| Issue |

A&A

Volume 506, Number 3, November II 2009

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Page(s) | 1381 - 1391 | |

| Section | The Sun | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/200811074 | |

| Published online | 22 July 2009 | |

A&A 506, 1381-1391 (2009)

Complexity in the sunspot cycle

G. Consolini1 - R. Tozzi2 - P. De Michelis2

1 - INAF - Istituto di Fisica dello Spazio Interplanetario, 00133 Roma, Italy

2 -

Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia, 00143 Roma, Italy

Received 2 October 2008 / Accepted 5 June 2009

Abstract

The occurrence of complexity in the solar cycle, as monitored by the

sunspot area butterfly diagram, is investigated by means of the natural

orthogonal composition (NOC) technique and information theory approach.

Although the butterfly diagram may be reconstructed using only two

modes as already found in other papers for the Hale cycle, on deeper

investigation it is possible to notice that the high variability,

complexity, and stochasticity observed during the solar cycle are

missing. A full description of the complex evolution of the solar cycle

requires at least 30 modes. We show that these modes identify two

different dynamical regimes, whose existence is also confirmed by the

analysis of the Lyapunov exponents of the associated principal

components. We suggest that the existence of these two physical

dynamical regimes is at the origin of the dynamical complexity of the

solar cycle. We attempt a discussion of these dynamical regimes also in

terms of a nearly stable dynamo process described by the first two

modes and a local superficial turbulent dynamo responsible for the more

stochastic features observed in the solar cycle.

Key words: Sun: activity - Sun: sunspots - methods: statistical - chaos

1 Introduction

The Sun has been observed through telescopes for almost four centuries. During this period, our understanding of the Sun and of its dynamics has undergone a profound revolution. However, it is only in the past few decades that the traditional view of many solar features has been completely reconsidered in the light of both theoretical advances and high-resolution ground and space observations.

Solar activity is traditionally estimated by the relative sunspot number R, also known as the Wolf sunspot number, which represents a qualitatively reliable proxy of the activity itself. The Wolf sunspot number R is important because it is one of the oldest and longest running direct record of solar activity, with reliable observations starting in 1610.

However, a more informative characterization of the solar cycle in terms of sunspots is provided by the spatio-temporal diagram built by plotting, for each solar rotation cycle (Carrington cycle), the total area of observed sunspots as a function of latitude. This diagram, known as butterfly diagram, shows that sunspots are not randomly distributed over the solar surface but, at any stage of the cycle, they are concentrated in a latitudinal band across the solar equator. Since sunspots represent a surface manifestation of the emergence of the toroidal magnetic field residing in the solar interior, the butterfly diagram also represents a spatio-temporal map of the solar internal large-scale toroidal magnetic field.

In spite of its nearly-cyclic nature, the solar cycle is characterized by amplitude, period, and shape, which vary irregularly. These irregularities appear to be an intrinsic feature of the solar cycle being observed in many other solar observables including irradiance, surface flows, and polar faculae counts. Anyway, the origin of these irregularities is still unclear.

Using the temporal and latitudinal distribution of sunspots recorded since 1874, it was proposed (Mininni et al. 2002) that the solar magnetic cycle, investigated by means of the butterfly diagram, might be interpreted as being the result of the superposition of two oscillations, characterized by constant amplitude and phase and by a period close to 22 years, on a stochastic background. This suggested that the spatio-temporal irregularities observed in the solar magnetic cycle were not a plain manifestation of low-dimensional chaos being due to the interaction of two superposed antisymmetric modes with a stochastic background (Mininni et al. 2002,2004). Similar results were found by Lawrence et al. (2005), who investigated the 22 year solar cycle by NSO Kitt Peak synoptic maps, and by Vecchio et al. (2005), who studied the spatio-temporal features of 11-year solar activity using the green coronal emission line at 530.3 nm. In contrast, Letellier et al. (2006) showed that the 22-year solar magnetic cycle, as reconstructed by sunspot time series, is in agreement with a low-dimensional chaotic dynamics. In detail, they showed that the phase-space diagram (the phase portrait) of the sunspot number resembles that of a Rössler dynamical system.

The aforementioned results seem to point towards the occurrence of spatio-temporal and/or dynamical complexity in the solar cycle. Quoting Nicolis & Nicolis (2007), complexity is not a mere metaphor or a nice way to put certain intriguing things, it is a phenomenon that is deeply rooted into the laws of nature, where systems involving large numbers of interacting subunits are ubiquitous. Furthermore, Chang et al. (2006) defined the dynamical complexity as a phenomenon exhibited by a nonlinearly interacting dynamical system within which multitudes of different sizes of large scale coherent structures are formed, resulting in a global nonlinear stochastic behavior for the dynamical systems, which is vastly different from that could be surmised from the original dynamical equations. In this framework, complexity can be defined as the tendency of a non-equilibrium system to show a certain degree of spatio-temporally coherent features resulting from the competition of different basic spatial patterns (Badii & Politi 1997) playing the role of interacting subunits. As a result, the spatio-temporal evolution of these complex systems may display evolutionary events as for instance those observed in the case of turbulent systems. It is important to emphasize that complexity requires the occurrence of nonlinearities and the intertwining of order and disorder (Nicolis & Nicolis 2007), and that it is generally related to the emergence of self-organization in open systems (Klimontovich 1991,1996).

Here, using the natural orthogonal composition (NOC) technique, we

investigate the emergence of spatio-temporal complexity in the 11-year

solar cycle, as monitored by the sunspot area butterfly diagram. By

applying a 2![]() order complexity measure

(Shiner et al. 1999), we show that spatio-temporal and/or dynamical complexity is an intrinsic property

of the solar cycle, and that the long-term evolution of solar cycle activity seems to point towards a more

regular (less complex) behavior.

order complexity measure

(Shiner et al. 1999), we show that spatio-temporal and/or dynamical complexity is an intrinsic property

of the solar cycle, and that the long-term evolution of solar cycle activity seems to point towards a more

regular (less complex) behavior.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides a brief introduction to the NOC technique. In Sect. 3, we describe the data set and results from the NOC analysis, the study of the chaotic and spectral features of the principal components (PCs). In particular, we pay attention to the first two PCs by comparing their phase portrait with that coming from a stochastic version of a Lotka-Volterra predator-prey model. In this section, we also show the occurrence of dynamical complexity obtained by the application of information theory descriptors. In Sect. 4, we summarize our findings and draw conclusions.

2 The natural orthogonal composition technique: a brief introduction

The natural orthogonal composition (NOC) (Jackson et al. 1991; Golovkov et al. 1992) is a technique that can be used for feature extraction, i.e., given a set of multivariate measurements NOC is expected to be able to provide a smaller set of uncorrelated variables or components whose proper combination gives back the larger starting set. In practice, given a set of observations, it is possible to estimate a set of independent eigenvectors and eigenvalues whose combination allows rewriting the observed variables. Since this operation corresponds to transforming the natural basis on which we observe the variable, into a new orthogonal basis by diagonalizing the variance matrix, the NOC technique consists essentially of a rotation of the old basis into the new one.

NOC has been widely used in literature, for instance for the study of daily magnetic variations (Golovkov et al., 1978; Xu & Kamide, 2004), for space-time analysis of the main geomagnetic field (Rotanova et al., 1982), for the study of global models of the geomagnetic field (Xu, 2003), and even for the automatic calculation of geomagnetic K indices (Golovkov et al. 1989). Before describing the application of NOC, we introduce the method briefly.

