| Issue |

A&A

Volume 514, May 2010

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A95 | |

| Number of page(s) | 8 | |

| Section | Extragalactic astronomy | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/200913738 | |

| Published online | 27 May 2010 | |

Dynamical constant mass-to-light ratio models of NGC 5128

S. Samurovic

Astronomical Observatory, Volgina 7, 11160 Belgrade, Serbia

Received 25 November 2009 / Accepted 12 February 2010

Abstract

Context. The existence and amount of dark matter in

early-type galaxies remains a hotly debated topic. We study dynamical

models of NGC 5128, which do not include dark matter, to test the

predictions of different constant mass-to-light models.

Aims. We use the measurements of the radial velocities of the

planetary nebulae in NGC 5128 to test the predictions of Newtonian

constant mass-to-light ratio models and we also extend our study to

different MOND models.

Methods. The planetary nebulae of NGC 5128 were used as a

tracer of the galaxy's gravitational potential. The Jeans equation was

calculated for both the Newtonian mass-follows-light and the MOND

approaches. Spherical symmetry is assumed and the calculations are

performed for both isotropic and anisotropic cases.

Results. We solved the Jeans equation in spherical approximation

and found that the isotropic Newtonian mass-follows-light models

without dark matter may provide successful fits out to

![]() ;

to obtain a good fit in the outermost region (

;

to obtain a good fit in the outermost region (

![]() )

one needs either dark matter or tangential anisotropies. Concerning

MOND models we found that no isotropic MOND model without dark matter

can provide a successful fit interior to

)

one needs either dark matter or tangential anisotropies. Concerning

MOND models we found that no isotropic MOND model without dark matter

can provide a successful fit interior to

![]() ;

for the anisotropic MOND models interior to

;

for the anisotropic MOND models interior to ![]() arcmin

only ``standard'' MOND model with tangential anisotropies can provide a

successful fit of the observed velocity dispersion without the need of

dark matter.

arcmin

only ``standard'' MOND model with tangential anisotropies can provide a

successful fit of the observed velocity dispersion without the need of

dark matter.

Key words: galaxies: elliptical and lenticular, cD - galaxies: kinematics and dynamics - galaxies: halos

1 Introduction

The problem of dark matter in early-type galaxies is still poorly understood. The reasons for this are numerous and are described in the literature (see e.g. Samurovic 2007, for a review), so we here only briefly list several of the most important ones.

- 1)

- The luminosity of early-type galaxies in their outer parts is

very low, which makes observations very difficult. Because of this only

a very small number of early-type galaxies has been observed out to

3-4 effective radii to infer their internal kinematics (

is the radius which encompasses half of the total light of a given galaxy; 3

is the radius which encompasses half of the total light of a given galaxy; 3 contains

contains  per cent and

per cent and

contains

contains  per cent of the total galactic light, according to the de Vaucouleurs

law). Long-slit spectra used for obtaining internal kinematics are

convenient because they also provide an information regarding stellar

anisotropies, which is important for breaking the mass-anisotropy

degeneracy (Tonry 1983).

There are fortunately other methods that can be used for kinematical

studies of early-type galaxies, and they are briefly given in the next

two items.

per cent of the total galactic light, according to the de Vaucouleurs

law). Long-slit spectra used for obtaining internal kinematics are

convenient because they also provide an information regarding stellar

anisotropies, which is important for breaking the mass-anisotropy

degeneracy (Tonry 1983).

There are fortunately other methods that can be used for kinematical

studies of early-type galaxies, and they are briefly given in the next

two items. - 2)

- X-rays studies

(see Mathews & Brighenti 2003a, for a review) are very useful because they can trace the gravitational potential out to large galactocentric distances (

)

without the aforementioned problem of anisotropies of orbits. The

drawbacks also exist however: this methodology is based on the

assumption of hydrostatic equilibrium, which has been disputed

(e.g. Diehl & Statler 2007), and not all early-type galaxies possess an X-ray halo (e.g. IC 3370, see Samurovic & Danziger 2005).

)

without the aforementioned problem of anisotropies of orbits. The

drawbacks also exist however: this methodology is based on the

assumption of hydrostatic equilibrium, which has been disputed

(e.g. Diehl & Statler 2007), and not all early-type galaxies possess an X-ray halo (e.g. IC 3370, see Samurovic & Danziger 2005).

- 3)

- Different tracers of the gravitational potential like globular

clusters (GCs) and planetary nebulae (PNe) are useful because they also

yield results out to large galactocentric distances (again,

)

(Romanowsky et al. 2003;

Schuberth et al. 2009). Note that the drawbacks here are also

numerous: because one needs a large number of the tracers per bin, it

is not possible to accurately determine the anisotropies of these

objects, and one can have hints at most regarding the orbits of the

tracers. The numbers of tracers also decreases in the outer parts of

early-type galaxies, and these are the regions where dark matter is

expected to dominate luminous matter. Additional problems may be seen

when one uses GCs as tracers: there are two different populations, blue

and red, for which the properties (like dispersion) may differ (see

e.g. Richtler et al. 2004), thus reducing the number of tracers used per bin. For PNe all the observed objects are assumed to belong to one population.

)

(Romanowsky et al. 2003;

Schuberth et al. 2009). Note that the drawbacks here are also

numerous: because one needs a large number of the tracers per bin, it

is not possible to accurately determine the anisotropies of these

objects, and one can have hints at most regarding the orbits of the

tracers. The numbers of tracers also decreases in the outer parts of

early-type galaxies, and these are the regions where dark matter is

expected to dominate luminous matter. Additional problems may be seen

when one uses GCs as tracers: there are two different populations, blue

and red, for which the properties (like dispersion) may differ (see

e.g. Richtler et al. 2004), thus reducing the number of tracers used per bin. For PNe all the observed objects are assumed to belong to one population.

