| Issue |

A&A

Volume 509, January 2010

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A52 | |

| Number of page(s) | 16 | |

| Section | Planets and planetary systems | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/200911716 | |

| Published online | 20 January 2010 | |

Deep imaging survey of young, nearby austral stars![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

VLT/NACO near-infrared Lyot-coronographic observations

G. Chauvin1 - A.-M. Lagrange1 - M. Bonavita2,3 - B. Zuckerman4 - C. Dumas5 - M. S. Bessell6 - J.-L. Beuzit1 - M. Bonnefoy1 - S. Desidera2 - J. Farihi7 - P. Lowrance8 - D. Mouillet1 - I. Song9

1 - Laboratoire d'Astrophysique, Observatoire de Grenoble, UJF, CNRS,

414 rue de la piscine, 38400 Saint-Martin d'Hères, France

2 -

INAF - Osservatorio Astronomico di Padova, Vicolo dell' Osservatorio 5, 35122 Padova, Italy

3 -

Universita' di Padova, Dipartimento di Astronomia, Vicolo dell'Osservatorio 2, 35122 Padova, Italy

4 -

Department of Physics & Astronomy and Center for Astrobiology,

University of California: Los Angeles, Box 951562, CA 90095, USA

5 -

European Southern Observatory: Casilla 19001, Santiago 19, Chile

6 -

Research School of Astronomy and Astrophysics Institute of Advance Studies,

Australian National University: Cotter Road, Weston Creek, Canberra, ACT 2611, Australia

7 -

Department of Physics & Astronomy, University of Leicester, Leicester LE1 7RH, UK

8 -

Spitzer Science Center, IPAC/Caltech: MS 220-6, Pasadena, CA 91125, USA

9 -

Department of Physics & Astronomy, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602-2451, USA

Received 23 January 2009 / Accepted 14 June 2009

Abstract

Context. High contrast and high angular resolution imaging

is the optimal search technique for substellar companions to nearby

stars at physical separations larger than typically 10 AU. Two

distinct populations of substellar companions, brown dwarfs and

planets, can be probed and characterized. As a result, fossile traces

of processes of formation and evolution can be revealed by physical and

orbital properties, both for individual systems and as an ensemble.

Aims. Since November 2002, we have conducted a large, deep

imaging, survey of young, nearby associations of the southern

hemisphere. Our goal is detection and characterization of substellar

companions with projected separations in the range 10-500 AU. We

have observed a sample of 88 stars, primarily G to M dwarfs, younger

than 100 Myr, and within 100 pc of Earth.

Methods. The VLT/NACO adaptive optics instrument of the ESO

Paranal Observatory was used to explore the faint circumstellar

environment between typically 0.1 and 10''. Diffraction-limited

observations in H and ![]() -band combined with Lyot-coronagraphy enabled us to reach primary star-companion brightness ratios as small as 10-6.

The existence of planetary mass companions could therefore be probed.

We used a standardized observing sequence to precisely measure the

position and flux of all detected sources relative to their visual

primary star. Repeated observations at several epochs enabled us to

discriminate comoving companions from background objects.

-band combined with Lyot-coronagraphy enabled us to reach primary star-companion brightness ratios as small as 10-6.

The existence of planetary mass companions could therefore be probed.

We used a standardized observing sequence to precisely measure the

position and flux of all detected sources relative to their visual

primary star. Repeated observations at several epochs enabled us to

discriminate comoving companions from background objects.

Results. We report the discovery of 17 new close (0.1-5.0'')

multiple systems. HIP 108195 AB and C (F1 III-M6),

HIP 84642 AB (![]() AU, K0-M5) and TWA22 AB (

AU, K0-M5) and TWA22 AB (![]() AU;

M6-M6) are confirmed comoving systems. TWA22 AB is likely to be a

rare astrometric calibrator that can be used to test evolutionary model

predictions. Among our complete sample, a total of 65 targets were

observed with deep coronagraphic imaging. About 240 faint companion

candidates were detected around 36 stars. Follow-up observations with

VLT or HST for 83% of these stars enabled us to identify a large

fraction of background contaminants. Our latest results that pertain to

the substellar companions to GSC 08047-00232, AB Pic and

2M1207 (confirmed during this survey and published earlier), are

reviewed. Finally, a statistical analysis of our complete set of

coronagraphic detection limits enables us to place constraints on the

physical and orbital properties of giant planets between typically 20

and 150 AU.

AU;

M6-M6) are confirmed comoving systems. TWA22 AB is likely to be a

rare astrometric calibrator that can be used to test evolutionary model

predictions. Among our complete sample, a total of 65 targets were

observed with deep coronagraphic imaging. About 240 faint companion

candidates were detected around 36 stars. Follow-up observations with

VLT or HST for 83% of these stars enabled us to identify a large

fraction of background contaminants. Our latest results that pertain to

the substellar companions to GSC 08047-00232, AB Pic and

2M1207 (confirmed during this survey and published earlier), are

reviewed. Finally, a statistical analysis of our complete set of

coronagraphic detection limits enables us to place constraints on the

physical and orbital properties of giant planets between typically 20

and 150 AU.

Key words: instrumentation: adaptive optics - instrumentation: high angular resolution - methods: observational - methods: statistical - brown dwarfs - planetary systems

1 Introduction

The search for substellar objects, either isolated or as companions to

nearby stars, has strongly motivated observers during the past two

decades. The detection and characterization of substellar objects

aids in understanding the formation and evolution of stars,

brown dwarfs and planets. Since the discovery of the first unambiguous

brown dwarf Gl229 B (Nakajima et al. 1995), the development of new imaging instruments

and observing techniques has diversified. Large surveys (2MASS,

Skrutskie et al. 1997; DENIS, Epchtein et al. 1997; SLOAN, York et al. 2000) are the best method for the study of isolated substellar

objects. Hundreds of brown dwarfs have been discovered in the field

motivating the introduction of the cool new L and T spectral classes

(Delfosse et al. 1997; Kirkpatrick et al 1999; Burgasser

et al. 1999). Dedicated spectroscopic observations of these cool

atmospheres offer an

opportunity to study physical and chemical processes

such as grain and molecule formation and vertical

mixing and cloud coverage. In the field, in young open clusters and in

star forming regions, study of the intial-mass function and of

stellar and substellar multiplicity reveals an apparent continuous

sequence supporting the idea that the same mechanisms (collapse, fragmentation,

ejection, photo-evaporation of accretion envelopes) form objects over a wide range of masses

from stars down to planets, as predicted by some theoretical models

(Bonnell et al. 2007; Burgasser et al. 2007; Zuckerman & Song

2009). Despite limited spatial resolution, a dozen substellar

companions to nearby stars have been discovered with wide (![]() 100 AU)

orbits (e.g., Goldman et al. 1999; Kirkpatrick et al. 2000; Wilson

et al. 2001).

100 AU)

orbits (e.g., Goldman et al. 1999; Kirkpatrick et al. 2000; Wilson

et al. 2001).

