| Issue |

A&A

Volume 505, Number 3, October III 2009

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Page(s) | 999 - 1005 | |

| Section | Cosmology (including clusters of galaxies) | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/200912760 | |

| Published online | 11 August 2009 | |

Constraints on leptonically annihilating dark matter from reionization and extragalactic gamma background

G. Hütsi1,2 - A. Hektor3 - M. Raidal3

1 - Department of Physics and Astronomy, University College London, London, WC1E 6BT, UK

2 - Tartu Observatory, Tõravere 61602, Estonia

3 - National Institute of Chemical Physics and Biophysics, Tallinn 10143, Estonia

Received 25 June 2009 / Accepted 3 August 2009

Abstract

Context. The PAMELA, Fermi and HESS experiments (PFH) have shown anomalous excesses in the cosmic positron and electron fluxes. A very exciting possibility is that those excesses are due to annihilating dark matter (DM).

Aims. In this paper we calculate constraints on leptonically annihilating DM using observational data on diffuse extragalactic ![]() -ray background and measurements of the optical depth to the last-scattering surface, and compare those with the PFH favored region in the

-ray background and measurements of the optical depth to the last-scattering surface, and compare those with the PFH favored region in the

![]() plane.

plane.

Methods. Having specified the detailed form of the energy input with PYTHIA Monte Carlo tools we solve the radiative transfer equation which allows us to determine the amount of energy being absorbed by the cosmic medium and also the amount left over for the diffuse gamma background.

Results. We find that the constraints from the optical depth measurements are able to rule out the PFH favored region fully for the

![]() annihilation channel and almost fully for the

annihilation channel and almost fully for the

![]() annihilation channel. It turns out that those constraints are quite robust with almost no dependence on low redshift clustering boost. The constraints from the

annihilation channel. It turns out that those constraints are quite robust with almost no dependence on low redshift clustering boost. The constraints from the ![]() -ray background are sensitive to the assumed halo concentration model and, for the power law model, rule out the PFH favored region for all leptonic annihilation channels. We also find that it is possible to have models that fully ionize the Universe at low redshifts. However, those models produce too large free electron fractions at

-ray background are sensitive to the assumed halo concentration model and, for the power law model, rule out the PFH favored region for all leptonic annihilation channels. We also find that it is possible to have models that fully ionize the Universe at low redshifts. However, those models produce too large free electron fractions at

![]() and are in conflict with the optical depth measurements. Also, the magnitude of the annihilation cross-section in those cases is larger than suggested by the PFH data.

and are in conflict with the optical depth measurements. Also, the magnitude of the annihilation cross-section in those cases is larger than suggested by the PFH data.

Key words: cosmology: theory - dark matter - diffuse radiation - cosmic microwave background - elementary particles

1 Introduction

The PAMELA and Fermi satellite experiments and the HESS atmospheric Cherenkov telescope have shown an anomalous excesses in the cosmic electron and positron spectra. PAMELA has observed a steep rise of positron fraction

Here we continue model independent studies of the DM annihilations into standard model charged leptons,

![]()

![]() extending the analyses presented in series of works, e.g. Cirelli et al. (2009), Borriello et al. (2009), Cirelli & Panci (2009), Meade et al. (2009), Arkani-Hamed et al. (2009).

Because DM annihilations to charged particles necessarily induce

extending the analyses presented in series of works, e.g. Cirelli et al. (2009), Borriello et al. (2009), Cirelli & Panci (2009), Meade et al. (2009), Arkani-Hamed et al. (2009).

Because DM annihilations to charged particles necessarily induce ![]() -ray signal, the observed

-ray signal, the observed ![]() -ray

fluxes strongly constrain the DM annihilation scenario as an explanation to the above mentioned cosmic ray anomalies.

Most of the

-ray

fluxes strongly constrain the DM annihilation scenario as an explanation to the above mentioned cosmic ray anomalies.

Most of the ![]() -ray constraints arise from the observations of Galactic center where the DM density is the highest.

Those analyses take into account both the primary photons produced by final state radiation and decays of the DM annihilation products

-ray constraints arise from the observations of Galactic center where the DM density is the highest.

Those analyses take into account both the primary photons produced by final state radiation and decays of the DM annihilation products ![]() (Bell & Jacques 2009; Bertone et al. 2009) as well as the secondary

inverse Compton (IC) scattering photon flux produced by them (Cirelli & Panci 2009; Meade et al. 2009).

(Bell & Jacques 2009; Bertone et al. 2009) as well as the secondary

inverse Compton (IC) scattering photon flux produced by them (Cirelli & Panci 2009; Meade et al. 2009).

In this study we focus on the possible effects of photons produced in extragalactic DM annihilations all over the Universe today and in the past.