Table 1: Kinematics data for NGC 5128 for the sample of PNe.

A new, promising avenue to address the problem of dark matter in

early-type galaxies is to use an integral-field unit to measure the

line-of-sight

velocity distribution (LOSVD) at large radii (

![]() )

(Weijmans et al. 2009).

)

(Weijmans et al. 2009).

So far the evidence of dark matter in early-type galaxies is inconclusive. Some galaxies appear to be devoid of it, or are dominated by certain types of orbits (the example of this class is NGC 3379, for which there is a lack of dark matter or dominance of radial orbits; see Romanowsky et al. 2003; Dekel et al. 2005), whereas some appear to possess huge massive dark halos (NGC 1399, see e.g. Samurovic & Danziger 2006; Schuberth et al. 2009). It is important to note that NGC 3379 is a relatively isolated object (part of the Leo I group) and NGC 1399 is a central galaxy of the Fornax cluster, which makes a direct comparison difficult.

The apparent lack of dark matter in NGC 3379 led researchers to

initiate the study of early-type galaxies within the context of the

MOND theory (Milgrom 1983). As was to be expected, the MOND models described NGC 3379 on all scales(Tiret et al. 2007). On the other hand, the MOND models failed to reproduce the kinematics of NGC 1399, and Richtler et al. (2008)

concluded that the MOND models needed an ``additional hypothetical dark

halo'', which of course makes MOND redundant. Samurovic & Cirkovic (2008) studied NGC 4649 (M60), a giant elliptical galaxy in the Virgo cluster, and concluded that out to

![]() the successful fit to the observed velocity dispersion can be obtained with the constant mass-to-light ratio in the B-band:

the successful fit to the observed velocity dispersion can be obtained with the constant mass-to-light ratio in the B-band:

![]() implying an absence or only a very low amount of dark matter in its

outer parts. The MOND models with similar mass-to-light ratio also

provided successful fits. Therefore, based on this admittedly small

sample of early-type galaxies, one is led to conclude that when a

galaxy needs dark matter to explain its kinematics (i.e. when a

Newtonian approach fails), the MOND approach also has problems and

appears to be insufficient. Vice versa, when Newtonian

mass-follows-light models provide a successful description of the

kinematics, the MOND models also appear to be correct. Note that the

MOND models are also not insensitive to the mass-anisotropy degeneracy,

because the Jeans equation, which needs to be solved, contains a term

pertaining to the form of orbits (see below).

implying an absence or only a very low amount of dark matter in its

outer parts. The MOND models with similar mass-to-light ratio also

provided successful fits. Therefore, based on this admittedly small

sample of early-type galaxies, one is led to conclude that when a

galaxy needs dark matter to explain its kinematics (i.e. when a

Newtonian approach fails), the MOND approach also has problems and

appears to be insufficient. Vice versa, when Newtonian

mass-follows-light models provide a successful description of the

kinematics, the MOND models also appear to be correct. Note that the

MOND models are also not insensitive to the mass-anisotropy degeneracy,

because the Jeans equation, which needs to be solved, contains a term

pertaining to the form of orbits (see below).

We study the galaxy NGC 5128, the nearest large elliptical

galaxy, using different constant mass-to-light ratio models. The

results of dynamical studies of NGC 5128 obtained so far suggest

the existence of dark matter: Mathieu et al. (1996) used a quadratic programming method to infer that the mass-to-light ratio increases from the center and that about ![]() per cent of the galaxy is dark; Peng et al. (2004) also concluded that about 50 per cent of the galaxy is dark and that

per cent of the galaxy is dark; Peng et al. (2004) also concluded that about 50 per cent of the galaxy is dark and that

![]() ,

but they note that the mass-to-light ratio they obtained is ``much

lower than what is typically expected for elliptical galaxy''. Recently

,

but they note that the mass-to-light ratio they obtained is ``much

lower than what is typically expected for elliptical galaxy''. Recently

![]() okas (2008) used the PNe data from Peng et al. (2004) and concluded that in the V-band,

okas (2008) used the PNe data from Peng et al. (2004) and concluded that in the V-band,

![]() ,

which in the B-band becomes

,

which in the B-band becomes

![]() (note the large error bars). We use PNe as tracers of the gravitational

potential and try to describe the kinematics of NGC 5128 without

inclusion of dark matter: we apply both the Newtonian and the MOND

approach in the spherical approximation allowing for anisotropies in

the motion of the tracers. Here, we try to answer the question whether

or not it is possible to model the observed velocity dispersion of an

early-type galaxy (in this case NGC 5128) without the inclusion of

dark matter; the related question about the largest galactocentric

radius for which dark matter is not needed is also addressed.

(note the large error bars). We use PNe as tracers of the gravitational

potential and try to describe the kinematics of NGC 5128 without

inclusion of dark matter: we apply both the Newtonian and the MOND

approach in the spherical approximation allowing for anisotropies in

the motion of the tracers. Here, we try to answer the question whether

or not it is possible to model the observed velocity dispersion of an

early-type galaxy (in this case NGC 5128) without the inclusion of

dark matter; the related question about the largest galactocentric

radius for which dark matter is not needed is also addressed.

The plan of the paper is as follows: in Sect. 2 we present the observational data related to NGC 5128; in Sect. 3 we solve the Jeans equation in both the Newtonian and the MOND approach to determine the best-fit parameters and infer the existence of dark matter; in Sect. 4 we present our conclusions.

2 Observational data

The galaxy NGC 5128 (also known as the radio source Centaurus A)

is the nearest large elliptical galaxy. It is the only massive

elliptical in the Centaurus group (Israel 1998).

