| Issue |

A&A

Volume 500, Number 3, June IV 2009

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Page(s) | 1271 - 1276 | |

| Section | Astronomical instrumentation | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/200811119 | |

| Published online | 16 April 2009 | |

First single star scidar measurements at Dome C, Antarctica

J. Vernin - M. Chadid - E. Aristidi - A. Agabi - H. Trinquet - M. Van der Swaelmen

Laboratoire H. Fizeau, UMR6525, Université de Nice, Observatoire de la Côte d'Azur, Parc Valrose, 06108 Nice - France

Received 9 October 2008 / Accepted 30 January 2009

Abstract

Aims. We investigate the first operational running of the Single Star Scidar (SSS instrument) under harsh weather conditions at Dome C in Antarctica and examine continuous monitoring of the optical turbulence and wind speed profiles throughout the atmosphere.

Methods. SSS is mainly composed of commercially available light-weight components and a 16 inch telescope installed on an equatorial mount. Scintillation patterns were computed (auto and cross-correlations) in real time and analyzed off line to retrieve continuously vertical profiles of optical turbulence CN2(h) and wind speed V(h), from the ground up to 20 km.

Results. Using a simulated annealing method, we have analyzed about 6.5 h of observations, revealing the strong surface layer contribution to seeing degradation. SSS results show a good seeing agreement with simultaneous measurements with a Differential Image Motion Monitor, even under very good seeing as low as 0.2 arcsec, as well as wind speed agreement when compared to the weather archive from NOAA.

Conclusions. SSS has shown its usefulness for site characterization since it simultaneously measures CN2 and V profiles, from which most adaptative optic parameters are deduced, such as isoplanatic angle and coherence time of the wavefront. Due to its small size, it is well adapted for site characterization, even when low infrastructure is available.

Key words: atmospheric effects - site testing - turbulence - instrumentation: detectors - methods: data analysis - methods: observational

1 Introduction

Vernin et al. (2007) gave a brief history of site testing at Dome C, located on the high Antarctica plateau. Studies began in 1992, with a congress (Vernin 1994) organized by the French Académie des Sciences, and soon the decision was taken to begin a two-year site testing campaign at the South Pole. Marks et al. (1999) showed that most of the optical turbulence came from the 200 m boundary layer (BL) triggered by katabatic winds and this motivated the site testing campaign at Dome C where less katabatic winds were expected.

In 1995, one of us, Jean Vernin, participated in the first scientific expedition

to Dome C, but at that time no winter infrastructure was available. In 2005, the Astro-Concordia

station was first opened for winterover during which two DIMMs were set up and

40 meteorological balloons, instrumented for CN2(h) and

![]() profiling, were launched. Again, it became obvious that most of the turbulence was generated within the surface

layer (Agabi et al. 2006), as was found at the South Pole, but with a depth of only 30 m.

profiling, were launched. Again, it became obvious that most of the turbulence was generated within the surface

layer (Agabi et al. 2006), as was found at the South Pole, but with a depth of only 30 m.

There are very few instruments which are able to simultaneously retrieve CN2(h) and

![]() profiles from the ground level up to

profiles from the ground level up to

![]() km where the optical turbulence begins

to be negligible. To our knowledge, only

the Scidar family, i.e.the double star scidar (Vernin & Azouit 1983b,a) and the single star scidar

(Habib et al. 2006) and the instrumented balloon (Azouit & Vernin 2005) are

among these sound techniques.

The Multi Aperture

Scintillation Sensor (Kornilov et al. 2003) or MASS, delivers CN2 profiles along six slabs in the atmosphere, but

it does not give access to ground turbulence nor the wind speed at any altitude. Echo soundings (SODAR) are not

well calibrated in terms of CN2 since they require extra knowledge of the humidity

profile, and their altitude range is around

km where the optical turbulence begins

to be negligible. To our knowledge, only

the Scidar family, i.e.the double star scidar (Vernin & Azouit 1983b,a) and the single star scidar

(Habib et al. 2006) and the instrumented balloon (Azouit & Vernin 2005) are

among these sound techniques.

