| Issue |

A&A

Volume 517, July 2010

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A54 | |

| Number of page(s) | 23 | |

| Section | Catalogs and data | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/200913366 | |

| Published online | 04 August 2010 | |

A deep survey of the AKARI north ecliptic pole field

I. WSRT 20 cm radio survey description, observations and data reduction

G. J. White1,2 - C. Pearson2,3,1 - R. Braun4 - S. Serjeant 1 - H. Matsuhara5 - T. Takagi5 - T. Nakagawa5 - R. Shipman6 - P. Barthel7 - N. Hwang8 - H. M. Lee9 - M. G. Lee9 - M. Im9 - T. Wada5 - S. Oyabu5 - S. Pak9 - M.-Y. Chun9 - H. Hanami10 - T. Goto11,8 - S. Oliver12

1 - Department of Physics and Astronomy, The Open University, Walton

Hall, Milton Keynes, MK7 6AA, UK

2 - Space Science and Technology Department, STFC Rutherford Appleton

Laboratory, Chilton, Didcot, Oxfordshire, OX11 0QX, UK

3 - Institute for Space Imaging Science, University of Lethbridge,

Lethbridge, Alberta, T1K 3M4, Canada

4 - CSIRO Astronomy and Space Science, Australia Telescope National

Facility, CSIRO, Marsfield NSW 2122, Australia

5 - Institute of Space and Astronautical Science, JAXA, Yoshino-dai

3-1-1, Sagamihara, Kanagawa 229-8510, Japan

6 - SRON Netherlands Institute for Space Research, PO Box 800, 9700 AV

Groningen, The Netherlands

7 - Kapteyn Astronomical Institute, University of Groningen, PO Box

800, 9700 AV Groningen, The Netherlands

8 - National Astronomical Observatory of Japan, Osawa, Mitaka, Tokyo

181-8588, Japan

9 - Astronomy Program, Department of Physics and Astronomy, Seoul

National University, Seoul 151-747, Korea

10 - Physics Section, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Iwate

University, Morioka 020-8550, Japan

11 - Institute for Astronomy, University of Hawaii, 2680 Woodlawn

Drive, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA

12 - Department of Physics & Astronomy, School of Science and

Technology, University of Sussex, Falmer, Brighton BN1 9QH, UK

Received 28 September 2009 / Accepted 26 April 2010

Abstract

Aims. The Westerbork Radio Synthesis Telescope, ![]() ,

has been used to make a deep radio survey of an

,

has been used to make a deep radio survey of an ![]() 1.7 degree2

field coinciding with the AKARI north ecliptic pole deep field. The

observations, data reduction and source count analysis are presented,

along with a description of the overall scientific objectives.

1.7 degree2

field coinciding with the AKARI north ecliptic pole deep field. The

observations, data reduction and source count analysis are presented,

along with a description of the overall scientific objectives.

Methods. The survey consisted of

10 pointings, mosaiced with enough overlap to maintain a

similar sensitivity across the central region that reached as low as

21 ![]() Jy beam-1

at 1.4 GHz.

Jy beam-1

at 1.4 GHz.

Results. A catalogue containing 462 sources detected

with a resolution of 17.0

![]()

![]() 15.5

15.5

![]() is presented. The differential source counts calculated from the

is presented. The differential source counts calculated from the ![]() data

have been compared with those from the shallow

data

have been compared with those from the shallow ![]() survey

of Kollgaard et al. 1994, and show a pronounced excess for

sources fainter than

survey

of Kollgaard et al. 1994, and show a pronounced excess for

sources fainter than ![]() 1 mJy,

consistent with the presence of a population of star forming galaxies

at sub-mJy flux levels.

1 mJy,

consistent with the presence of a population of star forming galaxies

at sub-mJy flux levels.

Conclusions. The AKARI north ecliptic pole deep

field is the focus of a major observing campaign conducted across the

entire spectral region. The combination of these data sets, along with

the deep nature of the radio observations will allow unique studies of

a large range of topics including the redshift evolution of the

luminosity function of radio sources, the clustering environment of

radio galaxies, the nature of obscured radio-loud active galactic

nuclei, and the radio/far-infrared correlation for distant galaxies.

This catalogue provides the basic data set for a future series of paper

dealing with source identifications, morphologies, and the associated

properties of the identified radio sources.

Key words: galaxies: active - radio continuum: galaxies - surveys - catalogs - cosmology: observations

1 Introduction

Deep radio and far-infrared (far-IR) surveys are useful to study the

global properties of extragalactic source populations in the early

Universe; to measure the evolution of AGN's and starburst

galaxies at early epochs; and to understand the cosmic history of star

formation. Recently, the Japanese AKARI infrared satellite has

made deep surveys close to the north and the south ecliptic poles.

These regions have relatively low line of sight extinction

(to the distant Universe) and low hydrogen column densities,

which are important if objects at large distances are to be detectable

at optical and infrared wavelengths. To support the AKARI

north ecliptic pole (![]() ) survey

(Matsuhara et al. 2006;

Wada et al. 2008),

this region has been observed using the Westerbork Radio Synthesis

Telescope (

) survey

(Matsuhara et al. 2006;

Wada et al. 2008),

this region has been observed using the Westerbork Radio Synthesis

Telescope (

![]() ).

).

The observational results of the ![]() survey will be presented in three papers: a) the present paper

presents the basic radio survey, source catalogues, radio source counts

and statistics; b) a second paper will report the

results from cross-correlation between the

survey will be presented in three papers: a) the present paper

presents the basic radio survey, source catalogues, radio source counts

and statistics; b) a second paper will report the

results from cross-correlation between the ![]() radio observations and the infrared source catalogue from the AKARI NEP

survey; and c) the third paper will present optical

identifications from a cross-correlation between the

radio observations and the infrared source catalogue from the AKARI NEP

survey; and c) the third paper will present optical

identifications from a cross-correlation between the ![]() radio

survey and deep optical imaging made using the Canada France Hawaii

3.6 m (CFHT) and SUBARU 8 m telescopes, and will

address the more global objectives of the survey stated above.

radio

survey and deep optical imaging made using the Canada France Hawaii

3.6 m (CFHT) and SUBARU 8 m telescopes, and will

address the more global objectives of the survey stated above.

2 Multi-wavelength observations

The two ecliptic poles are amongst the deepest exposure regions that

have been observed by many infrared satellite missions, and provide a

wealth of data about the distant source populations, for example the

surveys of IRAS (Hacking et al. 1987; Aussel

et al. 2000),

ISO (Stickel et al. 1998;

Aussel et al. 2000),

COBE (Bennett et al. 1996),

and ROSAT (Mullis et al. 2001,

2003). Other

surveys of this region at radio wavelengths have been made with the ![]() (Kollgaard et al. 1994;

Brinkmann et al. 1999,

at 20 and 91 cm); Westerbork: Rengelink

et al. (1997);

Effelsberg 100 m telescope (Loiseau et al. 1988); and in

2.7 GHz surveys by Condon & Broderick (1985, 1986) and Loiseau

et al. (1988);

at optical/IR wavelengths (Gaidos et al. 1993; and K

(Kollgaard et al. 1994;

Brinkmann et al. 1999,

at 20 and 91 cm); Westerbork: Rengelink

et al. (1997);

Effelsberg 100 m telescope (Loiseau et al. 1988); and in

2.7 GHz surveys by Condon & Broderick (1985, 1986) and Loiseau

et al. (1988);

at optical/IR wavelengths (Gaidos et al. 1993; and K

![]() mmel et al. 2000, 2001); and at X-ray

wavelengths using ROSAT by Henry et al. (2001) and Mullis

et al. (2001).

The area around the

mmel et al. 2000, 2001); and at X-ray

wavelengths using ROSAT by Henry et al. (2001) and Mullis

et al. (2001).

The area around the ![]() has a moderate/low level of HI emission

has a moderate/low level of HI emission ![]() 4.3

4.3 ![]() 1020 cm-2 (Elvis

et al. 1994).