The value of the distance used in this paper is

![]() Mpc (Rejkuba 2004). At this distance

Mpc (Rejkuba 2004). At this distance

![]() kpc,

which means that

kpc,

which means that

![]() pc.

We adopt for the center of the galaxy the following coordinates (

pc.

We adopt for the center of the galaxy the following coordinates (

![]()

![]() ,

J2000).

The effective radius is

,

J2000).

The effective radius is

![]() (=6.15 kpc) (van den Bergh 1976) and the systemic velocity used is

(=6.15 kpc) (van den Bergh 1976) and the systemic velocity used is

![]() km s-1.

The B-band luminosity of the stellar component NGC 5128 is

km s-1.

The B-band luminosity of the stellar component NGC 5128 is

![]() .

The review of the NGC 5128 galaxy is given in the paper by Israel (1998).

This galaxy is an excellent target for a detailed dynamical study

because of its proximity and different available observational data: we

will compare the results based on PNe and X-rays. Throughout the paper

we assume that the Hubble constant is h0=0.70.

.

The review of the NGC 5128 galaxy is given in the paper by Israel (1998).

This galaxy is an excellent target for a detailed dynamical study

because of its proximity and different available observational data: we

will compare the results based on PNe and X-rays. Throughout the paper

we assume that the Hubble constant is h0=0.70.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=6cm,clip]{13738fg1.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/06/aa13738-09/Timg44.png)

|

Figure 1:

Kinematics of NGC 5128 based on the sample of the PNe. From top to bottom: radial velocity of the PNe in

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

2.1 Planetary nebulae of NGC 5128

We use the sample of PNe from the paper by Peng et al. (2004), which contains 780 PNe. We present the kinematics of NGC 5128 based on the PNe in Table 1 and also in Fig. 1. Note that error bars are not plotted for the radial velocities: as given in Peng et al. (2004) they are taken to be 20 km s-1. The data for the PNe extend out to 78 arcmin (

![]() ), which is a very large galactocentric distance that encompasses approximately the total galactic light (more precisely,

), which is a very large galactocentric distance that encompasses approximately the total galactic light (more precisely, ![]() 98 per cent of the total light for the de Vaucouleurs model), which is important for our study of dark matter.

98 per cent of the total light for the de Vaucouleurs model), which is important for our study of dark matter.

The radial velocities of PNe were used to determine the kinematics of

NGC 5128: we calculated the velocity dispersion, the skewness and

kurtosis

parameters, s3 and s4, which

describe asymmetric and symmetric departures from the Gaussian in each

bin. We used standard definitions of the skewness and kurtosis

implemented in the NAG routine G01AAF. Negative values of kurtosis s4<0 imply tangential anisotropies and positive values of kurtosis s4>0

imply the dominance of radial orbits.

This has become a standard way of describing the anisotropies of given

tracers in early-type galaxies (see for example Schuberth et al.

2009, where GCs were analyzed in the galaxy NGC 1399). From

Table 1 and Fig. 1 one can see that the profile of the velocity dispersion is decreasing (apart from one anomalous point at ![]() arcmin);

we also notice a mild increase of the velocity dispersion in the last

bin. This will be analyzed in the next section, where we solve the

Jeans equation and model the velocity dispersion of NGC 5128. The

kurtotic parameter is small and it is safe to assume that there are no

large anisotropies; nevertheless we will also use some anisotropic

solutions in the next section to fully constrain the distribution of

matter in this early-type galaxy.

arcmin);

we also notice a mild increase of the velocity dispersion in the last

bin. This will be analyzed in the next section, where we solve the

Jeans equation and model the velocity dispersion of NGC 5128. The

kurtotic parameter is small and it is safe to assume that there are no

large anisotropies; nevertheless we will also use some anisotropic

solutions in the next section to fully constrain the distribution of

matter in this early-type galaxy.

For the Jeans modeling we also need the radial surface density

profile of the PNe in NGC 5128. This was given in Peng

et al. (2004) (see their Fig. 9), where they fitted the radial surface density with the expression

![]() and found that

and found that

![]() in the interval

in the interval

![]() kpc.

kpc.

2.2 X-ray data for NGC 5128

Kraft et al. (2003)

analyzed NGC 5128 based on the results from two Chandra/ACIS-I

observations and one XMM-Newton observation of X-ray emission from the

interstellar medium (ISM). They found that the ISM has an average

radial surface brightness profile that is well described by a ![]() -model profile with the index

-model profile with the index

![]() and a temperature

of

and a temperature

of

![]() keV beyond 2 kpc from the galactic nucleus.

Kraft et al. (2003) calculated that within 15 kpc of the nucleus the total mass of NGC 5128 is

keV beyond 2 kpc from the galactic nucleus.

Kraft et al. (2003) calculated that within 15 kpc of the nucleus the total mass of NGC 5128 is

![]() .

This value corresponds to the mass-to-light ratio

M/LB=6.70 at 15 kpc (

.

This value corresponds to the mass-to-light ratio

M/LB=6.70 at 15 kpc (

![]() ,

which is a region which contains 75 per cent of the total light for de Vaucouleurs law).

We note that this value is very close to that inferred from the stellar content (see Sect. 3.1).

,

which is a region which contains 75 per cent of the total light for de Vaucouleurs law).

We note that this value is very close to that inferred from the stellar content (see Sect. 3.1).

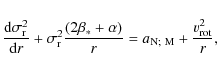

3 Dynamical models

For both the Newtonian and the MOND approach we solved the Jeans equation (e.g. Binney & Tremaine 2008):

where

where

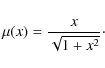

For all models calculated below, we used the projected line-of-sight velocity dispersion (e.g. Binney & Mamon 1982; Mathews & Brighenti 2003b) given as

where the truncation radius,

3.1 Newtonian mass-follows-light models

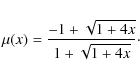

The case of NGC 5128 is an interesting one because this galaxy has a rather low stellar mass-to-light ratio. One may use the relation derived by Bell et al. (2003) (see their Table 7) to infer that mass-to-light ratio in the B-band in solar units is

M/LB=6.24 based on the color B-V=1.00 (value from the RC3 catalog, de Vaucouleurs et al. 1991).

