| Issue |

A&A

Volume 508, Number 1, December II 2009

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Page(s) | 329 - 337 | |

| Section | Stellar structure and evolution | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/200913044 | |

| Published online | 15 October 2009 | |

A&A 508, 329-337 (2009)

The hard to soft spectral transition in LMXBs-affected by recondensation of gas into an inner disk

E. Meyer-Hofmeister1 - B. F. Liu2 - F. Meyer1

1 - Max-Planck-Institut für Astrophysik, Karl-Schwarzschildstr. 1, 85740 Garching, Germany

2 - National Astronomical Observatories/Yunnan Observatory, Chinese

Academy of Sciences, PO Box 110, Kunming 650011, PR China

Received 31 July 2009 / Accepted 8 September 2009

Abstract

Context. Soft and hard spectral states of X-ray transient

sources reflect two modes of accretion, accretion via a geometrically

thin, optically thick disk or an advection-dominated accretion flow

(ADAF).

Aims. The luminosity at transition between these two states

seems to vary from source to source, or even for the same source during

different outbursts, as observed for GX 339-4. We investigate how the

existence of an inner weak disk in the hard state affects the

transition luminosity.

Methods. We evaluate the structure of the corona above an outer

truncated disk and the resulting disk evaporation rate for different

irradiation.

Results. In some cases, recent observations of X-ray transients

indicate the presence of an inner cool disk during the hard state. Such

a disk can remain during quiescence after the last outburst as long as

the luminosity does not drop to very low values (10-4-10-3

of the Eddington luminosity). Consequently, as part of the matter

accretes via the inner disk, the hard irradiation is reduced. The hard

irradiation is further reduced, occulted and partly reflected by the

inner disk. This leads to a hard-soft transition at a lower luminosity.

Conclusions. The spectral state transition is expected at lower

luminosity if an inner disk exists below the ADAF. This seems to be

supported by observations for GX 339-4.

Key words: accretion, accretion disks - X-rays: binaries - black hole physics - galaxies: active - stars: neutron

1 Introduction

Accretion onto black holes is an interesting phenomenon since the

main features are similar for stellar mass and supermassive black

holes. Concerning both groups of sources, different

solutions of the hydrodynamic equations of viscous

differentially rotating flows are known (for a discussion see Narayan

et al. 1998).

The two common modes of accretion are either

via a geometrically thin, optically thick disk reaching

inward to the last stable orbit (for accretion rates between a few

percent up to almost the Eddington rate), or, via an outer disk

truncated some distance from the center, and a hot optically

thin, geometrically extended advection-dominated flow (ADAF) in the

inner region. This latter type of accretion flow, present for accretion

rates below a few percent of the Eddington rate, was mainly

investigated by Narayan and collaborators (Narayan & Yi 1994, 1995a,b; and Abramowicz et al. 1995). If the mass accretion rates and the radii are scaled to the Eddington accretion rate (

![]() electron scattering opacity,

electron scattering opacity, ![]() radiation efficiency) and Schwarzschild radius (

radiation efficiency) and Schwarzschild radius (

![]() )

the basic equations are the same for small and large black holes and

for neutron stars. These two main accretion regimes are present in

low-mass X-ray binaries (LMXBs) and active galactic nuclei (AGN).

)

the basic equations are the same for small and large black holes and

for neutron stars. These two main accretion regimes are present in

low-mass X-ray binaries (LMXBs) and active galactic nuclei (AGN).

New data of X-ray properties of black holes in AGN from the Chandra X-ray Observatory allow us to study the accretion process also for AGN of low luminosity in more detail, especially galactic nuclei with an ADAF near the center (for a review see Ho 2008). The galaxies can have different nuclear activity ranging from luminous AGN to the least active galaxies such as our Galaxy (for a review see Yuan 2007). To understand the physical processes in supermassive black hole accretion, one can make use of the knowledge gained from studying low-mass X-ray binaries (LMXBs). For these systems, spectral state transitions and other detailed features can be observed and studied. The innermost regime around the black hole also is of interest as relativistic features can allow the determination of black hole spin (Miller 2007; Miller et al. 2009).

Our investigation concerns the transition from a hard spectral state to a soft spectral state due to an increase of the mass flow rate in the accretion disk as happens during the rise to outburst. The now commonly accepted picture for the state transition is related to the change of the accretion mode in the inner region from an ADAF (with a hard spectrum originating from the very hot ADAF) to a thin disk extending inward to the last stable orbit (with a soft black body spectrum). For an updated account of the ADAF model see Narayan & McClintock (2008).

Fits confirming truncated disks with inner ADAF-filled regions were worked out for LMXBs, first for A0620-00 and V404 Cyg (Narayan et al. 1996, 1997). Esin (1997) applied the model to state transitions observed for SXT Nova Muscae and Cyg X-1, leading to a description of the configuration of the accretion geometry for different spectral states that varies with the mass flow rate (Esin et al. 1997), adequate for black holes of different mass. Applications to Galactic nuclei were equally successful; the first application concerned Sgr A* and successfully explained its low radiative efficiency (Narayan et al. 1995). For a review of early investigations of AGN see Narayan et al. (1998).

The investigation of the interaction between a coronal flow and an outer accretion disk led to the result that heat conduction causes evaporation of matter from the disk to the hot flow (Meyer et al. 2000a; Liu et al. 2002). An equilibrium establishes between the cool disk flow and the hot flow. The balance between disk mass accretion rate and evaporation rate determines where the disk flow changes to an ADAF. This process explains the location of the disk truncation as well as the dependence of the spectral state transition on the accretion rate (Meyer et al. 2000b).

Over the past several years, a large number of observations has become available. Current X-ray missions (in particular Chandra and XMM-Newton) have a sensitivity that allows us to study the accretion flow, ADAF or disk flow, as well as the transitions between them, in detail. Most sources were detected in the high luminosity, soft spectral state. If in outburst the rise and the decline phase could be observed, and possibly both spectral state transitions, it was found that the luminosity at hard/soft transition during the rise to outburst usually was higher than the one at the soft/hard transition during outburst decline, which means that a source can be in either hard or soft state at a certain luminosity. This so-called hysteresis was first found by Miyamoto (1995) in observations of GX 339-4. The luminosity difference between the two transitions is about a factor of 3-5. Theoretically this hysteresis could be understood as caused by the different type of irradiation of the corona during hard and soft spectral states (Meyer-Hofmeister et al. 2005). Hardness-intensity diagrams (HID), now deduced for a number of sources, show this hysteresis clearly, together with other features such as the times at which quasi-periodic oscillations (QPO) and a jet and radio emission appeared.

