| Issue |

A&A

Volume 513, April 2010

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A78 | |

| Number of page(s) | 10 | |

| Section | Extragalactic astronomy | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/200913320 | |

| Published online | 30 April 2010 | |

Direct detection of galaxy stellar halos: NGC 3957 as a test case![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

P. Jablonka1,2,3 - M. Tafelmeyer1 - F. Courbin1 - A. M. N. Ferguson4

1 - Laboratoire d'Astrophysique, Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale

de Lausanne (EPFL), Observatoire, 1290 Sauverny, Switzerland

2 -

Université de Genève, Observatoire, 1290 Sauverny, Switzerland

3 -

Observatoire de Paris, CNRS-UMR8111, Place Jules Janssen, 92190 Meudon, France

4 -

Institute for Astronomy, University of Edinburgh, Blackford Hill, Edinburgh, EH9 3HJ, UK

Received 18 September 2009 / Accepted 18 January 2010

Abstract

We present a direct detection of the stellar halo of the edge-on S0 galaxy NGC 3957, using ultra-deep VLT/VIMOS V and R images.

This is achieved with a sky subtraction strategy

based on infrared techniques. These observations allow us to reach

unprecedented high signal-to-noise ratios of up to 15 kpc away

from the galaxy center, rendering photon-noise negligible. The 1![]() detection limits are R = 30.6 mag/arcsec2 and V = 31.4 mag/arcsec2.

We conduct a thorough analysis of the possible sources of systematic

errors that could affect the data: flat-fielding, differences in

CCD responses, scaling of the sky background, the extended halo

itself, and PSF wings. We conclude that the V-R colour

of the NGC 3957 halo, calculated between 5 and 8 kpc

above the disc plane where the systematic errors are modest,

is consistent with an old and preferentially metal-poor normal

stellar population, like that revealed in nearby galaxy halos from

studies of their resolved stellar content. We do not find support for

the extremely red colours found in earlier studies of diffuse halo

emission, which we suggest might have been due to residual systematic

errors.

detection limits are R = 30.6 mag/arcsec2 and V = 31.4 mag/arcsec2.

We conduct a thorough analysis of the possible sources of systematic

errors that could affect the data: flat-fielding, differences in

CCD responses, scaling of the sky background, the extended halo

itself, and PSF wings. We conclude that the V-R colour

of the NGC 3957 halo, calculated between 5 and 8 kpc

above the disc plane where the systematic errors are modest,

is consistent with an old and preferentially metal-poor normal

stellar population, like that revealed in nearby galaxy halos from

studies of their resolved stellar content. We do not find support for

the extremely red colours found in earlier studies of diffuse halo

emission, which we suggest might have been due to residual systematic

errors.

Key words: galaxies: halos - galaxies: stellar content

1 Introduction

Galaxy stellar halos contain fundamental clues about the galaxy assembly. ![]() CDM models

predict stellar halos to be ubiquitous and dominated by old metal-poor

populations, characterized by significant substructures in the form of

tidal debris from accreted satellites (Bullock & Johnston 2005; Abadi et al. 2006; Font et al. 2006).

Conversely, in classical dissipative collapse models, halos are

expected to exhibit smooth age and metallicity gradients (e.g., Eggen et al. 1962).

Due to the extreme faintness of these envelopes, the value of

galactic stellar halos as key tests of galaxy formation theories has

however not yet been fully realized.

CDM models

predict stellar halos to be ubiquitous and dominated by old metal-poor

populations, characterized by significant substructures in the form of

tidal debris from accreted satellites (Bullock & Johnston 2005; Abadi et al. 2006; Font et al. 2006).

Conversely, in classical dissipative collapse models, halos are

expected to exhibit smooth age and metallicity gradients (e.g., Eggen et al. 1962).

Due to the extreme faintness of these envelopes, the value of

galactic stellar halos as key tests of galaxy formation theories has

however not yet been fully realized.

Since the middle of the nineties, our view of galaxy haloes has changed dramatically with the discovery of substructures around the Milky Way (e.g., Belokurov et al. 2007; Rocha-Pinto et al. 2003; Majewski et al. 1999; Juric et al. 2008; Grillmair 2006; Gilmore et al. 2002; Newberg et al. 2002; Ibata et al. 1994; Bell et al. 2008; Vivas & Zinn 2006). Similar signatures of tidal destruction of satellites by their massive hosts were found in the halo in M 31 (e.g., Richardson et al. 2008; Ferguson et al. 2002; Ibata et al. 2007; McConnachie et al. 2009; Tanaka et al. 2010; Ibata et al. 2001). Stellar streams were also detected around NGC 5907 and NGC 4013 (Martínez-Delgado et al. 2008,2009). It is nevertheless not yet totally clear how ubiquitous halos are and how often mergers intervene in their building-up.

Resolving individual stars is mainly limited to a small sample of galaxies within or close to the Local Group, with a few exceptions. Mouhcine et al. (2005a,b) resolved the stars near the red giant branch tip in the outskirts of eight nearby galaxies with the HST/WFPC2, although it remains unclear for some of their fields whether they sampled the galaxy outer discs or halos. Similarly, Ibata et al. (2009); Rejkuba et al. (2009); Mouhcine et al. (2007) analysed the extra-planar stellar populations in NGC 891 using three HST/ACS pointings. Recently Barker et al. (2009) conducted the first wide-field ground-based survey of the red giant branch population in the outskirts of M 81 using Suprime-Cam on the 8-m Subaru telescope. They detected a faint, extended structural component beyond the galaxy's bright optical disc sharing some similarities with the Milky Way's halo, but also exhibiting some important differences.

Searches for extended low surface brightness diffuse halo emission were carried out around several more distant external galaxies. The first detection was announced by Sackett et al. (1994) around the edge-on Sc galaxy NGC 5907 and later confirmed by Lequeux et al. (1996) and Lequeux et al. (1998). These two subsequent works additionally reported an unexpected reddening of the halo colours, increasing with the distance to the galaxy center. These results were contested by Zheng et al. (1999), who noticed that artifacts in the star-masking procedure could be responsible for the apparent reddening. Zibetti et al. (2004) used a stacking technique to combine the images of 1047 edge-on galaxies selected from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey. They detected the presence of a mean luminous halo, whose shape was clearly rounder than the disc. Their data suggested a correlation between the halo and galaxy luminosities. Surprisingly, their halo colours were redder than the reddest known elliptical galaxies. Zibetti & Ferguson (2004) reached similar photometric depths in a study of a single edge-on galaxy in the Hubble Ultra Deep Field, where they also found anomalously red colours, not reproduced by any conventional stellar populations model and getting redder with larger radii. de Jong (2008) however discussed how scattered galaxy light from extended point spread function tails could have been underestimated in these studies and thus lead to spurious detections.

The controversy over the existence and nature of stellar halos around external galaxies reflects that these types of observations are extremely challenging from a technical standpoint. Errors in flat-fielding and sky subtraction can easily mask or contort real signal. In order to overcome these limitations and to understand galactic halo properties, we designed a new strategy for galactic halo surface brightness profiles. It is based on two principles: i) we target a galaxy, which has an angular size that is much larger than the PSF extent and ii) we carry out very accurate sky subtraction, with a chopping technique similar to that used in near-IR imaging.

