| Issue |

A&A

Volume 503, Number 1, August III 2009

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Page(s) | 287 - 291 | |

| Section | Celestial mechanics and astrometry | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/200811489 | |

| Published online | 15 June 2009 | |

Free core nutation resonance parameters from VLBI and superconducting gravimeter data

S. Rosat1 - S. B. Lambert2

1 - Institut de Physique du Globe de Strasbourg, IPGS - UMR 7516, CNRS et Université de Strasbourg (EOST), 67084 Strasbourg, France

2 -

Observatoire de Paris,

Département Systèmes de Référence Temps Espace (SYRTE),

UMR 8630, CNRS, 75014 Paris, France

Received 9 December 2008 / Accepted 20 May 2009

Abstract

Context. Free core nutation (FCN) can be observed by its associated resonance effects on the forced nutations of the Earth's figure axis, as observed by very long baseline interferometry (VLBI), or on the diurnal tidal waves, retrieved from the time-varying surface gravity recorded by superconducting gravimeters (SG).

Aims. In this paper, we study the sensitivity of both techniques to FCN parameters.

Methods. We analyze surface gravity data from 15 SG stations and VLBI delays accumulated over the last 24 years.

Results. We obtain estimates of the FCN period and quality factor that are consistent for both techniques. The inversion leads to a quality factor centered on ![]() 16 600 with an uncertainty of

16 600 with an uncertainty of ![]() 3500 from SG and of

3500 from SG and of ![]() 900 from VLBI, and to a resonant period within [-423.3, -430.5] days for SG and [-427.8, -431.4] days for VLBI (3

900 from VLBI, and to a resonant period within [-423.3, -430.5] days for SG and [-427.8, -431.4] days for VLBI (3![]() interval).

interval).

Key words: reference systems - Earth

1 Introduction

Free core nutation (FCN) is a rotational normal mode of the Earth that exists because of the presence of a fluid core inside the visco-elastic mantle. In a space-fixed reference frame, the resonant period of the FCN is close to 430 days retrograde, leading to an amplification of the Earth's nutational and deformational responses to tidal forcing.

The resonance associated with the FCN has been widely studied in

time-varying gravity data recorded with relative gravimeters, mainly

superconducting gravimeters (SG) of the Global Geodynamics Project

(GGP, Crossley et al. 1999). The first analysis of the FCN

effects in gravity data was performed by Neuberg et al. (1987);

attempting to determine the resonant period, they obtained

![]() days and a quality factor

days and a quality factor

![]() ,

defined so the

complex frequency is

,

defined so the

complex frequency is

![]() in cycles per sidereal day.

This study was followed by many others (e.g., Cummins & Wahr 1993; Sato et al. 1994, 2004; Ducarme et al. 2009). Defraigne et al. (1994, 1995), using a combination of very long baseline

interferometry (VLBI) nutation and SG gravity data,

obtained a period of

in cycles per sidereal day.

This study was followed by many others (e.g., Cummins & Wahr 1993; Sato et al. 1994, 2004; Ducarme et al. 2009). Defraigne et al. (1994, 1995), using a combination of very long baseline

interferometry (VLBI) nutation and SG gravity data,

obtained a period of ![]() days and a quality factor

higher than 17 000. More recently, Ducarme et al. (2009)

analyzed the European SG data, and found a period of

days and a quality factor

higher than 17 000. More recently, Ducarme et al. (2009)

analyzed the European SG data, and found a period of ![]() days

and a quality factor of

days

and a quality factor of

![]() .

.

The signature of the FCN in the forced nutations was studied

by Herring et al. (1986) and Gwinn et al. (1986)

using VLBI observations. The authors interpreted the enhancement of the

amplitude of the retrograde annual nutation induced by the resonance in terms

of a departure of the core-mantle boundary from its hydrostatic figure.

Using an improved theoretical background,

Mathews et al. (2002) built a nutation model

(referred to as MHB) based on a limited number of parameters describing

the Earth's interior and adjusted to VLBI data up to 1999. Comparisons of

the VLBI nutation time series with this model reveal differences of

the order of

200 microarc seconds (![]() as) in rms. These residuals are the consequence

of various mismodeled or unmodeled influences in the observational

strategy as well as in geophysical processes (see e.g., Dehant et al. 2003).

The authors found an FCN resonant period of -430.21 days

and a quality factor of 20 000.

