| Issue |

A&A

Volume 510, February 2010

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A27 | |

| Number of page(s) | 14 | |

| Section | Galactic structure, stellar clusters, and populations | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/200913011 | |

| Published online | 03 February 2010 | |

Brown dwarfs and very low mass stars in the Praesepe open

cluster: a dynamically unevolved mass function?![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png) ,

,![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

S. Boudreault1 - C. A. L. Bailer-Jones1 - B. Goldman1 - T. Henning1 - J. A. Caballero2

1 - Max-Planck-Institut für Astronomie, Königstuhl 17, 69117 Heidelberg, Germany

2 - Departamento de Astrofísica, Facultad de Física, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, 28040 Madrid, Spain

Received 29 July 2009 / Accepted 23 October 2009

Abstract

Context. Determination of the mass functions of open

clusters of different ages allows us to infer the efficiency with which

brown dwarfs are evaporated from clusters to populate the field.

Aims. In this paper we present the results of a photometric

survey to identify low mass and brown dwarf members of the old open

cluster Praesepe (age 590

+150-120 Myr, distance 190

+6.0-5.8 pc) from which we estimate its mass function and compare this with that of other clusters.

Methods. We performed an optical (![]() -band) and near-infrared (J and

-band) and near-infrared (J and ![]() -band) photometric survey of Praesepe covering 3.1 deg2. With 5

-band) photometric survey of Praesepe covering 3.1 deg2. With 5![]() detection limits of

detection limits of

![]() and J = 20.0, our survey is predicted to be sensitive to objects with masses from 0.6 to 0.05

and J = 20.0, our survey is predicted to be sensitive to objects with masses from 0.6 to 0.05 ![]() .

.

Results. We photometrically identify 123 cluster member

candidates based on dust-free atmospheric models and 27 candidates

based on dusty atmospheric models. The mass function rises from

0.6 ![]() down to 0.1

down to 0.1 ![]() (a power law fit of the mass function gives

(a power law fit of the mass function gives

![]() ;

;

![]() (M)

(M)

![]() ), and then turns over at

), and then turns over at ![]() 0.1

0.1 ![]() .

This rise agrees with the mass function inferred by previous studies,

including a survey based on proper motion and photometry. In contrast,

the mass function differs significantly from that measured for the

Hyades, an open cluster with a similar age (

.

This rise agrees with the mass function inferred by previous studies,

including a survey based on proper motion and photometry. In contrast,

the mass function differs significantly from that measured for the

Hyades, an open cluster with a similar age (

![]() Myr).

Possible reasons are that the clusters did not have the same initial

mass function, or that dynamical evolution (e.g. evaporation of low

mass members) has proceeded differently in the two clusters. Although

different binary fractions could cause the observed (i.e. system) mass

functions to differ, there is no evidence for differing binary

fractions from measurements published in the literature. Of our cluster

candidates, six have masses predicted to be equal to or below the

stellar/substellar boundary at 0.072

Myr).

Possible reasons are that the clusters did not have the same initial

mass function, or that dynamical evolution (e.g. evaporation of low

mass members) has proceeded differently in the two clusters. Although

different binary fractions could cause the observed (i.e. system) mass

functions to differ, there is no evidence for differing binary

fractions from measurements published in the literature. Of our cluster

candidates, six have masses predicted to be equal to or below the

stellar/substellar boundary at 0.072 ![]() .

.

Key words: open clusters and associations: individual: Praesepe - stars: low-mass - stars: brown dwarfs - stars: luminosity function, mass function - stars: formation

1 Introduction

Several publications in the past decade have been concerned with the

mass function (MF) of low mass stellar and substellar populations in

open clusters, including ![]() Orionis (Béjar et al. 2002;

Caballero et al. 2007), the Orion Nebula Cluster

(Hillenbrand & Carpenter 2000; Slesnick et al. 2004), IC 2391

(Barrado y Navascués et al. 2004; Boudreault & Bailer-Jones 2009), the Pleiades

(Moraux et al. 2003; Lodieu et al. 2007), and the Hyades

(Reid & Hawley 1999; Bouvier et al. 2008), to name just a few.

Studies of relatively old open clusters

(age

Orionis (Béjar et al. 2002;

Caballero et al. 2007), the Orion Nebula Cluster

(Hillenbrand & Carpenter 2000; Slesnick et al. 2004), IC 2391

(Barrado y Navascués et al. 2004; Boudreault & Bailer-Jones 2009), the Pleiades

(Moraux et al. 2003; Lodieu et al. 2007), and the Hyades

(Reid & Hawley 1999; Bouvier et al. 2008), to name just a few.

Studies of relatively old open clusters

(age ![]() 100 Myr) are important for the following two reasons

in particular. First, they permit a study of the intrinsic evolution

of brown dwarfs (BDs), e.g. their luminosity and effective

temperature, which constrains structural and atmospheric models.

Second, together with younger clusters we can investigate how BD

populations as a whole evolve and thus probe the efficiency with which BDs

evaporate from clusters to populate the Galactic field. Numerical

simulations of cluster evolution have demonstrated that the MFs can

evolve through dynamical interaction (de la Fuente Marcos & de la Fuente Marcos 2000;

Adams et al. 2002b). These interactions result in a decrease of the

open cluster BD (and low-mass star) population. This has been

observed by Bouvier et al. (2008) from a comparison of the Pleiades

(120 Myr) and Hyades (625 Myr) mass functions.

100 Myr) are important for the following two reasons

in particular. First, they permit a study of the intrinsic evolution

of brown dwarfs (BDs), e.g. their luminosity and effective

temperature, which constrains structural and atmospheric models.

Second, together with younger clusters we can investigate how BD

populations as a whole evolve and thus probe the efficiency with which BDs

evaporate from clusters to populate the Galactic field. Numerical

simulations of cluster evolution have demonstrated that the MFs can

evolve through dynamical interaction (de la Fuente Marcos & de la Fuente Marcos 2000;

Adams et al. 2002b). These interactions result in a decrease of the

open cluster BD (and low-mass star) population. This has been

observed by Bouvier et al. (2008) from a comparison of the Pleiades

(120 Myr) and Hyades (625 Myr) mass functions.

Many earlier studies of the substellar MF have focused on young open

clusters with ages less than ![]() 100 Myr, and in many cases much

younger (<10 Myr). This is partly because BDs are bright when they

are young (lacking a significant nuclear energy source, they cool as

they age), thus easing detection of the least massive objects.

However, youth presents difficulties. First, intra-cluster extinction

plagues the determination of the intrinsic luminosity function from

the measured photometry. Second, at these ages the BD models have

large(r) uncertainties (Baraffe et al. 2002). Estimates of the substellar MF in very young clusters (age

100 Myr, and in many cases much

younger (<10 Myr). This is partly because BDs are bright when they

are young (lacking a significant nuclear energy source, they cool as

they age), thus easing detection of the least massive objects.

However, youth presents difficulties. First, intra-cluster extinction

plagues the determination of the intrinsic luminosity function from

the measured photometry. Second, at these ages the BD models have

large(r) uncertainties (Baraffe et al. 2002). Estimates of the substellar MF in very young clusters (age ![]() 1 Myr) might be

unreliable due to these modelling uncertainties

(Chabrier et al. 2005). BDs in older clusters suffer less from

these problems, but have the disadvantage that much deeper surveys are

required to detect them.

1 Myr) might be

unreliable due to these modelling uncertainties

(Chabrier et al. 2005). BDs in older clusters suffer less from

these problems, but have the disadvantage that much deeper surveys are

required to detect them.

