| Issue |

A&A

Volume 513, April 2010

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A34 | |

| Number of page(s) | 15 | |

| Section | Galactic structure, stellar clusters, and populations | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/200913759 | |

| Published online | 21 April 2010 | |

The NIR Ca II triplet at low metallicity

Searching for extremely low-metallicity stars in classical dwarf galaxies![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

E. Starkenburg1

- V. Hill2

- E. Tolstoy1 - J. I. González Hernández3,4,![]() - M. Irwin5

- A. Helmi1

- G. Battaglia6

- P. Jablonka7

- M. Tafelmeyer7

- M. Shetrone8

- K. Venn9 - T. de Boer1

- M. Irwin5

- A. Helmi1

- G. Battaglia6

- P. Jablonka7

- M. Tafelmeyer7

- M. Shetrone8

- K. Venn9 - T. de Boer1

1 - Kapteyn Astronomical Institute, University of Groningen, PO Box 800, 9700 AV Groningen, The Netherlands

2 - Laboratoire Cassiopée UMR 6202, Université de Nice Sophia-Antipolis, CNRS, Observatoire de la Côte d'Azur, France

3 - GEPI, Observatoire de Paris, CNRS, Université Paris Diderot, Place Jules Janssen, 92190 Meudon, France

4 - Dpto. de Astrofísica y Ciencias de la Atmósfera, Facultad de

Ciencias Físicas, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, 28040 Madrid,

Spain

5 - Institute of Astronomy, University of Cambridge, Madingley Road, Cambridge CB03 0HA, UK

6 - European Organization for Astronomical Research in the Southern

Hemisphere, Karl-Schwarzschild-Strasse 2, 85748 Garching, Germany

7 - Observatoire de Genève, Laboratoire d'Astrophysique de l'École

Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), 1290 Sauverny, Switzerland

8 - University of Texas, McDonald Observatory, HC75 Box 1337-McD, Fort Davis, TX 79734, USA

9 - Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Victoria, 3800 Finnerty Road, Victoria, BC, V8P 1A1, Canada

Received 27 November 2009 / Accepted 15 January 2010

Abstract

The NIR Ca II triplet absorption lines have proven

to be an important tool for quantitative spectroscopy of individual red

giant branch stars in the Local Group, providing a better understanding

of metallicities of stars in the Milky Way and dwarf galaxies and

thereby an opportunity to constrain their chemical evolution processes.

An interesting puzzle in this field is the significant lack of

extremely metal-poor stars, below [Fe/H] = -3, found in

classical dwarf galaxies around the Milky Way using this

technique. The question arises whether these stars are really absent,

or if the empirical Ca II triplet method used

to study these systems is biased in the low-metallicity regime. Here we

present results of synthetic spectral analysis of the Ca II triplet,

that is focused on a better understanding of spectroscopic

measurements of low-metallicity giant stars. Our results start to

deviate strongly from the widely-used and linear empirical calibrations

at [Fe/H] < -2. We provide a new calibration for Ca II triplet studies which is valid for -0.5 ![]() [Fe/H]

[Fe/H] ![]() -4.

We subsequently apply this new calibration to current data sets and

suggest that the classical dwarf galaxies are not so devoid of

extremely low-metallicity stars as was previously thought.

-4.

We subsequently apply this new calibration to current data sets and

suggest that the classical dwarf galaxies are not so devoid of

extremely low-metallicity stars as was previously thought.

Key words: stars: abundances - galaxies: dwarf - galaxies: evolution - Local Group - Galaxy: formation

1 Introduction and outline

To understand galaxy evolution it is critical to understand how the

metallicities of stars in physically different environments develop

with time. Low- and high-resolution spectroscopic studies of individual

stars in the Milky Way and dwarf galaxies are crucial in this

context since they can provide measurements of overall metallicity and

detailed abundances of a range of elements (e.g., Freeman & Bland-Hawthorn 2002,

and references therein). Studies of this kind have revealed interesting

differences between the stars in the Milky Way halo and the dwarf

spheroidal galaxies (dSphs) surrounding it (Tolstoy et al. 2009,

and references therein). An intriguing population of stars to

study in different environments are the extremely metal-poor stars

([Fe/H] ![]() -3).

The existence, or lack of, these stars reveals valuable

information about the chemical evolution history of a galaxy,

as they represent the most pristine (and probably thus the

oldest) stars in the system. For example, in a scenario

where there are no low-metallicity stars, theories invoking some kind

of pre-enrichment prior to the star formation epoch become more

plausible. In general, detailed chemical abundances of old stars

can provide valuable information about chemical evolution processes as

they are likely to be polluted by only a single or very few supernova.

A comparison of low-metallicity tails in different galaxies also

provides information about the origin and evolution of systems with

different masses and different star formation histories.

-3).

The existence, or lack of, these stars reveals valuable

information about the chemical evolution history of a galaxy,

as they represent the most pristine (and probably thus the

oldest) stars in the system. For example, in a scenario

where there are no low-metallicity stars, theories invoking some kind

of pre-enrichment prior to the star formation epoch become more

plausible. In general, detailed chemical abundances of old stars

can provide valuable information about chemical evolution processes as

they are likely to be polluted by only a single or very few supernova.

A comparison of low-metallicity tails in different galaxies also

provides information about the origin and evolution of systems with

different masses and different star formation histories.

From relatively time-consuming but insightful high-resolution (HR) studies of small samples of bright red giant branch (RGB) stars in nearby dSphs we know that the chemical signatures of individual elements in the dSph stars can be distinct from the stars in the Galaxy (e.g., Shetrone et al. 2001; Cohen & Huang 2009; Frebel et al. 2010; Shetrone et al. 2003; Tolstoy et al. 2003; Fulbright et al. 2004; Koch et al. 2008a; Aoki et al. 2009; Koch et al. 2008b; Venn et al. 2004). So far all high-resolution observations of extremely metal-poor stars in dSphs have been studied in high-resolution as part of follow-up studies on previous low-resolution samples (Cohen & Huang 2009; Frebel et al. 2010; Aoki et al. 2009; Frebel et al. 2010; Tafelmeyer et al., in prep.). These stars are still sparse and at the moment mostly found in the ultra-faint dwarf galaxies. The high-resolution studies of classical dSphs which are not follow-up studies, have first targeted the inner galactic regions, which are often more metal-rich, and are hence not optimized to specifically target metal-poor stars.

Additionally, recent low-resolution (LR) studies enable us to

determine overall metallicity estimates for much larger samples of

RGB stars in both classical dSphs (e.g., Koch et al. 2007b; Battaglia et al. 2008a; Pont et al. 2004; Tolstoy et al. 2004; Shetrone et al. 2009; Koch et al. 2007a; Kirby et al. 2009; Suntzeff et al. 1993; Muñoz et al. 2006; Battaglia et al. 2006; Walker et al. 2009a), ultra-faint galaxies (e.g., Walker et al. 2009b; Norris et al. 2008; Simon & Geha 2007; Koch et al. 2009; Kirby et al. 2008) and even the more distant and isolated dwarf irregular galaxies (e.g., Leaman et al. 2009).

From the larger numbers of stars studied in the low-resolution studies

for the classical dSphs (typically several hundred per galaxy) one

would statistically expect to find some RGB stars with [Fe/H] ![]() -3, if the distribution of metallicities in these systems follows that of the Galactic halo (Helmi et al. 2006).

However, one of the compelling results from studies of large samples of

RGB stars is a significant lack of stars with metallicities

[Fe/H]

-3, if the distribution of metallicities in these systems follows that of the Galactic halo (Helmi et al. 2006).

However, one of the compelling results from studies of large samples of

RGB stars is a significant lack of stars with metallicities

[Fe/H] ![]() -3

in the classical dSph galaxies Sculptor, Fornax, Carina and

Sextans compared to the metallicity distribution function of the

Galactic halo (Helmi et al. 2006). These metallicities are inferred from the line strengths of the Ca II NIR triplet (CaT) lines. Recently, Kirby et al. (2009)

reported to have found a RGB star in Sculptor with

a [Fe/H] value as low as -3.8 using a comparison between

spectra and an extensive spectral library. Several extremely

low-metallicity stars have already been discovered in the ultra-faint

dwarf galaxies using either this technique or other indicators (Norris et al. 2008; Kirby et al. 2008).

