| Issue |

A&A

Volume 507, Number 2, November IV 2009

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Page(s) | 781 - 793 | |

| Section | Extragalactic astronomy | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/200912730 | |

| Published online | 01 October 2009 | |

A&A 507, 781-793 (2009)

Low redshift AGN in the Hamburg/ESO survey

I. The local AGN luminosity

function![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

A. Schulze - L. Wisotzki - B. Husemann

Astrophysikalisches Institut Potsdam, An der Sternwarte 16, 14482 Potsdam, Germany

Received 19 June 2009 / Accepted 17 September 2009

Abstract

We present a determination of the local (![]() )

luminosity function of optically selected type 1 (broad-line)

active galactic nuclei. Our primary resource is the Hamburg/ESO

survey (HES), which provides a well-defined sample of more

than 300 optically bright AGN with redshifts z<0.3

and blue magnitudes

)

luminosity function of optically selected type 1 (broad-line)

active galactic nuclei. Our primary resource is the Hamburg/ESO

survey (HES), which provides a well-defined sample of more

than 300 optically bright AGN with redshifts z<0.3

and blue magnitudes ![]() .

AGN luminosities were estimated in two ways, always taking care to

minimise photometric biases due to host galaxy light contamination.

Firstly, we measured broad-band BJ

(blue) magnitudes of the objects over small apertures of the size of

the seeing disk. Secondly, we extracted H

.

AGN luminosities were estimated in two ways, always taking care to

minimise photometric biases due to host galaxy light contamination.

Firstly, we measured broad-band BJ

(blue) magnitudes of the objects over small apertures of the size of

the seeing disk. Secondly, we extracted H![]() and H

and H![]() broad emission line luminosities from the spectra which should be

entirely free of any starlight contribution. Within the luminosity

range covered by the HES (

broad emission line luminosities from the spectra which should be

entirely free of any starlight contribution. Within the luminosity

range covered by the HES (

![]() ),

the two measures are tightly correlated. The resulting AGN luminosity

function (AGNLF) is consistent with a single power law, also when

considering the effects of number density evolution within the narrow

redshift range. We compared our AGNLF with the H

),

the two measures are tightly correlated. The resulting AGN luminosity

function (AGNLF) is consistent with a single power law, also when

considering the effects of number density evolution within the narrow

redshift range. We compared our AGNLF with the H![]() luminosity function of lower luminosity Seyfert 1 galaxies by

Hao et al. (2005a, AJ, 129, 1795) and found a smooth transition between

both, with excellent agreement in the overlapping region. From the

combination of HES and SDSS samples we constructed a single local AGNLF

spanning more than 4 orders of magnitude in luminosity. It

shows only mild curvature which can be well described as a double power

law with slope indices of -2.0 for the faint end and -2.8 for the

bright end. We predicted the local AGNLF in the soft X-ray domain and

compared this to recent literature data. The quality of the match

depends strongly on the adopted translation of optical to X-ray

luminosities and is best for an approximately constant optical/X-ray

ratio. We also compared the local AGNLF with results obtained at higher

redshifts and find strong evidence for luminosity-dependent evolution,

in the sense that AGN with luminosities around

luminosity function of lower luminosity Seyfert 1 galaxies by

Hao et al. (2005a, AJ, 129, 1795) and found a smooth transition between

both, with excellent agreement in the overlapping region. From the

combination of HES and SDSS samples we constructed a single local AGNLF

spanning more than 4 orders of magnitude in luminosity. It

shows only mild curvature which can be well described as a double power

law with slope indices of -2.0 for the faint end and -2.8 for the

bright end. We predicted the local AGNLF in the soft X-ray domain and

compared this to recent literature data. The quality of the match

depends strongly on the adopted translation of optical to X-ray

luminosities and is best for an approximately constant optical/X-ray

ratio. We also compared the local AGNLF with results obtained at higher

redshifts and find strong evidence for luminosity-dependent evolution,

in the sense that AGN with luminosities around ![]() are as common in the local universe as they were at z

= 1.5. This supports the ``AGN downsizing'' picture first found from

X-ray selected AGN samples.

are as common in the local universe as they were at z

= 1.5. This supports the ``AGN downsizing'' picture first found from

X-ray selected AGN samples.

Key words: galaxies: active - galaxies: nuclei - quasars: general

1 Introduction

A good knowledge of the AGN luminosity function (AGNLF) is important

for our understanding of the AGN population and its evolution, as well

as for gaining insight into the history of black hole growth and galaxy

evolution (e.g. Marconi

et al. 2004; Yu & Tremaine 2002).

Thanks to recent heroic quasar surveys such as the 2dF QSO Redshift

Survey (2QZ) and the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS), large

samples of AGN became available, and the optical AGN/QSO luminosity

function is today well established over a wide range in redshifts (

![]() )

and luminosities (Bongiorno

et al. 2007; Croom et al. 2009b; Boyle

et al. 2000; Richards et al. 2006;

Croom

et al. 2004). However, neither of these surveys

reaches below redshifts of

)

and luminosities (Bongiorno

et al. 2007; Croom et al. 2009b; Boyle

et al. 2000; Richards et al. 2006;

Croom

et al. 2004). However, neither of these surveys

reaches below redshifts of ![]() -0.4, because the imposed

colour selection criteria, and also the discrimination against extended

sources in the 2QZ sample, exclude a large fraction of lower

luminosity, ``Seyfert-type'' AGN. The local AGNLF

is therefore much less constrained than at higher redshifts, despite of

its importance as a zero-point for studies on the AGNLF and quasar

evolution.

-0.4, because the imposed

colour selection criteria, and also the discrimination against extended

sources in the 2QZ sample, exclude a large fraction of lower

luminosity, ``Seyfert-type'' AGN. The local AGNLF

is therefore much less constrained than at higher redshifts, despite of

its importance as a zero-point for studies on the AGNLF and quasar

evolution.

Approaching this problem from the other end, large spectroscopic galaxy surveys are a powerful way to unravel the AGN content of local galaxy samples (e.g. Huchra & Burg 1992; Ulvestad & Ho 2001; Hao et al. 2005a). When constructing an AGNLF from galaxy surveys, care has to be taken in defining ``AGN luminosity'': Simply taking the optical galaxy magnitude will lead to an ill-defined mix of host galaxy and AGN contributions. It is much better to base the AGNLF on the conspicuous broad Balmer emission lines which avoids the host galaxy contamination problem. This approach was recently adopted by Hao et al. (2005a) and Greene & Ho (2007). But since AGN are scarce among galaxies unless the selection is sensitive to very low levels of nuclear activity (Ho et al. 1997), any general galaxy survey has a low yield, and the samples are dominated by weak Seyfert nuclei and rarely reach quasar-like luminosities.

In this paper we study the population statistics of low-redshift quasars and moderately luminous Seyferts. We exploit the Hamburg/ESO Survey (HES; e.g. Wisotzki et al. 2000), a survey which was specifically designed to address the selection of low-redshift AGN with visible host galaxies, and to provide a well-defined, complete, and unbiased sample of the local AGN population. Here, the term ``complete'' is meant in a methodological sense, implying that all AGN selected by the criteria are included in the sample. Since obscured or heavily reddened AGN are typically not found in the HES, our sample can only claim to be representative of the unobscured ``type 1'' AGN with broad emission lines in their spectra. We refrain in this paper from repeatedly recalling this fact, but it should be understood that we always imply this restriction when using the term ``AGN''.

This is the third paper investigating the local AGNLF in the

HES. Koehler et al.