To access the near (![]() 5 AU) environment of stars, observing

techniques other than direct imaging

(e.g., precision radial velocity, transit, micro-lensing, pulsar-timing),

are best suited. The radial velocity (RV)

and transit techniques currently are the most successful methods for

detecting and characterizing properties of exo-planetary

systems. The RV surveys have focused on main sequence solar-type

stars, with numerous narrow optical lines and low activity, to ensure

high RV precision. Recently, planet-search programs have been extended

to lower and higher mass stars (Endl et al. 2006; Lagrange et

al. 2009a) and younger and more evolved systems (Joergens et al. 2006;

Johnson et al. 2007). Since the discovery of 51 Peg b (Mayor &

Queloz 1995), more than 300 exo-planets have been identified featuring

a broad range of physical (mass) and orbital (P, e) characteristics

(Udry & Santos 2007; Butler at al. 2006). The RV technique also

revealed the existence of a so-called brown dwarf desert at small

(

5 AU) environment of stars, observing

techniques other than direct imaging

(e.g., precision radial velocity, transit, micro-lensing, pulsar-timing),

are best suited. The radial velocity (RV)

and transit techniques currently are the most successful methods for

detecting and characterizing properties of exo-planetary

systems. The RV surveys have focused on main sequence solar-type

stars, with numerous narrow optical lines and low activity, to ensure

high RV precision. Recently, planet-search programs have been extended

to lower and higher mass stars (Endl et al. 2006; Lagrange et

al. 2009a) and younger and more evolved systems (Joergens et al. 2006;

Johnson et al. 2007). Since the discovery of 51 Peg b (Mayor &

Queloz 1995), more than 300 exo-planets have been identified featuring

a broad range of physical (mass) and orbital (P, e) characteristics

(Udry & Santos 2007; Butler at al. 2006). The RV technique also

revealed the existence of a so-called brown dwarf desert at small

(![]() 5 AU) orbital separations (Grether & Lineweaver 2006). The

bimodal aspect of the secondary mass distribution indicates different

formation mechanisms for two populations of substellar companions,

brown dwarfs and planets. The transit technique coupled with RV

enables determination of the radius and density of giant planets and

thus a probe of their internal structure. Moreover,

atmospheric constituents can be revealed during primary or secondary

eclipse (Swain et al. 2008; Grillmair et al. 2008).

5 AU) orbital separations (Grether & Lineweaver 2006). The

bimodal aspect of the secondary mass distribution indicates different

formation mechanisms for two populations of substellar companions,

brown dwarfs and planets. The transit technique coupled with RV

enables determination of the radius and density of giant planets and

thus a probe of their internal structure. Moreover,

atmospheric constituents can be revealed during primary or secondary

eclipse (Swain et al. 2008; Grillmair et al. 2008).

To extend detection and characterization to orbital semimajor axes

![]() 10 AU, the deep imaging technique is essential. To access

semimajor axes characteristic of the giant planets of our solar system,

even at the nearest stars either the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) or a

combination of Adaptive Optics (AO) and a large

ground-based telescope (Palomar, CFHT, Keck, Gemini, Subaru, VLT)

is mandatory. Moreover, deep imaging surveys take advantage

of exhaustive work on identification of young (

10 AU, the deep imaging technique is essential. To access

semimajor axes characteristic of the giant planets of our solar system,

even at the nearest stars either the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) or a

combination of Adaptive Optics (AO) and a large

ground-based telescope (Palomar, CFHT, Keck, Gemini, Subaru, VLT)

is mandatory. Moreover, deep imaging surveys take advantage

of exhaustive work on identification of young (![]() 100 Myr), nearby

(

100 Myr), nearby

(![]() 100 pc) stellar associations. Due to their youth and

proximity, such stars offer an ideal niche for detection of warm

planetary mass companions that are still moderately bright at

near-infrared wavelengths. Since the recognition of the TW Hydrae

Association (TWA; Kastner et al. 1997; Webb et al 999), more than 200

young, nearby stars have been identified. Many such stars reside in

several coeval moving groups (e.g., TWA,

100 pc) stellar associations. Due to their youth and

proximity, such stars offer an ideal niche for detection of warm

planetary mass companions that are still moderately bright at

near-infrared wavelengths. Since the recognition of the TW Hydrae

Association (TWA; Kastner et al. 1997; Webb et al 999), more than 200

young, nearby stars have been identified. Many such stars reside in

several coeval moving groups (e.g., TWA, ![]() Pictoris, Tucana-Horologium,

Pictoris, Tucana-Horologium,

![]() Cha, AB Dor, Columba and Carinae), sharing common kinematics,

photometric and spectroscopic properties (see Zuckerman & Song 2004,

hereafter ZS04;

Torres et al. 2008, T08). A few young brown dwarf companions have been

detected from space, HR 7329 B and TWA5 B (Lowrance et al. 2000, 1999), and from the ground, GSC 08047-00232 B

(Chauvin et al. 2005a). Companions down to the planetary mass regime were discovered

around the star AB Pic (Chauvin et al. 2005c) and the young brown dwarf 2M1207

(Chauvin et al. 2004, 2005b). Various deep imaging surveys of young, nearby

stars have recently been completed using different high contrast

imaging techniques such as coronagraphy, differential imaging or

L-band imaging (see Table 1). The telescope and the

instrument, the imaging mode (CI: coronagraphic imaging;

Sat-DI; saturated direct imaging; DI direct imaging; SDI: simultaneous

differential imaging; ADI: angular differential imaging) and filters,

the field of view (FoV) and the number of stars observed (#) are

given. The typical survey sensitivity in terms of planet mass is

reported in each reference. A significant

number have reported a null-detection of substellar

companions. Kasper et al. (2007), Lafrenière et al. (2007) and

Nielsen et al. (2008) initiated a statistical analysis to

constrain the physical and orbital properties (mass, period,

eccentricity distributions) of a giant planet population. Despite some limitations,

the approach is attractive and a first step in

characterizing the outer portions of exo-planetary systems.

Cha, AB Dor, Columba and Carinae), sharing common kinematics,

photometric and spectroscopic properties (see Zuckerman & Song 2004,

hereafter ZS04;

Torres et al. 2008, T08). A few young brown dwarf companions have been

detected from space, HR 7329 B and TWA5 B (Lowrance et al. 2000, 1999), and from the ground, GSC 08047-00232 B

(Chauvin et al. 2005a). Companions down to the planetary mass regime were discovered

around the star AB Pic (Chauvin et al. 2005c) and the young brown dwarf 2M1207

(Chauvin et al. 2004, 2005b). Various deep imaging surveys of young, nearby

stars have recently been completed using different high contrast

imaging techniques such as coronagraphy, differential imaging or

L-band imaging (see Table 1). The telescope and the

instrument, the imaging mode (CI: coronagraphic imaging;

Sat-DI; saturated direct imaging; DI direct imaging; SDI: simultaneous

differential imaging; ADI: angular differential imaging) and filters,

the field of view (FoV) and the number of stars observed (#) are

given. The typical survey sensitivity in terms of planet mass is

reported in each reference. A significant

number have reported a null-detection of substellar

companions. Kasper et al. (2007), Lafrenière et al. (2007) and

Nielsen et al. (2008) initiated a statistical analysis to

constrain the physical and orbital properties (mass, period,

eccentricity distributions) of a giant planet population. Despite some limitations,

the approach is attractive and a first step in

characterizing the outer portions of exo-planetary systems.

Table 1: Deep imaging surveys of young (<100 Myr), nearby (<100 pc) stars dedicated to the search for planetary mass companions and published in the literature.

Deep imaging surveys have also been performed on other classes of targets:

distant young associations (Taurus, Chamaeleon, Lupus, Upper Sco),

nearby intermediate-age (0.1-1.0 Gyr) stars, very nearby stars and

old stars with planets detected by RV. Some substellar

companions were detected with masses near the planet/brown dwarf

dividing line: DH Tau (Itoh et al. 2005), GQ Lup

(Neuhäuser et al. 2005), CHXR 73 (Luhman et al. 2006), HD 230030

(Metchev et al. 2006) and more recently 1RXS J160929.1-210524

(Lafrenière et al. 2008) and CT Cha (Schmidt et al. 2008).

Various teams

(McCarthy & Zuckerman 2004; Carson et al. 2005, 2006; Metchev et

al. 2008) have discussed an extension of the brown dwarf desert from small to

intermediate semimajor axes. Another purpose was to probe the existence

and impact of distant massive substellar companions in exoplanetary

systems detected by RV (Patience et al. 2002; Luhman & Jayawardhana

2002; Chauvin et al. 2006; Mugrauer et al. 2007; Eggenberger et

al. 2007). Recently, an important breakthrough was

achieved with the imaging detection of planetary mass

companions HR 8799 bcd (Marois et al. 2008b),

Fomalhaut b (Kalas et al. 2008) and the candidate ![]() Pic b (Lagrange et

al. 2009b). Such discoveries may become much more common following

arrival in coming years of a second generation of

deep imaging instruments such as Gemini Planet Imager (GPI; Macintosh et

al. 2006) and VLT/SPHERE (Dohlen et al. 2006).

