| Issue |

A&A

Volume 503, Number 1, August III 2009

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Page(s) | L1 - L4 | |

| Section | Letters | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/200811520 | |

| Published online | 04 June 2009 | |

LETTER TO THE EDITOR

Testing the Newton second law in the regime of small accelerations

V. A. De Lorenci1,2 - M. Faúndez-Abans3 - J. P. Pereira1

1 - Instituto de Ciências Exatas, Universidade Federal de Itajubá, Av. BPS 1303 Pinheirinho, 37500-903 Itajubá, MG, Brazil

2 - PH Department, TH Unit, CERN, 1211 Geneva 23, Switzerland

3 - Laboratório Nacional de Astrofísica, Rua Estados Unidos 154, Bairro das Nações, 37504-364 Itajubá, MG, Brazil

Received 12 December 2008 / Accepted 16 May 2009

Abstract

It has been pointed out that the Newtonian second law can be tested in the very small acceleration regime by using the combined movement of the Earth and Sun around the Galactic center of mass. It has been shown that there are only two brief intervals during the year in which the experiment can be completed, which correspond to only two specific spots on the Earth surface. An alternative experimental setup is presented to allow the measurement to be made on Earth at any location and at any time.

Key words: gravitation - Galaxy: kinematics and dynamics

1 Introduction

As is observationally known (Rubin 1983a,b; Cowsik & Ghosh 1986; Famaey et al. 2007; and Gentile et al. 2007), the rotation curve of galactic mass distribution cannot be interpreted in terms of Newtonian classical dynamics. Far mass seems to exist than directly inferred for luminous mass, which consists of stars, planets, dust, gas, and molecular clouds. To solve this theoretically unexpected result two possible scenarios have been examined in the literature. The first, which has been widely accepted, consists of postulating the existence of a fundamentally different kind of matter: the so-called dark matter. This type of matter is expected to interact with ordinary matter only gravitationally. Thus, it should not be directly detected by modern telescopes since it should not emit any radiation. Experiments continue to be performed to detect dark matter. One possible explanation of dark matter involves an extension of the standard model of particle physics to include weakly interacting massive particles (WIMPs). If dark matter exists, it is expected to be produced by the LHC experiment at CERN, which should take place imminently, or inside future high-energy colliders (Baltz et al. 2006). Accretion of dark matter onto a central black hole at the Galactic center may lead a density spike in the dark matter distribution, which would result in a high dark matter annihilation rate with observational consequences (Ullio et al. 2001). In the context of cold dark matter (CDM) cosmological models, structures are generated hierarchically and local dark matter distribution depends on the fate of the first WIMP micro-halos to form. The evolution of these micro-halos is being considered and may hold the key to dark matter detections (Angus & Zhao 2007; Green 2007, and references therein). Results based on the weak lensing observations of the so-called Bullet Cluster (1E0657-588, z = 0.296) were claimed to represent empirical proof of the existence of dark matter (Clowe et al. 2006). However, a possible conflicting behavior measured in a similar merging system was pointed out in Mahdavi et al. (2007). Penny et al. (2009), analyzed observations by the high-resolution Hubble Space Telescope Advanced Camera for Surveys, that is WFS imaging in the F555W and F814W bands of five fields about the core of the Perseus cluster of galaxies, and proposed that a large proportion of dark matter could explain the absence of tidal disruption in the core dwarf galaxies.

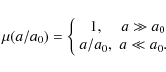

The second possible scenario for explaining the apparent mass discrepancies inside galaxies consists of a modification to the Newtonian dynamics in the limit of low accelerations (Milgrom 1983a,b). The main assumption of this proposed Modified Newtonian Dynamics (MOND) is that the well-established classical second law of dynamics would change to the form

where a0 is a new physical constant with the dimension of acceleration and the function

Following Milgrom (1983a,b) and Bekenstein & Milgrom (1984), two possible approaches could be considered in this scenario. The first refers to a modification to the gravity sector that does not change Newton's second law, and would imply changing the gravitational force from

