| Issue |

A&A

Volume 500, Number 3, June IV 2009

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Page(s) | 1045 - 1063 | |

| Section | Galactic structure, stellar clusters, and populations | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/200911771 | |

| Published online | 16 April 2009 | |

A new population of cool stars and brown dwarfs

in the Lupus clouds![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png) ,

,![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

F. Comerón1,![]() - L. Spezzi2,3 - B. López Martí4

- L. Spezzi2,3 - B. López Martí4

1 - ESO, Karl-Schwarzschild-Strasse 2, 85748 Garching, Germany

2 - INAF - Osservatorio Astrofisico di Catania, via S. Sofia, 78, 95123 Catania, Italy

3 - Research and Scientific Support Department, European Space Agency (ESTEC), PO Box 299, 2200 AG Noordwijk, The Netherlands

4 - Laboratorio de Astrofísica Estelar y Exoplanetas - Centro de Astrobiología (LAEX-CAB/INTA-CSIC, LAEFF-Apdo. 78, 28691 Villanueva de la Cañada, Spain

Received 2 February 2009 / Accepted 6 April 2009

Abstract

Context. Most studies of the stellar and substellar populations of star-forming regions rely on using the signatures of accretion, outflows, disks, or activity characterizing the early stages of stellar evolution. However, these signatures rapidly decay with time.

Aims. We present the results of a wide-area study of the stellar population of clouds in the Lupus star-forming region. When combined with 2MASS photometry, our data allow us to fit the spectral energy distributions of over 150 000 sources and identify possible new members based on their photospheric fluxes, independent of any display of the signposts of youth.

Methods. We used the Wide Field Imager (WFI) at the La Silla 2.2 m telescope to image an area of more than 6 square degrees in the Lupus 1, 3 and 4 clouds in the ![]() ,

,

![]() ,

and

,

and

![]() bands, selected so as to overlap with the areas observed in the Spitzer Legacy Program ``From molecular cores to planet-forming disks''. We complement our data with 2MASS photometry to sample the spectral energy distribution from 0.6

bands, selected so as to overlap with the areas observed in the Spitzer Legacy Program ``From molecular cores to planet-forming disks''. We complement our data with 2MASS photometry to sample the spectral energy distribution from 0.6 ![]() m to 2.2

m to 2.2 ![]() m. We validate our method on the census of known members of the Lupus clouds, for which spectroscopic classification is available. The temperatures derived for cool objects are generally accurate, with most of the exceptions attributed to veiling, strong emission lines at short wavelengths, near-infrared excess, variability, or the presence of close companions.

m. We validate our method on the census of known members of the Lupus clouds, for which spectroscopic classification is available. The temperatures derived for cool objects are generally accurate, with most of the exceptions attributed to veiling, strong emission lines at short wavelengths, near-infrared excess, variability, or the presence of close companions.

Results. Considering that the dereddened fluxes of most cool (

![]() K) young stellar objects at the distance of Lupus occupy a gap between those typical both of field cool dwarfs and of background giants, we identify a new population of cool members of Lupus 1 and 3. The approximately 130 new members are only moderately concentrated toward the densest clouds, they appear to have ages in the same range as the known members, and very few show the infrared excess caused by warm disks. This population is absent in Lupus 4.

K) young stellar objects at the distance of Lupus occupy a gap between those typical both of field cool dwarfs and of background giants, we identify a new population of cool members of Lupus 1 and 3. The approximately 130 new members are only moderately concentrated toward the densest clouds, they appear to have ages in the same range as the known members, and very few show the infrared excess caused by warm disks. This population is absent in Lupus 4.

Conclusions. This new population of Lupus members seems to be composed of stars and brown dwarfs that have lost their inner disks on a timescale of a few Myr or less. Almost all these objects are in low extinction regions. We speculate that dissipation of unshielded disks caused by nearby O stars or fast collapse of the pre-(sub)stellar cores triggered by the passage of old supernova shocks may have led to disk properties and evolutionary paths very different from those resulting from the more quiescent environment provided by dense molecular clouds.

Key words: stars: low-mass, brown dwarfs - stars: formation - stars: pre-main sequence - ISM: individual objects: Lupus - ISM: clouds

1 Introduction

Much of our current knowledge of the earliest stages of the evolution of very low mass stars and brown dwarfs, the signatures of stellar and substellar youth, and the build-up and shape of the initial mass function comes from the observation of a number of star-forming regions within 150-200 pc from the Sun (see Reipurth 2008 for an extensive collection of reviews). The availability of instruments with large format, sensitive detectors operating at different wavelengths both on the ground and in space has made it possible to obtain an increasingly complete census of the young populations in all these regions down to masses well below the substellar limit. The approach normally adopted consists of using different telltale features displayed by young stellar objects as a way to identify members, and derive their intrinsic properties by means of detailed follow-up observations or with the help of photometric information.

The Lupus clouds, a complex of low-mass star-forming regions in

the Scorpius-Centaurus OB association, has been the target of a

number of such investigations (see Comerón 2008 for a historical

review and a summary of existing results). Those clouds are spread

over a large area of the sky, nearly ![]() across, with

galactic longitudes in the range

across, with

galactic longitudes in the range

![]() and

latitudes

and

latitudes

![]() .

Following early slitless

spectroscopy surveys by Thé (1962) and Schwartz (1977) which

revealed for the first time the rich T Tauri content of the Lupus

clouds, their lowest mass component has been probed by more recent

studies at different wavelengths. Hughes et al. (1994) obtained

spectroscopy and infrared photometry for the members listed by

Schwartz (1977). The Lupus 3 cloud, which contains the largest number

and density of members, has been the target of several surveys:

Nakajima et al. (2000) identified some possible very low luminosity members

by means of near-infrared excesses. Comerón et al. (2003) added four new

members identified through their H

.

Following early slitless

spectroscopy surveys by Thé (1962) and Schwartz (1977) which

revealed for the first time the rich T Tauri content of the Lupus

clouds, their lowest mass component has been probed by more recent

studies at different wavelengths. Hughes et al. (1994) obtained

spectroscopy and infrared photometry for the members listed by

Schwartz (1977). The Lupus 3 cloud, which contains the largest number

and density of members, has been the target of several surveys:

Nakajima et al. (2000) identified some possible very low luminosity members

by means of near-infrared excesses. Comerón et al. (2003) added four new

members identified through their H![]() emission, including a M 8

brown dwarf. López Martí et al. (2005) have proposed 22 additional candidate

members of Lupus 3 based on a wide-area survey using a combination

of filters that allowed them to identify possible H

emission, including a M 8

brown dwarf. López Martí et al. (2005) have proposed 22 additional candidate

members of Lupus 3 based on a wide-area survey using a combination

of filters that allowed them to identify possible H![]() -emitting

members and to estimate their temperatures from intermediate-band

differential photometry near selected spectral features. Deep X-ray

observations of Lupus 3, sensitive to the emission from brown

dwarfs, have been presented by Gondoin (2006).

-emitting

members and to estimate their temperatures from intermediate-band

differential photometry near selected spectral features. Deep X-ray

observations of Lupus 3, sensitive to the emission from brown

dwarfs, have been presented by Gondoin (2006).