We assume that we measure a spatio-temporal variable ![]() at a certain time t consisting

of m elements, where m is the number of latitudinal spatial positions (pixels). Given a number of samples at different spatio-temporal locations,

the application of NOC allows us to extract a smaller set of variables, such as empirical

orthogonal functions (EOFs) and principal components

(PCs), capable of describing the entire set of

observations. Although there are many methods capable of doing this

job, the benefit of NOC is that the set of functions (EOFs) used in the

expansion of the time series is not determined in advance but is

estimated using only the observed data.

at a certain time t consisting

of m elements, where m is the number of latitudinal spatial positions (pixels). Given a number of samples at different spatio-temporal locations,

the application of NOC allows us to extract a smaller set of variables, such as empirical

orthogonal functions (EOFs) and principal components

(PCs), capable of describing the entire set of

observations. Although there are many methods capable of doing this

job, the benefit of NOC is that the set of functions (EOFs) used in the

expansion of the time series is not determined in advance but is

estimated using only the observed data.

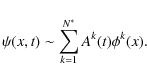

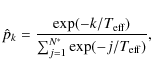

We now write the spatio-temporal field

![]() at position xi and time tj to be:

at position xi and time tj to be:

where the collection of values

To evaluate the EOFs ![]() and the associated PCs Ak from a data set, it is

necessary to minimize the error made in the representation by means of the expansion of Eq. (1) of observed data

and the associated PCs Ak from a data set, it is

necessary to minimize the error made in the representation by means of the expansion of Eq. (1) of observed data ![]() ,

this error

,

this error ![]() can be defined as the sum over all is and js of the squared differences between observed and estimated data, given by

can be defined as the sum over all is and js of the squared differences between observed and estimated data, given by

Since we are looking for a number of components able to describe completely the observed variable, one additional assumption is that the EOFs

where

Here

From Eq. (3), which is the well-known secular equation, it is possible to estimate the eigenvalues

We note that the NOC technique is strictly valid for spatio-temporal signals caused by the linear superposition of independent modes. Consequently, the interpretation of results of its application to spatio-temporal signals produced by nonlinear processes could be either difficult or doubtful owing to the approximation of the nonlinear interaction of independent modes with their linear combination.

3 Data description and results

3.1 Data and NOC analysis

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm]{11074f01.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/42/aa11074-08/Timg49.png)

|

Figure 1:

The sunspot area butterfly diagram from RGO/USAF/NOAA starting on May, 1874. The color

(black-red-yellow) is proportional to the sunspot area that is plotted as a function of time (Carrington rotation number

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

To investigate the occurrence of spatio-temporal complexity in the 11-year solar activity cycle,

we consider the total sunspot area butterfly diagram (see Fig. 1),

compiled from Royal

Greenwich Observatory and USAF Solar Optical Observing Network

observations and available at the NASA Solar Physics Marshall Space

Flight Center![]() .

The butterfly diagram is,

indeed, the only spatio-temporal dataset that, spanning over more than

12 solar cycles,

can be considered sufficiently long to apply the NOC analysis, which

requires a set of temporal snapshots (here 1759 Carrington rotations)

larger in number than the total number of spatial observations (here 50

latitudinal bins). The butterfly diagram

.

The butterfly diagram is,

indeed, the only spatio-temporal dataset that, spanning over more than

12 solar cycles,

can be considered sufficiently long to apply the NOC analysis, which

requires a set of temporal snapshots (here 1759 Carrington rotations)

larger in number than the total number of spatial observations (here 50

latitudinal bins). The butterfly diagram

![]() refers to the latitudinal (x) and temporal (t)

distribution of the sunspot areas in units of millionths of a

hemisphere since May, 1874. Data, representing the total sunspot area,

are organized in 50 latitude bins per Carrington rotation (

refers to the latitudinal (x) and temporal (t)

distribution of the sunspot areas in units of millionths of a

hemisphere since May, 1874. Data, representing the total sunspot area,

are organized in 50 latitude bins per Carrington rotation (![]() 27.28 days). The latitude bin locations are uniformly distributed with respect to

27.28 days). The latitude bin locations are uniformly distributed with respect to

![]() ,

where

,

where ![]() is the latitude (i.e.,

is the latitude (i.e.,

![]() ), while the temporal window spreads over 1759 Carrington rotations. The

sunspot butterfly diagram data used in this work was compiled following RGO/USAF/NOAA

instructions1 for data after 1976, which requires to increase USAF/NOAA spot areas by a factor of 1.4.

), while the temporal window spreads over 1759 Carrington rotations. The

sunspot butterfly diagram data used in this work was compiled following RGO/USAF/NOAA

instructions1 for data after 1976, which requires to increase USAF/NOAA spot areas by a factor of 1.4.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm,clip]{11074f02.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/42/aa11074-08/Timg53.png)

|

Figure 2:

The eigenvalue |

| Open with DEXTER | |

According to the previous section describing the NOC technique, to find the EOFs and

their associated PCs, it is necessary to solve the secular equation of Eq. (3), where ![]() is the

covariance matrix, compiled from the spatio-temporal dataset, which is a

is the

covariance matrix, compiled from the spatio-temporal dataset, which is a

![]() matrix (of 50 latitudinal bins) with elements given by

matrix (of 50 latitudinal bins) with elements given by

![]() .

All calculations were performed by utilizing user-defined macros within

a commercially available data analysis software (Igor Pro,

WaveMetrics).

.

All calculations were performed by utilizing user-defined macros within

a commercially available data analysis software (Igor Pro,

WaveMetrics).

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=17cm,clip]{11074f03.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/42/aa11074-08/Timg56.png)

|

Figure 3: The first six empirical orthogonal functions (EOFs) ordered according to the eigenvalue spectrum. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=17cm,clip]{11074f04.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/42/aa11074-08/Timg57.png)

|

Figure 4: The first six principal components (PCs) corresponding to the EOFs reported in Fig. 3, and describing the temporal evolution of the EOFs. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=17cm,clip]{11074f05.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/42/aa11074-08/Timg58.png)

|

Figure 5: The Fourier power spectra of the first six PCs. The vertical dotted lines indicate the 10.9 yr characteristic period of solar activity cycle. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Figure 2 shows the eigenvalue ![]() spectrum evaluated from the secular equation of Eq. (3).

Two different physical regimes are identifiable for k below and above k=3. In particular, the

first eigenvalue is larger by 4 times than the second, and 5 times than the third. The other

eigenvalues monotonically decrease for increasing k, exhibiting a cut-off for k > 18. Because this

spectrum can be considered as the equivalent of an energy spectrum, and is associated with the

variance of the various components, we can assume that most of the variability observed in the solar

cycle can be explained in terms of a very small number of components (

spectrum evaluated from the secular equation of Eq. (3).

Two different physical regimes are identifiable for k below and above k=3. In particular, the

first eigenvalue is larger by 4 times than the second, and 5 times than the third. The other

eigenvalues monotonically decrease for increasing k, exhibiting a cut-off for k > 18. Because this

spectrum can be considered as the equivalent of an energy spectrum, and is associated with the

variance of the various components, we can assume that most of the variability observed in the solar

cycle can be explained in terms of a very small number of components (![]() ).

).

Figures 3 and 4 show the first six EOFs and the corresponding PCs. These functions provide,

respectively, the latitudinal dependence (EOF

![]() )

and the time variation (PC

)

and the time variation (PC

![]() )

in the modes, ordered according to the eigenvalue spectrum

)

in the modes, ordered according to the eigenvalue spectrum ![]() .

