| Issue |

A&A

Volume 505, Number 1, October I 2009

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Page(s) | 21 - 28 | |

| Section | Cosmology (including clusters of galaxies) | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/200911992 | |

| Published online | 24 July 2009 | |

Testing an exact f(R)-gravity model at Galactic and local scales

S. Capozziello - E. Piedipalumbo - C. Rubano - P. Scudellaro

Dipartimento di Scienze Fisiche, Università Federico II di Napoli and INFN - Sez. di Napoli, Complesso Universitario di Monte S. Angelo, via Cinthia, Ed. 6, 80126 Napoli, Italy

Received 6 March 2009 / Accepted 24 June 2009

Abstract

Context. The weak field limit for a pointlike source of a

![]() -gravity model is studied.

-gravity model is studied.

Aims. We aim to show the viability of such a model as a valid alternative to GR + dark matter at Galactic and local scales.

Methods. Without considering dark matter, within the weak field approximation, we find general exact solutions for gravity with standard matter, and apply them to some astrophysical scales, recovering the consistency of the same f(R)-gravity model with cosmological results.

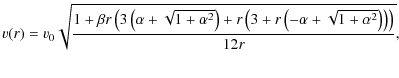

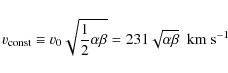

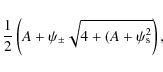

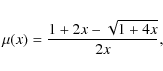

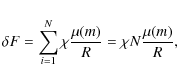

Results. In particular, we show that it is possible to obtain flat rotation curves for galaxies, and consistency with Solar System tests, as in the so-called ``Chameleon approach''. In fact, the peripheral velocity ![]() is shown to be expressed as

is shown to be expressed as

![]() ,

so that the Tully-Fisher relation is recovered.

,

so that the Tully-Fisher relation is recovered.

Conclusions. The results point out the possibility of achieving alternative theories of gravity in which exotic ingredients like dark matter and dark energy are not necessary, while their coarse-grained astrophysical and cosmological effects can be related to a geometric origin.

Key words: gravitation - Galaxy: fundamental parameters - solar system: general - cosmology: dark matter - gravitation lensing

1 Introduction

Alternative theories of gravity (Peebles & Ratra 2003;

Padmanabhan 2003; Copeland et al. 2006)

are increasing as possible suitable alternatives to dark energy

and dark matter. Although the ![]() CDM model is affected by

many theoretical shortcomings (Carroll et al. 1992),

and, in general, dark energy models are mainly based on the

implicit assumption that Einstein's general relativity (GR) is the

correct theory of gravity. But the validity of GR both on large

astrophysical and cosmological scales still remains to be

accurately tested (see e.g. Will 2006), and there is still

enough room to propose different theoretical schemes. A

minimal alternative choice could be to take into account

generic functions f(R) of the Ricci scalar curvature R. The

task for these extended theories is to fit the astrophysical data

without adding exotic dark ingredients (Kleinert & Schmidt 2002; Capozziello 2002; Capozziello et al. 2003a, b; Odintsov & Nojiri 2003; Carroll et al.

2004; Allemandi et al. 2004; Nojiri &

Odintsov 2004; Cognola et al. 2005;

Capozziello & Francaviglia 2008).

CDM model is affected by

many theoretical shortcomings (Carroll et al. 1992),

and, in general, dark energy models are mainly based on the

implicit assumption that Einstein's general relativity (GR) is the

correct theory of gravity. But the validity of GR both on large

astrophysical and cosmological scales still remains to be

accurately tested (see e.g. Will 2006), and there is still

enough room to propose different theoretical schemes. A

minimal alternative choice could be to take into account

generic functions f(R) of the Ricci scalar curvature R. The

task for these extended theories is to fit the astrophysical data

without adding exotic dark ingredients (Kleinert & Schmidt 2002; Capozziello 2002; Capozziello et al. 2003a, b; Odintsov & Nojiri 2003; Carroll et al.

2004; Allemandi et al. 2004; Nojiri &

Odintsov 2004; Cognola et al. 2005;

Capozziello & Francaviglia 2008).

