| Issue |

A&A

Volume 510, February 2010

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A19 | |

| Number of page(s) | 15 | |

| Section | Extragalactic astronomy | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/200913041 | |

| Published online | 02 February 2010 | |

Integrated K-band spectra of old and intermediate-age globular clusters in the Large Magellanic Cloud![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png) ,

,![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

M. Lyubenova1 - H. Kuntschner2 - M. Rejkuba1 - D. R. Silva3 - M. Kissler-Patig1 - L. E. Tacconi-Garman1 - S. S. Larsen4

1 - ESO, Karl-Schwarzschild-Str. 2, 85748 Garching bei

München, Germany

2 - Space Telescope European Coordinating

Facility, Karl-Schwarzschild-Str. 2, 85748 Garching bei

München, Germany

3 - National Optical Astronomy Observatory, 950 North Cherry Ave., Tucson, AZ, 85719, USA

4 - Astronomical Institute, University of Utrecht, Princetonplein 5, 3584 CC, Utrecht, The Netherlands

Received 31 July 2009 / Accepted 6 October 2009

Abstract

Current stellar population models have arguably the largest

uncertainties in the near-IR wavelength range, partly due to a lack

of large and well calibrated empirical spectral libraries. In this

paper we present a project whose aim it is to provide the first

library of luminosity weighted integrated near-IR spectra of

globular clusters to be used to test the current stellar population

models and serve as calibrators for future ones. Our pilot study

presents spatially integrated K-band spectra of three old

(![]() 10 Gyr) and metal poor ([Fe/H]

10 Gyr) and metal poor ([Fe/H] ![]() ), and three

intermediate age (1-2 Gyr) and more metal rich

([Fe/H]

), and three

intermediate age (1-2 Gyr) and more metal rich

([Fe/H]

![]() )

globular clusters in the LMC. We measured the

line strengths of the New A, Ca I and 12CO (2-0) absorption

features. The New A index decreases with increasing age and

decreasing metallicity of the clusters. The

)

globular clusters in the LMC. We measured the

line strengths of the New A, Ca I and 12CO (2-0) absorption

features. The New A index decreases with increasing age and

decreasing metallicity of the clusters. The

![]() index, used to

measure the 12CO (2-0) line strength, is significantly reduced by the

presence of carbon-rich TP-AGB stars in the globular clusters with

age

index, used to

measure the 12CO (2-0) line strength, is significantly reduced by the

presence of carbon-rich TP-AGB stars in the globular clusters with

age ![]() 1 Gyr.

This is in contradiction to the predictions of the stellar population

models of Maraston (2005, MNRAS, 362, 799). We find that this

disagreement is due to the different CO absorption strength of

carbon-rich Milky Way TP-AGB stars used in the models and the LMC

carbon stars in our sample. For globular clusters with age

1 Gyr.

This is in contradiction to the predictions of the stellar population

models of Maraston (2005, MNRAS, 362, 799). We find that this

disagreement is due to the different CO absorption strength of

carbon-rich Milky Way TP-AGB stars used in the models and the LMC

carbon stars in our sample. For globular clusters with age ![]() 2 Gyr we find

2 Gyr we find

![]() index measurements consistent with the

model predictions.

index measurements consistent with the

model predictions.

Key words: Magellanic Clouds - stars: carbon - galaxies: star clusters

1 Introduction

Since the 1990s, the interpretation of the integrated light of galaxies (in the nearby universe or at high redshift) relies heavily on evolutionary population synthesis (EPS) models. Such models were pioneered by Tinsley (1980) and the method has been extended since then (e.g. Schiavon 2007; Worthey 1994; Bruzual & Charlot 1993; Fioc & Rocca-Volmerange 1997; Maraston 2005; Leitherer et al. 1999; Vazdekis et al. 1996). They are used to determine ages, element abundances, stellar masses, stellar mass functions, etc., of those stellar populations that are not resolvable into single stars with current instrumentation, i.e. most of the universe outside the Local Group. To build such EPS models we use simple stellar populations (SSP). There are two essential advantages of focusing on SSPs. First, SSPs can be reliably calibrated. They can be compared directly with nearby globular cluster (GC) data for which accurate ages and element abundances are independently known from studies of the resolved stars. This step is crucial to fix the stellar population model parameters that are used to describe model input physics and which cannot be derived from first principles (e.g., convection, mass loss and mixing). Second, SSPs can be used to build more complex stellar systems. Systems made up by various stellar generations can be modelled by convolving SSPs with the adopted star formation history (e.g. Bruzual & Charlot 2003; Kodama & Arimoto 1997). Models describing accurately the integrated light properties, including medium to high resolution spectra and/or line-strength indices, are and will be our main tool to investigate and analyse the star-formation history over cosmological time-scales.

Table 1: Target globular clusters in the LMC - observing log.

This approach has worked well in the optical spectroscopic regime and

has led to well calibrated models (e.g. Thomas et al. 2003; Bruzual & Charlot 2003; Maraston 2005).

With the application of such models to observed spectra we derive

reasonable estimates of the main stellar population parameters (age,

chemical composition and M/L ratio) in the nearby universe

(e.g., Trager et al. 2000; Cappellari et al. 2006; Kuntschner 2000; Sánchez-Blázquez et al. 2007; Thomas et al. 2005) as well as

at higher redshifts (e.g., Sánchez-Blázquez et al. 2009; Maraston 2005; Bernardi et al. 2005). Of

course, uncertainties remain

due to the degeneracy of age and

metallicity effects in the optical wavelength range (e.g., Worthey 1994). The integrated near-IR light in stellar populations with

ages ![]() 1 Gyr is dominated by one stellar component, cool giant

stars, whose colour and line indices are mainly driven by one

parameter: metallicity (Frogel et al. 1978). Near-IR colours and indices

also have the advantage of being more nearly mass-weighted, i.e. the

near-IR mass-to-light ratio is closer to one (see e.g., Worthey 1994).

So, by combining the optical as well as near-IR

information one can resolve the currently remaining degeneracies

between age and chemical composition, present in the models, and hope

to gain a better understanding of star-formation histories. However,

currently available stellar population models have arguably the largest

uncertainties in the near-IR and thus it is of paramount importance to

provide high-quality observational data to validate and improve the

state-of-the-art models.

1 Gyr is dominated by one stellar component, cool giant

stars, whose colour and line indices are mainly driven by one

parameter: metallicity (Frogel et al. 1978). Near-IR colours and indices

also have the advantage of being more nearly mass-weighted, i.e. the

near-IR mass-to-light ratio is closer to one (see e.g., Worthey 1994).

So, by combining the optical as well as near-IR

information one can resolve the currently remaining degeneracies

between age and chemical composition, present in the models, and hope

to gain a better understanding of star-formation histories. However,

currently available stellar population models have arguably the largest

uncertainties in the near-IR and thus it is of paramount importance to

provide high-quality observational data to validate and improve the

state-of-the-art models.

Globular clusters in the Local Group are an ideal laboratory for this project since ample information from studies of the resolved stars is available. Yet, integrated spectroscopic observations of the Galactic GCs in the near-IR are very challenging due to their large apparent sizes on the sky. The Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC) and its globular cluster system, located about 50 kpc away, is a much better observational choice. It shows evidence for a very complex and still ongoing star formation activity. The LMC GCs have an advantage (for the scope of this project) with respect to Galactic GCs - they span a larger range in ages. Studies of the LMC globular cluster system show one old component with age >10 Gyr. After this time there was a ``dark age'' with just one cluster formed before a new burst of cluster formation that has started around 3-4 Gyr ago (Da Costa 1991). A disadvantage is their lower metallicity.

