| Issue |

A&A

Volume 503, Number 2, August IV 2009

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Page(s) | 505 - 509 | |

| Section | Stellar structure and evolution | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/200811342 | |

| Published online | 02 July 2009 | |

Hard X-ray flux from low-mass stars in the

Cygnus OB2 association

(Research Note)

M. Caramazza1,2 - J. J. Drake3 - G. Micela2 - E. Flaccomio2

1 - Dipartimento di Scienze Fisiche ed Astronomiche,

Università di Palermo, via Archirafi 36, 90123 Palermo, Italy

2 -

INAF Osservatorio Astronomico di Palermo, Piazza del Parlamento 1,

90134 Palermo, Italy

3 -

Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory, MS-3, 60 Garden Street,

Cambridge, MA 02138, USA

Received 13 November 2008 / Accepted 29 May 2009

Abstract

Context. The Cygnus OB2 association, the central engine of the Cygnus X star-forming region, is the subject of an extensive INTEGRAL Key Project that will accumulate 6Ms of observations. Analysis of 2Ms of observations by De Becker and co-workers provides the most sensitive limit yet obtained on hard X-ray emission from the cluster.

Aims. We investigate the X-ray emission in the 20-40 keV band expected from the flaring low-mass stellar population in Cygnus OB2. We discuss whether such emission needs to be considered in the interpretation of existing and future X-ray observations of the region, and whether such observations might provide insight into the high-energy processes on low-mass pre-main sequence stars.

Methods. The total hard X-ray flux from low-mass stars is estimated by assuming the observed soft X-ray emission stems from a superposition of flares. We further assume the ratio of hard X-ray to soft X-ray emission is described by a scaling found for solar flares by Isola and co-workers.

Results. We estimate the low-mass stellar hard X-ray flux in the 20-40 keV band to lie in the range

![]() and discuss some potential biases that might affect this result.

and discuss some potential biases that might affect this result.

Conclusions. Hard X-ray emission could lie at a level not much below the current observed flux upper limits for Cygnus OB2. If this emission could be detected, it would provide insight into the hard X-ray production of large flares on pre-main sequence stars. We highlight the penetrating power of hard X-rays from low-mass stellar populations as a possible pointer to our Galaxy's hidden star-forming clusters and super-clusters using more sensitive observations from future missions.

Key words: stars: coronae - stars: flare - Galaxy: open clusters and associations: individual: Cygnus OB2

1 Introduction

Motivated by the detection of nonthermal radio emission from early-type stars in the nearby massive Cygnus OB2 association (d=1.7 kpc, Massey & Thompson 1991), De Becker et al. (2007) have recently used an extensive set of observations obtained by the International Gamma-Ray Laboratory (INTEGRAL) IBIS instrument to search for hard X-ray emission from some of the more prominent radio sources. The nonthermal radio emission from these stars is thought to arise from a relativistic population of electrons accelerated by diffusive shock acceleration in their interacting stellar winds (e.g. Pittard & Dougherty 2006). De Becker et al. (2007) note that hard X-rays might plausibly be produced by inverse Compton scattering of photospheric UV photons.

One other potential source of hard X-rays in Cygnus OB2 are the myriad flares thought to arise from magnetic reconnection events that characterize and sustain the coronae of the low-mass stellar population (see, e.g., Albacete Colombo et al. 2007a; Caramazza et al. 2007). The flare paradigm developed from the solar perspective posits that hard X-rays can arise from the impact on dense photospheric gas of electrons accelerated to mildly relativistic energies (the ``thick-target model'', e.g. Hudson 1972; Lin & Hudson 1976; Brown 1971). Tentative direct evidence for such nonthermal hard X-rays up to 200 keV has recently been found from Swift observations of a large flare on the RS CVn-like interacting binary II Peg Osten et al. (2007). Large stellar flares observed on the young single star AB Dor and the active binaries Algol and UX Ari by the BeppoSAX mission (Boella et al. 1997) in the 0.1-100 keV range revealed evidence of similarly energetic emission, though it was not possible to ascertain whether this was of thermal or nonthermal origin (Franciosini et al. 2001; Maggio et al. 2000; Favata & Schmitt 1999).

