| Issue |

A&A

Volume 517, July 2010

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A27 | |

| Number of page(s) | 19 | |

| Section | Extragalactic astronomy | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201014154 | |

| Published online | 28 July 2010 | |

A study of the interplay between ionized gas and star clusters in the central

region of NGC 5253 with 2D spectroscopy![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

A. Monreal-Ibero1 - J. M. Vílchez2 - J. R. Walsh1 - C. Muñoz-Tuñón3

1 - European Organisation for Astronomical Research

in the Southern Hemisphere, Karl-Schwarzschild-Strasse 2, 85748

Garching bei München, Germany

2 -

Instituto de Astrofísica de Andalucía (CSIC), C/ Camino Bajo de Huétor 50, 18008 Granada, Spain

3 -

Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias, C/ vía Láctea, s/n, 38205 La Laguna, Spain

Received 28 January 2010 / Accepted 24 March 2010

Abstract

Context. Starbursts are one of the main contributors to the

chemical enrichment of the interstellar medium. However, mechanisms

governing the interaction between the recent star formation and the

surrounding gas are not fully understood. Because of their

a priori simplicity, the subgroup of H II galaxies constitute an ideal sample to study these mechanisms.

Aims. A detailed 2D study of the central region of NGC 5253

has been performed to characterize the stellar and ionized gas

structure as well as the extinction distribution, physical properties

and kinematics of the ionized gas in the central ![]() 210 pc

210 pc ![]() 130 pc.

130 pc.

Methods. We utilized optical integral field spectroscopy (IFS) data obtained with FLAMES.

Results. A detailed extinction map for the ionized gas in

NGC 5253 shows that the largest extinction is associated

with the prominent Giant H II region. There is an offset of ![]() 0

0

![]() 5

between the peak of the optical continuum and the extinction peak in

agreement with findings in the infrared. We found that stars suffer

less extinction than gas by a factor of

5

between the peak of the optical continuum and the extinction peak in

agreement with findings in the infrared. We found that stars suffer

less extinction than gas by a factor of ![]() 0.33. The [S II]

0.33. The [S II]![]() 6717/[S II]

6717/[S II]![]() 6731 map shows an electron density (

6731 map shows an electron density (![]() )

gradient declining from the peak of emission in H

)

gradient declining from the peak of emission in H![]() (790 cm-3) outwards, while the argon line ratio traces areas with

(790 cm-3) outwards, while the argon line ratio traces areas with

![]() cm-3. The area polluted with extra nitrogen, as deduced from the excess [N II]

cm-3. The area polluted with extra nitrogen, as deduced from the excess [N II]![]() 6584/H

6584/H![]() ,

extends up to distances of 3

,

extends up to distances of 3

![]() 3 (

3 (![]() 60 pc) from the maximum pollution, which is offset by

60 pc) from the maximum pollution, which is offset by ![]() 1

1

![]() 5 from the peak of continuum emission. Wolf-Rayet features are distributed in an irregular pattern over a larger area (

5 from the peak of continuum emission. Wolf-Rayet features are distributed in an irregular pattern over a larger area (![]() pc

pc ![]() 100 pc) and associated with young stellar clusters. We measured He+ abundances over most of the field of view and values of He++/H+

100 pc) and associated with young stellar clusters. We measured He+ abundances over most of the field of view and values of He++/H+ ![]() 0.0005

in localized areas which do not coincide, in general, with the

areas presenting W-R emission or extra nitrogen. The line profiles

are complex. Up to three emission components were needed to

reproduce them. One of them, associated with the giant H II region, presents supersonic widths and [N II]

0.0005

in localized areas which do not coincide, in general, with the

areas presenting W-R emission or extra nitrogen. The line profiles

are complex. Up to three emission components were needed to

reproduce them. One of them, associated with the giant H II region, presents supersonic widths and [N II]![]() 6584 and [S II]

6584 and [S II]

![]() 6717,6731 emission lines shifted up to 40 km s-1 with respect to H

6717,6731 emission lines shifted up to 40 km s-1 with respect to H![]() .

Similarly, one of the narrow components presents offsets in the [N II]

.

Similarly, one of the narrow components presents offsets in the [N II]![]() 6584 line of

6584 line of

![]() km s-1.

This is the first time that maps with such velocity offsets for a

starburst galaxy have been presented. The observables in the giant H II region

fit with a scenario where the two super stellar clusters (SSCs) produce

an outflow that encounters the previously quiescent gas. The south-west

part of the FLAMES IFU field is consistent with a more evolved

stage where the star clusters have already cleared out their local

environment.

km s-1.

This is the first time that maps with such velocity offsets for a

starburst galaxy have been presented. The observables in the giant H II region

fit with a scenario where the two super stellar clusters (SSCs) produce

an outflow that encounters the previously quiescent gas. The south-west

part of the FLAMES IFU field is consistent with a more evolved

stage where the star clusters have already cleared out their local

environment.

Key words: galaxies: starburst - galaxies: dwarf - galaxies: individual: NGC 5253 - galaxies: ISM - galaxies: abundances - galaxies: kinematics and dynamics

1 Introduction

Starbursts are events characterized by star-formation rates much higher than those found in gas-rich normal galaxies. They are considered one of the main contributors to the chemical enrichment of the interstellar medium (ISM) and can be found in galaxies covering a wide range of masses, luminosities, metallicities and interaction stages such as blue compact dwarfs, nuclei of spiral galaxies, or (Ultra)luminous Infrared Galaxies (see Conti et al. 2008, and references therein).

A particularly interesting subset are the H II galaxies, identified for the first time by Haro (1956): gas-rich, metal poor (

![]() )

dwarf systems characterized by the presence of large ionized H II regions that dominate their optical spectra (see Kunth & Östlin 2000,

for a review of these galaxies). These systems are a priori

simple, which makes them the ideal laboratories to test the interplay

between massive star formation and the ISM.

)

dwarf systems characterized by the presence of large ionized H II regions that dominate their optical spectra (see Kunth & Östlin 2000,

for a review of these galaxies). These systems are a priori

simple, which makes them the ideal laboratories to test the interplay

between massive star formation and the ISM.

NGC 5253, an irregular galaxy located in the Centarus A/M 83 galaxy complex (Karachentsev et al. 2007), is a local example of an H II galaxy. This galaxy is suffering a burst of star formation which is believed to have been triggered by an encounter with M 83 (van den Bergh 1980). This is supported by the existence of the H I plume extending along the optical minor axis which is best explained as tidal debris (Kobulnicky & Skillman 2008).

NGC 5253 constitutes an optimal target for the study of the starburst phenomenon. On the one hand, its proximity allows a linear spatial resolution to be achieved that is good enough to study the details of the interplay between the different components (i.e. gas, dust and star clusters) in the central region. On the other hand, this system has been observed in practically all spectral ranges from the X-ray to the radio, and therefore a large amount of ancillary information is available.

The basic characteristics of this galaxy are compiled in Table 1. Its stellar content has been widely studied and more than 300 stellar clusters have been detected (Cresci et al. 2005).

Multi-band photometry with the WFPC2 has revealed that those in its central region present typical masses of

![]()

![]()

![]() and are very young, with ages of

and are very young, with ages of

![]() Myr (e.g. Harris et al. 2004). In particular, HST-NICMOS images have revealed that the

nucleus of the galaxy is made out of two very massive (

Myr (e.g. Harris et al. 2004). In particular, HST-NICMOS images have revealed that the

nucleus of the galaxy is made out of two very massive (

![]()

![]()

![]() )

super stellar clusters (SSCs), with ages of about

)

super stellar clusters (SSCs), with ages of about ![]() Myr, separated by

Myr, separated by

![]() (Alonso-Herrero et al. 2004), and which are coincident with the double radio nebula detected at 1.3 cm (Turner et al. 2000).

Also, detection of spectral features characteristic of Wolf-Rayet (W-R)

stars in specific regions of the galaxy have been reported (e.g. Schaerer et al. 1997). Recently, seven supernova

remnants have been detected in the central region of this galaxy by means of the [Fe II]

(Alonso-Herrero et al. 2004), and which are coincident with the double radio nebula detected at 1.3 cm (Turner et al. 2000).