The old open cluster Praesepe is an interesting target considering its

age and distance. It is located at a distance of

190

+6.0-5.8 pc (based on parallax measurements from the new

Hipparcos data reduction, van Leeuwen 2009) and has an age of

590

+150-120 Myr (by isochrone fitting in the

Hertzsprung-Russell diagram; Fossati et al. 2008). The extinction

towards this cluster is low,

![]() mag

(Taylor 2006), while determinations of the metallicity of

Praesepe yield some discrepancies: [Fe/H] =

mag

(Taylor 2006), while determinations of the metallicity of

Praesepe yield some discrepancies: [Fe/H] =

![]() ,

Friel & Boesgaard (1992); +

,

Friel & Boesgaard (1992); +

![]() ,

Boesgaard & Budge (1988);

,

Boesgaard & Budge (1988);

![]() from spectroscopy and

from spectroscopy and

![]() from photometry, An et al. (2007);

+

from photometry, An et al. (2007);

+

![]() ,

Pace et al. (2008). Hambly et al. (1995) presented a

,

Pace et al. (2008). Hambly et al. (1995) presented a

![]() 19 deg2 survey of the Praesepe cluster down to masses of

19 deg2 survey of the Praesepe cluster down to masses of

![]() 0.1

0.1 ![]() and observed a rise of the MF at the lowest

masses. They concluded that this implied a large

population of BDs. A shallow survey complete to I = 21.2 mag,

R = 22.2 mag over 800 arcmin2 uncovered one spectrally

confirmed very low-mass star or BD (spectral type of M8.5V) with a

model-dependent mass of 0.063-0.084

and observed a rise of the MF at the lowest

masses. They concluded that this implied a large

population of BDs. A shallow survey complete to I = 21.2 mag,

R = 22.2 mag over 800 arcmin2 uncovered one spectrally

confirmed very low-mass star or BD (spectral type of M8.5V) with a

model-dependent mass of 0.063-0.084 ![]() (Magazzú et al. 1998). A

survey over the central 1 deg2 with 10

(Magazzú et al. 1998). A

survey over the central 1 deg2 with 10![]() limits of

R = 21.5, I = 20.0 and Z = 21.5 mag revealed 19 BD

candidates and the first MF determination of Praesepe down to the

substellar limit, but without spectral confirmation

(Pinfield et al. 1997). Subsequent infrared photometry of the sample reduced this

number to nine candidates (Hodgkin et al. 1999). Adams et al. (2002a)

presented a 100 deg2 study of Praesepe using 2MASS (Two-Micron All

Sky Survey) data and Palomar survey photographic plates, from which they

derived proper motions. They determined the radial profile of this

cluster but their MF does not reach the substellar regime. A more

recent proper motion survey of Praesepe covers a much larger area

(300 deg2; Kraus & Hillenbrand 2007), but does not reach the BD regime

either (the limit is

limits of

R = 21.5, I = 20.0 and Z = 21.5 mag revealed 19 BD

candidates and the first MF determination of Praesepe down to the

substellar limit, but without spectral confirmation

(Pinfield et al. 1997). Subsequent infrared photometry of the sample reduced this

number to nine candidates (Hodgkin et al. 1999). Adams et al. (2002a)

presented a 100 deg2 study of Praesepe using 2MASS (Two-Micron All

Sky Survey) data and Palomar survey photographic plates, from which they

derived proper motions. They determined the radial profile of this

cluster but their MF does not reach the substellar regime. A more

recent proper motion survey of Praesepe covers a much larger area

(300 deg2; Kraus & Hillenbrand 2007), but does not reach the BD regime

either (the limit is ![]() 0.12

0.12 ![]() ). Finally, the most recent

substellar MF determination of Praesepe was published by

González-García et al. (2006) and extends to a 5

). Finally, the most recent

substellar MF determination of Praesepe was published by

González-García et al. (2006) and extends to a 5![]() detection limit

of i = 24.5 mag corresponding to 0.050-0.055

detection limit

of i = 24.5 mag corresponding to 0.050-0.055 ![]() .

They

identified one new substellar candidate, but their survey covers only

1177 arcmin2.

.

They

identified one new substellar candidate, but their survey covers only

1177 arcmin2.

In this paper, we present the results of a program to study, in

detail, the MF of Praesepe down to the substellar

regime. Our photometric survey is, as with González-García et al. (2006),

the deepest so far in optical and near-infrared (NIR) bands, with

5![]() detection limits of

detection limits of

![]() and J=20.0(corresponding to a mass limit of about 0.05

and J=20.0(corresponding to a mass limit of about 0.05 ![]() ), but covers

more than nine times the area. Our paper is structured as follows. We

first present the data set, reduction procedure and calibration in

Sect. 2. We then discuss our candidate selection

procedure in Sect. 3 and the survey results in Sect. 4 before discussing the derived MF in Sect. 5. We conclude in Sect. 6.

), but covers

more than nine times the area. Our paper is structured as follows. We

first present the data set, reduction procedure and calibration in

Sect. 2. We then discuss our candidate selection

procedure in Sect. 3 and the survey results in Sect. 4 before discussing the derived MF in Sect. 5. We conclude in Sect. 6.

2 Observations, data reduction, calibration, and estimation of masses and effective temperatures

2.1 Observations

Table 1: Description of observations with the O2k infrared camera.

Table 2: Description of observations with WFI optical camera.

Our survey consists of 47 Omega 2000 (O2k) fields each of size

![]() arcmin2 observed in J and

arcmin2 observed in J and ![]() ,

plus the

same region observed in nine

,

plus the

same region observed in nine ![]() Wide Field Imager (WFI)

fields each of size

Wide Field Imager (WFI)

fields each of size

![]() arcmin2. This gives a total

coverage of 3.1 deg2 observed in all three bands, centred on

RA(J2000) = 08

arcmin2. This gives a total

coverage of 3.1 deg2 observed in all three bands, centred on

RA(J2000) = 08![]() 40

40![]() 04

04![]() and Dec(J2000) = + 19

and Dec(J2000) = + 19![]() 40'00''.

40'00''.

The near-infrared (NIR) observations were made on the 3.5m telescope at Calar Alto,

Spain (with observation runs of several nights from February 2005 to

January 2007). O2k (Bailer-Jones et al. 2000; Baumeister et al. 2003)

comprises a HAWAII-2 detector with 2k ![]() 2k pixels over a field

of view of

2k pixels over a field

of view of

![]() arcmin delivering a pixel scale of 0.45 arcsec

per pixel. The optical observations were carried out with the Wide

Field Imager (WFI) on the MPG/ESO 2.2m telescope at La Silla, Chile

(Baade et al. 1999) during 17-22 March 2007. The WFI is a mosaic

camera of

arcmin delivering a pixel scale of 0.45 arcsec

per pixel. The optical observations were carried out with the Wide

Field Imager (WFI) on the MPG/ESO 2.2m telescope at La Silla, Chile

(Baade et al. 1999) during 17-22 March 2007. The WFI is a mosaic

camera of

![]() CCDs, each with 2k

CCDs, each with 2k ![]() 4k pixels,

covering a total field of view of

4k pixels,

covering a total field of view of

![]() arcmin2 at

0.238 arcsec per pixel. All fields were observed in the broad band

filter

arcmin2 at

0.238 arcsec per pixel. All fields were observed in the broad band

filter ![]() .

A detailed list of the fields observed with

pointing, filter, exposure time and 5

.

A detailed list of the fields observed with

pointing, filter, exposure time and 5![]() detection limits is

given in Table 1 for the NIR data and in

Table 2 for the optical data. The passband

functions for the filters, multiplied with the quantum efficiency of

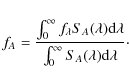

the detectors, are shown in Fig. 1.

detection limits is

given in Table 1 for the NIR data and in

Table 2 for the optical data. The passband

functions for the filters, multiplied with the quantum efficiency of

the detectors, are shown in Fig. 1.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{13011f01.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/02/aa13011-09/Timg42.png)

|

Figure 1:

Transmission curve of the filters used

in our survey compared to the synthetic spectrum of a BD with

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

2.2 Data reduction and astrometry

The standard data reduction steps (overscan subtraction, trimming and

flat-fielding for the WFI data; dark subtraction and flat-fielding for

O2k data) were performed on a nightly basis, using the ccdredpackage under IRAF![]() . For both WFI and O2k

data we used superflats (obtained by combining science image

frames for each night) for pixel-to-pixel variation correction and for

correcting the global illumination. For our NIR data, the sky

background was subtracted using the median-combined images for each

filter and each field (on a nightly basis). For WFI data, we reduced

each of the eight CCDs in the mosaic independently and in the final

step scaled them to a common flux response level. We made an initial

sky subtraction via a low-order fit to the optical data, and for the

infrared data by subtracting a median combination of all

(unregistered) images of the science frames. Fringes were visible for

the

. For both WFI and O2k

data we used superflats (obtained by combining science image

frames for each night) for pixel-to-pixel variation correction and for

correcting the global illumination. For our NIR data, the sky

background was subtracted using the median-combined images for each

filter and each field (on a nightly basis). For WFI data, we reduced

each of the eight CCDs in the mosaic independently and in the final

step scaled them to a common flux response level. We made an initial

sky subtraction via a low-order fit to the optical data, and for the

infrared data by subtracting a median combination of all

(unregistered) images of the science frames. Fringes were visible for

the ![]() -band photometry. They were removed in the way

described by Bailer-Jones & Mundt (2001)

-band photometry. They were removed in the way

described by Bailer-Jones & Mundt (2001)![]() . Finally, the individual images of a given field were

registered and median combined. We used the IRAF task daofind

to automatically detect stellar objects in an image by approximating

the stellar point spread function with a Gaussian. We

visually inspected the images in order to remove from our cluster

candidate list any extended sources (i.e. galaxies) that were

mistakenly identified as stars by daofind (see Sect. 3.3). Sources were extracted and instrumental

magnitudes assigned via aperture photometry with the IRAF task

wphot. To this aperture photometry we have applied an

aperture correction following the technique described in Howell (1989).

An astrometric solution was obtained using the IRAF package

imcoords and the tasks ccxymatch, ccmap and

cctran. For each WFI field, this solution was computed for

the

. Finally, the individual images of a given field were

registered and median combined. We used the IRAF task daofind

to automatically detect stellar objects in an image by approximating

the stellar point spread function with a Gaussian. We

visually inspected the images in order to remove from our cluster

candidate list any extended sources (i.e. galaxies) that were

mistakenly identified as stars by daofind (see Sect. 3.3). Sources were extracted and instrumental

magnitudes assigned via aperture photometry with the IRAF task

wphot. To this aperture photometry we have applied an

aperture correction following the technique described in Howell (1989).

An astrometric solution was obtained using the IRAF package

imcoords and the tasks ccxymatch, ccmap and

cctran. For each WFI field, this solution was computed for

the ![]() -band image (and for each O2k field using the J-band

image) using the 2MASS catalogue as a reference. The root mean square

accuracy of our astrometric solution is 0.15-0.20 arcsec for both WFI

and O2k data. For WFI data, the astrometry was performed on a

CCD-by-CCD basis.

-band image (and for each O2k field using the J-band

image) using the 2MASS catalogue as a reference. The root mean square

accuracy of our astrometric solution is 0.15-0.20 arcsec for both WFI

and O2k data. For WFI data, the astrometry was performed on a

CCD-by-CCD basis.

2.3 Photometric calibration

To correct for Earth-atmospheric absorption on the photometry, we

calibrated the infrared data using the J and ![]() -band magnitudes

of 2MASS objects which were observed in our science fields. By

determining a constant offset between the magnitude of 2MASS and our

instrumental magnitude, we obtained the zero point offset. Since this

zero point offset was obtained with objects in the same field of view

in each science frame, and since we found the difference between the

2MASS and O2k passbands to be insignificant, we did not need to

perform an airmass or colour correction when reducing our NIR

photometry. (That is, the determined coefficients were statistically

consistent with zero).

-band magnitudes

of 2MASS objects which were observed in our science fields. By

determining a constant offset between the magnitude of 2MASS and our

instrumental magnitude, we obtained the zero point offset. Since this

zero point offset was obtained with objects in the same field of view

in each science frame, and since we found the difference between the

2MASS and O2k passbands to be insignificant, we did not need to

perform an airmass or colour correction when reducing our NIR

photometry. (That is, the determined coefficients were statistically

consistent with zero).

We followed a similar approach for our ![]() -band photometry,

but using observations in our fields for which r and i-band

magnitudes are available in the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS)

catalogue. We first transformed the i-band magnitudes of SDSS to

-band photometry,

but using observations in our fields for which r and i-band

magnitudes are available in the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS)

catalogue. We first transformed the i-band magnitudes of SDSS to

![]() -band magnitudes using the transformation equation of

Jordi et al. (2006)

-band magnitudes using the transformation equation of

Jordi et al. (2006)

| (1) |

We then determined the zero point offset between this

2.4 Mass and effective temperature estimates based on photometry

After we identify candidates (Sect. 3) we will use the multiband

photometry to derive their masses and effective temperatures,

![]() .

We use the evolutionary tracks from Baraffe et al. (1998) and

atmosphere models from Hauschildt et al. (1999a) (assuming a dust-free

atmosphere; the NextGen model) to compute an isochrone for Praesepe

for an age of 590 Myr, a distance of 190 pc, a solar metallicity

and assuming zero extinction. These models and assumptions provide us

with a prediction of

.

We use the evolutionary tracks from Baraffe et al. (1998) and

atmosphere models from Hauschildt et al. (1999a) (assuming a dust-free

atmosphere; the NextGen model) to compute an isochrone for Praesepe

for an age of 590 Myr, a distance of 190 pc, a solar metallicity

and assuming zero extinction. These models and assumptions provide us

with a prediction of

![]() ,

the spectral energy distribution

received at the Earth (in erg cm-2 s-1 Å-1) from the

source. We need to convert these spectral energy distributions into magnitudes in the filters we used. Denoting as SA(

,

the spectral energy distribution

received at the Earth (in erg cm-2 s-1 Å-1) from the

source. We need to convert these spectral energy distributions into magnitudes in the filters we used. Denoting as SA(![]() )

the (known) total

transmission function of filter A (including the CCD quantum

efficiency and assuming telescope and instrumental throughput are

flat), then the flux measured in the filter is

)

the (known) total

transmission function of filter A (including the CCD quantum

efficiency and assuming telescope and instrumental throughput are

flat), then the flux measured in the filter is

The corresponding magnitude mA in the Johnson photometric system is given by

where cA is a constant (zero point) that remains to be determined in order to put the model-predicted magnitude onto the Johnson system. We derived this constant for each of the bands

Assuming that all our photometric candidates belong to Praesepe, we

derive masses and effective temperatures from these isochrones using

our three filter measurements in the following way. We first normalize

the energy distribution of each object to the energy distribution of

the model using the J filter. We then estimate the mass and

effective temperature via a least squares fit of the measured spectral

energy ``distribution'' (actually just two points) to the model

spectral energy distribution from the isochrone. This involves

estimating one parameter from two measurements, because mass and

![]() are not independent.

are not independent.

The above assumption of a dust-free atmosphere is valid for

![]()

![]() 3000 K, but objects with

3000 K

3000 K, but objects with

3000 K ![]()

![]()

![]() 1800 K are expected to

have dust in equilibrium with the gas phase (Allard et al. 2001). We

therefore perform a second selection of candidates (and determination

of mass and

1800 K are expected to

have dust in equilibrium with the gas phase (Allard et al. 2001). We

therefore perform a second selection of candidates (and determination

of mass and

![]() )

based on isochrones predicted in the same

way, but based on evolutionary tracks of Chabrier et al. (2000) and the

AMES-dusty model of Allard et al. (2001). This give us a second

dusty model list of candidates. A priori some observed stars

could appear in both lists (and in fact two do), but in our later

discussions of the mass function we do not mix stars from the two

lists but rather make separate determinations of the mass function.

)

based on isochrones predicted in the same

way, but based on evolutionary tracks of Chabrier et al. (2000) and the

AMES-dusty model of Allard et al. (2001). This give us a second

dusty model list of candidates. A priori some observed stars

could appear in both lists (and in fact two do), but in our later

discussions of the mass function we do not mix stars from the two

lists but rather make separate determinations of the mass function.

There are various sources of error in the estimation of mass

and

![]() .

These are the photon noise, the photometric

calibration, the least squares fitting (imperfect model) and the

uncertainties in the age of and distance to Praesepe. The uncertainties

in the age and distance are the most significant errors

and given rise to uncertainties of

.