(1997) used a small sample of 27 objects obtained during the

initial period of the survey to construct the first published local LF

of quasars and Seyfert 1 galaxies. Wisotzki (2000b) exploited ![]() 50% of the

HES to study the evolution of the quasar luminosity function and

provided a re-determination of the local LF as a by-product. With the

completed HES covering almost 7000 deg2

of effective area, the AGN samples are doubled in size, as well as

augmented by spectroscopic material. Thus a new effort is well

justified. In the present paper we go substantially beyond our previous

work not only in quantitative, but also in qualitative terms. We first

present our data material and our treatment of the spectra. After

constructing the standard broad-band AGNLF we investigate the H

50% of the

HES to study the evolution of the quasar luminosity function and

provided a re-determination of the local LF as a by-product. With the

completed HES covering almost 7000 deg2

of effective area, the AGN samples are doubled in size, as well as

augmented by spectroscopic material. Thus a new effort is well

justified. In the present paper we go substantially beyond our previous

work not only in quantitative, but also in qualitative terms. We first

present our data material and our treatment of the spectra. After

constructing the standard broad-band AGNLF we investigate the H![]() and H

and H![]() emission line luminosity functions. This enables us to compare and

combine our data with the recent work by Hao

et al. (2005a) based on the SDSS galaxy sample, to

obtain a local AGNLF covering several orders of magnitude in

luminosities. We discuss our results in the context of other surveys

and luminosity functions.

emission line luminosity functions. This enables us to compare and

combine our data with the recent work by Hao

et al. (2005a) based on the SDSS galaxy sample, to

obtain a local AGNLF covering several orders of magnitude in

luminosities. We discuss our results in the context of other surveys

and luminosity functions.

Thoughout this paper we assume a concordance cosmology, with a

Hubble constant of H0 =

70 km s-1 Mpc-1,

and cosmological density parameters ![]() and

and ![]() (Spergel et al. 2003).

(Spergel et al. 2003).

2 Data

2.1 The Hamburg/ESO survey

The Hamburg/ESO survey (HES) is a wide-angle survey for bright

QSOs and other rare objects in the southern hemisphere, utilising

photographic objective prism plates taken with the ESO 1 m

Schmidt telescope on La Silla. Plates in

380 different fields were obtained and subsequently digitised

at Hamburg, followed by a fully automated extraction of the slitless

spectra. In total, the HES covers a formal area of ![]() 9500 deg2

in the sky. For each of the

9500 deg2

in the sky. For each of the ![]() 107

objects extracted, spectral information at 10-15 Å resolution

in the range

107

objects extracted, spectral information at 10-15 Å resolution

in the range ![]() is recorded. Details about the survey procedure are provided by Wisotzki et al. (2000).

is recorded. Details about the survey procedure are provided by Wisotzki et al. (2000).

The relatively rich information content in the HES slitless

spectra enabled us to apply a multitude of selection criteria,

depending on the object type in question. AGN can be easily recognised

from their peculiar spectral energy distributions if they contain a

sufficiently prominent nonstellar nucleus, i.e. ``type 1''

AGN. The HES picks up quasars with ![]() at redshifts of up to

at redshifts of up to ![]() .

Several precautions ensured that low-redshift, low-luminosity AGN are

not systematically missed. For example, both the extraction of spectra

and the criteria to select AGN candidates contained a special treatment

of extended sources, making the selection less sensitive to the masking

of AGN by their host galaxies. This property makes the HES unique among

optical survey in that it targets almost the entire local

(low-redshift) population of type 1 AGN, from the most

luminous quasars to relatively feeble low-luminosity Seyfert galaxies.

It is this property which we exploit in the present paper.

.

Several precautions ensured that low-redshift, low-luminosity AGN are

not systematically missed. For example, both the extraction of spectra

and the criteria to select AGN candidates contained a special treatment

of extended sources, making the selection less sensitive to the masking

of AGN by their host galaxies. This property makes the HES unique among

optical survey in that it targets almost the entire local

(low-redshift) population of type 1 AGN, from the most

luminous quasars to relatively feeble low-luminosity Seyfert galaxies.

It is this property which we exploit in the present paper.

2.2 Photometry

Photometric calibration in the HES is a two-step process. We first

measured internal isophotal broad-band BJ![]() magnitudes in the Digitized

Sky Survey (DSS) and calibrated these against external CCD

photometric sequences. At the start of the HES around 1990, only the guide

star photometric catalog (GSPC Lasker

et al. 1988) was available which typically provided

standard stars with

magnitudes in the Digitized

Sky Survey (DSS) and calibrated these against external CCD

photometric sequences. At the start of the HES around 1990, only the guide

star photometric catalog (GSPC Lasker

et al. 1988) was available which typically provided

standard stars with ![]() ,

clearly insufficient to obtain reasonably accurate photometry near

,

clearly insufficient to obtain reasonably accurate photometry near ![]() ,

the faint limit of the HES. We therefore launched a campaign to obtain

our own deeper photometric CCD sequences in as many fields as possible;

the results of this campaign will soon be made public (Schulze

et al., in preparation). Augmenting these sequences by

incorporating also the guide star photometric catalog II

(GSPC-II; Bucciarelli

et al. 2001), we arrived at a satisfactory

photometric calibration of all 380 HES fields.

,

the faint limit of the HES. We therefore launched a campaign to obtain

our own deeper photometric CCD sequences in as many fields as possible;

the results of this campaign will soon be made public (Schulze

et al., in preparation). Augmenting these sequences by

incorporating also the guide star photometric catalog II

(GSPC-II; Bucciarelli

et al. 2001), we arrived at a satisfactory

photometric calibration of all 380 HES fields.

However, these isophotal DSS magnitudes suffer from a number of drawbacks, the most undesirable one (for our purposes) being the fact that for extended objects, the nuclear AGN contribution tends to be drowned out by the host galaxy. Using isophotal magnitudes would have a detrimental effect on the estimation of a proper AGN luminosity function especially at the low-luminosity end. Other negative properties of the DSS magnitudes include the effects of relatively poor seeing in many fields, boosting the number of undesired blends.

In order to approximate the concept of nuclear magnitudes, we optimised the extraction procedure of slitless spectra in the HES digitised data to assume either true point sources or point sources embedded in a diffuse envelope. In other words, the spectra used for the HES candidate selection always refer to an area of the size of the central seeing disk only (note also that the HES spectral plates were typically obtained under much better seeing conditions than the DSS). We then measured ``nuclear magnitudes'' by integrating the spectra over the BJ passband, and calibrated these magnitudes against the DSS using hundreds of stars in each field. We demonstrate below (Sect. 4) that this procedure indeed produces measurements that in reasonably good approximation can be taken as basis for nuclear luminosities (see also Figs. 5 and 6 below).

An additional advantage of our approach lies in the fact that we thus entirely avoid variability bias: Selection criteria and fluxes in each field are all defined for a single dataset.

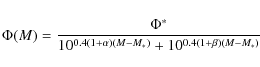

For the purpose of the present paper, a good knowledge of the survey selection function, and thus of the accurate flux limits is important. In the case of the HES, the flux limit varies considerably between individual fields, mostly due to changes in the seeing and night-sky conditions, but also because of plate quality. Thus, each field maintains its own flux limit, always corresponding to the same limiting signal to noise ratio in the slitless spectra. As long as redshift-dependent selection effects are neglected, the survey selection function is identical to the ``effective area'' of the survey, combining the 380 flux limits into single array that provides the total survey area as a function of magnitude. The effective area of the entire HES is shown in Fig. 1. Notice that this array also fully accounts for the losses due to overlapping spectra and images (see the full discussion in Wisotzki et al. 2000).

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=-90,width=8.5cm,clip]{12730f01.eps}

\vspace*{2mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/44/aa12730-09/Timg21.png)

|

Figure 1: Effective area of the Hamburg/ESO survey as a function of the Galactic extinction corrected BJ magnitude. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

All magnitudes used in this paper have been corrected for Galactic extinction, using the dust maps of (Schlegel et al. 1998, averaged over each HES field), and the extinction law of Cardelli et al. (1989). Note that for the HES we had previously followed a different extinction correction recipe based on measured column densities of Galactic neutral hydrogen converted into extinction (see Wisotzki et al. 2000). The main result of this change is a slight decrease of the average adopted extinction along most lines of sight.

