| Issue |

A&A

Volume 513, April 2010

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A73 | |

| Number of page(s) | 13 | |

| Section | The Sun | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/200913321 | |

| Published online | 30 April 2010 | |

Is the 3-D magnetic null point with a convective electric field an efficient particle accelerator?

J.-N. Guo1,2,3 - J. Büchner1 - A. Otto4 - J. Santos1 - E. Marsch1 - W.-Q. Gan2

1 - Max-Planck-Institut für Sonnensystemforschung, Katlenburg-Lindau, Germany

2 -

Purple Mountain Observatory, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Nanjing, PR China

3 -

University of Glasgow, Glasgow, UK

4 -

Geophysical Institute, University of Alaska Fairbanks, USA

Received 18 September 2009 / Accepted 23 January 2010

Abstract

Aims. We study the particle acceleration at a magnetic null

point in the solar corona, considering self-consistent magnetic fields,

plasma flows and the corresponding convective electric fields.

Methods. We calculate the electromagnetic fields by 3-D

magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) simulations and expose charged particles to

these fields within a full-orbit relativistic test-particle approach.

In the 3-D MHD simulation part, the initial magnetic field

configuration is set to be a potential field obtained by extrapolation

from an analytic quadrupolar photospheric magnetic field with a

typically observed magnitude. The configuration is chosen so that the

resulting coronal magnetic field contains a null. Driven by

photospheric plasma motion, the MHD simulation reveals the coronal

plasma motion and the self-consistent electric and magnetic fields. In

a subsequent test particle experiment the particle energies and orbits

(determined by the forces exerted by the convective electric field and

the magnetic field around the null) are calculated in time.

Results. Test particle calculations show that protons can be accelerated up to

![]() near the null if the local plasma flow velocity is of the order of

near the null if the local plasma flow velocity is of the order of

![]() (in solar active regions). The final parallel velocity is much higher

than the perpendicular velocity so that accelerated particles escape

from the null along the magnetic field lines. Stronger convection

electric field during big flare explosions can accelerate protons up to

2 MeV and electrons to 3 keV. Higher initial velocities can

help most protons to be strongly accelerated, but a few protons also

run the risk to be decelerated.

(in solar active regions). The final parallel velocity is much higher

than the perpendicular velocity so that accelerated particles escape

from the null along the magnetic field lines. Stronger convection

electric field during big flare explosions can accelerate protons up to

2 MeV and electrons to 3 keV. Higher initial velocities can

help most protons to be strongly accelerated, but a few protons also

run the risk to be decelerated.

Conclusions. Through its convective electric field and due to

magnetic nonuniform drifts and de-magnetization process, the 3-D null

can act as an effective accelerator for protons but not for electrons.

Protons are more easily de-magnetized and accelerated than electrons

because of their larger Larmor radii. Notice that macroscopic MHD

simulations are blind to microscopic magnetic structures where more

non-adiabatic processes might be taking place. In the real solar

corona, we expect that particles could have a higher probability to

experience a de-magnetization process and get accelerated. To trigger a

significant acceleration of electrons and even higher energetic

protons, however, the existence of a resistive electric field mainly

parallel to the magnetic field is required. A physically reasonable

resistivity model included in resistive MHD simulations is direly

needed for the further investigations of electron acceleration by

parallel electric fields.

Key words: acceleration of particles - magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) - magnetic fields - Sun: flares

1 Introduction

Large solar flares are very powerful explosions near the solar surface, releasing up toRecent solar observations gave important clues about the nature of

particle acceleration on the Sun. According to flare models derived

from these observations, the hard X-ray (HXR) and ![]() -ray

emissions at the chromospheric footpoints of magnetic loops are

supposed to be produced by bremsstrahlung that is related to

high-energy electrons and protons transported downward along flare

loops from acceleration sites higher up in the corona. One can

deduce the particle energy spectrum from the observed HXR and

-ray

emissions at the chromospheric footpoints of magnetic loops are

supposed to be produced by bremsstrahlung that is related to

high-energy electrons and protons transported downward along flare

loops from acceleration sites higher up in the corona. One can

deduce the particle energy spectrum from the observed HXR and

![]() -ray spectrum, considering either thick-target models (where

the injected particles lose most of their energy in Coulomb

collisions with dense, ambient plasma and emit hard X-ray) or

thin-target models (where electrons continuously propagate without

being braked, and the X-ray spectrum is nearly unchanged from the

injection spectrum) (Brown 1971). The appearance of another

coronal HXR source on top of the soft-X-ray loops

(Masuda et al. 1994) is considered to be an indication of the first

energy-release process by accelerated particles encountering the

flare loop. The location of the acceleration site has also been

estimated by calculating the time-of-flight distance

(Aschwanden et al. 1996) from observations. However, the inversion

of photon spectra to particle spectra could not answer the question

how particles are accelerated in the corona and then transported

downward. It is very difficult to infer from observations how the

different acceleration mechanisms work together, and how large-scale

fields, which accelerate particles, can build up. Hence numerical

calculations are necessary to study the microscopic acceleration

process in macroscopic configurations.

-ray spectrum, considering either thick-target models (where

the injected particles lose most of their energy in Coulomb

collisions with dense, ambient plasma and emit hard X-ray) or

thin-target models (where electrons continuously propagate without

being braked, and the X-ray spectrum is nearly unchanged from the

injection spectrum) (Brown 1971). The appearance of another

coronal HXR source on top of the soft-X-ray loops

(Masuda et al. 1994) is considered to be an indication of the first

energy-release process by accelerated particles encountering the

flare loop. The location of the acceleration site has also been

estimated by calculating the time-of-flight distance

(Aschwanden et al. 1996) from observations. However, the inversion

of photon spectra to particle spectra could not answer the question

how particles are accelerated in the corona and then transported

downward. It is very difficult to infer from observations how the

different acceleration mechanisms work together, and how large-scale

fields, which accelerate particles, can build up. Hence numerical

calculations are necessary to study the microscopic acceleration

process in macroscopic configurations.

Magnetic reconnection plays an important role in building up large scale electric fields able to accelerate particles. In the past decades, a substantial amount of work was carried out to investigate the acceleration of test particles in reconnection electromagnetic fields. Three different approaches were taken to model the magnetic and electric fields:

Early researchers often took an analytical prescription of the 2D X-type reconnecting magnetic field, imposing a constant and uniform electric field in the third dimension (e.g. Bruhwiler & Zweibel 1992; Zharkova & Gordovskyy 2004; Efthymiopoulos et al. 2005; Mori et al. 1998; Browning & Vekstein 2001; Speiser 1967,1965; Hannah & Fletcher 2006). The conclusion from these test particle calculations is that with larger electric fields and with additional guiding magnetic fields in the current sheet, particles can be accelerated more efficiently. A longitudinal (guide) magnetic field magnetizes the charged particles and reduces their probability of being ejected from the current sheet so that particles can gain more energy from the electric field (Litvinenko 1996). A power-law distribution of accelerated particles is usually obtained and used for comparison with observations. Nevertheless, the reconnection process itself, which produces the electric field, is neglected and the magnetic and electric fields are prescribed and independent. Therefore these simulations provide a qualitative analysis of the acceleration rather than quantitative results for particle energies and spectrum.

A further step is to apply analytic reconnection solutions for test

particles so as to set up self-consistent electric and magnetic

fields. Based on simplified Ohm's law and Ampere's law, the electric

fields are calculated from the analytic magnetic fields, plasma

velocities and sometimes also from resistivity models

(e.g. Hamilton et al. 2005; Heerikhuisen et al. 2002; Dalla & Browning 2005; Craig & Litvinenko 2002; Dalla & Browning 2008; Sakai 1992; Wood & Neukirch 2005). In these

investigations, the reconnection fields are not independent free

parameters, but are obtained from MHD solutions. This approach

results in a more reliable prediction of the properties of energetic

particle populations. For example, Dalla and Browning

(e.g. Dalla & Browning 2005,2008) used an analytical model

of magnetic and electric fields for kinematically prescribed ideal

plasma flows around a potential 3D null (Priest & Titov 1996).

