| Issue |

A&A

Volume 505, Number 1, October I 2009

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Page(s) | 227 - 237 | |

| Section | Stellar structure and evolution | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/200911789 | |

| Published online | 16 July 2009 | |

Structure and spectra of irradiated secondaries in close binaries

A model calculation of the pre-cataclysmic variable UU Sagittae

A. C. Wawrzyn1,2 - T. S. Barman2 - H. M. Günther1 - P. H. Hauschildt1 - K. M. Exter3

1 - Hamburger Sternwarte, Gojenbergsweg 112, 21029 Hamburg, Germany

2 - Lowell Observatory, Hendricks Center for Planetary Studies, 1400 W. Mars Hill Rd., Flagstaff, AZ 86001, USA

3 - Instituut voor Sterrenkunde, Celestijnenlaan 200 D, 3001 Heverlee (Leuven), Belgium

Received 4 February 2009 / Accepted 24 June 2009

Abstract

Context. The standard stellar model atmosphere ignores the influence of external radiation. This assumption, while sufficient for most stars, fails for many short-period binaries.

Aims. In setting up combined model atmospheres for close binaries, we want to constrain the parameters of both components, especially in the case of a hot primary component strongly influencing its cool secondary companion. This situation can be found after common envelope evolution (CEE). The status of both components today allows one to retrace the CEE itself.

Methods. We used our stellar atmosphere code PHOENIX, which includes the effect of irradiation in its radiation transport equation, to investigate the close binary star UU Sge. We combined our calculated spectra of both components, weighted by their visible size, and adjusted the input parameters until reasonable agreement with observations is reached.

Results. We derive a range of

80 000-85 000 K for the effective temperature of the primary (

![]() )

and give a rough estimate for the primary's abundances, particularly the nitrogen enrichment. The heated day-side of the secondary has an apparent ``effective'' or equilibrium temperature of

24 000-26 000 K, nearly independent of its intrinsic luminosity. It shows an enhancement in nitrogen and carbon.

)

and give a rough estimate for the primary's abundances, particularly the nitrogen enrichment. The heated day-side of the secondary has an apparent ``effective'' or equilibrium temperature of

24 000-26 000 K, nearly independent of its intrinsic luminosity. It shows an enhancement in nitrogen and carbon.

Conclusions. The evolution of the primary and secondary stars were strongly influenced by the other's presence. Radiation from the primary on the secondary's day-side is still an important factor in understanding the secondary's atmospheric structure.

Key words: radiative transfer - stars: abundances - binaries: eclipsing - binaries: close - stars: atmospheres - stars: individual: UU Sge

1 Introduction

UU Sagittae (UU Sge) is the central nucleus of the old

planetary nebula (PN) Abell 63 (Abell 1966). This

nucleus is a total-eclipsing close binary that has passed

through the common-envelope phase and is currently a

pre-cataclysmic variable (pre-CV). The primary has been classified

as an O subdwarf (sdO) that has not yet contracted to a white

dwarf (WD) (Bond et al. 1978). The secondary companion is thought to be an unevolved

main-sequence star (MS) by its mass, probably a mid K- to mid

M-dwarf (dKV-dMV), but the luminosity of the night-side, due to

horizontal heat transfer beyond the terminator, is comparable

to that of a late A- to early

F-star (dAV-dFV). The PN is faint but still detectable, where a

typical PN lifetime before dispersion is about

![]() years

(de Kool & Ritter 1993; Iben & Tutukov 1993). The PN spectrum is unusual in that

the H Balmer series, O III (5007, 4959, and

4363 Å) and He I 5876 Å are the only strong

lines (Miller et al. 1976). It should hence not contaminate the

observed spectra of the nucleus. UU Sge's unique ``totally eclipsing''

nature allows one to determine well-constrained light-curve

solutions and, in combination with accurate radial velocity data,

the derivation of reliable geometrical parameters for the system. Even though

the geometry is well constrained, different quality measurements

and diverse physical implications have produced a variety

of mass and temperature estimates in the past, as discussed in

Sect. 2.

years

(de Kool & Ritter 1993; Iben & Tutukov 1993). The PN spectrum is unusual in that

the H Balmer series, O III (5007, 4959, and

4363 Å) and He I 5876 Å are the only strong

lines (Miller et al. 1976). It should hence not contaminate the

observed spectra of the nucleus. UU Sge's unique ``totally eclipsing''

nature allows one to determine well-constrained light-curve

solutions and, in combination with accurate radial velocity data,

the derivation of reliable geometrical parameters for the system. Even though

the geometry is well constrained, different quality measurements

and diverse physical implications have produced a variety

of mass and temperature estimates in the past, as discussed in

Sect. 2.

The reasonably well constrained geometry and observationally accessible nature of UU Sge makes this system a useful laboratory for studying the effects of irradiation in a close binary. The system's hot primary, the cooler secondary and the proximity of both components make the effects of irradiation an important feature. A crucial aspect of UU Sge is that none of the indications associated with mass transfer (e.g. accretion disk, bright spot, or boundary layer) are observed, which would otherwise make the irradiation geometry asymmetric and far more difficult to characterise.

Another important feature of UU Sge is that the primary

sdO is much larger than a fully evolved WD; the size

of the primary is almost comparable to that of the companion. Therefore the

estimated

![]() ratio of

ratio of ![]() 90 000 K: 6000 K

by Pollacco & Bell (1993, hereafter PB93) and

Bell et al. (1994, hereafter BPH94) leads directly

to a luminosity ratio of approximately 104 between the primary

and the (faint) night-side of the secondary close to the primary

eclipse.

90 000 K: 6000 K

by Pollacco & Bell (1993, hereafter PB93) and

Bell et al. (1994, hereafter BPH94) leads directly

to a luminosity ratio of approximately 104 between the primary

and the (faint) night-side of the secondary close to the primary

eclipse.

The geometry allows the fundamental parameters

of the primary, i.e.,

![]() ,

,

![]() and chemical composition, to be decoupled from the secondary, even

though they are not spatially resolved in the observation. The

primary near its eclipse can be dealt with in a first step,

neglecting the very small influence of the secondary

for the moment. The primary spectrum can then be

used to irradiate the secondary to model its day-side

in a second step, since reflection and heating effects from

the secondary on the primary should be negligible.

and chemical composition, to be decoupled from the secondary, even

though they are not spatially resolved in the observation. The

primary near its eclipse can be dealt with in a first step,

neglecting the very small influence of the secondary

for the moment. The primary spectrum can then be

used to irradiate the secondary to model its day-side

in a second step, since reflection and heating effects from

the secondary on the primary should be negligible.

The sum of primary and secondary spectrum must reproduce the emission near the secondary eclipse, where its heated day-side contributes significantly to the total flux; this defines the properties of the secondary.

In the following we do not concentrate on the common envelope evolution (CEE) (e.g. Taam & Sandquist 2000; Warner 1995; Iben & Livio 1993; Paczynski 1976; Livio 1996). This is the mechanism that is thought to expel the envelope of the Asymptotic Giant Branch (AGB) star (Rasio & Livio 1996; Sandquist et al. 1998) and due to this momentum loss produce close binaries; though the CEE surely has influenced what we observe in UU Sge today.

UU Sge has conserved its properties basically unaltered since the end of the CEE, because it is a pre-CV and no other major physical processes such as additional mass accretion has taken place yet. However, there are ongoing discussions upon this topic and alternative momentum loss mechanisms are suggested by e.g. Nelemans & Tout (2005); Webbink (2007); Beer et al. (2007); Taam & Ricker (2006).

For a review about detached binaries, physical processes in close binary systems, and general three-dimensional fluid dynamics in binary systems see Claret & Giménez (2001); Beer & Podsiadlowski (2002); Marsh (2000).