Looking at

the structures of the EOFs, one can immediately note the inherent symmetry of these EOFs. This is

particularly evident for the EOFs with k=1, 2, which are symmetric with respect to the equator

(even-parity), thus resembling the symmetry observed in the butterfly diagram. In contrast, the

EOF with k=3 is antisymmetric (odd-parity) with respect to the equator. The symmetry features are less

evident with increasing k

and may take into account the so-called north-south asymmetries

(Sokoloff & Nesme-Ribes 1994). We note that, although all of the

features of the PCs seem to be characterized by a nearly cyclic

behavior resembling the solar activity cycle, they

have different intermittency degrees. We find that the kurtosis excess

.

Looking at

the structures of the EOFs, one can immediately note the inherent symmetry of these EOFs. This is

particularly evident for the EOFs with k=1, 2, which are symmetric with respect to the equator

(even-parity), thus resembling the symmetry observed in the butterfly diagram. In contrast, the

EOF with k=3 is antisymmetric (odd-parity) with respect to the equator. The symmetry features are less

evident with increasing k

and may take into account the so-called north-south asymmetries

(Sokoloff & Nesme-Ribes 1994). We note that, although all of the

features of the PCs seem to be characterized by a nearly cyclic

behavior resembling the solar activity cycle, they

have different intermittency degrees. We find that the kurtosis excess

![]() ,

which indicates the deviation from Gaussianity, is

,

which indicates the deviation from Gaussianity, is

![]() and

and

![]() for the first two PCs and for the remainder, respectively.

for the first two PCs and for the remainder, respectively.

To characterize the cyclic behavior of the PCs and find evidence of intrinsic periodicities, we

evaluate the Fourier power spectra of the Ak(t) for the first six modes. These spectra are shown in

Fig. 5, where it is possible to note that the periodic structure of the solar cycle

is due mainly to only the first two EOFs and PCs. As a matter of fact, only the spectra of the first two

PCs display a distinctive periodicity at

![]() (10.9) yr. A secondary, less apparent periodicity

(

(10.9) yr. A secondary, less apparent periodicity

(

![]() yr) is found in correspondence of the second harmonic (

yr) is found in correspondence of the second harmonic (

![]() ).

None of the

spectra of the other PCs exhibit any clear periodicity. We remark that,

while the first periodicity agrees with that found by the previous

analyses of the solar magnetic cycle (Mininni et al. 2002, 2004; Lawrence et al. 2005), the periodicity at T2is detected only by studying the 11-year cycle. Furthermore, the 7-year periodicity found by Mininni et al.

(2002, 2004) is not evident in our analysis.

).

None of the

spectra of the other PCs exhibit any clear periodicity. We remark that,

while the first periodicity agrees with that found by the previous

analyses of the solar magnetic cycle (Mininni et al. 2002, 2004; Lawrence et al. 2005), the periodicity at T2is detected only by studying the 11-year cycle. Furthermore, the 7-year periodicity found by Mininni et al.

(2002, 2004) is not evident in our analysis.

Figure 6 shows a reconstruction of the butterfly diagram using only the first two modes.

Although the reconstructed diagram qualitatively agrees with the observed behavior, on deeper

investigation, we note that the high variability, complexity, and stochasticity observed in

the solar cycle are missing. This is clearly evident when the reconstructed diagram is compared to the

original one for a single Carrington rotation (see Fig. 7). Evaluating the variability in the solar cycle, we find that the ratio ![]() of the butterfly diagram variance

of the butterfly diagram variance

![]() to that of the reconstructed butterfly

to that of the reconstructed butterfly

![]() with k=2 is

with k=2 is ![]() 0.4. This means that the first two modes only take into account 40% of the solar cycle variability.

0.4. This means that the first two modes only take into account 40% of the solar cycle variability.

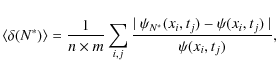

Since we aim to investigate the chaotic/stochastic features

of the solar activity cycle and to discuss them in terms of

spatio-temporal and/or dynamical complexity, we must determine the

minimum number of modes required to reconstruct the butterfly diagram

without losing relevant information about the solar cycle. This can be

achieved by studying the average error

![]() as a function of the truncation order N* of the reconstructed butterfly

diagram (see Eq. (6)), defined by

as a function of the truncation order N* of the reconstructed butterfly

diagram (see Eq. (6)), defined by

where

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm,clip]{11074f06.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/42/aa11074-08/Timg78.png)

|

Figure 6: The butterfly diagram reconstructed according to Eq. (6) using only the first two modes. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm,clip]{11074f07.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/42/aa11074-08/Timg79.png)

|

Figure 7: A comparison between the true sunspot area latitudinal profile (black circles) and the profiles corresponding to the butterfly diagram reconstructed with only two modes (solid line) and with 28 modes (dotted line) for the Carrington rotation t=1375. Area is measured in units of millionths of a hemisphere. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm,clip]{11074f08.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/42/aa11074-08/Timg80.png)

|

Figure 8:

The average truncation error

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

3.2 Chaotic features of PCs

After having looked at the spectral properties of NOC components and having established the proper number of modes to take into account, we move now to the analysis of the first two PCs.

In Figs. 9 and 10, we display the two plain projections of the phase portrait as reconstructed using A2(t) versus A1(t), and A4(t) versus A3(t), respectively. By smoothing the trajectories over a time window ![]()

![]() of solar cycle length, it is possible to differentiate between the nature of

the first two PCs from the others. While no evidence of a regular temporal structure is found in the A4(t) - A3(t) projection, the smoothed trajectory of A2(t) versus A1(t)

exhibits a certain degree of order, as shown by the existence of cyclic

oscillations. The spread in the smoothed trajectories in the

[ A2(t),A1(t)]

plane projection of the phase portrait suggests that chaos and/or

stochasticity may play an important role in the dynamics of sunspot

cycle. Furthermore, the first two PCs show a phase lag (time shift) of

of solar cycle length, it is possible to differentiate between the nature of

the first two PCs from the others. While no evidence of a regular temporal structure is found in the A4(t) - A3(t) projection, the smoothed trajectory of A2(t) versus A1(t)

exhibits a certain degree of order, as shown by the existence of cyclic

oscillations. The spread in the smoothed trajectories in the

[ A2(t),A1(t)]

plane projection of the phase portrait suggests that chaos and/or

stochasticity may play an important role in the dynamics of sunspot

cycle. Furthermore, the first two PCs show a phase lag (time shift) of ![]() 2.4 yr (

2.4 yr (![]()

![]() of solar cycle) when the cross-correlation function is investigated (data not shown).

of solar cycle) when the cross-correlation function is investigated (data not shown).

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm,clip]{11074f09.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/42/aa11074-08/Timg82.png)

|

Figure 9:

The |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm,clip]{11074f10.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/42/aa11074-08/Timg83.png)

|

Figure 10:

The |

| Open with DEXTER | |

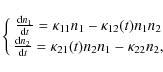

To clarify the nature of these sustained oscillations obtained in the case of the smoothed trajectory of A2(t) versus A1(t), we considered a stochastic Lotka-Volterra model (Haken 1983). The Lotka-Volterra (or predator-prey)

model describes the dynamics of two coupled variables, which evolves

towards a rhythmic behavior for certain initial conditions. The

Lotka-Volterra set of equations provides a very simple model for the

emergence of sustained oscillations in open systems far from

equilibrium (as chemical systems with an overall diverging affinity),

as well as for the emergence of spontaneous self-organization (Demirel 2007).