Pic b (Lagrange et

al. 2009b). Such discoveries may become much more common following

arrival in coming years of a second generation of

deep imaging instruments such as Gemini Planet Imager (GPI; Macintosh et

al. 2006) and VLT/SPHERE (Dohlen et al. 2006).

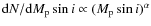

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=5.6cm]{11716fg1_a.ps}\includegraphics[...

...g1_e.ps}\includegraphics[width=5.6cm]{11716fg1_f.ps}\vspace*{2.5mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/01/aa11716-09/Timg32.png)

|

Figure 1:

Histrograms summarizing the main properties of the sample of

young, nearby stars observed with NACO at VLT. Top-left:

histogram of spectral types for the stars observed in coronagraphic

imaging (crossed lines) and in direct imaging (simple

lines). Top-middle: histogram of ages for members of known

young, nearby associtations (TWA, |

| Open with DEXTER | |

In this paper we report results of a deep coronographic imaging survey whose aim was discovery of substellar companions to young, nearby, austral stars. In comparison to previous work (see Table 1), our survey represents one of the largest and deepest obtained so far on this class of targets. This survey, intitiated in November 2000 with the ADONIS/SHARPII instrument on a 3.6 m telescope (Chauvin et al. 2003), was then extended with the VLT/NACO instrument between November 2002 and October 2007. In Sect. 2, the sample definition and properties are presented. In Sect. 3, we describe characteristics of the VLT/NACO instrument and the different observing modes that we used. The different observing campaigns, the atmospheric conditions and the observing strategy are detailed in Sect. 4. The dedicated data reduction and analysis to clean the science images, to calibrate our measurments, to derive the relative position and photometry of the detected sources in the NACO field of view and to estimate the detection performances are reported in Sect. 5. We then present the main results of our survey in Sect. 6, including the discovery of new close binary systems and the identification of background contaminants and comoving companions. In Sect. 7, we finally consider the detection sensitivity of our complete survey to statistically constrain the physical and orbital properties of a population of giant planets with 20-150 AU semimajor axes.

2 Sample selection

The building up of our target sample relied on a synergy between

previous exhaustive work on identification of young, nearby stars and

selection criteria (age, distance, binarity and observability) that

would optimize the detection of close-in planetary mass companions

with NACO at VLT. Youth indicators generally rely on photometry and

pre-main sequence isochrones, spectroscopy (especially of lithium and

H![]() ), and study of X-ray activity and IR excess (see ZS04).

Association membership is inferred from coordinates, proper motion,

radial velocity and distance estimation. Since the beginning of the

present survey, the number of known young, nearby stars more than

doubled and newly identified members were regularly included in our

target sample. Previously known binaries with

1.0-12.0''separation were excluded to avoid degrading the NACO AO and/or

coronagraphic detection performances.

), and study of X-ray activity and IR excess (see ZS04).

Association membership is inferred from coordinates, proper motion,

radial velocity and distance estimation. Since the beginning of the

present survey, the number of known young, nearby stars more than

doubled and newly identified members were regularly included in our

target sample. Previously known binaries with

1.0-12.0''separation were excluded to avoid degrading the NACO AO and/or

coronagraphic detection performances.

Our initial complete sample was composed of 88 stars; 51 are members

of young, nearby comoving groups, 32 are young, nearby stars currently

not identified as members of any currently known association and 5

have been reclassified by us as older (>100 Myr) systems. The sample

properties are summarized in Tables 2

and 3 and illustrated in

Fig. 1. ![]() of the selected stars are younger

than about 100 Myr and

of the selected stars are younger

than about 100 Myr and ![]() closer than 100 pc. The spectral types

cover the sequence from B to M spectral types with

closer than 100 pc. The spectral types

cover the sequence from B to M spectral types with ![]() BAF stars,

BAF stars,

![]() GK stars and

GK stars and ![]() M dwarfs. In

tables 2 and 3, in

addition to name, coordinates, galactic latitude (b),

spectral type, distance and V and K photometry, the observing

filter is given. All sources were observed in direct imaging, we have

therefore indicated the 65 stars observed in addition in coronagraphy

(CI). Finally, the multiplicity status of the primary and the presence

of companion candidates (CCs) are also reported. For the multiplicity

status we have flagged the following information: binary (B), triple

(T) and quadruple (Q); new (N) or known/cataloged (K) multiple system;

identified visual (VIS), Hipparcos astrometric (HIP) and spectroscopic

(SB) binary system; and a final flag in case of a confirmed physical

(Ph) or comoving (Co) system, but nothing if only an optical binary.

FS stars are from a paper by Fuhrmeister & Schmitt (2003).

M dwarfs. In

tables 2 and 3, in

addition to name, coordinates, galactic latitude (b),

spectral type, distance and V and K photometry, the observing

filter is given. All sources were observed in direct imaging, we have

therefore indicated the 65 stars observed in addition in coronagraphy

(CI). Finally, the multiplicity status of the primary and the presence

of companion candidates (CCs) are also reported. For the multiplicity

status we have flagged the following information: binary (B), triple

(T) and quadruple (Q); new (N) or known/cataloged (K) multiple system;

identified visual (VIS), Hipparcos astrometric (HIP) and spectroscopic

(SB) binary system; and a final flag in case of a confirmed physical

(Ph) or comoving (Co) system, but nothing if only an optical binary.

FS stars are from a paper by Fuhrmeister & Schmitt (2003).

Table 2: Sample of southern young, nearby stars observed during our VLT/NACO deep imaging survey.

Table 3: Sample of southern young, nearby stars observed.

For stars not in a known moving group (Table 3), based on existing

data we employed as many of the techniques for age dating as possible

(see, e.g., Sect. 3 in ZS04). The principal diagnostics were

lithium abundance, Galactic space motion UVW, and fractional X-ray

luminosity (Figs. 3, 6 and 4, respectively in ZS04). With the

possible exception of a few of the FS stars (see following paragraph),

all Table 3 stars with ages 100 Myr or less have UVW in or near the

``good UVW box'' in Fig. 6 of ZS04. With the exception of the A-type

stars (unknown lithium abundances), all Table 3 stars have lithium

abundances (we have measured) consistent with the ages we list and

their spectral type (as per Fig. 3 in ZS04). With the

exception of the A-type stars, X-ray fluxes are consistent with Fig. 4

in ZS04 for the indicated ages. Age uncertainties for

non-FS stars in Table 3 are typically ![]() of the tabulated age (i.e.,

of the tabulated age (i.e.,

![]() Myr,

Myr, ![]() Myr). The ages of the two A-type stars are

based on UVW and location on a young star HR diagram.

Myr). The ages of the two A-type stars are

based on UVW and location on a young star HR diagram.

When their radial velocity is known (based on our echelle spectra) then the FS stars usually have a ``good UVW''. In all cases they are strong X-ray emitters and also have H alpha in emission, usually strongly. Lithium is usually not detected in the FS stars, or occasionally weakly. Because the data sets for these stars are sometimes incomplete (e.g., radial velocity not measured) and because fractional X-ray luminosity and UVW are imprecise measures of age, we have assigned an age of 100 Myr to all observed FS stars. Perhaps a few FS stars have ages older than 100 Myr (FS 588 being the most likely of these). But, similarly, some are likely younger than 100 Myr. By assuming an overall uniform age of 100 Myr for the sample of FS stars, we are probably somewhat overestimating their mean age. The age determination of the ensemble of FS stars is likely to be accurate to within about a factor 2 in general, although the age of some FS stars could well lie outside of this range.