In this paper we investigate whether the lack of low-metallicity

stars in the classical dwarf galaxies could be a bias due to the Ca II NIR triplet (CaT) indicator used to determine metallicities from low-resolution spectra.

-3

in the classical dSph galaxies Sculptor, Fornax, Carina and

Sextans compared to the metallicity distribution function of the

Galactic halo (Helmi et al. 2006). These metallicities are inferred from the line strengths of the Ca II NIR triplet (CaT) lines. Recently, Kirby et al. (2009)

reported to have found a RGB star in Sculptor with

a [Fe/H] value as low as -3.8 using a comparison between

spectra and an extensive spectral library. Several extremely

low-metallicity stars have already been discovered in the ultra-faint

dwarf galaxies using either this technique or other indicators (Norris et al. 2008; Kirby et al. 2008).

In this paper we investigate whether the lack of low-metallicity

stars in the classical dwarf galaxies could be a bias due to the Ca II NIR triplet (CaT) indicator used to determine metallicities from low-resolution spectra.

The CaT lines have been used in studies over a wide range of

atmospheric parameters and have been applied to both individual stars

and integrated stellar populations in different environments (see Cenarro et al. 2001,2002,

and references therein). In this paper we focus on the use of the

CaT lines to determine metallicities of individual RGB stars.

The CaT region of the spectrum has proven to be a powerful

tool for metallicity estimates of individual stars. The three

CaT absorption lines (![]() 8498,

8498, ![]() 8542, and

8542, and ![]() 8662

8662 ![]() ),

which can be used to determine radial velocities and to trace

metallicity (usually taken as [Fe/H]), are so broad that they

can be measured with sufficient accuracy at a moderate resolution.

As was already noted in pioneering work (e.g., Armandroff & Da Costa 1991; Olszewski et al. 1991; Armandroff & Zinn 1988),

there are numerous additional advantages to the use of the

CaT lines as metallicity indicator. For instance,

the calcium abundances are expected to be largely representative

of the primordial abundances of the star, since, contrary to many other

elements, they are thought to be unaltered by nucleosynthesis processes

in intermediate- and low-mass stars on the RGB (Ivans et al. 2001; Cole et al. 2004).

Also, the NIR wavelength region is convenient: in that

the red giants emit more flux in this part of the spectrum than in the

blue and the spectrum is very flat, which facilitates the definition of

the continuum level to measure the equivalent widths of the line.

),

which can be used to determine radial velocities and to trace

metallicity (usually taken as [Fe/H]), are so broad that they

can be measured with sufficient accuracy at a moderate resolution.

As was already noted in pioneering work (e.g., Armandroff & Da Costa 1991; Olszewski et al. 1991; Armandroff & Zinn 1988),

there are numerous additional advantages to the use of the

CaT lines as metallicity indicator. For instance,

the calcium abundances are expected to be largely representative

of the primordial abundances of the star, since, contrary to many other

elements, they are thought to be unaltered by nucleosynthesis processes

in intermediate- and low-mass stars on the RGB (Ivans et al. 2001; Cole et al. 2004).

Also, the NIR wavelength region is convenient: in that

the red giants emit more flux in this part of the spectrum than in the

blue and the spectrum is very flat, which facilitates the definition of

the continuum level to measure the equivalent widths of the line.

However, the breadth of the lines also has disadvantages. Because the lines are highly saturated their strength, especially in the core of the line, depends strongly on the temperature structure of the upper layers of the photosphere and chromosphere of the star, which means that complicated non-local thermodynamic equilibrium (non-LTE) physics has to be used to model the line correctly (Cole et al. 2004). Also, the lines do not provide a direct measurement of [Fe/H], although it has been shown that [Fe/H] affects the equivalent width of the lines more than Ca (Battaglia et al. 2008b). The abundance of Ca and other elements do still affect the equivalent widths which will not always trace only [Fe/H] (Rutledge et al. 1997b).

Early investigations of the CaT concentrated mainly on their sensitivity to surface gravity (Jones et al. 1984; Spinrad & Taylor 1971; Cohen 1978; Spinrad & Taylor 1969). It was realized by Armandroff & Zinn (1988)

that a more metal-rich RGB star should have stronger

CaT lines, because it has both a greater abundance of Fe (and also

Ca) in its atmosphere and a lower surface gravity. They empirically

proved this relation by measuring for the CaT lines their

integrated equivalent width (EW) in several globular clusters with known [Fe/H]. Applying this method to individual RGB stars, Olszewski et al. (1991)

noticed that the metallicity sensitivity of the CaT line index is

improved by plotting it as a function of the absolute magnitude of

the star. At a fixed absolute magnitude, higher

metallicity RGB stars will have lower gravity and lower

temperatures, which both strengthen the CaT lines. A further

development of the method (Armandroff & Da Costa 1991) was to plot the equivalent width as a function of the height of the RGB stars above the horizontal branch (HB) in V-magnitude (

![]() ).

In this way, the requirements of a distance scale and a

well-determined reddening are avoided. They found a linear relation

between [Fe/H] and a ``reduced equivalent width'' (W'), which incorporates both the equivalent width of the two strongest lines at

).

In this way, the requirements of a distance scale and a

well-determined reddening are avoided. They found a linear relation

between [Fe/H] and a ``reduced equivalent width'' (W'), which incorporates both the equivalent width of the two strongest lines at

![]() and

and

![]() (also written as EW2 and EW3 in the remaining of this paper) and

(also written as EW2 and EW3 in the remaining of this paper) and

![]() .

This enables a direct comparison between RGB stars of different

luminosities. This method has been extensively tested and proven to

work on large samples of individual RGB stars in globular clusters

(e.g., Rutledge et al. 1997b,a).

.

This enables a direct comparison between RGB stars of different

luminosities. This method has been extensively tested and proven to

work on large samples of individual RGB stars in globular clusters

(e.g., Rutledge et al. 1997b,a).

Additionally, Cole et al. (2004) showed that the effect of different ages of RGB stars is a negligible source of error for metallicities derived from the CaT index. This paved the way for the use of the CaT metallicity indicator on populations of RGB stars which are not coeval, among which are the Local Group dwarf galaxies. A direct detailed comparison between the low-resolution CaT metallicities and high-resolution measurements for large samples of RGB stars in the nearby dwarf galaxies Fornax and Sculptor is given by Battaglia et al. (2008b). They concluded that the CaT - [Fe/H] relation (calibrated on globular clusters) can be applied with confidence to RGB stars in composite stellar populations over the range -2.5 < [Fe/H] < -0.5.

In this paper we study the behavior of the CaT for

[Fe/H] < -2.5, comparing stellar atmosphere models with

observations. We have determined a new calibration including this

low-metallicity regime. The paper is organized as follows.

In Sect. 2

we further clarify and physically motivate the need for a new

calibration at lower metallicities using simple synthetic spectra

modeling. In Sect. 3 we

describe our grid of synthetic spectra we use to investigate the

CaT lines. We then analyze and calibrate this grid in two regimes:

-2.0 ![]() [Fe/H]

[Fe/H] ![]() -0.5 in Sect. 4, and [Fe/H]

-0.5 in Sect. 4, and [Fe/H] ![]() -2.5 in Sect. 5. In Sect. 6 we present a new calibration valid for both metallicity regimes. Additionally, we investigate the role of

-2.5 in Sect. 5. In Sect. 6 we present a new calibration valid for both metallicity regimes. Additionally, we investigate the role of ![]() elements in Sect. 7 and the implications of the new calibration on the results of the Dwarf Abundances and Radial velocities Team (DART) survey (Tolstoy et al. 2006) in Sect. 8.

elements in Sect. 7 and the implications of the new calibration on the results of the Dwarf Abundances and Radial velocities Team (DART) survey (Tolstoy et al. 2006) in Sect. 8.