Figure 1 shows that the average extinction-corrected limiting magnitude of the HES is BJ < 17.3, but with a dispersion of 0.5 mag between individual fields. There is essentially no bright limit, with 3C 273 recovered as the brightest AGN in the sample.

2.3 Spectroscopic data

All AGN and QSO candidates brighter than the flux limit in a given field were subjected to follow-up spectroscopy for confirmation and accurate redshift determination, altogether approximately 2000 targets. These observations were carried out during 23 observing campaigns between 1990 and 2000, using various telescopes and instruments at the ESO La Silla observatory. Known AGN that were recovered by the HES selection criteria were initially not part of the follow-up scheme. However, such objects were often included as backup targets, so that our spectroscopic coverage is almost complete for the entire AGN sample. For some quasars in areas overlapping with the Sloan Digital Sky Survey we could later add spectra from the public SDSS database.

Because of the diversity of telescopes used, the quality of the spectra varied significantly, in signal to noise as well as spectral resolution. We estimated the latter quantity from the width of the night sky O I emission line at 5577 Å. A list of individual observing campaigns with their estimated spectral resolution and the number of AGN from our sample observed is listed in Table 1.

Although a formal spectrophotometric calibration was available for all campaigns, the combined dataset is much too heterogeneous to allow for any consistent direct measurement of emission line fluxes. We therefore adjusted all spectra to a common, homogeneous flux scale by computing a synthetic BJ magnitude from each spectrum and matching this to the ``nuclear magnitude'' photometry of the HES. This step again also ensured that AGN variability is of no importance.

Table 1: Observing campaigns for follow-up spectroscopy.

2.4 The sample

For the present investigation of the ``local'' AGN population we

selected all AGN from the final HES catalogue (Wisotzki

et al., in prep.) that belong to the ``complete sample'' and

that are located at redshifts z < 0.3. This

sample contains 329 type-1 AGN. For 5 of them we

could not obtain spectra of sufficient quality. Thus our sample is ![]() %

complete in terms of spectroscopic coverage.

%

complete in terms of spectroscopic coverage.

The HES nuclear fluxes were converted into absolute MBJ magnitudes

using the K correction of Wisotzki (2000a).

Figure 2

shows the distribution of the sample over redshifts and absolute

magnitudes. A wide range of nuclear luminosities is covered, ranging

from bright quasars with ![]() to low-luminosity Seyfert 1 galaxies of only

to low-luminosity Seyfert 1 galaxies of only ![]() .

.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=-90,width=8.5cm,clip]{12730f02.eps}

\vspace*{2mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/44/aa12730-09/Timg26.png)

|

Figure 2: Redshift against absolute magnitude MBJ. The dashed line indicates a constant apparent magnitude of 17.5 mag, approximately the flux limit of the HES. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

3 Emission line properties

3.1 Fitting procedure

As our sample is defined by z < 0.3, all

objects have H![]() and most also have H

and most also have H![]() visible in their spectra. We measured luminosities and line widths of

the H

visible in their spectra. We measured luminosities and line widths of

the H![]() and H

and H![]() emission lines by fitting the spectral region around each line with a

multi-component Gaussian model. Over this short wavelength range we

approximated the underlying continuum as a straight line. While the

structure of the broad lines is generally complicated, it has

repeatedly been demonstrated (e.g. Hao et al. 2005b; Ho et al.

1997; Steidel

& Sargent 1991) that in many cases a double Gaussian

provides an acceptable fit to the BLR lines. We always started with a

single Gaussian per line. A second (in a few cases also a third)

component was added only if a single Gaussian yielded a poor fit and

the addition of a component significantly improved it.

At our limited spectral resolution, any possibly present narrow

component of a broad line such as H

emission lines by fitting the spectral region around each line with a

multi-component Gaussian model. Over this short wavelength range we

approximated the underlying continuum as a straight line. While the

structure of the broad lines is generally complicated, it has

repeatedly been demonstrated (e.g. Hao et al. 2005b; Ho et al.

1997; Steidel

& Sargent 1991) that in many cases a double Gaussian

provides an acceptable fit to the BLR lines. We always started with a

single Gaussian per line. A second (in a few cases also a third)

component was added only if a single Gaussian yielded a poor fit and

the addition of a component significantly improved it.

At our limited spectral resolution, any possibly present narrow

component of a broad line such as H![]() is difficult to detect. We did not include an unresolved narrow

component by default and added such a component only when it was

clearly demanded by the data.

is difficult to detect. We did not include an unresolved narrow

component by default and added such a component only when it was

clearly demanded by the data.

The Fe II emission complex

affecting the red wing of H![]() can be sufficiently approximated by a double Gaussian at wavelength

can be sufficiently approximated by a double Gaussian at wavelength ![]() 4924, 5018 Å

for our data. We fixed their positions and also fixed their intensity

ratio

4924, 5018 Å

for our data. We fixed their positions and also fixed their intensity

ratio ![]() to 1.28, typical for BLR conditions. Thus only two parameters were

allowed to vary, the amplitude and the line width. The [O III]

to 1.28, typical for BLR conditions. Thus only two parameters were

allowed to vary, the amplitude and the line width. The [O III]

![]() 4959, 5007

Å lines were also fitted by a double Gaussian with the

intensity ratio fixed to the theoretical value of 2.98 (e.g. Dimitrijevic et al. 2007).

The relative wavelengths of the doublet were fixed as well, but the

position of the doublet relative to H

4959, 5007

Å lines were also fitted by a double Gaussian with the

intensity ratio fixed to the theoretical value of 2.98 (e.g. Dimitrijevic et al. 2007).

The relative wavelengths of the doublet were fixed as well, but the

position of the doublet relative to H![]() was allowed to vary as a whole.

was allowed to vary as a whole.

For the H![]() line complex, the contributions of [N II],

and sometimes also [S II] needed to be

taken into account. The latter was mostly well separated and could be

ignored, but when required we modelled it as a double Gaussian with

fixed positions and same width for both lines. For fitting the [N II]

line complex, the contributions of [N II],

and sometimes also [S II] needed to be

taken into account. The latter was mostly well separated and could be

ignored, but when required we modelled it as a double Gaussian with

fixed positions and same width for both lines. For fitting the [N II]

![]() 6548, 6583 Å

doublet we left only the amplitude free. The positions were fixed, the

intensity ratio was set to 2.96 (Ho

et al. 1997), and the line width was fixed to the

width of the narrow [O III] lines.

6548, 6583 Å

doublet we left only the amplitude free. The positions were fixed, the

intensity ratio was set to 2.96 (Ho

et al. 1997), and the line width was fixed to the

width of the narrow [O III] lines.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{12730f03.eps}

\vspace*{2mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/44/aa12730-09/Timg29.png)

|

Figure 3:

Examples of fits to the spectra, illustrating the quality of the

spectroscopic data. The line complex of H |

| Open with DEXTER | |

With this set of constraints, each spectrum was fitted with a

multi-Gaussian plus continuum model. We decided manually which model

fits best, neglecting contributions by Fe II,

[N II] and [S II]

lines if not clearly present. In 6 objects we detected H![]() but the S/N was too low to trace H

but the S/N was too low to trace H![]() .

On the other hand, 21 of our spectra did not reach sufficiently into

the red to cover H

.

On the other hand, 21 of our spectra did not reach sufficiently into

the red to cover H![]() ;

further 8 spectra were too heavily contaminated by telluric

absorption to produce a reliable H

;

further 8 spectra were too heavily contaminated by telluric

absorption to produce a reliable H![]() fit. For these objects, H

fit. For these objects, H![]() was readily detected.

was readily detected.

Of the 324 spectra of the sample, we thus could

obtain reasonable fits for 318 objects in H![]() ,

and for 295 in H

,

and for 295 in H![]() .

Figure 3

shows some example results, illustrating the range of signal to noise

ratios and resolutions of the spectral material.

.

Figure 3

shows some example results, illustrating the range of signal to noise

ratios and resolutions of the spectral material.

