| Issue |

A&A

Volume 506, Number 1, October IV 2009

The CoRoT space mission: early results

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Page(s) | 359 - 367 | |

| Section | Planets and planetary systems | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/200912231 | |

| Published online | 02 July 2009 | |

The CoRoT space mission: early results

VLT transit and occultation photometry for the bloated planet CoRoT-1b![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png) ,

,![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

M. Gillon1,2 - B.-O. Demory2 - A. H. M. J. Triaud2 - T. Barman3 - L. Hebb4 - J. Montalbán1 - P. F. L. Maxted5 - D. Queloz2 - M. Deleuil6 - P. Magain1

1 - Institut d'Astrophysique et de Géophysique, Université de Liège, Allée du 6 Août 17, Bât. B5C, Liège 1, Belgium

2 - Observatoire de Genève, Université de Genève, 51 Chemin des Maillettes, 1290 Sauverny, Switzerland

3 - Lowell Observatory, 1400 West Mars Hill Road, Flagstaff, AZ 86001, USA

4 - School of Physics and Astronomy, University of St. Andrews, North Haugh, Fife, KY16 9SS, UK

5 - Astrophysics Group, Keele University, Staffordshire, ST5 5BG, UK

6 - Laboratoire d'Astrophysique de Marseille (UMR 6110), 38 rue Frédéric Joliot-Curie, 13388 Marseille, France

Received 30 March 2009 / Accepted 26 May 2009

Abstract

We present VLT eclipse photometry for the giant planet CoRoT-1b. We observed a transit in the R-band filter and an occultation in a narrow filter centered on 2.09 ![]() m. Our analysis of this new photometry and published radial velocities, in combination with stellar-evolutionary modeling, leads to a planetary mass and radius of 1.07

m. Our analysis of this new photometry and published radial velocities, in combination with stellar-evolutionary modeling, leads to a planetary mass and radius of 1.07

![]()

![]() and 1.45

and 1.45

![]()

![]() ,

confirming the very low density previously deduced from CoRoT photometry. The large occultation depth that we measure at 2.09

,

confirming the very low density previously deduced from CoRoT photometry. The large occultation depth that we measure at 2.09 ![]() m (0.278

m (0.278

![]() )

is consistent with thermal emission and is better reproduced by an atmospheric model with no redistribution of the absorbed stellar flux to the night side of the planet.

)

is consistent with thermal emission and is better reproduced by an atmospheric model with no redistribution of the absorbed stellar flux to the night side of the planet.

Key words: binaries: eclipsing - planetary systems - stars: individual: CoRoT-1 - infrared: stars - techniques: photometric - techniques: radial velocities

1 Introduction

Transiting planets play an important role in the study of planetary objects outside our solar system. Not only can we infer their density and use it to constrain their composition, but several other interesting measurements are possible for these objects (see e.g. review by Charbonneau et al. 2007). In particular, their thermal emission can be measured during their occultation, allowing the study of their atmosphere without spatially resolving their light from that of the host star. The Spitzer Space Telescope (Werner et al. 2004) has produced a flurry of such planetary emission measurements, all at wavelengths longer than 3.5 ![]() m. From the ground, several attempts to obtain occultation measurements at shorter wavelengths than the Spitzer spectral window were performed (Richardson et al. 2003a,b; Snellen 2005; Deming et al. 2007; Knutson et al. 2007; Snellen & Covino 2007; Winn et al. 2008). Very recently, two of them were successful: Sing & López-Morales (2009) obtained a

m. From the ground, several attempts to obtain occultation measurements at shorter wavelengths than the Spitzer spectral window were performed (Richardson et al. 2003a,b; Snellen 2005; Deming et al. 2007; Knutson et al. 2007; Snellen & Covino 2007; Winn et al. 2008). Very recently, two of them were successful: Sing & López-Morales (2009) obtained a ![]() 4

4![]() detection of the occultation of OGLE-TR-56b in the z-band (0.9

detection of the occultation of OGLE-TR-56b in the z-band (0.9 ![]() m), while De Moiij & Snellen (2009) detected at

m), while De Moiij & Snellen (2009) detected at ![]() 6

6![]() the thermal emission of TrES-3b in the K-band (2.2

the thermal emission of TrES-3b in the K-band (2.2 ![]() m). It is important to obtain more similar measurements to improve our understanding of the atmospheric properties of short-period extrasolar planets.

m). It is important to obtain more similar measurements to improve our understanding of the atmospheric properties of short-period extrasolar planets.

CoRoT-1b (Barge et al. 2008, hereafter B08) was the first planet detected by the CoRoT space transit survey (Baglin et al. 2006). With an orbital period of 1.5 days, this Jupiter-mass planet orbits at only ![]() 5 stellar radii from its G0V host star. Thanks to this proximity, its stellar irradiation is clearly large enough (

5 stellar radii from its G0V host star. Thanks to this proximity, its stellar irradiation is clearly large enough (

![]() 109 erg s-1 cm-2) to make it join OGLE-TR-56b, TrES-3b and a few other planets within the pM theoretical class proposed by Fortney et al. (2008). Under this theory, pM planets receive a stellar flux large enough to have high-opacity compounds like TiO and VO present in their gaseous form in the day-side atmosphere. These compounds should be responsible for a stratospheric thermal inversion, with re-emission on a very short time scale of a large fraction of the incoming stellar flux, resulting in a poor efficiency of the heat distribution from the day-side to the night-side and to enhanced infrared planetary fluxes at orbital phases close to the occultation. Like the other pM planets, CoRoT-1b is thus a good target for near-infrared occultation measurements. Furthermore, CoRoT-1b belongs to the subgroup of the planets with a radius larger than predicted by basic models of irradiated planets (e.g. Burrows et al. 2007; Fortney et al. 2007). Tidal heating has been proposed by several authors (e.g. Bodenheimer et al. 2001; Jackson et al. 2008b) as a possible extra source of energy able to explain the radius anomaly shown by these hyper-bloated planets. As shown by Jackson et al. (2008b) and Ibgui & Burrows (2009), even a tiny orbital eccentricity is able to produce an intense tidal heating for very short-period planets. Occultation photometry does not only allow to measure the planetary thermal emission, but also strongly constrains the orbital eccentricity (see e.g. Charbonneau et al. 2005). Such an occultation measurement for CoRoT-1b could thus help for understanding its low density.