In such a context, these higher order theories have obtained considerable attention in cosmology, since they seem to work well both in the late and in the early universe (see Capozziello 2002; Capozziello et al. 2003a, b; Odintsov & Nojiri 2003; Carroll et al. 2004; Allemandi et al. 2004; Nojiri & Odintsov 2004; Cognola et al. 2005; Capozziello & Francaviglia 2008). It is also possible to show that f(R)theories can play a major role at astrophysical scales, due to the modifications of the gravitational potential in the low energy limit. Such a corrected potential reduces to the Newtonian one at the Solar System scale and could also offer the possibility of fitting galaxy rotation curves and galaxy cluster potentials without the need for large amounts of dark matter (Capozziello et al. 2004,2006,2007a,2009; Milgrom 1983, Bekenstein 2004; Sobouti 2007; Frigerio Martins & Salucci 2007; Mendoza & Rosas-Guevara 2007). However, extending the gravitational Lagrangian may give rise to many problems. These theories may have instabilities (Faraoni 2005; Cognola & Zerbini 2006; Cognola et al. 2007), ghost-like behavior (Stelle 1978), and they still need to be matched with data from the low energy limit experiments that are well understood by GR.

In summary, adopting f(R)-gravity leads to interesting results, first of all at cosmological and galactic scales, even if, up to now, it has not been possible to select only one theory (or class of theories) good at all scales. There has been much work on this (Capozziello et al. 2005; Hu & Sawicki 2007; Starobinsky 2007; Nojiri & Odintsov 2007), but all the approaches are indeed phenomenological and are not based on a fundamental conservation or invariance principle of the theory.

In this paper, we propose a specific expression of the function

f(R) of the Ricci scalar curvature R, namely![]() f(R) =-|-R|3/2, which comes

from the need for the existence of a Noether symmetry for f(R)cosmological models (de Ritis et al. 1990; Capozziello

et al. 2008). The cosmological solutions of the

Einstein field equations related to such a choice for f(R) have

been analyzed in Capozziello et al. (2008), and it

turned out that this model admits a dust-dominated decelerated

phase, before a late time accelerated phase, as needed by the

observational data. Here, we study the low energy limit of such a

solution, in the case of a point-like source. We consider the

Schwarzschild-like spherically symmetric metric in such a way

that, in the weak field limit, the Newtonian potential is modified

by adding a logarithmic term. A similar treatment has been

proposed in Sobouti (2007), where instead the starting

point consists of introducing a specific hypothesis on the metric

and thereby deducing the form of f(R) (resulting in a

power-law), so fitting observational data on speeds of peripheral

stars in spiral galaxies, as first reported in Sanders & McGough

(2002) and then selected in Sobouti (2007).

Unfortunately, this procedure leads to a very peculiar choice of

f(R). It contains parameters which must be adjusted to the mass

of the gravitational source. Therefore, f(R) cannot be

universal.

f(R) =-|-R|3/2, which comes

from the need for the existence of a Noether symmetry for f(R)cosmological models (de Ritis et al. 1990; Capozziello

et al. 2008). The cosmological solutions of the

Einstein field equations related to such a choice for f(R) have

been analyzed in Capozziello et al. (2008), and it

turned out that this model admits a dust-dominated decelerated

phase, before a late time accelerated phase, as needed by the

observational data. Here, we study the low energy limit of such a

solution, in the case of a point-like source. We consider the

Schwarzschild-like spherically symmetric metric in such a way

that, in the weak field limit, the Newtonian potential is modified

by adding a logarithmic term. A similar treatment has been

proposed in Sobouti (2007), where instead the starting

point consists of introducing a specific hypothesis on the metric

and thereby deducing the form of f(R) (resulting in a

power-law), so fitting observational data on speeds of peripheral

stars in spiral galaxies, as first reported in Sanders & McGough

(2002) and then selected in Sobouti (2007).

Unfortunately, this procedure leads to a very peculiar choice of

f(R). It contains parameters which must be adjusted to the mass

of the gravitational source. Therefore, f(R) cannot be

universal.

Here, we find results that are very similar to those in Sobouti (2007) from the observational point of view, but do not exhibit the above problems. In this preliminary work, we only consider the weak field generated by a point-like source. Clearly, shrinking a whole galaxy (or cluster) to a point is a very crude approximation. Our aim, therefore, is to show that the model can nonetheless work, without trying to obtain a strict correspondence with observations.

The treatment of point-like source in f(R) theories is non-trivial and, in a sense, can be considered an ill posed problem. The reason is that we cannot disregard the properties of the extended object that is generating the field. Unlike what happens in GR, the choice of the integration constants is not necessarily independent of its peculiarities, like density, equation of state etc. We should therefore solve the equations for the inner metric and then match with the exterior. This procedure is valid for a star but much less meaningful for a galaxy. In any case, we do not expect to have a full prediction of their functional dependence. In fact, also in standard GR the linear dependence on mass of the constant is obtained only from the observational link with Newtonian gravity. This link with observations is precisely what is lacking in the case of stars, and is only preliminarily studied here. Therefore, in the following we retain the assumption of point-like source, dedicating Sect. 6 to a deeper discussion on this point.