While any single flare event on a low-mass star is a trifling insignificance in comparison with the effusive vigor of its high-mass brethren, the comparative multitude of the former population in Cygnus OB2 might render a palpable combined effect. An estimate of this effect is motivated from different standpoints.

Firstly, the search for hard X-rays from early-type stars by De Becker et al. (2007) resulted in only upper limits; an estimate of the flux limit at which low-mass stars might be detected could be important for understanding the origin of any hard X-rays detected in deeper observations by INTEGRAL or future missions.

Secondly, the large concentration of low-mass stars in the Cygnus OB2 region might also provide insight into the high-energy nature of stellar flares that is difficult to attain from observations of nearby single stars that rarely exhibit large events. Isola et al. (2007) have recently shown that a well-defined power-law relationship between soft and hard X-rays seen in solar flares matches the 20-40 keV flux observed during the AB Dor, Algol and UX Ari flares, but tends to overpredict the, presumed nonthermal, 60-80 keV flux. Alexander & Daou (2007) find evidence for a saturation in nonthermal X-ray flux above 20 keV for solar flares with increasing soft X-ray luminosity, and it is conceivable that this is related to the deficit in observed nonthermal stellar X-rays. Detection of, or limits on, the hard X-ray flux from the low-mass Cygnus OB2 population could provide constraints for extrapolating solar flare models to much more active pre-main sequence stars.

Thirdly, the hard X-ray environment of young protostellar systems is potentially relevant for the ionization of circumstellar material and protoplanetary disks (e.g. Glassgold et al. 1997; Fromang et al. 2002; Aikawa & Herbst 1999; Matsumura & Pudritz 2003). We currently have no information on the intensity of this radiation environment.

We outline in Sect. 2 below a calculation of the hard X-ray flux from the Cygnus OB2 low-mass population under the assumption that the observed soft X-rays from these stars is dominated by a superposition of flaring events. We then discuss in Sect. 3 the uncertainties in this estimate, the degree to which it likely overestimates the true level of hard X-ray emission, and the implications of the results.

2 Estimating the low-mass stellar hard X-ray flux

There are three main components to our hard X-ray flux estimate: the Cygnus OB2 initial mass function (IMF) and total stellar mass; the relationship between stellar mass and observed soft X-ray luminosity for the low-mass population; and the relationship between the soft and hard X-ray luminosities. In order to gain a better perspective on the uncertainties involved in our estimate, we use three different approaches that employ these ingredients in slightly different ways.

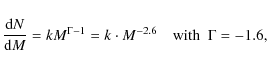

We adopt the IMF derived by Knödlseder (2000) based on 2MASS

photometry. That study noted the power-law index found,

![]() ,

is compatible with that of Kroupa et al. (1993)

for the solar neighborhood, but is significantly steeper than found

from spectroscopy of the central region of Cygnus OB2 by

Massey & Thompson (1991). We therefore also investigate below the

effect of a different power-law slope, and in particular that found

for the Orion Nebula Cluster (ONC,

,

is compatible with that of Kroupa et al. (1993)

for the solar neighborhood, but is significantly steeper than found

from spectroscopy of the central region of Cygnus OB2 by

Massey & Thompson (1991). We therefore also investigate below the

effect of a different power-law slope, and in particular that found

for the Orion Nebula Cluster (ONC,

![]() )

by

Muench et al. (2002). We

consider hard X-rays from stars in the mass range

)

by

Muench et al. (2002). We

consider hard X-rays from stars in the mass range

![]() ;

the

upper limit corresponds to the approximate boundary between low-mass

pre-main sequence stars with outer convection zones and intermediate

mass stars that should have radiative envelopes; the lower mass limit

corresponds to the limit of the Knödlseder (2000)

study - essentially our limit of current knowledge. For stars with

mass

;

the

upper limit corresponds to the approximate boundary between low-mass

pre-main sequence stars with outer convection zones and intermediate

mass stars that should have radiative envelopes; the lower mass limit

corresponds to the limit of the Knödlseder (2000)

study - essentially our limit of current knowledge. For stars with

mass

![]() ,

X-ray luminosities of T Tauri stars are observed to

decline much more rapidly with decreasing mass than for higher mass stars

(e.g. Albacete Colombo et al. 2007b; Preibisch et al. 2005), rendering

their contribution to the total X-ray luminosity less significant,

regardless of whether the IMF flattens toward lower masses or not

(e.g. Chabrier 2003; Kroupa et al. 1993; Kroupa 2001; Scalo 1986).