Also, detection of spectral features characteristic of Wolf-Rayet (W-R)

stars in specific regions of the galaxy have been reported (e.g. Schaerer et al. 1997). Recently, seven supernova

remnants have been detected in the central region of this galaxy by means of the [Fe II]![]() 1.644

1.644 ![]() m emission (Labrie & Pritchet 2006).

m emission (Labrie & Pritchet 2006).

NGC 5253 presents a filamentary structure in H![]() (e.g. Martin 1998)

associated with extended diffuse emission in X-ray which can be

explained as multiple superbubbles around its OBs associations and

SSCs that are the results of the combined action of stellar winds and

supernovae (Summers et al. 2004; Strickland & Stevens 1999).

(e.g. Martin 1998)

associated with extended diffuse emission in X-ray which can be

explained as multiple superbubbles around its OBs associations and

SSCs that are the results of the combined action of stellar winds and

supernovae (Summers et al. 2004; Strickland & Stevens 1999).

Table 1: Basic data for NGC 5253.

The measured metallicity of this galaxy is relatively low (see Table 1)

and presents a generally uniform distribution. However,

an increase in the abundance of nitrogen in the central region

of

![]() times the mean has been reported (Walsh & Roy 1989; López-Sánchez et al. 2007; Kobulnicky et al. 1997).

No other elemental species appears to present spatial abundance

fluctuations. The reason for this nitrogen enhancement has not

been fully clarified yet although a connection with the

W-R population has been suggested.

times the mean has been reported (Walsh & Roy 1989; López-Sánchez et al. 2007; Kobulnicky et al. 1997).

No other elemental species appears to present spatial abundance

fluctuations. The reason for this nitrogen enhancement has not

been fully clarified yet although a connection with the

W-R population has been suggested.

On account of their irregular structure, a proper characterization of the physical properties of H II galaxies, necessary to explore the interplay of mechanisms acting between gas and stars, requires high quality two-dimensional spectral information able to produce a continuous mapping of the relevant quantities. Such observations have traditionally been done in the optical and near-infrared by mapping the galaxy under study with a long-slit (e.g. Walsh & Roy 1989; Vílchez & Iglesias-Páramo 1998). This is, however, expensive in terms of telescope time and might be affected by some technical problems such as misalignment of the slit or changes in the observing conditions with time. The advent and popularization of integral field spectroscopy (IFS) facilities, able to record simultaneously the spectra of an extended continuous field, overcomes these difficulties. Nevertheless, work based on this technique devoted to the study of H II galaxies is still relatively rare (e.g. Bordalo et al. 2009; Lagos et al. 2009; James et al. 2009; Izotov et al. 2006; Kehrig et al. 2008; García-Lorenzo et al. 2008).

Here, we present IFS observations of the central area of NGC 5253 in order to study the mechanisms that govern the interaction between the young stars and the surrounding ionized gas. The paper is organized as follows: Sect. 2 contains the observational and technical details regarding the data reduction and derivation of the required observables; Sect. 3 describes the stellar and ionized gas structure as well as the extinction distribution and the physical and kinematic properties of the ionized gas; Sect. 4 discusses the evolutionary stage of the gas surrounding the stellar clusters, focusing on the two most relevant areas of the field of view (f.o.v.). Section 5 itemises our results and conclusions.

2 Observations, data reduction and line fitting

2.1 Observations

Data were obtained with the Fibre Large Array Multi Element Spectrograph, FLAMES (Pasquini et al. 2002)

at Kueyen, Telescope Unit 2 of the 8 m VLT at ESO's

observatory on Paranal, on February 10, 2007. The central

region of the galaxy was observed with the ARGUS Integral Field Unit

(IFU) which has a field of view of

![]()

![]()

![]() with a sampling of 0.52

with a sampling of 0.52

![]() /lens.

In addition, ARGUS has 15 fibers that can simultaneously

observe the sky and which were arranged forming a circle around the

IFU. The precise covered area is shown in Fig. 1 which contains the FLAMES field of view over-plotted on an HST B, H

/lens.

In addition, ARGUS has 15 fibers that can simultaneously

observe the sky and which were arranged forming a circle around the

IFU. The precise covered area is shown in Fig. 1 which contains the FLAMES field of view over-plotted on an HST B, H![]() ,

I colour image.

,

I colour image.

We utilized two different gratings in order to obtain information for

the most important emission lines in the optical spectral range. Data

were taken under photometric conditions and seeing ranged typically

between

![]() and

and

![]() .

The covered spectral range, resolving power, exposure time and airmass for each configuration are shown in Table 2.

In addition

to the science frames, continuum and ThAr arc lamps exposures

as well as frames for the spectrophotometric standard star

CD-32 9927 were obtained.

.

The covered spectral range, resolving power, exposure time and airmass for each configuration are shown in Table 2.

In addition

to the science frames, continuum and ThAr arc lamps exposures

as well as frames for the spectrophotometric standard star

CD-32 9927 were obtained.

2.2 Data reduction

The basic reduction steps for the FLAMES data were performed with a

combination of the pipeline provided by ESO (version 1.0)![]() via esorex, version 2.0.2 and some IRAF

via esorex, version 2.0.2 and some IRAF![]() routines. First of all we masked a bad column in the raw data using the task fixpix

within IRAF. Then, each individual frame was processed using the

ESO pipeline in order to perform bias subtraction, spectral

tracing and extraction, wavelength calibration and correction of fibre

transmission.

routines. First of all we masked a bad column in the raw data using the task fixpix

within IRAF. Then, each individual frame was processed using the

ESO pipeline in order to perform bias subtraction, spectral

tracing and extraction, wavelength calibration and correction of fibre

transmission.

Uncertainties in the relative wavelength calibration were estimated by

fitting a Gaussian to three isolated lines in every spectrum of

the arc exposure. The standard deviation of the central wavelength

for a certain line gives an idea of the associated error in that

spectral range. We were able to determine the centroid of the lines

with an uncertainty of ![]() 0.005 Å, which translates into velocities of

0.005 Å, which translates into velocities of ![]() 0.3 km s-1. The spectral resolution was very uniform over the whole field-of-view with values of 0.178

0.3 km s-1. The spectral resolution was very uniform over the whole field-of-view with values of 0.178 ![]() 0.004 Å and 0.241

0.004 Å and 0.241 ![]() 0.009 Å, FWHM for the blue and red configuration respectively, which translates into

0.009 Å, FWHM for the blue and red configuration respectively, which translates into

![]()

![]() 4.7 km s-1.

4.7 km s-1.

For the sky subtraction, we created a good signal-to-noise (S/N)

spectrum by averaging the spectra of the sky fibres in each individual

frame. This sky spectrum was subsequently subtracted from every

spectrum. In several of the sky fibres, the strongest emission

lines, namely [O III]![]() 5007 in the blue

frames and H

5007 in the blue

frames and H![]() in the red frames, could clearly be detected. We attributed this effect

to some cross-talk from the adjacent fibers. A direct comparison

of the flux in the sky and adjacent fibers showed that this

contribution was always

in the red frames, could clearly be detected. We attributed this effect

to some cross-talk from the adjacent fibers. A direct comparison

of the flux in the sky and adjacent fibers showed that this

contribution was always ![]() 0.6%

which is negligible in terms of sky subtraction. However, in order

to reduce this contamination to a minimum, we decided not to use these

fibres in the creation of the high S/N sky spectra.

0.6%

which is negligible in terms of sky subtraction. However, in order

to reduce this contamination to a minimum, we decided not to use these

fibres in the creation of the high S/N sky spectra.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{14154fg1.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/09/aa14154-10/Timg58.png)

|

Figure 1:

False colour image in filters F435W (B, blue), F658N (

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

Table 2: Observation log.

Regarding the flux calibration, a spectrum for the calibration star was created by co-adding all the fibers of the standard star frames. Then, a sensitivity function was determined with the IRAF tasks standard and sensfunc and science frames were calibrated with calibrate. Afterwards, frames corresponding to each configuration were combined and cosmic rays rejected with the task imcombine. As a last step, the data were reformatted into two easier-to-use data cubes, with two spatial and one spectral dimension, using the known position of the lenses within the array.