Observations seem to indicate that the luminosity at which the hard/soft spectral transition occurs can differ, either from source to source (a comparison is difficult unless the luminosities are scaled to the Eddington luminosity) or even for the same source from outburst to outburst, as in the black hole transient GX 339-4. Observations are discussed by Dunn et al. (2008); hardness-intensity diagrams of four outbursts clearly show the transition at varying luminosity. Hard/soft state transitions of GX 339-4 were also investigated by Belloni et al. (2006); Nowak (2006), Caballero-Garcìa et al. (2009) and Del Santo et al. (2009). Why the hard/soft transitions for black hole sources and possibly also for neutron star transients can occur at different luminosity is still an open question.

Already from RXTE observations some evidence was found for soft components in the low/hard state for a number of sources. Recently XMM-Newton observations clearly revealed the presence of disk material very close to the innermost circular orbit in GX 339-4 and SWIFT J1753.5-0127 (Miller et al. 2006a,b). It is the aim of our paper to investigate whether an inner cool disk underneath the ADAF existing during the hard spectral state can affect the state transition. In Sects. 2 and 3 we briefly describe the phenomena of disk truncation, formation of a gap and a leftover weak inner disk. We summarize the observational evidence for an inner disk in Table 1. In Sect. 4 we discuss hard and soft irradiation of the corona by the ADAF and the inner disk. The hard irradiation of the corona is reduced if part of the matter accretes via the inner disk instead of via the ADAF. The inner disk causes further changes, e.g. less hard irradiation due to occultation of the ADAF and reflection. This results is a spectral state transition at lower luminosity than in the case of no inner disk (Sect. 5). In Sect. 6 we compare with observational evidence in different sources. In Sect. 7 we consider the hardness-intensity diagram (HID) of GX 339-4. A discussion and conclusions follow.

2 Disk truncation

2.1 Disk truncation during the low luminosity state

For our investigation of the influence of an inner disk on the spectral state transition, the accretion history of a transient source, especially truncation of the disk and the formation of a gap between outer and inner disk, is essential.

ASM aboard RXTE has provided a continuous,

seven-year record of the activity of many galactic sources. In the

review of McClintock & Remillard (2006), light curves of black hole

binaries, or black hole candidate binaries, are shown together with the

changes of the hardness ratio defined as the ratio HR2 of counts in

the 5-12 keV and the 3-5 keV range. The outbursts typically begin with

and end in

the low/hard state when the disk is truncated (for GS/GRS 1124-68 and

XTE J1550-564 changes of the inner edge of the disk are shown). Remillard &

McClintock (2006) review the X-ray states of 20 X-ray binaries.

Yuan & Narayan (2004, Fig. 3) present the accretion luminosity and

disk truncation radius for AGN and LMXRBs. For a low mass accretion

rate, i.e. a low luminosity below

![]() ,

the disk is truncated far

outside, at distances greater than 104 Schwarzschild radii.

,

the disk is truncated far

outside, at distances greater than 104 Schwarzschild radii.

Recent Chandra observations detected two black hole sources, XTE J1550-564 and H1743-322, at their faintest level of X-ray emission (Corbel et al. 2006; Bradley et al. 2007). As a new feature of the accretion geometry of truncated disks, for some sources the XMM-Newton spectra reveal the presence of a cool accretion disk component and a relativistic Fe K emission line (Miller et al. 2006b), see Sect. 3.1. One might ask whether these results, which show a thermal component and an ADAF coexisting in the innermost region, cast doubts on the commonly accepted truncated disk picture. However, recent theoretical work (Liu et al. 2006; Meyer et al. 2007) showed that a weak inner disk can be sustained as a consequence of gas condensation from the ADAF downward into a cool disk.

2.2 The disk truncation during the rise to an outburst and the decline

In their recent review Remillard & McClintock (2006) gave a

quantitative three-state description of active accretion. This

description mainly uses the ratio of the disk flux to total flux, the

power-law photon index ![]() ,

the continuum power in the power density spectrum and the occurrence of

quasi-periodic oscillations. This new nomenclature and the new

definitions of spectral states were intended to provide a better

ordering of spectral states.

,

the continuum power in the power density spectrum and the occurrence of

quasi-periodic oscillations. This new nomenclature and the new

definitions of spectral states were intended to provide a better

ordering of spectral states.

The sharpest point of departure from the previously used definition of states, as the authors call it (McClintock & Remillard 2006), is that luminosity is abandoned as a criterion for defining the state of the source. The hysteresis in the luminosity of state transition seems to suggest that we not use the luminosity as an important parameter. But this is only a limited luminosity interval where the bi-modality due to different irradiation from the differently structured innermost region exists (as described later). Narayan & McClintock (2008) take the mass accretion rate as the key parameter that mainly determines the spectral state of an accreting black hole.

The truncation of the geometrically thin, optically thick Shakura-Sunyaev disk at a certain distance is caused by the interaction of the corona and disk. In the model proposed (Meyer et al. 2000a) the corona is fed by matter which evaporates from the cool layers of the disk underneath. Since in the closer regions evaporation is very efficient, for low accretion rates all matter is transferred to the corona (at the distance where accretion rate equals the evaporation rate). The gas proceeds towards the black hole as a purely coronal vertically extended flow. While in quiescence in LMXBs the disk is truncated, during the rise to an outburst the increasing mass flow rate in the disk, in most cases, becomes larger than the maximal evaporation rate, so that the disk is not truncated anymore. Then, within the diffusion time, which is short, of the order of hours to days for different distances, the inner disk region is filled with an accretion disk and the spectrum becomes soft.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm,clip]{13044fg1.eps}

\vspace*{-3mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/46/aa13044-09/Timg21.png)

|

Figure 1:

Geometry of the accretion flow as a function

of the mass accretion rate scaled to the Eddington rate |

| Open with DEXTER | |

The reverse process happens when during the decline from an

outburst the accretion rate decreases (Meyer et al. 2007).

Figure 1 describes this process: in state (1) the disk

reaches inward for high accretion rates; state (2) is reached if the accretion

rate becomes lower than

the maximal evaporation rate

![]() ,

which is a critical value for the

accretion geometry; a gap in the disk appears at that

distance that will be filled with an ADAF; state (3): with further

decrease of the accretion rate the gap widens and

the spectrum becomes hard; n state (4) the inner disk remains as long as

re-condensation of matter from the

ADAF allows (see Sect. 3.2). We investigate

whether this leftover inner disk affects the hard/soft spectral state

transition.