3 Observations

3.1 Telescope and instrument

NACO![]() is the first

Adaptive Optics instrument that was mounted at the ESO Paranal

Observatory near the end of 2001 (Rousset et al. 2002). NACO provides diffraction limited images in the near

infrared (nIR). The observing camera CONICA (Lenzen et al. 2002) is

equipped with a

is the first

Adaptive Optics instrument that was mounted at the ESO Paranal

Observatory near the end of 2001 (Rousset et al. 2002). NACO provides diffraction limited images in the near

infrared (nIR). The observing camera CONICA (Lenzen et al. 2002) is

equipped with a

![]() pixel Aladdin InSb array. NACO offers

a Shack-Hartmann visible wavefront sensor and a nIR wavefront

sensor for red cool (M5 or later spectral type) sources. nIR wavefront

sensing was used on only 8% of our sample. Note that in May 2004, the

CONICA detector was changed and the latter detector was more efficient

thanks to an improved dynamic, a lower readout noise and cleaner

arrays. Among NACO's numerous observing modes, only the direct and

coronagraphic imaging modes were used. The two occulting masks offered

for Lyot-coronagraphy have a diameter of

pixel Aladdin InSb array. NACO offers

a Shack-Hartmann visible wavefront sensor and a nIR wavefront

sensor for red cool (M5 or later spectral type) sources. nIR wavefront

sensing was used on only 8% of our sample. Note that in May 2004, the

CONICA detector was changed and the latter detector was more efficient

thanks to an improved dynamic, a lower readout noise and cleaner

arrays. Among NACO's numerous observing modes, only the direct and

coronagraphic imaging modes were used. The two occulting masks offered

for Lyot-coronagraphy have a diameter of

![]() and

and

![]() .

According to the atmospheric conditions, we used

the broad band filters H and

.

According to the atmospheric conditions, we used

the broad band filters H and ![]() ,

the narrow band filters, NB1.64,

NB1.75 and Br

,

the narrow band filters, NB1.64,

NB1.75 and Br![]()

![]() and a neutral density filter (providing a transmissivity

factor of 0.014). In order to correctly sample the NACO PSF (better

than Nyquist), the S13 and S27 objectives were used, offering mean

plate scales of 13.25 and 27.01 mas per pixel and fields of view

of

and a neutral density filter (providing a transmissivity

factor of 0.014). In order to correctly sample the NACO PSF (better

than Nyquist), the S13 and S27 objectives were used, offering mean

plate scales of 13.25 and 27.01 mas per pixel and fields of view

of

![]() and

and

![]() respectively.

respectively.

Our deep imaging survey was initiated during guaranteed time observations shared between different scientific programs and scheduled between November 2002 and September 2003. The survey was extended using open time observations between March 2004 and June 2007. The open time observations were shared between classical visitor mode and remote service mode as offered by ESO at the Paranal Observatory. For each campaign, we have reported in Table 4 the ESO programme numbers, the observation type, Guaranteed Time (GTO) or Open Time (OT), if obtained in visitor (Vis) or service (Ser) modes, the starting nights of observation, the number of nights allocated and the time loss. Finally, the number of visits, corresponging to the number of observing sequences executed on new and follow-up targets, is given.

3.2 Image quality

Table 4: Summary of the different observing campaigns of our survey.

For ground-based telescopes, atmospheric conditions have always been

critical to ensure astronomical observations of good quality. Although

AO instruments aim at compensating the distorsion induced by

atmospheric turbulence, the correction quality (generally measured by

the strehl ratio and Full Width Half Maximum (FWHM)

parameters) is still

related to the turbulence speed and strength. For bright targets, the

NACO AO system can correct for turbulence with a coherent time

(![]() )

longer than 2 ms. For faster (

)

longer than 2 ms. For faster (

![]() ms)

turbulence, the system is always late and the image quality and the

precision of astrometric and photometric measurements are consequently

degraded. During our NACO observing runs, the averaged

ms)

turbulence, the system is always late and the image quality and the

precision of astrometric and photometric measurements are consequently

degraded. During our NACO observing runs, the averaged ![]() was

about 5 ms and larger than 2 ms 80% of the time. The average seeing

conditions over all runs was equal to 0.8'' (which

happens to be the median seeing value measured in

Paranal over the last

decade

was

about 5 ms and larger than 2 ms 80% of the time. The average seeing

conditions over all runs was equal to 0.8'' (which

happens to be the median seeing value measured in

Paranal over the last

decade![]() ). Figure 2

shows the (strehl ratio) performances of the NACO AO system

with the visible wavefront sensor as a function of

the correlation time of the atmosphere

). Figure 2

shows the (strehl ratio) performances of the NACO AO system

with the visible wavefront sensor as a function of

the correlation time of the atmosphere ![]() ,

the seeing and the primary visible

magnitude. As expected, the

degradation of the performances

is seen with a decrease of

,

the seeing and the primary visible

magnitude. As expected, the

degradation of the performances

is seen with a decrease of ![]() ,

the coherent length (r0, inversely proportional to the seeing) and the

primary flux. Still, the results clearly demonstrate the good NACO

performances and capabilities over a wide range of observing conditions.

,

the coherent length (r0, inversely proportional to the seeing) and the

primary flux. Still, the results clearly demonstrate the good NACO

performances and capabilities over a wide range of observing conditions.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{11716fg2.eps}

\vspace*{-2mm}\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/01/aa11716-09/Timg48.png)

|

Figure 2:

VLT/NACO adaptive optics system performances. Strehl ratio at

2.20 |

| Open with DEXTER | |

3.3 Observing strategy

The VLT/NACO survey was conducted as a continuation of our earlier

coronographic survey with the ADONIS/SHARPII instrument at the ESO 3.6

m telescope at La Silla Observatory (Chauvin et al. 2003). A similar

observing strategy was adopted to optimize the detection of faint

close substellar companions. Most of our stars are relatively

bright (

![]() )

in nIR. To improve our detection performances, we

have opted for the use of Lyot coronography. High contrast imaging

techniques, such as Lyot and phase mask coronagraphy, L-band

saturated imaging and simultaneous differential imaging, enable

achievement of contrasts of 10-5 to 10-6. Their main

differences are inherent in the nature of the substellar companions

searched and the domain of separations explored. Broad-band nIR Lyot

coronagraphy and thermal (L'-band or 4

)

in nIR. To improve our detection performances, we

have opted for the use of Lyot coronography. High contrast imaging

techniques, such as Lyot and phase mask coronagraphy, L-band

saturated imaging and simultaneous differential imaging, enable

achievement of contrasts of 10-5 to 10-6. Their main

differences are inherent in the nature of the substellar companions

searched and the domain of separations explored. Broad-band nIR Lyot

coronagraphy and thermal (L'-band or 4 ![]() m) saturated imaging are

among the most sensitive techniques at typical separations between 1.0 to

10.0''. These contrast performances are currently essential to

access the planetary mass regime in searches for faint close

companions.

m) saturated imaging are

among the most sensitive techniques at typical separations between 1.0 to

10.0''. These contrast performances are currently essential to

access the planetary mass regime in searches for faint close

companions.

To measure precisely positions of faint sources detected in

a coronagraphic field relative to the primary star, a dedicated

observing block was executed. This block was composed of three

successive observing sequences and lasted in total ![]() 45 min

(including pointing). After centering a star behind the

coronagraphic mask, a deep coronagraphic observing sequence on source

was started. Several exposures of less than one minute each were

accumulated to monitor the star centering and the AO correction

stability. An effective exposure time of 300 s was generally spent

on target. During the second sequence, a neutral density or a narrow

band filter was inserted and the occulting mask and Lyot stop

removed. The goal was to precisely measure the star position behind

the coronagraphic mask (once corrected for filter shifts). An

effective exposure time of 60 s was spent on source. Counts were

adjusted to stay within the

45 min

(including pointing). After centering a star behind the

coronagraphic mask, a deep coronagraphic observing sequence on source

was started. Several exposures of less than one minute each were

accumulated to monitor the star centering and the AO correction

stability. An effective exposure time of 300 s was generally spent

on target. During the second sequence, a neutral density or a narrow

band filter was inserted and the occulting mask and Lyot stop

removed. The goal was to precisely measure the star position behind

the coronagraphic mask (once corrected for filter shifts). An

effective exposure time of 60 s was spent on source. Counts were

adjusted to stay within the ![]() linearity range of the detector. The

image is also used to estimate the quality of the AO

correction. Finally, the last sequence was the coronagraphic sky. This

measure was obtained

linearity range of the detector. The

image is also used to estimate the quality of the AO

correction. Finally, the last sequence was the coronagraphic sky. This

measure was obtained

![]() from the star using a jittering

pattern of several offset positions to avoid any stellar contaminants in the

final median sky. In case of positive detections, whenever possible,

the companion candidates (CCs) were re-observed to check whether a

faint object shared common proper motion with the primary

star. Depending on the proper motion of a given star (see

Fig. 1), the timespan between successive epochs

was about 1-2 years. When comoving companions were identified, images

were recorded with addditional nIR filters to directly compare the

spectral energy distribution with that predicted by (sub)stellar

evolutionary models.

from the star using a jittering

pattern of several offset positions to avoid any stellar contaminants in the

final median sky. In case of positive detections, whenever possible,

the companion candidates (CCs) were re-observed to check whether a

faint object shared common proper motion with the primary

star. Depending on the proper motion of a given star (see

Fig. 1), the timespan between successive epochs

was about 1-2 years. When comoving companions were identified, images

were recorded with addditional nIR filters to directly compare the

spectral energy distribution with that predicted by (sub)stellar

evolutionary models.