2.3 Line fitting and map creation

In order to obtain the relevant emission line information, line

profiles were fitted using Gaussian functions. This procedure was done

in a semi-automatic way using the IDL based routine MPFITEXPR![]() (Markwardt 2009)

which offers ample flexibility in case constraints on the parameters of

the fit are included, such as lines in fixed ratio. The procedure was

as follows.

(Markwardt 2009)

which offers ample flexibility in case constraints on the parameters of

the fit are included, such as lines in fixed ratio. The procedure was

as follows.

As a first step, we fit all the lines by a single Gaussian. The H![]() +[N II] complex

was fitted simultaneously by one Gaussian per emission line plus a flat

continuum first-degree

polynomial using a common width for the three lines and fixing the

separation in wavelength between the lines according to the redshift

provided at NED

+[N II] complex

was fitted simultaneously by one Gaussian per emission line plus a flat

continuum first-degree

polynomial using a common width for the three lines and fixing the

separation in wavelength between the lines according to the redshift

provided at NED![]() and the nitrogen line ratio (

and the nitrogen line ratio (![]() 6583/

6583/![]() 6548) to 3. The same procedure was repeated for the [S II]

6548) to 3. The same procedure was repeated for the [S II]

![]() 6717, 6730 doublet, the [Ar IV]

6717, 6730 doublet, the [Ar IV]![]() 4711 line (which was fitted jointly with the [Fe III]

4711 line (which was fitted jointly with the [Fe III]![]() 4701 and He I

4701 and He I![]() 4713) and the [Ar IV]

4713) and the [Ar IV]![]() 4740 line (which was fitted jointly with the [Fe III]

4740 line (which was fitted jointly with the [Fe III]![]() 4734 line), but this time without any restriction on the line ratios. Finally, H

4734 line), but this time without any restriction on the line ratios. Finally, H![]() ,

[O III]

,

[O III]![]() 5007, and He I

5007, and He I![]() 6678 were individually fitted.

6678 were individually fitted.

This single Gaussian fit gave a good measurement for the line fluxes

and the results of these fits are the used in all the forthcoming

analysis, with the exception of the kinematics. This latter analysis

requires a more complex line fitting scheme, since several lines showed

signs of asymmetries and/or multiple components in their profiles for a

large number of spaxels. In those

cases, multi-component fits were performed. Over the whole field

of view we compared the measured flux from performing the fit with a

single Gaussian to the fit by several components in the brightest

emission lines (namely: H![]() ,

[O III]

,

[O III]![]() 5007, H

5007, H![]() ,

[N II]

,

[N II]![]() 6584 and [S II]

6584 and [S II]

![]() 6717,6731).

Differences between the two sets of line fluxes ranged typically

from 0% to 15%, depending on the spaxel and the emission

line, and translated into differences in the line ratios

6717,6731).

Differences between the two sets of line fluxes ranged typically

from 0% to 15%, depending on the spaxel and the emission

line, and translated into differences in the line ratios ![]() 0.06 dex.

0.06 dex.

In all the cases, MPFITEXPR estimated an error for the fit using the standard deviation of the adjacent continuum. Those fits with a ratio between line flux and error less than three were automatically rejected. The remaining spectra were visually inspected and classified as good or bad fits.

Finally, for each of the observables, we used the derived quantity together with the position within the data-cube for each spaxel to create an image suitable to be manipulated with standard astronomical software. Hereafter, we will use both terms, map and image, when referring to these.

3 Results

3.1 Stellar and ionized gas structure

Figure 2 displays the stellar structure, as traced by a continuum close to H![]() ,

as well as the one for the ionized gas (traced by the H

,

as well as the one for the ionized gas (traced by the H![]() emission line). The over-plotted contours, which represent the HST-ACS images in the F659N and F814W bands

convolved with a Gaussian to match the seeing at Paranal, show

good correspondence between the images created from the IFS data

and the HST images (although obviously with poorer resolution for

the ground-based

FLAMES data). A direct comparison of these maps shows how the

stellar and ionized gas structure differs.

emission line). The over-plotted contours, which represent the HST-ACS images in the F659N and F814W bands

convolved with a Gaussian to match the seeing at Paranal, show

good correspondence between the images created from the IFS data

and the HST images (although obviously with poorer resolution for

the ground-based

FLAMES data). A direct comparison of these maps shows how the

stellar and ionized gas structure differs.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{14154fg2a.ps}\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{14154fg2b.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/09/aa14154-10/Timg61.png)

|

Figure 2:

Top: stellar component distribution as traced by a continuum map made from the average flux in the spectral range

6525-6545 Å and

6600-6620 Å. Bottom: ionized gas distribution as traced by the H |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Table 3: Main reference clusters.

The continuum image displays three main peaks of emission which will be

used through the paper as reference. We have associated each of these

peaks with one or more star clusters by direct comparison with

ACS images. Table 3

compiles their positions within the FLAMES field of view together with

the names of the corresponding clusters according to several reference

works. These clusters trace a sequence in age as we move towards the

right (south-west) in the FLAMES field of view. The clusters associated

with peak #1 are very young (

![]() Myr, Alonso-Herrero et al. 2004; Harris et al. 2004), those associated with peak #2 display a range of ages from very young to intermediate age (

Myr, Alonso-Herrero et al. 2004; Harris et al. 2004), those associated with peak #2 display a range of ages from very young to intermediate age (

![]() Myr, Harris et al. 2004), while the stars in the pair of clusters associated with peak #3 seem to have intermediate ages (70-113 Myr, Harris et al. 2004).

Myr, Harris et al. 2004), while the stars in the pair of clusters associated with peak #3 seem to have intermediate ages (70-113 Myr, Harris et al. 2004).

The H![]() emission line reproduces the structure described by Calzetti et al. (1997)

using an HST WFPC2 image. Briefly, the central region of

NGC 5253 is divided into two parts by a dust lane that crosses the

galaxy along the east-west direction (from

emission line reproduces the structure described by Calzetti et al. (1997)

using an HST WFPC2 image. Briefly, the central region of

NGC 5253 is divided into two parts by a dust lane that crosses the

galaxy along the east-west direction (from ![]() [2

[2

![]() 0, -3

0, -3

![]() 0]

0]![]() to the Complex #3). Most of the H

to the Complex #3). Most of the H![]() emission is located towards the north of this lane where there is giant H II region

associated with the Complex #1. This region shows two

tongue-shaped extensions towards the upper and lower part of the

FLAMES field of view (PA on the sky of

emission is located towards the north of this lane where there is giant H II region

associated with the Complex #1. This region shows two

tongue-shaped extensions towards the upper and lower part of the

FLAMES field of view (PA on the sky of

![]() and

and

![]() ,

respectively) as well as a extension at PA

,

respectively) as well as a extension at PA ![]()

![]() which contains the Complex #2. Towards the south of the dust lane, the emission is dominated by a peak at

which contains the Complex #2. Towards the south of the dust lane, the emission is dominated by a peak at ![]() [-3

[-3

![]() 5, -2

5, -2

![]() 5] which could be associated with cluster 17 in Harris et al. (2004).

5] which could be associated with cluster 17 in Harris et al. (2004).

3.2 Extinction structure

Extinction was derived assuming an intrinsic Balmer emission line ratio of H![]() /H

/H![]() = 2.87 (Osterbrock & Ferland 2006, for an

= 2.87 (Osterbrock & Ferland 2006, for an

![]() K) and using the extinction curve of Fluks et al. (1994). Since the H

K) and using the extinction curve of Fluks et al. (1994). Since the H![]() and H

and H![]() emission lines are separated by

emission lines are separated by ![]() 1700 Å

and both of them had high signal-to-noise ratio in only a single

exposure, we decided to obtain the extinction maps from the LR3 and

LR6 exposures observed at the smallest airmass

(1.009 and 1.160, respectively), thus minimizing any effect

due to differential atmospheric refraction.

1700 Å

and both of them had high signal-to-noise ratio in only a single

exposure, we decided to obtain the extinction maps from the LR3 and

LR6 exposures observed at the smallest airmass

(1.009 and 1.160, respectively), thus minimizing any effect

due to differential atmospheric refraction.