3.2 Line fluxes

From the fitted model we determined the emission line fluxes of H![]() and H

and H![]() as well as the continuum flux at 5100 Å. As said above, a

narrow component of the Balmer line was only subtracted if clearly

identified in the fit. This happened in 46 cases for H

as well as the continuum flux at 5100 Å. As said above, a

narrow component of the Balmer line was only subtracted if clearly

identified in the fit. This happened in 46 cases for H![]() and in 34 instances for H

and in 34 instances for H![]() .

We also measured the line widths of H

.

We also measured the line widths of H![]() and H

and H![]() ,

which were then used to estimate the black hole masses for the sample.

These results are presented in a companion paper (Schulze &

Wisotzki, in prep.).

,

which were then used to estimate the black hole masses for the sample.

These results are presented in a companion paper (Schulze &

Wisotzki, in prep.).

In order to estimate realistic errors we constructed artificial spectra for each object, using the fitted model and Gaussian random noise corresponding to the measured S/N. We used 500 realizations for each spectrum. We fitted these artificial spectra as described above, fitting the line and the continuum and measured the line widths and the line flux. The error of these properties was then simply taken as the dispersion between the various realizations. Note that this method provides only a formal error, taking into account fitting uncertainties caused by the noise. Other sources of error may include: A residual Fe II contribution; an intrinsic deviation of the line profile from our multi-Gaussian model, as well as uncertainties in the setting of the continuum level.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=-90,width=8.5cm,clip]{12730f04.eps}

\vspace*{2mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/44/aa12730-09/Timg30.png)

|

Figure 4:

Correlation between the fluxes |

| Open with DEXTER | |

3.3 Relation between H and H

and H fluxes

fluxes

In order to investigate the distribution of AGN emission line

luminosities we focus on H![]() and H

and H![]() as the two most prominent recombination lines in our spectra. It is of

interest to look at the relation between these two lines. While recent

published work on this subject has mostly relied on H

as the two most prominent recombination lines in our spectra. It is of

interest to look at the relation between these two lines. While recent

published work on this subject has mostly relied on H![]() (Greene

& Ho 2005; Hao et al. 2005a),

extending similar studies to nonzero redshifts is easier using H

(Greene

& Ho 2005; Hao et al. 2005a),

extending similar studies to nonzero redshifts is easier using H![]() .

In Fig. 4

we plot the fluxes of the two broad lines against each other. As

expected, H

.

In Fig. 4

we plot the fluxes of the two broad lines against each other. As

expected, H![]() and H

and H![]() are strongly correlated. To quantify this, we applied a linear

regression between H

are strongly correlated. To quantify this, we applied a linear

regression between H![]() and H

and H![]() in logarithmic units, using the FITEXY method (Press

et al. 1992) which allows for errors in both

coordinates. We account for intrinsic scatter in the relation following

Tremaine et al. (2002)

by increasing the uncertainties until a

in logarithmic units, using the FITEXY method (Press

et al. 1992) which allows for errors in both

coordinates. We account for intrinsic scatter in the relation following

Tremaine et al. (2002)

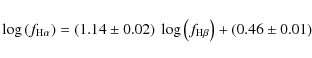

by increasing the uncertainties until a ![]() per degree of freedom of unity is obtained. The best-fit relation found

for the line fluxes is

per degree of freedom of unity is obtained. The best-fit relation found

for the line fluxes is

where the fluxes are given in 10-13 erg s-1 cm-2. The rms scatter around the best fit is 0.15 dex. The relation between H

4 AGN luminosities

A long-standing issue for the determination of the local AGN luminosity function is the problem of how to disentangle nuclear AGN and host galaxy luminosities. Using total or isophotal photometric measurements will inevitably lead to luminosity- and redshift-dependent biases. For example, the Seyfert luminosity functions determined in some earlier studies (e.g. Huchra & Burg 1992; Ulvestad & Ho 2001) clearly reflected more the distribution of host galaxy luminosities than AGN properties. Ideally, AGN and host light should be properly decomposed object by object; but as this would require high angular resolution data for all objects in a sample, such a route is presently not possible.

As a simplified approach to tackle this problem, we introduced in Sect. 2.2 our concept of ``nuclear magnitudes'' measured in the HES spectral plates. We did not subtract any host galaxy contribution, but we kept it to a minimum by measuring only the flux contribution of a nuclear point source. In Fig. 5 we compare these ``nuclear'' magnitudes with the more standard isophotal measurements in the DSS direct images. While for high-luminosity quasars (and for all quasars at higher redshifts, not shown in the figure), these two magnitudes give completely consistent results, there is an obvious discrepancy which increases towards lower luminosities. Clearly, the isophotal magnitudes are biased for almost all AGN with nuclear magnitudes fainter than -23, and useless for low-luminosity Seyfert galaxies.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=-90,width=8.5cm,clip]{12730f05.eps}

\vspace*{2mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/44/aa12730-09/Timg34.png)

|

Figure 5: Difference between ``isophotal DSS'' and ``nuclear'' magnitudes, plotted against absolute nuclear magnitude MBJ. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=-90,width=16cm,clip]{12730f06.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/44/aa12730-09/Timg36.png)

|

Figure 6:

Relation between absolute magnitudes in the BJ

band and line luminosities ( left: H |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Hence it appears that the HES magnitudes are better estimates of

nuclear luminosities than standard isophotal ones; but are they good

enough? To investigate this we now compare the HES magnitudes with the

luminosities of the broad emission lines. As H![]() and H

and H![]() are pure recombination lines, their luminosities should be proportional

to the UV continuum (e.g. Yee 1980).

In an AGN spectrum, the fluxes of the broad lines are usually

conspicuous and can be reasonably well measured even when the host

galaxy contribution is strong or dominant. We thus adopt the Balmer

emission line luminosities as proxies for the UV continuum luminosity

of the AGN, without any host contribution.

are pure recombination lines, their luminosities should be proportional

to the UV continuum (e.g. Yee 1980).

In an AGN spectrum, the fluxes of the broad lines are usually

conspicuous and can be reasonably well measured even when the host

galaxy contribution is strong or dominant. We thus adopt the Balmer

emission line luminosities as proxies for the UV continuum luminosity

of the AGN, without any host contribution.

In Fig. 6

we compare the HES broad band nuclear BJ

magnitudes with the luminosities in both Balmer lines. The correlation

is excellent and, more importantly, it extends over the entire range of

luminosities. To guide the eye, the dashed lines in Fig. 6

represent fixed-slope relations ![]() .

We see that the data come very close to a slope of unity in the case of

MBJ

vs. H

.

We see that the data come very close to a slope of unity in the case of

MBJ

vs. H![]() ,

while the relation is slightly shallower for H

,

while the relation is slightly shallower for H![]() .

.

If the HES magnitudes were systematically affected by host galaxy contributions we should expect to see a saturation of MBJ values at small L. In fact no clear such trend is visible in the data, except maybe a small excess of a few points above the linear relation in the lower left corner of the right-hand panel. If at all, these few objects appear to be the only ones significantly affected by host galaxy light when described by the HES magnitudes. Overall we conclude that the broad band photometry of the HES is, in good approximation, a measure of the pure AGN luminosities.

5 Luminosity functions

5.1 Luminosity function parameterisation

The AGN luminosity function (LF) ![]() is defined as the number of AGN per unit volume, per unit luminosity.

The number of AGN per unit volume and per unit logarithmic luminosity

is defined as the number of AGN per unit volume, per unit luminosity.

The number of AGN per unit volume and per unit logarithmic luminosity ![]() is given by

is given by ![]() ,

where

,

where ![]() is the cumulative luminosity function.

is the cumulative luminosity function.

In the following we present the results in two different ways.

We first estimate the LF in discrete luminosity bins, expressing it in

the logarithmic form ![]() (or in the equivalent form in magnitudes). We then show the results of

fitting these binned LFs with simple parametric expressions. As usual,

the fit parameters are always expressed in terms of the non-logarithmic

form

(or in the equivalent form in magnitudes). We then show the results of

fitting these binned LFs with simple parametric expressions. As usual,

the fit parameters are always expressed in terms of the non-logarithmic

form ![]() .