109 erg s-1 cm-2) to make it join OGLE-TR-56b, TrES-3b and a few other planets within the pM theoretical class proposed by Fortney et al. (2008). Under this theory, pM planets receive a stellar flux large enough to have high-opacity compounds like TiO and VO present in their gaseous form in the day-side atmosphere. These compounds should be responsible for a stratospheric thermal inversion, with re-emission on a very short time scale of a large fraction of the incoming stellar flux, resulting in a poor efficiency of the heat distribution from the day-side to the night-side and to enhanced infrared planetary fluxes at orbital phases close to the occultation. Like the other pM planets, CoRoT-1b is thus a good target for near-infrared occultation measurements. Furthermore, CoRoT-1b belongs to the subgroup of the planets with a radius larger than predicted by basic models of irradiated planets (e.g. Burrows et al. 2007; Fortney et al. 2007). Tidal heating has been proposed by several authors (e.g. Bodenheimer et al. 2001; Jackson et al. 2008b) as a possible extra source of energy able to explain the radius anomaly shown by these hyper-bloated planets. As shown by Jackson et al. (2008b) and Ibgui & Burrows (2009), even a tiny orbital eccentricity is able to produce an intense tidal heating for very short-period planets. Occultation photometry does not only allow to measure the planetary thermal emission, but also strongly constrains the orbital eccentricity (see e.g. Charbonneau et al. 2005). Such an occultation measurement for CoRoT-1b could thus help for understanding its low density.

These reasons motivated us to measure an occultation of CoRoT-1b with the Very Large Telescope (VLT). We also decided to obtain a precise VLT transit light curve for this planet to better constrain its orbital elements. Furthermore, CoRoT transit photometry presented in B08 is exquisite, but it is important to obtain an independent measurement of similar quality to check its reliability and to assess the presence of any systematic effect in the CoRoT photometry.

We present in Sect. 2 our new VLT data and their reduction. Section 3 presents our analysis of the resulting photometry and our determination of the system parameters. Our results are discussed in Sect. 4, before giving our conclusion in Sect. 5.

2 Observations

2.1 VLT/FORS2 transit photometry

A transit of CoRoT-1b was observed on 2008 February 28 with the FORS2 camera (Appenzeller et al. 1998) installed at the VLT/UT1 (Antu). The FORS2 camera has a mosaic of two 2k ![]() 4k MIT CCDs and is optimized for observations in the red with a very low level of fringes. It was used several times in the past to obtain high-precision transit photometry (e.g. Gillon et al. 2007a, 2008). The high-resolution mode was used to optimize the spatial sampling, resulting in a 4.6'

4k MIT CCDs and is optimized for observations in the red with a very low level of fringes. It was used several times in the past to obtain high-precision transit photometry (e.g. Gillon et al. 2007a, 2008). The high-resolution mode was used to optimize the spatial sampling, resulting in a 4.6' ![]() 4.6' field of view with a pixel scale of 0.063''/pixel. Airmass increased from 1.08 to 1.77 during the run that lasted from 1h16 to 4h30 UT. The quality of the night was photometric. Because of scheduling constraints, only a small amount of observations were performed before and after the transit, and the total out-of-transit (OOT) part of the run was only

4.6' field of view with a pixel scale of 0.063''/pixel. Airmass increased from 1.08 to 1.77 during the run that lasted from 1h16 to 4h30 UT. The quality of the night was photometric. Because of scheduling constraints, only a small amount of observations were performed before and after the transit, and the total out-of-transit (OOT) part of the run was only ![]() 50 min.

50 min.

One hundred fourteen images were acquired in the R_SPECIAL filter (

![]() nm, FWHM = 165 nm) with an exposure time of 15 s. After a standard prereduction, the stellar fluxes were extracted for all the images with the IRAF

nm, FWHM = 165 nm) with an exposure time of 15 s. After a standard prereduction, the stellar fluxes were extracted for all the images with the IRAF![]() DAOPHOT aperture photometry software (Stetson 1987). We noticed that CoRoT-1 was saturated in 11 images because of seeing and transparency variations, so we rejected these images from our analysis. Several sets of reduction parameters were tested, and we kept the one giving the most precise photometry for the stars of similar brightness to CoRoT-1. After a careful selection of reference stars, differential photometry was obtained. A linear fit for magnitude vs. airmass was performed to correct the photometry for differential reddening using the OOT data. The corresponding fluxes were then normalized using the OOT part of the photometry. The resulting transit light curve is shown in Fig. 1. After subtraction of the best-fit model (see next section), the obtained residuals show an rms of

DAOPHOT aperture photometry software (Stetson 1987). We noticed that CoRoT-1 was saturated in 11 images because of seeing and transparency variations, so we rejected these images from our analysis. Several sets of reduction parameters were tested, and we kept the one giving the most precise photometry for the stars of similar brightness to CoRoT-1. After a careful selection of reference stars, differential photometry was obtained. A linear fit for magnitude vs. airmass was performed to correct the photometry for differential reddening using the OOT data. The corresponding fluxes were then normalized using the OOT part of the photometry. The resulting transit light curve is shown in Fig. 1. After subtraction of the best-fit model (see next section), the obtained residuals show an rms of ![]() 520 ppm, very close to the photon noise limit (

520 ppm, very close to the photon noise limit (![]() 450 ppm).

450 ppm).

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{12231fg1.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/40/aa12231-09/Timg17.png) |

Figure 1: Top: VLT/FORS2 R-band transit light curve with the best-fitting transit + trend model superimposed. Bottom: residuals of the fit. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

2.2 VLT/HAWK-I occultation photometry

We observed an occultation of CoRoT-1b with HAWK-I (High Acuity Wide-field K-band Imager, Pirard et al. 2004; Casali et al. 2006), a cryogenic near-IR imager recently installed at the VLT/UT4 (Yepun). HAWK-I provides a relatively large field of view of 7.5' ![]() 7.5'. The detector is kept at 75 K and is composed of a mosaic of four Hawaii-2RG 2048

7.5'. The detector is kept at 75 K and is composed of a mosaic of four Hawaii-2RG 2048 ![]() 2048 pixels chips. The pixel scale is 0.106''/pixel, providing a good spatial sampling even for the excellent seeing conditions at Paranal (seeing down to 0.3 arcsec measured in K-band).

2048 pixels chips. The pixel scale is 0.106''/pixel, providing a good spatial sampling even for the excellent seeing conditions at Paranal (seeing down to 0.3 arcsec measured in K-band).

Instead of using a broad band K or ![]() filter, we chose to observe with the narrow band

filter NB2090 (central wavelength = 2.095

filter, we chose to observe with the narrow band

filter NB2090 (central wavelength = 2.095 ![]() m, width = 0.020

m, width = 0.020 ![]() m). This filter avoids absorption bands at the edge of the K-band, its small width minimizes the effect of differential extinction, and furthermore its bandpass shows much less sky emission than the one of the near Br

m). This filter avoids absorption bands at the edge of the K-band, its small width minimizes the effect of differential extinction, and furthermore its bandpass shows much less sky emission than the one of the near Br![]() filter (central wavelength = 2.165

filter (central wavelength = 2.165 ![]() m, width = 0.030

m, width = 0.030 ![]() m), leading to a flux ratio background/star more than twice better than in Br

m), leading to a flux ratio background/star more than twice better than in Br![]() or K-band filters. Because of the large aperture of the VLT and the relative brightness of CoRoT-1, the expected stellar count in

this narrow filter is still good enough to allow theoretical noise of less than 0.15% for a 1 min integration.

or K-band filters. Because of the large aperture of the VLT and the relative brightness of CoRoT-1, the expected stellar count in

this narrow filter is still good enough to allow theoretical noise of less than 0.15% for a 1 min integration.