These are the photon noise, the photometric

calibration, the least squares fitting (imperfect model) and the

uncertainties in the age of and distance to Praesepe. The uncertainties

in the age and distance are the most significant errors

and given rise to uncertainties of

![]() and

and

![]() K for a

substellar object,

K for a

substellar object,

![]() and

and

![]() K

for an object at the hydrogen burning limit and

K

for an object at the hydrogen burning limit and

![]() and

and

![]() K for a solar-type

star.

K for a solar-type

star.

3 Candidate selection procedure

The candidate selection procedure for BDs and very low-mass stars is

as follows (and explained in more detail in the remainder of this

section). Candidates were first selected based on colour-magnitude

diagrams (CMDs) and this further refined using colour-colour

diagrams. In the third and final selection, we used the known distance

to Praesepe to reject objects based on a discrepancy between the

observed magnitude in J and the magnitude in this band computed with

the isochrones and our estimation of

![]() .

To be considered

as a cluster member, an object has to satisfy all three of these

criteria. We make two independent selections: one using dust-free and

one using dusty atmospheric models.

.

To be considered

as a cluster member, an object has to satisfy all three of these

criteria. We make two independent selections: one using dust-free and

one using dusty atmospheric models.

3.1 First candidate selection step: colour-magnitude diagrams

Candidates were first selected from our CMDs by retaining only objects

which are no more than 0.14 mag redder or bluer than the isochrone in

all CMDs. This number accommodates errors in the magnitudes,

uncertainties in the model isochrones plus uncertainties in the

cluster age and distance estimates. We additionally include objects

brighter than the isochrones by 0.753 mag in order to include

unresolved binaries. In Figs. 2 and 3

we show two CMDs where candidates were selected based on ![]() vs.

vs. ![]() -J and

-J and ![]() vs.

vs. ![]() -

-![]() .

These figures also show low-mass cluster member candidates from

previous studies which we detected in our survey

(Pinfield et al. 1997; Adams et al. 2002a;

González-García et al. 2006; Kraus & Hillenbrand 2007). In Fig. 3, we can observe three structures in this CMD. The

two structures at

.

These figures also show low-mass cluster member candidates from

previous studies which we detected in our survey

(Pinfield et al. 1997; Adams et al. 2002a;

González-García et al. 2006; Kraus & Hillenbrand 2007). In Fig. 3, we can observe three structures in this CMD. The

two structures at

![]() mag and

mag and

![]() mag are predominantly stars (Galactic

disk turn-off, and disk late-type and giant stars respectively) while

the structure at

mag are predominantly stars (Galactic

disk turn-off, and disk late-type and giant stars respectively) while

the structure at

![]() mag is mostly composed

of galaxies. From a total of 23 891 objects detected above the

5

mag is mostly composed

of galaxies. From a total of 23 891 objects detected above the

5![]() detection limit in all filters, 800 are retained as

candidate cluster members (96.7% are rejected). If we instead use

dusty model isochrones, then out of the 23 891 objects, 357 are

retained (98.5% are rejected) for our dusty model list.

detection limit in all filters, 800 are retained as

candidate cluster members (96.7% are rejected). If we instead use

dusty model isochrones, then out of the 23 891 objects, 357 are

retained (98.5% are rejected) for our dusty model list.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=7.8cm,clip]{13011f02.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/02/aa13011-09/Timg60.png)

|

Figure 2:

Colour-magnitude diagram showing an example of

the first selection step using the |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=7.8cm]{13011f03.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/02/aa13011-09/Timg61.png)

|

Figure 3:

As Fig. 2 but with the |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{13011f04.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/02/aa13011-09/Timg62.png)

|

Figure 4: Colour-colour diagram

used in the second selection step. The solid line is the isochrone

computed from an evolutionary model with a dust-free atmosphere

(NextGen model, the masses in |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{13011f05.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/02/aa13011-09/Timg64.png)

|

Figure 5:

As Fig. 4, but now showing

the theoretical colours of six galaxies as thick dotted lines

and the theoretical colours of red giants as thick solid lines.

The six galaxies are two starbursts, one Sab, one Sbc, and two

ellipticals of 5.5 and 15 Gyr, with redshifts from z = 0 to z = 2 in steps of 0.25 (evolution not considered). We assume that all

red giants have a mass of 5 |

| Open with DEXTER | |

3.2 Second candidate selection step: colour-colour diagram

The second stage of candidate selection involves retaining just those

objects which lie within 0.24 mag of the isochrone in the (single)

colour-colour diagram. This value reflects the photometric errors

plus uncertainty in the age estimation of Praesepe. One such

colour-colour diagram with the selection limits is shown in Fig. 4.

The two main sources of contamination beside field M dwarfs are

background red giants and unresolved galaxies (Praesepe is

at a Galactic latitude of

![]() ). We show in Fig. 5 the theoretical colours for red giants using the

atmosphere models of Hauschildt et al. (1999b) and theoretical colours of

six galaxies from Meisenheimer et al. (in prep.). We see that red giants

could be a source of contamination in the mass range of

0.09-0.2

). We show in Fig. 5 the theoretical colours for red giants using the

atmosphere models of Hauschildt et al. (1999b) and theoretical colours of

six galaxies from Meisenheimer et al. (in prep.). We see that red giants

could be a source of contamination in the mass range of

0.09-0.2 ![]() and at

and at ![]() 0.7

0.7 ![]() ,

while unresolved

galaxies should not be a major source of contamination below

0.6

,

while unresolved

galaxies should not be a major source of contamination below

0.6 ![]() .

In Fig. 5 we see the same three

structures as in Fig. 3: from top to bottom galaxies,

disk late-type and giant stars, and Galactic disk turn-off stars. Of the

800 objects selected in the first step, 291 are kept here (63.6% are

rejected) assuming a dust-free atmosphere, and 110 out of 357 are kept

(69.2% are rejected) when using the model for a dusty atmosphere.

.

In Fig. 5 we see the same three

structures as in Fig. 3: from top to bottom galaxies,

disk late-type and giant stars, and Galactic disk turn-off stars. Of the

800 objects selected in the first step, 291 are kept here (63.6% are

rejected) assuming a dust-free atmosphere, and 110 out of 357 are kept

(69.2% are rejected) when using the model for a dusty atmosphere.

3.3 Third candidate selection step: rejection based on observed magnitude vs. predicted magnitude discrepancy

As indicated in Sect. 2.4, our determination of

![]() is based on the spectral energy distribution of each object and is

independent of the assumed distance. The membership status of an object can therefore

be assessed

by comparing its observed magnitude in a band with its

magnitude predicted from its

is based on the spectral energy distribution of each object and is

independent of the assumed distance. The membership status of an object can therefore

be assessed

by comparing its observed magnitude in a band with its

magnitude predicted from its

![]() and Praesepe's isochrone (which assumes a distance).

The premise is that the predicted magnitude of a background

contaminant would be lower (brighter) than its observed magnitude and

higher (fainter) for a foreground contaminant. In order to avoid

removing unresolved binaries that are real members of the cluster, we

keep all objects with a computed magnitude of up to 0.753 mag

brighter than the observed magnitude. We also take into account

photometric errors and uncertainties in the age and distance of

Praesepe. This selection procedure is illustrated in Fig. 6. From 291 objects selected through CMDs and

colour-colour diagrams in the first two steps, 144 are kept (50.5% are rejected) when using

the dust-free atmospheres/models, and 35 out of 110 are kept (68.2%

are rejected) when using the dusty atmosphere/models.

and Praesepe's isochrone (which assumes a distance).

The premise is that the predicted magnitude of a background

contaminant would be lower (brighter) than its observed magnitude and

higher (fainter) for a foreground contaminant. In order to avoid

removing unresolved binaries that are real members of the cluster, we

keep all objects with a computed magnitude of up to 0.753 mag

brighter than the observed magnitude. We also take into account

photometric errors and uncertainties in the age and distance of

Praesepe. This selection procedure is illustrated in Fig. 6. From 291 objects selected through CMDs and

colour-colour diagrams in the first two steps, 144 are kept (50.5% are rejected) when using

the dust-free atmospheres/models, and 35 out of 110 are kept (68.2%

are rejected) when using the dusty atmosphere/models.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{13011f06.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/02/aa13011-09/Timg66.png)

|

Figure 6:

Difference between the observed J magnitude and the model J magnitude computed from the derived

mass and

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

After this step, we perform a visual inspection directly on the images to reject resolved galaxies and spurious detections. This inspection removes 21 and 8 objects from the dust-free and dusty selection respectively.

