| Issue |

A&A

Volume 502, Number 2, August I 2009

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Page(s) | 473 - 498 | |

| Section | Extragalactic astronomy | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/200911637 | |

| Published online | 13 May 2009 | |

Small-scale systems of galaxies

IV. Searching for the faint galaxy population associated with X-ray detected isolated E+S pairs

R. Grützbauch1,2 - W. W. Zeilinger1 - R. Rampazzo3 - E. V. Held3 - J. W. Sulentic4 - G. Trinchieri5

1 - Institut für Astronomie, Universität Wien, Türkenschanzstraße 17, 1180 Wien, Austria

2 - University of Nottingham, School of Physics and Astronomy, Nottingham NG7 2RD, UK

3 - INAF - Osservatorio Astronomico di Padova, Vicolo dell'Osservatorio 5, 35122, Padova, Italy

4 - Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, AL 35487, USA

5 - INAF - Osservatorio Astronomico di Brera, via Brera 28, 20121, Milano, Italy

Received 9 January 2009 / Accepted 11 March 2009

Abstract

Context. In hierarchical evolutionary scenarios, isolated, physical pairs may represent an intermediate phase, or ``way station'', between collapsing groups and isolated elliptical (E) galaxies (or fossil groups).

Aims. We started a comprehensive study of a sample of galaxy pairs composed of a giant E and a spiral (S) with the aim of investigating their formation/evolutionary history from observed optical and X-ray properties.

Methods. We present VLT-VIMOS observations designed to identify faint galaxies associated with the E+S systems from candidate lists generated using photometric criteria on WFI images covering an area of ![]() 0.2

h100-1 Mpc radius around the pairs.

0.2

h100-1 Mpc radius around the pairs.

Results. We found two and ten new members likely to be associated with the X-ray bright systems RR 143 and RR 242, respectively. The X-ray faint RR 210 and RR 216, which were only partially covered by the VIMOS observations, have two and three new faint members, respectively. The new members increase the number of associated galaxies to 4, 7, 6, and 16 for RR 143, RR 210, RR 216, and RR 242, respectively, down to

![]() .

We derive structural properties of the faint members from surface photometry. The faint galaxy population of all the systems is dominated by disk galaxies, 40% being S0s with generally low bulge to total light ratios. A small fraction of the faint companions show signatures of interaction. A remarkable shell system is detected in the early-type galaxy RR 242_24532. We also derive dynamical properties and optical luminosity functions for the 4 groups.

.

We derive structural properties of the faint members from surface photometry. The faint galaxy population of all the systems is dominated by disk galaxies, 40% being S0s with generally low bulge to total light ratios. A small fraction of the faint companions show signatures of interaction. A remarkable shell system is detected in the early-type galaxy RR 242_24532. We also derive dynamical properties and optical luminosity functions for the 4 groups.

Conclusions. The above results are discussed in the context of the evolution of poor galaxy group associations. A comparison between the optical luminosity functions (OLFs) of our E+S systems and a sample of X-ray bright poor groups suggest that the OLF of X-ray detected poor galaxy systems is not universal. The OLF of our X-ray bright systems suggests that they are more dynamically evolved than our X-ray faint sample and some X-ray bright groups in the literature. However, we suggest that the X-ray faint E+S pairs represent a phase in the dynamical evolution of some X-ray bright poor galaxy groups. The recent or ongoing interaction in which the E member of the X-ray faint pairs is involved could have decreased the luminosity of any surrounding X-ray emitting gas.

Key words: galaxies: evolution - galaxies: individual: RR 143 (NGC 2305/2307), RR 210 (NGC 4105/4106), RR 216 (IC 3290/NGC 4373), RR 242 (NGC 5090/5091)

1 Introduction

The X-ray signature of a hot intra-group medium (IGM) has been detected in loose groups containing an early-type galaxy population (e.g., Mulchaey 2000). The pioneering work of Zabludoff (1999) suggested that groups might fall into different classes defined by their X-ray properties: from groups with a luminous, extended, hot IGM centred on a giant E to groups with little or no diffuse emission. Several examples of these classes can now be found in the literature (see e.g., Ota et al. 2004; Trinchieri et al. 2003; Mulchaey et al. 2003; Belsole et al. 2003). In a hierarchical evolutionary scenario, the final product of a merged group would be a luminous isolated E with an extended X-ray halo, and a few have indeed been identified (see e.g., Khosroshahi et al. 2004; Jones et al. 2003; Mulchaey & Zabludoff 1999; Vikhlinin et al. 1999). Jones et al. (2003) estimated the incidence of fossil groups. They found that fossil systems, defined as a spatially extended X-ray source with an X-ray luminosity from diffuse, hot gas of

![]() erg s-1, represent 8-20% of all systems of the same X-ray luminosity. However, an optical study of a sample of 100+ isolated early-type galaxies found that almost no systems were luminous enough to have been the product of a merger between galaxies brighter than

erg s-1, represent 8-20% of all systems of the same X-ray luminosity. However, an optical study of a sample of 100+ isolated early-type galaxies found that almost no systems were luminous enough to have been the product of a merger between galaxies brighter than ![]() ,

i.e., a merged group (Sulentic et al. 2006). Chandra and XMM-Newton observations of optically selected merger remnants show that their hot gas is X-ray underluminous compared with mature E galaxies into which these merger remnants are expected to evolve (see e.g., Sansom et al. 2000; Rampazzo et al. 2006; Nolan et al. 2004). Brassington et al. (2007), investigating the evolution of X-ray emission during the merger process, similarly found that just after an accretion episode (

,

i.e., a merged group (Sulentic et al. 2006). Chandra and XMM-Newton observations of optically selected merger remnants show that their hot gas is X-ray underluminous compared with mature E galaxies into which these merger remnants are expected to evolve (see e.g., Sansom et al. 2000; Rampazzo et al. 2006; Nolan et al. 2004). Brassington et al. (2007), investigating the evolution of X-ray emission during the merger process, similarly found that just after an accretion episode (![]() 1 Gyr after coalescence) merger remnants are X-ray faint compared to a typical mature E galaxy. They suggested that these systems will start to resemble typical elliptical galaxies at a greater dynamical age (after

1 Gyr after coalescence) merger remnants are X-ray faint compared to a typical mature E galaxy. They suggested that these systems will start to resemble typical elliptical galaxies at a greater dynamical age (after ![]() 3 Gyr), supporting the idea that halo regeneration takes place within low

3 Gyr), supporting the idea that halo regeneration takes place within low ![]() merger remnants.

merger remnants.

Compact galaxy groups generally show modest diffuse X-ray emission (e.g., Trinchieri et al. 2005). However, optically selected structures (such as compact groups) generally tend to be X-ray underluminous in comparison to X-ray selected systems (Rasmussen et al. 2006; Popesso et al. 2007) and consequently the modest diffuse X-ray emission is not necessarily associated with a recent galaxy merger. Rasmussen et al. (2006) found that low level IGM emission could be an indication that the group is in the process of collapsing for the first time. Other possibilities include either that the gravitational potentials are too shallow for the gas to emit substantially in X-rays or that there is simply little of no intra-group gas present in those groups.

We have extended the optical and X-ray studies to isolated physical pairs of galaxies which are simple, and rather common galaxy aggregates in low density environments (LDEs). Among pairs, the mixed E+S binary systems are particularly interesting in the context of an evolutionary accretion scenario (see e.g., Rampazzo & Sulentic 1992; Domingue et al. 2005; Hernandez-Toledo et al. 2001; Domingue et al. 2003), since the luminous E components might be merger products. The study of such relatively simple structures may then shed light on a possible evolutionary link between poor groups and isolated Es. One of the most spectacular examples involves the optical and X-ray bright isolated E+S pair (CPG127=Arp114=NGC2276+2300) with only two known dwarf companions (Davis et al. 1996).

In this context, we initiated an optical and X-ray study of four E+S systems: RR 143, RR 210, RR 216, and RR 242 (Grützbauch et al. 2007, hereafter Paper III). In contrast to their similar optical characteristics, their X-ray properties (see also Trinchieri & Rampazzo 2001) indicate that their X-ray luminosities, ![]() /LB ratios and morphologies are very different, which implies that they have different origins and/or represent different evolutionary stages of the systems. X-ray emission in RR 143 and RR 242 is centred on the elliptical but is much more extended than the optical light.

