| Issue |

A&A

Volume 501, Number 1, July I 2009

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Page(s) | 359 - 366 | |

| Section | Planets and planetary systems | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/200911790 | |

| Published online | 29 April 2009 | |

Periodic variation in the water production of comet C/2001 Q4 (NEAT)

observed with the Odin satellite![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

N. Biver1 - D. Bockelée-Morvan1 - P. Colom1 - J. Crovisier1 - A. Lecacheux1 - U. Frisk2 - Å. Hjalmarson3 - M. Olberg3 - Aa. Sandqvist4

1 - LESIA, CNRS UMR 8109, Observatoire de Paris, 5 pl. Jules Janssen, 92195 Meudon, France

2 - Swedish Space Corporation, PO Box 4207, 17104 Solna, Sweden

3 - Onsala Space Observatory, 43992 Onsala, Sweden

4 - Stockholm Observatory, SCFAB-AlbaNova, 10691 Stockholm, Sweden

Received 4 February 2009 / Accepted 21 March 2009

Abstract

Context. Comet C/2001 Q4 (NEAT) was extensively studied with the 1.1-m submillimetre telescope of the Odin satellite. The H2O line at 557 GHz was regularly observed from 6 March to 16 May 2004 and nearly continuously monitored during 3 periods between 26 April and 2 May 2004.

Aims. This last set of data shows periodic variations in the line intensity, and we looked for characterising the long- and short-term behaviour of this comet.

Methods. We used the variance ratio method and ![]() minimization to find the period of variation in the water production rate and simulations to infer its amplitude at the nucleus surface.

minimization to find the period of variation in the water production rate and simulations to infer its amplitude at the nucleus surface.

Results. A 40% periodic variation in the water production rate is measured with a period of

![]() day (

day (

![]() h). The comet also exhibits a seasonal effect with a mean peak of outgassing around

h). The comet also exhibits a seasonal effect with a mean peak of outgassing around

![]() molec. s-1 taking place about 18 days before perihelion.

molec. s-1 taking place about 18 days before perihelion.

Key words: astrochemistry - comets: general - comets: individual: C/2001 Q4 (NEAT) - radio lines: solar system - submillimetre

1 Introduction

Comets are the most pristine objects of the Solar System. Cometary nuclei formed and remained far from the Sun, and the molecular inventory of their ices is believed to reflect that of the primordial Solar Nebula in the region where they agglomerated. Water is the main constituent of the ices of cometary nuclei (Festou et al. 2004, and references therein). The study of cometary water is thus crucial for cometary science. Measurements of water production rates allow us to determine the relative abundances of cometary volatiles, whose production rates are measured at the same time. The Odin satellite (Nordh et al. 2003; Frisk et al. 2003) was launched on 20 February 2001 on a Sun-synchronous polar orbit. Odin houses a radiometer with a 1.1-m primary mirror and five receivers at 119 GHz, 486-504 GHz, and 541-580 GHz, which are frequencies that are in large part unobservable from the ground. The H2O (110-101) fundamental line of water at 556.936 GHz is one of the strongest cometary lines, but it cannot be observed from the ground. Its observation in comets has been a major observing topic for Odin. Previous observations of this line in comets have been reported in Neufeld et al. (2000), Lecacheux et al. (2003), and Biver et al. (2007a).

C/2001 Q4 (NEAT) is a dynamically new Oort-cloud comet that came

to perihelion on 16 May 2004 at 0.96 AU. It was one of the brightest comets

of 2004 and it reached a visual magnitude of m1=3.3 in early May 2004,

as reported by amateur astronomers in the International Comet Quarterly![]() .

It has been extensively studied from the ground, especially starting

in May 2004 since earlier it was a southern object. Odin monitored its

outgassing rate in advance of these observing campaigns. This comet was also

active enough that three molecular lines,

H2O(110-101) at 557 GHz, H218O(110-101) at 548 GHz,

and NH3(10-00) at 572 GHz were detected

around perigee (0.34 AU on 7 May), as reported in Biver et al. (2007a).

The water line was also mapped on 16 May 2004.

.

It has been extensively studied from the ground, especially starting

in May 2004 since earlier it was a southern object. Odin monitored its

outgassing rate in advance of these observing campaigns. This comet was also

active enough that three molecular lines,

H2O(110-101) at 557 GHz, H218O(110-101) at 548 GHz,

and NH3(10-00) at 572 GHz were detected

around perigee (0.34 AU on 7 May), as reported in Biver et al. (2007a).