4 Data reduction and analysis

4.1 Cosmetic and image processing

Classical cosmetic reduction including bad pixels removal, flat-fielding, sky substraction and shift-and-add, was made with the Eclipse![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{11716fg3.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/01/aa11716-09/Timg53.png)

|

Figure 3:

Left: VLT/NACO corongraphic image of HIP 95270

obtained in H-band with the S13 camera. The small (

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

4.2 Astrometric calibration

The astrometric calibration of high angular resolution images as

provided by NACO is not a simple task. As NACO is not a

multi-conjugated AO system, the diffraction limited images have a

small FoV limited by the anisoplanetism angle. Therefore, classical

high-precision astrometric techniques over crowded fields of thousands

of stars cannot be transposed. In addition, ESO does not currently

provide any detector distorsion map. For this reason, astrometric

calibrators were observed within a week for each observing run (in

visitor and service mode) to determine a mean platescale and the true

north orientation. Our primary astrometric calibrator was the

![]() Ori C field observed with HST by McCaughrean & Stauffer

(1994). The same set of stars (TCC058, 057, 054, 034 and 026) were

observed with the same observing set-up (

Ori C field observed with HST by McCaughrean & Stauffer

(1994). The same set of stars (TCC058, 057, 054, 034 and 026) were

observed with the same observing set-up (![]() with S27 and H with

S13) to avoid introduction of systematic errors. When not observable,

we used as secondary calibrator the astrometric binary IDS21506S5133

(van Dessel & Sinachopoulos 1993), yearly recalibrated with the

with S27 and H with

S13) to avoid introduction of systematic errors. When not observable,

we used as secondary calibrator the astrometric binary IDS21506S5133

(van Dessel & Sinachopoulos 1993), yearly recalibrated with the

![]() Ori C field. The mean orientation of true north and the

mean platescale of the S13 and S27 cameras are reported in

Table 5.

Ori C field. The mean orientation of true north and the

mean platescale of the S13 and S27 cameras are reported in

Table 5.

Table 5: Mean plate scale and true north orientation for each observing run.

4.3 Companion candidate characterization

For direct imaging, relative photometry and astrometry of visual binaries were obtained using the classical deconvolution algorithm of Véran & Rigaut (1998). This algorithm is particularly adapted for stellar field analysis. Several PSF references were used to measure the influence of the AO correction. They were selected to optimize a set of observing criteria relative to the target observation (observing time, airmass, spectral type and V or K-band flux according to the wavefront sensor).

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm,clip]{11716fg4_a.ps}\includegraphics[width=8.8cm,clip]{11716fg4_b.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/01/aa11716-09/Timg88.png)

|

Figure 4:

Left: VLT/NACO coronagraphic detection limits in

H-band (combined with the S13 camera). The median detection limits are

given for different target spectral types (BAF, GK and M stars) and for

the 0.7'' (solid line) and 1.4'' (dash dotted

line) coronagraphic masks. Right: VLT/NACO coronagraphic

detection limits in |

| Open with DEXTER | |

In coronagraphy, the relative astrometry of the CCs

was obtained using a 2D-Gaussian PSF fitting. The deconvolution

algorithm of Véran & Rigaut (1998) and the maximization of the

cross-correlation function were applied using the primary star

(directly imaged) as PSF reference. The shifts (![]() 1 pixel)

induced between direct and coronagraphic images taken with different

filters, including neutral density, have been accounted for. For the relative

photometry, classical aperture (

1 pixel)

induced between direct and coronagraphic images taken with different

filters, including neutral density, have been accounted for. For the relative

photometry, classical aperture (

![]() )

photometry

with residual sky-subtraction and classical deconvolution were used.

For faint sources detected at less than

)

photometry

with residual sky-subtraction and classical deconvolution were used.

For faint sources detected at less than

![]() ,

background subtraction becomes more critical and is responsible for

larger uncertainties in the deconvolution analysis. Our analysis was

then limited to a 2D-Gaussian fitting coupled to aperture photometry

to derive the relative astrometry and photometry.

,

background subtraction becomes more critical and is responsible for

larger uncertainties in the deconvolution analysis. Our analysis was

then limited to a 2D-Gaussian fitting coupled to aperture photometry

to derive the relative astrometry and photometry.

For observations obtained at several epochs, the proper motion and parallactic motion of the primary star were taken into account to investigate the nature of detected faint CCs. The relative positions recorded at different epochs can be compared to the expected evolution of the position measured at the first epoch under the assumption that the CC is either a stationary background object or a comoving companion (see below). For the range of semi-major axes explored, any orbital motion can be considered of lower order compared with the primary proper and parallactic motions.

4.4 Detection limits

The coronagraphic detection limits were obtained using combined direct

and coronagraphic images. On the final coronagraphic image, the

pixel-to-pixel noise was estimated within a box of ![]() pixels

sliding from the star to the limit of the NACO field of view. Angular

directions free of any spike or coronagraphic support contamination

were selected. Additionally, the noise estimation was calculated

within rings of increasing radii, a method which is more pessimistic

at close angular separation due to the presence of coronagraphic PSF

non-axisymmetric residuals. Final detection limits at

pixels

sliding from the star to the limit of the NACO field of view. Angular

directions free of any spike or coronagraphic support contamination

were selected. Additionally, the noise estimation was calculated

within rings of increasing radii, a method which is more pessimistic

at close angular separation due to the presence of coronagraphic PSF

non-axisymmetric residuals. Final detection limits at ![]() were

obtained after division by the primary star maximum flux and

multiplication by a factor taking into account the ratio between the

direct imaging and coronagraphic integration times and the difference

of filter transmissions and bandwidths. Spectral type

correction due to the use of different filters has been simulated

and is smaller than 0.04 mag. The variation of the image quality

(strehl ratio) over the observation remains within 10% and

should not impact our contrast estimation by more than

0.1 mag. The median detection limits, using the sliding box method,

are reported in Fig. 4. They are given for

observations obtained in H- and

were

obtained after division by the primary star maximum flux and

multiplication by a factor taking into account the ratio between the

direct imaging and coronagraphic integration times and the difference

of filter transmissions and bandwidths. Spectral type

correction due to the use of different filters has been simulated

and is smaller than 0.04 mag. The variation of the image quality

(strehl ratio) over the observation remains within 10% and

should not impact our contrast estimation by more than

0.1 mag. The median detection limits, using the sliding box method,

are reported in Fig. 4. They are given for

observations obtained in H- and ![]() -bands, with the

-bands, with the

![]() and

and

![]() coronagraphic masks and

for different target spectral types (BAF, GK and M stars) and will

be used in the following statistical analysis of the survey.

coronagraphic masks and

for different target spectral types (BAF, GK and M stars) and will

be used in the following statistical analysis of the survey.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{11716fg5.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/01/aa11716-09/Timg93.png)

|

Figure 5:

VLT/NACO coronagraphic detection limits in |

| Open with DEXTER | |

At large separations (

![]() )

from the star when limited by

detector read-out noise or background noise, the contrast variation

with the primary spectral type is actually related to the primary nIR

brightness. This is shown in Fig. 5 in the case

of

)

from the star when limited by

detector read-out noise or background noise, the contrast variation

with the primary spectral type is actually related to the primary nIR

brightness. This is shown in Fig. 5 in the case

of ![]() -band detection limits at 5.0'' as a function of the

primary

-band detection limits at 5.0'' as a function of the

primary ![]() apparent magnitude. The contrast varies linearly due to

the flux normalization. At smaller separations, the situation is more

complex as deep AO images are limited by quasi-static speckle noise.

