| Issue |

A&A

Volume 503, Number 3, September I 2009

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Page(s) | 827 - 836 | |

| Section | Interstellar and circumstellar matter | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/200911706 | |

| Published online | 23 June 2009 | |

Radio properties of the low surface brightness

SNR G65.2+5.7![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

L. Xiao1 - W. Reich2 - E. Fürst2 - J. L. Han1

1 - National Astronomical

Observatories, Chinese Academy of

Sciences, Jia-20, Datun Road, Chaoyang District, Beijing 100012, PR China

2 - Max-Planck-Institut für Radioastronomie,

Auf dem Hügel 69, 53121 Bonn, Germany

Received 23 January 2009 / Accepted 9 April 2009

Abstract

Context. SNR G65.2+5.7 is one of few supernova remnants (SNRs) that have been optically detected. It is exceptionally bright in X-rays and the optical [O 3]-line. Its low surface brightness and large diameter ensure that radio observations of SNR G65.2+5.7 are technically difficult and thus have hardly been completed.

Aims. Many physical properties of this SNR, such as spectrum and polarization, can only be investigated by radio observations.

Methods. The ![]() 11 cm and

11 cm and ![]() 6 cm continuum and polarization observations of SNR G65.2+5.7 were completed with the Effelsberg 100-m and the Urumqi 25-m telescopes, respectively, to investigate the integrated spectrum, the spectral index distribution, and the magnetic field properties. Archival

6 cm continuum and polarization observations of SNR G65.2+5.7 were completed with the Effelsberg 100-m and the Urumqi 25-m telescopes, respectively, to investigate the integrated spectrum, the spectral index distribution, and the magnetic field properties. Archival ![]() 21 cm data of the Effelsberg 100-m telescope were also used.

21 cm data of the Effelsberg 100-m telescope were also used.

Results. The integrated flux densities of G65.2+5.7 at

![]() cm and

cm and ![]() cm are

cm are

![]() Jy and

Jy and

![]() Jy, respectively. The power-law spectrum (

Jy, respectively. The power-law spectrum (

![]() )

is well fitted by

)

is well fitted by

![]() from 83 MHz to 4.8 GHz. Spatial spectral variations are small. Along the northern shell, strong depolarizion is observed at both wavelengths. The southern filamentary shell of SNR G65.2+5.7 is polarized by as much as 54% at

from 83 MHz to 4.8 GHz. Spatial spectral variations are small. Along the northern shell, strong depolarizion is observed at both wavelengths. The southern filamentary shell of SNR G65.2+5.7 is polarized by as much as 54% at ![]() cm. There is significant depolarization at

cm. There is significant depolarization at

![]() cm and confusion with diffuse polarized Galactic emission. Using equipartition principle, we estimated the magnetic field strength for the southern filamentary shell to be between 20

cm and confusion with diffuse polarized Galactic emission. Using equipartition principle, we estimated the magnetic field strength for the southern filamentary shell to be between 20 ![]() G (filling factor 1) and 50

G (filling factor 1) and 50 ![]() G (filling factor 0.1). A faint HI shell may be associated with the SNR.

G (filling factor 0.1). A faint HI shell may be associated with the SNR.

Conclusions. Despite its unusually strong X-ray and optical emission and its very low surface brightness, the radio properties of SNR G65.2+5.7 are found to be typical of evolved shell-type SNRs. SNR G65.2+5.7 may be expanding in a pre-blown cavity as indicated by a deficit of HI gas and a possible HI-shell.

Key words: ISM: supernova remnants - ISM: magnetic fields - radio continuum: ISM - radiation mechanisms: non-thermal

1 Introduction

SNRs of low radio surface brightness and large diameter are difficult to identify in radio

continuum surveys. The weakest source detected in our Galaxy is SNR G156.2+5.7 (Reich et al. 1992),

which has a surface brightness

![]() ,

and SNR G65.2+5.7 is a similar weak object, whose low surface brightness

may be caused by a low ambient magnetic field strength or a low electron density.

In most cases, the supernova has exploded in a low-density medium, for instance in an interarm

region or in a pre-existing cavity. In the case of a pre-existing cavity substantial radio emission

is visible for only a relatively short time interval as the shock collides with the dense shell.

,

and SNR G65.2+5.7 is a similar weak object, whose low surface brightness

may be caused by a low ambient magnetic field strength or a low electron density.

In most cases, the supernova has exploded in a low-density medium, for instance in an interarm

region or in a pre-existing cavity. In the case of a pre-existing cavity substantial radio emission

is visible for only a relatively short time interval as the shock collides with the dense shell.

Gull et al. (1977) first identified G65.2+5.7 as a large diameter SNR located in the Cygnus region

in an optical emission line survey, where it appeared

to be exceptionally bright in [O 3]. This is indicative of high shock

velocities typically for an expanding SNR shell. Reich et al. (1979) used

the Effelsberg 100-m telescope at

![]() cm to map G65.2+5.7

and confirmed its identification as a SNR by its non-thermal emission.

cm to map G65.2+5.7

and confirmed its identification as a SNR by its non-thermal emission.

G65.2+5.7 is a bright soft X-ray source for which Shelton et al. (2004) analysed ROSAT PSPC data, classifying the SNR as a ``thermal composite'' object with a cool, dense shell without X-ray emission. Bright centrally peaked thermal X-ray emission dominates the interior of these SNRs, although they are rare. W44 is another example (Cox et al. 1999), which is younger than G65.2+5.7.

Distance estimates were made by various authors. Boumis et al. (2004) used proper

motion and expansion measurements of the remnant's optical filament

edges and obtained ![]() pc. In the following, we assume a

distance of 800 pc. The apparent size of G65.2+5.7 is about

pc. In the following, we assume a

distance of 800 pc. The apparent size of G65.2+5.7 is about

![]() (Gull et al. 1977), corresponding to a physical size of

56 pc

(Gull et al. 1977), corresponding to a physical size of

56 pc ![]() 46 pc. The centre of the SNR is located about 80 pc above

the Galactic plane. G65.2+5.7 appears to be an evolved object,

although its age is uncertain: It may be as old as

46 pc. The centre of the SNR is located about 80 pc above

the Galactic plane. G65.2+5.7 appears to be an evolved object,

although its age is uncertain: It may be as old as

![]() years

if one assumes an average shock velocity of

years

if one assumes an average shock velocity of ![]() 50 km s-1 (Reich et al. 1979; Gull et al. 1977). Optical observations show the

velocities in the range between 90 km s-1 and 140 km s-1(Mavromatakis et al. 2002). ROSAT X-ray data infer shock velocities of about

400 km s-1 (Schaudel et al. 2002), which implies an age of

50 km s-1 (Reich et al. 1979; Gull et al. 1977). Optical observations show the

velocities in the range between 90 km s-1 and 140 km s-1(Mavromatakis et al. 2002). ROSAT X-ray data infer shock velocities of about

400 km s-1 (Schaudel et al. 2002), which implies an age of

![]() years.

years.

The Princeton-Arecibo pulsar survey found a pulsar, PSR J1931+30,

in the direction of G65.2+5.7 (Camilo et al. 1996). From its

dispersion measure of ![]() cm-3 pc, a distance of about

3 kpc is inferred, which excludes a physical association with G65.2+5.7.

cm-3 pc, a distance of about

3 kpc is inferred, which excludes a physical association with G65.2+5.7.

The only radio observations of G65.2+5.7 have been those by

Reich et al. (1979) at

![]() cm and the low-resolution, low-frequency observations by

Kovalenko et al. (1994), reflecting the difficulty in mapping these faint large-diameter

objects. With the availability of new sensitive and highly stable

receivers, it is now possible to map this object also at higher

frequencies with arc minute angular resolution and investigate

its spectral properties and magnetic field structure. We describe new

sensitive radio measurements in total power and linear polarization

at

cm and the low-resolution, low-frequency observations by

Kovalenko et al. (1994), reflecting the difficulty in mapping these faint large-diameter

objects. With the availability of new sensitive and highly stable

receivers, it is now possible to map this object also at higher

frequencies with arc minute angular resolution and investigate

its spectral properties and magnetic field structure. We describe new

sensitive radio measurements in total power and linear polarization

at ![]() 11 cm and

11 cm and ![]() 6 cm of G65.2+5.7 and present results

on the spectral and polarization analysis in Sect. 2.