The water line was also mapped on 16 May 2004.

The investigation of the rotation of cometary nuclei has been done in various ways. Samarasinha et al. (2004) summarises the recent results and the interest of determining rotation properties of cometary nuclei. In this paper we focus on the observations of the H2O 557 GHz line performed in comet C/2001 Q4 (NEAT) from 6 March to 16 May 2004. They reveal periodic variations in the outgassing linked to the nucleus rotation.

2 Observations

Odin orbits the Earth in 1.6 h. Sixty-three orbits were dedicated

to this comet, corresponding to about

![]() h observations.

About 6 of these are not useful since Odin

did not achieve a stable tracking of the comet. (It pointed between 1'

and 6

h observations.

About 6 of these are not useful since Odin

did not achieve a stable tracking of the comet. (It pointed between 1'

and 6![]() off the comet.)

One to three receivers aboard Odin were used simultaneously.

Three different set-ups were used for the periods 6 March to 13 April [1],

26 April to 2 May [2] and 15-16 May [3]:

off the comet.)

One to three receivers aboard Odin were used simultaneously.

Three different set-ups were used for the periods 6 March to 13 April [1],

26 April to 2 May [2] and 15-16 May [3]:

- The ``555B2'' receiver was tuned to the H2O line at 556.936 GHz and connected to the accousto-optical spectrometer (AOS) with a resolution of 1.0 MHz (0.54 km s-1) and sampling of 0.6 MHz all the time. It was also connected to the AC2 autocorrelator, with an effective resolution of 202 kHz, during periods [1] and [3].

- The ``549A1'' receiver was also tuned to the H2O line at 556.936 GHz and connected to the AC1 autocorrelator, with a resolution of 202 kHz, during period [1]. During period [2] it was tuned to the H218O line at 547.676 GHz and connected to the AC2.

- The ``572B1'' receiver was tuned to the NH3 line at 572.498 GHz and connected to the AC1 during period [2].

Table 1: Log of H2O observations and production rates in comet C/2001 Q4 (NEAT) (average of AC1 and AC2+AOS data until 13 April).

2.1 Pointing accuracy

The precise knowledge of the pointing is always an issue for comet radio observations, because of the particular column density profile of the atmosphere. The Odin beam has an FWHM of 127

3 Conversion of line intensities into production rates

Line intensities are converted into production rates

(Table 1). A Haser model with symmetric outgassing

and constant radial expansion velocity is used to describe the density,

as in our previous studies (Biver et al. 1999). The relative population on

the rotational energy levels of water is computed throughout the coma

taking into account collisional excitation by neutrals at the

gas temperature (assumed constant throughout the coma), collisions with

electrons, radiative pumping by Solar infrared flux and self absorption

using the Sobolev approximation. The modelling and its accuracy are described

in detail in Zakharov et al. (2007). Then numerical integration of the

radiative transfer is done to convert production rates into line intensities.

As explained in Biver et al. (2007b), since we assume steady state outflow,

the retrieved production rates are referred to as ``apparent''

production rates (

![]() ).

For the modelling, we use the following parameters:

).

For the modelling, we use the following parameters:

- Expansion velocity:

![$v_{\rm exp} = 0.85\times(r_{\rm h}[{\rm AU}])^{-0.5}$](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/25/aa11790-09/img237.png) km s-1,

(

km s-1,

( ,

heliocentric distance), consistent with the shape

of H218O and H2O lines observed with Odin,

and other molecules observed with ground-based telescopes in early May

(Biver et al. 2009).

,

heliocentric distance), consistent with the shape

of H218O and H2O lines observed with Odin,

and other molecules observed with ground-based telescopes in early May

(Biver et al. 2009).

- Gas temperature:

![$T=70\times(r_{\rm h}[{\rm AU}])^{-1}$](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/25/aa11790-09/img239.png) K, i.e. 70 K around

perihelion, as measured from the relative intensity of methanol

lines observed at the Institut de radioastronomie millimétrique (IRAM)

30-m telescope between 7 and 11 May 2004 (Biver et al. 2009).

K, i.e. 70 K around

perihelion, as measured from the relative intensity of methanol

lines observed at the Institut de radioastronomie millimétrique (IRAM)

30-m telescope between 7 and 11 May 2004 (Biver et al. 2009).