The most comprehensive recent searches for members of the Lupus clouds have been based on the results obtained by the Spitzer Space Observatory. As a result of the Spitzer Legacy program From molecular cores to planet-forming disks (Evans et al. 2008,2003), a number of papers (Merín et al. 2008; Allers et al. 2006; Chapman et al. 2007) have reported on the discovery of new low-mass members and the confirmation of previously suspected ones. Further Spitzer observations of the region have been presented by Allen et al. (2007). These identifications are based on the determination of spectral energy distributions at infrared wavelengths, where warm dust dominates the emission. Merín et al. (2008) have synthesized the Spitzer findings on the Lupus 1, 3, and 4 clouds, and have discussed the properties of both the central objects and their circumstellar material. Together with the results of previous surveys, the member lists presented by Merín et al. (2008) represent the most complete census to date of stars and brown dwarfs in Lupus 1, 3, and 4.

Despite their wide coverage and the ability to reveal very

low mass members, surveys based on the detection of H![]() emission or infrared excesses caused by warm dust leave the question

open about the fraction of members of a star-forming region that

may not be accreting or surrounded by a sufficient amount of dust.

Observational evidence points toward disk lifetimes of only a few Myr, with a significant fraction of stars losing their disks over a

timescale that is comparable to the duration of the embedded phase (e.g.

Haisch et al. 2001). In fact, as pointed out by Merín et al. (2008), some confirmed

members of the star-forming region observed by Spitzer do not meet the

infrared excess-based color criteria for their selection of

candidates. Unbiased surveys where the identification of

members is based solely on the photospheric properties (e.g.

Luhman 2007) appear thus as a necessary complement of those based

on the identification of signatures of accretion, dust, or the

strong chromospheric activity characteristic of young stellar objects.

emission or infrared excesses caused by warm dust leave the question

open about the fraction of members of a star-forming region that

may not be accreting or surrounded by a sufficient amount of dust.

Observational evidence points toward disk lifetimes of only a few Myr, with a significant fraction of stars losing their disks over a

timescale that is comparable to the duration of the embedded phase (e.g.

Haisch et al. 2001). In fact, as pointed out by Merín et al. (2008), some confirmed

members of the star-forming region observed by Spitzer do not meet the

infrared excess-based color criteria for their selection of

candidates. Unbiased surveys where the identification of

members is based solely on the photospheric properties (e.g.

Luhman 2007) appear thus as a necessary complement of those based

on the identification of signatures of accretion, dust, or the

strong chromospheric activity characteristic of young stellar objects.

In this paper we present the results of a broad-band, wide-area

visible imaging survey of the Lupus 1, 3, and 4 clouds complemented

with near-infrared photometry from the 2MASS point source catalog.

Our new observations, presented in Sect. 2, cover the

interval between 0.6 and 0.96 ![]() m and, when combined with JHKSphotometry from 2MASS, provide a good sampling of the spectral

energy distribution in the region around its peak for young low mass

stars and brown dwarfs. The wide wavelength baseline allows us to

perform a robust fit to the intrinsic spectral energy distribution

predicted by model atmospheres and pre-main sequence evolutionary

tracks, which we describe in Sect. 3. In this way we

produce lists of candidate members of the star-forming region, which

can be compared to the census of members obtained by previous works

like those outlined above using different approaches.

m and, when combined with JHKSphotometry from 2MASS, provide a good sampling of the spectral

energy distribution in the region around its peak for young low mass

stars and brown dwarfs. The wide wavelength baseline allows us to

perform a robust fit to the intrinsic spectral energy distribution

predicted by model atmospheres and pre-main sequence evolutionary

tracks, which we describe in Sect. 3. In this way we

produce lists of candidate members of the star-forming region, which

can be compared to the census of members obtained by previous works

like those outlined above using different approaches.

A major uncertainty factor in deriving intrinsic properties of young stellar objects is the rather poor accuracy with which the distances to their host star-forming regions are generally known. In the case of Lupus, the existent distance determinations have been reviewed by Comerón (2008). Following the discussion in that work we will adopt 150 pc for Lupus 1 and 4, and 200 pc for Lupus 3.

The areas covered by the survey presented here were chosen so as to have a large overlap with the regions observed by the Spitzer legacy program From molecular cores to planet-forming disks, and data presented here have already been used in the analyses of Merín et al. (2007) and Merín et al. (2008). Therefore, this paper provides the detailed description of the visible observations used in those works.

2 Observations and data reduction

The material presented in this paper is based on imaging of the

Lupus 1, 3, and 4 clouds obtained with the Wide Field Imager (WFI)

at the MPI-ESO 2.2m telescope on La Silla, Chile (Baade et al. 1999).

Images were obtained through filters approximately covering the

Cousins ![]() and

and ![]() bands, as well as through an intermediate-width band near 0.96

bands, as well as through an intermediate-width band near 0.96 ![]() m to which we will refer as

m to which we will refer as

![]() .

The detector plane of WFI is covered by an array of

.

The detector plane of WFI is covered by an array of

![]() individual CCD chips, each with

individual CCD chips, each with

![]() pixel2, covering a field of view of

pixel2, covering a field of view of

![]() with small gaps of 14'' and 23'' between adjacent chips. The pixel scale is 0''238 pixel-1.

with small gaps of 14'' and 23'' between adjacent chips. The pixel scale is 0''238 pixel-1.

A total of 24 fields were observed covering the areas of highest dust column density in each of the clouds according to IRAS 100 ![]() m emission maps, selected to include most of the areas

surveyed in the Spitzer Legacy program From molecular cores to planet-forming disks. The area of the sky covered in each cloud is 2.84 square degrees in Lupus 1, 2.78 in Lupus 3, and 1.11

in Lupus 4. The observations were carried out in Service Mode

during ESO periods 69 (April-October 2002) and 71 (April-October 2003). Since the

execution in Service Mode implies that the observations are carried

out when the external conditions are within a pre-specified range,

rather than on fixed dates (Comerón 2004), individual observations

were spread over many observing nights, spanning a few months every

period. The observations scheduled in 2003 included fields that

could not be observed at all in the previous year, as well as the

completion of the observations of fields that could be imaged only

in some of the filters in 2002.

m emission maps, selected to include most of the areas

surveyed in the Spitzer Legacy program From molecular cores to planet-forming disks. The area of the sky covered in each cloud is 2.84 square degrees in Lupus 1, 2.78 in Lupus 3, and 1.11

in Lupus 4. The observations were carried out in Service Mode

during ESO periods 69 (April-October 2002) and 71 (April-October 2003). Since the

execution in Service Mode implies that the observations are carried

out when the external conditions are within a pre-specified range,

rather than on fixed dates (Comerón 2004), individual observations

were spread over many observing nights, spanning a few months every

period. The observations scheduled in 2003 included fields that

could not be observed at all in the previous year, as well as the

completion of the observations of fields that could be imaged only

in some of the filters in 2002.

The observations of each individual field were distributed in two

Observation Blocks (OBs). The first OB described the instrument

setup and exposure parameters in the R and I filters, while the

second one described the observation in the

![]() filter.

Such split was needed due to the long exposure time per field when

adding the integrations in all the filters, and facilitated the

scheduling of the observations. The disadvantage is that

observations in R and I on one side, and

filter.

Such split was needed due to the long exposure time per field when

adding the integrations in all the filters, and facilitated the

scheduling of the observations. The disadvantage is that

observations in R and I on one side, and

![]() on the

other, were in general not simultaneous. Furthermore, most of the

on the

other, were in general not simultaneous. Furthermore, most of the

![]() observations were carried out on the second year,

whereas the R and I observations were roughly evenly distributed

between both periods. As a result, for many fields the lag between

the RI and the

observations were carried out on the second year,

whereas the R and I observations were roughly evenly distributed

between both periods. As a result, for many fields the lag between

the RI and the

![]() observations can approach or slightly

exceed one year. The total exposure times per field and filter were

1600s in R, 240s in I, and 1320s in

observations can approach or slightly

exceed one year. The total exposure times per field and filter were

1600s in R, 240s in I, and 1320s in

![]() .