Here, we considered a slightly modified version of this simple model,

where the coupling between the two variables contains a certain degree

of noise. If we indicate by

![]() the set of the time-dependent variables, it follows that

the set of the time-dependent variables, it follows that

where

The evolution of the two variables ni, as resulting from the integration of Eq. (8), has been reported in Fig. 11. With respect to the Lotka-Volterra standard model (see Haken 1983; Demirel 2007,

and references therein), the variables show a fluctuating amplitude

from one cycle to the other. This behavior resembles that of the solar

cycle, whose amplitude changes from one cycle to the other. However, in

spite of the stochasticity of the coupling constant

![]() ,

it is still possible to recover an average rhythmic behavior. This is shown in Fig. 12, where we plot the evolution of the stochastic Lotka-Volterra model in the n1 - n2 plane (phase-portrait).

,

it is still possible to recover an average rhythmic behavior. This is shown in Fig. 12, where we plot the evolution of the stochastic Lotka-Volterra model in the n1 - n2 plane (phase-portrait).

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm,clip]{11074f11.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/42/aa11074-08/Timg95.png)

|

Figure 11:

The behavior of the two variables |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm,clip]{11074f12.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/42/aa11074-08/Timg96.png)

|

Figure 12: The n1-n2 phase portrait evolution of the solution of Eq. (8). |

| Open with DEXTER | |

The parallel with the stochastic Lotka-Volterra model suggests that the main part of the solar cycle variability, described by the first two PCs, can be described in terms of two different sunspot populations, perhaps related to the two modes of the toroidal component of the solar magnetic field (Bigazzi & Ruzmaikin 2004).

To investigate the relevance of chaos and/or stochasticity to the

evolution of the EOFs described by the PCs, as well as of the solar

cycle itself, we used the Lyapunov exponents. The Lyapunov exponents

are related to the exponential divergence of nearby orbits in the phase

space and give both qualitative and quantitative information about the

dynamical behavior of the system. In particular, when at least one

Lyapunov exponent is positive, the system is said to be chaotic and

small uncertainties in the initial condition can on average increase.

For systems whose equations of motion are known, Lyapunov exponents can

be estimated quite directly, while their estimation from a finite set

of experimental data is a little more complicated. Here, the method

proposed by Wolf et al. (1985) was adopted that allows the

estimation of the largest positive Lyapunov exponent ![]() if it exists. Starting from the reconstruction of orbits in the phase

space, the method is based on monitoring the long-term evolution of the

distance between a single pair of orbits.

if it exists. Starting from the reconstruction of orbits in the phase

space, the method is based on monitoring the long-term evolution of the

distance between a single pair of orbits.

Table 1: Lyapunov exponents of PCs Ak up to k=18.

We estimated the Lyapunov exponents ![]() for the most energetic PCs Ak with

for the most energetic PCs Ak with

![]() .

Because of the significant variability in the short timescale

fluctuations, we had previously reduced the noise in each PC by

applying a simple 13-point moving average, thus filtering out

fluctuations below 1 yr. The obtained Lyapunov exponents

.

Because of the significant variability in the short timescale

fluctuations, we had previously reduced the noise in each PC by

applying a simple 13-point moving average, thus filtering out

fluctuations below 1 yr. The obtained Lyapunov exponents ![]() are reported in Table 1 up to k=18, i.e., to the k-value where the exponential decay of the eigenvalue

are reported in Table 1 up to k=18, i.e., to the k-value where the exponential decay of the eigenvalue ![]() spectrum (see Fig. 2)

breaks. The first evident result of this analysis is that we can

clearly identify two main families of PCs (and EOFs): the first,

consisting of the first two PCs, characterized by the same Lyapunov

exponent

spectrum (see Fig. 2)

breaks. The first evident result of this analysis is that we can

clearly identify two main families of PCs (and EOFs): the first,

consisting of the first two PCs, characterized by the same Lyapunov

exponent

![]() ,

and the second consisting of all other PCs (

,

and the second consisting of all other PCs (

![]() )

with an average Lyapunov exponent

)

with an average Lyapunov exponent

![]() .

.

For comparison with the previous analysis of the PCs (Ak),

we evaluated the Lyapunov exponent for the numerical solution of the

stochastic Lokta-Volterra model, finding for both variables

![]() ,

a value very similar to that found for the first two PCs.

,

a value very similar to that found for the first two PCs.

As a consequence of the results of the Lyapunov exponent analysis, we can conjecture that the two different families are related to different physical mechanisms. In particular, this analysis supports the idea that the solar cycle cannot be analogous to a self-sustained chaotic cycle (Letellier et al. 2006), but that turbulent (stochastic) fluctuations play a fundamental role in the overall evolution. In other words, the hypothesis that the solar cycle dynamics can be related to low-dimensional chaotic evolution seems to be reductive on the basis of the above results. However, we believe that these noisy fluctuations cannot be assumed to be a stochastic background (Mininni et al. 2002) but instead the result of the evolution of complex diffusive patterns (Lawrence et al. 2005). We return to this point in the following sections.

However, to characterize this point, we analyzed the trace of the spectral matrix Sij(f) of the PCs (Tr

![]() )

for the two different regimes (i=1,2 and i=[3, 18]). The results are reported in Fig. 13.

The trace of the spectral matrix for the first dynamical regime is

characterized mainly by a pronounced peak at the typical 11-yr

periodicity and other peaks close to its harmonics (up to 6),

while the trace of the spectral matrix for the second dynamical regime

shows a very peculiar peak at

)

for the two different regimes (i=1,2 and i=[3, 18]). The results are reported in Fig. 13.

The trace of the spectral matrix for the first dynamical regime is

characterized mainly by a pronounced peak at the typical 11-yr

periodicity and other peaks close to its harmonics (up to 6),

while the trace of the spectral matrix for the second dynamical regime

shows a very peculiar peak at

![]() yr-1 along with a nearly 11-yr modulation. The observed peculiar periodicity of

yr-1 along with a nearly 11-yr modulation. The observed peculiar periodicity of

![]() yr is in the same range of timescales associated with the quasi-biennial oscillation (

yr is in the same range of timescales associated with the quasi-biennial oscillation (![]() 2 yr), observed in many solar spectral lines and other activity indicators (see e.g., Benevolelenskaya 1998; Polygiannakis et al. 2003; Cadavid et al. 2005; Penza et al. 2006; Laurenza & Storini 2008).

2 yr), observed in many solar spectral lines and other activity indicators (see e.g., Benevolelenskaya 1998; Polygiannakis et al. 2003; Cadavid et al. 2005; Penza et al. 2006; Laurenza & Storini 2008).

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm,clip]{11074f13.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/42/aa11074-08/Timg122.png)

|

Figure 13:

The trace of the spectral matrix for the two dynamical regimes, i=1, 2 ( upper panel) and i=[3, 18] ( lower panel),

respectively. The dashed lines represent the 95% confidence levels.

Vertical dashed lines refers to the principal solar cycle periodicity

and its harmonics (up to 6). The arrow in the lower panel indicates a

peculiar peak at |

| Open with DEXTER | |

3.3 Information entropy and complexity

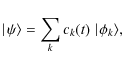

To investigate the emergence of spatio-temporal complexity in the solar cycle, we applied some simple concepts of information theory. In particular, moving from a simple parallelism between Eq. (6) and the evolution of states in quantomechanics, it is, indeed, possible to define a time-dependent probability of finding the system in a certain configuration. This is our starting point for the application of information theory. However, we begin by describing the above parallelism in detail.