- Collision rate with electrons: the scaling factor of the

electron density, as defined in Biver et al. (1999, 2007a),

was chosen to be

xne=0.2. It is actually constrained by the

radial evolution of the H2O line intensity observed in the map

obtained on 16 May (Biver et al. 2007a).

This value minimizes the difference between production rates based

on the various offset points.

4 Observed variations and simulations

Figure 1 shows the most representative sample of the

spectra obtained during nearly continuous monitoring of the comet.

Since these

spectra were taken in similar conditions (Table 1), the

variation in the line mostly reflects the variation in comet activity.

We can notice a regular increase followed by a decrease in the line intensity

from the long (20 h) series shown as the bottom of Fig. 1.

A regular increase in the line intensity is also seen 2 days

before (more precisely 39 h

![]() h, upper series)

suggesting some periodic variation in the activity

of the comet. For this reason we looked for characterising the variation

of the outgassing of the comet with time.

To characterise the variations in a more quantitative way,

we first converted line intensities into ``apparent'' production rates

as explained in Sect. 3, and then simulated those ``apparent'' production

rate with a periodic variation of the outgassing at the nucleus surface,

as done for comet 9P/Tempel 1 in Biver et al. (2007b).

For a sinusoidal variation, a phase difference (time delay)

is expected between the production rate Q(t) and the ``apparent'' production

rate evolution

h, upper series)

suggesting some periodic variation in the activity

of the comet. For this reason we looked for characterising the variation

of the outgassing of the comet with time.

To characterise the variations in a more quantitative way,

we first converted line intensities into ``apparent'' production rates

as explained in Sect. 3, and then simulated those ``apparent'' production

rate with a periodic variation of the outgassing at the nucleus surface,

as done for comet 9P/Tempel 1 in Biver et al. (2007b).

For a sinusoidal variation, a phase difference (time delay)

is expected between the production rate Q(t) and the ``apparent'' production

rate evolution

![]() .

This is due to the convolution of a

time-dependent density distribution with the beam shape of Odin.

The amplitude

.

This is due to the convolution of a

time-dependent density distribution with the beam shape of Odin.

The amplitude

![]() will be smaller than the variation

will be smaller than the variation

![]() of the sinusoid at the nucleus surface, due to beam averaging.

Pointing at offset

positions will further damp the variation and increase the delay

due to the travel time of the molecules. We made a simple simulation

with a production rate:

of the sinusoid at the nucleus surface, due to beam averaging.

Pointing at offset

positions will further damp the variation and increase the delay

due to the travel time of the molecules. We made a simple simulation

with a production rate:

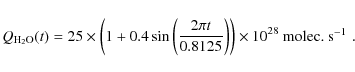

|

(1) |

At the nucleus surface,

Table 2: Parameters used for the computation of production rates.

In these simulations we did consider the time (and thus radial)

variation of the excitation of H2O due to the varying outgassing rate.

Other parameters like the

temperature may also vary radially. We tried different

![]() values

(up to 90%), but this does not change the relative

``damping'' factor much or the mean time delay - the apparent

production curve gets more asymmetric though.

values

(up to 90%), but this does not change the relative

``damping'' factor much or the mean time delay - the apparent

production curve gets more asymmetric though.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[height=18cm, angle=270]{1790fig1.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/25/aa11790-09/Timg262.png) |

Figure 1: Sample of AOS spectra obtained with Odin for comet C/2001 Q4 (NEAT) between 30.10 April and 2.51 May 2004. They are all plotted with the same intensity scale (in the main beam brightness temperature scale) and Doppler velocity scale relative to the nucleus. The upper and lower series are vertically aligned according to the rotation phase. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Table 3: Simulated signal for a periodic variation in the outgassing.

5 Long-term variation of the outgassing

Before looking for periodic variations, it

is wise to remove any long-term trend, due to the variation in solar heating

(

![]() )

and possible seasonal effects. The mean production rates

(daily averages with ranges) are plotted in Fig. 2:

the outgassing peaks well before perihelion, so that correcting

for a

)

and possible seasonal effects. The mean production rates

(daily averages with ranges) are plotted in Fig. 2:

the outgassing peaks well before perihelion, so that correcting

for a

![]() variation is not appropriate. We instead fit the

monthly evolution with a Gaussian.