,

which is a critical value for the

accretion geometry; a gap in the disk appears at that

distance that will be filled with an ADAF; state (3): with further

decrease of the accretion rate the gap widens and

the spectrum becomes hard; n state (4) the inner disk remains as long as

re-condensation of matter from the

ADAF allows (see Sect. 3.2). We investigate

whether this leftover inner disk affects the hard/soft spectral state

transition.

3 An inner cool disk during the hard state?

3.1 Observations

Table 1: Observations: inner disks in the low/hard state.

For several sources, the presence of an inner disk during the low/hard state, mostly in its brightest phases (Tomsick et al. 2008), seems indicated. Evidence was already found from RXTE observations and XMM-Newton spectra now allow us to search for a soft component at very low luminosity. However there are still few observations where both the presence of an inner disk is indicated and also the luminosity at a subsequent hard/soft transition (the specific topic of our analysis) is known. But the presence of an inner disk in a number of sources shows that the spectral transition might often be affected. In Table 1 we summarize observations that show a soft component during the low/hard spectral state, indicating the presence of a weak accretion disk close to the last stable orbit, surrounded by a more spherically extended ADAF. In the following we give more detailed information on the listed sources. The estimates for the luminosity of the soft component lie in a wide range from a few percent of the Eddington luminosity down to almost a factor of 1000 lower.

Interesting results were found especially for GRS 339-4 by Miller et al. (2006b), Reis et al. (2008) and Tomsick et al. (2008). Soft components were also clearly revealed for SWIFT J1753.5-012 by Miller et al. (2006a) (however, see also a critical discussion by Hiemstra et al. 2009) and for XTE J1817-330 by Rykoff et al. (2007).

Some

evidence for a soft component was also found for XTE J1118+480 in April

2000, shortly after the discovery of the source when its luminosity was

near 0.001

![]() (McClintock et al. 2001),

confirmed in recent work (Reis et al. 2009).

For GRO J1655-40 the evidence is small, but significant. V4641 SGR

appears to have an inner disk during the rise to the otherwise

untypical outburst 1999 (Miller et al. 2002c). For 4U 1543-475 indications of an inner

disk were found in the decline from the 2002 outburst during the hard intermediate state (Park et al. 2004) and during the hard/low state (Kalemci 2005; La Palombara & Mereghetti 2005). For XTE J1650-500 an XMM-Newton

observation early in the 2001 outburst showed indications of an inner

disk; the spectral state was first classified as ``very high'' (Miller

et al. 2002a), later as low/hard (Rossi et al. 2005; Miller et al. 2009). During the late outburst decline of the source at luminosity levels of

(McClintock et al. 2001),

confirmed in recent work (Reis et al. 2009).

For GRO J1655-40 the evidence is small, but significant. V4641 SGR

appears to have an inner disk during the rise to the otherwise

untypical outburst 1999 (Miller et al. 2002c). For 4U 1543-475 indications of an inner

disk were found in the decline from the 2002 outburst during the hard intermediate state (Park et al. 2004) and during the hard/low state (Kalemci 2005; La Palombara & Mereghetti 2005). For XTE J1650-500 an XMM-Newton

observation early in the 2001 outburst showed indications of an inner

disk; the spectral state was first classified as ``very high'' (Miller

et al. 2002a), later as low/hard (Rossi et al. 2005; Miller et al. 2009). During the late outburst decline of the source at luminosity levels of

![]() ,

Tomsick et al. (2004) did not find indications for an inner disk.

,

Tomsick et al. (2004) did not find indications for an inner disk.

Such thermal components in the spectra were found for both outburst rise and/or decline. For our investigation, it is of special interest whether during the rise to an outburst an inner disk is indicated. This would mean that such a disk had not disappeared completely since the last outburst.

Cygnus X-1 is a special case as the system is persistently active with only very moderate luminosity changes and it might have an inner disk close to the innermost stable orbit during bright phases of the low-hard state (Miller et al. 2002b). Two other systems, GRS 1758-258 and 1E 1740.7-2942, also have only small luminosity variations in a hard spectral state, but show abrupt transitions to a lower luminosity, a dim soft state (Pottschmidt et al. 2006; del Santo et al. 2005). The cool disk emission in these low flux phases seems to be of a different nature.

In addition, inner disks might be present in SAX J1711.6-3808 and XTE J1908+094 (in 't Zand et al. 2002a,b), where iron lines indicate an inner disk, but a disk continuum is not visible, possibly due to high line of sight absorption which could easily hide a cool disk (Miller et al. 2006b). These sources are strong black hole candidates.

For several of the sources listed in Table 1, further information can be found in the work of Miller et al. (2009) on black hole spin parameters.

Exploring the presence of a soft component during the hard spectral

state at very low accretion rates requires long observations.

For some systems in

quiescence at very low luminosity,

![]() ,

high

quality spectra did not show evidence of a thermal component or iron

line features, e.g. Bradley et al. (2007) for V404 Cyg, Corbel et

al. (2006) for XTE 1550 and H1743-32.

,

high

quality spectra did not show evidence of a thermal component or iron

line features, e.g. Bradley et al. (2007) for V404 Cyg, Corbel et

al. (2006) for XTE 1550 and H1743-32.

3.2 Theoretical interpretation

So far, detections and non-detections point to the existence of an inner disk, in some sources, and during limited time intervals of the outburst cycles. What determines whether an inner disk can be present? As recently found, matter can recondense from the ADAF to an underlying inner disk (Liu et al. 2006; Meyer et al. 2007) and therefore sustain an inner disk in the equatorial plane, left over from the last soft state (without re-condensation, the disk would disappear within the diffusion time of a few days). The re-condensation model was applied to GX 339-4 and SWIFT J1753.5-0127 (Liu et al. 2007).

A recent detailed analysis of the observations of

GX 339-4 (Taam et al. 2008) took into account conductive cooling of the

coronal gas and Compton cooling to evaluate

the temperature of the thermal component at the observed

luminosities. The result of these investigations

is that generally an inner disk can exist for

luminosities in the range of about 0.001 to 0.02

![]() .

Such inner disks are weak and usually have a small extension,

from almost the last stable orbit outward to a distance depending on

the mass flow rate in the ADAF, e.g. to around 100

.

Such inner disks are weak and usually have a small extension,

from almost the last stable orbit outward to a distance depending on

the mass flow rate in the ADAF, e.g. to around 100 ![]() as found in the

analysis of the observations for GX 339-4 (Taam et al. 2008). Between

the inner disk and the outer truncated disk is a gap, an ADAF fills

the region between the truncation of the outer disk and the center, and

surrounds the inner disk (see Fig. 1).