The values of the FCN period and quality factor were confirmed

by Vondrák et al. (2005) using a combination of VLBI and GNSS-derived

nutation amplitudes and inverting only the resonance parameters

(to which the nutation amplitudes are the most sensitive within the diurnal

band). However, Lambert & Dehant (2007), who analyzed VLBI data

sets produced independently by various VLBI analysis centers, noticed a

smaller value for

as) in rms. These residuals are the consequence

of various mismodeled or unmodeled influences in the observational

strategy as well as in geophysical processes (see e.g., Dehant et al. 2003).

The authors found an FCN resonant period of -430.21 days

and a quality factor of 20 000.

The values of the FCN period and quality factor were confirmed

by Vondrák et al. (2005) using a combination of VLBI and GNSS-derived

nutation amplitudes and inverting only the resonance parameters

(to which the nutation amplitudes are the most sensitive within the diurnal

band). However, Lambert & Dehant (2007), who analyzed VLBI data

sets produced independently by various VLBI analysis centers, noticed a

smaller value for

![]() .

(Note that in their paper, the values

of the quality factor were incorrect due to a sign error in the code:

their symmetry with respect to 20 000 must be considered, leading

to values around 17 000 instead of 23 000.)

The values of other geophysical parameters estimated in MHB were

recently confirmed by Koot et al. (2008) using a longer VLBI data

set and a different estimation method. Although the FCN period found in

the latter work is close to the MHB value, the quality factor appears

to be lower by

.

(Note that in their paper, the values

of the quality factor were incorrect due to a sign error in the code:

their symmetry with respect to 20 000 must be considered, leading

to values around 17 000 instead of 23 000.)

The values of other geophysical parameters estimated in MHB were

recently confirmed by Koot et al. (2008) using a longer VLBI data

set and a different estimation method. Although the FCN period found in

the latter work is close to the MHB value, the quality factor appears

to be lower by ![]() 30%. The reason for the discrepancy has not

yet been determined.

30%. The reason for the discrepancy has not

yet been determined.

Some studies tried to identify a time variation of the frequency of the FCN resonance, either in VLBI nutation or in SG gravity data (Roosbeek et al. 1999; Hinderer et al. 2000). In both papers, the authors concluded that the apparent time-variation is not real but is due to the time-variable excitation of the free mode. Vondrák & Ron (2006) and Lambert & Dehant (2007) have shown that the resonant period is stable around -430 days to within half a day. The former authors argued that the FCN period, being given by the internal structure of the Earth (mainly the flattening of the core), it is highly improbable that it is very variable in time.

In the studies listed above, large discrepancies appear between

VLBI- and SG-derived values of

![]() .

This paper aims at investigating these differences.

To that purpose, we check the sensitivity of both gravity and nutation data

to the Earth's interior parameters. The functions

describing the response in gravity and in nutation to the tidal forcing,

and their sensitivity, are addressed in Sect. 2.

In Sect. 3, the FCN resonance parameters are retrieved

from the gravity and nutation data. Results are discussed

in Sect. 4.

.

This paper aims at investigating these differences.

To that purpose, we check the sensitivity of both gravity and nutation data

to the Earth's interior parameters. The functions

describing the response in gravity and in nutation to the tidal forcing,

and their sensitivity, are addressed in Sect. 2.

In Sect. 3, the FCN resonance parameters are retrieved

from the gravity and nutation data. Results are discussed

in Sect. 4.

2 Response in gravity and nutation to the tidal forcing

2.1 Tidal gravity

The tidal variations observed at the Earth's surface are induced by

the direct effect of the tidal potential, the deformation and the mass

redistribution in the mantle due to this potential. The (direct,

deformation and mass redistribution) effects of the centripetal potential due

to the Earth's wobble must also be considered. Also, the inertial

pressure at the core-mantle boundary (CMB) due to the differential rotation

between the mantle and the core induces a deformation of the CMB

as well as mass redistribution in the mantle that also generates

time variations of the gravity field. Summing all these effects

and dividing by the gravity variations for a non-rotating rigid

Earth leads to the tidal gravimetric

factor (Neuberg et al. 1987; Hinderer et al. 1991;

Legros et al. 1993):

hereafter referred to as the gravimetric transfer function, where

|

(2) |

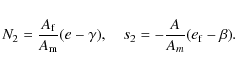

In the above expressions, s2 is the complex resonant frequency of the FCN, e and

An Earth made up of a mantle, a fluid core and a solid inner core admits three additional resonances. Two of them are in the low-frequency band: the Chandler wobble (CW) and the inner core wobble (ICW); the remaining one, the free inner core nutation (FICN), lies in the quasi diurnal band. To the model proposed in Eq. (1), we could add these resonance effects (see for instance Legros et al. 1993; Mathews et al. 1995). However, their effects would be far smaller than the error of the gravity data, so we have decided not to include them.