The Multi Aperture

Scintillation Sensor (Kornilov et al. 2003) or MASS, delivers CN2 profiles along six slabs in the atmosphere, but

it does not give access to ground turbulence nor the wind speed at any altitude. Echo soundings (SODAR) are not

well calibrated in terms of CN2 since they require extra knowledge of the humidity

profile, and their altitude range is around

![]() ,

which may have a serious impact

on site testing (Lawrence et al. 2004). SLODAR (Wilson 2002), based upon wavefront slope analysis on a double star, delivers

optical turbulent profiles. To our knowledge, there are no cross calibrations of the

SLODAR with other techniques or profiles of the wind speed.

,

which may have a serious impact

on site testing (Lawrence et al. 2004). SLODAR (Wilson 2002), based upon wavefront slope analysis on a double star, delivers

optical turbulent profiles. To our knowledge, there are no cross calibrations of the

SLODAR with other techniques or profiles of the wind speed.

Double Star Scidar requires at least a 1 to 1.5 m telescope since it uses a triangulation

method and the maximum reachable altitude

![]() is related to the

diameter D of the entrance

pupil through

is related to the

diameter D of the entrance

pupil through

![]() ,

where

,

where ![]() is the angular separation of the double star. If

one want to probe the atmosphere up to 20-25 km with double stars separated by 4-10 arcsec, such a

telescope is needed. The same argument applies also to the SLODAR technique. Instrumented balloons require a

great deal of ground infrastructure for balloon preparation, balloon launching and then for data reception, but

they can be operated even at new sites where no telescope is available. Thus, for the purpose of

investigation of new modern astronomical site one needs a light-weight experimental setup such as the Single Star Scidar, because it only requires a ``small'' 40 cm telescope.

is the angular separation of the double star. If

one want to probe the atmosphere up to 20-25 km with double stars separated by 4-10 arcsec, such a

telescope is needed. The same argument applies also to the SLODAR technique. Instrumented balloons require a

great deal of ground infrastructure for balloon preparation, balloon launching and then for data reception, but

they can be operated even at new sites where no telescope is available. Thus, for the purpose of

investigation of new modern astronomical site one needs a light-weight experimental setup such as the Single Star Scidar, because it only requires a ``small'' 40 cm telescope.

Here we present the first results obtained at Dome C in 2006 during the second polar winter. In Sect. 2 we present the instrument which was prepared to resist polar conditions. In Sect. 3 we detail the campaign of observations and in Sect. 4 the Single Star Scidar (SSS) results. In Sect. 5 the results are discussed and compared to other sources like DIMM and meteorological re-analysis from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

2 Instrument

As seen in Fig. 1, the SSS is made with standard components. The telescope is based on a Meade M 16

(40 cm diameter) Ritchey Chrétien optical combination supported by an Astro-Physics 1200 equatorial

mount. At the focus of the telescope, a collimating lens makes the beam parallel, as seen

in the optical scheme in Fig. 2. In order to make the low altitude layers

scintillate, one uses the ``generalized '' scidar mode (Fuchs et al. 1998) in which displacing the photoelectric

receiver by a distance ![]() along the optical axis, one introduces an extra altitude difference

along the optical axis, one introduces an extra altitude difference

![]() ,

where

,

where

![]() is the optical magnification.

is the optical magnification.

The photoelectric receiver is a Pixelfly CCD with a fast readout of

![]() images per second and a low readout noise

(

images per second and a low readout noise

(

![]() ). Auto-correlations and cross-correlations between images separated by

a temporal lag

). Auto-correlations and cross-correlations between images separated by

a temporal lag

![]() ,

,

![]() and

and

![]() ms are computed in real time

and averaged over

ms are computed in real time

and averaged over ![]() images.