Nevertheless, we also investigate the effects of this lower mass

cut-off in our calculations below.

,

X-ray luminosities of T Tauri stars are observed to

decline much more rapidly with decreasing mass than for higher mass stars

(e.g. Albacete Colombo et al. 2007b; Preibisch et al. 2005), rendering

their contribution to the total X-ray luminosity less significant,

regardless of whether the IMF flattens toward lower masses or not

(e.g. Chabrier 2003; Kroupa et al. 1993; Kroupa 2001; Scalo 1986).

Nevertheless, we also investigate the effects of this lower mass

cut-off in our calculations below.

Albacete Colombo et al. (2007a) found the X-ray luminosities of

low-mass stars in Cygnus OB2 to be essentially identical to those in

the ONC (Preibisch et al. 2005). We therefore adopt the relation between

stellar mass,

M, and X-ray luminosity, ![]() ,

from the ONC study. In order to examine the

effects on our

calculation of the significant scatter in observed

,

from the ONC study. In order to examine the

effects on our

calculation of the significant scatter in observed ![]() vs. M, we also

calculate

the expected hard X-ray flux using the observed ONC stellar sample

renormalized to the Cygnus OB2 low-mass content (see Sect. 2.3).

vs. M, we also

calculate

the expected hard X-ray flux using the observed ONC stellar sample

renormalized to the Cygnus OB2 low-mass content (see Sect. 2.3).

The relationship between the soft and hard X-ray luminosities was

derived using the extrapolation of the relation found for solar flares

by Isola et al. (2007),

![]() ,

where

F20-40 is the 20-40 keV flux density in ph cm-2 keV-1 s-1and

,

where

F20-40 is the 20-40 keV flux density in ph cm-2 keV-1 s-1and ![]() is

the Geostationary Operational Environment Satellite (GOES)

1.6-12.4 keV flux in unit of W m-2. In order to convert this relation to

the stellar

case, we assumed that the observed soft X-ray luminosities of the

Cygnus OB2 low-mass pre-main sequence population could be explained by

a superposition of flares. This assumption is based on evidence that

the solar corona is largely characterized by a power-law flare

distribution in total energy, E, and frequency, N,

is

the Geostationary Operational Environment Satellite (GOES)

1.6-12.4 keV flux in unit of W m-2. In order to convert this relation to

the stellar

case, we assumed that the observed soft X-ray luminosities of the

Cygnus OB2 low-mass pre-main sequence population could be explained by

a superposition of flares. This assumption is based on evidence that

the solar corona is largely characterized by a power-law flare

distribution in total energy, E, and frequency, N,

![]() (e.g. Lin et al. 1984; Krucker & Benz 1998; Hudson 1991),

and on studies of EUV and X-ray flares and photon arrival times for

active stars that suggest a similar flare distribution with

(e.g. Lin et al. 1984; Krucker & Benz 1998; Hudson 1991),

and on studies of EUV and X-ray flares and photon arrival times for

active stars that suggest a similar flare distribution with

![]() (Kashyap et al. 2002; Audard et al. 2000; Güdel et al. 2003). The

high-energy tails of flares detected in Chandra studies of the

ONC and Cygnus OB2 are also well-approximated by a power-law frequency

distribution with

(Kashyap et al. 2002; Audard et al. 2000; Güdel et al. 2003). The

high-energy tails of flares detected in Chandra studies of the

ONC and Cygnus OB2 are also well-approximated by a power-law frequency

distribution with

![]() (ONC, Caramazza et al. 2007),

(ONC, Caramazza et al. 2007),

![]() (Cygnus OB2, Albacete Colombo et al. 2007a).

In the following we outline our estimates, and then discuss the uncertainties of

this approach. An alternative approach to estimate the nonthermal emission

is proposed in (Güdel 2009).