Equation (1) allows one to compute how much the T(g)

is sensitive to departures of the various

parameters from their ``standard'' values.

We compute the sensitivity

![]() to a parameter pincremented by

to a parameter pincremented by ![]() at the frequency

at the frequency ![]() as

as

|

(3) |

The two-dimensional functions S are drawn in Fig. 1 for parameters

![\begin{figure}

\par\mbox{\includegraphics[width=4.4cm]{11489fg1.eps}\hspace*{1mm...

...g3.eps}\hspace*{1mm}

\includegraphics[width=4.4cm]{11489fg4.eps} }\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/31/aa11489-08/Timg30.png) |

Figure 1:

Sensitivity of the gravimetric transfer function T(g) to the

parameters

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

2.2 Nutation

The frequency domain response of the space motion of the Earth's figure axis to the tidal potential can be written with a transfer function that expresses the ratio between rigid and non-rigid nutation amplitudes (resp. ![]() and

and ![]() ;

see, e.g., Mathews et al. 2002). One has

;

see, e.g., Mathews et al. 2002). One has

![]() ,

wherein, neglecting the ICW

effects,

,

wherein, neglecting the ICW

effects,

where the last three bracketed terms express the CW, FCN, and FICN resonance, respectively, with

|

(5) |

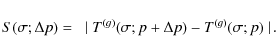

The flattening

![\begin{figure}

\par\mbox{\includegraphics[width=4.4cm]{11489fg5.eps}\hspace*{1mm...

...g7.eps}\hspace*{1mm}

\includegraphics[width=4.4cm]{11489fg8.eps} }\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/31/aa11489-08/Timg40.png) |

Figure 2:

Sensitivity of the nutation transfer function T(n) to the parameters

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

The sensitivity analysis of T(n) to parameters N2, s1, s2, and s3 (Fig. 2) reveals that the nutations are primarily sensitive to the FCN frequency s2, then to its amplitude N2, and less sensitive to the Chandler frequency s1 (not shown in the figure) and to the FICN frequency s3.

3 Determination of the FCN resonance parameters

3.1 Tidal gravity

Since we are looking for Earth's global interior parameters, we take advantage of worldwide records in order to minimize local effects. Thus, we analyze 15 datasets from the SG located in Boulder (USA), Bad-Homburg (Germany), Cantley (Canada), Canberra (Australia), Esashi (Japan), Matsushiro (Japan), Moxa (Germany), Membach (Belgium), Medicina (Italy), Metsahovi (Finland), Potsdam (Germany), Strasbourg (France), Vienna (Austria), Wettzell (Germany) and Wuhan (China). For all, the record length is more than 5 years.

The SG time-varying gravity records have been corrected for any gaps, spikes, steps and other disturbance so that a tidal analysis with the ETERNA software package (Wenzel 1996) is possible. Before the tidal analysis is done, the minute data are resampled to 1 h (using a filter with a cut-off period of 3 h). ETERNA then performs a least-square fit to tides, local air pressure

and instrumental drift to give complex gravimetric factors, residual gravity, an adjusted barometric admittance, and a polynomial drift function. The data to be inverted are the complex gravimetric

factors corrected for the ocean tide loading effect according to the FES 2004 ocean model (Lyard et al. 2006). An example of tidal gravimetric factors obtained at Strasbourg and

corrected for the ocean loading effect is superimposed on the observed nutation amplitudes in Fig. 3. The errors on the imaginary parts of the tidal waves ![]() and

and ![]() ,

which are the closest to the resonance, are very large, while the corresponding nutation amplitudes

(annual and semi-annual retrograde) are well determined.

,

which are the closest to the resonance, are very large, while the corresponding nutation amplitudes

(annual and semi-annual retrograde) are well determined.