The emission in RR 143, although centred on the elliptical, shows an asymmetric elongation towards the late-type companion. The total extension is r

/LB ratios and morphologies are very different, which implies that they have different origins and/or represent different evolutionary stages of the systems. X-ray emission in RR 143 and RR 242 is centred on the elliptical but is much more extended than the optical light.

The emission in RR 143, although centred on the elliptical, shows an asymmetric elongation towards the late-type companion. The total extension is r ![]() 500

500

![]() (90

h100-1 kpc). The extended emission from RR 242 is more regular and has an extent of 700

(90

h100-1 kpc). The extended emission from RR 242 is more regular and has an extent of 700

![]() (120

h100-1 kpc). RR 210 and RR 216 show relatively faint and compact (i.e., within the optical galaxy) X-ray emission, consistent with an origin in an evolved stellar population. The emission in RR 143 and RR 242 can be argued to be related to a group potential (as in CPG127) rather than to an individual galaxy. In such a scenario, RR 210 and RR 216 could represent the active part of very poor and loose evolving groups (see e.g., Rampazzo et al. 2006). The activity is reflected by the optically extended and distorted morphologies (see Paper III).

(120

h100-1 kpc). RR 210 and RR 216 show relatively faint and compact (i.e., within the optical galaxy) X-ray emission, consistent with an origin in an evolved stellar population. The emission in RR 143 and RR 242 can be argued to be related to a group potential (as in CPG127) rather than to an individual galaxy. In such a scenario, RR 210 and RR 216 could represent the active part of very poor and loose evolving groups (see e.g., Rampazzo et al. 2006). The activity is reflected by the optically extended and distorted morphologies (see Paper III).

This paper presents results of VLT-VIMOS observations of the faint galaxy populations around the above four RR E+S pairs. Candidates were selected based on their magnitude, (V-R) colour, and size in Paper III. The new observations allow us to determine the redshifts of these faint galaxies and consequently their membership in the E+S systems. These measurements enable us to discuss these groups in the context of previous work by Zabludoff & Mulchaey (1998). They found a significantly higher number of faint galaxies (![]() 20-50 members with

20-50 members with

![]() )

in groups with a significant hot IGM compared to groups without this component. We estimate optical luminosity functions (OLF hereafter) for the combined X-ray bright and X-ray faint groups, respectively, and evaluate them in the context of group evolution (see e.g., Zabludoff & Mulchaey 2000). We also compare the characteristics of the galaxy population in the E+S pairs' environments with those of other X-ray detected groups (see e.g., Tran et al. 2001).

)

in groups with a significant hot IGM compared to groups without this component. We estimate optical luminosity functions (OLF hereafter) for the combined X-ray bright and X-ray faint groups, respectively, and evaluate them in the context of group evolution (see e.g., Zabludoff & Mulchaey 2000). We also compare the characteristics of the galaxy population in the E+S pairs' environments with those of other X-ray detected groups (see e.g., Tran et al. 2001).

The paper is organised as follows. Section 2 describes the VLT-VIMOS observations as well as data reduction techniques. Results are presented in Sect. 3. A discussion of the results in the light of current literature is given in Sect. 4.

Table 1: Log of VIMOS observations.

2 Observations and reduction

The colour selection applied to WIde Field Imager (WFI) images described in Paper III permitted us to isolate a sample of faint galaxies possibly associated with the E+S systems. This sample is referred to as the candidate sample in the following. We summarize briefly the selection criteria used to construct this sample. Galaxy colours were obtained with SExtractor (Bertin et al. 1996). The source extraction was completed for the R-band and V-band images simultaneously, using the same extraction criteria for both bands. The MAG_AUTO output magnitudes from SExtractor were then calibrated using the photometric equations given in Paper III (Sect. 4.2). The colour selection was based on the colour-magnitude relation of the Virgo Cluster (Visvanathan & Sandage 1977), from which the expected location of the red sequence at the pairs' distance was computed. The bright member galaxies in the four groups indeed follow this red sequence or are a bit bluer (see Fig. 12 in Paper III). Fukugita et al. (1995) found from synthetic galaxy colours that the K-correction for a typical elliptical galaxy at

![]() corresponds to a shift in colour of

corresponds to a shift in colour of

![]() mag. Adopting an intrinsic colour of bright ellipticals of

mag. Adopting an intrinsic colour of bright ellipticals of

![]() ,

galaxies with a colour of

(V-R) > 0.9 are already most likely to be in the background. Therefore, for the sake of simplicity, all objects with

,

galaxies with a colour of

(V-R) > 0.9 are already most likely to be in the background. Therefore, for the sake of simplicity, all objects with

![]() were excluded from the candidate sample. We further applied a general magnitude limit of mR = 21, finter than which the star-galaxy classifier of SExtractor becomes unreliable, and a size cut-off at a detected semi-major axis of

were excluded from the candidate sample. We further applied a general magnitude limit of mR = 21, finter than which the star-galaxy classifier of SExtractor becomes unreliable, and a size cut-off at a detected semi-major axis of

![]() (see below). This corresponds to

(see below). This corresponds to

![]() and

and

![]() pc at the distance of the farthest pair (RR 242).

pc at the distance of the farthest pair (RR 242).

The candidates are found all over the WFI images (![]()

![]()

![]() ), although in some fields they show peculiar, e.g., clumpy, distributions (see Fig. 14 in Paper III).

), although in some fields they show peculiar, e.g., clumpy, distributions (see Fig. 14 in Paper III).

To cover the entire WFI field of view and obtain spectra with a signal-to-noise ratio adequate for measuring the redshifts of our faint magnitude candidates, we used VIMOS (VIsible Multi-Object Spectrograph) (Le Fèvre et al. 2003) at the Very Large Telescope (VLT) of ESO located at Cerro

Paranal, Chile. The instrument is mounted on the Nasmyth focus B of UT3 Melipal and has four identical arms, which correspond to the 4 quadrants covering the entire field, each having a field of view of ![]()

![]()

![]() .

The gap between each quadrant is

.

The gap between each quadrant is

![]() .

.

Spectroscopic observations were tailored to derive both the candidate-galaxy redshift and, in a subsequent study, the absorption line-strength indices of member galaxies to investigate their average age and metallicity and infer their star-formation history (see e.g., Grützbauch et al. 2005). We adopted the HR (high resolution) blue grism, which permits the coverage of the spectral region containing the H![]() ,

Mg2, and Fe (

,

Mg2, and Fe (![]() 5270 Å,

5270 Å, ![]() 5335 Å) absorption lines with a resolution of R=2050 (

5335 Å) absorption lines with a resolution of R=2050 (

![]() slit) and a dispersion of 0.51 Å pixel-1. Spectrophotometric and Lick standard-stars were either observed or extracted from the VIMOS data archive with the same instrument set-up. This configuration allows only one slit in the dispersion direction, i.e., each single spectrum covers the full length of the detector. The wavelength interval depends on the slit position. At the CCD centre, the wavelength interval is 4150-6200 Å. At the upper CCD edge (

slit) and a dispersion of 0.51 Å pixel-1. Spectrophotometric and Lick standard-stars were either observed or extracted from the VIMOS data archive with the same instrument set-up. This configuration allows only one slit in the dispersion direction, i.e., each single spectrum covers the full length of the detector. The wavelength interval depends on the slit position. At the CCD centre, the wavelength interval is 4150-6200 Å. At the upper CCD edge (

![]() ), the interval is 4800-6900 Å and 3650-5650 Å at the lower edge (

), the interval is 4800-6900 Å and 3650-5650 Å at the lower edge (![]() ).

).

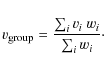

Each WFI field is covered by four VIMOS observing blocks, one VIMOS pointing for each quadrant of the WFI field of view. The observations of each single block were divided into two exposures. Bias, flat-field, and standard-star calibration files were associated with each observing block as well as the helium-argon lamp spectrum for wavelength calibration. Observations were obtained in service mode to guarantee optimal observing conditions. Unfortunately, the complete four quadrants were obtained only for RR 143 and RR 242. Two quadrants were observed for RR 210 and only one for RR 216. Table 1 provides the observing log for the four E+S systems. Figure 1 shows the WFI fields with the results of our VIMOS observations.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{1637f1a.ps}\includegraphics[...