There is another limit of the analysis presented here, lying in the weak field approximation assumed from the beginning. The asymptotic Minkowskyian behavior cannot recovered and, most of all, does not shed light on the singularities of the metric. It is therefore not possible to say what are the modifications of a black hole so generated.

In Sect. 2, we work out the basic equations of our model, and in Sect. 3 we study peripheral speeds in spirals. In Sect. 4, we discuss some tests in the Solar System and, in Sect. 5, we comment on gravitational lensing and MOND. In Sect. 6 the connection between the law for a pontlike source and an extended body is briefly discussed. In Sect. 7, we give our conclusions.

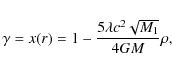

2 Weak field approximation

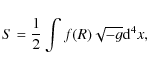

Our theory of gravity is determined by the Action:

where R is the Ricci scalar and we define f(R)=-|-R|3/2.

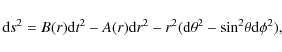

As said above, we consider a static, spherically symmetric metric,

which will differ from the standard Schwarzschild form, due to the

different starting equations. We thus set:

with A(r) and B(r) radial functions to be determined through the modified Einstein field equations.

It is important to observe that, as the angular coordinates are

dimensionless, we also use a dimensionless distance, so that we

have:

| (3) |

where

Proceeding in this way, all quantities are dimensionless,

including R and the result for velocities. In order to restore

the appropriate dimensions, we should therefore multiply by an

appropriate fundamental Action, i.e. some numerical multiple of

![]() .

As we are in vacuum, this clearly does not affect the

equations and their solution. On the other hand, this constant is

of course not irrelevant and has an influence on the coupling with

the test particle (peripheral star or other object). In our case

this arbitrariness will be resolved by restoring the physical

units in an appropriate way when defining the observational

objects and fixing the constant C3 (see below), with the

prescription that we should obtain ordinary Newtonian gravity at

small scales.

.

As we are in vacuum, this clearly does not affect the

equations and their solution. On the other hand, this constant is

of course not irrelevant and has an influence on the coupling with

the test particle (peripheral star or other object). In our case

this arbitrariness will be resolved by restoring the physical

units in an appropriate way when defining the observational

objects and fixing the constant C3 (see below), with the

prescription that we should obtain ordinary Newtonian gravity at

small scales.

In a weak field, of course, the functions A(r) and B(r) are

practically identified by means of their corrections to what we

expect in the Newtonian case for astrophysical situations. First

trying to understand how we can modify the Newtonian potential, we

write the first function as

![]() ,

where

,

where ![]() is a suitable small

parameter. Analogously, we also assume

is a suitable small

parameter. Analogously, we also assume

![]() .

Being in a weak field, r cannot

extend to infinity, but we must have

.

Being in a weak field, r cannot

extend to infinity, but we must have

![]() and

and

![]() .

.

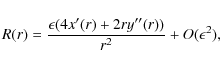

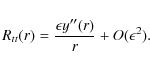

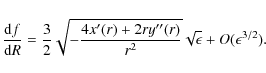

We can obtain our results depending on r, as for instance:

where prime denotes a derivative with respect to r. It is also:

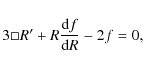

To write equations, we have to vary the Action S with respect to the metric tensor, always remembering that we are studying an approximate situation. We also need to note that

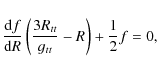

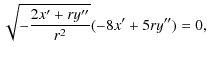

The master equation is:

that is:

while the trace equation is given by:

which is equivalent to:

|

(10) |

Neglecting higher order terms and dividing the master equation by

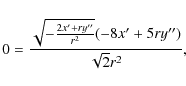

Such equations appear only difficult to handle, since Eq. (11) can be algebraically solved for

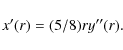

Substitution of this expression and its derivatives in Eq. (12) leads to the general exact solution:

| y(r) | = | ||

| (14) |

where C1, C2, C3, and C4 are arbitrary (complex) constants. If we limit ourselves to considering C2, C3, and C4 as real constants, we can understand that posing

| y(r) | = | ||

| (15) |

Here, the constant C4 is multiplied by r and, since the potential is obtained from y(r)/r, it gives rise to a constant term. So, we can set C4=0 in the following. On the other hand, the presence of a term giving the Newtonian potential explicitly depends on C3, which then needs to be nonzero.

From now on, ![]() will be incorporated into the integration

constants without any loss of generality.

will be incorporated into the integration

constants without any loss of generality.

