN Ic(h).

If the age and distance of Vela Jr. are close to the values adopted above,

the progenitor would be unlikely of type SN Ia or SN IIP; instead an association of the SNR with

a SN Ibc or SN Ic(h) is quite plausible.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=90mm]{14031fg7.eps}\vspace*{-4mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa14031-10/Timg81.png)

|

Figure 7:

Age-distance relations provided by 44Ti mass (thick solid lines)

and radius of the supernova remnant. The radius is calculated for SN IIP

(dotted line), SN Ia (thin solid line), SN Ibc (short-dashed line),

SN Ic(h) with

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

4.2.2 How far away might Vela Jr. be?

We now relax arguments used earlier to constrain the age and distance of Vela Jr. (Aschenbach 1998; Iyudin et al. 1998) and check whether Vela Jr. lies at a very large distance, >1 kpc, beyond any star in our sample.

For a given 44Ti mass, a combination of age and distance is constrained by

the observed flux in the gamma-ray line 1.16 MeV. Nucleosynthesis models predict a

production of

![]() of 44Ti in

SN Ia (Iwamoto et al. 1998) and

of 44Ti in

SN Ia (Iwamoto et al. 1998) and

![]() in

core-collapse SNe (Woosley & Weaver 1995). An independent estimate of the

44Ti yield per SN can be obtained by assuming that almost all the

44Ca is produced as 44Ti both in SN Ia (Iwamoto et al. 1999) and

core-collapse SNe (Woosley & Weaver 1995). The solar mass ratio of

44Ca to 56Fe is 10-3, which means that SN IIP and SN Ibc

producing

0.05-0.1 of 56Ni per SN should eject

in

core-collapse SNe (Woosley & Weaver 1995). An independent estimate of the

44Ti yield per SN can be obtained by assuming that almost all the

44Ca is produced as 44Ti both in SN Ia (Iwamoto et al. 1999) and

core-collapse SNe (Woosley & Weaver 1995). The solar mass ratio of

44Ca to 56Fe is 10-3, which means that SN IIP and SN Ibc

producing

0.05-0.1 of 56Ni per SN should eject

![]() of 44Ti, while SN Ic(h) producing, in a similar way to SN 1998bw,

up to

of 44Ti, while SN Ic(h) producing, in a similar way to SN 1998bw,

up to

![]() of 56Ni (Iwamoto et al. 1998) is able to eject

as much as

of 56Ni (Iwamoto et al. 1998) is able to eject

as much as ![]()

![]() of 44Ti. We therefore, expect,

that the mass of 44Ti ejected by SNe of different types

lies in the range

of 44Ti. We therefore, expect,

that the mass of 44Ti ejected by SNe of different types

lies in the range

![]() .

The corresponding

relationship between the age and distance suggested by the observed flux of the

1.16 MeV line

.

The corresponding

relationship between the age and distance suggested by the observed flux of the

1.16 MeV line

![]() cm-2 s-1 is shown in

Fig. 7 for the two extreme values of ejected 44Ti mass.

cm-2 s-1 is shown in

Fig. 7 for the two extreme values of ejected 44Ti mass.

Deceleration of supernova ejecta in the interstellar medium provides us

with another relation between the distance and age for a given choice of ejecta

parameters, ISM density, and angular radius of Vela Jr. We compute the

interaction of ejecta with the ISM in the thin shell approximation

(Chevalier 1982) assuming typical ejecta

mass and energy (Table 4). In the case of SN IIP, the adopted

hydrogen number density of ISM is 0.3 cm-3, which is the average density of the

warm neutral medium (WNM). The latter comprises about 80% of the ISM

mass (Wolfire et al. 1995). For SN Ia apart from WNM, we also consider the

ISM in the form of a hot ionized medium (HIM) of density

0.003 cm-3. This gas occupies about 50-60% of the

volume (Wolfire et al. 1995). As in the case of SN Ibc and SN Ic(h), they explode in

the ISM modified by the fast main-sequence wind, slow red supergiant wind, and

the Wolf-Rayet wind. We consider

![]() and

and

![]() as template

progenitor stars; both cases were explored by Garcia-Segura et al. (1996).