2 The CaT at low metallicity

The so-called CaT empirical relation connects a linear combination of

the equivalent widths of the CaT lines (the exact form can

vary between different authors) and the absolute luminosity of the

star, often expressed in terms of the height of the star above the HB

of the system, to its [Fe/H] value. The empirical relation

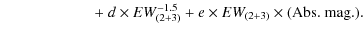

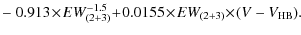

described in Battaglia et al. (2008b) in their Eqs. (16) and (11) are given as Eqs. (1) and (2) below.

where:

At present this linear relation between metallicity and CaT equivalent widths is also used to infer metallicities for stars outside the calibrated regime (-2.5 < [Fe/H] < -0.5). However, the assumption that the relation continues outside of this regime has not been accurately checked. It is very clear that the linear relation cannot hold down to extremely low metallicities, since at a certain point Eqs. (1) and (2) infer that the equivalent widths will have negative values. Negative equivalent widths for absorption lines is obviously physically meaningless.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{13759fg1.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13759-09/Timg18.png)

|

Figure 1:

The change of the shape of the CaT line at |

It is also expected that the shape of the lines, and therefore the relation of equivalent width with metallicity, changes as the metallicity drops. The equivalent width of the CaT lines is dominated at higher metallicities by the wings of the line. At lower metallicities these wings weaken and/or even disappear and the equivalent width of the line becomes more dominated by its core, as illustrated in Fig. 1 from synthetic spectra. Since the core and the wings of the lines originate from different parts of the curve of growth the behavior of both is unlikely to be described by one linear equation. The change in relative strength of the core and wings of the line changes the sensitivity of the line to the Ca abundance and to the overall metallicity in general. This understanding of the physical process motivates our re-calibration of the relation between CaT equivalent width and [Fe/H] at lower metallicities.

3 A grid of models

In order to investigate and quantify the behavior of the

CaT lines at low metallicity we define a grid of model spectra

created using the publicly available and recently revised version of

the (OS)MARCS models (e.g., Plez 2008; Gustafsson et al. 2008) and the Turbospectrum program (Alvarez & Plez 1998) updated consistently with the latest release of MARCS Gustafsson et al. (2008). The model spectra cover a range of effective temperatures, gravities, metallicities ([Fe/H]) and enhancements of the ![]() elements (taken as O, Ne, Mg, Si, S, Ar, Ca, and Ti in the MARCS models (Gustafsson et al. 2008)).

The models use a 1D spherical symmetric approach. Our

linelist is created using the Vienna Atomic Line Database (VALD) for

the atomic species (e.g., Kupka et al. 2000). Additionally we also model the contribution from CN molecular lines (Spite et al. 2005; Plez priv comm.)

and TiO moleculer lines in the cooler (

elements (taken as O, Ne, Mg, Si, S, Ar, Ca, and Ti in the MARCS models (Gustafsson et al. 2008)).

The models use a 1D spherical symmetric approach. Our

linelist is created using the Vienna Atomic Line Database (VALD) for

the atomic species (e.g., Kupka et al. 2000). Additionally we also model the contribution from CN molecular lines (Spite et al. 2005; Plez priv comm.)

and TiO moleculer lines in the cooler (

![]() models (Plez 1998).

models (Plez 1998).

Table 1: The parameters for the grid of models used.

3.1 Parameters

The parameters [Fe/H], [3.2 Non-LTE effects

Although all model atmospheres and synthetic spectra are calculated assuming local thermodynamic equilibrium (LTE), we take effects of departures from LTE into account, because they can be significant since the lines are so highly saturated. The effect of departures from LTE on these lines was first investigated by Jorgensen et al. (1992), but only for [Fe/H]Because the broad wings of the CaT lines are decreasing significantly with metallicity, as shown in Fig. 1,

the effect of departures from LTE, which only affect the core,

have most impact on the equivalent width determination at low

metallicities. Therefore, it is crucial to take

non-LTE effects into account in order to understand the behavior

of the CaT lines at low metallicity. We perform

non-LTE calculations using the model atom presented by Mashonkina et al. (2007), which contains 63 levels of Ca I, 37 levels of Ca II and the ground state of Ca III. Non-LTE level populations and synthetic spectra were determined with recent versions of the codes DETAIL and SURFACE (Butler & Giddings 1985; Giddings 1981). We chose ATLAS9 atmospheric models (Kurucz 1993)

as the input models in the non-LTE computations. Thus, we computed

ATLAS9 model atmospheres exactly for a given set of stellar

parameters and metallicities using a Linux version of the

ATLAS9 code (Sbordone et al. 2004), and adopting the new Opacity Distribution Functions (ODFs) of Castelli & Kurucz (2003). We also adopted

![]() as the scaling factor of the inelastic collisions with hydrogen atoms

in the non-LTE computations. For further details on the

non-LTE computations we refer to Mashonkina et al. (2007).

as the scaling factor of the inelastic collisions with hydrogen atoms

in the non-LTE computations. For further details on the

non-LTE computations we refer to Mashonkina et al. (2007).

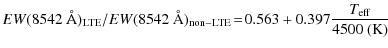

We determined the equivalent widths by integrating normalized fluxes of the broad Ca II triplet non-LTE profiles at 8542 and 8662 Å. Figure 2 shows the ratio of LTE EWs to non-LTE EWs

from this modeling for both these CaT lines in separate panels.

At high temperature and [Fe/H] = -4.0 the ratio goes

down in both lines to ![]() 0.7, which means that just

0.7, which means that just ![]() 70%

of the line is modeled in LTE and non-LTE effects are thus very

important. We determine a best-fitting relation as a function of

metallicity and temperature of the model using the IDL function

MPFIT2DFUN (Markwardt 2009), which performs a

Levenberg-Marquardt least-squares fit to a 2D function,

in combination with a statistical F-test to identify the best fit.

The best-fitting relations obtained separately for the two

strongest CaT lines are shown as dashed gray lines in Fig. 2 and given in Eqs. (3) and (4).

70%

of the line is modeled in LTE and non-LTE effects are thus very

important. We determine a best-fitting relation as a function of

metallicity and temperature of the model using the IDL function

MPFIT2DFUN (Markwardt 2009), which performs a

Levenberg-Marquardt least-squares fit to a 2D function,

in combination with a statistical F-test to identify the best fit.

The best-fitting relations obtained separately for the two

strongest CaT lines are shown as dashed gray lines in Fig. 2 and given in Eqs. (3) and (4).

For our finer grid of synthetic spectra from MARCS model atmospheres described in the previous paragraph we use these equations to determine the ratio of LTE to non-LTE equivalent widths for the two lines in each individual model. By dividing the individual equivalent widths in the grid (which are all calculated in LTE) by the factor for the corresponding line before adding the two strongest lines together, we correct each of the grid points for non-LTE effects.

4 The CaT lines at -2.0  [Fe/H]

[Fe/H]  -0.5

-0.5

4.1 The empirical relation

The empirical relation between CaT EW, absolute magnitude

and [Fe/H] is very well studied in globular clusters,

i.e., in the metallicity range between [Fe/H] ![]() -2.3 and [Fe/H]

-2.3 and [Fe/H] ![]() -0.5.

This well-known relation can thus be used to test our synthetic spectra

at these metallicities. We make a comparison between the CaT lines

from atmospheric models between

-0.5 < [Fe/H] < -2.0 and the best fit linear

relation for globular clusters as given in Eqs. (1) and (2) in Sect. 2 (from Battaglia et al. 2008b).

-0.5.

This well-known relation can thus be used to test our synthetic spectra

at these metallicities. We make a comparison between the CaT lines

from atmospheric models between

-0.5 < [Fe/H] < -2.0 and the best fit linear

relation for globular clusters as given in Eqs. (1) and (2) in Sect. 2 (from Battaglia et al. 2008b).

Some approximations are needed to enable a CaT analysis with synthetic spectra which is comparable to observations.

1. The synthetic spectra are all degraded to a resolution of R=6500,

the resolution of VLT/FLAMES used in Medusa mode with the

GIRAFFE LR (LR8) grating as was used in the observational

determination of the empirical relations given above. The equivalent

widths for the two strongest CaT lines are measured using the same

fitting routine as in Battaglia et al. (2008b): a Gaussian fit with a correction which comes from a comparison with a the summed flux contained in a 15 ![]() wide region centered on each line. The correction is necessary to

account for the wings in the strong lines which are distinctly

non-Gaussian in shape. Since the CaT lines can have a variety of

shapes for a range of metallicities, as shown in Fig. 1,

it is in general not advisable to fit them using a single profile.

The disadvantage of using just numerical integration of the observed

spectra is that there are also some weaker lines in this wavelength

range that may vary differently with changing stellar atmospheric

parameters than the CaT lines themselves (Carrera et al. 2007).