A brief discussion of the radio results with respect to observations at other

wavelengths is given in Sect. 3, followed by a summary in Sect. 4.

6 cm of G65.2+5.7 and present results

on the spectral and polarization analysis in Sect. 2.

A brief discussion of the radio results with respect to observations at other

wavelengths is given in Sect. 3, followed by a summary in Sect. 4.

Table 1: Observational parameters

2 Observations and result analyses

Continuum and linear polarization observations of G65.2+5.7 at ![]() 6 cm (4800 MHz)

were completed with the 25-m telescope at Nanshan station of the Urumqi Observatory.

The

6 cm (4800 MHz)

were completed with the 25-m telescope at Nanshan station of the Urumqi Observatory.

The ![]() 6 cm receiver is a copy of a receiver used at the Effelsberg 100-m

telescope and was installed in 2004 for the

6 cm receiver is a copy of a receiver used at the Effelsberg 100-m

telescope and was installed in 2004 for the ![]() 6 cm polarization

survey of the Galactic plane (Sun et al. 2007).

Sun et al. (2006) described the performance of the receiving

system in some detail. Between 2006 and 2007, nine observations of

G65.2+5.7 were completed, which were centered at

6 cm polarization

survey of the Galactic plane (Sun et al. 2007).

Sun et al. (2006) described the performance of the receiving

system in some detail. Between 2006 and 2007, nine observations of

G65.2+5.7 were completed, which were centered at

![]() ,

,

![]() .

The map size,

.

The map size, ![]() RA

RA ![]()

![]() Dec, was

Dec, was

![]() .

The maps were scanned either along the RA- or

Dec-direction with a telescope scan velocity of

.

The maps were scanned either along the RA- or

Dec-direction with a telescope scan velocity of

![]() /s.

/s.

The observations of G65.2+5.7 at ![]() 11 cm (2639 MHz) were completed with a

receiver installed at the secondary focus of the Effelsberg 100-m telescope

in 2005.

They were carried out in the same way as the observations with the Urumqi telescope.

G65.2+5.7 was observed seven times in autumn 2007 mostly in clear sky.

In Table 1, we list the parameters of the

11 cm (2639 MHz) were completed with a

receiver installed at the secondary focus of the Effelsberg 100-m telescope

in 2005.

They were carried out in the same way as the observations with the Urumqi telescope.

G65.2+5.7 was observed seven times in autumn 2007 mostly in clear sky.

In Table 1, we list the parameters of the ![]() 6 cm and

6 cm and

![]() 11 cm observations with the data of the main calibrator 3C 286.

The

11 cm observations with the data of the main calibrator 3C 286.

The ![]() 11 cm observations were carried out with a

8-channel narrow band polarimeter. Each channel has a bandwidth of

10 MHz. The centre frequencies are separated by 10 MHz and range from

2604 MHz to 2674 MHz. The 9th broadband-channel has a

bandwidth of 80 MHz and is centered on 2639 MHz. This channel was used

for all observations in which no narrow band interference was present,

which was the case for the observations of G65.2+5.7.

11 cm observations were carried out with a

8-channel narrow band polarimeter. Each channel has a bandwidth of

10 MHz. The centre frequencies are separated by 10 MHz and range from

2604 MHz to 2674 MHz. The 9th broadband-channel has a

bandwidth of 80 MHz and is centered on 2639 MHz. This channel was used

for all observations in which no narrow band interference was present,

which was the case for the observations of G65.2+5.7.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=-90,width=8.5cm]{11706f1a.ps}\par\includegraphics[angle=-90,width=8.5cm]{11706f1b.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/33/aa11706-09/Timg54.png) |

Figure 1:

The Urumqi |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=-90,width=8.5cm]{11706f2a.ps}\par\includegraphics[angle=-90,width=8.5cm]{11706f2b.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/33/aa11706-09/Timg55.png) |

Figure 2:

Same as Fig. 1, but for the Effelsberg |

| Open with DEXTER | |

The data processing was completed in exactly the same way as described by Xiao et al. (2008) for the observations of the SNR S147, an object of similar size and faintness as G65.2+5.7. In brief, the individual maps for Stokes I, U, and Q were checked and low quality data caused by interference were removed. The baselines for Stokes Iwere corrected by subtracting a second order polynomial fit to the lower emission envelope; this step removed ground emission variations and also the smooth increase in Galactic emission towards the Galactic plane evident in the long scans. We suppressed scanning effects for U/Q maps by applying the ``unsharp masking'' method described by Sofue & Reich (1979). Finally, all maps were combined using the PLAIT-algorithm (Emerson & Gräve 1988).

2.1 Total intensity and linear polarization maps

The Urumqi ![]() 6 cm total intensity map of G65.2+5.7 and the corresponding

polarization intensity map superimposed with vectors in the E-field direction

are shown in Fig. 1. From low-intensity areas in the maps,

we measured an rms-noise in total intensity and in linear polarized intensity

of 0.7 mK

6 cm total intensity map of G65.2+5.7 and the corresponding

polarization intensity map superimposed with vectors in the E-field direction

are shown in Fig. 1. From low-intensity areas in the maps,

we measured an rms-noise in total intensity and in linear polarized intensity

of 0.7 mK ![]() and 0.3 mK

and 0.3 mK ![]() ,

respectively. The

,

respectively. The ![]() 11 cm

maps are shown in

Fig. 2. The rms-noise was measured to be 3.5 mK

11 cm

maps are shown in

Fig. 2. The rms-noise was measured to be 3.5 mK ![]() in total intensity

and 1.7 mK

in total intensity

and 1.7 mK ![]() in linear polarized intensity. Because of the higher

angular resolution of the

in linear polarized intensity. Because of the higher

angular resolution of the ![]() 11 cm map of

11 cm map of

![]() ,

the filamentary elliptical shell

is more clearly detected.

,

the filamentary elliptical shell

is more clearly detected.

For the spectral index analysis we also used an archival ![]() 21 cm map obtained

with the Effelsberg 100-m telescope in November 1987 at 1408 MHz with a bandwidth

of 20 MHz and an angular resolution of

21 cm map obtained

with the Effelsberg 100-m telescope in November 1987 at 1408 MHz with a bandwidth

of 20 MHz and an angular resolution of

![]() .

These observations were made in due course with a

.

These observations were made in due course with a ![]() 21 cm Galactic plane

survey in total intensity (Reich et al. 1990), which covers the plane within an interval of

21 cm Galactic plane

survey in total intensity (Reich et al. 1990), which covers the plane within an interval of

![]() in latitude, so that a small part of G65.2+5.7 is included there.

Polarization data were taken from a section of the ``

in latitude, so that a small part of G65.2+5.7 is included there.

Polarization data were taken from a section of the ``![]() 21 cm

Effelsberg Medium Latitude Survey'' (Reich et al. 2004), which was combined with data from

the DRAO 1.4 GHz polarization survey (Wolleben et al. 2006) to help ensure detection

of any missing large-scale polarized emission. The

21 cm

Effelsberg Medium Latitude Survey'' (Reich et al. 2004), which was combined with data from

the DRAO 1.4 GHz polarization survey (Wolleben et al. 2006) to help ensure detection

of any missing large-scale polarized emission. The ![]() 21 cm map is shown

in Fig. 3.

21 cm map is shown

in Fig. 3.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm, angle=-90]{11706f3.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/33/aa11706-09/Timg58.png) |

Figure 3:

Effelsberg |

| Open with DEXTER | |

2.2 The integrated radio spectrum

To estimate the integrated flux density of the remnant, we

subtracted 20 bright point-like sources by Gaussian fitting within the area of the SNR,

and a few just outside,

from the ![]() 11 cm map and 16 sources from the

11 cm map and 16 sources from the ![]() 6 cm map.

The sources are listed in Table 2. The position accuracy of

the two maps is about

6 cm map.

The sources are listed in Table 2. The position accuracy of

the two maps is about

![]() on average, which was estimated by comparing the source

positions with those from the NVSS (Condon et al. 1998).

on average, which was estimated by comparing the source

positions with those from the NVSS (Condon et al. 1998).