Observations took place on 2009 January 06 from 1h54 to 7h56 UT. Atmospheric conditions were very good, while the mean seeing measured on the images was 0.47''. Airmass decreased from 1.36 to 1.08 then raised to 1.65. Each exposure was composed of 4 integrations of 11 s each. A random jitter pattern within a square 45''-sized box was applied to the telescope. This strategy aimed to obtain an accurate sky map from the neighboring for each image. Indeed, the near-IR background shows a strong spatial variability on different scales, and an accurate subtraction of this complex background is crucial, except when this background has a negligible amplitude when compared to the stellar count (see e.g. Alonso et al. 2008). In total, 318 images were obtained during the run.

After a standard pre-reduction (dark subtraction, flatfield division), a sky map was constructed and removed for each image using a median-filtered set of the ten adjacent images. The resulting sky-subtracted images were aligned and then compared on a per-pixel basis to the median of the 10 adjacent images in order to detect any spurious values due, e.g., to a cosmic hit or a pixel damage. The concerned pixels had their value replaced by the one obtained by linear interpolation using the 10 adjacent images.

Two different methods were tested to extract the stellar fluxes. Aperture photometry was obtained using the IRAF DAOPHOT software and compared to deconvolution photometry obtained with the algorithm DECPHOT (Gillon et al. 2006, 2007b; Magain et al. 2007). We obtained a significantly (![]() 25%) better result with DECPHOT. We attribute this improvement to DECPHOT optimizing the separation of the stellar flux from the background contribution, while aperture photometry simply sums the counts within an aperture.

25%) better result with DECPHOT. We attribute this improvement to DECPHOT optimizing the separation of the stellar flux from the background contribution, while aperture photometry simply sums the counts within an aperture.

To avoid any systematic noise due to the different characteristics of the HAWK-I chips, we chose to use only reference stars located in the same chip than our target to obtain the differential photometry. As CoRoT-1 lies in a dense field of the Galactic plane, we have enough reference flux in one single chip to reach the desired photometric precision. After a careful selection of the reference stars, the obtained differential curve clearly shows an eclipse with the expected duration and timing (Fig. 2). We could not find any firm correlation of the OOT photometric values with the airmass or time, so we simply normalized the fluxes using the OOT part without any further correction. The OOT rms is 0.32%, much larger than the mean theoretical error: 0.13%. This difference implies an extra source of noise of ![]() 0.3%. We attribute this noise to the sensitivity and cosmetic inhomogeneity of the detector combined with our jitter strategy. In the optical, one can avoid this noise by staring at the same exact position during the whole run, i.e. by keeping the stars on the same pixels. In the near-IR, dithering is needed to properly remove the large, complex, and variable background. This background varies in time at frequencies similar to the one of the transit, so any poor background removal is able to bring correlated noise in the resulting photometry. It is thus preferable to optimize the background subtraction by using a fast random jitter pattern even if this leads to extra noise, because this is dominated by frequencies much higher than the one of the searched signal and is thus unable to produce a fake detection or modify the eclipse shape.

0.3%. We attribute this noise to the sensitivity and cosmetic inhomogeneity of the detector combined with our jitter strategy. In the optical, one can avoid this noise by staring at the same exact position during the whole run, i.e. by keeping the stars on the same pixels. In the near-IR, dithering is needed to properly remove the large, complex, and variable background. This background varies in time at frequencies similar to the one of the transit, so any poor background removal is able to bring correlated noise in the resulting photometry. It is thus preferable to optimize the background subtraction by using a fast random jitter pattern even if this leads to extra noise, because this is dominated by frequencies much higher than the one of the searched signal and is thus unable to produce a fake detection or modify the eclipse shape.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{12231fg2.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/40/aa12231-09/Timg20.png) |

Figure 2:

Top: VLT/HAWK-I 2.09 |

| Open with DEXTER | |

3 Analysis

3.1 Data and model

To obtain an independent determination of the system parameters, we decided to use only our VLT R-band transit and 2.09 ![]() m occultation photometry, in addition to the SOPHIE (Bouchy et al. 2006) radial velocities (RV) presented in B08 as data for our analysis.

m occultation photometry, in addition to the SOPHIE (Bouchy et al. 2006) radial velocities (RV) presented in B08 as data for our analysis.

These data were used as input into a Markov-Chain Monte-Carlo (MCMC; see e.g. Tegmark 2004; Gregory 2005; Ford 2006) code. MCMC is a Bayesian inference method based on stochastic simulations and provides the a posteriori probability distribution of adjusted parameters for a given model. Here the model is based on a star and a transiting planet on a Keplerian orbit about their center of mass. More specifically, we used a classical Keplerian model for the RV variations and fitted independent offsets for the two epochs of the SOPHIE observations to account for the drift between them mentioned in B08. To fit the VLT photometry, we used the photometric eclipse model of Mandel & Agol (2002) multiplied by a trend model. To obtain reliable error bars for our fitted parameters, it is indeed preferable to consider the possible presence of a low-amplitude time-dependent systematic in our photometry due, e.g. to an imperfect differential extinction correction or a low-amplitude low-frequency stellar variability. We chose to model this trend as a second-order time polynomial function for both FORS2 and HAWK-I photometry.

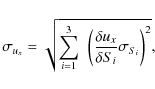

3.2 Limb-darkening

For the transit, a quadratic limb darkening law was assumed, with initial coefficients u1 and u2 interpolated from Claret's tables (2000, 2004) for the R-band photometric filter and for

![]()

![]() 150 K, log g = 4.25

150 K, log g = 4.25 ![]() 0.30 and [Fe/H] = -0.30

0.30 and [Fe/H] = -0.30 ![]() 0.25 (B08). We used the partial derivatives of u1 and u2 as a function of the spectroscopic parameters in Claret's tables to obtain their errors

0.25 (B08). We used the partial derivatives of u1 and u2 as a function of the spectroscopic parameters in Claret's tables to obtain their errors

![]() and

and

![]() via

via

where x is 1 or 2, while Si and

where c'i is the initial value deduced for the coefficient ci and

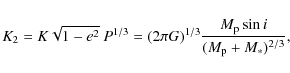

3.3 Jump parameters

The other jump parameters in our MCMC simulation were the transit timing (time of minimum light) T0, the planet/star area ratio

![]() ,

the transit width (from first to last contact) W, the impact parameter

,

the transit width (from first to last contact) W, the impact parameter

![]() ,

three coefficients per photometric time series for the low-frequency systematic, one systemic RV for each of the two SOPHIE epochs, and the two parameters

,

three coefficients per photometric time series for the low-frequency systematic, one systemic RV for each of the two SOPHIE epochs, and the two parameters

![]() and

and

![]() ,

where e is the orbital eccentricity and

,

where e is the orbital eccentricity and ![]() the argument of periastron. The RV orbital semi-amplitude K was not used as jump parameter, but instead we used the following parameter:

the argument of periastron. The RV orbital semi-amplitude K was not used as jump parameter, but instead we used the following parameter:

to minimize the correlation with the other jump parameters.