The observations in

each filter were split into four individual exposures, shifting the

telescope pointing by small amounts (between 1' and 2') between

consecutive pointings so as to cover the gaps between the individual

chips forming the WFI detector. The total coverage of each field led

to an overlap band 5' wide between adjacent fields.

.

The observations in

each filter were split into four individual exposures, shifting the

telescope pointing by small amounts (between 1' and 2') between

consecutive pointings so as to cover the gaps between the individual

chips forming the WFI detector. The total coverage of each field led

to an overlap band 5' wide between adjacent fields.

The observations were processed by using a number of dedicated

IRAF![]() scripts in charge of

the different steps of the data reduction. Master bias frames were

constructed, for each night in which observations for our program

were obtained, from the standard calibration data products supplied

with the Service Mode data package. Regarding flat fields, the best

results were obtained with twilight sky flat field frames rather

than with dome flat field frames. The stability of the sky flat

field frames was found to be sufficiently good for the use of a

single master sky flat field frame in each filter for each of the

observing seasons, which was obtained by combining all the sky flat

field frames included in our data packages.

scripts in charge of

the different steps of the data reduction. Master bias frames were

constructed, for each night in which observations for our program

were obtained, from the standard calibration data products supplied

with the Service Mode data package. Regarding flat fields, the best

results were obtained with twilight sky flat field frames rather

than with dome flat field frames. The stability of the sky flat

field frames was found to be sufficiently good for the use of a

single master sky flat field frame in each filter for each of the

observing seasons, which was obtained by combining all the sky flat

field frames included in our data packages.

Fringing strongly affects the WFI observations taken in the Iand

![]() filters. To remove the fringing pattern, we first

identified the science frames in those filters in our data sets that

were virtually free from nebulosity. After inspection of the

fringing pattern we grouped those sharing the same pattern, since

2-3 pattern changes typically took place during the period spanned

by our observations in each of the two seasons. Then, a master

fringing frame in each of the two affected filters was constructed

by subtracting from each frame its average sky level, and median

filtering all the frames of each group together. The suitable master

fringing frame was then scaled by a factor of order unity to account

for the amplitude of the fringes in the individual science frames.

The precise value of the scaling factor was determined by

iteratively subtracting from each science frame the master fringing

pattern with different values of this factor, until finding one that

left no visible residual fringing. We found that visual inspection

provided the best criterion to determine the fringing scaling

factor. In all cases a good solution could be found that effectively

removed the fringing pattern of the science frames after proper

scaling.

filters. To remove the fringing pattern, we first

identified the science frames in those filters in our data sets that

were virtually free from nebulosity. After inspection of the

fringing pattern we grouped those sharing the same pattern, since

2-3 pattern changes typically took place during the period spanned

by our observations in each of the two seasons. Then, a master

fringing frame in each of the two affected filters was constructed

by subtracting from each frame its average sky level, and median

filtering all the frames of each group together. The suitable master

fringing frame was then scaled by a factor of order unity to account

for the amplitude of the fringes in the individual science frames.

The precise value of the scaling factor was determined by

iteratively subtracting from each science frame the master fringing

pattern with different values of this factor, until finding one that

left no visible residual fringing. We found that visual inspection

provided the best criterion to determine the fringing scaling

factor. In all cases a good solution could be found that effectively

removed the fringing pattern of the science frames after proper

scaling.

Another factor affecting WFI frames, common to focal reducers, is

the existence of sky concentration, which requires the determination

of an illumination correction map. This effect is well known to

exist at the WFI to the level of a few hundredths of a magnitude

throughout most of the field, reaching slightly above 0.1 mag near

the edges of the field. Since no calibrations suitable for a quantification of this effect in our images were obtained, we applied instead the WFI illumination correction map in the R band derived by Koch et al. (2003) and assumed it to be approximately applicable to the I and

![]() filters as well. Judging from the residual differences between the illumination correction

maps computed by Koch et al. in different filters, we expect the

systematic error introduced in this way not to exceed 0.03 mag

anywhere in the field. On the other hand, we examined the residuals

of the fits of photometric solutions derived from observations of

Landolt (1992) standard star fields (Sect. 2.1) obtained

as a part of the WFI calibration plan during the nights in which our

observations were carried out. Although the crowding of these fields

with standard stars is far too sparse to independently derive

illumination correction maps, the absence of systematic positional

trends in the residuals gives us confidence that the applied

procedure is indeed sufficiently accurate down a few hundredths of a

magnitude.

filters as well. Judging from the residual differences between the illumination correction

maps computed by Koch et al. in different filters, we expect the

systematic error introduced in this way not to exceed 0.03 mag

anywhere in the field. On the other hand, we examined the residuals

of the fits of photometric solutions derived from observations of

Landolt (1992) standard star fields (Sect. 2.1) obtained

as a part of the WFI calibration plan during the nights in which our

observations were carried out. Although the crowding of these fields

with standard stars is far too sparse to independently derive

illumination correction maps, the absence of systematic positional

trends in the residuals gives us confidence that the applied

procedure is indeed sufficiently accurate down a few hundredths of a

magnitude.

Once corrected for bias, flat field, fringing and illumination, individual images in each filter were combined into a single mosaic per field. This was done by determining the offsets among the four exposures of each field for each individual detector chip using the stellar images as references, and then combining the images in each chip correcting for the offsets. Because the amplitude of the offsets was larger than the size of the interchip gaps, the combined, offset-corrected images of each chip overlapped, thus making it possible to precisely determine the offsets between adjacent chips using the stars in the overlap regions as reference. In this way a single full field image was produced for each filter by stacking together the four individual exposures.

Astrometric calibration of each field was carried out by using stellar positions in the USNO-A2.0 catalog, which provides several thousand stars per field. A distortion correction was then applied to the images through scripts making use of the IRAF GEOMAP and GEOTRANS tasks. The rms error in stellar coordinates is found to be better than 0''3 by comparison to the USNO-A2.0 astrometry, and confirmed by cross-matching with the 2MASS point source catalog (see Sect. 2.1.3).

The distortion-corrected images of each field in the three observed filters were stacked together into a single combined image where source detection was carried out using DAOFIND. Aperture photometry, using IRAF scripts based on DAOPHOT (Stetson 1987) on each position where a source was detected, was then carried out on the original combined image in each filter, thus producing a catalog with the coordinates and instrumental magnitude of each object in each of the three filters. The aperture radius was individually set for each image taking as a reference the full-width at half-maximum (FWHM) of bright unsaturated stars, in order to account for the varying image quality among the different fields. An aperture radius of five times the FWHM (i.e. typically about 6'') was used.

2.1 Photometric calibration

2.2.1

and

and

filters

filters

At least one, and frequently more, observations of Landolt standard star fields (Landolt 1992) were carried out every night that R and I observations were obtained for our program. This allowed us to determine both photometric zeropoints and color terms for each of those two filters in order to convert instrumentally determined magnitudes to the Cousins system. No attempt was made to determine in addition extinction terms, since the small number of standard star fields observed per night prevented their determination on a nightly basis. Instead, average extinction coefficients for La Silla in those filters were used.