This paper is organized as follows: Sect. 2 presents our observational technique. Section 3 describes the data reduction procedure leading to ultra-deep sky-subtracted V and R images of NGC 3957. Section 4 presents the radial surface brightness profiles derived for the halo of NGC 3957. Section 5 discusses the most important possible sources of errors, focusing on the systematics. Section 6 interprets the V-R colour profile. Our conclusions are summarized in Sect. 7.

2 Observational strategy

We selected the early-type (S0) galaxy NGC 3957

(RA (J2000):11 54 01.5; Dec (J2000):

-19 34 08;

![]() = 1637 km s-1). NGC 3957 is seen nearly edge-on, its exact inclination angle (88

= 1637 km s-1). NGC 3957 is seen nearly edge-on, its exact inclination angle (88 ![]() 1 degrees) was measured by Pohlen et al. (2004). Its apparent size (3.1'

1 degrees) was measured by Pohlen et al. (2004). Its apparent size (3.1' ![]() 0.7')

is large enough to allow us to integrate flux over large regions when

determining the surface brightness profiles. At the same time,

it is small enough to fall entirely in a single VIMOS

CCD chip. Taking H0= 73 km s-1 Mpc-1,

at the distance of NGC 3957

(22.42 Mpc), 1 arcmin = 6.52 kpc. Another

important point is that the surroundings of NGC 3957, which were

used to determine the background level and shape, are devoid of any

bright objects.

0.7')

is large enough to allow us to integrate flux over large regions when

determining the surface brightness profiles. At the same time,

it is small enough to fall entirely in a single VIMOS

CCD chip. Taking H0= 73 km s-1 Mpc-1,

at the distance of NGC 3957

(22.42 Mpc), 1 arcmin = 6.52 kpc. Another

important point is that the surroundings of NGC 3957, which were

used to determine the background level and shape, are devoid of any

bright objects.

The choice of VIMOS was motivated by the opportunity to have a wide

field of view distributed over four different CCDs, of 2048 ![]() 2440 pixels each. With a resolution of 0.205'' per pixel, each CCD covers 7'

2440 pixels each. With a resolution of 0.205'' per pixel, each CCD covers 7' ![]() 8'. They are separated by a gap of 2' (see Fig. 2).

Unfortunately, the choice of a guide star satisfying VIMOS

specifications had the consequence that the guide probe fell on two of

the four CCDs. In all data, it covers more than 50% of either CCD3

or CCD4 (see CCD4 in Fig. 2), leaving those two chips unusable for our analysis.

8'. They are separated by a gap of 2' (see Fig. 2).

Unfortunately, the choice of a guide star satisfying VIMOS

specifications had the consequence that the guide probe fell on two of

the four CCDs. In all data, it covers more than 50% of either CCD3

or CCD4 (see CCD4 in Fig. 2), leaving those two chips unusable for our analysis.

Table 1: Journal of the observations.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=7.cm]{13320fig1.eps}\hspace*{0.7cm}

\includegraphics[width=7.cm]{13320fig2.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13320-09/Timg15.png)

|

Figure 1:

Left: dithering pattern for a set of 12 consecutive R-band

frames. The position (0, 0) indicates the initial position of NGC 3957 in one CCD. Right: dithering pattern for a set of six consecutive V-band exposures. Units are given in pixels. One pixel is 0.205

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=12cm,clip]{13320fig3.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13320-09/Timg16.png)

|

Figure 2: Geometry of the VIMOS field of view, composed of four CCDs, prior to sky subtraction. The galaxy was alternately put in CCD1 and in CCD2. The black feature in CCD3 and CCD4 is due to the guide star camera. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

We gathered R and V-band images, with total exposures of 22 500 s and 25 080 s (i.e., ![]() 6 and 7 h), respectively. Exposures were split into sequences of 190 s (R-band) and 450 s (V-band). The journal of the observations is presented in Table 1.

6 and 7 h), respectively. Exposures were split into sequences of 190 s (R-band) and 450 s (V-band). The journal of the observations is presented in Table 1.

The design of VIMOS allowed us to place NGC 3957 in one CCD while integrating the sky on the other one. This strategy offered two major advantages: (i) On one hand, the background level was estimated in a region located far away from the galaxy, thus avoiding possible contamination by faint, extended galaxy components. (ii) On the other hand, a 2D image of the sky was obtained under the exact same observing conditions as those of the galaxy.

Exposures were dithered following the patterns shown in Fig. 1. This allowed us not only to build master skies from empty field frames, nicely removing any bright object, but also to smear out any inhomogeneities in the background, increasing the flatness of the combined master skies.

As already mentioned, we used two different pointings. We will use the following terminology throughout: Pointing 1 corresponds to a set of exposures placing the galaxy in CCD1 and dithered following the patterns of Fig. 1. Pointing 2 has the same dithering pattern as Pointing 1, but the galaxy is now placed in CCD2. The exposures on the empty field in CCD1 (when the galaxy is in CCD2) and CCD2 (when the galaxy is in CCD1) are used to determine the background level and shape.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=12cm,clip]{13320fig4.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13320-09/Timg19.png)

|

Figure 3:

Example of the master sky in R ( left panel) and V ( right panel). The cuts are

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

3 Data reduction and sky subtraction

We only describe at length the steps differing from the classical

methodology for the reduction of images. These steps are critical to

reach a surface brightness level down to ![]() 30 mag/arcsec2.

30 mag/arcsec2.

Bias and flat-field corrections were done in a classical manner. Five

featureless biases were taken each night. Their mean ADU/pixel was

subtracted from all frames of the same night. When possible,

a series of five twilight flat fields were taken. For each of

these nights, we composed a master flat, corresponding to the average

of the five flats, with a 2-![]() clipping boundary,

clipping boundary, ![]() being

calculated with the gain and readout noise of the CCDs. Since

flat-fields were not taken each night, the same master flat was used

for several subsequent nights. We will discuss the possible

uncertainties arising from the flat-fielding in Sect. 5.1.

being

calculated with the gain and readout noise of the CCDs. Since

flat-fields were not taken each night, the same master flat was used

for several subsequent nights. We will discuss the possible

uncertainties arising from the flat-fielding in Sect. 5.1.

The most crucial step of the data reduction is the sky subtraction. One

master sky per night and per CCD was created as the average

(plus 2-![]() clipping boundary) of all dithered frames which did not contain the galaxy. For the R-band,

12 sky images per night and CCD were available.

Sigma clipping of the dithered images proved sufficient to remove

any bright star in the field. For the V-band, only six frames were available. Consequently,

we had to mask the bright stars before dithering to remove them

completely from the master sky frames. Figure 3 provides an example of a master sky for the two photometric bands. The cuts are chosen to be

clipping boundary) of all dithered frames which did not contain the galaxy. For the R-band,

12 sky images per night and CCD were available.

Sigma clipping of the dithered images proved sufficient to remove

any bright star in the field. For the V-band, only six frames were available. Consequently,

we had to mask the bright stars before dithering to remove them

completely from the master sky frames. Figure 3 provides an example of a master sky for the two photometric bands. The cuts are chosen to be ![]() 2% of the mean background level, which is three times the standard deviation. The large scale structures represent

2% of the mean background level, which is three times the standard deviation. The large scale structures represent ![]() 1% of the mean background level. They are of the order of

the uncertainties in flat-fielding, which are discussed in Sect. 5.1.

1% of the mean background level. They are of the order of

the uncertainties in flat-fielding, which are discussed in Sect. 5.1.