They studied particle acceleration for spine and fan reconnection.

For the same configuration of the magnetic field, different plasma

flows correspond to different convection electric fields. In the

spine reconnection case, plasma flows in and out through the center

of the null, resulting in an azimuthal electric field. An efficient

acceleration is obtained assuming that the electric field could be

as large as 1 kV/m. In the fan reconnection case, the plasma

flow has another azimuthal component and the acceleration is less

efficient, because fewer particles can reach the regions of strong

electric fields. Note however that the analytic solution of the

electric field contains a singularity at the center (

![]() at R=0), which leads to infinite runaway acceleration.

Also, lack of information on the actual scale and magnitude of the

reconnecting magnetic field as well as the strength and

configuration of the real plasma flows hinders the process of

obtaining realistic acceleration energies and spectrum.

at R=0), which leads to infinite runaway acceleration.

Also, lack of information on the actual scale and magnitude of the

reconnecting magnetic field as well as the strength and

configuration of the real plasma flows hinders the process of

obtaining realistic acceleration energies and spectrum.

A third possible approach is to use the output of self-consistent MHD simulations. Test particles can be traced in the electromagnetic fields obtained e.g. by ideal or resistive MHD numerical simulations (e.g. Turkmani et al. 2006; Schopper et al. 1999; Dmitruk et al. 2003; Karlicky & Barta 2006; Liu et al. 2009). This combination of the test particle method with MHD simulations can provide a semi-realistic and consistent field geometry and strength for the charged particles. Note that because of the coarse resolution of the simulated MHD fields, the magnetic and electric fields have to be interpolated for test particle calculations. Furthermore, a resistivity model has to be carefully used in MHD simulations, as the macroscopic MHD does not consider the microphysical effects that control the resistivity.

The direct way to gain energy without any interference of the

perpendicular gyromotion is acceleration by a parallel electric

field, because magnetized particles can move freely in the direction

parallel to the magnetic field. A simple model as mentioned before

is the direct acceleration inside an electric current sheet on which

a parallel guiding magnetic field is superposed. Nevertheless, the

value of the uniform electric field and the guide magnetic field as

well as the width of current sheet are prescribed without sufficient

support by observations or simulations. For an electron to be

accelerated to 100 keV in a sub-Dreicer electric field, where

![]() ,

an unrealistically long current

sheet of more than 107 m in length would be needed. To reach the

same energy in a super-Dreicer field, the length can be much

shorter, i.e. 102 m, but then the electric field is

unrealistically large (up to

,

an unrealistically long current

sheet of more than 107 m in length would be needed. To reach the

same energy in a super-Dreicer field, the length can be much

shorter, i.e. 102 m, but then the electric field is

unrealistically large (up to

![]() )

(Aschwanden 2002). A more complicated 3D model of parallel

electric fields can be obtained by resistive MHD simulations.

According to Ohm's law, parallel electric fields are balanced as a

resistive electric field

)

(Aschwanden 2002). A more complicated 3D model of parallel

electric fields can be obtained by resistive MHD simulations.

According to Ohm's law, parallel electric fields are balanced as a

resistive electric field

![]() .

So one would

qualitatively expect that a parallel current density

.

So one would

qualitatively expect that a parallel current density

![]() and the existence of a diffusion region with a considerable

resistivity

and the existence of a diffusion region with a considerable

resistivity ![]() would favour direct acceleration. Nevertheless,

any quantitative results based on prescribed

would favour direct acceleration. Nevertheless,

any quantitative results based on prescribed ![]() are somehow

arbitrary, since there is no generic way to to parameterize the

non-ideal property of the collisionless corona plasma in MHD

simulation. For example, test particle acceleration to energies up

to 100 GeV (Turkmani et al. 2006) might be a result of using a

numerical ``hyper-resistivity'', which stabilizes the MHD code. Also,

the parallel electric fields obtained from kinetic processes are in

general confined to regions on the ion inertia scale

(Hesse et al. 1999), much smaller than the macroscopic MHD

grid scales, which can therefore affect and accelerate only a few

particles.

are somehow

arbitrary, since there is no generic way to to parameterize the

non-ideal property of the collisionless corona plasma in MHD

simulation. For example, test particle acceleration to energies up

to 100 GeV (Turkmani et al. 2006) might be a result of using a

numerical ``hyper-resistivity'', which stabilizes the MHD code. Also,

the parallel electric fields obtained from kinetic processes are in

general confined to regions on the ion inertia scale

(Hesse et al. 1999), much smaller than the macroscopic MHD

grid scales, which can therefore affect and accelerate only a few

particles.

On the other hand it might be possible to accelerate particles in a perpendicular convective electric field (which is much larger than resistive electric fields in big Reynolds-number plasmas) due to drift forces and non-adiabatic motion. The mechanism of this acceleration will be further described in Sect. 3. A null point is supposed to be the most probable location to switch on this convective acceleration. Recent observations (e.g. Aulanier et al. 2000; Fletcher et al. 2001; Des Jardins et al. 2009) indicate that 3-D null points are likely to be common in solar corona configurations. Unfortunately, there is no direct observation of the magnitude of the magnetic and electric fields around coronal nulls. One can obtain the magnetic field around a 3-D null point in the corona however by extrapolating typical photospheric fields. A parallel electric field is undoubtedly effective for acceleration. Still, its real strength is quite unknown, because in resistive MHD models it is controlled by ad-hoc prescribed or numerical resistivity. We will therefore concentrate on perpendicular electric fields due to convective electric fields (which are determined by convective plasma flows) to explore the acceleration near a 3-D null point.

The paper is organized as follows. We first describe the codes for MHD simulation and the methods of test-particle calculation. For a 3-D null configuration we analyze theoretically the process of particle acceleration by convective electric fields due to non-adiabatic and drift motion in the non-uniform magnetic fields near the null. Thereafter, we calculate the test-particle energy gains and orbits around the null for different electric fields (plasma flows). We also test different initial distributions of the particles to investigate their acceleration under different initial conditions. We conclude that the convective electric field near the 3-D null point could work as an effective accelerator for protons under realistic assumptions for the field strength and plasma flow velocities. To efficiently accelerate electrons though it appears to be necessary to include parallel electric fields, because electrons are hardly de-magnetized and only shortly drifting in the direction of the convective electric field.

2 The field structure - MHD simulation results

A three-dimensional cartesian MHD model was used to describe the

evolution of the large-scale magnetic and electric fields from the

solar photosphere to the lower corona (e.g. Büchner 2007; Büchner et al. 2004). This MHD model solves the following equations,

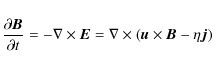

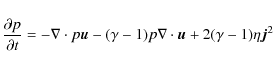

including the continuity Eq. (1),

momentum Eq. (2), induction Eqs. (3) and energy Eq. (4), together with Ohm's law (5), Ampere's

law (6)

and an equation of state (7):

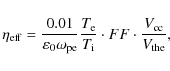

The variables in Eqs. ((1)-(7)) are normalized (dimensionless) by dividing by the normalization quantities. The normalization magnetic field, electric field and plasma velocity have the relationship: E0=B0 u0. Typical values are

Our initial 3-D magnetic field configuration was obtained by

potential-field extrapolation (Otto et al. 2007) of a quadrupolar

analytic magnetic field (see Fig. 2 for images

and Appendix A for equations). The magnitude of the magnetic field

decreases with height. Its maximum value (293 B0) is located at

the bottom of the box. It drops to about 150 B0 at the transition

layer and to just tens of B0 in the corona. In such a

configuration, which should not be too rare in the solar atmosphere,

the magnetic field cancels near the central vertical line of the

box. Since the magnetic field vanishes, a null point is located near

the box center. The approximate location of the magnetic null point

being 46.4, 46.4, 14.6 is determined by the minimum of the magnetic

field magnitude which is

![]() on the MHD grids. This

reference point is not the location of the actual null point (which

requires an interpolation of the magnetic fields between the grid

points), but is in its immediate vicinity. For simplification, we

call this reference point ``the null'' throughout the paper. This

field configuration was our starting point for an investigation of

particle acceleration near a 3-D null point.

