| Issue |

A&A

Volume 519, September 2010

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A79 | |

| Number of page(s) | 9 | |

| Section | Extragalactic astronomy | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/200913924 | |

| Published online | 16 September 2010 | |

Adaptive optics near infrared integral field spectroscopy of

NGC 2992![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

S. Friedrich1 - R. I. Davies1 - E. K. S. Hicks1 - H. Engel1 - F. Müller-Sánchez1,2 - R. Genzel1,3 - L. J. Tacconi1

1 - Max-Planck-Institut für extraterrestrische Physik, Postfach 1312, 85741 Garching, Germany

2 -

Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias, 38205 La Laguna (Tenerife), Spain

3 -

Department of Physics, Le Conte Hall, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA

Received 21 December 2009 / Accepted 12 May 2010

Abstract

Aims. NGC 2992 is an intermediate Seyfert 1 galaxy

showing outflows on kilo parsec scales which might be due either to AGN

or starburst activity. We therefore aim at investigating its central

region for a putative starburst in the past and its connection to the

AGN and the outflows.

Methods. Observations were performed with the adaptive optics

near infrared integral field spectrograph SINFONI on the VLT,

complemented by longslit observations with ISAAC on the VLT, as well as

N- and Q-band data from the Spitzer archive. The spatial

and spectral resolutions of the SINFONI data are 50 pc and

83 km s-1, respectively. The field of view of

![]() corresponds to 450 pc

corresponds to 450 pc ![]() 450 pc. Br

450 pc. Br![]() equivalent width and line fluxes from PAHs were compared to stellar

population models to constrain the age of the putative recent star

formation. A simple geometric model of two mutually inclined disks and

an additional cone to describe an outflow was developed to explain the

observed complex velocity field in H2 1-0S(1).

equivalent width and line fluxes from PAHs were compared to stellar

population models to constrain the age of the putative recent star

formation. A simple geometric model of two mutually inclined disks and

an additional cone to describe an outflow was developed to explain the

observed complex velocity field in H2 1-0S(1).

Results. The morphologies of the Br![]() and the stellar continuum are different suggesting that at least part of the Br

and the stellar continuum are different suggesting that at least part of the Br![]() emission comes from the AGN. This is confirmed by PAH emission lines at 6.2

emission comes from the AGN. This is confirmed by PAH emission lines at 6.2 ![]() m and 11.2

m and 11.2 ![]() m and the strength of the silicon absorption feature at 9.7

m and the strength of the silicon absorption feature at 9.7 ![]() m,

which point to dominant AGN activity with a relatively minor starburst

contribution. We find a starburst age of 40-50 Myr from Br

m,

which point to dominant AGN activity with a relatively minor starburst

contribution. We find a starburst age of 40-50 Myr from Br![]() line diagnostics and the radio continuum; ongoing star formation can be

excluded. Both the energetics and the timescales indicate that the

outflows are driven by the AGN rather than the starburst. The complex

velocity field observed in H2 1-0S(1) in the central 450 pc can be explained by the superposition of the galaxy rotation and an outflow.

line diagnostics and the radio continuum; ongoing star formation can be

excluded. Both the energetics and the timescales indicate that the

outflows are driven by the AGN rather than the starburst. The complex

velocity field observed in H2 1-0S(1) in the central 450 pc can be explained by the superposition of the galaxy rotation and an outflow.

Key words: galaxies: active - galaxies: individual: NGC 2992 - galaxies: Seyfert - galaxies: starburst - infrared: galaxies

1 Introduction

NGC 2992, initially classified as a Seyfert 2, was later classified as an

intermediate Seyfert 1 galaxy on the basis of a broad H![]() component

with no corresponding H

component

with no corresponding H![]() component in its nuclear spectrum (Ward et

al. 1980). Later, Glass (1997) suggested that it is a hybrid

between an intermediate Seyfert and a starburst galaxy, induced by the

interaction with NGC 2993 to the south. Both galaxies are connected by a

tidal tail with a projected length of 2

component in its nuclear spectrum (Ward et

al. 1980). Later, Glass (1997) suggested that it is a hybrid

between an intermediate Seyfert and a starburst galaxy, induced by the

interaction with NGC 2993 to the south. Both galaxies are connected by a

tidal tail with a projected length of 2

![]() 9.

9.

NGC 2992 is highly inclined by about 70

![]() to our line of

sight with a broad disturbed lane of dust in its equatorial plane.

The redshift is 0.0077 which corresponds to a

distance of 32.5 Mpc and an angular scale of 150 pc per arcsec assuming

H0=75 km s-1 Mpc-1.

to our line of

sight with a broad disturbed lane of dust in its equatorial plane.

The redshift is 0.0077 which corresponds to a

distance of 32.5 Mpc and an angular scale of 150 pc per arcsec assuming

H0=75 km s-1 Mpc-1.

At a wavelength of 6 cm NGC 2992 shows prominent loops to the northwest and

southeast. This feature, designated as figure-of-8, has a size

of about 8

![]() with the long axis at a position angle (PA) of

with the long axis at a position angle (PA) of

![]() ,

which is not coincident or perpendicular to the major axis

(Ulvestad & Wilson 1984). Chapman et

al. (2000) conclude from their IR observations that the most convincing

interpretation for these loops is that of expanding gas bubbles which are seen

as limb-brigthened loops as was already proposed by Wehrle & Morris

(1988).

Two possible explanations are discussed for the origin

of the loops: they may be driven by an AGN or a superwind from a

compact starburst. X-ray observations point to the first possibility:

Colbert et al. (1998) concluded that the large scale

outflows are driven by nonthermal jets from

the AGN that entrain the surrounding material and heat it by shocks over kpc

spatial scales.

,

which is not coincident or perpendicular to the major axis

(Ulvestad & Wilson 1984). Chapman et

al. (2000) conclude from their IR observations that the most convincing

interpretation for these loops is that of expanding gas bubbles which are seen

as limb-brigthened loops as was already proposed by Wehrle & Morris

(1988).

Two possible explanations are discussed for the origin

of the loops: they may be driven by an AGN or a superwind from a

compact starburst. X-ray observations point to the first possibility:

Colbert et al. (1998) concluded that the large scale

outflows are driven by nonthermal jets from

the AGN that entrain the surrounding material and heat it by shocks over kpc

spatial scales.

Heckman et al. (1981) reported complex kinematics in NGC 2992 on

the basis of longslit spectra at PA = 120![]() .

This work was extended by Colina

et al. (1987) who find indications for an outflow within a plane

highly inclined to the plane of the galaxy.

Márquez et al. (1998) measured [O III] and H

.

This work was extended by Colina

et al. (1987) who find indications for an outflow within a plane

highly inclined to the plane of the galaxy.

Márquez et al. (1998) measured [O III] and H![]() lines at nine different position angles and concluded, although from a

simple kinematical model, that the double peaked line profiles and

asymmetries can be accounted for by an outflow within a conical

envelope or on the surface of a hollow cone. The high spectral

resolution observations (4.9 Å: 3440-5579 Å, 11.9 Å:

5840-9725 Å) of narrow line regions in NGC 2992 of Allen

et al. (1999) show at most positions a double

component line profile. One component of the double peaked lines follows the

galactic rotation curve, while the other is identified as a wind that is

expanding out of the plane of the galaxy with a velocity of up to

200 km s-1. These authors did not find spectral evidence for a

significant contribution from a starburst to the outflow.

lines at nine different position angles and concluded, although from a

simple kinematical model, that the double peaked line profiles and

asymmetries can be accounted for by an outflow within a conical

envelope or on the surface of a hollow cone. The high spectral

resolution observations (4.9 Å: 3440-5579 Å, 11.9 Å:

5840-9725 Å) of narrow line regions in NGC 2992 of Allen

et al. (1999) show at most positions a double

component line profile. One component of the double peaked lines follows the

galactic rotation curve, while the other is identified as a wind that is

expanding out of the plane of the galaxy with a velocity of up to

200 km s-1. These authors did not find spectral evidence for a

significant contribution from a starburst to the outflow.

Depending on the inclinations of galaxy and cone several interpretations of these kinematics are possible. It is generally assumed that the NW edge of the disk of NGC 2992 is closest to us with trailing spiral arms, and that the SE cone is closer and directed at us. However, an arc-shaped emission found by García-Lorenzo et al. (2001), which might be associated with the radio loop, is red shifted in the SE, and can therefore only be consistent with an outflow if it is pointing away from us.