Whereas the R and the

![]() filters used were the same

in the 2002 and 2003 periods, the standard I filter used at WFI,

denominated Ic in 2002, was replaced shortly after the beginning

of the 2003 period by the so-called I/203 filter. As a result,

part of our observations carried out in 2003 were obtained with a

I filter different from that used for the rest of the

observations. Comparing the zeropoints obtained from the analysis of

the Landolt standard star fields with both filters, we find that

observations with the I/203 filter are approximately 0.3 mag deeper. Furthermore, the I/203 filter is closer to the Cousins

filters used were the same

in the 2002 and 2003 periods, the standard I filter used at WFI,

denominated Ic in 2002, was replaced shortly after the beginning

of the 2003 period by the so-called I/203 filter. As a result,

part of our observations carried out in 2003 were obtained with a

I filter different from that used for the rest of the

observations. Comparing the zeropoints obtained from the analysis of

the Landolt standard star fields with both filters, we find that

observations with the I/203 filter are approximately 0.3 mag deeper. Furthermore, the I/203 filter is closer to the Cousins ![]() filter, as shown by the lower value of the color terms. These were determined by solving the following equations for each standard star field observed:

filter, as shown by the lower value of the color terms. These were determined by solving the following equations for each standard star field observed:

| |

= | (1) | |

| = | (2) | ||

| = | (3) |

where r, i203, and ic are instrumental magnitude measurements in the R, I/203, and Ic filters; Cr, Ci203, and

| k''r | = | ||

| k''i203 | = | ||

| = |

These average values were then used to recompute the nightly zeropoints for each individual field.

Since the goal of our observations is to characterize the low-mass population of the Lupus clouds, the long exposure times used lead to detector saturation even at relatively faint magnitudes. Table 1 lists both the saturation magnitudes in each filter and approximate 3![]() detection limits. Moderate variations within the 0.2 mag level in these values occur from field to field due to the different external conditions under which our observations were carried out.

detection limits. Moderate variations within the 0.2 mag level in these values occur from field to field due to the different external conditions under which our observations were carried out.

Table 1:

Saturation limits and limiting magnitudes at 3![]() level.

level.

2.1.2

filter

filter

The calibration of the

![]() filter was carried out based on

observations of the star Wolf 629, which has been adopted

as a standard both in the Johnson-Cousins system, and in the Gunn

system used by the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (Fukugita et al. 1996). A cycle

of observations consisting of short

filter was carried out based on

observations of the star Wolf 629, which has been adopted

as a standard both in the Johnson-Cousins system, and in the Gunn

system used by the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (Fukugita et al. 1996). A cycle

of observations consisting of short

![]() exposures of the field

around Wolf 629 immediately followed by also short exposures at the

centers of the Lupus 1, 3, and 4 areas in the same filter was

obtained in order to set up a network of secondary standards in each

of the individual clouds. Each of the deep fields imaged in

exposures of the field

around Wolf 629 immediately followed by also short exposures at the

centers of the Lupus 1, 3, and 4 areas in the same filter was

obtained in order to set up a network of secondary standards in each

of the individual clouds. Each of the deep fields imaged in

![]() was then calibrated with reference to this shallow

exposure. For the fields where an overlap region with the shallow

exposure on the center of the field existed, bright, unsaturated

stars in the area of overlap were used. For fields farther from the

cloud center not overlapping with the shallow reference exposure,

cross-calibration was achieved by using stars in the overlap region

with contiguous fields, which typically provided a few hundred

suitable stars in common.

was then calibrated with reference to this shallow

exposure. For the fields where an overlap region with the shallow

exposure on the center of the field existed, bright, unsaturated

stars in the area of overlap were used. For fields farther from the

cloud center not overlapping with the shallow reference exposure,

cross-calibration was achieved by using stars in the overlap region

with contiguous fields, which typically provided a few hundred

suitable stars in common.

The

![]() filter is characterized by an effective wavelength of

957 nm, which is somewhat longer than that of the Gunn z' filter

(911.4 nm), and a width of 53.4 nm. Using the STIS

spectrophotometric calibration of Vega (Bohlin & Gilliland 2004), the flux at

zero magnitude at the effective wavelength of the

filter is characterized by an effective wavelength of

957 nm, which is somewhat longer than that of the Gunn z' filter

(911.4 nm), and a width of 53.4 nm. Using the STIS

spectrophotometric calibration of Vega (Bohlin & Gilliland 2004), the flux at

zero magnitude at the effective wavelength of the

![]() filter

was determined to be

filter

was determined to be

![]() W cm-2 s-1

W cm-2 s-1 ![]() m. The magnitude of Wolf 629 in that filter was then determined using its Gunn r', i', and z' photometry as given in Smith et al. (2002) and a template M4 star spectrum, thus obtaining

m. The magnitude of Wolf 629 in that filter was then determined using its Gunn r', i', and z' photometry as given in Smith et al. (2002) and a template M4 star spectrum, thus obtaining

![]() .

.

2.1.3 Final catalog including 2MASS data

Three merged catalogs (one for each of the observed clouds) with position and photometry, as well as the date of the observation in each filter, were produced. For each star appearing in more than one field, the entry corresponding to the field where its angular distance to the field center was smaller was retained, rather than averaging the magnitudes derived in each field. This was preferred in order to reduce the effects of the higher uncertainty of the illumination correction towards the edges of the fields.

Each entry in the catalog was further complemented with near-infrared JHKS photometry by cross-matching it with the 2MASS Point Source Catalog (Skrutskie et al. 2006). A matching radius of 2'' was defined, which appears to be by far sufficient given that in all fields over 94% of the matches corresponded to differences between the 2MASS positions and those determined by us of less than 1''. When more than one 2MASS source was found within the 2'' circle, the one closer to the position derived from our observations was chosen as the counterpart.

Table 2 gives bulk numbers reflecting the contents

of our catalogs. In total, our observations contain nearly 1.4

million objects for which the magnitude in at least one of the R,

I, or

![]() filters has been measured, and 157 415 for which

six-band photometry from 0.6 to 2.2

filters has been measured, and 157 415 for which

six-band photometry from 0.6 to 2.2 ![]() m is available. The numbers

given in Table 2 show the ability of our

observations to image sources too faint to be detected by 2MASS, as

only 15% of the sources that we detect in all three WFI filters

have a counterpart detected in 2MASS. The catalogs used in this

study are available from the authors upon request.

m is available. The numbers

given in Table 2 show the ability of our

observations to image sources too faint to be detected by 2MASS, as

only 15% of the sources that we detect in all three WFI filters

have a counterpart detected in 2MASS. The catalogs used in this

study are available from the authors upon request.

Table 2: Number of sources for which photometry is available.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=7.5cm,clip]{1771f01.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/24/aa11771-09/Timg51.png) |

Figure 1: Photometric errors versus magnitudes and relative exponential fits for all the point-like sources detected in Lupus 3. The ``multiple sequence'' is due to different seeing conditions during the observation of the different fields. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

3 Analysis

The multiband photometry available from the merging of our

observations and the 2MASS Point Source Catalog enables a highly

reliable determination of the spectral energy distributions of a

vast number of objects covering a sizeable fraction of the volume of

the star-forming regions in Lupus 1, 3 and 4. The available

wavelength range from the ![]() to the KS bands samples the peak

emission of cool, low mass objects. We thus expect the flux

in all these bands to be generally dominated by photospheric emission,

although exceptions due to veiling, emission lines or warm circumstellar

dust may exist as discussed in Sect. 4. The long

wavelength baseline makes it possible to disentangle the intrinsic

spectral energy distribution from the reddening effects caused by

dust associated to the host clouds along the line of sight. Finally,

the effects of extinction in those bands are expected to be

relatively small taking into account the moderate extinction levels

present in the observed regions (Cambrésy 1999).

to the KS bands samples the peak

emission of cool, low mass objects. We thus expect the flux

in all these bands to be generally dominated by photospheric emission,

although exceptions due to veiling, emission lines or warm circumstellar

dust may exist as discussed in Sect. 4. The long

wavelength baseline makes it possible to disentangle the intrinsic

spectral energy distribution from the reddening effects caused by

dust associated to the host clouds along the line of sight. Finally,

the effects of extinction in those bands are expected to be

relatively small taking into account the moderate extinction levels

present in the observed regions (Cambrésy 1999).

