| Issue |

A&A

Volume 506, Number 2, November I 2009

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Page(s) | 799 - 810 | |

| Section | Stellar structure and evolution | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/200810921 | |

| Published online | 18 August 2009 | |

A&A 506, 799-810 (2009)

The young, tight, and low-mass binary TWA22AB: a new calibrator for evolutionary models?![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

Orbit, spectral types, and temperature

M. Bonnefoy1 - G. Chauvin1 - C. Dumas2 - A.-M. Lagrange1 - H. Beust1 - M. Desort1 - R. Teixeira3 - C. Ducourant4 - J.-L. Beuzit1 - I. Song5

1 - Laboratoire d'Astrophysique de Grenoble,

BP 53, 38041 Grenoble Cedex 9, France

2 -

ESO, Alonso de Cordova 3107, Vitacura, Casilla 19001, Santiago 19, Chile

3 -

Instituto de Astronomia, Geofísica e Ciências Atmosféricas,

Universidade de São Paulo,

Rua do Matão, 1226 - Cidade Universitária,

05508-900 São Paulo - SP,

Brazil

4 -

Observatoire Aquitain des Sciences de l'Univers, CNRS-UMR 5804, BP 89, 33270 Floirac, France

5 -

Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602, USA

Received 5 September 2008 / Accepted 17 May 2009

Abstract

Context. Tight binaries discovered in young, nearby

associations are ideal targets for providing dynamical mass

measurements to test the physics of evolutionary models at young ages

and very low masses.

Aims. We report the binarity of TWA22 for the first time. We aim

at monitoring the orbit of this young and tight system to determine its

total dynamical mass using an accurate distance determination. We also

intend to characterize the physical properties (luminosity, effective

temperature, and surface gravity) of each component based on

near-infrared photometric and spectroscopic observations.

Methods. We used the adaptive-optics assisted imager NACO to

resolve the components, to monitor the complete orbit and to obtain the

relative near-infrared photometry of TWA22 AB. The adaptive-optics

assisted integral field spectrometer SINFONI was also used to obtain

medium-resolution (

![]() )

spectra in JHK bands.

Comparison with empirical and synthetic librairies were necessary for

deriving the spectral type, the effective temperature, and the surface

gravity for each component of the system.

)

spectra in JHK bands.

Comparison with empirical and synthetic librairies were necessary for

deriving the spectral type, the effective temperature, and the surface

gravity for each component of the system.

Results. Based on an accurate trigonometric distance (

![]() pc) determination, we infer a total dynamical mass of

pc) determination, we infer a total dynamical mass of

![]() for the system. From the complete set of spectra, we find an effective temperature

for the system. From the complete set of spectra, we find an effective temperature

![]() K for TWA22 A and

K for TWA22 A and

![]() K for TWA22 B and surface gravities between 4.0 and 5.5 dex. From our photometry and an M6

K for TWA22 B and surface gravities between 4.0 and 5.5 dex. From our photometry and an M6 ![]() 1 spectral type for both components, we find luminosities of log(

1 spectral type for both components, we find luminosities of log(

![]() dex and log(

dex and log(

![]() dex

for TWA22 A and B, respectively. By comparing these parameters with

evolutionary models, we question the age and the multiplicity of this

system. We also discuss a possible underestimation of the mass

predicted by evolutionary models for young stars close to the

substellar boundary.

dex

for TWA22 A and B, respectively. By comparing these parameters with

evolutionary models, we question the age and the multiplicity of this

system. We also discuss a possible underestimation of the mass

predicted by evolutionary models for young stars close to the

substellar boundary.

Key words: stars: fundamental parameters - stars: low-mass, brown dwarfs - binaries: close - stars: formation - instrumentation: adaptive optics - instrumentation: spectrographs

1 Introduction

Mass and age are fundamental parameters of stars and brown

dwarfs that determine their luminosity, effective temperature,

atmospheric composition, and surface gravity as commonly derived through

photometric and spectroscopic observations. Evolutionary models are

currently widely used in the community to infer masses of stars and

brown dwarfs, but they rely on equations of states and atmospheric

models that are not calibrated at young ages and at very low

masses. However, direct mass measurements

can be obtained by the means of different observing

techniques such as the astrometric follow-up of double-lined

spectroscopic tight binaries, the measurment of the Keplerian

motion of circumstellar disks or the joint use of light curve and radial velocity

on eclipsing binaries. In recent years, direct

mass measurements for 23 pre-main sequence stars with masses ranging

from 0.5 to 2 ![]() showed

discrepancies with predictions by up to a factor of 2 in mass and 10

in ages (Mathieu et al. 2007). Such measurements are rares for lower masses (

showed

discrepancies with predictions by up to a factor of 2 in mass and 10

in ages (Mathieu et al. 2007). Such measurements are rares for lower masses (![]()

![]() )

systems. Hillenbrand & White (2004) show that the

models tend to understimate the mass of the companion UZ Tau Eb

(

)

systems. Hillenbrand & White (2004) show that the

models tend to understimate the mass of the companion UZ Tau Eb

(

![]()

![]() ,

age

,

age ![]() 5 Myr, see Prato et al. 2002). Close et al. (2005) derived similar

conclusions, but the age and the luminosity of the companion

AB Dor C (

5 Myr, see Prato et al. 2002). Close et al. (2005) derived similar

conclusions, but the age and the luminosity of the companion

AB Dor C (

![]() ,

age

,

age ![]() 75 Myr) is still under

debate (Boccaletti et al. 2008). And recently, the surprising

discovery of the unpredicted temperature reversal

(Stassun et al. 2007) between 2M035 A (

75 Myr) is still under

debate (Boccaletti et al. 2008). And recently, the surprising

discovery of the unpredicted temperature reversal

(Stassun et al. 2007) between 2M035 A (

![]()

![]() ,

age

,

age ![]() 1 Myr) and its companion

(

1 Myr) and its companion

(

![]() ,

age

,

age ![]() 1 Myr) has proven the

necessity for finding more calibrators. The challenge is to unambiguously determine their physical properties (mass, L,

1 Myr) has proven the

necessity for finding more calibrators. The challenge is to unambiguously determine their physical properties (mass, L,

![]() ,

g, and age) and

to explore the parameter space covered by evolutionary models as much as possible. The influence of other parameters such as

metallicity also needs investigation (Boden et al. 2005; Burgasser 2007).

,

g, and age) and

to explore the parameter space covered by evolutionary models as much as possible. The influence of other parameters such as

metallicity also needs investigation (Boden et al. 2005; Burgasser 2007).

The TW Hydrae association (TWA) is the first co-moving group of young

(![]() 100 Myr), nearby (

100 Myr), nearby (![]() 100 pc) stars, to be

identified near the Sun (Kastner et al. 1997). Ideal

observational niche for studing stellar and planetary formation,

TWA was actually the tip of an iceberg composed of hundreds of young

stars, spread in different groups, which were identified during the

last decade (Torres et al. 2008; Zuckerman & Song 2004). TWA counts now 27 members covering a mass regime from intermediate-mass stars to

planetary mass objects (Chauvin et al. 2005). Its

100 pc) stars, to be

identified near the Sun (Kastner et al. 1997). Ideal

observational niche for studing stellar and planetary formation,

TWA was actually the tip of an iceberg composed of hundreds of young

stars, spread in different groups, which were identified during the

last decade (Torres et al. 2008; Zuckerman & Song 2004). TWA counts now 27 members covering a mass regime from intermediate-mass stars to

planetary mass objects (Chauvin et al. 2005). Its

![]() Myr dynamical age was found by a convergence method (de la Reza et al. 2006). Independently, Barrado Y Navascués (2006) estimated an age of

10+10-7 Myr from the photometry, the activity, and the lithium depletion. Scholz et al. (2007) show that the association is

9+8-2 Myr old by comparing rotational velocities with published rotation periods for a subset of stars. Finally, Men-tuch et al. (2008) estimate an age of

Myr dynamical age was found by a convergence method (de la Reza et al. 2006). Independently, Barrado Y Navascués (2006) estimated an age of

10+10-7 Myr from the photometry, the activity, and the lithium depletion. Scholz et al. (2007) show that the association is

9+8-2 Myr old by comparing rotational velocities with published rotation periods for a subset of stars. Finally, Men-tuch et al. (2008) estimate an age of ![]() Myr studing lithium depletion in five nearby young associations (hereafter M08).

Myr studing lithium depletion in five nearby young associations (hereafter M08).