Taking these considerations into account, we thus use a combination of

both methods. Weak nearby lines in the spectrum still introduce a small

dependence of the measured CaT EW on resolution though,

since they are more likely to be absorbed into the Gaussian fit at a

lower resolution. This dependence is already present the lowest

metallicity in our grid and gets stronger at higher metallicity,

due to the increasing prominence of the non-Gaussian wings.

wide region centered on each line. The correction is necessary to

account for the wings in the strong lines which are distinctly

non-Gaussian in shape. Since the CaT lines can have a variety of

shapes for a range of metallicities, as shown in Fig. 1,

it is in general not advisable to fit them using a single profile.

The disadvantage of using just numerical integration of the observed

spectra is that there are also some weaker lines in this wavelength

range that may vary differently with changing stellar atmospheric

parameters than the CaT lines themselves (Carrera et al. 2007).

Taking these considerations into account, we thus use a combination of

both methods. Weak nearby lines in the spectrum still introduce a small

dependence of the measured CaT EW on resolution though,

since they are more likely to be absorbed into the Gaussian fit at a

lower resolution. This dependence is already present the lowest

metallicity in our grid and gets stronger at higher metallicity,

due to the increasing prominence of the non-Gaussian wings.

Some of the more prominent weak lines which can be present in the wings of the two strongest CaT lines are the hydrogen Paschen lines. Their strength mainly depends on the temperature of the star (the hotter the stronger) and also to a lesser extend on its gravity (increasing with decreasing gravities). In the more metal-rich part of our grid the Paschen lines fall within the broad wings of the CaT lines and have a direct effect on the EW measurement of the CaT line. However, within the range of parameters we use in our models, the maximum contribution of the Paschen lines to the CaT EW measured is 39 mÅ, which is negligible compared to the total CaT EW. In the more metal-poor part of the grid the CaT lines are narrower and well separated from the Paschen lines. Nonetheless, the Paschen lines can still influence the CaT EW by effecting the placement of the continuum. Also this effect we find to be negligible at our grid parameters, at maximum the CaT EW is changed by 3.5%.

2. Not all the models in our grid, each of them a particular

combination of effective temperature, gravity and metallicity, will

represent real stars on the RGB. To determine which models best

compare to real stars we use two sets of isochrones, the

BaSTI isochrones (Pietrinferni et al. 2004) and the Yonsei-Yale set (e.g., Demarque et al. 2004; Yi et al. 2001).

Both sets can be interpolated to obtain exactly the desired metallicity

and age for a particular isochrone. The Yonsei-Yale set has the

advantage that they go down to [Fe/H] = -3.6 at [![]() /Fe] = +0.4,

whereas the lowest value for the BaSTI set is

[Fe/H] = -2.6. It is well known that different sets of

isochrones do not always give identical results. On top of that,

different ages give (slightly) different parameters for the

RGB stars. In Fig. 3

the grid of models in effective temperature versus gravity is plotted

along with the relations from the theoretical isochrones. In the

two panels the differences due to age, metallicity and the use of

different sets of isochrones are illustrated. Based in Fig. 3 we decide to linearly interpolate in

/Fe] = +0.4,

whereas the lowest value for the BaSTI set is

[Fe/H] = -2.6. It is well known that different sets of

isochrones do not always give identical results. On top of that,

different ages give (slightly) different parameters for the

RGB stars. In Fig. 3

the grid of models in effective temperature versus gravity is plotted

along with the relations from the theoretical isochrones. In the

two panels the differences due to age, metallicity and the use of

different sets of isochrones are illustrated. Based in Fig. 3 we decide to linearly interpolate in ![]() space between the models that are as close as possible to the isochrones and add another 0.25 in

space between the models that are as close as possible to the isochrones and add another 0.25 in ![]() space

on each side to account for uncertainties within the isochrone models

as well as the differences between the isochrones of different ages.

These uncertainties are shown as error bars on the equivalent widths

from synthetic spectra. Note that these represent maximum and minimum

values for the equivalent widths and that these errors

are systematic.

space

on each side to account for uncertainties within the isochrone models

as well as the differences between the isochrones of different ages.

These uncertainties are shown as error bars on the equivalent widths

from synthetic spectra. Note that these represent maximum and minimum

values for the equivalent widths and that these errors

are systematic.

3. Because our synthetic grid is not a stellar system, the

HB magnitude does not have an obvious meaning. Therefore,

to compare our models with empirical relations which require the

height above the HB as an input parameter, we have to rely on

observational or theoretical relations between MV of the HB (

![]() )

of a system and its metallicity. The MV

for each of the grid RGB stars is taken from the isochrones. This

value is consistent with the value we get if we calculate MV from

)

of a system and its metallicity. The MV

for each of the grid RGB stars is taken from the isochrones. This

value is consistent with the value we get if we calculate MV from

![]() using the bolometric correction of giant stars from Alonso et al. (1999). To determine

using the bolometric correction of giant stars from Alonso et al. (1999). To determine

![]() we use the relation given in Catelan & Cortés (2008)

which is calculated using theoretical models for

RR Lyrae stars. Within its uncertainties, this relation is in

excellent agreement with observations of the

we use the relation given in Catelan & Cortés (2008)

which is calculated using theoretical models for

RR Lyrae stars. Within its uncertainties, this relation is in

excellent agreement with observations of the

![]() of globular clusters (e.g., Rich et al. 2005).

of globular clusters (e.g., Rich et al. 2005).

In order to make a fair comparison between the synthetic spectra

and the empirical relation, the atmospheric model properties were

chosen to be as close as possible to known globular cluster properties.

In the atmospheric models we therefore chose to use the alpha-enhanced

models with [![]() /Fe] = +0.4,

except at the higher metallicities ([Fe/H] > -1.0) where

the MARCS grid only provides lower [

/Fe] = +0.4,

except at the higher metallicities ([Fe/H] > -1.0) where

the MARCS grid only provides lower [![]() /Fe] to match observations in the Milky Way. Furthermore, for all [

/Fe] to match observations in the Milky Way. Furthermore, for all [![]() /Fe] = +0.4 models,

[Ca/Fe] was set to +0.25 in the Turbospectrum program, which

even more closely resembles the true values observed in the Galactic

halo globular clusters (e.g., Pritzl et al. 2005). For the isochrone set we use an age of 12 Gyr, comparable to measured ages for the globular clusters (e.g., Krauss & Chaboyer 2003).

We find that for a range of old ages, between 8

and 15 Gyr, the exact choice of the isochrone age does not

significantly affect our results.

/Fe] = +0.4 models,

[Ca/Fe] was set to +0.25 in the Turbospectrum program, which

even more closely resembles the true values observed in the Galactic

halo globular clusters (e.g., Pritzl et al. 2005). For the isochrone set we use an age of 12 Gyr, comparable to measured ages for the globular clusters (e.g., Krauss & Chaboyer 2003).

We find that for a range of old ages, between 8

and 15 Gyr, the exact choice of the isochrone age does not

significantly affect our results.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=15cm,clip]{13759fg4.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13759-09/Timg37.png)

|

Figure 4:

We plot equivalent widths of the two strongest CaT lines which are

measured in the synthetic spectra (symbols) and the empirical relation

from Battaglia et al. (2008b) (black dash-dotted lines) versus (

|

The successful comparison between our synthetic spectra and the

empirical relations, using the BaSTI and the Yonsei-Yale sets of

isochrones, is shown in Fig. 4.

The results for the two different sets of isochrones are comparable,

although the BaSTI isochrones give a slightly better coverage and

agreement at the tip of the RGB. In general, we obtain a good

match between the predictions of our synthetic spectra equivalent

widths and the empirical relation, especially for the most luminous

part of the RGB and at intermediate metallicities where the relation is

best studied. At [Fe/H] = -0.5 the match is clearly

worse, but also the empirical relation is not well constrained at this

metallicity. We also find a larger deviation from the empirical

relation closer to the HB. It was already predicted by Pont et al. (2004) using models that the strength of the CaT lines increases more rapidly for the more luminous part of the RGB. Later, Carrera et al. (2007)

reported a nonlinear tendency in the equivalent width versus absolute

magnitude relation at fainter magnitudes from an observational study of

a large sample of RGB stars in open and globular clusters over a

wide range of magnitudes. Recently, Da Costa et al. (2009)

reported a flattening of the slope of the relation below the HB in

two globular clusters. These observations and early predictions appear

to confirm the effect we see in our synthetic spectra. This trend is

observed to be even stronger below the HB (Da Costa et al. 2009; Carrera et al. 2007), and clearly shows one has to be very cautious applying any of the

![]() relations

to faint stars, especially below the HB. In this paper, we

only focus on the RGB above the HB.

relations

to faint stars, especially below the HB. In this paper, we

only focus on the RGB above the HB.