In this paper, we present spatially and spectrally resolved

K-band observations of the inner

![]() of NGC 2992 taken with the adaptive optics integral field spectrograph

SINFONI. These are complemented by longslit observations along the

major axis out to a radius of about 5

of NGC 2992 taken with the adaptive optics integral field spectrograph

SINFONI. These are complemented by longslit observations along the

major axis out to a radius of about 5

![]() with ISAAC, and N- and Q-band spectra from

the Spitzer archive. SINFONI data were taken with unprecedent spatial resolution in the K-band

which allows us to study the dynamics of gas and stars in the central

region in detail. Together with the spectral resolution of SINFONI this

enables us to search for a starburst and its connection to the AGN and,

possibly, to the outflows. After presenting the observational results

in Sect. 3, we discuss the observations in Sect. 4, and show

that there is evidence for a nuclear starburst in NGC 2992. Finally, in

Sect. 5 we concentrate on the dynamics of the gas and stars and

the consequences on the geometry of the galaxy.

with ISAAC, and N- and Q-band spectra from

the Spitzer archive. SINFONI data were taken with unprecedent spatial resolution in the K-band

which allows us to study the dynamics of gas and stars in the central

region in detail. Together with the spectral resolution of SINFONI this

enables us to search for a starburst and its connection to the AGN and,

possibly, to the outflows. After presenting the observational results

in Sect. 3, we discuss the observations in Sect. 4, and show

that there is evidence for a nuclear starburst in NGC 2992. Finally, in

Sect. 5 we concentrate on the dynamics of the gas and stars and

the consequences on the geometry of the galaxy.

2 Observations and data reduction

2.1 SINFONI

K-band spectra of NGC 2992 between approximately 1.95 ![]() m and 2.45

m and 2.45 ![]() m

were taken on 13 March 2005 at the VLT with SINFONI, an adaptive optics

near infrared integral field spectrograph (Eisenhauer et al. 2003; Bonnet et al. 2004)

with a spectral resolution of 3600. The pixel scale was

m

were taken on 13 March 2005 at the VLT with SINFONI, an adaptive optics

near infrared integral field spectrograph (Eisenhauer et al. 2003; Bonnet et al. 2004)

with a spectral resolution of 3600. The pixel scale was

![]() and the exposure time 600 s for both object and sky frames. Object frames were interspersed with sky frames

using the sequence O-S-O-O-S-O. A total of 12 object frames were obtained,

resulting in a total exposure time of two hours. For a near diffraction limited

correction the nucleus of the galaxy was used by the AO module.

and the exposure time 600 s for both object and sky frames. Object frames were interspersed with sky frames

using the sequence O-S-O-O-S-O. A total of 12 object frames were obtained,

resulting in a total exposure time of two hours. For a near diffraction limited

correction the nucleus of the galaxy was used by the AO module.

Data were reduced in a standard manner by subtraction sky frames, flatfielding, correcting bad pixels, and wavelength calibration with an arc lamp using the SPRED software package (Abuter et al. 2006), which also performs the reconstruction of the data cube. No spatial smoothing by a median filter was applied. Telluric correction and flux calibration were performed with the G2V star HD 85724 (K=7881). Residuals from the OH line emission were removed using the method described in Davies (2007a).

The spatial resolution has been estimated from both the broad Br![]() and

the non-stellar continuum (Davies 2007b). Both methods yield

symmetric PSFs with FWHMs of 0

and

the non-stellar continuum (Davies 2007b). Both methods yield

symmetric PSFs with FWHMs of 0

![]() 32 and 0

32 and 0

![]() 29, respectively, corresponding to

48 pc and 44 pc, respectively. The spectral resolution derived from sky

lines is 83 km s-1. NGC 2992 is part of a (heterogeneous) sample

of type 1 and type 2 Seyfert galaxies, ULIRGs, and a Quasar, which were observed to

investigate the connection between star formation and AGN. Further details on

data reduction can be found in Davies et al. (2007) and Hicks et al. (2009).

29, respectively, corresponding to

48 pc and 44 pc, respectively. The spectral resolution derived from sky

lines is 83 km s-1. NGC 2992 is part of a (heterogeneous) sample

of type 1 and type 2 Seyfert galaxies, ULIRGs, and a Quasar, which were observed to

investigate the connection between star formation and AGN. Further details on

data reduction can be found in Davies et al. (2007) and Hicks et al. (2009).

2.2 ISAAC

NGC 2992 was also observed on 13 January 2006 with the Infrared Spectrometer

And Array Camera ISAAC at the VLT in order to obtain wide FOV longslit spectra

centered on 2.1 ![]() m (to measure H2 1-0S(1)) and 2.29

m (to measure H2 1-0S(1)) and 2.29 ![]() m (to measure 12CO(2-0)). The 2

m (to measure 12CO(2-0)). The 2![]() long and 0

long and 0

![]() 3 wide slit was aligned parallel to the morphological large scale major (PA = 34.62

3 wide slit was aligned parallel to the morphological large scale major (PA = 34.62![]() )

and minor axes (PA = -55.38

)

and minor axes (PA = -55.38![]() ),

respectively. The exposure time amounts to 40 min per slit

position. The spectra were reduced using standard techniques carried

out by the ESO pipeline software.

),

respectively. The exposure time amounts to 40 min per slit

position. The spectra were reduced using standard techniques carried

out by the ESO pipeline software.

In order to determine line positions, and subsequently radial velocities of

H2 1-0S(1), a spectrum from the outer edge of the galaxy's major or minor axes

was extracted, the signal-to-noise determined and if necessary the spectrum

from the adjoining pixel added until a

![]() was reached. This procedure was repeated along the slit to the opposite

edge of the galaxy resulting in a set of 114 and 62 individual spectra

along the major and minor axes, respectively. Br

was reached. This procedure was repeated along the slit to the opposite

edge of the galaxy resulting in a set of 114 and 62 individual spectra

along the major and minor axes, respectively. Br![]() (2.16

(2.16 ![]() m) can also be

detected in these spectra. These 2D-data sets were then analysed in a

similar way to their 3D counterparts (see Sect. 5).

m) can also be

detected in these spectra. These 2D-data sets were then analysed in a

similar way to their 3D counterparts (see Sect. 5).

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm,clip]{13924fig1.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa13924-09/Timg22.png)

|

Figure 1:

SINFONI-Spectrum of NGC 2992 integrated over the whole FOV of

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

3 Observational results

3.1 The spectrum of NGC 2992

In Fig. 1 we show the SINFONI spectrum of NGC 2992 integrated over the

whole FOV of

![]() centered on the nucleus. The most

prominent lines are H2 1-0S(3) at 1.958

centered on the nucleus. The most

prominent lines are H2 1-0S(3) at 1.958 ![]() m,

m,

![]() at 1.96

at 1.96 ![]() m,

H2 1-0S(1) at 2.12

m,

H2 1-0S(1) at 2.12 ![]() m, and Br

m, and Br![]() at 2.16

at 2.16 ![]() m, other molecular

hydrogen transitions and some CO bandheads are also present. The line fluxes are

summarized in Table 1 together with line fluxes from Gilli et al. (2000).

m, other molecular

hydrogen transitions and some CO bandheads are also present. The line fluxes are

summarized in Table 1 together with line fluxes from Gilli et al. (2000).

Table 1:

Measured line fluxes for NGC 2992 in a field of view of

![]() centered on the nucleus.

centered on the nucleus.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=12cm,clip]{13924fig2.eps} %

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa13924-09/Timg33.png)

|

Figure 2:

Continuum, velocity, and dispersion maps of NGC 2992 ( left to

right) of stars, Br |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Variability of the infrared flux of NGC 2992 was already reported by Glass

(1997). Apart from an outburst in 1988, which was especially strong

in the K- and L-band, he reported a fading of NGC 2992 by about 20% in

the K-band, 50% in the L-band between 1978 and 1996, and by a factor of

![]() 20

in X-rays at the same time. Then, in 1998 BeppoSAX observations showed

the X-ray flux to be again similar to that of 1978 (Gilli et al. 2000). Also

line properties of Balmer- and Paschen-lines in the near infrared were similar

to those observed before the decline. It is obvious from Table 1

that our line fluxes from 2005 (determined for a similar aperture size) are

higher than those of Gilli et al. (2000) from January 1999. Unfortunately we have no information about H

20

in X-rays at the same time. Then, in 1998 BeppoSAX observations showed

the X-ray flux to be again similar to that of 1978 (Gilli et al. 2000). Also

line properties of Balmer- and Paschen-lines in the near infrared were similar

to those observed before the decline. It is obvious from Table 1

that our line fluxes from 2005 (determined for a similar aperture size) are

higher than those of Gilli et al. (2000) from January 1999. Unfortunately we have no information about H![]() and Pa

and Pa![]() to compare them to former observations

given in Gilli et al.

to compare them to former observations

given in Gilli et al.