In our least square fitting, we put greater weight on the 2 April

to 16 May data: for these dates we sampled the full amplitude

of the short time variation better and we also mapped the coma several times

and thus have a better estimate of the mean production rate.

The short March observations,

on the other hand, may not provide a good estimate of the mean value

around those times.

The time component of the fit is

variation is not appropriate. We instead fit the

monthly evolution with a Gaussian.

In our least square fitting, we put greater weight on the 2 April

to 16 May data: for these dates we sampled the full amplitude

of the short time variation better and we also mapped the coma several times

and thus have a better estimate of the mean production rate.

The short March observations,

on the other hand, may not provide a good estimate of the mean value

around those times.

The time component of the fit is

![]() ,

where t is the time measured in days relative to perihelion

and

,

where t is the time measured in days relative to perihelion

and

![]() days is a time shift that can be interpreted

as a seasonal effect.

It corresponds to an advance of the peak of outgassing with respect

to perihelion time.

The peak mean outgassing rate is

days is a time shift that can be interpreted

as a seasonal effect.

It corresponds to an advance of the peak of outgassing with respect

to perihelion time.

The peak mean outgassing rate is

![]() molec. s-1

molec. s-1 ![]() .

However, one should be cautious when using these values, since anisotropic

outgassing likely influences both the value and time of the peak.

It can result in a

10% underestimate of the outgassing rate as explained in Biver et al. (2007a).

A Gaussian fit, restricted to the 2 April to 16 May data

(Fig. 2), yields

.

However, one should be cautious when using these values, since anisotropic

outgassing likely influences both the value and time of the peak.

It can result in a

10% underestimate of the outgassing rate as explained in Biver et al. (2007a).

A Gaussian fit, restricted to the 2 April to 16 May data

(Fig. 2), yields

![\begin{displaymath}Q = 27.4\times10^{28}\exp\left(-\left(\frac{t[\rm days]+17.0}{45.7}\right)^2\right) ~\mbox{molec.~s$^{-1}$ ~}

\end{displaymath}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/25/aa11790-09/img270.png) |

(2) |

and is used to remove the long-term trend in the search for short-term variations.

![\begin{figure}

\par\resizebox{9cm}{!}{\includegraphics[angle=270]{1790fig2.ps}}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/25/aa11790-09/Timg272.png) |

Figure 2:

Long-term evolution of the water outgassing rate of comet

C/2001 Q4 (NEAT). The error-bars for the three first points are based

on statistical noise, while for the April-May points they represent the

dispersion of the values measured within a day. Two least square fits are

plotted: continuous line for

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

6 Short-term periodic variations

To search for short-term periodic variations,

we selected two subsets: the 26 April to 2

May observations (38 points), plotted in Fig. 3, and

the full subset of 57 observations between 2.5 April and 16.1 May

(Table 1).

We generally excluded data with a pointing offset greater than 70

![]() .

The first restricted dataset (a sample of spectra is shown in

Fig. 1) has the best consistency: all observations

were done in the same week and with the same set-up.

In addition, the offset positions were of 30

.

The first restricted dataset (a sample of spectra is shown in

Fig. 1) has the best consistency: all observations

were done in the same week and with the same set-up.

In addition, the offset positions were of 30

![]() to 55

to 55

![]() due

to ephemeris errors, but all in the same direction

of the sky (position angle

due

to ephemeris errors, but all in the same direction

of the sky (position angle ![]()

![]() ).

As a consequence, if the outgassing variations are connected to a rotating

jet, we do not expect a significant phase shift between observations.

In addition, the increase in ephemeris angular offset

(+70%) was partially compensated by the decrease in geocentric distance

(-23%), so we expect a very similar sensitivity to the periodic

variations for all observations. We do have the same ``damping'' factor

around 50% (Table 3).

The precision of the production rates, though, are

unlikely to be limited by the statistical noise (Table 1),

but rather by the pointing accuracy (Sect. 2.1).

A 3-4

).

As a consequence, if the outgassing variations are connected to a rotating

jet, we do not expect a significant phase shift between observations.

In addition, the increase in ephemeris angular offset

(+70%) was partially compensated by the decrease in geocentric distance

(-23%), so we expect a very similar sensitivity to the periodic

variations for all observations. We do have the same ``damping'' factor

around 50% (Table 3).

The precision of the production rates, though, are

unlikely to be limited by the statistical noise (Table 1),

but rather by the pointing accuracy (Sect. 2.1).