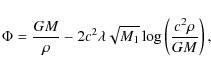

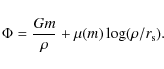

3 Peripheral speeds

We are now in a position to study how the speed of a test star

behaves at the periphery of a pointlike galaxy in our

model (i.e. at large distances from a point source of great

mass), once it is subjected to the dimensionless potential

![]() .

We write the speed v of a

generic test star in this potential. Remembering that the quantity

under the square root is dimensionless, we adjust the dimensions

by means of the light speed c. This will fix the numerical

values of the constants:

.

We write the speed v of a

generic test star in this potential. Remembering that the quantity

under the square root is dimensionless, we adjust the dimensions

by means of the light speed c. This will fix the numerical

values of the constants:

The comparison with the Newtonian case is obtained when

with

The first assumption is

![]() ,

which clearly is arbitrary

and can be justified only a posteriori.

,

which clearly is arbitrary

and can be justified only a posteriori.

When

![]() ,

the expression under the square

root reduces to

,

the expression under the square

root reduces to

![]() .

In

fact, we find a correction of what is usually expected in the

Newtonian case, since the first term is the Keplerian one, the

third gives a constant speed, and the second must stay small. The

reason is that, as said above, we must keep

.

In

fact, we find a correction of what is usually expected in the

Newtonian case, since the first term is the Keplerian one, the

third gives a constant speed, and the second must stay small. The

reason is that, as said above, we must keep

![]() .

This

means that, even if

.

This

means that, even if

![]() ,

,

![]() must be small. However,

it cannot simply be set to zero, for this would also remove the

other correction term.

must be small. However,

it cannot simply be set to zero, for this would also remove the

other correction term.

The second assumption is therefore that ![]() ,

being so small

with respect to

,

being so small

with respect to ![]() ,

we can safely neglect the increasing

term. A rough estimate of the relevant correction term for a

galaxy is:

,

we can safely neglect the increasing

term. A rough estimate of the relevant correction term for a

galaxy is:

(where we have considered

Being dimensionless quantities, ![]() and

and ![]() can be

universal numbers or arbitrary functions of

can be

universal numbers or arbitrary functions of

![]() ,

i.e. the only number we can form with the physical quantities at

our disposal. But this is true only in the point-like source

model. Another dimensionless quantity that can be considered for

an extended body is of course its radius, again divided by

,

i.e. the only number we can form with the physical quantities at

our disposal. But this is true only in the point-like source

model. Another dimensionless quantity that can be considered for

an extended body is of course its radius, again divided by ![]() ,

and many others.

,

and many others.

The third third assumption is thus that we consider ![]() and

and

![]() slowly varying with respect to these kinds of parameters.

In other words, we expect a difference to appear only when a very

large change of scale is considered, e.g. passing from the Galaxy

to the Solar System, which is discussed in Sect. 6.

slowly varying with respect to these kinds of parameters.

In other words, we expect a difference to appear only when a very

large change of scale is considered, e.g. passing from the Galaxy

to the Solar System, which is discussed in Sect. 6.

The scale radius ![]() ,

having only the function of fixing the

units, can be chosen arbitrarily and we set it as a multiple of

the Schwarzschild radius,

,

having only the function of fixing the

units, can be chosen arbitrarily and we set it as a multiple of

the Schwarzschild radius,

![]() ,

K being an

unspecified positive (large) number (if K is kept fixed, then

,

K being an

unspecified positive (large) number (if K is kept fixed, then

![]() is chosen according to the first issue (see above); if, on

the contrary, we want

is chosen according to the first issue (see above); if, on

the contrary, we want ![]() to be specific, we may suitably

adjust the value of K. We shall see that this makes no

difference).

to be specific, we may suitably

adjust the value of K. We shall see that this makes no

difference).

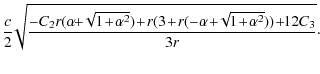

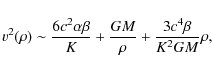

We thus get:

that is, a constant term and a Keplerian one, plus one increasing contribution which can be neglected for sufficiently small

Any attempt to modify the Newtonian law, on the Galactic scale,

has to cope with the justification of the Tully-Fisher empirical

relation. This obliges one to set the parameters of the modified

part as depending on the mass of the source, which is impossible

if one starts from a universal modification. On the contrary, it

is appropriate here, where the parameters are specific to the

problem. This is indeed a very good feature of our approach.

Moreover, we have complete freedom in the choice of the

dependance. A reasonable assumption is to set

![]() proportional to some power of the mass M,

made dimensionless by dividing by a suitable reference mass. Thus,

we define

proportional to some power of the mass M,

made dimensionless by dividing by a suitable reference mass. Thus,

we define

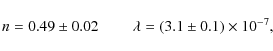

![]() ,

where n is a

pure number and M1 is referred to

,

where n is a

pure number and M1 is referred to

![]() .