Oliva et al. (1995) show that the 12CO(2-0) at 2.2 ![]() m in the K-band, and the 12CO(6-3) bandhead at 1.6

m in the K-band, and the 12CO(6-3) bandhead at 1.6 ![]() m in the H-band,

can be used to separate stellar and non-stellar continua in AGN.

However, doing so requires high signal-to-noise data in both bands.

Instead, we follow the method of Davies et al. (2007) which uses

just the 12CO(2-0) bandhead to calculate the fraction of the nuclear flux

that is stellar. By assuming that the stellar equivalent width in the nuclear

region is about 12 Å, regardless of the star formation history, as

predicted by the models created with the stellar synthesis code STARS

(Sternberg 1998; Sternberg et al. 2003), which is

comparable to Starburst99 (Leitherer et al. 1999; Vazquez &

Leitherer 2005), we calculated the non-stellar dilution using the equation:

m in the H-band,

can be used to separate stellar and non-stellar continua in AGN.

However, doing so requires high signal-to-noise data in both bands.

Instead, we follow the method of Davies et al. (2007) which uses

just the 12CO(2-0) bandhead to calculate the fraction of the nuclear flux

that is stellar. By assuming that the stellar equivalent width in the nuclear

region is about 12 Å, regardless of the star formation history, as

predicted by the models created with the stellar synthesis code STARS

(Sternberg 1998; Sternberg et al. 2003), which is

comparable to Starburst99 (Leitherer et al. 1999; Vazquez &

Leitherer 2005), we calculated the non-stellar dilution using the equation:

|

(1) |

where D is the fraction of the continuum that is non-stellar. We found an equivalent width of (

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=7cm,clip]{13924fig3a.eps}\hspace*{3mm}

\includegraphics[width=7cm,clip]{13924fig3b.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa13924-09/Timg41.png)

|

Figure 3: Velocity (left) and velocity dispersion maps (right) of H2 1-0S(1) with the contours of the radio flux at 8.46 GHz (Leipski et al. 2006, courtesy Heino Falcke) and the rough positions of the redshifted and blueshifted velocity residuals of [O III] (dashed lines at bottom and top) found by García-Lorenzo et al. (2001) overlayed. North is up and east to the left. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

3.2 2-dimensional flux distributions, velocities, and velocity dispersions

2-dimensional flux distributions, velocities, and velocity dispersions of individual

lines were determined by fitting the unresolved line profile of an OH line,

which was convolved with a Gaussian, to the respective lines.

The continuum level was found by a linear fit to the spectrum and subtracted.

The uncertainty of a fit was estimated using ![]() techniques by

refitting the best-fit Gaussian with added noise at the same level as the

data 100 times. Standard deviations of the best-fit parameters are then used

as the uncertainties. Uncertainties of velocities and velocity dispersions are

of the order of 10 km s-1 to 15 km s-1 for the 12CO(2-0)

bandhead at 2.2

techniques by

refitting the best-fit Gaussian with added noise at the same level as the

data 100 times. Standard deviations of the best-fit parameters are then used

as the uncertainties. Uncertainties of velocities and velocity dispersions are

of the order of 10 km s-1 to 15 km s-1 for the 12CO(2-0)

bandhead at 2.2 ![]() m (i.e. for the stars) and

Br

m (i.e. for the stars) and

Br![]() ,

and about 5 km s-1 for H2 1-0S(1). Errors of the

continuum range from below 1% for Br

,

and about 5 km s-1 for H2 1-0S(1). Errors of the

continuum range from below 1% for Br![]() and H2 1-0S(1), and 6% for

the stars.

and H2 1-0S(1), and 6% for

the stars.

In Fig. 2 we show the morphology of the stellar continuum, the

Br![]() - and H2 1-0S(1) lines and their

respective velocities and velocity dispersions. The spatial resolution is 0.3

- and H2 1-0S(1) lines and their

respective velocities and velocity dispersions. The spatial resolution is 0.3

![]() corresponding to a length scale of about 50 pc; the spectral resolution is

83 km s-1. The continuum seems to trace an inclined disk with the

north-west side more obscured. Given the broad dust lane seen in optical

images this is not surprising.

corresponding to a length scale of about 50 pc; the spectral resolution is

83 km s-1. The continuum seems to trace an inclined disk with the

north-west side more obscured. Given the broad dust lane seen in optical

images this is not surprising.

There exist remarkable differences. Firstly, the morphology of the Br![]() line does not follow the stellar continuum. To make this more obvious the

contour lines of the Br

line does not follow the stellar continuum. To make this more obvious the

contour lines of the Br![]() continuum are overlaid in Fig. 2 on

the stellar continuum. The center of the stellar continuum is shifted to the

south east and the intensity distribution is elongated in the north east

to south west direction in contrast to the circular Br

continuum are overlaid in Fig. 2 on

the stellar continuum. The center of the stellar continuum is shifted to the

south east and the intensity distribution is elongated in the north east

to south west direction in contrast to the circular Br![]() contour. This

means that part of the Br

contour. This

means that part of the Br![]() emission must be attributed to other sources

than a starburst. On the other side, the morphology of the H2 1-0S(1) line

is similar to the stellar continuum.

emission must be attributed to other sources

than a starburst. On the other side, the morphology of the H2 1-0S(1) line

is similar to the stellar continuum.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=15.5cm,clip]{13924fig4.eps} \vspace*{-2mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa13924-09/Timg43.png)

|

Figure 4:

Supernova rate and Br |

| Open with DEXTER | |

The zero line of the velocity is orientated roughly east west in all three

velocity maps. The maximum velocities range from +100 km s-1 to

+170 km s-1 and the minimum

velocities from -100 km s-1 to -140 km s-1.

The velocity map of the stars shows a distinct

increase to up to 100 km s-1 at the position of the centre of the

Br![]() continuum.

continuum.

The stellar component, Br![]() and H2 1-0S(1) all show velocities

away from us in the southwest and towards us in the northeast. The velocity

field of H2 1-0S(1) and also that of Br

and H2 1-0S(1) all show velocities

away from us in the southwest and towards us in the northeast. The velocity

field of H2 1-0S(1) and also that of Br![]() ,

albeit not as clearly, show

redshifted emission also to the southeast. García-Lorenzo et al. (2001) investigated the velocity field of [O III]

and found an arc of redshifted velocities to the southeast and one of

blueshifted velocities to the northwest with velocities of (

,

albeit not as clearly, show

redshifted emission also to the southeast. García-Lorenzo et al. (2001) investigated the velocity field of [O III]

and found an arc of redshifted velocities to the southeast and one of

blueshifted velocities to the northwest with velocities of (![]() ) km s-1, and

(

) km s-1, and

(![]() ) km s-1, respectively. These arcs are just outside our

field of view. Only the redshifted velocities in the south east corner of

H2 might be caused by them (Fig. 3).

Since these ``arcs'' resemble the loops of the figure-of-8 when

superimposed on the radio emission there might be a relation between

both structures. However, this would suggest an inflow, if the

southeast part of the figure-of-8 is closer to us, as generally

assumed. In the picture of expanding gas bubbles this cannot be

understood.

) km s-1, respectively. These arcs are just outside our

field of view. Only the redshifted velocities in the south east corner of

H2 might be caused by them (Fig. 3).

Since these ``arcs'' resemble the loops of the figure-of-8 when

superimposed on the radio emission there might be a relation between

both structures. However, this would suggest an inflow, if the

southeast part of the figure-of-8 is closer to us, as generally

assumed. In the picture of expanding gas bubbles this cannot be

understood.