A 3-4

![]() pointing variation typically results

in a 5% uncertainty on the derived production rate for most measurements,

to be compared with a typical 1.3% uncertainty due to statistical noise

for 45 min integration. This 5% uncertainty has been added quadratically

to the rms in Table 1 for all data used in the

the

pointing variation typically results

in a 5% uncertainty on the derived production rate for most measurements,

to be compared with a typical 1.3% uncertainty due to statistical noise

for 45 min integration. This 5% uncertainty has been added quadratically

to the rms in Table 1 for all data used in the

the ![]() minimization (e.g., Fig. 3).

minimization (e.g., Fig. 3).

![\begin{figure}

\par\resizebox{9cm}{!}{\includegraphics[angle=270]{1790fig3.ps}}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/25/aa11790-09/Timg274.png) |

Figure 3: ``Apparent'' water production rates of comet C/2001 Q4 (NEAT) between 26 April and 4 May 2004 and best fit obtained with a sine + harmonic evolution (6 parameters, see text). The time has been corrected for the ``delay'' due to beam averaging and varying geometry. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

The other method we used to find a periodicity in the data is the phase dispersion minimization (PDM) method, introduced by Stellingwerf (1978). Particularly useful with a scarce and irregular sampling, it consists in folding the data around a test period Tp, binning the data, and computing the variance ratio between the binned data and the whole sample. This ratio should fluctuate around 1 in the absence of any periodic signal. Should Tp being a significant signal period, then the variance ratio would diminish toward zero, as the local variance would be significantly less than the global one.

The choice of the time origin should not influence the results, hence it is common practice to perform several calculations by time-shifting the folded data and to make an average. The main effect is to smooth the variance ratio curve, which is useful when a small amount of data is available. Considering this small number of data, we limited our number of bins to four, and we performed two time shifts. The result of the PDM method applied to the water production rates is given in Fig. 4. The deepest trough in the curve is at 0.82 day, and we can also see its second sub-harmonic around 1.6 days with a smaller depth, as expected.

We computed the significance level of the variance ratio, which rises when the trough is deeper, according to Stellingwerf (1978). The main parameters are the number of data points, the bin number, and how many time shifts were used. We obtain 98% and 75% for the restricted and the whole sample sets, respectively (see Table 4).

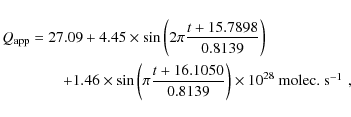

The other method consists in fitting a sine curve (four parameters:

average value, amplitude, period Tp, and reference time) or the composite

of a sine curve and its harmonic at Tp/2 (6 parameters). The

parameters are optimized via ![]() minimization.

For the best fits, we should get a reduced

minimization.

For the best fits, we should get a reduced

![]() close to unity.

The

close to unity.

The ![]() uncertainty on the fitted period parameter Tp, taken alone,

is computed from the extrema of the

uncertainty on the fitted period parameter Tp, taken alone,

is computed from the extrema of the

![]() envelope.

envelope.

![\begin{figure}

\par\resizebox{9cm}{!}{\includegraphics[angle=270]{1790fig4.ps}}\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/25/aa11790-09/Timg278.png) |

Figure 4: Periodogram analysis of the restricted data set (26 April to 3 May 2004) of comet water production rates. The deepest peak with a variance ratio of 0.5 corresponds to a 0.82 day period. This is the main period found in this analysis: other peaks are mainly coming from harmonics (at 1.6 and 2.4 day) and aliasing. Indeed simulating a pure sine variation of period 0.82 day with the same sampling reproduces all the peaks with variance ratio <0.9. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\resizebox{9cm}{!}{\includegraphics[angle=270]{1790fig5.ps}}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/25/aa11790-09/Timg279.png) |

Figure 5: Same data as in Fig. 3, folded over one period of 19.53 h, after long-term amplitude correction and ``delay'' correction as in Fig. 3. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

6.1 Analysis of the restricted subset

The result of the search of periodicity with the PDM method is shown

in Fig. 4 and yields a significant minimum peak at 0.815 day.

We then tried to fit a sine (4 parameters) and sine with one

harmonic (6 parameters) function to the data. Figures 3 and

5 show the data and results of the ![]() minimization.

The reduced

minimization.