This corresponds to a line of sight extinction Av

1020 cm-2 (Elvis

et al. 1994).

This corresponds to a line of sight extinction Av ![]() 0.2-0.5 mag, favouring very deep optical and near-infrared

observations because of the low level of foreground extinction

(Zickgraf et al. 1997).

Optical and infrared surveys provide key information to help to

understand the source populations of the

0.2-0.5 mag, favouring very deep optical and near-infrared

observations because of the low level of foreground extinction

(Zickgraf et al. 1997).

Optical and infrared surveys provide key information to help to

understand the source populations of the ![]() region,

in particular the AKARI mission and its supporting ancillary

programmes have included two deep 2.4-24

region,

in particular the AKARI mission and its supporting ancillary

programmes have included two deep 2.4-24 ![]() m wavelength

surveys at the North Ecliptic Pole (

m wavelength

surveys at the North Ecliptic Pole (![]() ): a) covering

a 0.4 deg2 circular area

(known as

): a) covering

a 0.4 deg2 circular area

(known as ![]() -Deep -

see Matsuhara et al. 2006);

and b) a wide and shallow 2.4-24

-Deep -

see Matsuhara et al. 2006);

and b) a wide and shallow 2.4-24 ![]() m survey

covering a 5.8 deg2 circular

area surrounding the

m survey

covering a 5.8 deg2 circular

area surrounding the ![]() -Deep

field (also known as

-Deep

field (also known as ![]() -Wide -

Lee et al. 2009).

-Wide -

Lee et al. 2009).

Optical, radio, X-ray and infrared surveys provide essential

support to the interpretation of deep extragalactic radio surveys.

A shallow ![]() 20 cm survey of the

20 cm survey of the ![]() region was made by Kollgaard et al. (1994), which covered

an area of 29.3 deg2. The Kollgaard

survey reported 2435 radio sources with flux densities ranging

from 0.3-1000 mJy, observed with a 20

region was made by Kollgaard et al. (1994), which covered

an area of 29.3 deg2. The Kollgaard

survey reported 2435 radio sources with flux densities ranging

from 0.3-1000 mJy, observed with a 20

![]() beam and 1

beam and 1![]() noise

noise

![]() 60

60 ![]() Jy per beam

at the centre of the survey field. A comparison between this

radio survey and the NASA Extragalactic database, and with other

catalogues (including the ROSAT X-ray catalogue), resulted in the

identification of

Jy per beam

at the centre of the survey field. A comparison between this

radio survey and the NASA Extragalactic database, and with other

catalogues (including the ROSAT X-ray catalogue), resulted in the

identification of ![]() 20

20![]() of the sources, with

of the sources, with ![]() 6

6![]() of the sources found to be extended with diameters

of the sources found to be extended with diameters ![]() 30

30

![]() .

A 2.7 GHz survey of the region was made by Condon

& Broderick (1985,

1986).

Between 1 and 150 mJy, the slope of the log N - log S relationship

was 0.68

.

A 2.7 GHz survey of the region was made by Condon

& Broderick (1985,

1986).

Between 1 and 150 mJy, the slope of the log N - log S relationship

was 0.68 ![]() 0.03.

An even larger area of 570 degrees2

was observed at 325 MHz using the

0.03.

An even larger area of 570 degrees2

was observed at 325 MHz using the ![]() telescope by Rengelink et al. (1997) in the

telescope by Rengelink et al. (1997) in the ![]() survey (beam size 54

survey (beam size 54

![]() ), which resulted in the

detection of more than 11 000 sources. The source

populations have already in this region include galaxy clusters (Gioia

et al. 2003,

2004; Hwang

et al. 2007;

Goto et al. 2008),

radio galaxy clusters (Branchesi et al. 2006), stars

(Pretorious et al. 2007;

Micela et al. 2007;

Affer et al. 2008),

X-ray sources (Voges et al. 2001; Henry

et al. 2001,

2006) and

infrared sources (K

), which resulted in the

detection of more than 11 000 sources. The source

populations have already in this region include galaxy clusters (Gioia

et al. 2003,

2004; Hwang

et al. 2007;

Goto et al. 2008),

radio galaxy clusters (Branchesi et al. 2006), stars

(Pretorious et al. 2007;

Micela et al. 2007;

Affer et al. 2008),

X-ray sources (Voges et al. 2001; Henry

et al. 2001,

2006) and

infrared sources (K

![]() mmel et al. 2000).

mmel et al. 2000).

3 WSRT Observations

The radio observations presented in this paper were observed during

2004 with the ![]() operated at 20 cm wavelength. The array included fourteen

25 m telescopes arranged in a 2.7 km east-west

configuration, with signals processed using a digital continuum 2-bit

back end consisting of eight 20 MHz bandwidth sub-bands across

the frequency range 1301-1461 MHz. The

operated at 20 cm wavelength. The array included fourteen

25 m telescopes arranged in a 2.7 km east-west

configuration, with signals processed using a digital continuum 2-bit

back end consisting of eight 20 MHz bandwidth sub-bands across

the frequency range 1301-1461 MHz. The ![]() observations were interleaved with observations of the intensity,

polarisation and phase calibration sources 3C 147

and 3C 286, which past experience suggested should

lead to a flux density calibration accuracy of better than 5

observations were interleaved with observations of the intensity,

polarisation and phase calibration sources 3C 147

and 3C 286, which past experience suggested should

lead to a flux density calibration accuracy of better than 5![]() .

The survey mosaic was made from 10 discrete pointings that

were positioned on an hexagonal grid, with beam spacings at the 70

.

The survey mosaic was made from 10 discrete pointings that

were positioned on an hexagonal grid, with beam spacings at the 70![]() point

of the 36.2

point

of the 36.2![]() primary

beam full width half maximum (FWHM) diameter, each observed as a full

12 h track. This observing strategy was adopted to provide a

relatively uniform noise background of less than

primary

beam full width half maximum (FWHM) diameter, each observed as a full

12 h track. This observing strategy was adopted to provide a

relatively uniform noise background of less than ![]() 10

10![]() over the most sensitive part of the surveyed area (see Prandoni

et al. 2006)

for a full treatment of mosaicing strategies, who show that this

results in mosaiced noise variations of

over the most sensitive part of the surveyed area (see Prandoni

et al. 2006)

for a full treatment of mosaicing strategies, who show that this

results in mosaiced noise variations of ![]() 5

5![]() ),

where a 1

),

where a 1![]() source

detection sensitivity of point sources as low as 21

source

detection sensitivity of point sources as low as 21 ![]() Jy per beam

was achieved. The J2000 coordinate system is used throughout

this paper. Experience at the WSRT suggests that the interpolation and

coplanarity (also known as faceting) processing in the mosaicing step

should not introduce errors in excess of 0.1 arcsec for a

relatively small mosaic of this size.

Jy per beam

was achieved. The J2000 coordinate system is used throughout

this paper. Experience at the WSRT suggests that the interpolation and

coplanarity (also known as faceting) processing in the mosaicing step

should not introduce errors in excess of 0.1 arcsec for a

relatively small mosaic of this size.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=90,width=15cm,clip]{13366fg1.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/09/aa13366-09/Timg25.png)

|

Figure 1:

The central 1 square degree area of the |

| Open with DEXTER | |

The observations were reduced and calibrated using standard tasks in

the ![]() software package. The data sets were uniformly of high quality, with

only a few percent of the visibilities having to be flagged out, mostly

due to low level radio interference. Each pointing was mapped onto a

regular grid with 4

software package. The data sets were uniformly of high quality, with

only a few percent of the visibilities having to be flagged out, mostly

due to low level radio interference. Each pointing was mapped onto a

regular grid with 4

![]() pixels using a

multi-frequency synthesis approach to minimise bandwidth smearing.

Adjacent pointings were co-added to the FWHM point (Condon

et al. 1998;

Huynh et al. 2005).

After a first iteration, model components with a flux density of more

than

pixels using a

multi-frequency synthesis approach to minimise bandwidth smearing.