The paper is structured as follows: In Sect. 2 we summarise the properties of UU Sge and in Sect. 3 we present the observation that we model. Section 4 contains a short description of the stellar atmosphere code PHOENIX and the assumptions made for starting values. Section 5 presents the results for primary and secondary, followed by a discussion in Sect. 6. Section 7 concludes with a summary.

2 Properties of UU Sge

The first to suggest that UU Sge was an eclipsing binary was

Hoffleit (1932), who found it only twice at minimum on 25 plates. More than 30 years later UU Sge was listed as an

eclipsing binary in the PN catalogue of Abell (1966);

however, not until Bond (1976) found the PN Abell 63 and

the variable star UU Sge at the same position was the true nature of

the system established. Early predictions for the system

parameters were published by Budding & Kopal (1980),

Budding (1981), and Ritter (1986). Others followed

shortly after. Further improvements were made by 1993Pollacco who

measured the effective temperature (

![]() )

of the

primary to be 87 000 K and improved radial velocities that

indicated an oversized secondary (

)

of the

primary to be 87 000 K and improved radial velocities that

indicated an oversized secondary (![]() 2.0-2.5 times larger than

a corresponding zero-age MS star) leading to important changes to

the inferred geometry.

2.0-2.5 times larger than

a corresponding zero-age MS star) leading to important changes to

the inferred geometry.

One year later the secondary was, for the first time, observed directly during a total primary eclipse, which lasts some 14 min. The time between first and last contact with the primary is 1.26 h. This measurement provided an intrinsic temperature of 6250 K for the secondary's unilluminated night-side 1994Bell. There is an ongoing effort to constrain system parameters further (e.g. more recent work by Pustynski & Pustylnik 2005; Afsar & Ibanoglu 2008) since the uncertainties still do not allow the evolutionary status to be pinpointed.

Table 1: A selection of former derived values of UU Sge.

Table 1 shows a compilation of previously derived

parameters of UU Sge from Bond et al. (1978), de Kool & Ritter (1993),

Walton et al. (1993), 1993Pollacco/1994Bell,

Pustynski & Pustylnik (2005), Afsar & Ibanoglu (2008), and our results

for comparison.

We used Kepler's 3rd law to fill in

missing separations where possible. We use, like Pustynski & Pustylnik (2005), the

geometry derived by 1993Pollacco. Numbers in round brackets in the last

column are fixed input parameters and not derived by our model.

Values in squared brackets are only used outside the model

calculation. Note that we do not list a value of

![]() K by Shimansky et al. (2008),

which is discussed at a later point.

K by Shimansky et al. (2008),

which is discussed at a later point.

The parameters are (top to bottom) visual magnitude mV [mag],

distance to Earth d [pc], luminosity L [![]() ], mass m[

], mass m[![]() ], radius r [

], radius r [![]() ], logarithmic surface gravity

], logarithmic surface gravity

![]() [cm s-2], effective temperature

[cm s-2], effective temperature

![]() [K] for primary

[K] for primary

![]() and secondary

and secondary

![]() ,

equilibrium temperature

,

equilibrium temperature

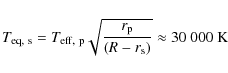

![]() [K] on day-side of secondary, separation R (centre to

centre) [

[K] on day-side of secondary, separation R (centre to

centre) [![]() ], mass ratio q of components, period P [h],

and system inclination i [

], mass ratio q of components, period P [h],

and system inclination i [![]() ], where

], where ![]() is edge

on. Note that many of these parameters are strongly coupled and,

even though most ratios are well determined, an error in, e.g.,

radial velocity does not only affect the separation but also the

radii and masses of the system and, consequently, other parameters

such as gravity, luminosity, and irradiation.

is edge

on. Note that many of these parameters are strongly coupled and,

even though most ratios are well determined, an error in, e.g.,

radial velocity does not only affect the separation but also the

radii and masses of the system and, consequently, other parameters

such as gravity, luminosity, and irradiation.

The effective temperatures of both components are especially

difficult to determine and a case can be made for higher as well

as lower temperatures, using e.g. the excitation of the PN or

missing opacities of other lines when using Balmer line ratios

(Exter et al. 2005, and references therein). If cooler temperature estimates

are correct, the primary may be a non-degenerate helium remnant of

a star of initial mass of about 5 ![]() (Iben & Tutukov 1989).

If instead hotter temperature estimates turn out to be true, the hot component

of UU Sge could be a star with a degenerate C O core and a

non-degenerate helium envelope which is burning helium at its base

(Iben & Tutukov 1993). According to Iben & Tutukov (1993) a luminosity

of

(Iben & Tutukov 1989).

If instead hotter temperature estimates turn out to be true, the hot component

of UU Sge could be a star with a degenerate C O core and a

non-degenerate helium envelope which is burning helium at its base

(Iben & Tutukov 1993). According to Iben & Tutukov (1993) a luminosity

of

![]() found by 1993Pollacco is likely too high, since it

exceeds the Eddington limit for a star of that predicted mass;

they suggest

found by 1993Pollacco is likely too high, since it

exceeds the Eddington limit for a star of that predicted mass;

they suggest

![]() .

.

3 Observations

Figure 1 shows two spectra (continuum normalised) of UU Sge obtained during phases close to primary and secondary eclipse along with the difference in flux. The wavelength coverage is 4185-4770 Å.

Data were taken with the spectrograph ISIS of the William Herschel Telescope and first published in 1993Pollacco, where details on the observations and data reduction procedures are given. Radial velocity shifts close to the eclipses are unimportant since the movement is perpendicular to line-of-sight. Stellar velocity shifts were corrected to the theoretical wavelengths.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{11789fg1.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/37/aa11789-09/Timg72.png) |

Figure 1: Observed spectrum 1993Pollacco close to the primary eclipse ( top), close to the secondary eclipse ( middle), and the difference spectrum ( bottom). |

| Open with DEXTER | |

We define phase

![]() (inferior conjunction) to coincide

with primary eclipse, where the larger secondary occults the

primary and orients its non-irradiated side to the observer. At

phase

(inferior conjunction) to coincide

with primary eclipse, where the larger secondary occults the

primary and orients its non-irradiated side to the observer. At

phase

![]() (superior conjunction) a secondary eclipse

occurs as the smaller primary transits the heated day-side of the

secondary. The observations were

taken close to but not exactly at

(superior conjunction) a secondary eclipse

occurs as the smaller primary transits the heated day-side of the

secondary. The observations were

taken close to but not exactly at

![]() and

and

![]() ,

so both components were visible during the exposures 1993Pollacco.

The first spectrum shows the primary and the cold

night-side of the secondary. The second spectrum also includes the

primary but this time with the hot day-side of the secondary. The

bottom panel in Fig. 1 displays the difference between

hot day-side and cold night-side of the secondary, since the

primary should roughly cancel out.

,

so both components were visible during the exposures 1993Pollacco.

The first spectrum shows the primary and the cold

night-side of the secondary. The second spectrum also includes the

primary but this time with the hot day-side of the secondary. The

bottom panel in Fig. 1 displays the difference between

hot day-side and cold night-side of the secondary, since the

primary should roughly cancel out.

Identified H I, He II, and N V absorption features are marked, where ``IS'' means the unknown diffuse interstellar band at 4430 Å that was not taken into account for the fitting of our model spectra.

Also indicated are where our synthetic spectra

predict lines.

In particular, we indicate the lines O IV

![]() ,

4555.8, 4633.2 Å, C IV

,

4555.8, 4633.2 Å, C IV

![]() ,

4647.9+4648.3 Å, Si IV

,

4647.9+4648.3 Å, Si IV

![]() (blend with O), 4655.6 Å and N V

(blend with O), 4655.6 Å and N V

![]() Å.

Å.

As is evident in the bottom panel of Fig. 1, only

two wavelength ranges are especially interesting with strong

``differential'' emission remaining from the secondary's day-side: a double

feature around 4340 Å, which results

from emission ``filling-in'' in the H![]() wings and a

multiple feature between 4630 and 4655 Å. These

are investigated in Sect. 5.2 in more detail.

wings and a

multiple feature between 4630 and 4655 Å. These

are investigated in Sect. 5.2 in more detail.