In order to disentangle the broadening effect of the altitude and the

wind velocity fluctuations during the time to process the N images, two cross-correlations are necessary (more details are found in Habib et al. 2006).

images.

In order to disentangle the broadening effect of the altitude and the

wind velocity fluctuations during the time to process the N images, two cross-correlations are necessary (more details are found in Habib et al. 2006).

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm]{1119fig1}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/24/aa11119-08/Timg29.png) |

Figure 1: Installation of the SSS above one of the two plateforms at Dome C during polar summer 2005-2006. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

2.1 CN2 and V retrieval

To retrieve the respective vertical profiles of Cn2(h),

![]() and

and

![]() (the variance of wind speed fluctuations at altitude h), we use

a ``Simulated Annealing'' (SA) algorithm which is also described in Habib et al. (2006). Here,

we recall only that altitudes are sampled from 0 to 20 km, with a 1 km vertical resolution which

is about the natural vertical resolution of the SSS. Since the surface layer,

(the variance of wind speed fluctuations at altitude h), we use

a ``Simulated Annealing'' (SA) algorithm which is also described in Habib et al. (2006). Here,

we recall only that altitudes are sampled from 0 to 20 km, with a 1 km vertical resolution which

is about the natural vertical resolution of the SSS. Since the surface layer,

![]() thick,

is very turbulent (Trinquet et al. 2008) we gave the SA algorithm the possibility

of reconstructing four turbulent layers all situated at zero altitude, but with different

wind speed components

thick,

is very turbulent (Trinquet et al. 2008) we gave the SA algorithm the possibility

of reconstructing four turbulent layers all situated at zero altitude, but with different

wind speed components

![]() .

Knowing that the wind speed is increasing with altitude in the Ekman layer,

we sorted these four layers according to

increasing wind speed. Above this surface layer, the first reconstructed altitude is

1 km and then 2 km, 3 km up to 20 km. If the refractive index

structure constant is less than some threshold (

CN2 < 10-18 m-2/3), we assume that there is

not enough turbulence to detect it and to assess its velocity. When the wind speed is zero in the first slab of the four boundary turbulent layers, it is assumed that turbulence is relevant to ``mirror seeing'' and is removed from our analysis,

as already discussed by Avila et al. (2001). An ambiguity might remain if the velocity

of a boundary turbulent layer is less than the first detectable speed

.

Knowing that the wind speed is increasing with altitude in the Ekman layer,

we sorted these four layers according to

increasing wind speed. Above this surface layer, the first reconstructed altitude is

1 km and then 2 km, 3 km up to 20 km. If the refractive index

structure constant is less than some threshold (

CN2 < 10-18 m-2/3), we assume that there is

not enough turbulence to detect it and to assess its velocity. When the wind speed is zero in the first slab of the four boundary turbulent layers, it is assumed that turbulence is relevant to ``mirror seeing'' and is removed from our analysis,

as already discussed by Avila et al. (2001). An ambiguity might remain if the velocity

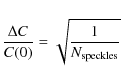

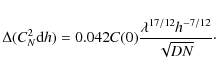

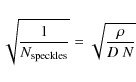

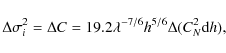

of a boundary turbulent layer is less than the first detectable speed ![]() given by:

given by:

|

(1) |

where

Six minutes of CPU time are required to compute vertical profiles of CN2, ![]() and

and

![]() deduced from the auto and cross-correlations averaged over a set of 2000 images, corresponding

to an acquisition time of about 14 s. This means that 180 h, i.e. one week, of CPU

(Opteron processor) time is required to

process 6 h of observations.

deduced from the auto and cross-correlations averaged over a set of 2000 images, corresponding

to an acquisition time of about 14 s. This means that 180 h, i.e. one week, of CPU

(Opteron processor) time is required to

process 6 h of observations.

| |

Figure 2:

