| Issue |

A&A

Volume 514, May 2010

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A82 | |

| Number of page(s) | 7 | |

| Section | The Sun | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/200912907 | |

| Published online | 26 May 2010 | |

Soft X-ray coronal spectra at low activity levels observed by RESIK

B. Sylwester1 - J. Sylwester1 - K. J. H. Phillips2

1 - Space Research Center, Polish Academy of Sciences, Kopernika 11,

51-622 Wroc![]() aw, Poland

aw, Poland

2 - UCL-Mullard Space Science Laboratory, Holmbury St. Mary, Dorking,

Surrey RH5 6NT, UK

Received 16 July 2009 / Accepted 1 February 2010

Abstract

Context. The quiet-Sun X-ray emission is important

for deducing coronal heating mechanisms, but it has not been studied in

detail since the Orbiting Solar Observatory (OSO)

spacecraft era. Bragg crystal spectrometer X-ray observations have

generally concentrated on flares and active regions. The high

sensitivity of the RESIK (REntgenovsky Spectrometer s Izognutymi

Kristalami) instrument on the CORONAS-F solar

mission has enabled the X-ray emission from the quiet corona to be

studied in a systematic way for the first time.

Aims. Our aim is to deduce the physical conditions

of the non-flaring corona from RESIK line intensities in several

spectral ranges using both isothermal and multithermal assumptions.

Methods. We selected and analyzed spectra in

312 quiet-Sun intervals in January and February 2003, sorting

them into 5 groups according to activity level. For each

group, the fluxes in selected spectral bands have been used to

calculate values of parameters for the best-fit that leads to

intensities characteristic of each group. We used both isothermal and

multitemperature assumptions, the latter described by differential

emission measure (DEM) distributions. RESIK spectra cover the

wavelength range (3.3-6.1 Å). This includes emission lines of

highly ionized Si, S, Cl, Ar, and K, which are suitable for

evaluating temperature and emission measure, were used.

Results. The RESIK spectra during these intervals of

very low solar activity for the first time provide information on the

temperature structure of the quiet corona. Although most of the

emission seems to arise from plasma with a temperature between

2 MK and 3 MK, there is also evidence of a hotter

plasma (![]() MK)

with an emission measure 3 orders smaller than the cooler

component. Neither coronal nor photospheric element abundances appear

to describe the observed spectra satisfactorily.

MK)

with an emission measure 3 orders smaller than the cooler

component. Neither coronal nor photospheric element abundances appear

to describe the observed spectra satisfactorily.

Key words: Sun: X-rays, gamma rays - Sun: abundances - Sun: corona

1 Introduction

The RESIK X-ray spectrometer on the Russian CORONAS-F

solar

orbiting mission (circular polar orbit: altitude 550 km,

period 96 min) obtained numerous high-resolution flare and

active-region spectra in the 3.3-6.1 Å range over the period

August 2001-May 2003. The RESIK instrument (Sylwester

et al. 2005)

was a bent crystal spectrometer with four spectral channels in which

solar X-ray emission was diffracted by crystal wafers made of

silicon (Si 111, 2d = 6.27 Å) and quartz

(Qu ![]() ,

2d =

8.51 Å). Although most previous spacecraft crystal

spectrometers

suffered from the strong instrumental backgrounds caused by

fluorescence of the crystal material, RESIK had a system of

pulse-height analyzers enabling primary solar photons to be

distinguished from secondary photons produced by fluorescence. The

background could thus be practically eliminated for much of the

period 2003 January-March when the non flaring solar X-ray

activity was often below C1 class as measured by the GOES

1-8 Å sensor. The sensitivity of RESIK was maximized by not

having a collimator placed in front of the crystals. This, like the

equivalent Bragg Crystal Spectrometer on the Yohkoh

spacecraft

(operational 1991-2001), produced some spectral confusion when two

simultaneous bright sources were present on the Sun, but in practice

this rarely occurred. The low-activity corona gives rise to X-ray

line profiles in RESIK spectra having large line widths through

spatial broadening.

,

2d =

8.51 Å). Although most previous spacecraft crystal

spectrometers

suffered from the strong instrumental backgrounds caused by

fluorescence of the crystal material, RESIK had a system of

pulse-height analyzers enabling primary solar photons to be

distinguished from secondary photons produced by fluorescence. The

background could thus be practically eliminated for much of the

period 2003 January-March when the non flaring solar X-ray

activity was often below C1 class as measured by the GOES

1-8 Å sensor. The sensitivity of RESIK was maximized by not

having a collimator placed in front of the crystals. This, like the

equivalent Bragg Crystal Spectrometer on the Yohkoh

spacecraft

(operational 1991-2001), produced some spectral confusion when two

simultaneous bright sources were present on the Sun, but in practice

this rarely occurred. The low-activity corona gives rise to X-ray

line profiles in RESIK spectra having large line widths through

spatial broadening.

