| Issue |

A&A

Volume 509, January 2010

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A28 | |

| Number of page(s) | 9 | |

| Section | Stellar atmospheres | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/200912615 | |

| Published online | 14 January 2010 | |

The Lorentz force in atmospheres of chemically peculiar stars: 56 Arietis

D. Shulyak1 - O. Kochukhov2 - G. Valyavin3 - B.-C. Lee4 - G. Galazutdinov5 - K.-M. Kim4 - I. Han4 - T. Burlakova6

1 - Institut für Astronomie, Universität Wien, Türkenschanzstraße 17, 1180 Wien, Austria

2 -

Department of Physics and Astronomy, Uppsala University, Box 515, 751 20, Uppsala, Sweden

3 -

Observatorio Astronómico Nacional SPM, Instituto de Astronomía, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Ensenada, BC, México

4 -

Korea Astronomy and Space Science Institute, 61-1, Whaam-Dong, Youseong-Gu, Taejeon, 305-348, Rep. of Korea

5 -

Department of Physics and Astronomy, Seoul National University, Gwanak-gu, Seoul 151-747, Rep. of Korea

6 -

Special Astrophysical Observatory, Russian Academy of Sciences, Nizhnii Arkhyz, Karachai Cherkess Republic, 369167, Russia

Received 2 June 2009 / Accepted 1 October 2009

Abstract

Context. The presence of electric currents in the

atmospheres of magnetic chemically peculiar (mCP) stars could

theoretically constrain the nature and evolution of magnetic field in

these stars. The Lorentz force, which is the result of the interaction

between the magnetic field and the induced currents, modifies the

atmospheric structure and induces characteristic rotational variability

of pressure-sensitive spectroscopic features, which can be analyzed

using phase-resolved spectroscopic observations.

Aims. In this work we continue presenting the results of the

magnetic pressure studies in mCP stars focusing on the high-resolution

spectroscopic observations of Bp star 56 Ari.

Methods. We interpreted observations in the framework of the

model atmosphere analyzis, which accounts for the Lorentz force

effects. We used the LLmodels stellar model atmosphere

code for the calculation of the magnetic pressure effects in the

atmosphere of 56 Ari by taking the realistic chemistry of

the star and accurate computations of the microscopic plasma properties

into account. The SYNTH3 code was employed to simulate phase-resolved variability of Balmer lines.

Results. We detected a significant variability of the H![]() ,

H

,

H![]() ,

and H

,

and H![]() spectral lines during a full rotation cycle of the star. We demonstrate

that the model with the outward-directed Lorentz force in the

dipole+quadrupole configuration is likely to reproduce the observed

hydrogen lines variation. These results present strong evidence of

non-zero global electric currents in the atmosphere of this early-type

magnetic star.

spectral lines during a full rotation cycle of the star. We demonstrate

that the model with the outward-directed Lorentz force in the

dipole+quadrupole configuration is likely to reproduce the observed

hydrogen lines variation. These results present strong evidence of

non-zero global electric currents in the atmosphere of this early-type

magnetic star.

Key words: stars: chemically peculiar - stars: magnetic field - stars: individual: 56 Ari - stars: atmospheres

1 Introduction

The atmospheres of magnetic chemically peculiar (mCP) stars display the presence of global magnetic fields ranging in strength from a few hundred G up to several tens of kG (Landstreet 2001), with the global configurations well represented by dipolar or low-order multipolar components (Bagnulo et al. 2002) that are likely stable during significant time intervals. The stability of the atmospheres against strong convective motions and the large-scale magnetic fields provide unique conditions for studing the secular evolution of global cosmic magnetic fields and other dynamical processes that may take place in the magnetized plasma. In particular, the slow variation of the field geometry and strength changes the pressure-force balance in the atmosphere via the induced Lorentz force, which makes it possible to detect it observationally and establish a number of important constraints on the plausible scenarios of the magnetic field evolution in early-type stars.Among the known characteristics of mCP stars, the variability of hydrogen Balmer lines is poorly understood. For some of stars it can be connected to the inhomogeneous surface distribution of chemical elements, possible temperature variations, and/or stellar rotation (see, for example, discussion in Lehmann et al. 2007). At the same time, some of the magnetic stars demonstrate the characteristic shape of the Balmer line variability that cannot be simply described by temperature or abundance effects. For example, Kroll (1989) showed that at least part of the variability detected in several mCP stars can be attributed to the pressure effects, indicating a non-zero Lorentz force in their atmospheres.

Different atmosphere models with the Lorenz force were considered by

several authors (see review in Valyavin et al. 2004). In this study

we follow approaches by Valyavin et al. (2004) considering the

problem in terms of induced atmospheric electric currents interacting

with magnetic fields. The authors predict that the amplitude of the variations

in hydrogen Balmer lines seen in real stars can be described if one assumes strong electric currents

flowing in upper atmospheric layers of these objects.

Later on, Shulyak et al. (2007, Paper I hereafter) extended and improved

this model to more complicated field geometries and accurate treatment of magnetized

plasma properties. Their first direct implementation of new model atmospheres to the

analyzis of the hydrogen spectra of one of the brightest mCP star ![]() Aur

shows that their rotational modulation can be induced by the Lorentz

force effect, which is not directly connected to the temperature or

abundance variation across the stellar surface.

The precise analyzis of the longitudinal magnetic field variation and

subsequent

modeling of the magnetic pressure for every observed rotational phase

of the star

allowed us to constrain the magnitude and the direction of the Lorentz

force.

In particular, the outward-directed Lorentz force (i.e. directed

outside the stellar interior

along radius) was found to provide the best fit to observations, in

combination

with rather strong induced e.m.f. (electro-magnetic force) of about

Aur

shows that their rotational modulation can be induced by the Lorentz

force effect, which is not directly connected to the temperature or

abundance variation across the stellar surface.

The precise analyzis of the longitudinal magnetic field variation and

subsequent

modeling of the magnetic pressure for every observed rotational phase

of the star

allowed us to constrain the magnitude and the direction of the Lorentz

force.

In particular, the outward-directed Lorentz force (i.e. directed

outside the stellar interior

along radius) was found to provide the best fit to observations, in

combination

with rather strong induced e.m.f. (electro-magnetic force) of about

![]() cgs units,

which was found to play an important role in the overall hydrostatic structure of the stellar atmosphere.

cgs units,

which was found to play an important role in the overall hydrostatic structure of the stellar atmosphere.

The knowledge of the direction and the strength of the Lorentz force is important for understanding of physical mechanisms that are responsible for such strong surface currents and their interaction with global, large-scale magnetic fields (see discussion in Paper I for more details). Taking this into account and following the pioneering work by Kroll (1989), we initiated a new spectroscopic search of hydrogen line variability in a number of magnetic main-sequence stars (Valyavin et al. 2005).