As noted in Sect. 2.1.3, the depth of our WFI observations

is such that nearly 85% of the sources detected in them are too

faint to appear in the 2MASS catalog. On the other hand, wavelength

coverage restricted to the

![]() bands is too limited to

carry out a reliable simultaneous fit of the spectral energy

distribution and the foreground reddening, thus preventing us from

determining the characteristics of these faint sources in the same

way as we do for those for which photometric data extend to the

near-infrared. We thus preferred to confine this study to the

portion of our source catalog for which at least complete

bands is too limited to

carry out a reliable simultaneous fit of the spectral energy

distribution and the foreground reddening, thus preventing us from

determining the characteristics of these faint sources in the same

way as we do for those for which photometric data extend to the

near-infrared. We thus preferred to confine this study to the

portion of our source catalog for which at least complete

![]() coverage is available, as our results indicate that

a fit in the 0.8-2.2

coverage is available, as our results indicate that

a fit in the 0.8-2.2 ![]() m interval is the minimum required for a

reliable determination of the intrinsic spectral energy distribution.

Whenever available we also use the flux measured at

m interval is the minimum required for a

reliable determination of the intrinsic spectral energy distribution.

Whenever available we also use the flux measured at ![]() to improve

the reliability of the fit. The requirement of having 2MASS

measurements available is likely to leave out of the current analysis

some interesting very low mass members of the Lupus clouds, which we are

not able to reliably identify as such on the basis of the

to improve

the reliability of the fit. The requirement of having 2MASS

measurements available is likely to leave out of the current analysis

some interesting very low mass members of the Lupus clouds, which we are

not able to reliably identify as such on the basis of the

![]() data alone. The identification of the lowest-mass population of the clouds

potentially detected in our WFI survey using the same methodology described in this paper is thus deferred to further work making use of deeper near-infrared photometry.

data alone. The identification of the lowest-mass population of the clouds

potentially detected in our WFI survey using the same methodology described in this paper is thus deferred to further work making use of deeper near-infrared photometry.

Although limited to sources for which photometry between 0.6/0.8 and

2.2 ![]() m is available, the sensitivity of the combined WFI and 2MASS data is sufficient to probe deep into the substellar mass function of the Lupus clouds. At the 2MASS limiting magnitude of

m is available, the sensitivity of the combined WFI and 2MASS data is sufficient to probe deep into the substellar mass function of the Lupus clouds. At the 2MASS limiting magnitude of

![]() ,

assuming as typical parameters for a source in Lupus 3 (probably the most distant of the three clouds) a distance of 200 pc, an age of 5 Myr, and an extinction AV = 5 mag, evolutionary models indicate that our survey should be able to detect brown dwarfs with masses down to 0.02

,

assuming as typical parameters for a source in Lupus 3 (probably the most distant of the three clouds) a distance of 200 pc, an age of 5 Myr, and an extinction AV = 5 mag, evolutionary models indicate that our survey should be able to detect brown dwarfs with masses down to 0.02 ![]() (Baraffe et al. 2003), having temperatures as low as 2400 K corresponding to a spectral type L0-L1 (Kirkpatrick 2005), and even cooler and later objects if their age is younger. On the other hand, for lightly reddened members the saturation limit is first reached in the R band, with the limit of

(Baraffe et al. 2003), having temperatures as low as 2400 K corresponding to a spectral type L0-L1 (Kirkpatrick 2005), and even cooler and later objects if their age is younger. On the other hand, for lightly reddened members the saturation limit is first reached in the R band, with the limit of

![]() given in Table 1 corresponding to an unreddened star of 0.6

given in Table 1 corresponding to an unreddened star of 0.6 ![]() and 5 Myr age at the distance of the nearest cloud, Lupus 1, with a temperature of

and 5 Myr age at the distance of the nearest cloud, Lupus 1, with a temperature of ![]() 3600 K and spectral type M1 (Luhman et al. 2003). While the actual limits vary depending on the actual age, distance, and extinction, the dynamic range of the merged WFI/2MASS photometry thus samples well the very low mass stellar and massive brown dwarf domains and the early-M to early-L spectral type interval.

3600 K and spectral type M1 (Luhman et al. 2003). While the actual limits vary depending on the actual age, distance, and extinction, the dynamic range of the merged WFI/2MASS photometry thus samples well the very low mass stellar and massive brown dwarf domains and the early-M to early-L spectral type interval.

3.1 Temperature and luminosity fits

The procedure that we used to estimate the individual

temperature and luminosity of each object is based on the

simultaneous fit of all the measured broad-band fluxes to model

spectra of cool stellar and substellar photospheres, and is similar

to that used by Spezzi et al. (2007) in their study of the stellar

population in Chamaeleon II. The grid of reference model spectra

used is that of Hauschildt et al. (1999) and Allard et al. (2000), covering the

effective temperature (

![]() )

range 1700 K-10 000 K. A single

value of the surface gravity,

)

range 1700 K-10 000 K. A single

value of the surface gravity,

![]() ,

was chosen as being

representative of very low mass stars and brown dwarfs, since

broad-band colors have only a mild dependency on the actual surface

gravity in this range. Using the flux per unit of stellar surface

provided by the synthetic spectra, absolute magnitudes in each of

the filters used,

,

was chosen as being

representative of very low mass stars and brown dwarfs, since

broad-band colors have only a mild dependency on the actual surface

gravity in this range. Using the flux per unit of stellar surface

provided by the synthetic spectra, absolute magnitudes in each of

the filters used,

![]() ,

are obtained for fiducial

stars of different

,

are obtained for fiducial

stars of different

![]() ,

each with a radius arbitrarily set to

1

,

each with a radius arbitrarily set to

1 ![]() .

The observed magnitude

.

The observed magnitude

![]() at each band

can then be expressed as

at each band

can then be expressed as

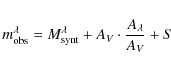

where AV is the foreground extinction in the visible,

The ratio

Assuming a certain input value of

![]() for a star, one equation

like Eq. (4) can be set for each photometric band.

These equations form an overdetermined system with the two

unknowns

for a star, one equation

like Eq. (4) can be set for each photometric band.

These equations form an overdetermined system with the two

unknowns ![]() and S, which can be solved by least squares. The

temperature that minimizes the residual of the fit is then taken as

the temperature of the object, and the luminosity L is derived

from the value of S obtained for the best fitting temperature as

and S, which can be solved by least squares. The

temperature that minimizes the residual of the fit is then taken as

the temperature of the object, and the luminosity L is derived

from the value of S obtained for the best fitting temperature as

![]() ,

where

,

where ![]() is the

Stefan-Boltzmann constant. The residuals for this best fit give in

turn an estimate of the quality of the solution. It should be in

principle possible to obtain a more reliable fit by weighting each equation by the inverse of the magnitude uncertainty,

is the

Stefan-Boltzmann constant. The residuals for this best fit give in

turn an estimate of the quality of the solution. It should be in

principle possible to obtain a more reliable fit by weighting each equation by the inverse of the magnitude uncertainty,

![]() .

However, we

preferred not to use such weights, which are composed of the

random measurement error and a possible systematic error caused by

shortcomings in the models. The latter is poorly known, but it is

likely to dominate especially at infrared wavelengths where the

objects are brightest and the magnitude uncertainty is very small.