...h=9cm,clip]{1637f1c.ps}\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{1637f1d.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/29/aa11637-09/Timg32.png) |

Figure 1: Results of VIMOS observations superposed on the WFI images: RR 143 ( top left), RR 210 ( top right), RR 216 ( bottom left), and RR 242 ( bottom right). Each field is centred on the bright E galaxy of the pair. Due to an error in the service-mode observations, the field of RR 143 was not dithered and thus shows the gaps between the single CCDs. Each WFI field was covered by 4 VIMOS pointings, one for each quadrant of the WFI field of view. However, not all four quadrants were observed for each group, due to incomplete service-mode observations. Marked with different symbols are: new group members (green circles), confirmed background galaxies (red squares), spectroscopically observed candidates too faint for redshift measurement (blue triangles), and spectroscopically non-observed objects (black diamonds). The newly identified group members are also labelled with their object ID (see Table 3). The different spectroscopic coverage of each field can be seen, since the not-covered quadrants only contain black diamonds. |

The basic CCD reduction of each frame containing spectra as well as the wavelength calibration was completed using the ESO software environment Esorex. The 2D spectrum of each slit was coadded to the corresponding one from the second exposure. The object(s) in each slit was(were) then extracted into 1D object-spectra containing the total light of each target. Finally, each wavelength-calibrated spectrum was stored as a single FITS-file for further processing.

Redshifts were measured using the cross-correlation technique (see e.g., Tonry & Davies 1979). To provide a reliable estimate of radial velocities and their uncertainties, 5 stellar template spectra were used. The IRAF![]() package rvsao provides the xcsao task to measure radial velocities via cross-correlation. During this interactive cross-correlation procedure, the result of the cross-correlation was always directly inspected to avoid spurious results. In some cases, usually for emission-line dominated spectra, the lines could not be identified by xcsao and were processed using the IRAF task splot. With this task a Gaussian fit to each spectral line can be performed. The adopted redshift is then the average of all fitted lines, and its error is given by the standard deviation in the different redshift values.

package rvsao provides the xcsao task to measure radial velocities via cross-correlation. During this interactive cross-correlation procedure, the result of the cross-correlation was always directly inspected to avoid spurious results. In some cases, usually for emission-line dominated spectra, the lines could not be identified by xcsao and were processed using the IRAF task splot. With this task a Gaussian fit to each spectral line can be performed. The adopted redshift is then the average of all fitted lines, and its error is given by the standard deviation in the different redshift values.

Table 2: Observation statistics of the candidate samples.

Table 2 reports the statistics of the observational campaign. For the newly confirmed members of the E+S systems, we obtained accurate surface photometry from our WFI images. The methods adopted are fully explained in Paper III.

3 Results

Redshift measurements allowed us to identify faint galaxies likely to be physically associated with each E+S pair system. However, the spectroscopic coverage of the fields around the four pairs is not uniform, due to incomplete service-mode observations. In spite of two approved observing programs, only

![]() of the total area (the 4 WFI fields) was observed with VIMOS. Additionally, the incompleteness differed between the 4 fields with RR 143 and RR 242 being covered completely, while for RR 210 and RR 216 only 50% and 25%, respectively, of their fields were covered.

of the total area (the 4 WFI fields) was observed with VIMOS. Additionally, the incompleteness differed between the 4 fields with RR 143 and RR 242 being covered completely, while for RR 210 and RR 216 only 50% and 25%, respectively, of their fields were covered.

Figure 2 shows the distribution of measured radial velocities for each field. Each group panel shows the velocity range up to 30 000 km s-1 (![]() 10 times the group velocity), whereas the full range of velocities found up to

10 times the group velocity), whereas the full range of velocities found up to ![]() 130 000 km s-1 is plotted in the small window in the upper right corner of each group panel. Galaxies belonging to each group are shaded in red. To show the group structure in greater detail, we included the already known group members inside the WFI field of view in each histogram. RR 143 (top left panel) and RR 210 (top right panel) show prominent concentrations at

130 000 km s-1 is plotted in the small window in the upper right corner of each group panel. Galaxies belonging to each group are shaded in red. To show the group structure in greater detail, we included the already known group members inside the WFI field of view in each histogram. RR 143 (top left panel) and RR 210 (top right panel) show prominent concentrations at ![]() 40 000 km s-1, while RR 242 (bottom right panel) shows a weaker concentration at

40 000 km s-1, while RR 242 (bottom right panel) shows a weaker concentration at ![]() 16 000 km s-1. Galaxies in the field of RR 216 (bottom left panel) seem to show a less clustered distribution in redshift space. However, only one quadrant of the WFI field was observed with VIMOS in the latter case, resulting in a smaller number of galaxies with measured redshifts than in the other fields (see Table 2).

16 000 km s-1. Galaxies in the field of RR 216 (bottom left panel) seem to show a less clustered distribution in redshift space. However, only one quadrant of the WFI field was observed with VIMOS in the latter case, resulting in a smaller number of galaxies with measured redshifts than in the other fields (see Table 2).

3.1 Identification of faint members and completeness correction

Different membership criteria are considered in the literature. A galaxy is often considered to be a member of a structure if the velocity difference between the galaxy and the structure's systemic velocity is lower than a certain value. For instance, Karachentsev (1990) and Hickson et al. (1992) adopted

![]()

![]() 1000 km s-1, while Ramella et al. (1994) used

1000 km s-1, while Ramella et al. (1994) used ![]() 1500 km s-1. Group membership may also be defined in terms of the group velocity dispersion,

1500 km s-1. Group membership may also be defined in terms of the group velocity dispersion,

![]() ,

leading to a selection that is more capable of being adapted to the true group's properties. In this case, a limit of

,

leading to a selection that is more capable of being adapted to the true group's properties. In this case, a limit of

![]() has been used, reflecting the approximate dynamical boundaries of the group (see e.g., Mulchaey 2000; Firth et al. 2006; Cellone & Buzzoni 2005). Different membership criteria applied to our sample yield the same result: there are no galaxies close to the velocity limits set by the above criteria (the group velocity dispersions used in the flexible group membership criterion are listed in Table 5). Line 6 of Table 2 gives the number of newly identified members for each of our groups. Only a small fraction of the candidates turned out to be new members of our four E+S systems. However, the E+S systems are clearly defined structures in redshift space suggesting that they are real, albeit sparse, physical associations. Coordinates, redshifts with estimated uncertainty, projected distance from the bright E, total R-band magnitude, and (V-R) colour of the new members are presented in Table 3. The structural parameters (Sersic index n, effective radius

has been used, reflecting the approximate dynamical boundaries of the group (see e.g., Mulchaey 2000; Firth et al. 2006; Cellone & Buzzoni 2005). Different membership criteria applied to our sample yield the same result: there are no galaxies close to the velocity limits set by the above criteria (the group velocity dispersions used in the flexible group membership criterion are listed in Table 5). Line 6 of Table 2 gives the number of newly identified members for each of our groups. Only a small fraction of the candidates turned out to be new members of our four E+S systems. However, the E+S systems are clearly defined structures in redshift space suggesting that they are real, albeit sparse, physical associations. Coordinates, redshifts with estimated uncertainty, projected distance from the bright E, total R-band magnitude, and (V-R) colour of the new members are presented in Table 3. The structural parameters (Sersic index n, effective radius ![]() ,

and central and effective surface brightness

,

and central and effective surface brightness ![]() and

and

![]() )

given in the rightmost 4 columns of Table 3 are obtained from one-component Sersic-model fits completed with GALFIT (Peng et al. 2002, see Paper III).

)

given in the rightmost 4 columns of Table 3 are obtained from one-component Sersic-model fits completed with GALFIT (Peng et al. 2002, see Paper III).

Table 3: Summary of the properties of the new members of the E+S systems.