Table 2:

Bright sources in the area of SNR G65.2+5.7 fitted from the

Effelsberg ![]() 11 cm and Urumqi at

11 cm and Urumqi at ![]() 6 cm maps, including

source positions, flux densities from the NVSS at

6 cm maps, including

source positions, flux densities from the NVSS at ![]() 21 cm, as well as spectral indices. Sources

``outside'' G65.2+5.7 are listed for completeness.

21 cm, as well as spectral indices. Sources

``outside'' G65.2+5.7 are listed for completeness.

We used the method of temperature-versus-temperature (TT) plot (Turtle et al. 1962)

to adjust the base-levels of the entire SNR area at two wavelengths. Both maps

were convolved to a common angular resolution of

![]() .

In agreement with the TT-plot results for three different shell regions (see Sect. 3.3),

we found a constant offset of

.

In agreement with the TT-plot results for three different shell regions (see Sect. 3.3),

we found a constant offset of

![]() at

at ![]() 6 cm.

At

6 cm.

At ![]() 11 cm, we subtracted a ``twisted'' surface, which was defined by specific

correction values at the four corners (3, 3, -6, and 3 mK

11 cm, we subtracted a ``twisted'' surface, which was defined by specific

correction values at the four corners (3, 3, -6, and 3 mK ![]() from lower left,

right to upper left, right) of the map.

The integrated flux densities were obtained by integrating the emission enclosed within polygons

just outside the periphery of the SNR. From variations outside the SNR, we

estimated a remaining uncertainty in the base-level setting of

from lower left,

right to upper left, right) of the map.

The integrated flux densities were obtained by integrating the emission enclosed within polygons

just outside the periphery of the SNR. From variations outside the SNR, we

estimated a remaining uncertainty in the base-level setting of

![]() at

at ![]() 6 cm and

6 cm and

![]() at

at ![]() 11 cm.

By assuming an estimated 5% calibration uncertainty, we obtained

integrated flux densities of

11 cm.

By assuming an estimated 5% calibration uncertainty, we obtained

integrated flux densities of

![]() Jy at

Jy at

![]() 6 cm and

6 cm and

![]() Jy at

Jy at ![]() 11 cm.

11 cm.

In Fig. 4, these data are plotted together with flux density

values from Reich et al. (1979) (408 MHz and 1415 MHz) and Kovalenko et al. (1994)

(83 MHz and 111 MHz). All data are summarized in Table 3. For the Effelsberg ![]() 21 cm map

observed in 1987,

we obtained the same flux density of

21 cm map

observed in 1987,

we obtained the same flux density of

![]() Jy for G65.2+5.7 that was obtained

for the map published by Reich et al. (1979). We subtracted the flux densities of

point-like sources listed in Table 2 by assuming a spectral index

of

Jy for G65.2+5.7 that was obtained

for the map published by Reich et al. (1979). We subtracted the flux densities of

point-like sources listed in Table 2 by assuming a spectral index

of

![]() ,

which we decided on after caculating the average by weighting the source

spectral indices according to their flux densities. The linear fit to the

integrated flux densities of G65.2+5.7 as shown in Fig. 4 yields a spectral

index of

,

which we decided on after caculating the average by weighting the source

spectral indices according to their flux densities. The linear fit to the

integrated flux densities of G65.2+5.7 as shown in Fig. 4 yields a spectral

index of

![]() .

.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm, angle=-90]{11706f4.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/33/aa11706-09/Timg72.png) |

Figure 4:

Spectrum of the integrated radio flux densities of G65.2+5.7.

The spectral index is

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

2.3 TT-plot spectral analysis

The TT-plot method used for relative zero-level setting in Sect. 2.2 was also used to

investigate the spectrum of distinct emission structures in a way independent of

a consistent base-level setting of both maps.

Spectral index variations of structures within a source could then be recognized or

the integrated spectrum checked.

We smoothed both maps to

![]() and applied this method for three different sections of the G65.2+5.7 shell,

which are marked in Fig. 6.

The results are shown in Fig. 5 for the

and applied this method for three different sections of the G65.2+5.7 shell,

which are marked in Fig. 6.

The results are shown in Fig. 5 for the ![]() 11 cm/

11 cm/![]() 6 cm data.

A clear temperature-temperature relation is evident in all cases. The same TT-plot procedure

was used for the

6 cm data.

A clear temperature-temperature relation is evident in all cases. The same TT-plot procedure

was used for the ![]() 21 cm/

21 cm/![]() 6 cm data.

The temperature spectral index

6 cm data.

The temperature spectral index

![]() found from fitting the

slope is

found from fitting the

slope is

![]() and

and

![]() for the southern shell,

for the southern shell,

![]() and

and

![]() for the northeastern shell, and

for the northeastern shell, and

![]() and

and

![]() for the western shell.

The error in

for the western shell.

The error in ![]() for the diffuse western part of the shell region is large, probably due to its weak

emission and confusion with weak unresolved background sources, which could not be subtracted.

All values agree with both each other and the spectral index of the integrated spectrum to within the errors.

However, we always obtain somewhat steeper spectra for the

for the diffuse western part of the shell region is large, probably due to its weak

emission and confusion with weak unresolved background sources, which could not be subtracted.

All values agree with both each other and the spectral index of the integrated spectrum to within the errors.

However, we always obtain somewhat steeper spectra for the ![]() 21 cm/

21 cm/![]() 6 cm data

than the

6 cm data

than the ![]() 11 cm/

11 cm/![]() 6 cm data, which reflects the slightly lower

integrated flux density at

6 cm data, which reflects the slightly lower

integrated flux density at ![]() 11 cm relative to the fit shown in Fig. 4

and the marginally higher value we obtained at

11 cm relative to the fit shown in Fig. 4

and the marginally higher value we obtained at ![]() 21 cm.

21 cm.

Table 3:

Integrated flux densities of G65.2+5.7, before (![]() )

and after (

)

and after (

![]() )

subtraction of point-like sources within the boundary of SNR.

)

subtraction of point-like sources within the boundary of SNR.

![\begin{figure}

\par\mbox{\includegraphics[angle=-90,width=6cm]{11706f5a.ps}\incl...

...11706f5b.ps}\includegraphics[angle=-90,width=6cm]{11706f5c.ps} }

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/33/aa11706-09/Timg82.png) |

Figure 5:

T-T plots for different shell sections of G65.2+5.7 between

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=-90, width=8cm]{11706f6.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/33/aa11706-09/Timg84.png) |

Figure 6:

Spectral index map calculated between |

| Open with DEXTER | |

2.4 Spectral index map

The Urumqi ![]() 6 cm and the Effelsberg

6 cm and the Effelsberg ![]() 11 cm maps with point-like

sources removed and base-level corrected were both convolved to a common angular

resolution of

11 cm maps with point-like

sources removed and base-level corrected were both convolved to a common angular

resolution of

![]() .

We calculated the spectral index for each pixel from

the brightness temperatures at the two frequencies.

We defined a lower intensity limit of 4 mK

.

We calculated the spectral index for each pixel from

the brightness temperatures at the two frequencies.

We defined a lower intensity limit of 4 mK ![]() and 12 mK

and 12 mK ![]() for the

for the

![]() 6 cm and

6 cm and ![]() 11 cm map, respectively,

to achieve reasonable spectral indices without the influence of noise

and local distortions.

We display the spectral index map between

11 cm map, respectively,

to achieve reasonable spectral indices without the influence of noise

and local distortions.

We display the spectral index map between ![]() 6 cm and

6 cm and ![]() 11 cm in

Fig. 6. Possible remaining variations in

the base-levels at

11 cm in

Fig. 6. Possible remaining variations in

the base-levels at ![]() 11 cm or

11 cm or ![]() 6 cm cause a systematic uncertainty in the

spectral indices of

6 cm cause a systematic uncertainty in the

spectral indices of

![]() .

The uncertainty is larger when

total intensities are lower.

.

The uncertainty is larger when

total intensities are lower.

The filament emerging from the southern shell towards the north has a somewhat steeper spectrum

than that of the southern shell. This is confirmed by

![]() obtained from

TT-plot, although this spectral index value is within the errors of those obtained for the other shell regions.

obtained from

TT-plot, although this spectral index value is within the errors of those obtained for the other shell regions.

Reich et al. (1979) found an indication of spectral flattening towards

the centre of G65.2+5.7 of about

![]() when

comparing their Effelsberg

when

comparing their Effelsberg ![]() 21 cm map with low-resolution data

at 408 MHz (Haslam et al. 1974). This finding cannot be verified by the

present data. The emission in the central area is too faint

at higher frequencies to derive meaningful spectral indices in relation to

the base-level uncertainties.