Principle of the generalized SSS. After passing through the telescope, light is collimated by

a short focal lens. In order to make the low altitude layers scintillate, the photoelectric

receiver is displaced by a distance |

| Open with DEXTER | |

2.2 SSS detectivity

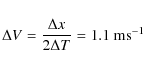

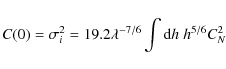

The detectivity of the SSS depends on the noise in the scintillation auto and cross-correlations. As expressed by Vernin & Azouit (1983b), the relative error on the correlation function is given by:where

|

(3) |

and

|

(4) |

where

|

(5) |

one can relate the SSS detectivity

This result allows us to determine the absolute error on the CN2(h) profile and which will be used later in the text.

3 Observations at Dome C in 2006

3.1 Description of the observing campaign

The SSS instrument was designed and constructed in our laboratory and sent to Dome C, Antarctica, lat.Observations began in March 2006, ending in September of the same year. For the reason explained in Sect. 2, we present here only one observing ``night'', on 20 March 2006, of 6.5 h with comparisons to other types of measurements.

3.2 C

N2(h), V(h) and

(h) profiles deduced from scintillation auto

and cross-correlations

(h) profiles deduced from scintillation auto

and cross-correlations

In Fig. 3, from left to right, an auto-correlation of the scintillation

moving pattern and the first and second cross-correlations, taken respectively at

![]() ms and

14 ms, are visible. In the second cross-correlation, several bumps are detected, each one corresponding to

a different turbulent layer. In Fig. 4, the same cross-correlation

computed at

ms and

14 ms, are visible. In the second cross-correlation, several bumps are detected, each one corresponding to

a different turbulent layer. In Fig. 4, the same cross-correlation

computed at

![]() ms, as in Fig. 3, and the theoretical reconstructed

cross-correlation at the end of the SA process have been plotted. All the bumps corresponding to

different turbulent layers are well detected.

ms, as in Fig. 3, and the theoretical reconstructed

cross-correlation at the end of the SA process have been plotted. All the bumps corresponding to

different turbulent layers are well detected.

| |

Figure 3:

From left to right, two-dimensional auto-correlation, first and second cross-correlation of the scintillation pattern on the 40 cm entrance pupil of the telescope

corresponding to time lags |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm]{1119fig4}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/24/aa11119-08/Timg52.png) |

Figure 4:

Measured temporal cross-correlation ( left) at |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=270,width=18cm]{1119fig5}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/24/aa11119-08/Timg55.png) |

Figure 5:

Top left: median vertical profile of the optical turbulence on a logarithmic

scale CN2(h)and

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

4 Results

In Fig. 5 top panel, we present the mean vertical profiles averaged over the whole ``night''

of 20 March. For clarity, the four first layers at zero altitude have been averaged. Almost all the optical turbulence

is concentrated within the surface layer, the rest being scattered through the free atmosphere, as

reported by Trinquet et al. (2008). The dash-dotted line represents the detectivity

of the SSS, as deduced from Eq. (6), with C(0)=0.1,

N = 2000,

![]() km and D = 0.4 m, which correspond to the observing conditions during this night.

Close to the BL, the detectivity is about

km and D = 0.4 m, which correspond to the observing conditions during this night.

Close to the BL, the detectivity is about

![]() ,

and less than 10-18 above,

in accordance with the threshold given in Sect. 2.1.

,

and less than 10-18 above,

in accordance with the threshold given in Sect. 2.1.

The wind speed, which corresponds to turbulent slabs, increases from ice level to reach 13 ms-1 at 8 km and remains stable above.

In Fig. 6, the temporal evolution of CN2(h) (top)

and

![]() (bottom) profiles during the same night are shown. For clarity, the free atmosphere

and surface layer are plotted separately, one on top and the other at the bottom of

each sub-figure. The first colored line, corresponding to a [0-1] km slab, refers to the

average of the four turbulent slabs which are detailed below. It is clear again that most

of the OT is concentrated within the surface layer, and that the free atmosphere is

quite stable.