In this paper we present the phase-resolved high-resolution observations

of one of the weak-field (|

![]() | < 500 G) mCP star 56 Ari (HD 19832).

We detected significant variation in the Balmer line profiles and

interpreted it in terms of the non-force-free magnetic field configuration.

| < 500 G) mCP star 56 Ari (HD 19832).

We detected significant variation in the Balmer line profiles and

interpreted it in terms of the non-force-free magnetic field configuration.

The overview of observations will be presented in the next section. Then, in Sect. 3 we give a short description of the model used to simulate the effects of the magnetic pressure. The main results are summarized in Sect. 4 with conclusions and discussion given in Sects. 5 and 6 respectively.

2 Observations

Observations of 56 Ari were carried out with the BOES echelle spectrograph installed at the 1.8 m telescope of the Korean Astronomy and Space Science Institute. The spectrograph and observational procedures are described by Kim et al. (2007,2000). The instrument is a moderate-beam, fiber-fed high-resolution spectrometer that incorporates 3 STU polymicro fibers of 300, 200, and 80Seventeen spectra of the star were recorded in the course of 10 observing

nights from 2004 to 2006. Typical exposure times of a few

minutes allowed

![]() -300 to be achieved.

Table 1 gives an overview of our observations.

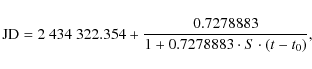

Throughout this study we implement the ephemeris derived by Adelman et al. (2001)

using linear changing period model:

-300 to be achieved.

Table 1 gives an overview of our observations.

Throughout this study we implement the ephemeris derived by Adelman et al. (2001)

using linear changing period model:

|

(1) |

where

Table 1: Observations of 56 Ari.

3 Model

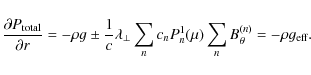

3.1 General equations and approximations

In this section we follow the approach and methods outlined previously in Paper I. However, for the sake of explanation, we find it useful to state here some of the general assumptions used in the modeling procedure:

- 1.

- the stellar surface magnetic field is axisymmetric and is dominated by dipolar or dipole+quadrupolar component in all atmospheric layers;

- 2.

- the induced e.m.f. has only an azimuthal component, similar to that

described by Wrubel (1952), who considered decay of the global stellar

magnetic field. In this case the distribution of the surface

electric currents can be expressed by the Legendre polynomials

,

where n = 1 for dipole,

n = 2 for quadrupole, etc., and

,

where n = 1 for dipole,

n = 2 for quadrupole, etc., and

is the cosine of the co-latitude

angle

is the cosine of the co-latitude

angle  which is counted in the coordinate system connected

to the symmetry axis of the magnetic field;

which is counted in the coordinate system connected

to the symmetry axis of the magnetic field;

- 3.

- the atmospheric layers are assumed to be in static equilibrium and no horizontal motions are present;

- 4.

- stellar rotation, Hall's currents, ambipolar diffusion and other dynamical processes are neglected.

Obtaining this equation we used the superposition principle for field vectors and the solution of Maxwell equations for each of the multipolar components following Wrubel (1952). We also suppose that

We note that the values of cn are free parameters to be found by using our model. These values represent the fundamental characteristics that can be used for building self-consistent models of the global stellar magnetic field geometry and its evolution. Thus, an indirect measurement of these parameters via the study of the Lorentz force is of fundamental importance for understanding the stellar magnetism.

Calculation of the electric conductivity

![]() is

carried out using the Lorentz collision model where

only binary collisions between particles are allowed which is a good

approximation for a low density stellar atmosphere plasma.

The detailed description and basic relationships of this approach are given in

Paper I.

is

carried out using the Lorentz collision model where

only binary collisions between particles are allowed which is a good

approximation for a low density stellar atmosphere plasma.

The detailed description and basic relationships of this approach are given in

Paper I.

From Eq. (2) it is seen that, in the presence of electric currents

and magnetic field, the rotation of a star can produce phase-dependent Lorentz-force term

(due to a variation of

![]() and

and

![]() ), which will in turn modify the hydrostatic structure

of the atmosphere, manifesting itself as a variation of pressure-sensitive spectral lines.

), which will in turn modify the hydrostatic structure

of the atmosphere, manifesting itself as a variation of pressure-sensitive spectral lines.

3.2 Model atmospheres with Lorentz force

Our calculations were carried out with the stellar model atmosphere code LLmodels developed by Shulyak et al. (2004). At each iteration the code calculates electric conductivity in all atmospheric layers using all available charged and neutral plasma particles. The conductivity is then used to evaluate the magnetic contribution to the magnetic gravity and to execute temperature and mass correction procedure.

The input parameters for the calculation of magnetic pressure are the direction of the Lorentz force

(inward- or outward-directed), e.m.f. at the stellar equator, mean surface magnetic field modulus

![]() ,

and the product of the two sums in Eq. (2) containing contribution

from all considered multipolar components for every single rotational phase of the star.

,

and the product of the two sums in Eq. (2) containing contribution

from all considered multipolar components for every single rotational phase of the star.

As can be seen from Eq. (2), there is some critical value of cnthat may produce unstable solution in the case of the outward-directed Lorentz force. Such models cannot be considered in the hydrostatic equilibrium approximation introduced above and were deemed non-physical in our calculations. Thus, for each set of models, we restricted cn values to ensure static equilibrium.

The atomic line list was extracted from the VALD database (Piskunov et al. 1995; Kupka et al. 1999), including all lines originating from the predicted and observed energy levels. This line list was used as input for the lines opacity calculation in the LLmodels code.

4 Numerical results

4.1 Model atmosphere parameters of 56 Ari

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=90,width=18cm]{figures/12615f1.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/01/aa12615-09/Timg37.png)

|

Figure 1:

Comparison of the observed and computed spectral energy distributions of 56 Ari.

Theoretical models correspond to

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

The model atmosphere parameters, ![]() and

and

![]() ,

were determined using

theoretical fit of the hydrogen Balmer lines and spectral energy distribution.

It was constructed by combining the average of the optical spectrophotometric

scans obtained by Adelman (1983) and low dispersion UV spectrograms from

the IUE INES

,

were determined using

theoretical fit of the hydrogen Balmer lines and spectral energy distribution.

It was constructed by combining the average of the optical spectrophotometric

scans obtained by Adelman (1983) and low dispersion UV spectrograms from

the IUE INES![]() database.

For modeling the hydrogen H

database.

For modeling the hydrogen H![]() and H

and H![]() line profiles we used

the mean spectrum of 56 Ari averaged other all 17 observed

rotational phases. The projected rotational velocity

line profiles we used

the mean spectrum of 56 Ari averaged other all 17 observed

rotational phases. The projected rotational velocity ![]() = 160 km s-1

was taken from Hatzes (1993). Ryabchikova (2003)

used the same value in a more recent Doppler imaging study. Individual

abundances of several chemical elements, listed in Table 2, were determined as described below (Sect. 4.3).