Phenomenologically, MOND is able to fit rotation curve data of observed spiral galaxies based only on the observed baryonic mass distribution (see Sanders & McGaugh 2002, and references therein). Furthermore, it was shown that the results of the Bullet Cluster measurements are consistent with MOND dynamics of single clusters (Angus et al. 2007). Numerical simulations with MOND were produced by Tiret & Combes (2007) by taking into account gas dissipation and star formation. Their results show that MOND implies longer merger times, which solve the problem of the apparent excess of compact groups of galaxies observed today. In addition, galaxies in MOND are found to form stronger bars, and more rapidly than in Newtonian dynamics with dark matter (Tiret & Combes 2007). In a dissipationless evolution of a MOND-dominated region in an expanding Universe, Sanders (2008) demonstrated that the final virialized objects resemble elliptical galaxies with clearly defined relationships between mass, radius, and velocity dispersion. Zhao et al. (2008) studied the properties of galaxies formed in the Tensor Vector Scalar (TeVeS) framework (Bekenstein 2004) with analytical modeling and hydrodynamical simulations, comparing them with those in a ![]() CDM framework in the context of the formation of both high surface brightness bulges and elliptical galaxies. As a result, they found that the use of a MOND scalar field produces tight correlations in galaxy properties because in this model the effective halo is not as scattered and free as in CDM ones.

CDM framework in the context of the formation of both high surface brightness bulges and elliptical galaxies. As a result, they found that the use of a MOND scalar field produces tight correlations in galaxy properties because in this model the effective halo is not as scattered and free as in CDM ones.

Since the possible corrections implied by this approach would be applicable only at very low accelerations (

![]() ), it should be improbable to detect the effects of MOND in terrestrial-based experiments. Nevertheless, a possible way of measuring the tiny effects of the proposed modified dynamics on the motion of test particles in terrestrial laboratory experiments was presented by Ignatiev (2007). It was shown that the combination of the motion of the Sun around the galaxy with the motion of translation and rotation of the Earth produces two spots on the Earth, symmetric with respect to the latitude coordinates, in which the MOND effects could be probed. In these two spots, of around 0.1 m3 occurring for only a few seconds in each equinox date, static particles would experience a subtle acceleration caused by the MOND regime.

), it should be improbable to detect the effects of MOND in terrestrial-based experiments. Nevertheless, a possible way of measuring the tiny effects of the proposed modified dynamics on the motion of test particles in terrestrial laboratory experiments was presented by Ignatiev (2007). It was shown that the combination of the motion of the Sun around the galaxy with the motion of translation and rotation of the Earth produces two spots on the Earth, symmetric with respect to the latitude coordinates, in which the MOND effects could be probed. In these two spots, of around 0.1 m3 occurring for only a few seconds in each equinox date, static particles would experience a subtle acceleration caused by the MOND regime.

The main objective of this paper is to extend the ideas presented in Ignatiev (2007) and ensure that the above mentioned experiment is feasible any time on other places on Earth. It is expected that the results of this measurement would be valuable in deciding the validity of Newtonian dynamics even in the regime of very small accelerations. It should be emphasized that instead of trying to explain the unusual behavior of specific astronomical systems, this type of measurement should decide which fundamental laws of physics should be applied.

2 Testing the Newton's second law in the small acceleration regime

In the MOND scenario, appreciable corrections to

classical dynamics are required only in the regime of small accelerations a0. As proposed by Ignatiev (2007), using a reference

frame (S0) fixed on the center of mass of the Galaxy, it is possible

to achieve extremely small total accelerations![]() by considering the combined motion of the Sun and the Earth. As presented in Ignatiev (2007), the approximate expression for the acceleration of a test particle at rest on the Earth's surface relative to S0 is given by

by considering the combined motion of the Sun and the Earth. As presented in Ignatiev (2007), the approximate expression for the acceleration of a test particle at rest on the Earth's surface relative to S0 is given by

where

3 An alternative experimental setup

To extend the possibilities of testing the Newtonian dynamics in the small acceleration regime, we include a new rotating object in the above experimental setup. For simplicity, it is considered to be a ring of radius R rotating about its axial axes with angular velocity

![]() .

The direction of the rotation axis can be chosen freely and fixed by assuming the ring to be part of a gyroscopic device. If the ring rotates with constant velocity, a test particle at rest with respect to its surface, identified by the position

.

The direction of the rotation axis can be chosen freely and fixed by assuming the ring to be part of a gyroscopic device. If the ring rotates with constant velocity, a test particle at rest with respect to its surface, identified by the position ![]() will experience, in addition to

will experience, in addition to ![]() ,

an inertial acceleration

,

an inertial acceleration

![]() .