The goal of this project is to provide an empirical near-IR library of

spectra for integrated stellar populations with ages ![]() 1 Gyr,

which will be used to verify the predictions of current SSP models in

the near-IR wavelength range. Here we present the results from a pilot

study of K-band spectra of 6 globular clusters in the LMC. The

analysis of their J and H-band spectra will be discussed in a

separate paper. This paper is organised as follows: in

Sect. 2 we give details about the sample selection

and the observing strategy. Section 3 is devoted to the

observations and data reduction. In Sect. 4 we

discuss the cluster membership of the stars in our sample, in

Sect. 5 we describe the near-IR index measurement

procedures. In Sect. 6 we make a comparison

between the currently available stellar population models in the

near-IR with our data, discuss the observed disagreements, and give

potential explanations. Finally, in Sect. 7 we

give our concluding remarks.

1 Gyr,

which will be used to verify the predictions of current SSP models in

the near-IR wavelength range. Here we present the results from a pilot

study of K-band spectra of 6 globular clusters in the LMC. The

analysis of their J and H-band spectra will be discussed in a

separate paper. This paper is organised as follows: in

Sect. 2 we give details about the sample selection

and the observing strategy. Section 3 is devoted to the

observations and data reduction. In Sect. 4 we

discuss the cluster membership of the stars in our sample, in

Sect. 5 we describe the near-IR index measurement

procedures. In Sect. 6 we make a comparison

between the currently available stellar population models in the

near-IR with our data, discuss the observed disagreements, and give

potential explanations. Finally, in Sect. 7 we

give our concluding remarks.

Table 2: LMC globular cluster structural and photometric properties.

2 Sample selection and observational strategy

Due to our interests in the application of SSP models to the

integrated light of early-type galaxies, we restricted our sample in

this pilot study to intermediate age (1-2 Gyr) and old (>10 Gyr)

clusters. The sample was selected from the Bica et al. (1996,1999)

catalogues by choosing the SWB class (Searle et al. 1980) to be V, VI or

VII. In this way we ensured that the target systems will have ages

![]() 1 Gyr. We further required the clusters to be bright

(

1 Gyr. We further required the clusters to be bright

(

![]() )

and reasonably concentrated (effective radius

)

and reasonably concentrated (effective radius

![]()

![]() ). Where no literature data were available, the

concentration was checked by eye on DSS images. Another selection

criterion was the availability of auxiliary data, because we needed

detailed information on age and chemical composition. All of the

selected clusters have HST/WFPC2 and/or ACS imaging

(e.g. Mackey & Gilmore 2003; Olsen et al. 1998), integrated optical spectroscopy, and

spectra of individual giant stars (e.g. Johnson et al. 2006; Olszewski et al. 1991; Mucciarelli et al. 2008; Beasley et al. 2002). We can also benefit from near-IR

studies, both imaging and spectroscopy, of the giant stars in these

clusters (e.g. Frogel et al. 1990; Mucciarelli et al. 2006), as well as of photometry

(Mucciarelli et al. 2006; Pessev et al. 2006; Persson et al. 1983). Taking into account the above

criteria we selected six clusters as targets for this pilot project,

aiming at validating the strategy for observations and analysis (see

Table 1). Three of the clusters are metal

poor (mean [Fe/H]

). Where no literature data were available, the

concentration was checked by eye on DSS images. Another selection

criterion was the availability of auxiliary data, because we needed

detailed information on age and chemical composition. All of the

selected clusters have HST/WFPC2 and/or ACS imaging

(e.g. Mackey & Gilmore 2003; Olsen et al. 1998), integrated optical spectroscopy, and

spectra of individual giant stars (e.g. Johnson et al. 2006; Olszewski et al. 1991; Mucciarelli et al. 2008; Beasley et al. 2002). We can also benefit from near-IR

studies, both imaging and spectroscopy, of the giant stars in these

clusters (e.g. Frogel et al. 1990; Mucciarelli et al. 2006), as well as of photometry

(Mucciarelli et al. 2006; Pessev et al. 2006; Persson et al. 1983). Taking into account the above

criteria we selected six clusters as targets for this pilot project,

aiming at validating the strategy for observations and analysis (see

Table 1). Three of the clusters are metal

poor (mean [Fe/H] ![]() )

and have ages of more than 10 Gyr. The

other three are more metal rich (mean [Fe/H]

)

and have ages of more than 10 Gyr. The

other three are more metal rich (mean [Fe/H] ![]() )

and younger,

with ages between 1 and 2 Gyr. In the literature there are different

age and metallicity estimates for the clusters in our sample,

depending on the methods used. Here we listed the ages based on SWB

types, given in Frogel et al. (1990) and a compilation of metallicities,

obtained from the literature. A summary of the clusters' properties is

given in Table 1.

)

and younger,

with ages between 1 and 2 Gyr. In the literature there are different

age and metallicity estimates for the clusters in our sample,

depending on the methods used. Here we listed the ages based on SWB

types, given in Frogel et al. (1990) and a compilation of metallicities,

obtained from the literature. A summary of the clusters' properties is

given in Table 1.

Integrated spectra of clusters with less than

![]() are

likely to be dominated by statistical fluctuations in the number of

bright AGB and RGB stars (e.g. Renzini 1998, for more details see

Sect. 4). These particular phases of

the stellar evolution are one of the main contributors to the

integrated light of an intermediate age stellar population in the

near-IR (e.g. Maraston 2005). To sample as much of the cluster

light in a reasonable observing time, we made a mosaic of

are

likely to be dominated by statistical fluctuations in the number of

bright AGB and RGB stars (e.g. Renzini 1998, for more details see

Sect. 4). These particular phases of

the stellar evolution are one of the main contributors to the

integrated light of an intermediate age stellar population in the

near-IR (e.g. Maraston 2005). To sample as much of the cluster

light in a reasonable observing time, we made a mosaic of

![]() VLT/SINFONI pointings (

VLT/SINFONI pointings (

![]() per

pointing with a 0

per

pointing with a 0

![]() 25 spatial sampling) centred on each

cluster. We estimated the total light sampled by the central mosaic

25 spatial sampling) centred on each

cluster. We estimated the total light sampled by the central mosaic

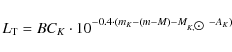

![]() for all clusters using the following equation and the 20

for all clusters using the following equation and the 20

![]() radius aperture K-band photometry:

radius aperture K-band photometry:

where mK is the observed K-band integrated magnitude of the cluster, (m-M)=18.5 is the adopted distance modulus to the LMC (Alves 2004; Borissova et al. 2004; van den Bergh 1998; Alves et al. 2002), AK is the extinction towards each cluster (Zaritsky et al. 1997),

In order to maximise the statistical probability of getting the

majority of the RGB and AGB stars, we observed, in addition to the

central mosaics, up to 9 of the brightest stars surrounding each

cluster and outside of the central mosaic. Their selection was based

on K - (J-K) colour-magnitude diagrams from the 2MASS Point Source

Catalogue (Skrutskie et al. 2006) of all the stars with reliable photometry and

located inside the tidal radius of each cluster (rt taken

from McLaughlin & van der Marel 2005, see Table 2). We selected

the stars with

(J-K) > 0.9 and

![]() as an initial

separation criterion from the LMC field population.

as an initial

separation criterion from the LMC field population.

The inclusion of these additional bright stars in our sample has a twofold purpose. The original idea, as described above, was to provide a better sampling of the integrated cluster light by in- or excluding these bright stars (after a careful decision process, based on kinematical and chemical composition assumptions). Second, the stars that turn out not to be members of any cluster are representative for the LMC field star population in the vicinity of our GCs. Thus we obtained an independent field AGB star sample for comparison with the globular clusters. The main properties of these additional stars are listed in Table 3.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=0,width=17cm,clip]{13041fg1.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/02/aa13041-09/Timg35.png)

|

Figure 1:

K-band 2MASS images of our cluster

sample. The black boxes and crosses represent our SINFONI

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

In Fig. 1 we show the 2MASS K-band images,

obtained from the 2MASS Extended Source Catalogue of our globular

cluster sample. The black cross and box on each cluster image match

the centre and the extent of the SINFONI mosaic coverage,

respectively. The red squares mark the additional bright stars,

observed around the clusters within the region of the 2MASS image.