= 160 km s-1

was taken from Hatzes (1993). Ryabchikova (2003)

used the same value in a more recent Doppler imaging study. Individual

abundances of several chemical elements, listed in Table 2, were determined as described below (Sect. 4.3).

Table 2:

Abundances (in

![]() )

of 56 Ari, used for determining model atmosphere

parameters.

)

of 56 Ari, used for determining model atmosphere

parameters.

Synthetic Balmer line profiles were calculated using the SYNTH3 program (Kochukhov 2007),

which incorporates recent improvements in the treatment of the hydrogen

line opacity (Barklem et al. 2000).

The stellar energy distribution and Balmer lines are approximated best

with the following parameters:

![]() K,

K,

![]() .

Note that such high accuracy of the determined

parameters is just an internal accuracy obtained from our technique, which

we used to fit the data. Real parameters

may be slightly different from the obtained ones due to various systematic error sources,

but this does not play a significant role in our study.

.

Note that such high accuracy of the determined

parameters is just an internal accuracy obtained from our technique, which

we used to fit the data. Real parameters

may be slightly different from the obtained ones due to various systematic error sources,

but this does not play a significant role in our study.

Comparisons of the observations and model predictions are presented

in Figs. 1 and 2.

We transformed Adelman's spectrophotometric observations to the absolute units

following Lipski & Stepien (2008). Since the absolute calibration of IUE fluxes around their red end

have substantial uncertainties

(see Lipski & Stepien 2008),

we scaled the IUE fluxes by ![]() 10%

to match the Adelman's data in the near-UV region. This correction is

comparable to the offset between alternative flux calibrations

suggested for the IUE data (García-Gil et al. 2005). Applying the correction ensured that the IUE spectra are smooth continuation of the optical

spectrophotometry. Then the theoretical fluxes can be adjusted to fit

the combined set of observations.

Lipski & Stepien (2008) also noted the discrepancy between

observations in visual and UV, but did not do any attempts to correct it. This is why their

final effective temperature of 56 Ari was found to be

10%

to match the Adelman's data in the near-UV region. This correction is

comparable to the offset between alternative flux calibrations

suggested for the IUE data (García-Gil et al. 2005). Applying the correction ensured that the IUE spectra are smooth continuation of the optical

spectrophotometry. Then the theoretical fluxes can be adjusted to fit

the combined set of observations.

Lipski & Stepien (2008) also noted the discrepancy between

observations in visual and UV, but did not do any attempts to correct it. This is why their

final effective temperature of 56 Ari was found to be

![]() K resulting from the

fact that ignoring the obviously spurious offset between the observed datasets one needs a

lower

K resulting from the

fact that ignoring the obviously spurious offset between the observed datasets one needs a

lower

![]() to fit the IUE fluxes simultaneously with Adelman's fluxes redward

of the Balmer jump.

As an example we also show in Fig. 1 theoretical flux obtained

from the

to fit the IUE fluxes simultaneously with Adelman's fluxes redward

of the Balmer jump.

As an example we also show in Fig. 1 theoretical flux obtained

from the

![]() K,

K,

![]() model which

fits reasonably well the hydrogen Balmer lines (see Fig. 2),

but fails to reproduce either Adelman's or IUE data.

model which

fits reasonably well the hydrogen Balmer lines (see Fig. 2),

but fails to reproduce either Adelman's or IUE data.

Photometric observations in the Strömgren and UBV systems also point to the higher

![]() and

and ![]() of 56 Ari.

For instance, comparing theoretically computed color-indices with observations of Hauck & Mermilliod (1998) and

Nicolet (1978) we find that observed photometric parameters (

b-y=-0.052,

of 56 Ari.

For instance, comparing theoretically computed color-indices with observations of Hauck & Mermilliod (1998) and

Nicolet (1978) we find that observed photometric parameters (

b-y=-0.052,

![]() ,

B-V=-0.12, U-B=-0.42) are best fitted with

,

B-V=-0.12, U-B=-0.42) are best fitted with

![]() K,

K,

![]() model

(

b-y=-0.052,

model

(

b-y=-0.052,

![]() ,

B-V=-0.12, U-B=-0.43) rather than more cooler

,

B-V=-0.12, U-B=-0.43) rather than more cooler

![]() K,

K,

![]() model (

b-y=-0.048,

model (

b-y=-0.048,

![]() ,

B-V=-0.12, U-B=-0.38).

,

B-V=-0.12, U-B=-0.38).

Finally, recent studies by Kochukhov et al. (2005) and Khan & Shulyak (2006) showed that the effects of Zeeman splitting and polarized radiative transfer on the model atmosphere structure and shapes of hydrogen line profiles are less than 0.1% for magnetic field intensities around 1 kG, so they can be safely neglected in the present investigation.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{figures/12615f2.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/01/aa12615-09/Timg49.png)

|

Figure 2:

Comparison of the observed and computed H |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{figures/12615f3.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/01/aa12615-09/Timg50.png)

|

Figure 3:

Comparison of the longitudinal field observations of 56 Ari (symbols)

and the model curves for

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

4.2 Magnetic-field geometry

To calculate the Lorentz force effects, it is essential to specify the

magnetic-field geometry (see Eq. (2)). For this purpose we

made use of the longitudinal magnetic field measurements obtained by

Borra & Landstreet (1980) using H![]() photopolarimetric technique.

The authors observed a smooth single-wave

photopolarimetric technique.

The authors observed a smooth single-wave

![]() variation with rotation phase

and concluded that it is probably caused by a dipole inclined to the

rotation axis of the star.

variation with rotation phase

and concluded that it is probably caused by a dipole inclined to the

rotation axis of the star.

Generalizing this work, we have approximated the magnetic-field topology of

56 Ari by a combination of the dipole and axisymmetric quadrupole magnetic

components. We also assumed that the symmetry axes of the dipole and

quadrupole magnetic fields are parallel. Thus, the magnetic model parameters

include the polar strength of the dipolar component

![]() ,

relative contribution of the quadrupole field

,

relative contribution of the quadrupole field

![]() ,

magnetic obliquity

,

magnetic obliquity ![]() ,

and inclination angle i of the stellar rotation axis with respect to

the line of sight.

The last parameter can be estimated from the usual oblique rotator relation

connecting stellar radius, rotation period, and

,

and inclination angle i of the stellar rotation axis with respect to

the line of sight.

The last parameter can be estimated from the usual oblique rotator relation

connecting stellar radius, rotation period, and ![]() .

Employing the recently revised Hipparcos parallax of 56 Ari,

.

Employing the recently revised Hipparcos parallax of 56 Ari,

![]() mas

(van Leeuwen 2007),

mas

(van Leeuwen 2007),

![]() = 12 800 K and bolometric correction BC=-0.74determined by Lipski & Stepien (2008), we found a stellar radius

= 12 800 K and bolometric correction BC=-0.74determined by Lipski & Stepien (2008), we found a stellar radius

![]()

![]() and inclination angle

and inclination angle

![]() .