We use optimized linearized least-squares based

on the Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm (Marquardt 1963;

Defraigne et al. 1994, 1995).

To force the quality factor to be positive, we introduce the variable

![]() .

The least-squares

implicitly suppose that the

parameters are Gaussian distributed, which is not the case for

.

The least-squares

implicitly suppose that the

parameters are Gaussian distributed, which is not the case for

![]() (Florsch & Hinderer 2000), but should be the case for x if the

data had weak errors (Rosat et al. 2009). Rosat et

al. (2009) have demonstrated that there is a good agreement

between the linearized Levenberg-Marquardt results and the

Bayesian statistic method.

(Florsch & Hinderer 2000), but should be the case for x if the

data had weak errors (Rosat et al. 2009). Rosat et

al. (2009) have demonstrated that there is a good agreement

between the linearized Levenberg-Marquardt results and the

Bayesian statistic method.

Because of the strong correlation of N2 with

![]() (99%),

and the small number of tidal gravity data points (only 9 diurnal tidal waves),

we will not invert this parameter from gravity tidal factors but rather fix

it to the value obtained from the inversion of the nutation data.

Indeed, the value of N2 has been well constrained in

MHB or Koot et al. (2008). Thus, the inversion

is carried out for x,

(99%),

and the small number of tidal gravity data points (only 9 diurnal tidal waves),

we will not invert this parameter from gravity tidal factors but rather fix

it to the value obtained from the inversion of the nutation data.

Indeed, the value of N2 has been well constrained in

MHB or Koot et al. (2008). Thus, the inversion

is carried out for x,

![]() ,

,

![]() and

and

![]() .

Finally, we get

.

Finally, we get

![]() .

The period

of the FCN is

.

The period

of the FCN is

![]() days and its quality factor

is

days and its quality factor

is

![]() .

(The errors correspond to

.

(The errors correspond to ![]() .)

.)

3.2 Nutation

Nutation time series were obtained by a single inversion of

ionosphere-free VLBI delays accumulated during ![]() 3800 24-h observing

sessions of routine geodetic VLBI observations spanning

1984.0-2008.7

3800 24-h observing

sessions of routine geodetic VLBI observations spanning

1984.0-2008.7![]() .

Earth orientation parameters were estimated once per session, while

station coordinates and velocities and most of radio source coordinates were

estimated as global parameters over the 24 years. The celestial frame was

maintained by a no net rotation constraint over the coordinates of

247 sources selected by Feissel-Vernier et al. (2006), ensuring a

relative time stability of the frame axes. Doing so, one avoids

contaminating the estimated nutation offsets by radio source instabilities.

All the calculations used the

Calc 10.0/Solve 2008.12.05 geodetic VLBI analysis software package

developped and maintained at NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center, and

were carried out at the Paris

Observatory IVS Analysis Center (Gontier et al. 2008) as

part of the International VLBI Service for Geodesy and

Astrometry (IVS, Schlüter & Behrend 2007).

.

Earth orientation parameters were estimated once per session, while

station coordinates and velocities and most of radio source coordinates were

estimated as global parameters over the 24 years. The celestial frame was

maintained by a no net rotation constraint over the coordinates of

247 sources selected by Feissel-Vernier et al. (2006), ensuring a

relative time stability of the frame axes. Doing so, one avoids

contaminating the estimated nutation offsets by radio source instabilities.

All the calculations used the

Calc 10.0/Solve 2008.12.05 geodetic VLBI analysis software package

developped and maintained at NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center, and

were carried out at the Paris

Observatory IVS Analysis Center (Gontier et al. 2008) as

part of the International VLBI Service for Geodesy and

Astrometry (IVS, Schlüter & Behrend 2007).

Prograde and retrograde amplitudes of the terms listed in Table 1 of the MHB

paper, jointly with a linear trend on each component, were obtained by a

weighted least-squares fit to the time series. To get realistic errors on

data, we inflated the variance of each data point

by an additive variance of 0.015 mas2,

and a scale factor of 1.8 (see Herring et al. 1991,

2002; Lambert et al. 2008). The obtained nutation

amplitudes were corrected for effects that are not, or are non linearly,

linked to non rigidity, including the geodetic nutation, the S1 atmospheric

tide, and the contribution of second order terms in the dynamical

equations of the Earth's rotation. The relevant values

were taken from Table 6 of the MHB paper for the former two effects,

and in Lambert & Mathews (2006, 2008) for the latter.