The green circle and cross show the centre and 20

![]() radius

aperture, which Pessev et al. (2006) used to obtain integrated magnitudes

for each cluster. These authors have used near-IR images from the

2MASS Extended Source Catalogue and have performed photometry with

different aperture sizes after correcting for the extinction and LMC

field population. Mucciarelli et al. (2006) have used ESO 3.5 m NTT/SOFI images to

provide integrated near-IR magnitudes for half of the globular

clusters in our sample after correcting for the LMC field

population contamination, the extinction, and completeness. The

large yellow circles show their 90

radius

aperture, which Pessev et al. (2006) used to obtain integrated magnitudes

for each cluster. These authors have used near-IR images from the

2MASS Extended Source Catalogue and have performed photometry with

different aperture sizes after correcting for the extinction and LMC

field population. Mucciarelli et al. (2006) have used ESO 3.5 m NTT/SOFI images to

provide integrated near-IR magnitudes for half of the globular

clusters in our sample after correcting for the LMC field

population contamination, the extinction, and completeness. The

large yellow circles show their 90

![]() fixed radius aperture. We

used these photometric studies to compare our spectroscopy with

integrated colours and magnitudes. There is a good agreement between

the centres of our SINFONI observations and the photometry studies,

however, in the case of the sparsely populated cluster NGC 2173 the

offset is 17

fixed radius aperture. We

used these photometric studies to compare our spectroscopy with

integrated colours and magnitudes. There is a good agreement between

the centres of our SINFONI observations and the photometry studies,

however, in the case of the sparsely populated cluster NGC 2173 the

offset is 17

![]() (in all other cases this offset is smaller than

5

(in all other cases this offset is smaller than

5

![]() ).

).

A summary colour-magnitude diagram for all observed objects in our

sample, stars and central mosaics, is shown in

Fig. 2. For the J and K-band magnitude of the

central mosaics we adopted the 20

![]() radius aperture photometry

of Pessev et al. (2006), which, as shown in Fig. 1,

matches reasonably well our central mosaics. The selected of addition

bright stars outside the central mosaics are denoted with diamond

symbols. Their photometry comes from the 2MASS Point Source Catalogue

and magnitudes were dereddened following the same method as

Pessev et al. (2006) - extinction values were obtained from the

Magellanic Clouds Photometric Survey (Zaritsky et al. 1997) and adopting

the extinction law of Bessell & Brett (1988). The slanted line in this figure

represents the separation between oxygen- and carbon-rich giant stars

of Cioni et al. (2006). According to this criterion we have five carbon

rich stars in our sample.

radius aperture photometry

of Pessev et al. (2006), which, as shown in Fig. 1,

matches reasonably well our central mosaics. The selected of addition

bright stars outside the central mosaics are denoted with diamond

symbols. Their photometry comes from the 2MASS Point Source Catalogue

and magnitudes were dereddened following the same method as

Pessev et al. (2006) - extinction values were obtained from the

Magellanic Clouds Photometric Survey (Zaritsky et al. 1997) and adopting

the extinction law of Bessell & Brett (1988). The slanted line in this figure

represents the separation between oxygen- and carbon-rich giant stars

of Cioni et al. (2006). According to this criterion we have five carbon

rich stars in our sample.

3 Observations and data reduction

3.1 Observations

The observations of the selected globular clusters and stars were

obtained in service mode in the period October-December 2006

(Prog. ID 078.B-0205, PI: Kuntschner). We used the integral field unit

spectrograph SINFONI (Eisenhauer et al. 2003; Bonnet et al. 2004), which is mounted in the

Cassegrain focus of Unit Telescope 4 (Yepun) on VLT at Paranal La

Silla Observatory. Its gratings are in the near-IR spectral domain (1-2.5 ![]() m). We used the K-band grating, which covers the

wavelength range from 1.95 to 2.45

m). We used the K-band grating, which covers the

wavelength range from 1.95 to 2.45 ![]() m at a dispersion of

m at a dispersion of

![]() /pix. The spectral resolution around the centre of the

wavelength range is

/pix. The spectral resolution around the centre of the

wavelength range is

![]() (6.2 Å FWHM), as measured from

arc lamp frames. The largest single pointing with SINFONI covers

(6.2 Å FWHM), as measured from

arc lamp frames. The largest single pointing with SINFONI covers

![]() ,

which is too small even for the most compact

LMC clusters due to their relatively large apparent sizes on the sky.

To sample at least one effective radius of our targets we decided to

use a

,

which is too small even for the most compact

LMC clusters due to their relatively large apparent sizes on the sky.

To sample at least one effective radius of our targets we decided to

use a

![]() mosaic of the largest FoV of SINFONI, thus covering

the central

mosaic of the largest FoV of SINFONI, thus covering

the central

![]() for each cluster. Given the

goal to sample the total light, and not to get the best possible

spatial resolution, all the observations were performed in natural

seeing mode, i.e. with no adaptive optics correction. The integration

time was chosen based on the requirement to achieve a signal-to-noise

ratio of at least 50 in the final integrated spectra. The exposure

time for one pointing of the mosaic was 150 s, divided into three

integrations of 50 s, dithered by

for each cluster. Given the

goal to sample the total light, and not to get the best possible

spatial resolution, all the observations were performed in natural

seeing mode, i.e. with no adaptive optics correction. The integration

time was chosen based on the requirement to achieve a signal-to-noise

ratio of at least 50 in the final integrated spectra. The exposure

time for one pointing of the mosaic was 150 s, divided into three

integrations of 50 s, dithered by

![]() to reject bad

pixels. With the short integration time we could reliably measure and

subtract the very bright and variable near-IR night sky using the data

reduction procedure as described in the next section.

to reject bad

pixels. With the short integration time we could reliably measure and

subtract the very bright and variable near-IR night sky using the data

reduction procedure as described in the next section.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=0,width=8cm,clip]{13041fg2.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/02/aa13041-09/Timg42.png)

|

Figure 2: Colour-magnitude diagram including all the objects in our observational sample. The photometry of the six GCs (coloured square symbols) comes from the catalogue by Pessev et al. (2006). Data for the additional bright stars (diamond symbols) come from the 2MASS Point Source Catalogue (Skrutskie et al. 2006). Colour coding of the symbols for the bright stars matches the cluster in whose vicinity they were observed. Stars associated with the old clusters are likely not cluster members as discussed in Sect. 4.1. The slanted line shows the separation between oxygen-rich (leftwards) and carbon-rich (rightwards) stars of Cioni et al. (2006). |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Table 3: Additional bright RGB and AGB stars.

In order to correct for the effects of the night sky, we observed empty sky regions very close in time and space to our scientific observations, in a SOOOS sequence for each mosaic pointing (S - sky integration, O - object). For the additional bright stars outside the central mosaic we used the same sequence, but with shorter integration times of 10 s per individual integration, leading to a total on source time of 30 s. The sky fields for each cluster were located outside its tidal radius (see Table 2) and were checked by eye on 2MASS images to be devoid of bright stars. The total execution time for the longest observing sequence did not exceed 1.5 h. This ensured that the telluric correction, derived from the telluric stars, observed after each cluster and additional bright stars sequence (see Table 4) would be sufficiently accurate. The telluric stars were observed at similar airmass as the clusters.

3.2 Basic data reduction

An overview of the different data reduction steps and their results is shown in Fig. 3. There we show a sequence of a raw spectrum, then the sky subtracted spectrum, the telluric correction spectrum, and the final, fully reduced spectrum. More details about the data reduction can be found in Lyubenova (2009). Here we briefly discuss the most important steps.