4.2 Further calibration

In addition to the comparison with the existing empirical relations,

we also calibrate our spectral synthesis models with two (very) well

studied examples, namely the Sun using the Kurucz solar flux atlas (Kurucz et al. 1984) and Arcturus using the Hinkle Arcturus atlas (Hinkle et al. 2000).

Although the match for the Sun is very good, the initial comparison

between the observational Hinkle Arcturus spectrum and the synthesized

spectrum from our models was not satisfactory, especially in the wings

of the strongest CaT line (![]() 8542 Å).

Because this line is extremely broad, it is possible that some of

the outer parts of the line were mistakenly taken to be the continuum

level during the continuum subtraction. After careful renormalization

of the continuum at this wavelength region we were able to get an

acceptable match using the abundances for Arcturus from Fulbright et al. (2007).

8542 Å).

Because this line is extremely broad, it is possible that some of

the outer parts of the line were mistakenly taken to be the continuum

level during the continuum subtraction. After careful renormalization

of the continuum at this wavelength region we were able to get an

acceptable match using the abundances for Arcturus from Fulbright et al. (2007).

5 The CaT lines at [Fe/H] < -2.5

5.1 The empirical relation

Given the success in reproducing the well established calibration of CaT in the range -2.0 ![]() [Fe/H]

[Fe/H] ![]() -0.5, we now extend our synthetic spectral analysis down to [Fe/H] = -4.0. The results are shown in Fig. 5

together with the empirical relation extended linearly to the

low-metallicity regime. We use the Yonsei-Yale isochrone set since it

extends down to the lowest metallicities

-0.5, we now extend our synthetic spectral analysis down to [Fe/H] = -4.0. The results are shown in Fig. 5

together with the empirical relation extended linearly to the

low-metallicity regime. We use the Yonsei-Yale isochrone set since it

extends down to the lowest metallicities![]() . From a comparison of the empirical relation (dash-dotted lines) and the synthetic spectra (colored symbols) in Fig. 5,

it is obvious that the match with the empirical linear relations

breaks down (as expected) at low metallicities, starting from

[Fe/H] < -2.0. For example, the empirical relation

for [Fe/H] = -3.0 lies below the synthetic spectra

predictions for [Fe/H] = -4.0 models for fainter

RGB stars.

. From a comparison of the empirical relation (dash-dotted lines) and the synthetic spectra (colored symbols) in Fig. 5,

it is obvious that the match with the empirical linear relations

breaks down (as expected) at low metallicities, starting from

[Fe/H] < -2.0. For example, the empirical relation

for [Fe/H] = -3.0 lies below the synthetic spectra

predictions for [Fe/H] = -4.0 models for fainter

RGB stars.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{13759fg5.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13759-09/Timg39.png)

|

Figure 5:

From synthetic analysis we measure the equivalent widths of the two strongest CaT lines as in Fig. 4

extended to lower metallicities. Color coding and symbols for

-2.5 < [Fe/H] < -0.5 is the same as in

Fig. 4,

the additional metallicities are [Fe/H] = -2.5 (purple

squares), [Fe/H] = -3.0 (blue plus signs), and

[Fe/H] = -4.0 (pink crosses). The empirical relations (black

dash-dotted lines), including 1 |

As can be seen in Fig. 5, there is also a trend with the inferred height of a ``star'' above the HB (e.g., surface gravity and temperature) and the deviation of the ``observed'' metallicity compared to the metallicity of the model, for the low-metallicity models. This demonstrates the fact that not just the equivalent width, but also the slope of the relation is changing. At lower metallicities, the equivalent width of the line becomes less sensitive to variations in gravity or temperature of the star (i.e., its position on the RGB).

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{13759fg6.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13759-09/Timg40.png)

|

Figure 6: From synthetic analysis, we plot the ``real'' input value for [Fe/H] in the model versus the ``observed'' value of [Fe/H] for the grid of models, obtained by treating the model spectra as if they were observed in the DART program. For each ``real'' [Fe/H] input value are several points representing RGB stars of the same metallicity at several places along the RGB. Error bars are calculated from the uncertainties shown in Fig. 4 and described in the text. If the CaT method would work perfectly all models should fall (within their uncertainties) on the one-to-one relation shown by the solid black line. Clearly there is an increasing deviation starting at [Fe/H] < -2. Same symbols and color coding used as in Fig. 5. |

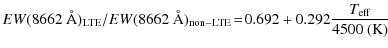

The mismatch between the extended empirical relation and the synthetic

modeling predictions at low metallicities is emphasized in Fig. 6

where the input metallicity of the models is plotted versus the

metallicity obtained from the empirical relation as given in Eqs. (1) and (2). From Fig. 6,

we obtain valuable insight into how extremely low-metallicity spectra

would appear in, for instance, the DART sample of

classical dwarf galaxies. While some of the models with input

[Fe/H] ![]() -2.5

are correctly reproduced by the synthetic spectral method, there are

also examples where the metallicity is seriously overestimated. The

linear empirical relation thus offers no means to discriminate between

very low or extremely low metallicity RGB stars.

-2.5

are correctly reproduced by the synthetic spectral method, there are

also examples where the metallicity is seriously overestimated. The

linear empirical relation thus offers no means to discriminate between

very low or extremely low metallicity RGB stars.

6 A new calibration

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{13759fg7.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13759-09/Timg41.png)

|

Figure 7: Same as Fig. 5, but with our new calibration overplotted as thick solid black lines. |

To re-calibrate the relation between the CaT equivalent width and

metallicity for the low-metallicity regime, we use the equivalent

widths obtained from our synthetic spectra. In the relation obtained by

Battaglia et al. (2008b), there are three free parameters to fit the slope of the relation as a function of height above the HB, expressed in W', and a linear relation between W'

and [Fe/H]. To extend this calibration we expect to need at least

two more parameters to fit the dominant features of the low-metallicity

models in one relation: the changing slope with [Fe/H] and the changing

offset between lines of equal metallicity. As input into our

fitting routine we use the results from the synthetic spectra grid from

models described in Table 1 with [![]() /Fe] = +0.4

(and [Ca/Fe] set to +0.25). We use the Yonsei-Yale set of

isochrones, because only those provide the low metallicities needed for

the analysis. For the fitting we use the IDL function MPFIT2DFUN (Markwardt 2009)

to fit a plane relating the absolute magnitude and equivalent widths of

the synthetic models to their metallicity and an F-test to distinguish

the best fit. Not all models are given the same weights in

the fit, for the models both higher up the RGB (

/Fe] = +0.4

(and [Ca/Fe] set to +0.25). We use the Yonsei-Yale set of

isochrones, because only those provide the low metallicities needed for

the analysis. For the fitting we use the IDL function MPFIT2DFUN (Markwardt 2009)

to fit a plane relating the absolute magnitude and equivalent widths of

the synthetic models to their metallicity and an F-test to distinguish

the best fit. Not all models are given the same weights in

the fit, for the models both higher up the RGB (

![]() < -1) and at intermediate metallicities (-1.5

< -1) and at intermediate metallicities (-1.5 ![]() [Fe/H]

[Fe/H] ![]() -0.5)

we give higher weights since these models represent the best studied

region of, and best matching models with, the empirical relation.

Additionally, all models at the (extremely) low-metallicity regime we

are particularly interested in (below [Fe/H] = -2) are

also weighted more. On the other hand, the highest metallicity models

(at [Fe/H] = -0.5) are weighted less, since these have

higher uncertainties and fit less well the empirical relation. Several

functional forms have been explored. The best fit was obtained by a

simple linear relation in both luminosity and equivalent width,

as in the classical empirical calibrations, with merely two extra

terms. One term of equivalent width to the power -1.5 to account

for the variations at low metallicities, one cross term to account for

the slight non-linear slope, as given in Eq. (5).

-0.5)

we give higher weights since these models represent the best studied

region of, and best matching models with, the empirical relation.