Song et al. (2003), hereafter S03, identify TWA22 as an M5 member of TWA. The strong Li ![]() 6708 Å feature supported the extreme youth of this member. Later, Mamajek (2005) question the membership of TWA22 from a kinematic study of TW Hydrae members. Finally, Song et al. (2006) discuss the Mamajek (2005) results that appeared to disagree with the very strong lithium line of the source. The proximity (

6708 Å feature supported the extreme youth of this member. Later, Mamajek (2005) question the membership of TWA22 from a kinematic study of TW Hydrae members. Finally, Song et al. (2006) discuss the Mamajek (2005) results that appeared to disagree with the very strong lithium line of the source. The proximity (

![]() pc, see Teixeira et al. 2009)

and the reported youth of TWA22 by S03 made it consequently a potential

target for detecting companions at small orbital radii.

pc, see Teixeira et al. 2009)

and the reported youth of TWA22 by S03 made it consequently a potential

target for detecting companions at small orbital radii.

In our program for detecting companions in young associations

using the adaptive-optic (AO) assisted imager NACO, we resolved TWA22

as a tight (![]() 100 mas) binary. With a projected physical separation of

100 mas) binary. With a projected physical separation of

![]() AU (see Fig. 1),

this system offered a unique opportunity to measure its dynamical mass

and to possibly test the evolutionary model predictions at young ages

using combined photometric and spectroscopic observations.

AU (see Fig. 1),

this system offered a unique opportunity to measure its dynamical mass

and to possibly test the evolutionary model predictions at young ages

using combined photometric and spectroscopic observations.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=6cm,clip]{10921f01.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/41/aa10921-08/Timg36.png) |

Figure 1:

VLT/NACO image of TWA22 AB obtained in H-band with the

S13 camera on 2007 December 26. North is up and east is left. The field of view is

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

We report here the discovery of the TWA22 binarity and the results of a dedicated 4 years observing program, using combined imaging and 3D-spectroscopy with AO. The purpose was to measure the dynamical mass of TWA22 AB and to characterize the physical properties of the individual components. In Sect. 2, we describe our AO observations with the VLT/NACO imager and with the VLT/SINFONI integral field spectrograph. The associated data reduction and spectral extraction techniques are explained in Sect. 3. In Sect. 4, we present our orbital solutions and our spectral analysis. In Sect. 5 we compare and discuss the evolutionary model predictions associated to our dynamical mass measurement with the physical properties (surface gravity, temperature, and luminosity) derived from our photometric and spectroscopic observations. This leads us to discuss the membership of TWA22 AB to the TW Hydrae association, the multiplicty of the system, and a possible underestimation of the mass predicted by evolutionary models for young stars close to the substellar boundary.

2 Observations

2.1 VLT/NACO Observations

Table 1: Observing log.

TWA22 AB was observed at the 8.2 m VLT UT4 Yepun with the Nasmyth

Adaptive Optics (AO) System NAOS (Rousset et al. 2000) coupled to

the high-resolution near-IR camera CONICA

(Lenzen et al. 1998).

NAOS and CONICA (NACO) resolved the system as a tight binary for the

first time on March 5, 2004. Follow-up observations were

conducted during

four years from early 2004 to end 2007. To image TWA22 AB, we used

the narrow band filters: NB_1.24 (

![]() m,

m,

![]() m), NB_1.75 (

m), NB_1.75 (

![]() m,

m,

![]() m), and NB_2.17 (

m), and NB_2.17 (

![]() m,

m,

![]() m).

The broad band filters

J (

m).

The broad band filters

J (

![]() m,

m,

![]() m), H (

m), H (

![]() m,

m,

![]() m) and

m) and ![]() (

(

![]() m,

m,

![]() m) were also used coupled to a neutral density

(attenuation factor of 80). CONICA was used with the S13 and S27

cameras to Nyquist-sample the PSF depending on the selected

filter. The data were recorded under seeing that ranged from 0.6'' to 1.5'' (see Table 1). TWA22 AB was bright enough in the visible to be used by NAOS

for wavefront analysis. For each observation period, dithering around

the object in J, H, and

m) were also used coupled to a neutral density

(attenuation factor of 80). CONICA was used with the S13 and S27

cameras to Nyquist-sample the PSF depending on the selected

filter. The data were recorded under seeing that ranged from 0.6'' to 1.5'' (see Table 1). TWA22 AB was bright enough in the visible to be used by NAOS

for wavefront analysis. For each observation period, dithering around

the object in J, H, and ![]() bands combined with nodding were

needed to run a good sky estimation during the data reduction

process (see part 2.2). PSF references were observed at different

airmasses with identical setups. The

bands combined with nodding were

needed to run a good sky estimation during the data reduction

process (see part 2.2). PSF references were observed at different

airmasses with identical setups. The ![]() Ori C astrometric

field (McCaughrean & Stauffer 1994) was observed at each epoch to

calibrate the detector platescale and orientation whenever

necessary. The results are reported in Table 2.

Ori C astrometric

field (McCaughrean & Stauffer 1994) was observed at each epoch to

calibrate the detector platescale and orientation whenever

necessary. The results are reported in Table 2.

2.2 VLT/SINFONI observations

The SINFONI instrument (Spectrograph for INtegral Field Observations in

the Near Infrared),

located at the Cassegrain focus of the VLT UT4 Yepun, was used to

observe TWA22 AB between February 9 and 13, 2007.

SINFONI includes an integral field spectrometer SPIFFI (SPectrograph

for Infrared

Faint Field Imaging, Eisenhauer et al. 2003), operating in

the near-infrared (1.1-2.45 ![]() m). SPIFFI is assisted with the 60 actuators Multi-Applications Curvature Adaptive Optic system MACAO

(Bonnet et al. 2003). We used the small SPIFFI field of

view of

m). SPIFFI is assisted with the 60 actuators Multi-Applications Curvature Adaptive Optic system MACAO

(Bonnet et al. 2003). We used the small SPIFFI field of

view of

![]() corresponding to a plate scale of 25 mas per pixel to

Nyquist-sample the SINFONI AO corrected PSF. The field of view is

optically sliced into 32 horizontal slitlets that sample the horizontal spatial direction and that are rearranged to

form a pseudo-long slit. Once dispersed by the grating on the

corresponding to a plate scale of 25 mas per pixel to

Nyquist-sample the SINFONI AO corrected PSF. The field of view is

optically sliced into 32 horizontal slitlets that sample the horizontal spatial direction and that are rearranged to

form a pseudo-long slit. Once dispersed by the grating on the

![]() SPIFFI

detector, each slitlet of 64 pixels width (spatial direction)

corresponds to 64 spectra of 2048 pixels long (spectral

direction). The 2048 independent spectra on the detector are

reorganized during the reduction process in a

datacube that contains the spatial (X, Y) and the spectral (Z)

information. The cube is resampled in the vertical dimension (Y) to

have the same number of pixels as in X.

SPIFFI

detector, each slitlet of 64 pixels width (spatial direction)

corresponds to 64 spectra of 2048 pixels long (spectral

direction). The 2048 independent spectra on the detector are

reorganized during the reduction process in a

datacube that contains the spatial (X, Y) and the spectral (Z)

information. The cube is resampled in the vertical dimension (Y) to

have the same number of pixels as in X.

To cover the full spectral range between 1.1

to 2.45 ![]() m, individual integrations times of 90 s were necessary for imaging the system in the J

band (1.1-1.4

m, individual integrations times of 90 s were necessary for imaging the system in the J

band (1.1-1.4 ![]() m,

R=2000) and 20 s in the H+K band (

m,

R=2000) and 20 s in the H+K band (

![]() m, R=1500). For each band, dithering around the

object was used to increase the field of view and to suppress residual bad pixels, leading to a total observing

time on target of

m, R=1500). For each band, dithering around the

object was used to increase the field of view and to suppress residual bad pixels, leading to a total observing

time on target of ![]() 5 min. An additional frame was

acquired on the sky to improve our correction. The adaptive optic loop

was locked on TWA22 AB itself. Standard stars HIP038858 (B3V),

HIP049201 (B2V), HIP035208 (B3V), and HIP052202 (B4V) were observed at

similar airmasses to remove the telluric lines (see

Table 1).

5 min. An additional frame was

acquired on the sky to improve our correction. The adaptive optic loop

was locked on TWA22 AB itself. Standard stars HIP038858 (B3V),

HIP049201 (B2V), HIP035208 (B3V), and HIP052202 (B4V) were observed at

similar airmasses to remove the telluric lines (see

Table 1).

3 Data reduction and analysis

3.1 High-contrast imaging

Table 2: Mean plate scale and detector orientation for our different observing NACO runs.