The basic data reduction was performed with the ESO SINFONI Pipeline v. 1.9.2. Calibration products such as distortion maps, flat fields and bad pixel maps, were obtained with the relevant pipeline tasks (``recipes''). To reduce the clusters and additional star data, we divided each observing sequence into cluster frames (27 object plus 10 sky exposures) and star frames (3 star exposures plus one sky per star). This was needed due to the different integration times for these two sub-sets. We also preferred to reduce each mosaic pointing separately and combine the nine later. In this way we controlled the quality of each on-source frame sky correction and, where needed, we tuned some of the parameters in the pipeline. In summary, we fed the sinfo_rec_jitter recipe with data sets, consisting of one mosaic pointing (3 on source integrations plus 2 bracketing ``skies'') and the needed calibration files. Then the recipe extracts the raw data, applies distortion, bad pixels and flat-field corrections, wavelength calibration, and stores the combined sky-subtracted spectra in a 3-dimensional data cube. The same pipeline steps were also used to reduce the observations of the additional bright stars and telluric stars.

The main difficulty during the sky correction arises from the fact that our observations were sky dominated, combined with the small amount of flux in some of the frames. For these cases we found that by appropriately setting the parameters that indicate the edges of the object spectrum location (-skycor-llx, -skycor-lly, -skycor-urx and -skycor-ury), we could achieve a good sky correction.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=0,width=8cm,clip]{13041fg3.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/02/aa13041-09/Timg83.png)

|

Figure 3: Overview of the data reduction steps, applied to obtain fully reduced spectra (in this case, the LMC globular cluster NGC 2173). From top to bottom: (1) Raw spectrum, (2) Sky subtracted spectrum after running the SINFONI pipeline. (3) Telluric correction, used to remove the telluric absorption features. (4) Fully reduced spectrum, used for analysis. All data reduction steps were performed on the full data cubes and after the telluric correction, integrated spectra were derived. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

3.3 Telluric corrections

The next data reduction step was to remove the absorption features

originating in the Earth's atmosphere. These features are especially

deep in the blue part of the K-band (blue-wards of 2.1 ![]() m). For

this purpose we observed after each science target a telluric star,

which is of hotter spectral type (usually A-B dwarfs, see

Table 4). Since these stars are hot

stars, we know that their continuum in the K-band is well

approximated by the Rayleigh-Jeans part of the black body spectrum,

associated with their effective temperature. They show only one

prominent feature, the hydrogen Brackett

m). For

this purpose we observed after each science target a telluric star,

which is of hotter spectral type (usually A-B dwarfs, see

Table 4). Since these stars are hot

stars, we know that their continuum in the K-band is well

approximated by the Rayleigh-Jeans part of the black body spectrum,

associated with their effective temperature. They show only one

prominent feature, the hydrogen Brackett ![]() absorption line at

absorption line at

![]() m. For each telluric star spectrum first we modelled this

line with a Lorentzian profile, with the help of the IRAF task splot,

and then subtracted the model from the star's spectrum. Then

we divided the cleaned star spectrum by a black body spectrum with the

same temperature as the star to remove its continuum shape. Doing so,

we

obtained a normalised telluric spectrum. The last step before applying

it to the science spectra was to scale and shift in the dispersion

direction each telluric spectrum for each data cube by a small amount

(<0.5 pix, 1 pix = 2.45 Å) to minimise the

residuals of the

telluric lines (for more details about this procedure see Silva

et al. 2008). After that, each individual cluster mosaic and star

data

cube was divided by the optimised telluric spectrum. In this way we

also achieved a relative flux calibration.

m. For each telluric star spectrum first we modelled this

line with a Lorentzian profile, with the help of the IRAF task splot,

and then subtracted the model from the star's spectrum. Then

we divided the cleaned star spectrum by a black body spectrum with the

same temperature as the star to remove its continuum shape. Doing so,

we

obtained a normalised telluric spectrum. The last step before applying

it to the science spectra was to scale and shift in the dispersion

direction each telluric spectrum for each data cube by a small amount

(<0.5 pix, 1 pix = 2.45 Å) to minimise the

residuals of the

telluric lines (for more details about this procedure see Silva

et al. 2008). After that, each individual cluster mosaic and star

data

cube was divided by the optimised telluric spectrum. In this way we

also achieved a relative flux calibration.

One telluric star, HD 44533, used for the telluric correction of

NGC 2019 and its surrounding stars, has an unusual shape of the

Brackett ![]() line. It seems also to show some emission together

with the absorption. To remove it, we interpolated linearly the region

between 2.1606 and 2.1706

line. It seems also to show some emission together

with the absorption. To remove it, we interpolated linearly the region

between 2.1606 and 2.1706 ![]() m. In this region there are not many

strong telluric lines, but this interpolation will reflect in an

imperfect correction of the science spectra for this cluster at the

above wavelengths. However, none of the spectral features of interest

for this study lie in this wavelength range.

m. In this region there are not many

strong telluric lines, but this interpolation will reflect in an

imperfect correction of the science spectra for this cluster at the

above wavelengths. However, none of the spectral features of interest

for this study lie in this wavelength range.

Table 4: LMC telluric stars observing log.

3.4 Cluster light integration

As a result of the previous data reduction steps, we obtained fully calibrated data cubes for each SINFONI pointing, where the signatures of the instrument and the night sky are removed as much as possible. During the next step we reconstructed the full mosaic of each cluster. For example, Fig. 4 shows the reconstructed image of the cluster NGC 1754, together with a 2MASS K-band image for comparison. In this image we still see the imprints of the edges of the individual mosaic tiles. In both images, the 2MASS and even more so in the SINFONI image, we see individual stars, which can be extracted and studied separately.

However, here we are interested in luminosity weighted, integrated

spectra for each cluster, to compare with stellar population

models. To construct one integrated spectrum per cluster, we first

estimated the noise level in each reconstructed image from the mosaic

data cube. We considered that this noise is due to residuals after the sky

background correction. Thus, we computed the median residual sky noise

level and its standard deviation, after clipping all data points with

intensities of more than 3![]() (assuming that these are the pixels

that contain the star light from the cluster). We then selected

all spaxels, which have an intensity more than three times the standard

deviation above the median residual sky noise level. We summed them

and normalised the result to a 1 s exposure time. In some of the spectra

(NGC 1754 and NGC 2019), we still suffered from sky line residuals,

originating from the addition of imperfectly sky-corrected spaxels

(this may happen with intrinsically low intensity spaxels). In these

cases we interpolated the contaminated regions.

(assuming that these are the pixels

that contain the star light from the cluster). We then selected

all spaxels, which have an intensity more than three times the standard

deviation above the median residual sky noise level. We summed them

and normalised the result to a 1 s exposure time. In some of the spectra

(NGC 1754 and NGC 2019), we still suffered from sky line residuals,

originating from the addition of imperfectly sky-corrected spaxels

(this may happen with intrinsically low intensity spaxels). In these

cases we interpolated the contaminated regions.

Our observations were carried out in service mode with constraint sets

allowing seeing up to 2

![]() .

For the individual stars this led to

a failure of the standard pipeline recipe while extracting

1D spectra. Moreover, in some cases in the field-of-view there

were also

other stars. Thus we decided to manually control the selection of star

light spaxels. We used the same method as for the central clusters

mosaics to obtain the spectra of the additional stars.

.

For the individual stars this led to

a failure of the standard pipeline recipe while extracting

1D spectra. Moreover, in some cases in the field-of-view there

were also

other stars. Thus we decided to manually control the selection of star

light spaxels. We used the same method as for the central clusters

mosaics to obtain the spectra of the additional stars.