This value is very close to that calculated with Eq. (7) from the paper by Cappellari

et al. (2006), who modeled 25 early-type galaxies out to

![]() and found a tight correlation between the mass-to-light ratio and the velocity dispersion. This equation in the B-band gives the following value for NGC 5128:

and found a tight correlation between the mass-to-light ratio and the velocity dispersion. This equation in the B-band gives the following value for NGC 5128:

![]() (here we used

(here we used

![]()

![]() for the value of the velocity dispersion within one effective radius).

for the value of the velocity dispersion within one effective radius).

Table 2:

Some fits for the Newtonian constant M/L ratio and the MOND isotropic (![]() )

and anisotropic (

)

and anisotropic (

![]() )

modeling.

)

modeling.

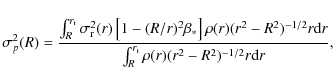

Since we deal in this work with constant mass-to-light ratio models, we

considered relations that include the stellar mass distributed in the

form of the standard Hernquist (1990) profile

which has two parameters: the total mass

We solved the Jeans Eq. (1) taking into account both isotropic (![]() )

and anisotropic (

)

and anisotropic (

![]() )

cases always assuming spherical symmetry. The isotropic cases are

obviously used here as a computational convenience, because in the

regions where rotational velocity is significant, the

)

cases always assuming spherical symmetry. The isotropic cases are

obviously used here as a computational convenience, because in the

regions where rotational velocity is significant, the ![]() parameter should be strongly negative.

The results are given in Table 2, where we present the best-fit values for some models for the mass-to-light ratio and the associated

parameter should be strongly negative.

The results are given in Table 2, where we present the best-fit values for some models for the mass-to-light ratio and the associated ![]() values. The rotational velocity of NGC 5128 varies with the

radius; as mentioned above we therefore divide the galaxy into two

regions:

the interior region (

values. The rotational velocity of NGC 5128 varies with the

radius; as mentioned above we therefore divide the galaxy into two

regions:

the interior region (![]() arcmin) where we take

arcmin) where we take

![]()

![]() (this is obviously a simplification, see Fig. 10 from the paper by Peng et al. 2004) and the exterior region

(r> 10 arcmin) where the velocity is approximately constant and equal to

(this is obviously a simplification, see Fig. 10 from the paper by Peng et al. 2004) and the exterior region

(r> 10 arcmin) where the velocity is approximately constant and equal to

![]()

![]() .

Note that beyond 10 arcmin the

.

Note that beyond 10 arcmin the ![]() values are rather high due to a sudden increase of the velocity dispersion at

values are rather high due to a sudden increase of the velocity dispersion at ![]() arcmin.

The results related to the successful fits of the outermost point are

marked with an asterisk and are characterized by higher values of

arcmin.

The results related to the successful fits of the outermost point are

marked with an asterisk and are characterized by higher values of ![]() .

.

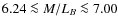

The best fit assuming an isotropy interior to ![]() arcmin was obtained for a mass-to-light ratio:

arcmin was obtained for a mass-to-light ratio:

![]() ,

which agrees with a value inferred from the stellar component. This

clearly means that dark matter does not necessarily have to extend out

to

,

which agrees with a value inferred from the stellar component. This

clearly means that dark matter does not necessarily have to extend out

to ![]() arcmin (

arcmin (

![]() )

if we assume isotropy.

Beyond

)

if we assume isotropy.

Beyond ![]() arcmin the mass-to-light ratio needs to increase if we are to fit the outermost point: in Fig. 2 we show two values,

M/LB=8.00 and

M/LB=16.00,

which roughly cover the whole permitted range; both values assume

the existence of the unseen mass component, small in the first case (

arcmin the mass-to-light ratio needs to increase if we are to fit the outermost point: in Fig. 2 we show two values,

M/LB=8.00 and

M/LB=16.00,

which roughly cover the whole permitted range; both values assume

the existence of the unseen mass component, small in the first case (![]() per cent) and significant in the second case (a dark component

per cent) and significant in the second case (a dark component ![]() 2.5 times larger than the stellar one).

2.5 times larger than the stellar one).

Although the testing of different dark matter halos is not the aim of

this paper, we decided to test two additional dark matter profiles (the

one based on the Hernquist profile was already tested above).

To infer the influence of dark matter we added to the mass generated by

the stellar component (

M/LB=6.24) two different dark halos.

In Fig. 2

we also show two fits obtained with two different models of dark halo

for isotropic orbits. The dashed line is obtained for the Burkert (1995) model with the following parameters:

![]() and r0=541 arcsec

(

and r0=541 arcsec

(

![]() kpc). One can see that the outermost point can be fitted implying

kpc). One can see that the outermost point can be fitted implying

![]() there; the points between 10 and 40 arcmin are not successfully

fitted (the quality of the fit between 10 and 60 arcmin is

characterized by

there; the points between 10 and 40 arcmin are not successfully

fitted (the quality of the fit between 10 and 60 arcmin is

characterized by

![]() ). The dot-dashed line is for the NFW (Navarro, Frank & White 1997) halo with

). The dot-dashed line is for the NFW (Navarro, Frank & White 1997) halo with

![]() and

and

![]() arcsec (

arcsec (![]() 14.4 kpc). The outermost point is well fitted (implying

14.4 kpc). The outermost point is well fitted (implying

![]() there); the points between 10 and 40 arcmin are again not

successfully fitted and the discrepancies are even larger than for the

Burkert model (the quality of the fit between 10 and 60 arcmin is

characterized by

there); the points between 10 and 40 arcmin are again not

successfully fitted and the discrepancies are even larger than for the

Burkert model (the quality of the fit between 10 and 60 arcmin is

characterized by

![]() ). Numerous other dark matter models are obviously possible and we refer the reader to the paper by Bullock et al. (2001), where various dark matter halo density profiles are studied in detail.