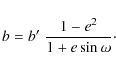

We notice that our used jump parameter b' is equal to the actual transit impact parameter b only for a circular orbit. For a non-zero eccentricity, it is related to the actual impact parameter b via

Here too, the goal of using b' instead of b is to minimize the correlation between the jump parameters.

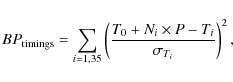

The orbital period P was let free in our analysis, constrained not only with the data presented above but also with the timings determined independently by Bean (2009) for each of the 35 CoRoT transits. Practically, we added the following Bayesian penalty

![]() to our merit function:

to our merit function:

where Ti is the transit timing determined by Bean (2009) for the

3.4 Photometric correlated noise and RV jitter noise

Our analysis was done in 4 steps. First, a single MCMC chain was performed. This chain was composed of 106 steps, the first 20% of each chain being considered as its burn-in phase and discarded. The best-fitting model found in the first chain was used to estimate the level of correlated noise in each photometric time-series and a jitter noise in the RV time series. For both photometric time series, the red noise was estimated as described in Gillon et al. (2006), by comparing the rms of the unbinned and binned residuals. We used a bin size corresponding to a duration of 20 min, similar to the timescale of the ingress/egress of the transit. The results were compatible with purely Gaussian noise for both time series. Still, it is possible that a low-amplitude correlated noise damaging only the eclipse part had been ``swallowed'' by our best-fitting model, so we preferred to be conservative and to quadratically add a red noise of 100 ppm to the theoretical uncertainties of each photometric time-series. The deduced RV jitter noise was high: 23 m s-1. Nevertheless, we noticed that it goes down to zero if we discard the second RV measurement of the first SOPHIE epoch. Furthermore, this measurement has a significantly larger error bar than the others, so we decided to consider it as doubtful and to do not use it in our analysis. A theoretical jitter noise of 3.5 m s-1 was then added quadratically to the error bars of the other SOPHIE measurements, a typical value for a quiet solar-type star like CoRoT-1 (Wright 2005).

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{12231fg3.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/40/aa12231-09/Timg39.png) |

Figure 3:

R/M1/3 (in solar units) versus effective temperature for CoRoT-1 compared to the theoretical stellar stellar evolutionary models of Girardi et al. (2000) interpolated at -0.3 metallicity. The labeled mass tracks are for 0.8, 0.9, and 1.0 |

| Open with DEXTER | |

3.5 Determining the stellar density

Then, 10 new MCMC chains were performed using the updated measurement error bars. These 10 chains were then combined, using the Gelman & Rubin statistics (Gelman & Rubin 1992) to verify that they were converged and mixed enough, and the best-fitting values and error bars for each parameter were obtained from their distribution. The goal of this MCMC run was to provide us with an improved estimation of the stellar density ![]() (see e.g. Torres 2007). The stellar density that we obtained was

(see e.g. Torres 2007). The stellar density that we obtained was

![]()

![]() .

.

3.6 Stellar-evolutionary modeling

The deduced stellar density and the spectroscopic parameters were then used to better constrain the stellar mass and age via a comparison with theoretical stellar evolution models. Two independent stellar analysis were performed to assess the impact of the stellar evolution models used on the final system parameters.

- Our first analysis was based on Girardi's evolution models (Girardi et al. 2000), as follows. We first perform a linear interpolation between the solar (Z=0.019) and subsolar

(Z=0.008) metallicity theoretical models to derive a set of mass tracks at the metallicity of the

host star ([M/H] = -0.3). We then compare the effective temperature and the inverse cube root of

the stellar density to the same values in the host star metallicity models. We interpolate

linearly along the mass tracks to generate an equal number of age points between the zero age

main sequence and the point corresponding to core hydrogen exhaustion. We then interpolate

between the tracks along equivalent evolutionary points to find the mass, M=0.94

,

and age,

,

and age,  = 7.1 Gyr, of the host star that match the measured temperature and stellar density best. We repeat the above prescription using the extreme values of the observed parameters to determine the uncertainties on the derived mass and age. The large errors on the spectroscopic parameters, particularly the

= 7.1 Gyr, of the host star that match the measured temperature and stellar density best. We repeat the above prescription using the extreme values of the observed parameters to determine the uncertainties on the derived mass and age. The large errors on the spectroscopic parameters, particularly the  dex uncertainty on the metallicity, lead to a 15-20% error on the stellar mass (

dex uncertainty on the metallicity, lead to a 15-20% error on the stellar mass (

)

and an age for the system no more precise than older than 0.5 Gyr. Figure 3 presents the deduced position of CoRoT-1 in a

)

and an age for the system no more precise than older than 0.5 Gyr. Figure 3 presents the deduced position of CoRoT-1 in a

diagram.

diagram.

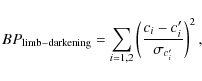

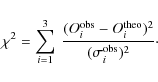

- In the second analysis, we applied the Levenberg-Marquard miniminization algorithm to derive the fundamental parameters of the host star. The merit function is defined by

(6)

The observables ( )

we take into consideration are effective temperature, surface metallicity, and mean density. The corresponding observational errors are

)

we take into consideration are effective temperature, surface metallicity, and mean density. The corresponding observational errors are

.

The theoretical values (

.

The theoretical values (

)

are obtained from stellar evolution models computed with the code CLES (Code Liégois d'Evolution Stellaire, Scuflaire et al. 2008). Several fittings have been performed, in all of them we use the mixing-length theory (MLT) of convection (Böhm-Vitense 1958) and the most recent equation of state from OPAL (OPAL05, Rogers & Nayfonov 2002). Opacity tables are those from OPAL (Iglesias & Rogers 1996) for two different solar mixtures, the standard one from Grevesse & Noels (1993, GN93) and the recently revised solar mixture from Asplund et al. (2005, AGS05). In the first case

)

are obtained from stellar evolution models computed with the code CLES (Code Liégois d'Evolution Stellaire, Scuflaire et al. 2008). Several fittings have been performed, in all of them we use the mixing-length theory (MLT) of convection (Böhm-Vitense 1958) and the most recent equation of state from OPAL (OPAL05, Rogers & Nayfonov 2002). Opacity tables are those from OPAL (Iglesias & Rogers 1996) for two different solar mixtures, the standard one from Grevesse & Noels (1993, GN93) and the recently revised solar mixture from Asplund et al. (2005, AGS05). In the first case

= 0.0245, in the second one

= 0.0245, in the second one

= 0.0167. These tables are extended at low temperatures with Ferguson et al. (2005) opacity values for the corresponding metal mixtures. The surface boundary conditions are given by grey atmospheres with an Eddington law. Microscopic diffusion (Thoul et al. 1994) is included in stellar model computation. The parameters of the stellar model are mass, initial hydrogen (