According to these results the pre-SN in the

as template

progenitor stars; both cases were explored by Garcia-Segura et al. (1996).

According to these results the pre-SN in the

![]() case is imbedded in a

hot bubble of the uniform density of

case is imbedded in a

hot bubble of the uniform density of ![]() 0.003 cm-3 with a radius of

18 pc surrounded by a dense cool shell of total mass

0.003 cm-3 with a radius of

18 pc surrounded by a dense cool shell of total mass

![]()

![]() .

For the

.

For the

![]() progenitor, the bubble density is

progenitor, the bubble density is

![]() 0.001 cm-3 and its radius is 50 pc. We note in passing that a

model of Vela Jr. (RXJ0852.0-4622) taken to be of the SNII/Ib type exploded in a

wind blown cavity was considered by Berezhko et al. (2009).

0.001 cm-3 and its radius is 50 pc. We note in passing that a

model of Vela Jr. (RXJ0852.0-4622) taken to be of the SNII/Ib type exploded in a

wind blown cavity was considered by Berezhko et al. (2009).

The age-distance relations for all the discussed cases are shown

in Fig. 7. The SN Ia exploded in the HIM phase shows almost the same

age-distance relation as SN Ibc and is therefore not shown in this figure. This

diagnostic plot is similar to that used by Chen & Gehrels (1999). The

essential difference, however, is that they used a set of arbitrary expansion

velocities of the swept-up shell, while we calculate the evolution of the shell

radius for each type of SN. For a given age, the minimal distance corresponds to

a SN IIP expanding in the WNM phase, while the maximal distance corresponds to a

SN Ic(h) with a

![]() progenitor. In combination with the 44Ti

curves, these two cases imply the allowed ranges of 450-900 yr and 150-1000 pc

for the age and distance of Vela Jr., respectively. The major result of this plot

is that the distance of Vela Jr. cannot exceed 1 kpc. We thus conclude that at

least several stars in our sample (Table 2) are behind the SNR.

This permits us to disregard the explanation of the absence of broad Ca II

absorption being the result of the large distance to Vela Jr.

progenitor. In combination with the 44Ti

curves, these two cases imply the allowed ranges of 450-900 yr and 150-1000 pc

for the age and distance of Vela Jr., respectively. The major result of this plot

is that the distance of Vela Jr. cannot exceed 1 kpc. We thus conclude that at

least several stars in our sample (Table 2) are behind the SNR.

This permits us to disregard the explanation of the absence of broad Ca II

absorption being the result of the large distance to Vela Jr.

4.2.3 Was the progenitor of Vela Jr. a hypernova?

The absence of broad Ca II absorption in the spectra of stars at distances >1 kpc suggests that the SNR progenitor was either of SN Ibc or SN Ic(h) because only for these SNe is the expected absorption weak and possibly undetected (Fig. 6). To distinguish between these two SN possibilities, one should take into account the intrinsic width of the 1.16 MeV line.

In the case of SN Ibc at the age

of 650 yr, the expected profile of the 44Ti line (cf. Fig. 7) convolved with the instrumental profile

(![]() keV) is found to be too narrow compared with the observed one

(Fig. 8a), even assuming homogeneous mixing of 44Ti up to a

velocity of 10 000 km s-1. The observed broad profile of the 1.16 MeV line implies

that most of the ejecta mass consisting of 44Ti has significantly larger velocities. However, the SN Ic(h)

case with maximal expansion velocities of 31 300 km s-1at the age of

keV) is found to be too narrow compared with the observed one

(Fig. 8a), even assuming homogeneous mixing of 44Ti up to a

velocity of 10 000 km s-1. The observed broad profile of the 1.16 MeV line implies

that most of the ejecta mass consisting of 44Ti has significantly larger velocities. However, the SN Ic(h)

case with maximal expansion velocities of 31 300 km s-1at the age of ![]() 500 yr

(the case of

500 yr

(the case of

![]() )

and spherically-symmetric distribution of

44Ti homogeneously mixed to 31 000 km s-1 does not help resolve the ambiguity

either (Fig. 8a).