). Numerous other dark matter models are obviously possible and we refer the reader to the paper by Bullock et al. (2001), where various dark matter halo density profiles are studied in detail.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{13738fg2.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/06/aa13738-09/Timg95.png)

|

Figure 2:

Isotropic ( |

| Open with DEXTER | |

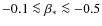

Since ![]() is essentially a free parameter in our study, we searched for the best value of

is essentially a free parameter in our study, we searched for the best value of ![]() for the value of the mass-to-light ratio inferred from the color of NGC 5128 (

M/LB=6.24). Therefore, when we solved the Jeans equation for the anisotropic case, we studied the cases for which

for the value of the mass-to-light ratio inferred from the color of NGC 5128 (

M/LB=6.24). Therefore, when we solved the Jeans equation for the anisotropic case, we studied the cases for which

![]() ,

thus allowing for moderate anisotropies as hinted by observations. The results are shown in Fig. 3.

In the innermost part (

,

thus allowing for moderate anisotropies as hinted by observations. The results are shown in Fig. 3.

In the innermost part (![]() ) arcmin a fit with

M/LB=6.24 and

) arcmin a fit with

M/LB=6.24 and

![]() can provide an agreement to the observed velocity dispersion.

Several fits with the mass-to-light ratio in the interval

can provide an agreement to the observed velocity dispersion.

Several fits with the mass-to-light ratio in the interval

![]() with moderate anisotropies provide good agreement with the observed velocity dispersion in the inner region (out to

with moderate anisotropies provide good agreement with the observed velocity dispersion in the inner region (out to ![]() arcmin) (see Fig. 3 and Table 2

for details). To fit the outermost point at 59 arcmin we used the

mass-to-light ratio inferred from the stellar component (

M/LB=6.24) and imposed tangential anisotropies (

arcmin) (see Fig. 3 and Table 2

for details). To fit the outermost point at 59 arcmin we used the

mass-to-light ratio inferred from the stellar component (

M/LB=6.24) and imposed tangential anisotropies (

![]() )

to avoid the inclusion of dark matter (the alternative is given earlier

when we fitted this point without anisotropies but with dark matter).

)

to avoid the inclusion of dark matter (the alternative is given earlier

when we fitted this point without anisotropies but with dark matter).

To summarize the conclusions for the Newtonian approach: the observed

velocity dispersion of NGC 5128 can be described without the need

of dark matter out to

![]() (=35 arcmin; a region that encompasses

(=35 arcmin; a region that encompasses ![]() per cent

of the total light for the de Vaucouleurs law). This is the largest

galactocentric distance in an early-type galaxy for which dark matter

is not necessary to explain its internal kinematics. The obtained value

of the mass-to-light ratio (

per cent

of the total light for the de Vaucouleurs law). This is the largest

galactocentric distance in an early-type galaxy for which dark matter

is not necessary to explain its internal kinematics. The obtained value

of the mass-to-light ratio (

![]() )

agrees with the value inferred from the X-rays (Kraft et al. 2003).

In the outer region of NGC 5128,

)

agrees with the value inferred from the X-rays (Kraft et al. 2003).

In the outer region of NGC 5128,

![]() (=78 arcmin)

we encountered an increasing velocity dispersion, which implies an

increase of the mass-to-light ratio (or tangential anisotropies)

implying certain amounts of dark matter in these regions (if any). An

important remark is necessary at this point: as the

(=78 arcmin)

we encountered an increasing velocity dispersion, which implies an

increase of the mass-to-light ratio (or tangential anisotropies)

implying certain amounts of dark matter in these regions (if any). An

important remark is necessary at this point: as the ![]() parameter, which was calculated by Peng et al. (2004), is valid for the region interior to

parameter, which was calculated by Peng et al. (2004), is valid for the region interior to ![]() 40 arcmin,

any conclusion regarding both isotropic and anisotropic Newtonian

models pertaining to the outermost region (beyond

40 arcmin,

any conclusion regarding both isotropic and anisotropic Newtonian

models pertaining to the outermost region (beyond ![]() 40) arcmin must therefore be taken with a great caution (the same remark is obviously also valid for the MOND modeling).

40) arcmin must therefore be taken with a great caution (the same remark is obviously also valid for the MOND modeling).

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{13738fg3.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/06/aa13738-09/Timg102.png)

|

Figure 3:

Anisotropic (

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

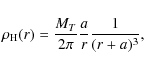

3.2 MOND models

In our MOND models we use three different

formulas: (i) the ``simple'' MOND formula from Famaey & Binney

(2005); (ii) the ``standard'' formula (Sanders & McGaugh 2002);

and (iii) the Bekenstein's ``toy'' model (Bekenstein 2004). The Newtonian acceleration is given as

![]() ,

where a is

the MOND acceleration. As usual,

,

where a is

the MOND acceleration. As usual, ![]() is the MOND interpolating

function, where

is the MOND interpolating

function, where

![]() ,

and

,

and

![]()

![]() is a universal constant (Famaey

et al. 2007). For

is a universal constant (Famaey

et al. 2007). For ![]() the interpolation function

the interpolation function

![]() and the Newtonian relation is recovered; for

and the Newtonian relation is recovered; for ![]() we have

we have ![]() .

It can be shown (e.g. Angus et al. 2008) that the MOND dynamical mass,

.