For each observation period, the ESO eclipse reduction software (Devillard 1997) dedicated to AO image processing was used on the complete set of raw images. Eclipse computes bad-pixel detection and interpolation, flat-field correction, and averaging pairs of shifted images with sub-pixel accuracy. The software run sky estimation on object-dithered frames using median filtering through the frame sequence.A deconvolution algorithm dedicated to the stellar field blurred by the

adaptive-optics corrected point spread functions

(Veran & Rigaut 1998) was applied to TWA22 AB images to

accurately find the position and the photometry of the companion relative

to the primary. The algorithm is based on the minimization in the

Fourier domain of a regularized least square objective function using

the Levenberg-Marquardt method. We used Nyquist-sampled unsaturated

images of standard stars obtained the same night as TWA22 observations

with identical setups under various atmospheric conditions. These

frames captured the variation in AO corrections. They were used as

input point spread functions (PSF) to estimate the deconvolution

process error. The IDL Starfinder![]() PSF fitting

package (Diolaiti et al. 2000) confirmed these results.

PSF fitting

package (Diolaiti et al. 2000) confirmed these results.

3.2 Integral field spectroscopy

We used the SINFONI data reduction pipeline (1.7.1 version, see Modigliani et al. 2007) for raw data processing. The pipeline carries out cube reconstruction from raw detector images. The flagging of hot and non linear pixels is executed in a similar way to NACO images. The distortion and wavelength scale are calibrated on the entire detector using arc-lamp frames. Slitlet distances are accurately measured with north-south scanning of the detector illuminated with an optical fiber. In the case of standard stars observation, object-sky frame pairs are subtracted, flat-fielded, and corrected from bad pixels and distortions. Datacubes are finally reconstructed from clean science images and merged in a master cube. Spectra of standard stars cleaned from stellar lines are finally used to correct the TWA22 AB spectra from telluric absorptions.

TWA22 A and B are centered and oriented horizontally in the J and H+K

master cubes with a field of view of

![]() .

Atmospheric refraction induces different

sources positions for different wavelengths within the instrument

field of view and increases with airmass. Combined with the small

SINFONI field of view, this produces differential flux losses that were

noticed in the bright standard-star datacubes. This

effect remains limited for TWA22.

The cubes of February 11, 2007 appear to have some spectra contaminated

by flux oscillations of a few ADUs. These oscillations were not negligible and blurred CO

bands at 2.3

.

Atmospheric refraction induces different

sources positions for different wavelengths within the instrument

field of view and increases with airmass. Combined with the small

SINFONI field of view, this produces differential flux losses that were

noticed in the bright standard-star datacubes. This

effect remains limited for TWA22.

The cubes of February 11, 2007 appear to have some spectra contaminated

by flux oscillations of a few ADUs. These oscillations were not negligible and blurred CO

bands at 2.3 ![]() m. They are present along

the dispersion axis in the raw detector images of both HIP052202

and TWA22. Their amplitudes do not remain constant in time

but follow a 15.3 pixel period. We then filtered partially this contribution on each individual

image in the Fourier space using a pass-band function. The origin of

the problem is likely to be related to 50 Hz pick-up noise.

m. They are present along

the dispersion axis in the raw detector images of both HIP052202

and TWA22. Their amplitudes do not remain constant in time

but follow a 15.3 pixel period. We then filtered partially this contribution on each individual

image in the Fourier space using a pass-band function. The origin of

the problem is likely to be related to 50 Hz pick-up noise.

We used a modified version (Dumas et al. 2001) of the CLEAN algorithm (Högbom 1974; Schwartz 1978) to extract the flux of TWA22 A and B separately in each monochromatic image contained in the datacubes. The standard star is used for initial PSF-references. Once scaled to match the TWA22 A maximum at the primary position and for all wavelengths, the PSF is subtracted from the TWA22 AB datacube. The sequence is repeated to model the secondary contribution, cleaned from the primary wings, and to provide a new PSF-reference. After a few iterations minimizing the final quadratic residual datacube, the spectra of each individual component are extracted.

Table 3: Relative positions and contrasts of TWA22 A and B, with magnitude differences given in the NACO photometric system.

The algorithm was first adapted to work on cube images. Unfortunately, the difference of sampling between the X and Y directions limited the subpixel shift accuracy. We therefore collapsed the cube along the Y-axis to obtain the flux profile along the X direction. We chose to duplicate the primary flux profile for the PSF model. The algorithm converged in a few iterations and produced extracted spectra in J and H+K with an extraction error less than 5%. The extracted spectra were divided by standard star spectra corrected from intrinsic features and multiplied by a black body spectrum at the standard star temperature. The SINFONI pipeline coefficients were used for wavelength calibration.

4 Results

4.1 Astrometry, orbit and dynamical mass

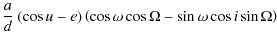

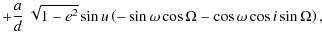

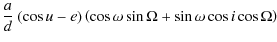

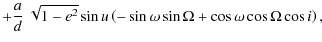

The relative positions of TWA 22 A and B (B with respect to A)

at all observation epochs are reported in

Table 3. The data allows determination of the

mutual orbit of the binary. We define a

cartesian referential frame (O,X,Y,Z) where X points towards the

north, Y toward the east, and Z toward the Earth. The (OXY) plane

thus corresponds to the plane of the sky. Then in a Keplerian

formalism, the projected position

![]() of the binary onto the plane

of the sky reads

of the binary onto the plane

of the sky reads

| x | = |  |

|

|

(1) | ||

| y | = |  |

|

|

(2) |

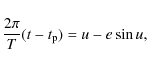

where a is the semi-major axis of the orbit (in AU), d the distance of the binary (in pc), e the eccentricity, i the inclination,

|

(3) |

where T is the orbital period and

The fit is performed via a Levenberg-Marquardt ![]() minimizing

algorithm. In practice, instead of

minimizing

algorithm. In practice, instead of

![]() ,

the

equations are solved for the classical variables

,

the

equations are solved for the classical variables

| (4) |

which avoids singularities towards small eccentricities and inclinations. The uncertainties on the fitted parameters are estimated from the resulting covariance matrix at the end of the fit procedure.

Levenberg-Marquardt is an interative gradient method for converging

towards a mininum of the ![]() function. Depending on the starting

guess point, many local minima can be found. In the present case,

all the attemps we made (by letting the starting point vary)

converge towards the same

solution that is listed in Table 4 and viewed in

projection onto the plane of the sky in Fig. 2. The

available astrometric data set appears to cover almost one complete

orbital period with a good sampling of the periastron passage. We are

thus confident in our fitted solution. The orbit then appears slighly

eccentric (

function. Depending on the starting

guess point, many local minima can be found. In the present case,

all the attemps we made (by letting the starting point vary)

converge towards the same

solution that is listed in Table 4 and viewed in

projection onto the plane of the sky in Fig. 2. The

available astrometric data set appears to cover almost one complete

orbital period with a good sampling of the periastron passage. We are

thus confident in our fitted solution. The orbit then appears slighly

eccentric (

![]() )

and viewed close to pole-on

)

and viewed close to pole-on

![]() from the Earth.

from the Earth.

Table 4:

TWA22 B orbital parameters as determined from the fit of the

astrometric data (see text for the definition of the parameters) with the reduced ![]() of the fit.

of the fit.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{10921f02.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/41/aa10921-08/Timg117.png) |

Figure 2: Orbital fit of the relative positions of TWA22 AB observed from March 2004 to December 2007, as projected onto the plane of the sky. The crosses represent the observational data with their error bars, the solid line is the fitted projected orbit, and the dots correspond to the predicted positions of the model at the times of the observations. The dashed line sketches the projected direction of the periastron of the orbit. On January 8, 2006, the binary was actually very close to periastron. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

4.2 Photometry

Table 3 summarizes

the magnitude differences between

TWA22 A and B, measured with NACO at different wavelengths.

Taking the filter tranformations between NACO and 2MASS and the

photometry of the unresolved system given from the 2MASS Survey

(Cutri et al. 2003) into account, we derived the apparent JHK magnitudes of

each component (see Table 5). Observations under bad

seeing conditions were excluded. Based on an accurate distance (

![]() pc) determination (Teixeira et al. 2009),

the absolute

magnitudes were also derived. Since TWA22 is a young mid-M system, we

monitored its photometric variations in the H band. We only noticed a

0.05 variation of the total magnitude of the system over time. This

variation is reported in the error bars on our photometry in Table 5.

pc) determination (Teixeira et al. 2009),

the absolute

magnitudes were also derived. Since TWA22 is a young mid-M system, we

monitored its photometric variations in the H band. We only noticed a

0.05 variation of the total magnitude of the system over time. This

variation is reported in the error bars on our photometry in Table 5.