Figure 3 shows the distribution of R-band magnitudes for the candidate list (Paper III), for all objects observed spectroscopically (red), all galaxies with measured redshifts (magenta), and for those adopted as group members (black). Both RR 143 and RR 242, with complete VIMOS pointings, show a reasonable degree of completeness. In contrast, for both RR 210 (2 pointings) and especially RR 216 (1 pointing) the number of candidates without spectroscopy is very high (see also Table 2). In addition to the missing pointings in RR 210 and RR 216, with 50% and 25% coverage, respectively, we must also consider two additional sources of incompleteness affecting the number of spectroscopically observed candidates. The major source of incompleteness is caused by instrumental constraints: (a) the gaps between the 4 CCDs in the VIMOS field of view reduce the analysed area by about 22%, and (b) the HR_blue grism allows only one slit to be placed along the dispersion direction, i.e., galaxies with similar declinations (closer than the slit length) cannot be observed with a single pointing. The second type of incompleteness depends on the source magnitude, i.e., redshifts of fainter objects become increasingly difficult to measure with the adopted exposure times. The magnitude-dependent incompleteness starts at R ![]() 18.5 mag, while at brighter magnitudes the incompleteness is determined by the instrumental constraints. Therefore, a magnitude-limited completeness correction was adopted.

18.5 mag, while at brighter magnitudes the incompleteness is determined by the instrumental constraints. Therefore, a magnitude-limited completeness correction was adopted.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{1637f3.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/29/aa11637-09/Timg62.png) |

Figure 3: Distribution of R-band magnitudes in all 4 group samples: RR 143 ( top left), RR 210 ( top right), RR216 ( bottom left) and RR 242 ( bottom right). The different histograms show the full candidate sample (unshaded), spectroscopically observed galaxies (red, mildly shaded), galaxies with measured redshift (magenta, shaded), and new member galaxies (black, heavily-shaded). They correspond to the samples given in lines 1, 2, 5, and 6 in Table 2. The bin size is 1 mag. |

Our photometric selection criteria (see Sect. 2) may also bias the number of faint member galaxies. When selecting the candidate objects, our first goal was to complete reliably the surface photometry to check if their structural properties are consistent with them being faint galaxies associated with their respective pair. To obtain a reliable estimate of the surface photometric parameters, the galaxy size (or the effective radius) should exceed the size of the seeing disk, which has a

![]() in all images (see Table 4 in Paper III). The detection size a given by SExtractor is not directly related to the galaxy's effective radius or the FWHM, but it gives the semi-major axis length of the detection ellipse, which is most likely larger than the galaxy's effective radius (which contains only half of the light). To ensure that we selected galaxies with effective radii larger than the area affected by the seeing, we chose a generous detection size limit of

in all images (see Table 4 in Paper III). The detection size a given by SExtractor is not directly related to the galaxy's effective radius or the FWHM, but it gives the semi-major axis length of the detection ellipse, which is most likely larger than the galaxy's effective radius (which contains only half of the light). To ensure that we selected galaxies with effective radii larger than the area affected by the seeing, we chose a generous detection size limit of

![]() ,

which corresponds to a physical size of

,

which corresponds to a physical size of ![]() 400 pc at the distance of RR 242. This limit is also reasonable in a physical sense, since it is smaller than the smallest Local Group dwarf galaxies found by Mateo (1998), and reaches the domain of dwarf spheroidal galaxies (dSph), which are typically smaller than 500 pc. Since small galaxies tend to be faint, the size limit leads to incompleteness of the candidate sample at faint magnitudes. Plotting detected size against magnitude, we found that this incompleteness starts at

400 pc at the distance of RR 242. This limit is also reasonable in a physical sense, since it is smaller than the smallest Local Group dwarf galaxies found by Mateo (1998), and reaches the domain of dwarf spheroidal galaxies (dSph), which are typically smaller than 500 pc. Since small galaxies tend to be faint, the size limit leads to incompleteness of the candidate sample at faint magnitudes. Plotting detected size against magnitude, we found that this incompleteness starts at

![]() .

This is also visible in Fig. 3, where the magnitude histogram of the candidate sample bends over at around this magnitude. This incompleteness, however, does not affect galaxies at brighter magnitudes, since we did not exclude any objects brighter than

.

This is also visible in Fig. 3, where the magnitude histogram of the candidate sample bends over at around this magnitude. This incompleteness, however, does not affect galaxies at brighter magnitudes, since we did not exclude any objects brighter than

![]() via this size cut-off. This apparent magnitude corresponds to an absolute magnitude of

via this size cut-off. This apparent magnitude corresponds to an absolute magnitude of

![]() ,

which is the limit to which we compare our results with the literature in the discussion (also because the spectroscopic completeness is higher than 50% for brighter magnitudes, see below). Therefore, we can conclude that our size cut-off does not affect the results we present here.

,

which is the limit to which we compare our results with the literature in the discussion (also because the spectroscopic completeness is higher than 50% for brighter magnitudes, see below). Therefore, we can conclude that our size cut-off does not affect the results we present here.

We adopt a simple completeness-correction criterion based on the assumption that the same fraction of members is present in the sample of spectroscopically observed and not observed objects. The fraction of confirmed members in the sample with measured redshifts is computed for each magnitude bin and multiplied by the number of galaxies in the candidate sample found in the respective bin. This yields the total completeness-corrected number of members in each magnitude bin. The sum over all magnitude bins then gives the corrected number of group members given in line 7 of Table 2. Figure 4 shows the completeness-corrected number of members in each magnitude bin (white histogram) with the true number of confirmed members indicated in red. The number printed above each bin is the percentage of the spectroscopic completeness in the respective bin. So ``100'' means that the completeness is 100% and all candidates in this bin have a measured redshift. If there is no number above a bin then this bin is empty, i.e., there are no candidates within this magnitude range.

Poor statistics in the RR 216 field makes the application of the above criterion very uncertain. We note, e.g., the high number of expected members in the -15 > MR > -16 mag bin: the only candidate with measured redshift in this bin was confirmed as a member. Following the above criterion, all galaxies in the candidate sample at this magnitude were assumed to be members. However, comparing the number of confirmed members with the number of galaxies with measured redshifts (Table 2) also suggests a higher number of member galaxies for RR 216, approaching a number similar to that of the X-ray bright RR 242.

Incompleteness effects are certainly an issue in our sample, although they are not expected to play a major role for absolute magnitudes as faint as

![]() .

Due to instrumental constraints, our spectroscopy missed 3 ``bright'' candidates in RR 143, visible as the 2 first bins labelled with ``0'' in Fig. 4. In all the other groups, the candidates brighter than

.

Due to instrumental constraints, our spectroscopy missed 3 ``bright'' candidates in RR 143, visible as the 2 first bins labelled with ``0'' in Fig. 4. In all the other groups, the candidates brighter than

![]() without measured redshift are accounted for in the completeness correction: 1 object in RR 210 (bin labelled with ``50'', 1 object added by correction), 2 objects in RR 216 (2 bins labelled with ``50'', 2 objects added by correction) and 1 object in RR 242 (bin labelled with ``67'', 1 object added by correction). Figure 4 also shows that, apart from RR 216 (where only one quarter of the field was covered), the spectroscopic completeness is above 50% in all magnitude bins down to

without measured redshift are accounted for in the completeness correction: 1 object in RR 210 (bin labelled with ``50'', 1 object added by correction), 2 objects in RR 216 (2 bins labelled with ``50'', 2 objects added by correction) and 1 object in RR 242 (bin labelled with ``67'', 1 object added by correction). Figure 4 also shows that, apart from RR 216 (where only one quarter of the field was covered), the spectroscopic completeness is above 50% in all magnitude bins down to

![]() .

Any information fainter than this magnitude is not used in the comparison of our results with the literature and does not affect our conclusions.

.

Any information fainter than this magnitude is not used in the comparison of our results with the literature and does not affect our conclusions.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{1637f5.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/29/aa11637-09/Timg71.png) |

Figure 5: Colour-magnitude relation for the candidate samples in the fields of the 4 E+S systems. Members are plotted as red triangles, previously known group members are additionally labelled with their ID (see Figs. 6-9 in Paper III). Spectroscopically observed candidates that were found to be in the background are plotted as green squares, while candidates without measured z are plotted as blue crosses. The solid line is a fit to the red-sequence of the Virgo-Cluster (Visvanathan & Sandage 1977), whereas the dashed vertical line represents the colour cut-off applied to the candidate sample. |

3.2 The photometric and structural properties of faint members

In general, we find that the confirmed companions tend to be of intermediate luminosity, which is a domain populated by faint S0, spirals, and dwarf elliptical galaxies.