It can be shown (e.g. Angus et al. 2008) that the MOND dynamical mass, ![]() ,

can be

expressed in terms of the Newtonian mass,

,

can be

expressed in terms of the Newtonian mass, ![]() through

through

We assume different forms of the interpolation function for different MOND models (the expressions for the circular velocities are given in Samurovic & Cirkovic 2008).

- 1.

- A ``simple'' MOND formula is given by

- 2.

- A ``standard'' MOND formula is given by

- 3.

- Finally, for the ``toy'' model the MOND formula is given as

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{13738fg4.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/06/aa13738-09/Timg118.png)

|

Figure 4:

Isotropic ( |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{13738fg5.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/06/aa13738-09/Timg119.png)

|

Figure 5:

Anisotropic (

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

Again we divided the galaxy into two regions: the interior region (![]() arcmin and

arcmin and

![]()

![]() )

and the exterior region (r> 10 arcmin and

)

and the exterior region (r> 10 arcmin and

![]()

![]() ). Only the ``standard'' MOND model with (

). Only the ``standard'' MOND model with (

![]() )

may provide a good fit without anisotropy. Both the ``simple'' and the

``toy'' models require much larger mass-to-light ratios in this region

(see Fig. 4). For the isotropic case we found that the ``standard'' MOND model with the mass-to-light ratio inferred from the stellar content (

M/LB=6.24) again provides better fits

between 10 and 40 arcmin than the ``simple'' and ``toy'' models

(with the same mass-to-light ratio), but it is still far from perfect

(not shown, but presented in Table 2). If one wants to fit points beyond

)

may provide a good fit without anisotropy. Both the ``simple'' and the

``toy'' models require much larger mass-to-light ratios in this region

(see Fig. 4). For the isotropic case we found that the ``standard'' MOND model with the mass-to-light ratio inferred from the stellar content (

M/LB=6.24) again provides better fits

between 10 and 40 arcmin than the ``simple'' and ``toy'' models

(with the same mass-to-light ratio), but it is still far from perfect

(not shown, but presented in Table 2). If one wants to fit points beyond

![]() arcmin in the ``standard'' model one needs to increase the mass-to-light ratio: a fit for which

M/LB=9.00 is shown in the same figure.

Even this high value (which includes a certain amount,

arcmin in the ``standard'' model one needs to increase the mass-to-light ratio: a fit for which

M/LB=9.00 is shown in the same figure.

Even this high value (which includes a certain amount, ![]() percent of unseen matter) cannot provide a fit for the points in the interval

percent of unseen matter) cannot provide a fit for the points in the interval

![]() arcmin.

For the ``simple'' and ``toy'' models the increase of the mass-to-light

ratio to 9.00 and 12.00 respectively does improve the fits: the points

interior to

arcmin.

For the ``simple'' and ``toy'' models the increase of the mass-to-light

ratio to 9.00 and 12.00 respectively does improve the fits: the points

interior to ![]() arcmin are fitted, but those beyond

arcmin are fitted, but those beyond ![]() arcmin

cannot be fitted, which implies even higher values of the

mass-to-light, meaning that more unseen (dark) matter is necessary in

those regions. None of the three isotropic MOND models can provide a

fit for the outermost point with stellar mass-to-light ratio, which

suggests that in order to fit the outermost point one needs to assume

anisotropy of the tracers (PNe).

arcmin

cannot be fitted, which implies even higher values of the

mass-to-light, meaning that more unseen (dark) matter is necessary in

those regions. None of the three isotropic MOND models can provide a

fit for the outermost point with stellar mass-to-light ratio, which

suggests that in order to fit the outermost point one needs to assume

anisotropy of the tracers (PNe).

In Fig. 5 we present different anisotropic MOND models; our goal again was to find acceptable models that would provide reasonable fits in both inner

(0<r<40 arcmin) and outer (r>40 arcmin) regions.

In the innermost region (![]() arcmin) we found that

arcmin) we found that

![]() and various tangential anisotropies may provide a good fit to the observed velocity dispersion.

From Fig. 5 one can see that ``standard'' MOND models based on the

mass-to-light ratio inferred from the stellar content (

M/LB=6.24) provide a satisfactory fit for the whole region interior to

and various tangential anisotropies may provide a good fit to the observed velocity dispersion.

From Fig. 5 one can see that ``standard'' MOND models based on the

mass-to-light ratio inferred from the stellar content (

M/LB=6.24) provide a satisfactory fit for the whole region interior to ![]() arcmin: the model with a moderate tangential anisotropy (

arcmin: the model with a moderate tangential anisotropy (![]() 0.30) provides a fit interior to

0.30) provides a fit interior to ![]() 10 arcmin and the model with a stronger tangential anisotropy (

10 arcmin and the model with a stronger tangential anisotropy (

![]() )

provides a fit for

)

provides a fit for

![]() arcmin.

This is the unique case we have encountered in the MOND modeling when

one does not need dark matter to successfully fit the observed velocity

dispersions of NGC 5128 out to

arcmin.

This is the unique case we have encountered in the MOND modeling when

one does not need dark matter to successfully fit the observed velocity

dispersions of NGC 5128 out to ![]() 40 arcmin.

The MOND ``simple'' (with

M/LB=6.24) and ``toy'' (with

M/LB=7.00) models with significant tangential anisotropies can provide a fit in the innermost region (interior to

40 arcmin.