= 0.0167. These tables are extended at low temperatures with Ferguson et al. (2005) opacity values for the corresponding metal mixtures. The surface boundary conditions are given by grey atmospheres with an Eddington law. Microscopic diffusion (Thoul et al. 1994) is included in stellar model computation. The parameters of the stellar model are mass, initial hydrogen ( ), and metal (

), and metal ( )

mass fractions, age, and the parameters of convection (

)

mass fractions, age, and the parameters of convection (

and the overshooting parameter). Since we only have three observational constraints, we decided to fix the

and the overshooting parameter). Since we only have three observational constraints, we decided to fix the

and

and  values to those derived from the solar calibration for the same input physics. Furthermore, given the low mass we expect for the host star, all the models are computed without overshooting. The values of stellar mass and age obtained for the two different solar mixtures are: M=0.90

values to those derived from the solar calibration for the same input physics. Furthermore, given the low mass we expect for the host star, all the models are computed without overshooting. The values of stellar mass and age obtained for the two different solar mixtures are: M=0.90

with GN93 and M=0.92

with GN93 and M=0.92

with AGS05, and respectively

with AGS05, and respectively

6.0 Gyr and

6.0 Gyr and

5.4 Gyr.

5.4 Gyr.

Table 1:

CoRoT-1 system parameters and 1-![]() error limits derived from the MCMC analysis.

error limits derived from the MCMC analysis.

3.7 Determining the system parameters

For the last part of our analysis, we decided to use 0.93 ![]() 0.18

0.18 ![]() ,

i.e. the average of the values obtained with the two different evolution models, as our starting value for the stellar mass. A new MCMC run was then performed. This run was identical to the first one, with the exception that

,

i.e. the average of the values obtained with the two different evolution models, as our starting value for the stellar mass. A new MCMC run was then performed. This run was identical to the first one, with the exception that ![]() was also a jump parameter under the control of a Bayesian penalty based on

was also a jump parameter under the control of a Bayesian penalty based on ![]() = 0.93

= 0.93 ![]() 0.18

0.18 ![]() .

At each step of the chains, the physical parameters

.

At each step of the chains, the physical parameters ![]() ,

,

![]() ,

and

,

and ![]() were computed from the relevant jump parameters including the stellar mass. Table 1 shows the values deduced for the jump + physical parameters and compares them to the values presented in B08. It also shows the Bayesian penalties used in this second MCMC run.

were computed from the relevant jump parameters including the stellar mass. Table 1 shows the values deduced for the jump + physical parameters and compares them to the values presented in B08. It also shows the Bayesian penalties used in this second MCMC run.

4 Discussion

4.1 The density and eccentricity of CoRoT-1b

As can be seen in Table 1, the transit parameters that we obtain from our VLT/FORS-2 R-band photometry agree well with the ones presented in B08 and based on CoRoT photometry. Our value for the transit impact parameter is in good agreement with the one obtained by B08, and has a similar uncertainty. The planet/star area ratio that we deduce is within the error bar of the values obtained by B08, while our error bar is smaller. Our deduced physical parameters also agree very well with the ones presented in B08. Our analysis thus confirms the very low density of the planet (see Fig. 4) and its membership in the subgroup of short period planets too large for current models of irradiated planets (Burrows et al. 2007; Fortney et al. 2008).

In this context, it is worth noticing the marginal non-zero eccentricity that we deduce from our combined analysis:

![]() .

As outlined in recent works (Jackson et al. 2008b; Ibgui & Burrows 2009), tidal heating could play a major role in the energy budget of very short period planets and help explain the very low density of some of them. Better constraining the orbital eccentricity of CoRoT-1b by obtaining more radial velocity measurements and occultation photometry is thus desirable. To test the amplitude of the constraint brought by the occultation on the orbital eccentricity, we made an analysis similar to the one presented in Sect. 3 but discarded the HAWK-I photometry. We obtained similar results for the transit parameters, but the eccentricity was poorly constrained, so we obtained much less precise values for

.

As outlined in recent works (Jackson et al. 2008b; Ibgui & Burrows 2009), tidal heating could play a major role in the energy budget of very short period planets and help explain the very low density of some of them. Better constraining the orbital eccentricity of CoRoT-1b by obtaining more radial velocity measurements and occultation photometry is thus desirable. To test the amplitude of the constraint brought by the occultation on the orbital eccentricity, we made an analysis similar to the one presented in Sect. 3 but discarded the HAWK-I photometry. We obtained similar results for the transit parameters, but the eccentricity was poorly constrained, so we obtained much less precise values for

![]() and

and

![]() ,

respectively,

,

respectively,

![]() and

and

![]() .

The HAWK-I occultation thus brings a strong constraint on these parameters, especially on

.

The HAWK-I occultation thus brings a strong constraint on these parameters, especially on

![]() .

.

Table 1 shows that our analysis does not agree with B08 for one important parameter: the stellar density. Indeed, the value presented in B08 is significantly lower and more precise than ours. Still, B08 assumed a zero eccentricity in their analysis, while the stellar mean density deduced from transit observables depend on e and ![]() (see e.g. Winn 2009). To test the influence of the zero eccentricity assumption on the deduced stellar density, we made a new MCMC analysis assuming e = 0. This time we obtained

(see e.g. Winn 2009). To test the influence of the zero eccentricity assumption on the deduced stellar density, we made a new MCMC analysis assuming e = 0. This time we obtained

![]()

![]() ,

in excellent agreement with the value

,

in excellent agreement with the value

![]()

![]() 0.033

0.033

![]() presented by B08. This nicely shows that not only are VLT and CoRoT data fully compatible, but also that assuming a zero eccentricity can lead to an unreliable stellar density value and uncertainty. In our case, this has no significant impact on the deduced physical parameters because the large errors that we have on the stellar effective temperature and metallicity totally dominate the result of the stellar-evolutionary modeling (see Sect. 3.6). Still, this point is important. As shown by Jackson et al. (2008a), most published estimates of planetary tidal circularization timescales have used inappropriate assumptions that lead to unreliable values, and most close-in planets could probably keep a tiny but non-zero eccentricity during a major part of their lifetime. In this context, very precise transit photometry like the CoRoT one is not enough to reach the highest accurary on the physical parameters of the system, and a precise determination of e and

presented by B08. This nicely shows that not only are VLT and CoRoT data fully compatible, but also that assuming a zero eccentricity can lead to an unreliable stellar density value and uncertainty. In our case, this has no significant impact on the deduced physical parameters because the large errors that we have on the stellar effective temperature and metallicity totally dominate the result of the stellar-evolutionary modeling (see Sect. 3.6). Still, this point is important. As shown by Jackson et al. (2008a), most published estimates of planetary tidal circularization timescales have used inappropriate assumptions that lead to unreliable values, and most close-in planets could probably keep a tiny but non-zero eccentricity during a major part of their lifetime. In this context, very precise transit photometry like the CoRoT one is not enough to reach the highest accurary on the physical parameters of the system, and a precise determination of e and ![]() is also needed. This strengthens the interest in getting complementary occultation photometry in addition to high-precision radial velocities to improve the characterization of transiting planets.