In quantomechanics, the evolution of a certain state ![]()

![]() can be generally written as

can be generally written as

where ck(t) is the time-dependent probability amplitude associated with the eigenstate

where

Figure 14 shows the evolution of the probability pk(t) for the different phases of solar cycle 20. While in correspondence with the activity maximum, the dominant mode is the first mode, for solar minimum the higher modes (k >5) are more important. This suggests that the solar minimum has a more stochastic character and supports the occurrence of spatio-temporal complexity, which is caused by the competition between stochastic fluctuations and regular evolution.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm,clip]{11074f14.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/42/aa11074-08/Timg129.png)

|

Figure 14:

Evolution of the probability pk(t) (plotted as

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

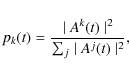

To characterize the long term evolution of the spatio-temporal complexity in the solar cycle with greater accuracy,

we move from the previous definition of a probability spectrum and apply the concepts of information

theory to investigate the degree of stochasticity in the solar cycle evolution. We evaluate

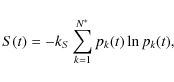

the Shannon's information entropy S(t) (Shannon 1948) defined to be

where kS is a constant assuming the role of the Boltzmann's constant that we have here assumed to be kS=1 for convenience. The entropy S(t), named also unconditional entropy or Boltzman-Gibbs-Shannon entropy, provides a measure of the information/uncertainty content in the probability spectrum, and is within the interval

Figure 15 shows the evolution of information entropy S(t)

for the solar activity

cycle evaluated using Eqs. (10) and (11), compared with the solar cycle

as measured by the sunspot hemispheric area coverage. Although S(t) is strongly variable (its average value

![]() is

is ![]() 2), the temporal behavior of the information entropy exhibits

a certain degree of anticorrelation with the solar activity cycle. The information entropy is

generally higher during solar minima than during maxima, reflecting the more noisy structure of

the butterfly diagram at solar minima. This anticorrelation is confirmed by the Pearson linear correlation coefficient (r =-0.44) between the smoothed S(t) and the sunspot coverage AT. Figure 16 shows the power spectral density (PSD) of the information entropy S(t).

The PSD has a more complex structure with respect to the single PCs,

showing many maxima emerging from the nearly-flat background of the

characteristic solar cycle periodicity and its harmonics. However, the

nearly-flat background (

2), the temporal behavior of the information entropy exhibits

a certain degree of anticorrelation with the solar activity cycle. The information entropy is

generally higher during solar minima than during maxima, reflecting the more noisy structure of

the butterfly diagram at solar minima. This anticorrelation is confirmed by the Pearson linear correlation coefficient (r =-0.44) between the smoothed S(t) and the sunspot coverage AT. Figure 16 shows the power spectral density (PSD) of the information entropy S(t).

The PSD has a more complex structure with respect to the single PCs,

showing many maxima emerging from the nearly-flat background of the

characteristic solar cycle periodicity and its harmonics. However, the

nearly-flat background (![]()

![]() with

with

![]() )

suggests that the stochastic fluctuations play a relevant role in the

spatio-temporal complexity displayed by the solar activity cycle.

)

suggests that the stochastic fluctuations play a relevant role in the

spatio-temporal complexity displayed by the solar activity cycle.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{11074f15.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/42/aa11074-08/Timg136.png)

|

Figure 15:

The evolution of the information entropy S(t)

for the solar activity cycle evaluated using

Eq. (11) in comparison with the solar activity cycle measured by

the sunspot hemispheric area coverage (dotted line). The solid black

line is a smoothed version of S(t) using a moving window of 37 Carrington

rotations (i.e., |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm,clip]{11074f16.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/42/aa11074-08/Timg137.png)

|

Figure 16:

The power spectral density (PSD) of the information entropy S(t). The dashed vertical line indicates the solar cycle characteristic period (

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

Although the information entropy is a useful quantity to provide insights into the

complex dynamics of a many degree-of-freedom system, a more accurate characterization of the

spatio-temporal complexity observed in a dynamical system could be given by the II order complexity measure

![]() introduced by Shiner et al. (1999; see also Crutchfield et al. 2000;

Binder & Perry 2000; and Shiner et al. 2000). From the definition of

the information entropy S(t), it is possible to define a disorder measure

introduced by Shiner et al. (1999; see also Crutchfield et al. 2000;

Binder & Perry 2000; and Shiner et al. 2000). From the definition of

the information entropy S(t), it is possible to define a disorder measure

![]() (Landsberg 1984) by simply normalizing the information entropy to the maximum

entropy

(Landsberg 1984) by simply normalizing the information entropy to the maximum

entropy

![]() ,

i.e.,

,

i.e.,

The disorder measure

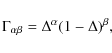

According to Shiner et al. (1999), it is possible to define a generalized II order

complexity measure

![]() to be

to be

among which a special role is played by the

The first step in estimating the

![]() complexity measure is the choice of the reference maximum

entropy

complexity measure is the choice of the reference maximum

entropy

![]() .

As this is a subtle point, we provide a careful discussion of this

choice. From the definition of the Shannon's information (see

Eq. (11)), it follows that the maximum entropy is attained by

considering an equiprobability situation. Thus, the simplest assumption

for the maximum entropy would be that

.

As this is a subtle point, we provide a careful discussion of this

choice. From the definition of the Shannon's information (see

Eq. (11)), it follows that the maximum entropy is attained by

considering an equiprobability situation. Thus, the simplest assumption

for the maximum entropy would be that

![]() ,

where

pk = 1/N*. This situation

corresponds to the case of an isolated (microcanonical) system based on

the assumption, as a postulate, of a uniform probability for all the

microstates corresponding to the same macrostate (Ben-Naim 2008).

Although this is a reasonable hypothesis, its applicability to the

solar cycle dynamics is questionable. In the case of solar cycle

dynamics, we deal with a nearly stationary nonequilibrium state, where

the assumption of equiprobability for the occupation number (state

amplitude) could lead to an overestimation of the reference maximum

entropy. This point is also corroborated by the assumption of Shiner

et al. (1999) of assuming

,

where

pk = 1/N*. This situation

corresponds to the case of an isolated (microcanonical) system based on

the assumption, as a postulate, of a uniform probability for all the

microstates corresponding to the same macrostate (Ben-Naim 2008).

Although this is a reasonable hypothesis, its applicability to the

solar cycle dynamics is questionable. In the case of solar cycle

dynamics, we deal with a nearly stationary nonequilibrium state, where

the assumption of equiprobability for the occupation number (state

amplitude) could lead to an overestimation of the reference maximum

entropy. This point is also corroborated by the assumption of Shiner

et al. (1999) of assuming

![]() to be the reference maximum entropy. In other words, we have to find a

way of defining a reasonable reference stationary distribution

to be the reference maximum entropy. In other words, we have to find a

way of defining a reasonable reference stationary distribution ![]() to be able to evaluate the reference maximum entropy.

to be able to evaluate the reference maximum entropy.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm,clip]{11074f17.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/42/aa11074-08/Timg149.png)

|

Figure 17:

The order k ( |

| Open with DEXTER | |

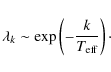

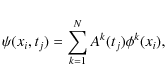

By looking at the eigenvalue ![]() spectrum (see Fig. 2), we can immediately realize that it is possible to define a reference

spectrum (see Fig. 2), we can immediately realize that it is possible to define a reference ![]() distribution by again using our parallelism with quantomechanics. By assuming that

distribution by again using our parallelism with quantomechanics. By assuming that ![]() is equivalent to the occupation number in the state

is equivalent to the occupation number in the state

![]() of energy

of energy

![]() ,

it is indeed possible to introduce an effective temperature

,

it is indeed possible to introduce an effective temperature

![]() and a reference nearly exponential distribution

and a reference nearly exponential distribution ![]() for the reference stationary state. Figure 17 shows

for the reference stationary state. Figure 17 shows

![]() versus the natural logarithm of the occupation number

versus the natural logarithm of the occupation number

![]() .