We are particularly interested in finding out if the extragalactic photon signals are able to rule out the PAMELA, Fermi, and HESS (PFH) favored regions on the

![]() plane as given in Meade et al. (2009). For this purpose we look at two extragalactic signals: (i) the diffuse

plane as given in Meade et al. (2009). For this purpose we look at two extragalactic signals: (i) the diffuse ![]() -ray background including both the primary photons as well as the secondary photon flux produced in IC scattering of electrons off the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) photons; (ii) the Thompson scattering optical depth of the CMB photons caused by the free electrons between us and the last scattering surface

-ray background including both the primary photons as well as the secondary photon flux produced in IC scattering of electrons off the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) photons; (ii) the Thompson scattering optical depth of the CMB photons caused by the free electrons between us and the last scattering surface![]() .

While the previous works on those topics take into account only the direct photons produced in DM annihilations, we show that

in fact the diffuse IC photon spectrum gives the strongest constraint.

We stress the complementarity between those observables: the more energy ends up in extragalactic gamma background the less energy is available for ionizing/heating the gas, and vice verse.

The spectrum of diffuse

.

While the previous works on those topics take into account only the direct photons produced in DM annihilations, we show that

in fact the diffuse IC photon spectrum gives the strongest constraint.

We stress the complementarity between those observables: the more energy ends up in extragalactic gamma background the less energy is available for ionizing/heating the gas, and vice verse.

The spectrum of diffuse ![]() -ray background has been measured by Sreekumar et al. (1998) using data from the EGRET space experiment and the optical depth to decoupling has been derived from the CMB measurements by the WMAP satellite (Dunkley et al. 2009). New more precise data on

-ray background has been measured by Sreekumar et al. (1998) using data from the EGRET space experiment and the optical depth to decoupling has been derived from the CMB measurements by the WMAP satellite (Dunkley et al. 2009). New more precise data on ![]() -ray background is expected to be published by Fermi satellite this year.

-ray background is expected to be published by Fermi satellite this year.

The effect of annihilating DM on reionization and recombination has been previously investigated by a few authors, e.g. Padmanabhan & Finkbeiner (2005), Mapelli et al. (2006), Zhang et al. (2006), Natarajan & Schwarz (2008), Belikov & Hooper (2009a), Galli et al. (2009), Slatyer et al. (2009). Prior to the calculations done in Natarajan & Schwarz (2008), Belikov & Hooper (2009a) all the authors have only included the homogeneous DM component, i.e. have neglected the clustering effect. Despite the inclusion of the clustering there are some problems with the formalism of Belikov & Hooper (2009a); Natarajan & Schwarz (2008): the treatment for the evolution of the matter temperature is simplistic. Also, in Natarajan & Schwarz (2008), the optical depth![]() for the

for the ![]() -rays is calculated incorrectly. The original work by Padmanabhan & Finkbeiner (2005), and in particular, the extended newer version by Slatyer et al. (2009) uses more accurate formalism, unfortunately the authors have not included the effect of DM clustering.

-rays is calculated incorrectly. The original work by Padmanabhan & Finkbeiner (2005), and in particular, the extended newer version by Slatyer et al. (2009) uses more accurate formalism, unfortunately the authors have not included the effect of DM clustering.

During completion of our study couple of papers appeared calculating the diffuse ![]() -ray background due to the annihilating DM, e.g. Kawasaki et al. (2009), Profumo & Jeltema (2009), Belikov & Hooper (2009b). Kawasaki et al. (2009) have neglected the

-ray background due to the annihilating DM, e.g. Kawasaki et al. (2009), Profumo & Jeltema (2009), Belikov & Hooper (2009b). Kawasaki et al. (2009) have neglected the ![]() -rays from the inverse Compton scattering of the final state

-rays from the inverse Compton scattering of the final state

![]() ,

which gives even stronger bound than the primary

,

which gives even stronger bound than the primary ![]() -rays. Profumo & Jeltema (2009) have used different formalism for the absorption of

-rays. Profumo & Jeltema (2009) have used different formalism for the absorption of ![]() -rays considering the numerical approximation from Chen & Kamionkowski (2004). In this paper we include the relevant absorption processes directly (see the discussions below).

-rays considering the numerical approximation from Chen & Kamionkowski (2004). In this paper we include the relevant absorption processes directly (see the discussions below).

Our paper is organized as follows: In Sect. 2 we describe the source term, i.e. the energy input from the DM annihilation. In Sect. 3 we solve the radiative transfer equation and present a few example ![]() -ray spectra along with some results for the evolution of the ionization fraction and matter temperature. Section 4 presents our main results and our summary is given in Sect. 5.

-ray spectra along with some results for the evolution of the ionization fraction and matter temperature. Section 4 presents our main results and our summary is given in Sect. 5.