Then our detection limits remain constant over a wide range of

primary

apparent magnitude. The contrast varies linearly due to

the flux normalization. At smaller separations, the situation is more

complex as deep AO images are limited by quasi-static speckle noise.

Then our detection limits remain constant over a wide range of

primary ![]() apparent magnitudes.

apparent magnitudes.

All published deep imaging surveys dedicated to planet search

(Masciadri et al. 2005; Kasper et al. 2007; Lafrenière et al. 2007;

Biller et al. 2007), including this one, derived detection thresholds

assuming that residual noise in the final processed image follows

a Gaussian intensity distribution. A typical detection threshold at 5

or 6![]() is then usually assumed over the complete range of

angular separations.

Whereas the approximation of a Gaussian distribution for the

residual noise is valid within the detector read-out noise or

background noise regime, careful analysis by Marois et al. (2008a)

shows that this is not adequate at small separations when speckle

noise limited (typically

is then usually assumed over the complete range of

angular separations.

Whereas the approximation of a Gaussian distribution for the

residual noise is valid within the detector read-out noise or

background noise regime, careful analysis by Marois et al. (2008a)

shows that this is not adequate at small separations when speckle

noise limited (typically

![]() in our survey; see

Figs. 4 and 5). In this regime, AO deep images are limited not by

random, short-lived atmospheric speckles, but rather by instrumental

quasi-static speckles. A non-Gaussian distribution of the residual

noise must be taken into account to specify a detection threshold at a

given confidence level. Therefore, our current 6

in our survey; see

Figs. 4 and 5). In this regime, AO deep images are limited not by

random, short-lived atmospheric speckles, but rather by instrumental

quasi-static speckles. A non-Gaussian distribution of the residual

noise must be taken into account to specify a detection threshold at a

given confidence level. Therefore, our current 6![]() detection

threshold at small separations is probably too optimistic. However,

the systematic error induced in our sensitivity limits is probably of

less significance than uncertainties in planet age and use of

uncalibrated planet evolutionary models as described below.

detection

threshold at small separations is probably too optimistic. However,

the systematic error induced in our sensitivity limits is probably of

less significance than uncertainties in planet age and use of

uncalibrated planet evolutionary models as described below.

5 Results

The main purpose of our survey was detection of brown dwarf and planetary mass companions while employing a deep imaging technique on an optimized sample of nearby stars. Our strategy has been sucessful with the confirmation of a brown dwarf companion to GSC 08047-00232 (Chauvin et al. 2003, 2005a) and discoveries of a planetary mass companion to the young brown dwarf 2MASSW J1207334-393254 (hereafter 2M1207; Chauvin et al. 2004; 2005c) and a companion at the planet/brown dwarf boundary to the young star AB Pic (Chauvin et al. 2005b).

In this section, we detail the three main results of this survey:

- 1.

- identification of many background sources along lines of sight close to those of our young, nearby stars. Such identifications are necessary for statistical analysis of our detection limits (see below). These identifications serve in addition as preparation for future deep imaging searches of these stars for exoplanets;

- 2.

- discovery of several new close stellar multiple systems, notwithstanding our binary rejection process. Three systems are actually confirmed to be comoving. One is a possible low-mass calibrator for predictions of stellar evolutionary models;

- 3.

- review of the status of three previously proposed substellar companions, as confirmed with NACO.

5.1 Identification of background sources

Among the complete sample of 88 stars, a total of 65 were observed with coronagraphic imaging. The remaining 23 targets were observed in direct or saturated imaging because the system was resolved as a 1.0-12'' visual binary inappropriate for deep coronagraphic imaging, because atmospheric conditions were unstable, or because the system was simply too faint to warrant efficient use of the coronagraphic mode.

Among the 65 stars observed with both direct imaging and coronagraphy,

nothing was found around 29 (45%) stars and at least one CC was

detected around the 36 (55%) others. A total of ![]() 236 CCs were

detected. To identify their nature, 14 (39%) systems were observed at

two epochs (at least) with VLT and 16 (44%) have combined VLT and HST

observations at more than a one year interval (Song et al. 2009, in

prep.). Finally, 6 (17%) were observed at only one epoch and require

further follow-up observations. The position and photometry of each

detected CC relative to its primary star, at each epoch, are given in

Tables 8-14. Target name, observing date and set-up are given, as

well as the different sources identified with their relative position

and relative flux, and their identification status based on follow-up

observations. Sources are indicated as undefined (U) were observed at

only one epoch, (B) for stationary background contaminants and (C) for

confirmed comoving companions. When VLT data are combined with those

from other telescopes (HST, USNO, 2MASS), a flag or a reference is

reported in the last column.

236 CCs were

detected. To identify their nature, 14 (39%) systems were observed at

two epochs (at least) with VLT and 16 (44%) have combined VLT and HST

observations at more than a one year interval (Song et al. 2009, in

prep.). Finally, 6 (17%) were observed at only one epoch and require

further follow-up observations. The position and photometry of each

detected CC relative to its primary star, at each epoch, are given in

Tables 8-14. Target name, observing date and set-up are given, as

well as the different sources identified with their relative position

and relative flux, and their identification status based on follow-up

observations. Sources are indicated as undefined (U) were observed at

only one epoch, (B) for stationary background contaminants and (C) for

confirmed comoving companions. When VLT data are combined with those

from other telescopes (HST, USNO, 2MASS), a flag or a reference is

reported in the last column.

For multi-epoch observations, to statistically test the probability

that the CCs are background objects or comoving companions, a ![]() probability test of

probability test of

![]() degrees of freedom

(corresponding to the measurements: separations in the

degrees of freedom

(corresponding to the measurements: separations in the

![]() and

and

![]() directions for the number

directions for the number

![]() of epochs)

was applied. This test takes into account the uncertainties in the

relative positions measured at each epoch and the uncertainty in the

primary proper motion and parallax (or

distance). Figure 6 gives an illustration of a

(

of epochs)

was applied. This test takes into account the uncertainties in the

relative positions measured at each epoch and the uncertainty in the

primary proper motion and parallax (or

distance). Figure 6 gives an illustration of a

(

![]() ,

,

![]() )

diagram that was used to identify a

stationary background object near 0ES1847. A status of each CC has

been assigned as confirmed companion (C;

)

diagram that was used to identify a

stationary background object near 0ES1847. A status of each CC has

been assigned as confirmed companion (C;

![]() %),

background contaminant (B;

%),

background contaminant (B;

![]() %), probably background

(PB;

%), probably background

(PB;

![]() %, but combining data from two different

instruments) and undefined (U). Over the complete coronagraphic

sample, 1% of the CCs detected have been confirmed as comoving

companions, 43% have been identified as probable background

contaminants and about 56% need further follow-up observations. The

remaining CCs come mostly from crowded background fields in the field

of view of 6 stars observed at one epoch.

%, but combining data from two different

instruments) and undefined (U). Over the complete coronagraphic

sample, 1% of the CCs detected have been confirmed as comoving

companions, 43% have been identified as probable background

contaminants and about 56% need further follow-up observations. The

remaining CCs come mostly from crowded background fields in the field

of view of 6 stars observed at one epoch.