4 The model

4.1 The code

We use a modified version of the PHOENIX 15.04 stellar atmosphere

code (Hauschildt & Baron 1999) for the calculations presented

here. This is capable of modelling both the hot sdO

(Aufdenberg 2001) and the cooler MS companion

(Allard et al. 2001). The code includes an irradiation mode

(Barman et al. 2005,2004), which allows the

outer boundary conditions of the radiation transport equation to

include the incoming intensities from a primary star.

The primary spectrum is a full stellar spectrum, not a simple

black body. The most important lines,

namely H, He, C,

N, and O, are treated with full

non-local thermodynamic equilibrium (NLTE) during the

calculations. Other species, e.g. Fe and

Mg, were reset to LTE to save computation time

once we tested their influence on the model.

The model considers the distance between both stellar components,

their radii, and the angle between incident flux and surface normal.

The parameters were fixed to the set of 1993Pollacco/1994Bell.

We use our spherical symmetric radiation transport (SSRT) mode for the

secondary, whose atmosphere is divided into 64 concentric

shells and

![]() is set to 5000 Å.

is set to 5000 Å.

To obtain the spectrum of the secondary two simulations are independently carried out: the irradiated day-side; and the night-side, which resembles a MS star. The day-side is assumed to re-radiate all the incident flux, so we use a geometric scaling factor of 0.5. The lateral energy transport between the day- and night-side of the secondary is assumed to be negligible. The irradiation heats and expands the photosphere of the day-side, so we assume in our model that thermodynamic variables like entropy and gas pressure are discontinuous at the boundary between day-side and night-side for a given stellar radius. Consequently, small scale turbulence will develop in a boundary layer, which is not included in our model.

4.2 Setup

For all currently derived radii and distances between the components the secondary still underfills its Roche lobe by about 30% (see e.g. Eggleton 1983; Pringle & Wade 1985), i.e., there is no mass transfer to the primary. The secondary should hence be reasonably well approximated by a sphere, which justifies the use of our SSRT mode.The primary most likely lost a large fraction of its H and He envelope during its CEE, while the secondary accreted additional material during that state. Since hotter post-early-AGB stars tend to be sdOs with a normal H/ He ratio (Moehler et al. 1998) we use the solar standard composition for the initial condition.

The metallicity Z of both components is based on the solar photospheric abundances by Asplund et al. (2005). Further variations will be dealt with during the model fit (Sects. 5.1 and 5.2).

The temperature of sdOs ranges from

![]() to 100 000 K and the surface gravity from

to 100 000 K and the surface gravity from

![]() to 6.5 (Dreizler & Murdin 2000).

Since UU Sge seems to be a rather young sdO it should tend to

higher

to 6.5 (Dreizler & Murdin 2000).

Since UU Sge seems to be a rather young sdO it should tend to

higher

![]() and lower

and lower

![]() ,

i.e., it has neither cooled nor contracted much yet. For the

companion it is reasonable to assume an ordinary MS star with

,

i.e., it has neither cooled nor contracted much yet. For the

companion it is reasonable to assume an ordinary MS star with

![]() K and

K and

![]() ,

where the last value results from the inferred mass

and radius of the secondary by 1994Bell. However, it is heated to

higher temperatures on the day-side, where a horizontal heat

flux towards the night-side probably also effectively doubles the

temperature (1994Bell measure temperatures of the order 6000 K on

the night-side). We take the above values as an initial guess.

,

where the last value results from the inferred mass

and radius of the secondary by 1994Bell. However, it is heated to

higher temperatures on the day-side, where a horizontal heat

flux towards the night-side probably also effectively doubles the

temperature (1994Bell measure temperatures of the order 6000 K on

the night-side). We take the above values as an initial guess.

Fundamental parameters of the primary were explored by

calculating a grid

of effective temperatures (

![]() ),

surface gravities (

),

surface gravities (

![]() ), and metallicities

(

), and metallicities

(

![]() ). The fitting was then done by

comparing five selected strong features to the observation close

to the primary eclipse.

We identified residuals and adapted the parameters accordingly,

to improve the fit iteratively.

). The fitting was then done by

comparing five selected strong features to the observation close

to the primary eclipse.

We identified residuals and adapted the parameters accordingly,

to improve the fit iteratively.

The secondary is assumed to be an ordinary MS star and is then

irradiated by primary spectra of different temperatures. The

influence of varying

![]() of both components and

abundances is investigated.

of both components and

abundances is investigated.

Finally, we note that we do not include a wind or chromosphere in the model calculations.

5 Results

5.1 The primary

We fit the primary model to the observation at

![]() ,

i.e., close to primary eclipse, where the flux of

the secondary's

night-side is negligible and virtually all flux originates from the

primary.

,

i.e., close to primary eclipse, where the flux of

the secondary's

night-side is negligible and virtually all flux originates from the

primary.

The lines are rotationally broadened.

Velocities were first calculated assuming a tidally locked and

circular orbit, with

![]() km s-1 for the primary, which, however, requires

a

km s-1 for the primary, which, however, requires

a

![]() km s-1 depending on the

major feature probed. This value is high but

still well below the breakup velocity of

km s-1 depending on the

major feature probed. This value is high but

still well below the breakup velocity of

![]() km s-1.

Note that a velocity field, due to the mass loss caused by

a strong wind, might cause macro turbulence in the line forming

regions that mimics rotational broadening to some extend.

km s-1.

Note that a velocity field, due to the mass loss caused by

a strong wind, might cause macro turbulence in the line forming

regions that mimics rotational broadening to some extend.

For the primary this comparison shows that the N V absorption

features agree well with the observations for

![]() and

and

![]() K. This is right between

the limb darkening solution (57 000 K) and the limb brightening

solution (87 000 K) of 1994Bell. Grid points with higher

K. This is right between

the limb darkening solution (57 000 K) and the limb brightening

solution (87 000 K) of 1994Bell. Grid points with higher

![]() ,

closer to the light curve analysis of

Pustynski & Pustylnik (2005) and compatible with 1993Pollacco, require an

increase of the N abundance

,

closer to the light curve analysis of

Pustynski & Pustylnik (2005) and compatible with 1993Pollacco, require an

increase of the N abundance

![]() by +1.5 dex and

more. N is normally increased by less than one order of

magnitude in AGB evolution (van Winckel 2003).

Also emission of C IV from the secondary's day-side suggests that the

primary is not much hotter than 85 000 K or further away from

the secondary than the assumed 2.46

by +1.5 dex and

more. N is normally increased by less than one order of

magnitude in AGB evolution (van Winckel 2003).

Also emission of C IV from the secondary's day-side suggests that the

primary is not much hotter than 85 000 K or further away from

the secondary than the assumed 2.46 ![]() separation (see

Sect. 5.2). Note, that our model of the secondary's

day-side represents the spectrum of the substellar point only and

the constraint on the primary temperature could be less severe

if the secondary's day-side is a ``patchwork'' of different temperature.

separation (see

Sect. 5.2). Note, that our model of the secondary's

day-side represents the spectrum of the substellar point only and

the constraint on the primary temperature could be less severe

if the secondary's day-side is a ``patchwork'' of different temperature.

Table 2: Primary abundances with respect to solar values*.

The intensities of the N V

![]() ,

4619 Å

absorption lines in comparison to the C IV

,

4619 Å

absorption lines in comparison to the C IV

![]() Å and the O IV

Å and the O IV

![]() Å lines suggest

that N is overabundant and C and

O are

underabundant in the atmosphere of the primary. Si is only a minor species

and not handled in NLTE. Our best-fit abundances for a model with

Å lines suggest

that N is overabundant and C and

O are

underabundant in the atmosphere of the primary. Si is only a minor species

and not handled in NLTE. Our best-fit abundances for a model with

![]() K are listed in Table 2.