We carried out numerical experiments comparing the results

obtained for known cloud members with well constrained temperatures,

where we computed their temperatures by solving the system of

Eqs. (4) either without weighting them, or by weighting them with the inverse of the photometric uncertainty alone. In general we find a better match in the non-weighted results, seemingly confirming our suspicion that systematic errors dominate over the photometric ones.

.

However, we

preferred not to use such weights, which are composed of the

random measurement error and a possible systematic error caused by

shortcomings in the models. The latter is poorly known, but it is

likely to dominate especially at infrared wavelengths where the

objects are brightest and the magnitude uncertainty is very small.

We carried out numerical experiments comparing the results

obtained for known cloud members with well constrained temperatures,

where we computed their temperatures by solving the system of

Eqs. (4) either without weighting them, or by weighting them with the inverse of the photometric uncertainty alone. In general we find a better match in the non-weighted results, seemingly confirming our suspicion that systematic errors dominate over the photometric ones.

The best-fitting

![]() derived for each star, and the

corresponding values of

derived for each star, and the

corresponding values of ![]() and S, are expected to be close to their true values regardless of whether or not the object is a member of the star-forming region, since the

colors of young stellar objects, main sequence late dwarfs, and cool

giants of a given temperature are to a first approximation similar.

On the other hand, it is straightforward to transform S into the

luminosity if the object is a member of the star-forming region. For

background and foreground members, the luminosity remains however

undetermined due to their unknown distances.

and S, are expected to be close to their true values regardless of whether or not the object is a member of the star-forming region, since the

colors of young stellar objects, main sequence late dwarfs, and cool

giants of a given temperature are to a first approximation similar.

On the other hand, it is straightforward to transform S into the

luminosity if the object is a member of the star-forming region. For

background and foreground members, the luminosity remains however

undetermined due to their unknown distances.

The suitability of the wavelength range used to sample the spectral energy distribution of the objects of interest is illustrated in Fig. 2, where we show the fit of the photometric data points to the reddened synthetic spectrum of a

![]() K photosphere. The pronounced change of slope of the spectral energy distribution in the region around its peak allows us to reliably disentangle the effect of temperature from that of extinction.

K photosphere. The pronounced change of slope of the spectral energy distribution in the region around its peak allows us to reliably disentangle the effect of temperature from that of extinction.

The residuals of the spectral energy distribution fits are used to estimate their quality. After producing fits for all the sources in our sample, we find that 87% of them yield averages residuals below 0.2 mag, which we consider of good quality in view of the accuracy of our photometry. The percentage actually varies between 86% for Lupus 3 and 4, and 91% for Lupus 1. The reason is mainly the higher galactic latitude of the latter, which leads to a smaller number of close pairs not disentangled by our automatic photometry. Poor fits are also obtained for variable sources due to the non-simultaneity of the photometry, as we discuss in Sect. 4. The extinction is derived to a typical accuracy of

![]() mag, and the luminosity to

mag, and the luminosity to

![]() .

As discussed in Sect. 4, the accuracy in the determination of the temperature is estimated to be

.

As discussed in Sect. 4, the accuracy in the determination of the temperature is estimated to be ![]() 200 K in the range of temperatures of interest,

200 K in the range of temperatures of interest,

![]() K.

K.

It must be stressed that, whereas the method described here can be efficiently used to derive parameters of cool stars in the field, it is not intended to provide by itself a membership criterion. However, under certain circumstances that we describe in Sect. 5 the value of S can be used as a strong indicator of membership within a certain range of distances and ages.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[height=8.5cm,angle=-90,clip]{1771f02.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/24/aa11771-09/Timg78.png) |

Figure 2:

Example of the fit of the

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

3.2 Estimating the contamination

The derivation of the best-fitting values of

![]() and S for

each star allows us to plot them in a diagram that is closely linked

to the commonly used L vs.

and S for

each star allows us to plot them in a diagram that is closely linked

to the commonly used L vs.

![]() diagram in the case of members

of the star-forming region. It is also easy to convert theoretical isochrones and evolutionary tracks so that ages and masses of the members can be determined by relation to them. In this diagram, the isochrones delimiting the age range set by the time span in which the aggregate has been forming stars can be expressed as

diagram in the case of members

of the star-forming region. It is also easy to convert theoretical isochrones and evolutionary tracks so that ages and masses of the members can be determined by relation to them. In this diagram, the isochrones delimiting the age range set by the time span in which the aggregate has been forming stars can be expressed as

![]() and

and

![]() ,

where

,

where

![]() and

and

![]() are respectively the ages of the youngest and oldest members of the aggregate. All members of the aggregate are thus expected to be found in the band defined by these isochrones. This is illustrated in Fig. 3, where the position of all the stars for which

are respectively the ages of the youngest and oldest members of the aggregate. All members of the aggregate are thus expected to be found in the band defined by these isochrones. This is illustrated in Fig. 3, where the position of all the stars for which

![]() and S can be determined in the field of Lupus 3 are plotted together with two representative isochrones. For the latter we used the evolutionary tracks of Baraffe et al. (1998) for stellar masses down to 0.075

and S can be determined in the field of Lupus 3 are plotted together with two representative isochrones. For the latter we used the evolutionary tracks of Baraffe et al. (1998) for stellar masses down to 0.075 ![]() ,

and the models allowing dust formation in the photosphere of Chabrier et al. (2000) for substellar masses.

,

and the models allowing dust formation in the photosphere of Chabrier et al. (2000) for substellar masses.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=6.5cm,angle=-90]{1771f03.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/24/aa11771-09/Timg83.png) |

Figure 3:

S vs.

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

The band occupied by members of the aggregate may be expected to be populated also by foreground and background stars of similar temperature, whose D/R ratios lead to a value of S within the same range. In the cool temperature range of interest in this work, these potential contaminants are split into two well separated categories with similar temperatures but very different luminosities. Foreground sources are expected to be main sequence cool dwarfs, whereas red giants are expected to dominate the background population. This is most clearly seen at the lowest temperatures shown in Fig. 3.

3.2.1 Main sequence contamination

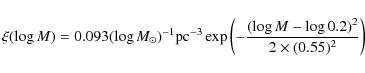

To estimate the number of main sequence contaminants we used the log-normal local initial mass function of Chabrier (2005), assuming that all foreground stars at a given

![]() are on the main sequence and thus have a well-defined

are on the main sequence and thus have a well-defined

![]() vs. mass relationship, which we derive from the 5 Gyr isochrone from Baraffe et al. (1998). The number of stars per logarithmic mass (M) interval that enter the region between S1 and S2 in an area of the sky that subtends an angle

vs. mass relationship, which we derive from the 5 Gyr isochrone from Baraffe et al. (1998). The number of stars per logarithmic mass (M) interval that enter the region between S1 and S2 in an area of the sky that subtends an angle ![]() is then

is then

![\begin{displaymath}\frac{{\rm d}N(M)}{{\rm d} \log M} = \frac{1}{3} \ \xi (\log ...

... R^3(M) 10^3

\bigl[10^{0.6 S_2} - 10^{0.6 S_1} \bigr] \ \Omega

\end{displaymath}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/24/aa11771-09/img85.png) |

(6) |

where R(M) is the stellar radius in units of

|

(7) |

with the mass given in

Table 3:

Expected numbers of non-members in the Lupus

![]() - S locus.

- S locus.