(Such

a definition of

.

(Such

a definition of ![]() is the same as the one for the parameter

is the same as the one for the parameter

![]() in Sobouti (2007).

in Sobouti (2007).

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{11992fig1}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/37/aa11992-09/Timg76.png) |

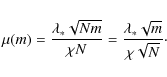

Figure 1:

Fit of Eq. (21) versus data in Sanders & McGough

(2002) as selected in Sobouti (2007). On the

x-axis, masses of luminous matter in units of

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

If we neglect the term linear in ![]() ,

we find:

,

we find:

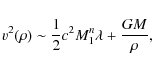

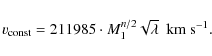

which coincides with the relevant part of the expression found in Sobouti (2007). On the other hand, the constant term can be written as:

A determination of

compatible with n=0.5 at

which is the phenomenological Tully-Fisher relation. We have thus proved that even in this crude model the flatness of the rotation curves can be obtained (a more detailed verification would require to treat the galaxy as an extended object); the immediate question to answer is now the validity of the theory at the Solar System level.

4 Solar System tests

4.1 Kepler's law

We now use the result of the above section for in the Solar

System, with the slight simplification n = 1/2. This is a major

extrapolation, as nothing guarantees that a semi-empirical law

like

![]() can be

used properly at such different scales, with the same values for

the parameters. Possible arguments against this are:

can be

used properly at such different scales, with the same values for

the parameters. Possible arguments against this are:

- The power law guess may be not the right one. It could

indeed be more complicated and show effects at small scales.

- We do not know whether

at the Solar

System level or not.

at the Solar

System level or not.

- The parameters used for the Solar System tests are those

used for galaxies, and they are already roughly estimated there.

- The values used for G and

are the standard

ones, which is not certain, since they are estimated within the

Newtonian framework.

are the standard

ones, which is not certain, since they are estimated within the

Newtonian framework.

- The orbits of the planets around the Sun are only

approximately circular.

- The Solar System is a many body system, where perturbations

should be accurately taken into account. (The observed deviations

from Kepler's laws are in fact explained by the existence of

perturbations induced by other planets.)

- The passage from a pointlike source to an extended one is

not trivial, as said above. This point seems the most important

and is treated specifically below.

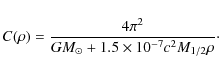

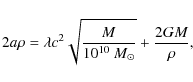

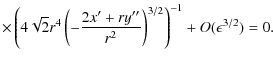

In the Solar System we can also test Kepler's third law

![]() (with T the period and C0 a

constant), where:

(with T the period and C0 a

constant), where:

and if we use

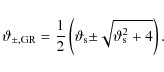

The observed values of C0 and those obtained from Eq. (25) for Solar System planets are plotted in Fig. 2 against the semimajor axes of the planet orbits. The deviation from observation is made evident by the absence of the downwards trend, which is instead obtained from Eq. (25). However, this is not a conclusive argument, as the trend could be altered by the complicated effects of the many body system.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{11992fig2}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/37/aa11992-09/Timg93.png) |

Figure 2:

Comparison between the values of the observed C0s for the planets of the Solar System and what is obtained

through Eq. (25). x-axis: the semi-major axes |

| Open with DEXTER | |

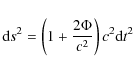

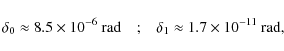

4.2 PPN parameter

In the study of modified (with respect to GR) approaches to

gravitational physics, it is usual to ask which are the new values

for the PPN parameters, in particular of the most important and

studied ![]() ,

which must be very near to 1 in the Solar

System (and exactly 1 in GR).

,

which must be very near to 1 in the Solar

System (and exactly 1 in GR).

Since we have developed our weak field approximation only up to

the first order, there is some doubt about the applicability of

the formalism. We have a modification of the A(r) function in

the metric via the function ![]() ,

so that we may set:

,

so that we may set:

finding:

Thus,

The reason why we do not use the conformal transformation to pass to Einstein frame is that the equivalence can be lost in the case of the weak field approximation due to the fact that a f(R)-fourth-order theory has different gauge conditions in this limit with respect to a second-order Einstein theory plus a scalar field, which could lead to unphysical results. For a detailed discussion of this point see Capozziello et al. (2007b). In order to avoid this, we adopted the Jordan frame for all calculations.

We obtain a value for ![]() which is not the same throughout

the Solar System. On the other hand, the numerical codes that give

an estimate of the PPN parameters are based on constant values. A

precise computation should instead take this feature into account.