21 cm map with low-resolution data

at 408 MHz (Haslam et al. 1974). This finding cannot be verified by the

present data. The emission in the central area is too faint

at higher frequencies to derive meaningful spectral indices in relation to

the base-level uncertainties.

2.5 The linear polarization properties of G65.2+5.7

The ![]() 6 cm and

6 cm and ![]() 11 cm polarization maps shown in

the lower panels of Figs. 1 and 2 indicate the similar polarization features at

the two frequencies. Four polarized patches appear at

11 cm polarization maps shown in

the lower panels of Figs. 1 and 2 indicate the similar polarization features at

the two frequencies. Four polarized patches appear at ![]() 6 cm, three

smaller and fainter ones located in the northern area of G65.2+5.7, and a single large patch

covering the southern shell and part of the inner area of the SNR. Apart from the enhanced

polarization along the SNR southern shell, most of the polarization

structures might originate from polarized diffuse interstellar emission

possibly mixed with polarized emission from the SNR of about similar

strength. We note low polarized emission along the northern shell at both

wavelengths.

6 cm, three

smaller and fainter ones located in the northern area of G65.2+5.7, and a single large patch

covering the southern shell and part of the inner area of the SNR. Apart from the enhanced

polarization along the SNR southern shell, most of the polarization

structures might originate from polarized diffuse interstellar emission

possibly mixed with polarized emission from the SNR of about similar

strength. We note low polarized emission along the northern shell at both

wavelengths.

As shown in Fig. 3 the ![]() 21 cm polarization data do not indicate any

polarized emission at all compared to G65.2+5.7, since neither the polarized intensity nor the

polarization vectors change significantly in the direction of the SNR relative to its

surroundings. This indicates that most of the polarized emission seen in

this area at

21 cm polarization data do not indicate any

polarized emission at all compared to G65.2+5.7, since neither the polarized intensity nor the

polarization vectors change significantly in the direction of the SNR relative to its

surroundings. This indicates that most of the polarized emission seen in

this area at ![]() 21 cm originates from the foreground within the distance to

G65.2+5.7 of about 800 pc.

21 cm originates from the foreground within the distance to

G65.2+5.7 of about 800 pc.

The large-scale emission components are missing in the two polarization maps

at ![]() 6 cm and

6 cm and ![]() 11 cm, because the end-points

of each scan in the individual U and Q maps were set to zero during data processing.

This limits the interpretation of polarization structures (Reich 2006),

except for the strong polarized region along the southern shell at

11 cm, because the end-points

of each scan in the individual U and Q maps were set to zero during data processing.

This limits the interpretation of polarization structures (Reich 2006),

except for the strong polarized region along the southern shell at ![]() 6 cm.

6 cm.

Following Sun et al. (2007), we used the WMAP polarization data at 22.8 GHz (Page et al. 2007)

to recover missing large-scale structures at ![]() 6 cm.

There is no signature of G65.2+5.7 in the Stokes U and Q maps at 22.8 GHz.

The convolved 22.8 GHz PI map shows

a smooth intensity increase below Galactic latitudes of about

6 cm.

There is no signature of G65.2+5.7 in the Stokes U and Q maps at 22.8 GHz.

The convolved 22.8 GHz PI map shows

a smooth intensity increase below Galactic latitudes of about

![]() .

Above

.

Above

![]() ,

the orientation of the polarization B-vectors is less regular (Fig. 7).

We convolved the WMAP 22.8 GHz U and Q maps corresponding to an angular resolution of

,

the orientation of the polarization B-vectors is less regular (Fig. 7).

We convolved the WMAP 22.8 GHz U and Q maps corresponding to an angular resolution of

![]() and

scaled them to 4.8 GHz (

and

scaled them to 4.8 GHz (![]() 6 cm) assuming a temperature spectral index of

6 cm) assuming a temperature spectral index of

![]() ,

which was taken from the spectral index map of total intensities

between 408 MHz and 1420 MHz by Reich & Reich (1988).

We assume the same spectral index for the Galactic diffuse polarized emission.

The difference between the scaled WMAP data and the

,

which was taken from the spectral index map of total intensities

between 408 MHz and 1420 MHz by Reich & Reich (1988).

We assume the same spectral index for the Galactic diffuse polarized emission.

The difference between the scaled WMAP data and the ![]() 6 cm maps, when convolved to the

same beam size of

6 cm maps, when convolved to the

same beam size of

![]() ,

results in an offset of

,

results in an offset of

![]() for Stokes U and

for Stokes U and

![]() for Stokes Q, which is equivalent to

for Stokes Q, which is equivalent to

![]() of

polarized intensity. The offsets were added to the original

of

polarized intensity. The offsets were added to the original ![]() 6 cm U and

Q data.

The polarized intensity map at

6 cm U and

Q data.

The polarized intensity map at ![]() 6 cm derived from the

restored data is shown in Fig. 8.

6 cm derived from the

restored data is shown in Fig. 8.

We then compared the ![]() 6 cm polarization maps with and without

absolute zero-level restoration. We found in general that the addition of missing

large-scale polarization did not change the morphology of the observed polarization

at

6 cm polarization maps with and without

absolute zero-level restoration. We found in general that the addition of missing

large-scale polarization did not change the morphology of the observed polarization

at ![]() 6 cm significantly. The polarized signal from the southern

shell of G65.2+5.7 was strong enough to remain almost unchanged when adding the

large-scale emission component. Strong polarization emission of the diffuse

interstellar medium near to the Galactic plane

in the south-eastern area of the map is unrelated to G65.2+5.7.

However, we note some changes in areas of lower polarized emission.

For instance, the polarized emisssion is more pronounced in

the direction of the extended HII-region LBN 150, also known as Sh2-96,

(

6 cm significantly. The polarized signal from the southern

shell of G65.2+5.7 was strong enough to remain almost unchanged when adding the

large-scale emission component. Strong polarization emission of the diffuse

interstellar medium near to the Galactic plane

in the south-eastern area of the map is unrelated to G65.2+5.7.

However, we note some changes in areas of lower polarized emission.

For instance, the polarized emisssion is more pronounced in

the direction of the extended HII-region LBN 150, also known as Sh2-96,

(

![]() ,

J2000) in Fig. 8, which

itself does not emit polarized emission, but may act as a Faraday screen by rotating

polarized emission from larger distances.

,

J2000) in Fig. 8, which

itself does not emit polarized emission, but may act as a Faraday screen by rotating

polarized emission from larger distances.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=-90,width=8.6cm]{11706f7.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/33/aa11706-09/Timg94.png) |

Figure 7:

The WMAP 22.8 GHz map.

The total intensity emission (grey-scale) map is smoothed to an angular resolution of

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

The procedure for recovering missing large-scale emission by using the WMAP polarization data,

needs to be modified in case the Faraday rotation is too large or becomes significant

at longer wavelengths because of the

![]() -dependence of the polarization angle for

a given RM. Therefore, it seems questionable that the

-dependence of the polarization angle for

a given RM. Therefore, it seems questionable that the ![]() 11 cm U and Q maps should by corrected

in the same way as the

11 cm U and Q maps should by corrected

in the same way as the ![]() 6 cm polarization data.

The level of Galactic PI at

6 cm polarization data.

The level of Galactic PI at ![]() 11 cm, however, is calculated to be about

11 cm, however, is calculated to be about

![]() .

This large-scale polarized signal needs to be compared with the observed

polarized signals at

.

This large-scale polarized signal needs to be compared with the observed

polarized signals at ![]() 11 cm,

which are only three times stronger on the inner side of the southern shell and only twice as strong

for the average polarization of the entire SNR.

We conclude that the missing large-scale polarization is a serious contamination of the

11 cm,

which are only three times stronger on the inner side of the southern shell and only twice as strong

for the average polarization of the entire SNR.

We conclude that the missing large-scale polarization is a serious contamination of the

![]() 11 cm data and any RMs calculated from the

11 cm data and any RMs calculated from the ![]() 11 cm and

the

11 cm and

the ![]() 6 cm data will by affected by an unknown amount by that effect.