is also needed. This strengthens the interest in getting complementary occultation photometry in addition to high-precision radial velocities to improve the characterization of transiting planets.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{12231fg4.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/40/aa12231-09/Timg123.png) |

Figure 4: Position of CoRoT-1b (in red) among the other transiting planets (black circles, values from http://exoplanet.eu) in a mass-radius diagram. The error bars are shown only for CoRoT-1b for the sake of clarity. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

4.2 The atmospheric properties of CoRoT-1b

The flux at 2.09 ![]() m of this planet is slightly more than the one deduced from the (zero-albedo) equilibrium temperature,

m of this planet is slightly more than the one deduced from the (zero-albedo) equilibrium temperature, ![]() 2660 K, obtained if the star's effective temperature is allowed to be as high as 6100 K (maximum within the 1-

2660 K, obtained if the star's effective temperature is allowed to be as high as 6100 K (maximum within the 1-![]() error-bars from B08). An irradiated planet atmosphere model (following Barman et al. 2005) for CoRoT-1b was computed by adopting the maximum observational allowed stellar effective temperature and radius and by assuming that zero energy is transported to the night side. Solar metallicity was assumed and all other parameters

were taken from Table 1. This model (Fig. 5) falls short of matching the observations within 1-

error-bars from B08). An irradiated planet atmosphere model (following Barman et al. 2005) for CoRoT-1b was computed by adopting the maximum observational allowed stellar effective temperature and radius and by assuming that zero energy is transported to the night side. Solar metallicity was assumed and all other parameters

were taken from Table 1. This model (Fig. 5) falls short of matching the observations within 1-![]() ,

while a black body with the same equilibrium temperature as the irradiated planet model is in better agreement. The atmosphere model is hot enough for a significant temperature inversion

to form for P < 0.1 bar and is nearly isothermal from 0.1 down to

,

while a black body with the same equilibrium temperature as the irradiated planet model is in better agreement. The atmosphere model is hot enough for a significant temperature inversion

to form for P < 0.1 bar and is nearly isothermal from 0.1 down to ![]() 100 bar. A model that uniformly redistributes the absorbed stellar flux across the entire planet surface (lower curve in Fig. 5) is far too cool to match the observations and is excluded at

100 bar. A model that uniformly redistributes the absorbed stellar flux across the entire planet surface (lower curve in Fig. 5) is far too cool to match the observations and is excluded at ![]() 3

3![]() .

The flux at 2.09

.

The flux at 2.09 ![]() m alone is suggestive that very little energy is redistributed to the night side; however, additional observations at shorter and/or longer wavelengths are needed to better estimate the bolometric flux of the planet's day side. Occultation measurements in other bands will help provide limits on the day side bolometric flux and determine the depth of any possible temperature inversion and the extent of the isothermal zone.

m alone is suggestive that very little energy is redistributed to the night side; however, additional observations at shorter and/or longer wavelengths are needed to better estimate the bolometric flux of the planet's day side. Occultation measurements in other bands will help provide limits on the day side bolometric flux and determine the depth of any possible temperature inversion and the extent of the isothermal zone.

Recently, Snellen et al. (2009) have measured the dayside planet-star flux ratio of CoRoT-1

in the optical (![]() 0.7

0.7 ![]() m) to be 1.26

m) to be 1.26 ![]() 0.33

0.33 ![]() 10-4. The hot, day-side only model shown in Fig. 5 predicts a value of 1.29

10-4. The hot, day-side only model shown in Fig. 5 predicts a value of 1.29 ![]() 0.33

0.33 ![]() 10-4, which is fully consistent with the optical measurement. Consequently, it appears as though very little energy is being carried over to the night side of this planet.

10-4, which is fully consistent with the optical measurement. Consequently, it appears as though very little energy is being carried over to the night side of this planet.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{12231fg5.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/40/aa12231-09/Timg124.png) |

Figure 5:

Comparison of our 2.09 |

| Open with DEXTER | |

4.3 Assessing the presence of another body in the system

As shown in Table 1, our deduced systemic RV for each SOPHIE epoch agrees with each other, so we do not confirm the RV drift mentioned in B08. Our combined analysis presented in Sect. 3 leads to a very precise determination of the orbital period:

![]() days, thanks to a lever arm of nearly one year between CoRoT transits and the VLT one. A simple linear fit to timing versus epoch data based on the CoRoT and VLT transits lead to a similar level of precision, giving

days, thanks to a lever arm of nearly one year between CoRoT transits and the VLT one. A simple linear fit to timing versus epoch data based on the CoRoT and VLT transits lead to a similar level of precision, giving

![]() days. This fit has a reduced

days. This fit has a reduced ![]() of 1.28, and the rms of its residuals (see Fig. 6) is 36 s. These values are fully consistent with those reported by Bean (2009) for CoRoT data alone. We also notice the same 3-

of 1.28, and the rms of its residuals (see Fig. 6) is 36 s. These values are fully consistent with those reported by Bean (2009) for CoRoT data alone. We also notice the same 3-![]() discrepancy with transit #23 that, once removed, results in a reduced

discrepancy with transit #23 that, once removed, results in a reduced ![]() of 1.00, hereby confirming the remarkable periodicity of the transit signal.

of 1.00, hereby confirming the remarkable periodicity of the transit signal.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{12231fg6.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/40/aa12231-09/Timg127.png) |

Figure 6: Top: residuals of the linear fit timing vs. epoch for CoRoT-1b (see text for details). The rightmost point is our VLT/FORS2 timing. Botttom: zoom on the CoRoT residuals. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Limits on additional planetary companions in CoRoT-1 system were extensively discussed for transit timing variations (TTVs) by Bean (2009). Here we compare the approach proposed by Holman & Murray (2005) and the one from Agol et al. (2005). We have plotted the detection diagram related to the former in Fig. 7, where we represent the maximum successive transit timings interval as a function of mass and period of a putative perturbator.

Furthermore, Fig. 7 illustrates the domain where additional planets could be found through TTVs (white) and RV measurements (above colored curves). We focused on short period objects, since TTVs are more sensitive to nearby perturbators as compared to the known transiting planet. We assumed an eccentricity of 0.05 for a putative coplanar planet and used the MERCURY package described in Chambers (1999) to estimate the maximum TTV signal expected for CoRoT-1b by numerical integration. White is the domain with >3-![]() detection by TTVs according to CoRoT data rms, while the black area is below the 1-

detection by TTVs according to CoRoT data rms, while the black area is below the 1-![]() detection threshold. Although approximate, this shows that, for a typical 3 m s-1 accuracy of radial velocities (dashed curve in Fig. 7) routinely obtained with HARPS spectrograph (Mayor et al. 2003), planetary companion detection is not possible by TTVs alone with this approach for this system.

detection threshold. Although approximate, this shows that, for a typical 3 m s-1 accuracy of radial velocities (dashed curve in Fig. 7) routinely obtained with HARPS spectrograph (Mayor et al. 2003), planetary companion detection is not possible by TTVs alone with this approach for this system.