The reduced ![]() is smaller (

is smaller (

![]() versus

versus

![]() )

when adding an harmonic and the solution found is

)

when adding an harmonic and the solution found is

where t is the time in days relative to perihelion, corrected for the delay due to beam dilution. The

6.2 Analysis of the larger subset of 57 points

We also analysed the larger subset with both methods

(PDM and sine fitting). The first one gives a peak around Tp=0.817 day

(with a nearby less significant peak at 0.852 day) with a 75% confidence

level while a sine fit yields Tp=0.8195 day (

![]() ).

The 6-parameter sinusoidal fit yields

Tp=0.8188 day (

).

The 6-parameter sinusoidal fit yields

Tp=0.8188 day (

![]() ,

95.4% confidence level:

Tp=0.8177-0.8198 day).

,

95.4% confidence level:

Tp=0.8177-0.8198 day).

The fit is clearly not as good as for the one week dataset, most likely

because the changing geometry (seasonal effect) of the nucleus added

some other variation not represented here. Indeed, between 2 April and 16 May

the comet moved by 69![]() around the Sun, and the illumination of the active

regions on the nucleus must have changed. The observed seasonal effect

(

around the Sun, and the illumination of the active

regions on the nucleus must have changed. The observed seasonal effect

(![]() 18-day shift between perihelion and the peak of activity, Sect. 5)

means that the obliquity of the nucleus rotation axis is strong,

as suggested by Vasundhara et al. (2007), and that the illumination on

active regions changed a lot around perihelion.

In particular, the amplitude of rotational variation observed in early April

is more than expected.

We would have expected a relative amplitude

18-day shift between perihelion and the peak of activity, Sect. 5)

means that the obliquity of the nucleus rotation axis is strong,

as suggested by Vasundhara et al. (2007), and that the illumination on

active regions changed a lot around perihelion.

In particular, the amplitude of rotational variation observed in early April

is more than expected.

We would have expected a relative amplitude

![]() twice smaller

(Table 3), while instead it is slightly larger.

The 1.5-month span is yielding a slightly better precision in estimating

the period, although with a lower confidence (Table 4).

It is compatible with the period found from the one week dataset.

twice smaller

(Table 3), while instead it is slightly larger.

The 1.5-month span is yielding a slightly better precision in estimating

the period, although with a lower confidence (Table 4).

It is compatible with the period found from the one week dataset.

In summary, we find a clear periodicity in the water outgassing rate,

with a best-fit period

![]() day (19h

day (19h![]() min).

The observed amplitude of the periodic variation is

min).

The observed amplitude of the periodic variation is ![]()

![]() molec. s-1 for a mean value of

molec. s-1 for a mean value of

![]() molec. s-1

molec. s-1 ![]() ,

i.e. 19%. Given the simulations

(Table 3), this implies a real variation in

the production rate of

,

i.e. 19%. Given the simulations

(Table 3), this implies a real variation in

the production rate of ![]()

![]() %; e.g. the outgassing rate of the

comet at the end of

April was varying by a factor greater than 2 in 19.6 h. This must be taken

into account when determining mixing ratios from non simultaneous measurements.

On the other hand, the analysis of the Doppler shift of the lines does not

reveal very significant variations (Table 1):

on the restricted subset a sine fit yields a period of

%; e.g. the outgassing rate of the

comet at the end of

April was varying by a factor greater than 2 in 19.6 h. This must be taken

into account when determining mixing ratios from non simultaneous measurements.

On the other hand, the analysis of the Doppler shift of the lines does not

reveal very significant variations (Table 1):

on the restricted subset a sine fit yields a period of

![]() day with a reduced

day with a reduced

![]() .

But this

fit may not be considered as a very good fit since it is barely better

than if we fit a straight line (

.

But this

fit may not be considered as a very good fit since it is barely better

than if we fit a straight line (

![]() ).

).

Table 4: Time periods found to fit the data.

7 Comparison with other observations

The outgassing of C/2001 Q4 (NEAT) and its variations were the topic of many studies.

On 24-29 April, HST observations of the Lyman-![]() line gave a mean

line gave a mean

![]() of

of

![]() (Weaver et al. 2008), somewhat below the Odin

measurements. The OH observations with the Nançay radio telescope began on

2 May, when the comet's declination became higher than -40

(Weaver et al. 2008), somewhat below the Odin

measurements. The OH observations with the Nançay radio telescope began on

2 May, when the comet's declination became higher than -40![]() (Colom et al. 2004; Crovisier et al. 2009). Production rates

(Colom et al. 2004; Crovisier et al. 2009). Production rates

![]() molec. s-1

(corresponding to

molec. s-1

(corresponding to

![]()

![]() molec. s-1 were

observed at the beginning of May, somewhat below the values observed

by Odin at the same time (Fig. 2).