K are listed in Table 2.

The general abundance pattern is best described by

![]() ,

however, our model only

derives the ratios of these elemental abundances, so

selecting a specific

,

however, our model only

derives the ratios of these elemental abundances, so

selecting a specific

![]() is somewhat

arbitrary. For all our models the N

abundance is enormous, while C

and O seem to be slightly depleted.

Si

only requires depletion for a base metallicity of

+0.5 dex.

is somewhat

arbitrary. For all our models the N

abundance is enormous, while C

and O seem to be slightly depleted.

Si

only requires depletion for a base metallicity of

+0.5 dex.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{11789fg2.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/37/aa11789-09/Timg103.png) |

Figure 2:

A synthetic spectrum for the primary with

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

Figure 2 shows a comparison between the best

fit primary synthetic spectrum with

![]() ,

,

![]() and

abundances from Table 2, and the

observation close to phase

and

abundances from Table 2, and the

observation close to phase

![]() .

The night-side

spectrum of the secondary was not calculated at this point and

hence not added to the synthetic spectrum of the primary.

Displayed are solely the features of the primary.

.

The night-side

spectrum of the secondary was not calculated at this point and

hence not added to the synthetic spectrum of the primary.

Displayed are solely the features of the primary.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{11789fg3.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/37/aa11789-09/Timg106.png) |

Figure 3: |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Figure 3 also shows a comparison between

observation and synthetic spectrum, but for a model

with

![]() ,

,

![]() and the abundances of

Table 2. The quality of the fit

is similar to the previous model but requires a higher

and the abundances of

Table 2. The quality of the fit

is similar to the previous model but requires a higher

![]() and produces stronger unobserved N lines.

and produces stronger unobserved N lines.

The He II absorption feature at

4686 Å is systematically too strong in our synthetic spectra. This feature is

characteristic for most sdOs. In our model it depends only weakly on

the He abundance or temperature.

Contrary to the other He lines it

increases in depth for higher ![]() values. It is not blended with

other lines.

values. It is not blended with

other lines.

Using the mass and radius from 1993Pollacco

![]() of

the primary is constrained to

5.2. However, the

of

the primary is constrained to

5.2. However, the

![]() He line fits the

observation best for

He line fits the

observation best for

![]() ,

as can be seen in

Fig. 4. This fit also requires a He

depletion of -0.5 dex to match the other two He lines.

All important He II absorption features of the primary within

the observed spectral range are dealt with using special Stark line profiles

(Hubeny & Lanz 2000), so the effect of

,

as can be seen in

Fig. 4. This fit also requires a He

depletion of -0.5 dex to match the other two He lines.

All important He II absorption features of the primary within

the observed spectral range are dealt with using special Stark line profiles

(Hubeny & Lanz 2000), so the effect of ![]() should

be real, suggesting a much lower

should

be real, suggesting a much lower

![]() than given by 1993Pollacco.

Note, that adding the day-side spectrum of the secondary contributes

some emission that reduces the problem, while the night-side

spectrum influence can be neglected as expected.

than given by 1993Pollacco.

Note, that adding the day-side spectrum of the secondary contributes

some emission that reduces the problem, while the night-side

spectrum influence can be neglected as expected.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{11789fg4.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/37/aa11789-09/Timg107.png) |

Figure 4: |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{11789fg5.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/37/aa11789-09/Timg108.png) |

Figure 5:

Variation in lines due to increase of

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=17.5cm,clip]{11789fg6.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/37/aa11789-09/Timg109.png) |

Figure 6:

Combined theoretical spectrum of the best-fit primary and

the initial secondary day-side model, using the primary model

(85 000 K, increased abundance from Table 2

by another

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=17.5cm,clip]{11789fg7.ps} \end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/37/aa11789-09/Timg112.png) |

Figure 7:

Combined theoretical best-fit primary (for each

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

|

(1) |

where we used

5.2 The secondary

We fit the day-side of the secondary component to the

difference spectrum

of phase

![]() minus

minus

![]() ,

i.e.,

subtract the primary's influence on the total spectrum. Since

there are not many emission lines left, we test the overall

influence and then focus on the ``broad emission

feature'' at

4635-4655 Å. This feature is uniquely

sensitive to the abundances used.

,

i.e.,

subtract the primary's influence on the total spectrum. Since

there are not many emission lines left, we test the overall

influence and then focus on the ``broad emission

feature'' at

4635-4655 Å. This feature is uniquely

sensitive to the abundances used.

All absorption lines are Doppler-shifted in anti-phase with the emission features, which shows that the first originate from the primary while the others are due to irradiation on the hot side of the secondary. This is confirmed by the phase dependence of the emission lines, which are strongest at phases close to 0.5 and not visible at all near phase 0.0.

In Fig. 6 the combined best-fit primary and

initial secondary spectrum is shown. The observed extra emission

``filling-in'' the wings of H is too weak

(top panel) to explain the differences

seen in the bottom panel of Fig. 1. There

are other small emission lines in the synthetic spectrum which

cannot be found in the observation.

In the bottom panel of Fig. 6 the broad emission

feature at

4635-4655 Å is not reproduced

well by solar abundance in the secondary model, since important C III and N III lines are too

weak (see Fig. 7 for details). Also

emissions lines such as N II

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

O II

,

O II

![]() ,

and C II

,

and C II

![]() ,

,

![]() originating from the secondary start to balance the primary N V

absorptions significantly more than observed.

originating from the secondary start to balance the primary N V

absorptions significantly more than observed.

These all indicate that the heating effect on the secondary is

higher than first estimated and that the abundances of

C, N, and probably O

need to be increased. We used Z=+0.5 dex and varied

![]() to match the broad emission feature.

to match the broad emission feature.

Figure 7 shows a magnification of the

wavelength range

4635-4655 Å of a combined primary plus

secondary spectrum (weighted for sizes) and the effect of applying

broadening mechanisms. The broadening is clearly

dominated by rotation. Velocities were again calculated assuming a

tidally locked and circular orbit with

![]() km s-1 for the secondary. The synthetic spectra match

the observation quite well, so no additional rotational broadening

is required.

km s-1 for the secondary. The synthetic spectra match

the observation quite well, so no additional rotational broadening

is required.

To explain the emission lines of C III at

![]() and 4651 to 4653 Å the C abundance in

the secondary needs to be set to

and 4651 to 4653 Å the C abundance in

the secondary needs to be set to

![]() dex

solar in NLTE and even more in LTE. This seems unreasonable

considering that the primary is C depleted during

the CEE phase. It is also not compatible with observations outside

the

4635-4655 Å broad emission feature, where synthetic

spectra with C abundances that high predict unobserved

emission lines.

dex

solar in NLTE and even more in LTE. This seems unreasonable

considering that the primary is C depleted during

the CEE phase. It is also not compatible with observations outside

the

4635-4655 Å broad emission feature, where synthetic

spectra with C abundances that high predict unobserved

emission lines.

The N abundance is not high enough to reproduce

the size of the middle broad emission feature; this indicates that a higher

![]() is needed and that some N was

accreted during the CEE, enriching the secondary's surface by

approximately +1 dex.

This is reasonable, since, in contrast to C, the

primary is greatly enriched in N in its photosphere.

is needed and that some N was

accreted during the CEE, enriching the secondary's surface by

approximately +1 dex.

This is reasonable, since, in contrast to C, the

primary is greatly enriched in N in its photosphere.

The abundance of O on the secondary is difficult to constrain, since the only emission line is flanked by stronger C lines (see Fig. 7). We use +1 dex for the models shown. From evolutionary considerations it need not be enriched.