.

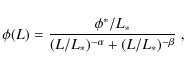

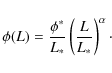

The most frequently adopted parametric form for the AGN

luminosity function is a double power law:

|

(2) |

where L* is a characteristic break luminosity,

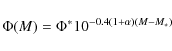

It will be seen that the local AGN LF is close to a single

power law, so we will also consider that even simpler form:

|

(3) |

Expressed in absolute magnitudes these functions have following form:

|

(4) |

for the double power law, and

|

(5) |

for the single power law, with

5.2 Broad band luminosity function

We first present the broad band luminosity function, using the full sample of 329 type-1 AGN with z<0.3. This updates the previous work of Wisotzki (2000b), with several improvements: (i) the sample size has doubled; (ii) the quality of the external photometric calibration is improved. (iii) The correction for Galactic extinction has been updated; (iv) we now; also include the effects of differential evolution within the redshift range 0 < z < 0.3 (see below).

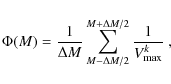

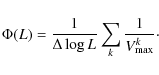

We determined the binned luminosity function using the

classical ![]() estimator (Schmidt 1968).

The luminosity function is then calculated by:

estimator (Schmidt 1968).

The luminosity function is then calculated by:

where

In adopting this form we explicitly assume that the probability of finding an AGN in the HES is independent of redshift. While this would be too strong an assumption for the full quasar sample, it is certainly justified for the restricted low-redshift range z<0.3 considered here. The SEDs of typical type 1 AGN (without host galaxy contributions) at such low redshifts are distinctly blue in the optical/UV, and significant marked variation with redshift occur beyond z>0.5. (Note that we do not consider here the role of ``red'' quasars which would be lost in the HES altogether.) If

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=-90,width=8.5cm,clip]{12730f07.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/44/aa12730-09/Timg57.png)

|

Figure 7:

The differential broad band quasar luminosity function of the HES for |

| Open with DEXTER | |

The resulting AGN luminosity function is shown in Fig. 7, covering the

range ![]() in bins of 0.5 mag. It shows remarkably little structure and

rises steadily up to the faintest luminosities in the sample. At

in bins of 0.5 mag. It shows remarkably little structure and

rises steadily up to the faintest luminosities in the sample. At ![]() there

appears to be an abrupt break which almost certainly is an artefact,

indicating the inevitable onset of severe incompleteness in the HES

sample for very low luminosities. For such objects, the host galaxy

contribution even to the HES nuclear extraction scheme will be

substantial, modifying the slitless spectra in a way that they no

longer can be discriminated from normal, inactive galaxies. It is

remarkable that this effect plays a role only for the lowest luminosity

bins; there is no gradual turnover that might indicate incompleteness

already at higher luminosities (alternatively, invoking incompleteness

would imply an even steeper LF which would be inconsistent with other

results, see below).

there

appears to be an abrupt break which almost certainly is an artefact,

indicating the inevitable onset of severe incompleteness in the HES

sample for very low luminosities. For such objects, the host galaxy

contribution even to the HES nuclear extraction scheme will be

substantial, modifying the slitless spectra in a way that they no

longer can be discriminated from normal, inactive galaxies. It is

remarkable that this effect plays a role only for the lowest luminosity

bins; there is no gradual turnover that might indicate incompleteness

already at higher luminosities (alternatively, invoking incompleteness

would imply an even steeper LF which would be inconsistent with other

results, see below).

If we ignore the lowest luminosity bins affected by

incompleteness, the MBJ

AGN luminosity function is consistently described by a single power law

with slope ![]() .

Fitting instead a double power law to all bins results in the same

bright-end slope and a break at MBJ=-18.75.

A double power law fit to these data is apparently not physically

meaningful.

.

Fitting instead a double power law to all bins results in the same

bright-end slope and a break at MBJ=-18.75.

A double power law fit to these data is apparently not physically

meaningful.

The observation that the local AGNLF is perfectly described by a single power law is in excellent qualitative and quantitative agreement with previous results obtained in the course of the HES (Koehler et al. 1997; Wisotzki 2000b). It is however inconsistent with z=0 extrapolations of the double power law AGNLF obtained at higher redshifts. We will discuss this point in Sect. 6.4.

Table 2: Binned differential luminosity function in the BJ band, corrected for evolution.

The evolution of comoving AGN space densities with redshift is

sufficiently fast that there is a noticeable effect even within the

range 0<z<0.3. To derive a truly

``local'' (z=0) AGNLF we have to take evolution into

account. The ![]() formalism (Schmidt 1968)

provides a simple but adequate recipe to do so. If our sample were

unaffected by evolution, we would expect to find

formalism (Schmidt 1968)

provides a simple but adequate recipe to do so. If our sample were

unaffected by evolution, we would expect to find ![]() .

Our measured value is

.

Our measured value is ![]() ,

implying some evolution. To correct the z<0.3

AGNLF to z=0, we approximate the evolution within

this small redshift interval as pure density evolution (PDE), i.e.

,

implying some evolution. To correct the z<0.3

AGNLF to z=0, we approximate the evolution within

this small redshift interval as pure density evolution (PDE), i.e. ![]() .

We varied the density evolution parameter

.

We varied the density evolution parameter ![]() until we reached

until we reached ![]() .

To increase the leverage we performed the same exercise for a larger

redshift range, including quasars from the HES sample up to z=0.6.

We found that the evolution within this redshift interval is well

described by a PDE model with

.

To increase the leverage we performed the same exercise for a larger

redshift range, including quasars from the HES sample up to z=0.6.

We found that the evolution within this redshift interval is well

described by a PDE model with ![]() ,

essentially independent of the exact value of the outer redshift

boundary. Notice that beyond the very local universe, the HES samples

only the brightest quasars, and our correction for the most part

concerns these high-luminosity bins only. For a single power law,

density and luminosity evolution are indistinguishable. Therefore our

evolution correction does not critically depend on the choice of the

actually adopted model.

,

essentially independent of the exact value of the outer redshift

boundary. Notice that beyond the very local universe, the HES samples

only the brightest quasars, and our correction for the most part

concerns these high-luminosity bins only. For a single power law,

density and luminosity evolution are indistinguishable. Therefore our

evolution correction does not critically depend on the choice of the

actually adopted model.

We then applied the parameterised density evolution to the HES

z<0.3 sample to recompute the

evolution-corrected z=0 AGNLF. Note that we used

the objects at z>0.3 only to constrain the

density evolution index ![]() and not for the luminosity function.

and not for the luminosity function.

We still obtain a relation very close to a single power law,

which however is slightly steeper than the uncorrected one. The best

fit power law slope is now ![]() .

This evolution-corrected AGNLF is also shown in Fig. 7. It is provided

in tabulated form in Table 2.

.

This evolution-corrected AGNLF is also shown in Fig. 7. It is provided

in tabulated form in Table 2.

5.3 Emission line luminosity function

The emission line luminosity function (ELF) - the number of AGN per

unit volume per unit logarithmic emission line luminosity - is

given by

|

(8) |

The selection of AGN in the HES in this redshift range (and up to

Table 3:

Binned H![]() and H

and H![]() emission line luminosity functions.

emission line luminosity functions.

The resulting ELFs for H![]() and H

and H![]() are shown in Fig. 8,

binned into luminosity intervals of 0.25 dex. The binned

values are given in Table 3.

are shown in Fig. 8,

binned into luminosity intervals of 0.25 dex. The binned

values are given in Table 3.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=-90,width=8.5cm,clip]{12730f08.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/44/aa12730-09/Timg107.png)

|

Figure 8:

Binned emission line AGN luminosity functions, for H |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Figure 8

displays a very similar behaviour of the ELF when compared to the

broad-band LF of Fig. 7:

It rises nearly as a straight line, i.e. as a single power law, until a

sharp cutoff at low luminosities indicates the onset of sample

selection incompleteness. Fitting power law relations to the data

(again excluding the obviously incomplete lowest luminosity bins) gives

slopes of ![]() and

and ![]() ,

respectively. Fitting a double power law improves the fit quality only

marginally. We conclude that a description of the ELF as a single power

law, for the luminosity range covered by our data, seems most

appropriate.