Figure 5 shows the colour-magnitude relation of each group. Confirmed member galaxies are indicated by red triangles. The solid line represents a fit to the red sequence of the Virgo Cluster (Visvanathan & Sandage 1977) shifted to the pairs' distance, while the dashed line shows the colour cut-off applied to the candidate sample. Galaxies follow the red sequence for early-type galaxies even at faint magnitudes. The new members have very uniform colours with no blue star-forming dwarfs found in our sample. This might be partially caused by the selection criteria used to construct the candidate sample, especially by the size cut-off. As discussed in Sect. 3.1, this size cut-off leads to the loss of galaxies below

![]() (corresponding to

(corresponding to

![]() at the farthest pair's distance). However, also above that magnitude, where the candidate samples are complete (photometrically), they do not contain blue galaxies. Blue galaxies fainter than

at the farthest pair's distance). However, also above that magnitude, where the candidate samples are complete (photometrically), they do not contain blue galaxies. Blue galaxies fainter than

![]() ,

are not abundant in our sample, but those observed spectroscopically were found to be in the background.

,

are not abundant in our sample, but those observed spectroscopically were found to be in the background.

In the following, we consider only galaxies identified as group members according to the redshift measurements. Figure 6 shows R-band images of new confirmed members. Galaxy morphologies were investigated with ELLIPSE and GALFIT (see Paper III for a full explanation). Results are compared with the galaxy morphologies of the Zabludoff & Mulchaey (2000) X-ray detected groups discussed in Tran et al. (2001).

In Fig. 7, we display residual images after subtraction of a galaxy model constructed from the isophotal fit with ELLIPSE. Different galaxy substructures are clearly visible in the residual images including: asymmetries (RR143_09192, RR242_23187, RR242_25575), bars (RR143_09192, RR216_04052, RR242_22327), filaments (RR242_13326), and shells (RR242_24352). The system of shells in RR242_24352 extends to a radius of ![]() 6

h100-1 kpc and is not aligned (

6

h100-1 kpc and is not aligned (![]() PA

PA ![]() 30

30![]() )

with the semi-major axis of the galaxy. Different formation scenarios for stellar shells have been proposed including weak interactions, accretion of companions and major/minor mergers (see e.g., Hernquist & Quinn 1987b; Dupraz & Combes 1986; Hernquist & Quinn 1987a). In any case, they are considered clear evidence of environmental influence on galaxy evolution, which is apparently found even in rather sparse groups such as those in our sample.

)

with the semi-major axis of the galaxy. Different formation scenarios for stellar shells have been proposed including weak interactions, accretion of companions and major/minor mergers (see e.g., Hernquist & Quinn 1987b; Dupraz & Combes 1986; Hernquist & Quinn 1987a). In any case, they are considered clear evidence of environmental influence on galaxy evolution, which is apparently found even in rather sparse groups such as those in our sample.

Radial profiles of surface brightness (![]() ), ellipticity (

), ellipticity (![]() ), position angle (PA), and higher order coefficients of the Fourier expansion a3, b3, a4, and b4 are shown for each galaxy in Figs. 8 and 9. Isophotal profiles and the GALFIT two-component models (see next paragraph) are shown. Dotted, red lines are Sersic (bulge) and exponential (disk) models, while solid lines represent the resultant total galaxy model. The figures show that the two-component models yield good fits to the real profiles in most cases. There are some residuals for RR242_22327 and RR242_24352, which exhibit very complex structures and are not well represented even by 3 components. The deviations from the model in the outskirts of RR242_22327 are caused by an underestimated ellipticity of the outer isophotes. The ellipticity had to be fixed because of the high percentage of masked area due to some brighter foreground stars in the field. This was also the case for RR143_09192: a foreground star close to the galaxy centre led to the loss of a considerable part of the galaxy image. This galaxy is not included in the B/T analysis in Fig. 10.

), position angle (PA), and higher order coefficients of the Fourier expansion a3, b3, a4, and b4 are shown for each galaxy in Figs. 8 and 9. Isophotal profiles and the GALFIT two-component models (see next paragraph) are shown. Dotted, red lines are Sersic (bulge) and exponential (disk) models, while solid lines represent the resultant total galaxy model. The figures show that the two-component models yield good fits to the real profiles in most cases. There are some residuals for RR242_22327 and RR242_24352, which exhibit very complex structures and are not well represented even by 3 components. The deviations from the model in the outskirts of RR242_22327 are caused by an underestimated ellipticity of the outer isophotes. The ellipticity had to be fixed because of the high percentage of masked area due to some brighter foreground stars in the field. This was also the case for RR143_09192: a foreground star close to the galaxy centre led to the loss of a considerable part of the galaxy image. This galaxy is not included in the B/T analysis in Fig. 10.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=17.5cm,clip]{1637f7.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/29/aa11637-09/Timg76.png) |

Figure 7: Residual images after subtraction of a model constructed from the isophotal fit with ELLIPSE. Objects are shown in the same order and with the same scale as in Fig. 6. |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=16.5cm,clip]{1637f9.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/29/aa11637-09/Timg78.png) |

Figure 9: Surface photometry as in Fig. 8. Objects shown are RR242_15689, RR242_20075, RR242_22327, RR242_23187, RR242_24352, RR242_25575, RR242_28727, and RR242_36267. |

The morphological classification listed in Table 4 was completed using the surface photometric profiles in Figs. 8 and 9. The presence of bulge and disk components is clearly evident as a bend in the surface-brightness profile at the transition between the two components, due to the different shapes of the radial surface-brightness profiles of spheroids and disks. The surface brightness ![]() declines with radius as

declines with radius as

![]() .

Disks (and dwarf ellipticals) have an exponential profile with

.

Disks (and dwarf ellipticals) have an exponential profile with ![]() ,

whereas spheroids are characterised by a higher value of n. Additionally, a disk is characterised by a constant

,

whereas spheroids are characterised by a higher value of n. Additionally, a disk is characterised by a constant ![]() and PA, whereas along the bulge, both

and PA, whereas along the bulge, both ![]() and PA can vary. In this way, ellipticals (being pure bulges) and lenticular galaxies (having a bulge and a disk) can be distinguished easily. Bars can also be identified in the surface photometric profiles, showing a constant surface brightness and PA in combination with a high

and PA can vary. In this way, ellipticals (being pure bulges) and lenticular galaxies (having a bulge and a disk) can be distinguished easily. Bars can also be identified in the surface photometric profiles, showing a constant surface brightness and PA in combination with a high ![]() .

We find a number of bars in our faint galaxy sample. In 5/17 objects a bar is clearly distinguishable in the radial profiles. A weak bar is also suspected in (RR242_25575). Bars can also be an indication of on-going interaction as shown by Noguchi (1987).

.

We find a number of bars in our faint galaxy sample. In 5/17 objects a bar is clearly distinguishable in the radial profiles. A weak bar is also suspected in (RR242_25575). Bars can also be an indication of on-going interaction as shown by Noguchi (1987).

In order to investigate the bulge-to-total light (B/T) ratios a bulge-disk decomposition was attempted with GALFIT (Peng et al. 2002). Tran et al. (2001) found that the galaxy population of poor X-ray detected groups was well described by a 2-component model composed of a de Vaucouleurs bulge (

![]() )

and an exponential disk (

)

and an exponential disk (

![]() ). However, the shape of the profile determined by the exponent 1/n is supposed to vary significantly with mass. This is valid not only for low-mass ellipticals but also for the bulges of low-mass galaxies, which are expected to show a different profile shape, i.e., a lower n. Both bulge/disk combinations with n=4 (de Vaucouleurs bulge) and n as a free parameter (Sersic bulge) were fit to our member galaxies to investigate differences between these two models. Bulge and disk magnitudes as well as B/T ratios for the two different models can be found in Table 4. Differences in B/T can be significant especially for bulge-dominated galaxies. The difference between the

). However, the shape of the profile determined by the exponent 1/n is supposed to vary significantly with mass. This is valid not only for low-mass ellipticals but also for the bulges of low-mass galaxies, which are expected to show a different profile shape, i.e., a lower n. Both bulge/disk combinations with n=4 (de Vaucouleurs bulge) and n as a free parameter (Sersic bulge) were fit to our member galaxies to investigate differences between these two models. Bulge and disk magnitudes as well as B/T ratios for the two different models can be found in Table 4. Differences in B/T can be significant especially for bulge-dominated galaxies. The difference between the

![]() of the two-component fits from GALFIT is given in the last column of Table 4. We find that the Sersic bulge provides an accurate representation of faint galaxy bulges: apart from one galaxy (RR242_28727), the Sersic fit always has a lower

of the two-component fits from GALFIT is given in the last column of Table 4. We find that the Sersic bulge provides an accurate representation of faint galaxy bulges: apart from one galaxy (RR242_28727), the Sersic fit always has a lower

![]() than the de Vaucouleurs fit. The de Vaucouleurs fits of RR143_09192, RR210_13493, RR242_24352 and RR242_36267 are unsatisfactory, while RR242_23187 was fitted badly by the Sersic model.

than the de Vaucouleurs fit. The de Vaucouleurs fits of RR143_09192, RR210_13493, RR242_24352 and RR242_36267 are unsatisfactory, while RR242_23187 was fitted badly by the Sersic model.