We have not included any correction for an underlying stellar

population. We inspected carefully each individual spectrum to look for

the presence of the stellar absorption feature in H![]() .

Only in those spaxels associated with the area around the Complex #3 (

.

Only in those spaxels associated with the area around the Complex #3 (![]() 9-10 spaxels or

9-10 spaxels or ![]() 1

1

![]() 5

5 ![]() 1

1

![]() 5

in total) was such an absorption detected. We estimated the

influence of this component by fitting both the absorption and the

emission component in the most

affected spaxel. Equivalent widths were

5

in total) was such an absorption detected. We estimated the

influence of this component by fitting both the absorption and the

emission component in the most

affected spaxel. Equivalent widths were ![]() 3 and

3 and ![]() 9 Å, respectively. In these spaxels, the absorption line was typically

9 Å, respectively. In these spaxels, the absorption line was typically

![]() times wider and with about half - one third of the flux of the emission line. This implies an underestimation of H

times wider and with about half - one third of the flux of the emission line. This implies an underestimation of H![]() emission

line flux of about 10%. For the particular area around

Complex #3, this translates into a real extinction of

emission

line flux of about 10%. For the particular area around

Complex #3, this translates into a real extinction of

![]() mag instead of the measured

mag instead of the measured

![]() mag.

mag.

The corresponding reddening map was determined assuming E(B-V) = AV / 3.1 (Rieke & Lebofsky 1985) and is presented in Fig. 3. This map shows that the extinction is distributed in a non-uniform manner ranging from E(B-V) = 0.16 to 0.64 (mean 0.33, standard deviation, 0.07). Given that Galactic reddening for NGC 5253 is 0.056 (Schlegel et al. 1998), nearly all of the extinction can be considered intrinsic to the galaxy.

In general terms, the structure presented in this map coincides with the one presented by Calzetti et al. (1997). The dust lane mentioned in the previous section is clearly visible here and it causes extinction of AV ![]() 0.10-1.13 mag. However, the larger measured extinction values are associated with the giant H II region, in agreement with the H I distribution (Kobulnicky & Skillman 2008). Dust in this area forms an S-shaped distribution with

0.10-1.13 mag. However, the larger measured extinction values are associated with the giant H II region, in agreement with the H I distribution (Kobulnicky & Skillman 2008). Dust in this area forms an S-shaped distribution with

![]() mag in the arms.

mag in the arms.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{14154fg3.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/09/aa14154-10/Timg72.png)

|

Figure 3:

Reddening map obtained from the hydrogen recombination lines assuming H |

| Open with DEXTER | |

In order to explore the relation between the extinction suffered by the gas and by the stellar populations, our E(B-V) measurements

were compared with colours defined ad hoc. For the covered

spectral range, it is not possible to exactly simulate any of the

existing standard filters. It is possible, however, to create

filters relatively similar to the

![]() and

and ![]() ones. We have simulated two set of filters.

ones. We have simulated two set of filters.

In the first case, the flux was integrated over two large

wavelength ranges (465-495 nm and 643-673 nm) in order to

simulate broad filters. The relation between the reddening derived for

the ionized gas and the derived colour, hereafter

![]() ,

is shown in the upper panel of Fig. 4,

as would be observed with photometry. The first order polynomial

fit to the data and the Pearson correlation coefficient are included on

the plot. Also shown is the expected relation for an Im galaxy

with foreground reddening. This latter was derived for the average of

two Im templates (NGC 4449 and NGC 4485) from Kennicutt (1992) applying a foreground screen of dust with a standard Galactic reddening law (Cardelli et al. 1989) with R=3.1.

There is a strong difference between the expected relation for a

foreground screen of dust and the measured values. On the one hand,

colours are much redder. On the other hand, the slope of the

1-degree polynomial fit is much less steep than the expected one.

Also, there is a very good correlation between the E(B-V) and our synthetic

,

is shown in the upper panel of Fig. 4,

as would be observed with photometry. The first order polynomial

fit to the data and the Pearson correlation coefficient are included on

the plot. Also shown is the expected relation for an Im galaxy

with foreground reddening. This latter was derived for the average of

two Im templates (NGC 4449 and NGC 4485) from Kennicutt (1992) applying a foreground screen of dust with a standard Galactic reddening law (Cardelli et al. 1989) with R=3.1.

There is a strong difference between the expected relation for a

foreground screen of dust and the measured values. On the one hand,

colours are much redder. On the other hand, the slope of the

1-degree polynomial fit is much less steep than the expected one.

Also, there is a very good correlation between the E(B-V) and our synthetic

![]() colour. All this can be attributed to the contamination of the gas emission lines, mainly H

colour. All this can be attributed to the contamination of the gas emission lines, mainly H![]() and H

and H![]() ,

in our filters.

,

in our filters.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=7.5cm,clip]{14154fg4a.ps}\par\includegraphics[width=7.5cm,clip]{14154fg4b.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/09/aa14154-10/Timg77.png)

|

Figure 4:

Relation between the derived reddening and a colour similar to

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{14154fg5.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/09/aa14154-10/Timg78.png)

|

Figure 5: Line free colour map. The simulated filters have been defined as explained in Fig. 4. The position of the three main peaks of continuum emission are shown for reference. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

In the second set, we restricted the spectral ranges for the simulated

filters to a narrower wavelength range which was free from the

contamination of the main emission lines. The map for this line-free

colour is displayed in Fig. 5. The structure resembles the one presented in Fig. 3 (i.e. dust lane, redder colours associated with the giant H II region),

although there are differences, that can be attributed to differences

in the properties of the stellar populations in the different clusters.

The relation between the reddening and the corresponding

![]() is shown in the lower panel of Fig. 4.

This time colours are more similar to what is expected for a given

stellar population suffering a certain amount of extinction. However,

for a given colour, stars do not reach the expected reddening

if gas and stars were suffering the same extinction (i.e. data

points are below the green line). The ratio between the slopes indicates that extinction in the stars is

a factor 0.33 lower than the one for the ionized gas. This is similar to what Calzetti et al. (1997)

found using HST images who estimated that the extinction suffered

by the stars is a factor 0.5 lower than for the ionized gas and

can be explained if the dust has a larger covering factor for the

ionized gas than for the stars (Calzetti et al. 1994).

is shown in the lower panel of Fig. 4.

This time colours are more similar to what is expected for a given

stellar population suffering a certain amount of extinction. However,

for a given colour, stars do not reach the expected reddening

if gas and stars were suffering the same extinction (i.e. data

points are below the green line). The ratio between the slopes indicates that extinction in the stars is

a factor 0.33 lower than the one for the ionized gas. This is similar to what Calzetti et al. (1997)

found using HST images who estimated that the extinction suffered

by the stars is a factor 0.5 lower than for the ionized gas and

can be explained if the dust has a larger covering factor for the

ionized gas than for the stars (Calzetti et al. 1994).

In general, our E(B-V) measurements agree with previous ones using the same emission lines in specific areas (e.g. López-Sánchez et al. 2007; González-Riestra et al. 1987) or with poorer spatial resolution (Walsh & Roy 1989).

However there are discrepancies when comparing with the estimation of

the extinction at other wavelengths. In particular, the peak

of extinction (AV = 2.1 mag, according to the Balmer line ratio) is offset by

![]() from the peak of continuum emission. Alonso-Herrero et al. (2004)

showed how in the central area of NGC 5253 there are two massive

star clusters, C1 and C2. While C1 is the dominant

source in the optical, coincident with our peak in the continuum map,

the more massive and extinguished C2 is the dominant source in the

infrared. The contours for the NICMOS

from the peak of continuum emission. Alonso-Herrero et al. (2004)

showed how in the central area of NGC 5253 there are two massive

star clusters, C1 and C2. While C1 is the dominant

source in the optical, coincident with our peak in the continuum map,

the more massive and extinguished C2 is the dominant source in the

infrared. The contours for the NICMOS ![]() image in Fig. 3

show the good correspondence between our maximum of extinction

and C2. Measurements in the near and mid-infrared suggest

extinctions of

image in Fig. 3

show the good correspondence between our maximum of extinction

and C2. Measurements in the near and mid-infrared suggest

extinctions of

![]() mag for this cluster (Martín-Hernández et al. 2005; Turner et al. 2003; Alonso-Herrero et al. 2004).

