| Issue |

A&A

Volume 509, January 2010

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A32 | |

| Number of page(s) | 11 | |

| Section | Stellar structure and evolution | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/200913103 | |

| Published online | 14 January 2010 | |

Exploring the P vs. P

vs. P relation with flux transport dynamo models of solar-like stars

relation with flux transport dynamo models of solar-like stars

L. Jouve1,2 - B. P. Brown3 - A. S. Brun1,3

1 - Laboratoire AIM, CEA/DSM-CNRS-Université Paris Diderot,

IRFU/SAp, 91191 Gif-sur-Yvette, France

2 -

D.A.M.T.P., Centre for Mathematical Sciences, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB03 0WA, UK

3 -

JILA and Department of Astrophysical and Planetary Sciences, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO 80309-0440, USA

Received 11 August 2009 / Accepted 5 November 2009

Abstract

Aims. Understand stellar magnetism and test the validity of

the Babcock-Leighton flux transport mean field dynamo models with

stellar activity observations

Methods. 2-D mean field dynamo models at various rotation rates

are computed with the STELEM code to study the sensitivity of the

activity cycle period and butterfly diagram to parameter changes and

are compared to observational data. The novelty is that these 2-D mean

field dynamo models incorporate scaling laws deduced from 3-D

hydrodynamical simulations for the influence of rotation rate on the

amplitude and profile of the meridional circulation. These models make

also use of observational scaling laws for the variation of

differential rotation with rotation rate.

Results. We find that Babcock-Leighton flux transport dynamo

models are able to reproduce the change in topology of the magnetic

field (i.e. toward being more toroidal with increasing rotation rate)

but seem to have difficulty reproducing the cycle period vs activity

period correlation observed in solar-like stars if a monolithic single

cell meridional flow is assumed. It may however be possible to recover

the

![]() vs.

vs.

![]() relation with more complex meridional flows, if the profile changes in a particular assumed manner with rotation rate.

relation with more complex meridional flows, if the profile changes in a particular assumed manner with rotation rate.

Conclusions. The Babcock-Leighton flux transport dynamo model based on single cell meridional circulation does not reproduce the

![]() vs.

vs.

![]() relation unless the amplitude of the meridional circulation is assumed

to increase with rotation rate which seems to be in contradiction with

recent results obtained with 3-D global simulations.

relation unless the amplitude of the meridional circulation is assumed

to increase with rotation rate which seems to be in contradiction with

recent results obtained with 3-D global simulations.

Key words: magnetohydrodynamics - stars: activity - stars: magnetic fields - Sun: activity - methods: numerical

1 Introduction

The Sun is a magnetic star that possesses a well defined cyclic activity period of 22 years. It is believed that the origin of this magnetism and regular activity is linked to a global scale dynamo operating in and at the base of the solar convection zone (Parker 1993). In order to model and understand this global scale dynamo, a useful approach has been to make use of the mean field dynamo theory (Moffatt 1978; Krause & Raedler 1980). This method has the advantage that it only deals with the large scale magnetic field, assuming some parameterization of the underlying small scale turbulence and magnetism. Computing those physical processes self-consistently would otherwise require costly full 3-D magnetohydrodynamical (MHD) simulations (Cattaneo 1999; Brun et al. 2004). Among the various mean field dynamo models, the Babcock-Leighton flux transport dynamo models have recently been the favored ones and have demonstrated some success at reproducing solar observations assuming either an advection or a diffusion dominated regime for the transport of field from the surface down to the tachocline (Dikpati & Charbonneau 1999; Nandy & Choudhuri 2002; Dikpati et al. 2004; Chatterjee et al. 2004; Charbonneau 2005; Bonanno et al. 2005; Jouve & Brun 2007a; Yeates et al. 2008).It is legitimate to ask if such models can be applied to other stars and lead to the same agreement with the observations of for instance solar type stars that may possess different rotation rates and activity levels.

1.1 Observational constraints

Observations of the magnetism of ``solar type'' stars, i.e. stars possessing a deep convective envelope and a radiative interior (late F, G, K and early M spectral type) are becoming more and more available (Giampapa 2004) and may provide additional constraints on our understanding of global scale stellar dynamos. One difficulty of such observational programs is that they require long term observations since stellar cycle periods are likely to be commensurate to the solar 11-yr sunspots cycle period (or 22-yr for a full cycle including two polarity reversals of the global poloidal field). Thanks to the data collected at Mount Wilson Observatory since the late 60's, such data is available (Wilson 1978; Baliunas et al. 1995). Among the sample of 111 stars (including the Sun as a star) originally observed between the F2 to M2 spectral type, it is found that about 50% of the stars possess a cyclic activity, with cycle (starspot) periods varying roughly between 5 to 25 yrs, i.e. between half to twice the sunspot cycle period. They further indicate that among the inactive stars of the sample some are likely to be in a quiet phase (as was the Sun during the Maunder minimum). Overall activity cycles seems to be more frequent for less massive stars K than for F stars. More recent observational programs have been pursued that now even provide information on the field topology as a function of the rotation rate, such as the one using the Espadons and Narval instruments and the Zeeman Doppler Imaging technique (Donati et al. 2006). Applying this observational technique over a sample of four solar analogues with rotation rate varying from one to three times solar, Petit et al. (2008) have shown that the field amplitude increases as a function of the star's rotation rate and, more importantly, becomes more and more dominated by its toroidal component (modulo possible bias in the observational technique used). If such a trend is confirmed, i.e. that the field topology is becoming more toroidal with increasing rotation rate, it is a very important and instructive result and puts strong constraints on the dynamo models.

The systematic analysis of stellar magnetism data revealed that for solar type stars there is a good correlation

between the cycle and rotation periods of the stars and that correlation is even stronger

when using the Rossby number (

![]() )

that takes into account the convection turnover time

)

that takes into account the convection turnover time ![]() at the base

of the stellar convective envelope (Noyes et al. 1984; Soon et al. 1993; Hempelmann et al. 1995; Baliunas et al. 1996).

As the star rotates faster, its cycle period is found to be shorter. Typically Noyes et al. (1984) found that

at the base

of the stellar convective envelope (Noyes et al. 1984; Soon et al. 1993; Hempelmann et al. 1995; Baliunas et al. 1996).

As the star rotates faster, its cycle period is found to be shorter. Typically Noyes et al. (1984) found that

![]() ,

with

,

with

![]() .

Based on an extended stellar sample Saar & Brandenburg (1999) and Saar (2002) have argued that there is actually two branches when plotting the cycle period vs. the rotation

period of the stars. They make the distinction between the primary (starspot) cycle and Gleissberg or grand minima

type modulation of the stellar activity. For the active branch they found an exponent

.

Based on an extended stellar sample Saar & Brandenburg (1999) and Saar (2002) have argued that there is actually two branches when plotting the cycle period vs. the rotation

period of the stars. They make the distinction between the primary (starspot) cycle and Gleissberg or grand minima

type modulation of the stellar activity. For the active branch they found an exponent

![]() and for the inactive stars

and for the inactive stars

![]() (Charbonneau & Saar 2001).

It is also found that this correlation breaks

at high rotation rate with the possible appearance of a super active

branch. Further at very high rotation rate saturation of the X-ray

luminosity seems to limit the validity of the scaling found at more

moderate rotation rates (Pizzolato et al. 2003). For G type stars

this saturation is found for rotation rate above 35 km s-1, for K type stars at about 10 km s-1 and for M dwarfs around

3-4 km s-1 (Browning 2008; Reiners et al. 2009). How stellar magnetic flux scales with rotation rate is thus also important

to understand since it is telling us how the magnetic field generated by dynamo action inside the stars emerges and imprints

the stellar surface (Rempel 2008) and if it actually saturates.

(Charbonneau & Saar 2001).