Adjacent pointings were co-added to the FWHM point (Condon

et al. 1998;

Huynh et al. 2005).

After a first iteration, model components with a flux density of more

than ![]() 1 mJy beam-1

were used for phase and amplitude self-calibration, to correct

for residual phase and amplitude errors. The data were then re-imaged

and cleaned with

1 mJy beam-1

were used for phase and amplitude self-calibration, to correct

for residual phase and amplitude errors. The data were then re-imaged

and cleaned with ![]() 2000 clean

components, at which point the side lobes of most of the strong sources

were found to be below the noise level. There was however a particular

problem toward the central position in the mosaic where the prominent

galactic planetary nebula, the Cat's Eye Nebula (NGC 6543)

lies close to the field centre. Since this is slightly extended at

radio wavelengths, it presented a particular challenge to the data

reduction and cleaning, and ultimately limited the rms noise

level achievable in the immediate vicinity to be several times the

thermal limit. However, the number of pixels affected was very

small (

2000 clean

components, at which point the side lobes of most of the strong sources

were found to be below the noise level. There was however a particular

problem toward the central position in the mosaic where the prominent

galactic planetary nebula, the Cat's Eye Nebula (NGC 6543)

lies close to the field centre. Since this is slightly extended at

radio wavelengths, it presented a particular challenge to the data

reduction and cleaning, and ultimately limited the rms noise

level achievable in the immediate vicinity to be several times the

thermal limit. However, the number of pixels affected was very

small (![]() 0.1

0.1![]() of the total), and a correction for this was made during the

differential source count calculation presented

in Sect. 7.

of the total), and a correction for this was made during the

differential source count calculation presented

in Sect. 7.

After reduction of the individual pointings, the maps were

individually intensity corrected using a model of the primary beam, and

then mosaiced together into a final image using the ![]() task

task ![]() ,

to make a linearly combined mosaic, correcting for the

individual primary beam patterns, and optimizing the signal to noise

ratio. The pixels at the edges of the mosaiced region have higher noise

uncertainties compared to those at the centre of the merged field

because of the primary beam profile, and the mosaicing strategy. The

mosaiced, primary beam corrected image of the high sensitivity region

of the

,

to make a linearly combined mosaic, correcting for the

individual primary beam patterns, and optimizing the signal to noise

ratio. The pixels at the edges of the mosaiced region have higher noise

uncertainties compared to those at the centre of the merged field

because of the primary beam profile, and the mosaicing strategy. The

mosaiced, primary beam corrected image of the high sensitivity region

of the ![]() image is shown in Fig. 1.

image is shown in Fig. 1.

Several automated source extraction and cataloging routines

were tested, including the ![]() task

task ![]() and the

and the ![]() tasks

tasks ![]() and

and ![]() (Sault et al. 1995),

but the latter task was eventually adopted as the extraction task of

choice for reasons that will be discussed in Sect. 4.

A quantitative comparison between

(Sault et al. 1995),

but the latter task was eventually adopted as the extraction task of

choice for reasons that will be discussed in Sect. 4.

A quantitative comparison between ![]() ,

,

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

and

,

and ![]() has already been presented by Hopkins et al. (2002) to which the

reader is referred for a rigorous treatment of noise and error

estimates relevant to this paper.

has already been presented by Hopkins et al. (2002) to which the

reader is referred for a rigorous treatment of noise and error

estimates relevant to this paper.

The final restored beam size in the mosaic after all of the

associated processing steps was 17.0

![]()

![]() 15.5

15.5

![]() at position angle 0 degrees. The most sensitive part of the

survey field had a 1

at position angle 0 degrees. The most sensitive part of the

survey field had a 1![]() rms sensitivity of 21

rms sensitivity of 21 ![]() Jy beam-1 in the

centre of the map, increasing to

Jy beam-1 in the

centre of the map, increasing to ![]() 100

100 ![]() Jy beam-1 toward

the edges of the field, because of the primary beam attenuation

correction. It was therefore not possible to use the same

detection threshold across the whole of the mosaiced region.

Furthermore, flux densities measured toward the image edges were

increasingly affected by uncertainties in the primary beam model, and

consequently the image analysis was restricted to those sources which

lie in regions where the theoretical sensitivity is below 60

Jy beam-1 toward

the edges of the field, because of the primary beam attenuation

correction. It was therefore not possible to use the same

detection threshold across the whole of the mosaiced region.

Furthermore, flux densities measured toward the image edges were

increasingly affected by uncertainties in the primary beam model, and

consequently the image analysis was restricted to those sources which

lie in regions where the theoretical sensitivity is below 60 ![]() Jy beam-1

for noise considerations, and to mitigate other biases such as

bandwidth smearing so as not to affect the source intensities by more

than a few percent. To measure the noise, estimates of the rms

errors were estimated using

Jy beam-1

for noise considerations, and to mitigate other biases such as

bandwidth smearing so as not to affect the source intensities by more

than a few percent. To measure the noise, estimates of the rms

errors were estimated using ![]() ,

and separately using the

,

and separately using the ![]() task

task ![]() .

The detection sensitivity is shown in Fig. 2, with similar

results being obtained in

.

The detection sensitivity is shown in Fig. 2, with similar

results being obtained in ![]() and in

and in ![]() .

.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{13366fg2.ps}\vspace*{3mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/09/aa13366-09/Timg33.png)

|

Figure 2:

The horizontal axis shows the typical 1 |

| Open with DEXTER | |

4 Source catalogue

The ![]() mosaic has a non-uniform and continuously varying noise level, a

complex mosaicing strategy, and locally elevated noise levels around

the few bright sources such as the Cat's Eye Nebula, and it is clear

that source detection using an uniform flux threshold over the whole

primary beam corrected image is not the optimal approach. Source

detection in this case is better determined using locally determined

noise levels - an approach that has already been used in other

studies to improve the efficacy of their source detection catalogues

(e.g. Morganti et al. 2004).

mosaic has a non-uniform and continuously varying noise level, a

complex mosaicing strategy, and locally elevated noise levels around

the few bright sources such as the Cat's Eye Nebula, and it is clear

that source detection using an uniform flux threshold over the whole

primary beam corrected image is not the optimal approach. Source

detection in this case is better determined using locally determined

noise levels - an approach that has already been used in other

studies to improve the efficacy of their source detection catalogues

(e.g. Morganti et al. 2004).

The source catalogue in this paper was built using the ![]() task

task ![]() .

This is a method for identifying source pixels, where the detected

sources are drawn from a distribution of pixels with a robustly known

chance of being falsely drawn from the background (see Hopkins

et al. 1999,

2002; and

Morganti et al. 2004)

for a complete description justifying the adoption of this technique.

.

This is a method for identifying source pixels, where the detected

sources are drawn from a distribution of pixels with a robustly known

chance of being falsely drawn from the background (see Hopkins

et al. 1999,

2002; and

Morganti et al. 2004)

for a complete description justifying the adoption of this technique. ![]() robustly characterises the fraction of expected pixels more rigorously

than from a traditional sigma-clipping criterion - which is

known to suffer limitations at lower signal-to-noise levels. Noise

estimation is implemented in the image plane by dividing the image into

small square regions within which the mean and rms noise level

are estimated by fitting a Gaussian to the pixel histogram in each

region. The image is then normalised by subtracting the mean and

dividing by the rms within each region, resulting in an image where

pixel values are specified in units of the local rms noise

level

robustly characterises the fraction of expected pixels more rigorously

than from a traditional sigma-clipping criterion - which is

known to suffer limitations at lower signal-to-noise levels. Noise

estimation is implemented in the image plane by dividing the image into

small square regions within which the mean and rms noise level

are estimated by fitting a Gaussian to the pixel histogram in each

region. The image is then normalised by subtracting the mean and

dividing by the rms within each region, resulting in an image where

pixel values are specified in units of the local rms noise

level ![]() .

.