3.5 Error handling

The SINFONI pipeline does not provide error estimates, which carry

information about the error propagation during the different data

reduction procedures. Thus we have to use empirical ways of computing

the errors. For this purpose, we derived a wavelength dependent

signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) for each cluster integrated spectrum using

the empirical method described by Stoehr et al. (2007). We computed the

S/N in 200 pixel width bins from the science spectra (corresponding

to 0.049 ![]() m wavelength intervals). Then we fitted a linear

function to the S/N values in the range 2.1-2.4

m wavelength intervals). Then we fitted a linear

function to the S/N values in the range 2.1-2.4 ![]() m where all

of the spectral features of interest reside. The error spectrum for

each cluster and star was derived by dividing the science spectrum by

the prepared S/N function. The selection of the bin width was made

after experimenting with a few smaller and larger values. In the case

of bin widths of 50 or 100 pixels (0.01225 or 0.0245

m where all

of the spectral features of interest reside. The error spectrum for

each cluster and star was derived by dividing the science spectrum by

the prepared S/N function. The selection of the bin width was made

after experimenting with a few smaller and larger values. In the case

of bin widths of 50 or 100 pixels (0.01225 or 0.0245 ![]() m,

respectively), the S/N function becomes very noisy. Choosing wider,

300 or 400 pixels bins flattens the features of the S/N function. In

general the S/N decreases with increasing wavelength. This is due to

the combination of the spectral energy distribution and the instrument

+ telescope sensitivity. The mean S/N around 2.3

m,

respectively), the S/N function becomes very noisy. Choosing wider,

300 or 400 pixels bins flattens the features of the S/N function. In

general the S/N decreases with increasing wavelength. This is due to

the combination of the spectral energy distribution and the instrument

+ telescope sensitivity. The mean S/N around 2.3 ![]() m

is larger than 50 for the integrated spectra over the central mosaics

of the clusters and in the range 10-40 for the individual stars,

depending on their magnitude. The S/N estimate for

carbon star spectra is a lower limit due to the numerous absorption

features due to carbon based molecules, which are interpreted by the

routine as noise. The error spectra were used to estimate the errors of

the index measurements, as shown in the plots in this

paper.

m

is larger than 50 for the integrated spectra over the central mosaics

of the clusters and in the range 10-40 for the individual stars,

depending on their magnitude. The S/N estimate for

carbon star spectra is a lower limit due to the numerous absorption

features due to carbon based molecules, which are interpreted by the

routine as noise. The error spectra were used to estimate the errors of

the index measurements, as shown in the plots in this

paper.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=0,width=8.8cm,clip]{13041fg4.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/02/aa13041-09/Timg87.png)

|

Figure 4:

Two views of NGC 1754 in the

K-band. The left image is from the 2MASS Extended Source Catalogue

(Skrutskie et al. 2006). The white square marks the field that our SINFONI

mosaic observations cover (

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

4 Additional bright AGB stars - cluster members or not?

As discussed in Sect. 2, one of the main problems,

when one tries to compile a representative integrated spectrum of a

globular cluster, is the stochastic sampling of bright AGB stars for

clusters with modest luminosities. As an example, Renzini (1998)

shows that a stellar cluster with

![]() ,

solar metallicity

and age of 15 Gyr will have about 1200 red giant branch stars

(RGB), 30 early asymptotic giant branch stars (E-AGB), and only 2

thermally pulsating asymptotic giant branch (TP-AGB) stars. The

latter stellar evolutionary phase is particularly important for intermediate age stellar populations of

,

solar metallicity

and age of 15 Gyr will have about 1200 red giant branch stars

(RGB), 30 early asymptotic giant branch stars (E-AGB), and only 2

thermally pulsating asymptotic giant branch (TP-AGB) stars. The

latter stellar evolutionary phase is particularly important for intermediate age stellar populations of ![]() 1 Gyr, since up to 80% of their total K-band light originates there (e.g. Maraston 2005, and references therein). In general, the old clusters (NGC 1754, NGC 2005 and NGC 2019) are massive and well

concentrated, with half-light radii sampled with our SINFONI central

mosaics. Therefore our observations sample >50% of the total

bolometric light coming from these clusters, and in all cases we

sample at least

1 Gyr, since up to 80% of their total K-band light originates there (e.g. Maraston 2005, and references therein). In general, the old clusters (NGC 1754, NGC 2005 and NGC 2019) are massive and well

concentrated, with half-light radii sampled with our SINFONI central

mosaics. Therefore our observations sample >50% of the total

bolometric light coming from these clusters, and in all cases we

sample at least ![]()

![]() .

.

However, we were not performing that well with the intermediate age

clusters, where for two of them, NGC 2162 and NGC 2173, we sample

even less than

![]() (see

Table 2). Our observations are intrinsically

affected by statistical fluctuations in the number of bright stars,

due to the modest luminosities of the young clusters. These clusters

are less massive and less concentrated than other clusters in our

sample. In the more massive clusters, mass segregation has likely

caused a central concentration of the more massive main sequence

progenitors of the observed AGB stars than the lower mass background

stars that have not yet evolved off the main sequence. In the younger,

less massive clusters, mass segregation has likely been less

efficient. Hence, the AGB progenitors will be less centrally

concentrated relative to other unevolved stars. In turn, this implies

that AGB stars may be found at larger projected radii in lower mass

clusters than in higher mass clusters.

(see

Table 2). Our observations are intrinsically

affected by statistical fluctuations in the number of bright stars,

due to the modest luminosities of the young clusters. These clusters

are less massive and less concentrated than other clusters in our

sample. In the more massive clusters, mass segregation has likely

caused a central concentration of the more massive main sequence

progenitors of the observed AGB stars than the lower mass background

stars that have not yet evolved off the main sequence. In the younger,

less massive clusters, mass segregation has likely been less

efficient. Hence, the AGB progenitors will be less centrally

concentrated relative to other unevolved stars. In turn, this implies

that AGB stars may be found at larger projected radii in lower mass

clusters than in higher mass clusters.

In order to have integrated spectra as representative of our globular clusters, including the most important stellar evolutionary phases, we observed a number of additional bright stars with near-IR colours and magnitudes in the range expected for RGB and AGB stars, as explained in the previous sections. After probing their membership, we added some of them to the central mosaic cluster light to obtain the final integrated spectra, as explained bellow. We have added only integer numbers of bright stars. This is useful when one aims to obtain a representative spectrum for a given globular cluster, which was our goal in this project. In order to achieve an integrated spectrum representative of a full stellar population with a given age and chemical composition, where stochastic effects do not play a role, one should also consider adding fractional numbers of bright AGB stars.

The first criterion for cluster membership of the stars is the

proximity to the cluster centre, but an LMC field star might also have

a relatively nearby position due to projection effects. The

second possibility is to explore the radial velocities of the nearby

stars and the cluster under study. For this purpose we also need to

know the observed velocity dispersions of the stars in the

clusters. Due to the low velocity resolution of our observations, we

used data from the literature. For the old clusters (NGC 1754,

NGC 2005 and NGC 2019) we

took these values from the study of Dubath et al. (1997). They

measured core velocity dispersions from integrated optical spectra,

covering the central

![]() of each cluster. The

values are

of each cluster. The

values are

![]()

![]() for NGC 1754,

8.1

for NGC 1754,

8.1 ![]() 1.3

1.3

![]() for NGC 2005 and

for NGC 2005 and

![]()

![]() for

NGC 2019. For the intermediate-age clusters we could not find similar

observed velocity dispersions in the literature, thus we used the

predicted line-of-sight velocity dispersion at the centre of the

cluster by McLaughlin & van der Marel (2005). The numbers are 1.1

for

NGC 2019. For the intermediate-age clusters we could not find similar

observed velocity dispersions in the literature, thus we used the

predicted line-of-sight velocity dispersion at the centre of the

cluster by McLaughlin & van der Marel (2005). The numbers are 1.1

![]() for

NGC 2162 and 2.0

for

NGC 2162 and 2.0

![]() for NGC 2173. We did not find a similar

estimate for NGC 1806, so we used a conservative upper limit of

8

for NGC 2173. We did not find a similar

estimate for NGC 1806, so we used a conservative upper limit of

8

![]() .

.