(bottom) profiles during the same night are shown. For clarity, the free atmosphere

and surface layer are plotted separately, one on top and the other at the bottom of

each sub-figure. The first colored line, corresponding to a [0-1] km slab, refers to the

average of the four turbulent slabs which are detailed below. It is clear again that most

of the OT is concentrated within the surface layer, and that the free atmosphere is

quite stable.

Trinquet et al. (2008) & Roddier (1981) showed that, from the knowledge of both CN2(h)

and

![]() ,

one can compute

the seeing

,

one can compute

the seeing

![]() ,

the isoplanatic angle for adaptive optics

,

the isoplanatic angle for adaptive optics ![]() and

the coherence time

and

the coherence time ![]() for adaptive optics.

for adaptive optics.

It is clear that the greater r0, ![]() and

and ![]() ,

the better the conditions

for adaptive optics or interferometry. A more general approach is given by Lloyd (2004).

He defines a ``coherence étendue'' G0in which a photon remains coherent and which takes into account

a combination of Fried's radius, isoplanatic

angle and coherence time:

,

the better the conditions

for adaptive optics or interferometry. A more general approach is given by Lloyd (2004).

He defines a ``coherence étendue'' G0in which a photon remains coherent and which takes into account

a combination of Fried's radius, isoplanatic

angle and coherence time:

This new formulation shows a strong dependency on r0 and

From Fig. 7, one notes that the three variables, seeing, isoplanatic angle and coherence time vary on small time scales and with large amplitude.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=270,width=9cm]{1119fig6a}

\includegraphics[angle=270,width=9cm]{1119fig6b}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/24/aa11119-08/Timg60.png) |

Figure 6:

Temporal evolution of the optical turbulence

Cn2(h,t) ( top)

and of the wind speed modulus

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=270,width=9cm]{1119fig7}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/24/aa11119-08/Timg61.png) |

Figure 7:

From top left to bottom right: temporal evolution of the

seeing

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

5 Discussion

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=270,width=9cm]{1119fig8}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/24/aa11119-08/Timg62.png) |

Figure 8: Temporal evolution of seeing measured by SSS (red crosses) and DIMM (line) during 6.5 h on 20 March 2006. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

During the 2006 polar winter a DIMM (Agabi et al. 2006)

was operating on an other platform, 15 m away from the SSS platform, both at 8 m above ice level. The DIMM measures

the seeing continuously and it allows a direct comparison with SSS seeing measurements. In Fig. 8, the temporal

evolution of the seeing as measured by the DIMM (black line) and the SSS (red crosses) are

superimposed. Both instruments are

in very good agreement. From 17:15 to 17:30 some discrepancies are visible which

can be explained by the fact that the distance

between the two experiments, 15 m, is comparable to the thickness of the surface layer,

30 m, which accounts for 80% of the whole optical turbulence (Trinquet et al. 2008).

The overall good agreement means that SSS detects all the turbulent layers in a quantitative way. We recall

that SSS is an ``auto-calibrated'' instrument, where no calibration parameter is introduced.

This is related to the fact that the scintillation variance

![]() is auto-calibrated, by

definition, with the square of the mean flux

is auto-calibrated, by

definition, with the square of the mean flux

![]() .

In

Fig. 9 we plot the DIMM seeing v.s the SSS seeing. The slope of

the line is 0.97 with a 0.75 correlation coefficient. The regression slope is very close

to 1 and seeing amplitude variations of both DIMM and SSS are between 0.2-0.5 and

1.5-1.7 arcsec.The SSS is even able to detect very low turbulence conditions,

as shown in Fig. 10, where

the seeing lies around 0.2-0.3 arcsec.

.