![]() uses a

statistical technique, the false discovery rate (FDR), which assigns a

threshold based on an acceptable rate of false detections (Hopkins

et al. 2002).

We followed Hopkins et al. (2002)

by adopting an FDR value of 2

uses a

statistical technique, the false discovery rate (FDR), which assigns a

threshold based on an acceptable rate of false detections (Hopkins

et al. 2002).

We followed Hopkins et al. (2002)

by adopting an FDR value of 2![]() .

Each of the sources identified by

.

Each of the sources identified by ![]() were visually inspected to remove any obvious mis-identifications.

Comparison with independent catalogues derived using the

were visually inspected to remove any obvious mis-identifications.

Comparison with independent catalogues derived using the ![]() task

task ![]() (with a 7

(with a 7![]() clip),

and with one derived using

clip),

and with one derived using ![]() with a locally defined background rms were almost identical with the

with a locally defined background rms were almost identical with the ![]() catalogue.

catalogue.

A sample from the final source catalogue is presented in Table 1.

The positional accuracy listed in the Table 1 is relative to the self-calibrated and

bootstrapped reference frame described in Sect. 3,

after mitigating the various effects mentioned above. Several other

effects that can affect the positions include the mosaicing process

(which we have discussed in Sect. 3; the

signal-to-noise of the detected sources (presented in Table 1; and other observational effects that

bias the positions or sizes of sources, which are discussed in

Sect. 5.

We also present an estimate of source dimensions estimated by

deconvolving the measured sizes from the synthesized beam, reporting

those more than double the synthesised beam size. Although is possible

to model the source sizes in a more exact way (for example

following the approach of Oosterbaan (1978), we only use

the present source size data as a guide to whether the sources are

either extended, or likely to be multi-component sources.

A more detailed discussion of the WSRT source sizes will be

made in a future paper that combines the present data set with higher

resolution observations of the ![]() field with the GMRT Telescope (Sedgwick et al. 2009).

To test the accuracy of the radio reference frame, WSRT

sources with a peak signal to noise ratio

field with the GMRT Telescope (Sedgwick et al. 2009).

To test the accuracy of the radio reference frame, WSRT

sources with a peak signal to noise ratio ![]() 10 which could be identified with compact optical

galaxies from a deep SUBARU image (referenced from HST Guide Star

positions) were found to have positional offsets within

10 which could be identified with compact optical

galaxies from a deep SUBARU image (referenced from HST Guide Star

positions) were found to have positional offsets within ![]() 2

2

![]() of each other, randomly distributed around the nominal radio position.

Further quantitative discussion of the optical identifications, and the

radio-optical frame registration determined from a larger selection of

optically identified sources will be presented in Paper 2,

which is dedicated to the optical/infrared identifications from this

survey (White et al., in preparation).

of each other, randomly distributed around the nominal radio position.

Further quantitative discussion of the optical identifications, and the

radio-optical frame registration determined from a larger selection of

optically identified sources will be presented in Paper 2,

which is dedicated to the optical/infrared identifications from this

survey (White et al., in preparation).

5 Flux accuracy and error estimates

The observations from a radio synthesis array must be corrected for various instrumental effects: a) the primary beam response of the antenna elements; b) time-average smearing due to the finite integration time; c) chromatic aberration resulting from the finite bandwidth (Bridle & Schwab 1989; Cotton 1989); and d) incompleteness at low signal to noise levels. We briefly describe the approach we have taken, below.

5.1 Time-average smearing

The data were observed using integration times of 60 s, which

was estimated to lead to a reduction in the flux of point sources of no

more than ![]() 1

1![]() for a point source 10

for a point source 10![]() from the field centre, and it is believed that this does not play a

dominant effect in determining source sizes.

from the field centre, and it is believed that this does not play a

dominant effect in determining source sizes.

5.2 Chromatic aberration

To correct for bandwidth smearing, the radio analog of optical

chromatic aberration, we inserted 500 artificial point source

models into the uv-data with peak values from 5-50![]() using the

using the ![]() task

task ![]() .

This data were processed in a similar way to the

.

This data were processed in a similar way to the ![]() field,

and

field,

and ![]() was used to recover the source intensities and measure the noise

uncertainties. There was no evidence significant variation of the

source intensities with position in the mosaic, which is similar to the

conclusion of Prandoni et al. (2000b) for a

similar set of

was used to recover the source intensities and measure the noise

uncertainties. There was no evidence significant variation of the

source intensities with position in the mosaic, which is similar to the

conclusion of Prandoni et al. (2000b) for a

similar set of ![]() data.

data.

5.3 Clean bias

Radio surveys can be affected by a ``clean bias'' effect, where a

systematic under estimation of the peak and total source fluxes (Becker

et al. 1995;

White et al. 1997;

Condon et al. 1998)

is a consequence of redistribution of the flux from point sources to

noise peaks in the image. Prandoni et al. (2000a,b) show that

it is possible to mitigate this bias if the ![]() ing process

is stopped well before the maximum residual flux has reached the

theoretical noise level. Following Garrett et al. (2000), we set the

cleaning limit at 5 times the theoretical noise to mitigate

against this effect.

ing process

is stopped well before the maximum residual flux has reached the

theoretical noise level. Following Garrett et al. (2000), we set the

cleaning limit at 5 times the theoretical noise to mitigate

against this effect.

5.4 Resolution bias

Resolution bias is an effect in which the peak flux densities of weak

extended sources fall below the chosen detection limit, yet still have

total integrated flux densities that are above the survey limit. In

other studies, a 3![]() correction

was required for source counts below 1 mJy (Moss

et al. 2007;

Garn et al. 2008),

although no resolution correction was applied to brighter sources. This

effect reduces the number of faint sources in differential source

counts (see for example Hopkins et al. 2002), and we do not

consider that it has a significant effect on our data reduction

methodology.

correction

was required for source counts below 1 mJy (Moss

et al. 2007;

Garn et al. 2008),

although no resolution correction was applied to brighter sources. This

effect reduces the number of faint sources in differential source

counts (see for example Hopkins et al. 2002), and we do not

consider that it has a significant effect on our data reduction

methodology.

5.5 Eddington bias

Since the source counts rise strongly with decreasing flux density,

more sources will have their true fluxes ``boosted'' by the effect of

noise, than those that are ``reduced'' at higher flux densities

(see discussion in Coppin et al. 2006).

To examine the effect of this, a population of

``test'' point sources were added into a single field, uncorrected for

the primary beam response using the ![]() task ``

task ``

![]() '', and processed and

extracted in the same way as the un-mosaiced survey data, with the

difference between the detected counts, and those inputs, providing an

estimate of the net amount of up-scattering. The effect of this was

only significant in the lowest flux bin, and led to an overestimate of

the source count by 16

'', and processed and

extracted in the same way as the un-mosaiced survey data, with the

difference between the detected counts, and those inputs, providing an

estimate of the net amount of up-scattering. The effect of this was

only significant in the lowest flux bin, and led to an overestimate of

the source count by 16![]() (the boundaries of the lowest flux bin were

(the boundaries of the lowest flux bin were ![]() 5

5![]() above the formal survey limit. This value should be compared with the

value estimated by Moss et al. (2007) of 21

above the formal survey limit. This value should be compared with the

value estimated by Moss et al. (2007) of 21![]() ,

which goes slightly closer to their formal survey limit. Consequently

in later analysis the counts in the lowest flux bin (110-125

,

which goes slightly closer to their formal survey limit. Consequently

in later analysis the counts in the lowest flux bin (110-125 ![]() Jy were

``de-boosted'' by 16

Jy were

``de-boosted'' by 16![]() .

This correction has a negligible effect for fluxes above this limit,

and it is safe to ignore it.

.

This correction has a negligible effect for fluxes above this limit,

and it is safe to ignore it.