We conclude that the transport of the correction as it is at the

Solar System level seems to be unsatisfactory. In Sect. 5 this

problem will be addressed by the introduction of a ``Chameleon''

mechanism.

which is not the same throughout

the Solar System. On the other hand, the numerical codes that give

an estimate of the PPN parameters are based on constant values. A

precise computation should instead take this feature into account.

We conclude that the transport of the correction as it is at the

Solar System level seems to be unsatisfactory. In Sect. 5 this

problem will be addressed by the introduction of a ``Chameleon''

mechanism.

5 Other tests

Still fixing, for simplicity, n=1/2, we also set K=1 as it introduces a constant term in the potential, which is clearly irrelevant.

5.1 Gravitational lensing

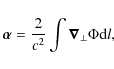

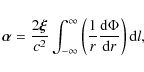

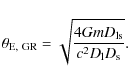

Because it is intimately related to the underlying theory of gravity in its Einstein formulation, modifying the Lagrangian of the gravitational field also affects the theory of gravitational lensing. We therefore investigate how gravitational lensing works in the framework of higher order theories of gravity. On the one hand, one has to verify that the phenomenology of gravitational lensing is preserved in order to not contradict those observational results that do agree with the predictions of the standard theory of lensing. On the other hand, it is worth exploring whether deviations from classical results of the main lensing quantities could be detected and work as clear signatures of a modified theory of gravity. As a first step towards such an ambitious task, here we investigate how modifying gravity affects the gravitational lensing in the case of a point-like lens.

Indeed, the basic assumption in deriving the lens equation is

that the gravitational field is weak and stationary. In this case,

the spacetime metric reads:

where

with:

where

with

Assuming the potential only depending on

![]() (as for a point-like or a spherically symmetric

lens), the deflection angle reduces to

(as for a point-like or a spherically symmetric

lens), the deflection angle reduces to

where we have assumed that the geometric optics approximation holds, the light rays are paraxial and propagate from infinite distance. Equation (32) allows us to evaluate the deflection angle, provided that the source mass distribution and the theory of gravity have been assigned, so that one may determine the gravitational potential. Here, we consider only the case of the point-like lens. Note that, although being the simplest one, the point-like lens is the standard approximation for stellar lenses in microlensing applications (e.g. see Schneider et al. 1992). Moreover, since in the weak field limit

In the approximation of small deflection angles, simple

geometrical considerations allow us to write the lens equation as

which gives the position

where we should remember that M1 is measured in units of

The first term yields, of course, the usual deviation:

where

which is independent of

so that the correction is irrelevant. On the other hand, in the case of a galaxy, assuming M1=1 and

so that the correction now dominates and induces an overestimation of the mass, if the deviation is instead attributed in the usual way

The point-like lens equation differs from the standard general

relativistic one for the second term (36). Should this term

be negligible, all the usual results of gravitational lensing are

recovered. It is therefore interesting to investigate in detail

how the corrective term affects the estimate of observable related

quantities since, should they be detectable, they could represent

a signature of R3/2 gravity. Since we are considering the

pointlike lens, a typical lensing system is represented by a

compact object (both visible or not) in the Galaxy halo acting as

a lens for the light rays coming from a stellar source in an

external galaxy, like the Magellanic Clouds (LMC and SMC) or

Andromeda. It is easy to show that, in such a configuration, the

standard Einstein angle

![]() and the image angular

separation are of the order of a few

and the image angular

separation are of the order of a few

![]() arcsec,

so that we are in the regime known as microlensing (see

Mollerach & Roulet 2002).

arcsec,

so that we are in the regime known as microlensing (see

Mollerach & Roulet 2002).

In the standard case the lens equation may be solved

analytically and one gets two images with positions given by

In the current case, the the lens equation may be conveniently written as

with

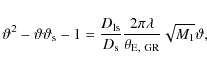

We still get two images on the opposite sides of the lens, with one image lying inside and the other one outside the Einstein ring. The geometric configuration is therefore the same as in the standard case, but the positions are slightly changed. The images positions are given by

with

To quantify this effect, we evaluate the percentage deviation

relative to the Einstein case.

![]() ,

which differs from

,

which differs from

![]() .

.

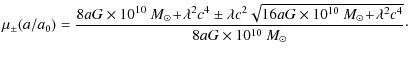

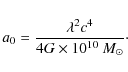

5.2 Equivalence with MOND

Following Sobouti (2007), we want now to show that our

model is effectively equivalent to the well known MOND theory (see

Milgrom 1983; Bekenstein 2004), which

postulates a modification of Newtonian dynamics:

where

F is the usual gravitational force

In our case, we have that the asymptotically constant peripheral

velocity

![]() can be inserted into the formula for the

centripetal acceleration

can be inserted into the formula for the

centripetal acceleration

so that using our expression in Eq. (20) for

from which we can extract M and insert it into the expression of

There are two solutions, and we therefore obtain the functions:

A first important remark is that

From the MOND estimate of a0 we then find

in very good agreement with the result extracted from the above fit.