It is also found that this correlation breaks

at high rotation rate with the possible appearance of a super active

branch. Further at very high rotation rate saturation of the X-ray

luminosity seems to limit the validity of the scaling found at more

moderate rotation rates (Pizzolato et al. 2003). For G type stars

this saturation is found for rotation rate above 35 km s-1, for K type stars at about 10 km s-1 and for M dwarfs around

3-4 km s-1 (Browning 2008; Reiners et al. 2009). How stellar magnetic flux scales with rotation rate is thus also important

to understand since it is telling us how the magnetic field generated by dynamo action inside the stars emerges and imprints

the stellar surface (Rempel 2008) and if it actually saturates.

1.2 Possible theoretical interpretation

Theoretical considerations to interpret stellar magnetism based on classical mean field ![]() -

-![]() dynamo models (Durney & Latour 1976; Knobloch et al. 1981; Baliunas et al. 1996)

naturally find correlation between rotation rate and stellar activity.

In particular it is found that both magnetic field generation and the

dynamo number D

(i.e. a Reynolds number characterizing the mean field

dynamo models (Durney & Latour 1976; Knobloch et al. 1981; Baliunas et al. 1996)

naturally find correlation between rotation rate and stellar activity.

In particular it is found that both magnetic field generation and the

dynamo number D

(i.e. a Reynolds number characterizing the mean field ![]() and

and ![]() dynamo

effects used in the models) vary with the rotation period of the star.

This is due to the fact that in these models both effects are sensitive

to

the rotation rate of the star. The

dynamo

effects used in the models) vary with the rotation period of the star.

This is due to the fact that in these models both effects are sensitive

to

the rotation rate of the star. The ![]() -effect is a direct measure of the differential rotation

-effect is a direct measure of the differential rotation

![]() established

in the star. It is well known both theoretically and observationally

that the differential rotation in the convective envelope of

solar-type stars is directly connected to the star's rotation rate

established

in the star. It is well known both theoretically and observationally

that the differential rotation in the convective envelope of

solar-type stars is directly connected to the star's rotation rate ![]() (Donahue et al. 1996; Barnes et al. 2005; Ballot et al. 2007;

Brown et al. 2008; Küker & Rüdiger 2008). However, the exact scaling

(Donahue et al. 1996; Barnes et al. 2005; Ballot et al. 2007;

Brown et al. 2008; Küker & Rüdiger 2008). However, the exact scaling ![]() (i.e.

(i.e.

![]() )

is still a matter of debate among the observers and theoreticians,

being sensitive to the observational techniques used and to the

modelling approach.

)

is still a matter of debate among the observers and theoreticians,

being sensitive to the observational techniques used and to the

modelling approach.

The ![]() -effect

used in mean field theory is related to helical turbulence and

represents a measure or parameterization of the mean electromotive

force (emf) (Moffatt 1978; Pouquet et al. 1976). It is thus also linked to the

rotation rate of the star and the amount of kinetic helicity present in its convective envelope.

However in Babcock-Leighton flux transport dynamo models the standard

-effect

used in mean field theory is related to helical turbulence and

represents a measure or parameterization of the mean electromotive

force (emf) (Moffatt 1978; Pouquet et al. 1976). It is thus also linked to the

rotation rate of the star and the amount of kinetic helicity present in its convective envelope.

However in Babcock-Leighton flux transport dynamo models the standard ![]() -effect is replaced by a surface term linked to the

tilt of the active regions with respect to the east-west direction (i.e. Joy's law, Kosovichev & Stenflo 2008). This tilt is thought

to be due to the action of the Coriolis force during the rise of the toroidal structures that emerge as active regions

(D'Silva & Choudhuri 1993). Recent 3-D simulations in spherical shells (Fan 2008; Jouve & Brun 2007b, 2009)

seem to indicate

that this is not the only effect responsible for the observed tilt and

that the twist and arching of the toroidal structures as well as the

continuous action of the surface convection during the emergence have

some influence on the resulting tilt. Thus the

dependence with rotation rate of the Babcock-Leighton surface source

term used in this class of mean field dynamo models is not

straightforward

to assess and needs to be studied in detail.

-effect is replaced by a surface term linked to the

tilt of the active regions with respect to the east-west direction (i.e. Joy's law, Kosovichev & Stenflo 2008). This tilt is thought

to be due to the action of the Coriolis force during the rise of the toroidal structures that emerge as active regions

(D'Silva & Choudhuri 1993). Recent 3-D simulations in spherical shells (Fan 2008; Jouve & Brun 2007b, 2009)

seem to indicate

that this is not the only effect responsible for the observed tilt and

that the twist and arching of the toroidal structures as well as the

continuous action of the surface convection during the emergence have

some influence on the resulting tilt. Thus the

dependence with rotation rate of the Babcock-Leighton surface source

term used in this class of mean field dynamo models is not

straightforward

to assess and needs to be studied in detail.

Another important ingredient in flux transport models is the large

scale meridional circulation (MC) used to connect the surface source

term generating

the poloidal field to the region of strong shear at the base of the

convection zone (i.e. the tachocline) where it will be subsequently

sheared

by the ![]() -effect in order to close the global dynamo loop (i.e.

-effect in order to close the global dynamo loop (i.e.

![]() ).

The meridional flow (or ``conveyor belt'') thus plays an important role

in setting the cycle period of the global dynamo in this class of flux

transport model. As a direct consequence it is natural to ask how the

meridional circulation amplitude and profile change with

the rotation rate and how these may influence the magnetic cycle

period.

).

The meridional flow (or ``conveyor belt'') thus plays an important role

in setting the cycle period of the global dynamo in this class of flux

transport model. As a direct consequence it is natural to ask how the

meridional circulation amplitude and profile change with

the rotation rate and how these may influence the magnetic cycle

period.

Early work by Dikpati et al. (2001)

have assumed that the amplitude of the meridional flow is proportional

to the rotation rate of the star. With such scaling they seem to be

able to reproduce some of the

rotation vs cycle period correlation observed in solar type stars.

Charbonneau & Saar (2001)

have also studied the sensitivity of various

mean field dynamo models in reproducing stellar activity observations

assuming for the Babcock-Leighton type that the meridional flow

amplitude increases either as ![]() or

as

or

as

![]() .

Similarly Nandy (2004) and Nandy & Martens (2007)

have explored the solar-stellar connection with B-L mean field dynamo

models and have

reached the same conclusion: only a positive scaling of the amplitude

of meridional flows with the rotation rate can reconcile the models

with observations of magnetism of solar-like stars.

However recent theoretical work by Ballot et al. (2007) and

Brown et al. (2008) indicate that this is unlikely to be the right scaling. Instead 3-D simulations reveal that the amplitude of the meridional

flow weakens as the rotation rate is increased.

.

Similarly Nandy (2004) and Nandy & Martens (2007)

have explored the solar-stellar connection with B-L mean field dynamo

models and have

reached the same conclusion: only a positive scaling of the amplitude

of meridional flows with the rotation rate can reconcile the models

with observations of magnetism of solar-like stars.

However recent theoretical work by Ballot et al. (2007) and

Brown et al. (2008) indicate that this is unlikely to be the right scaling. Instead 3-D simulations reveal that the amplitude of the meridional

flow weakens as the rotation rate is increased.

In this paper we wish to revisit the solar-stellar connection in the light of the latest theoretical and observational work done in the community. We have thus designed a series of Babcock-Leighton models with the STELEM code (Emonet & Charbonneau 1998, private communication; Jouve & Brun 2007a) that incorporate recent 3-D MHD results. By doing so we will study how these mean field models, quite successful at modelling the solar cycle, perform to explain the observed magnetic activity, cycle and field topology of solar type stars at various rotation rates. In Sect. 2 we discuss the 2-D mean field models used in this study and the way we incorporate 3-D results obtained with the ASH code (Clune et al. 1999; Brun et al. 2004). In Sect. 3 we present our series of stellar mean field dynamo models, while in Sect. 4 we vary the input parameters to evaluate the robustness of our results. In Sect. 5 we discuss and put in perspective our results.