5.6 Component extraction

In the terminology of this paper a radio component is described as a region of radio emission represented by a Gaussian shaped object in the map. Close radio doubles are represented by two Gaussians and are deemed to consist of two components, which make up a single source. A clear case of a very extended radio source is shown in Fig. 3, and a selection of other sources with multiple components is shown in Fig. 4.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{13366fg3.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/09/aa13366-09/Timg38.png)

|

Figure 3:

The extended radio source centred on the |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=90,width=15.7cm,clip]{13366fg4.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/09/aa13366-09/Timg39.png)

|

Figure 4: Regions showing complex or extended structure. The vertical scale is Declination. The contours are at 0.0001, 0.0003, 0.0005, 0.001, 0.003, 0.006, 0.012, 0.024, 0.048 and 0.096 Jy beam-1 respectively. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

5.7 Resolved sources

Although it may seem relatively straightforward to calculate the

density of sources as a function of the flux density, the distribution

of angular sizes as a function of the flux density may also bias the

results. It was assumed that the median sizes below 1 mJy

remain approximately constant as a function of the flux density with

those at higher flux levels. Fomalont et al. (2006) find that

8 ![]() 4

4![]() of the

of the ![]() Jy sources

have sizes greater than 4

Jy sources

have sizes greater than 4

![]() .

For low signal-to-noise ratio detections, Gaussian fitting routines may

be significantly affected by noise spikes, leading to errors in the

estimated widths and flux densities of the sources (Moss

et al. 2007).

This is one of the reasons for adopting the

.

For low signal-to-noise ratio detections, Gaussian fitting routines may

be significantly affected by noise spikes, leading to errors in the

estimated widths and flux densities of the sources (Moss

et al. 2007).

This is one of the reasons for adopting the ![]() source extraction methodology in this paper. The ratio

source extraction methodology in this paper. The ratio ![]() /

/

![]() = (

= (![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() )/(

)/(

![]()

![]() )

where

)

where ![]() and

and ![]() are the major and minor axes of the detected source and

are the major and minor axes of the detected source and ![]() and

and ![]() are the major and minor axes of the restoring beam. The flux density

ratio may be used to discriminate between unresolved sources and those

which are much larger than the beam (see Prandoni et al. 2006).

In Fig. 5,

the ratio of the flux densities to the signal-to-noise ratio (

are the major and minor axes of the restoring beam. The flux density

ratio may be used to discriminate between unresolved sources and those

which are much larger than the beam (see Prandoni et al. 2006).

In Fig. 5,

the ratio of the flux densities to the signal-to-noise ratio (

![]() /

/![]()

![]() )

is plotted for all sources above a 6

)

is plotted for all sources above a 6![]() local threshold. The biases introduced by using different thresholds

have been modelled by Prandoni et al. (2000a,b), Owen

et al. (2008) and Fomalont et al. (2006), which suggest

that the biases are most prevalent below an

local threshold. The biases introduced by using different thresholds

have been modelled by Prandoni et al. (2000a,b), Owen

et al. (2008) and Fomalont et al. (2006), which suggest

that the biases are most prevalent below an ![]() 5-6

5-6![]() (sigma-clip) threshold. To identify sources for which

(sigma-clip) threshold. To identify sources for which ![]()

![]() /

/![]()

![]() < 1,

a functional form of the curve f(x) =

1.0

< 1,

a functional form of the curve f(x) =

1.0 ![]() 3.22/x was plotted in Fig. 5 to define the

point where 90

3.22/x was plotted in Fig. 5 to define the

point where 90![]() of the

of the ![]() 6

6![]() detections with

detections with ![]() /

/

![]() < 1

lie above the curve (this is similar to the ratio adopted by

Prandoni et al. 2000a,b).

Reflecting this curve about

< 1

lie above the curve (this is similar to the ratio adopted by

Prandoni et al. 2000a,b).

Reflecting this curve about ![]() /

/

![]() = 1 shows

those sources which lie between the two curves, and which are

considered to be unresolved.

= 1 shows

those sources which lie between the two curves, and which are

considered to be unresolved.

In Fig. 5

the flux ratio is shown as a function of the signal-to-noise for all

the sources (or source components) in the ![]() catalogue.

catalogue.

The flux density ratio shows a skewed distribution, where the

tail toward high flux ratios is due to the presence of extended

sources. Values for ![]() result from the effect of noise in affecting the source sizes

(see Sect. 4). To establish a criterion for

extension, such noise errors have to be taken into account. The lower

envelope of the flux ratio distribution (the curve containing

90

result from the effect of noise in affecting the source sizes

(see Sect. 4). To establish a criterion for

extension, such noise errors have to be taken into account. The lower

envelope of the flux ratio distribution (the curve containing

90![]() of the sources) was determined, and mirrored it on its side (upper

envelope in Fig. 5),

so that unresolved sources should lie below the upper envelope. The

upper envelope can be characterised by the equation from Huynh

et al. (2005)

that was found to characterise the 90

of the sources) was determined, and mirrored it on its side (upper

envelope in Fig. 5),

so that unresolved sources should lie below the upper envelope. The

upper envelope can be characterised by the equation from Huynh

et al. (2005)

that was found to characterise the 90![]() envelope of sources where

envelope of sources where ![]()

![]()

![]() ,

and a 5

,

and a 5![]() cut off to the peak fluxes was adopted:

cut off to the peak fluxes was adopted:

![\begin{displaymath}%

\frac{{S_{\rm total} }}{{S_{\rm peak} }} = 1 + \left[ {\fra...

...S_{\rm peak} /\sigma _{\rm fit} } \right)^{3} }}} \right]\cdot

\end{displaymath}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/09/aa13366-09/img53.png)

|

(1) |

It is worth noting that the envelope does not converge to unity at large signal-to-noise values. This is due to the radial smearing effect which systematically reduces the ``peak'' fluxes, leading to larger

Radio sources are often made up of multiple components, as

seen earlier in Fig. 4. The

source counts need to be corrected for this, so that the fluxes of

physically related components are summed together, rather than being

treated as separate sources. Magliocchetti et al. (1998) have proposed

criteria to identify the double and compact source populations,

by plotting the separation of the nearest neighbour of a

source against the summed flux of the two sources, and selecting for

objects where the ratio of their fluxes, f1

and f2 is in the

range 0.25 ![]() f1 / f2

f1 / f2 ![]() 4.

In Fig. 6

the sum of the fluxes of nearest neighbours are plotted against their

separation.

4.

In Fig. 6

the sum of the fluxes of nearest neighbours are plotted against their

separation.

The dashed line marks the boundary satisfying the separation

criterion defined by Huynh et al. (2005):

![\begin{displaymath}%

\theta = 100\left[ {\frac{{S_{\rm total} ({\rm mJy}) }}{{10}}} \right]^{0.5}

\end{displaymath}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/09/aa13366-09/img55.png)

|

(2) |

where

5.8 Positional accuracy

Noise fluctuations limit the rms positional uncertainty in each of the

fitted sky coordinates (![]() RA or

RA or ![]() Dec) of a

faint point source with an rms brightness fluctuation

Dec) of a

faint point source with an rms brightness fluctuation

![]() and FWHM resolution

and FWHM resolution

![]() to (following Rengelink et al. 1997):

to (following Rengelink et al. 1997):

The positions listed in the Table 1 are those estimated from the external calibration sources and are internally consistent within Table 1. Further discussion of the positional alignment to the optical and infrared reference planes will be given in the second paper of this series.

5.9 Noise flux accuracy

The accuracy of flux estimates in radio interferometer data has been

discussed by a number of authors, for example Rengelink

et al. (1997).

The accuracy of flux recovery with specific reference to the ![]() technique adopted for this paper has been presented in Hopkins

et al. (2003),

and will not be repeated in detail here. However, for completeness, we

will repeat the Hopkins et al. (2003) equations

using the terminology in the present paper, which reduce to those

presented by Rengelink et al. (1997).

For point sources, Hopkins et al. (2003) show that the

total relative uncertainty in the integrated flux density is

given by:

technique adopted for this paper has been presented in Hopkins

et al. (2003),

and will not be repeated in detail here. However, for completeness, we

will repeat the Hopkins et al. (2003) equations

using the terminology in the present paper, which reduce to those

presented by Rengelink et al. (1997).