Already Chapman et al. (2000) proposed that the radio morphology consists of a component out of the plane of the galaxy disk and one within the disk associated with a spiral arm. On the basis of the narrow and well defined spectral lines within the arcs García-Lorenzo et al. conclude that the arcs are due to gas in the disk rather than in the loops. However, none of the arcs is associated with the structures that Chapman et al. interpret as spiral arms.

There is a small region in the velocity field of Br![]() which extends from

west of the centre to nearly the edge of the FOV in the SW with a lower

velocity relative to its surroundings. This can be interpreted

as an outflow superimposed on the galaxy rotation. Although it coincides with

the southern inner spiral arm found by Chapman et al. (2000) in their model-subtracted R- and H-band images, it cannot be related to it because then the spiral arm would move

relative to the ambient medium. There is no counterpart in the H2 1-0S(1) and stellar continuum velocity fields.

which extends from

west of the centre to nearly the edge of the FOV in the SW with a lower

velocity relative to its surroundings. This can be interpreted

as an outflow superimposed on the galaxy rotation. Although it coincides with

the southern inner spiral arm found by Chapman et al. (2000) in their model-subtracted R- and H-band images, it cannot be related to it because then the spiral arm would move

relative to the ambient medium. There is no counterpart in the H2 1-0S(1) and stellar continuum velocity fields.

Common to both the stars and the lines are relatively high velocity dispersions of up to 250 km s-1 for the stars and Br![]() ,

and 130 km s-1 for H2 1-0S(1). However, the stellar dispersion map shows no structures, except that there seems to be a

local minimum at the position of the centre of the Br

,

and 130 km s-1 for H2 1-0S(1). However, the stellar dispersion map shows no structures, except that there seems to be a

local minimum at the position of the centre of the Br![]() continumm. There, the measured velocities range from

(110-150) km s-1

continumm. There, the measured velocities range from

(110-150) km s-1 ![]() (20-30) km s-1 compared to the surrounding values of more than

(20-30) km s-1 compared to the surrounding values of more than

![]() km s-1. This high stellar velocity dispersion which we observe even on the smallest scales suggests that

the K-band light is dominated by stars in the bulge.

km s-1. This high stellar velocity dispersion which we observe even on the smallest scales suggests that

the K-band light is dominated by stars in the bulge.

The high velocity dispersion of Br![]() is confined to the inner 1

is confined to the inner 1

![]() 2,

outside dropping to (0-30) km s-1. The dispersion of

H2 1-0S(1) shows maxima of 150 km s-1 to the southwest and northeast of the

centre, which correspond with the velocity maxima and minima. They also lie at

the edge of radio features within the loops (Fig. 3) and may be

associated with inner spiral arms. The dispersion of H2 1-0S(1) also

shows a local minimum at the centre where the dispersion drops to

70 km s-1. There might also be a local maximum at the position of the

centre of the Br

2,

outside dropping to (0-30) km s-1. The dispersion of

H2 1-0S(1) shows maxima of 150 km s-1 to the southwest and northeast of the

centre, which correspond with the velocity maxima and minima. They also lie at

the edge of radio features within the loops (Fig. 3) and may be

associated with inner spiral arms. The dispersion of H2 1-0S(1) also

shows a local minimum at the centre where the dispersion drops to

70 km s-1. There might also be a local maximum at the position of the

centre of the Br![]() contour.

contour.

The complexity and the differences of velocity and dispersion maps of the stars and the lines might be due to the superposition of the galaxy rotation and an outflow as it was already suggested by several authors (e.g. Chapman et al. 2000).

4 Constraining nuclear star formation in NGC 2992

The possible existence of a nuclear starburst in NGC 2992 was

investigated by Davies et al. (2007), who compared the

radial profile of the stellar continuum to an r1/4 law and an exponential

profile. They found that there might be excess continuum at

![]() due to a distinct stellar population superimposed on

the bulge. However, although the size scale matched the nuclear star forming regions in

other AGN with typical HWHM of 10-50 pc (s. Fig. 5 in Davies et al. 2007), they did not reach a conclusion on NGC 2992 because the excess was only

apparent for an exponential profile. Data at a higher resolution of about 0

due to a distinct stellar population superimposed on

the bulge. However, although the size scale matched the nuclear star forming regions in

other AGN with typical HWHM of 10-50 pc (s. Fig. 5 in Davies et al. 2007), they did not reach a conclusion on NGC 2992 because the excess was only

apparent for an exponential profile. Data at a higher resolution of about 0

![]() 1

would be needed to explore the spatial properties further. Instead,

here we look at various star formation diagnostics in order to assess

the luminosity and age of a putative nuclear starburst.

1

would be needed to explore the spatial properties further. Instead,

here we look at various star formation diagnostics in order to assess

the luminosity and age of a putative nuclear starburst.

The stellar population synthesis code STARS (e.g. Sternberg

1998; Sternberg et al. 2003) was also used to model the

equivalent width of Br![]() and the supernova rate. The program follows the

evolution of a cluster of stars through the Hertzsprung-Russell-Diagram depending on

the star formation history. We assumed decaying star formation rates with timescales of 106 (instantaneous), 107, 108, and 1012 (continuous) years. In Fig. 4 the results from STARS together with the observations are presented. Further details on star

formation diagnostics can be found in Davies et al. (2007).

and the supernova rate. The program follows the

evolution of a cluster of stars through the Hertzsprung-Russell-Diagram depending on

the star formation history. We assumed decaying star formation rates with timescales of 106 (instantaneous), 107, 108, and 1012 (continuous) years. In Fig. 4 the results from STARS together with the observations are presented. Further details on star

formation diagnostics can be found in Davies et al. (2007).

4.1 Br equivalent width and supernova rate

equivalent width and supernova rate

Using the stellar continuum luminosity from Sect. 3.1, an

upper limit for the equivalent width of Br![]() associated with star

formation from the narrow Br

associated with star

formation from the narrow Br![]() line flux can be estimated. However, for

NGC 2992 it is difficult to quantify what fraction of Br

line flux can be estimated. However, for

NGC 2992 it is difficult to quantify what fraction of Br![]() is associated with star

formation, since the morphology of the line does not follow the

stars (Fig. 2). Especially the south-west side shows velocities which

are blue shifted relative to their environment indicative of motions towards us.

The different morphology of H2 1-0S(1) and Br

is associated with star

formation, since the morphology of the line does not follow the

stars (Fig. 2). Especially the south-west side shows velocities which

are blue shifted relative to their environment indicative of motions towards us.

The different morphology of H2 1-0S(1) and Br![]() found in Sect. 3.2 points

towards a kinematically different origin, and supports the conclusion that at

least part of the Br

found in Sect. 3.2 points

towards a kinematically different origin, and supports the conclusion that at

least part of the Br![]() emission is due to the AGN and not to star formation. Thus the narrow Br

emission is due to the AGN and not to star formation. Thus the narrow Br![]() line flux includes a certain unknown fraction from the AGN and the derived equivalent width of

line flux includes a certain unknown fraction from the AGN and the derived equivalent width of

![]() Å is only an upper limit. This value, and all the numbers throughout the rest of the paper, are determined in the central

Å is only an upper limit. This value, and all the numbers throughout the rest of the paper, are determined in the central

![]() unless

otherwise specified.

unless

otherwise specified.

We estimate a supernova rate for NGC 2992 from the unresolved radio flux of 7 mJy at 5 GHz (Wehrle & Morris 1988) and the estimation done by Sadler et al. (1995) that the core flux at 5 GHz is less than 6 mJy. Their estimation is based on their higher spatial resolution measurements at 2.3 GHz and the non-detections at 1.7 GHz and 8.4 GHz. Taking a flat spectral index (Chapman et al. 2000) the 5 GHz flux will not be much less than 6 mJy, which would result in about 1 mJy extended emission. If we assume that it can be attributed to star formation, a supernova rate of 0.003 yr-1 can be derived with the relation of Condon (1992). On the other hand, if we assume a spectral index of 0.82, which was derived by Ulvestad & Wilson (1984) for the unresolved flux at 1.5 GHz and 5 GHz, together with the 2.3 GHz flux of Sadler et al. (1995) we get a flux of about 3 mJy at 5 GHz. This leaves us with about 4 mJy extended emission corresponding to a supernova rate of 0.011 yr-1. We consider the derived supernova rates as extremes and adopt a mean value of 0.007 yr-1.