In

Fig. 9 we plot the DIMM seeing v.s the SSS seeing. The slope of

the line is 0.97 with a 0.75 correlation coefficient. The regression slope is very close

to 1 and seeing amplitude variations of both DIMM and SSS are between 0.2-0.5 and

1.5-1.7 arcsec.The SSS is even able to detect very low turbulence conditions,

as shown in Fig. 10, where

the seeing lies around 0.2-0.3 arcsec.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=270,width=9cm]{1119fig9}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/24/aa11119-08/Timg65.png) |

Figure 9: Correlation between seeings measured by SSS and DIMM. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=270,width=9cm]{1119fig10}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/24/aa11119-08/Timg66.png) |

Figure 10: Temporal evolution of seeing measured by SSS (red crosses) and DIMM (line) during 0.5 h over 21 March 2006. 0.2 to 0.3 arcsec seeings are detected both by SSS and DIMM. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

In order to check for the validity of the wind speed deduced from SSS measurements,

we used the National Oceanic and

Atmospheric Administration re-analysis which is available on their web site

(http://www.arl.noaa.gov/READYcmet.php). NOAA profiles

are vertically sampled from ground level up to 26 km over 14 levels, starting

at 0 UT, and

every three hours a new

re-analysis is issued. The first level, or Surface Level,

corresponds to ![]() m above ground. In the bottom of Fig. 5, NOAA wind speed

and direction are plotted in green. Excellent agreement!

Fig. 11 gives a comparison of the temporal

evolution of the wind speed deduced from the first four levels of the SSS and the first two levels,

10m (rectangles) and 400 m (triangles) from the NOAA re-analysis. The wind speed at these

two levels are compatible with the second and third SSS levels, at the surface layer.

m above ground. In the bottom of Fig. 5, NOAA wind speed

and direction are plotted in green. Excellent agreement!

Fig. 11 gives a comparison of the temporal

evolution of the wind speed deduced from the first four levels of the SSS and the first two levels,

10m (rectangles) and 400 m (triangles) from the NOAA re-analysis. The wind speed at these

two levels are compatible with the second and third SSS levels, at the surface layer.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=270,width=9cm]{1119fig11}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/24/aa11119-08/Timg68.png) |

Figure 11:

Temporal evolution of the wind speed modulus deduced from SSS measurements in the four

layers within the boundary layer, with a one-hour sliding triangle convolution.

The two measurements from NOAA re-analysis at |

| Open with DEXTER | |

6 Conclusion

We have shown that the Single Star Scidar technique is extremely well suited for astronomical site characterization, even under he worst weather conditions on the high Antarctic plateau. The instrument is robust, reliable, well calibrated and allows the access of vertical profiles of both CN2(h) andSSS seeing measurements obtained for 6.5 h on 20 March 2006 are consistent with other optical experiment like DIMM, even under very low turbulence conditions. SSS wind speed profiles are well comparable with NOAA meteorological re-analysis, from the ground up to 25 km. As expected, above the high Antarctica plateau, SSS shows the same optical turbulence distribution, mainly concentrated within the surface layer.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to the technical staff of Fizeau laboratory for its help in the construction of the SSS prototype. We thank the Institut Paul-Emile Victor personnel as well as the members of Antarctica expedition who helped in the infrastructure at Dome C. The SSS prototype working at Dome C has been funded by the French ``Institut National des Sciences de l'Univers''. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration is acknowledged for access to its meteorological re-analysis profiles through its ARL web-site. Part of the development of the SSS technique was undertaken in the framework of the contract #F61775-02-C0002 with the US Air Force EOARD.