Several analyses have been done on spectra of solar flares from RESIK (Sylwester et al. 2006a; Chifor et al. 2007; Sylwester et al. 2008), but here we report on spectra obtained during a period of sustained low solar activity, which have high statistical quality because of the relatively high sensitivity of RESIK. The observed spectral shapes including continua are available for analysis of the temperature structure of the emitting regions, specifically the differential emission measure as a function of electron temperature T; and from this, the absolute abundances of the elements giving rise to the spectral lines can be assessed.

Quiet-Sun X-ray spectra have not received nearly as much

attention

in the past as those from flares, but some properties of the quiet

Sun have been widely studied using its ultraviolet emission, which

has been measured by the following experiments: Orbiting Solar

Observatory OSO series (1962-1975; see for

instance Dupree & Reeves 1971; Dupree

et al. 1973),

Aerobee rocket

spectrometer (1969, see Malinovsky & Heroux 1973),

9 months of

the Skylab mission

(May 1973-February 1974, see Vernazza &

Reeves 1978),

the series of 9 Solar EUV Rocket Telescope and

Spectrograph (SERTS) flights (the first in 1989, see Brosius

et al.

1996, 1998), the SOHO

mission (starting in December 1995, CDS

and SUMER data, see Warren et al. 1998). The data

obtained have been used as well to construct a reference atlas of

quiet-Sun ultraviolet radiation (Curdt et al. 2004)

from which differential emission measure (DEM) distributions can be

inferred. Brosius et al. (1996)

calculated DEM distributions for

quiet-Sun conditions during two observing periods near the maximum

of Cycle 21 (1991 May 7 and

1993 August 17) based on SERTS data.

Their DEM solutions included a power law in the temperature range

![]() K-

K-

![]() K with hot plasma as

shown by a

localized maximum at 5 MK. A DEM with similar distribution was

obtained by Kretzschmar et al. (2004) based

on

SOHO SUMER data, having a power-law shape in the

range

K with hot plasma as

shown by a

localized maximum at 5 MK. A DEM with similar distribution was

obtained by Kretzschmar et al. (2004) based

on

SOHO SUMER data, having a power-law shape in the

range

![]() -

-

![]() K with a

high-temperature bump

at 1.1 MK. Ralchenko et al. (2007) have

studied

quiet-corona spectra as observed by SUMER during the

2000 June 13-19 period, deducing that the observed

line intensities can be

satisfactorily described by a model with two Maxwellian electron

distributions, a first population corresponding to an isothermal

temperature of

K with a

high-temperature bump

at 1.1 MK. Ralchenko et al. (2007) have

studied

quiet-corona spectra as observed by SUMER during the

2000 June 13-19 period, deducing that the observed

line intensities can be

satisfactorily described by a model with two Maxwellian electron

distributions, a first population corresponding to an isothermal

temperature of ![]()

![]() K, and a second,

smaller

population (

K, and a second,

smaller

population (![]()

![]() )

of hot (300-400 eV) electrons accounting

for the intensities of highly charged Ar and Ca ion lines observed

by SUMER. The DEM analysis was also performed using SOHO

Coronal

Diagnostic Spectrometer (CDS) data for the internetwork, network,

and bright network regions of the quiet Sun by O'Shea et al. (2000).

They find that the DEM distributions differ in each region over the

temperature range 0.25-1 MK.

)

of hot (300-400 eV) electrons accounting

for the intensities of highly charged Ar and Ca ion lines observed

by SUMER. The DEM analysis was also performed using SOHO

Coronal

Diagnostic Spectrometer (CDS) data for the internetwork, network,

and bright network regions of the quiet Sun by O'Shea et al. (2000).

They find that the DEM distributions differ in each region over the

temperature range 0.25-1 MK.

Recently, Young et al. (2007) have published a quiet-Sun extreme ultraviolet (EUV) spectrum in the ranges 170-211 Å and 246-292 Å, as observed on 2006 December 23 by the Hinode EUV Imaging Spectrometer (EIS).

The quiet-Sun hard X-ray emission observed by RHESSI

has been

examined by Hannah et al. (2007) using a

fan-beam modulation

technique during seven periods of off-pointing of the RHESSI

spacecraft between 2005 June and 2006 October. They

established new

upper limits on the 3-200 keV X-ray emission for when the

GOES level of activity was below

A1 class, updating much

earlier measurements (Peterson et al. 1966). Schmelz

et al. (2010)

have investigated the emission of a nonflaring active region based

on the ten filters of the Hinode X-ray Telescope

data using

two independent algorithms to reconstruct the differential emission

measure distribution. In addition to the typical

low-temperature

emission measure (T<5 MK), they find

a very hot component (![]() 30 MK)

with small emission measure. These findings have recently

been modified by Schmelz (2009, priv. comm.): the temperature of the

hotter component is now much lower, around 10 MK. Reale

et al.