Figure 8 shows the detection domain for Agol et al. (2005) approach, where the authors benefit from the TTV being cumulative in resonances yielding a larger amplitude signal. In this case, the minimum detectable mass in 2:1 resonance with available timings is about 2.5 Earth masses. In the case of planets near/in resonance, this approach provides an important gain in detection, provided observations on a long timescale are available. We evaluated our numerical integrations over a time scale corresponding to the interval between the first CoRoT-1b transit observation and our VLT transit, which spans 256 epochs. Those observations sample, only partly in most cases, the libration period of the putative planet, yielding an amplitude that is smaller than the one that would be obtained over a longer range. This approach does not require observation of successive transits in contrast to the Holman & Murray (2005) method.

The search for smaller temporal variations is more sensitive to noise. However, a comparison between Figs. 7 and 8 shows that for a short observation time span and outside resonances, observation of successive transits may be a fruitful strategy.

The TTV search method may be applied to active and/or stars for which RV measurements accuracy is limited, increasing a detectability area that RVs are not, or far less sensitive to. Each transit timing may be compared to a single RV measurement. The increased free parameters in a TTV orbital solution raise degeneracies that cannot be lifted by considering the same number of datapoints that would allow an orbital solution recovery with RVs. The determination of a large number of consecutive transits and their addition to occultation timings helps to determine a unique of the solution, as well as lowering constraints on timing accuracy (Nesvorný & Morbidelli 2008). This is thus a high-cost approach that is the most potentially rewarding for carefully determined target stars.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=7.5cm,clip]{12231fg7.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/40/aa12231-09/Timg128.png) |

Figure 7:

Detectivity domain for a putative CoRoT-1c planet according to Holman & Murray (2005) approach, assuming

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=7.5cm,clip]{12231fg8.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/40/aa12231-09/Timg129.png) |

Figure 8: Same as Fig. 7, but for the Agol et al. (2005) TTV approach. See text for details. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

5 Conclusion

We have obtained new high-precision transit photometry for the planet CoRoT-1b. Our deduced system parameters are in very good agreement with the ones presented in B08, thus providing an independent verification of the validity of the CoRoT photometry. Thanks to the precision of the CoRoT and VLT transit photometry and the long baseline between them, the orbital period is now known to a precision better than 1/10th of a second. The precision on the planetary mass and radius is limited by the large errors on the stellar spectroscopic parameters, and a significant precision improvement should be made possible by getting new high-quality spectra of CoRoT-1.

We also successfully measured the occultation of the planet with HAWK-I, a new wide-field near-infrared imager mounted recently on the VLT. The large occultation depth that we measure is better reproduced by an atmospheric model with no redistribution of the absorbed stellar flux to the night side of the planet. This measurement firmly establishes the potential of the HAWK-I instrument for the study of exoplanetary atmospheres. At the time of writing, Spitzer cryogen is nearly depleted, and soon only its 3.6 ![]() m and 4.5

m and 4.5 ![]() m will remain available for occultation measurements, while the eagerly awaited JWST (Gardner et al. 2006) is not scheduled for launch before 2013. It is thus reassuring to note that ground-based near-infrared photometry is now able to perform precise planetary occultation measurements, bringing new independent constraints on the orbital eccentricity and on the atmospheric physics and composition of highly irradiated extrasolar planets.

m will remain available for occultation measurements, while the eagerly awaited JWST (Gardner et al. 2006) is not scheduled for launch before 2013. It is thus reassuring to note that ground-based near-infrared photometry is now able to perform precise planetary occultation measurements, bringing new independent constraints on the orbital eccentricity and on the atmospheric physics and composition of highly irradiated extrasolar planets.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the VLT staff for its support during the preparation and acquisition of the observations. In particular, J. Smoker and F. Selman are gratefully acknowledged for their help and support during the HAWK-I run. C. Moutou and F. Pont are acknowledged for their preparation of the FORS2 observations. F. Bouchy, PI of the ESO Program 080.C-0661(B), is also gratefully acknowledged. M. Gillon acknowledges support from the Belgian Science Policy Office in the form of a Return Grant, and thanks A. Collier Cameron for his help during the development of his MCMC analysis method. J. Montalbán thanks A. Miglio for his implementation of the optimization algorithm used in her stellar-evolutionary modeling. We thank the referee Scott Gaudi for a critical and constructive report. We are grateful to Eric Agol for providing insightful comments on this manuscript.

References

- Agol, E., Steffen, J., Sari, R., & Clarkson, W. 2005, MNRAS, 359, 567 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Alonso, R., Barbieri, M., Rabus, M., et al. 2008, A&A, 487, L5 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] (In the text)

- Appenzeller, I., Fricke, K., Furtig, W., et al. 1998, The Messenger, 94, 1 [NASA ADS] (In the text)

- Asplund, M., Grevesse, N., & Sauval, A. J. 2005, Cosmic Abundances as Records of Stellar Evolution and Nucleosynthesis, ASP Proc. Symp., 336, 25 (In the text)

- Baglin, A., Auvergne, M., Boisnard, L., et al. 2006, 36th COSPAR Scientific Assembly, 36, 3749 (In the text)

- Barge, P., Baglin, A., Auvergne, M., et al. 2008, A&A, 482, L17 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] (In the text)

- Barman, T. S., Hauschildt, P., & Allard, F. 2005, ApJ, 632, 1132 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Bean, J. L. 2009, A&A, 506, 369 [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] (In the text)

- Bodenheimer, P., Lin, D. N. C., & Mardling, R. A. 2001, ApJ, 548, 466 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Böhm-Vitense, E. 1958, ZAp, 46, 108 [NASA ADS] (In the text)

- Bouchy, F., The Sophie Team 2006, in Tenth Anniversary of 51 Peg-b, 319 (In the text)

- Burrows, A., Hubeny, I., Budaj, J., & Hubbard, W. B. 2007, ApJ, 661, 502 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Casali, M., Pirard, J.-F., Kissler-Patig, M., et al. 2006, SPIE, 6269, 29 [NASA ADS] (In the text)

- Chambers, J. E. 1999, MNRAS, 304, 793 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Charbonneau, D., Allen, L. E., Megeath, S. T., et al. 2005, ApJ, 626, 523 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Charbonneau, D., Brown, T. M., Burrows, A., & Laughlin, G. 2007, Protostars and Planets V, ed. B. Reipurth, D. Jewitt, & K. Keill (Tucson: University of Arizona Press), 701 (In the text)

- Claret, A. 2000, A&A, 363, 1081 [NASA ADS] (In the text)

- Claret, A. 2004, A&A, 428, 1001 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] (In the text)