2 The models and method

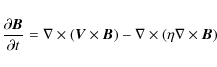

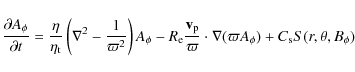

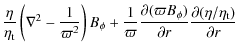

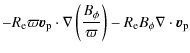

2.1 The model equation

To model the solar global dynamo operating in solar like stars, we use the hydromagnetic induction equation, governing the evolution of the magnetic field

|

(1) |

where

As we are working in the framework of mean-field theory, we express both magnetic and velocity fields as a sum

of large-scale (that will correspond to mean field) and small-scale (associated with fluid turbulence) contributions.

Averaging over some suitably chosen intermediate scale makes it possible to write two distinct induction equations for

the mean and the fluctuating parts of the magnetic field. The mean-field equation reads:

| |

= | ||

| (2) |

where

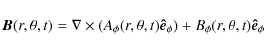

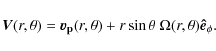

Working in spherical coordinates and under the assumption of axisymmetry, we write the total mean magnetic field B

and velocity field V as (for the sake of simplicity we omit

![]() in the rest of the paper):

in the rest of the paper):

|

(3) |

|

(4) |

Note that our velocity field is time-independent since we will not assume any fluctuations in time of the differential rotation

where

Equations (5) and (6)

are solved with the STELEM code (Emonet & Charbonneau 1998, private

communication) in an annular meridional plane with the colatitude ![]()

![]() and the

radius (in dimensionless units)

and the

radius (in dimensionless units)

![]() i.e. from slightly below the tachocline (r=0.7)

up to the solar surface.

The STELEM code has been thoroughly tested and validated thanks to an

international mean field dynamo benchmark involving 8 different

codes (Jouve et al. 2008).

At

i.e. from slightly below the tachocline (r=0.7)

up to the solar surface.

The STELEM code has been thoroughly tested and validated thanks to an

international mean field dynamo benchmark involving 8 different

codes (Jouve et al. 2008).

At ![]() and

and

![]() boundaries, both

boundaries, both ![]() and

and ![]() are set to 0. Both

are set to 0. Both ![]() and

and ![]() are set

to 0 at r=0.6. At the upper boundary, we smoothly match our solution to an external potential field, i.e. we have vacuum

for

are set

to 0 at r=0.6. At the upper boundary, we smoothly match our solution to an external potential field, i.e. we have vacuum

for ![]() .

As initial conditions we are setting a confined dipolar field configuration, i.e. the poloidal field is set to

.

As initial conditions we are setting a confined dipolar field configuration, i.e. the poloidal field is set to

![]() in

the convective zone and to 0 below the tachocline whereas the toroidal field is set to 0 everywhere.

in

the convective zone and to 0 below the tachocline whereas the toroidal field is set to 0 everywhere.

2.2 The physical ingredients

The rotation profile used in the series of models discussed in this

work captures some realistic aspects of the Sun's angular velocity,

deduced from helioseismic inversions (Thompson et al. 2003). We are thus

assuming a solid rotation below 0.66 and a differential rotation above the interface (cf. top panel of Fig. 1).

| |

= | ![$\displaystyle \Omega_{\rm c}+\frac{1}{2}\left[1+{\rm erf}(2\frac{r-r_{\rm c}}{d_{1}})\right]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/01/aa13103-09/img70.png)

|

|

| (7) |

with

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=7cm,clip]{13103f1a.ps}\par\vspace*{2mm}

\hspace*{2mm}\includegraphics[width=6.3cm,clip]{13103f1b.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/01/aa13103-09/Timg75.png)

|

Figure 1: Top panel: differential rotation profile used in the models G0.25 to G10 discussed Sect. 3. We zoomed on the tachocline region between r=0.6 and r=0.8. Bottom panel: meridional circulation used in the models G0.25 to G10 discussed Sect. 3. Plain (dashed) lines indicate counterclockwise (clockwise) circulation. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

We assume that the diffusivity in the envelope ![]() is dominated by its turbulent contribution whereas in the stable interior

is dominated by its turbulent contribution whereas in the stable interior

![]() .

We smoothly match the two different constant values with an error function which enables us to

quickly and continuously transit from

.

We smoothly match the two different constant values with an error function which enables us to

quickly and continuously transit from

![]() to

to

![]() i.e.

i.e.

with

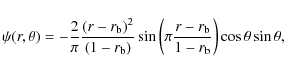

In Babcock-Leighton (BL) flux-transport dynamo models, the poloidal

field owes its origin to the tilt of magnetic loops emerging at the

solar surface. Thus, the source has to be confined to a thin layer just

below the surface and since the process is fundamentally non-local, the

source term depends on the variation of ![]() at the base of the convection zone (CZ). The expression is

at the base of the convection zone (CZ). The expression is

| |

= | ![$\displaystyle \frac{1}{2}\left[1+{\rm erf}\left(\frac{r-r_{2}}{d_{2}}\right)\right]\left[ 1-{\rm erf}\left(\frac{r-1}{d_{2}}\right)\right]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/01/aa13103-09/img81.png)

|

|

![$\displaystyle \times\left[1+\left({\frac{B_{\phi}(r_{\rm c},\theta,t)}{B_{0}}}\right)^{2}\right]^{-1}\cos\theta \sin\theta B_{\phi}(r_{\rm c},\theta,t)$](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/01/aa13103-09/img82.png)

|

where r2=0.95, d2=0.01,

In these BL flux-transport dynamo models, meridional

circulation is used to link the two sources of the magnetic

field namely the base of the CZ and the solar surface. The

structure of the meridional circulations in the Sun is less

constrained than the internal differential rotation, as they

possess slower flows that are difficult to detect

helioseismically. The nature of these flows in other stars is

even less constrained. It is generally believed that in the Sun,

the meridional circulations are likely to be composed largely of a

single cell in each hemisphere, and recent solar simulations

(Miesch et al. 2008) find such single-celled structures when the

global-scale flows are averaged over long intervals but multi-cellular profiles can also be realized.

In more rapidly rotating suns, 3-D models presently indicate that the

circulations are likely to be multi-celled in both radius and

latitude (Ballot et al. 2007; Brown et al. 2008).

In the series of models discussed in Sect. 3 of this paper,

we restrict ourselves to Babcock-Leighton flux-transport models

that have a large single cell per hemisphere. We choose this

simple profile because it is widely used in the community,

although some studies have considered more complex profiles (Bonanno et al. 2005; Jouve & Brun 2007a).

We are deferring to Sect. 4.2 the analysis of complex multi-cellular profiles.

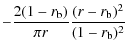

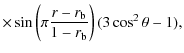

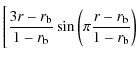

As in the Sun, the meridional circulations are

directed poleward at the surface and here they vanish at the

bottom boundary (r=0.6) and thus penetrate a little beneath the

tachocline into the radiative interior (cf. bottom panel of Fig. 1). To model the single cell meridional circulation

we consider a stream function with the following expression:

which gives, through the relation

| |

= |

|

|

|

(10) |

| |

= |

|

|

![$\displaystyle +\frac{r\pi}{1-r_{\rm b}}\frac{(r-r_{\rm b})}{(1-r_{\rm b})} \cos\left(\pi\frac{r-r_{\rm b}}{1-r_{\rm b}}\right)\Bigg]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/01/aa13103-09/img91.png)

|

|||

| (11) |

with

3 Flux transport models as a function of rotation rate

3.1 Previous results

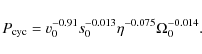

Jouve & Brun (2007a) have done a systematic study of the influence on the cycle period of the various parameters of Babcock-Leighton flux transport models. For the reference model possessing only one cell per hemisphere they confirm the results of Dikpati & Charbonneau (1999) that the cycle period is strongly dependent on the meridional circulation amplitude. A least square fit through the ensemble of models they computed leads to the following dependency:

We can thus expect that as we increase the rotation rate the cycle period will shorten if all the other parameters are kept constant but unfortunately not as fast as what is observed (Noyes et al. 1984; Saar 2002). However we may also expect the meridional circulation to depend on the rotation rate, and the sign of the variation of v0 with

3.2 Implementing results from 3D simulations of rapidly rotating stars in our mean field dynamo models

In order to get some physical insight on how the meridional circulation varies with the rotation rate we rely on recent 3-D numerical simulations of solar convection performed with the ASH code (Brun & Toomre 2002; Ballot et al. 2007; Brown et al. 2008). Indeed there are no reliable observations of the meridional circulation in stars except for the Sun near the surface. The theoretical work of Brown et al. (2008), that studies the influence of the rotation rate on solar like stars (i.e. with the same thickness for the convection zone as our current Sun), will provide the required scaling. In this work several 3-D purely hydrodynamical models have been computed at various rotation rates (from 1 to 10 times solar) and the redistribution of angular momentum, heat and energy assessed systematically to explain the differential rotation and meridional circulations achieved in the simulations. Figures 10 and 12 of Brown et al. (2008) are particularly relevant to our study and we have used the data from all the models reported in these figures plus more slowly rotating cases (i.e. with a rotation rate lower than the solar rate) that are currently being studied (Brown 2009).

Table 1:

Summary of the different cases studied and the values of ![]() and

and ![]() used in the 2D Babcock-Leighton models.

used in the 2D Babcock-Leighton models.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=6.6cm,clip]{13103f2a.eps}\par\vspace*{...

...2mm}

\includegraphics[width=6.6cm,clip]{13103f2d.eps} \vspace{-3mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/01/aa13103-09/Timg108.png)

|

Figure 2:

Butterfly diagrams for cases G0.5, G1, G5 and G10. The top panel shows the time-latitude cut of the toroidal field at the base of the

convection zone and the bottom one represents the evolution of the radial field at the surface. Time is in years. The scale of the color

table is the same for all: between

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

We have thus scaled the meridional circulation by taking into account the way meridional circulation kinetic energy (MCKE)

is found to change with rotation in the published 3-D models of Brown et al. (2008).

We are confident that this scaling for MCKE still holds in the

magnetized version since recent 3-D models of dynamo action in rapidly

rotating suns find that the weak meridional circulations are

essentially unmodified by the strong magnetic fields that are generated

(Brown et al. 2009).

In contrast, the differential rotation appears to be substantially different

from that found in hydrodynamic cases, and its scaling with

rotation rate is sensitive to magnetic fields that are realized. We will thus not use the scaling

of

![]() with

with ![]() found in Brown et al. (2008) when we will vary the differential

rotation profile in our models but instead rely on observations (see Sect. 4.1 below).

found in Brown et al. (2008) when we will vary the differential

rotation profile in our models but instead rely on observations (see Sect. 4.1 below).

In Table 1, we list the solar-like mean field dynamo models that we have computed at various rotation rate along with

the associated Reynolds numbers ![]() and

and ![]() that we have used in our 2-D models. A quick look at the table already

reveals that the meridional circulation amplitude decreases with

rotation rate. This may come as a surprise as one could have expected

faster meridional flows as

that we have used in our 2-D models. A quick look at the table already

reveals that the meridional circulation amplitude decreases with

rotation rate. This may come as a surprise as one could have expected

faster meridional flows as ![]() is increased. However a careful study, via the longitudinal component

of the vorticity equation, of the maintenance of the meridional

circulation (which arises from small unbalance between large forces;

see for instance Miesch 2005; Brun & Rempel 2008), reveals that it

actually weakens with faster rotation rate.

It is thus likely given the strong negative dependency of

is increased. However a careful study, via the longitudinal component

of the vorticity equation, of the maintenance of the meridional

circulation (which arises from small unbalance between large forces;

see for instance Miesch 2005; Brun & Rempel 2008), reveals that it

actually weakens with faster rotation rate.

It is thus likely given the strong negative dependency of

![]() with v0

that

as we increase the rotation rate, the cycle period will increase rather

than decrease as observed. However it is not obvious to anticipate the

resulting field topology of the various models without actually

computing them.

with v0

that

as we increase the rotation rate, the cycle period will increase rather

than decrease as observed. However it is not obvious to anticipate the

resulting field topology of the various models without actually

computing them.

Incorporating the values of the dynamo numbers ![]() and

and ![]() for

the different stars in our flux-transport BL dynamo models enables us

to study the behaviour of the mean magnetic field in such stars in the

framework of mean-field theory. All the dynamo models we have studied

give cyclic behaviours with different periods and different intensity

of the mean toroidal and poloidal magnetic fields.

We wish to stress that even though the naming scheme of the models

discussed in this paper is similar to that used in Brown et al. (2008), the models are distinct since the ones discussed in this work are 2-D not 3-D.

for

the different stars in our flux-transport BL dynamo models enables us

to study the behaviour of the mean magnetic field in such stars in the

framework of mean-field theory. All the dynamo models we have studied

give cyclic behaviours with different periods and different intensity

of the mean toroidal and poloidal magnetic fields.

We wish to stress that even though the naming scheme of the models

discussed in this paper is similar to that used in Brown et al. (2008), the models are distinct since the ones discussed in this work are 2-D not 3-D.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.4cm,clip]{13103f3.eps} \vspace{-6mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/01/aa13103-09/Timg109.png)

|

Figure 3:

Representative solution of a BL model applied to a

rapidly rotating star. This is case G5, with a rotation rate |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Figure 2 gives examples of 4 different butterfly diagrams obtained for more or less rapidly rotating stars. This figure shows the evolution in time of the toroidal magnetic field at the bottom of the CZ and of the radial field at the top of the domain. We note that the behaviour of the field is very similar in all these models, except that the period is clearly varying as well as the intensity of the magnetic field (the scale of the color table is the same for all panels). Indeed, we note that the magnetic cycle period is increased when the rotation rate is increased. This is a direct consequence of the fact that the cycle period is almost inversely proportional to the amplitude of the meridional flow in BL models.

In order to illustrate the temporal evolution of the magnetic field in the meridional plane, we display in Fig. 3 a temporal sequence over one starspot cycle for model G5. The advection of the field by the single-celled meridional circulation is evident confirming that our dynamo model is dominated by advection and not by diffusion. We wish to stress here that our particular choice of advection-dominated regime is not the only possibility at hand to model the transport occurring in the solar convection zone and the manner that the models link the Babcock-Leighton surface source term to the deep tachocline. For instance Chatterjee et al. (2004), Käpylä et al. (2006), Yeates et al. (2008), Guerrero & Gouveia Dal Pino (2008) have studied how transporting the poloidal field from the surface to the tachocline via turbulent diffusion or turbulent pumping influence the butterfly diagram, the polarity of the field and the cycle period. We intend to look at these solutions in the near future.

Returning to Fig. 3 we also note that the poloidal field tends to be more

concentrated near the polar region in agreement with the stronger polar branch seen in the corresponding butterfly diagram.

Indeed in Fig. 2 we clearly note that the magnetic intensity is increased when the rotation rate is increased,

which is in agreement with the observations.

We finally also note on the poloidal field that the contrast between the polar intensity and the

intensity close to the equator is diminished when the rotation rate is increased.

3.3 Field topology and poloidal vs. toroidal field ratio

It is clear that the evolution of the field topology as a function of the rotation rate is of great importance. We are thus summarizing in Table 2 and on the curves of Fig. 4 how the field intensity and topology is changing with

Table 2: Starspot cycle period (in year), maximum of toroidal field (in 104 G) at the base of the CZ and ratio between poloidal and toroidal field for 10 different cases with various rotation rates.

![\begin{figure}

\par\hspace*{2mm}\includegraphics[width=6.8cm,clip]{13103f4a.ps}\...