4.1 Old clusters

In the case of the three old clusters, NGC 1754, NGC 2005 and

NGC 2019, we cannot exclude any star around any cluster, because their

velocities are consistent with cluster membership. This is due to the

insufficient velocity resolution of our observations. However, some of

the brightest stars that we have observed are located closer to the

tidal radii of the clusters than to their centres. This is not

expected for old clusters, which already have undergone a core

collapse and have their most massive stars concentrated towards the

centre of the cluster. Indeed, Mackey & Gilmore (2003) classify the old

clusters in our sample as potential post-core-collapse clusters, due

to the very well expressed power-law cusps in their centres. Moreover,

in Fig. 2 the (J-K) colours of the central mosaics

are much bluer than the colours of the additional bright stars around

the old clusters. Santos & Frogel (1997)

point out that very young and not massive clusters can be

systematically bluer than average due to stochastic sampling of the

IMF. However, the integrated spectra of the three old globular clusters

discussed here sample several times

![]() and have ages of

and have ages of ![]() 10 Gyr. In this regime the simulations of Santos & Frogel (1997) predict much less fluctuation in the (J-K)

colour than the observed difference between the central mosaics and the

additional stars. This additionally led us to the conclusion that these

stars are not likely to be cluster members. In the following we

considered them as members of the LMC field population. The bright

star marked with a red square just outside the SINFONI field-of-view

for NGC 1754 in Fig. 1 might be a cluster

member, but the S/N of its spectrum is too low (

10 Gyr. In this regime the simulations of Santos & Frogel (1997) predict much less fluctuation in the (J-K)

colour than the observed difference between the central mosaics and the

additional stars. This additionally led us to the conclusion that these

stars are not likely to be cluster members. In the following we

considered them as members of the LMC field population. The bright

star marked with a red square just outside the SINFONI field-of-view

for NGC 1754 in Fig. 1 might be a cluster

member, but the S/N of its spectrum is too low (![]() 10) and adding

it to the final integrated cluster spectrum would not increase the

total S/N.

10) and adding

it to the final integrated cluster spectrum would not increase the

total S/N.

4.2 Intermediate age clusters

This sub-sample includes the clusters NGC 1806, NGC 2162 and

NGC 2173. The last two of them are poorly populated, as seen in

near-IR light, visible in Fig. 1, so in their

cases the potential inclusion of additional bright stars in the

central mosaic is very important for the total cluster light

sampling. A detailed photometric study of the RGB and AGB stars in

these clusters is available from Mucciarelli et al. (2006). Based on near-IR

colour-magnitude diagrams and after removing contamination of the field

population, they report several stars in these evolutionary

phases, as well as their luminosity contribution to the total light of

the clusters. They consider all stars brighter than

![]() ,

which represents the level of the RGB tip (Ferraro et al. 2004), and

(J-K) between 0.85 and 2.1 to be AGB stars.

,

which represents the level of the RGB tip (Ferraro et al. 2004), and

(J-K) between 0.85 and 2.1 to be AGB stars.

The AGB stars separate in oxygen rich (M-stars) and carbon rich (C-stars). An AGB star becomes C-rich when the amount of dredged up carbon in the stellar envelope exceeds the amount of oxygen. Then all the oxygen is bound in CO molecules. The remaining carbon is used to form CH, CN and C2 molecules. This process is more effective in more metal-poor stellar populations, thus they are expected to have more C-stars (Maraston 2005). C-stars can contribute up to 60% of the total luminosity of metal-poor clusters (Frogel et al. 1990). Another important statement that Frogel et al. (1990) make is that C and M type stars are found both in clusters and in the LMC field. Thus it is very difficult to separate intermediate age globular cluster stars from the field population.

However, the LMC field carbon star contamination is not expected to

be significant at the locations of the globular clusters in our

sample. The upper limits, according to the carbon star frequency maps

of Blanco & McCarthy (1983), are of the order of 0.05 to 0.7 C-type stars for

an area with a radius of 100

![]() .

.

Mucciarelli et al. (2006) point out the presence of 75 RGB stars and 9 AGB stars,

of which 4 are carbon rich stars, in a radius of 90

![]() from

the centre of the cluster. Indeed, investigating the spectra of the

resolved stars in our SINFONI central mosaic data cube for this

cluster, we identified one of the stars as C-type. The first three of

the brightest additional stars within 90

from

the centre of the cluster. Indeed, investigating the spectra of the

resolved stars in our SINFONI central mosaic data cube for this

cluster, we identified one of the stars as C-type. The first three of

the brightest additional stars within 90

![]() are also of

C-type. Thus we chose to integrate all the stars within the radius

used by Mucciarelli et al. (2006), with the exception of the three faintest stars

due to their low S/N spectra.

are also of

C-type. Thus we chose to integrate all the stars within the radius

used by Mucciarelli et al. (2006), with the exception of the three faintest stars

due to their low S/N spectra.

NGC 2162: Inside the aperture photometry radius of 90

![]() that Mucciarelli et al. (2006) used, there is a very bright carbon star with

K=9.60m and

(J-K)=1.80 (see

Table 3). It is visible in

Fig. 1 at

that Mucciarelli et al. (2006) used, there is a very bright carbon star with

K=9.60m and

(J-K)=1.80 (see

Table 3). It is visible in

Fig. 1 at ![]() 50

50

![]() northwest of the cluster centre. If this star is a cluster member, it would be responsible for

northwest of the cluster centre. If this star is a cluster member, it would be responsible for ![]() 60% of the total K-band

cluster light and will significantly affect the integrated spectral

properties of the cluster, thus it is very important to carefully

evaluate its cluster membership. The velocity of this star is within

the errors the same as the velocity that we measured from the central

cluster mosaic.

However this is not a definitive proof of its membership, as discussed

above. Looking at the surface distribution maps of C- and M-type

giants across the LMC field in the study of Blanco & McCarthy (1983), we see

that NGC 2162 is located in a region far away from the LMC bar which

has the highest frequency of field carbon stars. According to these

maps, we can expect to have

60% of the total K-band

cluster light and will significantly affect the integrated spectral

properties of the cluster, thus it is very important to carefully

evaluate its cluster membership. The velocity of this star is within

the errors the same as the velocity that we measured from the central

cluster mosaic.

However this is not a definitive proof of its membership, as discussed

above. Looking at the surface distribution maps of C- and M-type

giants across the LMC field in the study of Blanco & McCarthy (1983), we see

that NGC 2162 is located in a region far away from the LMC bar which

has the highest frequency of field carbon stars. According to these

maps, we can expect to have ![]() 25 C-type stars in an area of

1 deg2. This density, scaled to the area covered by a circle

with a radius of 90

25 C-type stars in an area of

1 deg2. This density, scaled to the area covered by a circle

with a radius of 90

![]() ,

gives 0.05 carbon stars for the

,

gives 0.05 carbon stars for the

![]() deg2. Moreover, the control field that

Mucciarelli et al. (2006) used to estimate the LMC field contribution (shown in

their Fig. 4) does not contain any stars on the AGB redder than

(J-K)=1.2. Having bright carbon stars is not untypical for LMC

globular clusters with the age and metallicity of NGC 2162, as shown

by Frogel et al. (1990). With all these facts taken together, we conclude

that this very bright and red star is most probably a cluster member,

although its definite membership will be confirmed or rejected only by

high resolution spectroscopy. In order to obtain the final integrated

spectrum of NGC 2162, we have also added two more bright stars,

located within a 90

deg2. Moreover, the control field that

Mucciarelli et al. (2006) used to estimate the LMC field contribution (shown in

their Fig. 4) does not contain any stars on the AGB redder than

(J-K)=1.2. Having bright carbon stars is not untypical for LMC

globular clusters with the age and metallicity of NGC 2162, as shown

by Frogel et al. (1990). With all these facts taken together, we conclude

that this very bright and red star is most probably a cluster member,

although its definite membership will be confirmed or rejected only by

high resolution spectroscopy. In order to obtain the final integrated

spectrum of NGC 2162, we have also added two more bright stars,

located within a 90

![]() radius. The remaining stars in our

observational sample are fainter and their spectra have too low

quality. Thus they would not increase the total S/N.