(2009) have

investigated the Hinode XRT data averaged over

one hour during a nonflaring period (2006 November 12),

finding a

hotter component (temperature

30 MK)

with small emission measure. These findings have recently

been modified by Schmelz (2009, priv. comm.): the temperature of the

hotter component is now much lower, around 10 MK. Reale

et al.

(2009) have

investigated the Hinode XRT data averaged over

one hour during a nonflaring period (2006 November 12),

finding a

hotter component (temperature ![]() 6.3 MK) corresponding to a

nonflaring active region. These observational results are supported

by the theoretical work of Klimchuk et al. (2008) who use

hydrodynamic simulations of nanoflares to predict a small amount of

hot plasma in addition to the dominant 2-3 MK plasma

component.

6.3 MK) corresponding to a

nonflaring active region. These observational results are supported

by the theoretical work of Klimchuk et al. (2008) who use

hydrodynamic simulations of nanoflares to predict a small amount of

hot plasma in addition to the dominant 2-3 MK plasma

component.

The RESIK spectra recorded during solar minimum can bridge the gap between the results obtained from ultraviolet and X-ray images and spectra and the models of coronal plasma heating. In earlier work, we analyzed RESIK spectra to determine the conditions of flaring plasmas, but here we apply the same techniques of analyzing emission during low-level periods to deduce the properties of the quiet-Sun corona.

2 RESIK spectra selection and isothermal analysis

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=7.6cm,clip]{12907fg1.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/06/aa12907-09/Timg12.png)

|

Figure 1: Histogram showing the respective GOES activity for selected 312 time intervals (January-February 2003). |

| Open with DEXTER | |

We selected 312 time intervals, each 5 min in duration, for

which

solar activity levels in the first quarter of 2003 were at their

lowest. The measurements were taken outside intervals of increased

background owing to passages of the CORONAS-F

spacecraft

through polar ovals or the South Atlantic Anomaly. Early in 2003,

the RESIK instrument characteristics (high voltage and amplitude

discrimination) were set at their optimum values. Each spectrum

analyzed was integrated over a 302 s interval, the longest

selectable period for a low-flux operating mode, so the overall

data accumulation time was 26.2 h. The spectra correspond to

GOES activity levels from ![]() A9 to

A9 to ![]() B5.

We found it

useful to group the observed spectra according to the activity level

at the time that they were recorded, so that the summed spectra for

any group has an improved statistical quality. The division into

groups was chosen according to activity level steps of 0.1 in

the

logarithm (0.1 dex).

B5.

We found it

useful to group the observed spectra according to the activity level

at the time that they were recorded, so that the summed spectra for

any group has an improved statistical quality. The division into

groups was chosen according to activity level steps of 0.1 in

the

logarithm (0.1 dex).

In Fig. 1

we show the distribution of spectra with GOES

classes. The lowest class includes spectra from the GOES

class between A9 and B1 (1-8 Å flux from ![]() to

to

![]() W m-2),

attained between 2003 February 23

and February 25. Although flaring periods were always

carefully

avoided in selecting spectra, it was impossible to avoid the

presence of active regions, as RESIK operated close to the maximum

of Cycle 23.

W m-2),

attained between 2003 February 23

and February 25. Although flaring periods were always

carefully

avoided in selecting spectra, it was impossible to avoid the

presence of active regions, as RESIK operated close to the maximum

of Cycle 23.

A typical pattern of activity during the time of the selected spectra collection is illustrated (Fig. 2) with a set of full-disk EUV images from the Extreme-ultraviolet Imaging Telescope (EIT; Delaboudiniere et al. 1995) aboard the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) on 2003 February 24 around 19:00 UT. The images are in the spectral bands 304 Å (He II), 171 Å (Fe IX-X), 195 Å (Fe XII), and 284 Å (Fe XV), which are sensitive to temperatures of about 80 000 K, 1.3 MK, 1.6 MK, and 2 MK, respectively. Weak active-region emission is visible in all passbands. This is also true for all other times when RESIK spectra were selected, so our results therefore apply to times when the corona was quiet and also when there were weak active regions. In Fig. 3, the average of all the 312 spectra is shown, with spectral lines or their expected wavelengths identified. The background is a true solar continuum. Identification of main contributing lines is provided in Table 1.

For these quiet-Sun spectra, there is practically no line

emission

in channel 1 (shown in blue), though for flare spectra, the

prominent triplet of lines due to K XVIII

(3.53-3.57 Å) is

always present (Sylwester et al. 2006b).