...2mm}

\includegraphics[width=7cm,clip]{13103f4d.eps}

\vspace{-4mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/01/aa13103-09/Timg110.png)

|

Figure 4:

Top panel: variation of the magnetic cycle period wih respect to the amplitude of the MC and ( 2nd panel) to the rotation rate

for the cases G1 to G10. On the third panel

we display the variation of the maximum of toroidal field at the base

of the CZ for two series of models. The solid line corresponds to the

models G1 to G10 using the scaled

down meridional flow as a function of the rotation rate whereas the

dotted line corresponds to another set of models for which v0 was kept constant.

On the bottom panel, we show the ratio

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

More precisely on the first (top) panel of Fig. 4,

we recover the almost proportional relationship between the magnetic

cycle period and the inverse of the meridional flow amplitude. This

again shows the major impact of the meridional circulation in these

Babcock-Leighton dynamo models on the cycle period.

As stated in Brown et al. (2008),

the meridional circulation kinetic energy in 3-D hydrodynamical (HD)

models of rapidly rotating stars seems to scale as approximately

![]() ,

leading the averaged meridional flow amplitude to scale as

,

leading the averaged meridional flow amplitude to scale as

![]() .

Indeed, on the second panel of Fig. 4 where we show the cycle period plotted against the rotation rate of the star,

we naturally recover a scaling in

.

Indeed, on the second panel of Fig. 4 where we show the cycle period plotted against the rotation rate of the star,

we naturally recover a scaling in

![]() .

A star rotating at

.

A star rotating at

![]() for example would have a cycle period of about 26 years approximately

40.45=1.87 times

the period of 15.1 years of case G2 rotating at twice the solar rate.

for example would have a cycle period of about 26 years approximately

40.45=1.87 times

the period of 15.1 years of case G2 rotating at twice the solar rate.

More interestingly, if we now focus on the third and fourth (bottom) panels of Fig. 4, we note that the amplitude of the toroidal field possesses an almost linear

dependency on the rotation rate ![]() .

This property is due mainly to two effects: a) a larger

.

This property is due mainly to two effects: a) a larger ![]() -effect (via its dependence on the Reynolds number

-effect (via its dependence on the Reynolds number

![]() )

in more rapidly rotating stars and b) the fact that the reduction of

the meridional flow amplitude allows the poloidal field to be stretched

and amplified over a longer period of time

(see Nandy (2004) and Yeates et al. (2008) who are finding similar effects).

This is evident by comparing on the third panel of Fig. 4

the solid and dashed curves. The difference between the two curves is

the amplitude of

the meridional flow as a function of rotation rate that we kept

constant for the cases shown using dashed line (these models

were used to determine the least square fit of Eq. (12)). We

clearly see that both series of models lead to larger toroidal field as

we increase the rotation rate

but for the series with the scaled down meridional flow, the

strengthening of

)

in more rapidly rotating stars and b) the fact that the reduction of

the meridional flow amplitude allows the poloidal field to be stretched

and amplified over a longer period of time

(see Nandy (2004) and Yeates et al. (2008) who are finding similar effects).

This is evident by comparing on the third panel of Fig. 4

the solid and dashed curves. The difference between the two curves is

the amplitude of

the meridional flow as a function of rotation rate that we kept

constant for the cases shown using dashed line (these models

were used to determine the least square fit of Eq. (12)). We

clearly see that both series of models lead to larger toroidal field as

we increase the rotation rate

but for the series with the scaled down meridional flow, the

strengthening of ![]() is even higher. As a result, in our set of 2-D BL dynamo models the

poloidal to toroidal

field ratio is found to increase almost linearly with the rotation

period (inversely proportional to the rotation rate as seen on the last

panel of Fig. 4).

This is in reasonable agreement with the observations of rapidly rotating solar-like stars by Petit et al. (2008). However the scaling of

is even higher. As a result, in our set of 2-D BL dynamo models the

poloidal to toroidal

field ratio is found to increase almost linearly with the rotation

period (inversely proportional to the rotation rate as seen on the last

panel of Fig. 4).

This is in reasonable agreement with the observations of rapidly rotating solar-like stars by Petit et al. (2008). However the scaling of

![]() /

/

![]() found in recent 3-D MHD

simulations computed by Brown et al. (2009)

is not linear. Moreover, the observations indicate that the energy

stored in the large-scale toroidal

component of the magnetic field tends to dominate for rotation periods

lower than 12 days (corresponding approximately to a rotation rate of

twice the solar one). In our cases, the toroidal

field is always dominant, even for the case with

found in recent 3-D MHD

simulations computed by Brown et al. (2009)

is not linear. Moreover, the observations indicate that the energy

stored in the large-scale toroidal

component of the magnetic field tends to dominate for rotation periods

lower than 12 days (corresponding approximately to a rotation rate of

twice the solar one). In our cases, the toroidal

field is always dominant, even for the case with

![]() where the poloidal field hardly reaches

where the poloidal field hardly reaches ![]() of the toroidal field.

of the toroidal field.

This discrepancy could be due to the fact that the values quoted in Petit et al. (2008) are related to observationally detectable fields, i.e. to surface fields; whereas the values we quote in this work are related to the magnetic fields in the whole convection zone. If the strong toroidal fields stored at the base of the convection zone are not able to reach the solar surface (as it is the case under certain conditions, see Jouve & Brun 2009 for more details), the surface measurements could underestimate the amount of magnetic energy stored in the toroidal fields in the whole stellar convective envelope.

4 Varying the model parameters

From the above set of models it is clear that just increasing the rotation rate of the model and/or implementing a scaled meridional circulation amplitude is not sufficient to reproduce the fast (close to linear) reduction of the stellar cycle period with the rotation rate. We thus wish in this section to modify all the other parameters in order to find the best set of models to reproduce the observations.

The first easiest modification is to change the value of the diffusivity or of the constant s0 used in the model. From the least square fit shown in Eq. (12)

the weak dependency of

![]() on

on ![]() or s0

indicates that it is unlikely that such a modification will be able to

reproduce the observations. We thus need to look for more sophisticated

solutions. In order to make the discussion easy to follow and to reduce

the number of models considered we will now limit our study to cases

rotating at five times the solar rate. Of course our results

are easily transposable to other rotation rates.

or s0

indicates that it is unlikely that such a modification will be able to

reproduce the observations. We thus need to look for more sophisticated

solutions. In order to make the discussion easy to follow and to reduce

the number of models considered we will now limit our study to cases

rotating at five times the solar rate. Of course our results

are easily transposable to other rotation rates.

4.1 Modifying the differential rotation profile

As discussed in the introduction it is clear that in low mass stars

the differential rotation is expected to change with the rotation rate.

Given the key role played

by the ![]() -effect

in mean field dynamo, we propose to compute a new model at 5 times the

solar rate with a modified differential rotation, namely case G5om. But

what scaling of

-effect

in mean field dynamo, we propose to compute a new model at 5 times the

solar rate with a modified differential rotation, namely case G5om. But

what scaling of

![]() with

with ![]() should we use?

In their 3-D hydrodynamic models, Brown et al. (2008) find a scaling of

should we use?

In their 3-D hydrodynamic models, Brown et al. (2008) find a scaling of

![]() .

However due to the nonlinear feed back of the Lorentz force on the mean

longitudinal flow, this scaling is not recovered in the MHD models

computed in Brown et al. (2009). We thus choose here not to use the theoretical scaling for

.

However due to the nonlinear feed back of the Lorentz force on the mean

longitudinal flow, this scaling is not recovered in the MHD models

computed in Brown et al. (2009). We thus choose here not to use the theoretical scaling for

![]() of Brown et al. (2008)

since it is somewhat uncertain and depends on whether or not dynamo

action is realized in the simulations.