Among the 23 stars and brown dwarfs observed only in direct or

saturated imaging, several have been resolved as tight multiple

systems (see below). 4 stars (FS1174, FS979, FS1017 and FS1035) have

at least one substellar CC (see

Tables 12, 13

and 14). FS1035 was observed at two

successive epochs and the faint source detected at

![]() has

been identified as a background object.

has

been identified as a background object.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{11716fg6.ps}\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{11716fg7.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/01/aa11716-09/Timg105.png)

|

Figure 6: VLT/NACO Measurements (filled circles with uncertainties) of the offset positions of a comoving companion AB Pic b to the primary star ``A'' (left) and of a CC relative to 0ES1847 (right). For each diagram, the expected variation of offset positions, if the candidate is a background object, is shown (curved line). The variration is estimated based on the parallactic and proper motions of the primary star, as well as the initial offset position of the CC from A. The empty squares give the corresponding expected offset positions of a background object for various epochs of observations (with uncertainties). In the case of AB Pic b, the relative positions do not change with time confirming that AB Pic b is comoving. On the contrary, the relative position of the CC to 0ES1847 varies in time as predicted for a stationary background object. For our sample, astrometric follow-up over 1-2 years enabled a rapid identification of true companions. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{11716fg8.eps}\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{11716fg9.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/01/aa11716-09/Timg106.png)

|

Figure 7: New visual binaries resolved with NACO at VLT. HIP 108195 AB, HIP 84642 AB and TWA22 AB were in addition confirmed as comoving multiple systems. TWA22 AB was monitored for 4 years to constrain the binary orbit and determine its total dynamical mass (see Bonnefoy et al. 2009, accepted). |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=7cm]{11716fg10.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/01/aa11716-09/Timg107.png)

|

Figure 8:

Composite VLT/NACO |

| Open with DEXTER | |

5.2 Close stellar multiple systems

5.2.1 New visual binaries

Our survey was not aimed at detecting new stellar binaries. Known

bright equal-mass binaries of

1.0-12.0'' separation were rejected

from our sample as they degrade the coronagraphic detection

performances by limiting dynamical range. A few tight binaries were

kept when both components could be placed behind the coronagraphic

masks. Despite our binary rejection process, 17 new close visual

multiple systems were resolved (see Figs. 7 and

8). They include 13 tight resolved binaries and 4

triple systems. Their relative flux and position are reported in

Table 6. Their separations range between

0.1-5.0'' and their H and ![]() contrasts between

0.0-4.8 mag. Among them, HIP 108195 ABC, HIP 84642 AB and

TWA22 AB were observed at different epochs and are confirmed as

comoving systems.

contrasts between

0.0-4.8 mag. Among them, HIP 108195 ABC, HIP 84642 AB and

TWA22 AB were observed at different epochs and are confirmed as

comoving systems.

5.2.2 The comoving multiple systems HIP 108195 ABC and HIP 84642 AB

Close to the Hipparcos double star HIP 108195 AB (F3, 46.5 pc),

member of Tuc-Hor, we resolved a faint source at 4.96''

(

![]() AU; i.e.

AU; i.e. ![]() AU). In addition to a

confirmation that HIP 108195 AB is a comoving pair, we found that

the fainter source is a third component of this comoving multiple

system (Fig. 8). Combined distance, age and

apparent photometry are compatible with an M5-M7 dwarf according to

PMS model predictions (Siess et al. 2000) and places the companion at

the stellar/brown dwarf boundary.

AU). In addition to a

confirmation that HIP 108195 AB is a comoving pair, we found that

the fainter source is a third component of this comoving multiple

system (Fig. 8). Combined distance, age and

apparent photometry are compatible with an M5-M7 dwarf according to

PMS model predictions (Siess et al. 2000) and places the companion at

the stellar/brown dwarf boundary.

HIP 84642 (K0, 58.9 pc) is not reported as a double star in the

Hipparcos Visual Double Stars catalog (Dommanget & Nys 2000),

possibly due to the small angular separation and large flux ratio.

Based on images from our VLT/NACO

programme combined with those from the SACY

survey (Huélamo et al. 2009, in prep.),

we confirm that the companion shares common proper motion with

HIP 84642. The companion is likely to be an M4-M6 young dwarf based on

comparison of

photometry to predictions of PMS models. Based on the statistical

relation between projected separation and semi-major axis of Couteau

(1960), HIP 84642 AB is likely to be a tight (

![]() AU;

AU;

![]() AU; K0-M5) binary with a period of several tens of years.

AU; K0-M5) binary with a period of several tens of years.

Table 6:

Relative positions and ![]() and H-band contrast of the new

binaries resolved by NACO at VLT.

and H-band contrast of the new

binaries resolved by NACO at VLT.

5.2.3 The young, tight astrometric binary TWA22 AB

The tight (![]() 100 mas;

100 mas; ![]() AU) binary TWA22 AB was observed at several

epochs. We aimed at monitoring the system orbit to determine the total

dynamical mass using an accurate distance determination

(

AU) binary TWA22 AB was observed at several

epochs. We aimed at monitoring the system orbit to determine the total

dynamical mass using an accurate distance determination

(

![]() pc, Texeira et al. 2009, submitted). The physical properties

(luminosity, effective temperature and surface gravity) of each

component were obtained based on near-infrared photometric and

spectroscopic observations. By comparing these parameters with

evolutionary model predictions, we consider the age and the

association membership of the binary. A possible under-estimation of

the mass predicted by evolutionary models for young stars close to the

substellar boundary is presented in two dedicated papers (Bonnefoy

et al. 2009, accepted; Texeira et al. 2009, accepted).

pc, Texeira et al. 2009, submitted). The physical properties

(luminosity, effective temperature and surface gravity) of each

component were obtained based on near-infrared photometric and

spectroscopic observations. By comparing these parameters with

evolutionary model predictions, we consider the age and the

association membership of the binary. A possible under-estimation of

the mass predicted by evolutionary models for young stars close to the

substellar boundary is presented in two dedicated papers (Bonnefoy

et al. 2009, accepted; Texeira et al. 2009, accepted).

5.3 Substellar companions

We review below the latest results about the three substellar companions GSC 08047-00232 B, AB Pic b and 2M1207 b since their initial companionship confirmation. Recent age, distance, astrometric and spectroscopic measurements enable us to refine their predicted physical properties and their origin in regards to other confirmed substellar companions in young, nearby associations.

5.3.1 GSC 08047-00232 B

Based on the ADONIS/SHARPII observations of two dozen probable

association members of Tuc-Hor, Chauvin et al. (2003) identified a

![]()

![]() candidate to GSC 08047-00232 (CoD-52381). This

candidate was independently detected by Neuhäuser et al. (2003) with

the SHARP instrument at the ESO New Technology Telescope

(NTT). Neuhäuser & Guenther (2004) acquired H- and K-band

spectra and derived a spectral type M

candidate to GSC 08047-00232 (CoD-52381). This

candidate was independently detected by Neuhäuser et al. (2003) with

the SHARP instrument at the ESO New Technology Telescope

(NTT). Neuhäuser & Guenther (2004) acquired H- and K-band

spectra and derived a spectral type M![]() ,

corroborated by Chauvin

et al. (2005a). Finally, in the course of our VLT/NACO observations,

we confirmed that GSC 08047-00232 B was comoving with A (Chauvin et al. 2005a). Mass, effective temperature, and luminosity of B were

determined by comparing its JHK photometry with evolutionary model

predictions and the Tuc-Hor age and photometric distance for the

system. The results are reported in Table 7 and compared to the

complete list of confirmed substellar companions discovered among the young,

nearby associations. Tentative spectral types have

been determined from nIR spectroscopic observations, whereas masses

and effective temperatures are predicted by evolutionary models

based on the nIR photometry, the age and the distance to the system.

Membership in Tuc-Hor and the assigned age of

GSC 08047-00232 AB have been debated for a time. Further studies of

loose young associations sharing common kinematical and physical

properties recently led Torres et al. (2008) to identify

GSC 08047-00232 AB as a high-probability (80%)

member of the

Columba association of age 30 Myr, confirming the young age and the

brown dwarf status of GSC 08047-00232 B.

,

corroborated by Chauvin

et al. (2005a). Finally, in the course of our VLT/NACO observations,

we confirmed that GSC 08047-00232 B was comoving with A (Chauvin et al. 2005a). Mass, effective temperature, and luminosity of B were

determined by comparing its JHK photometry with evolutionary model

predictions and the Tuc-Hor age and photometric distance for the

system. The results are reported in Table 7 and compared to the

complete list of confirmed substellar companions discovered among the young,

nearby associations. Tentative spectral types have

been determined from nIR spectroscopic observations, whereas masses

and effective temperatures are predicted by evolutionary models

based on the nIR photometry, the age and the distance to the system.