6 cm data will by affected by an unknown amount by that effect.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=-90,width=8.6cm]{11706f8.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/33/aa11706-09/Timg97.png) |

Figure 8:

The |

| Open with DEXTER | |

2.6 The northern area of G65.2+5.7

The polarized emission seen in the northern area of the SNR is much weaker than in the southern

area and not very clearly related to the SNR shell. Along the northern shell,

depolarization at both ![]() 11 cm and

11 cm and ![]() 6 cm is evident, which may

have various causes. Firstly, background polarization is depolarized by small-scale

magneto-ionic fluctuations in the shell; secondly,

polarized emission from the SNR shell has a different orientation and cancels, at least partly, the

background emission; or, thirdly, Faraday rotation in the shell rotates background polarization

in such a way that it cancels the foreground polarization.

A combination of the different scenarios is certainly possible.

We note that Mavromatakis et al. (2002) measured the highest thermal electron densities for

the optical filaments in the northern shell, which may explain the high depolarization.

The low percentage polarization in the northern area, compared to that of the southern shell, may

indicate a less regular magnetic field. We conclude that the magnetic field

properties along the northern shell cannot be determined reliably from the data available to us.

6 cm is evident, which may

have various causes. Firstly, background polarization is depolarized by small-scale

magneto-ionic fluctuations in the shell; secondly,

polarized emission from the SNR shell has a different orientation and cancels, at least partly, the

background emission; or, thirdly, Faraday rotation in the shell rotates background polarization

in such a way that it cancels the foreground polarization.

A combination of the different scenarios is certainly possible.

We note that Mavromatakis et al. (2002) measured the highest thermal electron densities for

the optical filaments in the northern shell, which may explain the high depolarization.

The low percentage polarization in the northern area, compared to that of the southern shell, may

indicate a less regular magnetic field. We conclude that the magnetic field

properties along the northern shell cannot be determined reliably from the data available to us.

2.7 The southern shell of G65.2+5.7

As shown in Fig. 9 the polarized emission at ![]() 6 cm reaches its maximum at

the southern shell. The polarization percentage of the southern shell locally is as high

as 54% at

6 cm reaches its maximum at

the southern shell. The polarization percentage of the southern shell locally is as high

as 54% at ![]() 6 cm. Lower polarized emission at

6 cm. Lower polarized emission at ![]() 11 cm

at the same position indicates strong depolarization at this wavelength.

Inside the shell the polarization percentage at

11 cm

at the same position indicates strong depolarization at this wavelength.

Inside the shell the polarization percentage at ![]() 11 cm is about 38%.

11 cm is about 38%.

As expected for an evolved SNR, a well ordered magnetic field is detected in the shell.

Rotating the polarization E-vectors shown in Fig. 1 by

![]() results in an observed

magnetic field direction that is almost tangential to the shell (Fig. 8).

Thus, the magnetic field intrinsic to the shell is tangential when the Faraday rotation

is low. If we accept the deviations (of about

results in an observed

magnetic field direction that is almost tangential to the shell (Fig. 8).

Thus, the magnetic field intrinsic to the shell is tangential when the Faraday rotation

is low. If we accept the deviations (of about

![]() )

from tangential orientations as

the result of intrinsic plus foreground RMs, then the total RM should not exceed about

)

from tangential orientations as

the result of intrinsic plus foreground RMs, then the total RM should not exceed about

![]() .

.

We estimated the contribution of RM from the foreground interstellar medium. The NE2001 model

of Cordes & Lazio (2002) predicts a dispersion measure of

![]() in the direction of G65.2+5.7.

The magnetic field strength along the light-of-sight,

B||, is about

in the direction of G65.2+5.7.

The magnetic field strength along the light-of-sight,

B||, is about ![]()

![]() G, which is a typical value

for the local regular magnetic field (Han et al. 2006). Then RM is calculated by

RM = 0.81 B|| DM resulting in about

G, which is a typical value

for the local regular magnetic field (Han et al. 2006). Then RM is calculated by

RM = 0.81 B|| DM resulting in about

![]() .

This Galactic foreground RM has little

effect (only a few degrees) on the polarization vector orientation measured at

.

This Galactic foreground RM has little

effect (only a few degrees) on the polarization vector orientation measured at ![]() 6 cm.

6 cm.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=-90,width=8.5cm]{11706f9a.ps}\par\includegraphics[angle=-90,width=8.5cm]{11706f9b.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/33/aa11706-09/Timg104.png) |

Figure 9:

The observed polarized intensities in grey scales for the southern shell

at |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=18cm, angle=0]{11706f10.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/33/aa11706-09/Timg106.png) |

Figure 10:

The |

| Open with DEXTER | |

When rotating the E-vectors at ![]() 11 cm in the same way as at

11 cm in the same way as at ![]() 6 cm,

magnetic directions that differ up to

6 cm,

magnetic directions that differ up to

![]() from a tangential orientation direction imply

values of RM of the order of 150 rad m-2 for the

from a tangential orientation direction imply

values of RM of the order of 150 rad m-2 for the ![]() 11 cm data to agree with a

tangential magnetic field direction. This large RM disagrees with the

11 cm data to agree with a

tangential magnetic field direction. This large RM disagrees with the ![]() 6 cm data.

However, as stated above, the observed level of the

6 cm data.

However, as stated above, the observed level of the ![]() 11 cm polarized emission is too low

to be unaffected by unrelated Galactic large-scale emission. This needs to be taken

into account before calculating any RM for G65.2+5.7, but we have insufficient information

to do this.

Clearly, we require observations at wavelengths shorter than

11 cm polarized emission is too low

to be unaffected by unrelated Galactic large-scale emission. This needs to be taken

into account before calculating any RM for G65.2+5.7, but we have insufficient information

to do this.

Clearly, we require observations at wavelengths shorter than ![]() 6 cm of sufficiently

high angular resolution

to calculate the RM properties of G65.2+5.7 in combination with our

6 cm of sufficiently

high angular resolution

to calculate the RM properties of G65.2+5.7 in combination with our ![]() 6 cm data

and thus contain the suggested tangential magnetic field orientation along its southern shell.

6 cm data

and thus contain the suggested tangential magnetic field orientation along its southern shell.

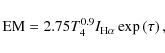

We can estimate the magnetic field strength in the southern shell by assuming

energy equipartition between the magnetic field and electrons and protons

in the SNR-shell using the formula by Fürst & Reich (2004), where the radius of a source

is replaced by the volume V to deal with a shell section

|

(1) |

We extrapolated the integrated

Another approach to estimating equipartition magnetic fields in SNRs was described by Foster (2005).

This method results in a magnetic field strength of

![]() G for

G for

![]() over a frequency range of

over a frequency range of

![]() GHz,

a line-of-sight extension of the radio-emitting region of 50 pc, and a radio intensity of the southern shell

of

GHz,

a line-of-sight extension of the radio-emitting region of 50 pc, and a radio intensity of the southern shell

of

![]() .

We conclude that the magnetic field of the southern shell has a strength of between

.

We conclude that the magnetic field of the southern shell has a strength of between

![]() G.

G.

3 Discussion

The radio properties of G65.2+5.7 show a number of similarities with another bilateral

SNR G156.2+5.7 (Reich et al. 1992; Xu et al. 2007), which also has the lowest surface brightness

of all known SNRs with a surface brightness of

![]()

![]() at l GHz. The surface brightness of G65.2+5.7 is about

at l GHz. The surface brightness of G65.2+5.7 is about

![]()

![]() ,

just about twice that of G156.2+5.7.

Both SNRs are located outside the Galactic plane and at

a similar distance of 800 pc or 1 kpc, although the shape of G65.2.+5.7 is more elliptical and

its size is about 50% larger, possibly indicating that it is a more evolved object. Both

are very bright in X-rays.

The symmetry axis of both objects shows a large inclination relative to the Galactic

plane, which has been taken as evidence that the ambient magnetic field has a similar inclination.

The WMAP 22.8 GHz polarization data at an angular resolution

of

,

just about twice that of G156.2+5.7.

Both SNRs are located outside the Galactic plane and at

a similar distance of 800 pc or 1 kpc, although the shape of G65.2.+5.7 is more elliptical and

its size is about 50% larger, possibly indicating that it is a more evolved object. Both

are very bright in X-rays.