Additionally, all models at the (extremely) low-metallicity regime we

are particularly interested in (below [Fe/H] = -2) are

also weighted more. On the other hand, the highest metallicity models

(at [Fe/H] = -0.5) are weighted less, since these have

higher uncertainties and fit less well the empirical relation. Several

functional forms have been explored. The best fit was obtained by a

simple linear relation in both luminosity and equivalent width,

as in the classical empirical calibrations, with merely two extra

terms. One term of equivalent width to the power -1.5 to account

for the variations at low metallicities, one cross term to account for

the slight non-linear slope, as given in Eq. (5).

Table 2: The parameters of the observed stars used for verification of the modeling results at low metallicities.

This relation is only calibrated for RGB stars above the HB and

should thus not be applied to stars outside

![]() .

We want to stress that this relation remains ``empirical'', in the

sense that no theoretical arguments are used to find the best fitting

formula. The corresponding fit is shown in Fig. 7,

it fits both the higher metallicity end (and in this regime

the existing empirical relation) and the lower metallicity models well

within their uncertainties. From Fig. 8,

which shows the residual of the fit in the right panel, it can be

seen that the new calibration performs less well at the

high-metallicity end of the calibration ([Fe/H]

.

We want to stress that this relation remains ``empirical'', in the

sense that no theoretical arguments are used to find the best fitting

formula. The corresponding fit is shown in Fig. 7,

it fits both the higher metallicity end (and in this regime

the existing empirical relation) and the lower metallicity models well

within their uncertainties. From Fig. 8,

which shows the residual of the fit in the right panel, it can be

seen that the new calibration performs less well at the

high-metallicity end of the calibration ([Fe/H] ![]() -0.5),

but even there the error is still within a typical observational

error bar for [Fe/H]. We estimate the typical maximum error on the

fitted parameters in Eq. (5) to be

-0.5),

but even there the error is still within a typical observational

error bar for [Fe/H]. We estimate the typical maximum error on the

fitted parameters in Eq. (5) to be ![]() 8%, on the basis of Monte-Carlo simulations of the uncertainties on (

8%, on the basis of Monte-Carlo simulations of the uncertainties on (

![]() )

and the equivalent widths. These reasonably low error values convince

us that the parameters in our new CaT calibration are quite robust

to changes in our approximations.

)

and the equivalent widths. These reasonably low error values convince

us that the parameters in our new CaT calibration are quite robust

to changes in our approximations.

Additionally, in Appendix A, we describe the relation between [Fe/H], EW and MV and MI, to enable the use of the CaT lines as a metallicity estimator for individual RGB stars in systems without a well-defined horizontal branch or for individual RGB field stars.

6.1 Verifying the new calibration at low-metallicity

To verify the reliability of our models at very low-metallicities ([Fe/H] ![]() -2.0),

we have measured the CaT equivalent widths for six low-metallicity

halo stars with existing high-resolution spectroscopic analyses. The

properties of these stars are given in Table 2. Their CaT spectra are degraded to a resolution of R=6500, equal to the resolution of the synthetic spectra grid, and their CaT EWs are measured as described in Sect. 4.1. MV for these halo stars is calculated from

-2.0),

we have measured the CaT equivalent widths for six low-metallicity

halo stars with existing high-resolution spectroscopic analyses. The

properties of these stars are given in Table 2. Their CaT spectra are degraded to a resolution of R=6500, equal to the resolution of the synthetic spectra grid, and their CaT EWs are measured as described in Sect. 4.1. MV for these halo stars is calculated from

![]() using the spectroscopically defined values for gravity and temperature and the bolometric correction of giant stars from Alonso et al. (1999).

Additionally their height above the horizontal branch can be

approximated using their spectroscopic metallicity and the relation

from Catelan & Cortés (2008). In Fig. 9

the results of applying our new CaT calibration to these

observations are shown. There is clearly a very good agreement.

using the spectroscopically defined values for gravity and temperature and the bolometric correction of giant stars from Alonso et al. (1999).

Additionally their height above the horizontal branch can be

approximated using their spectroscopic metallicity and the relation

from Catelan & Cortés (2008). In Fig. 9

the results of applying our new CaT calibration to these

observations are shown. There is clearly a very good agreement.

Additionally, one star from the Boötes I dwarf galaxy as studied by Norris et al. (2010,2008)

using medium- and high-resolution spectroscopy is also plotted.

For this star only one of the two strongest CaT lines could

be measured by Norris et al. (2008) with

confidence, and the total equivalent width for both lines was inferred

using this single line and the observed ratio between the two lines

from Norris et al. (1996,2008)![]() Norris et al. (2008)

find [Fe/H] = -3.45 from medium-resolution spectroscopy using

the Ca II H and K lines, which is very close to the

value we deduce from the EW of the CaT line in the

same spectrum, [Fe/H] = -3.32. In their subsequent

high-resolution follow-up study [Fe/H] is measured directly from

Fe lines, which gives [Fe/H] = -3.7 (Norris et al. 2010).

Norris et al. (2008)

find [Fe/H] = -3.45 from medium-resolution spectroscopy using

the Ca II H and K lines, which is very close to the

value we deduce from the EW of the CaT line in the

same spectrum, [Fe/H] = -3.32. In their subsequent

high-resolution follow-up study [Fe/H] is measured directly from

Fe lines, which gives [Fe/H] = -3.7 (Norris et al. 2010).

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{13759fg9.eps}\vspace*{-2mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13759-09/Timg49.png)

|

Figure 9: Plotted with our new CaT calibration (colored lines) are the well-studied RGB stars in the Milky Way halo (black diamonds) and one extremely low-metallicity star in Boötes I (black asterisk) which are all described in Table 2. |

6.2 The DART low-metallicity follow-up program

As a complementary approach to determine if there are any extremely low metallicity stars in the dwarf galaxies, DART has undertaken a follow-up program to obtain HR spectroscopy using the Subaru Telescope High Dispersion Spectrograph, the UVES spectrograph at VLT, and the MIKE spectrograph at Magellan for a sample of stars with CaT [Fe/H] < -2.5 (Aoki et al. 2009; Tafelmeyer et al., in prep.; Venn et al., in prep.). These HR spectra were taken as an addition to the already existing HR spectra from the main program of DART using VLT/FLAMES with the GIRAFFE spectrograph in Medusa mode (Tolstoy et al. 2009; Aoki et al. 2009; Letarte et al., in press; Hill et al., in prep.; Venn et al., in prep.). In these follow-up programmes several extremely low-metallicity stars have been found, with [Fe/H] values below -3.0 (Aoki et al. 2009; Venn et al., in prep.; Tafelmeyer et al., in prep.) and even around -4.0 (Tafelmeyer et al., in prep.). Figure 10 shows all the HR results, compared to their LR [Fe/H] values inferred from the CaT lines using both the old and the new calibration. In this figure the limiting range of the old (linear) calibration is also clearly visible, only the new calibration extends down to the lowest metallicities. For the lower metallicities the error bars become larger, due to the fact that the relations for different metallicities lie closer together and thus a similar error in equivalent width results in a larger error in [Fe/H]. Taking this into account, the new calibration appears to give an accurate prediction of the HR [Fe/H] values.

There are however some stars showing a deviation larger than 1![]() ,

where the most clear example is the extremely metal-poor star in

Fornax. This deviation might be (partly) due to non-LTE effects or

other deficiencies in the modeling of the HR spectrum in order to

derive the stellar parameters and abundances for this really

low-gravity star. Some support of this explanation is the fact that the

agreement between the LR (CaT) and HR results improves when

[Fe II/H] is used instead of [Fe I/H],

most clearly for the extremely metal-poor Fornax star (Tafelmeyer

et al., in prep.). Non-LTE effects are generally

negligible for the dominant ionization state of Fe II (e.g., Thévenin & Idiart 1999; Mashonkina et al. 2010; Kraft & Ivans 2003), however for Fe I the non-LTE effects are expected to be more significant in low-metallicity, low-gravity stars (e.g., Thévenin & Idiart 1999; Mashonkina et al. 2010; Gehren et al. 2001).