The ratio of the observed (fitted) nutation amplitudes to the rigid ones

taken in the REN 2000 theory (Souchay et al. 1999) are plotted in

Fig. 3. Note the good agreement between the observations and

the MHB transfer function using

![]() days and

days and

![]() .

.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{11489fg9.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/31/aa11489-08/Timg52.png) |

Figure 3: Observed transfer functions for nutation (dots) and gravity (stars) obtained from VLBI and SG measurements, respectively. The corresponding theoretical ones are plotted in solid line for nutation, and in dashed line for gravity. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

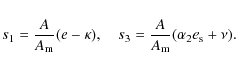

From the fitted set of nutation amplitudes, we estimate s1,

N2, s2, and s3. These geophysical parameters are correlated and the highest correlation (![]() 0.9) shows up between the FCN and the FICN frequencies s2 and s3.

0.9) shows up between the FCN and the FICN frequencies s2 and s3.

In order to check that the inverted parameters are Gaussian distributed, we compute their

probability density functions (pdfs) using the full transfer function

of the resonance as defined in Eq. (4). As our knowledge of the parameters is imperfect,

we consider them as probabilistic rather than deterministic. The resulting joint pdfs

are represented in Fig. 4 for the parameters x,

![]() ,

s1 and N2. The

,

s1 and N2. The ![]() -test shows that the distribution for xcan be supposed Gaussian with an error of

-test shows that the distribution for xcan be supposed Gaussian with an error of ![]() .

Note also the tilted shape of the pdfs

between the real and imaginary parts of s1 and N2 that indicates

a correlation between these parameters. The Levenberg-Marquardt least-square

fit gives

.

Note also the tilted shape of the pdfs

between the real and imaginary parts of s1 and N2 that indicates

a correlation between these parameters. The Levenberg-Marquardt least-square

fit gives

![]() days,

days,

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

,

![]() days,

days,

![]() ,

with

the error corresponding to

,

with

the error corresponding to ![]() .

.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{11489f10.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/31/aa11489-08/Timg61.png) |

Figure 4:

Joint probability density functions of x,

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

A joint inversion of VLBI nutation and SG gravity data has

also been performed to determine x and

![]() .

However, the amplitudes of the tidal waves that best constrain the

FCN frequency and damping (mainly

.

However, the amplitudes of the tidal waves that best constrain the

FCN frequency and damping (mainly ![]() and

and ![]() )

are weak while the corresponding nutation

amplitudes (mainly the annual and semi-annual retrograde) are substantial.

The ocean loading effect is a main source of error on the gravity signal

while the effect of the tidal ocean on the Earth's nutation is weak.

Therefore x and

)

are weak while the corresponding nutation

amplitudes (mainly the annual and semi-annual retrograde) are substantial.

The ocean loading effect is a main source of error on the gravity signal

while the effect of the tidal ocean on the Earth's nutation is weak.

Therefore x and

![]() are better estimated

using VLBI data than using surface gravity data, and a joint inversion

does not improve the results obtained using VLBI data alone.

are better estimated

using VLBI data than using surface gravity data, and a joint inversion

does not improve the results obtained using VLBI data alone.

4 Concluding remarks

Estimates of the FCN resonance parameters from nutation or

gravity measurements are comparable within the error bars (Table 1).

The FCN period is close to -430 days using VLBI

and slightly lower by a few days from gravity data. The FCN quality

factor estimated either from nutation or from gravity data

tends to be around 17 000 with error bars of ![]() 1000.

Tidal gravity observations bring additional constraints to the Earth's

interior by leading to an estimate of the internal pressure Love number.

Interpretation of these estimates in terms of dissipative torques

at the core boundaries needs more assumptions and internal modeling

to separate the respective parts of electromagnetism and viscosity. This

problem will not be addressed here.

1000.

Tidal gravity observations bring additional constraints to the Earth's

interior by leading to an estimate of the internal pressure Love number.

Interpretation of these estimates in terms of dissipative torques

at the core boundaries needs more assumptions and internal modeling

to separate the respective parts of electromagnetism and viscosity. This

problem will not be addressed here.

Table 1: Values of the FCN resonance parameters obtained from nutation and gravity measurements.