Reported in a color (J-K)-magnitude (

![]() )

diagram, the TWA22 A and B photometry can be

compared with the photometry of M dwarfs (see Fig. 3) of the young, nearby

associations TW Hydrae (

)

diagram, the TWA22 A and B photometry can be

compared with the photometry of M dwarfs (see Fig. 3) of the young, nearby

associations TW Hydrae (![]() 8 Myr),

8 Myr), ![]() Pictoris (

Pictoris (![]() 12 Myr),

Tucana-Horologium (

12 Myr),

Tucana-Horologium (![]() 30 Myr) and AB Doradus

(

30 Myr) and AB Doradus

(![]() 70 Myr). At a given age, early-type M dwarfs are bluer and more luminous than late-type M dwarfs in the K band.

At a given spectral type (i.e. temperature), the objects go fainter

with age. Although age-dependent, the near-infrared photometry of

TWA22 A and B appears compatible for both components with what is

expected for young mid-M dwarfs but does not allow an age estimation

for the binary. Predictions of evolutionary models of (Baraffe et al. 1998,

named NEXTGEN) are also given at these young ages. The NEXTGEN tracks

appears bluer than 10 Myr old mid-M dwarfs by

70 Myr). At a given age, early-type M dwarfs are bluer and more luminous than late-type M dwarfs in the K band.

At a given spectral type (i.e. temperature), the objects go fainter

with age. Although age-dependent, the near-infrared photometry of

TWA22 A and B appears compatible for both components with what is

expected for young mid-M dwarfs but does not allow an age estimation

for the binary. Predictions of evolutionary models of (Baraffe et al. 1998,

named NEXTGEN) are also given at these young ages. The NEXTGEN tracks

appears bluer than 10 Myr old mid-M dwarfs by ![]() 0.2 mag,

which might be related to a partial representation of their spectral

energy distribution. At relatively warm temperatures, the remaining

incompleteness in the AMES linelists used in DUSTY atmospheric models (Mohanty et al. 2007) lead to J-Ks colors

redder than those observed for late-M dwarfs. The DUSTY evolutionary

tracks were then shifted by 0.2 mag to redder J-Ks. We provide in the following an improved estimation of the spectral type of our targets, using our spectroscopic data.

0.2 mag,

which might be related to a partial representation of their spectral

energy distribution. At relatively warm temperatures, the remaining

incompleteness in the AMES linelists used in DUSTY atmospheric models (Mohanty et al. 2007) lead to J-Ks colors

redder than those observed for late-M dwarfs. The DUSTY evolutionary

tracks were then shifted by 0.2 mag to redder J-Ks. We provide in the following an improved estimation of the spectral type of our targets, using our spectroscopic data.

Table 5: TWA22 A and B individual magnitudes converted into the 2MASS system.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{10921f03.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/41/aa10921-08/Timg119.png) |

Figure 3:

Color (J-K) - magnitude (MKs) diagram of

TWA22 A and B compared with the photometry of young M dwarfs

members of the TW Hydrae ( |

| Open with DEXTER | |

4.3 Spectroscopic analysis

4.3.1 Line identification

To identify the numerous spectral features in the TWA22 A and B

spectra between 1.10 to 2.45 ![]() m, the spectra were compared with an homogeneous

medium resolution (

m, the spectra were compared with an homogeneous

medium resolution (

![]() )

sequence of field dwarfs from Cushing et al. (2005) (hereafter C05; see Figs. 4-6). The TWA22 A and B spectra appear very similar.

)

sequence of field dwarfs from Cushing et al. (2005) (hereafter C05; see Figs. 4-6). The TWA22 A and B spectra appear very similar.

In J-band, both TWA22 A and B spectra are dominated by the strong Na I doublet at 1.138 ![]() m, the deep K I lines at 1.169, 1.177, 1.243,

and 1.253

m, the deep K I lines at 1.169, 1.177, 1.243,

and 1.253 ![]() m, and the presence of a broad H2O absorption from

1.32 to 1.35

m, and the presence of a broad H2O absorption from

1.32 to 1.35 ![]() m. Fe I absorptions are also detected around 1.170

m. Fe I absorptions are also detected around 1.170 ![]() m. One is blended with the 1.177

m. One is blended with the 1.177 ![]() m K I line. We notice additional broad

FeH absorptions around 1.20

m K I line. We notice additional broad

FeH absorptions around 1.20 ![]() m and 1.24

m and 1.24 ![]() m compatible with

what is expected for mid-M dwarfs as well as the presence of the weak Q-branch

at 1.22

m compatible with

what is expected for mid-M dwarfs as well as the presence of the weak Q-branch

at 1.22 ![]() m. Finally, the Al I doublet at 1.313

m. Finally, the Al I doublet at 1.313 ![]() m is

detected. This doublet is expected to disappear at the M-L transition.

m is

detected. This doublet is expected to disappear at the M-L transition.

In the H-band, the spectra are affected by H2O absorptions from 1.45

to 1.52 ![]() m and from 1.75 to 1.8

m and from 1.75 to 1.8 ![]() m. They exhibit pronounced K

I atomic lines at 1.517

m. They exhibit pronounced K

I atomic lines at 1.517 ![]() m, as well as weak doublets of Mg I at

1.503

m, as well as weak doublets of Mg I at

1.503 ![]() m and Al I at 1.675

m and Al I at 1.675 ![]() m. Weak FeH absorptions are also

present. They increase from M5 to the M-L transition

Cushing et al. (2003) and their depths are compatible here with those expected for

M5 to M7 field dwarfs.

m. Weak FeH absorptions are also

present. They increase from M5 to the M-L transition

Cushing et al. (2003) and their depths are compatible here with those expected for

M5 to M7 field dwarfs.

In K-band, strong H2O absorptions appear from 1.95 to 2.04 ![]() m

and from 2.3 to 2.45

m

and from 2.3 to 2.45 ![]() m. They are typical of mid-M to mid-L dwarfs. Strong

Ca I features are present from 1.9 to 2.0

m. They are typical of mid-M to mid-L dwarfs. Strong

Ca I features are present from 1.9 to 2.0 ![]() m. They tend to disappear

in the spectra of field dwarfs at the M-L transition. We firmly identify the first overtone of CO near 2.3

m. They tend to disappear

in the spectra of field dwarfs at the M-L transition. We firmly identify the first overtone of CO near 2.3 ![]() m, the rest being

affected by the 50 Hz pick-up noise oscillations mentioned earlier. Additional weak Mn I,

Ti I, Mg I and Si I absorptions are spread over the J, H, and K bands. These lines are expected to be rapidly replaced by molecular

absorptions for dwarfs later than M5. The 1.106

m, the rest being

affected by the 50 Hz pick-up noise oscillations mentioned earlier. Additional weak Mn I,

Ti I, Mg I and Si I absorptions are spread over the J, H, and K bands. These lines are expected to be rapidly replaced by molecular

absorptions for dwarfs later than M5. The 1.106 ![]() m band seems to

be overlapping H2O and TiO absorptions with increasing depths

from early to late M dwarfs. Finally, the 1.626

m band seems to

be overlapping H2O and TiO absorptions with increasing depths

from early to late M dwarfs. Finally, the 1.626 ![]() m feature

corresponds to close OH lines, as noted in Leggett et al. (1996).

m feature

corresponds to close OH lines, as noted in Leggett et al. (1996).