The symmetry axis of both objects shows a large inclination relative to the Galactic

plane, which has been taken as evidence that the ambient magnetic field has a similar inclination.

The WMAP 22.8 GHz polarization data at an angular resolution

of

![]() in Fig. 7 indicate that the magnetic field is aligned almost parallel to the Galactic

plane up to about

in Fig. 7 indicate that the magnetic field is aligned almost parallel to the Galactic

plane up to about

![]() latitude. Above

latitude. Above

![]() latitude, the direction is less clearly defined.

Of course, the WMAP data show the integrated polarization along the line-of-sight and

local deviations in the magnetic field might be possible.

latitude, the direction is less clearly defined.

Of course, the WMAP data show the integrated polarization along the line-of-sight and

local deviations in the magnetic field might be possible.

Some differences between G65.2+5.7 and G156.2+5.7 exist in their

polarization properties. At ![]() 6 cm and

6 cm and ![]() 11 cm G156.2+5.7 has a higher fractional

polarization. Depolarization along the outer shell of G65.2+5.7 seems to

support the classification of a ``thermal composite'', based on X-ray

data, where a dense outer shell causes absorption of X-ray emission and

strong depolarization (Shelton et al. 2004).

11 cm G156.2+5.7 has a higher fractional

polarization. Depolarization along the outer shell of G65.2+5.7 seems to

support the classification of a ``thermal composite'', based on X-ray

data, where a dense outer shell causes absorption of X-ray emission and

strong depolarization (Shelton et al. 2004).

Orlando et al. (2007) presented simulations of the bilateral morphology of SNRs caused by density

gradients in the interstellar medium or a gradient in the ambient magnetic

field perpendicular to the radio shell. Smooth gradients are probably a simplification of

the true conditions. However, we note that the intensity differences between

the two arcs of the shell of G65.2+5.7

seem to agree with some of the simulations by Orlando et al. (2007, their Fig. 7, panels A and B),

in which quasi-parallel particle injection was assumed and the viewing angle was

perpendicular to both

![]() and the gradients of either density or

magnetic field strength. Slanting similar radio arcs were produced

if the gradient was perpendicular to

and the gradients of either density or

magnetic field strength. Slanting similar radio arcs were produced

if the gradient was perpendicular to

![]() .

In the quasi-perpendicular case, Orlando et al. (2007)

found a bilateral shape when the gradient of the ambient

.

In the quasi-perpendicular case, Orlando et al. (2007)

found a bilateral shape when the gradient of the ambient

![]() or density was parallel

to

or density was parallel

to

![]() .

The symmetry axis of the SNR is always aligned with the gradient of density or the magnetic field.

As indicated by the WMAP total intensity map (Fig. 7) or

.

The symmetry axis of the SNR is always aligned with the gradient of density or the magnetic field.

As indicated by the WMAP total intensity map (Fig. 7) or

![]() data (Fig. 13, right panel), thermal emission is evident

along the northern and southern shell, and more smooth in the north than in the south.

In addition to the general density gradient in the direction of Galactic latitude, this indicates a

density difference in the direction of longitude, which results in compression differences in the

interacting SNR shell and to a brightness difference as observed.

data (Fig. 13, right panel), thermal emission is evident

along the northern and southern shell, and more smooth in the north than in the south.

In addition to the general density gradient in the direction of Galactic latitude, this indicates a

density difference in the direction of longitude, which results in compression differences in the

interacting SNR shell and to a brightness difference as observed.

3.1 Analysis of HI-observations

Kalberla et al. (2005) published the Leiden/Argentina/Bonn (LAB) ![]() 21 cm survey of neutral hydrogen,

which covers the velocity range from

21 cm survey of neutral hydrogen,

which covers the velocity range from

![]() to

to

![]() with a velocity resolution of

with a velocity resolution of

![]() .

The HPBW of the survey was

.

The HPBW of the survey was

![]() ,

spectra were taken every

,

spectra were taken every

![]() and the rms brightness-temperature noise was about

and the rms brightness-temperature noise was about

![]() .

.

A fully sampled HI-survey was also carried out with the DRAO 26-m telescope by Higgs et al. (2005). We found no significant difference between these two surveys, except that the DRAO HI-survey does not cover the very northern part of the SNR. Our HI-mass calculation is thus based on the LAB survey.

We extracted the HI-data of the G65.2+5.7 region from the LAB survey data-cube in the velocity range

between

![]() and

and

![]() .

The 0.8 kpc distance corresponds to a velocity range

.

The 0.8 kpc distance corresponds to a velocity range

![]() according

to the Galactic rotation model given by Fich et al. (1989) of

according

to the Galactic rotation model given by Fich et al. (1989) of

![]() and

and

![]() .

Figure 10 displays the HI distribution after averaging five

consecutive channels (

.

Figure 10 displays the HI distribution after averaging five

consecutive channels (![]()

![]() )

within the velocity interval

from -20 to

)

within the velocity interval

from -20 to

![]() .

The central velocity of each image is indicated at the top.

Contours of

.

The central velocity of each image is indicated at the top.

Contours of ![]() 6 cm total intensity (smoothed to

6 cm total intensity (smoothed to

![]() )

are superimposed to indicate the region

of G65.2+5.7.

)

are superimposed to indicate the region

of G65.2+5.7.

Although HI-fluctuations are visible across the entire field,

we note signs of possible SNR interaction with the HI-gas in the images centered on

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

and

,

and

![]() .

The northern shell correlates with the lower velocity maps, while the southern shell correlates with

the

.

The northern shell correlates with the lower velocity maps, while the southern shell correlates with

the

![]() cloud. This may indicate that the northern shell is on the near side, or expands towards us,

while the southern shell is on the far side or expands away from us.

cloud. This may indicate that the northern shell is on the near side, or expands towards us,

while the southern shell is on the far side or expands away from us.

In Fig. 11,

we present the result for the integrated HI column densities over the velocity range -5 to

![]() .

We integrated HI column densities over the velocity range

.

We integrated HI column densities over the velocity range

![]() ,

and subtracted

the large-scale diffuse emission

using the ``unsharp-masking'' procedure described by Sofue & Reich (1979).

A weak HI shell with an angular diameter of about 4

,

and subtracted

the large-scale diffuse emission

using the ``unsharp-masking'' procedure described by Sofue & Reich (1979).

A weak HI shell with an angular diameter of about 4

![]() is visible at the outer periphery

of the radio continuum shell of SNR G65.2+5.7.

is visible at the outer periphery

of the radio continuum shell of SNR G65.2+5.7.

If a physical association exists, we would calculate the column density for the shell to be

![]() .

Assuming a thickness of the shell of 20% for

a 2

.

Assuming a thickness of the shell of 20% for

a 2

![]() radius,

this corresponds to a swept-up mass of about 1400

radius,

this corresponds to a swept-up mass of about 1400 ![]() .

The average density in the HI-shell is then about

.

The average density in the HI-shell is then about

![]() .

If this mass of neutral gas was originally uniformly distributed within a sphere of radius 2

.

If this mass of neutral gas was originally uniformly distributed within a sphere of radius 2

![]() ,

the pre-explosion ambient density would have been

,

the pre-explosion ambient density would have been

![]() ,

which is comparable to the value of

,

which is comparable to the value of

![]() estimated by Mason et al. (1979) for

the X-ray emitting region.

These densities are reasonable for a distance of

estimated by Mason et al. (1979) for

the X-ray emitting region.

These densities are reasonable for a distance of ![]() 80 pc away from the Galactic plane.

80 pc away from the Galactic plane.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=-90,width=8.8cm]{11706f11.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/33/aa11706-09/Timg153.png) |

Figure 11:

Integrated HI-intensities for the velocity range from

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

3.2 Comparison with observations from other bands

We show contours of ![]() 11 cm total intensities of G65.2+5.7 superposed on an

[O 3] emission image by Boumis et al. (2004) in Fig. 12.

The radio filaments are highly correlated with the

[O 3] filaments, which trace the fast SNR shock, except for the northwestern more diffuse part of the SNR.

In this area, the SNR shock front seems to be distorted resulting in a less compressed

magnetic field and a reduced efficiency in particle acceleration.

We note that in some regions enhanced radio filamentary emission is seen without any

corresponding optical emission. The magnetic fields might be stronger

and/or the temperatures/densities lower in these bright radio filaments.