,

respectively. Fitting a double power law improves the fit quality only

marginally. We conclude that a description of the ELF as a single power

law, for the luminosity range covered by our data, seems most

appropriate.

6 Discussion

6.1 Low luminosity-AGN: comparison with SDSS

The sharp cutoff in the binned luminosity functions at nuclear

luminosities ![]() or

or ![]() clearly signals the onset of incompleteness in our sample. This

luminosity approximately marks the limit where AGN cease to be

conspicuous in the optical and tend to be masked by their host

galaxies. However, deep spectroscopic surveys of galaxies have shown

that the AGN phenomenon persists down to very low levels (e.g. Ho et al. 1997). In those

cases, the only traceable indicator of nuclear activity in the optical

are the emission lines, thus the statistics have to be expressed in

terms of an ELF. This was recently performed by Hao

et al. (2005a, hereafter H05), who selected a set of

clearly signals the onset of incompleteness in our sample. This

luminosity approximately marks the limit where AGN cease to be

conspicuous in the optical and tend to be masked by their host

galaxies. However, deep spectroscopic surveys of galaxies have shown

that the AGN phenomenon persists down to very low levels (e.g. Ho et al. 1997). In those

cases, the only traceable indicator of nuclear activity in the optical

are the emission lines, thus the statistics have to be expressed in

terms of an ELF. This was recently performed by Hao

et al. (2005a, hereafter H05), who selected a set of

![]() 1000

Seyfert 1 galaxies from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (main

galaxy sample) to measure H

1000

Seyfert 1 galaxies from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (main

galaxy sample) to measure H![]() line luminosities and construct the ELF. The redshift range covered in

their sample is 0<z<0.15, and the

luminosity range is (1038.5-1043) erg s-1.

H05 found their ELF to be in good agreement with several parametric

descriptions, including single and double power laws and also a

Schechter function. However, differences between these forms become

manifest only at their highest luminosities, for

line luminosities and construct the ELF. The redshift range covered in

their sample is 0<z<0.15, and the

luminosity range is (1038.5-1043) erg s-1.

H05 found their ELF to be in good agreement with several parametric

descriptions, including single and double power laws and also a

Schechter function. However, differences between these forms become

manifest only at their highest luminosities, for ![]() erg s-1

. Over much of the luminosity range, their data suggest a single power

law.

erg s-1

. Over much of the luminosity range, their data suggest a single power

law.

Fortunately the high-luminosity end of

H05 overlaps quite well with the low-luminosity end

of our H![]() ELF, so that a comparison is straightforward. This is shown in

Fig. 9

where we plot the Seyfert 1 H

ELF, so that a comparison is straightforward. This is shown in

Fig. 9

where we plot the Seyfert 1 H![]() luminosity function of H05 (adapted to our cosmology) together with our

H

luminosity function of H05 (adapted to our cosmology) together with our

H![]() LF. The transition from one dataset to the other is remarkably smooth,

if the incomplete lowest luminosity bins in the HES sample are ignored.

Over the luminosity range in common, both ELFs are fully consistent

with each other.

LF. The transition from one dataset to the other is remarkably smooth,

if the incomplete lowest luminosity bins in the HES sample are ignored.

Over the luminosity range in common, both ELFs are fully consistent

with each other.

Even more remarkably, the shape of the combined H![]() LF - now covering almost 5 orders of magnitude in luminosity - is still

close to that of a single power law. Already the fit to the HES H

LF - now covering almost 5 orders of magnitude in luminosity - is still

close to that of a single power law. Already the fit to the HES H![]() LF alone is almost consistent with the H05 LF. Combining both samples,

we find a best-fit power law slope of

LF alone is almost consistent with the H05 LF. Combining both samples,

we find a best-fit power law slope of ![]() .

This fit is shown as the dashed-dotted line in Fig. 9.

.

This fit is shown as the dashed-dotted line in Fig. 9.

However, there is evidence for some

curvature in the LF, as the H05 LF alone is flatter (

![]() )

than the HES ELF. This is manifest in a `bulge' around 1042

erg s-1, where the space density of the combined

LF is above the fitted single power law. A better fit is obtained by a

double power law breaking at

)

than the HES ELF. This is manifest in a `bulge' around 1042

erg s-1, where the space density of the combined

LF is above the fitted single power law. A better fit is obtained by a

double power law breaking at ![]() ,

with a faint-end slope of

,

with a faint-end slope of ![]() describing the SDSS data and a bright-end slope of

describing the SDSS data and a bright-end slope of ![]() describing the HES. This mildly curved relation, shown by the dashed

line in Fig. 9,

traces the combined data extremely well.

describing the HES. This mildly curved relation, shown by the dashed

line in Fig. 9,

traces the combined data extremely well.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=-90,width=8.5cm,clip]{12730f09.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/44/aa12730-09/Timg117.png)

|

Figure 9:

Comparison of the H |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Some caveats are in place regarding the combination of the two

datasets. Although H05 determined the narrow H![]() components separately, their broad-line ELF does not have this

component subtracted, whereas we tried to remove it. As such a removal

was possible in only a small number of cases, the different treatment

does not make much difference. More relevant might be the possibility

of a systematic variation of the narrow H

components separately, their broad-line ELF does not have this

component subtracted, whereas we tried to remove it. As such a removal

was possible in only a small number of cases, the different treatment

does not make much difference. More relevant might be the possibility

of a systematic variation of the narrow H![]() contribution to the total H

contribution to the total H![]() flux with luminosity. However, the narrow H

flux with luminosity. However, the narrow H![]() LF published by H05 has also a slope of -1.8, which indicates that

there should be no major bias introduced.

LF published by H05 has also a slope of -1.8, which indicates that

there should be no major bias introduced.

Another methodical difference lies in the fact that we

corrected our LF for evolution, whereas H05 did not. If we assume that

the most luminous objects of H05 lie close to their high-redshift limit

of z< 0.15 and adopting our simple PDE

recipe, then the H05 space densities would have to be corrected

downward by a factor of ![]() ,

i.e. by 0.3 dex; this correction would rapidly decrease

towards lower luminosities. The net effect would hardly be visible in

Fig. 9.

,

i.e. by 0.3 dex; this correction would rapidly decrease

towards lower luminosities. The net effect would hardly be visible in

Fig. 9.

We note that recently, Greene

& Ho (2007) (hereafter GH07) derived the AGN H![]() LF based on a combined sample of about 9000 broad line AGN from the

SDSS. Their space densities are considerably below ours, and the two

LFs are highly inconsistent (the same discrepancy exists between the

GH07 and H05 results). This inconsistency has been traced back to an

error made by GH07 in the determination of their

LF based on a combined sample of about 9000 broad line AGN from the

SDSS. Their space densities are considerably below ours, and the two

LFs are highly inconsistent (the same discrepancy exists between the

GH07 and H05 results). This inconsistency has been traced back to an

error made by GH07 in the determination of their ![]() values (Greene, private communication). Therefore the luminosity

function as well as the black hole mass function presented in GH07 are

incorrect. Removing the error alleviates the discrepancy, and the

corrected H

values (Greene, private communication). Therefore the luminosity

function as well as the black hole mass function presented in GH07 are

incorrect. Removing the error alleviates the discrepancy, and the

corrected H![]() luminosity function for the low redshift AGN sample from GH07 is

consistent with the HES luminosity function presented in this work.

luminosity function for the low redshift AGN sample from GH07 is

consistent with the HES luminosity function presented in this work.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[origin=rb,angle=-90,width=12cm,clip]{12730f10.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/44/aa12730-09/Timg119.png)

|

Figure 10:

Local AGN luminosity function constructed as a combination of the SDSS

broad line AGN LF from Hao

et al. (2005a) and our H |

| Open with DEXTER | |

6.2 The combined local AGN luminosity function

Given the good agreement of the local HES LF, which traces the

bright end, and the SDSS Seyfert 1 LF sampling the faint end,

and having the mentioned caveats in mind, it is justified to combine

both datasets. Our aim is to present a single best-knowledge local

AGNLF in the optical, covering the broadest possible range of

luminosities. Because of its robustness against dilution due to host

galaxy light, we used the H![]() luminosity functions of HES and SDSS. We adopted a bin size of

0.24 dex (0.6 mag) as an integer multiple of the

binned values published by H05. We then recomputed the H

luminosity functions of HES and SDSS. We adopted a bin size of

0.24 dex (0.6 mag) as an integer multiple of the

binned values published by H05. We then recomputed the H![]() ELF from the HES data for the same bins and merged the two datasets,

with weights provided by the inverse statistical variances.