The Coriolis contribution

.

The Coriolis contribution

![]() must appear in the

expression for

must appear in the

expression for ![]() ,

since the test particle will have non-zero motion with

respect to Earth's surface. Thus, with respect to the galactic center-of-mass, the resulting acceleration of the test particle will be given by

,

since the test particle will have non-zero motion with

respect to Earth's surface. Thus, with respect to the galactic center-of-mass, the resulting acceleration of the test particle will be given by

The vector

The acceleration

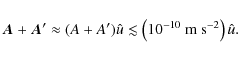

Some estimates show that in order to achieve the regime of small acceleration a0, it is sufficient to produce an additional inertial acceleration A' in the interval

where the limit inferior corresponds to a ground-based experiment about the Earth's poles and the limit superior relates to a ground-based experiment in the equatorial band.

Now let us suppose that the experimental details were provided and the experiment is ready to run. We ask two important questions: what is the size of the ring for which the required small acceleration regime holds and how long is the ring available for a measurement? To answer these questions, we assume that the experiment was prepared so that the axial axes of the ring were such that

For a ring rotating with angular velocity in the interval (in MKS units)

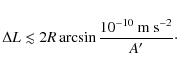

depending on the latitude where the experiment takes place on Earth's surface, the small acceleration regime will be verified only within an angular strip of length

|

(9) |

For instance, if the experiment takes place in an equatorial band, the ring's radius being R=1 m, it can be shown that

4 Final remarks

The proposed approach to testing the small acceleration regime, by adding a rotating annular device (more generally, a gyroscope), can be carried out at any suitable place on Earth (e.g, the Mauna Kea summit in Hawaii, and Cerro Paranal or Cerro Pachón, in Chile, where astronomical observatories are already located), and at any time. This approach is a natural extension of the idea of Ignatiev (2007) of testing fundamental physics at very low acceleration, making his experiment portable to any place on Earth. The price of doing so is a reduced experimental area where the required physical conditions occur, within a shorter interval of time. As the technology of measurement in small areas and short intervals of time increases fast, it is expected that in the near future this type of experiment will be able to be run easily. There are no fundamental restrictions to making these measurements, apart from the high precision of the device involved. At present, the limits stated by the quantum theory are far below the required level of precision. A possible revision of Newton's second law would be required if the results of this experiment indicated that the system exhibited unusual behavior at very low accelerations. In this case, it would be expected that the models already presented in the literature could explain the results of the Milgrom's phenomenological proposal. In terms of astrophysical systems, the possible models that are consistent with the above-mentioned results (if a modification of Newtonian dynamics is required) could be compared directly with cold dark matter theory (Rubin 1983; Bergström 2000; Bertone et al. 2005), MONDs proposals (Milgrom & Sanders 2006; Sanders 2006; Corbelli & Salucci 2007), or with astronomical works such as Famaey & Binney (2005), Gentile et al. (2005,2008), Heymans et al. (2006), and Salucci et al. (2008).Several experimental setups could be developed to achieve the regime of very small accelerations, as discussed in this manuscript. In all cases, the main idea is to add an auxiliary device that can produce an extra acceleration such that the total acceleration over a test particle is cancelled out. It is not the scope of this paper to develop the required setup for this in detail. Nevertheless, for the purpose of shedding light on the matter, some details of a possible experiment are presented below:

- for a 1-m radius ring, the considerations presented in the

last section imply an upper limit to the detection area of

the order of

.

Because of the smallness of the area,

the width of the ring surface should be large enough to avoid

possible errors caused by the pointing process (say, a ring surface width of between 1 and 5 cm);

.

Because of the smallness of the area,

the width of the ring surface should be large enough to avoid

possible errors caused by the pointing process (say, a ring surface width of between 1 and 5 cm);

- to measure the effect of small accelerations on test particles, the surface of the ring could consist of a homogeneous crystal lattice of known molecular structure, and mechanical and electronic properties. The characteristics of the crystal, such as the particle diameter, lattice and dielectric constant, Curie temperature, conductance and the lattice exact phonon mode frequencies could be used for the baseline calibration of the crystal lattice (for lattice dynamics theory see Born & Huang 1954; Walmsley 1975; and Califano et al. 1981). In this case, the detection of the small acceleration regime could be achieved statistically by comparing the calibration laboratory spectral pattern (a control template) with the experimental spectral pattern of the frequencies from the reloaded experimental data.