The great advantage of this formulation is that we obtain the universal

function:

which can be tested.

6 Point-like and extended bodies

As discussed in previous sections, considering the corrections to the potential from galaxies to Solar System scales, with the same values of parameters, is rather unsatisfactory. Here we want to discuss possible explanations and take into account also extended bodies.

First, both the Sun and a galaxy are not point-like sources. In

the case of the Sun, however, assuming spherical symmetry and

neglecting as usual the rotational contribution, we may still use

the rotational invariant form of the metric in Eq. (2).

There are important differences if the source is not point-like:

other elements may enter in the computation of the integration

constant, for instance the radius of the object. The correct

treatment would be to solve for the internal metric and join it

smoothly with the external one, so as to take care of the change

in density with radius. A reasonable approximation would be to

assume a uniform density, so that only radius could be involved.

Moreover, we may consider for the moment all stars as being equal

to the Sun, so that the correction to the potential can be

expressed again in terms of the mass

Here, m is the mass of the star,

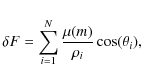

The situation is very different for a spiral galaxy, first, because it is not spherical and second because it is not a continuous distribution of mass. Thus, the correct procedure would be to start from a metric with cylindrical symmetry, and to solve the resulting fourth order equations. A very rough attempt would consist of computing the force acting on a test particle near the edge of the disk, by considering the galaxy as made up of, say, 1010 stars like the Sun, (without either bulge or intergalactic dust, which is indeed very crude), and adding the forces.

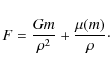

The force acting on a unit mass test particle is therefore

Let the test particle be situated on the x-axis, for instance (and of course on the galactic plane), R be the radius of the disk, and N the number of stars. The first term gives the usual Newtonian force, so that we only have to sum the correction. Due to the non linearity of the dependence on the mass, this is not a straightforward task. We give here just a rough estimate (a more precise computation can be made and gives the same answer).

Because of the symmetry, the total force is clearly directed

towards the center, so that we need to compute only the x

component. The correction is

but, since

where

where

Remembering that

The main problem of this argument lies not so much in the rough

estimate of ![]() ,

but in the fact that the number of stars is

not the same for all galaxies, and that the stars may be very

different in mass and size. A more satisfactory computation should

be done starting from Eq. (52), with a reasonable guess for

,

but in the fact that the number of stars is

not the same for all galaxies, and that the stars may be very

different in mass and size. A more satisfactory computation should

be done starting from Eq. (52), with a reasonable guess for

![]() (may be

(may be

![]() ), and computing the rotation

curves with the right distribution of luminous matter and number

of stars. This is not a simple task and is postponed to future

work.

), and computing the rotation

curves with the right distribution of luminous matter and number

of stars. This is not a simple task and is postponed to future

work.

7 Concluding remarks

Starting from a reasonably simple f(R) model for gravity, we have shown that it is possible to obtain promising astrophysical results, which do not require dark matter. What is most important is the fact that, with the same model, it appears possible to do the same also at a cosmological level, where exact solutions have been discussed preliminarily in Capozziello et al. (2008). Of course, much work has still to be done on both scales. The work here is only indicative of the concrete possibility of testing a specific f(R) model of gravity on astrophysical grounds. For cosmology, at least the structure formation and the cosmological microwave background radiation spectrum must still be investigated. On local astrophysical scales, on the other hand, more realistic models for objects like galaxies, for example, are necessary.

References

- Allemandi, G., Borowiec, A., & Francaviglia, M. 2004, Phys. Rev. D, 70, 103503 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Bekenstein, J. 2004, Phys. Rev. D, 70, 083509 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Capozziello, S. 2002, Int. J. Mod. Phys. D, 11, 483 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Capozziello, S., & Francaviglia, M. 2008, GRG, 40, 357 (In the text)

- Capozziello, S., Carloni, S., & Troisi, A. 2003a, Rec. Res. Dev. Astron. Astroph., 1, 1, [arXiv:astro-ph/0303041] (In the text)

- Capozziello, S., Cardone, V. F., Carloni, S., & Troisi, A. 2003b, Int. J. Mod. Phys. D, 12, 1969 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Capozziello, S., Cardone, V. F., Carloni, S., & Troisi, A. 2004, Phys. Lett. A, 326, 292 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Capozziello, S., Cardone, V. F., & Troisi, A. 2005, Phys. Rev. D, 71, 043503 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Capozziello, S., Cardone, V. F., & Troisi, A. 2006, JCAP, 08, 001 [NASA ADS] (In the text)