The observational situation is not clearer with either a weak scaling

close to zero (i.e. the differential rotation does not vary with the

rotation rate; Barnes et al. 2005) or strong scaling as in Donahue et al. (1996). Given the current debate going on among the observers on the exact variation of

of Brown et al. (2008)

since it is somewhat uncertain and depends on whether or not dynamo

action is realized in the simulations.

The observational situation is not clearer with either a weak scaling

close to zero (i.e. the differential rotation does not vary with the

rotation rate; Barnes et al. 2005) or strong scaling as in Donahue et al. (1996). Given the current debate going on among the observers on the exact variation of

![]() with

with ![]() we have some freedom in the choice of our variation. We choose here to follow the scaling proposed by Donahue et al. (1996), i.e.

we have some freedom in the choice of our variation. We choose here to follow the scaling proposed by Donahue et al. (1996), i.e.

![]() since it is the most extreme variation found among the observers and as

a

consequence it will maximize the effect of varying the differential

rotation profile. The new differential rotation profile is shown on the

top panel of Fig. 5 and is directly comparable with the one shown on the top panel of Fig. 1.

We also display on the bottom panel of Fig. 5 the butterfly diagram for this new model G5om rotating at 5 times the solar rate with increased

since it is the most extreme variation found among the observers and as

a

consequence it will maximize the effect of varying the differential

rotation profile. The new differential rotation profile is shown on the

top panel of Fig. 5 and is directly comparable with the one shown on the top panel of Fig. 1.

We also display on the bottom panel of Fig. 5 the butterfly diagram for this new model G5om rotating at 5 times the solar rate with increased

![]() .

.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=7cm,clip]{13103f5a.ps}\par\vspace*{2mm}

\includegraphics[width=7.5cm,clip]{13103f5b.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/01/aa13103-09/Timg119.png)

|

Figure 5:

Top panel: new differential rotation used in the model G5om zoomed on the portion between r=0.6 and r=0.8. For that case

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

We see that the cycle period is almost not affected by the increase of

the latitudinal shear when comparing the butterfly diagram of Fig. 5 with the third panel of Fig. 2.

This confirms that the ![]() -effect

plays little role in setting the cycle period in BL dynamo models.

On the contrary the ratio between Bpol and Btor is changed. Indeed, for

this case, we go from a Bpol to Btor ratio of 0.05 in the standard case

G5 to a ratio of 0.019 in G5om. We thus proceeded in this case to a

significant increase of the toroidal component of the magnetic field,

keeping the value for the poloidal field approximately the same. This

is due to the fact that this new class of models is generating stronger

Btor as can be expected with a larger shear. A precise observation of

this ratio may thus be of utility to put constraints on stellar

internal differential rotation.

-effect

plays little role in setting the cycle period in BL dynamo models.

On the contrary the ratio between Bpol and Btor is changed. Indeed, for

this case, we go from a Bpol to Btor ratio of 0.05 in the standard case

G5 to a ratio of 0.019 in G5om. We thus proceeded in this case to a

significant increase of the toroidal component of the magnetic field,

keeping the value for the poloidal field approximately the same. This

is due to the fact that this new class of models is generating stronger

Btor as can be expected with a larger shear. A precise observation of

this ratio may thus be of utility to put constraints on stellar

internal differential rotation.

With a larger latitudinal shear it is expected that the tachocline at

the base of the stellar convection zone will also be modified. The

tachocline is

the transition region between the differentially rotating convective

envelope of low mass star and their supposedly uniformly rotating

radiative interior. How

the tachocline thickness is varying with the rotation rate and the

differential rotation of the star is not easy to determine. Based on

the

tachocline model of Spiegel & Zahn (1992) and the observations of

Donahue et al. (1996) for the dependency of

![]() with

with ![]() ,

Brun et al. (1999) have shown that the tachocline thickness for a younger more rapidly

rotating Sun could be thicker. They find a scaling for

,

Brun et al. (1999) have shown that the tachocline thickness for a younger more rapidly

rotating Sun could be thicker. They find a scaling for

![]() when taking into account all the dependencies. We have thus computed a

new model G5omt,

with both a larger tachocline (about twice as large in this case than

in case G5om, following the scaling law quoted above) and stronger

differential rotation (identical to case G5om shown on Fig. 5, with a

when taking into account all the dependencies. We have thus computed a

new model G5omt,

with both a larger tachocline (about twice as large in this case than

in case G5om, following the scaling law quoted above) and stronger

differential rotation (identical to case G5om shown on Fig. 5, with a

![]() about three times the solar one). The result in term of the cycle

period is again difficult to distinguish from the standard G5 model,

that had only

about three times the solar one). The result in term of the cycle

period is again difficult to distinguish from the standard G5 model,

that had only

![]() and the meridional circulation amplitude changed. This confirms that the

tachocline plays almost no role in Babcock-Leighton dynamo models in setting the cycle period.

On the contrary the ratio

and the meridional circulation amplitude changed. This confirms that the

tachocline plays almost no role in Babcock-Leighton dynamo models in setting the cycle period.

On the contrary the ratio

![]() /

/

![]() is modified being intermediate between the cases G5 and G5om. The value

of the ratio is now of about 0.02, very close to the case where the

differential rotation was increased, but with a slight reduction of the

toroidal component, due to the softer transition (i.e. thicker

tachocline). In summary neither models G5om nor G5omt possess a

cycle period in agreement with the observations and we thus need to

modify another physical ingredient.

is modified being intermediate between the cases G5 and G5om. The value

of the ratio is now of about 0.02, very close to the case where the

differential rotation was increased, but with a slight reduction of the

toroidal component, due to the softer transition (i.e. thicker

tachocline). In summary neither models G5om nor G5omt possess a

cycle period in agreement with the observations and we thus need to

modify another physical ingredient.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=7cm,clip]{13103f6.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/01/aa13103-09/Timg121.png)

|

Figure 6: Multicellular stream function for the case rotating at 5 times the solar rate G5mc20. Two cells with latitude have been used, with the first poleward cell near the equator closing at 20 deg of latitude. On the left panel we show the streamfunction and on the right panel the latitudinal velocity at 3 depths. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

In the standard Babcock-Leighton model we are thus left with two possibilities if we want to reconcile the models and the observations: modifying the profile of meridional circulation or introducing the effects of a faster rotation rate on the surface source term. Indeed, for example it has been shown by D'Silva & Choudhuri (1993) that the Coriolis force could strongly act on the tilt angle of emerging active regions, thus modifying the source term for poloidal field. This feature will have to be checked in future works, with the help of 3-D MHD models such as the ones of Jouve & Brun (2009). For this work, since the dependence of the cycle period on the amplitude of the meridional flow is very strong, we decide to focus on the first solution: modifying the MC profile.

4.2 Varying the number of meridional circulation cells

The strong relation between the meridional circulation speed and the cycle activity is an indication that shortening the advection path may result in shorter cycle period. Dikpati et al. (2004), Bonanno et al. (2005) and Jouve & Brun (2007a) have studied in detail the influence of various meridional circulation profiles on the butterfly diagram and other large scale magnetic properties of the Sun.

In particular Jouve & Brun (2007a) have shown that adding cells in radius slows down the cycle whereas as the two other groups also showed, adding cells in latitude accelerates it. If one seeks to shorten the cycle length as it is the case in this study, only adding cells in latitude will have the expected impact. We have thus computed a new set of simulations, rotating at five times the solar rate in which we have only modified the meridional circulation in latitude (leaving all the other parameters the same as in case G5) by considering two cells in latitude per hemisphere with various extension instead of just one cell.