(Cygnus OB2, Albacete Colombo et al. 2007a).

In the following we outline our estimates, and then discuss the uncertainties of

this approach. An alternative approach to estimate the nonthermal emission

is proposed in (Güdel 2009).

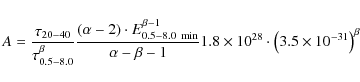

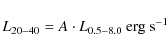

2.1 Hard-soft X-ray luminosity relation for young low-mass stars

The relation from Isola et al. (2007) relates the flux in the 1.6-12.4 keV band to the flux density in the 20-40 keV band. In order to obtain a relation between the peak luminosity of flares in the two bands, we first converted the GOES flux from W m-2 into erg s-1 luminosity, and the flux density in the hard band, given in unit of ph cm-2 keV-1 s-1, into erg s-1 luminosity, assuming a photon energy of 20 keV and multiplying for the band range. We also converted the 1.6-12.4 keV luminosity into luminosity in the 0.5-8.0 keV band: the conversion factor (where

This relation can be converted in a relation between the total energy output of

flares in the two spectral bands, considering that

![]() .

Given the power-law distribution of flare energies in the 0.5-8.0 keV

band, we conclude that the 20-40 keV band flare energies are also distributed

as a power-law. The index of this

power-law,

.

Given the power-law distribution of flare energies in the 0.5-8.0 keV

band, we conclude that the 20-40 keV band flare energies are also distributed

as a power-law. The index of this

power-law, ![]() ,

is a function of

,

is a function of ![]() and

and ![]() :

:

![]() ,

where

,

where

![]() (Caramazza et al. 2007) and

(Caramazza et al. 2007) and

![]() (Isola et al. 2007).

If we impose the condition that

(Isola et al. 2007).

If we impose the condition that

![]() also has a value greater than 2, i.e. that the 20-40 keV

band emission is due entirely to flares, then the acceptable values

for

also has a value greater than 2, i.e. that the 20-40 keV

band emission is due entirely to flares, then the acceptable values

for ![]() and

and ![]() fall in the ranges

fall in the ranges

![]() and

and

![]() .

Integrating the distribution of flares between the

minimum energy and the

maximum energy, that we can set as infinite, we obtain the following

relation between stellar luminosity in the 20-40 keV and 0.5-8.0 keV

bands:

.

Integrating the distribution of flares between the

minimum energy and the

maximum energy, that we can set as infinite, we obtain the following

relation between stellar luminosity in the 20-40 keV and 0.5-8.0 keV

bands:

where

|

(3) |

here, we set

2.2 Analytical estimate

Adopting the relation between stellar mass and the X-ray luminosity

found for the Chandra Orion Ultra-deep Project (COUP) stars in

the range

![]() (Preibisch et al. 2005),

(Preibisch et al. 2005),

and combining this with Eq. (2), we obtain a relation between stellar mass and hard X-ray flux. This expression can then be integrated over the stellar mass distribution for Cygnus OB2. The IMF found by Knödlseder (2000) follows the standard form

and assuming for the present a total mass of

In order to calculate the total hard X-ray luminosity in the cluster,

we transform the IMF into a function of 20-40 keV stellar X-ray

luminosity, and integrate between the luminosities corresponding to

0.3 and

![]() ,

obtaining values in the following range:

,

obtaining values in the following range:

2.3 Scaling the Orion hard X-ray luminosity

We can also make a rough estimate of hard X-ray flux from Cygnus OB2

by scaling directly the observed X-ray luminosity distribution of the

low-mass stars in Orion. This approach has the advantage that the

observed scatter in the COUP sample is intrinsically included. The

IMF of the Orion sample has a shallower slope than that for Cygnus OB2

of Knödlseder (2000), with

![]() (Muench et al. 2002), and we

investigate the influence of this difference in Sect. 2.4

below.

(Muench et al. 2002), and we

investigate the influence of this difference in Sect. 2.4

below.