ELF from the HES data for the same bins and merged the two datasets,

with weights provided by the inverse statistical variances.

Table 4: Fit parameters for the AGNLF.

For easy comparison with other AGN luminosity functions,

especially at higher redshifts, we converted this combined LF into two

common reference systems: (i) absolute magnitudes MB

in the standard Johnson B band; and (ii) bolometric

luminosity units.

These conversions involve translating the H![]() data into broad band or bolometric fluxes. There is a very tight

correlation between H

data into broad band or bolometric fluxes. There is a very tight

correlation between H![]() luminosity and absolute blue magnitude in the HES (Fig. 6). The

translation relation is

luminosity and absolute blue magnitude in the HES (Fig. 6). The

translation relation is ![]() .

This relation is covered by our data down to

.

This relation is covered by our data down to ![]() .

In order to incorporate also the lower luminosity SDSS data we now make

the somewhat unguarded step of extrapolating the translation of

.

In order to incorporate also the lower luminosity SDSS data we now make

the somewhat unguarded step of extrapolating the translation of ![]() to MB

towards lower L. This certainly introduces

additional uncertainties, including the possibility that some of the

lowest luminosity AGN could have very different spectral energy

distributions (for example, the structure of the accretion disk might

change drastically). On the other hand, there is no reason to expect

such a change to occur just at the transition luminosity from HES to

SDSS, so some degree of extrapolation is most probably justified.

to MB

towards lower L. This certainly introduces

additional uncertainties, including the possibility that some of the

lowest luminosity AGN could have very different spectral energy

distributions (for example, the structure of the accretion disk might

change drastically). On the other hand, there is no reason to expect

such a change to occur just at the transition luminosity from HES to

SDSS, so some degree of extrapolation is most probably justified.

The resulting combined local AGN LF is shown in Fig. 10, ranging

from ![]() to

to ![]() (with the above caveat). Also shown as a dotted line is the best fit

single power law, and as a solid line the best fit double power law;

the fit parameters are provided in Table 4. The double power

law gives a very good overall description, but the departure from a

single power law is not large, albeit statistically significant. There

are some minor wiggles in the binned LF that are most probably due to

underlying unaccounted for systematics; note however that there is no

trace of the HES-SDSS intersection (rather: transition region) around

(with the above caveat). Also shown as a dotted line is the best fit

single power law, and as a solid line the best fit double power law;

the fit parameters are provided in Table 4. The double power

law gives a very good overall description, but the departure from a

single power law is not large, albeit statistically significant. There

are some minor wiggles in the binned LF that are most probably due to

underlying unaccounted for systematics; note however that there is no

trace of the HES-SDSS intersection (rather: transition region) around ![]() .

.

For the convenience of the reader we also provide this LF in tabulated form, both in terms of the B band and as a bolometric LF. For the latter we adopted the luminosity-dependent bolometric corrections of Marconi et al. (2004). A separate double power law fit to the resulting bolometric LF is also provided in Table 4. Recall that this bolometric luminosity function is valid only for broad-line (type 1) AGN, without any accounting for obscuration.

Table 5: Combined binned local AGNLF, based on the SDSS broad line galaxy sample (faint end) and the Hamburg/ESO Survey (bright end).

6.3 Comparison with X-ray selected samples

X-ray surveys have made a great impact on our understanding of the AGN population, chiefly through their ability to find low-luminosity AGN at all redshifts. However, because of the expensive spectroscopic follow-up, sample statistics are still moderate despite considerable efforts.

The only dedicated effort to estimate an optical local AGNLF

from an X-ray selected sample was published by Londish et al. (2000).

Their bright-end slope of ![]() (without evolution correction) is similar to ours, but they obtained a

shallow faint end slope of

(without evolution correction) is similar to ours, but they obtained a

shallow faint end slope of ![]() ,

however with considerable error bars. Our new results, in particular in

combination with SDSS, show clearly that such a flat slope is ruled out

and that the local AGNLF continues to rise towards very faint

luminosities.

,

however with considerable error bars. Our new results, in particular in

combination with SDSS, show clearly that such a flat slope is ruled out

and that the local AGNLF continues to rise towards very faint

luminosities.

A local (z=0) luminosity function from an AGN sample selected in the soft X-ray (0.5-2 keV) band was presented by Hasinger et al. (2005). Their sample is restricted to unabsorbed type 1 AGN and is therefore very comparable to ours. To facilitate a comparison, we again used the L-dependent bolometric corrections of Marconi et al. (2004) to convert our combined optical AGNLF into the soft X-ray domain. In Fig. 11 we compare the z=0 XLF of Hasinger et al. (2005) with our prediction. The X-ray points are represented by the filled blue triangles, which are the binned estimate in the redshift shell z=0.015-0.2 of Fig. 7 in Hasinger et al. (2005), corrected to redshift zero. The blue dotted line shows their best-fit luminosity-dependent density evolution (LDDE) model for z=0.

For intermediate and high luminosities, the observed XLF and the prediction based on the optical AGNLF are in good agreement. However, the two LFs disagree strongly at the faint end, with the optical LF predicting more than an order of magnitude higher space densities at given X-ray luminosity compared to the directly determined XLF.

Is there an explanation for these discrepancies? One possibility might be that the adopted conversion from optical to X-ray luminosities has been inadequate. In order to explore this option we alternatively tried a constant optical/X-ray luminosity ratio; the dashed line in Fig. 11 shows our double-power law relation converted with such a relation. Evidently, that predicted LF is a very good match to the bright end of the XLF. At the faint end the two LFs still disagree, but the disagreement is now much less. Thus it appears possible that the luminosity dependence of the optical/X-ray ratio is much weaker than usually assumed; if so, it would certainly help to reconcile the two luminosity functions. Another possibility is, of course, incompleteness among the fainter objects in the X-ray sample. We reiterate however that since both optically and X-ray selected samples contain only broad-line AGN, any incompleteness due to obscuration should be irrelevant in this context.

6.4 Comparison with higher redshifts: evidence for ``AGN downsizing''

We now perform a direct comparison of our local AGNLF with luminosity functions based on surveys that probe mainly the higher redshift AGN population. This is interesting not only because a comparison with z=0 provides the longest leverage in redshifts, but also because the local luminosity function can be traced to very faint luminosities and high space densities. A full investigation of the redshift evolution of the AGNLF is outside of the scope of this paper; we limit ourselves to a simple comparison between the z=0 LF determined above and parametric representations of the AGNLF evaluated at z=1.5, the latter chosen as a representative point at moderately high redshift where several surveys have been able to leave their marks.

The results of this comparison are displayed in Fig. 12. The datapoints and the solid line show our combined local AGNLF. The thick dashed line shows the z=1.5 fit to the optical AGNLF, very recently obtained by Croom et al. (2009b), combining QSOs from the 2SLAQ survey (Croom et al. 2009a) with the results from the SDSS (Richards et al. 2006) at the bright end. They found their data to be in good overall agreement with a double power law LF and use a luminosity and density evolution model that also included evolution in the bright-end slope (LEDE).