A linear region can be found in the interval range

.

A linear region can be found in the interval range

![]() ,

from which an effective temperature

,

from which an effective temperature

![]() (data not shown) can be estimated to be

(data not shown) can be estimated to be

Thus, for the reference distribution

where N* = 30. From the reference distribution

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm,clip]{11074f18.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/42/aa11074-08/Timg157.png)

|

Figure 18:

The II order complexity measure

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

Figure 18 shows the behavior of

![]() as a function of disorder

as a function of disorder ![]() for the solar cycle. We note that the most probable value of

for the solar cycle. We note that the most probable value of

![]() is

is ![]() 0.22 in correspondence to

0.22 in correspondence to

![]() ,

a value that clearly underlines how complexity plays a fundamental role

in the evolution of solar cycle. To associate complexity with the

different phases of the solar cycle more accurately in Fig. 19 we compare the complexity measure

,

a value that clearly underlines how complexity plays a fundamental role

in the evolution of solar cycle. To associate complexity with the

different phases of the solar cycle more accurately in Fig. 19 we compare the complexity measure

![]() ,

averaged over 37 Carrington solar rotations to reduce small-scale noise (see also Fig. 15)

and emphasize its mid-long term evolution with the corresponding solar

cycle, described by the total hemispheric sunspot coverage (AT).

Solar maxima correspond to complex states, while solar minima relate to

more disordered and less complex configurations. This result, inferred

from the existence of two different dynamical regimes/processes (as

shown in previous analyses), clearly suggests that the sunspot cycle is

the result of interacting processes in an open system.

,

averaged over 37 Carrington solar rotations to reduce small-scale noise (see also Fig. 15)

and emphasize its mid-long term evolution with the corresponding solar

cycle, described by the total hemispheric sunspot coverage (AT).

Solar maxima correspond to complex states, while solar minima relate to

more disordered and less complex configurations. This result, inferred

from the existence of two different dynamical regimes/processes (as

shown in previous analyses), clearly suggests that the sunspot cycle is

the result of interacting processes in an open system.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{11074f19.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/42/aa11074-08/Timg159.png)

|

Figure 19:

A comparison between the II order complexity measure

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

4 Summary and conclusions

We have focused our present study on the emergence of dynamical (spatio-temporal) complexity in the 11-yr solar cycle as monitored by the sunspot activity, by applying non-traditional approaches and techniques based on information theory. Although the global characteristics of the solar cycle are described well by dynamo theory, the origin of its complex irregularities remains unclear.

We decomposed the space-time distribution of sunspot areas over 1759

Carrington rotations by applying the natural orthogonal composition

technique, whose primary characteristics is the identification of the

most suitable set of basis orthogonal functions (the empirical

orthogonal functions - ![]() ). Results obtained by using this technique confirm previous findings of a

). Results obtained by using this technique confirm previous findings of a

![]() yr periodicity (found in the first two PCs), which characterizes the

long-term evolution of the solar cycle. A less prominent periodicity

was found to correspond to the second harmonic (

yr periodicity (found in the first two PCs), which characterizes the

long-term evolution of the solar cycle. A less prominent periodicity

was found to correspond to the second harmonic (![]() 5.5 yr). However, while the periodicity at T1 agrees with similar results for the solar magnetic cycle (Mininni et al. 2002,2004; Lawrence et al. 2005), the one at T2 emerges only after studying the 11-year cycle.

5.5 yr). However, while the periodicity at T1 agrees with similar results for the solar magnetic cycle (Mininni et al. 2002,2004; Lawrence et al. 2005), the one at T2 emerges only after studying the 11-year cycle.

Apart from the characteristic spectral features of the PCs, an

interesting point about the NOC results is that the main part of the

11-yr solar activity cycle can be described by two components (the

first two EOFs and the associated PCs) shifted in time by ![]() 2.4 yr (

2.4 yr (![]()

![]() of solar cycle) with respect to each other. The observed shift in time is in agreement with the phase shift (

of solar cycle) with respect to each other. The observed shift in time is in agreement with the phase shift (![]()

![]() )

between the m=0 and m=1

modes of the toroidal components of the magnetic field as observed in

numerical simulations of non-axisymmetric dynamo model with mean

helicity

)

between the m=0 and m=1

modes of the toroidal components of the magnetic field as observed in

numerical simulations of non-axisymmetric dynamo model with mean

helicity ![]() ,

located mostly above the tachocline (Bigazzi & Ruzmaikin 2004),

and taking into account that solar magnetic cycle periodicity is

expected to be twice that of the sunspot cycle. By inspecting the shape

of the first two EOFs, and in particular the latitudinal position of

their peaks, we note how the second EOF is mainly responsible for the

high latitude increase in the number of sunspot structures observed

during the early stages of the solar cycle, while the first EOF

describes mainly the nearly symmetric low latitude structures. This

result suggests that the solar activity cycle can be described by two

main interacting modes, whose character resembles the behavior of a

simple stochastic two populations Lotka-Volterra model. Again, the

spatial distribution of these first two EOFs, which are peaked at about

,

located mostly above the tachocline (Bigazzi & Ruzmaikin 2004),

and taking into account that solar magnetic cycle periodicity is

expected to be twice that of the sunspot cycle. By inspecting the shape

of the first two EOFs, and in particular the latitudinal position of

their peaks, we note how the second EOF is mainly responsible for the

high latitude increase in the number of sunspot structures observed

during the early stages of the solar cycle, while the first EOF

describes mainly the nearly symmetric low latitude structures. This

result suggests that the solar activity cycle can be described by two

main interacting modes, whose character resembles the behavior of a

simple stochastic two populations Lotka-Volterra model. Again, the

spatial distribution of these first two EOFs, which are peaked at about

![]() and

and

![]() latitude, resembles that of the first two modes of the field toroidal

component, which were found to be located at differently latitudes

(Bigazzi & Ruzmaikin 2004).

We believe that these two different fundamental modes, as monitored by

the first two EOFs, are manifestations of the first two modes of the

toroidal magnetic field component. We note that the observed time delay

of

latitude, resembles that of the first two modes of the field toroidal

component, which were found to be located at differently latitudes

(Bigazzi & Ruzmaikin 2004).

We believe that these two different fundamental modes, as monitored by

the first two EOFs, are manifestations of the first two modes of the

toroidal magnetic field component. We note that the observed time delay

of ![]() 2.4 yr corresponds to the same range of timescales characteristic of the so-called Gnevyshev gap (Storini et al. 2004).

This observation and since the second EOF mainly describes high

latitude structures and the second PC precedes the first, is in close

agreement with the pioneering observations of Gnevyshev (1963,1977), providing a possible origin of the observed gap.

2.4 yr corresponds to the same range of timescales characteristic of the so-called Gnevyshev gap (Storini et al. 2004).

This observation and since the second EOF mainly describes high

latitude structures and the second PC precedes the first, is in close

agreement with the pioneering observations of Gnevyshev (1963,1977), providing a possible origin of the observed gap.

Another interesting result obtained from the NOC analysis is the

dual character of the eigenvalue spectrum, which shows the existence of

two different regimes. This result, together with the two corresponding

families identified by the Lyapunov's exponents ![]() ,

allows us to conjecture that the solar cycle may be analogous to a

self-sustained chaotic cycle plus a certain amount of turbulent

fluctuations.