- Deming, D., Richardson, L. J., & Harrington, J. 2007, MNRAS, 378, 148 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- De Mooij, E. J. W., & Snellen, I. A. G. 2009, A&A, 493, L35 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] (In the text)

- Ferguson, J. W., Alexander, D. R., Allard, F., et al. 2005, ApJ, 623, 585 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Ford, E. 2006, ApJ, 642, 505 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Fortney, J. J., Marley, M. S., & Barnes, J. W. 2007, ApJ, 658, 1661 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Fortney, J. J., Lodders, K., Marley, M. S., & Freedman, R. S. 2008, ApJ, 678, 1419 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Gardner, J. P., Mather, J. C., Clampin, M., et al. 2006, Space Sci. Rev., 123, 485 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Gillon, M., Pont, F., Moutou, C., et al. 2006, A&A, 459, 249 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] (In the text)

- Gillon, M., Pont, F., Moutou, C., et al. 2007a, A&A, 466, 743 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] (In the text)

- Gillon, M., Magain, P., Chantry, V., et al. 2007b, ASPC, 366, 113 [NASA ADS] (In the text)

- Gillon, M., Smalley, B., Hebb, L., et al. 2009, A&A, 496, 259 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences]

- Girardi, L., Bressan, A., Bertelli, G., & Chiosi, C. 2000, A&AS, 141, 371 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] (In the text)

- Gelman, A., & Rubin, D. 1992, Stat. Sci., 7, 457 [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Gregory, P. C. 2005, ApJ, 631, 1198 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Grevesse, N., & Noels, A. 1993, in La formation des éléments chimiques, AVCP, ed. B. Hauck, & S. R. D. Paltani (In the text)

- Holman, M. J., & Murray, N. W. 2005, Science, 307, 1288 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Holman, M. J., Winn, J. N., Latham, D. W., et al. 2006, ApJ, 652, 1715 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Ibgui, L., & Burrows, A. 2009, ApJ, 700, 1921 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Iglesias, C. A., & Rogers, F. J. 1996, ApJ, 464, 943 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Jackson, B., Greenberg, R., & Barnes, R. 2008a, ApJ, 681, 1631 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Jackson, B., Greenberg, R., & Barnes, R. 2008b, ApJ, 681, 1631 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Knutson, H. A., Charbonneau, D., Deming, D., & Richardson, L. J. 2007, PASP, 119, 616 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Magain, P., Courbin, F., Gillon, M., et al. 2007, A&A, 461, 373 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] (In the text)

- Mandel, K., & Agol, E. 2002, ApJ, 5802, L171 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Mayor, M., Pepe, F., & Queloz, D. 2003, The Messenger, 114, 20 [NASA ADS] (In the text)

- Nesvorný, D., & Morbidelli, A. 2008, ApJ, 688, 636 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Pirard, J.-F., Kissler-Patig, M., Moorwood, A., et al. 2004, SPIE, 5492, 510 (In the text)

- Richardson, L. J., Deming, D., & Seager, S. 2003a, ApJ, 597, 581 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Richardson, L. J., Deming, D., Wiedemann, G., et al. 2003b, ApJ, 584, 1053 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, F. J., & Nayfonov, A. 2002, ApJ, 576, 1064 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Scuflaire, R., Théado, S., Montalbán, J., et al. 2008, APSS, 316, 83 [NASA ADS] (In the text)

- Sing, D. K., & López-Morales, M. 2009, A&A, 493, L31 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] (In the text)

- Snellen, I. A. G. 2005, MNRAS, 363, 211 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Snellen, I. A. G., & Covino, E. 2007, MNRAS, 375, 307 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Snellen, I. A. G., de Mooij, E. J. W., & Albrecht, S. 2009, Nature, 459, 543 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Tegmark, M., Strauss, M. A., & Blanton, M. R. 2004, Phys. Rev. D., 69, 103501 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Thoul, A., Bahcall, J. N., & Loeb, A. 1994, ApJ, 421, 828 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Torres, G. 2007, ApJ, 671, L65 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Werner, M. W., Roellig, T. L., & Low, F. J. 2004, ApJS, 154, 1 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Winn, J. N. 2008, IAU 253, Transiting Planets, ed. F. Pont (Cambridge USA), 99

- Winn, J. N., Holman, M. J., Shporer, A., et al. 2008, ApJ, 136, 267 [NASA ADS] (In the text)

- Wrigth, J. T. 2005, PASP, 117, 657 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

Footnotes

- ... CoRoT-1b

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- Based on data collected with the VLT/FORS2 and VLT/HAWK-I instruments at ESO Paranal Observatory, Chile (programs 080.C-0661(B) and 382.C-0642(A)).

- ...

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- The photometric time-series used in this work are only available in electronic form at the CDS via anonymous ftp to cdsarc.u-strasbg.fr (130.79.128.5) or via http://cdsweb.u-strasbg.fr/cgi-bin/qcat?J/A+A/506/359

- ... IRAF

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- IRAF is distributed by the National Optical Astronomy Observatory, which is operated by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy, Inc., under cooperative agreement with the National Science Foundation.

All Tables

Table 1:

CoRoT-1 system parameters and 1-![]() error limits derived from the MCMC analysis.

error limits derived from the MCMC analysis.

All Figures

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{12231fg1.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/40/aa12231-09/Timg17.png) |

Figure 1: Top: VLT/FORS2 R-band transit light curve with the best-fitting transit + trend model superimposed. Bottom: residuals of the fit. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{12231fg2.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/40/aa12231-09/Timg20.png) |

Figure 2:

Top: VLT/HAWK-I 2.09 |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{12231fg3.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/40/aa12231-09/Timg39.png) |

Figure 3:

R/M1/3 (in solar units) versus effective temperature for CoRoT-1 compared to the theoretical stellar stellar evolutionary models of Girardi et al. (2000) interpolated at -0.3 metallicity. The labeled mass tracks are for 0.8, 0.9, and 1.0 |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{12231fg4.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/40/aa12231-09/Timg123.png) |

Figure 4: Position of CoRoT-1b (in red) among the other transiting planets (black circles, values from http://exoplanet.eu) in a mass-radius diagram. The error bars are shown only for CoRoT-1b for the sake of clarity. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{12231fg5.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/40/aa12231-09/Timg124.png) |

Figure 5:

Comparison of our 2.09 |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{12231fg6.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/40/aa12231-09/Timg127.png) |

Figure 6: Top: residuals of the linear fit timing vs. epoch for CoRoT-1b (see text for details). The rightmost point is our VLT/FORS2 timing. Botttom: zoom on the CoRoT residuals. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=7.5cm,clip]{12231fg7.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/40/aa12231-09/Timg128.png) |

Figure 7:

Detectivity domain for a putative CoRoT-1c planet according to Holman & Murray (2005) approach, assuming

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=7.5cm,clip]{12231fg8.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/40/aa12231-09/Timg129.png) |

Figure 8: Same as Fig. 7, but for the Agol et al. (2005) TTV approach. See text for details. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

Copyright ESO 2009

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.