The MOND ``simple'' (with

M/LB=6.24) and ``toy'' (with

M/LB=7.00) models with significant tangential anisotropies can provide a fit in the innermost region (interior to ![]() arcmin;

arcmin; ![]() 0.60; see Fig. 5) and beyond (

0.60; see Fig. 5) and beyond (

![]() arcmin; with

arcmin; with ![]() 0.50) for

M/LB=9.00 (both models). As for the

isotropic case it is obvious that in order to fit the observed data in

the region between 10 and 40 arcmin one needs at least 30 per

cent of dark matter for both the ``simple'' and ``toy'' models. We

again could not obtain successful fits of the observed velocity

dispersion in the last bin; to do this one needs

0.50) for

M/LB=9.00 (both models). As for the

isotropic case it is obvious that in order to fit the observed data in

the region between 10 and 40 arcmin one needs at least 30 per

cent of dark matter for both the ``simple'' and ``toy'' models. We

again could not obtain successful fits of the observed velocity

dispersion in the last bin; to do this one needs

![]() and significant tangential anisotropies (

and significant tangential anisotropies (

![]() ).

However, regarding the fit of the outermost point we repeat our earlier

observation with regard to Newtonian models because it is still valid:

fits obtained with

).

However, regarding the fit of the outermost point we repeat our earlier

observation with regard to Newtonian models because it is still valid:

fits obtained with

![]() are uncertain because this parameter was obtained in the region beyond

are uncertain because this parameter was obtained in the region beyond ![]() arcmin.

arcmin.

The overall conclusion regarding MOND models is that interior to ![]() arcmin

only a ``standard'' MOND model with tangential anisotropies can provide

a successful fit of the observed velocity dispersion without the need

of dark matter.

Both the ``simple'' and ``toy'' models need at least

arcmin

only a ``standard'' MOND model with tangential anisotropies can provide

a successful fit of the observed velocity dispersion without the need

of dark matter.

Both the ``simple'' and ``toy'' models need at least ![]() per cent of dark matter to obtain a fit in this region.

per cent of dark matter to obtain a fit in this region.

3.3 Newtonian and MOND models with a radially varying  -parameter

-parameter

We follow here the recommendation of the referee and model the galaxy NGC 5128 using a ![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{13738fg6.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/06/aa13738-09/Timg130.png)

|

Figure 6:

Anisotropic modeling of NGC 5128 with

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

4 Conclusions

We used PNe kinematics of the well-known early-type galaxy NGC 5128 to model the observed velocity dispersions out to ![]() 59 arcmin (

59 arcmin (

![]() ).

We solved the Jeans equations for various Newtonian mass-follows-light

and MOND models assuming both isotropy and anisotropy in the spherical

approximation in order to study the existence of dark matter in this

early-type galaxy. Our conclusions are as follows:

).

We solved the Jeans equations for various Newtonian mass-follows-light

and MOND models assuming both isotropy and anisotropy in the spherical

approximation in order to study the existence of dark matter in this

early-type galaxy. Our conclusions are as follows:

- 1.

- We studied the kinematics of NGC 5128 and found that the velocity dispersion decreases from

near the center to

near the center to

at 35 arcmin (

at 35 arcmin (

)

and then increases at 59 arcmin (=

)

and then increases at 59 arcmin (=

)

to

)

to

.

We calculated both skewness and kurtosis, which are not significant,

which implies that the orbits of PNe in NGC 5128 are close to

isotropic.

Nevertheless, in our models we allowed for certain anisotropies.

.

We calculated both skewness and kurtosis, which are not significant,

which implies that the orbits of PNe in NGC 5128 are close to

isotropic.

Nevertheless, in our models we allowed for certain anisotropies.

- 2.

- We solved the Jeans equation for the Newtonian

mass-follows-light models assuming both isotropy and anisotropy in the

spherical approximation.

We found that assuming isotropy successful fits interior to

arcmin were obtained for

arcmin were obtained for

,

which agrees with a value inferred from the stellar component and also

with the X-rays (out to 15 arcmin). To fit the outermost point at

59 arcmin in the Newtonian mass-follows-light models one needs

either additional unseen (dark) matter or tangential anisotropies,

although the fit of this point is marginally consistent with the

observations when we assume a radially varying anisotropy of the form

,

which agrees with a value inferred from the stellar component and also

with the X-rays (out to 15 arcmin). To fit the outermost point at

59 arcmin in the Newtonian mass-follows-light models one needs

either additional unseen (dark) matter or tangential anisotropies,

although the fit of this point is marginally consistent with the

observations when we assume a radially varying anisotropy of the form

based on the observed anisotropies. In any case, it is safe to conclude that interior to

based on the observed anisotropies. In any case, it is safe to conclude that interior to

one does not need dark matter to explain the observed velocity

dispersion of NGC 5128. This is the largest galactocentric

distance in any early-type galaxy for which dark matter is not

necessary to explain its internal kinematics.

one does not need dark matter to explain the observed velocity

dispersion of NGC 5128. This is the largest galactocentric

distance in any early-type galaxy for which dark matter is not

necessary to explain its internal kinematics. - 3.

- We also solved the Jeans equation for various MOND models,

again assuming both isotropy and anisotropy in the spherical

approximation. No isotropic MOND model without dark matter could

provide a successful fit interior to

arcmin.

For the anisotropic MOND models interior to

arcmin.

For the anisotropic MOND models interior to  40 arcmin

only the ``standard'' MOND model with tangential anisotropies can

provide a successful fit of the observed velocity dispersion without

the need of dark matter

(using

M/LB=6.24 and

40 arcmin

only the ``standard'' MOND model with tangential anisotropies can

provide a successful fit of the observed velocity dispersion without

the need of dark matter

(using

M/LB=6.24 and

).

Both the ``simple'' and ``toy'' models need at least

).

Both the ``simple'' and ``toy'' models need at least  per

cent of dark matter to obtain a fit in this region. No anisotropic MOND

model with low values of the mass-to-light ratio (i.e. based on the

stellar content only) could fit the outermost region of NGC 5128.