,

allows us to conjecture that the solar cycle may be analogous to a

self-sustained chaotic cycle plus a certain amount of turbulent

fluctuations.

Indeed, it has been shown (Hoyng et al. 1994) that in a simple axisymmetric mean-field dynamo, random ![]() -fluctuations

can account for several features of the observed solar cycle. In

particular, these random fluctuations, expected to arise from the

turbulent convection, are characterized by a correlation time much

shorter than any characteristic dynamo period. We believe that the

second regime in the eigenvalue spectrum could be a manifestation of

these random fluctuations in the

-fluctuations

can account for several features of the observed solar cycle. In

particular, these random fluctuations, expected to arise from the

turbulent convection, are characterized by a correlation time much

shorter than any characteristic dynamo period. We believe that the

second regime in the eigenvalue spectrum could be a manifestation of

these random fluctuations in the ![]() -effect.

This hypothesis is supported by the values of the Lyapunov exponents,

which are higher in the second regime than the first, therefore

implying a higher variability.

-effect.

This hypothesis is supported by the values of the Lyapunov exponents,

which are higher in the second regime than the first, therefore

implying a higher variability.

We note that the presence of two distinct dynamical regimes with different temporal (spectral) properties supports the hypothesis suggested by Benevolenskaya (1998,2000) of a double cycle characterized by different timescales. Benevolenskaya (1998,2000) suggested a double (dynamo) mechanism for the solar magnetic cycle, the first generated at the base of the convection zone by large-scale radial shear of the angular velocity and responsible for the 22-yr Hale's cycle and, thus, for the usual 11-yr activity cycle (Ruzmaikin 1996); the second due to latitudinal or radial shears in the subsurface regions. Although evidence of these two double mechanisms has been found, the 11-yr modulation in the spectrum of the second regime suggests that at the origin of the observed complexity there is a nonlinear coupling between the mechanisms.

The results obtained from the application of the information theory

approach to the solar cycle have emphasized the appearance of dynamical

complexity and indicated how complexity increases during the maximum

phases of the solar cycle. In particular, we have found that, in

correspondence to the solar maximum, the first two mode dominate over

the others, while towards solar minimum the higher modes become more

important. As already suggested by Mininni et al. (2002),

this could be interpreted in terms of a higher level of stochasticity

of the solar minimum competing with the regular evolution

characteristic of the solar maximum. However, the degree of

stochasticity observed during the solar minima never equals the maximum

value (

![]()

![]() ). This point supports the idea that the higher modes could be responsible for the evolution of complex diffuse field patterns as proposed by Lawrence et al. (2005). A quantitative estimation of the solar cycle complexity by a II order complexity measure (Shiner et al. 1999) confirmed the above scenario (

). This point supports the idea that the higher modes could be responsible for the evolution of complex diffuse field patterns as proposed by Lawrence et al. (2005). A quantitative estimation of the solar cycle complexity by a II order complexity measure (Shiner et al. 1999) confirmed the above scenario (

![]() and

and

![]() ).

On the basis of this result, the spatio-temporal variability

originating in the higher order modes could be the outcome of a

superficial turbulent dynamo process (i.e., of a highly complex

phenomenon) in the sunspot evolution and dynamics. Consequently, the

emergence of dynamical complexity excludes the hypothesis that the

solar cycle variability is caused by low-dimensional chaos (Letellier

et al. 2006) or pure

stochastic dynamics. However, we propose that the observations of

low-dimensional chaos in the sunspot cycle (Letellier et al. 2006)

could be the consequence of the use of coarse-grained descriptors (such

as the Wolf's sunspot number), which are unable to convey all the

information contained in spatio-temporal diagrams such as the butterfly

diagram. By limiting our attention to the first two modes (PCs), the

dynamics studied was found to agree with nearly low-dimensional chaotic

behavior, as emphasized by comparison with the stochastic

Lotka-Volterra model. Moreover, although in the past few solar cycles

the fluctuations in the information entropy S(t) have

increased in amplitude, we have not found clear evidence of an

increasing trend in this quantity with time. Thus, we cannot confirm

the previous findings by Sello (2000) of an increase in disorder from cycle

).

On the basis of this result, the spatio-temporal variability

originating in the higher order modes could be the outcome of a

superficial turbulent dynamo process (i.e., of a highly complex

phenomenon) in the sunspot evolution and dynamics. Consequently, the

emergence of dynamical complexity excludes the hypothesis that the

solar cycle variability is caused by low-dimensional chaos (Letellier

et al. 2006) or pure

stochastic dynamics. However, we propose that the observations of

low-dimensional chaos in the sunspot cycle (Letellier et al. 2006)

could be the consequence of the use of coarse-grained descriptors (such

as the Wolf's sunspot number), which are unable to convey all the

information contained in spatio-temporal diagrams such as the butterfly

diagram. By limiting our attention to the first two modes (PCs), the

dynamics studied was found to agree with nearly low-dimensional chaotic

behavior, as emphasized by comparison with the stochastic

Lotka-Volterra model. Moreover, although in the past few solar cycles

the fluctuations in the information entropy S(t) have

increased in amplitude, we have not found clear evidence of an

increasing trend in this quantity with time. Thus, we cannot confirm

the previous findings by Sello (2000) of an increase in disorder from cycle

![]() onwards. We believe that this difference could be caused mainly by the

different datasets and the different analysis techniques (wavelets

versus NOC). We also note that the last cycles are characterized by

larger fluctuations in the complexity measure.

onwards. We believe that this difference could be caused mainly by the

different datasets and the different analysis techniques (wavelets

versus NOC). We also note that the last cycles are characterized by

larger fluctuations in the complexity measure.

In summary, we have illustrated the complex nature of the solar cycle and pointed out that this complexity is probably caused by the nonlinear coupling of different processes.

AcknowledgementsThe Authors thank F. Berrilli, M. Laurenza, V. Penza and M. Materassi for valuable discussions and comments on this work. We acknowledge the NASA/Solar Physics Marshall Space Flight Center (http://Science.nasa.gov/ssl/pad/solar/greenwch.htm) for making available the data used in this work.

References

- Badii, R., & Politi, A. 1997, Complexity: hierarchical structures and scaling in physics (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press)

- Ben-Naim, A. 2008, A farewell to entropy: statistical thermodynamics based on information (Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd.)