For the sake of clarity, we will now use the following nomenclature (see Fig. 4):

- MS1: master sky of CCD1, taken from the empty field frames of Pointing 2;

- SKY1

: individual CCD1 image of Pointing 2, which does not contain the galaxy and from which MS1 was created;

: individual CCD1 image of Pointing 2, which does not contain the galaxy and from which MS1 was created;

- GAL1

: individual CCD1 image of Pointing 1, which contains the galaxy;

: individual CCD1 image of Pointing 1, which contains the galaxy;

- MS2: master sky of CCD2 with Pointing 1. Analogous to MS1;

- SKY2

: individual CCD2 image of the empty field with Pointing 1. Analogous to SKY1

: individual CCD2 image of the empty field with Pointing 1. Analogous to SKY1 ;

;

- GAL2

: CCD2 individual galaxy image of CCD2 with Pointing 2. Analogous to GAL1

: CCD2 individual galaxy image of CCD2 with Pointing 2. Analogous to GAL1 .

.

We could not directly use the sky frames obtained at the same time as

the galaxy. Indeed, galaxy and background would then have been observed

with different CCDs. Small differences in the flat-fielding between

CCD1 and CCD2 could introduce artificial intensity gradients in the

final images. We needed to subtract skies of Pointing 2 from the

galaxy frames of Pointing 1 (and vice versa) obtained during

the same night. In practice, for each night we subtracted MS1 from

GAL1![]() and MS2 from GAL2

and MS2 from GAL2![]() ,

i.e. the master skies were observed at a slightly different time

than the galaxy, but with the same CCD. Although full dithering

patterns for both

pointings were completed in about one hour, the sky level was not

necessarily stable in this time interval. Actually, we measured a

variation in the mean background level of 10-15% from the

first to the last exposure for a given pointing sequence.

Two corrections were therefore necessary:

,

i.e. the master skies were observed at a slightly different time

than the galaxy, but with the same CCD. Although full dithering

patterns for both

pointings were completed in about one hour, the sky level was not

necessarily stable in this time interval. Actually, we measured a

variation in the mean background level of 10-15% from the

first to the last exposure for a given pointing sequence.

Two corrections were therefore necessary:

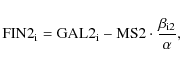

(1) For each GAL1![]() (GAL2

(GAL2![]() ),

MS1(MS2) had to be scaled to the level of the sky at the time at which

the galaxy was observed. We had direct access to this information via

the

contemporaneous exposures SKY2

),

MS1(MS2) had to be scaled to the level of the sky at the time at which

the galaxy was observed. We had direct access to this information via

the

contemporaneous exposures SKY2![]() (SKY1

(SKY1![]() ). To determine the scaling factor of each GAL1

). To determine the scaling factor of each GAL1![]() ,

MS1 was multiplied by the ratio

,

MS1 was multiplied by the ratio

where

for the scaling of the MS1 frames and by

Errors in ![]() have

opposite effects in CCD1 and CCD2 respectively, leading to a systematic

additive offset in the results when considering each of the two CCDs

separately. This can be used to

fine-tune

have

opposite effects in CCD1 and CCD2 respectively, leading to a systematic

additive offset in the results when considering each of the two CCDs

separately. This can be used to

fine-tune ![]() removing any systematic difference between CCD1 and CCD2.

removing any systematic difference between CCD1 and CCD2.

The complete sky subtraction is finally described by

| (3) |

and

|

(4) |

where FIN1

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{13320fig5.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13320-09/Timg29.png)

|

Figure 4:

Explanation of the scaling scheme, prior to the image

coaddition. The master sky of CCD1 (MS1) is taken as a reference. The i index refers to the individual exposures within a sequence. The factors

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

The 132 (50) R-band (V-band) background-subtracted

images were finally aligned and combined, and the final images are

calibrated in the Johnson-Cousins photometric system. One

CCD frame per night was calibrated in V and R with the standard stars observed during the same period. The final V and R combined images were then scaled to the level of their respective reference V and R frames.

Hence, the final frames were multiplied by the factor

flux(single)/flux(combined), where flux(single) and flux(combined) were

measured from several bright stars in the reference and combined

frames, respectively. These photometrically calibrated images were then

corrected for extinction using

AR=0.124 and

AV=0.153 following Schlegel et al. (1998).

The extinction varies by 0.006 mag rms within a radius of

6 arcmin around NGC 3957. Considering random errors alone,

the 1-![]() final accuracy of our calibration is 0.022 mag, in R, and 0.036 mag, in V.

final accuracy of our calibration is 0.022 mag, in R, and 0.036 mag, in V.

4 Surface brightness profiles

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{13320fig6.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13320-09/Timg30.png)

|

Figure 5: Cone shaped regions used to integrate the light on the final coadded V and R images. North is to the top, east to the right. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

In order to trace the galaxy signal down to very faint levels with a

sufficiently high signal-to-noise ratio, we integrated flux in

![]() wedges, running along the minor axis of the galaxy (Fig. 5).

Prior to this binning, the foreground stars were carefully masked, as

the background galaxies. The radial width of each bin was chosen as a

trade-off between the spatial resolution of the galaxy profile and the

desired signal-to-noise per bin. The narrowest bins have an

annular width of 2 pixels (0.04 kpc) and are located in the

central parts of the galaxy, while the widest ones have a radial extent

of 100 pixels (1 kpc). The resulting surface

brightness profiles in V and R-bands, obtained by taking the average of the flux in all unmasked pixel in each radial ring, are shown in Fig. 6, where the dashed lines indicate the

detection limits per square arcsecond. The spatial sampling is five times finer than that of Zibetti et al. (2004) in the inner galactic regions, while in the outer parts, the spatial sampling of the two studies is the same. However, unlike Zibetti et al. (2004), who get a signal-to-noise

of 1 for the outermost bins at

wedges, running along the minor axis of the galaxy (Fig. 5).

Prior to this binning, the foreground stars were carefully masked, as

the background galaxies. The radial width of each bin was chosen as a

trade-off between the spatial resolution of the galaxy profile and the

desired signal-to-noise per bin. The narrowest bins have an

annular width of 2 pixels (0.04 kpc) and are located in the

central parts of the galaxy, while the widest ones have a radial extent

of 100 pixels (1 kpc). The resulting surface

brightness profiles in V and R-bands, obtained by taking the average of the flux in all unmasked pixel in each radial ring, are shown in Fig. 6, where the dashed lines indicate the

detection limits per square arcsecond. The spatial sampling is five times finer than that of Zibetti et al. (2004) in the inner galactic regions, while in the outer parts, the spatial sampling of the two studies is the same. However, unlike Zibetti et al. (2004), who get a signal-to-noise

of 1 for the outermost bins at ![]() 12-14 kpc, we are not limited by photon noise in these parts (S/N

12-14 kpc, we are not limited by photon noise in these parts (S/N ![]() 20). Systematic errors (see Sect. 5) start dominating over photon noise at r = 8-10 kpc, where our S/N is still

20). Systematic errors (see Sect. 5) start dominating over photon noise at r = 8-10 kpc, where our S/N is still ![]() 40 in V and R.