However, the previous Doppler imaging studies of

Hatzes (1993) and Ryabchikova (2003) favored the value of

.

However, the previous Doppler imaging studies of

Hatzes (1993) and Ryabchikova (2003) favored the value of

![]() .

Consequently we decided to explore the model parameters for the entire range

of i=50-70

.

Consequently we decided to explore the model parameters for the entire range

of i=50-70![]() .

.

The remaining free parameters of the magnetic field model

were determined with the least-square fit of the observed

![]() variation

(Borra & Landstreet 1980).

Compared to

variation

(Borra & Landstreet 1980).

Compared to ![]() Aur

investigated in Paper I, the longitudinal magnetic field curve of

56 Ari is poorly defined due to large observational errors and a

relatively small number of measurements.

In this situation the acceptable solutions for the magnetic field

geometry

fall in a rather wide range: from

Aur

investigated in Paper I, the longitudinal magnetic field curve of

56 Ari is poorly defined due to large observational errors and a

relatively small number of measurements.

In this situation the acceptable solutions for the magnetic field

geometry

fall in a rather wide range: from

![]() to

to

![]() for

for

![]() ,

to

,

to

![]() for

for

![]() ,

and to

,

and to

![]() for

for

![]() (Fig. 3). The corresponding dipolar field strength range is

(Fig. 3). The corresponding dipolar field strength range is

![]() -1.8 kG and magnetic obliquity is

-1.8 kG and magnetic obliquity is ![]() -90

-90![]() .

The lowest

.

The lowest

![]() was found between

was found between

![]() with the average value

with the average value

![]() while

while

![]() for other geometries: with such a small difference

we conclude that all the considered magnetic field geometries are

equally possible.

for other geometries: with such a small difference

we conclude that all the considered magnetic field geometries are

equally possible.

4.3 Effects of horizontal abundance distribution

We used spectrum synthesis calculations to access chemical properties of the atmosphere of 56 Ari. Abundances of He, Al, Mg, Si, and Fe were determined by fitting SYNTH3 spectra to the average observations of the star. Results of this analyzis, summarized in Table 2, indicate that He, Al and Mg are deficient in the atmosphere of 56 Ari with respect to the solar chemical composition. Fe is moderately overabundant while Si is strongly enhanced. Abundance of Cr cannot be determined reliably, but since no prominent Cr II lines are present in the spectrum of 56 Ari, we concluded that its overabundance is most likely smaller than that of Fe.

In addition to the mean abundances analyzis we interpreted variation in the phase-resolved spectra using the Doppler imaging (DI) technique (Kochukhov et al. 2004). Details of this work will be presented in a separate publication. here we are only concerned with the possible effect of the horizontal abundance variations on the hydrogen line profiles. Effects of the possible vertical stratitification of chemical elemets are ignored because, for the purpose of our study, they will not differ much from the effects of horizontal abundance inhomogeneities. By deriving surface-resolved abundances, we effectively account for the line opacity variation that would be introduced by chemical stratification.

Among the elements mentioned above, only Mg and Si show strong line profile variations. Therefore, we reconstructed abundance maps of Si using the red doublets Si II 6347, 6371 Å, and Mg using the 4481 Å line. The modeling of the last region also included the He I 4471 Å line, which allowed us to estimate potential influence of the He abundance variation on the model atmosphere structure and hydrogen line profile behavior.

Analyzis of Si, He, and Mg demonstrated that horizontal abundance

inhomogeneities give a negligible contribution to the hydrogen line profile variation.

We computed model atmospheres with the surface-averaged abundances for each rotational phase of the star.

Figure 4 shows that the resulting standard deviation of the synthetic profiles is minute compared

to the variation observed in the line wings of H![]() ,

H

,

H![]() ,

and H

,

and H![]() .

.

Much larger abundance gradients of the iron peak elements are required to induce a noticeable modulation of the hydrogen line profiles during rotation cycle. Figure 4 shows results of the numerical experiment where we assumed that Fe has the same horizontal distribution as Si but with 10 times higher contrast. This calculation contradicts the actual observations, since the Fe lines in 56 Ari vary weakly and differently from Si, but it represents a useful illustration of the impact of chemical inhomogeneities. One can see that the metal abundance spots lead to the variation in the depth of hydrogen line cores, while in 56 Ari we see changes in the line wings. Thus, following Paper I and Kroll (1989), we are led to conclude that the chemical spots cannot contribute to the observed Balmer line wing variations.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[height=9cm,angle=90]{figures/12615f4.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/01/aa12615-09/Timg69.png)

|

Figure 4:

The standard deviation |

| Open with DEXTER | |

4.4 The Lorentz force

To predict the

phase-resolved variability in hydrogen line profiles, both the

inward- and outward-directed Lorentz forces

are examined through the model atmosphere calculations.

The actual magnetic input parameters of

computations with the LLmodels code include the sign of the Lorentz force,

magnetic field modulus B, and

the product of two sums

![]() (see Eq. (2)).

We take the last two parameters to be disk-averaged at the individual

rotation phases

incorporating them in 1D stellar atmosphere code. The corresponding

phase curves of the magnetic parameters relevant to our calculations

are illustrated in Fig. 6.

(see Eq. (2)).

We take the last two parameters to be disk-averaged at the individual

rotation phases

incorporating them in 1D stellar atmosphere code. The corresponding

phase curves of the magnetic parameters relevant to our calculations

are illustrated in Fig. 6.

By taking the wide variety of possible solutions for the surface magnetic-field

geometry into account (see Sect. 4.2), we calculated several model grids

with the outward- and inward-directed Lorentz force

and

![]() ranging from 0.5 to -4.5 with a step of 0.5.

The calculations show that, in order to reproduce the amplitudes of the observed standard

deviations due to the profile variations, the effective electric field should be in the range

ranging from 0.5 to -4.5 with a step of 0.5.

The calculations show that, in order to reproduce the amplitudes of the observed standard

deviations due to the profile variations, the effective electric field should be in the range

![]() cgs in the case of the inward-directed Lorentz force

and

cgs in the case of the inward-directed Lorentz force

and

![]() cgs in the case of the outward-directed Lorentz force.

Under the assumption of a purely dipolar configuration, these values are:

cgs in the case of the outward-directed Lorentz force.

Under the assumption of a purely dipolar configuration, these values are:

![]() cgs

for inward-directed and

cgs

for inward-directed and

![]() cgs for outward-directed Lorentz forces.

cgs for outward-directed Lorentz forces.

![\begin{figure}

\par\mbox{\includegraphics[width=6cm]{figures/12615f5a.ps}\includ...