4 Results of the survey

We now present the selected candidates, discuss contamination by cluster non-members and derive the magnitude and mass functions for Praesepe.

4.1 Selected photometric candidates

The final selection reveals 123 photometric candidates using an

isochrone based on dust-free atmospheres, and 27 objects using an

isochrone assuming dusty atmospheres![]() . This corresponds to

. This corresponds to ![]() 40 and

40 and ![]() 9 objects per deg2respectively. All our photometric candidates are presented in Table 3. Objects are given the notation

PRAESEPE-YYY where YYY is a serial identification number (ID).

Numbers above 900 indicate candidate members assuming a dusty

atmosphere. Only the first 10 rows of the tables are shown, all other

data are available online. We also note in Table 4 which objects are candidate cluster members

also identified as such by Kraus & Hillenbrand (2007), Adams et al. (2002a) or

Pinfield et al. (1997).

9 objects per deg2respectively. All our photometric candidates are presented in Table 3. Objects are given the notation

PRAESEPE-YYY where YYY is a serial identification number (ID).

Numbers above 900 indicate candidate members assuming a dusty

atmosphere. Only the first 10 rows of the tables are shown, all other

data are available online. We also note in Table 4 which objects are candidate cluster members

also identified as such by Kraus & Hillenbrand (2007), Adams et al. (2002a) or

Pinfield et al. (1997).

Table 3: All photometric cluster member candidates of our survey. Table 3 is published in its entirety in the electronic edition of Astronomy & Astrophysics. A fraction is shown here for guidance regarding its form and content.

Some Praesepe members from previous studies are not detected in our

work. This is the case for the objects from Pace et al. (2008) and

Fossati et al. (2008), for example. Since those studies focused on bright

objects, these stars saturate in our science images.

(Pace et al. 2008; Fossati et al. 2008, were concerned with chemical

abundances of A-type and solar-type stars, respectively, while our

saturation occurs at ![]() 0.7

0.7 ![]() ).

).

Not all objects identified by other surveys as brown dwarfs or very

low mass stellar member candidates - and detected in our survey -

are members based on our criteria. The two objects from the work of

González-García et al. (2006), who also used photometry in order to

select candidate members, we detect above our 5![]() limit

(Prae J084039.3+192840 and Prae J084130.4+190449). Yet both objects are

non-members based on our selection criteria, because they have

limit

(Prae J084039.3+192840 and Prae J084130.4+190449). Yet both objects are

non-members based on our selection criteria, because they have

![]() colours bluer than our selection band.

(Prae J084130.4+190449

is also too blue in

colours bluer than our selection band.

(Prae J084130.4+190449

is also too blue in

![]() for our selection band at

for our selection band at

![]() mag, whereas Prae J084039.3+192840 at

mag, whereas Prae J084039.3+192840 at

![]() mag lies within it).

González-García et al. (2006) did not report any NIR photometry for

these two objects. Although the non-membership of

Prae J084039.3+192840 can be debated (high membership probability

based on González-García et al. 2006), Prae J084130.4+190449 is most

likely an unresolved galaxy (low membership probability;

González-García et al. 2006).

mag lies within it).

González-García et al. (2006) did not report any NIR photometry for

these two objects. Although the non-membership of

Prae J084039.3+192840 can be debated (high membership probability

based on González-García et al. 2006), Prae J084130.4+190449 is most

likely an unresolved galaxy (low membership probability;

González-García et al. 2006).

Table 4: Photometric candidates in our survey that are also photometric candidates in previous surveys.

Of the candidates from the photometric survey of Pinfield et al. (1997), seven fall within our survey and are detected, of which six are identified as candidates by our selection criteria. The non-selected object is RIZpr6 in Hodgkin et al. (1999). It is bluer than the isochrones in both CMDs in Figs. 2 and 3. From its positions in the CMDs and in the colour-colour diagram in Fig. 4, we suspect that this object is an unresolved galaxy.

11 of the the 14 objects from a survey based on proper motion and

photometry by Adams et al. (2002a) are identified by our selection. The

objects not recovered fail the observed magnitude vs. predicted

magnitude test. On the other hand, 27 cluster candidates of

Kraus & Hillenbrand (2007) out of 37 detected in our survey are selected. The

10 non-selected objects have membership probabilities from

Kraus & Hillenbrand (2007) based on proper motion greater than 95%, and are

brighter than the 10![]() detection limit of the publicly available

surveys used in their work. However, these objects failed our observed

magnitude vs. predicted magnitude test and some are bluer than our

isochrone of Praesepe in

detection limit of the publicly available

surveys used in their work. However, these objects failed our observed

magnitude vs. predicted magnitude test and some are bluer than our

isochrone of Praesepe in

![]() .

With

.

With

![]() colour of

colour of ![]() 2 mag, we suggest that these objects are more likely to be disk late-type stars or giant stars.

2 mag, we suggest that these objects are more likely to be disk late-type stars or giant stars.

The 5![]() detection limits of our survey are

detection limits of our survey are

![]() mag, J = 20.0 mag and

mag, J = 20.0 mag and

![]() mag (which

correspond to

mag (which

correspond to ![]() 0.05

0.05 ![]() using the dust-free

isochrone). However, we cannot expect to detect all objects

down to these magnitudes.

We estimate the survey completeness

by taking the ratio of the number of objects

detected to the predicted number of detections, the latter made by assuming a uniform

distribution of stars along the line of sight in our survey fields.

(This comparison distribution is somewhat crude, but it gives

an approximate value without making too many assumptions). The

predicted number of detections is obtained from the histogram of the

number of detections as a function of magnitude (Fig. 7)

and by observing where the distribution drops off compared to a

straight line extrapolation. Based on this, the completeness of the

survey down to the

5

using the dust-free

isochrone). However, we cannot expect to detect all objects

down to these magnitudes.

We estimate the survey completeness

by taking the ratio of the number of objects

detected to the predicted number of detections, the latter made by assuming a uniform

distribution of stars along the line of sight in our survey fields.

(This comparison distribution is somewhat crude, but it gives

an approximate value without making too many assumptions). The

predicted number of detections is obtained from the histogram of the

number of detections as a function of magnitude (Fig. 7)

and by observing where the distribution drops off compared to a

straight line extrapolation. Based on this, the completeness of the

survey down to the

5![]() detection limit is 90% in

detection limit is 90% in ![]() ,

88% in J and 87%

in

,

88% in J and 87%

in ![]() .

The overall detection completeness of our

survey, from saturation to 5

.

The overall detection completeness of our

survey, from saturation to 5![]() detection corresponding to

0.05

detection corresponding to

0.05 ![]() ,

is therefore

,

is therefore ![]() 87%. In J band, we reach a completeness of 95% at J = 19.7 mag, which corresponds to

87%. In J band, we reach a completeness of 95% at J = 19.7 mag, which corresponds to ![]() 0.055

0.055 ![]() .

.

4.2 Substellar candidates in Praesepe

Six objects in our survey are cluster candidates with theoretical

masses equal to or below the stellar/substellar boundary at

0.072 ![]() .

We present the finding charts of the six objects in

Fig. 8. In Table 5, we

present their coordinates and physical parameters. These BD candidates

have predicted masses between 0.064 and 0.072

.

We present the finding charts of the six objects in

Fig. 8. In Table 5, we

present their coordinates and physical parameters. These BD candidates

have predicted masses between 0.064 and 0.072 ![]() .

A

spectroscopic follow up (on a 8 m class telescope or larger) will be

needed in order to confirm or refute their membership and their

substellar status.

.

A

spectroscopic follow up (on a 8 m class telescope or larger) will be

needed in order to confirm or refute their membership and their

substellar status.