The instrumental resolution is not high enough to

resolve single lines from the broad emission feature originating from the

secondary in Fig. 7. It might be feasible,

however, to analyse the shape if one knows what lines are expected

within the broad feature. In case of the double peak in the third

broad emission feature, it seems that C IV fits the

observation of the secondary's induced emission best

for a 85 000 K primary, while for the 75 000 K

and 95 000 K model the

shape is off-balance on the left. The last model hence suggests

less heating or a larger separation. In contrast, there are

N II and C II emission lines from the secondary

day-side at the same wavelength as the N V absorption

(

![]() Å)

by the primary that add up to a worse overall fit. Increased

heating results in more N III and C III, but the

higher continuum changes the shape and hence does not reduce

this problem. Combining these two considerations results

in a

Å)

by the primary that add up to a worse overall fit. Increased

heating results in more N III and C III, but the

higher continuum changes the shape and hence does not reduce

this problem. Combining these two considerations results

in a

![]() value of

80 000-85 000 K,

comparable to the light curve analysis of Pustynski & Pustylnik (2005); Afsar & Ibanoglu (2008)

and the revised value of 1994Bell.

value of

80 000-85 000 K,

comparable to the light curve analysis of Pustynski & Pustylnik (2005); Afsar & Ibanoglu (2008)

and the revised value of 1994Bell.

Table 3:

![]() and model

predicted

and model

predicted

![]() .

.

Table 3 lists the model prediction for

![]() on the day-side of the secondary depending

on

on the day-side of the secondary depending

on

![]() for a separation of

for a separation of

![]() and

and

![]() K. Results vary on the order of

50-100 K for 1 dex abundance changes.

K. Results vary on the order of

50-100 K for 1 dex abundance changes.

The typical temperature of the medium where the observed emission

lines of heavy elements are formed is

21 000-26 000 K.

1993Pollacco gives

![]() K for the heated day-side of the

secondary of

UU Sge, which would be consistent with a primary temperature of

78 000-85 000 K in our case and supports our own

K for the heated day-side of the

secondary of

UU Sge, which would be consistent with a primary temperature of

78 000-85 000 K in our case and supports our own

![]() considerations above.

considerations above.

In this case the irradiation of the primary dominates the atmosphere

of the secondary completely deeper than optical depth, ![]() .

The variation in

.

The variation in

![]() for changing

for changing

![]() ,

while

,

while

![]() K

and

K

and

![]() are kept constant, is negligible.

Comparing

are kept constant, is negligible.

Comparing

![]() for a model with

for a model with

![]() K and one with

K and one with

![]() K results in a mere change of 20-30 K.

K results in a mere change of 20-30 K.

An interesting effect that was already observed by Brett & Smith (1993) in irradiated models (10 000 K blackbody primary) is that the optical depth at a given geometrical depth increases with increasing irradiative flux, i.e., the radiation makes the surface layers more opaque. We see a similar effect for primary temperatures up to roughly 85 000 K, at even higher temperatures the opposite occurs and the surface layers of the secondary start to become less opaque again, because some species become fully ionised.

The high difference between primary and secondary night-side flux contribution

to the observed spectrum that allows one the decoupling of the primary from the

secondary parameters in the first step of this analysis prevents

a proper

![]() estimate for the night-side of the secondary being made. At phase

estimate for the night-side of the secondary being made. At phase

![]() the spectrum is dominated by the primary

and the night-side of the secondary cannot be fitted.

The heat flux beyond the terminator in convective layers should

adjust to a static solution if it is supposed to be the same star.

An attempt to match the structure, i.e., the entropy

per free particle, of the irradiated model day-side with hotter

models of the undisturbed night-side was unsuccessful. The radiation field

of the primary dominates the temperature structure of the day-side

of the secondary deep into the photosphere, the convection zone is

therefore pressed down into deeper layers and no common adiabat

was found.

the spectrum is dominated by the primary

and the night-side of the secondary cannot be fitted.

The heat flux beyond the terminator in convective layers should

adjust to a static solution if it is supposed to be the same star.

An attempt to match the structure, i.e., the entropy

per free particle, of the irradiated model day-side with hotter

models of the undisturbed night-side was unsuccessful. The radiation field

of the primary dominates the temperature structure of the day-side

of the secondary deep into the photosphere, the convection zone is

therefore pressed down into deeper layers and no common adiabat

was found.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{11789fg8.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/37/aa11789-09/Timg134.png) |

Figure 8:

The structure of the temperature and

radiation field in the irradiated atmosphere at the substellar

point. The small kink at

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

For each layer radiation is generated going in- and outwards. The

radiation going inwards is reflected at the inner boundary condition

and thus cancels out in the derivation of

![]() ,

whereas the radiation going outwards is summed up and therefore

,

whereas the radiation going outwards is summed up and therefore

![]() increases monotonically outwards by more than

three orders of magnitude. The energy lost exceeds the

energy delivered from the inner boundary by far and the

photosphere would cool down without an external energy source.

increases monotonically outwards by more than

three orders of magnitude. The energy lost exceeds the

energy delivered from the inner boundary by far and the

photosphere would cool down without an external energy source.

The lower panel in Fig. 8 shows the external radiation

flux

![]() .

To obtain a measure of the influence of

the external radiation field a full model including the internal

flux and the irradiation is calculated. The difference between

the radiation field obtained in this case and the internal radiation

flux (

.

To obtain a measure of the influence of

the external radiation field a full model including the internal

flux and the irradiation is calculated. The difference between

the radiation field obtained in this case and the internal radiation

flux (

![]() )

is

)

is

![]() .

This characterises the layers where the

incident radiation is reprocessed in the atmosphere.

.

This characterises the layers where the

incident radiation is reprocessed in the atmosphere.

![]() is negative, because it is directed inwards.

is negative, because it is directed inwards.

The plot does not contain reflected external irradiation, since

this cancels out in the net

flux

![]() .

In the thin outer layers of the atmosphere

the optical depth is low, so only little flux is absorbed.

Around a gas pressure of 103 dyn cm-2, much of the external

flux is absorbed, causing a temperature inversion, so deeper layers

are cooler again. Between 103 dyn cm-2 and

.

In the thin outer layers of the atmosphere

the optical depth is low, so only little flux is absorbed.

Around a gas pressure of 103 dyn cm-2, much of the external

flux is absorbed, causing a temperature inversion, so deeper layers

are cooler again. Between 103 dyn cm-2 and

![]() dyn cm-2 the external radiation flux deceases to

1/e of the initial value, thus this can be taken as the depth to

where the external radiation penetrates.

dyn cm-2 the external radiation flux deceases to

1/e of the initial value, thus this can be taken as the depth to

where the external radiation penetrates.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{11789fg9.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/37/aa11789-09/Timg137.png) |

Figure 9: The relative abundances of the most prominent ionisation stages for C, N and O. For comparison purposes the lower panel contains the temperature structure. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

The ionisation in the outer layers is not collisionally dominated but the ionisation structure is given by the external radiation field, leading to an ``over-ionisation''. Figure 9 shows the dominant stages of ionisation for the ions of C, N, and O. Although the temperature is only 25 000 K at 10-2 dyn cm-2, higher stages of ionisation (C IV, N III and O III) prevail compared to the inner, denser layers at the same temperature, but the column mass of these elements is so small that they do not contribute any significant emission lines. Most of the spectral features above originate around 103 dyn cm-2, where most of the incident energy is reprocessed. In this region C II and C III, N II, N III, and O II are most dominant. At deeper layers these ions recombine to neutral atoms, but the density and therefore the optical depth also increases, so that no line emission from atoms is observed. If the primary is either closer or hotter than expected than the stronger irradiation would lead to higher stages of ionisation in the crucial region around 103 dyn cm-2 and cause more emission lines which are not observed, e.g. O VI.

6 Discussion

In our model the secondary is

tidally locked in a circular orbit, hence is rotating

synchronously, because its calculated

![]() fits the observation and primary and secondary

eclipses are equidistant in the light curve of 1993Pollacco.