...5e.ps}\includegraphics[height=6cm,angle=90]{figures/12615f5f.ps} }\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/01/aa12615-09/Timg75.png)

|

Figure 5:

The effective acceleration as a function of the Rosseland

optical depth for different rotation phases calculated for several magnetic field configurations and induced

e.m.f. The resulting standard deviations around H |

| Open with DEXTER | |

It was not possible to fit the amplitude

of the observed standard deviation with the inward-directed Lorentz force

for all models considered in our study.

This is true for models with

![]() ,

where the changes

in longitudinal magnetic field and magnetic field modulus result in very

narrow phase-resolved variations in the magnetic force term. As an example,

the left panel of Fig. 5 illustrates the run of the

,

where the changes

in longitudinal magnetic field and magnetic field modulus result in very

narrow phase-resolved variations in the magnetic force term. As an example,

the left panel of Fig. 5 illustrates the run of the

![]() with the Rosseland optical depth in the atmosphere of 56 Ari (

with the Rosseland optical depth in the atmosphere of 56 Ari (

![]() )

for inward- and outward directed Lorentz forces computed under different

assumptions about the induced electric field. An increase in the e.m.f. value by a factor of two

considerably changes the amplitude of the effective gravity, but the computed

standard deviation does not change much (see lower left panel of Fig. 5).

This is why even a large increase of e.m.f. does not show up itself in

a standard deviation plot. Obviously, the situation may change once a more complex

geometry of the magnetic field is introduced; however, it is connected with the

introduction of additional free parameters making the fitting procedure

ambiguous.

In contrast, the outward-directed magnetic force seems to have a greater impact

on the model pressure structure: varying e.m.f. value from

)

for inward- and outward directed Lorentz forces computed under different

assumptions about the induced electric field. An increase in the e.m.f. value by a factor of two

considerably changes the amplitude of the effective gravity, but the computed

standard deviation does not change much (see lower left panel of Fig. 5).

This is why even a large increase of e.m.f. does not show up itself in

a standard deviation plot. Obviously, the situation may change once a more complex

geometry of the magnetic field is introduced; however, it is connected with the

introduction of additional free parameters making the fitting procedure

ambiguous.

In contrast, the outward-directed magnetic force seems to have a greater impact

on the model pressure structure: varying e.m.f. value from

![]() cgs to

cgs to

![]() cgs changes the amplitude of standard deviation by about

a factor of two or more.

cgs changes the amplitude of standard deviation by about

a factor of two or more.

The amplitude of the standard deviation around hydrogen lines strongly

depends on the magnitude of the inward-directed Lorentz force for

different magnetic field geometries.

For instance, the middle panel of Fig. 5 illustrates standard deviations

for the model with

![]() :

changing induced e.m.f. by a factor of two

considerably increases the amplitude of the standard deviation.

Similarly, the right panel of Fig. 5 shows the predicted variations

for the purely dipolar model.

:

changing induced e.m.f. by a factor of two

considerably increases the amplitude of the standard deviation.

Similarly, the right panel of Fig. 5 shows the predicted variations

for the purely dipolar model.

4.5 Comparison with the observations

In the following we compare the residual theoretical and observed

Balmer lines with model predictions based on different assumptions about

the magnetic field geometry and the direction of the Lorentz force.

The residuals are obtained by subtracting a spectrum at a reference phase

(

![]() where the Balmer profiles have the largest widths)

from all the other spectra. Figure 7 illustrates residual

H

where the Balmer profiles have the largest widths)

from all the other spectra. Figure 7 illustrates residual

H![]() ,

H

,

H![]() ,

and H

,

and H![]() line profiles

for each of the observed rotation phases. The positive sign of the residuals implies

that the lines at the current phase are narrower

than those obtained at the reference phase.

It is seen that the characteristic behavior of hydrogen lines demonstrates

a single wave variation with the most noticeable effect at phases

between

line profiles

for each of the observed rotation phases. The positive sign of the residuals implies

that the lines at the current phase are narrower

than those obtained at the reference phase.

It is seen that the characteristic behavior of hydrogen lines demonstrates

a single wave variation with the most noticeable effect at phases

between

![]() and

and

![]() .

The effect is also seen in the red

wings of lines at

.

The effect is also seen in the red

wings of lines at

![]() ;

however, it is smeared out in the blue wing.

We emphasize that this systematic asymmetry, with the blue wing lying below the red one,

is observed for all three studied Balmer lines. The inaccuracy in the spectrum processing

can be one of the reasons for this effect.

However, our data reduction is identical to the analyzis of

;

however, it is smeared out in the blue wing.

We emphasize that this systematic asymmetry, with the blue wing lying below the red one,

is observed for all three studied Balmer lines. The inaccuracy in the spectrum processing

can be one of the reasons for this effect.

However, our data reduction is identical to the analyzis of ![]() Aur (see Shulyak et al. 2007),

which shows no such asymmetry. Thus, we suspect that the asymmetry may also have a physical origin

because of the non-stationary, magnetically-channeled stellar wind from the surface of 56 Ari.

Very fast rotation and a relatively high temperature of this star make it plausible that its

wind produces the variable, obscured P-Cyg feature distorting blue wings of the Balmer lines.

The presence of a weak feature approximately 2.5 Å blueward of the line center seen for

all three hydrogen lines could also be an argument for the wind. (For H

Aur (see Shulyak et al. 2007),

which shows no such asymmetry. Thus, we suspect that the asymmetry may also have a physical origin

because of the non-stationary, magnetically-channeled stellar wind from the surface of 56 Ari.

Very fast rotation and a relatively high temperature of this star make it plausible that its

wind produces the variable, obscured P-Cyg feature distorting blue wings of the Balmer lines.

The presence of a weak feature approximately 2.5 Å blueward of the line center seen for

all three hydrogen lines could also be an argument for the wind. (For H![]() line the presence of

this feature could alternatively be explained by absorption in Ti II and Fe II lines; however, in the case

of H

line the presence of

this feature could alternatively be explained by absorption in Ti II and Fe II lines; however, in the case

of H![]() ,

there are no spectral lines that could contribute to this feature.)

Despite these problems introduced by an unknown physical process, the characteristic shape

of the Lorentz force induced variability is clearly seen in the hydrogen lines of 56 Ari, making it possible

to perform the analyzis in the framework of our modeling approach.

,

there are no spectral lines that could contribute to this feature.)

Despite these problems introduced by an unknown physical process, the characteristic shape

of the Lorentz force induced variability is clearly seen in the hydrogen lines of 56 Ari, making it possible

to perform the analyzis in the framework of our modeling approach.

![\begin{figure}

\par\mbox{\includegraphics[width=4cm]{figures/12615f6a.ps}\hspace...

...}\hspace{2.5mm}

\includegraphics[width=4cm]{figures/12615f6d.ps} }\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/01/aa12615-09/Timg84.png)

|

Figure 6: Magnetic field modulus and Lorentz force parameter as a function of rotation phase for several magnetic field models. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

None of the tested theoretical models appeared to fit the observed variability

in all phases, but for more than half of them models still generally describe the data more or less reasonably well

(see, for example, Models 1 or 4).