Since the inner disk can exist for a long time during the low

hard state, as long as the mass accretion rate does not become very

low, an inner disk is expected whenever a source does not become very

faint in quiescence (e.g. indicated for GX 339-4 2004, and GRO

J1655). This means, that not only the mass flow rate at a

certain time during the outburst cycle determines the accretion flow

geometry, it also depends on the mass flow history as to whether an inner

disk can be left over. Usually there are not enough observations

during quiescence to know how low the accretion rate became.

as found in the

analysis of the observations for GX 339-4 (Taam et al. 2008). Between

the inner disk and the outer truncated disk is a gap, an ADAF fills

the region between the truncation of the outer disk and the center, and

surrounds the inner disk (see Fig. 1).

Since the inner disk can exist for a long time during the low

hard state, as long as the mass accretion rate does not become very

low, an inner disk is expected whenever a source does not become very

faint in quiescence (e.g. indicated for GX 339-4 2004, and GRO

J1655). This means, that not only the mass flow rate at a

certain time during the outburst cycle determines the accretion flow

geometry, it also depends on the mass flow history as to whether an inner

disk can be left over. Usually there are not enough observations

during quiescence to know how low the accretion rate became.

4 An inner disk below the ADAF

4.1 The vertical structure of the corona

At low luminosities the process of accretion in LMXRBs includes an inner ADAF region and an outer, geometrically thin optically thick disk. At the innermost region, within a certain distance the cool disk and the corona/ADAF exist together. The interaction can go in two ways, depending on the distance from the center (this is related to whether radiative loss or advective cooling dominates, Meyer et al. 2000a). Outside a critical distance the interaction causes evaporation of gas from the disk into the hot flow, and interior gas from the ADAF condenses into a disk. Evaporation and condensation are affected by irradiation from the central region.

The vertical structure of the irradiated corona has to be evaluated to find the maximal evaporation rate. In the inner region, the flow accretes partially via an inner ADAF and partially via an inner disk. In this analysis, the irradiation from the central ADAF and the additional irradiation/Compton cooling from the inner disk are taken into account.

4.2 Compton heating/cooling due to an inner disk

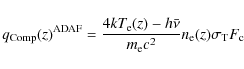

During the hard spectral state, irradiation of the

corona originates from different sources: (1) hard radiation from the hot ADAF

filling the inner region; (2) soft radiation from the

truncated disk underneath; and (3) if an inner cool disk exists, additional soft

radiation from this (usually weak) inner disk. The Compton heating/cooling rate per unit volume caused by the hard

radiation from the inner region filled with hot gas of the ADAF is

with k the Boltzmann constant,

with R the distance from the center and

If a (weak) inner disk is present, due to re-condensation of gas from

the corona to the disk, a further contribution to the Compton

cooling/heating process comes from the interaction of photons of this

inner disk with the electrons in the corona.

with

with

In Eq. (3) the term

![]() can be neglected

since there

can be neglected

since there

![]() .

Note that the presence of the inner

disk also means that simultaneously the flux through the corona is

reduced since part of the coronal flow condenses and accretes through the disk.

.

Note that the presence of the inner

disk also means that simultaneously the flux through the corona is

reduced since part of the coronal flow condenses and accretes through the disk.

5 Computational results

5.1 The effect of irradiation

We use the computer code described in Liu et al. (2002) including modifications to the energy flow (Meyer-Hofmeister & Meyer 2003) and

different components for the Compton process (Meyer-Hofmeister et al. 2005), and an additional component from the inner cool disk. We calculated the coronal structure for a

6 ![]() black hole, a mean photon energy

black hole, a mean photon energy

![]() keV for the

radiation from the inner ADAF, and a standard

keV for the

radiation from the inner ADAF, and a standard ![]() value of 0.3 for the viscosity.

The evaporation rate varies with the distance from the center, and a

series of calculations for different distances is needed to find the

maximum value of evaporation.

value of 0.3 for the viscosity.

The evaporation rate varies with the distance from the center, and a

series of calculations for different distances is needed to find the

maximum value of evaporation.

We investigate the influence of heating and cooling of the outer disk

corona by Compton scattering of the additional soft radiation from an

inner disk and the influence of a corresponding reduction of hard

irradiation from the ADAF (with a then reduced mass flow rate).

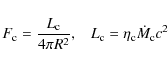

For the distance where the evaporation rate attains its maximum, Compton scattering produces heating (

![]() ), close to the

equatorial plane, and cooling at larger height z. This is caused by

the rising electron temperature. This is illustrated in

Fig. 2, which shows

), close to the

equatorial plane, and cooling at larger height z. This is caused by

the rising electron temperature. This is illustrated in

Fig. 2, which shows

![]() for the ``standard

case'' for which all matter flows via an ADAF to the center.

The change from heating to cooling

occurs where

for the ``standard

case'' for which all matter flows via an ADAF to the center.

The change from heating to cooling

occurs where

![]() equals

equals

![]() ,

in our example at low

vertical height, z/R= 0.17. In addition we show how

much an inner disk with a mass flow rate of about 25% of the total

would contribute. Simultaneously, the ADAF mass flow rate and its

contribution would then be reduced to 75%, also shown in the figure.

The consequence of a reduced ADAF irradiation for the evaporation

efficiency was already discussed by Liu et al. (2005).

,

in our example at low

vertical height, z/R= 0.17. In addition we show how

much an inner disk with a mass flow rate of about 25% of the total

would contribute. Simultaneously, the ADAF mass flow rate and its

contribution would then be reduced to 75%, also shown in the figure.

The consequence of a reduced ADAF irradiation for the evaporation

efficiency was already discussed by Liu et al. (2005).

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.cm]{13044fg2.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/46/aa13044-09/Timg59.png)

|

Figure 2:

Distribution of Compton heating (

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

The effect of irradiation on evaporation also depends on the other contributions to the energy balance such as gains by friction and vertical advective flow and losses by vertical heat flow, side wise advective outflow and radiation (for a display see Meyer et al. 2000a). The hard radiation from the inner ADAF irradiates the lower coronal layers above the outer disk. Generally additional heating at low heights tends to support evaporation and raises the maximal evaporation rate. To prevent a truncation of the outer disk by complete evaporation, a higher mass flow rate is then required. This shifts the transition from the low/hard state to the high/soft state to a higher mass accretion rate and thus a higher luminosity. Vice versa, a reduction of hard irradiation leads to a lower transition luminosity.