Our study has shown that surface gravity is as sensitive as nutation to the FCN resonance frequency and damping factor. The discrepancy between gravity and nutation is due to the large errors arising from the diurnal tidal wave determinations that are the closest to the FCN resonance.

As time elapses, improvements in both techniques are progressively

removing systematic effects that produce discrepancies in estimates

of the same geophysical

quantities. Geophysical parameters estimated from VLBI will

improve in accuracy in the next five or ten years,

not only because of better quality

data or reference frame realization, but also because the longer

time span will permit one to decorrelate the 18.6-yr tidal term and the

linear trend. For SG data, longer time-series will enable us

to better determine ![]() and

and ![]() tidal waves but

improvements are also necessary in the modeling

of the ocean loading effects in the diurnal frequency band.

tidal waves but

improvements are also necessary in the modeling

of the ocean loading effects in the diurnal frequency band.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank M. Llubes for her computation of the ocean loading corrections at the SG sites. We are also grateful to the GGP members for making the SG datasets available, and to the IVS for their constant effort in scheduling VLBI sessions and correlating them. S. Rosat particularly thanks N. Florsch for his useful explanations about the Bayesian method. We are finally grateful to the anonymous reviewer for comments on this manuscript.

References

- Crossley, D., Hinderer, J., Casula, G., et al. 1999, EOS, 80, 121 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Cummins, P., & Wahr, J. 1993, J. Geophys. Res., 98, 2091 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Defraigne, P., Dehant, V., & Hinderer, J. 1994, J. Geophys. Res., 99, 9203 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Defraigne, P., Dehant, V., & Hinderer, J. 1995, J. Geophys. Res., 100 (B2), 2041 (In the text)

- Dehant, V., Hinderer, J., Legros, H., & Lefftz, M. 1993, Phys. Earth Planet. Interiors, 76, 259 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Dehant, V., Feissel-Vernier, M., de Viron, O., et al. 2003, J. Geophys. Res., 108, 2275 [CrossRef]

- Dehant, V., de Viron, O., & Greff-Lefftz, M. 2005, A&A, 438, 1149 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] (In the text)

- Ducarme, B., Rosat, S., Vandercoilden, L., et al. 2009, in Observing our Changing Earth, ed. M. G. Sideris, Proc. 2007 IAG General Assembly, 523 (In the text)

- Dziewonski, A. M., & Anderson, D. L. 1981, PEPI, 25, 297 [NASA ADS]

- Florsch, N., & Hinderer, J. 2000, PEPI, 117, 21 [NASA ADS] (In the text)

- Feissel-Vernier, M., Ma, C., Gontier, A.-M., & Barache, C. 2006, A&A, 452, 1107 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] (In the text)

- Gontier, A.-M., Lambert, S. B., & Barache, C. 2008, in International VLBI Service for Geodesy and Astrometry (IVS) 2007 Annual Report, ed. D. Behrend, K. D. Baver, NASA/TP-2008-214162, 224 (In the text)

- Gwinn, C. R., Herring, T. A., & Shapiro, I. I. 1986, J. Geophys. Res., 91, 4755 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Herring, T. A., Gwinn, C. R., & Shapiro, I. I. 1986, J. Geophys. Res., 91, 4745 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Herring, T. A., Buffet, B. A., Mathews, P. M., & Shapiro, I. I. 1991, J. Geophys. Res., 96 (B5), 8259 (In the text)

- Herring, T. A., Mathews, P. M., & Buffet, B. A. 2002, J. Geophys. Res., 107 (B4), 10.1029/2001JB000165 (In the text)

- Hinderer, J., Zürn, W., & Legros, H. 1991, in Proc. 11th Int. Symp. Earth Tides, Schweitzerbart, ed. J. Kakkuri (Stuttgart: Verlag), 549 (In the text)

- Hinderer, J., Boy, J.-P., Gegout, P., et al. 2000, Phys. Earth Planet. Interiors, 117, 37 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Koot, L., Rivoldini, A., de Viron, O., & Dehant, V. 2008, J. Geophys. Res., 113, (B08414), 10.1029/2007JB005409 (In the text)

- Lambert, S. B., & Dehant, V. 2007, A&A, 469, 777 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] (In the text)

- Lambert, S. B., & Mathews, P. M. 2006, A&A, 453, 363 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] (In the text)