Similarly, the Ar

XVII (3.95-4.00 Å) triplet in

channel 2 (dark red) is barely

distinguished but the lines are very prominent during flares. Only

weak line emission is visible in channel 3 (orange),

identifiable

with dielectronic satellites to the parent 1s-3p (w3)

transition of the H-like S XVI

ion. However, channel 4

(yellow) is rich in strong lines formed by relatively cool plasma

(T < ![]() 5 MK).

5 MK).

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.2cm,clip]{12907fg2.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/06/aa12907-09/Timg15.png)

|

Figure 2: Composite of four full-disk EIT/SOHO images obtained in the wavelength bands 304 Å, 171 Å, 195 Å, and 284 Å, on 2003 February 24 around 19:00 UT. This was the time of lowest activity in the period of the RESIK quiet-Sun spectra analyzed in this work. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Table 1: Wavelength intervals used for DEM studies.

The He-like S XV line

triplet (5.05-5.10 Å) is prominent but

with only two components resolved owing to increased line widths. More

prominent line features correspond to Si XIII

transitions

1s2-1s4p and 1s2-1s3p (w4, w3)

at 5.40 and 5.68 Å,

with nearby Si XII dielectronic

satellites at 5.56 and 5.82 Å (d4, D).

The w4, d4 lines are

marked by red

arrows, the w3, D lines

by blue arrows. Ratios of the flux in an

Si XII dielectronic

satellite feature to that in the parent

Si XIII resonance line

is very sensitive to temperature in the

range 2-5 MK (Phillips et al. 2006). Here we

used the ratio D/w3 to

determine the cooler plasma component temperature characterizing

the general coronal emission that the selected RESIK spectra are

sensitive to. To do this, we fitted Gaussian profiles to the

lines

(continuum level subtracted) and the flux ratios compared with

theoretical values. The derived ``isothermal'' temperatures (TD/w3 raw)

are given in Table 2

for each activity class. The

temperatures range from 3.1 MK to ![]() 3.8 MK for the lowest and

highest activity classes. They are much lower than those

corresponding to flare temperatures (Phillips et al. 2006), even

those late in the decay phase. It is striking to see that the

intensity of the satellite line D is much

higher than the parent

line w3, even for a medium-Z

(Z=14) element like Si.

Generally, this has been seen in flare spectra only for Fe

XXIV satellites near Fe XXV lines

(near 1.9 Å: Z for

Fe = 26): note that the flux ratio scales as Z4.

3.8 MK for the lowest and

highest activity classes. They are much lower than those

corresponding to flare temperatures (Phillips et al. 2006), even

those late in the decay phase. It is striking to see that the

intensity of the satellite line D is much

higher than the parent

line w3, even for a medium-Z

(Z=14) element like Si.

Generally, this has been seen in flare spectra only for Fe

XXIV satellites near Fe XXV lines

(near 1.9 Å: Z for

Fe = 26): note that the flux ratio scales as Z4.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=16cm,clip]{12907fg3.eps} \vspace*{-2mm} \vspace*{-2mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/06/aa12907-09/Timg16.png)

|

Figure 3: The absolute RESIK spectrum averaged over 312 quiet Sun intervals selected between 2003 January and March. The most prominent lines are identified. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

A simple way of deducing the physical characteristics of an emitting

plasma is by the ratio of fluxes in broad-band filters. For RESIK,

the corresponding technique is to take the flux ratio of the total

amount of emission in channels 3 and 4. An isothermal

assumption is

often too crude to be useful (as will be shown later), and

physical

interpretation of derived values can be ambiguous (Sylwester 1990).

The results of the analysis are given in Table 2 (denoted

by ``3/4''

entries). The T3/4 values

clearly decrease with increasing

activity levels, against expectation, whereas the values of

TD/w3

increase. This can be understood in terms of the DEM

analysis presented later. The most commonly used diagnostics of

physical conditions in the coronal thermal plasma component rely on

interpreting the flux ratios measured in the two standard

GOES bands. This standard approach (available,

e.g., in the

GOES section of the IDL SolarSoft

package: Freeland &

Handy 1998)

was used here, and values of temperatures and emission

measures are given in Table 2 as averages over

corresponding

activity groups (denoted by subscript G). It should

be stressed,

however, that the GOES values derived for the

lower intensity

classes may be somewhat biased by problems intrinsic to measurements

of very low flux levels. The results shown in Table 2 indicate that

![]() decreases

with activity class, as with the values of T3/4.

With average values of T and EM,

we may estimate the

total thermal energy in the soft X-ray emitting component.

It has

been shown by Sylwester et al. (2008) that

this energy content can

be expressed as

decreases

with activity class, as with the values of T3/4.

With average values of T and EM,

we may estimate the

total thermal energy in the soft X-ray emitting component.