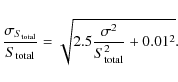

For point sources, Hopkins et al. (2003) show that the

total relative uncertainty in the integrated flux density is

given by:

|

(4) |

The reader is referred to the papers listed above for more detailed analysis of this, where the treatments of both papers reduce to similar relationships for both extended and for point sources.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=7.5cm,clip]{13366fg5.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/09/aa13366-09/Timg61.png)

|

Figure 5:

Ratio of the integrated flux |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{13366fg6.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/09/aa13366-09/Timg62.png)

|

Figure 6:

This figure shows the sum of the flux densities of the nearest

neighbours between sources from the detection catalogue. Following

Magliocchetti et al. (1998)

near neighbour pairs to the left of the line are considered as possible

double sources. The double sources can be further constrained by adding

the second constraint that the fluxes of the two components f1

and f2 should be in

the range 0.25 |

| Open with DEXTER | |

5.10 Comparison with the VLA flux density scaling

We initially compared the WSRT radio fluxes with those reported in the

Kollgaard et al. (1994)

paper. This showed that the ![]() fluxes below

fluxes below ![]() 10 mJy

appear to be too bright, initially giving some concern about the

calibration efficacy of the

10 mJy

appear to be too bright, initially giving some concern about the

calibration efficacy of the ![]() data compared to Kollgaard's survey. However, from comparison between

the integrated fluxes of the Kollgaard et al. (1994) survey and the

NVSS catalogue, it appears that the former study may

systematically overestimate the radio fluxes below about

10 mJy, as shown in Fig. 7.

data compared to Kollgaard's survey. However, from comparison between

the integrated fluxes of the Kollgaard et al. (1994) survey and the

NVSS catalogue, it appears that the former study may

systematically overestimate the radio fluxes below about

10 mJy, as shown in Fig. 7.

It therefore appears that the Kollgaard et al. (1994) fluxes may be

unreliable in the flux range appropriate to the ![]() survey, and that we should instead rely on NVSS fluxes to assess the

efficacy of the present data.

survey, and that we should instead rely on NVSS fluxes to assess the

efficacy of the present data.

To consider whether the differential source plots are affected

by an incorrectly applied completeness correction, or are truly

representative of astrophysical the source populations, such as an

under-density of sources, or showing evidence for cosmic

variance or clustering, we carried out a further series of tests.

Firstly, a comparison was made between the fluxes of sources

in common between the ![]() and

and ![]() observations is shown in Fig. 8.

observations is shown in Fig. 8.

To check the efficacy of the ![]()

![]() data, the

flux densities of components measured in the

data, the

flux densities of components measured in the ![]() survey were compared with those reported by Kollgaard et al. (1994),

as shown in Fig. 8.

survey were compared with those reported by Kollgaard et al. (1994),

as shown in Fig. 8.

The two plots show reasonably good agreement between the two

independent data sets, with the ![]() peak fluxes of Kollgaard et al. (1994) systematically

lying a little above the

peak fluxes of Kollgaard et al. (1994) systematically

lying a little above the ![]() peak fluxes above

peak fluxes above ![]() 50 mJy,

but being consistent with the

50 mJy,

but being consistent with the ![]() fluxes below that. For the integrated fluxes, there is some evidence

that the

fluxes below that. For the integrated fluxes, there is some evidence

that the ![]() fluxes are systematically higher than the

fluxes are systematically higher than the ![]() fluxes by

fluxes by ![]() 2-30

2-30![]() at fluxes below 20 mJy, although consistent at higher flux

densities. It is difficult to directly compare these, because

of the different observational characteristics, and data reduction

steps, and there is no a priori reason to favour one

calibration over another. However, this test does show that at least at

the level of a few tens of percent, and down to

at fluxes below 20 mJy, although consistent at higher flux

densities. It is difficult to directly compare these, because

of the different observational characteristics, and data reduction

steps, and there is no a priori reason to favour one

calibration over another. However, this test does show that at least at

the level of a few tens of percent, and down to ![]() 1 mJy,

the two data sets are broadly consistent with each other.

It is however difficult to know whether or not this holds at

lower flux densities, because of the lack of the lower sensitivity of

the

1 mJy,

the two data sets are broadly consistent with each other.

It is however difficult to know whether or not this holds at

lower flux densities, because of the lack of the lower sensitivity of

the ![]() survey, or due to the slightly elliptical beams noted for some

parts of the

survey, or due to the slightly elliptical beams noted for some

parts of the ![]() field by Kollgaard et al. (1994),

which makes direct comparison difficult, differing

field by Kollgaard et al. (1994),

which makes direct comparison difficult, differing ![]() coverage,

or due to intrinsic radio source variability. It is also

notable that Becker et al. (1995)

report that one effect of

coverage,

or due to intrinsic radio source variability. It is also

notable that Becker et al. (1995)

report that one effect of ![]() bias on

bias on ![]() observations is to reduce the flux. On the basis of this,

there appears to be no reason to suspect that the measured

observations is to reduce the flux. On the basis of this,

there appears to be no reason to suspect that the measured ![]() integrated fluxes lead to the apparent deficit of sub-mJy sources

suggested in Fig. 11.

integrated fluxes lead to the apparent deficit of sub-mJy sources

suggested in Fig. 11.

A search was then made to count how many sources were detected

by the Kollgaard et al. (1994)

![]() survey to a

given flux level in comparison to those detected in the

survey to a

given flux level in comparison to those detected in the ![]() survey. Restricting this analysis to the central 0.5 degree

diameter area of the

survey. Restricting this analysis to the central 0.5 degree

diameter area of the ![]() mosaic (where the rms peak flux is below

mosaic (where the rms peak flux is below ![]() 30

30 ![]() Jy per beam,

the

Jy per beam,

the ![]() observations recover 307 sources with fluxes above

2 mJy, whereas the

observations recover 307 sources with fluxes above

2 mJy, whereas the ![]() catalogue contains 53 sources, and an unpublished

610 MHz GMRT image (Sirothia et al.,

in prep.) recovers about 312 sources (after making

approximate flux scaling corrections assuming that the flux to first

order follows a

catalogue contains 53 sources, and an unpublished

610 MHz GMRT image (Sirothia et al.,

in prep.) recovers about 312 sources (after making

approximate flux scaling corrections assuming that the flux to first

order follows a

![]() relationship).

It therefore appears that there are some unexplained

discrepancies between the

relationship).

It therefore appears that there are some unexplained

discrepancies between the ![]() survey of Kollgaard and the

survey of Kollgaard and the ![]() results, although in term of raw source numbers, the

results, although in term of raw source numbers, the ![]() and GMRT data appear to be more consistent, particularly bearing in

mind the approximations assumed about spectral indices. Despite these

apparent differences, the check carried out and presented here

provide no evidence to support the presence of a systematic bias to the

and GMRT data appear to be more consistent, particularly bearing in

mind the approximations assumed about spectral indices. Despite these

apparent differences, the check carried out and presented here

provide no evidence to support the presence of a systematic bias to the

![]() differential

number counts presented in Figs. 10

and 11,

and in the absence of further reasons to be concerned about the

differential

number counts presented in Figs. 10

and 11,

and in the absence of further reasons to be concerned about the ![]() counts, it will be assumed that the differences shown in

Fig. 11

are most likely due to cosmic variance.

counts, it will be assumed that the differences shown in

Fig. 11

are most likely due to cosmic variance.

Assuming that faint radio sources have the same correlation

length as mJy sources from the ![]() and

and ![]() surveys (r

surveys (r ![]() 5 Mpc;

Overzier et al. 2003),

and that they sample the redshift interval

5 Mpc;

Overzier et al. 2003),

and that they sample the redshift interval ![]() = 1

= 1 ![]() 0.5,

the rms uncertainty to the differential source counts in a

given flux bin from cosmic variance is estimated to be

0.5,

the rms uncertainty to the differential source counts in a

given flux bin from cosmic variance is estimated to be ![]() 9 per cent

(Peacock & Dodds 1994;

Eq. (3) of Somerville et al. 2004; Simpson

et al. 2006),

which is comparable with the error spread seen at the lower flux

levels.