On the other hand, knowledge of and technical improvements in measuring the mechanical motions within nanostructures, and laboratory advances in the nanocrystal building, allow one to create functional materials of adjustable structure and properties to be used as direct or indirect detectors (using electronic properties and waves) that could be used to measure small acceleration of test perticles (e.g., the use of the Josephson effect: Josephson 1962; Marchenkov et al. 2007; Levy et al. 2007; for detectors: Akulinichev et al. 2005; Beck & Mackey 2005 with reply by Jetzer & Straumann 2005) and to develop ideas about high-temperature superconductivity in the Josephson granular media (Lebedev 2005).

We provide some concluding remarks to this study. First, as discussed in the last section, the rotating device must produce an acceleration on the test particle in the range given by Eq. (6). The exact value depends on the position on Earth where the experiment occurs. Although this acceleration is relatively easy to control, the experiment must be completed so that uncertainties are acceptable only up to the 10th decimal digit. Otherwise the required regime of small accelerations (![]() a0) would not be ``experimentally'' achieved. This condition also applies in Ignatiev (2007), although in this study the difficulty is related to deciding the location for the experiment to be performed.

Second, the precise knowledge of the galactic center of mass can be obtained from the astronomical data. One can indeed identify this center from any place on Earth by means of a position vector defined by the spacetime coordinates of an observer on Earth's surface. We note however that knowledge of this center is necessary only in the case

a0) would not be ``experimentally'' achieved. This condition also applies in Ignatiev (2007), although in this study the difficulty is related to deciding the location for the experiment to be performed.

Second, the precise knowledge of the galactic center of mass can be obtained from the astronomical data. One can indeed identify this center from any place on Earth by means of a position vector defined by the spacetime coordinates of an observer on Earth's surface. We note however that knowledge of this center is necessary only in the case ![]() is considered in the pointing process. This term is already of order a0 and could well be neglected in the measurement procedure.

Finally, we could also introduce a device with non-fixed axes of rotation (relative to Earth's surface), although, care would then have to be taken to ensure the cancellation of the new contribution to the acceleration produced by the extra degree of freedom.

is considered in the pointing process. This term is already of order a0 and could well be neglected in the measurement procedure.

Finally, we could also introduce a device with non-fixed axes of rotation (relative to Earth's surface), although, care would then have to be taken to ensure the cancellation of the new contribution to the acceleration produced by the extra degree of freedom.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the anonimous referee for the useful comments that helped to improve the presentation of the paper. This work was partially supported by the Brazilian funding agencies CNPq and FAPEMIG.

References

- Akulinichev, S. V., Klenov, V. S., Kravchuk, L. V., et al. 2005[arXiv:physics/0511068] (In the text)

- Angus, G. W., & Zhao, H.-S. 2007, MNRAS, 375, 1146 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Angus, G. W., Shan, H.-Y., Zhao, H.-S., et al. 2007, ApJ, 654, L13 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Baltz, E. A., Battaglia, M., Peskin, M. E., et al. 2006, Phys. Rev. D 74, 103521 (In the text)

- Beck, C., & Mackey, M. C. 2005, Phys. Lett. B, 605, 295 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Bekenstein, J. D. 2004, Phys. Rev. D, 70, 083509 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Bekenstein, J. D., & Milgrom, M. 1984, Astrophys. J., 286, 7 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Bergström, L. 2000, Rep. Prog. Phys., 63, 793 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Bertone, G., Hooper, D., & Silk, J. 2005, Phys. Rep., 405, 279 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Born, M., & Huang, K. 1954, in Dynamical Theory of Crystal Lattices (New York: Oxford University Press) (In the text)

- Califano, S., Schettino, V., & Neto, N. 1981, in Lattice Dynamics of molecular Crystals, 26 (Berlin: Springer-Verlag) (In the text)

- Clowe, D., Bradac, M., Gonzalez, A. H., et al. 2006, ApJ, 648, L109 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Corbelli, E., & Salucci, P. 2007, MNRAS, 374, 1051 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Cowsik, R., & Ghosh, P. 1986, J. Astrophys. Astron., 7, 17 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Famaey, B., & Binney, J. 2005, MNRAS, 363, 603 [NASA ADS] (In the text)