The total 20-40 keV luminosity for the COUP sample is

simply the sum over all stars of mass Mi in the range

![]() ,

,

![\begin{displaymath}L_{20-40}^{\rm COUP}=A \cdot \sum_{M_i=0.3}^{2}L_{0.5-8.0}(i)=

[8.6\times 10^{28},~3.1\times 10^{30}] \ \rm erg \ s^{-1},

\end{displaymath}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/32/aa11342-08/img48.png)

where the relation between the 20-40 keV and 0.5-8 keV luminosities is given by Eq. (2). Assuming a similar IMF for both Orion and Cygnus OB2, the hard X-ray luminosity of the latter is then simply given by the product of

![\begin{displaymath}L_{20-40}^{\rm Cyg}=[1.7\times 10^{31},~6.3\times 10^{32}] ~\rm erg \ s^{-1}

.\end{displaymath}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/32/aa11342-08/img52.png)

2.4 Simulating Cygnus OB2 using the Orion sample

In order to account for the different IMF slopes in Cygnus OB2 and

Orion (

![]() cf. -1.2), we also performed a simple Monte

Carlo simulation of 10 000 stars. The mass range

cf. -1.2), we also performed a simple Monte

Carlo simulation of 10 000 stars. The mass range

![]() was divided into 10 bins, and within each mass bin 0.5-8.0 keV

luminosities were randomly selected from those observed in the COUP

sample. The number of ``stars'' drawn in each bin was weighted

according to the Cygnus OB2 IMF from Eq. (5), and the

luminosity for each star was scaled to L20-40 as described

earlier. The luminosity of the simulated sample was then scaled so as

to have a total mass equal to that of Cygnus OB2 for the

was divided into 10 bins, and within each mass bin 0.5-8.0 keV

luminosities were randomly selected from those observed in the COUP

sample. The number of ``stars'' drawn in each bin was weighted

according to the Cygnus OB2 IMF from Eq. (5), and the

luminosity for each star was scaled to L20-40 as described

earlier. The luminosity of the simulated sample was then scaled so as

to have a total mass equal to that of Cygnus OB2 for the

![]() mass range. In this way, we estimate

mass range. In this way, we estimate

![\begin{displaymath}L_{20-40}^{\rm Cyg}=[1.9\times 10^{31},~6.6\times 10^{32}] ~\rm erg \ s^{-1}.

\end{displaymath}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/32/aa11342-08/img54.png)

As a verification of the calculation, we recovered a luminosity of

![]() - essentially the

same as that found from direct calculation in Sect. 2.3 - for

an IMF with slope

- essentially the

same as that found from direct calculation in Sect. 2.3 - for

an IMF with slope

![]() scaled to the appropriate COUP total

mass.

scaled to the appropriate COUP total

mass.

3 Discussion

The range of 20-40 keV fluxes we have evaluated above can be compared with the the

The 20-40 keV bandpass considered here is significantly narrower that

the 20-60 keV range cited by De Becker et al. (2007). Based on the

power-law spectrum and slope estimate by Isola et al. (2007), we

expect the corresponding estimate for the 20-60 keV range to be a

factor 1.8 higher. Moreover, the upper limit of the fluxes for the

undetected stars was estimated by De Becker et al. (2007) within a

PSF of

![]() .

Using the King profile describing the projected spatial

distribution of starlight from the association

found by Knödlseder (2000), the ratio between the flux in the

whole association area (radius

.

Using the King profile describing the projected spatial

distribution of starlight from the association

found by Knödlseder (2000), the ratio between the flux in the

whole association area (radius

![]() )

to that in the

3EG J20033+4188 region is 6.6. Applying these scaling factors, the

total luminosity in the whole region of Cygnus should not be higher

than

)

to that in the

3EG J20033+4188 region is 6.6. Applying these scaling factors, the

total luminosity in the whole region of Cygnus should not be higher

than

![]() erg s-1. While this scaling is somewhat

crude, the range of 20-40 keV fluxes we have evaluated is one order of

magnitude lower than this upper limit. This confirms the potential importance

of hard X-ray emission from the low-mass stars in stellar clusters.

erg s-1. While this scaling is somewhat

crude, the range of 20-40 keV fluxes we have evaluated is one order of

magnitude lower than this upper limit. This confirms the potential importance

of hard X-ray emission from the low-mass stars in stellar clusters.