on the MHD grids. This

reference point is not the location of the actual null point (which

requires an interpolation of the magnetic fields between the grid

points), but is in its immediate vicinity. For simplification, we

call this reference point ``the null'' throughout the paper. This

field configuration was our starting point for an investigation of

particle acceleration near a 3-D null point.

| Figure 1: Rotating neutral gas velocity imposed at the bottom of the simulation box. |

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

The boundary conditions were defined so that the MHD equations

remained invariant under transformation of the MHD variables

(Otto et al. 2007). The top boundary (at z=Lz) was an open

boundary. The four lateral boundary conditions (at

x=0, x= Lx,

y=0, y=Ly) were line-mirroring symmetric. The bottom boundary

condition (at z=0) for the magnetic field was obtained by

considering that the field should satisfy

![]() and that there should be no horizontal currents

(

and that there should be no horizontal currents

(

![]() ,

and

,

and

![]() )

in the photosphere at z=0. For the plasma

motion, the momentum flux through the bottom was set to be zero

(

uz(z=0)=0), meaning no emerging flux in the photosphere. Since

the horizontal plasma motion in the solar photosphere plays an

important role in the build-up of electric currents in solar

atmosphere (e.g. Büchner 2006; Santos & Büchner 2007), we applied

two vortices of neutral gas motion at the bottom with an average

speed of about

0.0137 u0 (see Fig. 1). The

last term on the right-hand side of the momentum equation (Eq. (2)) represents the transfer of momentum from

the neutral gas to the plasma through collisions. The neutral gas

velocity was set to be a horizontal vortex with

)

in the photosphere at z=0. For the plasma

motion, the momentum flux through the bottom was set to be zero

(

uz(z=0)=0), meaning no emerging flux in the photosphere. Since

the horizontal plasma motion in the solar photosphere plays an

important role in the build-up of electric currents in solar

atmosphere (e.g. Büchner 2006; Santos & Büchner 2007), we applied

two vortices of neutral gas motion at the bottom with an average

speed of about

0.0137 u0 (see Fig. 1). The

last term on the right-hand side of the momentum equation (Eq. (2)) represents the transfer of momentum from

the neutral gas to the plasma through collisions. The neutral gas

velocity was set to be a horizontal vortex with

![]() ,

where U is a scalar potential so

as to keep

,

where U is a scalar potential so

as to keep

![]() to inhibit the piling up

of the plasma and magnetic field. The plasma is dragged behind the

neutral gas through collisional interaction with the gas. The

collision frequency

to inhibit the piling up

of the plasma and magnetic field. The plasma is dragged behind the

neutral gas through collisional interaction with the gas. The

collision frequency ![]() is height dependent, attaining its maximum

at the bottom and decreasing exponentially with height. Therefore

the plasma motion is coupled with the neutral gas in the photosphere

and chromosphere, while it is decoupled from the neutral gas motion

in the corona. Hence the whole evolution of an initially relaxed

equilibrium state is due to plasma flows induced by the moving

photospheric neutral gas.

is height dependent, attaining its maximum

at the bottom and decreasing exponentially with height. Therefore

the plasma motion is coupled with the neutral gas in the photosphere

and chromosphere, while it is decoupled from the neutral gas motion

in the corona. Hence the whole evolution of an initially relaxed

equilibrium state is due to plasma flows induced by the moving

photospheric neutral gas.

The complete set of Eqs. ((1)-(7)) was numerically

solved in a 3-D cartesian box with finite-difference discretization

methods. The grid was chosen to be equidistant in the x and y directions, both with

128 grid points and

![]() .

It is non-equidistant in the z direction (with 64 grid points): the resolution decreases with

height. The grid size is

.

It is non-equidistant in the z direction (with 64 grid points): the resolution decreases with

height. The grid size is

![]() at the bottom and

stretched to

at the bottom and

stretched to

![]() at the top. Equations (1) to (4) were advanced

in time with a second-order accurate leapfrog scheme

(Potter 1973), because it has a very low numerical

dissipation. A Lax scheme was used in the first and last step.

at the top. Equations (1) to (4) were advanced

in time with a second-order accurate leapfrog scheme

(Potter 1973), because it has a very low numerical

dissipation. A Lax scheme was used in the first and last step.

![\begin{figure}

{\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{13321fg2.eps} }

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13321-09/Timg37.png)

|

Figure 2: Magnetic field configuration with a null in the center of the box. The upper-left figure shows the 3-D view of the whole simulation box extending from the photosphere to the corona. The upper-right figure is a x-y face-on view of the null at z=14.17. The bottom-left/bottom-right figure is the x-z/y-z cut through the center of the y-axis/x-axis, where the null is located. The black lines are the global magnetic field lines. The blue lines are the magnetic field lines leaving from the weak field region (B<2), while the red lines are the magnetic flied lines coming into the region. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

The location of the minimum numerical magnetic field slightly shifts

in height from (46.4, 46.4, 14.6) to (46.4, 46.4, 14.2) after the

simulation of 1.6 Alfvén times and its value becomes

(

![]() ). The weak field region (

). The weak field region (

![]() )

in

Fig. 2 extends between

x: 45.0-47.1,

y:

45.0-47.1, and

z: 12.0-20.5. We calculated the Jacobian matrix

)

in

Fig. 2 extends between

x: 45.0-47.1,

y:

45.0-47.1, and

z: 12.0-20.5. We calculated the Jacobian matrix

![]() to evaluate the structure

(Lau & Finn 1990) around the null. The eigenvalues of the matrix

at the null point are about

(2.1, -1.7, -0.3), following the

category of a negative null. The first positive eigenvalue defines

the spine, while the last negative ones indicate a fan surface. The

eigenvector of the matrix gives the direction of a corresponding

spine or fan plane: the spine path is in the direction of

0.18,

-0.98, 0.03 (followed by the blue field lines in

Fig. 4); the fan surface is a

plane defined by two vectors

(-0.98, -0.18, -0.01) and (0,0,1),

i.e. a vertical plane crossing the center of the red field lines in

the figure. Since the second eigenvalue (-0.3) for the fan plane is

much smaller compared to the first (-1.7), the field lines tend to

follow the direction of

-0.98, -0.18, -0.01 (red lines in the

horizontal direction) rather than the vertical direction 0,0,1(Restante et al. 2009). Actually, if the last eigenvalue

vanishes, the 3D null point simply equals 2D X-point where no field

lines extend in the vertical direction. These structures can also be

seen in Figs. 6 and 7, where magnetic fields are

shown as black lines.

to evaluate the structure

(Lau & Finn 1990) around the null. The eigenvalues of the matrix

at the null point are about

(2.1, -1.7, -0.3), following the

category of a negative null. The first positive eigenvalue defines

the spine, while the last negative ones indicate a fan surface. The

eigenvector of the matrix gives the direction of a corresponding

spine or fan plane: the spine path is in the direction of

0.18,

-0.98, 0.03 (followed by the blue field lines in

Fig. 4); the fan surface is a

plane defined by two vectors

(-0.98, -0.18, -0.01) and (0,0,1),

i.e. a vertical plane crossing the center of the red field lines in

the figure. Since the second eigenvalue (-0.3) for the fan plane is

much smaller compared to the first (-1.7), the field lines tend to

follow the direction of

-0.98, -0.18, -0.01 (red lines in the

horizontal direction) rather than the vertical direction 0,0,1(Restante et al. 2009). Actually, if the last eigenvalue

vanishes, the 3D null point simply equals 2D X-point where no field

lines extend in the vertical direction. These structures can also be

seen in Figs. 6 and 7, where magnetic fields are

shown as black lines.