This seems to be consistent with the measured incomplete cooling regions of G65.2+5.7 (Mavromatakis et al. 2002),

which means that at least parts of the SNR are still in an adiabatic phase.

11 cm total intensities of G65.2+5.7 superposed on an

[O 3] emission image by Boumis et al. (2004) in Fig. 12.

The radio filaments are highly correlated with the

[O 3] filaments, which trace the fast SNR shock, except for the northwestern more diffuse part of the SNR.

In this area, the SNR shock front seems to be distorted resulting in a less compressed

magnetic field and a reduced efficiency in particle acceleration.

We note that in some regions enhanced radio filamentary emission is seen without any

corresponding optical emission. The magnetic fields might be stronger

and/or the temperatures/densities lower in these bright radio filaments.

This seems to be consistent with the measured incomplete cooling regions of G65.2+5.7 (Mavromatakis et al. 2002),

which means that at least parts of the SNR are still in an adiabatic phase.

The G65.2+5.7 image (

![]() )

from the ROSAT

soft X-ray all-sky survey (Snowden et al. 1997) is shown in Fig. 13 (left panel)

with contours of

)

from the ROSAT

soft X-ray all-sky survey (Snowden et al. 1997) is shown in Fig. 13 (left panel)

with contours of ![]() 11 cm total intensity superimposed.

The radio contours trace the outer SNR shock and clearly define an outer

boundary of the X-ray emission. With its centrally filled X-ray thermal emission, G65.2+5.7

has been classified as a ``thermal composite'' SNR.

Shelton et al. (2004) reviewed the evolution of ``thermal composite'' SNRs: A dense

outer shell develops when the SNR enters the cooling phase, while the

strong centrally peaked thermal X-ray emission may be explained by

thermal conduction behind radiative shocks (Cox et al. 1999) and/or by the

evaporation of interstellar clumps (White & Long 1991).

More studies are needed to develop a detailed scenario of the evolution.

11 cm total intensity superimposed.

The radio contours trace the outer SNR shock and clearly define an outer

boundary of the X-ray emission. With its centrally filled X-ray thermal emission, G65.2+5.7

has been classified as a ``thermal composite'' SNR.

Shelton et al. (2004) reviewed the evolution of ``thermal composite'' SNRs: A dense

outer shell develops when the SNR enters the cooling phase, while the

strong centrally peaked thermal X-ray emission may be explained by

thermal conduction behind radiative shocks (Cox et al. 1999) and/or by the

evaporation of interstellar clumps (White & Long 1991).

More studies are needed to develop a detailed scenario of the evolution.

We show ![]() 11 cm contours

superposed on an

11 cm contours

superposed on an

![]() image of G65.2+5.7 (Finkbeiner 2003) in

Fig. 13 (right panel). A good correlation exists between the radio

structures and enhanced

image of G65.2+5.7 (Finkbeiner 2003) in

Fig. 13 (right panel). A good correlation exists between the radio

structures and enhanced

![]() emission, in particular along the southern shell.

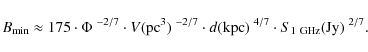

We estimate the thermal electron density within the southern shell using the

observed emission measure (EM); this is defined as the integral of the

square of electron density of the source along the line-of-sight l,

emission, in particular along the southern shell.

We estimate the thermal electron density within the southern shell using the

observed emission measure (EM); this is defined as the integral of the

square of electron density of the source along the line-of-sight l,

![]() l,

and related to the

l,

and related to the

![]() intensity by

intensity by

where EM is in units of pc cm-6,

Assuming an electron temperature of 10 000 K for the thermal gas and

given an

![]() intensity of 18 Rayleigh for the southern filament

by filtering out the diffuse emission,

we obtained an EM of about 145 pc cm-6 for a reddening E(B-V) of 0.44 (Schlegel et al. 1998).

We then obtained an electron density

intensity of 18 Rayleigh for the southern filament

by filtering out the diffuse emission,

we obtained an EM of about 145 pc cm-6 for a reddening E(B-V) of 0.44 (Schlegel et al. 1998).

We then obtained an electron density ![]() of between 38 cm-3 and 22 cm-3for a thickness of between 0.1 pc and 0.3 pc.

For the equipartition magnetic fields of

of between 38 cm-3 and 22 cm-3for a thickness of between 0.1 pc and 0.3 pc.

For the equipartition magnetic fields of ![]() G to

G to ![]() G (filling

factor 0.1), we may then

calculate RMs ranging between 70 rad m-2 and 245 rad m-2for the range of filament thicknesses and magnetic fields.

We recall that for the case of a tangential magnetic field, the

G (filling

factor 0.1), we may then

calculate RMs ranging between 70 rad m-2 and 245 rad m-2for the range of filament thicknesses and magnetic fields.

We recall that for the case of a tangential magnetic field, the ![]() 6 cm

polarization angles constraint is about RM

6 cm

polarization angles constraint is about RM

![]() .

.

![\begin{figure}

\includegraphics[width=8.8cm, angle=0]{11706f12.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/33/aa11706-09/Timg163.png) |

Figure 12:

Superposition of an [O 3] image (Boumis et al. 2004)

with |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\mbox{\includegraphics[angle=-90,width=8.8cm]{1170613a.ps}\includegraphics[angle=-90,width=8.8cm]{1170613b.ps} }\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/33/aa11706-09/Timg164.png) |

Figure 13:

Superimposed images of SNR G65.2+5.7.

Left: ROSAT X-ray emission (Snowden et al. 1997) (grey-scale) smoothed

to

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

We also investigated the distribution of CO-emission from the ``Composite CO-Survey'' (Dame et al. 1987) for the SNR region, but found no evidence of any associated emission.

4 Summary

We have presented high sensitivity maps of the SNR G65.2+5.7 for total and polarized

intensities at ![]() 6 cm and

6 cm and ![]() 11 cm. The spectral index

of the integrated flux densities was found to be

11 cm. The spectral index

of the integrated flux densities was found to be

![]() ,

which

is consistent with the value obtained by Reich et al. (1979).

The distribution of spectral indices shows some variation, although

within the error margins of the spectral index obtained for the integrated emission.

,

which

is consistent with the value obtained by Reich et al. (1979).

The distribution of spectral indices shows some variation, although

within the error margins of the spectral index obtained for the integrated emission.

Strong polarized emission is observed from the southern filament of G65.2+5.7, where a

high percentage polarization around 50% at ![]() 6 cm indicates the presence of a strong

regular magnetic field component.

Clear depolarization along its outer rim is seen at

6 cm indicates the presence of a strong

regular magnetic field component.

Clear depolarization along its outer rim is seen at ![]() 11 cm.

The polarized emission at

11 cm.

The polarized emission at ![]() 11 cm and

11 cm and

![]() 6 cm are affected by a different amount of depolarization as well as confusion from

diffuse Galactic polarized emission.

6 cm are affected by a different amount of depolarization as well as confusion from

diffuse Galactic polarized emission.

G65.2+5.7 is a faint large-diameter shell-type SNR with an exceptional low surface brightness in the radio range (Reich et al. 1979), but otherwise no unusual properties, e.g. no spectral bend as SNR S147 (Xiao et al. 2008). Except for possibly a few areas, G65.2+5.7 has almost entered the cooling phase. The strong depolarization along the outer SNR shell seems to support the classification of G65.2+5.7 as a rare example of a ``thermal composite'' SNR based on X-ray data.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. XiaoHui Sun for useful discussions and Dr. Patricia Reich for reading and comments on the manuscript. We are very grateful to the referee Dr. Tyler Foster for constructive comments, which clearly improved the manuscript. The

6 cm data were obtained with a receiver system from the MPIfR mounted at the Nanshan 25 m telesope at the Urumqi Observatory of NAOC. The nice receiver was constructed by Mr. Otmar Lochner of MPIfR, and well-maintained by Mr. M. Z. Chen and J. Ma of Urumqi observatory. The

11 cm observations are based on observations with the 100-m telescope of the MPIfR (Max-Planck-Institut für Radioastronomie) at Effelsberg. This research work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (10773016, 10833003 and 10821061), and the Partner group of the MPIfR at NAOC in the frame of the exchange program between MPG and CAS for a number of bilateral visits.