40 in V and R.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{13320fig7.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13320-09/Timg32.png)

|

Figure 6:

V- (black) and R-band (red) surface brightness profiles

along the minor-axis of NGC 3957. Errors due to photon noise are typically |

| Open with DEXTER | |

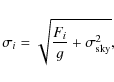

We estimated the photon noise

![]() per bin by adding in quadrature the photon noise of all N pixels in a cone-shape bin

per bin by adding in quadrature the photon noise of all N pixels in a cone-shape bin

|

(5) |

where the sum goes over all non-masked pixels. The noise per pixel, i, on the sky-subtracted and coadded frame is

|

(6) |

where Fi is the flux in pixel i, g is the electron-to-adu conversion factor, and

5 Possible systematic errors

Whilst our detection of the NGC 3957 stellar halo is not limited by photon noise, it may still be affected by a number of systematic errors that we now review and try to quantify. This is of particular importance when trying to interpret the radial changes in the colour profiles.

5.1 Flat fields

Errors in flat-fielding may cause artificial gradients in the sky background and, in turn, affect the actual halo colour gradient. Since our skyflats were not taken each night, a possible source of error is a the temporal variability of the flat-fields over a period of several nights. In order to estimate this variability, we compare our normalized R-band flat-field obtained at the beginning of the observing run (24 April 2006) with the one corresponding to the end of the observing run (25 May 2006). The changes during this one month period do not exceed 1.5% across the whole field of view. Since we used the same flat-fields for the sky and the galaxy frames (see Fig. 4), errors in the flat-fields propagate linearly into errors in the final profiles. Consequently, a 1.5% deviation in the flat-field results in a 1.5% deviation in the the surface brightness. This translates into a maximum change of shape of 0.01 mag, i.e., completely negligible compared with the photon noise.

5.2 Extended PSF tails

In a recent work, de Jong (2008) discusses how the extended wings of the point spread function (PSF) can significantly contaminate the measurement of galaxy halo light if not properly accounted for.

By targeting a very low redshift galaxy with a size extending

over several arcminutes, we ensured that even the most extended parts

of the PSF did not affect the galaxy's surface brightness profiles

at all. Indeed, the PSF in our coadded frames has a FWHM ![]() 1

1

![]() ,

which is more than 100 times smaller than the extent of the measured galaxy halo. For comparison, de Jong (2008) deals with PSFs that are about ten times smaller than the observed galaxy.

,

which is more than 100 times smaller than the extent of the measured galaxy halo. For comparison, de Jong (2008) deals with PSFs that are about ten times smaller than the observed galaxy.

In addition, we checked that the wings of the PSF have a limited size.

At 1.8 arcsec (corresponding to 0.2 kpc at the distance

of NGC 3957) the flux in our PSF drops to 0.72% of its

central intensity in R, and to 2.55% of the central intensity in V.

The integrated flux of bright standard stars through apertures of

growing radius showed that there was no measurable flux in the

PSF wings already at 15

![]() away

from the core. Finally, we scaled the PSF to the central

intensity of NGC 3957 and measured the flux in its wings.

At 50 pixels, i.e., 1.1 kpc from the

PSF centre, the level of the flux was

below 0.01 ADU, i.e., not measurable. It is clear

that the wings of the PSF have no effect on our surface brightness

profiles.

away

from the core. Finally, we scaled the PSF to the central

intensity of NGC 3957 and measured the flux in its wings.

At 50 pixels, i.e., 1.1 kpc from the

PSF centre, the level of the flux was

below 0.01 ADU, i.e., not measurable. It is clear

that the wings of the PSF have no effect on our surface brightness

profiles.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{13320fig8.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13320-09/Timg37.png)

|

Figure 7:

Mean flux level as measured in a 100 |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=5.75cm,clip]{13320fig9.ps}\hspace*{5mm...

...phics[width=5.75cm,clip]{13320fig12.ps}\hspace*{4mm}\vspace*{3mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13320-09/Timg38.png)

|

Figure 8: The two-component fits to the minor axis profiles in the V and R-bands. The observed profiles are shown with solid dots with attached error bars (see Sect. 5). The last point of the V-West profile is not shown, neither is it used in the fits, because it is obviously dominated by errors (see Sect. 4). The red lines indicate the de Vaucouleurs law, which best fits the bulge of NGC 3957. The red solid line indicates the region of the fits within 5 kpc, while the dashed line shows its extrapolation to larger radii. The blue lines show the power-law component of the fit at radii larger than 5 kpc. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

5.3 Difference in the CCD responses:  -factors

-factors

The ![]() coefficient described in Sect. 3 (Eq. (2)) accounts for the difference in sensitivity between the two CCDs. The determination of this factor for each

single epoch was carried out in two steps.

coefficient described in Sect. 3 (Eq. (2)) accounts for the difference in sensitivity between the two CCDs. The determination of this factor for each

single epoch was carried out in two steps.

- 1-

- We initialized a first guess value by dividing CCD1 and CCD2 flatfields by pairs.

- 2-

- We applied a small correction to this initial value by

noticing that the scaling of the sky frames subtracted from CCD1 is

proportional to

,

while the scaling for CCD2 is proportional to

,

while the scaling for CCD2 is proportional to

.

As a consequence, a slight error in

.

As a consequence, a slight error in  is immediately seen as a

systematic flux offset between the two CCDs, which is minimal when the value of

is immediately seen as a

systematic flux offset between the two CCDs, which is minimal when the value of  is such that the sky subtracts equally well in CCD1 and

in CCD2. In order to evaluate this offset and to correct

for it, we determined in each individual sky-subtracted frame the

mean flux level in a 100

is such that the sky subtracts equally well in CCD1 and

in CCD2. In order to evaluate this offset and to correct

for it, we determined in each individual sky-subtracted frame the

mean flux level in a 100  100 pixels empty region close to the image boundary. Our final measurements are shown in Fig. 7 after correction; there is no residual offset between the mean

100 pixels empty region close to the image boundary. Our final measurements are shown in Fig. 7 after correction; there is no residual offset between the mean

factors of CCD1 and CCD2.

factors of CCD1 and CCD2.

5.4 Sky-level scaling:  -factors

-factors

The determination of the mean sky level in each individual image is

affected by shot noise, which in turn leads to an over- or

under-subtraction through erroneous ![]() factors (Eq. (1)).

While quantifying this error for each image taken separately is

impossible, we used the full data set to estimate the amplitude of the

fluctuations with time. This is equivalent to measuring the

scatter of the

factors (Eq. (1)).

While quantifying this error for each image taken separately is

impossible, we used the full data set to estimate the amplitude of the

fluctuations with time. This is equivalent to measuring the

scatter of the ![]() factors for a fixed

factors for a fixed ![]() .

.

The amplitude of the random fluctuations of the scale factor ![]() can be estimated from the scatter of the points in Fig. 7. The standard deviation of the 132 R-band images is 4.66 ADU, while the uncertainty on the mean

can be estimated from the scatter of the points in Fig. 7. The standard deviation of the 132 R-band images is 4.66 ADU, while the uncertainty on the mean ![]() is 0.41 ADU. Similarly, the standard deviation of the 50 V-band frames is 3.75 ADU, while the uncertainty of the mean value of

is 0.41 ADU. Similarly, the standard deviation of the 50 V-band frames is 3.75 ADU, while the uncertainty of the mean value of ![]() is 0.53 ADU. These values provide good estimates of an upper limit on the errors on

is 0.53 ADU. These values provide good estimates of an upper limit on the errors on ![]() in V and R.

in V and R.

A systematic error on ![]() may have important consequences on the colour profile of the galaxy,

in particular if the amplitude of the error is different in V and in R. In order to estimate this effect, we artificially introduced an over- or under-subtraction of the sky by 2

may have important consequences on the colour profile of the galaxy,

in particular if the amplitude of the error is different in V and in R. In order to estimate this effect, we artificially introduced an over- or under-subtraction of the sky by 2![]() in both bands. This corresponds to a shift of 2

in both bands. This corresponds to a shift of 2 ![]() 0.41

0.41 ![]() 0.8 ADU in R and

2

0.8 ADU in R and

2 ![]() 0.53

0.53 ![]() 1.1 ADU in V.