The primary cannot be tidally locked, since additional broadening

requires a speed-up by

a factor of approximately 4-5, which is still a reasonable

rotational velocity for a subdwarf with radiative envelope that

was spun up by its own contraction.

fits the observation and primary and secondary

eclipses are equidistant in the light curve of 1993Pollacco.

The primary cannot be tidally locked, since additional broadening

requires a speed-up by

a factor of approximately 4-5, which is still a reasonable

rotational velocity for a subdwarf with radiative envelope that

was spun up by its own contraction.

Remember that we have not included a wind in the model and that a turbulence on the surface can explain the additional broadening at least in parts.

We assume a circular

orbit for simplicity, even though it is worth noting that within

the framework of Zahn's theory, the synchronisation timescales are

several orders of magnitude smaller than the circularisation

timescales (Toledano et al. 2007). This ensures a uniform

irradiation at a constant distance on the same side of the

secondary, which itself is convective at least in layers

the irradiation cannot penetrate. Also

worth noting is that Zahn (1977,1989) found the

characteristic timescale for synchronisation as a function of a,

the major semi-axis of the orbit, to be

![]() for

stars with convective envelopes and

for

stars with convective envelopes and

![]() for

stars with with radiative envelopes, which might explain why the

smaller, more compact and still contracting primary has not yet

reacted to synchronisation.

for

stars with with radiative envelopes, which might explain why the

smaller, more compact and still contracting primary has not yet

reacted to synchronisation.

An alternative mechanism has been proposed by Tassoul & Tassoul (1992) where the spin down time for a given system depends only on the radius as R-4.125. Again the larger secondary synchronises faster.

6.1 Primary component

Without any limb darkening or brightening effects included

![]() K is in between the results

of 1993Pollacco/1994Bell for the primary. It is in agreement with their error

bars, given a fixed separation of

K is in between the results

of 1993Pollacco/1994Bell for the primary. It is in agreement with their error

bars, given a fixed separation of

![]() .

We, however,

favour a higher value of

80 000-85 000 K, due to the

effects on the broad emission feature on the secondary (see

Fig. 7), even though this requires an

enrichment of approximately +1.5 dex in N on the

primary surface.

This result resembles the light-curve solution by

Pustynski & Pustylnik (2005) and the new values by Afsar & Ibanoglu (2008).

.

We, however,

favour a higher value of

80 000-85 000 K, due to the

effects on the broad emission feature on the secondary (see

Fig. 7), even though this requires an

enrichment of approximately +1.5 dex in N on the

primary surface.

This result resembles the light-curve solution by

Pustynski & Pustylnik (2005) and the new values by Afsar & Ibanoglu (2008).

In general, He rich sdO stars are also enriched

in some metals, especially C and N.

This clearly indicates that the surface contains material burned

in the C N O cycle as well

as products of helium burning (Dreizler & Murdin 2000). Within these

nuclear burning processes C is turned into N by proton

capture, probably benefited by some effect that mixes protons into

deeper layers. Thus the abundance of C falls while the

abundance of N increases

( 12C(p,![]() )

13N(e+,

)

13N(e+,![]() )

13C(p,

)

13C(p,![]() )

14N).

He is turned into C via the triple alpha (

)

14N).

He is turned into C via the triple alpha (![]() )

reaction, but C is destroyed in the outer parts of

He-burning shells

by the reaction

12C(

)

reaction, but C is destroyed in the outer parts of

He-burning shells

by the reaction

12C(![]() ,

,![]() )

16O. Hence

C is depleted more than N is enriched. The sdO of

UU Sge is decreased in He and especially enriched in

N and depleted in C and O.

This can be understood as stripping the outer envelope

layers down to a layer which was enriched in N

during the CEE; the H-rich and He-rich

layers, where the 3

)

16O. Hence

C is depleted more than N is enriched. The sdO of

UU Sge is decreased in He and especially enriched in

N and depleted in C and O.

This can be understood as stripping the outer envelope

layers down to a layer which was enriched in N

during the CEE; the H-rich and He-rich

layers, where the 3![]() process which produces

C is most efficient, have been removed.

process which produces

C is most efficient, have been removed.

The production of 14N at the cost of C and O in the C N O cycle (de Greve & Cugier 1989) is not unusual in the evolution of AGB stars during their third dredge up phase (see Herwig (2005) for a review). Enriched N and depleted C is also observed in WD+MS binaries as supernovae (SN) Ia progenitors (Langer et al. 2000). The depletion of He is most likely due to the CEE, i.e., the stripping of the outer layers.

Note that He is slightly underabundant in UU Sge

for all our models.

If a high

![]() is prescribed for the model then the

He abundance is fitted closer to solar values.

is prescribed for the model then the

He abundance is fitted closer to solar values.

N V

![]() is in emission for

NLTE models with

is in emission for

NLTE models with

![]() K.

There are no known sdOs with such high temperatures (S. Dreizler,

private communication). There is, however, PG1144+005

(

K.

There are no known sdOs with such high temperatures (S. Dreizler,

private communication). There is, however, PG1144+005

(

![]() K and

K and

![]() ), which is a

peculiar PG1159-like star that shows such N V emission

lines at

), which is a

peculiar PG1159-like star that shows such N V emission

lines at

![]() and 4619 Å (Werner & Heber 1991).

Therefore this NLTE effect seems reasonable and suggests a lower

and 4619 Å (Werner & Heber 1991).

Therefore this NLTE effect seems reasonable and suggests a lower

![]() than 100 000 K, probably even lower than

90 000-95 000 K; therefore our model is contradicting the

primary temperature of 120 000 K found by Shimansky et al. (2008).

than 100 000 K, probably even lower than

90 000-95 000 K; therefore our model is contradicting the

primary temperature of 120 000 K found by Shimansky et al. (2008).

There is a problem with the surface gravity derived from He II

![]() Å which suggests a

Å which suggests a

![]() ,

and we require a He depletion

of -0.5 dex to fit all other He II absorption lines.

Using the mass and radius from 1993Pollacco

,

and we require a He depletion

of -0.5 dex to fit all other He II absorption lines.

Using the mass and radius from 1993Pollacco

![]() of

the primary is constrained to

of

the primary is constrained to

![]() as mentioned before.

Probably this is due to numerically instabilities in the treatment

of the radiation pressure in the model,

since it seems unlikely that the primary is much less massive or

has a veil of reaccreted He within its Roche lobe

that has not fallen back on the surface yet. At phase 0.5 this

problem is solved by adding emissions from the day-side of the

secondary and consistent with a

as mentioned before.

Probably this is due to numerically instabilities in the treatment

of the radiation pressure in the model,

since it seems unlikely that the primary is much less massive or

has a veil of reaccreted He within its Roche lobe

that has not fallen back on the surface yet. At phase 0.5 this

problem is solved by adding emissions from the day-side of the

secondary and consistent with a

![]() to

5.2. However, at phase 0.0 the night-side, even if set to

to

5.2. However, at phase 0.0 the night-side, even if set to

![]() K (e.g. as would be due to a

horizontal heat flux

beyond the terminator), is too weak for the same correction. It

is unclear whether the primary is really less compact than

expected, or why otherwise this particular He II feature is weaker

than expected, since there is no indication of any emission (e.g.

by material within the secondary Roche lobe through which

radiation is transmitted).

K (e.g. as would be due to a

horizontal heat flux

beyond the terminator), is too weak for the same correction. It

is unclear whether the primary is really less compact than

expected, or why otherwise this particular He II feature is weaker

than expected, since there is no indication of any emission (e.g.

by material within the secondary Roche lobe through which

radiation is transmitted).

While main sequence O stars are known to exhibit a stellar wind, the atmospheres of most sdO stars can be regarded as hydrostatic. Of course, signatures of a stellar wind can be detected in the most luminous sdOs through P-Cygni profiles in UV resonance lines or through emission lines in the visible, but even in these stars all other lines originate from quasi-static layers of the atmosphere (Dreizler & Murdin 2000).