The discrepancy between these two values indicates that a foreground

screen model is not the appropriate one to explain the distribution of

the dust in the giant H II region.

mag for this cluster (Martín-Hernández et al. 2005; Turner et al. 2003; Alonso-Herrero et al. 2004).

The discrepancy between these two values indicates that a foreground

screen model is not the appropriate one to explain the distribution of

the dust in the giant H II region.

3.3 Electron density distribution

Electron density (![]() )

can be determined from the [S II]

)

can be determined from the [S II]![]() 6717/ [S II]

6717/ [S II]![]() 6731 and [Ar IV]

6731 and [Ar IV]![]() 4711/[Ar IV]

4711/[Ar IV]![]() 4740 line

ratios; values of 1.25 and 1.00 respectively were measured in

a spectrum made from the sum of all our spaxels. Hereafter, we will

refer to this spectrum as the integrated spectrum. Electron densities were determined assuming an electron temperature of 11 650 K, the average of the values given in López-Sánchez et al. (2007), and using the task temden, based on the fivel program (Shaw & Dufour 1995) included in the IRAF package nebular. Derived values of

4740 line

ratios; values of 1.25 and 1.00 respectively were measured in

a spectrum made from the sum of all our spaxels. Hereafter, we will

refer to this spectrum as the integrated spectrum. Electron densities were determined assuming an electron temperature of 11 650 K, the average of the values given in López-Sánchez et al. (2007), and using the task temden, based on the fivel program (Shaw & Dufour 1995) included in the IRAF package nebular. Derived values of ![]() for the two line ratios were 180 cm-3 and 4520 cm-3,

respectively. Differences between the electron densities derived from

the argon and sulphur lines are usually found in ionized gaseous

nebulae (see Wang et al. 2004) and are understood in terms of the ionization structure of the nebulae under study: [Ar IV] lines normally come from inner regions of higher ionization degree than [S II] lines. Typically, for giant Galactic and extragalactic H II regions, derived

for the two line ratios were 180 cm-3 and 4520 cm-3,

respectively. Differences between the electron densities derived from

the argon and sulphur lines are usually found in ionized gaseous

nebulae (see Wang et al. 2004) and are understood in terms of the ionization structure of the nebulae under study: [Ar IV] lines normally come from inner regions of higher ionization degree than [S II] lines. Typically, for giant Galactic and extragalactic H II regions, derived ![]() from these two line ratios differ in a factor of

from these two line ratios differ in a factor of ![]() 5 (e.g. Tsamis et al. 2003; Esteban et al. 2002) which is much lower than what we find for the integrated spectrum of NGC 5253 (

5 (e.g. Tsamis et al. 2003; Esteban et al. 2002) which is much lower than what we find for the integrated spectrum of NGC 5253 (![]() 25). However, when only the giant H II region is taken into account (i.e. the area of

25). However, when only the giant H II region is taken into account (i.e. the area of ![]() 90 spaxels

where the argon lines are detected) the difference between the

densities derived from the argon and the sulphur lines (

90 spaxels

where the argon lines are detected) the difference between the

densities derived from the argon and the sulphur lines (![]() 10, see typical values for the densities below) is more similar to those found for other H II regions.

10, see typical values for the densities below) is more similar to those found for other H II regions.

Maps for both ratios are shown in Fig. 6.

According to the sulphur line ratio - detected over the whole

field - densities range from very low values, of the order of

the low density limit, in a region of about

![]()

![]()

![]() in the upper right corner of the field just above the Complex #3, to 790 cm -3 at the peak of the emission in the cluster associated with the H II region, with a mean (median) over the field of view of

in the upper right corner of the field just above the Complex #3, to 790 cm -3 at the peak of the emission in the cluster associated with the H II region, with a mean (median) over the field of view of

![]() cm-3. The rest of the H II regions still present high densities (of about 400 cm-3 as a whole, 480 cm-3 in the H II-2, (i.e. the upper area of the giant H II region, Kobulnicky et al. 1997). This agrees well with the value estimated from long-slit measurements (López-Sánchez et al. 2007). The tail and the region associated with the cluster UV-1 present intermediate values (of about 200 cm-3).

cm-3. The rest of the H II regions still present high densities (of about 400 cm-3 as a whole, 480 cm-3 in the H II-2, (i.e. the upper area of the giant H II region, Kobulnicky et al. 1997). This agrees well with the value estimated from long-slit measurements (López-Sánchez et al. 2007). The tail and the region associated with the cluster UV-1 present intermediate values (of about 200 cm-3).

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{14154fg6a.ps}\vspace*{3mm}

\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{14154fg6b.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/09/aa14154-10/Timg85.png)

|

Figure 6: Maps for the line ratios sensitive to the electron density. The position of the three main peaks of continuum emission are shown as crosses for reference. The displayed ranges in the line ratios imply electron densities of <10-790 cm-3 and 190-8750 cm-3 for the sulphur and argon line ratio, respectively. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

The argon line ratio is used to sample the densest regions.

The map for this ratio was somewhat noisier and allowed an

estimation of the electron density only in the giant H II region.

The densities derived from this line ratio are comparatively higher,

with a mean (median) of 3400 (3150) cm-3.

As it happened in the case of the extinction, the peak of

electron density according to this line ratio is offset by

![]() towards the north-west with respect of the peak of continuum emission at Complex #1.

towards the north-west with respect of the peak of continuum emission at Complex #1.

We created higher S/N ratio spectra by co-addition of 3 ![]() 3 spaxel

apertures associated with certain characteristic regions (i.e. the

clusters at the core of the systems, C1+C2, and the regions H II-2, H II-1 and UV-1 of Kobulnicky et al. 1997).

The largest values are measured around the core (i.e. C1+C2)

where the [Ar IV] electron density can be as high

as 6200 cm -3. As we move further away from this region, the measured electron density becomes lower. Thus, H II-2 presents similar, although slightly lower, densities (

3 spaxel

apertures associated with certain characteristic regions (i.e. the

clusters at the core of the systems, C1+C2, and the regions H II-2, H II-1 and UV-1 of Kobulnicky et al. 1997).

The largest values are measured around the core (i.e. C1+C2)

where the [Ar IV] electron density can be as high

as 6200 cm -3. As we move further away from this region, the measured electron density becomes lower. Thus, H II-2 presents similar, although slightly lower, densities (

![]() cm-3), followed by H II-1 with

cm-3), followed by H II-1 with

![]() cm-3 and UV1 with

cm-3 and UV1 with

![]() cm-3. These values agree, within the errors, with those reported in López-Sánchez et al. (2007) for similar apertures.

cm-3. These values agree, within the errors, with those reported in López-Sánchez et al. (2007) for similar apertures.

An interesting point arises when the different density values derived

for the integrated spectrum and for each individual spaxel/aperture are

compared (180 cm-3, and up to 790 cm-3,

respectively when using the sulphur line ratio). The covered f.o.v. (![]() 210 pc

210 pc ![]() 135 pc) is comparable to the linear scales that one can resolve from the ground at distances of

135 pc) is comparable to the linear scales that one can resolve from the ground at distances of ![]() 40 Mpc (or

40 Mpc (or ![]() ).

Such a comparison illustrates how aperture effects can cause

important underestimation of the electron density in the H II regions in starbursts at such distances, or further away.

).

Such a comparison illustrates how aperture effects can cause

important underestimation of the electron density in the H II regions in starbursts at such distances, or further away.

3.4 Ionization structure, excitation sources and nitrogen enhancement

The ionization structure of the interstellar medium can be studied by

means of diagnostic diagrams. Different areas of a given diagram are

explained by different ionization mechanisms. In the optical

spectral range, the most widely used are probably those proposed

by Baldwin et al. (1981) and later reviewed

by Veilleux & Osterbrock (1987), the so-called BPT diagrams. In Fig. 7 the maps for the three available line ratios involved in these diagrams - namely [N II]![]() 6584/H

6584/H![]() ,

[S II]

,

[S II]

![]() 6717, 6731/H

6717, 6731/H![]() ,

[O III]

,

[O III]![]() 5007/H

5007/H![]() -

are shown on a logarithmic scale. This figure shows that the ionization

structure in the central region of this galaxy is complex.