We can now try to determine a star formation age from the observed Br![]() equivalent width and the supernova rate by comparing them to the theoretical

values calculated by STARS, which are plotted in Fig. 4 for

different star formation timescales. It is immediately obvious that for a continous

star formation the observed Br

equivalent width and the supernova rate by comparing them to the theoretical

values calculated by STARS, which are plotted in Fig. 4 for

different star formation timescales. It is immediately obvious that for a continous

star formation the observed Br![]() equivalent width and the supernova rate yield inconsistent star

formation ages of more than 3 Gyr and (25-50) Myr,

respectively. In addition, an ongoing star formation would require an

equivalent width of Br

equivalent width and the supernova rate yield inconsistent star

formation ages of more than 3 Gyr and (25-50) Myr,

respectively. In addition, an ongoing star formation would require an

equivalent width of Br![]() of 10-15 Å, which is not observed.

of 10-15 Å, which is not observed.

An intermediate decay timescale of 108 yr yields a star formation

age from the Br![]() equivalent width of about 280 Myr and 25-60 Myr from the

supernova rate, which is an order of magnitude lower. Even if we

consider the lower boundary of the supernova rate of 0.003 yr-1 the resulting star formation age of 160 Myr is well below the age derived from the Br

equivalent width of about 280 Myr and 25-60 Myr from the

supernova rate, which is an order of magnitude lower. Even if we

consider the lower boundary of the supernova rate of 0.003 yr-1 the resulting star formation age of 160 Myr is well below the age derived from the Br![]() equivalent width.

equivalent width.

The best agreement between the derived star formation ages from the Br![]() equivalent width and the supernova rate can be achieved for a decay timescale

of 107 yr. The resulting star formation ages amount to 40 Myr and

50 Myr respectively. The largest error of

equivalent width and the supernova rate can be achieved for a decay timescale

of 107 yr. The resulting star formation ages amount to 40 Myr and

50 Myr respectively. The largest error of ![]() 10 Myr

is due to the uncertain radio flux at 5 GHz and subsequently the

supernova rate. The unknown contribution of the AGN to Br

10 Myr

is due to the uncertain radio flux at 5 GHz and subsequently the

supernova rate. The unknown contribution of the AGN to Br![]() does not contribute significantly to the uncertainty, because the

curve is steep. Even an increasing contribution of the AGN up to nearly

100%, which leads to a respective lower stellar contribution to the

Br

does not contribute significantly to the uncertainty, because the

curve is steep. Even an increasing contribution of the AGN up to nearly

100%, which leads to a respective lower stellar contribution to the

Br![]() equivalent width, would increase the age only up to 60 Myr. This

is still within the errors set by the supernova rate. We therefore

conclude that a stellar population exists in NGC 2992 with an age

of 40 Myr to 50 Myr.

equivalent width, would increase the age only up to 60 Myr. This

is still within the errors set by the supernova rate. We therefore

conclude that a stellar population exists in NGC 2992 with an age

of 40 Myr to 50 Myr.

In principal there is also agreement between the Br![]() equivalent width and the

supernova rate for instantaneous star formation at a very young age of about

10 Myr, but we consider this less likely; partly because the timescales are much

shorter, but primarily because it requires very careful tuning to

match the increasing supernova rate and the quickly decaying

Br

equivalent width and the

supernova rate for instantaneous star formation at a very young age of about

10 Myr, but we consider this less likely; partly because the timescales are much

shorter, but primarily because it requires very careful tuning to

match the increasing supernova rate and the quickly decaying

Br![]() equivalent width.

equivalent width.

Combining the age range of 40-50 Myr with the bolometric luminosity and black hole mass for NGC 2992 allows us to locate this galaxy in Fig. 11 of Davies et al. (2007). This figure shows how the luminosity of an AGN might be related to the age of the starburst, and NGC 2992 can be placed in the lower left where the starburst age is young and the AGN is, at the present time, accreting at a rate that is low compared to the Eddington rate. The galaxy thus appears to fit into the proposed scheme, where there is either a delay between the onset of starburst activity and the onset of AGN activity, or star formation ceased once the black hole become active (s. Davies et al. 2007, for a detailed discussion).

We also briefly consider whether the interaction between NGC 2992 and NGC 2993 might be responsible for the starburst. The gravitational (tidal) force during an interaction can be approximated as a delta-function that occurs at perigalacticon. According to Duc et al. (2000) perigalacticon of NGC 2992 and NGC 2993 occurred about 100 Myr ago. At that time the gas would have felt the strongest impulse. Given that it takes time for the gas to respond and, for example, be driven to the centre, it is perhaps plausible for the interaction to have triggered the starburst.

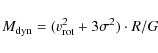

4.2 Mass-to-light-ratio and bolometric luminosity

In order to estimate the mass-to-light-ratio we determined the dynamical mass

within 0

![]() 5 from the following relation:

5 from the following relation:

|

(2) |

where

STARS also allows us to estimate the stellar bolometric luminosity. The ratio

between

![]() and

and ![]() depends on the age and the exponential decay timescale of the star

formation. Given the star formation age of 40-50 Myr we derive a

bolometric luminosity for NGC 2992 of 70-100 times the K-band luminosity or

depends on the age and the exponential decay timescale of the star

formation. Given the star formation age of 40-50 Myr we derive a

bolometric luminosity for NGC 2992 of 70-100 times the K-band luminosity or

![]()

![]() ,

which is (6-8)% of the total bolometric luminosity of NGC 2992

(

,

which is (6-8)% of the total bolometric luminosity of NGC 2992

(

![]()

![]() calculated between 8 and 1000

calculated between 8 and 1000 ![]() m from

IRAS

m from

IRAS

![]() m flux densities, and additionally taking into account the

emission at shorter wavelengths; Davies et al. 2007).

m flux densities, and additionally taking into account the

emission at shorter wavelengths; Davies et al. 2007).

4.3 Star formation rate

Using the star formation history (decay timescale and age) above, we can

estimate the star formation rate.

The first step is to determine what fraction of the K-band

luminosity in the central 0

![]() 5 comes from young stars.

To do so, we estimate the contribution from an old population, by

assuming that the dynamical mass is dominated by this old population.

For an adopted age of 5 Gyr, STARS yields a mass-to-light ratio of

about 30

5 comes from young stars.

To do so, we estimate the contribution from an old population, by

assuming that the dynamical mass is dominated by this old population.

For an adopted age of 5 Gyr, STARS yields a mass-to-light ratio of

about 30

![]() .

The dynamical mass determined above of

.

The dynamical mass determined above of

![]()

![]() then

results in a luminosity of

then

results in a luminosity of

![]()

![]() for the old population, one order of magnitude below the observed K-band luminosity. Therefore the K-band luminosity is dominated by

the young population. We can therefore scale the luminosity of the starburst model to the

total K-band luminosity in the central 0

for the old population, one order of magnitude below the observed K-band luminosity. Therefore the K-band luminosity is dominated by

the young population. We can therefore scale the luminosity of the starburst model to the

total K-band luminosity in the central 0

![]() 5, yielding an initial

star formation rate of 4.3

5, yielding an initial

star formation rate of 4.3 ![]() yr-1 for an age of

50 Myr. Since the SFR is decaying, an alternative, perhaps more meaningful, number may be the

time-averaged star formation rate - which we define as simply the mass of stars

formed divided by the age. This yields

yr-1 for an age of

50 Myr. Since the SFR is decaying, an alternative, perhaps more meaningful, number may be the

time-averaged star formation rate - which we define as simply the mass of stars

formed divided by the age. This yields

![]()

![]() yr-1.

While this appears modest, in terms of SFR per unit area it corresponds

to

yr-1.

While this appears modest, in terms of SFR per unit area it corresponds

to ![]() 200

200 ![]() yr-1 kpc-2, within the range of

values found for the nuclear starbursts in other nearby AGN by Davies

et al. (2007).

yr-1 kpc-2, within the range of

values found for the nuclear starbursts in other nearby AGN by Davies

et al. (2007).

An independent method to estimate the SFR is via the polycyclic aromatic

hydrocarbon (PAH) features.