4.3 Contamination by non-members

As mentioned in Sect. 3.2, the two main sources of

contamination are the background red giants, which are the dominant

source at masses of 0.09-0.2 ![]() and

and ![]() 0.7

0.7 ![]() ,

and unresolved galaxies, mostly affecting masses above

0.6

,

and unresolved galaxies, mostly affecting masses above

0.6 ![]() .

Other possible contaminants are field M dwarfs and high redshift quasars (for instance at

.

Other possible contaminants are field M dwarfs and high redshift quasars (for instance at ![]() ;

Caballero et al. 2008). However, as such quasars have spectral

energy distributions similar to mid-T dwarfs whereas our faintest

candidates are early L dwarfs, and given that they are rare (3.3 quasars at

5.5 < z < 6.5 in a 8 deg2 survey,

Stern et al. 2007), the MF should not be affected by quasar

contamination.

;

Caballero et al. 2008). However, as such quasars have spectral

energy distributions similar to mid-T dwarfs whereas our faintest

candidates are early L dwarfs, and given that they are rare (3.3 quasars at

5.5 < z < 6.5 in a 8 deg2 survey,

Stern et al. 2007), the MF should not be affected by quasar

contamination.

Let us estimate the contamination by M dwarfs,

First, we consider that close to the open cluster Praesepe, the space

density of M dwarfs is uniform. We assume that their

density (![]() )

drops exponentially with vertical distance

from the galactic disk (h) such that

)

drops exponentially with vertical distance

from the galactic disk (h) such that

|

(4) |

assuming a scale height of h0 = 500 pc. We use the local space density (

4.4 Luminosity function and mass function

We present in Fig. 9 the luminosity function of Praesepe using the J-band magnitude of the cluster candidates. No correction is made for binaries, so this is the system rather than single-star luminosity function.

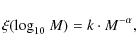

The mass function (MF),

![]() ), is generally defined as

the number of stars per cubic parsec in the logarithmic mass interval

), is generally defined as

the number of stars per cubic parsec in the logarithmic mass interval

![]() to

to

![]() .

Here, we do not compute

the volume of Praesepe so instead we define the MF as the total

number of objects in each

.

Here, we do not compute

the volume of Praesepe so instead we define the MF as the total

number of objects in each

![]() bin per square degree.

Since we do not make any corrections for

binaries we compute here a system MF. Our inferred MF is

shown in Fig. 10. The log-normal form for a MF is

bin per square degree.

Since we do not make any corrections for

binaries we compute here a system MF. Our inferred MF is

shown in Fig. 10. The log-normal form for a MF is

![\begin{displaymath}\xi({\log}_{10}~ {M})=k\cdot {\exp}{\biggl[-\frac{({\log}_{10}~ {M}- {\log}_{10}~ {M}_0)^2}{2\sigma^2}\biggr]},

\end{displaymath}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/02/aa13011-09/img98.png)

|

(5) |

where k = 0.086,

from the highest mass bin to the turn over at 0.1

5 Analysis and discussion of the stellar and substellar mass function of Praesepe

Our MF of Praesepe (Fig. 10) shows a rise in the

number of objects from 0.6 ![]() down to 0.1

down to 0.1 ![]() ,

and then

a turn-over at

,

and then

a turn-over at ![]() 0.1

0.1 ![]() .

This turn-over is not due to

incompleteness since it occurs well above the 5

.

This turn-over is not due to

incompleteness since it occurs well above the 5![]() detection

limit corresponding to 0.05

detection

limit corresponding to 0.05 ![]() .

This behaviour is confirmed

by the luminosity function in Fig. 9 which shows a

rise from J = 13 to 16 mag (with candidates obtained using a dust-free

atmosphere) and a drop at J = 17 mag (seen with both types of candidates).

To help the analysis of these features in the mass function, we compare in

Fig. 11 the mass functions of Praesepe obtained from several studies plus the MF for the old open cluster Hyades (age of 625 Myr).

.

This behaviour is confirmed

by the luminosity function in Fig. 9 which shows a

rise from J = 13 to 16 mag (with candidates obtained using a dust-free

atmosphere) and a drop at J = 17 mag (seen with both types of candidates).

To help the analysis of these features in the mass function, we compare in

Fig. 11 the mass functions of Praesepe obtained from several studies plus the MF for the old open cluster Hyades (age of 625 Myr).

The rise in our MF of Praesepe is also present in the MFs obtained in the

three previous studies of Baker & Jameson (2009), Kraus & Hillenbrand (2007) and

Hambly et al. (1995). On the other hand, we do not see this rise in the

MF of Adams et al. (2002a). However, their MF is based on objects with a

membership probability higher than only 1% and within a radius of

3.8 deg. Due to use of such a low probability threshold for

selection, we expect that most of the objects used in the MF

determination are simply field stars (which is their own conclusion in

Sect. 5.4; Adams et al. 2002a), so further comparison is not

warranted. As for the MFs of González-García et al. (2006) and Pinfield et al. (1997), since the highest mass bins are ![]() 0.11 and

0.11 and ![]() 0.15

0.15 ![]() (respectively), the rise observed from 0.6

(respectively), the rise observed from 0.6 ![]() to

0.1

to

0.1 ![]() cannot be discussed.

cannot be discussed.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{13011f07.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/02/aa13011-09/Timg108.png)

|

Figure 7:

Estimation of the completeness

limit for our survey using the J band. The solid line is the

best linear fit before the turn off, the vertical dashed line is

the 5 |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{13011f08.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/02/aa13011-09/Timg109.png)

|

Figure 8:

Finding charts of the six new BD

candidates of Praesepe (J-band). We observed objects very close

to PRAESEPE-099 and -909, although they do not influence the

photometry. The panels are

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

Table 5: Same as Table 3, but only the BD candidates are given and we include the spectral type expected.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{13011f09.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/02/aa13011-09/Timg110.png)

|

Figure 9:

J band luminosity function. The

solid line histogram represents the luminosity function based on a

selection using a dust-free atmosphere (NextGen model); the

thick dotted histogram uses a dusty atmosphere (AMES-Dusty

model). The stellar/substellar limit is at

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{13011f10.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/02/aa13011-09/Timg113.png)

|

Figure 10:

Mass function based on our survey photometry. Points with error bars represent the MF based on a selection and

mass calibration assuming a dust-free atmosphere, whereas the open

circles with error bars are the MF based on the dusty atmosphere

model. We also overplot the log-normal and the power law MF fitted

to our data (both solid line). Error bars are Poissonian arising

from the number of objects observed in each bin. The vertical thin

dotted lines are the mass limits at which detector saturation occurs

in the |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Only four MFs, in addition to our work, reach masses below

0.1 ![]() :

Baker & Jameson (2009), González-García et al. (2006),

Pinfield et al. (1997) and Hambly et al. (1995). While the MFs of

Baker & Jameson (2009) and Hambly et al. (1995) show a turn-over at

0.1

:

Baker & Jameson (2009), González-García et al. (2006),

Pinfield et al. (1997) and Hambly et al. (1995). While the MFs of

Baker & Jameson (2009) and Hambly et al. (1995) show a turn-over at

0.1 ![]() ,

the one obtained by Pinfield et al. (1997) does not.

On the contrary, it presents a sudden rise at the

stellar/substellar limit (with a ratio of

,

the one obtained by Pinfield et al. (1997) does not.

On the contrary, it presents a sudden rise at the

stellar/substellar limit (with a ratio of ![]() 5 in the number of

objects at the mass bin at 0.07 to the number in the bin at

0.11

5 in the number of

objects at the mass bin at 0.07 to the number in the bin at

0.11 ![]() ). They used RIZ photometry for their survey, but not all

objects were observed in all bands, resulting in just

one colour available for membership determination in some cases

(Pinfield et al. 1997). From an analysis of MFs of other clusters and

using a multi-band photometric survey, Boudreault & Bailer-Jones (2009) have

shown that use of a narrow spectral coverage with few filters can lead

to high contamination by field M dwarfs, and thus an apparent rise in

the MF in the low mass regime. We suggest that this is the reason for

the apparent rise at the low-mass end of the MF in Pinfield et al. (1997)

(who also noted that only one colour is available for many objects in

their two lowest bins). As for the MF of González-García et al. (2006),

as they only have three points we cannot comment on any possible

trend.