2 Energy input from DM annihilation

In our study we consider the DM annihilation to standard model charged leptons following the leptonic annihilation scenario presented in Cirelli et al. (2009). The final state distributions of electrons/positrons, photons, and neutrinos/antineutrinos from the primary two-body states produced in DM annihilations are computed using MonteCarlo code PYTHIA (Sjöstrand et al. 2008). The example final particle distributions for all three annihilation channels assuming the input DM particle with mass

![]() TeV are shown in Fig. 1. The partition of energy between final particles is shown in Table 1. The released electrons/positrons immediately interact with the CMB photons and upscatter those to high energies via the inverse Compton mechanism. Thus, in addition to the prompt photons released directly in the annihilation process, our photon spectrum contains the other part: the upscattered inverse Compton photons.

TeV are shown in Fig. 1. The partition of energy between final particles is shown in Table 1. The released electrons/positrons immediately interact with the CMB photons and upscatter those to high energies via the inverse Compton mechanism. Thus, in addition to the prompt photons released directly in the annihilation process, our photon spectrum contains the other part: the upscattered inverse Compton photons.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9.cm]{12760_f1.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/39/aa12760-09/Timg25.png) |

Figure 1:

The final state distributions of electrons/positrons, photons, and neutrinos/antineutrinos for the annihilating DM with

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

Table 1:

Energy partition between electrons/positrons, photons and neutrinos/antineutrinos for all three annihilation channels assuming

![]() GeV-10 TeV.

GeV-10 TeV.

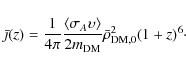

Having an annihilating DM particle with mass

![]() and with a thermally averaged cross-section

and with a thermally averaged cross-section

![]() the emitted power per volume and per steradian, i.e. the emission coefficient can be given as

the emitted power per volume and per steradian, i.e. the emission coefficient can be given as

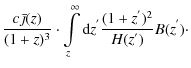

It is the emission coefficient for the homogeneous distribution of DM. To include the effect of DM clustering

where

![\begin{displaymath}f(c)=\frac{c^3}{3}\left[1-\frac{1}{(1+c)^3}\right]\left[\log(1+c)-\frac{c}{1+c}\right]^{-2}\cdot

\end{displaymath}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/39/aa12760-09/img37.png) |

(3) |

For the mass function we use the standard form given by Sheth & Tormen (1999), for the concentration parameter we use two models: (i) the model by Macciò et al. (2008), (ii) the power law model where

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm]{12760_f2.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/39/aa12760-09/Timg43.png) |

Figure 2:

( Upper panel) Boost factors B(z) as defined in Eq. (2)) for various concentration models. ( Lower panel) f-parameter as given by Eq. (10), i.e. the ratio of the total energy deposition and local ``smooth'' energy injection rates for two different concentration models and two leptonic annihilation channels, assuming the annihilating DM particle with mass

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

Using the boost factor we can write the total emission coefficient as

We also define the corresponding spectral quantity

where the frequency distribution function

For the inverse Compton scattering

![]() and for the prompt emission

and for the prompt emission

![]() .

.

3 Radiative transfer. Extragalactic gamma background. Reionization

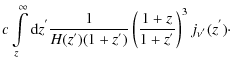

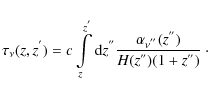

In the expanding Universe the formal solution of the radiative transfer equation for the intensity can be written in the form

Here

Here

- photoionization;

- compton scattering;

- photon-matter pair production;

- photon-photon scattering;

- photon-photon pair production.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9.cm]{12760_f3.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/39/aa12760-09/Timg65.png) |

Figure 3:

The redshift z' where the optical depth for photons reaches unity (i.e.,

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

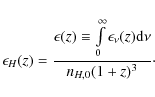

Having a method to calculate the intensity of the photon field sourced by the annihilating DM at each redshift we can go on and express the energy deposition rate in the cosmic medium as

| (8) |

To estimate the fraction of the deposited energy ending up in ionizing and heating the medium we use the approximation motivated by the original work of Shull & van Steenberg (1985) and used in several subsequent papers (Padmanabhan & Finkbeiner 2005; Zhang et al. 2006; Natarajan & Schwarz 2008; Chen & Kamionkowski 2004; Mapelli et al. 2006):

|

(9) |

To go beyond their ``on the spot'' approximation the f-parameter in their Eq. (5) should be replaced by the following function of z (see also Slatyer et al. 2009)

which gives us the ratio of the total energy deposition and local ``smooth'' energy injection rates. The function f(z) is plotted on the lower panel of Fig. 2 for two different concentration models, two leptonic annihilation channels (

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9.cm,clip]{12760_f4.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/39/aa12760-09/Timg76.png) |

Figure 4:

Example |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9.cm]{12760_f5.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/39/aa12760-09/Timg78.png) |

Figure 5:

The evolution of the ionization fraction ( upper panel) and matter temperature ( lower panel) for the model with the annihilating DM particle with mass

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

In Fig. 4 we show some example ![]() -ray spectra at redshift z=0 calculated with the above formalism for the annihilating DM particle with mass

-ray spectra at redshift z=0 calculated with the above formalism for the annihilating DM particle with mass

![]() TeV. Here the two most extreme concentration models of Fig. 2 have been used and the results are given for all three leptonic annihilation channels considered in this paper. The thermally averaged annihilation cross-section has been set to 25 times its standard value of

TeV. Here the two most extreme concentration models of Fig. 2 have been used and the results are given for all three leptonic annihilation channels considered in this paper. The thermally averaged annihilation cross-section has been set to 25 times its standard value of ![]()

![]() .