9 per cent

(Peacock & Dodds 1994;

Eq. (3) of Somerville et al. 2004; Simpson

et al. 2006),

which is comparable with the error spread seen at the lower flux

levels.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{13366fg7.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/09/aa13366-09/Timg66.png)

|

Figure 7:

Cross correlation of the integrated fluxes from the Kollgaard

et al. (1994)

and the NVSS surveys, with 2 |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{13366fg8.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/09/aa13366-09/Timg68.png)

|

Figure 8:

Comparison of the integrated fluxes of isolated radio sources in common

between the |

| Open with DEXTER | |

5.11 Summary of flux density corrections for systematic effects

As discussed in the previous subsections, various systematic effects

have been taken into account to estimate the ![]() flux densities, including the clean bias and the bandwidth smearing

effects. The corrected flux densities reported in Table

flux densities, including the clean bias and the bandwidth smearing

effects. The corrected flux densities reported in Table ![]() , (

, (

![]() )

have been corrected for the various effects described as follows

(following Prandoni et al. 2000b):

)

have been corrected for the various effects described as follows

(following Prandoni et al. 2000b):

where

The clean bias correction is taken into account by the term in

the square brackets. As discussed by Prandoni et al. (2000b) the

importance of the clean bias effect varies across mosaiced images

depending on the average number of clean components. For the present

data the average number of clean components was 2121, and on

the basis of the simulations reported in Sect. 5.3 we

adopt (a,b) =

(0.07, 0.82). Applying Eq. (5) correctly

leads to a good correlation between the ![]() and

and ![]() fluxes shown in Fig. 8

(where the

fluxes shown in Fig. 8

(where the ![]() fluxes were corrected using these parameters).

fluxes were corrected using these parameters).

6 Comparison with other observations

Cross identification with optical data obtained from deep

3.6 m ![]() MEGACAM imaging and IR images from the AKARI survey will be included in

the next of this series of papers on the NEP Deep Field.

An indicative overlay between the radio and

MEGACAM imaging and IR images from the AKARI survey will be included in

the next of this series of papers on the NEP Deep Field.

An indicative overlay between the radio and ![]() -band images

for the spiral galaxy CGCG 322-021 is shown in Fig. 9. Under seeing

conditions of 0.87

-band images

for the spiral galaxy CGCG 322-021 is shown in Fig. 9. Under seeing

conditions of 0.87

![]() the limiting magnitude in this filter was

the limiting magnitude in this filter was ![]() 23.5.

Further details of the data collection and reduction has been given by

Hwang et al. (2007).

23.5.

Further details of the data collection and reduction has been given by

Hwang et al. (2007).

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{13366fg9.eps}\vspace*{3mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/09/aa13366-09/Timg76.png)

|

Figure 9:

Overlay between the |

| Open with DEXTER | |

7 Differential counts

In Fig. 10

the differential radio source counts are shown from the ![]() field, normalised to a static Euclidean Universe (dN/dS S2.5 (sr-1 mJy1.5)).

These source counts are broadly consistent with previous results at

1.4 GHz (e.g. the compilation of Windhorst

et al. 1993;

the PHOENIX Deep Survey, Hopkins et al. 2003; and the

shallow

field, normalised to a static Euclidean Universe (dN/dS S2.5 (sr-1 mJy1.5)).

These source counts are broadly consistent with previous results at

1.4 GHz (e.g. the compilation of Windhorst

et al. 1993;

the PHOENIX Deep Survey, Hopkins et al. 2003; and the

shallow ![]() survey of Kollgaard et al. 1994).

survey of Kollgaard et al. 1994).

The data from Fig. 10 are

given in Table 1,

where the flux bins and mean flux for each of the bin centres are

listed in Cols. (1 and 2),

the number of sources corrected for clean and resolution bias

a discussed in Appendix A are shown in Col. (3), and

the number of sources corrected for the area coverage and double

sources in Col. 4 (note that because of these correction

factors, ![]() may be less than N0),

and in Col. (5) we show the differential source counts and the

error. The relationship for calculating the numbers in Col. 5

is the same as that presented by Kollgaard et al. (1994).

may be less than N0),

and in Col. (5) we show the differential source counts and the

error. The relationship for calculating the numbers in Col. 5

is the same as that presented by Kollgaard et al. (1994).

To model the observed source counts a two component model was

used that was made of a classical bright radio loud population and a

fainter star-forming population. It is well established that

classical bright radio galaxies require strong evolution in order to

fit the observed source counts at radio wavelengths (Longair 1966; Rowan-Robinson

1970). The

source counts above 10 mJy are dominated by giant radio

galaxies and QSOs (powered by accretion onto black holes, commonly

joined together in the literature under the generic term AGN). Radio

loud sources dominate the source counts down to levels of ![]() 1 mJy,

however, at the sub-mJy level the normalised source counts

flatten as a new population of faint radio sources emerge (Windhorst

et al. 1985).

The dominance of starburst galaxies in the sub-mJy population is

already well established (Gruppioni et al. 2008), where the

number of blue galaxies with star-forming spectral signatures is seen

to increase strongly. Rowan-Robinson et al. (1993), Hopkins

et al. (1998),

and others have concluded that the source counts at these faintest

levels require two populations, AGNs and starburst galaxies. This

latter population can best be modelled as a dusty star-forming

population, under the assumption that they are the higher redshift

analogues of the IRAS star-forming population (Rowan-Robinson

et al. 1993;

Pearson & Rowan-Robinson 1996).

In this scenario, the radio emission originates from the

non-thermal synchrotron emission from relativistic electrons

accelerated by supernovae remnants in the host galaxies.

1 mJy,

however, at the sub-mJy level the normalised source counts

flatten as a new population of faint radio sources emerge (Windhorst

et al. 1985).

The dominance of starburst galaxies in the sub-mJy population is

already well established (Gruppioni et al. 2008), where the

number of blue galaxies with star-forming spectral signatures is seen

to increase strongly. Rowan-Robinson et al. (1993), Hopkins

et al. (1998),

and others have concluded that the source counts at these faintest

levels require two populations, AGNs and starburst galaxies. This

latter population can best be modelled as a dusty star-forming

population, under the assumption that they are the higher redshift

analogues of the IRAS star-forming population (Rowan-Robinson

et al. 1993;

Pearson & Rowan-Robinson 1996).

In this scenario, the radio emission originates from the

non-thermal synchrotron emission from relativistic electrons

accelerated by supernovae remnants in the host galaxies.

To represent the radio loud population the luminosity function

of Dunlop & Peacock (1990)

was used to model the local space density with an assumption that the

population evolves in luminosity with increasing redshift. The assumed

luminosity evolution then follows a power law with redshift

of

(1+z)3.1,

broadly consistent with both optically and X-ray selected quasars

(Boyle et al. 1987).

The spectrum of the radio loud quasar population was modelled from

Elvis et al. (1994),

assuming a steep radio spectrum source of (

![]() ,

,

![]() ).

).