Driven by the horizontal photospheric motion, the plasma in the

whole simulation box evolves. It reaches a state with an average

bulk velocity of 0.42 u0 after the simulation (top image in

Fig. 3). The global configuration and

topology of the magnetic fields do not show any obvious change.

Figure 2 shows the evolved global

configuration of the magnetic fields with a magnetic null in the

corona. However, convective electric fields arise in the whole box

(bottom image in Fig. 3) due to the

plasma motion across the magnetic field (top image in

Fig. 3). Since both the magnetic field

and plasma flows are stronger in the chromosphere, the convective

electric field

![]() develops more

strongly in the lower part of the box. The convective electric field

has an average value of 4.08 E0 in the whole box, and its maximum

value is 3333 E0 at (50.03, 68.15, 2.10) in the chromosphere.

Near the null, however, the convective electric field is only

0.0036 E0 (bottom image of

Fig. 4), because the magnetic

field is minimum (0.05 B0) and the plasma bulk velocity is

0.233 u0. Figure 4 shows the

resulting plasma flow lines and the convective electric fields (as

black lines) close to the null.

develops more

strongly in the lower part of the box. The convective electric field

has an average value of 4.08 E0 in the whole box, and its maximum

value is 3333 E0 at (50.03, 68.15, 2.10) in the chromosphere.

Near the null, however, the convective electric field is only

0.0036 E0 (bottom image of

Fig. 4), because the magnetic

field is minimum (0.05 B0) and the plasma bulk velocity is

0.233 u0. Figure 4 shows the

resulting plasma flow lines and the convective electric fields (as

black lines) close to the null.

![\begin{figure}

\par {\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{13321fg3.eps} }

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13321-09/Timg43.png)

|

Figure 3:

Plasma velocity flow lines ( top) and corresponding

convective electric fields ( bottom). The red lines represent

velocity flow (electric field) lines with positive (upward directed)

uz (Ez). The blue lines indicate negative (downward directed)

uz (Ez). The diagonal cross-section plane in the top image

depicts the grey-coded normalized value of uz. The cross-section

plane in the bottom image shows the grey-scale

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

{\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{13321fg4.eps} }

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13321-09/Timg44.png)

|

Figure 4:

Plasma velocity flow lines ( top) and the corresponding

convective electric fields ( bottom) near the null. The red lines

represent the magnetic fields coming into the weak field region

(B<2), while the blue ones are field lines leaving the region. The

black lines indicatethe plasma velocity flow lines ( top) and

convective electric field lines ( bottom), with uz<0 and Ez<0.

The horizontal layers cutting through the null show the strength of

the normalized plasma velocity u ( top) and the value of

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

where

The simulated resistive electric field has its maximum value of

0.08 E0 in the transition region at (48.6, 69.6, 4.6). Around the

null, no anomalous resistive electric field is switched on by the

end of our simulation at

![]() .

We therefore considered

only the perpendicular convective electric field and investigated

the acceleration ability of the convective electric field around the

3-D null point.

.

We therefore considered

only the perpendicular convective electric field and investigated

the acceleration ability of the convective electric field around the

3-D null point.

3 How can a convective electric field accelerate particles?

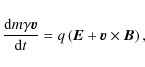

The basic relativistic equation of motion of an individual charged

particle in an electromagnetic field includes the acceleration by

the electric field, ![]() ,

and the Lorentz force exerted by the

magnetic field,

,

and the Lorentz force exerted by the

magnetic field, ![]() :

:

Here,

where

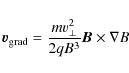

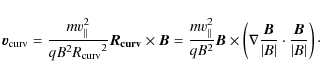

The possible way to accelerate particles in convective electric fields is therefore either to break down their magnetization, or to let them drift in the direction of the electric field due to the gradient and curvature force. De-magnetized particles can be directly accelerated by the electric field. Magnetized particles can only gain energy while undergoing a strong drift motion in the direction of the electric field.

In a non-uniform magnetic field, the magnetic-field gradient force

![]() and the

curvature force

and the

curvature force

![]() cause a drift motion perpendicular to both the magnetic

field and the force direction. If there is a component of the drift

velocity in the direction of the electric field, the particles could

either gain or lose energy in the electric field according to Eq. (11). The gradient drift and the curvature

drift velocities are

cause a drift motion perpendicular to both the magnetic

field and the force direction. If there is a component of the drift

velocity in the direction of the electric field, the particles could

either gain or lose energy in the electric field according to Eq. (11). The gradient drift and the curvature

drift velocities are

These drift velocities vary inversely proportional to the magnitude of the magnetic field. Therefore particle drifts are maximum where the magnetic field is minimum and the gradients and curvatures are strong. A null point provides a highly probable location for these effects. For

Moreover, the electric drift

![]() may also cause particle

acceleration (e.g, Northrop 1963; Vekstein & Browning 1997). When the particles move away from the null

point, the continuous change of the magnetic and electric field will

lead to the non-uniformity of the electric drift speed. As a result,

particles will not follow the drift stream lines, and the

acceleration is associated with the changing electric drift

velocity.

may also cause particle

acceleration (e.g, Northrop 1963; Vekstein & Browning 1997). When the particles move away from the null

point, the continuous change of the magnetic and electric field will

lead to the non-uniformity of the electric drift speed. As a result,

particles will not follow the drift stream lines, and the

acceleration is associated with the changing electric drift

velocity.

![\begin{figure}

{\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{13321fg5.eps} }\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13321-09/Timg80.png)

|

Figure 5: Gradient ( top) and curvature ( bottom) drift lines (blue lines) around the null (magnetic field lines are shown as black lines). The left/middle/right column shows the projection of the flow lines in the x-y/x-z/y-z 2-D plane cutting through the null. The magnitude of the drift velocity in logarithmic-scale is shown in color with a brighter color indicating a higher drift speed. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

{\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{13321fg6.eps} }

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13321-09/Timg81.png)

|

Figure 6: Lengths of magnetic gradient scale ( top) and curvature scale ( bottom) around the null (magnetic fields are shown in black lines). The left/middle/right plot shows the x-y / x-z / y-zplane cutting through the null. The magnitude of the scale lengths in the logarithmic-scale is color-coded with the darker color indicating a lower value. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

{\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{13321fg7.eps} }\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13321-09/Timg82.png)

|

Figure 7: Ratios of the Larmor radii to the the magnetic gradient scale lengths for a 200 eV proton ( top) and a 200 eV electron ( bottom) near the null (magnetic fields are shown in black lines). The left/middle/right column shows x-y / x-z / y-z 2-D cuts through the null. The magnitude of the ratios is shown in gray scale with a brighter color indicating a higher value. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

In the course of this adiabatic drift-acceleration it may happen

that the particle gyration radii (

Li=mv/|q|B) become comparable

to the scale lengths of the magnetic non-uniformity. In this case

particles lose their magnetization and adiabatic state and can be

directly accelerated in the perpendicular electric field

(e.g. Büchner 1986; Büchner & Zelenyi 1989). A null point should

be a prime candidate location for both drift and non-adiabatic

acceleration. To verify this hypothesis quantitatively, we

calculated the magnetic gradient and curvature scale according to

![]() and

and

![]() .

Figure 6 displays the gradient and

curvature scale lengths around the null. The average values of

.