The low energy bump of the characteristic double-bumped spectrum is due to the inverse Compton process whereas the high energy bump is the prompt photon contribution. The points with errorbars correspond to the EGRET measurements of the extragalactic gamma background as given in Sreekumar et al. (1998). The solid horizontal line, which is used in the following as an upper bound for the level of diffuse

.

The low energy bump of the characteristic double-bumped spectrum is due to the inverse Compton process whereas the high energy bump is the prompt photon contribution. The points with errorbars correspond to the EGRET measurements of the extragalactic gamma background as given in Sreekumar et al. (1998). The solid horizontal line, which is used in the following as an upper bound for the level of diffuse ![]() -ray background, represents the EGRET measurements reduced by a factor of three to approximately account for the following: (i) dependent on the modeling details, it is predicted that from

-ray background, represents the EGRET measurements reduced by a factor of three to approximately account for the following: (i) dependent on the modeling details, it is predicted that from ![]() up to 100% of the diffuse extragalactic

up to 100% of the diffuse extragalactic ![]() -ray background is due to unresolved AGNs (Chiang & Mukherjee 1998; Mücke & Pohl 2000; Mukherjee & Chiang 1999; Stecker & Salamon 1996); (ii) the improved model for the Galactic contribution further suppresses the measurements (Strong et al. 2004); (iii) there is an additional component due to the DM annihilation produced in our own Galactic halo (see the relevant calculation by Kawasaki et al. 2009)

-ray background is due to unresolved AGNs (Chiang & Mukherjee 1998; Mücke & Pohl 2000; Mukherjee & Chiang 1999; Stecker & Salamon 1996); (ii) the improved model for the Galactic contribution further suppresses the measurements (Strong et al. 2004); (iii) there is an additional component due to the DM annihilation produced in our own Galactic halo (see the relevant calculation by Kawasaki et al. 2009)![]() .

.

Note that due to relatively small fraction of energy released in the form of prompt photons ![]() 2-4%, except for the

2-4%, except for the

![]() channel where the prompt photon part reaches up to

channel where the prompt photon part reaches up to ![]() 17%, the inverse Compton part of the spectrum has a higher amplitude than the prompt portion. As the observational bounds are represented by a roughly horizontal line it is clear that in the case of

17%, the inverse Compton part of the spectrum has a higher amplitude than the prompt portion. As the observational bounds are represented by a roughly horizontal line it is clear that in the case of

![]() and

and

![]() channels the constraint we obtain on

channels the constraint we obtain on

![]() arises from the inverse Compton portion only. However, for the

arises from the inverse Compton portion only. However, for the

![]() channel and for relatively low

channel and for relatively low

![]() ,

when the prompt bump of the spectrum reaches the energy range probed by EGRET, the constraint on

,

when the prompt bump of the spectrum reaches the energy range probed by EGRET, the constraint on

![]() is provided by the amplitude of the prompt portion, instead.

is provided by the amplitude of the prompt portion, instead.

In Fig. 5 we show an example of the evolution of the ionization fraction (upper panel) and matter temperature (lower panel) for the model with the annihilating DM particle with mass

![]() TeV and with a thermally averaged cross-section

TeV and with a thermally averaged cross-section

![]() .

The two most extreme concentration models of Fig. 2 have been used and for clarity only the results for the

.

The two most extreme concentration models of Fig. 2 have been used and for clarity only the results for the

![]() channel are shown. The lowest solid line plots the case where the structure boost has been neglected, i.e. B(z)=1 and the dashed line corresponds to the standard ``concordance'' cosmology without an annihilating DM. We have shown the evolution only down to redshift z=6 beyond which there is a clear observational evidence that the Universe gets fully ionized (Fan et al. 2006). In the lower panel the dotted line shows the evolution of the CMB temperature. Note that at

channel are shown. The lowest solid line plots the case where the structure boost has been neglected, i.e. B(z)=1 and the dashed line corresponds to the standard ``concordance'' cosmology without an annihilating DM. We have shown the evolution only down to redshift z=6 beyond which there is a clear observational evidence that the Universe gets fully ionized (Fan et al. 2006). In the lower panel the dotted line shows the evolution of the CMB temperature. Note that at