). They used RIZ photometry for their survey, but not all

objects were observed in all bands, resulting in just

one colour available for membership determination in some cases

(Pinfield et al. 1997). From an analysis of MFs of other clusters and

using a multi-band photometric survey, Boudreault & Bailer-Jones (2009) have

shown that use of a narrow spectral coverage with few filters can lead

to high contamination by field M dwarfs, and thus an apparent rise in

the MF in the low mass regime. We suggest that this is the reason for

the apparent rise at the low-mass end of the MF in Pinfield et al. (1997)

(who also noted that only one colour is available for many objects in

their two lowest bins). As for the MF of González-García et al. (2006),

as they only have three points we cannot comment on any possible

trend.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=14cm,clip]{13011f11.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/02/aa13011-09/Timg115.png)

|

Figure 11:

MF of Praesepe from our present

work (open dots assuming a dusty atmosphere and

filled dots assuming a dust-free atmosphere), from

previous work (open triangles for survey using proper

motion and filled triangles for survey using photometry

only), as well as the MF from the Hyades from Bouvier et al. (2008)

(open squares). We also show the galactic field star MF

from Chabrier (2003) as a thin dashed line and the substellar

limit as a thick dashed line. We have normalized all the MFs to

the log-normal fit of Chabrier et al. (2005) at |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Although there are some discrepancies between the different MFs of

Praesepe from previous works and our MF, none agrees with the MF of

the Hyades (![]() 625 Myr) obtained by

Bouvier et al. (2008)

625 Myr) obtained by

Bouvier et al. (2008)![]() , in which the MF is observed to turn-over

and decrease already at 0.35

, in which the MF is observed to turn-over

and decrease already at 0.35 ![]() .

This is surprising, since

Praesepe and the Hyades share a comparable age, size and mass: they

have ages of 590

+150-120 Myr (Fossati et al. 2008) and

.

This is surprising, since

Praesepe and the Hyades share a comparable age, size and mass: they

have ages of 590

+150-120 Myr (Fossati et al. 2008) and

![]() Myr (Bouvier et al. 2008), tidal radii of

Myr (Bouvier et al. 2008), tidal radii of

![]() pc (

pc (

![]() deg, Kraus & Hillenbrand 2007) and 10.3 pc

(12.5 deg, Bouvier et al. 2008), and masses of

deg, Kraus & Hillenbrand 2007) and 10.3 pc

(12.5 deg, Bouvier et al. 2008), and masses of

![]() (Kraus & Hillenbrand 2007) and about 400

(Kraus & Hillenbrand 2007) and about 400 ![]() (Bouvier et al. 2008), respectively. Therefore, we can expect that

the potential well is the same (at least today). Only the metallicity

may be slightly different, assuming the most recent measurement for

Praesepe: [Fe/H] = +

(Bouvier et al. 2008), respectively. Therefore, we can expect that

the potential well is the same (at least today). Only the metallicity

may be slightly different, assuming the most recent measurement for

Praesepe: [Fe/H] = +

![]() for the latest metallicity

measurement of Praesepe (Pace et al. 2008) and

[Fe/H] = +

for the latest metallicity

measurement of Praesepe (Pace et al. 2008) and

[Fe/H] = +

![]() for the Hyades (Bouvier et al. 2008),

although a metallicity as low as +

for the Hyades (Bouvier et al. 2008),

although a metallicity as low as +

![]() (Friel & Boesgaard 1992) has been reported for Praesepe. It is unclear

how this metallicity difference could explain the significantly

different mass functions.

(Friel & Boesgaard 1992) has been reported for Praesepe. It is unclear

how this metallicity difference could explain the significantly

different mass functions.

It is a priori possible that different binary mass fractions in

Praesepe and the Hyades could account for the difference in their

observed (i.e. system, rather than star) mass functions. The binary

fraction in Praesepe for different mass intervals was obtained by

Pinfield et al. (2003): 17

+6-4% for 1.0-0.6 ![]() ,

31

+7-6% for 0.6-0.35

,

31

+7-6% for 0.6-0.35 ![]() ,

,

![]() % for

0.35-0.2

% for

0.35-0.2 ![]() and 47

+13-11% for 0.11-0.09

and 47

+13-11% for 0.11-0.09 ![]() .

As for the Hyades, Gizis & Reid (1995) observed a binary fraction of

.

As for the Hyades, Gizis & Reid (1995) observed a binary fraction of

![]() % for their sample of stars (

% for their sample of stars (![]() 0.4

0.4 ![]() ), which

is consistent with another determination of the Hyades binary fraction

of

), which

is consistent with another determination of the Hyades binary fraction

of ![]() % from Patience et al. (1998) (for a primary mass of

% from Patience et al. (1998) (for a primary mass of

![]() 0.6-2.8

0.6-2.8 ![]() ).

From these figures we see no significant difference in the binary

fractions of the two clusters (even if primarily

because the uncertainties are quite large), so this cannot be used

to explain the difference between in their mass functions. Of course,

if the typical mass ratio in a binary system is different in the two

clusters then this may be able

to account for some difference in the mass functions, but their

is also no evidence to support (or refute) this.

).

From these figures we see no significant difference in the binary

fractions of the two clusters (even if primarily

because the uncertainties are quite large), so this cannot be used

to explain the difference between in their mass functions. Of course,

if the typical mass ratio in a binary system is different in the two

clusters then this may be able

to account for some difference in the mass functions, but their

is also no evidence to support (or refute) this.

A distinction between the two clusters could be the spatial

distribution of the members. Indeed, Holland et al. (2000) observed that

the Praesepe cluster might be composed of two merged clusters with

different ages, one main cluster of 630 ![]() and a second

subcluster of 30

and a second

subcluster of 30 ![]() .

It was even proposed that faint low-mass

members of the subcluster could appear as Praesepe brown dwarf candidates

(Chappelle et al. 2005). However, Adams et al. (2002a) did not find

evidence of a subcluster in Praesepe. Based on the spatial

distribution of the main cluster and subcluster from

Holland et al. (2000), our survey only overlaps the main cluster. In

addition, a collision between two clusters could not explain alone an

increase of the MF down to 0.1

.

It was even proposed that faint low-mass

members of the subcluster could appear as Praesepe brown dwarf candidates

(Chappelle et al. 2005). However, Adams et al. (2002a) did not find

evidence of a subcluster in Praesepe. Based on the spatial

distribution of the main cluster and subcluster from

Holland et al. (2000), our survey only overlaps the main cluster. In

addition, a collision between two clusters could not explain alone an

increase of the MF down to 0.1 ![]() ,

as such a collision would

rather remove low-mass member of the clusters.

,

as such a collision would

rather remove low-mass member of the clusters.

By comparing the MF of the Hyades with the one of the Pleiades

(![]() 120 Myr), Bouvier et al. (2008) concluded that dynamical

evolution was responsible for the deficiency observed in the very-low

mass star and BD regime in the Hyades. However, this deficiency is not

seen in Praesepe. One possible implication is that Praesepe has been

less affected by dynamical evolution, i.e. evaporation of low mass

members which are expected to have higher speeds based on

equipartition of energy. On the other hand, if dynamical evolution

has affected Praesepe in the same way, then it cannot have had

the same initial mass function and/or initial conditions as the

Hyades. Dynamical interaction between one of these clusters and

another object (such as another open cluster in the past) could

explain the discrepancies between the two MFs.

120 Myr), Bouvier et al. (2008) concluded that dynamical

evolution was responsible for the deficiency observed in the very-low

mass star and BD regime in the Hyades. However, this deficiency is not

seen in Praesepe. One possible implication is that Praesepe has been

less affected by dynamical evolution, i.e. evaporation of low mass

members which are expected to have higher speeds based on

equipartition of energy. On the other hand, if dynamical evolution

has affected Praesepe in the same way, then it cannot have had

the same initial mass function and/or initial conditions as the

Hyades. Dynamical interaction between one of these clusters and

another object (such as another open cluster in the past) could

explain the discrepancies between the two MFs.