These observations, which consisted

of 1-h integrations performed every

molec. s-1 were

observed at the beginning of May, somewhat below the values observed

by Odin at the same time (Fig. 2).

These observations, which consisted

of 1-h integrations performed every ![]() 24 h, are not suitable for

investigating a

24 h, are not suitable for

investigating a ![]() 20 h periodicity.

20 h periodicity.

Other observers have noticed periodic variation in the activity of this

comet. Feldman et al. (2004) find a 17.0 h sine variation with a factor 1.6

from minimum to maximum in the intensity of the CO C-X(0-0) band

observed with FUSE on 24 April. Vasundhara et al. (2007), from images

obtained between 16 April and 3 June at various places, report a periodic

variation of the morphology of the dust coma, but they did not attempt to

derive a period. In images obtained at Pic-du-Midi Observatory from 14 to

19 May, Lecacheux & Frappa (2004) find features repeating periodically in

the coma of the comet with a

![]() h period, close to the

determination by Odin.

h period, close to the

determination by Odin.

8 Conclusion

The H2O outgassing of comet C/2001 Q4 (NEAT) was monitored by the Odin satellite between 6 March and 16 May 2004. The intensity of the 557 GHz H2O line shows strong variations tracing the non-constant activity of the comet. The following results were obtained:

- 1.

- The outgassing peaked

18 days before perihelion,

tracing a seasonal effect, with a mean peak of

18 days before perihelion,

tracing a seasonal effect, with a mean peak of

molec. s-1

molec. s-1  .

.

- 2.

- The comet exhibited strong periodic

variations in its outgassing with a period of

days, implying a

days, implying a

40% variation around the mean value.

40% variation around the mean value.

Acknowledgements

Generous financial support from the research councils and space agencies in Canada, Finland, France, and Sweden is gratefully acknowledged. The authors thanks the whole Odin team, including the engineers who have been very supportive of these difficult comet observations. Their help was essential in solving problems in near real time for such time critical observations.

References

- Biver, N., Bockelée-Morvan, D., Crovisier, J., et al. 1999, AJ, 118, 1850 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Biver, N., Bockelée-Morvan, D., Crovisier, J., et al. 2007a, Planet. Space Sci., 55, 1058 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Biver, N., Bockelée-Morvan, D., Boissier, J., et al. 2007b, Icarus, 191, 494 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Biver, N., Bockelée-Morvan, D., Crovisier, J., et al. 2009, in preparation (In the text)

- Bockelée-Morvan, D., Henry, F., Biver, N., et al. 2009, A&A, submitted (In the text)

- Colom, P., Biver, N., Crovisier, J., Lecacheux, A., & Bockelée-Morvan, D. 2004, in SF2A Scientific Highlights 2004, ed. F. Combes, et al. (EDP Sciences), 69 (In the text)

- Crovisier, J., Colom, P., Biver, N., & Bockelée-Morvan, D., 2009 in preparation (In the text)

- Feldman, P. D., Weaver, H. A., Christian, D., et al. 2004, BAAS, 36, 1121 [NASA ADS] (In the text)

- Festou, M. C., Keller, H. U., & Weaver, H. A. 2004, in Comets II, ed. M. C. Festou, H. U. Keller, & H. A. Weaver (Univ. of Arizona Press), 3 (In the text)

- Frisk, U., Hagström, M., Ala-Laurinaho, J., et al. 2003, A&A, 402, L27 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] (In the text)

- Jehin, E., Manfroid, J., Hutsemékers, D., et al. 2006, ApJ, 641, L145 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Jorda, L., Rembor, K., Lecacheux, J., et al. 1997, Earth, Moon, and Planets, 77, 167 (In the text)

- Lamy, P. L., Toth, I., Fernandez, Y. R., & Weaver, H. A. 2004, in Comets II, ed. M. C. Festou, H. U. Keller, & H. A. Weaver (Univ. of Arizona Press), 223 (In the text)

- Lecacheux, J., & Frappa, E. 2004, IAU Circ., 8349 (In the text)