radius. The remaining stars in our

observational sample are fainter and their spectra have too low

quality. Thus they would not increase the total S/N.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=0,width=9cm,clip]{13041fg5.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/02/aa13041-09/Timg97.png)

|

Figure 5:

A summary of the available photometric and

spectroscopic data about NGC 2173. The white square marks the

extent of the SINFONI mosaic. The red squares show the additional

bright stars we have observed with SINFONI. The cyan circles show

the stars with high resolution spectroscopy data from Mucciarelli et al. (2008)

(with numbers assigned as in this paper). The green circle shows the

aperture with 20

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

NGC 2173: Deciding about the cluster membership of the stars

observed around this cluster was easier, due to the

availability of high resolution spectroscopy of RGB stars in NGC 2173

from the study of Mucciarelli et al. (2008). As shown in Fig. 5,

we have three stars outside of and one within the central SINFONI mosaic

in common with their study. Based on high resolution

spectra Mucciarelli et al. (2008) find that these four stars have very similar

radial velocities (rms = 1.2

![]() )

and negligible star-to-star

scatter in the [Fe/H]. Thus we safely concluded that the first

three stars outside of the SINFONI mosaic are cluster members and we

included them in the final integrated spectrum for the cluster.

)

and negligible star-to-star

scatter in the [Fe/H]. Thus we safely concluded that the first

three stars outside of the SINFONI mosaic are cluster members and we

included them in the final integrated spectrum for the cluster.

Column 7 in Table 3 lists the stars, which we added to the final spectra for each globular cluster.

4.3 Cluster light sampling

Our study shows that with a reasonable number of mosaic tiles and no more than 1.5 h VLT observing time, we can sample a significant fraction of the light from each of our sample of LMC GCs. We have seen that for well concentrated clusters there is no need for additional light sampling, other than a central mosaic, covering at least the half-light radius. The strategy of observing a mosaic in the cluster's centre and then a sequence of the brightest and closest stars within a certain radius works very well in the case of sparse and not luminous clusters, as well as for those that are rich, but not well concentrated. However, there are still some doubts about the cluster membership of the brightest stars around the intermediate age clusters, especially in the case of carbon rich stars. For this reason we would need high resolution spectroscopy to measure their radial velocities and chemical composition and to compare them with other RGB stars.

Flux calibration of ground based spectroscopic data in the near-IR is

particularly difficult, thus we cannot rely on direct luminosity

estimates from our data. However, we can use the available photometry

of Mucciarelli et al. (2006) to estimate the approximate amount of sampled light

in the intermediate age clusters. In this study the authors provide

not only integrated magnitudes and colours, but also estimates of the

M- and C-type star contributions to the total cluster light in the

K-band. From there we know that the K-band light of NGC 2162 is

dominated by only one carbon rich star, which is responsible for

![]() 60% of the total cluster luminosity. This C-type star

contributes about 70% to our final integrated cluster

spectrum. From this we conclude that for this cluster we are missing

only

60% of the total cluster luminosity. This C-type star

contributes about 70% to our final integrated cluster

spectrum. From this we conclude that for this cluster we are missing

only ![]() 10% of the luminosity, measured by Mucciarelli et al. (2006). The

situation with the other two intermediate age clusters is

similar. NGC 1806 is quite rich in stars in comparison with the other

two clusters, as seen in the K-band images in

Fig. 1. According to Mucciarelli et al. (2006) 22% of the

total cluster light comes from stars with

K < 12.3m (AGB

stars). About 77% of it is due to four carbon stars. In our

NGC 1806 integrated spectrum these four C-type stars account for

10% of the luminosity, measured by Mucciarelli et al. (2006). The

situation with the other two intermediate age clusters is

similar. NGC 1806 is quite rich in stars in comparison with the other

two clusters, as seen in the K-band images in

Fig. 1. According to Mucciarelli et al. (2006) 22% of the

total cluster light comes from stars with

K < 12.3m (AGB

stars). About 77% of it is due to four carbon stars. In our

NGC 1806 integrated spectrum these four C-type stars account for

![]() 60%. Following Mucciarelli et al. (2006), 15% of the light in

NGC 2173 is due to one C-type star. In our spectrum this star is

responsible for

60%. Following Mucciarelli et al. (2006), 15% of the light in

NGC 2173 is due to one C-type star. In our spectrum this star is

responsible for ![]() 20%. For the three old and metal poor

clusters, such detailed estimates of the contributions from different

stellar phases are not available, thus we cannot make similar

estimates for them as for the intermediate age clusters. Our central

SINFONI mosaics cover more than one half-light radius. From this we conclude that the majority of the cluster light is covered.

20%. For the three old and metal poor

clusters, such detailed estimates of the contributions from different

stellar phases are not available, thus we cannot make similar

estimates for them as for the intermediate age clusters. Our central

SINFONI mosaics cover more than one half-light radius. From this we conclude that the majority of the cluster light is covered.

According to these rough estimates it is evident that we have reached our goal set up in Sect. 1, namely to obtain representative luminosity weighted, integrated spectra in the K-band for a group of clusters, having intermediate and old ages. The final spectra used for the scientific analysis in the following sections are shown in Fig. 6. The achieved signal-to-noise ratios are given in Table 5. The two clusters that have spectra dominated by carbon rich giants, NGC 1806 and NGC 2162, visually seem to have a significantly lower S/N than the other clusters. However, as mentioned in Sect. 3.5, this does not reflect the reality: these spectra are dominated by numerous absorption lines from carbon-based molecules, which the method for computing S/Ninterprets as noise. To properly estimate the S/N one would need synthetic spectra, including a full spectral synthesis. This is clearly not possible, as we are aiming to provide first templates that could allow computation of such spectra. We estimated the S/N for these two clusters based on the amount of integrated flux as compared to the other clusters in our sample and assigned to them a conservative lower limit of S/N > 80.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=0,width=8.5cm,clip]{13041fg6.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/02/aa13041-09/Timg98.png)

|

Figure 6: Final integrated spectra of the six LMC globular clusters used for analysis. The spectra of NGC 1806 and NGC 2162 are clearly dominated by carbon rich stars, evident from the numerous carbon based absorption features (e.g. C2, CH, CN) and the flatter continuum shape. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Table 5: K-band indices in LMC globular clusters.

5 Line strength indices in the K-band

The stellar population modelling technique allows us to obtain detailed estimates of the properties of integrated stellar populations by measuring, for example, the strengths of selected absorption or emission features in the spectra and comparing the measured values to the predicted ones. This approach has shown to be very effective in the optical wavelength range and a well established system, the Lick/IDS system (Trager et al. 1998; Faber et al. 1985; Worthey et al. 1994), is widely used. For the study of K-band spectral features several index definitions have been adopted (e.g. Mármol-Queraltó et al. 2008; Förster Schreiber 2000; Frogel et al. 2001; Silva et al. 2008). To measure the line strengths of New A and Ca I (see Fig. 6) we used the index definitions of Frogel et al. (2001), and for the strength of 12CO (2-0) the definitions of Mármol-Queraltó et al. (2008) and Maraston (2005).

The principle of measuring a near-IR index is the same as in the

optical Lick system. The value is computed as the ratio of the flux in

a central passband to the flux at the continuum level, measured in two

pseudo-continuum passbands on both sides of the central passband. Due

to the lack of a well defined continuum on the red side of the 12CO (2-0)

feature, the

![]() index that Mármol-Queraltó et al. (2008) defined uses two

continuum passbands on the blue side. This index measures the ratio

between the average fluxes in the continuum and the absorption

bands. Maraston (2005) uses a CO index, which measures the ratio

of the flux densities at 2.37 and 2.22

index that Mármol-Queraltó et al. (2008) defined uses two

continuum passbands on the blue side. This index measures the ratio

between the average fluxes in the continuum and the absorption

bands. Maraston (2005) uses a CO index, which measures the ratio

of the flux densities at 2.37 and 2.22 ![]() m, based on the

HST/NICMOS filters F237M and F222M. The index is computed in units of

magnitudes and is normalised to Vega. This index reflects the strength

not only of 12CO (2-0), but also of the other CO absorption features in the

range 2.3-2.4

m, based on the

HST/NICMOS filters F237M and F222M. The index is computed in units of

magnitudes and is normalised to Vega. This index reflects the strength

not only of 12CO (2-0), but also of the other CO absorption features in the

range 2.3-2.4 ![]() m (see Fig. 6).

m (see Fig. 6).