According to radiation driven wind theory (Pauldrach et al. 1988)

a star like UU Sge, which is close to the Eddington limit, should

have a mass loss rate of

![]() yr-1 and

a terminal velocity of 2000 km s-1. PB93 find, however, no

P Cygni profiles in resonance lines of IUE data. This implies that

the wind velocity is <1000 km s-1. PB93 also inferred a

stellar wind mass loss rate of <

yr-1 and

a terminal velocity of 2000 km s-1. PB93 find, however, no

P Cygni profiles in resonance lines of IUE data. This implies that

the wind velocity is <1000 km s-1. PB93 also inferred a

stellar wind mass loss rate of <

![]() yr-1by using the error in the period determination as an upper limit

over nearly 12 000 orbital circles.

yr-1by using the error in the period determination as an upper limit

over nearly 12 000 orbital circles.

We do not include limb darkening in our models, since 1993Pollacco find no limb darkening for primary temperatures in excess of 85 000 K, analysing the light curve around the ingress and egress from the primary minimum.

6.2 Secondary component

Webbink (1988) claimed, inferred from observations of the binary core of

planetary nebulae, that the unevolved secondary star has been

little disturbed by the CEE and resembles a normal main-sequence star.

The night-side temperature of the

secondary component, measured by 1994Bell, however, would normally

indicate a spectral type of late A / early F and consequently a

mass around ![]()

![]() and a radius around

and a radius around ![]()

![]() ,

assuming it is on the main sequence. Hence the

derived mass of

,

assuming it is on the main sequence. Hence the

derived mass of

![]() and radius of

and radius of

![]() imply that the evolutionary path of this object has been greatly

influenced by the sdO star. This mass estimate indicates an M-type

dwarf.

imply that the evolutionary path of this object has been greatly

influenced by the sdO star. This mass estimate indicates an M-type

dwarf.

It is conceivable that this star has been stripped of its outer layers during the CEE and accreted some other material.

Due to the amount of material accreted and the short time

since the CEE phase, the secondary may still be out of thermal

equilibrium.

The thermal relaxation time-scale of the disturbed outer layers of

the secondary, once the common envelope is ejected, is

![]() 104 years, comparable to the estimated age of the PN.

This could explain why the secondary is

oversized for its mass (1993Pollacco; Afsar & Ibanoglu 2008) and

could mean that the internal structure of the

secondary is inhomogeneous, i.e., the accreted material has not

mixed in (Sarna & Ziolkowski 1988; Prialnik & Livio 1985). Probably the heating

on the day-side of the secondary also contributes to the

inflation of the star.

104 years, comparable to the estimated age of the PN.

This could explain why the secondary is

oversized for its mass (1993Pollacco; Afsar & Ibanoglu 2008) and

could mean that the internal structure of the

secondary is inhomogeneous, i.e., the accreted material has not

mixed in (Sarna & Ziolkowski 1988; Prialnik & Livio 1985). Probably the heating

on the day-side of the secondary also contributes to the

inflation of the star.

Using the wind mass loss rate by 1993Pollacco no

more than

![]() have been ejected by the primary

during the PN lifetime. This is orders of magnitude below the required

N mass needed to explain the abundances in the

secondary, even for a pure N wind that is completely accreted.

have been ejected by the primary

during the PN lifetime. This is orders of magnitude below the required

N mass needed to explain the abundances in the

secondary, even for a pure N wind that is completely accreted.

Since the secondary is less massive than the primary (the mass ratio q<1.0) the system has been detached since the end of the CEE and will be, until gravitational wave radiation and magnetic stellar wind braking brings the secondary in contact with its Roche lobe again (Sarna et al. 1996). The secondary may resemble the composition of the primary.

According to Marks & Sarna (1998) the effect of accretion during

CEE on the abundances is expected to be very small, the only significant

difference being seen in the abundance of N, which is

increased by less than one order of magnitude. The secondary of

UU Sge, however, displays an enrichment of not only N but also C and probably

O in its photosphere compared to

![]() .

It

is oversized

compared to a zero-age MS star of the same mass 1994Bell.

This might be understood as a layer of material accreted from the

primary, possibly related to the last layer stripped there.

Probably C and N were transferred to the

secondary while C was still being transformed to N

in the primary. Accreted material may still settle down to

deeper layers in the secondary but not yet be mixed in, hence

producing an unusual abundance in the currently visible spectrum.

.

It

is oversized

compared to a zero-age MS star of the same mass 1994Bell.

This might be understood as a layer of material accreted from the

primary, possibly related to the last layer stripped there.

Probably C and N were transferred to the

secondary while C was still being transformed to N

in the primary. Accreted material may still settle down to

deeper layers in the secondary but not yet be mixed in, hence

producing an unusual abundance in the currently visible spectrum.

In their calculations of the common envelope phase,

Hjellming & Taam (1991) found that the secondary accretes

approximately

![]() of red giant envelope material

before it expands to fill its Roche lobe. However this estimate

is based on calculations by Taam & Bodenheimer (1989) and highly dependent

on the assumed efficiency of envelope ejection. Marks & Sarna (1998)

point out that once it has filled its Roche lobe, it loses most of

the material accreted before the envelope is ejected such that the

net gain in mass is approximately

of red giant envelope material

before it expands to fill its Roche lobe. However this estimate

is based on calculations by Taam & Bodenheimer (1989) and highly dependent

on the assumed efficiency of envelope ejection. Marks & Sarna (1998)

point out that once it has filled its Roche lobe, it loses most of

the material accreted before the envelope is ejected such that the

net gain in mass is approximately

![]() .

It is

not clear which part of the envelope is predominantly accreted.

.

It is

not clear which part of the envelope is predominantly accreted.

1993Pollacco already noticed this

similarity in spectra between UU Sge and V477 Lyr and absorption

lines from the Balmer series, He II and N V ions while

He I lines are absent. They point out that the strength of

He II lines suggests that the Balmer lines are contaminated

by other members of the He II series, i.e., H + He II

![]() ,

H + He II

,

H + He II

![]() and H + He II

and H + He II

![]() Å. However, our observations only contain

H .

Å. However, our observations only contain

H .

The strong broad emission feature at 4635-4655 Å is remarkably similar in shape to the V477 Lyr observation by Shimansky et al. (2008). It seems to be common to sdO+MS pre-CVs and is also the strongest emission between 3950 and 5100 Å. It is remarkably similar in shape to the V477 Lyr observation by Shimansky et al. (2008). This confirms the similarity of these two systems, as already pointed out by Ritter (1986) and 1993Pollacco. There are, however, more smaller emission features visible which indicate that the secondary in V477 Lyr has greater influence on the total spectrum than the one in UU Sge. The broad feature is produced by very strong C and N emission lines in the secondary, as discussed in Sect. 5.2, while the rest of the spectrum is better fit by lower C and N abundances.

Emissions lines from a chromosphere are unlikely on the day-side

due to the strong external radiation field. Also the contribution

from a chromosphere on the night-side, if existent, is not likely

to explain the missing emission for He II

![]() in the combined spectrum (Fuhrmeister, private

communication).

in the combined spectrum (Fuhrmeister, private

communication).

6.3 Evolution of UU Sge

The evolution of UU Sge is still not completely understood. N is overabundant, indicating that the system reached the AGB, expelling the outer envelope and mixing N up to the observable surface. There was most likely no crucial interaction between the two stars until the primary envelope expanded to a size that it engulfed the secondary and started CEE.

This might be explained by an enrichment in C,

N and probably O that occurred

during the CEE and

only effects outer layers of the secondary, which might not yet be

in thermal equilibrium. Also the secondary might have

accreted C from an outer layer (3![]() process) while

the C N O cycle in the primary was

still working to convert C into N,

explaining why this element is not found enriched on the primary,

too.

process) while

the C N O cycle in the primary was

still working to convert C into N,

explaining why this element is not found enriched on the primary,

too.