,

where the most clear example is the extremely metal-poor star in

Fornax. This deviation might be (partly) due to non-LTE effects or

other deficiencies in the modeling of the HR spectrum in order to

derive the stellar parameters and abundances for this really

low-gravity star. Some support of this explanation is the fact that the

agreement between the LR (CaT) and HR results improves when

[Fe II/H] is used instead of [Fe I/H],

most clearly for the extremely metal-poor Fornax star (Tafelmeyer

et al., in prep.). Non-LTE effects are generally

negligible for the dominant ionization state of Fe II (e.g., Thévenin & Idiart 1999; Mashonkina et al. 2010; Kraft & Ivans 2003), however for Fe I the non-LTE effects are expected to be more significant in low-metallicity, low-gravity stars (e.g., Thévenin & Idiart 1999; Mashonkina et al. 2010; Gehren et al. 2001).

7 Alpha element dependence on the CaT lines

It is naturally expected that differences in [Ca/Fe] will significantly

change the equivalent width of the CaT lines, and therefore alter

the observed relation between equivalent width and [Fe/H]. The

MARCS collaboration also provides model atmospheres where the ![]() elements are not enhanced, but are kept similar to the ratio in the Sun for all models with [Fe/H]

elements are not enhanced, but are kept similar to the ratio in the Sun for all models with [Fe/H] ![]() -2. Figure 11

shows that we recover this difference in our synthetic spectra.

Qualitatively, the space between the enhanced and solar

[Ca/Fe] models at equal [Fe/H] seems to agree with the step

taken in abundance. The equivalent width in our grid of synthetic

spectra does trace the Ca abundance. Since the strength of any

line depends on the line opacity divided by the continuous opacity,

it is expected that also other elements than Ca can affect the

CaT line EW. If these elements contribute free electrons these can enhance the H- concentration

and therefore affect the continuous opacity. Which element contributes

most free electrons is dependent on the effective temperature and layer

of the atmosphere of the star in consideration, but for cool

stellar atmospheres in general the main sources of electrons are Mg,

Fe, Si, Ca, Na, and Al (Shetrone et al. 2009). Since thus both Fe and some of the

-2. Figure 11

shows that we recover this difference in our synthetic spectra.

Qualitatively, the space between the enhanced and solar

[Ca/Fe] models at equal [Fe/H] seems to agree with the step

taken in abundance. The equivalent width in our grid of synthetic

spectra does trace the Ca abundance. Since the strength of any

line depends on the line opacity divided by the continuous opacity,

it is expected that also other elements than Ca can affect the

CaT line EW. If these elements contribute free electrons these can enhance the H- concentration

and therefore affect the continuous opacity. Which element contributes

most free electrons is dependent on the effective temperature and layer

of the atmosphere of the star in consideration, but for cool

stellar atmospheres in general the main sources of electrons are Mg,

Fe, Si, Ca, Na, and Al (Shetrone et al. 2009). Since thus both Fe and some of the ![]() elements have to be considered as important electron donors, this can significantly affect the dependence of the CaT EW on the [

elements have to be considered as important electron donors, this can significantly affect the dependence of the CaT EW on the [![]() /Fe] ratio.

Nevertheles we find that, within the abundance parameters we adopt in

this study, the Ca abundance itself is by far the dominant

factor determining the EW of the CaT line, as can be seen in Fig. 11.

/Fe] ratio.

Nevertheles we find that, within the abundance parameters we adopt in

this study, the Ca abundance itself is by far the dominant

factor determining the EW of the CaT line, as can be seen in Fig. 11.

However, when comparing the sensitivity of the CaT equivalent width

measurements of RGB stars in Sculptor and Fornax with

high-resolution [Fe/H] and [Ca/H] measurements Battaglia et al. (2008b)

find that the CaT equivalent width is actually a more robust estimator

of Fe than Ca. This would suggest that it is therefore not

advisable to use the CaT as a linear estimator for [Ca/H] (see Battaglia et al. 2008b, and their Figs. 10 and 12). This result is not expected from the theoretical expectations shown in Fig. 11.

There are several factors that may contribute to this apparent

discrepancy between the modeling and observational results. First,

in our grid of synthetic spectra we assume the relative abundance

of Ca to the other ![]() elements

to stay constant, an assumption that not necessarily holds for all

RGB stars. The extra free electrons donated by the other

elements

to stay constant, an assumption that not necessarily holds for all

RGB stars. The extra free electrons donated by the other ![]() elements might affect the strength of the CaT line through the continuous opacity as described above. Shetrone et al. (2009)

find that a 0.5 dex decrease in the electron contributors can

increase the CaT line strength enough to mimic

a Ca abundance increase of

elements might affect the strength of the CaT line through the continuous opacity as described above. Shetrone et al. (2009)

find that a 0.5 dex decrease in the electron contributors can

increase the CaT line strength enough to mimic

a Ca abundance increase of ![]() 0.2 or even

0.2 or even ![]() 0.4

depending on the atmosphere parameters of the star. However,

in Fornax we generally find that the important electron donors Fe

and Mg are increased relatively to the values in our grid at

similar [Ca/H], while we still measure the CaT lines to be

too strong relative to the [Ca/H] measurements directly from Ca I lines.

This result clearly indicates that the effect of electron donors can

not be driving the offset between [Ca/H] derived from CaT and

HR Ca I analyses. Second, the HR Ca abundances are usually derived from fewer Ca I lines compared to the large number of HR Fe I lines available and are therefore subject to larger observational errors. Third, the HR determination of the Ca I abundance is subject to non-LTE effects (Mashonkina et al. 2007).

If non-LTE effects are included in the analysis of the

HR spectra to determine the Ca abundances this might lead to

a closer match in Ca abundances derived from the Ca I and CaT lines. To investigate this more closely we have modeled both the Ca I

and CaT line strengths using abundances and atmospheric parameters

from the well-studied halo star CD -38 245 (e.g., Cayrel et al. 2004) as a test case. The modeling, using the same models and techniques as described in Sect. 3.2,

is performed for [Ca/Fe] = +0.4 in LTE and non-LTE to

determine the offset from non-LTE to LTE abundances. The results

are shown in Table 3. It can be seen that the LTE approximation has an effect on the determination of the Ca abundance from the Ca I lines (a difference of over 0.2 dex for the Ca I line at

0.4

depending on the atmosphere parameters of the star. However,

in Fornax we generally find that the important electron donors Fe

and Mg are increased relatively to the values in our grid at

similar [Ca/H], while we still measure the CaT lines to be

too strong relative to the [Ca/H] measurements directly from Ca I lines.

This result clearly indicates that the effect of electron donors can

not be driving the offset between [Ca/H] derived from CaT and

HR Ca I analyses. Second, the HR Ca abundances are usually derived from fewer Ca I lines compared to the large number of HR Fe I lines available and are therefore subject to larger observational errors. Third, the HR determination of the Ca I abundance is subject to non-LTE effects (Mashonkina et al. 2007).

If non-LTE effects are included in the analysis of the

HR spectra to determine the Ca abundances this might lead to

a closer match in Ca abundances derived from the Ca I and CaT lines. To investigate this more closely we have modeled both the Ca I

and CaT line strengths using abundances and atmospheric parameters

from the well-studied halo star CD -38 245 (e.g., Cayrel et al. 2004) as a test case. The modeling, using the same models and techniques as described in Sect. 3.2,

is performed for [Ca/Fe] = +0.4 in LTE and non-LTE to

determine the offset from non-LTE to LTE abundances. The results

are shown in Table 3. It can be seen that the LTE approximation has an effect on the determination of the Ca abundance from the Ca I lines (a difference of over 0.2 dex for the Ca I line at ![]() = 6162

= 6162 ![]() ). In the LTE approximation, the agreement between the abundances derived from the Ca I and CaT lines is very poor, CaT analysis results in a Ca abundance much greater than for Ca I.

In non-LTE, we are able to reproduce better all the measured

Ca features in an extremely metal-poor star. The remaining

discrepancy probably relates to the outer atmospheric layers that are

not very well modeled - even in non-LTE. To fully resolve the

discrepancy between the Ca I and CaT results,

one would have to properly explore the effects of specific details

including line profile fitting and uncertainties in the stellar

parameters.

). In the LTE approximation, the agreement between the abundances derived from the Ca I and CaT lines is very poor, CaT analysis results in a Ca abundance much greater than for Ca I.

In non-LTE, we are able to reproduce better all the measured

Ca features in an extremely metal-poor star. The remaining

discrepancy probably relates to the outer atmospheric layers that are

not very well modeled - even in non-LTE. To fully resolve the

discrepancy between the Ca I and CaT results,

one would have to properly explore the effects of specific details

including line profile fitting and uncertainties in the stellar

parameters.