There are several assumptions that might have led us to overestimate the

Cygnus OB2 luminosity. First, the total

cluster mass of

![]() derived by

Knödlseder (2000) has been challenged by Hanson (2003), who

estimated the cluster to lie slightly closer at 1.4 kpc and suggested

a total cluster mass closer to

derived by

Knödlseder (2000) has been challenged by Hanson (2003), who

estimated the cluster to lie slightly closer at 1.4 kpc and suggested

a total cluster mass closer to

![]() .

Nevertheless, based on

a study of A-stars in the Cygnus OB2 field, Drew et al. (2008) find

that ``a total mass of

.

Nevertheless, based on

a study of A-stars in the Cygnus OB2 field, Drew et al. (2008) find

that ``a total mass of

![]() would not be

surprising''. Our adopted

would not be

surprising''. Our adopted

![]() is then perhaps up to

1.2-1.7 times too high.

is then perhaps up to

1.2-1.7 times too high.

We have also assumed that all of the observed stellar X-ray flux is due to continuous flaring. Some fraction of the observed luminosity of these stars might also be attributed to a quiescent component.

One additional factor of uncertainty is related to the duration of flares.

Indeed, the hard X-rays seen in solar

flares that are usually associated with the flare impulsive phase

generally decay on a more rapid timescale than soft X-rays

(e.g. Benz 2008; Dennis & Zarro 1993, and references therein). We considered a

ratio between the duration of flares in hard and soft band derived from solar

measures of flare duration (Veronig et al. 2002).The case of large stellar

flares is not so clear, however. The decay of the 14-40 keV flux in

the large II Peg flare observed by Swift was not obviously

shorter than that for the soft X-rays. It should also be noted that

in large stellar flares there will be a larger thermal contribution in

the 20-40 keV range than in much less energetic solar flares, in

alignment with the general correlation of increasing plasma

temperature with flare total energy (e.g. Feldman et al. 1995). Moreover,

also the minimum energy of the distribution of flares is uncertain, we set it to

the median value obtained from the analysis of the COUP low mass samples. In our

estimation we considered that it can be uncertain of two orders of magnitude,

that

implies a variation of a factor ![]() 5 in the resulting total energy: note,

however, that Güdel (2009) found a value even lower (few times 1030).

5 in the resulting total energy: note,

however, that Güdel (2009) found a value even lower (few times 1030).

Our assumptions could lead to an overestimation of the real value of

the total luminosity, but a value of

![]() ,

an

order of magnitude below the De Becker et al. (2007) flux upper

limit, would render the low-mass population of importance in searches

for emission from specific suspected sources of hard X-rays, such as

the unidentified

,

an

order of magnitude below the De Becker et al. (2007) flux upper

limit, would render the low-mass population of importance in searches

for emission from specific suspected sources of hard X-rays, such as

the unidentified ![]() -ray source 3EG 2033+4118, the unidentified

TeV source TeV J2032+4130, and massive colliding-wind binaries.

-ray source 3EG 2033+4118, the unidentified

TeV source TeV J2032+4130, and massive colliding-wind binaries.

The possibility of detecting hard X-ray emission from nearby clustered low-mass pre-main sequence populations provides a promising means of investigating high-energy processes on stars that are generally too distant to study in detail individually. Of particular interest is the relation between soft and hard X-ray emission of solar flares (e.g. Isola et al. 2007; Battaglia et al. 2005), and how the underlying physical basis can be extrapolated to the other regimes, such as the pre-main sequence stellar case where hard X-rays from flares can be important agents of protoplanetary disk ionisation (e.g. Igea & Glassgold 1999; Glassgold et al. 2004).

Our discussion assumes that all stars will be ``observed'' in the

20-40 keV range, i.e., that X-rays will penetrate both the

circumstellar and ambient cluster and line-of-sight extinction.

Cygnus OB2 is located behind the Great Cygnus Rift that leads to

extinction of up to (and possibly beyond)

![]() (e.g. Massey & Thompson 1991). Extinction of 10m corresponds

to a neutral hydrogen column density

(e.g. Massey & Thompson 1991). Extinction of 10m corresponds

to a neutral hydrogen column density

![]() .