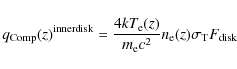

Figure 3 shows the maximum of the coronal evaporation rate as

a function of the strength of irradiation from the ADAF. The maximum

determines the transition. In the

standard case of 100% mass flow in the ADAF the evaporation maximum

is 0.029

![]() .

As the hard irradiation is decreased, the

maximal evaporation rate also decreases. The evaporation rate also

depends on the mean photon energy of the radiation. For a lower

.

As the hard irradiation is decreased, the

maximal evaporation rate also decreases. The evaporation rate also

depends on the mean photon energy of the radiation. For a lower

![]() the maximum evaporation rate is lower, but the dependence on

the strength of the hard irradiation remains similar. Simultaneous

X-ray and

the maximum evaporation rate is lower, but the dependence on

the strength of the hard irradiation remains similar. Simultaneous

X-ray and ![]() -ray observations of Cygnus X-1 in

the hard state by Ginga and OSSE indicate that in this case

the mean photon energy is about

-ray observations of Cygnus X-1 in

the hard state by Ginga and OSSE indicate that in this case

the mean photon energy is about ![]() 100 keV (Gierlinski et al. 1997).

100 keV (Gierlinski et al. 1997).

By how much is the hard irradiation decreased? The reduction follows from two different facts. Firstly it is caused by accretion via the inner disk instead of the ADAF, secondly by occultation, discussed in the following paragraph. Since at present the re-condensation rate into an inner disk has only been evaluated for low mass flow rates in the ADAF, we do not know whether the mass flow via an inner disk can be as high as 50% of the total accretion rate, suggesting an intermediate state. If a weak inner disk survived during the quiescent state and the mass accretion rate increases during the rise to the next outburst, the mass flow in the inner disk increases and the disk becomes larger in extent. At the same time, the inner edge of the outer truncated disk moves inward. The shrinking gap between the outer and inner disk might finally be filled via re-condensation or/and inward diffusion of matter from the outer disk when the critical accretion rate is reached.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm]{13044fg3.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/46/aa13044-09/Timg64.png)

|

Figure 3:

Critical accretion rate

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

5.2 Occultation and reflection

The direct hard irradiation is further reduced since an inner

disk can occult a part of the ADAF-filled region. Occultation depends

on the inclination under which the disk appears to a particular

coronal region. The regions relevant for coronal evaporation lie at

low heights, the inclination under which these layers see an inner

disk is generally high, tending to reduce occultation. On the other

hand a larger inner disk leads to more occultation, in the

limit to 50%. For example, for an observer at height z above the

mid plane and at a distance of

![]() ,

the lower hemisphere

of a spherical optically thin central source of radiation of radius

,

the lower hemisphere

of a spherical optically thin central source of radiation of radius

![]() ,

is already fully covered (50% obscuration) by an

inner disk of radius

,

is already fully covered (50% obscuration) by an

inner disk of radius

![]() for

z/R > 0.198, and by an inner

disk of radius

for

z/R > 0.198, and by an inner

disk of radius

![]() for

z/R >0.054 (this neglects a small ``look

through'' part of order

for

z/R >0.054 (this neglects a small ``look

through'' part of order

![]() seen through an

inner disk hole of radius 3

seen through an

inner disk hole of radius 3 ![]() ). Modeling observations of

GX 339-4 by Miller et al. (2006b) Taam et al. (2008) obtained an inner disk extension of about 100

). Modeling observations of

GX 339-4 by Miller et al. (2006b) Taam et al. (2008) obtained an inner disk extension of about 100 ![]() .

The reduction of hard irradiation by occultation adds to the reduction

caused by letting part of the mass flow via the inner disk instead of

via the ADAF.

.

The reduction of hard irradiation by occultation adds to the reduction

caused by letting part of the mass flow via the inner disk instead of

via the ADAF.

Part of the hard radiation from the ADAF is Compton scattered at the disk surface. Thus the back-scattered radiation is reduced in energy flux and mean photon energy (Lightman & White 1988). For a 100 keV mean photon energy one might have a change to 80 keV for the reflected radiation. If the inner disk is more extended, its temperature drops below about 106 K and absorption of the lower energy photons by the metals becomes important. This will reduce the soft part in the reflected radiation and tends to increase its mean photon energy, but at the same time reduces its total flux. Since only a small amount of reflected radiation from the inner disk reaches the outer lower corona due to the large inclination, the change of the mean photon energy of irradiation flux caused by reflection is relatively small. Thus, the reflection leads only to a small decrease of transition luminosity, though the evaporation rate depends sensitively on the mean hardness. Figure 3 shows how the critical luminosity at transition (mass flow rate) changes with a reduction of the hard irradiation. As discussed, the two ways of reduction might add up to 50%. Together with the effect of reflection, the hard/soft transition luminosity may decrease by about a factor of two.

Note that the hard state luminosity seen by an observer is affected by

the presence of an inner disk, as the contribution of the reflected

component is strongly inclination dependent (Esin et al. 1997),

larger for a lower inclination.

The inclination of GX 339-4 is not known.

Cowley et al. (2002) suggested that the small emission-line velocity

amplitudes point to a low orbital inclination. From model fits with

Compton reflection, Zdziarski et al. (1998) derived an inclination of

![]() ,

Tomsick et al. (2008) argued for an inclination

around

,

Tomsick et al. (2008) argued for an inclination

around ![]() .

These values depend on the fits. The dependence on

inclination adds further difficulties to the comparison of the transition

luminosity of different sources.

.

These values depend on the fits. The dependence on

inclination adds further difficulties to the comparison of the transition

luminosity of different sources.

6 Comparison with observations

To compare the luminosities at the hard/soft spectral transition

observed for different sources, one needs to determine

![]() .

To derive this quantity, the distance of the

source, the mass of the black hole, the absorbing column density

towards the source, as well as the instrument response for an

individual observation have to be known, in addition to the (model

dependent) bolometric flux integrated over all energies (for a

discussion see Done & Gierlinski 2003). Therefore, observations of

different outbursts of the same source, as available for GX

339-4, are very valuable.

.

To derive this quantity, the distance of the

source, the mass of the black hole, the absorbing column density

towards the source, as well as the instrument response for an

individual observation have to be known, in addition to the (model

dependent) bolometric flux integrated over all energies (for a

discussion see Done & Gierlinski 2003). Therefore, observations of

different outbursts of the same source, as available for GX

339-4, are very valuable.