As a second reference we considered the AGNLF by Bongiorno et al. (2007) (dotted line), derived from a combination of the SDSS at the bright end and the faint type 1 AGN sample from the VVDS (Gavignaud et al. 2006). This sample is noteworthy in that it is certainly the most complete set of low-luminosity AGN at substantial z, as it is purely flux limited and not affected by any colour or morphological preselection. As seen in Fig. 12, the two z=1.5 luminosity functions are highly consistent with each other.

We then formally extrapolated these AGNLF models to z=0,

shown as thin dotted line for the luminosity dependent density

evolution (LDDE) model by Bongiorno

et al. (2007), as thin dashed line for the LEDE

model and as dashed dotted line for the LDDE model by Croom et al. (2009b).

All three extrapolations are clearly not in agreement with the local

AGNLF, in several aspects: They all overpredict the space density of

bright AGN. The LDDE model by Bongiorno

et al. (2007) and the LEDE model by Croom et al. (2009b)

also underpredict the space density of low-luminosity AGN, while the

LDDE model by Croom et al.

(2009b) is roughly consistent with our data at the faint end.

These mismatches demonstrate that the local AGNLF provides indeed

additional and independent constraints for the evolution of the AGN

luminosity function. The above evolution models have been derived from

higher redshift data which they fit very well; evidently, these models

may not be extrapolated outside the range where they were

observationally established. Thus, a direct determination of the AGNLF

at all z, including ![]() ,

is essential.

,

is essential.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=-90,width=8.5cm,clip]{12730f11.eps}

\vspace*{.5mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/44/aa12730-09/Timg182.png)

|

Figure 11: Comparison of the soft X-ray LF of type 1 AGN by Hasinger et al. (2005) with the prediction based on the optical local AGNLF. The filled blue triangles show the binned X-ray (0.5-2 keV) LF within z=0.015-0.2, corrected to z=0. The blue dotted line shows the LDDE model of Hasinger et al. (2005) for z=0. The filled black circles and the solid line show the binned data and the double power law fit to the optical HES+SDSS LF, converted to soft X-rays using a luminosity dependent correction. The dashed line shows the same double power law fit, but converted to soft X-rays using a constant correction. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=-90,width=8.5cm,clip]{12730f12.eps}

\vspace*{3mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/44/aa12730-09/Timg183.png)

|

Figure 12: Shape evolution and ``downsizing'' of the AGNLF between z=1.5 and z=0. Filled circles and solid line denote our combined HES+SDSS AGNLF at z=0. The blue dashed and red dotted lines show the best fit model to the data of the z=1.5 AGNLF of the 2SLAQ+SDSS (Croom et al. 2009b) and the VVDS+SDSS (Bongiorno et al. 2007), respectively. The thin black dashed, dashed-dotted and dotted lines show the z=0 extrapolations of the LEDE model and the LDDE model by Croom et al. (2009b) and the LDDE model by Bongiorno et al. (2007), respectively. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Comparing the z=1.5 Bongiorno

et al. (2007) or Croom

et al. (2009b) and the local AGNLF reveals a

striking change in the shape of the luminosity function: The pronounced

break visible at higher z is almost absent in the

local LF. In terms of space densities, this implies that while

high-luminosity AGN were much more frequent at

high redshifts, AGN with nuclear luminosities around ![]() are as common in the local universe as they were at high z.

For somewhat fainter AGN this relation might even be reversed, although

there are too many uncertainties to make such a claim.

are as common in the local universe as they were at high z.

For somewhat fainter AGN this relation might even be reversed, although

there are too many uncertainties to make such a claim.

Such a ``downsizing'' behaviour of the AGN population was

first detected through X-ray surveys (Hasinger et al. 2005;

Ueda

et al. 2003) and recently also in optical surveys (Croom et al. 2009b).

Here we strongly confirm the presence of this ``downsizing'' behaviour

in the optical AGNLF which becomes increasingly prominent at low

redshifts. We especially see clear evidence for evolution in the

faint-end slope of the AGNLF. Note that this conclusion does not hinge

on our extrapolation of the H![]() -MB

relation, as the crossing of the z=1.5 and z=0

LFs occurs at luminosities still covered by the HES.

-MB

relation, as the crossing of the z=1.5 and z=0

LFs occurs at luminosities still covered by the HES.

7 Conclusions

We have presented a new determination of the local (

![]() )

luminosity function of broad-line active galactic nuclei. Our sample

was drawn from the Hamburg/ESO Survey and contains 329 quasars and

Seyfert 1 galaxies with z<0.3,

selected from surveying almost 7000 deg2

in the southern sky. As a central feature, our broad-band magnitudes

were measured in the survey data with a point-source matching approach,

strongly reducing the contribution of host galaxy flux to the inferred

AGN luminosity. Compared to our previous work we have not only

substantially increased the statistical basis, but also added a number

of methodical improvements.

)

luminosity function of broad-line active galactic nuclei. Our sample

was drawn from the Hamburg/ESO Survey and contains 329 quasars and

Seyfert 1 galaxies with z<0.3,

selected from surveying almost 7000 deg2

in the southern sky. As a central feature, our broad-band magnitudes

were measured in the survey data with a point-source matching approach,

strongly reducing the contribution of host galaxy flux to the inferred

AGN luminosity. Compared to our previous work we have not only

substantially increased the statistical basis, but also added a number

of methodical improvements.

In the construction of the broad band (BJ)

luminosity function, we now included the effects of differential number

density evolution within our narrow redshift range, ![]() .

Since the most luminous AGN tend to be located near the outer edge of

that range, ignoring evolution makes the luminosity function appear

slightly too shallow. We find that the evolution-corrected local

luminosity function within

.

Since the most luminous AGN tend to be located near the outer edge of

that range, ignoring evolution makes the luminosity function appear

slightly too shallow. We find that the evolution-corrected local

luminosity function within ![]() is well-described by a single power law of slope

is well-described by a single power law of slope ![]() ,

still significantly shallower than the z=0

extrapolation of the AGNLF measured at higher redshifts.

,

still significantly shallower than the z=0

extrapolation of the AGNLF measured at higher redshifts.

As a second and independent measure of AGN power we

investigated the distribution of Balmer emission line luminosities, in

particular the broad H![]() and H

and H![]() lines. These lines can be detected and accurately isolated in optical

spectra even of low-luminosity AGN where the host galaxy is bright

compared to the nucleus. We found a very tight correlation between H

lines. These lines can be detected and accurately isolated in optical

spectra even of low-luminosity AGN where the host galaxy is bright

compared to the nucleus. We found a very tight correlation between H![]() luminosities and broad band absolute magnitudes MBJ

over the entire luminosity range of our sample, confirming that host

galaxy contamination to the MBJ

magnitudes is unimportant.

luminosities and broad band absolute magnitudes MBJ

over the entire luminosity range of our sample, confirming that host

galaxy contamination to the MBJ

magnitudes is unimportant.

We constructed the broad emission line luminosity functions

for H![]() and H

and H![]() ,

and found them to agree well with the broad band LF. In particular,

there is again no trace of significant curvature over the covered

luminosity range, and a single power law is still sufficient to

describe the shape of the LF.

,

and found them to agree well with the broad band LF. In particular,

there is again no trace of significant curvature over the covered

luminosity range, and a single power law is still sufficient to

describe the shape of the LF.

We found excellent consistency between our data and the H![]() emission line luminosity function of low-luminosity AGN determined from

the SDSS by (Hao et al. 2005a).

While the two datasets are complementary in luminosity coverage, our

low-luminosity end overlaps very well with their high-luminosity end.

The SDSS data seamlessly continue the rise of the LF towards the domain

of low-luminosity Seyferts. The comparison with SDSS also delineates

clearly that below

emission line luminosity function of low-luminosity AGN determined from

the SDSS by (Hao et al. 2005a).