Not only do the line ratios not show a uniform distribution, but

the structure changes depending on the particular line ratio.

-

are shown on a logarithmic scale. This figure shows that the ionization

structure in the central region of this galaxy is complex.

Not only do the line ratios not show a uniform distribution, but

the structure changes depending on the particular line ratio.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{14154fg7a.ps}\vspace*{3mm}

\...

...*{3mm}

\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{14154fg7c.ps}

\vspace*{5mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/09/aa14154-10/Timg92.png)

|

Figure 7:

Emission line ratio maps. Up: |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=7.5cm,clip]{14154fg8.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/09/aa14154-10/Timg93.png)

|

Figure 8:

Position of the individual spaxels in NGC 5253 in the diagnostic diagrams

proposed by Veilleux & Osterbrock (1987). Data points above and below the 3- |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Both the [O III]![]() 5007/H

5007/H![]() and the [S II]

and the [S II]

![]() 6717,6731/H

6717,6731/H![]() line ratios display a gradient away from the peak of emission at

Complex #1 and with a structure that follows that of the ionized

gas. Thus the [S II]

line ratios display a gradient away from the peak of emission at

Complex #1 and with a structure that follows that of the ionized

gas. Thus the [S II]

![]() 6717,6731/H

6717,6731/H![]() ([O III]

([O III]![]() 5007/H

5007/H![]() ) ratio is smallest (largest) at Complex #1, presents somewhat intermediate values in the two tongue-shaped

extensions and the Complex #2 and is relatively high (low) in the rest of the field, with a

secondary minimum (maximum) at

) ratio is smallest (largest) at Complex #1, presents somewhat intermediate values in the two tongue-shaped

extensions and the Complex #2 and is relatively high (low) in the rest of the field, with a

secondary minimum (maximum) at

![]() ,

the position of a secondary peak in the H

,

the position of a secondary peak in the H![]() emission. This is coincident with the structure presented in (Calzetti et al. 2004).

emission. This is coincident with the structure presented in (Calzetti et al. 2004).

The [N II]![]() 6584/H

6584/H![]() line ratio, however, display a different structure. While in the right

half of the FLAMES field of view, the behavior is quite similar to

the one observed for the [S II]

line ratio, however, display a different structure. While in the right

half of the FLAMES field of view, the behavior is quite similar to

the one observed for the [S II]

![]() 6717,6731/H

6717,6731/H![]() ratio (i.e. values relatively high, local minimum at

ratio (i.e. values relatively high, local minimum at

![]() ), the left half, dominated by the giant H II region,

displays a completely different pattern. The lowest values are

associated with Complex #2 and the southern extension, rather than

Complex #1, and the [N II]

), the left half, dominated by the giant H II region,

displays a completely different pattern. The lowest values are

associated with Complex #2 and the southern extension, rather than

Complex #1, and the [N II]![]() 6584/H

6584/H![]() line ratios are highest at

line ratios are highest at

![]() .

.

In Fig. 8 we show

the position of each spaxel of the FLAMES field of view,

as well as for the integrated spectrum, after co-adding all the

spaxels in the BPT diagnostic diagrams together with the borders

that separate H II region-like ionization from ionization by other mechanisms according to several authors (Kewley et al. 2001; Veilleux & Osterbrock 1987; Stasinska et al. 2006; Kauffmann et al. 2003). We also show the

predictions for models of photo-ionization caused by stars (Dopita et al. 2006) that take into account the effect of the stellar winds on the dynamical evolution of the region. In these models, the

ionization parameter is replaced by a new variable R that depends on the mass of the ionizing cluster and the pressure of the interstellar medium (R = (

![]() /

/![]() )/(Po/k), with Po/k measured in cm3 K).

Also, the predictions for shocks models for a LMC metallicity are

included. Given the relatively low metallicity of NGC 5253, these

are the most appropriate

ones. They were calculated assuming a

)/(Po/k), with Po/k measured in cm3 K).

Also, the predictions for shocks models for a LMC metallicity are

included. Given the relatively low metallicity of NGC 5253, these

are the most appropriate

ones. They were calculated assuming a

![]() cm-3 and cover an ample range of magnetic parameters, B, and shock velocities,

cm-3 and cover an ample range of magnetic parameters, B, and shock velocities, ![]() ,

(see Allen et al. 2008, for details).

,

(see Allen et al. 2008, for details).

As demonstrated for the electron density, these diagrams

illustrate very clearly how resolution effects can influence the

measured line ratios. Values derived for individual spaxels cover a

range of ![]() 0.5, 1.0 and 0.5 dex for the [N II]

0.5, 1.0 and 0.5 dex for the [N II]![]() 6584/H

6584/H![]() ,

[S II]

,

[S II]

![]() 6717,6731/H

6717,6731/H![]() ,

and [O III]

,

and [O III]![]() 5007/H

5007/H![]() line

ratios respectively, with mean values similar to the integrated

values (-1.15, 0.92, and 0.74). This is particularly

relevant when interpreting the ionization mechanisms in galaxies at

larger distances where the spectrum can sample a region with a range in

ionization properties. This loss of spatial resolution thus ``smears''

the determination of the ionization mechanism by a set of line ratios.

Even if this given set of line ratios is typical of photoionization

caused by stars, it is not possible to exclude some

contribution due to other mechanisms at scales unresolved by the

particular observations.

line

ratios respectively, with mean values similar to the integrated

values (-1.15, 0.92, and 0.74). This is particularly

relevant when interpreting the ionization mechanisms in galaxies at

larger distances where the spectrum can sample a region with a range in

ionization properties. This loss of spatial resolution thus ``smears''

the determination of the ionization mechanism by a set of line ratios.

Even if this given set of line ratios is typical of photoionization

caused by stars, it is not possible to exclude some

contribution due to other mechanisms at scales unresolved by the

particular observations.

Regarding the individual measurements, although all line ratios are within the typical values expected for an H II region-like

ionization, two differences between these diagrams arise. The first one

is that the diagram involving the [S II]

![]() 6717,6731/H

6717,6731/H![]() line ratio indicates a somewhat higher ionization degree than the one involving the [N II]

line ratio indicates a somewhat higher ionization degree than the one involving the [N II]![]() 6584/H

6584/H![]() line ratio. That is: values for the diagram involving the [S II]

line ratio. That is: values for the diagram involving the [S II]

![]() 6717,6731/H

6717,6731/H![]() line ratio are at the limit of what can be explained by pure photo-ionization in an H II region according to the Kewley et al. (2001) theoretical borders. On the contrary, most of the data points in the diagram involving the [N II]

line ratio are at the limit of what can be explained by pure photo-ionization in an H II region according to the Kewley et al. (2001) theoretical borders. On the contrary, most of the data points in the diagram involving the [N II]![]() 6584/H

6584/H![]() are clearly in the area associated to photoionization caused by stars.

A comparison with the predictions of the models for metallicities

similar to the one of NGC 5253 shows how the measured

line ratios present intermediate values between those predicted by

ionization caused by shocks and those by pure stellar photoionization.

That this is exactly what one would expect if shocks caused by the

mechanical input from stellar winds or supernovae within the starburst

were contributing to the observed spectra. Also, this comparison

supports previous studies that show how models of photoionization

caused by stars underpredict the [O III]

are clearly in the area associated to photoionization caused by stars.

A comparison with the predictions of the models for metallicities

similar to the one of NGC 5253 shows how the measured

line ratios present intermediate values between those predicted by

ionization caused by shocks and those by pure stellar photoionization.

That this is exactly what one would expect if shocks caused by the

mechanical input from stellar winds or supernovae within the starburst

were contributing to the observed spectra. Also, this comparison

supports previous studies that show how models of photoionization

caused by stars underpredict the [O III]![]() 5007/H

5007/H![]() line ratios, specially in the low-metallicity cases (Brinchmann et al. 2008; Dopita et al. 2006).

line ratios, specially in the low-metallicity cases (Brinchmann et al. 2008; Dopita et al. 2006).