It has

been shown by Sylwester et al. (2008) that

this energy content can

be expressed as

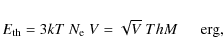

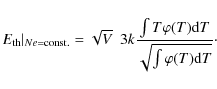

|

(1) |

where V is the emitting volume and ThM, a ``thermodynamic measure'', is defined by

|

(2) |

The use of ThM is convenient as its variation directly reflects the changes of thermal energy, provided the emitting volume does not change substantially. Derived values of ThM are given in Table 2. It is seen that, in spite of significant differences between the values of T3/4 and

Table 2: Derived plasma parameters for individual activity classes.

3 Differential emission measure determinations

It is generally known that the isothermal approach to determining the characteristics of emitting plasma has serious limitations (Sylwester 1990) and a more advanced approach relies on the concept of differential emission measure, DEM (Sylwester et al. 1980). We used the DEM approach to analyze of quiet-Sun RESIK spectra arranged by activity grouping. The algorithm we used follows the Bayesian approach, described in detail by Sylwester et al. (1980), and called the Withbroe-Sylwester algorithm. To apply this algorithm to the analysis of RESIK data, we selected 15 spectral intervals in all four RESIK channels. The wavelength ranges of channels 1 and 2 were divided into 2 broad ranges (between 0.15 Å and 0.25 Å wide) with the remaining 11 ranges in channels 3 and 4 placed around stronger lines or line groups. The ranges are given in Table 1, together with principal contributors to the emission. We performed tests by slightly varying the band widths to find which were the most suitable.

The spectral fluxes were then integrated over each band to improve the count statistics. These fluxes were then used as input to the DEM iterative algorithm. Theoretical spectra providing another source of input for the DEM inversions have been calculated from the CHIANTI v5.2 atomic code (SolarSoft) using the coronal, photospheric, and the other suitable plasma composition models.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=17cm,clip]{12907fg4.ps}

\vspace*{2mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/06/aa12907-09/Timg33.png)

|

Figure 4: The differential emission measure distribution calculated from the fluxes in 15 passbands of the averaged nonflaring RESIK spectrum. The results are shown for assuming photospheric ( left) coronal ( middle) and optimized for the observed spectrum ( right) quiet elemental abundances. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

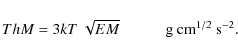

The goodness of the fit between the observed and DEM-fitted band

fluxes was determined by the standard normalized ![]() values,

values,

|

(3) |

which is easy to determine when the uncertainties (due to photon count rate statistics) are known. The absolute fluxes should have very small uncertainties because the RESIK intensity calibration is well known (Sylwester et al. 2005). The DEM iterative process was continued for 104 iterations or whenever continuous convergence was attained. In Eq. (3), Fi is the photon flux measured in band i, Fic is the flux calculated based on given DEM model, n the number of spectral bands used (n=15), and

It is not obvious which of the two generally used composition

models

(coronal or photospheric abundances) should be used in the analysis

of the quiet corona spectra, so we did the DEM inversions for

both

sets of plasma abundances. The resulting best-fit DEM shapes for the

averaged spectrum (integration time 26.2 h) are shown in the

left and middle panels of Fig. 4. The envelope of

uncertainties of

the DEM shape, from 100 Monte-Carlo runs, is shown by

the lengths of

the error bars. It can be seen how sensitive the resulting

shape of

the average DEM is to the assumed model of the plasma composition.

The best-fit ![]() values

are beyond an acceptable range for both

photospheric or coronal composition models. We thus concluded that

to provide reliable estimates of the DEM shape we should also

finely adjust the plasma composition in order to optimize the fit

between the observed and calculated spectral band fluxes. To do

this, we generated a large spectral look-up, many-dimensional

spectral database containing the synthesized profiles in the

spectral ranges covered by RESIK (each 0.001 Å),

in 101

temperature points (equidistant between

values

are beyond an acceptable range for both

photospheric or coronal composition models. We thus concluded that

to provide reliable estimates of the DEM shape we should also

finely adjust the plasma composition in order to optimize the fit

between the observed and calculated spectral band fluxes. To do

this, we generated a large spectral look-up, many-dimensional

spectral database containing the synthesized profiles in the

spectral ranges covered by RESIK (each 0.001 Å),

in 101

temperature points (equidistant between ![]() ), with

varying abundances of the elements Ar, S, and Si. The

abundances of

the other elements not directly influencing the spectral shape for

the considered T-range of calculations were kept

equal to their

coronal values. The range of particular element variability was

taken from 0.1 to 20 times the coronal abundance

value.