Farrah et al. (2007) employed diagnostics based on the luminosities

and equivalent widths of fine-structure emission lines and PAH

features as well as the strength of the 9.7 ![]() m silicate

absorption feature to investigate the power source of the infrared emission in

ULIRGs. With these tools they were able to distinguish between starburst and

AGN caused infrared emission, and to determine a star formation rate.

m silicate

absorption feature to investigate the power source of the infrared emission in

ULIRGs. With these tools they were able to distinguish between starburst and

AGN caused infrared emission, and to determine a star formation rate.

In order to apply these diagnostics to NGC 2992 we used near infrared pipeline

reduced IRS spectra from the Spitzer archive. If more than one spectrum

was available we took the mean value from all spectra to determine

line luminosities. 25 ![]() m and 60

m and 60 ![]() m fluxes were taken from the IRAS

Revised Bright Galaxy Sample (Surace et al. 2004). The results are given in Table 2.

m fluxes were taken from the IRAS

Revised Bright Galaxy Sample (Surace et al. 2004). The results are given in Table 2.

The star formation rate

![\begin{displaymath}{\it SFR} \ \left[M_{\rm }\cdot {\rm yr}^{-1}\right]=1.18\tim...

... 6.2~\mu

m}+L_{\rm 11.2~\mu m})\left[\rm erg~ s^{-1}\right]

\end{displaymath}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa13924-09/img67.png)

|

(3) |

was empirically derived from the PAH 6.2

4.4 Starformation versus AGN contribution

The strength of the 7.7 ![]() m PAH feature (1.7

m PAH feature (1.7 ![]() 0.02) indicates that the

AGN in NGC 2992 contributes more than 50% to the infrared flux between

0.02) indicates that the

AGN in NGC 2992 contributes more than 50% to the infrared flux between

![]() m and

m and ![]() m (Genzel et al. 1998).

[Ne V] at 14.32

m (Genzel et al. 1998).

[Ne V] at 14.32 ![]() m, which is strong in AGN spectra but not in star

forming regions, and [O IV], which is strong in star forming regions,

are both present in the spectra of NGC 2992, pointing to a co-existing

starburst and AGN activity.

m, which is strong in AGN spectra but not in star

forming regions, and [O IV], which is strong in star forming regions,

are both present in the spectra of NGC 2992, pointing to a co-existing

starburst and AGN activity.

In order to quantify this a little more we followed Farrah et al. (2007) and compared the equivalent width of the PAH at 6.2 ![]() m (

m (

![]()

![]() m) to the ratio of

[Ne V] to [Ne II] and [O IV] to [Ne II],

respectively. From these diagnostics we derive a 10-20% starburst

fraction and about 50% AGN fraction to the infrared flux for NGC 2992

in agreement with the result from the PAH 7.7

m) to the ratio of

[Ne V] to [Ne II] and [O IV] to [Ne II],

respectively. From these diagnostics we derive a 10-20% starburst

fraction and about 50% AGN fraction to the infrared flux for NGC 2992

in agreement with the result from the PAH 7.7 ![]() m feature. The AGN contribution can also be estimated from the ratio of the 25

m feature. The AGN contribution can also be estimated from the ratio of the 25 ![]() m flux to the 60

m flux to the 60 ![]() m flux against the [Ne V] to [Ne II] ratio. Again the AGN contribution amounts to about 50%.

m flux against the [Ne V] to [Ne II] ratio. Again the AGN contribution amounts to about 50%.

In this and the previous section we utilized different methods to estimate the

contribution of stellar, non-stellar and starburst components to the K-band

and infrared flux (1-1000 ![]() m). Independent of wavelength

range and FOV we found a 50-60% AGN contribution. From the CO bandhead at 2.2

m). Independent of wavelength

range and FOV we found a 50-60% AGN contribution. From the CO bandhead at 2.2 ![]() m we found that 42% of the K-band flux in the central

m we found that 42% of the K-band flux in the central

![]() can be attributed

to stars and from the star formation history that these stars must be

young. Also in the

can be attributed

to stars and from the star formation history that these stars must be

young. Also in the

![]() FOV the K-band light

is dominated by stars. However, according to the high stellar velocity

dispersion it is more likely that stars from the bulge dominate in this larger FOV. Finally,

we find from PAH line diagnostics in the infrared a 10-20% contribution to

the infrared flux from a starburst. In addition to the AGN and starburst components, there

still remains about 20-40%, which must be attributed to a third component

- most likely the disk and bulge of the galaxy. This means that while the

young starbust is important in the central tens of parsecs, it is still only a

small part of the integrated luminosity of the galaxy. Therefore we

conclude that in NGC 2992 we see a dominating AGN activity with a relatively

minor contribution from a starburst.

FOV the K-band light

is dominated by stars. However, according to the high stellar velocity

dispersion it is more likely that stars from the bulge dominate in this larger FOV. Finally,

we find from PAH line diagnostics in the infrared a 10-20% contribution to

the infrared flux from a starburst. In addition to the AGN and starburst components, there

still remains about 20-40%, which must be attributed to a third component

- most likely the disk and bulge of the galaxy. This means that while the

young starbust is important in the central tens of parsecs, it is still only a

small part of the integrated luminosity of the galaxy. Therefore we

conclude that in NGC 2992 we see a dominating AGN activity with a relatively

minor contribution from a starburst.

Table 2: Measured line luminosities of fine-structure lines and PAHs for NGC 2992.

5 Origin of nuclear outflow

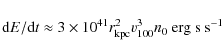

5.1 Starburst or AGN driven outflow

Heckman et al. (1990) provided evidence that galaxies with a

central starburst have large scale mass outflows which are presumably

driven by the kinetic energy supplied by supernovae and winds from massive

stars. In order to examine whether the outflow in NGC 2992 can be caused by

the starburst we calculated the radius r in kpc of a bubble which is

inflated by

energy injected at a constant rate and expanding into a uniform medium with

a density n0 in cm-3 (Heckman et al. 1990). From

|

(4) |

with the velocity (in 100 km s-1)

The 2 kpc extension of the large scale outflow and the velocity of 200 kms-1 suggest that the outflow originated in an event at most 10 Myr ago. This is inconsistent with our derived star formation age of (40-50) Myr but in agreement with the typical timescale of the active phase of a black hole in an AGN. We note that although it is also consistent with the age for instantaneous star formation, this scenario we regarded as rather unlikely since it requires fine-tuning (see Sect. 4.1).

Thompson et al. (2005) showed that optically thick pressure

supported starburst disks have a characteristic flux of about

1013 ![]() kpc-2. Above this limit matter would be blown

away. With the derived luminosity of

kpc-2. Above this limit matter would be blown

away. With the derived luminosity of

![]()

![]() within the central 0

within the central 0

![]() 5 we estimated the characteristic flux for NGC 2992 to be

5 we estimated the characteristic flux for NGC 2992 to be

![]()

![]() kpc-2

which is well below this limit. Only when the starburst was at its peak

luminosity, which for our preferred model is nearly 10 times

greater than the current luminosity, would the star formation approach

- although remaining below - this threshold. The conclusion from both

energy and timescale considerations, is that for the starburst to drive

the outflows it would have to be more intense and more recent - both of

which are ruled out by our analysis.

kpc-2

which is well below this limit. Only when the starburst was at its peak

luminosity, which for our preferred model is nearly 10 times

greater than the current luminosity, would the star formation approach

- although remaining below - this threshold. The conclusion from both

energy and timescale considerations, is that for the starburst to drive

the outflows it would have to be more intense and more recent - both of

which are ruled out by our analysis.

Instead, we consider whether the outflows in NGC 2992 can be driven by

the AGN. In order to estimate the AGN luminosity of NGC 2992 we use the

spectral energy distribution (SED) of NGC 1068 as a template. For this

SED, the optical (750 nm) to 100 keV luminosity is a factor

11.8 greater than that in the 20-100 keV range (Pier et al. 1994). For NGC 2992, the luminosity in this latter range is

![]() erg s-1 (Beckmann et al. 2007).

Thus the total luminosity of NGC 2992 is about an order of magnitude

greater, which yields about 1044 erg s-1.

This is a factor of 3-30 times greater than the energy estimated

above that

is required to generate the outflow. We therefore conclude that it is

the AGN, rather than the starburst, that has driven the outflow.

erg s-1 (Beckmann et al. 2007).

Thus the total luminosity of NGC 2992 is about an order of magnitude

greater, which yields about 1044 erg s-1.