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{14154fg9.ps}

\vspace*{1mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/09/aa14154-10/Timg101.png)

|

Figure 9:

[S II]

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

The second diference is the distribution of the data points in these diagrams. While the data points in the [S II]

![]() 6717,6731/H

6717,6731/H![]() vs. [O III]

vs. [O III]![]() 5007/H

5007/H![]() diagram form a sequence, data points in the [N II]

diagram form a sequence, data points in the [N II]![]() 6584/H

6584/H![]() vs. [O III]

vs. [O III]![]() 5007/H

5007/H![]() diagram are distributed in two groups: a sequence similar to the one in the [S II]

diagram are distributed in two groups: a sequence similar to the one in the [S II]

![]() 6717,6731/H

6717,6731/H![]() vs. [O III]

vs. [O III]![]() 5007/H

5007/H![]() diagram and a cloud of data points above that sequence with larger [N II]

diagram and a cloud of data points above that sequence with larger [N II]![]() 6584/H

6584/H![]() .

This result can be interpreted either by local variations in the

relative abundances or by changes in the ionization parameter. Here we

will explore the first option, which is the most accepted explanation

(e.g. López-Sánchez et al. 2007, and references therein) and is supported by the relatively constant ionization parameter found in specific

areas via long-slit (

.

This result can be interpreted either by local variations in the

relative abundances or by changes in the ionization parameter. Here we

will explore the first option, which is the most accepted explanation

(e.g. López-Sánchez et al. 2007, and references therein) and is supported by the relatively constant ionization parameter found in specific

areas via long-slit (![]()

![]() -3, Kobulnicky et al. 1997).

Long-slit measurements in specific areas of this field have shown out

how this galaxy present some regions with an over-abundance of

nitrogen (e.g. Walsh & Roy 1989; Kobulnicky et al. 1997). For our measured line ratios and using expression (22) in Pérez-Montero & Contini (2009), we measure a range in

-3, Kobulnicky et al. 1997).

Long-slit measurements in specific areas of this field have shown out

how this galaxy present some regions with an over-abundance of

nitrogen (e.g. Walsh & Roy 1989; Kobulnicky et al. 1997). For our measured line ratios and using expression (22) in Pérez-Montero & Contini (2009), we measure a range in

![]() of -0.70 to -1.46. Here we will assume that this over-abundance is the cause of our excess in the [N II]

of -0.70 to -1.46. Here we will assume that this over-abundance is the cause of our excess in the [N II]![]() 6584/H

6584/H![]() line

ratio and will use this excess to precisely delimit the area presenting

this over-abundance. To this aim, we placed the information of

each of the spaxels in the [S II]

line

ratio and will use this excess to precisely delimit the area presenting

this over-abundance. To this aim, we placed the information of

each of the spaxels in the [S II]

![]() 6717,6731/H

6717,6731/H![]() vs. [N II]

vs. [N II]![]() 6584/H

6584/H![]() diagram, which better separates the two different groups

described above. This is presented in Fig. 9. We have assumed that in the so-called un-polluted areas, the [N II]

diagram, which better separates the two different groups

described above. This is presented in Fig. 9. We have assumed that in the so-called un-polluted areas, the [N II]![]() 6584/H

6584/H![]() and [S II]

and [S II]

![]() 6717,6731/H

6717,6731/H![]() follow a linear relation. This is a reasonable assumption since the [N II]

follow a linear relation. This is a reasonable assumption since the [N II]![]() 6584/[S II]

6584/[S II]

![]() 6717,6731 line ratio has a low dependence with the abundance and the properties of the ionizing radiation field (Kewley & Dopita 2002). This standard relation was determined by

fitting a first-degree polynomial to the data points with [S II]

6717,6731 line ratio has a low dependence with the abundance and the properties of the ionizing radiation field (Kewley & Dopita 2002). This standard relation was determined by

fitting a first-degree polynomial to the data points with [S II]

![]() 6717,6731/H

6717,6731/H![]() > -0.8 (indicated in Fig. 9 with a red box). Those spaxels whose [N II]

> -0.8 (indicated in Fig. 9 with a red box). Those spaxels whose [N II]![]() 6584/H

6584/H![]() line ratio was in excess of more than 3-

line ratio was in excess of more than 3-![]() from the relation determined by this fit, have been identified as having an

[N II]

from the relation determined by this fit, have been identified as having an

[N II]![]() 6584/H

6584/H![]() excess, and are identified by diamonds in Fig. 9. As can be seen from this figure, there are a number of spaxels where this excess is much above the standard relation.

excess, and are identified by diamonds in Fig. 9. As can be seen from this figure, there are a number of spaxels where this excess is much above the standard relation.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{14154fg10.ps}

\vspace*{1.8mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/09/aa14154-10/Timg104.png)

|

Figure 10:

Spaxels with [N II] |

| Open with DEXTER | |

The data points thus identified with [N II]![]() 6584/H

6584/H![]() excess are shown as a map in Fig. 10 where the location and magnitude of the [N II]

excess are shown as a map in Fig. 10 where the location and magnitude of the [N II]![]() 6584/H

6584/H![]() excess is indicated by white circles, whose size is proportional to the size of the [N II]

excess is indicated by white circles, whose size is proportional to the size of the [N II]![]() 6584/H

6584/H![]() excess.

This figure can be interpreted as a snapshot in the pollution process

of the interstellar medium by the SSCs in the central area of

NGC 5253. The pollution is affecting almost the whole

giant H II region. The largest values are found at

excess.

This figure can be interpreted as a snapshot in the pollution process

of the interstellar medium by the SSCs in the central area of

NGC 5253. The pollution is affecting almost the whole

giant H II region. The largest values are found at

![]() towards the north-west of the peak at Complex #1. Then, the

quantity of extra

nitrogen decreases outwards following the two tongue-shaped extensions

towards the north-west and south-east. This is consistent with the

HST observations of Kobulnicky et al. (1997) who found nitrogen enrichment in their H II-1 and H II-2, while the N/O ratio in UV-1 (see Table 3) was typical for metal-poor galaxies.

towards the north-west of the peak at Complex #1. Then, the

quantity of extra

nitrogen decreases outwards following the two tongue-shaped extensions

towards the north-west and south-east. This is consistent with the

HST observations of Kobulnicky et al. (1997) who found nitrogen enrichment in their H II-1 and H II-2, while the N/O ratio in UV-1 (see Table 3) was typical for metal-poor galaxies.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{14154fg11a.eps}\includegraph...

...ps}\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{14154fg11h.eps}

\vspace*{3.7mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/09/aa14154-10/Timg106.png)

|

Figure 11: Spectra showing Wolf-Rayet features. The first spectrum has been extracted from a low surface brightness area in the upper right corner of the FLAMES field of view and is presented here as reference. The positions of the nebular emission lines have been indicated with blue ticks and labels, while those corresponding to Wolf-Rayet features appear in red. The position and extent of the regions are indicated in Fig. 10. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

3.5 Wolf-Rayet features

Wolf-Rayet (W-R) stars are very bright objects with strong broad

emission lines in their spectra. They are classified as WN (those with

strong lines of helium and nitrogen) and WC (those with strong

lines of helium, carbon and oxygen) and are understood as the result of

the evolution of massive O stars. As they evolve, they loose

a significant amount of their mass via stellar winds showing the

products of the CNO-burning first - identified as

WN stars - and the He-burning afterwards -

as WC stars (Conti 1976). The presence of W-R stars can be recognized via the W-R bumps around

![]() 4650 Å (i.e. the blue bump, characteristic of WN stars) and

4650 Å (i.e. the blue bump, characteristic of WN stars) and ![]() 5808 Å (i.e. the red bump, characteristic of WC stars, but not covered by the present data).

5808 Å (i.e. the red bump, characteristic of WC stars, but not covered by the present data).

Table 4: Ages of the clusters associated with the W-R regions according to different indicators.