To conclude, the features detected over the spectra of TWA22 A and B between 1.1 and 2.45 ![]() m suggest that both components have a cool

atmosphere, typical of mid to late-M dwarfs.

m suggest that both components have a cool

atmosphere, typical of mid to late-M dwarfs.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=7.5cm,clip]{10921f04.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/41/aa10921-08/Timg121.png) |

Figure 4: TWA22 A and B spectra compared to spectra of M5 to M8 dwarfs. The M6 dwarf spectrum reproduces the J bands of TWA22 A and B. However, our spectra seem to have a slightly redder slope. We report identified atomic features (blue). Molecular absorptions (FeH bands were identified by Cushing et al. 2003) are flagged in green and telluric residuals in orange. Atomic absorptions are indicated in blue. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=7.5cm,clip]{10921f05.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/41/aa10921-08/Timg122.png) |

Figure 5: Same as Fig. 4 but for H band. In this case, differences between M6V field dwarf spectrum and TWA22 spectra are important. This could arise from low gravity or flux losses introduced either in the standard star datacube and during the extraction process. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=7.5cm,clip]{10921f06.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/41/aa10921-08/Timg123.png) |

Figure 6: Same as Fig. 4 but for the K band. Spectra look like an M6V field dwarf. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=7.5cm,clip]{10921f07.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/41/aa10921-08/Timg124.png) |

Figure 7: Comparison of the TWA22 B J band spectrum (red) to spectra (black) of young Upper Sco and Orion nebulae cluster objects (Slesnick et al. 2004; Lodieu et al. 2008). We clearly notice that the TWA22 B spectral slope is redder than that for reference spectra. The TWA22 B spectrum is very similar to those of young M6 and M7 dwarfs. We report identified atomic features (flagged in blue). Molecular absorptions (FeH bands were identified by Cushing et al. 2003) are flagged in green and telluric residuals in orange. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=7.5cm,clip]{10921f08.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/41/aa10921-08/Timg125.png) |

Figure 8: Comparison of the TWA22 B K band spectrum (red) to spectra of young Upper Sco standards (black) at R=350 (Gorlova et al. 2003). The TWA22 B spectrum was convolved with a Gaussian to match the resolution of standard star spectra. Our spectrum is reproduced by spectra of young M5.5 and M7 dwarfs. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

4.3.2 Continuum-fitting and spectral indexes

The continuum of both TWA22 A and B spectra were compared to spectra

of field M dwarfs obtained by C05 and McLean et al. (2003), hereafter

ML03. Least squares were computed on parts of the spectra free from telluric

correction residuals. From 1.10 ![]() m to 1.27

m to 1.27 ![]() m, the TWA22 A and

B continuums are reproduced by M6

m, the TWA22 A and

B continuums are reproduced by M6 ![]() 1 dwarfs. The H-band

spectra are poorly reproduced visually. Least squares are minimized

for M9 dwarfs but with 2 subclasses of uncertainty. Finally, our K-band

spectra are well-fitted by M5 to M7 dwarfs. From these comparisons, we

assign a spectral type M6

1 dwarfs. The H-band

spectra are poorly reproduced visually. Least squares are minimized

for M9 dwarfs but with 2 subclasses of uncertainty. Finally, our K-band

spectra are well-fitted by M5 to M7 dwarfs. From these comparisons, we

assign a spectral type M6 ![]() 1 to both TWA22 AB components.

1 to both TWA22 AB components.

Because TWA22 AB is a young system, we tested whether using high surface

gravity spectra of old field dwarfs might affect our spectral

analysis. Intermediate surface gravity reduces the strength of

alkali lines (Gorlova et al. 2003; Kirkpatrick et al. 2006; McGovern et al. 2004; Lucas et al. 2001) and produces triangular

shape in H-band interpreted as collision-induced absorptions (CIA) of

H2. Our spectra were then compared with young (age ![]() 8 Myr) dwarf

spectra (Gorlova et al. 2003; Slesnick et al. 2004; Lodieu et al. 2008) at identical resolution (spectra were convolved with a Gaussian if necessary) in the J and K bands (see Figs. 7 and 8).

They are mostly similar to M5, M5.5, M6, and M7 dwarf spectra, and

consistent with the continuum fit obtained with field dwarfs. In both

cases, our J-band spectra are slightly redder than young and old mid-M dwarfs. Our H-band

spectra are visually still poorly reproduced by our spectral templates.

This could arise from low gravity or flux losses introduced either in

the standard star datacube and during the extraction process.

8 Myr) dwarf

spectra (Gorlova et al. 2003; Slesnick et al. 2004; Lodieu et al. 2008) at identical resolution (spectra were convolved with a Gaussian if necessary) in the J and K bands (see Figs. 7 and 8).

They are mostly similar to M5, M5.5, M6, and M7 dwarf spectra, and

consistent with the continuum fit obtained with field dwarfs. In both

cases, our J-band spectra are slightly redder than young and old mid-M dwarfs. Our H-band

spectra are visually still poorly reproduced by our spectral templates.

This could arise from low gravity or flux losses introduced either in

the standard star datacube and during the extraction process.

To complete this spectral type determination, spectral indexes

developed by ML03 (from

![]() bands at 1.34

bands at 1.34 ![]() m (

m (

![]() ),

1.79

),

1.79 ![]() m (

m (

![]() ), 1.96

), 1.96 ![]() m (

m (

![]() ), and at 1.2

), and at 1.2 ![]() m

from the FeH band) were derived for TWA22 A and B (see Fig. 9). The results were

compared to the values computed from the ML03 and C05 spectral libraries

of field dwarfs. They were also compared to values derived for

young dwarfs (Slesnick et al. 2004; Lodieu et al. 2008, hereafter S04 and L08),

to test the sensitivity of these indexes to surface

gravity (age). In fact, The

m

from the FeH band) were derived for TWA22 A and B (see Fig. 9). The results were

compared to the values computed from the ML03 and C05 spectral libraries

of field dwarfs. They were also compared to values derived for

young dwarfs (Slesnick et al. 2004; Lodieu et al. 2008, hereafter S04 and L08),

to test the sensitivity of these indexes to surface

gravity (age). In fact, The

![]() D and FeH indexes values tend to

change with age for M5-L2 dwarf, and could disturb our analysis. We

then used a mean weight of the individual spectral type estimations

from

D and FeH indexes values tend to

change with age for M5-L2 dwarf, and could disturb our analysis. We

then used a mean weight of the individual spectral type estimations

from

![]() ,

,

![]() and the recently defined Allers

and the recently defined Allers

![]() index at 1.55

index at 1.55 ![]() m (see Allers et al. 2007) to infer

m (see Allers et al. 2007) to infer

![]() and

and

![]() spectral types for TWA22 A and B

respectively. These results match the

spectral types for TWA22 A and B

respectively. These results match the

![]() and

and

![]() values derived for TWA22 A and B from the

values derived for TWA22 A and B from the

![]() and FeH index

for the 2 objects. Based on the K-band photometry and the

associated bolometric corrections of Golimowski et al. (2004), we

derived a luminosity of

and FeH index

for the 2 objects. Based on the K-band photometry and the

associated bolometric corrections of Golimowski et al. (2004), we

derived a luminosity of

![]() dex for TWA22 A and

dex for TWA22 A and

![]() dex

TWA22 B. Using the

dex

TWA22 B. Using the

![]() -spectral type conversion scales for

intermediate-gravity objects (Luhman et al. 2003), we find an

initial estimation of

-spectral type conversion scales for

intermediate-gravity objects (Luhman et al. 2003), we find an

initial estimation of

![]() K for both

components.

K for both

components.

4.3.3 Study of narrow lines

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{10921f09.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/41/aa10921-08/Timg135.png) |

Figure 9:

H2O spectral indexes computed on libraries of

field (McLean et al. 2003; Cushing et al. 2005) and young dwarfs spectra (Slesnick et al. 2004; Lodieu et al. 2008). Redundancies between

libraries have been checked. Young dwarfs M4-L2 dwarfs follow trends of the field dwarfs except for H2O D. Using H2OA, H2OC, and the recently defined Allers H2O index at 1.55 |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Depths of many narrow lines were studied to provide additional information

on the surface gravity of TWA22 AB, particularly

on its age. Following the Sembach & Savage (1992) method for

measuring pseudo-equivalent widths and their associated uncertainties, we derived

the equivalent widths of strong atomic lines over the

J, H, and K bands. They were computed for narrow lines at 1.106 ![]() m (TiO and

m (TiO and

![]() ), 1.220

), 1.220 ![]() m (FeH - Q branch),

1.313

m (FeH - Q branch),

1.313 ![]() m (Al I), and 1.626

m (Al I), and 1.626 ![]() m (OH), and for

the K I doublets at 1.169, 1.177, 1.243 and 1.253

m (OH), and for

the K I doublets at 1.169, 1.177, 1.243 and 1.253 ![]() m. The

results were compared with pseudo-equivalent widths of old

field dwarfs (C05, ML03) and young Upper Sco dwarfs (S04,

L08). The use of both librairies confirmed the strong surface

gravity dependency of the K I lines, more moderate for the

Al I, FeH, and OH lines. Due to the degeneracy in terms of

effective temperature and surface gravity, pseudo-equivalent

widths alone are not sufficient for a precise spectral type determination

of TWA22 AB. They remain, however, compatible

with narrow lines depths of young and old dwarfs of spectral

types later than M4.

m. The

results were compared with pseudo-equivalent widths of old

field dwarfs (C05, ML03) and young Upper Sco dwarfs (S04,

L08). The use of both librairies confirmed the strong surface

gravity dependency of the K I lines, more moderate for the

Al I, FeH, and OH lines. Due to the degeneracy in terms of

effective temperature and surface gravity, pseudo-equivalent

widths alone are not sufficient for a precise spectral type determination

of TWA22 AB. They remain, however, compatible

with narrow lines depths of young and old dwarfs of spectral

types later than M4.