- Famaey, B., Bruneton, J.-P., & Zhao, H. 2007, MNRAS, 377, L79 [NASA ADS]

- Famaey, B., Gentile, G., Bruneton, J.-P., et al. 2007, Phys. Rev. D, 75, 063002 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Gentile, G., Burkert, A., Salucci, P., Klein, U., & Walter, F. 2005, ApJ, 634, L145 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Gentile, G., Famaey, B., Combes, F., et al. 2007, A&A, 472, L25 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] (In the text)

- Gentile, G., Burkert, A., Salucci, P., Klein, U., & Walter, F. 2008 [arXiv:astro-ph/0506538v4]

- Green, A. M. 2007, JCAP, 0708, 022 [NASA ADS] (In the text)

- Heymans, C., Bell, E. F., Rix, H.-W., et al. 2006, MNRAS, 371, L60 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Ignatiev, A. Yu. 2007, , 98, 101101 (In the text)

- Jetzer, P., & Straumann, N. 2005, Phys. Lett. B, 606, 77 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Josephson, B. D. 1962, Phys. Lett. 1, 251 (In the text)

- Kong, X. 2004, A&A, 425, 417 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences]

- Lebedev, S. G. 2005 [arXiv:cond-mat/0510304] (In the text)

- Levy, S., Lahoud, E., Shomroni, I., et al. 2007, Nature, 449, 579 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Mahdavi, A., Hoekstra, H., Babul, A., Balam, D., & Capak, P. 2007, ApJ, 668, 806 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Marchenkov, A., Dai, Z., Zhang, C., et al. 2007, Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 046802 (In the text)

- Milgrom, M. 1983a, ApJ, 270, 365 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Milgrom, M. 1983b, ApJ, 270, 371 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Milgrom, M., & Sanders, R. H. 2006 [arXiv:astro-ph/0611494v1] (In the text)

- Penny, S. J., Conselice, C. J., De Rijcke, S., & Held, E. V. 2009, MNRAS, 393, 1054 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Rubin, V. C. 1983, Science, 220, 1339 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Rubin, V. C. 1983, in Internal Kinematics and Dynamics of Galaxies, ed. E. Athanassoula, IAU Symp., 100, 3 (In the text)

- Rubin, V. C. 1983, in Kinematics, Dynamics and Structure of the Milky Way, ed. W. L. Shuter (Dordrecht: Reidel), 379

- Salucci, P., Lapi, A., Tonini, C., et al. 2008 [arXiv:astro-ph/0703115v2] (In the text)

- Sanders, R. H. 2006 [arXiv:astro-ph/0601431v2] (In the text)

- Sanders, R. H. 2008, MNRAS, 386, 1588 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Sanders, R. H., & McGaugh, S. S. 2002, ARA&A, 40, 263 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Tiret, O., & Combes, F. 2007, Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the French Society of Astronomy and Astrophysics, SF2A-2007-July 2-6, 356 (In the text)

- Ullio, P., Zhao, H., & Kamionkowski, M. 2001, Phys. Rev. D 64, 043504 (In the text)

- Walmsley, S. H. 1975, Basic Theory of the Lattice Dynamics and Intermolecular Forces, ed. L. V. Corso (New York: Academic Press) (In the text)

- Wu, X., Zhao, H., Famaey, B., et al. 2007, ApJ, 665, L101 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X., Famaey, B., Gentile, G., Perets, H., & Zhao, H. 2008, MNRAS, 386, 2199 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H. S., Xu, B. X., & Dobbs, C. 2008, ApJ, 686, 1019 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

Footnotes

- ...

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- Here m represents the gravitational mass and

is the conventional gravitational field, deduced from a mass distribution using Poisson's equation.

is the conventional gravitational field, deduced from a mass distribution using Poisson's equation.

- ... accelerations

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- It should be emphasized that the existence of small accelerations with respect to the laboratory is an insufficient condition to achieve the MOND regime. It is also necessary to consider external accelerations (caused by objects outside the laboratory), which would explain some observed phenomena in light of MOND (Famaey et al. 2007; Wu et al. 2007,2008).

Copyright ESO 2009

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.