), with

varying abundances of the elements Ar, S, and Si. The

abundances of

the other elements not directly influencing the spectral shape for

the considered T-range of calculations were kept

equal to their

coronal values. The range of particular element variability was

taken from 0.1 to 20 times the coronal abundance

value.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{12907fg5.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/06/aa12907-09/Timg38.png)

|

Figure 5:

Ratios of |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=15cm,clip]{12907fg6.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/06/aa12907-09/Timg39.png)

|

Figure 6: The absolute RESIK spectra in linear scale grouped according to the GOES class. The most prominent lines are indicated. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

With such a large spectral look-up cube it has been relatively easy

to look for effects of the dependence of the DEM inversion on

particular-element composition. The results obtained are illustrated

in Fig. 5,

where we show the trend in the minimum value of ![]() as a

function of element absolute abundance for Ar, S, and Si.

A well-defined minimum is present in each of the plots. The

location of the minimum along the abundance axis is placed close to the

photospheric value for S and Si. For the element Ar, which has

a high value of first ionization potential (FIP), derived optimum

abundance is above the coronal value. It follows that neither

the

photospheric nor the coronal abundance models can be used to

describe the observed set of spectral intensities at the same time.

Therefore we performed the DEM inversion using the optimum abundance

values as determined from the position of the minima in Fig. 5. The

result is shown in Fig. 4

(right panel). It is seen that the

calculated shape of the DEM is smoother in comparison with the

photospheric or coronal cases and the error envelope decreases. The

calculated value of the normalized

as a

function of element absolute abundance for Ar, S, and Si.

A well-defined minimum is present in each of the plots. The

location of the minimum along the abundance axis is placed close to the

photospheric value for S and Si. For the element Ar, which has

a high value of first ionization potential (FIP), derived optimum

abundance is above the coronal value. It follows that neither

the

photospheric nor the coronal abundance models can be used to

describe the observed set of spectral intensities at the same time.

Therefore we performed the DEM inversion using the optimum abundance

values as determined from the position of the minima in Fig. 5. The

result is shown in Fig. 4

(right panel). It is seen that the

calculated shape of the DEM is smoother in comparison with the

photospheric or coronal cases and the error envelope decreases. The

calculated value of the normalized ![]() is also brought now into

an acceptable range. As a consequence of this exercise, we

decided

to perform the composition optimization process for every DEM

inversion for corresponding activity class. The results are shown in

Table 2

and illustrated in Fig. 7.

is also brought now into

an acceptable range. As a consequence of this exercise, we

decided

to perform the composition optimization process for every DEM

inversion for corresponding activity class. The results are shown in

Table 2

and illustrated in Fig. 7.

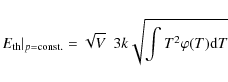

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{12907fg7.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/06/aa12907-09/Timg40.png)

|

Figure 7: The histogram representation of differential emission measure (DEM) distributions as obtained from RESIK spectra for individual classes of solar activity. Different colors correspond to the following classes: black (dark) represents the B4-B5 class and yellow (lightest) A9-B1 class. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

The calculated, abundance-optimized shapes of DEM distribution are

presented in different colors. The black histogram represents the

highest activity class (B4-B5). No error bars are

shown in order to

increase the visibility. It is observed that all DEM

distributions

are bimodal with the cooler (lower temperature) and hotter (higher

temperature) components well separated. As the activity level

increases, the average temperatures of the low and high-T

components

shift toward lower temperatures. This is somewhat unexpected but can

be understood as partly due to the deconvolution process working

more effectively when the emission measure ratio of the lower and

higher-T components is decreasing. The amount of

cooler plasma found

is orders of magnitude higher than the hotter one. Depending on the

activity level, this amounts to 750 and 1190 for the

lower and

higher activity levels, respectively. In Table 2 the basic

characteristics of the cooler (index L) and hotter

(index H) plasma

components is presented. In calculating the total thermal energy

content from the obtained DEM =

![]() distributions, we used

the following formulas, derived assuming a constant pressure or

density in the emission volume:

distributions, we used

the following formulas, derived assuming a constant pressure or

density in the emission volume:

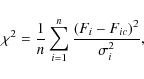

|

(4) |

|

(5) |

It is straightforward to assign the meaning of thermodynamic measure ThM to the righthand factors of Eqs. (4) and (5). It was found that the difference between results obtained in the constant pressure or constant density assumptions did not differ by more than a few percent for the considered DEM shapes, so in Table 2 we insert average values, characteristic of the cooler and hotter components. With the knowledge of respective volumes occupied by the cooler and the hotter plasma, it would be possible to estimate thermal energy content of respective components. This study is in progress.

The results of DEM calculations with the element-abundance

optimization for the five activity classes are shown in Fig. 7 in

different colors. The bimodal character of resulting DEM is evident.