References

- Boumis, P., Meaburn, J., Lopez, J. A., et al. 2004, A&A, 424, 583 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] (In the text)

- Camilo, F., Nice, D. J., Shrauner, J. A., & Taylor, J. H. 1996, ApJ, 469, 819 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Condon, J. J., Cotton, W. D., Greisen, E. W., et al. 1998, AJ, 115, 1693 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Cordes, J. M., & Lazio, T. J. W. 2002, preprint [arXiv:astro-ph/0207156] (In the text)

- Cox, D. P., Shelton, R. L., Maciejewski, W., et al. 1999, ApJ, 524, 179 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Dame, T. M., Ungerechts, H., Cohen, R. S., et al. 1987, ApJ, 322, 706 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Emerson, D. T., & Gräve, R. 1988, A&A, 190, 353 [NASA ADS] (In the text)

- Fich, M., Blitz, L., & Stark, A. A. 1989, ApJ, 342, 272 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Finkbeiner, D. P. 2003, ApJS, 146, 407 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Foster, T. 2005, A&A, 441, 1043 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] (In the text)

- Fürst, E., & Reich, W. 2004, in The Magnetized Interstellar Medium, ed. B. Uyaniker, W. Reich, & R. Wielebinski, Copernicus GmbH, 141 (In the text)

- Gull, T. R., Kirshner, R. P., & Parker, R. A. R. 1977, ApJ, 215, L69 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Han, J. L., Manchester, R. N., Lyne, A. G., Qiao, G. J., & van Straten, W. 2006, ApJ, 642, 868 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Haslam, C. G. T., Wilson W. E., Graham, D. A., & Hunt, G. C. 1974, A&AS, 13, 359 [NASA ADS] (In the text)

- Higgs, L. A., Landecker, T. L., Asgekar, A., et al. 2005, AJ, 129, 2750 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Kalberla, P. M. W., Burton, W. B., Hartmann, D., et al. 2005, A&A, 440, 775 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] (In the text)

- Kovalenko, A. V., Pynzar, A. V., & Udal'Tsov, V. A. 1994, AZh, 71, 110 [NASA ADS] (In the text)

- Mason, K. O., Kahn, S. M., Charles, P. A., & Lampton, M. L. 1979, ApJ, 230, 163 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Mavromatakis, F., Boumis, P., Papamastorakis, J., & Ventura, J. 2002, A&A, 388, 355 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] (In the text)

- Orlando, S., Bocchino, F., Reale, F., Peres, G., & Petruk, O. 2007, A&A, 470, 927 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] (In the text)

- Page, L., Hinshaw, G., Komatsu, E., et al. 2007, ApJS, 170, 335 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Reich, P., & Reich, W. 1988, A&AS, 74, 7 [NASA ADS] (In the text)

- Reich, W. 2006, in Cosmic Polarization, ed. R. Fabbri, Research Signpost, 91 [arXiv:astro-ph/0603465] (In the text)

- Reich, W., Berkhuijsen, E. M., & Sofue, Y. 1979, A&A, 72, 270 [NASA ADS] (In the text)

- Reich, W., Reich, P., & Fürst, E. 1990, A&AS, 83, 539 [NASA ADS] (In the text)

- Reich, W., Fürst, E., & Arnal, E. M. 1992, A&A, 256, 214 [NASA ADS] (In the text)

- Reich, W., Fürst, E., Reich, P., et al. 2004, in The Magnetized Interstellar Medium, ed. B. Uyaniker, W. Reich, & R. Wielebinski, Copernicus GmbH, 57 (In the text)

- Schaudel, D., Becker, W., Lu, F., & Aschenbach, B. 2002, 34th COSPAR Scientific Assembly, Houston/USA, meeting abstract (In the text)

- Schlegel, D., Finkbeiner, D. P., & Davis, M. 1998, ApJ, 500, 525 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Shelton, R. L., Kuntz, K. D., & Petre, R. 2004, ApJ, 615, 275 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Snowden, S. L., Egger, R., Freyberg, M. J., et al. 1997, ApJ, 485, 125 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Sofue, Y., & Reich, W. 1979, A&AS, 38, 251 [NASA ADS] (In the text)

- Sun, X. H., Reich, W., Han, J. L., Reich, P., & Wielebinski, R. 2006, A&A, 447, 947 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Sun, X. H., Han, J. L., Reich, W., et al. 2007, A&A, 463, 993 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] (In the text)

- Turtle, A. Y., Pugh, G. F., Kenderdine, S., & Pauliny-Toth, I. I. K. 1962, MNRAS, 124, 297 [NASA ADS] (In the text)

- White, R. L., & Long, K. S. 1991, ApJ, 373, 543 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Wolleben, M., Landecker, T. L., Reich, W., & Wielebinski, R. 2006, A&A, 448, 411 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] (In the text)

- Xiao, L., Fürst, E., Reich, W., & Han, J. L. 2008, A&A, 482, 783 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] (In the text)

- Xu, J. W., Han, J. L., Sun, X. H., et al. 2007, A&A, 470, 969 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences]

Footnotes

- ... G65.2+5.7

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- Figures 1 and 2 (6 and 11 cm maps) are available in FITS format at the CDS via anonymous ftp to cdsarc.u-strasbg.fr (130.79.128.5) or via http://cdsweb.u-strasbg.fr/cgi-bin/qcat?J/A+A/503/827

All Tables

Table 1: Observational parameters

Table 2:

Bright sources in the area of SNR G65.2+5.7 fitted from the

Effelsberg ![]() 11 cm and Urumqi at

11 cm and Urumqi at ![]() 6 cm maps, including

source positions, flux densities from the NVSS at

6 cm maps, including

source positions, flux densities from the NVSS at ![]() 21 cm, as well as spectral indices. Sources

``outside'' G65.2+5.7 are listed for completeness.

21 cm, as well as spectral indices. Sources

``outside'' G65.2+5.7 are listed for completeness.

Table 3:

Integrated flux densities of G65.2+5.7, before (![]() )

and after (

)

and after (

![]() )

subtraction of point-like sources within the boundary of SNR.

)

subtraction of point-like sources within the boundary of SNR.

All Figures

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=-90,width=8.5cm]{11706f1a.ps}\par\includegraphics[angle=-90,width=8.5cm]{11706f1b.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/33/aa11706-09/Timg54.png) |

Figure 1:

The Urumqi |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=-90,width=8.5cm]{11706f2a.ps}\par\includegraphics[angle=-90,width=8.5cm]{11706f2b.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/33/aa11706-09/Timg55.png) |

Figure 2:

Same as Fig. 1, but for the Effelsberg |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm, angle=-90]{11706f3.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/33/aa11706-09/Timg58.png) |

Figure 3:

Effelsberg |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm, angle=-90]{11706f4.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/33/aa11706-09/Timg72.png) |

Figure 4:

Spectrum of the integrated radio flux densities of G65.2+5.7.

The spectral index is

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\mbox{\includegraphics[angle=-90,width=6cm]{11706f5a.ps}\incl...

...11706f5b.ps}\includegraphics[angle=-90,width=6cm]{11706f5c.ps} }

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/33/aa11706-09/Timg82.png) |

Figure 5:

T-T plots for different shell sections of G65.2+5.7 between

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=-90, width=8cm]{11706f6.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/33/aa11706-09/Timg84.png) |

Figure 6:

Spectral index map calculated between |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=-90,width=8.6cm]{11706f7.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/33/aa11706-09/Timg94.png) |

Figure 7:

The WMAP 22.8 GHz map.

The total intensity emission (grey-scale) map is smoothed to an angular resolution of

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=-90,width=8.6cm]{11706f8.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/33/aa11706-09/Timg97.png) |

Figure 8:

The |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=-90,width=8.5cm]{11706f9a.ps}\par\includegraphics[angle=-90,width=8.5cm]{11706f9b.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/33/aa11706-09/Timg104.png) |

Figure 9:

The observed polarized intensities in grey scales for the southern shell

at |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=18cm, angle=0]{11706f10.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/33/aa11706-09/Timg106.png) |

Figure 10:

The |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=-90,width=8.8cm]{11706f11.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/33/aa11706-09/Timg153.png) |

Figure 11:

Integrated HI-intensities for the velocity range from

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\includegraphics[width=8.8cm, angle=0]{11706f12.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/33/aa11706-09/Timg163.png) |

Figure 12:

Superposition of an [O 3] image (Boumis et al. 2004)

with |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}