Figure 6 displays the gradient and

curvature scale lengths around the null. The average values of

![]() and

and

![]() around the null (where B < 1) are

0.79 L0 and 5.18 L0 respectively. The minimum

around the null (where B < 1) are

0.79 L0 and 5.18 L0 respectively. The minimum

![]() and

and

![]() in the whole MHD-simulation box are located near the null

point, which is

0.0176 L0 and

0.1516 L0 i.e. 8.8 km and

76 km. Notice that the calculation of the gradient and curvature

scales is limited by the coarse grid sizes of the MHD box. In

coronal fields, one should expect smaller non-uniform scales. On the

other hand, the Larmor radius of a gyrating particle (

in the whole MHD-simulation box are located near the null

point, which is

0.0176 L0 and

0.1516 L0 i.e. 8.8 km and

76 km. Notice that the calculation of the gradient and curvature

scales is limited by the coarse grid sizes of the MHD box. In

coronal fields, one should expect smaller non-uniform scales. On the

other hand, the Larmor radius of a gyrating particle (![]() v/B) is

enlarged near the null by the weak magnetic field. Assuming a

typical coronal particle energy of

v/B) is

enlarged near the null by the weak magnetic field. Assuming a

typical coronal particle energy of

![]() ,

one obtains

,

one obtains ![]() about

about

![]() and

and ![]() about

about

![]() for

for

![]() .

At

the location where

.

At

the location where

![]() ,

the Larmor radii of protons

and electrons are

,

the Larmor radii of protons

and electrons are

![]() and

and

![]() respectively.

The resulting ratios of the Larmor radii to the magnetic gradient

scale lengths of both a

respectively.

The resulting ratios of the Larmor radii to the magnetic gradient

scale lengths of both a

![]() proton (top) and a

proton (top) and a

![]() electron (bottom) are shown in

Fig. 7. As one can see in the

figure, near the null point Larmor radii and magnetic gradient

scales are comparable for protons, while for electrons this ratio is

much smaller. Therefore we can expect that protons will undergo

stronger drifts and are more likely to be non-adiabatically

accelerated than electrons. Note that once particle energies are

increased, the Larmor radii will also be enlarged and the chance of

de-magnetization and consequent direct acceleration will be

significantly enhanced. To investigate how particles become

accelerated near the null, we used a test-particle approach which we

describe in next section.

electron (bottom) are shown in

Fig. 7. As one can see in the

figure, near the null point Larmor radii and magnetic gradient

scales are comparable for protons, while for electrons this ratio is

much smaller. Therefore we can expect that protons will undergo

stronger drifts and are more likely to be non-adiabatically

accelerated than electrons. Note that once particle energies are

increased, the Larmor radii will also be enlarged and the chance of

de-magnetization and consequent direct acceleration will be

significantly enhanced. To investigate how particles become

accelerated near the null, we used a test-particle approach which we

describe in next section.

4 Simulation of particle acceleration near a 3-D null

We assumed that the accelerated particles exert negligible feedback forces on the background coronal electromagnetic fields. Hence we could use a full-orbit relativistic test particle approach, in which the protons or electrons individually explore in the prescribed electromagnetic field as described and calculated in Sect. 2. We took a fixed snapshot of the macroscopic fields and freezed them during the evaluation of the particle trajectories.

We calculated the particle motion by numerically solving the relativistic momentum Eq. (9) together with (10). In order to find out whether in ideal MHD the convective electric field as theoretically described in Sect. 3 around the null is able to accelerate particles, we considered only the perpendicular convective electric field and neglected any parallel electric field. Of course, to obtain the field values at the particle position, one has to interpolate between the much more distant grid points of the MHD simulation. We used the eight neighbouring grid points nearest to a particle's position and applied a 3-D linear interpolation scheme to get the magnetic field and plasma velocities, which allowed us to determine the local convective electric field at the actual particle position. With a Runge-Kutta-Fehlberg fourth-fifth-order method with an adaptive time step, we integrated the positions and velocities of both protons and electrons in time.

We focused on the mechanism and process of particle acceleration by

the null point, i.e. the highest energy a proton or electron could

most probably gain from the convective electric field. The final

acceleration spectrum, which depends on the initial spatial and

velocity distributions, is not taken into account. Hence the initial

launch point of particles was taken to be the point with the minimum

magnetic field, where the particles are most likely to be

accelerated. The initial velocities were shell-distributed: all the

particles shared the same speed, but started in random directions.

For the initial speed we first took the speed for particles with a

kinetic energy of 200 eV (corresponding to the most probable speed

at a temperature of 2.32 MK), which yields

![]() m/s

for electrons and

m/s

for electrons and

![]() m/s for protons. In

Sect. 4.6, we also investigate the influence of

higher initial energies on the acceleration process.

m/s for protons. In

Sect. 4.6, we also investigate the influence of

higher initial energies on the acceleration process.

4.1 Particle acceleration under different plasma flow conditions

Table 1: Calculation of particle kinetic energies (in keV) under different electric fields.

Since there is no direct observation of the magnitude of coronal

convection and corresponding electric fields, we derived these

quantities by the MHD simulation. The MHD equations were solved for

dimensionless quantities so that we could rescale the dimensional

values of the convection plasma flow

![]() and the electric field

and the electric field

![]() by changing the normalization value u0. The rescaling

was not applied to B0 so that the magnetic field strength was

unaltered in the vicinity of the magnetic null point. Rescaling the

plasma flow velocity corresponds to a change of the magnitude of the

driving motions in the photosphere (at the bottom of the simulation

box).

by changing the normalization value u0. The rescaling

was not applied to B0 so that the magnetic field strength was

unaltered in the vicinity of the magnetic null point. Rescaling the

plasma flow velocity corresponds to a change of the magnitude of the

driving motions in the photosphere (at the bottom of the simulation

box).

Table 1 shows the energies acquired by a certain

number of particles (1000 particles in each case) with the initial

energy

![]() and the location

and the location

![]() for different magnitudes of the

plasma flow velocities and their corresponding different coronal

convective electric fields. ``Acc.time'' represents the acceleration

time which was defined so that the minimum energy (Min Ek),

average energy (Aver Ek) and maximum energy (Max Ek) of a

group of particles (1000 particles in each case) did not show any

obvious changes after this initial acceleration phase. The average

plasma flow velocities imposed at the bottom,

for different magnitudes of the

plasma flow velocities and their corresponding different coronal

convective electric fields. ``Acc.time'' represents the acceleration

time which was defined so that the minimum energy (Min Ek),

average energy (Aver Ek) and maximum energy (Max Ek) of a

group of particles (1000 particles in each case) did not show any

obvious changes after this initial acceleration phase. The average

plasma flow velocities imposed at the bottom,

![]() ,

increased from Case 1 to Case 4, being 0.69, 6.9, 69, and 690

,

increased from Case 1 to Case 4, being 0.69, 6.9, 69, and 690

![]() respectively. The plasma flow velocities at the

reference null,

respectively. The plasma flow velocities at the

reference null,

![]() ,

are 11.64, 116.4, 1164, and 11640

,

are 11.64, 116.4, 1164, and 11640

![]() from Case 1 to 4. The corresponding convection electric

fields

from Case 1 to 4. The corresponding convection electric

fields

![]() are enhanced from Case 1 to 4: being 0.0181,

0.181, 1.81, and 18.1

are enhanced from Case 1 to 4: being 0.0181,

0.181, 1.81, and 18.1 ![]() respectively.

respectively.

![]() (being 7.52, 75.2, 752, 7520

(being 7.52, 75.2, 752, 7520

![]() from Case 1 to 4) and

from Case 1 to 4) and

![]() (being 1.15, 11.5, 115, 1150

(being 1.15, 11.5, 115, 1150 ![]() from Case 1

to 4) are the average plasma velocities and convective electric

fields around the null area (

from Case 1

to 4) are the average plasma velocities and convective electric

fields around the null area (

![]() ).

).

One thousand protons were launched near the null for each case of

plasma conditions. In Case 1, the plasma flow (convection) velocity

at the reference null point was

![]() and the average

plasma velocity inside the area where

and the average

plasma velocity inside the area where

![]() was

was

![]() .

The corresponding convective electric fields were

.