- Lecacheux, A., Biver, N., Crovisier, J., et al. 2003, A&A, 402, L55 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] (In the text)

- Lecacheux, J., & Frappa, E. 2004, IAU Circ., 8349 (In the text)

- Lederer, S. M., Campins, H., & Osip, D. J. 2009, Icarus, 199, 484 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Neufeld, D. A., Stauffer, J. R., Bergin, E. A., et al. 2000, ApJ, 539, L151 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Nordh, H. L., von Schéele, F., Frisk, U., et al. 2003, A&A, 402, L21 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] (In the text)

- Samarasinha, N. H., Mueller, B. E. A., Belton, M. J. S., & Jorda, L. 2004, in Comets II, ed. M. C. Festou, H. U. Keller, & H. A. Weaver (Univ. of Arizona Press), 281 (In the text)

- Stellingwerf, R. F. 1978, ApJ, 224, 953 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Vasundhara, R., Chakraborty, P., Muneer, S., Masi, G., & Rondi, S. 2007, AJ, 133, 612 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Weaver, H. A., A'Hearn, M. F., Arpigny, C., et al. 2008, Asteroids, Comets, Meteors 2008, LPI Contribution, 1405, 8216 (In the text)

- Zakharov, V., Bockelée-Morvan, D., Biver, N., Crovisier, J., & Lecacheux, A. 2007, A&A, 473, 303 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] (In the text)

Footnotes

- ... satellite

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- Odin is a Swedish-led satellite project funded jointly by the Swedish National Space Board (SNSB), the Canadian Space Agency (CSA), the National Technology Agency of Finland (Tekes) and the Centre National d'Études Spatiales (CNES, France). The Swedish Space Corporation is the prime contractor, also responsible for Odin operations.

- ... Quarterly

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- http://www.cfa.harvard.edu/icq/icq.html

All Tables

Table 1: Log of H2O observations and production rates in comet C/2001 Q4 (NEAT) (average of AC1 and AC2+AOS data until 13 April).

Table 2: Parameters used for the computation of production rates.

Table 3: Simulated signal for a periodic variation in the outgassing.

Table 4: Time periods found to fit the data.

All Figures

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[height=18cm, angle=270]{1790fig1.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/25/aa11790-09/Timg262.png) |

Figure 1: Sample of AOS spectra obtained with Odin for comet C/2001 Q4 (NEAT) between 30.10 April and 2.51 May 2004. They are all plotted with the same intensity scale (in the main beam brightness temperature scale) and Doppler velocity scale relative to the nucleus. The upper and lower series are vertically aligned according to the rotation phase. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\resizebox{9cm}{!}{\includegraphics[angle=270]{1790fig2.ps}}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/25/aa11790-09/Timg272.png) |

Figure 2:

Long-term evolution of the water outgassing rate of comet

C/2001 Q4 (NEAT). The error-bars for the three first points are based

on statistical noise, while for the April-May points they represent the

dispersion of the values measured within a day. Two least square fits are

plotted: continuous line for

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\resizebox{9cm}{!}{\includegraphics[angle=270]{1790fig3.ps}}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/25/aa11790-09/Timg274.png) |

Figure 3: ``Apparent'' water production rates of comet C/2001 Q4 (NEAT) between 26 April and 4 May 2004 and best fit obtained with a sine + harmonic evolution (6 parameters, see text). The time has been corrected for the ``delay'' due to beam averaging and varying geometry. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\resizebox{9cm}{!}{\includegraphics[angle=270]{1790fig4.ps}}\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/25/aa11790-09/Timg278.png) |

Figure 4: Periodogram analysis of the restricted data set (26 April to 3 May 2004) of comet water production rates. The deepest peak with a variance ratio of 0.5 corresponds to a 0.82 day period. This is the main period found in this analysis: other peaks are mainly coming from harmonics (at 1.6 and 2.4 day) and aliasing. Indeed simulating a pure sine variation of period 0.82 day with the same sampling reproduces all the peaks with variance ratio <0.9. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\resizebox{9cm}{!}{\includegraphics[angle=270]{1790fig5.ps}}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/25/aa11790-09/Timg279.png) |

Figure 5: Same data as in Fig. 3, folded over one period of 19.53 h, after long-term amplitude correction and ``delay'' correction as in Fig. 3. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

Copyright ESO 2009

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.