Following the 3-D results of Brown et al. (2008)

and particularly Fig. 11 of their article, we choose to introduce

a meridional circulation with a counterclockwise cell at lower

latitudes and a clockwise cell at higher latitudes in the Northern

hemisphere, this profile being antisymmetric with respect to the

equator. Since uncertainties are significant concerning

the extension of the low-latitude meridional cell, we have computed

several models at 5 times the solar rate including a low-latitude cell

extending to

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

,

![]() and

and

![]() ,

named respectively G5mc45, G5mc40, G5mc30 and G5mc20. For the sake of

clarity we have decided to illustrate and discuss in length in this

section only one case, namely case G5mc20, the model with the less

extended lower meridional circulation cell. The meridional circulation

profile for that case is shown in Fig. 6

for illustration. In all models we have set the latitudinal velocity

such that it has the same maximal amplitude in the two counter-cells

which correspond to that in the case with one single cell (i.e. case

G5) keeping all the other parameters the same.

,

named respectively G5mc45, G5mc40, G5mc30 and G5mc20. For the sake of

clarity we have decided to illustrate and discuss in length in this

section only one case, namely case G5mc20, the model with the less

extended lower meridional circulation cell. The meridional circulation

profile for that case is shown in Fig. 6

for illustration. In all models we have set the latitudinal velocity

such that it has the same maximal amplitude in the two counter-cells

which correspond to that in the case with one single cell (i.e. case

G5) keeping all the other parameters the same.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=7.5cm,clip]{13103f7.ps} \vspace{-4mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/01/aa13103-09/Timg126.png)

|

Figure 7: Butterfly diagram of the case G5mc20, rotating at 5 times the solar rotation rate and possessing a multicellular meridional flow as shown in Fig. 6. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

When comparing the various multi-cellular stellar dynamo simulations,

we find that the scaling of the cycle period with the extension of the

low-latitude cell is almost linear, the starspot cycle period being

respectively of 9.9, 9.2, 7.4 and 5.2 years for those different models.

This is mainly due to the fact that the advection path is reduced by

the presence of counter-cells and will shorten the distance each

component of the magnetic field has to travel before reaching the

region where it will be turned into the other component. According to

the previous studies and scaling laws of Noyes et al. (1984), Saar & Brandenburg (1999), Charbonneau & Saar (2001) and Saar (2002),

the cycle period for a star rotating at 5 times the rotation rate

should be around 3 years. We are getting very close to this value

with a low-latitude cell extending to

![]() in latitude as in case G5mc20. We now focus on butterfly diagram and

the evolution of the field in the meridional plane of this model, as

shown in Figs. 7 and 8.

in latitude as in case G5mc20. We now focus on butterfly diagram and

the evolution of the field in the meridional plane of this model, as

shown in Figs. 7 and 8.

On the butterfly diagram shown in Fig. 7,

we clearly see that we have significantly reduced the length of the

activity (starspot) cycle: the period is now 5.2 yr instead of

20.8 yr. The cyclic activity tends now to be more concentrated at

low latitudes. The temporal evolution of the field seems to be less

steady if we consider the variations of intensity which appear from one

cycle to the next, visible on the butterfly diagram through changes in

color between the different activity cycles. The radial field appears

to be even more busy, exhibiting a periodic but yet complex pattern at

low latitudes. We moreover note

that above

![]() ,

the cyclic activity is lost and we are left with some regions where the magnetic field evolves much more slowly than the

time scale of the main cycle.

,

the cyclic activity is lost and we are left with some regions where the magnetic field evolves much more slowly than the

time scale of the main cycle.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm]{13103f8.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/01/aa13103-09/Timg128.png)

|

Figure 8: Same as Fig. 3 but for the case G5mc20 rotating at 5 times the rotation rate and possessing a multicellular meridional circulation as shown in Fig. 6. The evolution is shown over a temporal interval of 5.2 years corresponding to half a magnetic cycle or one starspot cycle. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Looking at Fig. 8 will help us to have more insight on how the field is organized in the convective envelope and how it is advected by the new meridional circulation. Again, we clearly see that the evolution of the field is much more complicated than in the standard case. We can still follow the evolution of each component of the field on the various panels of the figure. Indeed we can distinguish the effect of the low-latitude cell which advects the newly generated poloidal field (counterclockwise on the first panel) downwards while the toroidal field of the previous cycle (positive i.e. represented by reddish colours) is being advected at the base of the convection zone to reach the equator and replace the toroidal field of the previous cycle at the end of the starspot cycle (last panel). We note, in agreement with the butterfly diagram, that the advection at higher latitudes is much slower and as a consequence we do not clearly see any imprint of the activity cycle in the polar regions. This is due to the fact that the same amplitude of the flow is introduced for both cells and that the distance traveled by the field at low latitudes is much shorter, thus leading to a difference in the time-scale for the advection of the magnetic field in the two cells. We also wish to reemphasize that we did not introduce multi cells in radius since Jouve & Brun (2007a) showed that it results in a slowing down of the cycle period rather than a speeding up as required in this study for fastly rotating stars. In summary adding cell in latitude clearly helps shortening the cycle for fastly rotating stars. For the stars rotating slower than the Sun it may be necessary to add cells in radius if one wants to increase the cycle. Indeed 3-D models indicate that slower the star rotates faster its meridional circulation is and thus shorter its cyclic period will be as demonstrated by the butterfly diagram shown on the top panel of Fig. 2 for case G0.5.

5 Summary and conclusions

The idea of this work was to better understand stellar magnetism, using

both 2-D and 3-D calculations. To do so, we have introduced into

Babcock-Leighton (B-L) flux transport dynamo models, results from 3-D

global hydrodynamical simulations by Brown et al. (2008).

To be more specific we have used these simulations to determine the

variation of the amplitude of the meridional circulation with rotation

rate and complemented our study with observations of the variation of

the angular velocity contrast

![]() with rotation rate. Using these scaling laws we have built a series of 2-D mean field stellar dynamo models in which

we have modified in turn the rotation rate, the amplitude of the meridional circulation and of the angular velocity gradient.

This has allowed us to test the validity of this type of models on solar-like stars with faster rotations and intense magnetism.

with rotation rate. Using these scaling laws we have built a series of 2-D mean field stellar dynamo models in which

we have modified in turn the rotation rate, the amplitude of the meridional circulation and of the angular velocity gradient.

This has allowed us to test the validity of this type of models on solar-like stars with faster rotations and intense magnetism.

Our study shows that an increase in the rotation rate leads to a larger ![]() -effect which in turn modifies the ratio between

poloidal and toroidal fields with a trend similar to that found observationally in a

small sample of rapidly rotating suns (Petit et al. 2008).

Other authors have also studied such trends using solar mean field B-L

flux transport dynamo models (see for instance Charbonneau & Saar 2001; Dikpati et al. 2001; Nandy & Martens 2007).

They also find that the toroidal field grows in amplitude with the

star's rotation rate.

The difference between our work and previous studies comes from the

choice made in varying the meridional circulation amplitude with

rotation rate. In 3-D global calculations an increase of the rotation

rate leads to a decrease in the meridional flow amplitude whereas in

previous studies the opposite was assumed since such knowledge was not

yet available. Given that the cycle period in advection-dominated B-L

dynamo models is almost inversely proportional to the intensity of the

meridional circulation, we find that our models predict slower magnetic

cycles for more rapidly rotating stars. This is not consistent with the

observational data collected at Mount Wilson since the 1960's (e.g.

Noyes et al. 1984; Baliunas et al. 1995).

It thus seems difficult to reconcile advection-dominated B-L models

widely used in the solar dynamo community with stellar activity

observations if we use scaling laws relating

rotation rates and meridional flow amplitudes given by consistent 3-D

models. Of course the systematic observation of the meridional

circulation realized in solar-like stars rotating at various rotation

rate would

be of great use and could solve the apparent discrepancy if we indeed

found that such flows are not so sensitive to the rotation rate.

Unfortunately such observations are not yet available. Hopefully with

the Corot and Kepler satellites now in orbit this situation may change

in the near future.

-effect which in turn modifies the ratio between

poloidal and toroidal fields with a trend similar to that found observationally in a

small sample of rapidly rotating suns (Petit et al. 2008).