If we now assume a spectral type M6 ![]() 1 for both components, pseudo-equivalent widths in the K I lines of TWA22 AB appear intermediate between

values found for young and field dwarfs (see Fig. 10). This is confirmed using a

visual comparison with an evolutionary sequence of M6 dwarfs composed

of the old field dwarf GL 406, the intermediate old companion AB Doc C (Age 75 Myr, M5.5, Close et al. 2007), and a young M5.5 dwarf from the Orion nebulae (age

1 for both components, pseudo-equivalent widths in the K I lines of TWA22 AB appear intermediate between

values found for young and field dwarfs (see Fig. 10). This is confirmed using a

visual comparison with an evolutionary sequence of M6 dwarfs composed

of the old field dwarf GL 406, the intermediate old companion AB Doc C (Age 75 Myr, M5.5, Close et al. 2007), and a young M5.5 dwarf from the Orion nebulae (age ![]() 1-2 Myr, S04). Together with

the other age indicators, these intermediate surface gravity features

confirm that TWA22 AB is likely to be a young binary system. However,

their uncertainties remain large enough not to assign a precise

age.

1-2 Myr, S04). Together with

the other age indicators, these intermediate surface gravity features

confirm that TWA22 AB is likely to be a young binary system. However,

their uncertainties remain large enough not to assign a precise

age.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{10921f10.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/41/aa10921-08/Timg136.png) |

Figure 10:

Equivalent widths in the K I lines computed on libraries of young

and field dwarf spectra. Young dwarf spectra have weak K I lines

and therefore low equivalent widths compared to field dwarfs as a

consequence of their low surface gravity. TWA22 A and B values are

reported as red and green lines, respectively, with their associated

uncertainties (dashed lines). If we assume a spectral type M6 |

| Open with DEXTER | |

4.4 Gravity and effective temperature from atmospheric models

For a fine determination of the effective temperatures and surface

gravities of TWA22 A and B, we compared our observed spectra with

theoretical templates from the GAIA model v2.6.1

(Brott & Hauschildt 2005). This library is updated from

Allard et al. (2001). It benefits from improved molecular dissociation

constants, additional dust species with opacities, spherical symmetry,

and a mixing length parameter

![]() .

The temperature ranges in

the templates from 2000 to 10 000 K and the gravity from -0.5 to 5.5,

but we limited our analysis to

.

The temperature ranges in

the templates from 2000 to 10 000 K and the gravity from -0.5 to 5.5,

but we limited our analysis to

![]() K and

K and

![]() .

Theoretical spectra were convolved with a

Gaussian to match the SINFONI spectral resolution and interpolated to

the TWA22 AB wavelength grid. Least squares minimization was applied

to find templates that fit the TWA22 A and B continuum avoiding zones

polluted by remaining oscillations.

.

Theoretical spectra were convolved with a

Gaussian to match the SINFONI spectral resolution and interpolated to

the TWA22 AB wavelength grid. Least squares minimization was applied

to find templates that fit the TWA22 A and B continuum avoiding zones

polluted by remaining oscillations.

The TWA22 A least-square map in the J band constrains the temperature

between 2800 to 3100 K and is minimized for

![]() and

and

![]() K.

In H+K band, our

minimization failed to reproduce the TWA22 A spectra faithfuly and

makes us suspect the existence of a constant flux loss in the H band

during the spectral extraction process. To limit this systematic

effect, the minimization was applied separately in H and

K bands. In H-band, the effective temperature is

minimized between 2600 K to 3000 K in the full space of surface

gravities explored. The minimum is located at 2800 K and

K.

In H+K band, our

minimization failed to reproduce the TWA22 A spectra faithfuly and

makes us suspect the existence of a constant flux loss in the H band

during the spectral extraction process. To limit this systematic

effect, the minimization was applied separately in H and

K bands. In H-band, the effective temperature is

minimized between 2600 K to 3000 K in the full space of surface

gravities explored. The minimum is located at 2800 K and

![]() .

The K band is reproduced by 2900 and 3000 K

templates irrespective of gravity. Summing the three bands, we

estimate an effective temperature

.

The K band is reproduced by 2900 and 3000 K

templates irrespective of gravity. Summing the three bands, we

estimate an effective temperature

![]() K for

TWA22 A. Conducting a similar analysis for the component TWA22 B, we derive an

effective temperature

K for

TWA22 A. Conducting a similar analysis for the component TWA22 B, we derive an

effective temperature

![]() K. Using the Luhman et al. (2003) scale, these temperatures estimations respectively correspond to M7

+1-2 and M7

+0.5-2 spectral types for TWA22 A and B. This is also consistent with spectral types estimated in Sect. 4.3.2.

K. Using the Luhman et al. (2003) scale, these temperatures estimations respectively correspond to M7

+1-2 and M7

+0.5-2 spectral types for TWA22 A and B. This is also consistent with spectral types estimated in Sect. 4.3.2.

For a fine determination of the surface gravity from synthetic

spectra, we computed the equivalent widths of K I lines in the

J band on each spectra of TWA22 A and B. We then compared

the values to TWA22 A and B to restrain the acceptable gravity domain

(see Fig. 11). We then

estimated that the surface gravity is located between

![]() and 5.5 for TWA22 A and B.

and 5.5 for TWA22 A and B.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{10921f11.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/41/aa10921-08/Timg143.png) |

Figure 11: Iso-contours plots of K I lines equivalent widths computed on each spectral template of the GAIA library v2.6.1 Red color indicates high values. The contours for TWA22 A (red) and B (blue) pseudo-equivalents widths values are overplotted. The long-dashed lines represent limits on TWA22 A (red) and TWA22 B (blue) temperatures. Gravity is estimated inside these temperatures boxes. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

5 Discussion

5.1 Evolutionary models predictions

The membership of TWA22 AB to TW Hydrae constrains the age of the system to 3-20 Myr (Barrado Y Navascués 2006; Scholz et al. 2007; de la Reza et al. 2006). Based on our astrometric observations combined

with an accurate distance determination, we were able to derive the

dynamical mass of this tight binary. From photometry and spectroscopy,

we derived near-IR fluxes, luminosity, spectral type, effective

temperatures, and the surface gravity of each component. Finally,

spectroscopy tends to indicate that both components have intermediate

surface gravity features in their spectra, supporting a young age for

TWA22 AB. Assuming the TWA age for this system, we can now compare

the measured total dynamical mass of the binary with the total mass

predicted by evolutionary models of Baraffe et al. (1998; hereafter

BCAH98). Model predictions are based on the JHK photometry, the

luminosity and the effective temperature of both components (see Fig. 12). At 8 Myr, BCAH98 models systematically

underestimate the total mass by a factor of ![]() 2. This factor varies from 3 to 1.3 between 3-5 Myr and 20 Myr. The mass is still strongly under-estimated

using other evolutionary models of very low-mass stars

(D'Antona & Mazzitelli 1994,1997). Alternatively, if we

artificially change the system age to 30 Myr, the model predictions

match our observations relatively well.

2. This factor varies from 3 to 1.3 between 3-5 Myr and 20 Myr. The mass is still strongly under-estimated

using other evolutionary models of very low-mass stars

(D'Antona & Mazzitelli 1994,1997). Alternatively, if we

artificially change the system age to 30 Myr, the model predictions

match our observations relatively well.

The apparent discrepancy between our observations and the model predictions at the age of TWA leads us to consider four explanations:

- 1.

- remaining uncertainties are present in our data reduction and interpretation related to the astrometry, photometry, and spectroscopy extraction process, the atmosphere model used or the assumption on the system itself;

- 2.

- the system has higher multiplicity than observed;

- 3.

- evolutionary model predictions are correct and the age estimate of TWA22 AB is currently incorrect. TWA22 AB would then be slightly older and aged of 30 Myr;

- 4.