The corresponding convective electric fields were

![]() at the point and

at the point and

![]() on average. After

on average. After

![]() of motion in the electromagnetic fields, the protons'

energies were only slightly enhanced. In Case 2, with stronger

driving at the bottom, both the plasma velocity and electric field

were ten times higher and more extended than in Case 1. Protons were

moderately accelerated within

of motion in the electromagnetic fields, the protons'

energies were only slightly enhanced. In Case 2, with stronger

driving at the bottom, both the plasma velocity and electric field

were ten times higher and more extended than in Case 1. Protons were

moderately accelerated within

![]() ,

and the maximum energy

nearly reached a value of

,

and the maximum energy

nearly reached a value of

![]() .

In Case 3, the bottom

driving plasma velocity was on average

.

In Case 3, the bottom

driving plasma velocity was on average

![]() and the plasma

velocity at the reference null point was

and the plasma

velocity at the reference null point was

![]() ,

a number

that is reasonable for the magnetically active coronal environment.

Correspondingly, the convective electric field was

,

a number

that is reasonable for the magnetically active coronal environment.

Correspondingly, the convective electric field was

![]() at the grid. It is shown that protons are efficiently accelerated up

to

at the grid. It is shown that protons are efficiently accelerated up

to

![]() within

within

![]() .

Case 4 corresponds to the

situation of very strong driving (driving velocity being

.

Case 4 corresponds to the

situation of very strong driving (driving velocity being

![]() on average), which can be assumed for a powerful

flare explosion. The resulting convective electric field was

on average), which can be assumed for a powerful

flare explosion. The resulting convective electric field was

![]() at the reference null point and

at the reference null point and

![]() on

average inside the area (

on

average inside the area (

![]() ). This situation allowed a

proton to be accelerated to an energy of more than

). This situation allowed a

proton to be accelerated to an energy of more than

![]() .

.

For electrons, however, no acceleration was achieved in Case 1 and

Case 2. In Case 3, i.e. in active regions, their kinetic energy was

slightly enhanced to 300 eV. Case 4 shows that electrons near

coronal nulls of explosive flare conditions may be accelerated to

energies close to

![]() .

Electron acceleration by a

perpendicular convective electric field is less efficient, because

their Larmor radii are much smaller than the non-uniformity scale of

the magnetic field (bottom images in

Fig. 7), and therefore it is very

difficult to de-magnetize electrons. Their efficient acceleration

may require a parallel electric field, which can accelerate

particles adiabatically along the magnetic field lines

(Litvinenko 1996). However, the inclusion of parallel

electric fields necessitates to consider kinetic processes that

enable their formation and determine their spatial scale.

.

Electron acceleration by a

perpendicular convective electric field is less efficient, because

their Larmor radii are much smaller than the non-uniformity scale of

the magnetic field (bottom images in

Fig. 7), and therefore it is very

difficult to de-magnetize electrons. Their efficient acceleration

may require a parallel electric field, which can accelerate

particles adiabatically along the magnetic field lines

(Litvinenko 1996). However, the inclusion of parallel

electric fields necessitates to consider kinetic processes that

enable their formation and determine their spatial scale.

4.2 Single proton orbit study for Case 3

![\begin{figure}

{\includegraphics[width=7.8cm,clip]{13321fg8.eps} }\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13321-09/Timg125.png)

|

Figure 8: Orbit of a single proton during 0.1 s of acceleration (Case 3, active region). Top image: 3-D view of the orbit. Bottom images: x-z ( left) and y-z ( right) projection views. The square-asterisk dotted shows the starting point of the particle, while other asterisks show the locations after each time step of 0.02 s. The gray scale represents the strength of the magnetic field, which increases while the particle moves out of the null. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

{\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{13321fg9.eps} }

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13321-09/Timg126.png)

|

Figure 9: Acceleration of a single proton during 0.1 s (Case 3, active region). Top panel: the green solid line shows the energy-gain; the blue dotted and dashdotted lines represent the angle of the proton velocity with respect to the magnetic and electric field. The red/gray high lighted regions give examples of the acceleration/deceleration process, whereby the energy increases/decreases and the angle between velocity and electric field is narrower/wider than 90 degrees. The middle image shows the local magnitude of the magnetic field (G) and electric field (V/m) on the way of the proton orbit. The bottom image shows the logarithmic value of the curvature scale, gradient scale, Larmor radius and the ratio of the Larmor radius to the gradient scale. All length values are in meters. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

{\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{13321fg10.eps} }

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13321-09/Timg127.png)

|

Figure 10: Kinetic energy ( top) and velocity ( bottom) evolutions in both parallel (dotted lines) and perpendicular (dash-dotted lines) directions of a single proton during 0.1 s are shown under Case 3 conditions. Solid lines are showing the total kinetic energy (top) and velocity ( bottom). Also the electric drift velocity is shown in dashed line ( bottom). |

| Open with DEXTER | |

In order to understand acceleration near the null, we considered the evolution of orbits, kinetic energies, pitch angles and Larmor radii for a single proton in Case 3 (active region).

Figure 8 shows a typical proton orbit during the first 0.1 s of acceleration. The spatial distance between two neighboring asterisks, marking 0.02 s time intervals, is increasing. This indicates that the proton is moving faster and faster. The gray scale shows the magnitude of the magnetic field, which increases away from the null. Figure 9 shows the evolution of the particle's kinetic energy, the velocity-magnetic field (V-B) pitch angle, the velocity-electric field (V-E) angle, the strength of magnetic and electric fields, and the logarithmic value of curvature scale, gradient scale, Larmor radius and the ratio of Larmor radius to gradient scale. The red high lighted region in the top image indicates the interval of major acceleration, during which the kinetic energy is increasing and the V-E angle for several gyro-periods remains smaller than 90 degrees. This means that the proton is de-magnetized and moves non-adiabatically in the direction of the electric field. The proton is therefore efficiently accelerated during this process. The gray high-lighted region, on the other hand, corresponds to an example of a deceleration moment due to the gyro-motion. The V-E angle stays wider than 90 degrees, meaning that the proton moves against the direction of the electric field.

During the initial 0.07 s, the average Larmor radius (red line in bottom image of Fig. 9) was about 2 km, and the proton underwent strong drifts with a transition to non-adiabatic motion (from 0.04 s to 0.06 s) after initial acceleration. As the proton was moving away from the null, the magnetic field increased (middle image in Fig. 9) and the particle started to be magnetized with a regular gyration and smaller gyro-radii. The bottom panel of Fig. 9 shows that both curvature and gradient scale lengths were increasing, while the Larmor radius decreased because the proton moved towards the stronger magnetic field. When the ratio of Larmor radius to gradient scale dropped below 10-1 and the main acceleration phase was finished, the proton became re-magnetized. Notice that magnetic fields from a MHD simulation would significantly smooth small scale non-uniform structures, a process which is very important for demagnetization. This non-adiabatic acceleration process would be more effective if microscopic turbulence of the magnetic field were considered.

Figure 10 separately shows the parallel and perpendicular components of both the kinetic energy and velocity of the particle. There are three different phases of acceleration: (a) perpendicular acceleration due to (mostly gradient) drift within the first 0.04 s, (b) parallel acceleration due to non-adiabatic motion from 0.04 s to 0.06 s, and (c) parallel acceleration due to (mainly curvature) drift from 0.06 s to 0.08 s. We show in Fig. 10 that the parallel kinetic energy stayed relatively small during the initial 0.04 s, and only the perpendicular energy was enhanced from less than 0.2 keV to about 5 keV. This is because the convection electric field is perpendicular to the magnetic field, and thus the perpendicular energy can easily be enhanced. The gradient drift velocity (Eq. (12)) was hence enlarged and helped the drift acceleration as a feedback. This initial acceleration prepared the particles for the subsequent non-adiabatic acceleration phase.