1.1 ADU in V.

It translates into a variation of ![]() 0.05 mag at 25.5 mag arcsec2,

0.05 mag at 25.5 mag arcsec2, ![]() 0.2 mag at 27 mag arcsec2 and

0.2 mag at 27 mag arcsec2 and ![]() 0.5 mag at 28 mag arcsec2 in the R-band. Similarly, the shifts in the V-band are

0.5 mag at 28 mag arcsec2 in the R-band. Similarly, the shifts in the V-band are ![]() 0.05 mag,

0.05 mag, ![]() 0.4 mag, and more than

0.4 mag, and more than ![]() 1.0 mag at 26, 28, and 30 mag arcsec2, respectively.

1.0 mag at 26, 28, and 30 mag arcsec2, respectively.

5.5 Extended halo

The last possible source of error is the presence of a very extended halo signal in the SKY1![]() and SKY2

and SKY2![]() frames used to scale MS2 and MS1 before subtraction (see Fig. 4).

This rescaling indeed assumes that the CCD frames, which do not

contain NGC 3957, are far enough away from the galaxy to be

free from any residual halo light.

frames used to scale MS2 and MS1 before subtraction (see Fig. 4).

This rescaling indeed assumes that the CCD frames, which do not

contain NGC 3957, are far enough away from the galaxy to be

free from any residual halo light.

Since the reduction and scaling procedures are the same in the V and R filters, the systematics causing a positive (negative) shift in V would also cause a positive (negative) shift in R. From their radial minor axis profiles of M 31, Irwin et al. (2005) derive a power law surface brightness profile following

![]() ,

beyond 20 kpc. We used this relation to evaluate to what extent SKY1

,

beyond 20 kpc. We used this relation to evaluate to what extent SKY1![]() and SKY2

and SKY2![]() might

be contaminated by extended halo light from one

CCD on the other. Our sky frames are located at a minimum of twice the

distance from the galaxy centre to the edge of our galaxy profile.

Assuming the Irwin et al. (2005)

M 31 halo surface brightness can be considered representative, the

halo light in the CCDs we used to measure the sky should be at least

five times fainter than at the edge of the CCD that contains

the galaxy.

might

be contaminated by extended halo light from one

CCD on the other. Our sky frames are located at a minimum of twice the

distance from the galaxy centre to the edge of our galaxy profile.

Assuming the Irwin et al. (2005)

M 31 halo surface brightness can be considered representative, the

halo light in the CCDs we used to measure the sky should be at least

five times fainter than at the edge of the CCD that contains

the galaxy.

This translates into an error of 1 ADU/pixel, which is a

very conservative value, corresponding to about 40% of the

measured R-band flux and 60% of the flux in the V-band at 13 kpc from the

galaxy centre. This modifies the V and R East-side magnitudes by ![]() 0.03 mag at 5 kpc,

0.03 mag at 5 kpc, ![]() 0.2 mag at 10 kpc, and

0.2 mag at 10 kpc, and ![]() 0.3-0.4 mag (R) respectively

0.3-0.4 mag (R) respectively ![]() 0.5 mag (V) at 15 kpc.

0.5 mag (V) at 15 kpc.

5.6 Total error budget

To summarize, the main possible sources of errors that can affect the V and R surface

brightness profiles of NGC 3957 presented here are i) the

uncertainties related to the scaling of the sky-level

through the ![]() -factors

and ii) the possible overestimation of the actual sky background

level, caused by contamination by a genuine extended stellar halo

signal in the regions used to build the

sky frames. This latter factor can only act as sky over-subtraction and

therefore will contribute only to the upper limit of the error bars.

Our surface brightness profiles are presented in

Fig. 8, along with their total error bars.

-factors

and ii) the possible overestimation of the actual sky background

level, caused by contamination by a genuine extended stellar halo

signal in the regions used to build the

sky frames. This latter factor can only act as sky over-subtraction and

therefore will contribute only to the upper limit of the error bars.

Our surface brightness profiles are presented in

Fig. 8, along with their total error bars.

6 Properties of the stellar halo

6.1 Detection in V and R

As shown in Fig. 6,

we clearly detect light up to about 15 kpc away from the centre of

NGC 3957. In order to evaluate the structure of this luminous

component and, more importantly, to see whether one can resolve it into

more than a single structure, we performed 1D-fits to the V and R profiles.

We considered only the photon noise error bars, since they are the only

statistically meaningful quantities to be taken into account in ![]() procedures. We used the IDL routine mpfit,

which solves the least-squares problem with the Levenberg-Marquardt

technique, to conduct the fits. The inner 0.5 kpc region was

not considered due to the presence of the dust lane. We first started

with a de Vaucouleur law form, chosen to best represent the

bulge of this S0 galaxy. Figure 8 shows that while a r1/4 function with an effective radius of 0.29 kpc provides an excellent description of

the inner profile in both in V and R

of NGC 3957, it considerably under-predicts the light beyond

4-5 kpc. Beyond 5 kpc, the excess light is

well-represented by a power-law with index -2.76

procedures. We used the IDL routine mpfit,

which solves the least-squares problem with the Levenberg-Marquardt

technique, to conduct the fits. The inner 0.5 kpc region was

not considered due to the presence of the dust lane. We first started

with a de Vaucouleur law form, chosen to best represent the

bulge of this S0 galaxy. Figure 8 shows that while a r1/4 function with an effective radius of 0.29 kpc provides an excellent description of

the inner profile in both in V and R

of NGC 3957, it considerably under-predicts the light beyond

4-5 kpc. Beyond 5 kpc, the excess light is

well-represented by a power-law with index -2.76 ![]() 0.43.

A pure exponential fit with a scale length of a few kpc

always provides a worse fits, particularly in the R-band, for which it was essentially discarded. Ibata et al. (2009)

applied a de Vaucouleur law with an effective radius of

1.55 kpc to NGC 891's extra-planar light, but this did

not provide a good description of the light detected here.

0.43.

A pure exponential fit with a scale length of a few kpc

always provides a worse fits, particularly in the R-band, for which it was essentially discarded. Ibata et al. (2009)

applied a de Vaucouleur law with an effective radius of

1.55 kpc to NGC 891's extra-planar light, but this did

not provide a good description of the light detected here.

Pohlen et al. (2004) present 3D thick/thin disc decompositions for a sample of eight S0 galaxies, including NGC 3957. They derive an R-band

vertical scale height for the thick disc component of 2.3 kpc,

which, by their definition, corresponds to a normal exponential

vertical scale height of 1.65 kpc. In order to compare this

value with our own, we needed to extract a vertical profile some

distance from the minor axis in order to eliminate the influence of the

bulge. Figure 9 shows the V and R West

and East profiles of NGC 3957 extracted at a position 5 kpc

along the major axis. Fitting the thick disc between 2 and

4 kpc, we found an exponential scale height of 1.27 kpc,

which agrees well with that found by Pohlen et al. (2004),

considering the different ways in which the two studies have extracted

profiles and their different photometric depths and spatial

resolutions. This fit and also that from Pohlen et al. (2004) are overlaid in the figure. Figure 9 also underscores the need for an additional component beyond a thick disc at vertical distances greater than ![]() 4 kpc.