- finally, the TWA22 AB age is 8 Myr and evolutionary models themselves do not correctly predict the physical properties of very low-mass stars at young ages.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{10921f12.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/41/aa10921-08/Timg144.png) |

Figure 12: Top-left: comparison of the binary direct mass measurement for different TW Hydrae age estimations (Barrado Y Navascués 2006; Scholz et al. 2007; de la Reza et al. 2006) with the predicted masses of the BCAH98 tracks derived from MK. Errors on the photometry are propagated on predictions (dotted lines). Bottom-left: same as top-left but for predictions from MH. Top-right: same as top-left but for predictions from MJ. Bottom-right: Same as top-left but for predictions from our estimated TWA22 A/B luminosities. In this plan, predictions from BCAH98, D'Antona & Mazzitelli (1994), and D'Antona & Mazzitelli (1997) models are nearly the same within our uncertainties. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

5.2 Data reduction and interpretation uncertainties

Systematics on the estimation of the relative position and near-IR fluxes of TWA22 A and B seems very unlikely. Our analysis relies on several imaging analysis techniques (aperture photometry, PSF fitting, deconvolution), already used and tested in various contexts. The tight binary TWA22 AB does not itself represent a difficult case. In addition, at each epoch, consistent results were found on several observing sequences obtained during the night.

Systematics in the spectroscopic observation and extraction seem more probable for determining effective temperature and surface gravity. Differential flux losses over the J or H+K spectral range may have occurred because of the limited size of the SINFONI field of view. The impact of this effect can be simulated by adding a linear slope in our spectral minimization over the different spectral bands. The results do not change our analysis significantly based on continuum fitting or spectral indexes. It does not affect the study of narrow lines and our surface gravity estimation at all. A nonlinear differential flux loss could be responsible for our failure to faithfully reproduce the TWA22 A and B spectra in H-band using either empirical or synthetic libraries. Finally, the atmosphere models were also used in various conditions (metallicity, mixing length, different opacity tables) without drastically changing our results.

5.3 Higher multiplicity hypothesis

Considering that our data reduction and analysis are robust, we may wonder whether our basic assumptions concerning the system itself are correct. Actually, we cannot exclude from our observations that TWA22 AB is a multiple system of a higher order. One or even both components could be in fact unresolved binaries. In such a case, the derived effective temperatures, as well as the estimated spectral types, would not be strongly modified.

Dynamically speaking, the stability of the system would require the

separation of the individual subcomponents to be significantly less than

the size of the main orbit, typically by a factor 3-4 (Artymowicz & Lubow 1994).

To refine this estimate in the present case, we performed 3-body

simulations using the symplectic code HJS (Beust 2003) dedicated to

hierarchical systems. We assumed the fitted orbit and split one of

the two components into 2 equal mass bodies, with a coplanar orbit

with respect to the wide orbit and a given semi-major axis,

and assumed initial zero eccentricity. We find that the

system remains stable up to a separation of ![]()

![]() AU between the two subcomponents. This is a priori

the most stable configuration, because a split into unequal masses would

lead to less stability for the lighter component. We also checked that

highly inclined relative configurations are physically unstable: they inevitably lead to a strong

Kozai resonance characteristic for triple systems

(Beust et al. 1997; Kozai 1962) that cause

the eccentricity of the inner orbit to be pumped up to

AU between the two subcomponents. This is a priori

the most stable configuration, because a split into unequal masses would

lead to less stability for the lighter component. We also checked that

highly inclined relative configurations are physically unstable: they inevitably lead to a strong

Kozai resonance characteristic for triple systems

(Beust et al. 1997; Kozai 1962) that cause

the eccentricity of the inner orbit to be pumped up to ![]() 1,

leading to a physical collision between the two individual components.

Because of this, 0.4 AU can be considered as the widest possible

separation for

hypothetical sub-components. This agree with Artymowicz & Lubow (1994).

1,

leading to a physical collision between the two individual components.

Because of this, 0.4 AU can be considered as the widest possible

separation for

hypothetical sub-components. This agree with Artymowicz & Lubow (1994).

A separation of 0.4 AU (![]() 22 mas) remains below the PSF of the VLT/NACO images (

22 mas) remains below the PSF of the VLT/NACO images (![]() 1 AU

given the distance of TWA22). This would explain why the inner binary

would not be resolved. However, we did not notice any PSF-lengthening

in the images. With a separation of 0.4 AU, we could expect to see

one. Does it suggest that the actual separation is significantly smaller?

1 AU

given the distance of TWA22). This would explain why the inner binary

would not be resolved. However, we did not notice any PSF-lengthening

in the images. With a separation of 0.4 AU, we could expect to see

one. Does it suggest that the actual separation is significantly smaller?

An orbit with 0.4 AU separation would correspond to an orbital period

of 0.8 yr and a radial velocity wobble of ![]()

![]() if we take the

if we take the

![]() inclination

into account with respect to the plane of the sky.

Even though unlikely, this modulation could not have been detected

during the monitoring (split up into two periods of 6

and 1 months). But if we assume a separation of

inclination

into account with respect to the plane of the sky.

Even though unlikely, this modulation could not have been detected

during the monitoring (split up into two periods of 6

and 1 months). But if we assume a separation of ![]() 0.1 AU

to be compatible with the absence of PSF-lengthening, now the radial

velocity wobble jumps to

0.1 AU

to be compatible with the absence of PSF-lengthening, now the radial

velocity wobble jumps to ![]()

![]() over a 0.1 yr period. Such a variation was not detected in the radial velocity dataset (see Teixeira et al. 2009). Finally, no photocenter scatter is present around our two-body orbital solution. A motion of

over a 0.1 yr period. Such a variation was not detected in the radial velocity dataset (see Teixeira et al. 2009). Finally, no photocenter scatter is present around our two-body orbital solution. A motion of ![]() 5 mas is expected along the orbital period for a separation of

5 mas is expected along the orbital period for a separation of ![]() 0.1 AU between the subcomponents.

0.1 AU between the subcomponents.

Ultimately, we cannot definitely rule out the possibility that at least one of the two components of TWA22 is itself a binary, consisting of two nearly equal mass bodies. But combined dynamical and observational constraints show that the range of possible separations is fairly narrow, typically 0.1-0.2 AU. Also the system needs to be at least roughly coplanar.

5.4 Age and membership of TWA22 AB

Given the good agreement between observations and model predictions at 30 Myr, we can consider that the current age estimate of TWA22 AB is possibly incorrect. This age is currently inferred from the membership to TWA. Since the age of TWA is well established at 8 Myr from various age diagnostics, a reliable explanation concerns the membership to TWA itself.

S03 identified TWA22 as a new member of TWA mainly from the

observed Li absorption line at 6708 Å and H![]() emission line. The Li line

is stronger (EW=510 mÅ) than those of early-M dwarfs members of

emission line. The Li line

is stronger (EW=510 mÅ) than those of early-M dwarfs members of ![]() Pic, which led S03 to suggest an age

Pic, which led S03 to suggest an age ![]() 10 Myr (see Fig. 8 of S03). They derived in addition a photometric distance of 22 pc for

TWA22, confirming the proximity of this young system. More recently, Mamajek (2005) has discussed the membership of

TWA22 AB to TWA based on its kinematics

properties and estimates a probability of 2%

for TWA22 to be a member of TWA from an implemented convergence point

technique (de Bruijne 1999). However,

Song et al. (2006) mentioned that the strong Li line of

TWA22 AB is observed only for young active M dwarfs in the direction

of TWA with the exception of a very few M-type members of the

10 Myr (see Fig. 8 of S03). They derived in addition a photometric distance of 22 pc for

TWA22, confirming the proximity of this young system. More recently, Mamajek (2005) has discussed the membership of

TWA22 AB to TWA based on its kinematics

properties and estimates a probability of 2%

for TWA22 to be a member of TWA from an implemented convergence point

technique (de Bruijne 1999). However,

Song et al. (2006) mentioned that the strong Li line of

TWA22 AB is observed only for young active M dwarfs in the direction

of TWA with the exception of a very few M-type members of the ![]() Pictoris moving group (BPMG). Finally, Men-tuch et al. (2008)

obtained a new visible high-resolution spectrum of TWA22 AB. They

confirm the strong equivalent line of the 6708 Å lithium

absorption (

Pictoris moving group (BPMG). Finally, Men-tuch et al. (2008)

obtained a new visible high-resolution spectrum of TWA22 AB. They

confirm the strong equivalent line of the 6708 Å lithium

absorption (

![]() mÅ, the strongest measured in their sample composed of young association members). They estimate

mÅ, the strongest measured in their sample composed of young association members). They estimate

![]() of

of

![]() K (compatible with the individual

K (compatible with the individual

![]() derived in Part 4.4) and

derived in Part 4.4) and

![]() dex for the unresolved system. These new elements tend to confirm that TWA22 is a young system (age

dex for the unresolved system. These new elements tend to confirm that TWA22 is a young system (age ![]() 30 Myr; see BCAH98 predictions).