![]() the power law concentration model with

the power law concentration model with

![]() clearly starts to deviate from the smooth model without the clustering boost, resulting in an order of magnitude higher ionization fraction at low redshifts. However, if one calculates the optical depth to the last scattering then all of the models with DM annihilation plotted in Fig. 5 give very similar results, i.e. clustering boost at low z has minimal effect. In Belikov & Hooper (2009a) the authors discuss models where the DM annihilation is able to fully reionize the Universe at low redshifts. In our calculations we also find that, indeed, it is possible to fully reionize the Universe, however, all of those models give too large amplitudes for the ionization fraction plateau after

clearly starts to deviate from the smooth model without the clustering boost, resulting in an order of magnitude higher ionization fraction at low redshifts. However, if one calculates the optical depth to the last scattering then all of the models with DM annihilation plotted in Fig. 5 give very similar results, i.e. clustering boost at low z has minimal effect. In Belikov & Hooper (2009a) the authors discuss models where the DM annihilation is able to fully reionize the Universe at low redshifts. In our calculations we also find that, indeed, it is possible to fully reionize the Universe, however, all of those models give too large amplitudes for the ionization fraction plateau after

![]() and thus violate the CMB measurements.

and thus violate the CMB measurements.

4 Results

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9.cm,clip]{12760_f6.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/39/aa12760-09/Timg81.png) |

Figure 6:

Constraints from reionization and extragalactic gamma background for all three leptonic annihilation channels. The upper, middle, and lower panel correspond to

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

In this section we are going to confront the leptonically annihilating DM models with the observational data. We are going to use: (i) measurements of the extragalactic ![]() -ray background by EGRET (Sreekumar et al. 1998); (ii) measurement of the optical depth to the last scattering surface by WMAP (Dunkley et al. 2009). As described in the previous section, to account for the better Galactic subtraction due to Strong et al. (2004), for the annihilation signal from our own Galaxy, and for the contribution of AGNs to the

-ray background by EGRET (Sreekumar et al. 1998); (ii) measurement of the optical depth to the last scattering surface by WMAP (Dunkley et al. 2009). As described in the previous section, to account for the better Galactic subtraction due to Strong et al. (2004), for the annihilation signal from our own Galaxy, and for the contribution of AGNs to the ![]() -ray background, we use the upper bound of Sreekumar et al. (1998) reduced by a factor of three as our upper limit for the possible signal rising from the annihilating DM. This upper bound is shown as a solid horizontal line in Fig. 4.

-ray background, we use the upper bound of Sreekumar et al. (1998) reduced by a factor of three as our upper limit for the possible signal rising from the annihilating DM. This upper bound is shown as a solid horizontal line in Fig. 4.

To calculate the constraint from reionization we use the WMAP measurement for the optical depth:

![]() .

Using the spectra of distant quasars we know that most of the hydrogen in the Universe is ionized below redshift

.

Using the spectra of distant quasars we know that most of the hydrogen in the Universe is ionized below redshift ![]() (Fan et al. 2006). As was also done in Belikov & Hooper (2009a); Natarajan & Schwarz (2008) we assume that helium is singly ionized below z = 6 and doubly ionized below z=3. This assumption implies that the contribution to the WMAP optical depth from redshifts z>6 is

(Fan et al. 2006). As was also done in Belikov & Hooper (2009a); Natarajan & Schwarz (2008) we assume that helium is singly ionized below z = 6 and doubly ionized below z=3. This assumption implies that the contribution to the WMAP optical depth from redshifts z>6 is

![]() .

In the following we use the

.

In the following we use the ![]() upper bound

upper bound

![]() for deriving our constraints. The constraints we find on a

for deriving our constraints. The constraints we find on a

![]() plane for all three leptonic annihilation channels are given in Fig. 6. Here the upper, middle, and lower panel correspond to

plane for all three leptonic annihilation channels are given in Fig. 6. Here the upper, middle, and lower panel correspond to

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

and

,

and

![]() channels, respectively. As it turns out, our constraints from WMAP

channels, respectively. As it turns out, our constraints from WMAP ![]() measurements are basically independent of the low redshift clustering boost, implying that already the high redshift (i.e.

measurements are basically independent of the low redshift clustering boost, implying that already the high redshift (i.e.

![]() )

energy injection from the unclustered component is able to account for the measured level of

)

energy injection from the unclustered component is able to account for the measured level of

![]() .

.

We also note that, indeed, as pointed out in Belikov & Hooper (2009a) one can have models where the annihilating DM is able to fully reionize the Universe at low redshifts. However, we find that those models lead to the strong violation of the WMAP optical depth measurement due to the vastly increased level of the ionization fraction plateau beyond redshifts

![]() .

.