4 kpc.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{13320fig13.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13320-09/Timg41.png)

|

Figure 9: The R-band vertical profile of NGC 3957 extracted at a position 5 kpc along the major axis. The observations are displayed with open circles. The Pohlen et al. (2004) fits of the thin and thick discs are indicated with a dashed red line, while our pure exponential fits are shown with a plain blue line. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

6.2 Colour profile

Figure 10 displays the minor-axis colour profile of NGC 3957. The apparent strong reddening at large galactocentric distances must be analysed in light of the possible systematic errors presented in Sect. 5. As seen in Fig. 6, the NGC 3957 surface brightness profile is traced down to about 1.2 mag above the detection limit both in V and R bands.

We now analyse the west side of the galaxy (negative values of the

radii) as an illustration of the different elements at play. The total

error bars in V and R are small and similar from the galaxy centre, up to about 8.5 kpc (

![]() mag). At 9.5 kpc, the error in V is 0.2 mag larger than the one in R.

This difference keeps increasing with the radius, reaching

0.95 mag at 10.5 kpc. This effect is due to the strong

decrease in V-flux rendering the sky subtraction very critical,

i.e., a given error on the sky subtraction has much larger

impact on the V-band fainter profile than on the R-band one. To be quantitative, at 8.5 kpc, the V and R fluxes are at the level of

mag). At 9.5 kpc, the error in V is 0.2 mag larger than the one in R.

This difference keeps increasing with the radius, reaching

0.95 mag at 10.5 kpc. This effect is due to the strong

decrease in V-flux rendering the sky subtraction very critical,

i.e., a given error on the sky subtraction has much larger

impact on the V-band fainter profile than on the R-band one. To be quantitative, at 8.5 kpc, the V and R fluxes are at the level of ![]() 4 ADU/pixel and

4 ADU/pixel and ![]() 4.5 ADU/pixel, respectively. At 9.5 kpc, we measure only

4.5 ADU/pixel, respectively. At 9.5 kpc, we measure only ![]() 2 ADU/pixel and

2 ADU/pixel and ![]() 3.5 ADU/pixel in V and R, respectively. Figure 10 clearly shows that the larger the error bars due to systematics, the steeper the rise in V-R.

This suggests that this reddening may not be a genuine property of the

stellar/dust properties of NGC 3957 halo, but rather an artifact

due to the sharp drop in the V flux. The sky subtraction

becomes very uncertain and leads to biased results when the halo

surface brightness approaches the

detection limit by less than two magnitudes, as indicated in

Fig. 6. This is the case at a distance of 10 kpc from the galaxy centre in V, and at 15 kpc in the R-band.

3.5 ADU/pixel in V and R, respectively. Figure 10 clearly shows that the larger the error bars due to systematics, the steeper the rise in V-R.

This suggests that this reddening may not be a genuine property of the

stellar/dust properties of NGC 3957 halo, but rather an artifact

due to the sharp drop in the V flux. The sky subtraction

becomes very uncertain and leads to biased results when the halo

surface brightness approaches the

detection limit by less than two magnitudes, as indicated in

Fig. 6. This is the case at a distance of 10 kpc from the galaxy centre in V, and at 15 kpc in the R-band.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{13320fig14.eps}

\vspace*{4mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13320-09/Timg43.png)

|

Figure 10:

The V-R

colour profile of NGC 3957. The edges of the vertical

bars show the maximum possible systematic errors, which dominate over

the photon noise, as estimated from the uncertainties in the sky-level

scaling |

| Open with DEXTER | |

The west-side mean colour profile has V-R ![]() 0.50

0.50 ![]() 0.02 from 2 kpc from the centre of the galaxy, up to 5 kpc and then marginally rises to 0.70

0.02 from 2 kpc from the centre of the galaxy, up to 5 kpc and then marginally rises to 0.70 ![]() 0.2, at 8 kpc. As discussed earlier, the error bars

are not independent from each other and rather reflect systematic

errors. They all act in the same direction, either increasing or

decreasing the overall V-R profile.

The upper boundary (i.e., connecting the upper limits of the error

bars) corresponds to an error of 1 ADU/pix on the true sky level,

or equivalently to a 3

0.2, at 8 kpc. As discussed earlier, the error bars

are not independent from each other and rather reflect systematic

errors. They all act in the same direction, either increasing or

decreasing the overall V-R profile.

The upper boundary (i.e., connecting the upper limits of the error

bars) corresponds to an error of 1 ADU/pix on the true sky level,

or equivalently to a 3![]() error (1.2 and 1.6 ADU in R and V,

respectively) on the scaling of the sky. Although very modest, these

values have noticeable consequences on the shape of the profiles,

due to the faint luminosity levels considered here.

In regions where the V-R gradient is steeper

than 0.1-0.2 mag per kpc, the systematic errors

dominate. The analysis of the east side of NGC 3957 follows the

same line, albeit the mean colour is redder by

error (1.2 and 1.6 ADU in R and V,

respectively) on the scaling of the sky. Although very modest, these

values have noticeable consequences on the shape of the profiles,

due to the faint luminosity levels considered here.

In regions where the V-R gradient is steeper

than 0.1-0.2 mag per kpc, the systematic errors

dominate. The analysis of the east side of NGC 3957 follows the

same line, albeit the mean colour is redder by ![]() 0.05 mag

with respect to the west-side, even in the regions where the

systematic errors are negligible. The small colour asymmetry between

the east and west sides of NGC 3957 is intriguing and could

possibly reflect fluctuations due to substructures within

the galaxy's halo.

0.05 mag

with respect to the west-side, even in the regions where the

systematic errors are negligible. The small colour asymmetry between

the east and west sides of NGC 3957 is intriguing and could

possibly reflect fluctuations due to substructures within

the galaxy's halo.

We now investigate whether the inner halo colour of

NGC 3957 is indeed compatible with those of normal stellar

populations, and conduct comparisons with a few galaxies for which

the halo stellar

population could be resolved and analysed. We decomposed the halo

population into the same number of single stellar populations (SSPs) as

there are bins in the published metallicity distribution function

(MDF). These SSPs were generated with metallicities equal to that of

the bin mean using the Y2 isochrones of Kim et al. (2002), that extend down to [Fe/H] = -3.8, with

[![]() /Fe] = 0.3,

a Salpeter IMF and a 13 Gyr age. When necessary the

isochrones were interpolated to represent the metallicities of

the MDFs. The resultant SSPs were then summed in luminosity,

weighted by the fraction of light contributed by each MDF bin.

/Fe] = 0.3,

a Salpeter IMF and a 13 Gyr age. When necessary the

isochrones were interpolated to represent the metallicities of

the MDFs. The resultant SSPs were then summed in luminosity,

weighted by the fraction of light contributed by each MDF bin.

We first derived the expected integrated V-R colour of the Milky Way halo from the metallicity distribution of Carollo et al. (2010). They find that from a vertical distance of 5 kpc up to 9 kpc above the Galactic plane, which corresponds to the regions we sampled in the present study, the halo stellar metallicities span [Fe/H] = -3.0 to -1 with a small fraction of stars reaching [Fe/H] = -0.5. The distributions at 5.5 kpc and 8.5 kpc, peaking at [Fe/H] = -1.5 at and [Fe/H] = -2, respectively, lead to V-R = 0.49 and 0.47. This narrow range of colours is due to the progressive insensitivity of the isochrones to changes in metallicity at low [Fe/H].