The optical depth for such a column for 20-40 keV X-rays

is completely negligible; the Compton ionization and scattering

cross-section of

.

The optical depth for such a column for 20-40 keV X-rays

is completely negligible; the Compton ionization and scattering

cross-section of

![]() renders the

interstellar medium optically thin to hard X-rays for columns up to

renders the

interstellar medium optically thin to hard X-rays for columns up to

![]() .

Except perhaps in rare cases of stars

obscured by very dense circumstellar disk mid-plane gas and dust, the

assumption that we will see the whole cluster in hard X-rays should be

valid.

.

Except perhaps in rare cases of stars

obscured by very dense circumstellar disk mid-plane gas and dust, the

assumption that we will see the whole cluster in hard X-rays should be

valid.

Finally, this consideration raises the possibility of using the

penetrating power of hard X-rays as a pointer to our Galaxy's hidden

superclusters. Hanson (2003) noted that extrapolation of the

locally-derived Galactic cluster luminosity function indicates that

our Galaxy hosts ``tens to perhaps a hundred'' massive clusters with

total mass

![]() .

These clusters are likely hidden

behind many magnitudes of extinction and will not be easy to locate.

Hard X-rays can penetrate such extinction, and the arrival of missions

in the next decade able to provide relatively precise imaging with

much greater sensitivity in the

.

These clusters are likely hidden

behind many magnitudes of extinction and will not be easy to locate.

Hard X-rays can penetrate such extinction, and the arrival of missions

in the next decade able to provide relatively precise imaging with

much greater sensitivity in the

![]() keV bandpass, such as

NuSTAR (Harrison et al. 2005) and Symbol-X

(Pareschi & Ferrando 2005), could provide an assay of this hitherto

much overlooked population of our Galaxy. In this context, Cygnus OB2

represents a potential ``Rosetta Stone'', offering a nearby

super-cluster example that can be well-characterized using

multi-wavelength techniques that will not be applicable to more

distant and extinguished clusters.

keV bandpass, such as

NuSTAR (Harrison et al. 2005) and Symbol-X

(Pareschi & Ferrando 2005), could provide an assay of this hitherto

much overlooked population of our Galaxy. In this context, Cygnus OB2

represents a potential ``Rosetta Stone'', offering a nearby

super-cluster example that can be well-characterized using

multi-wavelength techniques that will not be applicable to more

distant and extinguished clusters.

Acknowledgements

J.J.D. was funded by NASA contract NAS8-39073 to the Chandra X-ray Center (CXC) during the course of this research and thanks the CXC director, Harvey Tananbaum, and the CXC science team for advice and support. J.J.D. also thanks the ISHERPA program for financial support during his visit to the Osservatorio Astronomico di Palermo, and the Osservatorio director, Prof. S. Sciortino, and staff for their help and warm hospitality. M.C., G.M. and E.F. acknowledge financial support from the Ministero dell'Università e della Ricerca and ASI/INAF Contract I/023/05/0. J.J.D. thanks Jürgen Knödlseder for useful discussions that partly inspired this work.

The authors thank the referee Manuel Güdel for suggestions and useful comments that improved this work.

References

- Aikawa, Y., & Herbst, E. 1999, A&A, 351, 233 [NASA ADS]

- Albacete Colombo, J. F., Caramazza, M., Flaccomio, E., Micela, G., & Sciortino, S. 2007a, A&A, 474, 495 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences]

- Albacete Colombo, J. F., Flaccomio, E., Micela, G., Sciortino, S., & Damiani, F. 2007b, A&A, 464, 211 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences]

- Alexander, D., & Daou, A. G. 2007, ApJ, 666, 1268 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Audard, M., Güdel, M., Drake, J. J., & Kashyap, V. L. 2000, ApJ, 541, 396 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Battaglia, M., Grigis, P. C., & Benz, A. O. 2005, A&A, 439, 737 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences]

- Benz, A. O. 2008, Living Reviews in Solar Physics, 5, 1 [NASA ADS]

- Boella, G., Butler, R. C., Perola, G. C., et al. 1997, A&AS, 122, 299 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] (In the text)