)

and spherically-symmetric distribution of

44Ti homogeneously mixed to 31 000 km s-1 does not help resolve the ambiguity

either (Fig. 8a).

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=90mm,clip]{14031fg8.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa14031-10/Timg91.png)

|

Figure 8:

Profile of 1.16 MeV line of 44Ti. Panel a): profiles for

SN Ibc (thin line) and SN Ic(h) (thick line) with spherically-symmetric

distribution of 44Ti. Panel b): profiles for SN Ic(h) with 44Ti

distributed in the external parts of bi-polar jets at inclination angles of

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

The solution to the line width problem might be found by taking into account

that iron-peak elements are ejected by SN Ic(h) in the form of high velocity

bipolar jets and assuming that 44Ti resides only in the outer parts of the

jets. 56Ni-rich bipolar jets are predicted by the collapsar model

(MacFadyen & Woosley 1999) proposed for the hypernova SN 1998bw, and the jet-like

structure is consistent with the spectral line profiles

(Maeda et al. 2006). Maeda & Nomoto (2003) also predict

an external location of 44Ti. In the 1.16 MeV profile simulations, we assume

that 44Ti is homogeneously distributed along the radius in the velocity

range of

20 000-31 000 km s-1 within jets of opening angle

![]() and inclination angle

and inclination angle ![]() .

We took into account the light travel-time delay

that produces the profile skewed towards red. Two cases are shown

(Fig. 8b) for the angle between the jet axis and the line of

sight,

.

We took into account the light travel-time delay

that produces the profile skewed towards red. Two cases are shown

(Fig. 8b) for the angle between the jet axis and the line of

sight,

![]() and

and

![]() ,

both of which fit the data more closely

than the spherically symmetric model. We therefore conclude that the hypernova

model with the outer location of 44Ti in bipolar jets of SN Ic(h)

is consistent both with the absence of the broad Ca II absorption, and the broad 1.16 MeV profile.

,

both of which fit the data more closely

than the spherically symmetric model. We therefore conclude that the hypernova

model with the outer location of 44Ti in bipolar jets of SN Ic(h)

is consistent both with the absence of the broad Ca II absorption, and the broad 1.16 MeV profile.

A problem with the SN Ic(h) scenario is that the high ejecta velocity

implied by this model infers a low ambient density, which seems to disagree

with the baryonic origin of TeV gamma-ray emission from Vela Jr. Gamma ray production via

pp-collisions seems to be the preferred model compared to the inverse Compton

mechanism (Aharonian et al. 2005; Berezhko et al. 2009). An alternative may be provided by assuming

that we see the early stage of the interaction of the SNR with a

dense environment that has not yet been affected by the previous expansion dynamics.

This conjecture is in line with the low expansion velocity found for the NW rim by

Katsuda et al. (2008).

Another discomfort is related to the hypernova being a rare variety

of SNe that comprises only about 1% of all SNe Ibc

(Podsiadlowski et al. 2004). Only high signal-to-noise spectral imaging of

Vela Jr. in the 1.16 MeV line band with energy resolution of ![]() 40 keV and

angular resolution of

40 keV and

angular resolution of ![]()

![]() may confirm (or reject) the high velocities

of 44Ti and detect any jet-like (if any) structure of the 44Ti

distribution.

may confirm (or reject) the high velocities

of 44Ti and detect any jet-like (if any) structure of the 44Ti

distribution.

Given the difficulties arising in the interpretation of data on Vela Jr., we should not exclude out completely the possibility that this SNR is older (Katsuda et al. 2008). However, only additional observations at different wavelength bands will be able to help pinpoint the age and the origin of Vela Jr.