In Fig. 6 we have also plotted regions favored by the PFH data as given in Meade et al. (2009). We see that for the power law concentration model with

![]()

![]() and for all three annihilation channels the constraints from the extragalactic

and for all three annihilation channels the constraints from the extragalactic ![]() -ray background completely exclude the PFH favored region. This is also the case for the power law c(M) model with

-ray background completely exclude the PFH favored region. This is also the case for the power law c(M) model with

![]()

![]() ,

which for clarity is not shown in the figure. The WMAP

,

which for clarity is not shown in the figure. The WMAP ![]() constraint, which is insensitive to the structure boost, and thus does not depend on large uncertainties related to c(M), is able to rule out the PFH favored region of Meade et al. (2009) in the case of

constraint, which is insensitive to the structure boost, and thus does not depend on large uncertainties related to c(M), is able to rule out the PFH favored region of Meade et al. (2009) in the case of

![]() channel and also by a large part in the case of

channel and also by a large part in the case of

![]() annihilation channel. The excluded part of the Meade et al. (2009) favored region in the

annihilation channel. The excluded part of the Meade et al. (2009) favored region in the

![]() case is somewhat smaller.

case is somewhat smaller.

In addition to the extragalactic constraints in Fig. 6 we have also shown two types of Galactic bounds as found in Meade et al. (2009): (i) constraints derived from the HESS observations of the Galactic Center ![]() -rays (

-rays (

![]() angular region), plotted by dashed lines and labeled as GC-

angular region), plotted by dashed lines and labeled as GC-![]() ;

(ii) constraints from the FERMI observations of the

;

(ii) constraints from the FERMI observations of the ![]() -rays below 10 GeV in the

-rays below 10 GeV in the

![]() region (i.e., away from the Galactic Center), plotted by dotted lines and labeled as G-IC

region (i.e., away from the Galactic Center), plotted by dotted lines and labeled as G-IC![]()

![]() . Although both of those Galactic bounds shown here assumed NFW density profile, the G-IC

. Although both of those Galactic bounds shown here assumed NFW density profile, the G-IC![]() bound is less dependent on this assumption, as the observed region is away from the Galactic Center. It is evident that in several occasions the complementary extragalactic constraints derived in this work provide stronger bounds on annihilation cross-section, and thus are certainly of considerable interest.

bound is less dependent on this assumption, as the observed region is away from the Galactic Center. It is evident that in several occasions the complementary extragalactic constraints derived in this work provide stronger bounds on annihilation cross-section, and thus are certainly of considerable interest.

As a final point, note that our constraints based on diffuse extragalactic ![]() -ray background depend significantly on the assumed fraction of unresolved astrophysical sources contributing to the EGRET signal. There is a general consensus that a significant fraction of the diffuse signal is due to unresolved AGNs, however the predicted values are highly model dependent with the fractions ranging from 25% up to 100%. The upcoming measurements by Fermi satellite should clarify this situation considerably, since compared to EGRET, Fermi has significantly better sensitivity and angular resolution, allowing it to resolve many more individual astrophysical sources (Atwood et al. 2009).

-ray background depend significantly on the assumed fraction of unresolved astrophysical sources contributing to the EGRET signal. There is a general consensus that a significant fraction of the diffuse signal is due to unresolved AGNs, however the predicted values are highly model dependent with the fractions ranging from 25% up to 100%. The upcoming measurements by Fermi satellite should clarify this situation considerably, since compared to EGRET, Fermi has significantly better sensitivity and angular resolution, allowing it to resolve many more individual astrophysical sources (Atwood et al. 2009).

5 Summary

In this paper we have constrained observationally motivated leptonic DM annihilation scenario of Cirelli et al. (2009) using measurements of the extragalactic ![]() -ray background by EGRET space experiment (Sreekumar et al. 1998) and the measurement of the optical depth to decoupling by WMAP satellite (Dunkley et al. 2009). Our main results for all considered leptonic annihilation channels are given on three panels of Fig. 6 where we have also added the region favored by the PFH data as given in Meade et al. (2009).

-ray background by EGRET space experiment (Sreekumar et al. 1998) and the measurement of the optical depth to decoupling by WMAP satellite (Dunkley et al. 2009). Our main results for all considered leptonic annihilation channels are given on three panels of Fig. 6 where we have also added the region favored by the PFH data as given in Meade et al. (2009).

Here are our main conclusions:

- For the power law concentration model

the constraint from the extragalactic gamma background rules out the PFH favored region of Meade et al. (2009) for all three annihilation channels considered in this work.

the constraint from the extragalactic gamma background rules out the PFH favored region of Meade et al. (2009) for all three annihilation channels considered in this work.

- The same constraint in the case of Macciò et al. (2008) concentration model is significantly weaker owing to the much smaller structure formation boost as seen on the upper panel of Fig. 2. Compared to the mass of the smallest DM halos assumed in this work numerical simulations probe several orders of magnitude larger mass scales. The particular way one chooses to extrapolate the c(M) relation to smaller scales is currently arguably the biggest source of uncertainty for the annihilation-sourced

-ray background calculations.