This is a factor of 3-30 times greater than the energy estimated

above that

is required to generate the outflow. We therefore conclude that it is

the AGN, rather than the starburst, that has driven the outflow.

5.2 Velocities along the major axis

Longslit spectra were taken with ISAAC along the major axis (position angle PA = 34

![]() )

at 2.1

)

at 2.1 ![]() m. The resulting velocity curve of H2 1-0S(1) along the slit shows

a steep increase to the southwest (decline to NE) up to a radius of 1

m. The resulting velocity curve of H2 1-0S(1) along the slit shows

a steep increase to the southwest (decline to NE) up to a radius of 1

![]() 5

away from the centre followed by a sharp decline within about 0

5

away from the centre followed by a sharp decline within about 0

![]() 5 and

subsequently a shallower incline. To the northeast the velocity curve behaves

similar. This is also observed in the SINFONI data (Fig. 5), and

is in agreement with published data of Marquez et al. (1998) for a position angle of 30

5 and

subsequently a shallower incline. To the northeast the velocity curve behaves

similar. This is also observed in the SINFONI data (Fig. 5), and

is in agreement with published data of Marquez et al. (1998) for a position angle of 30![]() and Veilleux et al. (2001), too.

and Veilleux et al. (2001), too.

Colina et al. (1987) found asymmetric line profiles for a region with ![]()

![]() ,

and symmetric profiles for

,

and symmetric profiles for ![]()

![]() .

They interpreted their results as dynamically decoupled nuclear and off-nuclear regions. Their velocity curve of [O III]

is in agreement with our velocity curve. However, due to their coarse

sampling along the major axis they could not resolve less than 3

.

They interpreted their results as dynamically decoupled nuclear and off-nuclear regions. Their velocity curve of [O III]

is in agreement with our velocity curve. However, due to their coarse

sampling along the major axis they could not resolve less than 3

![]() .

.

Evidence for dynamical decoupled nuclear and off-nuclear regions comes also from kinemetry (Krajnovic et al. 2006) of our 2-dimensional stellar velocity data. With the position angle and inclination as free parameters the PA changes from

![]() to

to

![]() at about 1

at about 1

![]() (Fig. 6). This is in good agreement with the 22.5

(Fig. 6). This is in good agreement with the 22.5![]() of Jarrett et al. (2003) derived from the

of Jarrett et al. (2003) derived from the ![]() -band 20 mag arcsec-2 isophot. The PA of 45

-band 20 mag arcsec-2 isophot. The PA of 45![]() better fits to the inclination of the accretion disk of about 37

better fits to the inclination of the accretion disk of about 37![]() and 46

and 46![]() ,

derived by Gilli et al. (2000) with the assumption of both Schwarzschild and Kerr metrics from disk line models and iron line profiles,

than to the 34

,

derived by Gilli et al. (2000) with the assumption of both Schwarzschild and Kerr metrics from disk line models and iron line profiles,

than to the 34![]() of García-Lorenzo et al. (2001). The PA of the 2-dimensional H2 1-0S(1) velocity data also changes at 1

of García-Lorenzo et al. (2001). The PA of the 2-dimensional H2 1-0S(1) velocity data also changes at 1

![]() ,

however from

,

however from

![]() to

to

![]() (Fig. 6).

That the changes in PA are derived from kinematic rather than

photometric data, argues that they are real and not just an effect of

extinction. It therefore seems that the stars and the gas show a

different behaviour in the very centre and a similar one outside.

(Fig. 6).

That the changes in PA are derived from kinematic rather than

photometric data, argues that they are real and not just an effect of

extinction. It therefore seems that the stars and the gas show a

different behaviour in the very centre and a similar one outside.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{13924fig5.eps} \vspace*{-2mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa13924-09/Timg99.png)

|

Figure 5:

Radial velocities (top) and corresponding velocity dispersion

(bottom) from longslit spectra taken with ISAAC along

the major axis of NGC 2992 (crosses). Overplotted is a radial velocity

curve drawn from SINFONI data also along the major axis. 1

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{13924fig6a.eps} \includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{13924fig6b.eps} \vspace*{-2mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa13924-09/Timg100.png)

|

Figure 6:

The dependence of the position angle on the distance from the

centre for the 2-dimensional stellar (top) and H2 1-0S(1)

data (bottom). The mean values of the PA for radii below and above

1

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

5.3 A geometric model for the inner 3

3

3

In order to investigate the different components contributing to the

velocity field and to explain the different position angles observed in the

central

![]() of NGC 2992 we developed a simple geometric model. It consists of an

inner and an outer disk, in which particles were assumed to be in

circular motion in a gravitational potential. The radius of the inner

disk is determined by the change in PA found in kinemetry of stellar

and H2 1-0S(1) data at

about 1

of NGC 2992 we developed a simple geometric model. It consists of an

inner and an outer disk, in which particles were assumed to be in

circular motion in a gravitational potential. The radius of the inner

disk is determined by the change in PA found in kinemetry of stellar

and H2 1-0S(1) data at

about 1

![]() .

It is not related to the starburst nor does it reflect the sphere of

gravitational influence of the black hole, which is only a few parsec

in radius. The radius of the outer disk is cut at 5

.

It is not related to the starburst nor does it reflect the sphere of

gravitational influence of the black hole, which is only a few parsec

in radius. The radius of the outer disk is cut at 5

![]() due to our FOV of 3

due to our FOV of 3

![]() .

In addition, a conical outflow with constant velocity represents the figure-of-8. All components could

be rotated by arbitrary angles around the x-, y-, and z-axis,

which points to the observer, thus allowing for different orientations

to each other. Velocities were adjusted in such a way, that they

reflect the observed velocity curve. Due to the simplicity of the

model, we only can draw some qualitative conclusions.

.

In addition, a conical outflow with constant velocity represents the figure-of-8. All components could

be rotated by arbitrary angles around the x-, y-, and z-axis,

which points to the observer, thus allowing for different orientations

to each other. Velocities were adjusted in such a way, that they

reflect the observed velocity curve. Due to the simplicity of the

model, we only can draw some qualitative conclusions.

There is an inner and outer region which must have different orientations in

space (realized in the model by different rotation angles around the x-axis)

in order to explain the different position angles. However, the

inclination angle of 70![]() and the position angles cannot be modelled

exactly at the same time. Dependent on the start value for the ellipticity of the unrotated

outer disk we get an inclination angle of 50

and the position angles cannot be modelled

exactly at the same time. Dependent on the start value for the ellipticity of the unrotated

outer disk we get an inclination angle of 50![]() for a circular disk and

63

for a circular disk and

63![]() for an ellipticity of 0.7, and position angles of 13

for an ellipticity of 0.7, and position angles of 13![]() and

18

and

18![]() ,

respectively. For the inner, circular region we get an inclination

angle of 60

,

respectively. For the inner, circular region we get an inclination

angle of 60![]() and a position angle of 34

and a position angle of 34![]() .

The different inclination

angles might point to a dynamical decoupled inner and outer region as it was

already suggested by Colina et al. (1987).

.

The different inclination

angles might point to a dynamical decoupled inner and outer region as it was

already suggested by Colina et al. (1987).

In order to achieve a position angle of the figure-of-8 consistent with the published -26![]() (Wherle et al. 1988), it has to be perpendicular to a plane whose inclination angle

is 51

(Wherle et al. 1988), it has to be perpendicular to a plane whose inclination angle

is 51![]() ,

which is slightly lower than the inclination of the inner disk. One

can identify this plane with the plane of the accretion disk, which itself is not

modeled. The resulting position angle is -27

,

which is slightly lower than the inclination of the inner disk. One

can identify this plane with the plane of the accretion disk, which itself is not

modeled. The resulting position angle is -27![]() with the SE part of it pointing away from us, consistent with the

redshifted emission there seen by García-Lorenzo et al. (2001).

with the SE part of it pointing away from us, consistent with the

redshifted emission there seen by García-Lorenzo et al. (2001).