For GX 339-4 the hard/soft transition during the 1998 and the 2002 outburst

seemed to occur at different luminosities, a factor of three higher

in the latter one than in the former

(Zdziarski et al. 2004). But the observations during the rise in 1998

were scarce. Using their model fits to evaluate the bolometric

luminosity (for a black hole mass 10 ![]() and a distance of 8 kpc) the authors found transition luminosities of 0.07

and a distance of 8 kpc) the authors found transition luminosities of 0.07

![]() for the hard/soft and 0.025

for the hard/soft and 0.025

![]() for the soft/hard transitions.

Done & Gierlinski (2003) show in their Fig. 2 the hard/soft transition

at about 0.04

for the soft/hard transitions.

Done & Gierlinski (2003) show in their Fig. 2 the hard/soft transition

at about 0.04

![]() by adopting a black hole mass of

6

by adopting a black hole mass of

6 ![]() and a distance of 4 kpc. The difference is mainly due to the

different black hole mass and distance assumed.

and a distance of 4 kpc. The difference is mainly due to the

different black hole mass and distance assumed.

In the detailed investigation of Dunn et al. (2008), four outbursts are considered, in 1998, 2002, 2004 and 2007. Comparing the two best sampled outbursts in 2002 and 2004 it is clear that the hard/soft transition in 2004 occurs at an intensity three to four times lower than that in 2002. During the 2007 outburst the transition is similar to that in 2002. On the other hand, the transitions during decline back to the hard state were very similar in the outbursts of 2002/2003 and 2004. From the summed spectra (Dunn et al. 2008, Fig. 5) no conclusion on a hardness change due to an inner disk in 2004 is possible. Further investigations of GX 339-4 included an analysis of the RXTE and INTEGRAL high-energy observations of a hard/soft transition in 2004 by Belloni et al. (2006), as well as RXTE and INTEGRAL observations of the transition in 2007 by Del Santo et al. (2009) and INTEGRAL and XMM-Newton observations for the same transition by Caballiero-García et al. (2009).

Now XMM-Newton spectra clearly revealed a cool accretion disk component for GX 339-4 during the rise to the outburst in 2004 (Miller et al. 2006b; Reis et al. 2008). This was the rise to outburst where the transition occurred at a luminosity three times lower than during the outburst in 2002, supporting the suggestion that an inner disk affects the state transition luminosity. The effects discussed above can add up to a mass accretion rate at transition lower by a factor of 2, to be compared with the observed difference of a factor of three in luminosity. The exact value depends on the particular parameters describing the system. We note that the luminosity might depend non-linearly on the mass accretion rate.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm]{13044fg4.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/46/aa13044-09/Timg73.png)

|

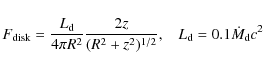

Figure 4: HID of GX 339-4: upper and middle diagram from Dunn et al. (2008, Fig. 4), outbursts in 2002 and 2004, intensity: 3-10 keV flux, hardness: flux ratio 6-10 keV/3-6 keV, long-dashed vertical lines mark state transitions. Bottom: track expected from theory, (1) rise to outburst, (2), (2a) transition to the soft state, (3), (3a) peak luminosity, (4) decline from outburst, transition to hard state. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Hard/soft transitions of Aquila X-1 were also described by Yu & Dolence (2007). In the context of our considerations it seems interesting that during a very weak outbursts in July 2001 (after maybe not too low an intensity during quiescence), a hard/soft transition occurred at a low luminosity and, a short time after this, the transition back to the hard state at the same luminosity, without hysteresis. In our theoretical picture an inner disk can survive if the mass accretion rate does not decrease too much during quiescence. This might also allow us to understand why for Cyg X-1, with luminosity changes of only a factor 3-4, no hysteresis is observed (Zdziarski et al. 2002). The inner disk probably never disappears completely. It is of interest that Miller et al. (2002b) found an inner disk during the intermediate state of Cygnus X-1 in January 2001.

7 The hardness intensity diagram

In Fig. 4, upper and middle diagram, we show hardness intensity diagrams for the 2002 and 2004 outburst of GX 339-4 from Dunn et al. (2008, Fig. 4). The hard/soft transition luminosity is clearly different, lower during the rise to outburst 2004 where the inner disk was observed (Miller et al. 2006b).

In the bottom diagram we show the diagram derived from our theoretical picture of accretion geometry. The position in the HID changes with the mass accretion rate during the outburst cycle. For the rise to outburst (low accretion rate, state (1) in Fig. 4) the outer disk is truncated and the inner region filled by an ADAF. We expect a hard spectrum determined by the ADAF near the center. During the rise to higher luminosity and increasing intensity, the hardness is almost constant. This branch in the HID always has a similar appearance, as occurs for other sources. When the accretion rate becomes higher than the maximal evaporation rate, the ADAF in the inner region is replaced by a disk (state (2)). This is usually a rapid change, with only little increase in intensity, resulting in a horizontal movement to small hardness values in the HID (the hardness changes in the HID can be estimated from the color-color diagrams in the investigation of Done & Gierlinski 2003). At what intensity the hard/soft transition occurs depends, as we show here, on the presence of an inner disk.

As soon as the outer disk reaches inward to the last stable orbit, the spectrum is soft; during the further run of the outburst, mainly the intensity changes until a peak value (state (3) or (3a)) is reached. Small variations of hardness, variations of the 6-10 keV flux, might result from more or less mass flow in a weak corona. Depending on the increase and decrease of the luminosity, the path in the HID might appear somewhat irregular, different from outburst to outburst. We therefore describe this episode with dashed lines in the theoretical HID.

After the soft state, the return to the hard state occurs when the mass accretion rate decreases below a critical value (state (4)). Note that during the soft state the coronal structure and the evaporation are affected by soft irradiation from the disk reaching inward to the last stable orbit. This is different from the hard irradiation from the inner ADAF during the rise to outburst. The different irradiation causes the well-known hysteresis in the transition luminosity (Meyer-Hofmeister et al. 2005).

The track in the HID is basically the same for all outbursts although a few special features during the outburst can change its appearance. (1) In outbursts where the luminosity increases to values much higher than at the hard/soft state transition, these data appear high up in the left upper area of the HID. (2) In some outbursts the soft state is not reached, and sometimes only an intermediate spectral state is reached, as discussed by Brocksopp et al. (2004). Well known examples are V404 Cyg (Oosterbroek et al. 1997), XTE J1118+480 (Remillard et al. 2000; Hynes et al. 2000; Revnivtsev et al. 2000) and XTE1550-564 (Sturner & Shrader 2005). Very recently a so-called ``failed outburst'' was observed for H 17432-322 (Capitanio et al. 2009), there the parts of the HID related to soft spectra are not reached during the outburst. Such behavior can be understood as related to accumulation of only small amounts of mass, which preferably happens in binaries with short orbital periods, that is, a small accretion disk (Meyer-Hofmeister 2004).