5 Conclusions

We have presented our attempt to detect unshocked ejecta of the young SNR Vela Jr. by analyzing broad Ca II absorption lines in spectra of background stars. We obtained and analyzed spectra of 14 stars across Vela Jr. using standard methods of spectral synthesis. We concluded that broad absorption lines are absent. TheThe absence of broad Ca II absorption lines and the constraints imposed by the flux of the 44Ti gamma-ray line and the angular size of the SNR imply that only SN Ibc or energetic SN Ic (hypernovae) could have produced Vela Jr., if our estimates of the age and distance are correct. The additional constraint provided by the width of the 1.16 MeV 44Ti line also supports the hypernova scenario for Vela Jr. origin. However, we emphasize the need for more reliable data on the 44Ti gamma-ray line profile and higher resolution imaging of Vela Jr. in the gamma line to verify the hypernova scenario.

References

- Aharonian, F., Akhperjanian, A. G., Bazer-Bachi, A. R., et al. 2005, A&A, 437, L7 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Aschenbach, B. 1998, Nature, 396, 141 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Aschenbach, B., Iyudin, A. F., & Schönfelder, V. 1999, A&A, 350, 997 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Axelrod, T. S. 1980, Ph.D. Thesis (California Univ., Santa Cruz.) [Google Scholar]

- Bamba, A., Yamazaki, R., & Hiraga, J. S. 2005, ApJ, 632, 294 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Berezhko, E. G., Pühlhofer, G., & Völk, H. J. 2009, A&A, 505, 641 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Bessell, M. S., Castelli, F., & Plez, B. 1998, A&A, 333, 231 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Caraveo, P. A., De Luca, A., Mignani, R. P., & Bignami, G. F. 2001, ApJ, 561, 930 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, J. A. 1933, MNRAS, 93, 478 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Castelli, F., & Kurucz, R. L. 2003, in Modelling of Stellar Atmospheres, ed. N. Piskunov, W. W. Weiss, & D. F. Gray, IAU Symp., 210, 20 [Google Scholar]

- Cha, A. N., & Sembach, K. R. 2000, ApSS, 126, 399 [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W., & Gehrels, N. 1999, ApJ, 514, L103 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chevalier, R. A. 1982, ApJ, 259, 302 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, A. R., & Green, D. A. 2000, A&A, 364, 732 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Fesen, R. A., Saken, J. M., & Hamilton, A. J. S. 1989, ApJ, 341, L55 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Fesen, R. A., Gerardy, C. L., McLin, K. M., & Hamilton, A. J. S. 1999, ApJ, 514, 195 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Segura, G., Langer, N., & Mac Low, M. 1996, A&A, 316, 133 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Gredel, R., Pineau des Forêts, G., & Federman, S. R. 2002, A&A, 389, 993 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, A. J. S., Fesen, R. A., Wu, C., Crenshaw, D. M., & Sarazin, C. L. 1997, ApJ, 481, 838 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, A. J. S., Fesen, R. A., & Blair, W. P. 2007, MNRAS, 381, 771 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Iwamoto, K., Mazzali, P. A., Nomoto, K., et al. 1998, Nature, 395, 672 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Iwamoto, K., Brachwitz, F., Nomoto, K., et al. 1999, ApJSS, 125, 439 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [MathSciNet] [Google Scholar]

- Iyudin, A. F., Schönfelder, V., Bennett, K., et al. 1998, Nature, 396, 142 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, E. B., & Wallerstein, G. 1995, ApJ, 440, 227 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Katsuda, S., Tsunemi, H., & Mori, K. 2008, ApJ, 678, L35 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kozma, C., & Fransson, C. 1998, ApJ, 496, 946 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kurucz, R. 1993, ATLAS9 Stellar Atmosphere Programs and 2 km s-1 grid. Kurucz CD-ROM (Cambridge, Mass.: Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory), 13 [Google Scholar]