Other authors have also studied such trends using solar mean field B-L

flux transport dynamo models (see for instance Charbonneau & Saar 2001; Dikpati et al. 2001; Nandy & Martens 2007).

They also find that the toroidal field grows in amplitude with the

star's rotation rate.

The difference between our work and previous studies comes from the

choice made in varying the meridional circulation amplitude with

rotation rate. In 3-D global calculations an increase of the rotation

rate leads to a decrease in the meridional flow amplitude whereas in

previous studies the opposite was assumed since such knowledge was not

yet available. Given that the cycle period in advection-dominated B-L

dynamo models is almost inversely proportional to the intensity of the

meridional circulation, we find that our models predict slower magnetic

cycles for more rapidly rotating stars. This is not consistent with the

observational data collected at Mount Wilson since the 1960's (e.g.

Noyes et al. 1984; Baliunas et al. 1995).

It thus seems difficult to reconcile advection-dominated B-L models

widely used in the solar dynamo community with stellar activity

observations if we use scaling laws relating

rotation rates and meridional flow amplitudes given by consistent 3-D

models. Of course the systematic observation of the meridional

circulation realized in solar-like stars rotating at various rotation

rate would

be of great use and could solve the apparent discrepancy if we indeed

found that such flows are not so sensitive to the rotation rate.

Unfortunately such observations are not yet available. Hopefully with

the Corot and Kepler satellites now in orbit this situation may change

in the near future.

We have thus tried to investigate ways to improve the agreement

between 2-D models and observations in refining our calculations. A

least-square fit on the various parameters of the standard model

shows that we cannot rely on a modifications of ![]() ,

s0 and

,

s0 and ![]() to act on the cycle period, as the latter is almost completely

determined by the amplitude of the meridional flow (see Eq. (12)).

We thus computed more sophisticated models where the differential

rotation and meridional circulation profiles were modified.

to act on the cycle period, as the latter is almost completely

determined by the amplitude of the meridional flow (see Eq. (12)).

We thus computed more sophisticated models where the differential

rotation and meridional circulation profiles were modified.

First, we computed a model at 5 times the solar rotation rate

where the modified contrast

in the angular velocity was taken into account. Some uncertainties both

from an observational or a theoretical standpoint still exist

concerning the scaling between

![]() and

and ![]() but we find that the effect on the cycle

period is negligible, even when we consider the most extreme

observation of the variation of the differential rotation contrast with

rotation rate (Donahue et al. 1996).

Modifying the tachocline thickness as a function of rotation rate according to the scaling law of Brun et al. (1999)

does not help to improve the relationship between the rotation rate of

the star and the cycle period either. We show that the main impact of a

modification

of the profile of differential rotation is to decrease the percentage

of the poloidal component in the total magnetic field again because of

the increased efficiency of the

source for toroidal field: the

but we find that the effect on the cycle

period is negligible, even when we consider the most extreme

observation of the variation of the differential rotation contrast with

rotation rate (Donahue et al. 1996).

Modifying the tachocline thickness as a function of rotation rate according to the scaling law of Brun et al. (1999)

does not help to improve the relationship between the rotation rate of

the star and the cycle period either. We show that the main impact of a

modification

of the profile of differential rotation is to decrease the percentage

of the poloidal component in the total magnetic field again because of

the increased efficiency of the

source for toroidal field: the ![]() -effect.

The modification of the source term for poloidal field (decay of active

regions in Babcock-Leighton models and the kinetic

helicity of the flow in

-effect.

The modification of the source term for poloidal field (decay of active

regions in Babcock-Leighton models and the kinetic

helicity of the flow in ![]() -

-![]() models) due to an increase of the rotation rate still needs to be

addressed to study the evolution of the poloidal to toroidal field

ratio in those refined cases.

models) due to an increase of the rotation rate still needs to be

addressed to study the evolution of the poloidal to toroidal field

ratio in those refined cases.

Given the strong dependency of the magnetic cycle period on the

meridional circulation and the fact that 3-D models exhibit

multicellular patterns of the flow in latitude, it is

reasonable to think that modifying the profile of the MC according to

3-D models may help to get closer to the observational data. Indeed, we

show that adding a counter cell in latitude

which extends until about

![]() in both hemispheres reduces drastically the cycle period. We find a

quasi-linear relationship between the extension of the counter cell and

the cycle

period, which is very promising to reconcile Babcock-Leighton models

with observations of stellar activity. Another solution could be to

change the way poloidal magnetic fields are transported from the

surface down to the tachocline. In Yeates et al. (2008)

the transport is dominated by diffusion to link the distant magnetic

field generation regions. In their case the cycle period seems less

sensitive to the meridional flow amplitude and profile assumed and

depends more on the diffusion profile. Guerrero &

Gouveia Dal Pino (2008)

have introduced in Babcock-Leighton dynamo equations an extra term

representing the pumping of magnetic fields due to turbulent convection

(inspired by the work of Käpylä et al. 2006). This new process leads to vertical and

horizontal transport of the fields. Their model seems to show a significant decrease

of the cycle period dependency on the meridional flow amplitude (from

v0-0.9 to

v0-0.12, although only a shallow

meridional flow is considered, which may influence the scaling law) and

that the turbulent pumping is now responsible for regulating the cyclic

activity. Reintroducing the meridional flow amplitude scalings deduced

from 3-D calculations in this type of models would thus have much less

impact on the cycle period. The changes in the pumping coefficients

with respect to the rotation rate would have to be investigated to see

if some of the observations of stellar magnetic activity could be

recovered.

in both hemispheres reduces drastically the cycle period. We find a

quasi-linear relationship between the extension of the counter cell and

the cycle

period, which is very promising to reconcile Babcock-Leighton models

with observations of stellar activity. Another solution could be to

change the way poloidal magnetic fields are transported from the

surface down to the tachocline. In Yeates et al. (2008)

the transport is dominated by diffusion to link the distant magnetic

field generation regions. In their case the cycle period seems less

sensitive to the meridional flow amplitude and profile assumed and

depends more on the diffusion profile. Guerrero &

Gouveia Dal Pino (2008)

have introduced in Babcock-Leighton dynamo equations an extra term

representing the pumping of magnetic fields due to turbulent convection

(inspired by the work of Käpylä et al. 2006). This new process leads to vertical and

horizontal transport of the fields. Their model seems to show a significant decrease

of the cycle period dependency on the meridional flow amplitude (from

v0-0.9 to

v0-0.12, although only a shallow

meridional flow is considered, which may influence the scaling law) and

that the turbulent pumping is now responsible for regulating the cyclic

activity. Reintroducing the meridional flow amplitude scalings deduced

from 3-D calculations in this type of models would thus have much less

impact on the cycle period. The changes in the pumping coefficients

with respect to the rotation rate would have to be investigated to see

if some of the observations of stellar magnetic activity could be

recovered.

In conclusion, advection-dominated Babcock-Leighton flux-transport models may offer insights into the dynamo action occurring within the convection zones of solar-type stars. However, it is necessary to make serious modifications to these models if we wish to reconcile their predictions with observations of real stellar magnetism.

AcknowledgementsWe acknowledge funding from the European Community via the ERC-StG grant STARS2 207430 (www.stars2.eu). We are thankful to T. Emonet & P. Charbonneau for the original version of the STELEM code, to M. Browning for fruitful discussions on stellar magnetism and rotation and to the organizers of the dynamo program at KITP in Santa Barbara in 2008 where this work was initiated. We are also thankful to the anonymous referee whose comments helped improve the quality of the paper. B.P. Brown wishes to acknowledge fundings through the NASA GSRP program by award number NNG05GN08H.

References

- Babcock, H. W. 1961, ApJ, 133, 572 [Google Scholar]

- Baliunas, S. L., Donahue, R. A., Soon, W. H., et al. 1995, ApJ, 438, 269 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Baliunas, S. L., Nesme-Ribes, E., Sokoloff, D., & Soon, W. H. 1996, ApJ, 460, 848 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]