8 Discussion

Other effects that might play a role in the hard/soft transition luminosity are the following.

The vertical structure of the corona depends on the viscosity. We used

![]() for the viscosity parameter, supported by modeling of X-ray binary

spectra (Esin et al. 1997). A higher viscosity parameter leads to higher

evaporation efficiency and a higher transition luminosity (Liu et al. 2002;

Qiao & Liu 2009). If the same higher viscosity parameter also holds for

the transition back to the hard state that transition would also occur

at higher luminosity, which was not observed, at least for the well

studied outbursts of GX 339-4 in 2002 and 2004. Viscosity changes

could be related to changes of the magnetic flux present at the

beginning of the outburst. But such fluxes would have to change until

the decline.

for the viscosity parameter, supported by modeling of X-ray binary

spectra (Esin et al. 1997). A higher viscosity parameter leads to higher

evaporation efficiency and a higher transition luminosity (Liu et al. 2002;

Qiao & Liu 2009). If the same higher viscosity parameter also holds for

the transition back to the hard state that transition would also occur

at higher luminosity, which was not observed, at least for the well

studied outbursts of GX 339-4 in 2002 and 2004. Viscosity changes

could be related to changes of the magnetic flux present at the

beginning of the outburst. But such fluxes would have to change until

the decline.

A change of the radiation efficiency due to an increasing mass flow

via an inner disk would lead to a higher luminosity, corresponding to a

certain accretion rate at transition. The resulting luminosity would

be slightly higher than for constant ![]() .

Based on earlier

investigations, Narayan & McClintock (2008) had pointed out that there is

little difference between the two efficiencies for an ADAF or disk

accretion for mass flow rates close to spectral transition.

.

Based on earlier

investigations, Narayan & McClintock (2008) had pointed out that there is

little difference between the two efficiencies for an ADAF or disk

accretion for mass flow rates close to spectral transition.

9 Conclusions

Recent observations for GX 339-4 and J1753.5-0127 by Miller et al. (2006a,b), Tomsick et al. (2008) and Reis et al. (2008)

confirm the presence of an inner disk during the rise and decline of

outbursts. Further sources of observations also indicate a possible inner

disk. Theoretical investigation showed that these inner disks can

survive if re-condensation of matter from the ADAF allows us to sustain

the disk embedded in the ADAF. This is possible as long as the

luminosity does not drop below

![]() in

quiescence (Liu et al. 2006; Meyer et al. 2007).

in

quiescence (Liu et al. 2006; Meyer et al. 2007).

The observations for several sources seem to show that the hard/soft transition does not always occur at the same luminosity. A comparison of transition luminosities of different sources is made difficult as the values obtained depend on several parameters taken for the individual systems. Thus it is of special interest to compare the transitions for the same source, best sampled for GX 339-4. The hard/soft transition during the 2004 outburst occurred at a luminosity three times lower than that in the 2002 outburst. We investigate whether the presence of an inner disk can account for these differences. Such an inner disk was documented for the rise to the outburst in 2004.

Our investigation shows how the hard/soft spectral transition would occur at lower luminosity if an inner disk had remained from the previous outburst. The transition luminosity is affected by the reduction of hard irradiation from the ADAF seen by the corona, due to a decreased accretion via the ADAF and occultation of the innermost region by the inner disk. A secondary effect is caused by a decrease of the mean photon energy as direct and reflected radiation is mixed. It would be interesting to study a source shortly before the state transition in the rise to outburst. For very low inclination systems we would predict a decrease of the hardness in the spectrum.

AcknowledgementsWe thank Marat Gilfanov for fruitful discussions. We are grateful for information which the anonymous referee provided on additional cases of soft components in low/hard state systems which led to a significant improvement of Table 1. BFL acknowledges supports from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grants 10533050 and 10773028) and from the National Basic Research Program of China-973 Program 2009CB824800.

References

- Abramowicz, A., Chen, X., Kato, S., et al. 1995, ApJ, 438, L37 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Belloni, T., Parolin, I., Del Santo, M., et al. 2006, MNRAS, 367, 1113 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, C. K., Hynes, R. I., & Kong, A. K. H. 2007, ApJ, 667, 427 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Brocksopp, C., Bandyopadhyay R. M., & Fender, R. P. 2004, New Astron., 9, 249 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Caballero-Garcìa, M. D., Miller, J. M., Dìaz Trigo, M., et al. 2009, ApJ, 692, 1339 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Capitanio, F., Belloni, T., Del Santo, et al. 2009, MNRAS, 398, 1194 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Corbel, S.,Tomsick, J. A., & Kaaret, P. 2006, ApJ, 636, 971 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Cowley, A. P., Schmidtke, P. C., Hutchings, J. B., et al. 2002, ApJ, 123, 1741 [NASA ADS]

- Del Santo, M., Bazzano, A., Zdziarski, A. A., et al. 2005, A&A, 433, 617 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Del Santo, M. Belloni, T. M., Homan, J., et al. 2009, MNRAS, 392, 992 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Done, C., & Gierlinsli, M. 2003, MNRAS, 342, 1041 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, R. J. H., Fender, R. P., Körding, E. G., et al. 2008, MNRAS, 387, 545 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Esin, A. A. 1997, ApJ, 482, 400 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Esin, A. A., McClintock, J. E., & Narayan, R. 1997, ApJ, 489, 865 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Gierlinski, M., Zdziarski, A. A., Done, C., et al. 1997, MNRAS, 288, 958 [NASA ADS]

- Hiemstra B., Soleri, P., Mendez, M., et al. 2009, MNRAS, 394, 2080 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Hynes, R. I., Mauche, C. W., Haswell, C. A., et al. 2000, ApJ, 539, L37 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Ho, L. C. 2008, ARA&A, 46, 475 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Kalemci, E., Tomsick, J. A., Buxton, M. M., et al. 2005, ApJ, 622, 508 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- in 't Zand, J. J. M., Markwardt, C. B., Bazzano, A., et al. 2002a, A&A, 390, 597 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences]

- in 't Zand, J. J. M., Miller, J. M., Oosterbroek, T., et al. 2002b, A&A, 394, 553 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences]

- La Palombara, N., & Mereghetti, S. 2005, A&A, 430, L53 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences]