The stars in the dataset described by Battaglia et al. (2008b) which show the largest discrepancies in CaT compared to [Ca/H], are typically much more metal-rich RGB stars than CD -38 245. For this regime we have not modeled the non-LTE effects in Ca I lines. Most of the discrepant stars are from the Fornax dwarf galaxy, where we were just able to target its brightest population of RGB stars due to the relatively large distance to this dwarf galaxy (see also Sect. 8.2). This means we are also statistically probing closer to the tip of the RGB, where we find the lower gravity stars for which the outer layers are more diffuse and thus more difficult to model - certainly assuming LTE.

Table 3: Ca abundances for CD -38 245.

8 Implications for the DART survey

Our new CaT-[Fe/H] calibration enables a more direct search for

extremely metal-poor stars in existing datasets, like the large

DART sample of CaT measurements in RGB stars of four

classical dwarf galaxies (Sculptor, Fornax, Carina, and Sextans). These

DART samples were observed in LR (![]() )

Medusa mode using the European Southern Observatory (ESO) VLT/FLAMES facility (Pasquini et al. 2002) and are described in Helmi et al. (2006), Koch et al. (2006) and Battaglia et al. (2008a,b,2006).

)

Medusa mode using the European Southern Observatory (ESO) VLT/FLAMES facility (Pasquini et al. 2002) and are described in Helmi et al. (2006), Koch et al. (2006) and Battaglia et al. (2008a,b,2006).

In Fig. 12 we

overplot the complete low-resolution samples for the four galaxies

observed in the DART program, Sculptor, Fornax, Carina and

Sextans, along with the new CaT calibration (colored lines). All

observed RGB stars, which are likely to be members, from DART are

shown as small gray circles. All stars have a signal-to-noise ratio

larger than 10 (per Å), a velocity error smaller

than 5 km s-1 and a velocity which is within 3![]() of the systemic radial velocity of the galaxy (for Fornax 2.5

of the systemic radial velocity of the galaxy (for Fornax 2.5![]() is used, because of the larger contribution from Milky Way foreground). These criteria are identical to those applied by Battaglia et al. (2008a,2006). We use

is used, because of the larger contribution from Milky Way foreground). These criteria are identical to those applied by Battaglia et al. (2008a,2006). We use

![]() for the dwarf galaxies as given in Irwin & Hatzidimitriou (1995). For the errors in the sum of equivalent widths we use the results of Battaglia et al. (2008b)

who found that the random error from repeated measurements of the

low-resolution sample in the sum of the two broadest lines is well

represented by

for the dwarf galaxies as given in Irwin & Hatzidimitriou (1995). For the errors in the sum of equivalent widths we use the results of Battaglia et al. (2008b)

who found that the random error from repeated measurements of the

low-resolution sample in the sum of the two broadest lines is well

represented by

![]()

![]() 6/(S/N). Although this error can be quite extensive (mean error bars per galaxy and luminosity bin are shown in Fig. 12),

there are clearly a number of stars in these galaxies that are

predicted to have [Fe/H] < -3. Our low-metallicity

candidates need to be followed up with high-resolution spectroscopy to

verify our prediction. A small sample of low-metallicity

candidates has already been followed up with high-resolution

spectroscopy within DART, these results are discussed in Sect. 6.2 and in Aoki et al. (2009),

Tafelmeyer et al. (in prep.) and Venn et al.

(in prep.). The extremely metal-poor stars discovered within these

DART follow-up programs in Sculptor, Fornax, Carina, and Sextans and

the one extremely metal-poor Sculptor star discovered by Kirby et al. (2009) and Frebel et al. (2010)

already provide an independent confirmation of our predictions of the

existence of extremely low-metallicity stars in these classical

dwarf galaxies.

6/(S/N). Although this error can be quite extensive (mean error bars per galaxy and luminosity bin are shown in Fig. 12),

there are clearly a number of stars in these galaxies that are

predicted to have [Fe/H] < -3. Our low-metallicity

candidates need to be followed up with high-resolution spectroscopy to

verify our prediction. A small sample of low-metallicity

candidates has already been followed up with high-resolution

spectroscopy within DART, these results are discussed in Sect. 6.2 and in Aoki et al. (2009),

Tafelmeyer et al. (in prep.) and Venn et al.

(in prep.). The extremely metal-poor stars discovered within these

DART follow-up programs in Sculptor, Fornax, Carina, and Sextans and

the one extremely metal-poor Sculptor star discovered by Kirby et al. (2009) and Frebel et al. (2010)

already provide an independent confirmation of our predictions of the

existence of extremely low-metallicity stars in these classical

dwarf galaxies.

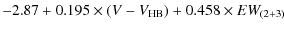

8.1 Old and new calibration: a comparison

It should be noted that the total number of stars affected by the

new calibration in the DART CaT surveys is very small. In the

current DART data set, just 2.5% of the target stars have a

metallicity below [Fe/H] = -2.5, using the calibration of Battaglia et al. (2008b).

Using the new calibration the fraction of low-metallicity stars

increases somewhat to about 7.5%. Still it is important to realize

that ![]() 92.5% of the stars in these systems are at a metallicity which is consistent with both the calibration of Battaglia et al. (2008b) and that given in Sect. 6

of this paper. This implies that the number of low-metallicity

candidates remains very small compared to the total number of observed

stars. This result is illustrated in Fig. 13

where we compare the metallicity distributions for each galaxy using

two calibrations of the CaT data: the calibration for dwarf

galaxies published by Battaglia et al. (2008b)

(in black), and the re-calibration presented here (in red).

It is clear that the overall distributions of metallicities within

these galaxies do not change significantly for the different

CaT calibrations, the only clear differences are in the

low-metallicity tails which have become more populated and more

extended with the new CaT calibration.

92.5% of the stars in these systems are at a metallicity which is consistent with both the calibration of Battaglia et al. (2008b) and that given in Sect. 6

of this paper. This implies that the number of low-metallicity

candidates remains very small compared to the total number of observed

stars. This result is illustrated in Fig. 13

where we compare the metallicity distributions for each galaxy using

two calibrations of the CaT data: the calibration for dwarf

galaxies published by Battaglia et al. (2008b)

(in black), and the re-calibration presented here (in red).

It is clear that the overall distributions of metallicities within

these galaxies do not change significantly for the different

CaT calibrations, the only clear differences are in the

low-metallicity tails which have become more populated and more

extended with the new CaT calibration.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{13759fg13.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13759-09/Timg55.png)

|

Figure 13: Distributions of [Fe/H] for the four dwarf spheroidal galaxies in the DART survey, using both the old calibration (Eqs. (1) and (2), black) and the new calibration (Eq. (5), red) of the CaT lines. The error bars are Poissonian. |

8.2 The low-metallicity tails

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{13759fg14.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13759-09/Timg56.png)

|

Figure 14: The low-metallicity tails of the four classical dwarf galaxies studied by DART as obtained with the new calibration presented here. In the top panel these are normalized at [Fe/H] = -2.5 and compared to the low-metallicity tails from the HES survey (both corrected and raw) from Schörck et al. (2009) and a compilation of ultra-faint dwarf galaxies (Kirby et al. 2008). The bottom panel displays the same low-metallicity tails for the classical- and ultra-faint dwarf galaxies, but normalized to the total number of observed stars in each system. |

Although their number is small relative to the total number of observed

stars, the (extremely) metal-poor stars in each of these galaxies

represents an important and interesting component of the overall

stellar population. The low-metallicity population can reveal details

of the chemical evolution of a particular galaxy and, by comparison,

of the differences and similarities of the early evolutionary

stages of galaxies. In Fig. 14

we show a comparison of the low-metallicity tails from individual

stars, without application of binning or error estimates, in the

four classical dwarf galaxies of DART using our new calibration for the

CaT equivalent widths and in an ensemble of ultra-faint dwarf galaxies

using low-resolution (R ![]() 6500) spectra over a large wavelength range compared with an extensive spectral library (Kirby et al. 2008) and the HES survey of the Milky Way halo (Schörck et al. 2009) measuring [Fe/H] from a combination of indices for the Ca II K and H

6500) spectra over a large wavelength range compared with an extensive spectral library (Kirby et al. 2008) and the HES survey of the Milky Way halo (Schörck et al. 2009) measuring [Fe/H] from a combination of indices for the Ca II K and H![]() lines.