-ray background calculations.

- For the minimal DM halo masses assumed in this paper the reionization constraints, on the other hand, turn out to be insensitive to the low redshift clustering boost, and thus are free of this large uncertainty in the mass-concentration relation. Thus these constraints are significantly more robust.

- The primary photons give important contribution to the derived constraints only in the case of

annihilation channel.

In the case of

annihilation channel.

In the case of

and

and

annihilation channels the constraints are mostly given by the IC scattering

photon flux.

annihilation channels the constraints are mostly given by the IC scattering

photon flux.

- For the

annihilation channel the constraints from reionization completely rule out the PFH favored region whereas for the

annihilation channel the constraints from reionization completely rule out the PFH favored region whereas for the

case large part of the region gets excluded. In the case of

case large part of the region gets excluded. In the case of

annihilation channel the excluded part is relatively small, but one has to keep in mind that in reality this channel does not provide a particularly good fit to the PFH data (Meade et al. 2009).

annihilation channel the excluded part is relatively small, but one has to keep in mind that in reality this channel does not provide a particularly good fit to the PFH data (Meade et al. 2009).

- In agreement to Belikov & Hooper (2009a) we find that, indeed, it is possible to have annihilating DM models that completely ionize the Universe at low redshifts. However, we find that those models result in a too high ionization fraction plateau at

,

leading to the optical depths which are incompatible with the WMAP measurements. Also, the annihilation cross-section one needs is somewhat larger than suggested by the PFH data.

,

leading to the optical depths which are incompatible with the WMAP measurements. Also, the annihilation cross-section one needs is somewhat larger than suggested by the PFH data.

- In the light of our results, the foreseen new diffuse

-ray data by Fermi satellite is expected to further constrain

the DM annihilation solutions to the cosmic ray anomalies.

-ray data by Fermi satellite is expected to further constrain

the DM annihilation solutions to the cosmic ray anomalies.

Acknowledgements

We thank Alessandro Strumia, Jens Chluba and Mario Kadastik for discussions and our Referee for useful comments and suggestions. This work was supported by the ESF Grants 8090, 8005, 7146 and by EU FP7-INFRA-2007-1.2.3 contract No 223807. GH acknowledges the support provided through a PPARC/STFC postdoctoral fellowship at UCL.

References

- Abdo, A. A., Ackermann, M., Ajello, M., et al. 2009, Phys. Rev. Lett., 102, 181101 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Adriani, O., Barbarino, G. C., Bazilevskaya, G. A., et al. 2009a, Nature, 458, 607 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Adriani, O., Barbarino, G. C., Bazilevskaya, G. A., et al. 2009b, Phys. Rev. Lett., 102, 051101 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Arkani-Hamed, N., Finkbeiner, D. P., Slatyer, T. R., et al. 2009, Phys. Rev., D79, 015014 [NASA ADS] (In the text)

- Atwood, W. B., Abdo, A. A., Ackermann, M., et al. 2009, ApJ, 697, 1071 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Belikov, A. V., & Hooper, D. 2009a [arXiv:0904.1210] (In the text)

- Belikov, A. V., & Hooper, D. 2009b [arXiv:0906.2251] (In the text)

- Bell, N. F., & Jacques, T. D. 2009, Phys. Rev. D, 79, 043507 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Bertone, G., Cirelli, M., Strumia, A., et al. 2009, JCAP, 0903, 009 [NASA ADS]

- Borriello, E., Cuoco, A., & Miele, G. 2009 [arXiv:0903.1852] (In the text)

- Bringmann, T. 2009 [arXiv:0903.0189] (In the text)

- Chang, J., Adams, J. H., Ahn, H. S., et al. 2008, Nature, 456, 362 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., & Kamionkowski, M. 2004, Phys. Rev. D, 70, 043502 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Chiang, J., & Mukherjee, R. 1998, ApJ, 496, 752 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Cirelli, M., & Panci, P. 2009 [arXiv:0904.3830] (In the text)

- Cirelli, M., Kadastik, M., Raidal, M., et al. 2009, Nucl. Phys. B, 813, 1 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Cooray, A., & Sheth, R. 2002, Phys. Rep., 372, 1 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Dunkley, J., Komatsu, E., Nolta, M. R., et al. 2009, ApJS, 180, 306 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Fan, X., Carilli, C. L., & Keating, B. 2006, ARA&A, 44, 415 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Galli, S., Iocco, F., Bertone, G., et al. 2009 [arXiv:0905.0003] (In the text)

- HESS Collaboration: F. Aharonian. 2009 [arXiv:0906.2002]

- Kawasaki, M., Kohri, K., & Nakayama, K. 2009 [arXiv:0904.3626] (In the text)