References

- Agabi, A., Aristidi, E., Azouit, M., et al. 2006, PASP, 118, 344 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Avila, R., Vernin, J., & Sánchez, L. J. 2001, A&A, 369, 364 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences]

- Azouit, M., & Vernin, J. 2005, PASP, 117, 536 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Fuchs, A., Tallon, M., & Vernin, J. 1998, PASP, 110, 86 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Habib, A., Vernin, J., Benkhaldoun, Z., & Lanteri, H. 2006, MNRAS, 368, 1456 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Kornilov, V., Tokovinin, A. A., Vozyakova, O., et al. 2003, in Adaptive Optical System Technologies II., ed. P. L. Wizinowich, & D. Bonaccini, SPIE, 4839, 837 (In the text)

- Lawrence, J. S., Ashley, M. C. B., Tokovinin, A., & Travouillon, T. 2004, Nature, 431, 278 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Lloyd, J. P. 2004, in New Frontiers in Stellar Interferometry, ed. W. A. Traub, 5491, 190 (In the text)

- Marks, R. D., Vernin, J., Azouit, M., Manigault, J. F., & Clevelin, C. 1999, A&AS, 134, 161 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences]

- Roddier, F. 1981, Prog. Optics, 19, 281 (In the text)

- Trinquet, H., Agabi, A., Vernin, J., et al. 2008, PASP, 120, 203 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Vernin, J. 1994, in Recherches polaires: une stratégie pour l'an 2000, Académie des Sciences (Paris, Tec & Doc, Lavoisier), 91 (In the text)

- Vernin, J., Agabi, A., Aristidi, E., et al. 2007, Highlights of Astronomy, 14, 693 [NASA ADS] (In the text)

- Vernin, J., & Azouit, M. 1983a, Journal d'Optique, 14, 5 [NASA ADS]

- Vernin, J., & Azouit, M. 1983b, Journal d'Optique, 14, 131 [NASA ADS] (In the text)

- Wilson, R. W. 2002, MNRAS, 337, 103 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

All Figures

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm]{1119fig1}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/24/aa11119-08/Timg29.png) |

Figure 1: Installation of the SSS above one of the two plateforms at Dome C during polar summer 2005-2006. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

| |

Figure 2:

Principle of the generalized SSS. After passing through the telescope, light is collimated by

a short focal lens. In order to make the low altitude layers scintillate, the photoelectric

receiver is displaced by a distance |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

| |

Figure 3:

From left to right, two-dimensional auto-correlation, first and second cross-correlation of the scintillation pattern on the 40 cm entrance pupil of the telescope

corresponding to time lags |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm]{1119fig4}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/24/aa11119-08/Timg52.png) |

Figure 4:

Measured temporal cross-correlation ( left) at |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=270,width=18cm]{1119fig5}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/24/aa11119-08/Timg55.png) |

Figure 5:

Top left: median vertical profile of the optical turbulence on a logarithmic

scale CN2(h)and

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=270,width=9cm]{1119fig6a}

\includegraphics[angle=270,width=9cm]{1119fig6b}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/24/aa11119-08/Timg60.png) |

Figure 6:

Temporal evolution of the optical turbulence

Cn2(h,t) ( top)

and of the wind speed modulus

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=270,width=9cm]{1119fig7}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/24/aa11119-08/Timg61.png) |

Figure 7:

From top left to bottom right: temporal evolution of the

seeing

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=270,width=9cm]{1119fig8}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/24/aa11119-08/Timg62.png) |

Figure 8: Temporal evolution of seeing measured by SSS (red crosses) and DIMM (line) during 6.5 h on 20 March 2006. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=270,width=9cm]{1119fig9}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/24/aa11119-08/Timg65.png) |

Figure 9: Correlation between seeings measured by SSS and DIMM. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=270,width=9cm]{1119fig10}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/24/aa11119-08/Timg66.png) |

Figure 10: Temporal evolution of seeing measured by SSS (red crosses) and DIMM (line) during 0.5 h over 21 March 2006. 0.2 to 0.3 arcsec seeings are detected both by SSS and DIMM. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=270,width=9cm]{1119fig11}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/24/aa11119-08/Timg68.png) |

Figure 11:

Temporal evolution of the wind speed modulus deduced from SSS measurements in the four

layers within the boundary layer, with a one-hour sliding triangle convolution.

The two measurements from NOAA re-analysis at |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

Copyright ESO 2009

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.