As to M 31, the complex web of stellar streams prevented

us from deriving a priori a unique colour for its halo. We instead

examined the possible range of values based on earlier works providing

complete metallicity distributions. The metallicity distribution

derived by Ibata et al. (2007) from the diffuse light of M 31 halo translates into

![]() .

The M2 field of Durrell et al. (2001), located at 20 kpc along the M 31 minor axis, peaks at [M/H]

.

The M2 field of Durrell et al. (2001), located at 20 kpc along the M 31 minor axis, peaks at [M/H] ![]() -0.5 with a long tail of more metal-poor population down to -2.5, leading to an integrated

-0.5 with a long tail of more metal-poor population down to -2.5, leading to an integrated

![]() .

In contrast, the spectroscopic study of Koch et al. (2008) reveals a strong metallicity gradient with a peak at [Fe/H]

.

In contrast, the spectroscopic study of Koch et al. (2008) reveals a strong metallicity gradient with a peak at [Fe/H] ![]() -1. for galactocentric distances between

20 kpc and 40 kpc and at [Fe/H]

-1. for galactocentric distances between

20 kpc and 40 kpc and at [Fe/H] ![]() -2 beyond 40 kpc, with V-R

-2 beyond 40 kpc, with V-R ![]() 0.47.

0.47.

Now turning to slightly more distant galaxies Mouhcine et al. (2007) analyse the 1.5 first magnitude of the RGB stars in the halo NGC 891, at ![]() 9.5 kpc from the galactic plane,

centred on V-I

9.5 kpc from the galactic plane,

centred on V-I ![]() 1.5 and derive a peak metallicity of [Fe/H]

1.5 and derive a peak metallicity of [Fe/H] ![]() -1, i.e., close to an integrated colour of V-R

-1, i.e., close to an integrated colour of V-R ![]() 0.5. Some of the galaxies in the sample of Mouhcine et al. (2005a) have metallicity distribution peaks at [M/H]

0.5. Some of the galaxies in the sample of Mouhcine et al. (2005a) have metallicity distribution peaks at [M/H] ![]() -0.6. Their full metallicity distributions results in an integrated V-R

-0.6. Their full metallicity distributions results in an integrated V-R ![]() 0.54.

0.54.

In summary, V-R from ![]() 0.45 to

0.45 to ![]() 0.6 constitutes

the range of expected integrated colours of old and preferentially

metal-poor galactic halos. The halo of NGC 3957, with V-R

from 0.5

to 0.7 mag, between 5 and 8 kpc from the galaxy centre,

where the stellar halo component is clearly dominating and the

systematic errors are still modest, agrees fairly well with these

numbers. Beyond these vertical distances, the colour reddening

correlates with increasing errors. The order magnitude of the former

being similar or smaller than that of the latter suggests that the

colour gradient is due to the uncertainties in sky subtraction at very

faint flux levels.

0.6 constitutes

the range of expected integrated colours of old and preferentially

metal-poor galactic halos. The halo of NGC 3957, with V-R

from 0.5

to 0.7 mag, between 5 and 8 kpc from the galaxy centre,

where the stellar halo component is clearly dominating and the

systematic errors are still modest, agrees fairly well with these

numbers. Beyond these vertical distances, the colour reddening

correlates with increasing errors. The order magnitude of the former

being similar or smaller than that of the latter suggests that the

colour gradient is due to the uncertainties in sky subtraction at very

faint flux levels.

7 Conclusions

We obtained ultra-deep optical VLT/VIMOS images of NGC 3957, a nearby edge-on S0 galaxy. The total exposure time of six hours in R and 7 h in V allowed us to reach the limiting magnitudes of R = 30.6 mag/arcsec2 and V = 31.4 mag/arcsec2 in the Vega system.

We devised a new observational strategy based on infrared techniques, which takes advantage of the large field of view of VIMOS. By observing NGC 3957 alternatively in two different CCDs, we were able to create high signal-to-noise and stable sky frames, which were used to carry out accurate sky subtraction, without any assumption on the spatial shape and flux level of the sky background. The observations allowed us to reach unprecedented high signal-to-noise ratios up 15 kpc away from the galaxy centre, rendering photon-noise negligible. They enabled the clear detection of the stellar halo of NGC 3957 at distances above 5 kpc.

We conducted a thorough analysis of the possible sources of

systematic error that could affect the vertical surface brightness and

colour profiles: flat-fielding, differences in CCD responses,

scaling of the sky background, extended halo, PSF wings. While

a r1/4 function with an effective radius of 0.29 kpc provides an excellent description of the inner V and R-band

minor axis profiles of NGC 3957, it under-predicts the light

beyond 4-5 kpc. Above 5 kpc, the galaxy light

profile requires an additional power-law component with index

-2.76 ![]() 0.43.

0.43.

The most secure part of the NGC 3957 halo colour profile falls in the range

![]() mag.

This colour is compatible with the properties of nearby galaxy halos as

revealed by the investigation of their resolved stellar populations and

with that of the Milky Way. An apparent strong reddening is

seen in the outer parts (r

mag.

This colour is compatible with the properties of nearby galaxy halos as

revealed by the investigation of their resolved stellar populations and

with that of the Milky Way. An apparent strong reddening is

seen in the outer parts (r ![]() 8 kpc) of the V-R profile,

similarly to earlier works on galaxy halo surface brightness profiles.

However, our analysis indicates that this

reddening may not be a genuine property of the stellar/dust properties

of NGC 3957 halo, and simply reflects the impact of systematic

errors in sky subtraction at extremely faint flux levels. It is

possible that previously published reports of extremely red colours in

external galaxy halos could have resulted from similar effects.

8 kpc) of the V-R profile,

similarly to earlier works on galaxy halo surface brightness profiles.

However, our analysis indicates that this

reddening may not be a genuine property of the stellar/dust properties

of NGC 3957 halo, and simply reflects the impact of systematic

errors in sky subtraction at extremely faint flux levels. It is

possible that previously published reports of extremely red colours in

external galaxy halos could have resulted from similar effects.

Future imaging programmes benefiting from larger fields of view (

![]() degree

on one side) will allow the systematics in halo emission searches to be

controlled even further. Existing facilities to carry out the

experiment include the SuprimeCam on the Subaru telescope and

the VST (VLT survey telescope).

degree

on one side) will allow the systematics in halo emission searches to be

controlled even further. Existing facilities to carry out the

experiment include the SuprimeCam on the Subaru telescope and

the VST (VLT survey telescope).

This research used the facilities of the Canadian Astronomy Data Centre operated by the National Research Council of Canada with the support of the Canadian Space Agency. This research is partially supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF). AMNF is supported by a Marie Curie Excellence Grant from the European Commission under contract MCEXT-CT-2005-025869.