The average values of the parameters characterizing each of the two

plasma components are given in Table 2 along with the

associated set

of optimum elemental abundances is provided. The data set in

Table 2

shows that the abundances of Ar and Si do not depend on the activity

level, but the sulfur abundance of the plasma contributing to RESIK

channel 4 spectra systematically increases by a factor of ![]() 4from a

level well below the photospheric to the coronal abundance

with activity increasing from lower to higher classes. The reason

for this behavior is not known at present. It is important to note

that the optimum abundances of Si are below the generally assumed

photospheric level, but the Ar abundances (Ar is a high-FIP

element)

lie even above coronal values. As concerns the energy content

associated with the two plasma components, it is interesting

to note

that the thermodynamic measure ratios of the lower and higher-Tcomponents

are much less than the ratio of respective emission

measures. Provided that the emitting volumes are comparable, this

would mean that the ratio of the total thermal energy content of the

hotter and cooler components is not all that different, and as a

consequence, the heating processes responsible for formation

of the

hotter component should not be disregarded in studies of the overall

energy balance even for nonflaring coronal conditions.

4from a

level well below the photospheric to the coronal abundance

with activity increasing from lower to higher classes. The reason

for this behavior is not known at present. It is important to note

that the optimum abundances of Si are below the generally assumed

photospheric level, but the Ar abundances (Ar is a high-FIP

element)

lie even above coronal values. As concerns the energy content

associated with the two plasma components, it is interesting

to note

that the thermodynamic measure ratios of the lower and higher-Tcomponents

are much less than the ratio of respective emission

measures. Provided that the emitting volumes are comparable, this

would mean that the ratio of the total thermal energy content of the

hotter and cooler components is not all that different, and as a

consequence, the heating processes responsible for formation

of the

hotter component should not be disregarded in studies of the overall

energy balance even for nonflaring coronal conditions.

4 Concluding remarks

We analyzed 312 individual RESIK spectra grouped into 5 different activity classes based on GOES levels of activity recorded at the time of the spectra collection. All selected spectra were taken during the nonflaring, low activity conditions prevailing in the corona, though some weak active-region emission was always present. The spectral observations (all with a five-minute integration time) cover the period between 2003 January 1 and March 14. The analysis assumed both isothermal and multithermal distributions, the latter leading to determination of DEM distributions for each activity class. The DEMs were obtained with the Withbroe-Sylwester Bayesian iterative, maximum likelihood procedure. The fluxes integrated over 15 wavelength bands covering the range 3.3-6.1 Å were used as an input data for the deconvolution. We found it necessary to allow for the emitting plasma composition to be nonstandard, i.e. neither coronal nor photospheric, by varying the abundances of those elements making important contributions to the line emission in the spectra. This analysis has never been done before except for a few flares (to be published, Montreal COSPAR). The main results of the present study follow.

- 1.

- It is necessary to use the multithermal approach in analyzing the spectra. The results obtained in the isothermal approximation provide different values of T and EM parameters depending on the ratio considered. However, the values of so-called thermodynamic measure that is directly related to the total thermal energy plasma content are very close, because they are surprisingly independent of the particular ratio used for its determination.

- 2.

- It appears necessary to allow for the plasma composition differences when using the multitemperature approach in the analysis. Neither coronal nor photospheric composition models are able to describe the observed spectra satisfactorily. This result may also bias the outcome of any isothermal analysis performed with an isothermal approach.

- 3.

- The two-temperature character of the DEM shape determined

here for non-flaring plasmas has also been obtained for flares

(Sylwester et al. 2008).

The presence of the higher-T component,

with T somewhat below 10 MK, is

physically important. The emission measure associated with this hotter

plasma is

3 orders

of magnitude smaller than in the generally accepted

3 orders

of magnitude smaller than in the generally accepted  MK

component. This higher-T component is required

because it is impossible to reproduce the observed spectra

without it.

MK

component. This higher-T component is required

because it is impossible to reproduce the observed spectra

without it.

RESIK is a common project between the NRL (USA), MSSL and RAL (UK), IZMIRAN (Russia), and SRC (Poland). This work was partially supported by the International Space Science Institute in the framework of an international working team (No. 108). We acknowledge the travel support from a UK Royal Society/Polish Academy of Sciences International Joint Project. CHIANTI is a collaborative project involving the NRL (USA), RAL (UK), MSSL (UK), the Universities of Florence (Italy) and Cambridge (UK), and George Mason University (USA). The research leading to these results received partial funding from the European Commission's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under grant agreement No. 218816 (SOTERIA project, www.soteria-space.eu).