No MOND model with radially varying anisotropy based on the

observations,

per

cent of dark matter to obtain a fit in this region. No anisotropic MOND

model with low values of the mass-to-light ratio (i.e. based on the

stellar content only) could fit the outermost region of NGC 5128.

No MOND model with radially varying anisotropy based on the

observations,

,

could fit the regions beyond

,

could fit the regions beyond  arcmin.

arcmin.

The author thanks M.M. Cirkovic for numerous interesting discussions. This work was supported by the Ministry of Science of the Republic of Serbia through the project no. 146012, ``Gaseous and stellar component of galaxies: interaction and evolution''. This research made use of the NASA/IPAC Extragalactic Database (NED), which is operated by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, under contract with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. We acknowledge the usage of the HyperLeda database (http://leda.univ-lyon1.fr). The author gratefully acknowledges the valuable comments of the anonymous referee, which helped to improve the quality of the manuscript.

References

- Angus, G. W., Famaey, B., & Buote, D. A. 2008, MNRAS, 387, 1470 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bekenstein, J. 2004, Phys. Rev. D, 70, 083509 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bell, E. F., McIntosh, D. H., Katz, N., & Weinberg, M. D., ApJSS, 149, 289 [Google Scholar]

- Binney, J. J., & Mamon, G. 1982, MNRAS, 200, 361 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Binney, J. J., & Tremaine, S. 2008, Galactic Dynamics, 2nd edn. (Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press) [Google Scholar]

- Bullock, J. S., Kolatt, T. S., Sigad, Y. et al. 2001, MNRAS, 321, 559 [Google Scholar]

- Burkert, A. 1995, ApJ, 447, L25 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cappellari, M., Bacon, R., Bureau, M. et al. 2006, MNRAS, 366, 1126 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- de Vaucouleurs, G., de Vaucouleurs, A. Corwin, H. G. Jr., et al. 1991, Third Reference Catalogue of Bright Galaxies (New York: Springer-Verlag) [Google Scholar]

- Dekel, A., Stoehr, F., Mamon, G. A., Cox, T. J. & Primack, J. R. 2005, Nature, 437, 707 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehl, S., & Statler, T. S. 2007, ApJ, 668, 150 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Famaey, B., & Binney, J. 2005, MNRAS, 363, 603 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Famaey, B., Gentile, G., Bruneton, J.-P., & Zhao, H. S. 2007, Phys. Rev. D, 75, 063002 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhard, O. 1993, MNRAS, 265, 213 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hernquist, L. 1990, ApJ, 356, 359 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Israel, F. P. 1998, A&A R, 8, 237 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kraft, R. P., Forman, W. R., Jones, C., et al. 2003, ApJ, 592, 129 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ▯okas, E. W. 2008, MNRAS, 680, L101 [Google Scholar]

- Mathews, W. G., & Brighenti, F. 2003a, ARA&A, 41, 191 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews, W. G., & Brighenti, F. 2003b, ApJ, 599, 992 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mathieu, A., Dejonghe, H., & Hui, X. 1996, A&A, 309, 30 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Milgrom, M. 1983, ApJ, 270, 365 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro, J. F., Frenk, C. S., & White, S. D.M. 1997, ApJ, 490, 493 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Peng, E. W., Ford, H. C., & Freeman, K. C. 2004, ApJ, 602, 685 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Rejkuba, M. 2004, A&A, 413, 903 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Richtler T., Dirsch B., Gebhardt K., et al. 2004, AJ, 127, 2094 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Richtler, T, Schuberth, Y., Hilker, M., et al. 2008, A&A, 478, L23 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Romanowsky, A. J., Douglas, N. G., Arnaboldi, M., et al. 2003, Science, 5640, 1696 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samurovic, S. 2007, Dark Matter in Elliptical Galaxies, Publications of the Astronomical Observatory of Belgrade, No. 81. [Google Scholar]

- Samurovic, S., & Danziger, I. J. 2005, MNRAS, 363, 769 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Samurovic, S., & Danziger, I. J. 2006, A&A, 458, 79 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Samurovic, S., & Cirkovic M. M. 2008, A&A, 488, 873 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders, R. H., & McGaugh, S. 2002, ARA&A, 40, 263 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Schuberth, Y., Richtler, T., Hilker, M., et al. 2010, A&A, 513, A52 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Tiret, O., Combes, F., Angus, G. W., Famaey, B., & Zhao, H. S. 2007, A&A, 476, L1 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Tonry, J. L. 1983, ApJ, 266, 58 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- van den Bergh, S. 1976, ApJ, 208, 673 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- van der Marel, R. P. 1991, MNRAS, 253, 710 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Weijmans, A., Cappellari, M., Bacon, R. et al. 2009, MNRAS, 398, 561 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

All Tables

Table 1: Kinematics data for NGC 5128 for the sample of PNe.

Table 2:

Some fits for the Newtonian constant M/L ratio and the MOND isotropic (![]() )

and anisotropic (

)

and anisotropic (

![]() )

modeling.

)

modeling.

All Figures

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=6cm,clip]{13738fg1.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/06/aa13738-09/Timg44.png)

|

Figure 1:

Kinematics of NGC 5128 based on the sample of the PNe. From top to bottom: radial velocity of the PNe in

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{13738fg2.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/06/aa13738-09/Timg95.png)

|

Figure 2:

Isotropic ( |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{13738fg3.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/06/aa13738-09/Timg102.png)

|

Figure 3:

Anisotropic (

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{13738fg4.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/06/aa13738-09/Timg118.png)

|

Figure 4:

Isotropic ( |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{13738fg5.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/06/aa13738-09/Timg119.png)

|

Figure 5:

Anisotropic (

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{13738fg6.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/06/aa13738-09/Timg130.png)

|

Figure 6:

Anisotropic modeling of NGC 5128 with

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

Copyright ESO 2010

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.