The derived geometry from our model yields the values from the literature of 15

![]() for the position angle of the outer region (photometric axis), 34

for the position angle of the outer region (photometric axis), 34

![]() for the inner 5

for the inner 5

![]() (García-Lorenzo et al. 2001), and the inclination of the accretion disk of

(García-Lorenzo et al. 2001), and the inclination of the accretion disk of

![]() (Gilli et al. 2000) very well. The resulting velocity field from this geometry is shown in Fig. 8 and is in good agreement with the measured velocity field of H2 1-0S(1) depicted in the lower panel of Fig. 2. Within this geometry the hump in the velocity curve at 1

(Gilli et al. 2000) very well. The resulting velocity field from this geometry is shown in Fig. 8 and is in good agreement with the measured velocity field of H2 1-0S(1) depicted in the lower panel of Fig. 2. Within this geometry the hump in the velocity curve at 1

![]() 5

is the signature of the cone describing the figure-of-8, which is

superposed on the inner disk. The stellar velocity curve along the

major axis from SINFONI and ISAAC does not show these humps at 1

5

is the signature of the cone describing the figure-of-8, which is

superposed on the inner disk. The stellar velocity curve along the

major axis from SINFONI and ISAAC does not show these humps at 1

![]() 5

which speaks in favour of this interpretation. Our model suggests that

the outer disk, inner disk, and accretion disk are at different

orientations. One possible reason for this is that this geometry

reflects a single warped disk, or even a warped outflow. However, it is

beyond the scope of this paper to explore all the options and to assess

the physical reason behind the observed geometry.

5

which speaks in favour of this interpretation. Our model suggests that

the outer disk, inner disk, and accretion disk are at different

orientations. One possible reason for this is that this geometry

reflects a single warped disk, or even a warped outflow. However, it is

beyond the scope of this paper to explore all the options and to assess

the physical reason behind the observed geometry.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=5.5cm,clip]{13924fig7.eps} \vspace*{-2mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa13924-09/Timg103.png)

|

Figure 7:

Cartoon which shows the geometry of the central region of

NGC 2992. Those parts of the disks with solid lines point towards

us, those with long-dashed away from us. Short-dashed lines indicate

the position angles of 15 |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=7cm,clip]{13924fig8.eps} \vspace*{-2mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa13924-09/Timg104.png)

|

Figure 8: Calculated velocity field in the central region of NGC 2992 resulting from two inclined disks and a conical outflow (see Sect. 5.3.). |

| Open with DEXTER | |

6 Conclusions

We have presented a detailed analysis of near infrared K-band spectra complemented by

N- and Q-band spectra of NGC 2992. K-band spectra were

obtained with the adaptive near infrared integral field spectrograph SINFONI

and allow a reconstruction of the 2-dimensional distribution and kinematic

of the stars and gas in the inner

![]() (450 pc) at

an angular resolution of 0

(450 pc) at

an angular resolution of 0

![]() 3. The N- and Q-band data were obtained with Spitzer and

taken from the archive. We compared the equivalent width of Br

3. The N- and Q-band data were obtained with Spitzer and

taken from the archive. We compared the equivalent width of Br![]() and the

supernova rate, which was derived from radio data from the literature, to

STARS evolutionary synthesis models and find evidence for a short burst of star formation (40-50) Myr ago.

and the

supernova rate, which was derived from radio data from the literature, to

STARS evolutionary synthesis models and find evidence for a short burst of star formation (40-50) Myr ago.

From our near-infrared data as well as equivalent widths and luminosities of

fine-structure emission lines and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon features detected

in the N- and Q-band spectra we were able to estimate the nuclear

star formation rate and quantify the contribution of the

star formation to the AGN luminosity: the luminosity is dominated by

the AGN activity with a contribution of only ![]() from nuclear star

formation. This is in agreement with the conclusion that part of the Br

from nuclear star

formation. This is in agreement with the conclusion that part of the Br![]() emission cannot be attributed to star formation but is due to the AGN.

emission cannot be attributed to star formation but is due to the AGN.

Energy and timescale considerations let us conclude, that the starburst would have to be more recent and more intense to drive the figure-of-8 as well as the large scale (2 kpc) outflow. On the other hand the estimation of the luminosity of the AGN of 1044 erg s-1 is about an order of magnitude higher than is necessary to drive the outflows.

The observed velocity curve in H2 1-0S(1) of NGC 2992 can be described as the superposition of the galaxy rotation and a conical outflow with constant velocity. The different position angles of the inner and outer region can be modelled by disks with different orientations in space and thus being probably dynamically decoupled. However, these disks are not related to the starburst. In this picture the south east cone is pointing away from us supporting the findings from García-Lorenzo (2001).

AcknowledgementsThe authors thank all those at MPE and ESO Paranal who were involved in the SINFONI observations. This work is also based in part on observations made with the Spitzer Space Telescope, which is operated by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology under a contract with NASA.

References

- Abuter, R., Schreiber, J., Eisenhauer, F., et al. 2006, New A Rev., 50, 398 [Google Scholar]

- Allen, M. G., Dopita, M. A., Tsvetanov, Z. I., & Sutherland, R. S. 1999, ApJ, 511, 686 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Beckmann, V., Barthelmy, S. D., Courvoisier, T. J.-L., et al. 2007, A&A, 475, 827 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Bender, R., Burstein, D., & Faber, S. 1992, ApJ, 399, 462 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnet, H., Abuter, R., Baker, A., et al. 2004, The ESO Messanger, 117, 17 [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, S., Morris, S., Alonso-Herrero, A., & Falcke, H. 2000, MNRAS, 314, 263 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Colbert, E. J. M., Baum, S. A., O'Dea, C. P., & Villeux, S. 1998, ApJ, 496, 786 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Colina, L., Fricke, K. J., Kollatschny, W., & Perryman, M. A. C. 1987, A&A, 178, 51 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Condon, J. J. 1992, ARA&A, 30, 575 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [MathSciNet] [Google Scholar]

- Davies, R. I. 2007a, MNRAS, 375, 1099 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Davies, R. I. 2007b, in The 2007 ESO Instrument Calibration Workshop, ESO Astrophys. Symp. [arXiv:astro-ph/0703044] [Google Scholar]

- Davies, R. I., Mueller Sánchez, F., Genzel, R., et al. 2007, ApJ, 671, 1388 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Duc, P.-A., Brinks, E., Springel, V., et al. 2000, AJ, 120, 1238 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhauer, F., Abuter, R., Bickert, K., et al. 2003, in Instrument Design and Performance for Optical/Infrared Ground-based Telescopes, ed. M. Iye, & A. Moorwood, Proc. SPIE, 4841, 1548 [Google Scholar]

- Farrah, D., Bernard-Salas, J., Spoon, H. W. W., et al. 2007, ApJ, 667, 149 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- García-Lorenzo, B., Arribas, S., & Mediavilla, E. 2001, A&A, 378, 787 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Genzel, R., Lutz, D., Sturm, E., et al. 1998, ApJ, 498, 579 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Gilli, R., Maiolino, R., Marconi, A., et al. 2000, A&A, 355, 485 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Glass, I. S. 1997, MNRAS, 292, L50 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Heckman, T. M., Butcher, H. R., Miley, G. K., & van Breugel, W. J. M. 1981, ApJ, 247, 403 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Heckman, T. M., Armus, L., & Miley, G. K. 1990, ApJS, 74, 833 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks, E. K. S., Davies, R. I., Malkan, M. A., et al. 2009, ApJ, 696, 448 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Jarrett, T. H., Chester, T., Cutri, R., Schneider, S. E., & Huchra, J. P. 2003, AJ, 125, 525 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Krajnovic, D., Cappellari, M., de Zeeuw, T., & Copin, Y. 2006, MNRAS, 366, 787 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Leipski, C., Falcke, H., Bennert, N., & Hüttemeister, S. 2006, A&A, 455, 161 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Leitherer, C., Schaerer, D., Goldader, J. D., et al. 1999, ApJS, 123, 3 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Márquez, I., Boisson, C., Durret, F., & Petitjean, P. 1998, A&A, 333, 459 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Oliva, E., Origlia, L., Kotilainen, J. K., & Moorwood, A. F. M. 1995, A&A, 301, 55 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Pier, E. A., Antonucci, R., Hurt, T., Kriss, G., & Krolik, J. 1994, ApJ, 428, 124 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sadler, E., Slee, O., Reynolds, J., & Roy, A. 1995, MNRAS, 276, 1273 [Google Scholar]

- Spoon, H. W. W., Marshall, J. A., Houck, J. R., et al. 2007, ApJ, 654, L49 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg, A. 1998, ApJ, 506, 721 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]