Some illustrative results are presented in Table 3, where the number of contaminants expected up to a certain temperature in each region is given. The upper part of the table shows that the number of foreground stars with both

![]() and S in the range covered by members of the clouds with ages between 1 and 20 Myr is in general small. The expected foreground contamination in Lupus 3 is somewhat stronger due to the greater distance assumed for this cloud, which moves the isochrones down by 0.6 mag in S. However, this is also the most densely populated cloud according to previous studies, and the contamination is thus lower in relative terms.

and S in the range covered by members of the clouds with ages between 1 and 20 Myr is in general small. The expected foreground contamination in Lupus 3 is somewhat stronger due to the greater distance assumed for this cloud, which moves the isochrones down by 0.6 mag in S. However, this is also the most densely populated cloud according to previous studies, and the contamination is thus lower in relative terms.

3.2.2 Background cool stars

We estimated the expected level of background contamination using the volume density laws for the different galactic structural components described by Wainscoat et al. (1992). Red giant stars dominate the background contribution to the star counts in the direction of Lupus. We adopted for these stars the effective

temperatures and radii from Fluks (1998). As in the case of foreground stars, background cool giants at a given

![]() and radius appear in the region of the

and radius appear in the region of the

![]() ,

S) diagram occupied by cloud members if they lie within a range of distances set by those intrinsic properties, the distance of the clouds, and the limiting isochrones of cloud members. To estimate the background contribution we thus integrated the volume density seen in the direction of each cloud over this distance range.

,

S) diagram occupied by cloud members if they lie within a range of distances set by those intrinsic properties, the distance of the clouds, and the limiting isochrones of cloud members. To estimate the background contribution we thus integrated the volume density seen in the direction of each cloud over this distance range.

The results are also presented in Table 3. The most obvious feature when comparing

the background contamination towards each cloud is the much higher level expected in Lupus 3 and 4, which is a consequence of their lower galactic latitude (

![]() and

and

![]() for Lupus 3 and 4 respectively, as compared to

for Lupus 3 and 4 respectively, as compared to

![]() 5 for Lupus 1). Also noticeable is the great decrease in the number of background stars above the isochrone corresponding to the oldest stars in the clouds when the temperature range is reduced from T < 3500 K to

5 for Lupus 1). Also noticeable is the great decrease in the number of background stars above the isochrone corresponding to the oldest stars in the clouds when the temperature range is reduced from T < 3500 K to

![]() K. This is due to the fact that red

giants in the

K. This is due to the fact that red

giants in the

![]() range (corresponding to early M spectral types) having values of S in the range covered by Lupus cloud members are located in dense regions of the galactic bulge in that direction. Conversely, as we move towards cooler and intrinsically brighter stars above the oldest limiting isochrone, the contributors with S values in the proper range are located in more remote regions of the Galaxy, where they are rarer. Remarkably, for

range (corresponding to early M spectral types) having values of S in the range covered by Lupus cloud members are located in dense regions of the galactic bulge in that direction. Conversely, as we move towards cooler and intrinsically brighter stars above the oldest limiting isochrone, the contributors with S values in the proper range are located in more remote regions of the Galaxy, where they are rarer. Remarkably, for

![]() K almost no background stars are

expected to be found in the locus occupied by Lupus members with ages between 1 and 20 Myr, since nearly all such background stars appear much brighter than Lupus members of the same

K almost no background stars are

expected to be found in the locus occupied by Lupus members with ages between 1 and 20 Myr, since nearly all such background stars appear much brighter than Lupus members of the same

![]() .

This is seen in the results of Oliveira et al. (2009), who spectroscopically confirm that the brightest cool stars in the direction of the Serpens star-forming region are background giants. Our case is more favorable in terms of the numbers of such background giants expected, given the higher galactic latitude of Lupus.

.

This is seen in the results of Oliveira et al. (2009), who spectroscopically confirm that the brightest cool stars in the direction of the Serpens star-forming region are background giants. Our case is more favorable in terms of the numbers of such background giants expected, given the higher galactic latitude of Lupus.

We thus conclude that only foreground cool main sequence stars can contribute noticeably to the contamination of the locus of Lupus cloud members, and they are expected to do so in numbers similar to those given in Table 3. A more detailed analysis is presented in Sect. 5, allowing us to produce lists of reliable candidate members of each region.

It must be noted that a particular complication in the interpretation of the census of Lupus is due to the existence of an additional component to those characterized above. By analyzing the results of the ROSAT All-Sky Survey in the direction of Lupus and other regions of the sky and carrying out follow-up spectroscopy, Krautter et al. (1997) noted the existence of an older, extended population of weak-line T Tauri stars. This population is not particularly concentrated towards the clouds, and an analysis of its large-scale distribution rather links it to the Gould Belt (Wichmann et al. 1997). If the weak-line T Tauri stars in Lupus are at the same distance as the Lupus clouds, as suggested by Wichmann et al. (1997), their older ages should place them below the oldest limiting isochrone, thus making it easy to reject them as possible members. However, studies of the distribution of weak-line T Tauri stars across the Gould Belt by Guillout et al. (1998) rather indicate that these stars span a wide range in distance towards any given direction. Their results further suggest that the Lupus clouds lie near the far end of this distance range in that direction of the sky, with most of the weak-line T Tauri stars being foreground and extending to distances as close as 30 pc from the Sun. Foreground old T Tauri stars unrelated to the Lupus clouds can thus have S values in the range expected for true cloud members, and thus be photometrically indistinguishable from them. The possible influence of the presence of this component on our results will be discussed in Sect. 6.

4 The known members of the Lupus clouds

The many studies carried out over the last decades dealing with the identification and characterization of the stellar and substellar population of the Lupus clouds has provided an abundant census of members. For many of them detailed information on circumstellar environment, intrinsic properties of the central source, or variability is available, thus providing a sound basis to test the validity of the methods outlined in Sect. 3.1.

A compilation of all known members of Lupus 1, 3, and 4, selected by different techniques, has been presented by Merín et al. (2008), who also estimated the spectral type, luminosity, and foreground extinction for most objects based on photometric fits to synthetic spectra, using a procedure similar to ours. The

![]() photometry data that they used are the same as in this paper, complemented with data from the literature for saturated sources.

photometry data that they used are the same as in this paper, complemented with data from the literature for saturated sources.

The derived parameters for the known members of each cloud that

are detected and unsaturated in at least ![]() and

and

![]() are presented in Table 4. It may be noted that Table 4

does not represent a validation of membership based on our new data, but only a derivation of parameters of objects already known to be members from their youth signatures, based on the method described in Sect. 3. For most of the objects we obtain low temperatures, and luminosities and ages consistent with

their membership in the Lupus clouds. The vast majority of objects in

Merín et al. (2008) are detected in our WFI observations, with some exceptions that we list in Table 5. As expected, the comparison shows that our visible/red survey is particularly incomplete near the high extinction regions of the clouds, most notably Lupus 3, where members are too deeply embedded to be detectable at short wavelengths. Other objects are close to bright sources or their associated nebulosity, outside the field surveyed with WFI or, in a few cases, misclassified as a stellar object whereas the WFI images show it to be a resolved galaxy.

are presented in Table 4. It may be noted that Table 4

does not represent a validation of membership based on our new data, but only a derivation of parameters of objects already known to be members from their youth signatures, based on the method described in Sect. 3. For most of the objects we obtain low temperatures, and luminosities and ages consistent with

their membership in the Lupus clouds. The vast majority of objects in

Merín et al. (2008) are detected in our WFI observations, with some exceptions that we list in Table 5. As expected, the comparison shows that our visible/red survey is particularly incomplete near the high extinction regions of the clouds, most notably Lupus 3, where members are too deeply embedded to be detectable at short wavelengths. Other objects are close to bright sources or their associated nebulosity, outside the field surveyed with WFI or, in a few cases, misclassified as a stellar object whereas the WFI images show it to be a resolved galaxy.