- Capozziello, S., Cardone, V. F., & Troisi, A. 2007a, MNRAS, 375, 1423 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Capozzielo, S., Stabile, A., & Troisi, A. 2007b, Phys. Rev. D, 76, 104019 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Capozziello, S., Martin-Moruno, P., & Rubano, C. 2008, Phys. Lett. B, 664, 12 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Capozziello, S., De Filippis, E., & Salzano, V. 2009, MNRAS, 394, 947 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, S. M., Press, W. H., & Turner, E. L. 1992, ARA&A, 30, 499 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Carroll, S. M., Duvvuri, V., Trodden, M., & Turner, M. 2004, Phys. Rev. D, 70, 043528 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Cognola, G., & Zerbini, S. 2006, J. Phys. A, 39, 6245 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Cognola, G., Elizalde, E., Nojiri, S., Odintsov, S. D., & Zerbini, S. 2005, JCAP, 010 (In the text)

- Cognola, G., Gastaldi, M., & Zerbini, S. 2008, Int. J. Theor. Phys., 47, 898 [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Copeland, E. J., Sami, M., & Tsujikawa, S. 2006, Int. J. Mod. Phys. D, 15, 1753 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- de Ritis, R., Marmo, G., Platania, G., et al. 1990, Phys. Rev. D, 42, 1091 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Faraoni, V. 2005, Phys. Rev. D, 72, 124005 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Frigerio Martins, C., & Salucci, P. 2007, MNRAS, 381, 1103 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Hu, W., & Sawicki, I. 2007, Phys. Rev. D, 76, 064004 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Kleinert, H., & Schmidt, H.-J. 2002, GRG, 34, 1295 (In the text)

- Mendoza, S., & Rosas-Guevara, Y. M. 2007, A&A, 472, 367 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] (In the text)

- Milgrom, M. 1983, ApJ, 270, 365 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Mollerach, S., & Roulet, E. 2002, Gravitational lensing and microlensing (Singapore: World Scientific Publisher) (In the text)

- Nojiri, S., & Odintsov, S. D. 2004, GRG, 36, 1765 (In the text)

- Nojiri, S., & Odintsov, S. D. 2007, Phys. Lett. B, 652, 343 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Odintsov, S. D., & Nojiri, S. 2003, Phys. Lett. B, 576, 5 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Padmanabhan, T. 2003, Phys. Rep., 380, 235 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Peebles, P. J. E., & Rathra, B. 2003, Rev. Mod. Phys., 75, 559 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Petters, A. O., Levine, H., & Wambsganss, J. 2001, Singularity theory and gravitational lensing (Boston: Birkhauser) (In the text)

- Sanders, R. H., & McGough, S. S. 2002, ARA&A, 40, 263 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Schneider, P., Ehlers, J., & Falco, E. E. 1992, Gravitational lenses (Berlin: Springer-Verlag) (In the text)

- Sobouti, Y. 2007, A&A, 464, 921 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] (In the text)

- Starobinsky, A. A. 2007, JETP Lett., 86, 157 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Stelle, K. S. 1978, GRG, 9, 353 (In the text)

- Will, C. M. 2006, Living Rev. Relativity, 9, [arXiv:gr-qc/0510072] (In the text)

Footnotes

- ... namely

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- where

the combination of minus signs is only due to our conventions,

since we start from the metric (- + + +) and we obtain R < 0and

.

.

- ... vector

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- Here, quantities in boldface are vectors, while the versor will be denoted by an over-hat.

- ... plane

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- Both

and

and

are measured in angular units and could be redefined as

are measured in angular units and could be redefined as

and

and

with

with  and

and  in linear units.

in linear units.

- ...

way

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- Here, we limit ourselves to observing that, of course, the actual computation should be much more complicated, not only because of the fact that a galaxy is an extended object, but also because of the necessity to recompute the cosmological angular diameter distances.

All Figures

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{11992fig1}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/37/aa11992-09/Timg76.png) |

Figure 1:

Fit of Eq. (21) versus data in Sanders & McGough

(2002) as selected in Sobouti (2007). On the

x-axis, masses of luminous matter in units of

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{11992fig2}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/37/aa11992-09/Timg93.png) |

Figure 2:

Comparison between the values of the observed C0s for the planets of the Solar System and what is obtained

through Eq. (25). x-axis: the semi-major axes |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

Copyright ESO 2009

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.