30 Myr; see BCAH98 predictions).

To reconcile past and present results, we can consider the possibility

that TWA22 AB is a member of the BPMG. With an

![]() spectral

type, TWA22 AB is probably close to the Li-depletion boundary (LDB) of

TWA or

spectral

type, TWA22 AB is probably close to the Li-depletion boundary (LDB) of

TWA or ![]() Pic, which could possibly explain a significantly stronger

EW(Li) than those observed for early-M dwarfs of these two

associations. We also notice that the

Pic, which could possibly explain a significantly stronger

EW(Li) than those observed for early-M dwarfs of these two

associations. We also notice that the ![]() 6708 Å line shows some variations between the S03 and M08 measurements. In addition, the observed EW(H

6708 Å line shows some variations between the S03 and M08 measurements. In addition, the observed EW(H![]() )

of TWA22, used as a second indicator of youth, is compatible with those of GJ799 A

and B, M4.5 members of

)

of TWA22, used as a second indicator of youth, is compatible with those of GJ799 A

and B, M4.5 members of ![]() Pic (Jayawardhana et al. 2006).

Pic (Jayawardhana et al. 2006).

Finally, the projected position of TWA22 AB reveals that the system is isolated from other members of TWA. Its distance is more compatible with the mean distance of the BPMG members. Teixeira et al. (2009) have recently measured the proper motion, the trigonometric parallax, and the mean radial velocity of TWA22 AB. They determined for the first time the heliocentric space motion of TWA22 AB. From a detailed kinematic analysis they did not rule out TWA22 from TW Hydrae but demonstrated that it was a more probable member of the BPMG.

6 Conclusions

NACO resolved for the first time the young object TWA

22 as a tight binary with a projected separation of 1.76 AU. 80% of

the binary orbit was covered during a 4-year observation program

conducted with this instrument. We inferred a

![]()

![]() total mass for the system and obtained the individual magnitudes of

each component in the near infrared. This places TWA22 A and B at the

substellar boundary. We complete the characterization of the system

components with medium resolution individual SINFONI spectra in the

J, H, and K bands. Our spectra were compared

with the empirical library of young and field M dwarfs. We derived an M6

total mass for the system and obtained the individual magnitudes of

each component in the near infrared. This places TWA22 A and B at the

substellar boundary. We complete the characterization of the system

components with medium resolution individual SINFONI spectra in the

J, H, and K bands. Our spectra were compared

with the empirical library of young and field M dwarfs. We derived an M6

![]() 1 spectral type from continuum fitting, spectral indexes and

equivalent widths. Spectral templates were also used to estimate

1 spectral type from continuum fitting, spectral indexes and

equivalent widths. Spectral templates were also used to estimate

![]() K for TWA22 A and

K for TWA22 A and

![]() K for TWA22 B, and the surface gravity was

constrained to

K for TWA22 B, and the surface gravity was

constrained to

![]() dex. These fundamental properties can be directly compared with commonly used

evolutionary tracks provided that the age of the system is known accurately.

dex. These fundamental properties can be directly compared with commonly used

evolutionary tracks provided that the age of the system is known accurately.

The age of TWA22 was still a matter of debate at the beginning of our study. TWA22 was reported as a member of the young association TW Hydrae, and alternatively as a possible member of the BPMG. At the age of TW Hydrae and BPMG, the new and precious benchmark brought by this system seems to point to an underestimation of the predicted mass from our photometry. However, the dynamical mass appears correctly estimated by the models if we consider a 30 Myr old system. This led us to reconsider the membership of TWA22.

While the spectroscopy tends to confirm the youth of this system, a recent kinematic study rejected TWA22 as a member of the TW Hydrae and of the 30 Myr old Tucana-Horologium associations. It did not exclude the membership of TWA22 to the BPMG. Also, we cannot rule out the possibility that TWA22 is not associated with any of these moving groups.

Finally, we do not firmly exclude that the TWA22 AB component could in fact be unresolved binaries with coplanar inner orbits characterized by semi-major axis lower than 0.4 AU. The model predictions would match the measured dynamical mass of a triple or quadruple system. In this context, future monitoring of TWA22 AB with improved angular resolution could allow the resolution of the hypothetical inner binaries.

AcknowledgementsWe thank the referee for an excellent and thorough review, which helped to improve our manuscript considerably. We thank the ESO Paranal staff for performing the service mode observations. We also acknowledge partial financial support from the Agence National de la Recherche and the Programmes Nationaux de Plantologie et de Physique Stellaire (PNP & PNPS), in France. We are grateful to Andreas Seifahrt, Laird Close, Eric Nielsen, Catherine L. Slesnick, Nadya Gorlova, Katelyne N. Allers, and Nicolas Lodieu for providing their spectra. This work would have not been possible without the NIRSPEC and UKIRT libraries provided by Ian S. McLean, Michael C. Cushing, and John T. Rayner. We also would like to thank Peter H. Hauschildt, France Allard, and Isabelle Baraffe for their input on evolutionary models and synthetic spectral libraries. Finally, we thank Carlos Torres, Michael Sterzik, and Ben Zuckerman, who gave use precious insights into the discussion.

References

- Allard, F., Hauschildt, P. H., Alexander, D. R., Tamanai, A., & Schweitzer, A. 2001, ApJ, 556, 357 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Allers, K. N., Jaffe, D. T., Luhman, K. L., et al. 2007, ApJ, 657, 511 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Artymowicz, P., & Lubow, S. H. 1994, ApJ, 421, 651 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Baraffe, I., Chabrier, G., Allard, F., & Hauschildt, P. H. 1998, A&A, 337, 403 [NASA ADS]

- Barrado Y Navascués, D. 2006, A&A, 459, 511 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences]

- Beust, H. 2003, A&A, 400, 1129 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences]

- Beust, H., Corporon, P., Siess, L., Forestini, M., & Lagrange, A.-M. 1997, A&A, 320, 478 [NASA ADS]

- Boccaletti, A., Chauvin, G., Baudoz, P., & Beuzit, J.-L. 2008, A&A, 482, 939 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences]

- Boden, A. F., Sargent, A. I., Akeson, R. L., et al. 2005, ApJ, 635, 442 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Bonnet, H., Ströbele, S., Biancat-Marchet, F., et al. 2003, in Adaptive Optical System Technologies II, ed. P. L. Wizinowich, & D. Bonaccini, Proc. SPIE, 4839, 329

- Brott, I., & Hauschildt, P. H. 2005, in The Three-Dimensional Universe with Gaia, ed. C. Turon, K. S. O'Flaherty, & M. A. C. Perryman, ESA SP, 576, 565

- Burgasser, A. J. 2007, AJ, 134, 1330 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Chabrier, G., Baraffe, I., Allard, F., & Hauschildt, P. 2000, ApJ, 542, 464 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Chauvin, G., Lagrange, A.-M., Dumas, C., et al. 2005, A&A, 438, L25 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences]

- Close, L. M., Lenzen, R., Guirado, J. C., et al. 2005, Nature, 433, 286 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Close, L. M., Thatte, N., Nielsen, E. L., et al. 2007, ApJ, 665, 736 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Cushing, M. C., Rayner, J. T., Davis, S. P., & Vacca, W. D. 2003, ApJ, 582, 1066 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Cushing, M. C., Rayner, J. T., & Vacca, W. D. 2005, ApJ, 623, 1115 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Cutri, R. M., Skrutskie, M. F., van Dyk, S., et al. 2003, 2MASS All Sky Catalog of point sources, The IRSA 2MASS All-Sky Point Source Catalog, NASA/IPAC Infrared Science Archive, http://irsa.ipac.caltech.edu/applications/Gator/

- D'Antona, F., & Mazzitelli, I. 1994, ApJS, 90, 467 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- D'Antona, F., & Mazzitelli, I. 1997, Mem. Soc. Astron. Ital., 68, 807 [NASA ADS]

- de Bruijne, J. H. J. 1999, MNRAS, 306, 381 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- de la Reza, R., Jilinski, E., & Ortega, V. G. 2006, AJ, 131, 2609 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Devillard, N. 1997, The Messenger, 87, 19 [NASA ADS]

- Diolaiti, E., Bendinelli, O., Bonaccini, D., et al. 2000, in Adaptive Optical Systems Technology, ed. P. L. Wizinowich, Proc. SPIE Vol., 4007, 879

- Dumas, C., Terrile, R. J., Brown, R. H., Schneider, G., & Smith, B. A. 2001, AJ, 121, 1163 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]