Figures 8 and 9 show the results of the Sersic-model fit and the observed surface-brightness profile in the R-band. The dotted, red lines represent the bulge and disk model, respectively. A model for the bar was added for the brighter bars. The solid line represents the resulting galaxy model.

Figure 10 (top panel) shows the distribution of B/T ratios for Sersic (black, shaded) and de Vaucouleurs models (red, dotted line). Both distributions show that our sample is dominated by low B/T - i.e., disk-dominated - galaxies. An automatic classification by the B/T ratio was proposed by Marleau & Simard (1998) and also used by Tran et al. (2001). This automatic classification divides late (S, disk-dominated) and early-type (S0 and E, bulge-dominated) galaxies at B/T = 0.4. This may work in distinguishing between bright E and S galaxies, but is problematic for faint S0 galaxies. A comparison between visual (based on surface photometric profiles) and automatic classification (based on the B/T ratio) shows the problem: visually classified S0 galaxies show a wide range of B/T ratios and are not necessarily bulge-dominated systems. We found a high fraction of S0s from our visual classification (7 out of 17, 40%), but only 3 of those galaxies have a B/T ![]() 0.4 (18%). This would yield an early-type fraction similar to that of the field, while the visually estimated S0-fraction is more typical of galaxy clusters and X-ray luminous galaxy groups (Tran et al. 2001, and references therein).

0.4 (18%). This would yield an early-type fraction similar to that of the field, while the visually estimated S0-fraction is more typical of galaxy clusters and X-ray luminous galaxy groups (Tran et al. 2001, and references therein).

Figure 10 (middle panel) plots B/T ratios versus the projected distance from the dominant E member. The individual galaxies are plotted as small dots, while the mean and dispersion are computed in bins of 30

h100-1 kpc and plotted as open circles with respective error bars (red - de Vaucouleurs bulge; black - Sersic bulge). The lines are a least squares fit to the individual data points (solid black line - Sersic; dashed, red line - de Vaucouleurs). A morphology-radius relation appears to be present in our sample: galaxies with higher B/T ratios tend to be more centrally concentrated than pure disks. This result was also found for the groups studied by Tran et al. (2001). However, the relation is very flat and the scatter is large, probably due to projection effects and the small number of galaxies studied. We computed Spearman rank coefficients for the two data sets resulting in

![]() and

and

![]() ,

values that are not considered to be statistically significant.

,

values that are not considered to be statistically significant.

The bottom panel of Fig. 10 shows the dependence of B/T on the local projected number density. This local density was computed using the distance to the 5th (d5) and 3rd (d3) closest group member. The results are plotted as circles (d5) and triangles (d3), and in black and red for Sersic and de Vaucouleurs bulges, respectively. The lines are the least squares fit to the data of d5 (dashed-dotted - Sersic; red dashed - de Vaucouleurs) and d3 (long-dashed - Sersic; red short-dashed - de Vaucouleurs). Using only the area occupied by the 3 closest galaxies changes the results slightly but significantly: the correlation for d5 is stronger than for d3, the Spearman rank coefficients being

![]() and

and

![]() .

For our sample size (16 galaxies), the latter value is higher than the critical value of

.

For our sample size (16 galaxies), the latter value is higher than the critical value of ![]() at the 0.05 (2

at the 0.05 (2![]() )

level of significance. Hence, there seems to be a positive correlation between the projected number density (d5) and the morphology (expressed by the B/T ratio).

)

level of significance. Hence, there seems to be a positive correlation between the projected number density (d5) and the morphology (expressed by the B/T ratio).

The Hamabe-Kormendy Relation (Hamabe & Kormendy 1987, HKR hereafter) in the

![]() plane is one projection of the Fundamental Plane for early-type galaxies. Faint Es, S0s, or dwarf ellipticals (dEs) do not follow this relation but are distributed in the

plane is one projection of the Fundamental Plane for early-type galaxies. Faint Es, S0s, or dwarf ellipticals (dEs) do not follow this relation but are distributed in the

![]() plane below the HKR and also below

plane below the HKR and also below

![]() kpc. They are considered a distinct family of galaxies, the so-called ordinary galaxies, whereas galaxies above

kpc. They are considered a distinct family of galaxies, the so-called ordinary galaxies, whereas galaxies above

![]() kpc belong to the family of bright ellipticals (Capaccioli et al. 1992). The ordinary family are often considered to be the building blocks of galaxies of the bright family, although more recent simulations of Evstigneeva et al. (2004) show that by merging, the galaxies evolve along tracks that are parallel to the HKR.

kpc belong to the family of bright ellipticals (Capaccioli et al. 1992). The ordinary family are often considered to be the building blocks of galaxies of the bright family, although more recent simulations of Evstigneeva et al. (2004) show that by merging, the galaxies evolve along tracks that are parallel to the HKR.

The

![]() plane for our four E+S groups is shown in Fig. 11 with the dashed line indicating the HKR (in the R-band). The dotted line at

plane for our four E+S groups is shown in Fig. 11 with the dashed line indicating the HKR (in the R-band). The dotted line at

![]() separates the bright and ordinary families (Capaccioli et al. 1992). The four bright Es lie on the HKR clearly in the bright galaxy domain, while the newly identified faint members are distributed in the

separates the bright and ordinary families (Capaccioli et al. 1992). The four bright Es lie on the HKR clearly in the bright galaxy domain, while the newly identified faint members are distributed in the

![]() plane below the limit of ordinary galaxies. The brightest galaxy of the newly discovered galaxy population RR242_24352 is closest to the HKR, while the faintest galaxies are off the relation in the expected vertical strip of ordinary galaxies (Capaccioli et al. 1992).

plane below the limit of ordinary galaxies. The brightest galaxy of the newly discovered galaxy population RR242_24352 is closest to the HKR, while the faintest galaxies are off the relation in the expected vertical strip of ordinary galaxies (Capaccioli et al. 1992).

Table 4: Results of the Bulge-disk decomposition.

3.3 The spectral properties of faint members

VIMOS spectra of the new member galaxies are presented in Figs. 12 and 13. As already suggested by the colour-magnitude relation, the spectra are characterised by a relatively old stellar population. Strong metal lines (Mg I and Fe) are present in most of the spectra, although many also exhibit strong H![]() absorption suggesting the presence of a younger or intermediate-age population. Emission lines are detected in only two galaxies; RR242_23187, where H

absorption suggesting the presence of a younger or intermediate-age population. Emission lines are detected in only two galaxies; RR242_23187, where H![]() and H

and H![]() emission suggests recent or ongoing star-formation activity, and RR143_24246, where [O II]

emission suggests recent or ongoing star-formation activity, and RR143_24246, where [O II] ![]() 3727-29 Å emission is detected. The forbidden lines of [O III]

3727-29 Å emission is detected. The forbidden lines of [O III] ![]() 4959 Å and

4959 Å and ![]() 5007 Å as well as H

5007 Å as well as H![]() emission is present in both galaxies, although on top of a substantial absorption component. The detailed analysis of the line-strength indices (see e.g., Rampazzo et al. 2005; Grützbauch et al. 2005; Annibali et al. 2007) will be treated in a forthcoming paper.

emission is present in both galaxies, although on top of a substantial absorption component. The detailed analysis of the line-strength indices (see e.g., Rampazzo et al. 2005; Grützbauch et al. 2005; Annibali et al. 2007) will be treated in a forthcoming paper.