Schaerer et al. (1997,1999) carried out a thorough search and characterization of the W-R population in NGC 5253. They detected W-R features (both WN and WC) at the peak of emission in the optical (our Complex #1) and the ultraviolet (our Complex #2). Due to the spatial coincidence of these detections and the N-enriched regions found by Walsh & Roy (1989) and Kobulnicky et al. (1997) - at least in the case of the nucleus - they suggested that these W-R stars could be the cause of this enhancement. This is supported observationally by similar findings in other W-R galaxies. For example, a recent survey using Sloan data of W-R galaxies in the low-redshift Universe has shown that galaxies belonging to this group present an elevated N/O ratio, in comparison with similar non-W-R galaxies (Brinchmann et al. 2008). Other suggested possibilities to cause the enrichment in nitrogen include planetary nebulae, O star winds, He-deficient W-R star winds, and luminous blue variables (Kobulnicky et al. 1997).

Here, we characterize the W-R population in NGC 5253 and explore the hypothesis of W-R stars as the cause of the nitrogen enhancement by using the 2D spectral information provided by the present data. In the previous section we have delimited very precisely the area that presents nitrogen enhancement. In a same manner, it is possible to look for and localize the areas that present W-R emission. Note that due to the continuous sampling of the present data this can be done in a completely unbiased way.

We visually inspected each spectrum looking for the more prominent W-R features in the blue bump (i.e. N III ![]() 4640 and He II

4640 and He II ![]() 4686). The areas where these features have been found are marked in Fig. 10 with dashed lines. The co-added and extracted spectra of each individual area appear in Fig. 11

together with a reference spectrum, free of W-R features,

made by co-adding 20 spaxels in the upper right corner of the

FLAMES field of view.

4686). The areas where these features have been found are marked in Fig. 10 with dashed lines. The co-added and extracted spectra of each individual area appear in Fig. 11

together with a reference spectrum, free of W-R features,

made by co-adding 20 spaxels in the upper right corner of the

FLAMES field of view.

We confirm the detection of W-R features associated with the

nucleus and the brightest cluster in the ultraviolet, UV-1

(our W-R 3). In the same manner, we also detect a broad

He II line associated with the north-west and south-east extensions (i.e. H II-2

and W-R 2, respectively). In addition, there are three more

areas which present W-R features, called W-R 1,

W-R 4 and W-R 5, relatively far (

![]() pc)

from the main area of activity. Interestingly, two of these

regions (W-R 4 and W-R 5) present a narrow

nebular He II on top of the broad W-R feature.

pc)

from the main area of activity. Interestingly, two of these

regions (W-R 4 and W-R 5) present a narrow

nebular He II on top of the broad W-R feature.

The short phase of W-R stars during star evolution makes their

detection a very precise method for estimating the age of a given

stellar population. According to Leitherer et al. (1999), typically an instantaneous starburst shows these features at ages of

![]() Myr for metallicites of

Z = 0.004-0.008, similar to the one in NGC 5253.

Thus, very young stellar clusters must be associated with the areas

that display these W-R features. We compared the positions of our

detections with the catalogue of clusters given by Harris et al. (2004) and compiled in Table 4.

All our regions, except W-R 5, are associated with one

(or several) young (i.e. <5 Myr) star cluster(s).

Regarding W-R 5, Harris et al. (2004) do not report any cluster associated with that area.

Myr for metallicites of

Z = 0.004-0.008, similar to the one in NGC 5253.

Thus, very young stellar clusters must be associated with the areas

that display these W-R features. We compared the positions of our

detections with the catalogue of clusters given by Harris et al. (2004) and compiled in Table 4.

All our regions, except W-R 5, are associated with one

(or several) young (i.e. <5 Myr) star cluster(s).

Regarding W-R 5, Harris et al. (2004) do not report any cluster associated with that area.

Cluster ages in Harris et al. (2004) were estimated using both broadband photometry and the H![]() equivalent width. We estimated the ages by means of two indicators:

the ratio between the number of W-R and O stars; and the H

equivalent width. We estimated the ages by means of two indicators:

the ratio between the number of W-R and O stars; and the H![]() equivalent width. The ratio between the number of W-R and O stars was estimated from F(bb)/F(H

equivalent width. The ratio between the number of W-R and O stars was estimated from F(bb)/F(H![]() ), where F(bb) and F(H

), where F(bb) and F(H![]() )

are the flux in the blue bump (measured with splot) and in H

)

are the flux in the blue bump (measured with splot) and in H![]() respectively and using the relation proposed by

Schlegel et al. (1998). Uncertainties are

large, mainly due to the difficulty to define the continuum and to

avoid the contamination of the nebular emission lines when

measuring F(bb) but indicates a range in

respectively and using the relation proposed by

Schlegel et al. (1998). Uncertainties are

large, mainly due to the difficulty to define the continuum and to

avoid the contamination of the nebular emission lines when

measuring F(bb) but indicates a range in ![]() (WR/(WR+O)) of

(WR/(WR+O)) of

![]() to -1.2 (see Table 4,

Col. 4). There is a higher proportion of W-R stars in

W-R 5, W-R 1 and W-R 4 and somewhat lower in those areas

associated with the giant H II region. The H

to -1.2 (see Table 4,

Col. 4). There is a higher proportion of W-R stars in

W-R 5, W-R 1 and W-R 4 and somewhat lower in those areas

associated with the giant H II region. The H![]() equivalent widths are extremely high, consistent again with the

expected youth of the stellar population. Predicted ages from these two

age tracers are reported in Table 4, Cols. 5 and 7. They were estimated by using STARBURST99 (Leitherer et al. 1999), assuming an instantaneous burst of Z=0.008, an upper mass limit of

equivalent widths are extremely high, consistent again with the

expected youth of the stellar population. Predicted ages from these two

age tracers are reported in Table 4, Cols. 5 and 7. They were estimated by using STARBURST99 (Leitherer et al. 1999), assuming an instantaneous burst of Z=0.008, an upper mass limit of

![]() = 100

= 100 ![]() and a Salpeter-type Initial Mass Function. The two age tracers give

consistent age predictions and in agreement with those reported in Harris et al. (2004).

and a Salpeter-type Initial Mass Function. The two age tracers give

consistent age predictions and in agreement with those reported in Harris et al. (2004).

The distribution of the W-R features, in an area of about 100 pc ![]() 100 pc, much larger than the one polluted with nitrogen, suggests that all

the detected W-R stars are not, in general, the cause of this

pollution. Since the N-enrichment appears to be associated with the

pair of

clusters in the core and, given the position of maximum, most probably

with the obscured SSC C2, the best W-R star

candidates to be the cause of this enrichment are those corresponding

to our

Nuc aperture, and perhaps also the H II-2 and W-R 2 regions.

100 pc, much larger than the one polluted with nitrogen, suggests that all

the detected W-R stars are not, in general, the cause of this

pollution. Since the N-enrichment appears to be associated with the

pair of

clusters in the core and, given the position of maximum, most probably

with the obscured SSC C2, the best W-R star

candidates to be the cause of this enrichment are those corresponding

to our

Nuc aperture, and perhaps also the H II-2 and W-R 2 regions.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{14154fg12a.eps}\hspace*{4mm}...

...ps}\hspace*{5mm}

\includegraphics[width=7.9cm,clip]{14154fg12d.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/09/aa14154-10/Timg113.png)

|

Figure 12: Spectra showing nebular He II, but no W-R features. The positions of the nebular emission lines have been indicated with blue ticks and labels, while those corresponding to Wolf-Rayet features appear in red. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

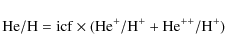

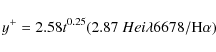

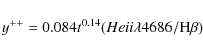

3.6 Nebular He II and helium abundance

The hypothesis that the W-R population is the cause of the nitrogen enrichment in NGC 5253 requires an enhancement of the helium abundance too (e.g. Schaerer 1996). This is nicely illustrated in Kobulnicky et al. (1997) where different linear relations between the nitrogen and helium abundances (N/H and He/H) are presented according to different scenarios of nitrogen enrichment (W-Rs, PNe, etc.). The only scenario able to explain an extra quantity of nitrogen in the ISM without any extra helium counterpart would be the one where this nitrogen is caused during the late O-star wind phase.

As in previous sections, we can measure at each spaxel the

total helium abundance and compare it with that for nitrogen. Since

lines like [O II]

![]() 3726,3728

did not fall in the covered spectral range, we did not determine the

absolute nitrogen abundance. Instead, we used the mean of the