- Benevolelenskaya, E. E. 1998, ApJ, 509, L49 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Benevolelenskaya, E. E. 2000, Sol. Phys., 191, 247 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Bigazzi, A., & Ruzmaikin, A 2004, ApJ, 604, 944 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Binder, P.-M., & Perry, N. 2000, Phys. Rev. E, 62, 2998 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Cadavid, A. C., Lawrence, J. K., McDonald, D. P., & Ruzmaikin, A. 2005, Sol. Phys., 226, 359 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T., Tam, S.W.Y., & Wu, C.-C. 2006, Space Sci. Rev., 122, 281 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Crutchfield, J. P., Feldman, D. P., & Rohilla Shalizi, C. 2000, Phys. Rev. E, 62, 2996 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Demirel, Y. 2007, Nonequilibrium thermodynamics, Transport and rate processes in physical, chemical and biological systems, edition (Amsterdam: Elsevier)

- Golovkov, V. P., Papitashvili, N. E., Tyupkin, Y. S., & Knarin, E. P. 1978, Geomag. & Aeron., 18, 511

- Golovkov, V. P., Papitashvili, V. O., & Papitashvili, N. E. 1989, Geomag. & Aeron., 29, 514

- Golovkov, V. P., Kozhoyeva, K. G., & Shkolnikova, S. I. 1992, Geomag. & Aeron. 32, 715

- Gnevyshev, M. N. 1963, Soviet Astron.-AJ, 7, 311 [NASA ADS]

- Gnevyshev, M. N. 1977, Sol. Phys., 51, 175 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Haken, H. 1983, Synergetics, an Introduction: Nonequilibrium Phase Transitions and Self-Organization in Physics, Chemistry, and Biology (New York: Springer-Verlag)

- Hoyng, P., Schmitt, D., & Teuben, L. J. W. 1994, A&A, 289, 265 [NASA ADS]

- Jackson, G. M., Mason, I. M., & Greenhalgh, S. A. 1991, Geomag. & Aeron., 56, 528

- Klimontovich, Yu. L. 1991, Turbulent Motion and the Structure of Chaos, A New Approach to the Statistical Theory of Open Systems (Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers)

- Klimontovich, Yu. L. 1996, Phys. Uspekhi, 39, 1169 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Landsberg, P. T. 1984, Phys. Lett., 102A, 171 [NASA ADS]

- Laurenza, M., & Storini, M. 2008, Mem. S.A.It., in press

- Lawrence, J. K., Cadavid, C., & Ruzmaikin, A. 2005, Sol. Phys., 225, 1 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Letellier, C., Aguirre, L. A., Maquet, J., et al. 2006, A&A, 449, 379 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences]

- Mininni, P. D., Gomez, D. O., & Mindlin, G. B. 2002, Phys. Rev. Lett., 89, 061101 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Mininni, P. D., López Fuentes, M., Mandrini, C. H., et al. 2004, Sol. Phys., 219, 367 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Nicolis, G., & Nicolis, C. 2007, Foundations of Complex Systems. Nonlinear Dynamics, Statistical Physics, Information and Prediction (Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd.)

- Penza, V., Pietropaolo, E., & Livingston, W. 2006, A&A, 454, 349 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences]

- Polygiannakis, J., Preka-Papadema, P., & Moussas, X. 2003, MNRAS, 343, 725 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Rotanova, N. M., Papitashvili, N. Ye., & Pushkov, A. N. 1982, Geomag. & Aeron., 22, 821

- Ruzmaikin, A. A. 1996, Geophys. Res. Lett., 23, 2649 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, C. E. 1948, Bell Syst. Tech. J., 27, 379

- Shiner, J. S., Davison, M., & Landsberg, P. T. 1999, Phys. Rev. E, 59, 1459 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Shiner, J. S., Davison, M., & Landsberg, P. T. 2000, Phys. Rev. E, 62, 3000 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Sello, S. 2000, A&A, 363, 311 [NASA ADS]

- Sokoloff, D., & Nesme-Ribes, E. 1994, A&A, 288, 293 [NASA ADS]

- Storini M., et al. 2004, Adv. Space Res., 31, 895 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Vecchio, A., Primavera, L., Carbone, V, et al. 2005, Sol. Phys., 229, 359 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.-Y. 2003, Geophys. J. Inter., 152, 613 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.-Y., & Kamide, Y. 2004, J.G.R., 109, A05218 [CrossRef]

- Wolf, A., Swift, J. B., Swinney, H. L., et al. 1985, Physica D, 16, 285 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

Footnotes

All Tables

Table 1: Lyapunov exponents of PCs Ak up to k=18.

All Figures

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm]{11074f01.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/42/aa11074-08/Timg49.png)

|

Figure 1:

The sunspot area butterfly diagram from RGO/USAF/NOAA starting on May, 1874. The color

(black-red-yellow) is proportional to the sunspot area that is plotted as a function of time (Carrington rotation number

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm,clip]{11074f02.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/42/aa11074-08/Timg53.png)

|

Figure 2:

The eigenvalue |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=17cm,clip]{11074f03.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/42/aa11074-08/Timg56.png)

|

Figure 3: The first six empirical orthogonal functions (EOFs) ordered according to the eigenvalue spectrum. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=17cm,clip]{11074f04.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/42/aa11074-08/Timg57.png)

|

Figure 4: The first six principal components (PCs) corresponding to the EOFs reported in Fig. 3, and describing the temporal evolution of the EOFs. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=17cm,clip]{11074f05.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/42/aa11074-08/Timg58.png)

|

Figure 5: The Fourier power spectra of the first six PCs. The vertical dotted lines indicate the 10.9 yr characteristic period of solar activity cycle. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm,clip]{11074f06.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/42/aa11074-08/Timg78.png)

|

Figure 6: The butterfly diagram reconstructed according to Eq. (6) using only the first two modes. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm,clip]{11074f07.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/42/aa11074-08/Timg79.png)

|

Figure 7: A comparison between the true sunspot area latitudinal profile (black circles) and the profiles corresponding to the butterfly diagram reconstructed with only two modes (solid line) and with 28 modes (dotted line) for the Carrington rotation t=1375. Area is measured in units of millionths of a hemisphere. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm,clip]{11074f08.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/42/aa11074-08/Timg80.png)

|

Figure 8:

The average truncation error

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm,clip]{11074f09.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/42/aa11074-08/Timg82.png)

|

Figure 9:

The |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm,clip]{11074f10.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/42/aa11074-08/Timg83.png)

|

Figure 10:

The |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm,clip]{11074f11.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/42/aa11074-08/Timg95.png)

|

Figure 11:

The behavior of the two variables |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm,clip]{11074f12.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/42/aa11074-08/Timg96.png)

|

Figure 12: The n1-n2 phase portrait evolution of the solution of Eq. (8). |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm,clip]{11074f13.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/42/aa11074-08/Timg122.png)

|

Figure 13:

The trace of the spectral matrix for the two dynamical regimes, i=1, 2 ( upper panel) and i=[3, 18] ( lower panel),

respectively. The dashed lines represent the 95% confidence levels.

Vertical dashed lines refers to the principal solar cycle periodicity

and its harmonics (up to 6). The arrow in the lower panel indicates a

peculiar peak at |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm,clip]{11074f14.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/42/aa11074-08/Timg129.png)

|

Figure 14:

Evolution of the probability pk(t) (plotted as

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{11074f15.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/42/aa11074-08/Timg136.png)

|

Figure 15:

The evolution of the information entropy S(t)

for the solar activity cycle evaluated using

Eq. (11) in comparison with the solar activity cycle measured by

the sunspot hemispheric area coverage (dotted line). The solid black

line is a smoothed version of S(t) using a moving window of 37 Carrington

rotations (i.e., |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm,clip]{11074f16.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/42/aa11074-08/Timg137.png)

|

Figure 16:

The power spectral density (PSD) of the information entropy S(t). The dashed vertical line indicates the solar cycle characteristic period (

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm,clip]{11074f17.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/42/aa11074-08/Timg149.png)

|

Figure 17:

The order k ( |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm,clip]{11074f18.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/42/aa11074-08/Timg157.png)

|

Figure 18:

The II order complexity measure

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{11074f19.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/42/aa11074-08/Timg159.png)

|

Figure 19:

A comparison between the II order complexity measure

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

Copyright ESO 2009

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.

![\begin{displaymath}\delta=\sum_{i=1}^m\sum_{j=1}^n \left[ \psi_{ij}-\sum_{k=1}^N a_j^k \phi_i^k \right]^2.

\end{displaymath}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/42/aa11074-08/img38.png)