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{13366fg10.ps}

\vspace*{3mm}\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/09/aa13366-09/Timg80.png)

|

Figure 10:

Differential counts determined from the AKARI |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Table 1: 20 cm differential source counts for the WSRT-AKARI-NEP survey.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{13366fg11.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/09/aa13366-09/Timg82.png)

|

Figure 11: A compilation of the differential source counts of a number of deep 20 cm radio surveys taken from: SWIRE Owen & Morrison (2008); COSMOS Bondi et al. (2008); SSA13 Fomalont et al. (2006); SXDF Simpson et al. (2006); HDF-N, LOCKMAN and ELAIS N2 Biggs & Ivison (2006), HDF-S Huynh et al. (2005). The solid curve is the best fit to the present data taken as described in Fig. 10. There are however differences in the instrumental and systematic corrections that have been made for the different survey results shown here (see detailed discussion by Prandoni et al. 2000b), that make quantitative comparison at the faintest flux levels somewhat uncertain. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

To model the faint sub-mJy population the IRAS

60 ![]() m

luminosity function of Saunders et al. (2000) was used as a

starting point, with the parameters for the star-forming population,

segregated by warmer 100

m

luminosity function of Saunders et al. (2000) was used as a

starting point, with the parameters for the star-forming population,

segregated by warmer 100 ![]() m/60

m/60 ![]() m IRAS colour, given in

Pearson (2005,

in prep). To convert the infrared luminosity function to radio

wavelengths, the well known correlation between the

60

m IRAS colour, given in

Pearson (2005,

in prep). To convert the infrared luminosity function to radio

wavelengths, the well known correlation between the

60 ![]() m

far-IR and radio flux emission of

m

far-IR and radio flux emission of ![]() (Helou et al. 1985;

Yun et al. 2001;

Appleton et al. 2004;

White et al. 2009) was assumed. To model the

star-forming population the spectral template of the archetypical

starburst galaxy of M 82 from the models of Efstathiou

et al. (2000)

was adopted. The radio and far-infrared fluxes are correlated due to

the presence of hot OB stars in giant molecular clouds that

heat the surrounding dust producing the infrared emission. These stars

subsequently end their lives as supernovae with the radio emission

powered by the synchrotron emission from their remnants. The radio

spectrum is characterised by a power law of (

(Helou et al. 1985;

Yun et al. 2001;

Appleton et al. 2004;

White et al. 2009) was assumed. To model the

star-forming population the spectral template of the archetypical

starburst galaxy of M 82 from the models of Efstathiou

et al. (2000)

was adopted. The radio and far-infrared fluxes are correlated due to

the presence of hot OB stars in giant molecular clouds that

heat the surrounding dust producing the infrared emission. These stars

subsequently end their lives as supernovae with the radio emission

powered by the synchrotron emission from their remnants. The radio

spectrum is characterised by a power law of (

![]() ,

,

![]() ).

).

It was assumed that the star-forming population evolves in

luminosity as a power law ![]() .

This infrared representation of the star-forming population was

preferred over using the radio luminosity function directly, since it

creates a phenomenological link between the radio emission and the

infrared which is responsible for the bulk of the emission in the

star-forming population. Note that Huynh et al. (2005) used the radio

luminosity function of Condon et al. (2002) and derived a

best fitting evolution parameterisation

.

This infrared representation of the star-forming population was

preferred over using the radio luminosity function directly, since it

creates a phenomenological link between the radio emission and the

infrared which is responsible for the bulk of the emission in the

star-forming population. Note that Huynh et al. (2005) used the radio

luminosity function of Condon et al. (2002) and derived a

best fitting evolution parameterisation ![]() ,

slightly lower than the work presented here although the values are

broadly consistent and differences can be due to the assumed SED and

luminosity function. Hopkins (2004)

and Hopkins et al. (1998)

used radio and infrared luminosity functions respectively obtaining

evolution in the sub-mJy population

,

slightly lower than the work presented here although the values are

broadly consistent and differences can be due to the assumed SED and

luminosity function. Hopkins (2004)

and Hopkins et al. (1998)

used radio and infrared luminosity functions respectively obtaining

evolution in the sub-mJy population ![]() and

and ![]() .

It does however appear that the counts measured in this study

lie at the lower end of the emerging picture on excess sub-mJy radio

counts, as shown in Fig. 11.

.

It does however appear that the counts measured in this study

lie at the lower end of the emerging picture on excess sub-mJy radio

counts, as shown in Fig. 11.

8 Conclusions

A deep radio survey has been made of an ![]() 1.7 square degree

area around the North Ecliptic Pole field using the

1.7 square degree

area around the North Ecliptic Pole field using the ![]() at 20 cm wavelength. The maximum sensitivity of the survey was

21

at 20 cm wavelength. The maximum sensitivity of the survey was

21 ![]() Jy

beam-1, with a synthesised beam of 17.0

Jy

beam-1, with a synthesised beam of 17.0 ![]() 15.5

15.5

![]() .

The analysis methodology was carefully chosen to mitigate the various

effects that can affect the efficacy of radio synthesis array

observations, resulting in a final catalogue of 462 radio

emitting sources, with the faintest integrated fluxes at about the

100

.

The analysis methodology was carefully chosen to mitigate the various

effects that can affect the efficacy of radio synthesis array

observations, resulting in a final catalogue of 462 radio

emitting sources, with the faintest integrated fluxes at about the

100 ![]() Jy

level. The differential source counts calculated from the

Jy

level. The differential source counts calculated from the ![]() data show a pronounced excess for sources fainter than

data show a pronounced excess for sources fainter than ![]() 1 mJy,

consistent with a population of faint star forming galaxies. Comparison

between the Kollgaard et al. (1994) survey and the

NVSS catalogue shows a systematic difference in this flux range,

suggesting that one or the other may suffer from a slight

mis-calibration. The present

1 mJy,

consistent with a population of faint star forming galaxies. Comparison

between the Kollgaard et al. (1994) survey and the

NVSS catalogue shows a systematic difference in this flux range,

suggesting that one or the other may suffer from a slight

mis-calibration. The present ![]() catalogue of radio sources will form the basis for two further papers

reporting cross correlation against extant AKARI and deep optical

imaging. A further paper reporting the radio spectral indices

of the sources utilising

catalogue of radio sources will form the basis for two further papers

reporting cross correlation against extant AKARI and deep optical

imaging. A further paper reporting the radio spectral indices

of the sources utilising ![]() data will be reported elsewhere.

data will be reported elsewhere.

This work is based on observations with AKARI, aproject with the participation of ESA. We thank Andrew Hopkins for helping us to understand the operation of

, Niruj Mohan for discussions on source detection algorithms, and Sandeep Sirothia for discussions about the GMRT 610 MHz NEP survey. We also express our thanks to The Netherlands Institute for Radio Astronomy,

, for the substantial allocation of observing time; the staff of the Westerbork Observatory for technical support; and the UK Science and Technology Facilities Council,

and its forerunner,

, for manpower and travel support. The UK-Japan AKARI Consortium has also received funding awards from the Sasakawa Foundation, The British Council, and the DAIWA Foundation, which facilitated travel and exchange activities, and for which we are very grateful. T.G. acknowledges financial support from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) through JSPS Research Fellowships for Young Scientists. M.I. was supported by the Korea Science and Engineering Foundation (KOSEF) grant No. 2009-0063616, funded by the Korea government (MEST). HML was supported by National Research Foundation through grant No. 2006-341-C00018.

References

- Affer, L., Micela, G., & Morel, T. 2008, A&A, 483, 801

- Appleton, P. N., Fadda, D. T., Marleau, F. R., et al. 2004, ApJS, 154, 147

- Aussel, H., Coia, D., Mazzei, P., et al. 2000, A&AS, 141, 257

- Becker, R. H., White, R. L., & Helfand, D. J. 1995, ApJ, 450, 559

- Bennett, C. L., Banday, A. J., Gorski, K. M., et al. 1996, ApJ, 464, 1

- Biggs, A. D., & Ivison, R. J. 2006, MNRAS, 371, 963

- Bondi, M., Ciliegi, P., Zamorani, G., et al. 2003, A&AS, 403, 857

- Bondi, M., Ciliegi, P., Schinnerer, E., et al. 2008, ApJ, 681, 1129

- Boyle, B. J., Fong, R., Shanks, T., et al. 1987, MNRAS, 227, 717

- Branchesi, M., Gioia, I. M., Fanti, C., et al. 2006, A&A, 446, 97

- Bridle, A. H., & Schwab, F. R. 1989, in Synthesis Imaging in Radio Astronomy, ed. R. A. Perley, F. R Schwab, & A. H. Bridle, ASP Conf. Ser., 6, 247