Varying the magnetic field geometry and the ratio of induced

dipolar and quadrupolar equatorial e.m.f.'s (c2/c1), we could achieve

good agreement only for a certain phase interval: either it was possible to fit the

observations around phase ![]() or only for other phases.

As an example, in Fig. 7 we plot some of the theoretical

predictions for models that provide a more or less reasonable fit to the

observations. In particular, models with the outward-directed Lorentz force

are shown for the following configurations:

or only for other phases.

As an example, in Fig. 7 we plot some of the theoretical

predictions for models that provide a more or less reasonable fit to the

observations. In particular, models with the outward-directed Lorentz force

are shown for the following configurations:

|

|

|

|

|

|

For all plotted models, the inclination angle

![]() was assumed. Taking

was assumed. Taking

![]() does not change the disk-integrated

parameters of the magnetic field much and thus leads to essentially the same

picture of the hydrogen lines variation (see below).

does not change the disk-integrated

parameters of the magnetic field much and thus leads to essentially the same

picture of the hydrogen lines variation (see below).

Models 1 and 2 have the same parameters except for the strength of quadrupolar

magnetic field component. They produce almost the same fit to the

observed variations, and in the same manner, are not able to fit phases at

![]() and above (Although Model 2 systematically gives a little bit

better fit there). Models with

and above (Although Model 2 systematically gives a little bit

better fit there). Models with

![]() give

the same kind of the fit, but we do not plot them here to avoid overcrowding the plot.

At the same time, Model 3 seems to be a preferable one

for these phases, but it fails to fit observations at phases

give

the same kind of the fit, but we do not plot them here to avoid overcrowding the plot.

At the same time, Model 3 seems to be a preferable one

for these phases, but it fails to fit observations at phases

![]() ,

and gives an enormously strong effect at phases

,

and gives an enormously strong effect at phases

![]() and down to zero. This is also true for Model 4 with the

inward-directed Lorentz force. This model fits such phases as

and down to zero. This is also true for Model 4 with the

inward-directed Lorentz force. This model fits such phases as

![]() reasonably well,

but yields the line wings that are

generally too wide for comparing with observed ones. Thus, of the two

possible directions of the Lorentz force in our

model, we consider an outward-directed Lorentz force as the more reasonable choice

to describe observations of 56 Ari. Because of problems with telluric lines, the

continuum normalization around H

reasonably well,

but yields the line wings that are

generally too wide for comparing with observed ones. Thus, of the two

possible directions of the Lorentz force in our

model, we consider an outward-directed Lorentz force as the more reasonable choice

to describe observations of 56 Ari. Because of problems with telluric lines, the

continuum normalization around H![]() line is substantially inaccurate

comparing to other lines

and it is not possible to distinguish between different models there.

line is substantially inaccurate

comparing to other lines

and it is not possible to distinguish between different models there.

![\begin{figure}

\par\mbox{\includegraphics[width=6cm]{figures/12615f7a.ps}\includ...

...res/12615f7b.ps}\includegraphics[width=6cm]{figures/12615f7c.ps} }\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/01/aa12615-09/Timg94.png)

|

Figure 7:

Residual profiles of the H |

| Open with DEXTER | |

By testing models with different magnetic field parameters, we tried to find

those that predict a single-wave variation of the magnetic force term over the

rotation cycle, as indicated by observations. Moreover, its run is likely to have a wide plateau around

![]() and drop rapidly close to

and drop rapidly close to ![]() and

and ![]() to fit observations

(see Fig. 7). By varying the parameters

to fit observations

(see Fig. 7). By varying the parameters

![]() and

c2/c1 (with the fixed i and

and

c2/c1 (with the fixed i and ![]() ), we succeeded in finding

sets of parameters that give this kind of plateau, but in all cases it appears to be not

as wide as needed to fit observations in all phases. This is illustrated in

Fig. 6 where we plot the magnetic parameters used for the Lorentz force

calculation in some of the models mentioned above as a function of the rotation phase.

The right panel in this figure illustrates predictions for the purely dipolar model.

It is also seen that the inclination angle i does

not play a critical role in the present investigation: models with different i would give the same phase-resolved variation in hydrogen lines, and any

amplitude difference between them can be adjusted by a proper choice of a c1 parameter.

), we succeeded in finding

sets of parameters that give this kind of plateau, but in all cases it appears to be not

as wide as needed to fit observations in all phases. This is illustrated in

Fig. 6 where we plot the magnetic parameters used for the Lorentz force

calculation in some of the models mentioned above as a function of the rotation phase.

The right panel in this figure illustrates predictions for the purely dipolar model.

It is also seen that the inclination angle i does

not play a critical role in the present investigation: models with different i would give the same phase-resolved variation in hydrogen lines, and any

amplitude difference between them can be adjusted by a proper choice of a c1 parameter.

In this investigation we focused analyzis on the hydrogen lines. It

appears that they are most sensitive to the pressure changes introduced

by the Lorentz force. As for metal lines, none of the strong Si II lines visible in the spectrum of 56 Ari,

![]() Å,

5466.48 Å,

5466.89 Å, 6347.11 Å or 6371.37 Å, exhibits

significant variation due to a non-zero Lorentz force. We have tested

this by using the magnetic parameters of Model 1 (which has the

largest amplitude of the

Å,

5466.48 Å,

5466.89 Å, 6347.11 Å or 6371.37 Å, exhibits

significant variation due to a non-zero Lorentz force. We have tested

this by using the magnetic parameters of Model 1 (which has the

largest amplitude of the

![]() variation, see Fig. 5)

and

recomputing spectrum models for every phase with the mean abundances.

We find no detectable changes in the line wings and less than a 1%

difference in the line cores between models with and without

Lorentz force. This difference is likely to stem from the differences

in the

temperature distribution of these two models. No visible

phase-dependent changes can be seen in the spectra corresponding to the

models with Lorentz force. These results led us to the conclusion that,

because of their high pressure sensitivity

in the predominantly ionized plasma of the atmosphere of such a

relatively hot star, only the hydrogen lines are useful indicators for

the magnetic pressure effects.

variation, see Fig. 5)

and

recomputing spectrum models for every phase with the mean abundances.

We find no detectable changes in the line wings and less than a 1%

difference in the line cores between models with and without

Lorentz force. This difference is likely to stem from the differences

in the

temperature distribution of these two models. No visible

phase-dependent changes can be seen in the spectra corresponding to the

models with Lorentz force. These results led us to the conclusion that,

because of their high pressure sensitivity

in the predominantly ionized plasma of the atmosphere of such a

relatively hot star, only the hydrogen lines are useful indicators for

the magnetic pressure effects.