References

- Abadi, M. G., Navarro, J. F., & Steinmetz, M. 2006, MNRAS, 365, 747 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Barker, M. K., Ferguson, A. M. N., Irwin, M., Arimoto, N., & Jablonka, P. 2009, AJ, 138, 1469 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bell, E. F., Zucker, D. B., Belokurov, V., et al. 2008, ApJ, 680, 295 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Belokurov, V., Evans, N. W., Irwin, M. J., et al. 2007, ApJ, 658, 337 [Google Scholar]

- Bullock, J. S., & Johnston, K. V. 2005, ApJ, 635, 931 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Carollo, D., Beers, T. C., Chiba, M., et al. 2010, ApJ, 712, 692 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong, R. S. 2008, MNRAS, 388, 1521 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Durrell, P. R., Harris, W. E., & Pritchet, C. J. 2001, AJ, 121, 2557 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Eggen, O. J., Lynden-Bell, D., & Sandage, A. R. 1962, ApJ, 136, 748 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, A. M. N., Irwin, M. J., Ibata, R. A., Lewis, G. F., & Tanvir, N. R. 2002, AJ, 124, 1452 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Font, A. S., Johnston, K. V., Bullock, J. S., & Robertson, B. E. 2006, ApJ, 638, 585 [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore, G., Wyse, R. F. G., & Norris, J. E. 2002, ApJ, 574, L39 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Grillmair, C. J. 2006, ApJ, 645, L37 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ibata, R. A., Gilmore, G., & Irwin, M. J. 1994, Nature, 370, 194 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ibata, R., Irwin, M., Lewis, G., Ferguson, A. M. N., & Tanvir, N. 2001, Nature, 412, 49 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibata, R., Martin, N. F., Irwin, M., et al. 2007, ApJ, 671, 1591 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ibata, R., Mouhcine, M., & Rejkuba, M. 2009, MNRAS, 395, 126 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin, M. J., Ferguson, A. M. N., Ibata, R. A., Lewis, G. F., & Tanvir, N. R. 2005, ApJ, 628, L105 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [MathSciNet] [Google Scholar]

- Juric, M., Ivezic, Z., Brooks, A., et al. 2008, ApJ, 673, 864 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [MathSciNet] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y., Demarque, P., Yi, S. K., & Alexander, D. R. 2002, ApJS, 143, 499 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Koch, A., Rich, R. M., Reitzel, D. B., et al. 2008, ApJ, 689, 958 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lequeux, J., Fort, B., Dantel-Fort, M., Cuillandre, J.-C., & Mellier, Y. 1996, A&A, 312, L1 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Lequeux, J., Combes, F., Dantel-Fort, M., et al. 1998, A&A, 334, L9 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Majewski, S. R., Siegel, M. H., Kunkel, W. E., et al. 1999, AJ, 118, 1709 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Delgado, D., Peñarrubia, J., Gabany, R. J., et al. 2008, ApJ, 689, 184 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Delgado, D., Pohlen, M., Gabany, R. J., et al. 2009, ApJ, 692, 955 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- McConnachie, A. W., Irwin, M. J., Ibata, R. A., et al. 2009, Nature, 461, 66 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouhcine, M., Ferguson, H. C., Rich, R. M., Brown, T. M., & Smith, T. E. 2005a, ApJ, 633, 821 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mouhcine, M., Rich, R. M., Ferguson, H. C., Brown, T. M., & Smith, T. E. 2005b, ApJ, 633, 828 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mouhcine, M., Rejkuba, M., & Ibata, R. 2007, MNRAS, 381, 873 [Google Scholar]

- Newberg, H. J., Yanny, B., Rockosi, C., et al. 2002, ApJ, 569, 245 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pohlen, M., Balcells, M., Lütticke, R., & Dettmar, R.-J. 2004, A&A, 422, 465 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Rejkuba, M., Mouhcine, M., & Ibata, R. 2009, MNRAS, 396, 1231 [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, J. C., Ferguson, A. M. N., Johnson, R. A., et al. 2008, AJ, 135, 1998 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha-Pinto, H. J., Majewski, S. R., Skrutskie, M. F., & Crane, J. D. 2003, ApJ, 594, L115 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sackett, P. D., Morrison, H. L., Harding, P., & Boroson, T. A. 1994, Nature, 370, 441 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Schlegel, D. J., Finkbeiner, D. P., & Davis, M. 1998, ApJ, 500, 525 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, M., Chiba, M., Komiyama, Y., et al. 2010, ApJ, 708, 1168 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Vivas, A. K., & Zinn, R. 2006, AJ, 132, 714 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Z., Shang, Z., Su, H., et al. 1999, AJ, 117, 2757 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Zibetti, S., & Ferguson, A. M. N. 2004, MNRAS, 352, L6 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Zibetti, S., White, S. D. M., & Brinkmann, J. 2004, MNRAS, 347, 556 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Footnotes

- ... case

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- Based on observations obtained at the ESO Very Large Telescope (VLT) in the Program 077.B0145(A).

All Tables

Table 1: Journal of the observations.

All Figures

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=7.cm]{13320fig1.eps}\hspace*{0.7cm}

\includegraphics[width=7.cm]{13320fig2.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13320-09/Timg15.png)

|

Figure 1:

Left: dithering pattern for a set of 12 consecutive R-band

frames. The position (0, 0) indicates the initial position of NGC 3957 in one CCD. Right: dithering pattern for a set of six consecutive V-band exposures. Units are given in pixels. One pixel is 0.205

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=12cm,clip]{13320fig3.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13320-09/Timg16.png)

|

Figure 2: Geometry of the VIMOS field of view, composed of four CCDs, prior to sky subtraction. The galaxy was alternately put in CCD1 and in CCD2. The black feature in CCD3 and CCD4 is due to the guide star camera. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=12cm,clip]{13320fig4.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13320-09/Timg19.png)

|

Figure 3:

Example of the master sky in R ( left panel) and V ( right panel). The cuts are

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{13320fig5.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13320-09/Timg29.png)

|

Figure 4:

Explanation of the scaling scheme, prior to the image

coaddition. The master sky of CCD1 (MS1) is taken as a reference. The i index refers to the individual exposures within a sequence. The factors

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{13320fig6.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13320-09/Timg30.png)

|

Figure 5: Cone shaped regions used to integrate the light on the final coadded V and R images. North is to the top, east to the right. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{13320fig7.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13320-09/Timg32.png)

|

Figure 6:

V- (black) and R-band (red) surface brightness profiles

along the minor-axis of NGC 3957. Errors due to photon noise are typically |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{13320fig8.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13320-09/Timg37.png)

|

Figure 7:

Mean flux level as measured in a 100 |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=5.75cm,clip]{13320fig9.ps}\hspace*{5mm...

...phics[width=5.75cm,clip]{13320fig12.ps}\hspace*{4mm}\vspace*{3mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13320-09/Timg38.png)

|

Figure 8: The two-component fits to the minor axis profiles in the V and R-bands. The observed profiles are shown with solid dots with attached error bars (see Sect. 5). The last point of the V-West profile is not shown, neither is it used in the fits, because it is obviously dominated by errors (see Sect. 4). The red lines indicate the de Vaucouleurs law, which best fits the bulge of NGC 3957. The red solid line indicates the region of the fits within 5 kpc, while the dashed line shows its extrapolation to larger radii. The blue lines show the power-law component of the fit at radii larger than 5 kpc. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{13320fig13.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13320-09/Timg41.png)

|

Figure 9: The R-band vertical profile of NGC 3957 extracted at a position 5 kpc along the major axis. The observations are displayed with open circles. The Pohlen et al. (2004) fits of the thin and thick discs are indicated with a dashed red line, while our pure exponential fits are shown with a plain blue line. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{13320fig14.eps}

\vspace*{4mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa13320-09/Timg43.png)

|

Figure 10:

The V-R

colour profile of NGC 3957. The edges of the vertical

bars show the maximum possible systematic errors, which dominate over

the photon noise, as estimated from the uncertainties in the sky-level

scaling |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

Copyright ESO 2010

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.