4 Discussion

In the following discussion, we consider only the spectroscopically confirmed member galaxies. Their basic properties are summarised in Table 3. The new members are used, along with the previously known group members (see Paper III), to infer group properties. Table A.1 lists all known members of the groups: i.e., new members found within the WFI field of view and already known members found in the NASA/IPAC Extragalactic Database (NED). To investigate the effects of the WFI's small field of view, we compare velocity and magnitude distributions of the full sample (90![]() )

and the WFI subsample (34

)

and the WFI subsample (34![]()

![]() 34

34![]() ).

).

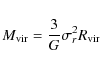

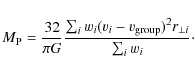

Group kinematics and dynamics are discussed in the first section using a luminosity-weighted approach for the determination of all mass-related quantities (see e.g., Firth et al. 2006). However, we also compute uniformly weighted quantities and discuss the results of the different weighting. The dynamical formulae are given in the Appendix. Distribution of members, group compactness, crossing times, and mass-to-light ratios are analysed and compared with the literature. OLFs of the individual and combined group samples are presented in the next section. The OLFs of our X-ray faint and X-ray bright groups are compared with OLFs for samples of: 1) X-ray detected poor groups; 2) simulated and observed fossil groups; and 3) the OLF of the local field. We then attempt to investigate the possible relation between the group dynamical characteristics as well as the group ``activity'' and the X-ray luminosity of the E members.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{1637f11.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/29/aa11637-09/Timg99.png) |

Figure 11: Hamabe-Kormendy relation (Hamabe & Kormendy 1987, dashed line) for new group member galaxies. The pair ellipticals are also plotted for comparison. All galaxies are labelled with their ID. The area left of the vertical dotted line represents the region inhabited by ``ordinary'' galaxies (see Capaccioli et al. 1992). |

4.1 The E+S system kinematics and dynamics

Distributions of radial velocities for the full sample and the WFI-subsample (red-dashed) are shown in Fig. 14. The

![]() of each sample is plotted as a vertical, dashed line, while the horizontal line above each histogram indicates the 3

of each sample is plotted as a vertical, dashed line, while the horizontal line above each histogram indicates the 3![]() limits as an approximate dynamical boundary for each group. The mean velocities of the two samples do not differ significantly, apart from RR 216, where the velocity of the WFI-subsample is dominated by the very bright pair elliptical (no other bright members are present in the WFI-field) and is therefore biased towards a higher value. For this group, the group velocity for the full sample is

limits as an approximate dynamical boundary for each group. The mean velocities of the two samples do not differ significantly, apart from RR 216, where the velocity of the WFI-subsample is dominated by the very bright pair elliptical (no other bright members are present in the WFI-field) and is therefore biased towards a higher value. For this group, the group velocity for the full sample is

![]()

![]() 49 versus

49 versus

![]()

![]() 24 km s-1 for galaxies in the WFI field of view. The unweighted velocity dispersions of the two samples are comparable within the errors for all four systems. The luminosity-weighting significantly changes the velocity dispersion only in RR 216 where the velocity difference between the 2 dominating pair galaxies is very small, biasing the dispersion within the WFI field towards a low value (

24 km s-1 for galaxies in the WFI field of view. The unweighted velocity dispersions of the two samples are comparable within the errors for all four systems. The luminosity-weighting significantly changes the velocity dispersion only in RR 216 where the velocity difference between the 2 dominating pair galaxies is very small, biasing the dispersion within the WFI field towards a low value (

![]()

![]() 35 versus

35 versus

![]()

![]() 18 km s-1).

18 km s-1).

The peculiar velocity is the difference between an individual galaxy velocity and the group centre velocity (

![]() ). It is usually normalised by the group's velocity dispersion for comparison with other groups (see e.g., Zabludoff & Mulchaey 2000). Figure 15 shows the peculiar velocities of galaxies versus their projected radial distance from the optical group centre. The group members are separated into giants (big symbols) and dwarfs (small symbols) following Zabludoff & Mulchaey (2000). Galaxies with absolute magnitudes brighter than

). It is usually normalised by the group's velocity dispersion for comparison with other groups (see e.g., Zabludoff & Mulchaey 2000). Figure 15 shows the peculiar velocities of galaxies versus their projected radial distance from the optical group centre. The group members are separated into giants (big symbols) and dwarfs (small symbols) following Zabludoff & Mulchaey (2000). Galaxies with absolute magnitudes brighter than

![]() are considered giants, and fainter objects are defined as dwarfs. The four group samples are combined in analysing the dependence of velocity dispersion on the projected distance. The mean velocity and velocity dispersion is computed in radial bins of 100

h100-1 kpc. They are plotted as red squares (mean velocity) and respective red error bars (velocity dispersion) for each bin.

are considered giants, and fainter objects are defined as dwarfs. The four group samples are combined in analysing the dependence of velocity dispersion on the projected distance. The mean velocity and velocity dispersion is computed in radial bins of 100

h100-1 kpc. They are plotted as red squares (mean velocity) and respective red error bars (velocity dispersion) for each bin.

Figure 15 suggests that the velocity dispersion is not constant with projected radius. The maximal dispersion is reached at around 0.2

h100-1 Mpc (![]() the border of the WFI field of view), from where it starts to decrease out to

the border of the WFI field of view), from where it starts to decrease out to ![]() 0.5

h100-1 Mpc. At greater radii, the dispersion rises again, which could indicate the transition between the potential of the group concentrated around the E and the influence of the global large-scale density. We computed the statistical errors in the velocity dispersion in each bin following Osmond & Ponman (2004, their Eq. (4)). The

0.5

h100-1 Mpc. At greater radii, the dispersion rises again, which could indicate the transition between the potential of the group concentrated around the E and the influence of the global large-scale density. We computed the statistical errors in the velocity dispersion in each bin following Osmond & Ponman (2004, their Eq. (4)). The

![]() and

and

![]() quoted below are normalised velocity dispersions obtained by dividing the peculiar galaxy velocities by the respective group's velocity dispersion. The maximum of

quoted below are normalised velocity dispersions obtained by dividing the peculiar galaxy velocities by the respective group's velocity dispersion. The maximum of ![]() at 0.15

h100-1 Mpc is

at 0.15

h100-1 Mpc is

![]()

![]() 0.20, while the minimum at 0.45

h100-1 Mpc is

0.20, while the minimum at 0.45

h100-1 Mpc is

![]()

![]() 0.14. Hence, the velocity dispersion is not constant within the errors. However, this is a tentative result due to the intrinsically low number of members in our groups.

0.14. Hence, the velocity dispersion is not constant within the errors. However, this is a tentative result due to the intrinsically low number of members in our groups.

To investigate the effect of incompleteness and low number statistics in our sample, a set of Monte Carlo simulations was performed. The question is whether the detected drop in velocity dispersion is significant, or if our measured ![]() cannot be distinguished from a constant velocity dispersion. Therefore, in each radial bin a Gaussian velocity distribution of the same

cannot be distinguished from a constant velocity dispersion. Therefore, in each radial bin a Gaussian velocity distribution of the same ![]() (the maximum velocity dispersion found in the second radial bin:

(the maximum velocity dispersion found in the second radial bin:

![]() )

was assumed. Then, a random sample of n velocities was taken from this Gaussian distribution, where n represents the number of galaxies of our sample in the respective bin. After 1000 iterations, the mean velocity and velocity dispersion and their deviations in each bin was computed. The

)

was assumed. Then, a random sample of n velocities was taken from this Gaussian distribution, where n represents the number of galaxies of our sample in the respective bin. After 1000 iterations, the mean velocity and velocity dispersion and their deviations in each bin was computed. The ![]() deviations are plotted in Fig. 15 as grey (mean velocity) and red (velocity dispersion) shaded areas. The result is that the mean velocity is consistent with the group velocity in all bins, whereas the velocity dispersion is lower than the expected

deviations are plotted in Fig. 15 as grey (mean velocity) and red (velocity dispersion) shaded areas. The result is that the mean velocity is consistent with the group velocity in all bins, whereas the velocity dispersion is lower than the expected ![]() deviation from the constant value in all bins out to 0.5

h100-1 Mpc. If the velocity dispersion were constant, the error bars would reach into the red shaded area. This result is significant at

deviation from the constant value in all bins out to 0.5

h100-1 Mpc. If the velocity dispersion were constant, the error bars would reach into the red shaded area. This result is significant at

![]() in the bin between 0.4-0.5

h100-1 Mpc. We repeated this analysis with different radial binnings (75, 100, and 150

h100-1 kpc) and the drop in velocity dispersion was always above the 1

in the bin between 0.4-0.5

h100-1 Mpc. We repeated this analysis with different radial binnings (75, 100, and 150

h100-1 kpc) and the drop in velocity dispersion was always above the 1![]() significance level. We therefore suggest that the velocity dispersion decreases with radius and that the kinematics in the region outside 0.5

h100-1 Mpc may not trace the group potential (as traced by the IGM). The dynamical quantities were also calculated by excluding galaxies lying outside this radius.

significance level. We therefore suggest that the velocity dispersion decreases with radius and that the kinematics in the region outside 0.5

h100-1 Mpc may not trace the group potential (as traced by the IGM). The dynamical quantities were also calculated by excluding galaxies lying outside this radius.