- Macciò, A. V., Dutton, A. A., & van den Bosch, F. C. 2008, MNRAS, 391, 1940 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Mapelli, M., Ferrara, A., & Pierpaoli, E. 2006, MNRAS, 369, 1719 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Martinez, G. D., Bullock, J. S., Kaplinghat, M., Strigari, L. E., & Trotta, R. 2009, Journal of Cosmology and Astro-Particle Physics, 6, 14 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Meade, P., Papucci, M., Strumia, A., et al. 2009 [arXiv:0905.0480] (In the text)

- Mücke, A., & Pohl, M. 2000, MNRAS, 312, 177 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, R., & Chiang, J. 1999, Astroparticle Phys., 11, 213 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, A., & Schwarz, D. J. 2008, Phys. Rev. D, 78, 103524 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Navarro, J. F., Frenk, C. S., & White, S. D. M. 1997, ApJ, 490, 493 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Padmanabhan, N., & Finkbeiner, D. P. 2005, Phys. Rev. D, 72, 023508 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Profumo, S., & Jeltema, T. E. 2009 [arXiv:0906.0001] (In the text)

- Seager, S., Sasselov, D. D., & Scott, D. 1999, ApJ, 523, L1 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Sheth, R. K., & Tormen, G. 1999, MNRAS, 308, 119 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Shull, J. M., & van Steenberg, M. E. 1985, ApJ, 298, 268 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Sjöstrand, T., Mrenna, S., & Skands, P. 2008, Comp. Phys. Communic., 178, 852 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Slatyer, T. R., Padmanabhan, N., & Finkbeiner, D. P. 2009 [arXiv:0906.1197] (In the text)

- Sreekumar, P., Bertsch, D. L., Dingus, B. L., et al. 1998, ApJ, 494, 523 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Stecker, F. W., & Salamon, M. H. 1996, ApJ, 464, 600 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Strong, A. W., Moskalenko, I. V., & Reimer, O. 2004, ApJ, 613, 956 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Torii, S., Yamagami, T., Tamura, T., et al. 2008 [arXiv:0809.0760]

- Zdziarski, A. A., & Svensson, R. 1989, ApJ, 344, 551 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Zhang, L., Chen, X., Lei, Y.-A., & Si, Z.-G. 2006, Phys. Rev. D, 74, 103519 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

Footnotes

- ... surface

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- In the following the observational constraint derived from the Thompson scattering optical depth is called the ``reionization constraint''.

- ... depth

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- The argument of

in their Eq. (17).

in their Eq. (17).

- ... simulations

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- For similar comments on uncertainties related to the mass dependence of the concentration parameter see e.g. Martinez et al. (2009).

- ...Kawasaki et al. 2009)

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- If the Reader has her/his own favored value for the possible reduction factor the final results in Fig. 6 are easily scalable to accommodate that, since the DM annihilation signal is simply proportional to

.

.

- ...

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- At those lower energies the Inverse Compton part of the annihilation

-spectrum dominates.

-spectrum dominates.

All Tables

Table 1:

Energy partition between electrons/positrons, photons and neutrinos/antineutrinos for all three annihilation channels assuming

![]() GeV-10 TeV.

GeV-10 TeV.

All Figures

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9.cm]{12760_f1.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/39/aa12760-09/Timg25.png) |

Figure 1:

The final state distributions of electrons/positrons, photons, and neutrinos/antineutrinos for the annihilating DM with

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm]{12760_f2.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/39/aa12760-09/Timg43.png) |

Figure 2:

( Upper panel) Boost factors B(z) as defined in Eq. (2)) for various concentration models. ( Lower panel) f-parameter as given by Eq. (10), i.e. the ratio of the total energy deposition and local ``smooth'' energy injection rates for two different concentration models and two leptonic annihilation channels, assuming the annihilating DM particle with mass

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9.cm]{12760_f3.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/39/aa12760-09/Timg65.png) |

Figure 3:

The redshift z' where the optical depth for photons reaches unity (i.e.,

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9.cm,clip]{12760_f4.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/39/aa12760-09/Timg76.png) |

Figure 4:

Example |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9.cm]{12760_f5.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/39/aa12760-09/Timg78.png) |

Figure 5:

The evolution of the ionization fraction ( upper panel) and matter temperature ( lower panel) for the model with the annihilating DM particle with mass

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9.cm,clip]{12760_f6.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/39/aa12760-09/Timg81.png) |

Figure 6:

Constraints from reionization and extragalactic gamma background for all three leptonic annihilation channels. The upper, middle, and lower panel correspond to

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

Copyright ESO 2009

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.

![\begin{displaymath}

B(z)=1+\frac{\Delta_c}{3\bar{\rho}_{m,0}}\int\limits_{M_{\rm...

...ty}{\rm d}M\frac{{\rm d}n}{{\rm d}M}(M,z)f\left[c(M,z)\right],

\end{displaymath}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/39/aa12760-09/img32.png)