- Lightman, A. P., & White, T. R. 1988, ApJ, 335, 57 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B. F., Mineshige, S., Meyer F., et al. 2002, ApJ, 575, 117 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B. F., Meyer, F., & Meyer-Hofmeister, E. 2005, A&A, 454, L9 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B. F., Meyer, F., & Meyer-Hofmeister, E. 2006, A&A, 442, 555 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B. F., Taam, R. E., Meyer-Hofmeister, E., et al. 2007, ApJ, 671, 695 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- McClintock, J. E., & Remillard, R. A. 2006, in Compact Stellar X-ray Sources, ed. W. H. G. Lewin, & M. van der Klis (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge Astrophys. Ser., 39), 157

- McClintock, J. E., Haswell, C. A.,Garcia, M. R., et al. 2001, ApJ, 555, 477 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, F., Liu, B. F., & Meyer-Hofmeister, E. 2000a, A&A, 361,175

- Meyer, F., Liu, B. F., & Meyer-Hofmeister, E. 2000b, A&A, 354, L67 [NASA ADS]

- Meyer, F., Liu, B. F., & Meyer-Hofmeister, E. 2007, A&A, 463, 1 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences]

- Meyer-Hofmeister, E. 2004, A&A, 423, 321 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences]

- Meyer-Hofmeister, E., & Meyer, F. 2003, A&A, 402, 1013 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences]

- Meyer-Hofmeister, E., Liu, B. F., & Meyer, F. 2005, A&A, 432, 181 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences]

- Miller, J. M. 2007, ARA&A, 45, 441 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J. M., Fabian, A. C., Wijnands, R., et al. 2002a, ApJ, 570, L69 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J. M., Fabian, A. C., Wijnands, R., et al. 2002b, ApJ, 578, 348 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J. M., Fabian, A. C., in 't Zand, J. J. M., et al. 2002c, ApJ, 577, L15 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J. M., Homan, J., & Miniutti, G. 2006a, ApJ, 652, L113 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J. M., Homan, J., Steeghs, D., et al. 2006b, ApJ, 653, 525 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J. M., Reynolds, C. S., Fabian, A. C., et al. 2009, ApJ, 697, 900 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, S., Kitamoto, S. Hayashida, K., et al. 1995, ApJ, 442, L13 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, R., & McClintock, J. E. 2008, New Astron. Rev., 51, 733 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, R., & Yi, I. 1994, ApJ, 428, L13 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, R., & Yi, I. 1995a, ApJ, 444, 231 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, R., & Yi, I. 1995b, ApJ, 452, 710 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, R., Yi, I., & Mahadevan, R. 1995, Nature, 374, 623 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, R., McClintock, J. E., & Yi, I. 1996, ApJ, 457, 821 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, R., Barret, D., & McClintock, J. E. 1997, ApJ, 482, 448 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, R., Mahadevan, R., & Quataert, E. 1998, in The Theory of Black Hole Accretion Discs, ed. M. A. Abramowicz et al. (Cambridge Univ. Press), 48

- Nowak, A. M. 2006 [arXiv:astro-ph/0611909]

- Oosterbroek, T., van der Klis, M., van Paradijs, J., et al. 1997, A&A, 321, 776 [NASA ADS]

- Park, S. Q., Miller, J. M., McClintock, J. E., et al. 2004, ApJ, 610, 378 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Pottschmidt, K., Chernyakova, M., Zdziarski, A. A., et al. 2006, A&A, 452, 285 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences]

- Qiao, E., & Liu, B. F. 2009, PASJ 61, 403

- Reig, P., van Straaten, S., & van der Klis, M. 2004, ApJ, 602, 918 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Reis, R. C., Fabian, A. C., Ross, R., et al. 2008, MNRAS, 392, 992

- Reis, R. C., Miller, J. M., & Fabian, A. C. 2009, MNRAS, 395, L52 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Remillard, R. A., & McClintock, J. E. 2006, ARA&A, 44, 49 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Remillard, R. A., Morgan, E. Smith, D., et al. 2000, IAU Circ., 7389

- Revnivtsev, M. G., Sunyaev, R., & Borozdin, K. 2000, A&A, 361, L37 [NASA ADS]

- Rossi, S., Homan, J., Miller, J. M., et al. 2005, MNRAS, 360, 763 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Rykoff, E. S., Miller, J. M., Steeghs, D., et al. 2007, ApJ, 666, 1129 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Sturner, S. J., & Shrader, C. R. 2005, ApJ, 625, 923 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Taam, R. E., Liu, B. F., Meyer, F., et al. 2008 ApJ, 688, 527

- Tomsick, J. A., Kalemci, E., & Kaaret, P. 2004, ApJ, 601, 439 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Tomsick, J. A., Kalemci, E., Kaaret, P., et al. 2008, ApJ, 680, 593 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W., & Dolence, J. 2007, ApJ, 667, 1043 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F. 2007, ASP Conf. Ser., 373, 95 [NASA ADS]

- Yuan, F., & Narayan, R. 2004, ApJ, 612, 724 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Zdziarski, A. A., Poutanen, J., Mikoajewska, J., et al. 1998, MNRAS, 301, 435 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Zdziarski, A. A., Poutanen, J. Paciesas, W. S., et al. 2002, ApJ, 578, 357 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Zdziarski, A. A., Gierlinski, M., Mikoajewska, J., et al. 2004, MNRAS, 351, 791 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

All Tables

Table 1: Observations: inner disks in the low/hard state.

All Figures

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm,clip]{13044fg1.eps}

\vspace*{-3mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/46/aa13044-09/Timg21.png)

|

Figure 1:

Geometry of the accretion flow as a function

of the mass accretion rate scaled to the Eddington rate |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.cm]{13044fg2.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/46/aa13044-09/Timg59.png)

|

Figure 2:

Distribution of Compton heating (

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm]{13044fg3.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/46/aa13044-09/Timg64.png)

|

Figure 3:

Critical accretion rate

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm]{13044fg4.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/46/aa13044-09/Timg73.png)

|

Figure 4: HID of GX 339-4: upper and middle diagram from Dunn et al. (2008, Fig. 4), outbursts in 2002 and 2004, intensity: 3-10 keV flux, hardness: flux ratio 6-10 keV/3-6 keV, long-dashed vertical lines mark state transitions. Bottom: track expected from theory, (1) rise to outburst, (2), (2a) transition to the soft state, (3), (3a) peak luminosity, (4) decline from outburst, transition to hard state. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

Copyright ESO 2009

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.