Table 5: Objects classified as candidate Lupus members by Merín et al. (2008) for which no fits are obtained.

The availability of spectral classifications for many of the objects

listed in Table 4 provides a check on our derived

temperatures. The result of the comparison is presented in

Fig. 4, where we also plot the spectral type vs.

effective temperature relationships derived by Luhman et al. (2003) for

M-type young stellar objects, and by Kenyon & Hartmann (1995) for main sequence

stars of types K and M. The relative abundance of spectral

types later than M0 in the diagram is due to earlier types being

generally saturated in our observations, and is not related to the

overabundance of mid-M types reported by Hughes et al. (1994). We excluded

from the comparison the objects in Table 4 showing evidence of

variability as indicated in the notes at the end of the table. Since our

observations in ![]() and

and ![]() were obtained at epochs generally

different from those in

were obtained at epochs generally

different from those in

![]() ,

and were combined with 2MASS

JHKS photometry obtained on a yet different epoch, the fit to the

spectral energy distribution for variable sources is not meaningful. This

is the most likely cause of the relative large fraction of poor fits with a high residual that we obtain among the known members of the clouds.

,

and were combined with 2MASS

JHKS photometry obtained on a yet different epoch, the fit to the

spectral energy distribution for variable sources is not meaningful. This

is the most likely cause of the relative large fraction of poor fits with a high residual that we obtain among the known members of the clouds.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=-90,width=8.5cm,clip]{1771f04.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/24/aa11771-09/Timg95.png) |

Figure 4:

Comparison between the temperatures obtained with our

fitting procedure and the published spectral types of known members

of the Lupus clouds (Table 4). Stars known to display

photometric variability are excluded from the plot. The outlier near

the upper right corner is Lup 654. For SSTc2d160815.0-385715, which is

characterized by a noticeable near-infrared excess, we used

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

The appearance of Fig. 4 shows a distinct

distribution with most of the objects used for the comparison

clustering along the expected spectral type-temperature

relationship, whereas some objects appear as clear outliers for

which we estimate temperatures well above those expected from their

spectral types. Part of the temperature scatter at any given

spectral type is undoubtedly due to the limited accuracy with which

the temperature can be determined by our fits. However, the

different techniques and wavelength ranges used to determine

spectral types in different studies are likely

to play a role as well. We note in this regard that most of the

later stars for which the spectral type is taken from Hughes et al. (1994) lie

below the spectral type vs.

![]() calibration. As shown

by Comerón et al. (2003), the spectral types in that study tend to

systematically differ by about 2 subtypes from those determined by

Hughes et al. (1994), in the sense of the Comerón et al. (2003) types being later.

The latter authors tentatively attribute the difference to their use

of a redder spectral region, less affected by veiling and more

suitable for classification based on the shapes of the TiO and VO molecular bands. The application of a correction by two spectral

subtypes to the classifications of Hughes et al. (1994) indeed improves their

agreement with the calibration beyond M3. On the other hand, we include

in Table 4 the classification of López Martí et al. (2005) that

is based on intermediate-band photometry of a single selected

temperature-dependent spectral feature, being therefore less

accurate than an actual spectral classification. The comparison to

the calibrations suggests that the spectral types assigned by

López Martí et al. (2005) tend to be only slightly earlier than corresponding to the actual

temperature. Spectra obtained from the other sources listed at the

bottom of Table 4 are in general in better

agreement with the calibration.

calibration. As shown

by Comerón et al. (2003), the spectral types in that study tend to

systematically differ by about 2 subtypes from those determined by

Hughes et al. (1994), in the sense of the Comerón et al. (2003) types being later.

The latter authors tentatively attribute the difference to their use

of a redder spectral region, less affected by veiling and more

suitable for classification based on the shapes of the TiO and VO molecular bands. The application of a correction by two spectral

subtypes to the classifications of Hughes et al. (1994) indeed improves their

agreement with the calibration beyond M3. On the other hand, we include

in Table 4 the classification of López Martí et al. (2005) that

is based on intermediate-band photometry of a single selected

temperature-dependent spectral feature, being therefore less

accurate than an actual spectral classification. The comparison to

the calibrations suggests that the spectral types assigned by

López Martí et al. (2005) tend to be only slightly earlier than corresponding to the actual

temperature. Spectra obtained from the other sources listed at the

bottom of Table 4 are in general in better

agreement with the calibration.

Table 6:

Fits to

![]() photometry of stars with suspected veiling.

photometry of stars with suspected veiling.

Table 7:

Fits to

![]() photometry of stars with suspected infrared excess.

photometry of stars with suspected infrared excess.

The outliers in Fig. 4 are Lup 654, classified by

López Martí et al. (2005) as L1 but for which we fit a temperature of

![]() K;

and, to a lesser extent, the M 5 star SSTc2dJ160853.7-391437, for which we obtain

K;

and, to a lesser extent, the M 5 star SSTc2dJ160853.7-391437, for which we obtain

![]() K. No variability information exists for either of these

objects, which leaves variability as a possible reason for a temperature

overestimate as discussed later in this Section. The rather high values of extinction needed to fit the spectral energy distribution of both object, particularly

SSTc2dJ160853.7-391437, hint at an overestimate of the temperature by our method.

For this latter object, Allen et al. (2007) note the presence of emission lines, which

may hint at veiling or the contribution of the H

K. No variability information exists for either of these

objects, which leaves variability as a possible reason for a temperature

overestimate as discussed later in this Section. The rather high values of extinction needed to fit the spectral energy distribution of both object, particularly

SSTc2dJ160853.7-391437, hint at an overestimate of the temperature by our method.

For this latter object, Allen et al. (2007) note the presence of emission lines, which

may hint at veiling or the contribution of the H![]() emission to the

emission to the ![]() -band

flux as another possible cause for an incorrect fit. Finally, a

rather large departure from the spectral type vs. temperature calibration is noted for

SSTc2d160815.0-385715, an object for which Allen et al. (2007) note a strong

near-infrared excess which is supported by our fits when the KS measurement

is excluded. The still significant deviation from the expected temperature for

its M4.75 spectral type may indicate that other effects may be still present.

Still, a low-residual fit (<0.2 mag rms) can be attained for these three objects.

-band

flux as another possible cause for an incorrect fit. Finally, a

rather large departure from the spectral type vs. temperature calibration is noted for

SSTc2d160815.0-385715, an object for which Allen et al. (2007) note a strong

near-infrared excess which is supported by our fits when the KS measurement

is excluded. The still significant deviation from the expected temperature for

its M4.75 spectral type may indicate that other effects may be still present.

Still, a low-residual fit (<0.2 mag rms) can be attained for these three objects.

Among the objects classified as members in Table 4, we find some whose fitted luminosities appear to be inconsistent with membership in Lupus, apparently placing them near or below the main sequence. Most are located in Lupus 3, most likely just because of a size-of-the-sample effect since that cloud contains by far the richest aggregate. Out of the 86 Lupus 3 members for which we obtain a fit, nearly one third (26) are in this category. In at least two cases, Sz 102 and Par-Lup3-4, their underluminosity is well known. It may be explained by the fact that these objects are surrounded by abundant circumstellar material and display jets moving in a direction that is close to the plane of the sky, suggesting substantial obscuration of the central object by a disk seen close to an edge-on orientation (Graham & Heyer 1988; Fernández & Comerón 2005).

Another possible explanation is that the spectral energy distributions of some other objects may be