Similarly, we find no evidence of any phase-dependent pressure

effects on the stellar spectral energy distribution. The maximum

difference between models with and without the Lorentz

force is less than 2% in Balmer continuum. This corresponds to a ![]() 0.01 mag difference in

0.01 mag difference in ![]() color-index and even less for

other Strömgren parameters. Thus, variation seen, for example, in the

phase-resolved spectrophotometric scans of 56 Ari published by Adelman (1983) could not be attributed to the Lorentz force effects, but are produced by inhomogeneous abundances and/or other mechanisms.

color-index and even less for

other Strömgren parameters. Thus, variation seen, for example, in the

phase-resolved spectrophotometric scans of 56 Ari published by Adelman (1983) could not be attributed to the Lorentz force effects, but are produced by inhomogeneous abundances and/or other mechanisms.

We note that the strong decrease in

![]() evident in Fig. 5 (up to

evident in Fig. 5 (up to ![]() 1 dex around

1 dex around

![]() ),

compared to the non-magnetic case, leads to a relatively small difference in the observed parameters because of

a) the fact that this decrease does not affect the entire stellar atmosphere and

b) non-local nature of the hydrostatic equation in the presence of depth-dependent

),

compared to the non-magnetic case, leads to a relatively small difference in the observed parameters because of

a) the fact that this decrease does not affect the entire stellar atmosphere and

b) non-local nature of the hydrostatic equation in the presence of depth-dependent

![]() .

The latter implies that, for example, one order of magnitude

increase in the magnetic gravity only results in three times lower gas pressure for the outward-directed Lorentz force,

which is too small to significantly change

the opacity coefficient and influence the model structure. The difference between magnetic models

for different rotational phases is even less since

.

The latter implies that, for example, one order of magnitude

increase in the magnetic gravity only results in three times lower gas pressure for the outward-directed Lorentz force,

which is too small to significantly change

the opacity coefficient and influence the model structure. The difference between magnetic models

for different rotational phases is even less since

![]() varies maximum by a factor of

varies maximum by a factor of ![]() 2 for Model 1.

2 for Model 1.

Finally, we stress that it is difficult to conclude anything with certainty regarding the preferable model of the magnetic field geometry without additional accurate magnetic observations of 56 Ari. Furthermore, other dynamic processes, such as Hall's currents and particle diffusion, may contribute to the observed variations in hydrogen lines. These processes cannot be accounted for in our modeling because of their complex nature. Nevertheless, similar to the results of the Paper I, in this study we demonstrate that the observations can be described with a simple geometrical approach under the assumption of strong surface electric currents in the atmosphere of a main-sequence mCP star.

5 Conclusions

With the use of the high-resolution, phase-resolved observations of a magnetic CP star 56 Ari and employing modern model atmosphere technique, we detected and investigated variations in the Stark-broadened profiles of H- The characteristic shape of the variation during a full rotation cycle of the star corresponds to those described by Kroll (1989) and other authors as a result of the impact of a substantial Lorentz force (see Paper I and references therein).

- Numerical calculations of the model atmospheres with individual abundances demonstrate that the surface chemical spots cannot produce the observed variability in the hydrogen line profiles of the star.

- Our model shows reasonable agreement with the observations if the outward-directed magnetic force is applied assuming the dipole+quadrupole magnetic field configuration. Unfortunately, large uncertainties in the available observations of the longitudinal magnetic field made it impossible to conclude anything confidently about the strengths of the quadrupolar component.

-

Taking a variety of possible solutions into account, we find that, to fit the amplitude

of a phase-resolved variation in H

,

H

,

H ,

and H

,

and H lines, the magnitude

of an induced equatorial e.m.f. must be in the range

10-11-10-10 cgs in case of an

outward-directed Lorentz force and

lines, the magnitude

of an induced equatorial e.m.f. must be in the range

10-11-10-10 cgs in case of an

outward-directed Lorentz force and

in case of an inward-directed

one.

in case of an inward-directed

one.

6 Discussion

56 Ari is the second magnetic CP star for which we detected the characteristic variation in the hydrogen Balmer line profiles and performed detailed modeling of the Lorentz force effect. Our previous target, A0p starA single-wave variation of the residual spectra is a characteristic signature

for both ![]() Aur

and 56 Ari. Since both stars have high inclination angles and

magnetic obliquities, in the framework of our Lorentz force model this

variation indicates the presence of a more complex magnetic field

geometry

than a simple dipole. Such a variation can be obtained in the

non-dipolar theoretical models by a

proper choice of induced e.m.f. for each of the multipolar components (e.g. the c2/c1 ratio in the case

of dipole+quadrupole combination).

Furthermore, for both stars the amplitude of the longitudinal magnetic field

variation is about

Aur

and 56 Ari. Since both stars have high inclination angles and

magnetic obliquities, in the framework of our Lorentz force model this

variation indicates the presence of a more complex magnetic field

geometry

than a simple dipole. Such a variation can be obtained in the

non-dipolar theoretical models by a

proper choice of induced e.m.f. for each of the multipolar components (e.g. the c2/c1 ratio in the case

of dipole+quadrupole combination).

Furthermore, for both stars the amplitude of the longitudinal magnetic field

variation is about ![]() 500 G,

which can be the reason for the similar

amplitude of the detected Balmer lines variation (

500 G,

which can be the reason for the similar

amplitude of the detected Balmer lines variation (![]() 1%) since the effective

temperatures of stars are different (

1%) since the effective

temperatures of stars are different (

![]() (

(![]() Aur) =10 400 K,

Aur) =10 400 K,

![]() (56 Ari) = 12 800 K).

Similar to Paper I, we do not consider any details here of the physical

mechanisms that could be responsible for the observed Lorentz force. The final conclusion

about the nature of the significant magnetic pressure can only be obtained when more

sophisticated models of the magnetic field evolution and its interaction with highly

magnetized atmospheric structure have become available and/or alternative models

been tested (however, for some of the estimates see discussion in Shulyak et al. 2007).

(56 Ari) = 12 800 K).

Similar to Paper I, we do not consider any details here of the physical

mechanisms that could be responsible for the observed Lorentz force. The final conclusion

about the nature of the significant magnetic pressure can only be obtained when more

sophisticated models of the magnetic field evolution and its interaction with highly

magnetized atmospheric structure have become available and/or alternative models

been tested (however, for some of the estimates see discussion in Shulyak et al. 2007).

In the present work we made use of a simple geometrical 1D model of Lorentz force: the surface averaged values of the transverse magnetic field and the magnetic field modulus are introduced in the hydrostatic equation of the stellar matter. Future investigations can benefit from taking 2D effects into account with direct surface integration of the hydrogen line profiles computed with individual models. This could also probably open a possibility of accounting for the Hall's currents. Unfortunately, as mentioned above, this is difficult to do at present, but by no means impossible once more computational resources become available.