References

- Brosius, J. W., Davila, J. M., & Thomas, R. J. 1996, ApJS, 106, 143 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Brosius, J. W., Davila, J. M., & Thomas, R. J. 1998, ApJS, 119, 255 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chifor, C., del Zanna, G., Mason, H. E., et al. 2007, A&A, 462, 323 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Curdt, W., Landi, E., & Feldman, U. 2004, A&A, 427, 1045 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Delaboundiniere, J.-P., Artzner, G. E., Brunaud, J., et al. 1995, Sol. Phys., 162, 291 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Dupree, A. K., & Reeves, E. M. 1971, ApJ, 165, 599 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Dupree, A. K., Huber, M. C. E., Noyes, R. W., et al. 1973, ApJ, 182, 321 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Freeland, S. L., & Hardy, B. N. 1998, Sol. Phys., 182, 497 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hannah, I. G., Hurford, G. J., Hudson, H. S., Lin, R. P., & van Bibber, K. 2007, ApJ, 659, L77 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Klimchuk, J. A., Patsourakos, S., & Cargill, P. J. 2008, ApJ, 682, 1351 [Google Scholar]

- Kretzschmar, M., Lilensten, J., & Aboudarham, J. 2004, A&A, 419, 345 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Malinovsky, M., & Heroux, L. 1973, ApJ, 181, 1009 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, L. E., Schwartz, D. A., Pelling, R. M., & Mckenzie, D. 1966, J. Geophys. Res., 71, 5778 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, K. J. H., Dubau, J., Sylwester, J., & Sylwester, B. 2006, ApJ, 638, 1154 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ralchenko, Yu., Feldman, U., & Doschek, G. A. 2007, ApJ, 659, 1682 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Reale, F., Testa, P., Klimchuk, J. A., & Parenti, S. 2009, ApJ, 698, 756 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- O'Shea, E., Gallagher, P. T., Mathioudakis, M., et al. 2000, A&A, 358, 741 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Schmelz, J. T., Saar, S. H., DeLuca, E. E., et al. 2009, ApJ, 693, L131 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sylwester, B., Sylwester, J., Siarkowski, M., et al. 2006a, Adv. Space Res., 38, 1534 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sylwester, B., Sylwester, J., Kepa, A., et al. 2006b, Sol. System Res., 40, 125 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sylwester, B., Sylwester, J., & Phillips, K. J. H. 2008, J. Astrophys. Astr., 29, 147 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sylwester, J. 1990, The Dynamic Sun, Proceedings of the 6th European Meeting on Solar Physics, Debrecen, 21-24 May, ed. L. Dezso, Debrecen Heliophysical Observatory of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, 7, 212 [Google Scholar]

- Sylwester, J., Schrijver, J., & Mewe, R. 1980, Sol. Phys., 67, 285 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sylwester, J., Gaicki, I., Kordylewski, Z., et al. 2005, Sol. Phys., 226, 45 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sylwester, J., Sylwester, B., & Phillips, K. J. H. 2008, ApJ, 681, L117 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Warren, H. P., Mariska, J. T., & Lean, J. 1998, J. Geoph. Res., 103, 12077 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Vernazza, J. E., & Reeves, E. M. 1978, ApJS, 37, 485 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Young, P. R., Del Zanna, G., Mason, H. E., et al. 2007, PASJ, 59, S857 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

All Tables

Table 1: Wavelength intervals used for DEM studies.

Table 2: Derived plasma parameters for individual activity classes.

All Figures

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=7.6cm,clip]{12907fg1.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/06/aa12907-09/Timg12.png)

|

Figure 1: Histogram showing the respective GOES activity for selected 312 time intervals (January-February 2003). |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.2cm,clip]{12907fg2.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/06/aa12907-09/Timg15.png)

|

Figure 2: Composite of four full-disk EIT/SOHO images obtained in the wavelength bands 304 Å, 171 Å, 195 Å, and 284 Å, on 2003 February 24 around 19:00 UT. This was the time of lowest activity in the period of the RESIK quiet-Sun spectra analyzed in this work. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=16cm,clip]{12907fg3.eps} \vspace*{-2mm} \vspace*{-2mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/06/aa12907-09/Timg16.png)

|

Figure 3: The absolute RESIK spectrum averaged over 312 quiet Sun intervals selected between 2003 January and March. The most prominent lines are identified. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=17cm,clip]{12907fg4.ps}

\vspace*{2mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/06/aa12907-09/Timg33.png)

|

Figure 4: The differential emission measure distribution calculated from the fluxes in 15 passbands of the averaged nonflaring RESIK spectrum. The results are shown for assuming photospheric ( left) coronal ( middle) and optimized for the observed spectrum ( right) quiet elemental abundances. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{12907fg5.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/06/aa12907-09/Timg38.png)

|

Figure 5:

Ratios of |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=15cm,clip]{12907fg6.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/06/aa12907-09/Timg39.png)

|

Figure 6: The absolute RESIK spectra in linear scale grouped according to the GOES class. The most prominent lines are indicated. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{12907fg7.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/06/aa12907-09/Timg40.png)

|

Figure 7: The histogram representation of differential emission measure (DEM) distributions as obtained from RESIK spectra for individual classes of solar activity. Different colors correspond to the following classes: black (dark) represents the B4-B5 class and yellow (lightest) A9-B1 class. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

Copyright ESO 2010

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.