From 0.04 s to 0.06 s, the proton did not complete full gyrations (de-magnetized) and therefore could be continuously accelerated in the electric field (also shown by the small V-E angle in Fig. 9). The perpendicular energy almost stopped growing, while the parallel energy increased a lot (up to 9 keV at 0.06 s). This non-adiabatic process transfered the perpendicular energy immediately into parallel energy. When the proton was re-magnetized at 0.06 s, this high parallel energy enhanced the curvature drift (Eq. (13)), causing further acceleration in the parallel direction (from 9 keV at 0.06 s to 18 keV at 0.08 s), until the proton stopped its perpendicular drift at 0.08 s. The parallel energy stayed around 20 keV, and the perpendicular energy oscillated around 5 keV. Hence the total energy was about 25 keV.

After 0.08 s, the proton pitch (V-B) angle was approaching 180 degrees (see the top panel of Fig. 9).

This indicates that the proton could escape along (albeit against

the direction of) the magnetic field downward to the photosphere.

The V-E angle stayed around 90 degrees in the end. Hence the

acceleration was finished. The final particle velocity was the sum

of three types of motion: parallel velocity, perpendicular drift

velocity and perpendicular gyration velocity. The last part was

apparent as an oscillation (especially after 0.07 s when the proton

is magnetized) of the perpendicular velocity and energy

(Fig. 10) as well as of the V-B and V-Eangle (top panel of Fig. 9). After

averaging it over the gyration period, the remaining perpendicular

velocity is the drift velocity, which is mostly due to the

![]() drift (

drift (

![]() )

in the end. As one can see in the bottom frame of

Fig. 10, the electric drift velocity (dashed

line) approached the average of the perpendicular velocity

(dash-dotted line) after 0.08 s and about 600

)

in the end. As one can see in the bottom frame of

Fig. 10, the electric drift velocity (dashed

line) approached the average of the perpendicular velocity

(dash-dotted line) after 0.08 s and about 600

![]() at

0.1 s. This electric drift velocity is consistent with the

perpendicular component of the plasma velocity as obtained from the

MHD simulation i.e.

at

0.1 s. This electric drift velocity is consistent with the

perpendicular component of the plasma velocity as obtained from the

MHD simulation i.e.

![]() .

.

![\begin{figure}

{\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{13321fg11.eps} }

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13321-09/Timg131.png)

|

Figure 11: Energy evolution of a single proton during 0.05 s under Case 4 conditions. In the top image, the green solid line shows the energy-gaining process. The blue dotted and dash-dotted lines show the V-B angle and V-E angle. The red/gray high-lighted regions give examples of the acceleration/deceleration process, whereby the energy is increasing/decreasing and the V-E angle is narrower/wider than 90 degrees. The middle image shows the local magnitude of the magnetic field (G) and electric field (V/m) on the way of the proton orbit. The bottom image shows the logarithmic value of the curvature scale, gradient scale, Larmor radius and the ratio of the Larmor radius to the gradient scale. All length values are in meters. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

4.3 Single proton orbit study for Case 4

In order to understand how protons could be accelerated up to 2 MeV during flares (Case 4 conditions - strong convection which could only happen during big flare explosions), we again study the acceleration process of a typical single proton. Figure 11 shows the evolutions of the V-B and V-E angle, local magnetic and electric field strength, gradient and curvature scale and Larmor radius. As in Case 3, the red high-lighted region in the top image indicates the main non-adiabatic acceleration phase, during which the proton is continuously accelerated. The gray high lighted region indicates an example of deceleration phase due to gyro-rotation. Figure 12 represents the evolutions of the parallel and perpendicular energies and velocities separately.

It is clear that the acceleration process is much more efficient than that of Case 3, because the electric field is much stronger and the proton is less magnetized. The Larmor radius of the proton during the first 0.02 s (about 6 km) is very close to the gradient scale (about 10 km), as one can see at the bottom panel of Fig. 11. As in Case 3, Fig. 12 shows that there are also three different phases of acceleration in Case 4: (a) perpendicular acceleration within the first 0.01 s, during which mainly the perpendicular energy is enhanced (from less than 200 eV to nearly 100 keV at 0.01 s), (b) parallel acceleration due to non-adiabatic motion from 0.01 s to 0.021 s, whereby the parallel energy increases dramatically (from about 20 keV at 0.01 s to 1200 keV at 0.021 s), (c) parallel acceleration due to (mainly curvature) drift from 0.021 s to 0.025 s, whereby the parallel energy keeps increasing albeit at a lower speed (to about 1850 keV at 0.025 s) when the proton is re-magnetized. The parallel energy is then slightly decreased after 0.025 s though, because the magnetic field increases while the proton moves out from the null (see middle panel of Fig. 11), and the parallel energy is transferred to perpendicular energy by the magnetic-mirror effect. Finally (at 0.05 s), the parallel energy reaches 1.3 MeV (see the dotted line in the top panel of Fig. 12). The perpendicular energy, which includes mainly the electric drift (see the red dashed line in the bottom panel of Fig. 12) is oscillating (due to the gyration) around 100 keV. The final high parallel velocity (i.e. small pitch angle: V-B is close to 180 degrees) lets the proton escape from the null along the field lines.

![\begin{figure}

{\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{13321fg12.eps} }\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13321-09/Timg132.png)

|

Figure 12: Under Case 4 conditions, the evolutions during 0.05 s of the kinetic energy ( top) and velocity ( bottom) in both parallel (dotted lines) and perpendicular (dash-dotted lines) directions of a single proton are shown. Solid lines represent the total kinetic energy ( top) and magnitude of velocity ( bottom). Also the electric drift velocity is shown as a dashed line ( bottom). |

| Open with DEXTER | |

4.4 Single electron orbit study for Case 3

![\begin{figure}

{\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{13321fg13.eps} }

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13321-09/Timg133.png)

|

Figure 13: Top panel shows the evolution of the kinetic energy and the pitch angles for a typical electron accelerated in active corona (Case 3 condition). The green thick line shows the kinetic energy and the blue dotted and dash-dotted lines represent the V-B and V-E angles respectively. The bottom panel shows the logarithmic value of curvature and gradient scales, electron Larmor radii and the ratio of Larmor radii to gradient scales. All lengths are given in meters. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

{\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{13321fg14.eps} }

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13321-09/Timg134.png)

|

Figure 14: In active regions (Case 3), the kinetic energy ( top panel) and velocity ( middle panel) evolutions in both parallel (dotted lines) and perpendicular (dash-dotted lines) directions of a single electron are shown. Solid lines represent the total kinetic energy ( top panel) and velocity ( middle panel). In the bottom panel, the electric drift velocity is shown as a dashed line and the gradient and curvature drift velocities are indicated as dotted and dash-dotted lines. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Similar to the single proton acceleration, we also investigated a single electron orbit (Figs. 13 and 14) for Case 3 (active region) conditions. We found that the electrons were not significantly accelerated. Their kinetic energies were only slightly enhanced due to drifts. Within about 0.006 s, the electron kinetic energy increased from 200 eV to just a little more than 300 eV. During the main acceleration (yellow highlighted region in the figure), the ratio of the Larmor radius to the gradient scale was about 10-3 (bottom panel of Fig. 13), and the V-E pitch angle indicated a strong parallel (particle velocity parallel to the electric field) component (top panel of Fig. 13).

However, the electron did not have a non-adiabatic phase of

acceleration due to its much smaller Larmor radius (![]()

![]() )

and much shorter gyro-period (

)

and much shorter gyro-period (![]() 10-7 s).

Another

reason for the absence of de-magnetization process could be that

MHD simulation drops the information of small scale non-uniformity

of

magnetic fields. The electrons considered here do not have an

awareness of the obvious change of the magnetic structure within

several gyration periods. In the real solar corona we expect them to

have a higher probability to experience non-adiabatic processes and

thus to become accelerated.

10-7 s).