The dependence of the observed variability in hydrogen lines upon the magnetic field geometry and strength is one of the key elements in our investigation. If such a dependence exists, it could bring a number of theoretical constraints on the interaction of the magnetic field with stellar plasma. So far, we have analyzed only two stars with occasionally similar longitudinal magnetic field intensity. We are limited to stars for which the configuration of a magnetic field can be extracted from the literature and that can be observed with highly stable spectrometers like BOES to reduce possible errors in spectra processing. Thus, observations of other mCP stars are needed to conclude about the connection between magnetic field and variability seen in Balmer lines.

AcknowledgementsThe authors are thankful to Tanya Ryabchikova for her help preparing of line lists used in DI. We also acknowledge the use of cluster facilities at the Institute of Astronomy, Vienna University. This work was supported by the FWF Lise Meitner grant Nr. M998-N16 to D.S. O.K. is a Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences Research Fellow supported by a grant from the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation. Han acknowledges the support for this work from the Korea Foundation for International Cooperation of Science and Technology (KICOS) through grant No. 07-179. Based on INES data from the IUE satellite.

References

- Adelman, S. J. 1983, A&AS, 51, 511 [Google Scholar]

- Adelman, S. J., Malanushenko, V., Ryabchikova, T. A., & Savanov, I. 2001, A&A, 375, 982 [Google Scholar]

- Barklem, P. S., Piskunov, N., & O'Mara, B. J. 2000, A&A, 363, 1091 [Google Scholar]

- Bagnulo, S., Landi Degl'Innocenti, M., Landolfi, M., & Mathys, G. 2002, A&A, 394, 1023 [Google Scholar]

- Borra, E. F., & Landstreet, J. D. 1980, ApJS, 42, 421 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- García-Gil, A., García López, R. J., Allende Prieto, C., & Hubeny, I. 2005, ApJ, 623, 460 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzes, A. P. 1993, Peculiar versus Normal Phenomena in A-type and Related Stars, 44, IAU Coll.,138, 258 [Google Scholar]

- Hauck, B., & Mermilliod, M. 1998, A&AS, 129, 431 [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K. M., Jang, J. G., Chun, M. Y., et al. 2000, Publication of the Korean Astronomical Society, 15S, 119 (in Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Kang-Min, Han, Inwoo, Valyavin, Gennady, G., et al. 2007, PASP, 119, 1052 [Google Scholar]

- Khan, S., & Shulyak, D. 2006a, A&A, 448, 1153 [Google Scholar]

- Kochukhov, O., Drake, N. A., Piskunov, N., & de la Reza, R. 2004, A&A, 424, 935 [Google Scholar]

- Kochukhov, O., Khan, S., & Shulyak, D. 2005, A&A, 433, 671 [Google Scholar]

- Kochukhov, O. P. 2007, Physics of Magnetic Stars, 109 [Google Scholar]

- Kroll, R. 1989, Rev. Mex. Astron. Astrofis., 2, 194 [Google Scholar]

- Kupka, F., Piskunov, N., Ryabchikova, T. A., Stempels, H. C., & Weiss, W. W. 1999, A&AS, 138, 119 [Google Scholar]

- Landstreet, J. D. 2001, in Magnetic Fields Across Hertzsprung-Russell Diagram, ed. G. Mathys, S. K. Solanki, & D. T. Wickramasinghe, ASP Conf. Ser., 248, 277 [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann, H., Tkachenko, A., Fraga, L., Tsymbal, V., & Mkrtichian, D. E. 2007, A&A, 471, 941 [Google Scholar]

- Lipski, Ł., & Stepien, K. 2008, MNRAS, 385, 481 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolet, B. 1978, A&AS, 34, 1 [Google Scholar]

- Piskunov, N. E., Kupka, F., Ryabchikova, T. A., Weiss, W. W., & Jeffery, C. S. 1995, A&AS, 112, 525 [Google Scholar]

- Ryabchikova, T. A. 2003, in Magnetic Fields in O, B and A Stars, ed. L. A. Balona, H. F. Henrichs, & R. Medupe, ASP Conf. Ser., 305, 181 [Google Scholar]

- Shulyak, D., Tsymbal, V., Ryabchikova, T., Stütz Ch., & Weiss, W. W. 2004, A&A, 428, 993 [Google Scholar]

- Shulyak, D., Valyavin, G., Kochukhov, O., et al. 2007, A&A, 464, 1089, Paper I [Google Scholar]

- Valyavin, G., Kochukhov, O., & Piskunov, N. 2004, A&A, 420, 993 [Google Scholar]

- Valyavin, G., Kochukhov, O., Shulyak, D., et al. 2005, JKAS, 38, 283 [Google Scholar]

- van Leeuwen, F. 2007, A&A, 474, 653 [Google Scholar]

- Wrubel, M. H. 1952, ApJ, 116, 291 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Footnotes

- ... INES

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- http://ines.ts.astro.it/

All Tables

Table 1: Observations of 56 Ari.

Table 2:

Abundances (in

![]() )

of 56 Ari, used for determining model atmosphere

parameters.

)

of 56 Ari, used for determining model atmosphere

parameters.

All Figures

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=90,width=18cm]{figures/12615f1.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/01/aa12615-09/Timg37.png)

|

Figure 1:

Comparison of the observed and computed spectral energy distributions of 56 Ari.

Theoretical models correspond to

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{figures/12615f2.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/01/aa12615-09/Timg49.png)

|

Figure 2:

Comparison of the observed and computed H |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{figures/12615f3.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/01/aa12615-09/Timg50.png)

|

Figure 3:

Comparison of the longitudinal field observations of 56 Ari (symbols)

and the model curves for

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[height=9cm,angle=90]{figures/12615f4.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/01/aa12615-09/Timg69.png)

|

Figure 4:

The standard deviation |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\mbox{\includegraphics[width=6cm]{figures/12615f5a.ps}\includ...

...5e.ps}\includegraphics[height=6cm,angle=90]{figures/12615f5f.ps} }\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/01/aa12615-09/Timg75.png)

|

Figure 5:

The effective acceleration as a function of the Rosseland

optical depth for different rotation phases calculated for several magnetic field configurations and induced

e.m.f. The resulting standard deviations around H |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\mbox{\includegraphics[width=4cm]{figures/12615f6a.ps}\hspace...

...}\hspace{2.5mm}

\includegraphics[width=4cm]{figures/12615f6d.ps} }\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/01/aa12615-09/Timg84.png)

|

Figure 6: Magnetic field modulus and Lorentz force parameter as a function of rotation phase for several magnetic field models. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\mbox{\includegraphics[width=6cm]{figures/12615f7a.ps}\includ...

...res/12615f7b.ps}\includegraphics[width=6cm]{figures/12615f7c.ps} }\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/01/aa12615-09/Timg94.png)

|

Figure 7:

Residual profiles of the H |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

Copyright ESO 2010

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.