Prior to index measurements we broadened our spectra to a spectral

resolution of 6.9 Å (FWHM) to match the resolution of similar

earlier studies of the K-band light of early type galaxies and stars

obtained with VLT/ISAAC (Mármol-Queraltó et al. 2009; Silva et al. 2008). We measured the

recession velocities of the LMC globular clusters and stars with the

IRAF task fxcor and corrected for them. We did not apply

velocity dispersion corrections to the indices due to the very low

velocity dispersions of the clusters (< 10

![]() ,

see previous

section). The final index values are listed in

Table 5.

,

see previous

section). The final index values are listed in

Table 5.

The current stellar population models, which include the near-IR

wavelength range (e.g. Maraston 2005), have too low spectral

resolution at these wavelengths (![]() 200 Å FWHM) to be able to

give predictions for the weak and narrow features New A and

Ca I. Until more detailed models become available, we can only

empirically explore their dependance on the parameters of the globular

clusters, derived from resolved light studies.

200 Å FWHM) to be able to

give predictions for the weak and narrow features New A and

Ca I. Until more detailed models become available, we can only

empirically explore their dependance on the parameters of the globular

clusters, derived from resolved light studies.

In Fig. 7 we show the dependance of the New A and

Ca I index on the age of the clusters. We see that the

New A index increases with decreasing age of the cluster and

increasing metallicity. This result was suggested by

Silva et al. (2008), who find that the centres of early type galaxies in

the Fornax cluster with signatures of recent star formation,

i.e. stronger H![]() ,

also have stronger New A indices. The Ca I index

seems to show similar behaviour as

,

also have stronger New A indices. The Ca I index

seems to show similar behaviour as

![]() (discussed further in the text) as a function of age, albeit

with larger error bars.

(discussed further in the text) as a function of age, albeit

with larger error bars.

The 12CO (2-0) absorption feature at 2.29 ![]() m, which we described with

the

m, which we described with

the

![]() index, is much stronger and broader. Stellar population

model predictions for its strength exist and will be discussed in the

following section in more detail.

index, is much stronger and broader. Stellar population

model predictions for its strength exist and will be discussed in the

following section in more detail.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{13041fg7.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/02/aa13041-09/Timg115.png)

|

Figure 7: Near-IR index measurements plotted vs. the age of the clusters. Top panel: New A, Bottom panel: Ca I index. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

6 Comparisons with stellar population models

One of the goals of this project was to verify the predictions of the

current stellar population models in the near-IR wavelength range.

Such models are presented in Maraston (2005). The author

provides a full set of SEDs (spectral energy distributions) for

different stellar populations with ages from 103 yr to 15 Gyr

and covering a range of metallicities. These SEDs extend up to

2.5 ![]() m, but their spectral resolution in the near-IR wavelengths

is rather low, with one pixel covering 100 Å.

m, but their spectral resolution in the near-IR wavelengths

is rather low, with one pixel covering 100 Å.

The model predictions include the CO index, and for completeness we

measured the

![]() index as defined by Mármol-Queraltó et al. (2008). In order

to measure it for the models, we had to interpolate the model SEDs

linearly to a smaller wavelength step of 14 Å. We have chosen

this value after a few tests to check the stability of the

computation. Mármol-Queraltó et al. (2008) show that their

index as defined by Mármol-Queraltó et al. (2008). In order

to measure it for the models, we had to interpolate the model SEDs

linearly to a smaller wavelength step of 14 Å. We have chosen

this value after a few tests to check the stability of the

computation. Mármol-Queraltó et al. (2008) show that their

![]() index definition

is very little dependent on instrumental or internal velocity

broadening of the spectrum. However, the most extreme resolution they

tested is

index definition

is very little dependent on instrumental or internal velocity

broadening of the spectrum. However, the most extreme resolution they

tested is ![]() 70 Å (FWHM), while the resolution of the

model SEDs is

70 Å (FWHM), while the resolution of the

model SEDs is ![]() 200 Å (FWHM). We have measured the

200 Å (FWHM). We have measured the

![]() index in 10 stars from our sample with their nominal resolution and

when broadened to match the resolution of the models. The broadened

spectra have a

index in 10 stars from our sample with their nominal resolution and

when broadened to match the resolution of the models. The broadened

spectra have a

![]() index value, which is weaker by 0.04 with

respect to the unbroadened spectra. An offset with this size will not

to influence our general conclusions about the integrated spectra of

LMC GCs. This is further supported by the CO index values

of the GCs, which exhibit the same relative values compared to the

models. The CO index covers a very large wavelength range and is

little dependent on the spectral resolution. Thus we decided to

measure the

index value, which is weaker by 0.04 with

respect to the unbroadened spectra. An offset with this size will not

to influence our general conclusions about the integrated spectra of

LMC GCs. This is further supported by the CO index values

of the GCs, which exhibit the same relative values compared to the

models. The CO index covers a very large wavelength range and is

little dependent on the spectral resolution. Thus we decided to

measure the

![]() index at the nominal resolution of our spectra

(6.9 Å FWHM) and treat the model predictions with caution. Once

higher resolution models become available, this comparison should be

repeated in a more quantitative way. In the following subsection we

discuss the comparison between the models and the data. For clarity, we

divided the globular clusters in two groups. In

Sect. 6.1 we explore the three old and metal

poor clusters NGC 1754, NGC 2005 and NGC 2019. In

Sect. 6.2 we discuss the intermediate age

globular clusters NGC 1806, NGC 2162 and NGC 2173.

index at the nominal resolution of our spectra

(6.9 Å FWHM) and treat the model predictions with caution. Once

higher resolution models become available, this comparison should be

repeated in a more quantitative way. In the following subsection we

discuss the comparison between the models and the data. For clarity, we

divided the globular clusters in two groups. In

Sect. 6.1 we explore the three old and metal

poor clusters NGC 1754, NGC 2005 and NGC 2019. In

Sect. 6.2 we discuss the intermediate age

globular clusters NGC 1806, NGC 2162 and NGC 2173.

6.1 Old clusters

Literature data of the integrated near-IR colours of our sample of old

and metal poor clusters are shown in

Fig. 8 with open circles. The large open

symbols represent the colours, derived from 100

![]() radius

aperture photometry, the small open symbols from 20

radius

aperture photometry, the small open symbols from 20

![]() radius

aperture photometry from Pessev et al. (2006). With blue lines we have

overplotted SSP model predictions from Maraston (2005) for a Kroupa

IMF and blue horizontal branch morphology. The metallicity that is

closest to the one derived for our GCs sample is denoted with a solid

blue line, [Z/H] = - 1.35. In the top panel the data agree

reasonably well with the model (J-K) colour. In the bottom panel the

(H-K) colours show a larger spread.

radius

aperture photometry from Pessev et al. (2006). With blue lines we have

overplotted SSP model predictions from Maraston (2005) for a Kroupa

IMF and blue horizontal branch morphology. The metallicity that is

closest to the one derived for our GCs sample is denoted with a solid

blue line, [Z/H] = - 1.35. In the top panel the data agree

reasonably well with the model (J-K) colour. In the bottom panel the

(H-K) colours show a larger spread.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=0,width=8.5cm,clip]{13041fg8.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/02/aa13041-09/Timg116.png)

|

Figure 8:

Comparison of cluster

integrated colours with SSP model predictions from

Maraston (2005). The filled coloured circles (colour coding as

listed in the upper right corner of the top plot) correspond to the