Another

reason for the absence of de-magnetization process could be that

MHD simulation drops the information of small scale non-uniformity

of

magnetic fields. The electrons considered here do not have an

awareness of the obvious change of the magnetic structure within

several gyration periods. In the real solar corona we expect them to

have a higher probability to experience non-adiabatic processes and

thus to become accelerated.

Note that the electron shown in Fig. 14

initially carries mainly parallel energy. During the first 0.0035 s,

the perpendicular energy was increasing while the parallel energy

decreased. At about 0.0035 s, the parallel velocity changed its sign

from parallel to anti-parallel and the curvature drift velocity

reached zero according to Eq. (13) when

![]() .

The bottom panel in Fig. 14 displays

the velocities in logarithmic scale so that the zero value of the

curvature drift velocity cannot be shown. Till 0.008 s, the parallel

energy grew back while the perpendicular energy decreased. This is

similar to a magnetic-mirror effect, which means that when a

particle moves into a stronger magnetic field, its parallel energy

is transferred to its perpendicular energy until the parallel

velocity reaches zero. Then the parallel velocity changes its sign,

indicating that the electron is reflected and comes back towards the

weaker magnetic field, so that the perpendicular energy starts being

transferred to parallel energy. However, the magnetic moment

(

.

The bottom panel in Fig. 14 displays

the velocities in logarithmic scale so that the zero value of the

curvature drift velocity cannot be shown. Till 0.008 s, the parallel

energy grew back while the perpendicular energy decreased. This is

similar to a magnetic-mirror effect, which means that when a

particle moves into a stronger magnetic field, its parallel energy

is transferred to its perpendicular energy until the parallel

velocity reaches zero. Then the parallel velocity changes its sign,

indicating that the electron is reflected and comes back towards the

weaker magnetic field, so that the perpendicular energy starts being

transferred to parallel energy. However, the magnetic moment

(

![]() )

is not conserved during this process, because our 3-D

numerical magnetic field is very complex and the electric field is

included. A particle experiences not only gradient and curvature

drift, but also electric drift. These drift motions change the

gyro-center orbit along which the electric field could change the

kinetic energy as well as the magnetic moment.

)

is not conserved during this process, because our 3-D

numerical magnetic field is very complex and the electric field is

included. A particle experiences not only gradient and curvature

drift, but also electric drift. These drift motions change the

gyro-center orbit along which the electric field could change the

kinetic energy as well as the magnetic moment.

4.5 Single electron orbit study for Case 4

![\begin{figure}

{\includegraphics[width=7.3cm,clip]{13321fg15.eps} }

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13321-09/Timg138.png)

|

Figure 15: In solar flares (Case 4), the kinetic energy ( top panel) and velocity ( middle panel) evolutions in both parallel (dotted lines) and perpendicular (dash-dotted lines) directions of a typical electron are shown. Solid lines represent the total kinetic energy ( top panel) and velocity ( middle panel). In the bottom panel, the electric drift velocity is shown as a dashed line and the gradient and curvature drift velocities are indicated as dotted and dash-dotted lines. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Finally, electron acceleration in flares (Case 4) is shown in

Fig. 15. There are mainly two phases of

acceleration: perpendicular acceleration due to drift until

![]() and parallel acceleration also due to drift

till to

and parallel acceleration also due to drift

till to

![]() .

Because of the small electron

Larmor radii and the absence of microscopic magnetic structures,

there is no phase of non-adiabatic acceleration during which the

electron is de-magnetized and continuously accelerated.

Nevertheless, a net gain of energy due to the drift motion enhanced

the total electron energy from 0.2 keV to more than 2 keV.

The final high parallel velocity causes the electron to escape from

the null.

.

Because of the small electron

Larmor radii and the absence of microscopic magnetic structures,

there is no phase of non-adiabatic acceleration during which the

electron is de-magnetized and continuously accelerated.

Nevertheless, a net gain of energy due to the drift motion enhanced

the total electron energy from 0.2 keV to more than 2 keV.

The final high parallel velocity causes the electron to escape from

the null.

4.6 Influence of the initial energy

Table 2: Gradient and curvature drift velocities (in m/s), gradient and curvature scales (in m) and Larmor radii (in m) of both protons and electrons at the reference null.

We also investigated the influence of the initial particle energy on

the acceleration process. Higher initial energies with larger ![]() and

and

![]() reveal higher drift velocities (see

Eqs. (12) and (13)) as well as

larger Larmor radii. Hence particles can become more easily

de-magnetized (Table 2). With the assumption that

particles have already been pre-accelerated, we checked the

possibility of a secondary acceleration by the null under the plasma

flow conditions given in Case 3 (typical for active regions:

reveal higher drift velocities (see

Eqs. (12) and (13)) as well as

larger Larmor radii. Hence particles can become more easily

de-magnetized (Table 2). With the assumption that

particles have already been pre-accelerated, we checked the

possibility of a secondary acceleration by the null under the plasma

flow conditions given in Case 3 (typical for active regions:

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

,

![]() and

and

![]() .).

.).

Table 3 summarizes the changes in kinetic energy for both protons and electrons and for different initial speeds. As one can see, for higher initial energies the final maximum kinetic energy is enhanced due to higher drift velocities and the acceleration time is shorter. However, we notice that protons can even be decelerated (shown as Min Ek) for higher initial energies. This is because these protons have an initial velocity direction opposite to the electric field, and the high initial energy pushes them far along this direction so that they may lose kinetic energy according to Eq. (11). With higher initial energies, most protons have a chance to be accelerated more strongly, while a few become decelerated.

For electrons, on the other hand, an enhanced initial kinetic energy

does neither de-magnetize them nor switch on more efficient

non-adiabatic acceleration, because the initial electron Larmor

radii are only slightly enhanced from ![]()

![]() to

to ![]()

![]() (Table 2). These larger radii are still too

small compared to the magnetic non-uniformity scale, which is

obtained by macroscopic MHD simulations. Therefore secondary

acceleration of electrons by convection electric fields cannot be

expected at least in active regions (Case 3).

(Table 2). These larger radii are still too

small compared to the magnetic non-uniformity scale, which is

obtained by macroscopic MHD simulations. Therefore secondary

acceleration of electrons by convection electric fields cannot be

expected at least in active regions (Case 3).

Table 3:

Calculations of particle kinetic energies (in keV) under different

![]() (Vi) conditions.

(Vi) conditions.

5 Summary and discussion

Using numerical MHD simulations, we investigated the 3-D field structure and plasma flows around a coronal magnetic null point (Sect. 2). Based on the interpolated structure of magnetic fields around the null, we theoretically described how particles can be accelerated by a convective electric field perpendicular to the magnetic field due to the magnetic gradient and curvature drifts in Sect. 3. Finally, test particle calculations in Sect. 4 for both protons and electrons near the null provided a quantitative estimate of the particle acceleration process. Our main results can be summarized as follows.

- With extrapolated magnetic fields as the initial condition, our MHD simulation evolved to a state that plasma flow velocity and convective electric fields were generated through the whole simulation box. In the box center (with the height of solar corona region) the minimum magnetic field being less than 0.05 G indicated the immediate vicinity of a magnetic null point. When rescaled to active region conditions (Case 3), the plasma flow velocity was about 1000 km s-1 and the corresponding convective electric field was about 2 V/m at the null. Protons could be accelerated up to 30 keV in 0.1 s and electrons gained only small energies, i.e. from 0.2 keV to 0.3 keV.

- With higher plasma flow velocities and stronger convective electric

fields (

20 V/m near the null), protons could be accelerated

to energies up to 2 MeV in 0.03 s and electrons were accelerated to

about 3 keV in 0.005 s.

20 V/m near the null), protons could be accelerated

to energies up to 2 MeV in 0.03 s and electrons were accelerated to

about 3 keV in 0.005 s.

- The magnetic curvature radii (

)

near the

null exceeded the gradient scale lengths (

)

near the

null exceeded the gradient scale lengths (

).

Therefore gradient drifts favored the drifting acceleration more