- MacFadyen, A. I., & Woosley, S. E. 1999, ApJ, 524, 262 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda, K., & Nomoto, K. 2003, ApJ, 598, 1163 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda, K., Mazzali, P. A., & Nomoto, K. 2006, ApJ, 645, 1331 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mathis, J. S. 1990, ARA&A, 28, 37 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Podsiadlowski, P., Mazzali, P. A., Nomoto, K., Lazzati, D., & Cappellaro, E. 2004, ApJ, 607, L17 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Porter, T. A., Moskalenko, I. V., & Strong, A. W. 2006, ApJ, 648, L29 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Schaller, G., Schaerer, D., Meynet, G., & Maeder, A. 1992, A&ASS, 96, 269 [Google Scholar]

- Slane, P., Hughes, J. P., Edgar, R. J., et al. 2001, ApJ, 548, 814 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Tsymbal, V., Lyashko, D., & Weiss, W. W. 2003, in Modelling of Stellar Atmospheres, ed. N. Piskunov, W. W. Weiss, & D. F. Gray, IAU Symp., 210, 49 [Google Scholar]

- van Leeuwen, F. 2007, A&A, 474, 653 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Verner, D. A., Ferland, G. J., Korista, K. T., & Yakovlev, D. G. 1996, ApJ, 465, 487 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein, G., Vanture, A., & Jenkins, E. B. 1995, ApJ, 455, 590 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler, P. F., Long, K. S., Hamilton, A. J. S., & Fesen, R. A. 2005, ApJ, 624, 189 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfire, M. G., Hollenbach, D., McKee, C. F., Tielens, A. G. G. M., & Bakes, E. L. O. 1995, ApJ, 443, 152 [Google Scholar]

- Woosley, S. E., & Weaver, T. A. 1995, ApJSS, 101, 181 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

All Tables

Table 1: List of the observed stars.

Table 2: Parameters of the stars and distances calculated by spectral method and from Hipparcos parallax.

Table 3: Velocities of components of Ca II interstellar absorption.

Table 4: Adopted parameters of supernovae.

All Figures

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=70mm,clip]{14031fg1.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa14031-10/Timg20.png)

|

Figure 1:

Positions of the stars across the SNR images taken in TeV

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=80mm,clip]{14031fg2.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa14031-10/Timg28.png)

|

Figure 2:

Observed spectrum of the star HD 75968, synthetic spectrum, and

the residual spectrum with 3 |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=70mm,clip]{14031fg3.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa14031-10/Timg47.png)

|

Figure 3: Distance derived by the method of spectral parallax versus distance according Hipparcos parallax. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=16.5cm,clip]{14031fg4.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa14031-10/Timg48.png)

|

Figure 4:

The relative residual spectra with dashed lines showing the 3 |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=85mm,clip]{14031fg5.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa14031-10/Timg63.png)

|

Figure 5: The relative residual spectra for the stars. The distance increases upward. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=90mm]{14031fg6.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa14031-10/Timg72.png)

|

Figure 6: Absorption profile of Ca II doublet expected in the stellar spectrum of different progenitors of Vela Jr. Shown are cases of impact parameter equal to 0, 0.5, and 0.8. The strongest absorption always corresponds to zero impact parameter. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=90mm]{14031fg7.eps}\vspace*{-4mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa14031-10/Timg81.png)

|

Figure 7:

Age-distance relations provided by 44Ti mass (thick solid lines)

and radius of the supernova remnant. The radius is calculated for SN IIP

(dotted line), SN Ia (thin solid line), SN Ibc (short-dashed line),

SN Ic(h) with

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=90mm,clip]{14031fg8.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa14031-10/Timg91.png)

|

Figure 8:

Profile of 1.16 MeV line of 44Ti. Panel a): profiles for

SN Ibc (thin line) and SN Ic(h) (thick line) with spherically-symmetric

distribution of 44Ti. Panel b): profiles for SN Ic(h) with 44Ti

distributed in the external parts of bi-polar jets at inclination angles of

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

Copyright ESO 2010

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.