- Brown, J. C. 1971, Sol. Phys., 18, 489 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Caramazza, M., Flaccomio, E., Micela, G., et al. 2007, A&A, 471, 645 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences]

- Chabrier, G. 2003, PASP, 115, 763 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- De Becker, M., Rauw, G., Pittard, J. M., et al. 2007, A&A, 472, 905 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] (In the text)

- Dennis, B. R., & Zarro, D. M. 1993, Sol. Phys., 146, 177 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Drew, J. E., Greimel, R., Irwin, M. J., & Sale, S. E. 2008, MNRAS, 521 (In the text)

- Favata, F., & Schmitt, J. H. M. M. 1999, A&A, 350, 900 [NASA ADS]

- Feldman, U., Laming, J. M., & Doschek, G. A. 1995, ApJ, 451, L79 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Franciosini, E., Pallavicini, R., & Tagliaferri, G. 2001, A&A, 375, 196 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences]

- Fromang, S., Terquem, C., & Balbus, S. A. 2002, MNRAS, 329, 18 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Glassgold, A. E., Najita, J., & Igea, J. 1997, ApJ, 480, 344 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Glassgold, A. E., Najita, J., & Igea, J. 2004, ApJ, 615, 972 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Güdel, M. 2009, ArXiv e-prints (In the text)

- Güdel, M., Audard, M., Kashyap, V. L., Drake, J. J., & Guinan, E. F. 2003, ApJ, 582, 423 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, M. M. 2003, ApJ, 597, 957 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Harrison, F. A., Christensen, F. E., Craig, W., et al. 2005, Exper. Astron., 20, 131 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Hudson, H. S. 1972, Sol. Phys., 24, 414 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, H. S. 1991, Sol. Phys., 133, 357 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Igea, J., & Glassgold, A. E. 1999, ApJ, 518, 848 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Isola, C., Favata, F., Micela, G., & Hudson, H. S. 2007, A&A, 472, 261 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] (In the text)

- Kashyap, V. L., Drake, J. J., Güdel, M., & Audard, M. 2002, ApJ, 580, 1118 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Knödlseder, J. 2000, A&A, 360, 539 [NASA ADS] (In the text)

- Kroupa, P. 2001, MNRAS, 322, 231 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Kroupa, P., Tout, C. A., & Gilmore, G. 1993, MNRAS, 262, 545 [NASA ADS] (In the text)

- Krucker, S., & Benz, A. O. 1998, ApJ, 501, L213 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Lin, R. P., & Hudson, H. S. 1976, Sol. Phys., 50, 153 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Lin, R. P., Schwartz, R. A., Kane, S. R., Pelling, R. M., & Hurley, K. C. 1984, ApJ, 283, 421 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Maggio, A., Pallavicini, R., Reale, F., & Tagliaferri, G. 2000, A&A, 356, 627 [NASA ADS]

- Massey, P., & Thompson, A. B. 1991, AJ, 101, 1408 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Matsumura, S., & Pudritz, R. E. 2003, ApJ, 598, 645 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Muench, A. A., Lada, E. A., Lada, C. J., & Alves, J. 2002, ApJ, 573, 366 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Osten, R. A., Drake, S., Tueller, J., et al. 2007, ApJ, 654, 1052 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Pareschi, G., & Ferrando, P. 2005, Exper. Astron., 20, 139 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Pittard, J. M., & Dougherty, S. M. 2006, MNRAS, 372, 801 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Preibisch, T., Kim, Y.-C., Favata, F., et al. 2005, ApJS, 160, 401 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Scalo, J. M. 1986, Fund. Cosmic Phys., 11, 1 [NASA ADS]

- Veronig, A., Vrsnak, B., Dennis, B. R., et al. 2002, A&A, 392, 699 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] (In the text)

Footnotes

- ...

Cygnus OB2

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- The distance between the position of

3EG J20033+4188 and the center of Cyg OB2 obtained by

(Knödlseder 2000) is

.

.

Copyright ESO 2009

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.

![\begin{displaymath}

L_{20-40}^{\rm Cyg}=[1.8 \times 10^{31},~6.6 \times 10^{32}]~\rm erg \ s^{-1}.

\end{displaymath}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/32/aa11342-08/img47.png)