- Lambert, S. B., & Mathews, P. M. 2008, A&A, 481, 883 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] (In the text)

- Lambert, S. B., Dehant, V., & Gontier, A.-M. 2008, A&A, 481, 535 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] (In the text)

- Legros, H., Hinderer, J., Lefftz, M., & Dehant, V. 1993, Phys. Earth Planet. Interiors, 76, 283 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Lyard, F., Lefèvre, F., Letellier, T., & Francis, O. 2006, Ocean Dynamics, 56, 394 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Marquardt, D. 1963, J. Soc. Indust. Appl. Math., 11, 431 [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Mathews, P. M., Buffet, B. A., & Shapiro, I. I. 1995, J. Geophys. Res., 100, 9935 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Mathews, P. M., Herring, T. A., & Buffet, B. A. 2002, J. Geophys. Res., 107 (B4), 10.1029/2001JB000390 (In the text)

- Neuberg, J., Hinderer, J., & Zürn, W. 1987, Geophys. J. R. Astr. Soc., 91, 853 (In the text)

- Roosbeek, F., Defraigne, P., Feissel, M., & Dehant, V. 1999, Geophys. Res. Lett., 26, 131 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Rosat, S., Florsch, N., Hinderer, J., & Llubes, M. 2009, J. Geodyn., in press (In the text)

- Sato, T., Tamura, Y., Higashi, T., et al. 1994, J. Geomag. Geoelectr., 46, 571 (In the text)

- Sato, T., Tamura, Y., Matsumoto, K., et al. 2004, J. Geodyn., 38, 375 [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Schlüter, W., & Behrend, D. 2007, J. Geod., 81, 479 [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Souchay, J., Loysel, B., Kinoshita, H., & Folgueira, M. 1999, A&A, 135, 111 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Vondrák, J., & Ron, C. 2006, Acta Geodyn. Geomater., 3, 53 (In the text)

- Vondrák, J., Ron, C., & Weber, R. 2005, A&A, 444, 297 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences]

- Wenzel, H. G. 1996, Bull. Inf. Marées Terrestres, 124, 9425 (In the text)

Footnotes

- ...

1984.0-2008.7

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- The data set and its description file are available via anonymous ftp at ftp://ivsopar.obspm.fr/vlbi/ivsproducts/eops/opa2008d.eops.gz, ftp://ivsopar.obspm.fr/vlbi/ivsproducts/eops/opa2008d.eops.txt.

All Tables

Table 1: Values of the FCN resonance parameters obtained from nutation and gravity measurements.

All Figures

![\begin{figure}

\par\mbox{\includegraphics[width=4.4cm]{11489fg1.eps}\hspace*{1mm...

...g3.eps}\hspace*{1mm}

\includegraphics[width=4.4cm]{11489fg4.eps} }\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/31/aa11489-08/Timg30.png) |

Figure 1:

Sensitivity of the gravimetric transfer function T(g) to the

parameters

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\mbox{\includegraphics[width=4.4cm]{11489fg5.eps}\hspace*{1mm...

...g7.eps}\hspace*{1mm}

\includegraphics[width=4.4cm]{11489fg8.eps} }\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/31/aa11489-08/Timg40.png) |

Figure 2:

Sensitivity of the nutation transfer function T(n) to the parameters

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{11489fg9.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/31/aa11489-08/Timg52.png) |

Figure 3: Observed transfer functions for nutation (dots) and gravity (stars) obtained from VLBI and SG measurements, respectively. The corresponding theoretical ones are plotted in solid line for nutation, and in dashed line for gravity. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{11489f10.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/31/aa11489-08/Timg61.png) |

Figure 4:

Joint probability density functions of x,

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

Copyright ESO 2009

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.

![$\displaystyle T^{(g)}(\sigma)=\delta_2(1-e)-\frac{eN_2}{\sigma^{\prime}- s_2} \biggl[\delta_2

\sigma^{\prime}+\overline \delta_1 \frac{A}{A_{\rm f}} \biggr],$](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/31/aa11489-08/img14.png)

![\begin{displaymath}

T^{(n)}(\sigma)=\frac{e-\sigma}{e+1}\left[1

-\frac{\sigma^{\...

..._2}

+\frac{\sigma^{\prime}N_3}{\sigma^{\prime}- {s}_3}\right],

\end{displaymath}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/31/aa11489-08/img34.png)