6 Conclusions

We have presented the results of a survey to study the mass function

of the old open cluster Praesepe. The survey consisted of optical

![]() -band photometry and NIR J and

-band photometry and NIR J and ![]() -band

photometry with a total coverage of 3.1 deg2, down to the

substellar regime, with a 5

-band

photometry with a total coverage of 3.1 deg2, down to the

substellar regime, with a 5![]() detection limit corresponding to

0.05

detection limit corresponding to

0.05 ![]() (the detection completeness to this level is

(the detection completeness to this level is

![]() 87%).

87%).

Our final sample yields 123 photometric cluster member

candidates based on a selection assuming a dust-free atmosphere and 27

photometric cluster candidates based on a selection assuming a dusty

atmosphere. We estimate the contamination by field M-dwarfs to be

13% or less. Among our cluster candidates, six objects have theoretical

masses equal to or less than the stellar/substellar boundary at

0.072 ![]() .

.

We observed that the MF of Praesepe is characterized by a rise in the

number of objects from 0.6 ![]() down to 0.1

down to 0.1 ![]() ,

followed by

a turn-over in the MF at

,

followed by

a turn-over in the MF at ![]() 0.1

0.1 ![]() .

The rise is in agreement with the Praesepe MFs derived in several previous studies (Hambly et al. 1995;

Kraus & Hillenbrand 2007; Baker & Jameson 2009) but disagrees with

Adams et al. (2002a).

.

The rise is in agreement with the Praesepe MFs derived in several previous studies (Hambly et al. 1995;

Kraus & Hillenbrand 2007; Baker & Jameson 2009) but disagrees with

Adams et al. (2002a).

We have compared the mass function of Praesepe with one derived for

the Hyades and have observed a significant difference: while the Hyades has

a maximum at 0.35 ![]() ,

Praesepe has a maximum at a

much lower mass, 0.1

,

Praesepe has a maximum at a

much lower mass, 0.1 ![]() .

Assuming that they have similar ages

(as main sequence fitting suggests), we conclude that the clusters

either had different initial mass functions or that dynamical

interaction has modified the evolution of one or both. More

specifically, in the latter case, dynamical evaporation does not seem

to have influenced the Hyades and Praesepe in the same way. A

difference in the binary fraction or mass ratios could also cause a

difference in the mass functions, but determinations of these are not

yet precise enough to suggest any difference.

.

Assuming that they have similar ages

(as main sequence fitting suggests), we conclude that the clusters

either had different initial mass functions or that dynamical

interaction has modified the evolution of one or both. More

specifically, in the latter case, dynamical evaporation does not seem

to have influenced the Hyades and Praesepe in the same way. A

difference in the binary fraction or mass ratios could also cause a

difference in the mass functions, but determinations of these are not

yet precise enough to suggest any difference.

S.B. and C.B.J. acknowledge support from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) grant BA2163 (Emmy-Noether Programme) to CBJ. S.B. thanks the Calar Alto observatory staff for support and Kester Smith for observations performed in January 2007. We are grateful to the referee, Nigel Hambly, for his constructive comments and suggestions. We acknowledge Klaus Meisenheimer and Marie-Hélène Nicol for useful discussions about galaxy contamination. IRAF is distributed by the National Optical Astronomy Observatories, which are operated by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy, Inc., under cooperative agreement with the National Science Foundation. Some data analysis in this article has made use of the freely available R statistical package, http://www.r-project.org. This research has made use of the SIMBAD database, operated at CDS, Strasbourg, France. This publication makes use of data products from the Two Micron All Sky Survey, which is a joint project of the University of Massachusetts and the Infrared Processing and Analysis Center/California Institute of Technology, funded by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration and the National Science Foundation.

References

- Adams, J. D., Stauffer, J. R., Skrutskie, M. F., et al. 2002a, AJ, 124, 1570 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Adams, T., Davies, M. B., Jameson, R. F., et al. 2002b, MNRAS, 333, 547 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [MathSciNet] [Google Scholar]

- Allard, F., Hauschildt, P. H., Alexander, D. R., et al. 2001, ApJ, 556, 357 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- An, D., Terndrup, D. M., Pinsonneault, M. H., et al., 2007, ApJ, 655, 233 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Baade, D., Meisenheimer, K., Iwert, O., et al. 1999, The Messenger, 95, 15 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Bailer-Jones, C. A. L., & Mundt, R. 2001, A&A, 367, 218 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Bailer-Jones, C. A., Bizenberger, P., & Storz, C., 2000, SPIE Conf. Ser., 4008, 1305 [Google Scholar]

- Baker, D. E. A., & Jameson, R. F. 2009, Brown Dwarfs in Praesepe: A search for low mass members using UKIDSS, JENAM2009 meeting, poster No. 3-P03 [Google Scholar]

- Barrado y Navascués, D., Stauffer, J. R., & Jayawardhana, R. 2004, ApJ, 614, 386 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Baraffe, I., Chabrier, G., Allard, F., et al. 1998, A&A, 337, 403 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Baraffe, I., Chabrier, G., Allard, F., et al. 2002, A&A, 382, 563 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister, H., Bizenberger, P., Bailer-Jones, C. A. L., et al. 2003, SPIE Conf. Ser., 4841, 343 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Béjar, V. J. S., Martín, E. L., Zapatero Osorio, M. R., et al. 2001, ApJ, 556, 830 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Boesgaard, A. M., & Budge, K. G. 1988, ApJ, 332, 410 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Boudreault, S., & Bailer-Jones, C. A. L. 2009, ApJ, 706, 1484 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bouvier, J., Kendall, T. T., Meeus, G., et al. 2008, A&A, 481, 661 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Briceño, C., Luhman, K. L., Hartmann, L., Stauffer, J. R., & Kirkpatrick, J. D. 2002, ApJ, 580, 317 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Caballero, J. A., Béjar, V. J. S., Rebolo, R., et al. 2007, A&A, 470, 903 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Caballero, J. A., Burgasser, A. J., & Klement, R. 2008, A&A, 488, 181 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Chabrier, G., Baraffe, I., Allard, F., et al. 2000, ApJ, 542, 464 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chabrier, G. 2003, PASP, 115, 763 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chabrier, G., Baraffe, I., Allard, F., et al. 2005, Invited review Cancun [astro-ph/0509798] [Google Scholar]

- Chappelle, R. J., Pinfield, D. J., Steele, I. A., et al. 2005, MNRAS, 361, 1323 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Close, L. M., Lenzen, R., Guirado, J. C., et al. 2005, Nature, 433, 286 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colina, L., Bohlin, R., & Castelli, F. 1996, Instrument Science Report CAL/SCS, 8, 1 [Google Scholar]

- D'Antona, F., & Mazzitelli, I. 1985, ApJ, 296, 502 [Google Scholar]

- de la Fuente Marcos, R., & de la Fuente Marcos, C. 2000, Ap&SS, 271, 127 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Fossati, L., Bagnulo, S., Landstreet, J., et al. 2008, A&A, 483, 891 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Friel, E. D., & Boesgaard, A. M. 1992, ApJ, 387, 170 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Gizis, J., & Reid, I. N. 1995, AJ, 110, 1248 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- González-García, B. M., Zapatero Osorio, M. R., Béjar, V. J. S., et al. 2006, A&A, 460, 799 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Hambly, N. C., Steele, I. A., Hawkins, M. R. S., et al. 1995, MNRAS, 273, 505 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hambly, N. C., Hodgkin, S. T., Cossburn, M. R., et al. 1999, MNRAS, 303, 835 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Harris, H. C., Vrba, F. J., Dahn, C. C., et al. 1999, AJ117, 339 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hauschildt, P. H., Allard, F., & Baron, E. 1999a, ApJ, 512, 377 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hauschildt, P. H., Allard, F., Ferguson, J., Baron, E., & Alexander, D. R., 1999b, ApJ, 525, 871 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Henry, T. J., Jao, W.-C., Subasavage, J. P., et al. 2006, AJ, 132, 2360 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hester, J. J., Scowen, P. A., Sankrit, R., et al. 1996, AJ, 111, 2349 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hillenbrand, L. A., & Carpenter, J. M. 2000, ApJ, 540, 236 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]