Another possibility, although unlikely, is that the hot, oversized companion indicates that there were two AGB phases in the system and that the first was suppressed due to a too high mass-loss rate of the secondary. This would be another explanation for enrichment of heavier elements than He on the secondary, especially why there is C present. However, the secondary is too cold and its mass is too low to support this idea, since there is no proper mechanism known and its spectra look too ordinary. The primary could have gone through an earlier CEE of course, too, losing its envelope in more steps than just one.

The primary was stripped of its H-rich and He-rich

layers during the CEE, exposing a shell of N

underneath. Both components display lines with peculiar effects:

the He II

![]() absorption

suggests a layer of He on top of the N on the

primary, and a slightly lower

absorption

suggests a layer of He on top of the N on the

primary, and a slightly lower

![]() or some

unexplained emission from the secondary; the broad emission feature

on the secondary that reacts uniquely to abundance changes and

is the strongest emission feature within the entire wavelength range of the observation.

or some

unexplained emission from the secondary; the broad emission feature

on the secondary that reacts uniquely to abundance changes and

is the strongest emission feature within the entire wavelength range of the observation.

The broad emission feature is visible also in the other irradiated systems, e.g. the secondary of V477 Lyr (Shimansky et al. 2008), which is also 2.0-2.5 times larger than the radius of a zero-age MS star with comparable mass 1994Bell. This suggests a non-unique mechanism due to a similar evolution in both systems.

Table 4: Final results (see discussion):

Table 4 displays the derived parameters of UU Sge from Sect. 5.

7 Summary

We modelled both components of UU Sge with our state-of-the-art stellar atmosphere code PHOENIX, which treats the radiative transfer in an atmosphere self-consistently in the presence of an external radiation field and uses the newest extensive set of opacities currently available. In this respect our work goes beyond previous work.

Our analysis provides the temperature range of the primary and investigates the heating of the secondary's day-side. We find evidence for a large N enrichment on the primary, a depletion of C and O, and an upper limit for Si that is less than +0.3 dex solar. The lower He abundance in the sdO originates most likely from the loss of its envelope.

The observed broad emission blend at 4635-4655 Å in the secondary is stronger than the theoretical result by a factor of 3-5, which is indicative of the strong effects of ``over-ionisation'' by external radiation in high atmospheric layers for the C N O elements. This might be due to pollution of material accreted from the primary, which has not yet settled down to lower layers in the oversized secondary and explain C and N enrichment.

It is obvious that both stars have been greatly influenced in their evolution by their companion. The highly enriched metals observed in the primary and secondary could indicate that there is no mixing in the outer layers, since any counter mechanism that removes N into deeper layers would greatly decrease its abundance and stars would not produce such peculiar line strengths.

Convection on the day-side of the secondary is suppressed by the irradiation, the heat flux is dominated by radiation throughout the entire photosphere. Observationally the night-side appears to be heated by a horizontal flux, resulting in an earlier spectrum then expected for the secondary mass. Without a horizontal component of convective motion or radiative transfer (a 3D model), we cannot model the transfer of heat from layers of the irradiated half-sphere towards the undisturbed night-side, thus we expect that motion beyond the limits of our model is responsible for the heating of the secondary night-side.

Further analysis of UV and IR spectra could improve

the disentangling of primary and secondary spectra, since the UV is dominated

by the sdO, while the companion main source lies in IR. An

interesting line in

PG1144+005 is N V

![]() Å (high l,

Å (high l,

![]() transition), which is a strong emission line and

could be of considerable strength in UU Sge, too, hence

allowing us to confirm the N enrichment independently

to the doublet used here.

transition), which is a strong emission line and

could be of considerable strength in UU Sge, too, hence

allowing us to confirm the N enrichment independently

to the doublet used here.

Another fit to a secondary night-side only spectrum during primary eclipse could help to test the M-dwarf thesis, to find the horizontal heat flux beyond the terminator and to check for C, N and probably O enhancement on the surface of the secondary without the effect of irradiation.

Acknowledgements

We thank Stefan Czesla, Stefan Dreizler, Birgit Fuhrmeister, Roy Østensen, Jan Robrade, Brian Skiff and the unknown referee for helpful comments. A.C.W. was supported by the DFG (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft), project number HA 3457/7-1. Lowell Observatory provided hospitality, volleyball games and scientific support to ACW while this paper was written. Calculations were performed at the Hamburger Sternwarte Delta Opteron Cluster (``Nathan'') financially supported by the DFG and the State of Hamburg; at the Lowell Observatory's Apple Xeon Cluster (``Cuba''); and at the Höchstleistungs Rechenzentrum Nord (HLRN-II) Altix Computesystem (``ICE'' and ``XE''). We would like to thank these institutions for a generous allocation of computer time.

References

- Abell, G. O. 1966, ApJ, 144, 259 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Afsar, M., & Ibanoglu, C. 2008, MNRAS, 391, 802 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Allard, F., Hauschildt, P. H., Alexander, D. R., Tamanai, A., & Schweitzer, A. 2001, ApJ, 556, 357 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Asplund, M., Grevesse, N., & Sauval, A. J. 2005, in Cosmic Abundances as Records of Stellar Evolution and Nucleosynthesis, ASP Conf. Ser., 336, 25 (In the text)

- Aufdenberg, J. P. 2001, PASP, 113, 119 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Barman, T. S., Hauschildt, P. H., & Allard, F. 2004, ApJ, 614, 338 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Barman, T. S., Hauschildt, P. H., & Allard, F. 2005, ApJ, 632, 1132 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Beer, M. E., & Podsiadlowski, P. 2002, MNRAS, 335, 358 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Beer, M. E., Dray, L. M., King, A. R., & Wynn, G. A. 2007, MNRAS, 375, 1000 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Bell, S. A., Pollacco, D. L., & Hilditch, R. W. 1994, MNRAS, 270, 449 [NASA ADS] (In the text)

- Bond, H. E. 1976, PASP, 88, 192 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Bond, H. E., Liller, W., & Mannery, E. J. 1978, ApJ, 223, 252 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Brett, J. M., & Smith, R. C. 1993, MNRAS, 264, 641 [NASA ADS] (In the text)

- Budding, E. 1981, in Photometric and Spectroscopic Binary Systems, ed. E. B. Carling, & Z. Kopal, 405 (In the text)

- Budding, E., & Kopal, Z. 1980, Ap&SS, 73, 83 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Claret, A., & Giménez, A. 2001, in Lecture Notes in Physics, Binary Stars: Selected Topics on Observations and Physical Processes, ed. F. C. Lázaro, & M. J. Arévalo (Berlin: Springer Verlag), 563, 1

- de Greve, J. P., & Cugier, H. 1989, A&A, 211, 356 [NASA ADS] (In the text)

- de Kool, M., & Ritter, H. 1993, A&A, 267, 397 [NASA ADS]

- Dreizler, S., & Murdin, P. 2000, Encyclopedia of Astronomy and Astrophysics (In the text)

- Eggleton, P. P. 1983, ApJ, 268, 368 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Exter, K. M., Pollacco, D. L., Maxted, P. F. L., Napiwotzki, R., & Bell, S. A. 2005, MNRAS, 359, 315 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Hauschildt, P. H., & Baron, E. 1999, J. Comput. Appl. Math., 109, 41 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Herwig, F. 2005, ARA&A, 43, 435 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Hjellming, M. S., & Taam, R. E. 1991, ApJ, 370, 709 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Hoffleit, D. 1932, Harvard College Observatory Bulletin, 887, 9 [NASA ADS] (In the text)

- Hubeny, I., & Lanz, T. 2000, http://nova.astro.umd.edu/Synspec43/synspec-stark.html (In the text)

- Iben, I., & Tutukov, A. V. 1989, in Planetary Nebulae, ed. S. Torres-Peimbert, IAU Symp., 131, 505 (In the text)