Membership in Tuc-Hor and the assigned age of

GSC 08047-00232 AB have been debated for a time. Further studies of

loose young associations sharing common kinematical and physical

properties recently led Torres et al. (2008) to identify

GSC 08047-00232 AB as a high-probability (80%)

member of the

Columba association of age 30 Myr, confirming the young age and the

brown dwarf status of GSC 08047-00232 B.

5.3.2 AB Pic b

During our survey, a ![]()

![]() companion was discovered near the

young star AB Pic (Chauvin et al. 2005b). Initially identified by

Song et al. (2003) as a member of Tuc-Hor, the membership of AB Pic

has been recently discussed by Torres et al. (2008) who attached this

star to the young (

companion was discovered near the

young star AB Pic (Chauvin et al. 2005b). Initially identified by

Song et al. (2003) as a member of Tuc-Hor, the membership of AB Pic

has been recently discussed by Torres et al. (2008) who attached this

star to the young (![]() 30 Myr) Columba association. Additional

astrometric measurements of the relative position of AB Pic b to A

firmly confirm the companionship reported by Chauvin et al. (2005b;

see Fig. 6, left panel). Based on age, distance

and nIR photometry, Chauvin et al. (2005b) derived the physical

properties of AB Pic b based on evolutionary models (see Table 7). As

per the three young substellar companions to TWA5A, HR7329 and

GSC 08047-00232, AB Pic b is located at a projected physical

separation larger than 80 AU. Formation by core accretion of

planetesimals seems unlikely because of inappropriate timescales to

form planetesimals at such large distances. Gravitational

instabilities within a protoplanetary disk (Papaloizou & Terquem

2001; Rafikov 2005; Boley 2009) or Jeans-mass fragmentation proposed for brown

dwarf and stellar formation appear to be more probable pathways to

explain the origin of the Table 7 secondaries.

30 Myr) Columba association. Additional

astrometric measurements of the relative position of AB Pic b to A

firmly confirm the companionship reported by Chauvin et al. (2005b;

see Fig. 6, left panel). Based on age, distance

and nIR photometry, Chauvin et al. (2005b) derived the physical

properties of AB Pic b based on evolutionary models (see Table 7). As

per the three young substellar companions to TWA5A, HR7329 and

GSC 08047-00232, AB Pic b is located at a projected physical

separation larger than 80 AU. Formation by core accretion of

planetesimals seems unlikely because of inappropriate timescales to

form planetesimals at such large distances. Gravitational

instabilities within a protoplanetary disk (Papaloizou & Terquem

2001; Rafikov 2005; Boley 2009) or Jeans-mass fragmentation proposed for brown

dwarf and stellar formation appear to be more probable pathways to

explain the origin of the Table 7 secondaries.

Table 7:

Properties of the confirmed comoving substellar companions discovered

in the young, nearby associations: TW Hydrae (TWA), ![]() Pictoris

(

Pictoris

(![]() Pic), Columba (Col) and Carina (Car).

Pic), Columba (Col) and Carina (Car).

5.3.3 2M1207 b

Among the young candidates of our sample, a small number of very low

mass stars and brown dwarfs were selected to take advantage of the

unique capability offered by NACO at VLT to sense the wavefront in the

IR. Most were observed in direct and saturated imaging. This strategy

proved to be successful with the discovery of a planetary mass

companion in orbit around the young brown dwarf 2M1207 (Chauvin et al. 2004, 2005c). HST/NICMOS observations independently confirmed this

result (Song et al. 2006). A low signal-to-noise spectrum in H-band

enabled Chauvin et al. (2004) to suggest a mid to late-L dwarf

spectral type, supported by its very red nIR colors. Additional low

signal-to-noise spectroscopic observations compared with synthetic

atmosphere spectra led Mohanty et al. (2007) to suggest an effective

spectroscopic temperature of

![]() K and a higher mass of

K and a higher mass of

![]() .

To explain the companion under-luminosity,

Mohanty et al. (2007) have suggested the existence of a

circum-secondary edge-on disk responsible for a gray extinction of

.

To explain the companion under-luminosity,

Mohanty et al. (2007) have suggested the existence of a

circum-secondary edge-on disk responsible for a gray extinction of

![]() 2.5 mag between 0.9 and 3.8

2.5 mag between 0.9 and 3.8 ![]() m. However, synthetic

atmosphere models clearly encounter difficulties in describing

faithfully the late-L to mid-T dwarfs transition (

m. However, synthetic

atmosphere models clearly encounter difficulties in describing

faithfully the late-L to mid-T dwarfs transition (![]() 1400 K for

field L/T dwarfs), corresponding to the process of cloud

clearing. Similar difficulties have been encountered by Marois

et al. (2008b) to reproduce all photometric data of the three

planetary mass companions to HR 8799 that fall also near the edge of

the transition from cloudy to cloud-free atmospheres. In the

case of 2M1207 b, future spectroscopic or polarimetric observations

should help to distinguish between the two scenarios (obscured or

non-obscured by a circumstellar disk). Recent precise parallax

determinations (Gizis et al. 2007; Ducourant et al. 2008) allowed a

reevaluation of the distance and the physical properties of the

companion (see Table 7).

1400 K for

field L/T dwarfs), corresponding to the process of cloud

clearing. Similar difficulties have been encountered by Marois

et al. (2008b) to reproduce all photometric data of the three

planetary mass companions to HR 8799 that fall also near the edge of

the transition from cloudy to cloud-free atmospheres. In the

case of 2M1207 b, future spectroscopic or polarimetric observations

should help to distinguish between the two scenarios (obscured or

non-obscured by a circumstellar disk). Recent precise parallax

determinations (Gizis et al. 2007; Ducourant et al. 2008) allowed a

reevaluation of the distance and the physical properties of the

companion (see Table 7).

6 Statistical analysis

6.1 Context

Over the past few years, a significant number of deep imaging surveys

dedicated to the search for

exoplanets around young, nearby stars have appeared (Chauvin et al. 2003;

Neuhäuser et al. 2003; Lowrance et al. 2005; Masciadri et al. 2005; Biller et al. 2007; Kasper et al. 2007; Lafreniére et al. 2007). Various instruments and telescopes were used with different

imaging techniques (coronagraphy, angular or spectral differential

imaging, L'-band imaging) and observing strategies. None of those

published surveys have reported the detection of planetary mass

companions that could have formed by a core-accretion model (as

expected for a large fraction of planets reported by RV

measurements). Several potential planetary mass companions were

discovered, but generally at relatively large physical separations or

with a small mass-ratio with their primaries, suggesting a formation

mechanisms similar to (sub)stellar binaries and stars. Only

recently, planet candidates perhaps formed by core-accretion have been

imaged around the A-type stars Fomalhaut (Kalas et al. 2008), HR 8799

(Marois et al. 2008b) and ![]() Pictoris (Lagrange et al. 2009b),

initiating the study of giant exo-planets at the (mass, distance)

scale of our solar system.

Pictoris (Lagrange et al. 2009b),

initiating the study of giant exo-planets at the (mass, distance)

scale of our solar system.

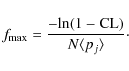

Confronted with a null-detection of planets formed by core-accretion, several groups (Kasper et al. 2007; Lafrenière et al. 2007; Nielsen et al. 2008) have developed statistical analysis tools to exploit the complete deep imaging performances of their surveys. A first approach is to test the consistency of various sets of (mass, eccentricity, semi-major axes) parametric distributions of a planet population in the specific case of a null detection. A reasonable assumption is to extrapolate and normalize planet mass, period and eccentricity distributions using statistical results of RV studies at short periods. Given the detection sensitivity of a survey, the rate of detected simulated planets (over the complete sample) enables derivation of the probability of non-detection of a given planet population associated with a normalized distribution set. Then comparison with a survey null-detection sample tests directly the statistical significance of each distribution and provides a simple approach for constraining the outer portions of exoplanetary systems.