Another interesting implication of Fig. 15 is that the position of the bright E+S pair does not coincide with the optical centre of each group. The projected offsets for RR 216, RR 242, and RR 143 are around 0.1 h100-1 Mpc, and only RR 210 is located very close to the projected group centre.

The R-statistic was developed by Zabludoff & Mulchaey (2000) to facilitate comparison between the distribution of members in both projection and velocity space. It is defined as

![]() ,

where

,

where ![]() and

and

![]() denotes the rms deviations of the entire sample in projected distance and peculiar velocity, respectively. A galaxy with a large distance d from the group centre or a large peculiar velocity

denotes the rms deviations of the entire sample in projected distance and peculiar velocity, respectively. A galaxy with a large distance d from the group centre or a large peculiar velocity

![]() will yield a high value of R, while an average member should have

will yield a high value of R, while an average member should have ![]() .

We compared the distribution of R values for three magnitude-limited subsamples: 1) the brightest group galaxies (BGGs) with

.

We compared the distribution of R values for three magnitude-limited subsamples: 1) the brightest group galaxies (BGGs) with

![]() ;

2) giants with

;

2) giants with

![]() ;

and 3) dwarfs. We also compared the full sample with galaxies within 0.5

h100-1 Mpc of the group centre. Figure 15 (bottom panels) shows the distribution of R for the BGGs (heavily shaded), giants (shaded), and dwarfs (unshaded) in the full sample (left panel) and for the galaxies within 0.5

h100-1 Mpc (right panel). In both samples, the BGGs are more centrally concentrated than dwarfs and giants with

;

and 3) dwarfs. We also compared the full sample with galaxies within 0.5

h100-1 Mpc of the group centre. Figure 15 (bottom panels) shows the distribution of R for the BGGs (heavily shaded), giants (shaded), and dwarfs (unshaded) in the full sample (left panel) and for the galaxies within 0.5

h100-1 Mpc (right panel). In both samples, the BGGs are more centrally concentrated than dwarfs and giants with

![]()

![]() 0.7 and

0.7 and

![]()

![]() 0.8. Considering the full sample, the dwarf population follows a different distribution in phase-space than the giants with

0.8. Considering the full sample, the dwarf population follows a different distribution in phase-space than the giants with

![]()

![]() 0.9 and

0.9 and

![]()

![]() 1.1.

1.1.

A K-S test is used to check whether the R distributions of the three subsamples differ significantly. It gives the following probabilities that the 3 distributions are the same:

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

and

,

and

![]() .

Those values are significant above the 1

.

Those values are significant above the 1![]() level. Inside the 0.5

h100-1 Mpc radius, the difference between dwarfs and giants vanishes (both have

level. Inside the 0.5

h100-1 Mpc radius, the difference between dwarfs and giants vanishes (both have

![]() ), but the R distributions of BGGs and dwarfs have a probability of originating in the same distribution of

), but the R distributions of BGGs and dwarfs have a probability of originating in the same distribution of

![]() .

This suggests that the 2 distributions are different above the 2

.

This suggests that the 2 distributions are different above the 2![]() significance level. This is not only caused by the optical group centre moving closer to the BGGs, since both,

significance level. This is not only caused by the optical group centre moving closer to the BGGs, since both,

![]() and

and

![]() are higher than the respective values for the full sample.

are higher than the respective values for the full sample.

These findings are consistent with the results of Zabludoff & Mulchaey (2000), who argued that the three galaxy populations (BGGs, giants, dwarfs) move on different orbits and have not yet mixed. From the present data, this also seems to be the case for the BGGs and dwarfs at the centres of our 4 groups, although we note that outside the WFI field of view we lack information about faint member galaxies.

The dynamical properties of the four E+S systems are given in Table 5, where the first row provides data for the entire sample and the second row for group members inside a radius of 0.5

h100-1 Mpc. Errors were estimated using Monte Carlo simulations. For velocity-related quantities (

![]() ,

velocity dispersion), a Gaussian distribution was assumed. A set of 1000 groups with the respective number of members was constructed for both the full sample and galaxies within 0.5

h100-1 Mpc (see Appendix A). Each of these groups consisted of galaxies with velocities that were taken randomly from a Gaussian distribution of respective mean velocity and dispersion given in Table 5. The rms of the mean velocity and velocity dispersion of this set of groups is the error given in Table 5. The position and luminosity related quantities were treated in a different way. Here, the number of additional galaxies expected from the completeness correction was added to the existing group. These additional galaxies were selected randomly from the sample of candidates without a measured redshift. After 1000 iterations, the rms of the values (

,

velocity dispersion), a Gaussian distribution was assumed. A set of 1000 groups with the respective number of members was constructed for both the full sample and galaxies within 0.5

h100-1 Mpc (see Appendix A). Each of these groups consisted of galaxies with velocities that were taken randomly from a Gaussian distribution of respective mean velocity and dispersion given in Table 5. The rms of the mean velocity and velocity dispersion of this set of groups is the error given in Table 5. The position and luminosity related quantities were treated in a different way. Here, the number of additional galaxies expected from the completeness correction was added to the existing group. These additional galaxies were selected randomly from the sample of candidates without a measured redshift. After 1000 iterations, the rms of the values (![]() ,

,

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

group luminosity) of this set of ``complete'' groups were computed. The errors in virial mass

,

group luminosity) of this set of ``complete'' groups were computed. The errors in virial mass

![]() ,

projected mass

,

projected mass ![]() ,

and crossing time

,

and crossing time ![]() are a combination of this two methods, since they are dependent on velocity and position of the objects.

are a combination of this two methods, since they are dependent on velocity and position of the objects.

Both luminosity-weighted and uniformly-weighted results are provided in Table 5. Different weightings influence the results dramatically, and especially in RR 210 where the parameters of the bright pair dominate the resulting values. The pair components are separated by a projected distance of only 6

h100-1 kpc and are close to the centres of both mass and velocity. This leads to an underestimation of

![]() and a very low luminosity-weighted value of M/L for this pair.

and a very low luminosity-weighted value of M/L for this pair. ![]() and

and

![]() rise by an order of magnitude if the members are uniformly weighted. Values change by a factor of

rise by an order of magnitude if the members are uniformly weighted. Values change by a factor of ![]() 2 for the other systems. The group velocity and velocity dispersion are less affected by the weighting. Weights given in Table A.1 illustrate the dominance of the E member. RR 143a and RR 210a contribute more than 50% to the total luminous mass, while the spiral companion is clearly the second brightest object. RR 216b and RR 242a contain about 1/3 of the luminous mass and have a few other massive objects brighter or comparable to the spiral pair member in their close environment. The unweighted value of

2 for the other systems. The group velocity and velocity dispersion are less affected by the weighting. Weights given in Table A.1 illustrate the dominance of the E member. RR 143a and RR 210a contribute more than 50% to the total luminous mass, while the spiral companion is clearly the second brightest object. RR 216b and RR 242a contain about 1/3 of the luminous mass and have a few other massive objects brighter or comparable to the spiral pair member in their close environment. The unweighted value of ![]() for RR 216 is very high and indicative of a higher large-scale density in which this pair is embedded and a probable dynamical link to the Hydra-Centaurus cluster. However, it also means that the brighter members are more concentrated towards the pair than the intermediate-luminosity galaxies.